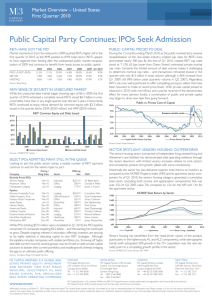

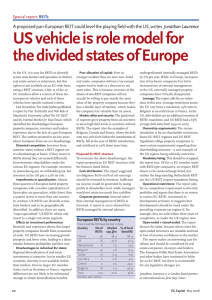

The Intelligent REIT Investor: Real Estate Investment Trusts

advertisement