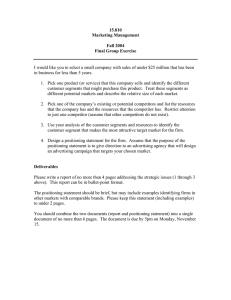

Al Ries, Jack Trout, Philip Kotler - Positioning The Battle for Your Mind-McGraw-Hill Education (2001)

advertisement