Accounting, 6th Edition, 1-26 (Charles T. Horngren Series in Accounting) ( PDFDrive )

advertisement

Visit the www.prenhall.com/horngren Web site for self-study quizzes, video

clips, and other resources

Try the Quick Check exercise at the end of the chapter to test your

knowledge

Learn the key terms

Do the Starter exercises keyed in the margins

Work the mid- and end-of-chapter summary problems

Use the Concept Links to review material in other chapters

Search the CD for review materials by chapter or by key word

Watch the tutorial videos to review key concepts

Watch the On Location Accounting and Business video for an overview of

the accounting function.

2

Use accounting vocabulary

Apply accounting concepts and principles

Use the accounting equation

Analyze business transactions

Prepare the financial statements

Evaluate business performance

ike most other people, you’ve probably bought Amazon.com products by shopping online.

And like most other people, you’ve probably been amazed at how easy it is. Amazon.com is

one of the most interesting organizations on earth. Consider these facts about the company:

■

Amazon.com opened its virtual doors in 1995.

■

In only a few years, millions of people in 220 countries have made it the

world’s leading online shopping site.

■

It offers the world’s largest selection of products.

■

On Amazon.com’s busiest shopping day of 2002, customers ordered 1.7

million units. That’s 20 items per second, around the clock.

■

There is still no Amazon.com store anywhere except online.

Amazon.com

3

4

Chapter 1

Amazon.com continues to add partners and merchandise at breakneck speed. But it

took from 1995 to 2002 for the company to post a profit. And it reported the figures

using standard accounting methods.

What does all this mean? What does “profitable” mean? What are standard accounting methods? How can a company keep growing if it isn’t making money? Lots of questions: And here’s where accounting comes in. “Profitable” means that the company earns

more revenue than its expenses. Accounting methods govern how companies keep track

of their activities. This book will help you understand revenues, expenses, profit and

loss, and other business concepts. After completing this first accounting course, you will

be able to decide whether a company is a good (or bad) investment. You will be able to

evaluate an auto loan and manage your own money. You will also be able to use accounting in your business career. ■

■ The Language of Business

■ Regulating Accounting

■ Business Organizations

■ Concepts and Principles

■ The Accounting Equation

■ Business Transactions

■ Evaluating Transactions

■ The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

We’ll start our study with a small, single-person business known as a proprietorship.We

need to begin by asking exactly what accounting is.

Accounting: The Language of Business

Accounting is the information system that measures business activity, processes

the information into reports, and communicates the results to decision makers.

Accounting is “the language of business.” The better you understand the language, the better your decisions will be, and the better you can manage your

finances. For example, how will you decide whether to borrow money? You had

better consider your income: The concept of income comes straight from

accounting.

A key product of accounting is a set of documents called financial statements. Financial statements report on a business in monetary terms. Is

Amazon.com making a profit? Should Amazon expand? Answering these questions calls for Amazon’s financial statements.

Exhibit 1-1 illustrates the role of accounting in business. The process starts

and ends with people making decisions.

financial statements

The Accounting System: The Flow of Information

Exhibit 1-1

Use accounting vocabulary

Accounting

The information system that measures

business activities, processes that

information into reports, and

communicates the results to decision

makers.

People make

decisions

$100

$80

$60

$40

$20

Financial Statements

Documents that report on a business

in monetary amounts, providing

information to help people make

informed business decisions.

0

93 94 95 96

Business

transactions occur

Businesses prepare

reports to show the results

of their operations

Accounting: The Language of Business

5

Decision Makers: The Users of Accounting Information

Decision makers need information. The bigger the decision, the greater the need.

Here are some decision makers who use accounting information.

INDIVIDUALS You use accounting information to manage your bank account, evaluate a new job prospect, and decide whether to rent or buy a house. Amazon.com

employees in Seattle, Washington, make the same decisions that you do.

BUSINESSES Managers use accounting information to set goals for their organizations. They also evaluate progress toward those goals, and they take corrective

action when it’s needed. For example, Amazon must decide which software to

purchase, how many DVDs and books to keep on hand, and how much money to

borrow. Accounting provides the information for making these decisions.

I NVESTORS Investors provide the money to get a business going. To decide

whether to invest, a person predicts the amount of income on the investment. This

means analyzing the financial statements and keeping up with company developments—using, for example, www.yahoo.com (click on Finance), www.hoovers.com

(click on Companies), the SEC’s EDGAR database, and The Wall Street Journal.

Teaching Tip

A brainstorming session can produce

interesting discussion. Relate the ideas

that emerge to the accounting vocabulary introduced in this chapter.

CREDITORS Before lending money, a bank evaluates the borrower’s ability to make

the payments. This evaluation includes a report on the borrower’s financial position

and predicted income. To borrow money before striking it rich, Jeff Bezos, the president of Amazon.com, probably had to document his income and financial position.

GOVERNMENT REGULATORY AGENCIES Most organizations face government

regulation. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), a federal

agency, requires businesses to report their financial information to the public.

TAXING AUTHORITIES Local, state, and federal governments levy taxes.

Income tax is figured using accounting information. Sales tax depends upon a

company’s sales.

NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS Nonprofit organizations—churches, hospitals, and colleges—use accounting information the same way as Amazon.com

and The Coca-Cola Company.

Financial Accounting and Management Accounting

Accounting can be divided into two fields—financial accounting and management accounting.

Financial accounting provides information for people outside the company.

Lenders and outside investors are not part of day-to-day management. These

people use the company’s financial statements. Chapters 2–18 of this book deal

primarily with financial accounting.

Management accounting focuses on information for internal decision makers, such as the company’s executives and the administrators of a hospital.

Chapters 19 through 26 cover management accounting. Exhibit 1-2 illustrates the

difference between financial accounting and management accounting.

Exhibit 1-2

Financial Accounting

The branch of accounting that focuses

on information for people outside the

firm.

Management Accounting

The branch of accounting that focuses

on information for internal decision

makers of a business.

Financial Accounting and Management Accounting

Investors:

Should we invest in Amazon.com?

Is the company profitable?

Investors use financial accounting

information to measure profitability.

Amazon.com

Jeff Bezos, president, and

other managers use

management accounting

information to operate

the company.

Creditors:

Should we lend money to Amazon.com?

Can the company pay us back?

Creditors use financial accounting information

to decide whether to make a loan.

6

Chapter 1

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

■ Regulating Accounting

All professions have regulations. Let’s see the organizations that most influence

the accounting profession.

Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

Governing Organizations

ethics

Financial Accounting Standards

Board (FASB)

The private organization that

determines how accounting is

practiced in the United States.

Certified Public Accountant (CPA)

A licensed accountant who serves the

general public rather than one

particular company.

In the United States, a private organization called the Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASB) formulates accounting standards. The FASB works

with a governmental agency, the SEC, and two private groups, the American

Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and the Institute of

Management Accountants (IMA). Certified public accountants, or CPAs, are

professional accountants who are licensed to serve the general public. Certified

management accountants, or CMAs, are professional accountants who work for

a single company. Both groups of accountants have passed qualifying exams.

The rules that govern public accounting information are called generally

accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Exhibit 1-3 diagrams the relationships

among the various accounting organizations.

Exhibit 1-3

Public Sector

Key Accounting Organizations

The Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC),

a government agency,

regulates securities markets

in the United States.

Private Sector

Professional accountants

apply generally accepted

accounting principles.

Certified Management Accountant

(CMA)

A licensed accountant who works for a

single company.

Audit

An examination of a company’s

financial situation.

Teaching Tip

Many students think that in accounting, there is always a single right

answer. But personal and professional

ethics are often the key to the “right”

answer in difficult situations.

Discussion

Q: What do you know about Enron,

WorldCom, and other corporate scandals? How do the scandals make you

feel about accounting as a profession?

A: There are no right answers.

Students may discuss changes in corporate governance and the SarbanesOxley Act of 2002.

Private Sector

Generally accepted

accounting principles

(GAAP)

The Financial Accounting

Standards Board

(FASB) determines

generally accepted

accounting principles.

Ethics in Accounting and Business

Ethical considerations affect everything accountants do. Investors and creditors

need relevant and reliable information about a company such as Amazon.com or

General Motors. The companies naturally want to make themselves look as good

as possible in order to attract investors. There is potential for conflict here. To

provide reliable information for the public, the SEC requires companies to have

their financial statements audited by independent accountants. An audit is a

financial examination. The accountants then certify that the financial statements

give a true picture of the company’s situation.

The vast majority of accountants do their jobs quietly, professionally, and

ethically. We never hear about them. Unfortunately, only those who bend the

rules make the headlines. In recent years we’ve seen more accounting scandals

than at any time since the 1920s.

Enron Corp., for example, was the seventh-largest company in the United

States before the company admitted reporting fewer debts than it really owed.

WorldCom, a major long-distance telephone provider, admitted accounting for

expenses as though they were assets (resources). Xerox Corp. was accused of

manipulating reported profits. These and other scandals rocked the business

community and hurt investor confidence. Innocent people lost their jobs, and the

stock market suffered. The courts are still sorting out who was responsible for

the flawed information and its consequences.

Regulating Accounting

The New Economy: Pumping Up Revenue

via Round-Trip Trades

The stock market can get obsessed with revenue, and

that can put intense pressure on companies to boost

their revenue figures. “Round-trip trades” are one

technique for reporting high revenues.These deals typically involve a swap of assets or services without any

real gains.Two companies get together and set a price

for advertising on each other's Web sites at, say, $1 million.They then swap banners and each declares $1 million as revenue and $1 million for expenses—but not a

single penny changes hands. Here are some examples:

●

●

●

In 1999, the women's Web site iVillage revealed that 20% of its revenue came from

round-trip trades of online advertising.

In 2001, CMS Energy and Dynegy completed two electricity trades worth $1.7

billion on Dynegy's online trading platform.The trades cancelled each other out, but

the companies cited the artificially boosted revenues in their press releases.

With revenues lagging, telecom companies Global Crossing and Qwest began

booking revenue from capacity swaps in 1999.

The SEC began investigating round-trip trades when it learned that many of the

transactions served only to inflate revenue, and in 2002 it barred telecom trades that

inflate revenue. Earlier, in 1999, the FASB forced companies to disclose online advertising

swaps as “barter revenue.” Yet, scrutiny from shareholders and accounting regulatory

agencies hasn't stopped everyone.

Homestore, Inc., an online real estate company, and America Online are now

under investigation for complex multiparty deals in which Homestore allegedly bought

products from a third company, which then bought ads on America Online.The days of

round-trip trades may be over.

Based on: Dennis K. Berman, Julia Angwin, and Chip Cummins,“What's Wrong?—Tricks of the Trade:As Market Bubble Neared

End, Bogus Swaps Provided a Lift,” The Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2002, p. A1. David Wessel, “What's Wrong?—Venal

Sins:Why the Bad Guys of the Boardroom Emerged en Masse,” The Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2002, p.A1. Susan Pulliam and

Rebecca Blumenstein,“SEC Broadens Investigation into Revenue-Boosting Tricks,” The Wall Street Journal, May 16, 2002, p.A1.

Standards of Professional Conduct

The AICPA’s Code of Professional Conduct for Accountants provides guidance

to CPAs in their work. Ethical standards are designed to produce relevant and

reliable information for decision making. The preamble to the Code states: “[A]

certified public accountant assumes an obligation of self-discipline above and

beyond the requirements of laws and regulations . . . [and] an unswerving commitment to honorable behavior. . . . ”

The opening paragraph of the Standards of Ethical Conduct of the Institute

of Management Accountants (IMA) states: “Management accountants have an

obligation to the organizations they serve, their profession, the public, and themselves to maintain the highest standards of ethical conduct.” The requirements

are similar to those in the AICPA code.

Most corporations also set standards of ethical conduct for employees. For

example, The Boeing Company, a leading manufacturer of aircraft, has a highly

developed set of business conduct guidelines. The chairperson of the board

states: “We owe our success as much to our reputation for integrity as we do to

the quality and dependability of our products and services. This reputation is

7

8

Chapter 1

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

■ Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

corporation, partnership, proprietorship

Proprietorship

A business with a single owner.

fragile and can easily be lost.” As one chief executive has stated, “Ethical practice

is simply good business.”

Truth is always better than dishonesty—in accounting, in business, and in life.

Types of Business Organizations

A business can have one of three forms of organization: proprietorship, partnership, or corporation. You should understand the differences among the three.

PROPRIETORSHIPS

A proprietorship has a single owner, called the proprietor, who is often the manager. Proprietorships tend to be small retail stores or

professional businesses, such as physicians, attorneys, and accountants. From

the accounting viewpoint, each proprietorship is distinct from its proprietor: The

accounting records of the proprietorship do not include the proprietor’s personal

financial records. However, from a legal perspective, the business is the proprietor. In this book, we begin the accounting process with a proprietorship.

Partnership

A business with two or more owners.

PARTNERSHIPS A partnership joins two or more individuals as co-owners.

Each owner is a partner. Many retail establishments and professional organizations of physicians, attorneys, and accountants are partnerships. Most partnerships are small or medium-sized, but some are gigantic, exceeding 2,000 partners. Accounting treats the partnership as a separate organization, distinct from

the personal affairs of each partner. But again, from a legal perspective, a partnership is the partners.

Corporation

A business owned by stockholders; it

begins when the state approves its

articles of incorporation. A corporation

is a legal entity, an “artificial person,”

in the eyes of the law.

CORPORATIONS

Stockholder

A person who owns stock in a

corporation. Also called a shareholder.

Teaching Tip

The proprietorship form of organization is used in Chapters 1–11.

Partnerships are covered in Chapter

12. The corporate form of organization

is covered in Chapter 13 (although

most of the material after Chapter 4

applies to all forms).

Exhibit 1-4

A corporation is a business owned by stockholders, or

shareholders. These are the people who own shares of ownership in the business. A business becomes a corporation when the state approves its articles of

incorporation. A corporation is a legal entity that conducts business in its own

name. Unlike the proprietorship and the partnership, the corporation is not

defined by its owners.

Corporations differ significantly from proprietorships and partnerships in

another way. If a proprietorship or a partnership cannot pay its debts, lenders

can take the owners’ personal assets—their cash—to satisfy the business’s obligations. But if a corporation goes bankrupt, lenders cannot take the personal

assets of the stockholders. This limited liability of stockholders for corporate debts

explains why corporations are so popular: People can invest in corporations with

limited personal risk.

Another factor in corporate growth is the division of ownership into individual

shares. The Coca-Cola Company, for example, has billions of shares of stock owned

by many stockholders. An investor with no personal relationship to Coca-Cola can

become a stockholder by buying 50, 100, 5,000, or any number of shares of its stock.

Exhibit 1-4 summarizes the differences among the three types of business

organization.

Comparison of the Three Forms of Business Organization

Proprietorship

Partnership

1. Owner(s)

Proprietor—there is only

one owner

Partners—there are two

or more owners

Stockholders—there are

generally many owners

Corporation

2. Life of the organization

Limited by the owner's

choice, or death

Limited by the owners'

choices, or death

Indefinite

3. Personal liability of the owner(s)

for the business's debts

4. Legal status of

the organization

Proprietor is personally

liable

The proprietorship is

the proprietor

Partners are personally

liable

The partnership is

the partners

Stockholders are not

personally liable

The corporation is separate

from the stockholders

Accounting Concepts and Principles

Accounting Concepts and Principles

The rules that govern accounting fall under the heading GAAP, which stands for

generally accepted accounting principles. GAAP is the “law” of accounting—

rules for providing the information that is acceptable to the majority of

Americans.

GAAP rests on a conceptual framework written by the FASB: The primary

objective of financial reporting is to provide information useful for making investment

and lending decisions. To be useful, information must be relevant, reliable, and

comparable. We begin the discussion of GAAP by introducing basic accounting

concepts and principles.

The Entity Concept

The most basic concept in accounting is that of the entity. An accounting entity is

an organization or a section of an organization that stands apart as a separate

economic unit. In accounting, boundaries are drawn around each entity so as not

to confuse its affairs with those of other entities.

Consider Amazon.com. Assume Jeff Bezos started Amazon.com on his own.

Suppose he began with $5,000 obtained from a bank loan. Following the entity

concept, Bezos would account for the $5,000 separately from his personal assets,

such as his clothing, house, and automobile. To mix the $5,000 of business cash

with his personal assets would make it difficult to measure the financial position

of Amazon.com.

Consider Toyota, a huge organization with several divisions. Toyota management evaluates each division as a separate accounting entity. If sales in the

Lexus division are dropping, Toyota can find out why. But if sales figures from

all divisions of the company are combined, management will not know that

Lexus sales are going down. Thus, the entity concept applies to any economic unit

that needs to be evaluated separately.

The Reliability (Objectivity) Principle

Accounting information is based on the most reliable data available. This guideline is the reliability principle, also called the objectivity principle. Reliable data are

verifiable. They may be confirmed by any independent observer. For example,

an Amazon.com bank loan is supported by a promissory note. This is objective

evidence of the loan. Without the reliability principle, accounting data might be

based on whims and opinions.

Suppose you want to open an electronics store. For a store location, you transfer a small building to the business. You believe the building is worth $150,000.

To confirm its cost to the business, you hire two real estate appraisers, who value

the building at $140,000. Which is the more reliable estimate of the building’s

value, your estimate of $150,000 or the $140,000 professional appraisal? The

appraisal of $140,000 is more reliable because it is supported by an independent

observation. The business should record the building cost as $140,000.

The Cost Principle

The cost principle states that acquired assets and services should be recorded at

their actual cost (also called historical cost). Even though the purchaser may

believe the price is a bargain, the item is recorded at the price actually paid and

not at the “expected” cost. Suppose your electronics store purchases TV equipment from a supplier who is going out of business. Assume that you get a good

deal and pay only $2,000 for equipment that would have cost you $3,000 elsewhere. The cost principle requires you to record the equipment at its actual cost

of $2,000, not the $3,000 that you believe the equipment is worth.

9

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

Business Organizations

■ Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

accounting principles

Apply accounting concepts and

principles

Generally Accepted Accounting

Principles (GAAP)

Accounting guidelines, formulated by

the Financial Accounting Standards

Board, that govern how accountants

measure, process, and communicate

financial information.

Entity

An organization or a section of an

organization that, for accounting

purposes, stands apart from other

organizations and individuals as a

separate economic unit.

Teaching Tip

The relationship between accounting

concepts and principles and GAAP is

similar to the relationship between the

Constitution of the United States and

the laws passed by Congress and individual states.

Discussion

Q: If you had three different businesses, would you want to use one

checkbook or three? Why?

A: You would want to keep three different checkbooks. With one checkbook, you might not realize one business was losing money (the entity

concept).

10

Chapter 1

The cost principle also holds that the accounting records should maintain the

historical cost of an asset over its useful life. Why? Because cost is a reliable measure. Suppose your store holds the TV equipment for six months. During that

time TV prices rise, and the equipment can be sold for $3,500. Should its accounting value—the figure “on the books”—be the actual cost of $2,000 or the current

market value of $3,500? By the cost principle, the accounting value of the equipment remains at actual cost: $2,000.

You are considering the purchase of land for future expansion. The seller is asking

$50,000 for land that cost her $35,000. An appraisal shows a value of $47,000. You first

offer $44,000. The seller counteroffers with $48,000, and you agree on a price of $46,000.

What dollar value for this land is reported on your financial statement? Which accounting concept or principle guides your answers?

Answer: According to the cost principle, assets and services should be recorded at

their actual cost. You paid $46,000 for the land, so report the land at $46,000.

The Going-Concern Concept

Another reason for measuring assets at historical cost is the going-concern concept.

This concept assumes that the entity will remain in operation for the foreseeable

future. Under the going-concern concept, accountants assume that the business

will remain in operation long enough to use existing resources for their intended

purpose.

To understand the going-concern concept better, consider the alternative—

which is to go out of business. A store holding a going-out-of-business sale is trying to sell everything. In that case, instead of historical cost, the relevant measure

is current market value. But going out of business is the exception rather than

the rule.

The Stable-Monetary-Unit Concept

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

■ The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

In the United States, we record transactions in dollars because the dollar is the

medium of exchange. British accountants record transactions in pounds sterling.

French and German transactions are measured in euros. The Japanese record

transactions in yen. The value of a dollar or a Mexican peso changes over time. A

rise in the price level is called inflation. During inflation, a dollar will purchase

less milk, less gas for your car, and less of other goods. When prices are stable—

when there is little inflation—the purchasing power of money is also stable.

Accountants assume that the dollar’s purchasing power is stable. It allows us

to add and subtract dollar amounts as though each dollar has the same purchasing power as any other dollar at any other time.

The Accounting Equation

accounting equation, asset, liability,

owner’s equity

The basic tool of accounting is the accounting equation. It measures the

resources of a business and the claims to those resources.

Use the accounting equation

Accounting Equation

The basic tool of accounting, measuring

the resources of the business and the

claims to those resources: Assets =

Liabilities + Owner's Equity.

Asset

An economic resource that is expected

to be of benefit in the future.

Assets and Liabilities

Assets are economic resources that are expected to be of benefit in the future.

Cash, merchandise inventory, furniture, and land are assets.

Claims to those assets come from two sources. Liabilities are outsider

claims—debts that are payable to outsiders. These outside parties are called

creditors. For example, a creditor who has loaned money to Amazon.com has a

claim to some of Amazon’s assets until Amazon pays the debt.

11

Exhibit 1-5

Insider claims to Amazon.com’s assets are called owner’s equity, or capital.

These insider claims are held by the owners of the business. Owners have a claim

to some of the assets because they have invested in the business.

The accounting equation shows how assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity

are related. Assets appear on the left side of the equation, and the liabilities and

owner’s equity appear on the right side. Exhibit 1-5 shows that the two sides

must always be equal:

(Economic Resources)

ASSETS

(Claims to Economic Resources)

=

LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

The Accounting Equation

Liabilities

Assets

Owner‘s

Equity

Assets

=

Liabilities

+

Owner‘s

Equity

1. If the assets of a business are $170,000 and the liabilities total $80,000, how much is

the owner’s equity?

2. If the owner’s equity in a business is $22,000 and the liabilities are $36,000, how

much are the assets?

Answers: To answer both questions, use the accounting equation:

1.

ASSETS − LIABILITIES = OWNER’S EQUITY

$170,000 −

2.

$80,000

=

$90,000

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

$58,000 =

$36,000

+

$22,000

Here is an example that illustrates the elements of the accounting equation.

Sony supplies cell phones to Amazon.com. Amazon may buy the cell phones on

credit and promise to pay Sony later. Sony’s claim against Amazon.com is an

account receivable, an asset that will benefit Sony. A written promise for future

collection is called a note receivable.

Amazon.com has a debt to pay Sony. This liability is an account payable. It

is backed only by the reputation and the credit standing of Amazon. A written

promise of future payment is called a note payable.

All receivables are assets. All payables are liabilities. Most businesses have

both receivables and payables.

Owner’s Equity

Owner’s equity is the amount of an entity’s assets that remain after its liabilities

are subtracted.

ASSETS − LIABILITIES = OWNER’S EQUITY

The purpose of business is to increase owner ’s equity through revenues.

Revenues are increases in owner’s equity earned by delivering goods or services to customers. Revenues also increase assets, or they decrease liabilities.

As a result, the owner’s share of the business’s assets increases. Exhibit 1-6

shows that owner investments and revenues increase the owner’s equity of the

business.

Liability

An economic obligation (a debt)

payable to an individual or an

organization outside the business.

Owner's Equity

The claim of a business owner to the

assets of the business. Also called

capital.

Teaching Tip

You might find that it helps to really

drive home the following associations:

“earned” → “revenue” and “used up”

→ “expense.”

Teaching Tip

Simple definitions: Assets: what you

own; Liabilities: what you owe to outsiders; Owner's Equity: what you owe

to your owner; Revenue: what you do

to earn more assets; Expenses: what you

do to use up assets (or get liabilities).

Account Receivable

A promise to receive cash from

customers to whom the business has

sold goods or for whom the business

has performed services.

Note Receivable

A written promise for future collection

of cash.

Account Payable

A liability backed by the general

reputation and credit standing of the

debtor.

Note Payable

A written promise of future payment.

Revenue

Amounts earned by delivering goods

or services to customers. Revenues

increase owner's equity.

12

Chapter 1

Exhibit 1-6

Transactions That Increase or

Decrease Owner's Equity

Teaching Tip

Revenues and expenses don't have any

physical existence. We use these terms

to describe what an entity does to

increase or decrease its assets and liabilities.

Owner‘s Equity

Increases Due to

Owner‘s Equity

Decreases Due to

Owner Investments

in the Business

Owner Withdrawals

from the Business

Owner‘s Equity

✔ Starter 1-1

Revenues

Expenses

✔ Starter 1-2

Owner Withdrawals

Amounts removed from the business

by an owner.

Expense

Decrease in owner's equity that occurs

from using assets or increasing

liabilities in the course of delivering

goods or services to customers.

✔ Starter 1-3

✔ Starter 1-4

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

■ Business Transactions

Evaluating Transactions

transaction analysis

Transaction

An event that affects the financial

position of a particular entity and can

be recorded reliably.

Analyze business transactions

Exhibit 1-6 also shows that owner withdrawals and expenses decrease

owner’s equity. Owner withdrawals are amounts removed from the business by

the owner. Withdrawals are the opposite of owner investments. Expenses are

decreases in owner’s equity that occur from using assets or increasing liabilities

to deliver goods and services to customers. Expenses are the cost of doing business; they are the opposite of revenues. Expenses include the cost of:

■

Office rent

■

Interest on loans

■

Salaries of employees

■

Insurance

■

Advertisements

■

Property taxes

■

Utility payments

■

Supplies used up

Accounting for Business Transactions

Accounting records are based on actual transactions. A transaction is any event

that affects the financial position of the business and can be recorded reliably.

Many events affect a company, including elections and economic booms.

Accountants do not record the effects of those events because they can’t be measured reliably. An accountant records only those events with effects that can be

measured reliably, such as the purchase of a building, a sale of merchandise to a

customer, and the payment of rent. The dollar amounts of these events can be

measured reliably, so accountants record these transactions.

What are some of your personal transactions? You may have bought a DVD

player. Your purchase was a transaction. If you are making payments on an

auto loan, your payments are also transactions. You need to record all your

business transactions just as Amazon.com does in order to manage your personal affairs.

To illustrate accounting for a business, let’s use Gay Gillen eTravel. Gillen

operates a travel agency. Online customers plan and pay for their trips through

the Gillen Web site. The Web site is linked to airlines, hotels, and cruise lines, so

clients can obtain the latest information 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Gillen’s

Web site allows the agency to transact more business than it could through the

phone, fax, or e-mail. As a result, Gillen can operate with few employees, and

this saves on expenses. She can pass along the cost savings to clients by charging

them lower commissions. That builds up her business.

Now let’s analyze some of Gillen eTravel’s transactions.

TRANSACTION 1: STARTING

THE BUSINESS Gay Gillen invests $30,000 of

her own money to start the business. She deposits $30,000 in a bank account

titled Gay Gillen eTravel. The effect of this transaction on the accounting equation of the Gay Gillen eTravel business entity is

Accounting for Business Transactions

ASSETS

LIABILITIES

OWNER’S EQUITY

=

Cash

+

13

TYPE OF OWNER’S

EQUITY TRANSACTION

Gay Gillen, Capital

(1) +30,000

+30,000

Owner investment

For every transaction, the amount on the left side of the equation must equal the

amount on the right side. The first transaction increases both the assets (in this

case, Cash) and the owner’s equity (Gay Gillen, Capital) of the business. To the

right of the transaction, we write “Owner investment” to keep track of the source

of the owner’s equity.

Immediately after this first transaction, Gay Gillen eTravel can prepare a balance sheet. A balance sheet reports the assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity of the

business. Gillen’s initial balance sheet would appear as follows on April 1, 20X5:

Balance Sheet

An entity's assets, liabilities, and

owner's equity as of a specific date.

Also called the statement of financial

position.

Gay Gillen eTravel

Balance Sheet

April 1, 20X5

Assets

=

Cash. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$30,000

$30,000

Liabilities

None. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

+

Owner’s Equity

$0

Gay Gillen, capital . . . . . . .

Total liabilities and

owner’s equity . . . . . . . .

30,000

$30,000

A balance sheet reports the financial position of the entity at a moment in time—

in this case at the stroke of midnight on April 1. Gay Gillen eTravel has $30,000 of

cash, owes no liabilities, and has owner’s equity of $30,000.

TRANSACTION 2: PURCHASE

OF LAND Gillen purchases land for an office

location, paying cash of $20,000. The effect of this transaction on the accounting

equation is

ASSETS

Cash

LIABILITIES

+

(1) 30,000

(2) −20,000 +

Bal. 10,000

Land

30,000

OWNER’S EQUITY

TYPE OF OWNER’S

EQUITY TRANSACTION

Gay Gillen, Capital

=

20,000

20,000

+

30,000

Owner investment

30,000

30,000

The cash purchase of land increases one asset, Land, and decreases another asset,

Cash, by the same amount. After the transaction is completed, Gillen’s business

has cash of $10,000, land of $20,000, no liabilities, and owner’s equity of $30,000.

Note that the sums of the balances (abbreviated Bal.) on both sides of the equation must always be equal.

With software, such as QuickBooks and Peachtree, a business can print a balance sheet at any time to see where it stands financially. Gillen can use

QuickBooks to prepare a balance sheet—this time after two transactions. The

business’s balance sheet on April 2 follows:

Short Exercise

Joe starts a lawn service business with

$5,000 of his own money. He borrows

$2,000 from the bank and uses all of it

to buy a lawnmower. (a) What are the

total assets owned by the business? (b)

What are the liabilities? (c) What is the

owner's equity? Answers: (a) $7,000

($5,000 in cash and $2,000 in equipment). (b) $2,000 (note payable to the

bank). (c) $5,000 (Joe's share of the

business—called capital).

✔ Starter 1-5

✔ Starter 1-6

✔ Starter 1-7

14

Chapter 1

Gay Gillen eTravel

Balance Sheet

April 2, 20X5

Assets

Liabilities

Cash. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$10,000

Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20,000

None. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$0

Owner’s Equity

Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$30,000

Gay Gillen, capital . . . . . . .

30,000

Total liabilities and

owner’s equity . . . . . . . .

$30,000

Now the business holds two assets, with the liabilities and owner’s equity

unchanged. After we move through a sequence of transactions, we will return to

Gillen’s balance sheet. It’s most common to prepare a balance sheet at the end of

the accounting period. Now let’s account for additional transactions of Gay

Gillen eTravel.

TRANSACTION 3: PURCHASE OF OFFICE SUPPLIES Gillen buys stationery

and other office supplies, agreeing to pay $500 within 30 days. This transaction

increases both the assets and the liabilities of the business. Its effect on the

accounting equation is

ASSETS

Cash

Bal.

(3)

Bal.

Office

+ Supplies

10,000

10,000

+

Land

+

OWNER’S EQUITY

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

=

20,000

+500

500

LIABILITIES

30,000

+500

500

20,000

30,000

30,500

30,500

Office Supplies is an asset, not an expense, because the supplies can be used in

the future. The liability created by this transaction is an account payable. Recall

that a payable is a liability.

Prepare the balance sheet of Gay Gillen eTravel on April 9, after transaction 3.

Answer:

Gay Gillen eTravel

Balance Sheet

April 9, 20X5

Liabilities

Assets

Cash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Office supplies . . . . . . . . .

Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$10,000

500

20,000

Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$30,500

T RANSACTION 4: EARNING

Accounts payable . . . . . . .

$500

Owner’s Equity

Gay Gillen, capital . . . . . . 30,000

Total liabilities and

owner’s equity . . . . . . . $30,500

S ERVICE REVENUE

Gay Gillen eTravel

earns service revenue by providing travel services for clients. She earns $5,500

revenue and collects this amount in cash. The effect on the accounting equation

is an increase in the asset Cash and an increase in Gay Gillen, Capital, as follows:

OF

Accounting for Business Transactions

Cash

ASSETS

LIABILITIES

+

OWNER’S

EQUITY

Office

+ Supplies +

Land

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

500

20,000

500

500

20,000

500

Bal. 10,000

(4) +5,500

Bal. 15,500

=

36,000

30,000

+5,500

35,500

15

TYPE OF

OWNER’S EQUITY

TRANSACTION

Service revenue

36,000

✔ Starter 1-8

A revenue transaction grows the business, as shown by the increases in assets

and owner’s equity. A company like Amazon.com or Wal-Mart that sells goods

to customers is a merchandising business. Its revenue is called sales revenue. By

contrast, Gay Gillen eTravel performs services for clients; Gillen’s revenue is

called service revenue.

TRANSACTION 5: EARNING OF SERVICE REVENUE ON ACCOUNT Gillen performs services for clients who do not pay immediately. In return for her travel services, Gillen receives clients’ promises to pay $3,000 within one month. This promise

is an asset to Gillen, an account receivable because she expects to collect the cash in

the future. In accounting, we say that Gillen performed this service on account. When

the business performs service for a client, the business earns the revenue.

The act of performing the service, not collecting the cash, earns the revenue.

This $3,000 of service revenue increases the wealth of Gillen’s business just like

the $5,500 of revenue that she collected immediately in transaction 4. Gillen

records $3,000 of revenue on account as follows:

ASSETS

Cash

Bal.

(5)

Bal.

+

Accounts

Receivable

Office

Supplies

+

15,500

+

500

+3,000

3,000

15,500

Land

20,000

500

=

20,000

LIABILITIES

+

OWNER’S

EQUITY

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

500

500

39,000

TRANSACTION 6: PAYMENT

35,500

+3,000

38,500

TYPE OF

OWNER’S EQUITY

TRANSACTION

Service revenue

39,000

OF

EXPENSES During the month, Gillen pays

$3,300 in cash expenses: lease expense on a computer, $600; office rent, $1,100;

employee salary, $1,200 (part-time assistant); and utilities, $400. The effects on

the accounting equation are

LIABILITIES

+

OWNER’S

EQUITY

Land

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

20,000

500

ASSETS

Cash

Bal. 15,500

(6) − 600

+

Accounts

Receivable

+

3,000

Office

Supplies

500

+

38,500

− 600

=

− 1,100

− 1,100

(6) − 1,200

(6) − 400

Bal. 12,200

− 1,200

− 400

35,200

(6)

3,000

500

35,700

20,000

500

35,700

TYPE OF

OWNER’S EQUITY

TRANSACTION

Lease expense,

computer

Rent expense,

office

Salary expense

Utilities expense

16

Chapter 1

Short Exercise

Remember Joe? He mows one yard for

$30 and spends $5 to refill the gas

tank. What are his (a) assets, (b) liabilities, and (c) owner's equity now? What

are the (d) revenues and (e) expenses?

Answers: (a) $7,025 (Cash $5,025 and

$2,000 in equipment). (b) $2000 (no

change). (c) $5,025 (Joe's share of the

business has increased by $25). (d)

Revenues are $30. (e) Expenses are $5.

Net Income

Excess of total revenues over total

expenses. Also called net earnings or

net profit.

Expenses have the opposite effect of revenues. Expenses cause the business

to shrink, as shown by the decreased balances of assets and owner’s equity.

Each expense is recorded separately. The expenses are listed together here for

simplicity. We could record the cash payment in a single amount for the sum of

the four expenses: $3,300 ($600 + $1,100 + $1,200 + $400). In all cases, the “balance” of the equation holds, as we know it must.

After any transaction, the business can prepare a balance sheet, as we illustrated

earlier. Click on “Print Balance Sheet” and the software will produce the document.

After Gillen’s revenue and expense transactions, Gay Gillen will want to

know how well the travel agency is performing. Is the business profitable, or is it

losing money? To answer this important question, Gillen can use QuickBooks to

print an income statement. An income statement reports revenues and expenses

to measure profits (called net income, net earnings, or net profit) and losses

(called net loss). Gillen’s income statement at April 30 would appear as follows:

Gay Gillen eTravel

Net Loss

Excess of total expenses over total

revenues.

Income Statement

Month Ended April 30, 20X5

Revenue:

Service revenue ($5,500 + $3,000) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Expenses:

Salary expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rent expense, office . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lease expense, computer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Utilities expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Total expenses. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$8,500

$1,200

1,100

600

400

3,300

Net income . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$5,200

The business had more revenues than expenses, so it was profitable during

April. It earned net income of $5,200—not bad for a start-up company. We will

revisit the income statement later.

TRANSACTION 7: PAYMENT ON ACCOUNT Gillen pays $300 to the store where

she purchased $500 worth of office supplies in transaction 3. In accounting, we say

that she pays $300 on account. The effect on the accounting equation is a decrease in

the asset Cash and a decrease in the liability Accounts Payable, as shown next.

ASSETS

Cash

Bal. 12,200

(7) − 300

Bal. 11,900

+

Accounts

Receivable

+

LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Office

Supplies

+

Accounts

Payable

Land

3,000

500

20,000

3,000

500

20,000

35,400

=

+

500

−300

200

Gay Gillen,

Capital

35,200

35,200

35,400

The payment of cash on account has no effect on Office Supplies because the payment does not affect the supplies available to the business. Likewise, the payment

on account does not affect expenses. Gillen was paying off a liability, not an expense.

TRANSACTION 8: PERSONAL TRANSACTION

Gillen remodels her home at a

cost of $40,000, paying cash from personal funds. This event is not a transaction

of Gay Gillen eTravel. It has no effect on the travel agency and therefore is not

recorded by the business. It is a transaction of the Gay Gillen personal entity, not

Gay Gillen eTravel. This transaction illustrates the entity concept.

Accounting for Business Transactions

TRANSACTION 9: COLLECTION ON ACCOUNT In transaction 5, Gillen performed services for a client on account. The business now collects $1,000 from

the client. We say that Gillen collects the cash on account. Gillen will record an

increase in the asset Cash. Should she also record an increase in service revenue?

No, because she already recorded the revenue when she earned it in transaction

5. The phrase “collect cash on account” means to record an increase in Cash and

a decrease in Accounts Receivable. The effect on the accounting equation of Gay

Gillen eTravel is

ASSETS

Cash

Bal. 11,900

(9) + 1,000

Bal. 12,900

Teaching Tip

All revenue transactions affect either

assets or liabilities. All expense transactions also affect an asset or a liability.

On the other hand, many transactions

involving assets or liabilities don't

have anything to do with revenues or

expenses.

LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Accounts

Receivable

+

17

+

Office

Supplies

3,000

−1,000

2,000

+

Accounts

Payable

Land

500

20,000

500

20,000

=

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

200

35,200

200

35,200

35,400

35,400

✔ Starter 1-9

Total assets are unchanged from the preceding total. Why? Because Gillen

merely exchanged one asset for another. Also, total liabilities and owner’s equity

are unchanged.

TRANSACTION 10: SALE OF LAND Gillen sells some land owned by the

travel agency. The sale price of $9,000 is equal to Gillen’s cost of the land. Gillen’s

business receives $9,000 cash. The effect on the accounting equation of the travel

agency follows:

ASSETS

Cash

LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

Accounts

Receivable

+

Bal. 12,900

(10) + 9,000

Bal. 21,900

+

Office

Supplies

2,000

500

2,000

500

+

Accounts

Payable

Land

20,000

− 9,000

11,000

=

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

200

35,200

200

35,200

35,400

35,400

TRANSACTION 11: WITHDRAWAL OF CASH Gillen withdraws $2,000 cash

from the business for personal use. The effect on the accounting equation is

ASSETS

Cash

Bal. 21,900

(11) − 2,000

Bal. 19,900

+

Accounts

Receivable

+

2,000

Office

Supplies

500

2,000

500

33,400

+

Land

11,000

11,000

=

LIABILITIES

+

OWNER’S

EQUITY

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

200

35,200

− 2,000

33,200

200

33,400

Gillen’s withdrawal of $2,000 cash decreases the asset Cash and also the owner’s

equity of the business. The withdrawal does not represent an expense because the cash

is used for the owner’s personal affairs. We record this decrease in owner’s equity as

Withdrawals or as Drawings. The double underlines below each column indicate

a final total.

✔ Starter 1-10

TYPE OF

OWNER’S EQUITY

TRANSACTION

Owner withdrawal

18

Chapter 1

The Language of Business

Regulating Accounting

Business Organizations

Concepts and Principles

The Accounting Equation

Business Transactions

Evaluating Business Transactions

Exhibit 1-7 summarizes Gay Gillen eTravel’s transactions. Panel A lists the

details of the transactions, and Panel B shows the analysis. As you study the

exhibit, note that every transaction maintains the equality

■ Evaluating Transactions

Prepare the financial statements

balance sheet, financial statements,

income statement, statement of cash

flows, statement of owner’s equity

Income Statement

Summary of an entity's revenues,

expenses, and net income or net loss

for a specific period. Also called the

statement of earnings or the

statement of operations.

ASSETS = LIABILITIES + OWNER’S EQUITY

The Financial Statements

After analyzing transactions, we need a way to present the results. We look

now at the financial statements, which report the entity’s financial information

to interested parties such as Gay Gillen. If Gillen ever needs a loan, her banker

will also want to see her financial statements. Earlier we prepared Gillen’s

income statement and balance sheet after a few transactions. Now we are

ready to examine all the business’s financial statements at the end of the

period.

The financial statements are the

■

Income statement

■

Balance sheet

■

Statement of owner’s equity

■

Statement of cash flows

I NCOME STATEMENT

The income statement presents a summary of an

entity’s revenues and expenses for specific period of time, such as a month or a

year. The income statement, also called the statement of earnings or statement

of operations, is like a video—it presents a moving picture of operations during

the period. The income statement holds one of the most important pieces of

information about a business—whether it earned:

■

■

Net income (total revenues greater than total expenses) or

Net loss (total expenses greater than total revenues)

Net income is good news about operations. A net loss is bad news. What was the

result of Gay Gillen eTravel’s operations during April? Good news—the business

earned net income (see the top part of Exhibit 1-8, page 21).

Statement of Owner's Equity

Summary of the changes in an entity's

owner's equity during a specific

period.

STATEMENT OF OWNER’S EQUITY The statement of owner’s equity shows

the changes in owner’s equity during a specific time period, such as a month or a

year, as follows:

Increases in owner’s equity come from:

■

Real-World Example

Have you ever known a small business

owner who used his business checkbook to pay for personal items? These

items may have been listed as expenses

on the tax return. They should have

been treated as withdrawals.

Statement of Cash Flows

Reports cash receipts and cash

payments during a period.

Owner investments

■

Net income

Decreases in owner’s equity result from:

■

Owner withdrawals

■

Net loss

BALANCE SHEET The balance sheet lists all the entity’s assets, liabilities, and

owner’s equity as of a specific date, usually the end of a month or a year. The balance sheet is like a snapshot of the entity. For this reason, it is also called the

statement of financial position (see the middle of Exhibit 1-8, page 21).

STATEMENT

OF CASH F LOWS The statement of cash flows reports the cash

coming in (cash receipts) and the amount of cash going out (cash payments) during a period. Business activities result in a net cash inflow (receipts greater than

payments) or a net cash outflow (payments greater than receipts). The statement of cash flows shows the net increase or decrease in cash during the period

and the ending cash balance. (We focus on the statement of cash flows in

Chapter 17.)

Evaluating Business Transactions

19

Analysis of Transactions, Gay Gillen eTravel

Exhibit 1-7

PANEL A—Details of Transactions

(1) Gillen invested $30,000 cash in the business.

(2) Paid $20,000 cash for land.

(3) Bought $500 of office supplies on account.

(4) Received $5,500 cash from clients for service revenue earned.

(5) Performed travel service for clients on account, $3,000.

(6) Paid cash expenses: computer lease, $600; office rent, $1,100; employee salary, $1,200; utilities, $400.

(7) Paid $300 on the account payable created in transaction 3.

(8) Remodeled Gillen's personal residence. This is not a transaction of the business.

(9) Collected $1,000 on the account receivable created in transaction 5.

(10) Sold land for cash at its cost of $9,000.

(11) Withdrew $2,000 cash for personal expenses.

PANEL B—Analysis of Transactions

ASSETS

Cash

(1)

+

Accounts

Receivable

+

30,000

(2)

−20,000

Land

+

Accounts

Payable

+

Gay Gillen,

Capital

Bal.

10,000

+30,000

20,000

30,000

10,000

500

+500

20,000

500

30,000

+ 5,500

Bal.

+ 5,500

15,500

500

20,000

500

15,500

+ 3,000

3,000

500

20,000

Service revenue

35,500

+3,000

Bal.

Owner investment

30,000

+500

(5)

TYPE OF

OWNER’S EQUITY

TRANSACTION

+20,000

(3)

Bal.

+

LIABILITIES

+30,000

Bal.

(4)

Office

Supplies

OWNER’S

EQUITY

500

Service revenue

38,500

−

(6)

−

(6)

− 1,100

− 1,100

Rent expense, office

(6)

− 1,200

− 1,200

Salary expense

(6)

−

−

Utilities expense

600

400

Bal.

(7)

Bal.

=

12,200

−

500

20,000

3,000

500

20,000

200

35,200

20,000

200

35,200

Not a transaction of the business

(9)

+ 1,000

−1,000

12,900

2,000

500

21,900

35,200

− 9,000

(10) + 9,000

Bal.

2,000

500

11,000

200

35,200

(11) − 2,000

Bal.

19,900

Lease expense,

computer

−300

(8)

Bal.

400

3,000

300

11,900

500

600

− 2,000

2,000

500

33,400

11,000

200

33,200

33,400

✔ Starter 1-11

Owner withdrawal

20

Chapter 1

Financial Statement Headings

Each financial statement has a heading giving three pieces of data:

■

■

■

Name of the business (such as Gay Gillen eTravel)

Name of the financial statement (income statement, balance sheet, and so

on)

Date or time period covered by the statement (April 30, 20X5, for the balance

sheet; month ended April 30, 20X5, for the income statement)

An income statement (or a statement of owner’s equity) that covers a year

ended in December 20X5 is dated “Year Ended December 31, 20X5.” A monthly

income statement (or statement of owner’s equity) for September 20X4 shows

“Month Ended September 30, 20X4,” or “For the Month of September 20X4.”

Income must be identified with a particular time period.

Evaluate business performance

Relationships Among the Financial Statements

Exhibit 1-8 illustrates all four financial statements. Their data come from the

transaction analysis in Exhibit 1-7 which covers the month of April 20X5. Study

the exhibit carefully. Specifically, observe the following in Exhibit 1-8:

1. The income statement for the month ended April 30, 20X5:

a. Reports April’s revenues and expenses. Expenses are listed in decreasing

order of their amount, with the largest expense first.

b. Reports net income of the period if total revenues exceed total expenses. If

total expenses exceed total revenues, a net loss is reported instead.

2. The statement of owner’s equity for the month ended April 30, 20X5:

a. Opens with the owner’s capital balance at the beginning of the period.

b. Adds investments by the owner and also adds net income (or subtracts net

loss, as the case may be). Net income or net loss come directly from the

income statement (see arrow ① in Exhibit 1-8).

c. Subtracts withdrawals by the owner. Parentheses indicate a subtraction.

d. Ends with the owner’s capital balance at the end of the period.

3. The balance sheet at April 30, 20X5:

a. Reports all assets, all liabilities, and owner’s equity at the end of the

period.

b. Reports that total assets equal total liabilities plus total owner’s equity.

c. Reports the owner’s ending capital balance, taken directly from the statement of owner’s equity (see arrow ②).

4. The statement of cash flows for the month ended April 30, 20X5:

a. Reports cash flows from three types of business activities (operating, investing, and financing activities) during the month. Each category of cash-flow

activities includes both cash receipts (positive amounts), and cash payments (negative amounts denoted by parentheses).

b. Reports a net increase in cash during the month and ends with the cash

balance at April 30, 20X5. This is the amount of cash to report on the balance sheet (see arrow ③).

Have you ever thought of having your own business? The Decision Guidelines

feature shows how to make some of the decisions that you will face if you start a

business. Decision Guidelines appear in each chapter.

Evaluating Business Transactions

Exhibit 1-8

Gay Gillen eTravel

Financial Statements of Gay Gillen

eTravel

Income Statement

Month Ended April 30, 20X5

Revenue

Service revenue. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Expenses:

Salary expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rent expense, office . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lease expense, computer . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Utilities expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Total expenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Net income . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$8,500

$1,200

1,100

600

400

3,300

$5,200

Gay Gillen eTravel

Statement of Owner's Equity

Month Ended April 30, 20X5

①

Gay Gillen, capital, April 1, 20X5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $

0

Add: Investments by owner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30,000

Net income for the month . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5,200

35,200

Less: Withdrawals by owner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (2,000)

Gay Gillen, capital, April 30, 20X5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $33,200

Balance Sheet

April 30, 20X5

$19,900

2,000

500

11,000

Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$33,400

Liabilities

Accounts payable . . . . . . .

②

$

200

33,200

✔ Starter 1-13

$33,400

✔ Starter 1-14

✔ Starter 1-15

Statement of Cash Flows*

Month Ended April 30, 20X5

Cash flows from operating activities:

Receipts:

Collections from customers ($5,500 + $1,000). . . . . . .

Payments:

To suppliers ($600 + $1,100 + $400 + $300) . . . . . . . . .

To employees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Net cash inflow from operating activities . . . . . . . .

Cash flows from investing activities:

Acquisition of land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sale of land. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Net cash outflow from investing activities . . . . . . .

Cash flows from financing activities:

Investment by owner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Withdrawal by owner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Net cash inflow from financing activities . . . . . . . .

Net increase in cash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cash balance, April 1, 20X5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Cash balance, April 30, 20X5 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

*Chapter 17 shows how to prepare this statement.

Discussion

Q: Which amount appears on both the

statement of owner's equity and the

balance sheet?

A: The ending balance in capital.

✔ Starter 1-12

Owner's Equity

Gay Gillen, capital. . . . . . .

Total liabilities and . . . . . .

owner's equity . . . . . . . .

Gay Gillen eTravel

③

Teaching Tip

Three of the financial statements

should be prepared in the order you

see them presented—Income

Statement, Statement of Owner's

Equity, and the Balance Sheet. This is

because the three statements are

linked together.

Discussion

Q: Which amount appears on both the

income statement and statement of

owner's equity?

A: Net income.

Gay Gillen eTravel

Assets

Cash. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Accounts receivable . . . . .

Office supplies . . . . . . . . . .

Land . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

$ 6,500

$ (2,400)

(1,200)

(3,600)

2,900

$(20,000)

9,000

(11,000)

$30,000

(2,000)

28,000

19,900

0

$19,900

22

Chapter 1

MAJOR BUSINESS DECISIONS

Suppose you open a business to take photos at parties at your college.You hire a professional photographer and line up suppliers for party favors and photo albums. Here are some factors you must consider if

you expect to be profitable.

Decision

Guidelines

How to organize the business?

If a single owner—a proprietorship.

If two or more owners, but not incorporated—a partnership.

If the business issues stock to stockholders—a corporation.

What to account for?

Account for the business, a separate entity apart from its owner

(entity concept).

Account for transactions and events that affect the business and

can be measured reliably.

How much to record for assets and liabilities?

Actual historical amount (cost principle).

How to analyze a transaction?

The accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Owner's Equity

How to measure profits and losses?

Income statement:

Revenues − Expenses = Net Income (or Net Loss)

Did owner's equity increase or decrease?

Statement of owner's equity:

Beginning capital

+ Owner investments

+ Net income (or − Net loss)

− Owner withdrawals

= Ending capital

Where does the business stand financially?

Balance sheet (accounting equation):

Assets = Liabilities + Owner's Equity

Goal: Create a simple spreadsheet that a stockholder or

creditor could use to quickly analyze the financial performance

of a company.

Scenario: After buying some books and DVDs from

Amazon.com, you are thinking about investing some of your

savings in the company's stock. Before doing so, however, you

want to perform a quick check of the company's financial

performance. Use the Amazon.com Annual Report in Appendix

A to gather your data (also found online at www.amazon.com,

Investor Relations).

When you have completed your worksheet, answer the following question [Hint: See Amazon's Consolidated Balance

Sheets, Consolidated Statements of Operations (income statement), and Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows]:

1. Net income (loss) affects both stock prices and dividends.

What changes have occurred in Amazon's net income (loss)

over the past two years? If you were in management at

Amazon, would you include such a chart in your annual

report? Why or why not?

End of Chapter Summary Problem

Step-by-step:

1. Open a new Excel spreadsheet.

2. In column 1, create a bold-faced heading as follows:

a. Chapter 1 Excel Application Exercise

b. Amazon Financial Performance

c. Today's Date

3. Two rows down, enter the following labels (one in each row):

a. Income Statement Data (bold)

b. Net Income (Loss) (in 000's)

c. Percentage Change

4. Two rows below your heading, starting in the second column, set up three column headings, beginning with 2000 and

ending with 2002 (or the last three fiscal years, if different

from these).

5. Using the Amazon annual report, enter the net income (loss)

data for the past three years, and use formulas to calculate

the percentage change from year to year.

6. Enter the current assets and current liabilities data for at

least two years.

7. Use the Chart Wizard to create a column chart showing

how net income has changed (in percent).Title the chart

“Net Income (Loss) Trend” and use the “percentage change”

data for the chart data range. Position the chart appropriately on your worksheet.

8. Format all cells appropriately (width, dollars, percent, decimal places).

9. Save your worksheet and print a copy for your files.

END OF CHAPTER

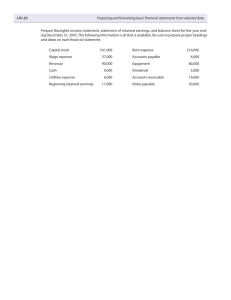

Jill Smith opens an apartment-locater business near a college campus. She is the sole

owner of the proprietorship, which she names Campus Apartment Locators. During

the first month of operations, July 20X6, she engages in the following transactions:

a. Smith invests $35,000 of personal funds to start the business.

b. She purchases on account office supplies costing $350.

c. Smith pays cash of $30,000 to acquire a lot next to the campus. She intends to use the

land as a future building site for her business office.

d. Smith locates apartments for clients and receives cash of $1,900.

e. She pays $100 on the account payable she created in transaction (b).

f. She pays $2,000 of personal funds for a vacation.

g. She pays cash expenses for office rent, $400, and utilities, $100.

h. The business sells office supplies to another business for its cost of $150.

i. Smith withdraws cash of $1,200 for personal use.

Required

1. Analyze the preceding transactions in terms of their effects on the accounting equation of Campus Apartment Locators. Use Exhibit 1-7 as a guide, but show balances

only after the last transaction.

2. Prepare the income statement, statement of owner’s equity, and balance sheet of the

business after recording the transactions. Use Exhibit 1-8 as a guide.

Solution

Requirement 1

PANEL A—Details of transactions

(a) Smith invested $35,000 cash to start the business.

(b) Purchased $350 of office supplies on account.

(c) Paid $30,000 to acquire land as a future building site.

(d) Earned service revenue and received cash of $1,900.

(e) Paid $100 on account.

(f) Paid for a personal vacation, which is not a transaction of the business.

(g) Paid cash expenses for rent, $400, and utilities, $100.

(h) Sold office supplies for cost of $150.

(i)

Withdrew $1,200 cash for personal use.

23

Summary Problem

24

Chapter 1

PANEL B—Analysis of transactions:

ASSETS

Cash

+

Office

Supplies

+

Land

LIABILITIES

+

OWNER’S

EQUITY

Accounts

Payable

+

Jill Smith,

Capital

(a) +35,000

+350

(b)

+35,000

Owner investment

+ 1,900

Service revenue

−

400

Rent expense

−

100

Utilities expense

+350

(c) −30,000

+30,000

(d) + 1,900

(e) −

TYPE OF OWNER’S

EQUITY TRANSACTION

=

100

−100

(f) Not a transaction of the business

(g) −

400

−

100

(h) +

150

(i)

Bal.

−150

− 1,200

5,250

− 1,200

200

30,000

35,450

250

Owner withdrawal

35,200

35,450

Requirement 2:

Financial Statements of Campus Apartment Locators

Campus Apartment Locators

Income Statement

Month Ended July 31, 20X6

Revenue:

Service revenue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Expenses:

Rent expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Utilities expense . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Total expenses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Net income. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

$1,900

$400

100

500

$1,400

Campus Apartment Locators

Statement of Owner’s Equity

Month Ended July 31, 20X6

Jill Smith, capital, July 1, 20X6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $

0

Add: Investment by owner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35,000

Net income for the month . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,400

36,400

Less: Withdrawals by owner. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (1,200)

Jill Smith, capital, July 31, 20X6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $35,200

Campus Apartment Locators

Balance Sheet

July 31, 20X6

Assets