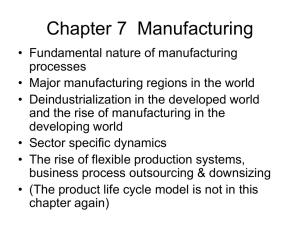

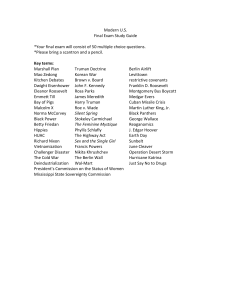

01 Deindustrialization: Affects and Effects A Case Study of Indonesia and Other G20 Countries . . . Nareswari Tarisa Kirana SMA Pribadi Bandung 02 Abstract Deindustrialization has been a hot topic in the last decade. This interesting phenomenon has happened to major developed countries in the world. Deindustrialization, most visible in the United States and Europe, is also visible in several Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, and India. It isn’t an uncommon phenomenon to be found in high GDP countries as such the G20. Unsurprisingly, deindustrialization has caused substantial concern in the afflicted countries, sparking a heated debate about its causes and expected consequences. Many people are concerned about deindustrialization and believe it has contributed to rising income disparity in the United States and high unemployment in Europe. This paper aims to analyze the state and implications of deindustrialization in Indonesia and some G20 countries. Moreover, this paper aims to give solution to improve economic growth by industrial approach in Indonesia. 03 Table of Contents Abstract.................................................................................................................................................. 2 Overall View of Deindustrialization: Definition, Parameters, and Potential Effects .............................. 4 In the Case of Indonesia: Is It Deindustrializing? .................................................................................... 4 In the Case of Other G20 Countries: An Analysis on EU, UK, USA, East Asia, and India ......................... 7 A. Comparisons of Early Cases: EU, USA, and Japan............................................................... 7 B. The UK ....................................................................................................................................... 8 C. Other East Asia: China, and South Korea.............................................................................. 9 D. India11 Economic Growth and Deindustrialization ........................................................................................... 13 Talks on Premature Deindustrialization................................................................................................ 16 Learning from Deindustrialization of Advanced Economies ................................................................. 16 A. China: A Remarkable Economic Growth ............................................................................. 16 B. Japan: Rapid Post-war Industrialization.............................................................................. 18 C. USA: A Regional Study Case from Pittsburgh and Cleveland ........................................... 20 Conclusion and Recommendation ........................................................................................................ 21 Citation.................................................................................................................................................. 23 04 Overall View of Deindustrialization: Definition, Parameters, and Potential Effects Deindustrialization is the decline of manufacturing within an economy. During deindustrialization, the declining share of manufacturing employment appears to correspond to a decline in the share of manufactured value added to GDP. Therefore, it is measured by manufacturing output (the value added created by manufacturing) and employment (the number of persons employed in manufacturing). There is a distinction between absolute decreases in these two factors and relative decreases in the proportion of manufacturing in overall output and employment. This distinction is critical because manufacturing, while shrinking in relative terms, remains large and important in an expanding economy. Trade competitiveness is another indicator of deindustrialization. This refers to the proportion of international markets occupied by manufactured exports from specific countries and regions. When such shares diminish, it indicates a decline in manufacturing competitiveness against other producers and a decrease in demand for its exports. Deindustrialization is not always a sign of failure in a country's manufacturing sector or the economy as a whole. On the other hand, it is a natural result of successful economic development and is often connected with growing living standards. This is not to say that deindustrialization cannot be connected to problems in the manufacturing sector or the economy as a whole. Manufacturing employment can be lost immediately as a result of system shocks such as a big increase in the real exchange rate. In such cases, the service sector may be unable to absorb a rapid rise in labor supply, resulting in increased unemployment or a slowing of the expansion of living standards. In the Case of Indonesia: Is It Deindustrializing? Despite the fact that manufacturing contributed the most to production in the early 2000s as the peak of industrialization, there has been a movement in economic structure away from the manufacturing sector and toward other sectors such as services and informal. Net exports have migrated away from manufacturing and toward other commodities and services, losing its competitiveness. The symptoms of deindustrialization such as the declining performance and growth deceleration of the manufacturing industry has been engulfing Indonesia's economy since the crisis hit hardest in 1997. 05 Sc: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files. Sc: World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files 06 Share of employment in each economic sector - Indonesia Sc: World Bank Database and, International Labour Organization. “ILO modelled estimates database” ILOSTAT The graphs above demonstrate that the average annual growth of the manufacturing industry's value-added after the crisis reached a negative of -11.4%, with its contribution to GDP falling 2% from 27% in 1997 to 25% in 1998. The value added from manufacturing contribution to GDP continued to fall until the year 2000, reaching 23%. This poor performance of the manufacturing industry's average annual growth rate in the post-crisis period is followed by the poor performance of the labor-absorbing industrial manufacturing sector, which accounted for only 1.03% during the period 1998-2007, compared to 7.16% in the pre-crisis period 1988-1997. This means that many people were laid off in these secondary industries. People who were formerly reliant and dependent on industrial industries for a living had become unemployed as a result of the crisis. In 2021, the percentage of value added from manufacture in Indonesia’s GDP was only 19%, a significant 13% fall from its peak of 32% in 2002. As mentioned before, one way to measure deindustrialization is through manufacturing output (the value created by manufacturing) and employment (the number of persons employed in manufacturing). Despite of the rapid output decline, employment in the manufacturing sector remains stagnant. Yet, this doesn’t debunk the fact that Indonesia is in the process of deindustrialization. This is because manufacturing employment has remained relatively stable, whereas agriculture employment has declined dramatically. It demonstrates that manufacturing 07 does not absorb many job transformations, therefore employment growth in manufacturing is slower than in the service sector, which has a significant contribution rise. The deindustrialization process that has occurred in Indonesia in recent years is not a natural result of the country's economic success, but rather the result of a series of shocks to the economy. The international trade and financial liberalization are the primary causes of deindustrialization in Indonesia, as practically all sectors in the country are neither competitive, innovative, or technologically advanced. They are quickly losing market share and competitiveness to global firms. The prospect of the middle-income trap should serve as a wake-up call to the Indonesian government about the dangers of deindustrialization. In the Case of Other G20 Countries: An Analysis on EU, UK, USA, East Asia, and India A. Comparisons of Early Cases: EU, USA, and Japan Employment by Sector as a Share of Total Civilian Employment (%) Sc: IMF Working Papers 1997 Manufacturing employment has steadily dropped as a proportion of civilian employment in most advanced nations since the early 1970s. The percentage of manufacturing employment in the group of industrial countries fell from over 28% in 1970 to around 18% in 1994. Deindustrialization began in earnest in the United States in the mid-1960s, and it has seen one of the sharpest decreases in the percentage of manufacturing employment, from over 28% in 1965 to 16% in 1994. In Japan, however, the percentage of manufacturing employment began to decline longer and more slowly from a peak of 27.4% in 1973 to around 23% in 1994. Manufacturing employment was comparably high in 1970 (a little more than 30 percent) among the combined European Union countries (EU-15), but the decrease since then has been severe, with manufacturing accounting for only 20% of total civilian employment in this group in 1994. Another aspect of this evolution has been a steady growth in the percentage of employment in services. Since 1960, there has been an almost continual growth in the 08 percentage of employment in the services sector. The United States has been a pioneer in this regard, having begun with a substantially bigger service sector (about 56% of civilian employment in 1960) and increased to a higher percentage of employment in services than any other modern country in 1994 (about 73%). Despite these variances, the overall picture is remarkably similar, most advanced economies have seen steady losses in manufacturing employment over the previous two decades, while services employment has increased significantly. B. The UK Sc: Office for National Statistics (ONS) of UK Being the site where the first industrial revolution had happened, UK also experienced relatively early deindustrialization. Many indicators show that since 1975 the country has moved from a state of relative industrial decline into a state of absolute industrial decline. Britain was responsible for a quarter of the world's manufactured goods exports in 1951, but just 7.9% in 1980. For the first time in almost a century, the country experienced an external trade deficit in manufactured products in 1983. 09 In its early days, deindustrialization of the UK resulted in major unemployment issue. Ever since and until now, UK has been experiencing continuous decline in its manufacturing sector. Yet, its unemployment rate has been declining even though it still fluctuates from time to time. The country’s shifted to a service-based nation. C. Other East Asia: China, and South Korea Share of employment in each economic sectors (%) – South korea Shares of value added in GDP (%) – South Korea 010 In terms of employment and nominal output, the Korean economy has been deindustrialized since the late 1980s, with the manufacturing sector's share of the economy decreasing while the service sector's share has increased; however, the Korean economy has not yet reached the stage of deindustrialization in terms of real output. Manufacturing jobs started to fall in the late 1980s. Manufacturing employment, which had been steadily increasing throughout the 1970s, peaked at 28% of total employment in 1989, then began to decline until it reached about 20% in 2001. Since peaking in the late 1980s, the nominal proportion of manufacturing production has also been on a steady decreasing trend. In contrast to its somewhat declining proportion at current prices, manufacturing's share of GDP in value-added terms at constant prices continued to rise over these decades. That is, after being relatively stable until the late 1990s after rising to 28% in the late 1980s, its proportion has climbed considerably in recent years to over 34%. This is substantially reinforced by the fact that manufacturing sector growth rates in real value-added terms have stayed greater than service sector growth rates since the 1970s. Deindustrialization in Korea is neither due to a lack of competitiveness in domestic industry or a substantial increase in North-South trade. It is mostly the result of successful economic expansion, which has been fueled by substantially quicker productivity growth in the manufacturing sector and a shift in consumption habits as income levels rise. Value added of each sector (% of GDP) – China Sc: World BankDatabase 011 Share of employment in each sector (%) – China Sc: World Bank Database China's industrial employment growth stalled in 2012. Following then, the Chinese economy began to deindustrialize. As a proportion of overall employment, industrial employment fell as the industry shed millions of jobs. This trend of deindustrialization is expected to continue. In 2019, China's industrial sector nevertheless employed a higher proportion of people than other upper-middle-income nations, where industry accounted for an average of 22% of jobs. This rate was higher than 27% in China. Similarly, China's manufacturing sector contributed more to GDP than equivalent sectors in other nations. In 2019, the value contributed by China's manufacturing sector as a part of GDP was more than 27 percent, over 15 percentage points more than the upper-middle-income average, signaling that more deindustrialization is on the way. D. India India deindustrialized in the 18th and 19th centuries with two diverse cause of deindustrialization. The first period, which lasted from roughly 1750 to 1810, was caused by the disintegration of the Mughal empire. As central authority diminished, revenue farming spread, the rent burden increased, conflicts increased the cost of agricultural inputs, and regional commerce within the subcontinent fell, all of which served to reduce grain agriculture production. Grain prices and the nominal wage climbed. As a result, Indian textile producers' own-wage grew, reducing India's competitiveness in the export market. Furthermore, the intersectoral trade conditions shifted against textiles, promoting a shift to agricultural 012 commodities manufacturing. India's proportion of global industrial production declined faster than in any other non-European country. During the second period from 1810 to 1860, productivity gains due to the adoption of the factory system drove down the relative price of textiles around the world, a trend that was amplified in India as a global transportation revolution drove down the price of textiles even further everywhere in the periphery. Thus, while the relative security of Company prevented the drop in Indian agricultural output during this era, and while the growth in grain prices slowed and eventually steadied, the relative price of grain continued to climb. India had completed a century-long two-part transition from net exporter to net importer of textiles by 1860. A secular growth in terms of commerce came to an end, turned around, and began a long run decline that lasted until the late 1930s. As trade terms deteriorated, the importcompeting industry (textiles) was no longer punished by negative external price shocks. By the late nineteenth century, India's deindustrialization had ended, and the country had begun a sluggish reindustrialization process. Sc: World Bank Database 013 Sc: World Bank Database Sc: World Bank Database In the last periods, India’s manufacturing sector output growth rate had fallen to a negative 2.9% in 2019 from 13.1% per year in 2015, yet it managed to bounce back to 9.9% in 2021. However, it’s safe to say that India hasn’t fallen back to another state of deindustrialization and merely having a stagnation for now. Economic Growth and Deindustrialization Industrialization has had a significant influence in economic progress. It is well understood that rapid industrialization leads to a faster pace of economic expansion. As the share of an economy's manufacturing sector transfers to the service sector, productivity improvement and economic development necessarily declines. However, it should be highlighted that the rate of productivity growth in the service sector is not always low, and that 014 an increase in the share of the service sector does not always result in a decrease in the growth rate. The graphs below show that even though not always significant and do not happen in the same rate, the general trend of manufacturing output and GDP often go hand in hand. 015 Sc: World Bank Database 016 Talks on Premature Deindustrialization Even though it has been stated multiple times that deindustrialization can occur as a natural phenomenon resulting from successful economic development and rising living standards in advanced economies, this is not the case in many developing countries such as India, Indonesia, and those in Latin Americas. Deindustrialization in Indonesia is a negative indicator of poor economic performance since it is not a natural result of the country's rapid expansion. This type of deindustrialization is referred to as premature deindustrialization. The national economy transitioned to the services sector before the national industry became strong and established in a short period of time. When the manufacturing industry is deindustrialized prematurely, the service sector activities that may replace it are more low-skilled, nontradeable, retail, or have no big return-to-scale features. The negative deindustrialization in Indonesia was caused by a combination of domestic and global forces. A reduction in fixed capital investment, a decline in international trade performance, a decline in the value of raw material imports, and a flood of imported products (particularly consumer goods), are all elements leading to negative deindustrialization. In Indonesia, the factors of premature deindustrialization emphasize on the lack of infrastructure, restricted energy supply, an availability of import materials, limited financing, various disincentives in industrial sectors, and poor export. Premature deindustrialization causes a country's development to lag behind its transition to middle-income status. It has failed to join the club because it has not been able to gradually progress up the "value chain" of its manufactured items to join the high-income countries. Learning from Deindustrialization of Advanced Economies A. China: A Remarkable Economic Growth China industrialized early, and it has shown a rapid spread of industrialization through a variety of tactics. While Indonesia has a history of premature deindustrialization, the manufacturing industry lacks growth-oriented characteristics. 017 Industrial growth and value-added per worker, China, 1992–2020 Sc: World Development Indicators. Despite of its decreasing share of manufacture to GDP, China’s output per worker remains increasing each year. China's industrial boom has been matched by a rapidly increasing percentage of China's exports in international commerce. The merchandise trade-to-GDP ratio dramatically expanded, rising from 10% on average in the 1970s to 25% in the 1980s and 37% in the 1990s. It peaked at 53% on average in the 2000s before falling to 38% between 2011 and 2019. Three key features of China's growth experience stand out: pragmatism, adaptability, and gradualism. Through proactive macroeconomic management, financial reform and financial sector expansion, and carefully controlled capital account liberalization, these three factors were firmly integrated in China's macro-policy framework. Transportation infrastructure development, China, 1978–2018 Sc: Database of the statistics bureau of the People's Republic of China. 018 China has made full use of its demographic advantages and a surplus of labor to boost its standing in the worldwide labor market. Furthermore, China has substantially invested in its transportation and information infrastructures, as well as exploited its industrial policies to climb the worldwide value chains. Telecommunications and Internet infrastructure development, China, 1999–2018 Sc: Database of the statistics bureau of the People's Republic of China China has gradually created a national innovation system by expanding its investments in research, technology, and human resources. These expenditures aided the country in closing the digital divide with advanced countries. China did not construct its policies to promote digitalization in the same way that the West did, but rather to meet its own ground realities. It focused on building its digital infrastructure, prioritizing ICT infrastructure and ICT skills of its population, increasing the demand and supply of ICT products and services. It then connected ICT infrastructure with manufacturing and shifted its focus on sectoral interventions. B. Japan: Rapid Post-war Industrialization Despite have been experiencing deindustrialization, Japan remains as one of the strongest economic power in the world. After WWII had ended, did not take long for Japan to begin the fast-economic expansion known as the "Japanese miracle," and the Japanese economy has since become a powerhouse in terms of its effect on the global economy. 019 The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) has played the major leadership role in executing industrial policies. The postwar Japanese industrial strategies implemented by MITI may be grouped into five primary groups. 1. Policies that shape the industrial structure by fostering and safeguarding emerging industries through interventions and incentives, as well as correcting and supporting the "exit process" of failing sectors. 2. Policies that address market failures caused by variables such as imperfect market conditions and asymmetric knowledge. That is, policies that provide accurate information and use policy measures such as subsidies and the tax system to repair market failures and drive resource allocation in desirable directions. 3. Policies aiming at formally interfering in individual industrial entities and increasing economic wellbeing. Policies that aim to actively intervene in the competitive structure and resource distribution within industries, such as recession cartels and capital-investment cartels. 4. Policies are implemented mostly on political rather than economic considerations. Policies for voluntary export limitations and multilateral agreements to resolve issues such as trade friction are examples of this. 5. Also included in the area of industrial policy are macroeconomic policies, income distribution policies, pollution control policies, regional policies, R&D promotion policies, and policies for SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises). 020 C. USA: A Regional Study Case from Pittsburgh and Cleveland Pittsburgh and Cleveland were among the largest U.S. cities in the first half of the 20th century recognized for their industrial prowess Manufacturing accounted for the bulk of the top-10 most-concentrated industries in both metro regions with over 5,000 workers in 1980. Whereas Pittsburgh's industrial base was dominated by primary metals, Cleveland's manufacturing employment was varied. As manufacturing employment in the United States fell sharply in the early 1980s, both cities experienced population and job losses around the 1981–1982 recession. Between 1980 and 1985, Pittsburgh lost 6% of its jobs and 4% of its population as more than 100,000 people in the steel and allied sectors were laid off. Cleveland lost 2% of its population and 2% of its employment. Although layoffs were less severe in Cleveland, the city was still recuperating from an economic crisis in the late 1970s. As traditional manufacturing jobs disappeared, state governments in Pennsylvania and Ohio committed public funds in industrial strategies targeted at fostering the creation of sophisticated technology businesses in Pittsburgh and Cleveland, respectively. The Western Pennsylvania Advanced Technology Center (WPATC) was applied for jointly by the metro area's two principal research universities, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) and the University of Pittsburgh (Pitt). In 1985, a coalition of government and university leaders in Pittsburgh unveiled Strategy 21, a plan for economic revitalization that included a number of proposed high-tech projects as well as more traditional infrastructure projects in the region, such as highway investment and airport renovation. Between 1980 and 2015, the Pittsburgh metro region enjoyed personal per capita income growth that was in the top quartile of U.S. metro areas, but Cleveland's growth was below the median. Pittsburgh's job growth was likewise in the higher percentile for U.S. metros, outpacing Cleveland's. Pittsburgh's change can be explained in part by industrial policy that has the potential to empower new local economic players. One of the key distinctions between Pittsburgh and Cleveland industrial policy was who drove the implementation: universities in Pittsburgh vs the business sector in Cleveland. Whereas previous studies of industrial strategy have lamented the difficulty of selecting winners, these case studies emphasize the necessity of selecting implementers. 021 Conclusion and Recommendation Deindustrialization has been a global phenomenon in the last decades. It is now happening in both developed and developing countries. Following de-industrialization, policy discussion has centered on the significance of manufacturing to city and regional economies. Some claim that the move to services is unavoidable and proof of an economy's progress, modernity, and maturity. Others argue that manufacturing is still critical to local, regional, municipal, and national economic development. Manufacturing is known as the "flywheel of growth" because its growing returns create quicker output gains, which promote faster economic expansion. Manufacturing plays this generative role because, when compared to services, it has a greater potential for technological progress and innovation spillovers that enable productivity gains, dynamic increasing returns to scale, strong backward and forward input-output linkages through supply chains, and the ability to absorb surplus labor from other sectors. However, it is no doubt that deindustrialization might results in economic and political problems. The chance of this problem happening is way bigger in those who experience premature deindustrialization, Indonesia is no exception of this. Therefore, this paper offers some recommendation regarding the solution of Indonesia’s deindustrialization problems based on the national condition and approaches that have been done by more advanced economies such as China, Japan, and USA. 1. Human resources must be increased via education and skill development so that future human resources are prepared with better quality of competence (high-skilled). With high-quality resources, human resources will be ready to enter service sectors with high productivity and tradability, such as information and communication technology (ICT), finance, and other service sectors that can replace manufacturing as a growth engine. The aim of this approach is to develop digital transformation (as such in China) that plays a key role in building export competitiveness and industrialization efforts. 2. Given the length of time that deindustrialization has happened, the government must take timely and suitable steps to re-industrialize Indonesia so that deindustrialization may be overcome immediately. With reindustrialization, it is expected that the role of manufacturing as a growth engine will encourage other sectors to grow faster, increasing Indonesia's economic growth and GDP per capita, and ultimately improving the welfare of Indonesians into developed countries. 022 3. Developing industrial policies that involves local economic players and SMEs. SMEs have been playing a key role for large firms as supporting industries. In addition, it is well known that some small firms such as venture business are very vital and aggressive. In macroeconomic sense, Low wage and labor-intensive technology of small firms contributes to absorb the growing labor forces and help to reindustrialize Indonesia. This is an approach that’ve been used in Japan, where small firms have contributed in absorbing the growing labor forces in the Japanese economy during the post-war period. 4. Manufacturing growth must be done evenly across the archipelago. The focus of manufacturing development is done outside of Java, particularly in eastern part of Indonesia, to reduce the imbalance of growth in Indonesia, where industrialization is synonymous with development. This first can be done by creating even distribution of infrastructure as it’s been proven as boosting industrialization and growth of economy as such in China and Pittsburgh. These recommendations are using approaches that aims for industrial boosts and increasing quality of human resource. The growth of industry (in this case referring to the manufacturing sector) will produce large value added that contributes to the growth of the country’s GDP. Furthermore, by creating educated and skilled population, Indonesia can become more prepared to face shifts to the service sector. 023 Citation Andriyani, V. E., & Irawan, T. (2018). Identification of premature deindustrialization and its acceleration in Indonesia (period 1986-2015). Jurnal Ekonomi dan Kebijakan Pembangunan, 7(1), 78-101. Armstrong, B. (2021, June 11). Industrial Policy and Local Economic Transformation: Evidence From the U.S. Rust Belt. Economic Development Quarterly, 35(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912424211022822 Banga, Rashmi & Fortunato, Piergiuseppe & Gottschalk, Ricardo & Hawkins, Penelope & Wang, Dawei. (2022). CHINA'S STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATION WHAT CAN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES LEARN?. Boltho, A., & Boltho, A. (1985). Was Japan’s industrial policy successful? Cambridge Journal of Economics, 9(2), 187–201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23597007 Chakraborty, Judhajit & Rayaprolu, Nagaraj. (2020). Has India Deindustrialised Prematurely? A Disaggregated Analysis. Economic and Political Weekly. LV. 40-47. China is deindustrializing but has a way to go to match other upper-middle-income economies. (2021, February 26). PIIE. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/china-deindustrializinghas-way-go-match-other-upper-middle-income-economies Clingingsmith, D., & Williamson, J. G. (2005). India’s deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th centuries. Cambridge: Harvard University. Kim, H. J. (2006). The shift to the service economy: Causes and effects. Institute for monetary and economic research, 7(7), 1-49. Mansur, Ahmad. (2008, January). Is Indonesia Undergoing A Process Of DeIndustrialization?. Economics of Development (ECD). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2105/6708 MOUNFIELD, P. R. (1984). The deindustrialisation and reindustrialisation of the UK. Geography, 69(2), 141–146. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40570813 Nishijima, S. (2012). Japanese industrial policy. 024 Pike, A. (2020). Deindustrialization. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 213– 222. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-102295-5.10040-x Puspitawati. (2021). Indonesian Industrialization and Industrial Policy: Peer Learning from China’s Experiences. ECIDC PROJECT PAPER No.7, UNCTAD/BRI PROJECT/RP7. Rodrik, D. (2016). Premature deindustrialization. Journal of economic growth, 21, 1-33. Rowthorn, & Ramaswamy. (1997, September). Deindustrialization–Its Causes and Implications. International Monetary Fund. World Bank Open Data. (n.d.). World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org 임현준. (2004). Is Korea Being Deindustrialized?. [BOK] Economic Papers, 7(1), 0-0.