Principles of Taxation for Business and Investment Planning 2023 Edition By Sally, Shelley, Sandra, Kubick

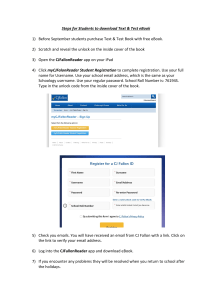

advertisement