The Athlete Life Quality Scale Development and Psychometric Anal

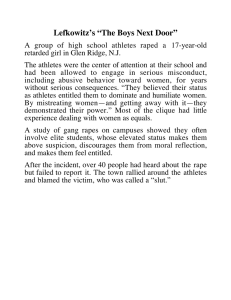

advertisement