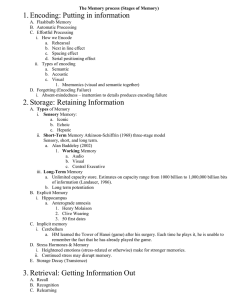

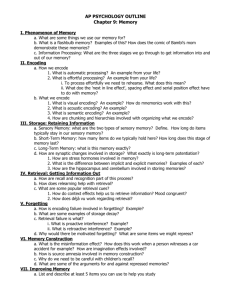

On Memory: Discussing Encoding & Forgetting 1. HOW DO PSYCHOLOGISTS DESCRIBE THE HUMAN MEMORY SYSTEM? Memory, according to Myers (2010), is described as the “persistence of learning over time” (p. 345). As previously discussed, learning involves experience and practice in order to change one’s behaviour permanently. In 1968, Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin proposed a model of human memory that separates the process of encoding, storing and retrieving into three stages: (i) a person registers fleeting sensory “memories”, some of which are, (ii) processed into on-screen “short-term memories”, a tiny fraction of which are, (iii) encoded for “long-term memory” and, possibly, later retrieval. This became known as the classical model of memory. Subsequently, researchers have argued in recent times that we also register some information automatically, and bypass the first two stages mentioned above. These contemporary researchers thus prefer the term “working memory” (rather than “short-term memory”) to emphasise the active processing in the second stage. 2. WHY DO WE FORGET? Myers (2010) says that memory involves the “thoughts of abstraction”, that is, the thoughts that involve generalising, organising and evaluating (p. 350). Against these thoughts, Schacter (1999) outlines the “seven sins” that get in the way of committing information to memory. First, the “sins” of forgetting: (i) absent-mindedness (inattention to details), (ii) transience (storage decay) and (iii) blocking (the inaccessibility of stored information). Second, the “sins” of distortion: (i) misattribution (confusing sources of information), (ii) suggestibility (the lingering effects of misinformation) and (iii) bias (belief-coloured recollections). Third is the “sin” of intrusion, that of persistence, or unwanted memories. Based on this understanding, then, there are three forms of forgetting, according to Myers (2010): encoding failure, storage decay and retrieval failure (p. 351). Encoding failure is the gradual inability to pay attention quickly enough for external stimuli to be remembered on short notice, as in elderly people who require much more time and effort to try and remember things they have just experienced, or information they have just received. Storage decay is a term for “discarded thoughts”, or thoughts that one actually chooses to forget. Ebbinghaus (1885) illustrated a “forgetting curve”, which posits that the course of forgetting is initially rapid, then levels off slowly (p. 351). Retrieval failure is described as the inaccessibility of a memory because one does not have enough information to retrieve it, hence the memory becomes elusive. A second aspect of forgetting is interference. According to Myers (2010), learning something new may cause something else to be forgotten. In pro-active interference, something learned earlier disrupts the recall of something experienced later i.e. forward acting. Collecting more information clutters the mental “attic” despite the fact that it never fills. In retro-active interference, new information affects that which was learned earlier. Jenkins and Dalenbach (1924) argue that “forgetting is not so much a matter of the decay of old impressions and associations as it is a matter of interference, inhibition or obliteration of the old by the new.” (p. 354). A third aspect of forgetting is that which is motivated. Sigmund Freud proposed that we “repress” difficult memories to alleviate anxiety and guard the sense of self. However, he believed that these memories linger in order to be retrieved later, either in incidental situations or intentionally, as in therapy. This repression was foundational to Freud’s psychology, and is a theory in his psychoanalysis, in which repression is a “defence mechanism” against thoughts, feelings and memories that induce anxiety. REFERENCES Myers, D. G. (2010). Psychology (9th ed.). Worth Publishers