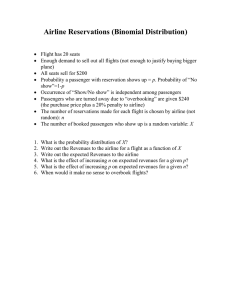

https://www.nytimes.com/1987/03/04/business/the-art-of-devising-airfares.html THE ART OF DEVISING AIR FARES By Eric Schmitt March 4, 1987 See the article in its original context from March 4, 1987, Section D, Page 1 Buy Reprints New York Times subscribers* enjoy full access to TimesMachine—view over 150 years of New York Times journalism, as it originally appeared. SUBSCRIBE *Does not include Crossword-only or Cooking-only subscribers. About the Archive This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them. Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions. In the airline business, it is sometimes called the dark science. The latest round of fare wars, however, has put a spotlight on how carriers use state-ofthe-art computer software, complex forecasting techniques and a little intuition to divine how many seats at what prices they will offer on any given flight. The aim of this inventory, or yield, management, is to squeeze as many dollars as possible out of each seat and mile flown. That means trying to project just how many tickets to sell at a discount without running out of seats for the business traveler, who usually books at the last minute and therefore pays full fare. Too many wrong projections can lead to huge losses of revenue, or even worse. The inability of People Express to manage its inventory of seats properly, for example, was one of the major causes of its demise. ''It's a sophisticated guessing game,'' said Robert E. Martens, vice president of pricing and product planning at American Airlines, the carrier that has the most sophisticated technology for yield management, according to airline analysts and consultants. ''You don't want to sell a seat to a guy for $69 when he's willing to pay $400.'' It May Be Easier Now With the industry now adopting very low discount but nonrefundable fares, the complex task of managing seat inventory may become easier because airlines will be better able to predict how many people will show up for a flight. Some airlines have already seen a drop in their no-shows, which means they can overbook less and spare more customers from being bumped. The nonrefundable fares could also enable carriers to sell more discount seats weeks before a flight, rather than putting them on sale at the last minute in an effort to fill up the plane. American's inventory operation illustrates just how complicated the process can be. At the airline's corporate headquarters here, 90 yield managers are linked by terminals to five International Business Machines mainframe computers in Tulsa, Okla. The managers monitor and adjust the fare mixes on 1,600 daily flights as well as 528,000 future flights involving nearly 50 million passengers. Their work is hectic: A fare's average life span is two weeks, and industrywide about 200,000 fares change daily. Few Discounts on Fridays American and the other airlines base their forecasts largely on historical profiles of each flight. Business travelers, for example, book heavily on many Friday afternoon flights, but often not until the day of departure. The airlines reserve blocks of seats for those frequent fliers. Few, if any, discounts are made available. ''Good luck getting a 'Q fare' from New York to Chicago on Friday afternoon,'' said James J. Hartigan, president of United Airlines, using the industry's parlance for the low-priced, supersaver ticket. ''It's like winning the New York State Lottery.'' The same route at midday on a Wednesday, however, begs for passengers, so the airline might discount more than 80 percent of its seats to draw leisure travelers and others with more flexible schedules. Passengers Angered Many passengers, attracted by advertisements trumpeting deep discounts but unaware that fare allocations change from flight to flight, have expressed anger at the carriers and travel agents when the cheap seats were unavailable. To help clear up the confusion, Continental Air Lines is now running ads noting the relative demand of certain routes, thus giving some sense of the supply of discount seats. Overbooking, too, is based on the computerized history of flights and their no-shows, and involves a myriad of factors that include destination, time of day and cost of ticket. The airlines have used inventory management for decades, but its importance in helping carriers to enhance their revenue coincides with new software developed in the last three or four years, analysts and airline executives said. Some of the software has been developed in-house; other systems have come from such companies as the Unisys Corporation and the Control Data Corporation. ''It's probably the No. 1 management tool required to compete properly in this highly competitive airline environment,'' said Lee R. Howard, executive vice president of Airline Economics, a Washington-based consulting firm. Effective inventory management alone can improve an airline's revenues by 5 percent to 20 percent annually, analysts estimated. Mr. Martens said American's system was worth ''hundreds of millions of dollars'' a year to the airline. The airline's total sales exceeded $6 billion last year. ''The revenue implications of yield management are enormous,'' said Julius Maldutis, airline analyst at Salomon Brothers. Inventory management improves a carrier's load factor, or ratio of seats filled. Every 1 percent increase in the load factor translates into $10 million in revenues for the typical major carrier, analysts said. 'Crystal-Ball Gazing' As sophisticated as it is, however, yield management is still subject to variables beyond its control. ''Yield management is about 70 percent technology and 30 percent crystalball gazing,'' said Robert W. Coggin, assistant vice president of marketing development at Delta Air Lines. Bad weather or a last-minute switch to a plane of a different size can wreak havoc with weeks of planning, he said. At American, inventory management begins 330 days before departure. Yield managers use the profiles of a flight's history to parcel out an alphabet soup of fares, rationing fullfare coach seats first, then moving down the price scale. In the following weeks, the computer alerts the managers if sales in a particular fare class pick up unexpectedly. If a travel agent booked a large group of passengers far in advance, for example, the computer would flag the large order and yield managers would restrict or expand the number of seats in that category. Otherwise, managers begin checking all fare mixes regularly 180 days before departure, adding or subtracting seats in each according to demand. The process continues right up to two hours before boarding, according to American's director of yield management, Dennis M. McKaige. Airlines typically put more discount seats on sale just before an advance purchase requirement expires, he said. Therefore, a new batch of cheap tickets that require a 30-day advance purchase might go on sale 31 days before departure. A cut-rate fare offered on Monday might be sold out by Wednesday, then suddenly reoffered hours before takeoff on Thursday if passenger projections based on previous flights fail to materialize, Mr. McKaige said. There are some instances when an airline actually gives preference to discount travelers over customers paying full fare. American has recently developed software to increase the yield on flights through its hubs. American gives preference to a passenger flying on a discount fare from Austin, Tex., to London through Dallas, over another passenger paying full fare from Austin to Shreveport, La., through Dallas. The London passenger, who pays $241 each way, is worth more to the airline than the passenger flying to Shreveport, who pays the full fare of $87 each way. For the bargain hunter, finding a discount will increasingly depend on the season, day and time of travel, destination and length of stay. The New Fare Cuts Continental and Eastern, both units of Texas Air, ignited the latest round of rock-bottom fares in January with ''maxsaver tickets,'' which require a minimum two-day advance purchase and are nonrefundable. ''The spread between our highest and lowest fares is much lower than other airlines,'' said James O'Donnell, vice president of marketing at Continental. ''While our yield management job is no less important than other airlines', it is easier.'' Mr. O'Donnell said the carrier's system was more automated than those used by some of its competitors. The two-day purchase requirement has siphoned off some business travelers who would otherwise have paid full fare. (American and several other airlines last week abandoned plans to raise the lowest discount fares and increase the advance purchase requirement on the cheapest tickets to 30 days, from 2. The airlines backed away from the changes when support for the proposal collapsed.) Airline officials said that nonrefundable tickets were here to stay. Mr. Martens said that since the nonrefundable, maxsaver-type fares were introduced, American's no-show rate had dropped ''substantially below'' the usual range of 12 to 15 percent. Passengers who are willing to commit themselves to a particular flight in exchange for lower prices allow yield managers to refine their operations by concentrating on the remaining coach seats. HOW TWO FLIGHTS COMPARE ON TYPE OF SEATS SOLD Both examples are based on one-way fares for actual American Airlines flights from La Guardia to Dallas/Fort Worth on a DC-10, which has coach capacity of 258 passengers. PEAK FLIGHT Fri., Feb. 13, 5 P.M. Full coach ($230 or more) 89 seats Intermediate discount ($80-$229) 146 seats Deepest discount ($79 or less) 0 seats* Empty 23 seats OFF-PEAK FLIGHT Wed., Feb. 11, 1 P.M. Full coach ($230 or more) 6 seats Intermediate discount ($80-$229) 138 seats Deepest discount ($79 or less) 40 seats Empty 74 seats *Such seats may have been available, with certain restrictions on sales, but none were sold. (Source: American Airlines)