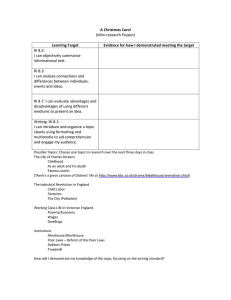

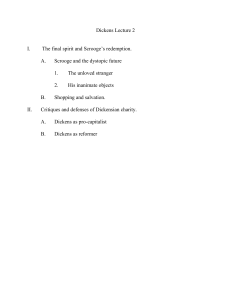

Oliver Twist: Industrial Revolution & Social Change in England

advertisement