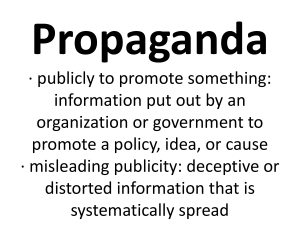

Propaganda and Information Warfare in the Twenty-First Century (1)

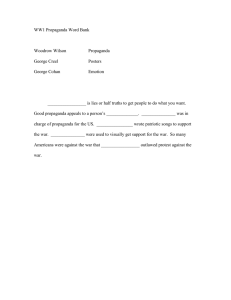

advertisement