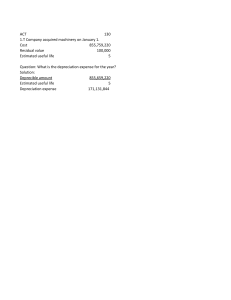

Fundamental Accounting Principles, 17th Canadian Edition Volume 2, 17e Kermit Larson, Heidi Dieckmann, John Harris

advertisement