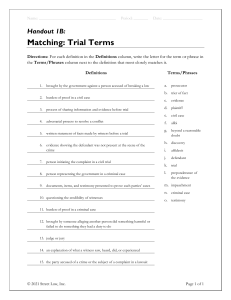

Contents Evidence (law) ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Relevance and social policy .................................................................................................................. 3 Presence or absence of a jury ................................................................................................................ 5 Exclusion of evidence ........................................................................................................................... 5 Unfairness ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Authentication ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Witnesses............................................................................................................................................... 6 Hearsay.................................................................................................................................................. 7 Circumstantial evidence ........................................................................................................................ 7 Evidence that the defendant lied ....................................................................................................... 8 Burdens of proof ................................................................................................................................... 8 Evidentiary rules stemming from other areas of law ............................................................................ 8 Evidence as an area of study ................................................................................................................. 8 References ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Eyewitness identification ........................................................................................................................ 9 Known Cases of Eyewitness Error........................................................................................................ 9 Causes of Eyewitness Error ................................................................................................................ 10 "System Variables" (Police Procedures) ......................................................................................... 10 "Estimator Variables" (Circumstantial Factors) .............................................................................. 15 The Law of Eyewitness Identification Evidence in Criminal Trials ................................................... 17 U.S................................................................................................................................................... 17 England ........................................................................................................................................... 18 Reform Efforts .................................................................................................................................... 20 U.S................................................................................................................................................... 20 Burden of proof ..................................................................................................................................... 21 Types of burden ................................................................................................................................... 21 Standard of proof ................................................................................................................................ 21 Standards for searches, arrests or warrants ..................................................................................... 22 Standards for presenting cases or defenses ..................................................................................... 23 Standards for conviction ................................................................................................................. 23 Non-legal Standards ........................................................................................................................ 27 Criminal law .................................................................................................................................... 27 1 Civil law .......................................................................................................................................... 29 Decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court............................................................................................. 29 Science and other uses ........................................................................................................................ 30 References ........................................................................................................................................... 30 Competence (law) .................................................................................................................................. 31 United States ....................................................................................................................................... 31 Competence to be executed............................................................................................................. 31 Competence and Native Americans ................................................................................................ 32 Competency case law ...................................................................................................................... 32 Hearsay in English law ......................................................................................................................... 32 History of the rule ............................................................................................................................... 33 Reasoning behind the rule ................................................................................................................... 34 Civil proceedings ................................................................................................................................ 34 Criminal proceedings .......................................................................................................................... 35 Statutory definition ......................................................................................................................... 35 General rule ..................................................................................................................................... 36 Statutory exceptions ........................................................................................................................ 36 Preserved common law exceptions ................................................................................................. 37 References ........................................................................................................................................... 39 Dying declaration .................................................................................................................................. 40 In the United States ............................................................................................................................. 40 In entertainment .................................................................................................................................. 41 References ........................................................................................................................................... 41 Declarations against interest ................................................................................................................ 41 2 idered by the trier of fact, such as jury) in a judicial or administrative proceeding (e.g., a court of law). Relevance and social policy Legal scholars of the Anglo-AEvidence (law) 3 The law of evidence governs the use of testimony (e.g., oral or written statements, such as an affidavit) and exhibits (e.g., physical objects) or other documentary material which is admissible (i.e., allowed to be consmerican tradition, but not only that tradition, have long regarded evidence as being of central importance to the law. In every jurisdiction based on the English common law tradition, evidence must conform to a number of rules and restrictions to be admissible. Evidence must be relevant – that is, it must directed at proving or disproving a legal element. However, the relevance of evidence is ordinarily a necessary condition but not a sufficient condition for the admissibility of evidence. For example, relevant evidence may be excluded if it is unfairly prejudicial, confusing, or cumulative. Furthermore, a variety of social policies operate to exclude relevant evidence. Thus, there are limitations on the use of evidence of liability insurance, subsequent remedial measures, settlement offers, and plea negotiations, mainly because it is thought that the use of such evidence discourages parties from carrying insurance, fixing hazardous conditions, offering to settle, and pleading guilty to crimes, respectively. The question of how the relevance or irrelevance of evidence is to be determined has been the subject of a vast amount of discussion in the last 100-200 years. There is now a consensus among legal scholars and judges in the U.S. that the relevance or irrelevance of evidence cannot be determined by syllogistic reasoning – if-then logic – alone. There is also general agreement that assessment of relevance or irrelevance involves or requires judgments about probabilities or uncertainties. Beyond that, there is little agreement. Many legal scholars and judges agree that ordinary reasoning, or common sense reasoning, plays an important role. There is less agreement about whether or not judgments of relevance or irrelevance are defensible only if the reasoning that supports such judgments is made fully explicit. However, most trial judges would reject any such requirement and would say that some judgments can and must rest in part on unarticulated and unarticulable hunches and intuitions. However, there is general (though implicit) agreement that the relevance of at least some types of expert evidence – particularly evidence from the hard sciences – requires particularly rigorous, or in any event more arcane reasoning than is usually needed or expected. There is a general agreement that judgments of relevance are largely within the discretion of the trial court – although relevance rulings that lead to the exclusion of evidence are more likely to be reversed on appeal than are relevance rulings that lead to the admission of evidence. Under the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) Rule 401: "Relevant evidence" means evidence having any 4 tendency to make the existence of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more probable or less probable than it would be without the evidence. Federal Rule 403 allows relevant evidence to be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by danger of unfair prejudice, confusing or misleading the jury or waste of the court's time. California Evidence Code section 352 also allows for exclusion to avoid "substantial danger of undue prejudice." For example, evidence that the victim of a car accident was apparently a "liar, cheater, womanizer, and a man of low morals" was unduly prejudicial and irrelevant to whether he had a valid product liability claim against the manufacturer of the tires on his van (which had rolled over resulting in severe brain damage). Presence or absence of a jury The United States of America has a very complicated system of evidentiary rules; for example, John Wigmore's celebrated treatise on it filled ten volumes. James Bradley Thayer reported in 1898 that even English lawyers were surprised by the complexity of American evidence law, such as its reliance on exceptions to preserve evidentiary objections for appeal. Some legal experts, notably Stanford legal historian Lawrence Friedman, have argued that the complexity of American evidence law arises from two factors: (1) the right of American defendants to have findings of fact made by a jury in practically all criminal cases as well as many civil cases; and (2) the widespread consensus that tight limitations on the admissibility of evidence are necessary to prevent a jury of untrained laypersons from being swayed by irrelevant distractions. In Professor Friedman's words: "A trained judge would not need all these rules; and indeed, the law of evidence in systems that lack a jury is short, sweet, and clear." However, some respected observers disagree with the commonplace thesis that the institution of trial by jury is the main reason for the existence of rules of evidence even in countries such as the United States and Australia; they argue that other variables are at work. Exclusion of evidence Unfairness Under English and Welsh law, evidence that would otherwise be admissible at trial may be excluded at the discretion of the trial judge if it would be unfair to the defendant to admit it. 5 Evidence of a confession may be excluded because it was obtained by oppression or because the confession was made in consequence of anything said or done to the defendant that would be likely to make the confession unreliable. In these circumstances, it would be open to the trial judge to exclude the evidence of the confession under Section 78(1) of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), or under Section 73 PACE, or under common law, although in practice the confession would be excluded under section 76 PACE. Other admissible evidence may be excluded, at the discretion of the trial judge under 78 PACE, or at common law, if the judge can be persuaded that having regard to all the circumstances including how the evidence was obtained “admission of the evidence would have such an adverse effect on the fairness of the proceedings that the court ought not to admit it." Authentication Certain kinds of evidence, such as documentary evidence, are subject to the requirement that the offeror provide the trial judge with a certain amount of evidence (which need not be much and it need not be very strong) suggesting that the offered item of tangible evidence (e.g., a document, a gun) is what the offeror claims it is. The authentication requirement has bite primarily in jury trials. If evidence of authenticity is lacking in a bench trial, the trial judge will simply dismiss the evidence as unpersuasive or irrelevant. Witnesses In systems of proof based on the English common law tradition, almost all evidence must be sponsored by a witness, who has sworn or solemnly affirmed to tell the truth. The bulk of the law of evidence regulates the types of evidence that may be sought from witnesses and the manner in which the interrogation of witnesses is conducted during direct examination and cross-examination of witnesses. Other types of evidentiary rules specify the standards of persuasion (e.g., proof beyond a reasonable doubt) that a trier of fact such as a jury must apply when it assesses evidence. Today all persons are presumed to be qualified to serve as witnesses in trials and other legal proceedings, and all persons are also presumed to have a legal obligation to serve as witnesses if their testimony is sought. However, legal rules sometimes exempt people from the obligation to give evidence and legal rules disqualify people from serving as witnesses under some circumstances. Privilege rules give the holder of the privilege a right to prevent a witness from giving testimony. These 6 privileges are ordinarily (but not always) designed to protect socially valued types of confidential communications. Some of the privileges that are often recognized are the marital secrets privilege, the adverse spousal testimony privilege, the attorney-client privilege, the doctor-patient privilege, the psychotherapist-patient and counselor-patient privilege, the state secrets privilege and the clergypenitent privilege. A variety of additional privileges are recognized in different jurisdictions, but the list of recognized privileges varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction; for example, some jurisdictions recognize a social worker-client privilege and other jurisdictions do not. Witness competence rules are legal rules that specify circumstances under which persons are ineligible to serve as witnesses. For example, neither a judge nor a juror is competent to testify in a trial in which they are serving in that capacity; and in jurisdictions with a dead man statute, a person is deemed not competent to testify as to statements of or transactions with a deceased opposing party. Hearsay Hearsay is one of the largest and most complex areas of the law of evidence in common-law jurisdictions. The default rule is that hearsay evidence is inadmissible. Hearsay is an out of court statement offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. A party is offering a statement to prove the truth of the matter asserted if the party is trying to prove that the assertion made by the declarant (the maker of the pretrial statement) is true. For example, prior to trial Bob says, "Jane went to the store." If the party offering this statement as evidence at trial is trying to prove that Jane actually went to the store, the statement is being offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted. However, at both common law and under evidence codifications such as the Federal Rules of Evidence, there are dozens of exclusions from and exceptions to the hearsay rule. Circumstantial evidence Evidence of an indirect nature which implies the existence of the main fact in question but does not in itself prove it. That is, the existence of the main fact is deduced from the indirect or circumstantial evidence by a process of probable reasoning. The introduction of a defendant's fingerprints or DNA sample are examples of circumstantial evidence. The fact that a defendant had a motive to commit a crime is circumstantial evidence. Some people[who?] believe that all evidence is circumstantial because – some observers[who?] think (and some thoughtful judges[who?] agree) – no evidence ever directly proves a fact. 7 Evidence that the defendant lied Lies, on their own, are not sufficient evidence of a crime. However, lies may indicate that the defendant knows he is guilty, and the prosecution may rely on the fact that the defendant has lied alongside other evidence. Burdens of proof Different types of proceedings require parties to meet different burdens of proof, the typical examples being beyond a reasonable doubt, clear and convincing evidence, and preponderance of the evidence. Many jurisdictions have burden-shifting provisions, which require that if one party produces evidence tending to prove a certain point, the burden shifts to the other party to produce superior evidence tending to disprove it. One special category of information in this area includes things of which the court may take judicial notice. This category covers matters that are so well known that the court may deem them proven without the introduction of any evidence. For example, if a defendant is alleged to have illegally transported goods across a state line by driving them from Boston to Los Angeles, the court may take judicial notice of the fact that it is impossible to drive from Boston to Los Angeles without crossing a number of state lines. In a civil case, where the court takes judicial notice of the fact, that fact is deemed conclusively proven. In a criminal case, however, the defense may always submit evidence to rebut a point for which judicial notice has been taken. Evidentiary rules stemming from other areas of law Some rules that affect the admissibility of evidence are nonetheless considered to belong to other areas of law. These include the exclusionary rule of criminal procedure, which prohibits the admission in a criminal trial of evidence gained by unconstitutional means, and the parol evidence rule of contract law, which prohibits the admission of extrinsic evidence of the contents of a written contract. Evidence as an area of study In countries that follow the civil law system, evidence is normally studied as a branch of procedural law. Nevertheless, because of its importance to the practice of law, all American law schools offer a course in evidence, and most require the subject either as a first year class, or as an upper-level class, or as a 8 prerequisite to later courses. Furthermore, evidence is heavily tested on the Multistate Bar Examination ("MBE") - of the 200 multiple choice questions asked in that test, approximately one sixth will be in the area of evidence. The MBE predominantly tests evidence under the Federal Rules of Evidence, giving little attention to matters for which state law is likely to be inconsistent. References 1. ^ Winfred D. v. Michelin North America, Inc., 165 Cal. App. 4th 1011 (2008) (reversing jury verdict for defendant). 2. ^ Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 3rd ed. (New York: Touchstone, 2005), 300. 3. ^ Friedman, 300. 4. ^ Friedman, 301. 5. ^ Lawrence M. Friedman, American Law in the Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 266. Eyewitness identification Eyewitness identification evidence is the leading cause of wrongful conviction in the United States. Of the more than 200 people exonerated by way of DNA evidence in the US, over 75% were wrongfully convicted on the basis of erroneous eyewitness identification evidence. In England, the Criminal Law Review Committee, writing in 1971, stated that cases of mistaken identification "constitute by far the greatest cause of actual or possible wrong convictions". Yet despite substantial anecdotal and scientific support for the proposition that eyewitness testimony is often unreliable, it is held in high regard by jurors in criminal trials, even when "far outweighed by evidence of innocence." In the words of former US Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, there is "nothing more convincing [to a jury] than a live human being who takes the stand, points a finger at the defendant, and says 'That's the one!'" Known Cases of Eyewitness Error The Innocence Project has facilitated the exoneration of 214 men who were convicted of crimes they did not commit, as a result of faulty eyewitness evidence. A number of these cases have received substantial attention from the media. 9 Jennifer Thompson's case is one example: She was a college student in North Carolina in 1984, when a man broke into her apartment, put a knife to her throat, and raped her. According to her own account, Ms. Thompson studied her rapist throughout the incident with great determination to memorize his face. "I studied every single detail on the rapist's face. I looked at his hairline; I looked for scars, for tattoos, for anything that would help me identify him. When and if I survived the attack, I was going to make sure that he was put in prison and he was going to rot." Exonerations Ms. Thompson went to the police station later that same day to work up a [composite sketch] of her attacker, relying on what she believed was her detailed memory. Several days later, the police constructed a photographic lineup, and she selected Ronald Junior Cotton from the lineup. She later testified against him at trial. She was positive it was him, without any doubt in her mind. "I was sure. I knew it. I had picked the right guy, and he was going to go to jail. If there was the possibility of a death sentence, I wanted him to die. I wanted to flip the switch." But she was wrong, as DNA results eventually showed. It turns out she was even presented with her actual attacker during a second trial proceeding a year after the attack, but swore she'd never seen the man before in her life. She remained convinced that Ronald Cotton was her attacker, and it was not until much later, after Mr. Cotton had served 11 years in prison for a crime he did not commit, that she realized that she had made a grave mistake. Jennifer Thompson's memory had failed her, resulting in a substantial injustice. It took definitive DNA testing to shake her confidence, but she now knows that despite her confidence in her identification, it was wrong. Cases like Ms. Thompson's, including a long history of eyewitness errors traceable back to Biblical times, prompted the emergence of a field within the social sciences dedicated to the study of eyewitness memory and the causes underlying its frequently recurring failures. Causes of Eyewitness Error "System Variables" (Police Procedures) One of the primary reasons that eyewitnesses to crimes have been shown to make mistakes in their recollection of perpetrator identities, is the police procedures used to collect eyewitness evidence. Various factors have been discovered to make police identification procedures more or less reliable as a 10 test of eyewitness memory, and these procedural mechanisms have been termed "system variables" by social scientists researching this systemic problem. "System variables are those that affect the accuracy of eyewitness identifications and over which the criminal justice system has (or can have) control." Acknowledging the importance of these procedural precautions recommended by leading eyewitness researchers, the Department of Justice published a set of best practices for conducting police lineups in 1999. Culprit-Present versus Culprit-Absent Lineups One of the most obvious causes of inaccurate identifications resulting from police lineups is the use of a lineup that does not include the actual perpetrator of the crime. In other words, police suspect one person of having committed a crime, when in fact it was committed by an unknown other person who does not appear in the lineup. When the actual perpetrator is not included in the lineup, research has shown that the police suspect faces a significantly heightened risk of being incorrectly identified as the culprit. According to eyewitness researchers, the most likely cause of this increased occurrence of misidentification is what is termed the "relative judgment" process. That is, when viewing a group of photos or individuals, a witness tends to select the person who looks "most like" the perpetrator. When the actual perpetrator is not present in the lineup, the police suspect is often the person who best fits the description, hence his or her selection for the lineup. Given the common, good faith occurrence of police lineups that do not include the actual perpetrator of a crime, it becomes particularly critical that other procedural measures are undertaken to minimize the likelihood of an inaccurate identification. Pre-Lineup Instructions Following this finding that eyewitnesses are prone to making "relative judgments" when faced with a lineup that does not contain the actual perpetrator, researchers hypothesized that instructing the witness prior to the lineup might serve to mitigate the occurrence of error. In fact, studies have shown that simply instructing a witness that the perpetrator "may or may not be present" in the lineup can dramatically reduce the likelihood that a witness will identify an innocent person. 11 "Blind" Lineup Administration Eyewitness researchers know that the police lineup is, at center, a psychological experiment designed to test the ability of a witness to recall the identity of the perpetrator of a crime. As such, it is recommended that police lineups be conducted in double-blind fashion, like any scientific experiment, in order to avert the possibility that inadvertent cues from the lineup administrator will suggest the "correct" answer and thereby subvert the independent memory of the witness. The occurrence of "experimenter bias" is well-documented across the sciences, and as such, researchers recommend that police lineups be conducted by someone not connected to the case and unaware of the identity of the suspect. Lineup Structure and Content "Known Innocent" Fillers Once police have identified a suspect, they will typically place that individual into either a live or photo lineup, along with a set of "fillers." Researchers and the DOJ guidelines recommend, as a preliminary matter, that the fillers be "known innocent" non-suspects. This way, if a witness selects someone other than the suspect, the unreliability of that witness's memory is revealed. In that respect, the lineup procedure serves as a test of the witness's memory, with clear "wrong" answers. If more than one suspect is included in the lineup – as in the 2006 Duke University lacrosse case, for example – then the lineup becomes tantamount to a multiple choice test with no wrong answer. Filler Characteristics These "known innocent" fillers should be selected to match the original description provided by the witness. If a neutral observer is able to select the suspect from the lineup based on the recorded description by the witness – that is, if the suspect is the only one present who clearly fits the description – then the procedure cannot be relied upon as a test of the witness's memory of the actual perpetrator. Researchers have noted that this rule is particularly important when the witness's description includes unique features, such as tattoos, scars, unusual hairstyles, etc. Simultaneous vs. Sequential Presentation Researchers have also suggested that the manner in which photos or individuals chosen for a lineup are presented can also be key to the reliability of an identification. Specifically, leading researchers suggest 12 that lineups should be conducted sequentially, rather than simultaneously. In other words, each member of a given lineup should be presented to a witness by himself, rather than showing a group of photos or individuals to a witness together. According to social scientists, use of this procedure will minimize the effects of the "relative judgment" process discussed above, by encouraging witnesses to compare each person individually to his or her independent memory of the identity of the perpetrator. According to researchers, use of a simultaneous procedure makes it more likely that witnesses will pick the person who merely looks the most like the perpetrator from the group, which introduces an acute danger when the actual perpetrator is not present in the lineup.[15] A pilot study was conducted in Minnesota in 2006 to test this hypothesis, and the results show the sequential procedure to be superior as a means of improving identification accuracy and reducing the occurrence of false identifications. The "Illinois Report" Controversy In 2005, the Illinois state legislature commissioned a pilot project to test reform measures recommended by social scientists to increase the accuracy and reliability of police identification procedures. The study was conducted by the Chicago police department, and an initial report purported to show that the status quo was superior to procedures recommended by researchers in reducing false identifications, in reliance on their decades of scientific research. The mainstream media spotlighted the report, including a front-page article in the New York Times, suggesting that three decades' worth of otherwise uncontroverted social science had been called into question. Criticism of the report and its underlying methodology surfaced shortly after its release. One critic averred that "the design of the [Illinois pilot] project contained so many fundamental flaws that it is fair to wonder whether its sole purpose was to inject confusion into the debate about the efficacy of sequential double-blind procedures and to thereby prevent adoption of the reforms.” Seeking information on the data and methodology underlying the report, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (NACDL) filed a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act seeking the unreleased information. That suit remains pending. In July 2007, a "blue ribbon" panel of eminent psychologists, including one Nobel Laureate, released a report examining the methodology and claims of the Illinois Report, which appears to have confirmed the suspicions of earlier critics. Researchers from Harvard, Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, and other academic institutions examined the study and reported that the study was infected with a fundamental flaw that had "devastating consequences" to its scientific merit, and which "guaranteed that most outcomes would be difficult or impossible to interpret." Their primary critique was an observed 13 "confounding" of variables, rendering it impossible to draw meaningful comparisons between the methods tested. The confound that the critics of the Illinois study criticized was the following: the Illinois study compared the traditional simultaneous method of lineup presentation with the sequential double-blind method recommended by academics like Gary Wells. The traditional method is not conducted doubleblind (meaning that the person presenting the lineup does not know which person or photo is the suspect). The critics claim that the results cannot be compared because one method was not doubleblind while the other was double-blind. This criticism ignores the fact that the mandate of the Illinois legislature was to compare the traditional method with the academic method. More significantly, as an experiment to determine whether or not sequential double-blind administration would be superior to the simultaneous methods used by most police departments, the Illinois study provides an abundance of useful data which, at this point, seems to show that neither of the methods used in that experiment is superior to the other. What it does not provide is a clear reason why, because the effect of "doubleblind" was not tested for the simultaneous lineups. Three large police departments are now working with the Innocence Project on real world studies to compare simultaneous double-blind photo lineups (called photo arrays) with sequential double-blind photo lineups. These studies are likely to shed further light on the controversy concerning Simultaneous vs. Sequential presentation, and the role that double-blind administration plays in each. Post-Lineup Feedback and Confidence Statements Any feedback from the lineup administrator following an identification can have a dramatic effect on a witness's sense of his or her own accuracy. A highly tentative "maybe" can be artificially transformed into "100% confident" with a simple comment such as "Good, you identified the actual suspect." Mere preparation for cross-examination, including simply thinking about how to answer questions regarding the identification, has also been shown to artificially inflate an eyewitness's sense of her own level of certainty; the same is true when a witness simply learns that another witness identified the same person. This malleability of eyewitness confidence has been shown to be far more pronounced in cases where the witness turns out to be wrong. When there is a positive correlation between eyewitness confidence and accuracy, it tends to occur when a witness's confidence is measured immediately following the identification, and prior to any confirming feedback. In keeping with this finding, researchers suggest that a statement of a witness's confidence, in her own words, be taken immediately following an identification. Any future statement 14 of confidence or certainty is widely regarded as unreliable, given the host of intervening factors that have been shown to distort it as time passes. "Estimator Variables" (Circumstantial Factors) Social scientists have also identified a set of "estimator variables" – that is, factors connected to the witness herself or to the circumstances surrounding her observation of the individual she would later attempt to identify – that research has shown to make an identification more or less reliable. Cross-Racial Identifications One of the most-studied topics in this area is the cross-racial identification, namely when the witness and the perpetrator are of different races. A recent meta-analysis of 25 years of research shows a definitive, statistically significant "cross-race impairment," where members of any one race have a clear deficiency for accurately identifying members of another race. The effect appears to be true regardless of the races in question. Various hypotheses have been tested to explain this deficiency in identification accuracy, including any racial animosity on the part of the viewer, and exposure level to the other race in question. Racist attitudes have not been observed to have any effect on the impairment; exposure level has been observed to have a minute effect in some studies, yet the crossrace impairment itself has been observed to substantially overshadow all other variables, even when testing people who have been surrounded by members of the other race for their entire lives. Stress The effect of stress on eyewitness recall is one of the most widely misunderstood of the factors commonly at play in a crime witness scenario. Studies have consistently shown that the presence of stress has a dramatically negative impact on the accuracy of eyewitness memory, a phenomenon which is often not appreciated by witnesses themselves. In a seminal study on this topic, Yale psychiatrist Charles Morgan and a team of researchers tested the ability of trained, military survival school students to identify their interrogators following low- and high-stress scenarios. In each condition, subjects were face-to-face with an interrogator for 40 minutes in a well-lit room. The following day, each participant was asked to select his or her interrogator out of either a live or photo lineup. In the case of the photo spread – the most common form of police lineup in the U.S. – those subjected to the high-stress scenario falsely identified someone other than the interrogator in 68% of cases, compared to only 12% from the low-stress scenario. 15 Presence of a Weapon Weapon Focus The presence of a weapon has also been shown to diminish the accuracy of eyewitness recall, often referred to as the "weapon-focus effect". This phenomenon has been studied at length by eyewitness researchers, and the findings have consistently demonstrated that eyewitnesses recall the identity of a perpetrator less accurately when a weapon was present during the incident. Eminent psychologist Elizabeth Loftus used eye-tracking technology to monitor this effect, and found that the presence of a weapon draws a witness's visual focus away from other things, such as the perpetrator's face. Rapid Decline of Eyewitness Memory Eyewitness Memory It is thought that memory degrades over time, some researchers state that the rate at which eyewitness memory declines is swift, and the drop-off is sharp, in contrast to the more common view that memory degrades slowly and consistently as time passes. The "forgetting curve" of eyewitness memory has been shown to be "Ebbinghausian" in nature: it begins to drop off sharply within 20 minutes following the initial encoding, and continues to do so exponentially until it begins to level off around the second day at a dramatically reduced level of accuracy. And as noted above, eyewitness memory is increasingly susceptible to contamination as time passes. Other Circumstantial Factors A variety of other factors have been observed to affect the reliability of an eyewitness identification. The elderly and young children tend to recall faces less accurately, as compared to young adults. Intelligence, education, gender, and race, on the other hand, appear to have no effect (with the exception of the cross-race effect, as above).[33] The opportunity that a witness has to view the perpetrator and the level of attention paid have also been shown to affect the reliability of an identification. Attention paid, however, appears to play a more substantial role than other factors like lighting, distance, or duration. For example, when witnesses observe the theft of an item known to be of high value, studies have shown that their higher degree of attention can result in a higher level of identification accuracy (assuming the absence of contravening 16 factors, such as the presence of a weapon, stress, etc.). The Law of Eyewitness Identification Evidence in Criminal Trials U.S. The legal standards addressing the treatment of eyewitness testimony as evidence in criminal trials vary widely across the United States on issues ranging from the admissibility of eyewitness testimony as evidence, the admissibility and scope of expert testimony on the factors affecting its reliability, and the propriety of jury instructions on the same factors. Admissibility The federal due process standard governing the admissibility of eyewitness evidence is set forth in the U.S. Supreme Court case of Manson v. Brathwaite. Under the federal standard, if an identification procedure is shown to be unnecessarily suggestive, the court must consider whether certain independent indicia of reliability are present, and if so, weigh those factors against the corrupting effect of the flawed police procedure. Within that framework, the court should determine whether, under the totality of the circumstances, the identification appears to be reliable. If not, the identification evidence must be excluded from evidence under controlling federal precedent. Certain criticisms have been waged against the Manson standard, however. According to legal scholars, "the rule of decision set out in Manson has failed to meet the Court's objective of furthering fairness and reliability." For example, the Court requires that the confidence of the witness be considered as an indicator of the reliability of the identification evidence. As noted above, however, extensive studies in the social sciences have shown that confidence is unreliable as a predictor of accuracy. Social scientists and legal scholars have also expressed concern that "the [Manson] list as a whole is substantially incomplete," thereby opening the courthouse doors to the admission of unreliable evidence. Expert Testimony Expert testimony on the factors affecting the reliability of eyewitness evidence is allowed in some U.S. jurisdictions, and not in others. In most states, it is left to the discretion of the trial court judge. States generally allowing it include California, Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Tennessee (by a 2007 state Supreme Court decision), Ohio, and Kentucky. States generally prohibiting it include Pennsylvania and Missouri. Many states have less clear guidelines under appellate court precedent, such as Mississippi, 17 New York, New Hampshire, and New Jersey. It is often difficult to tell whether expert testimony has been allowed in a given state, since if the trial court lets the expert testify, there is generally no record created. On the other hand, if the expert is not allowed, that becomes a ground of appeal if the defendant is convicted. That means that most cases that generate appellate records are cases only in which the expert was disallowed (and the defendant was convicted). In those states where expert testimony on eyewitness reliability is not allowed, it is typically on grounds that the various factors are within the common sense of the average juror, and thus not the proper topic of expert testimony. Polling data and other surveys of juror knowledge appear to contradict this proposition, however, revealing substantial misconceptions on a number of discrete topics that have been the subject of significant study by social scientists. Jury instructions Criminal defense lawyers often propose detailed jury instructions as a mechanism to offset undue reliance on eyewitness testimony, when factors shown to undermine its reliability are present in a given case. Many state courts prohibit instructions detailing specific eyewitness reliability factors but will allow a generic instruction, while others find detailed instructions on specific factors to be critical to a fair trial. California allows instructions when police procedures are in conflict with established best practices, for example, and New Jersey mandates an instruction on the cross-race effect when the identification is central to the case and uncorroborated by other evidence. England PACE Code D Most identification procedures are regulated by Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 Code D. Where there is a particular suspect In any cases where identification may be an issue, a record must be made of the description of the suspect first given by a witness. This should be disclosed to the suspect or his solicitor. If the ability of a suspect to make a positive visual identification is likely to be an issue, one of the formal identification procedures in Pace Code D, para 3.5-3.10 should be used, unless it would serve no useful purpose (e.g. because the suspect was known to the witnesses or if there was no reasonable possibility that a witness could make an identification at all). 18 The formal identification procedures are: 1. Video identification 2. Identification parade If it is more practicable and suitable than video identification, an identification parade may be used. 3. Group identification If it is more suitable than video identification or an identification parade, the witness may be asked to pick a person out after observing a group. 4. Confrontation If the other methods are unsuitable, the witness may be asked whether a certain person is the person they saw. Where there is no particular suspect If there is no particular suspect, a witness may be shown photographs or be taken to a neighbourhood in the hope that he recognizes the perpetrator. Photographs should be shown to potential witnesses individually (to prevent collusion) and once a positive identification has been made, no other witnesses should be shown the photograph of the suspect. Breaches of Pace Code D Under s. 78 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, the trial judge may exclude evidence if it would have an adverse effect on the fairness of the proceedings if it were admitted. Breach of Code D does not automatically mean that the evidence will be excluded, but the judge should consider whether a breach has occurred and what the effect of the breach was on the defendant. If a judge decides to admit evidence where there has been a breach, he should give reasons.[40] and in a jury trial, the jury should normally be told "that an identification procedure enables suspects to put the reliability of an eye-witness’s identification to the test, that the suspect has lost the benefit of that safeguard, and that they should take account of that fact in their assessment of the whole case, giving it such weight as they think fit" Turnbull directions Where the identification of the defendant is in issue (not merely the honesty of the identifier or the fact that the defendant matched a particular description), and the prosecution rely substantially or wholly on the correctness of one or more identifications of the defendant, the judge should give a direction to the jury: 1. The judge should warn the jury of the special need for caution before convicting the accused in 19 reliance on the correctness of the identification or identifications. In addition he should instruct them as to the reason for the need for such a warning and should make some reference to the possibility that a mistaken witness can be a convincing one and that a number of such witnesses can all be mistaken. 2. The judge should direct the jury to examine closely the circumstances in which the identification by each witness came to be made and remind the jury of any specific weaknesses in the identification evidence. If the witnesses recognized a known defendant, the judge should remind the jury that mistakes even in the recognition of relatives or close friends are sometimes made. 3. When, in the judgment of the trial judge, the quality of the identifying evidence is poor, as for example when it depends solely on a fleeting glance or on a longer observation made in difficult conditions, the judge should withdraw the case from the jury and direct an acquittal unless there is other evidence which goes to support the correctness of the identification. 4. The trial judge should identify to the jury the evidence which he adjudges is capable of supporting the evidence of identification. If there is any evidence or circumstances which the jury might think was supporting when it did not have this quality, the judge should say so. Reform Efforts U.S. Largely in response to the mounting list of wrongful convictions discovered to have resulted from faulty eyewitness evidence, an effort is gaining momentum in the United States to reform police procedures and the various legal rules addressing the treatment of eyewitness evidence in criminal trials. Social scientists are committing more resources to studying and understanding the mechanisms of human memory in the eyewitness context, and lawyers, scholars, and legislators are devoting increasing attention to the fact that faulty eyewitness evidence remains the leading cause of wrongful conviction in the United States. Reform measures mandating that police use established best practices when collecting eyewitness evidence have been implemented in New Jersey, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Minnesota. Bills on the same topic have been proposed in Georgia, New Mexico, California, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Vermont, and others. 20 Burden of proof The burden of proof (Latin: onus probandi) is the obligation to shift the assumed conclusion away from an oppositional opinion to one's own position. The burden of proof may only be fulfilled by evidence. Under the Latin maxim necessitas probandi incumbit ei qui agit, the general rule is that "the necessity of proof lies with he who complains." The burden of proof, therefore, usually lies with the party making the new claim. The exception to this rule is when a prima facie case has been made. He who does not carry the burden of proof carries the benefit of assumption, meaning he needs no evidence to support his claim. Fulfilling the burden of proof effectively captures the benefit of assumption, passing the burden of proof off to another party. The burden of proof is an especially important issue in law and science. Types of burden There are generally two broad types of burdens: A "legal burden" or a "burden of persuasion" is an obligation that remains on a single party for the duration of the claim. Once the burden has been entirely discharged to the satisfaction of the trier of fact, the party carrying the burden will succeed in its claim. For example, the presumption of innocence places a legal burden upon the prosecution to prove all elements of the offence (generally beyond a reasonable doubt) and to disprove all the defences except for affirmative defenses in which the proof of nonexistence of all affirmative defence(s) is not constitutionally required of the prosecution.[1] An "evidentiary burden" or "burden of leading evidence" is an obligation that shifts between parties over the course of the hearing or trial. A party may submit evidence that the court will consider prima facie evidence of some state of affairs. This creates an evidentiary burden upon the opposing party to present evidence to refute the presumption. Standard of proof The "standard of proof" is the level of proof required in a legal action to discharge the burden of proof, that is to convince the court that a given proposition is true. The degree of proof required depends on the circumstances of the proposition. Typically, most countries have two levels of proof or the balance 21 of probabilities: preponderance of evidence - (lowest level of proof, used mainly in civil trials) beyond a reasonable doubt - (highest level of proof, used mainly in criminal trials) In addition to these, the U.S. introduced a third standard called clear and convincing evidence, which is the medium level of proof, used, for example, in cases in which the state seeks to terminate parental rights. The first attempt to quantify reasonable doubt was made by Simon[clarification needed] in 1970. In the attempt, she presented a trial to groups of students. Half of the students decided the guilt or innocence of the defendant. The other half recorded their perceived likelihood, given as a percentage, that the defendant committed the crime. She then matched the highest likelihoods of guilt with the guilty verdicts and the lowest likelihoods of guilt with the innocent verdicts. From this, she gauged that the cutoff for reasonable doubt fell somewhere between the highest likelihood of guilt matched to an innocent verdict and the lowest likelihood of guilt matched to a guilty verdict. From these samples, Simon concluded that the standard was between 0.70 and 0.74. Standards for searches, arrests or warrants Reasonable suspicion Reasonable suspicion is a low standard of proof in the U.S. to determine whether a brief investigative stop or search by a police officer or any government agent is warranted. It is important to note that this stop and/or search must be brief; its thoroughness is proportional to, and limited by, the low standard of evidence. A more definite standard of proof (often probable cause) would be required to warrant a more thorough stop/search. In Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968), the United States Supreme Court ruled that reasonable suspicion requires specific, articulable, and individualized suspicion that crime is afoot. A mere guess or "hunch" is not enough to constitute reasonable suspicion. Probable cause for arrest Probable cause is a relatively low standard of evidence, which is used in the United States to determine whether a search, or an arrest, is warranted. It is also used by grand juries to determine whether to issue an indictment. In the civil context, this standard is often used where plaintiffs are seeking a prejudgment remedy. 22 In the criminal context, the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Sokolow, 490 U.S. 1 (1989), determined that probable cause requires "a fair probability that contraband or evidence of a crime will be found" in determining whether Drug Enforcement Administration agents had a reason to execute a search. Courts vary when determining what constitutes a "fair probability," some say 30%, others 40%, others 51%. A good illustration of this evidence/intrusiveness continuum might be a typical police/citizen interaction. Consider the following three interactions: →no level of suspicion required: a consensual encounter between officer and citizen →reasonable suspicion required: a stop initiated by the officer that would cause a reasonable person to feel that he or she is not free to leave →probable cause required: arrest. Standards for presenting cases or defenses Air of reality The "air of reality" is a standard of proof used to determine whether a criminal defense may be used. The test asks whether a defense can be successful if it is assumed that all the claimed facts are to be true. In most cases, the burden of proof rests solely on the prosecution, negating the need for a defense of this kind. However, when exceptions arise and the burden of proof has been shifted to the defendent, he is required to establish a defense that bears an "air of reality." Two instances in which such a case might arise are, first, when a prima facie case has been made against the defendent or, second, when the defense mounts an affirmative defense, such as the insanity defense. Standards for conviction Balance of probabilities Balance of probabilities, also known as the preponderance of the evidence, is the standard required in most civil cases. The standard is met if the proposition is more likely to be true than not true. Effectively, the standard is satisfied if there is greater than 50 percent chance that the proposition is true. Lord Denning, in Miller v. Minister of Pensions, described it simply as "more probable than not." 23 Clear and convincing evidence Clear and convincing evidence is the higher level of burden of persuasion sometimes employed in the U.S. civil procedure. To prove something by "clear and convincing evidence", the party with the burden of proof must convince the trier of fact that it is substantially more likely than not that the thing is in fact true. This is a lesser requirement than "proof beyond a reasonable doubt", which requires that the trier of fact be close to certain of the truth of the matter asserted, but a stricter requirement than proof by "preponderance of the evidence," which merely requires that the matter asserted seem more likely true than not. Beyond reasonable doubt This is the standard required by the prosecution in most criminal cases within an adversarial system and is the highest level of burden of persuasion. This means that the proposition being presented by the government must be proven to the extent that there is no "reasonable doubt" in the mind of a reasonable person that the defendant is guilty. There can still be a doubt, but only to the extent that it would not affect a "reasonable person's" belief that the defendant is guilty. If the doubt that is raised does affect a "reasonable person's" belief that the defendant is guilty, the jury is not satisfied beyond a "reasonable doubt". The precise meaning of words such as "reasonable" and "doubt" are usually defined within jurisprudence of the applicable country. What is the burden of proof? First, we must address the meaning of the word “burden.” Most often jurors interpret this word as meaning weight. Jurors picture the state in the person of the prosecutor with a massive object on his back attempting to carry it up some incline for some distance– defense attorneys have been heard to say that the state has a “heavy burden.” The word “burden” has nothing to do with weight, mass or any other physical properties – the word simply means responsibility. It is the state’s responsibility to prove the defendant’s guilt. It has nothing to do with the degree or intensity of proof. Who has to prove the defendant’s guilt? The State does. To what degree must guilt be proven? Beyond a reasonable doubt. What does that mean? Again the problem is with words being used in an abnormal or special way. The word “beyond” normally means farther than or more than. Clearly this is not the meaning of the word in the phrase “beyond a reasonable doubt.” The state does not have to “carry its burden” beyond some point that constitutes reasonable doubt. The state certainly is not trying to prove that there is more than a reasonable doubt. If anything the state’s responsibility is to prove that there is less than a reasonable doubt. The word “beyond” in the phrase beyond a reasonable doubt means “to the exclusion of.” That is the state must exclude any and all reasonable doubt as to the 24 defendant’s guilt. Simply put, the phrase means that if a juror has a reasonable doubt it is her duty to return a verdict of not guilty. On the other hand, if a juror does not have a reasonable doubt then the state has met its burden of proof and it is the juror’s duty to return a verdict of guilty. “What is a reasonable doubt?” Jury instructions typically say that a reasonable doubt is a doubt based on reason and common sense and typically use phrases such as “fully satisfied” or “entirely convinced” in an effort to quantify the standard of proof. These efforts tend to create more problems than they solve. For example, take the phrases “fully satisfied” and “entirely convinced.” A person is satisfied when she is content, pleased, happy, comfortable or at ease. The fellow leans back in his chair after a meal, pats his stomach and says, “that was one satisfying meal.” Is that what the state must do - offer sufficient proof that a juror is content, happy, pleased or comfortable with her verdict. Absolutely not. A juror is not required to be pleased with the verdict or happy with the verdict. The state is not required to produce sufficient evidence to eliminate all reasonable doubt AND to please the juror or to eliminate all reservations about whether the juror has done the right thing. “Satisfied” in the phrase “fully satisfied” simply means convinced. Likewise the modifiers "entirely" and "fully" do not mean that you have to be 100 percent certain of the defendant’s guilt. The standard of proof is not absolute certainty. A juror is "fully satisfied" or "entirely convinced" when the state had eliminated all reasonable doubt. Jury instructions often state that a reasonable doubt can arise from the "lack or insufficiency of the evidence." This phrase is rich with possibilities for concocting doubt – Where are the fingerprints? Where is the DNA evidence? Where are the other officers who assisted with the arrest? These arguments invite, actually require that the jury engage in speculation – something a jury is specifically instructed not to do. An example, a person enters a store. The clerk who is talking to her friend on the telephone sees the man. She tells her friend that the man appeared to be casing the place and asks her friend to call the police. A few minutes later the man leaves the store, walks to his car, opens the trunk, and retrieves a ski-mask and a shotgun. The man dons the mask, re-enters the store and tells the clerk to give it up. The clerk does as she is told and put the contents of the till into a bag which she hands to the man. The man then leaves the store. As he is running to his car the police arrive. The man flees from the scene with the police officers in hot pursuit. As he runs the man tosses the bag, gun and mask. He is caught shortly thereafter, returned to the store and is positively identified by the clerk as the man who cased the store and then robbed her. The bag is retrieved and the money in the bag exactly matches to the penny the amount taken from the register. At the trial, the defense attorney asks the lead investigator whether hair samples were taken from the mask and submitted to the lab for analysis. The investigator says no. During closing arguments the defense attorney conveniently ignores all the 25 evidence of guilt and pounds away at the sloppy investigation and argues that had the hair analysis could have provided the jury with "irrefutable evidence" of the defendant's guilt or innocence. Is the absence of the hair evidence what the phrase “lack of insufficiency of the evidence” refers to. No. The phrase refers to the convincing force of the evidence presented. The presence or absence of reasonable doubt is to be determined by the evidence presented at trial not what might have been presented. There is a standard objection- Calls for speculation – that is exactly what the defense attorney is asking the jury to do, to speculate. Not simple speculation but a series of "what ifs." What if a hair sample had been found, what if the hair sample had been sent to the lab for DNA analysis, what if he DNA profile had not “matched” the defendant’s. What if + what if + what if = reasonable doubt. Remember that the state’s duty is to eliminate any reasonable doubt, any logical explanation that arises from the evidence. The defense's argument is not a proper argument. It is a “tool of logical inversion” All the evidence would compel one to say the defendant is guilty. However, the defendant wants the jurors to think, "but still there is that missing hair analysis evidence. I wonder what that would have shown?" A jury properly draw conclusion based on the evidence and inferences drawn from the evidence. The strength of the conclusions is based on the persuasive force of the evidence. With one exception, "Lack or insufficiency" refers to the convincing force of the evidence presented. The exception is the missing witness rule. The missing witness rule, is: "The failure to call a witness raises a presumption of inference that the testimony of such person would be unfavorable to the party failing to call him, but there is no such presumption or inference where the witness is not available, or where his testimony is unimportant or cumulative, or where he is equally available to both sides." "The reasonable-doubt standard plays a vital role in the American scheme of criminal procedure. It is a prime instrument for reducing the risk of convictions resting on factual error. The standard provides concrete substance for the presumption of innocence – that bedrock "axiomatic and elementary" principle whose "enforcement lies at the foundation of the administration of our criminal law." Proof beyond a reasonable doubt did not become the accepted standard in criminal cases until the middle of the nineteenth century. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt was not the standard by which guilt was determined when the Bill of Rights was drafted in 1789. This may explain the absence of the phrase in the constitution. Nor was it an element of due process. Attempts to quantify the burden of proof are exercises in futility. It is more a qualitative than 26 quantitative concept. As Rembar notes, "Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is a quantum without a number." Non-legal Standards Beyond the shadow of a doubt Beyond the shadow of a doubt is the most strict standard of proof. It requires that there be no doubt as to the issue. Widely considered an impossible standard, a situation stemming from the nature of knowledge itself, it is valuable to mention only as a comment on the fact that evidence in a court never need reach this level. This phrase, has, nonetheless, come to be associated with the law in popular culture. Criminal law In the West, criminal cases usually place the burden of proof on the prosecutor (expressed in the Latin brocard ei incumbit probatio qui dicit, non que negat, "the burden of proof rests on who asserts, not on who denies"). This principle is known as the presumption of innocence, and is summed up with "innocent until proven guilty," but is not upheld in all legal systems or jurisdictions. Where it is upheld, the accused will be found not guilty if this burden of proof is not sufficiently shown by the prosecution. For example, if the defendant (D) is charged with murder, the prosecutor (P) bears the burden of proof to show the jury that D did murder someone. Burden of proof: P Burden of production: P has to show some evidence that D had committed murder. The United States Supreme Court has ruled that the Constitution requires enough evidence to justify a rational trier of fact to find guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. If the judge rules that such burden has been met, then of course it is up to the jury itself to decide if they are, in fact, convinced of guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.[18] If the judge finds there is not enough evidence under the standard, the case must be dismissed (or a subsequent guilty verdict must be vacated and the charges dismissed). e.g. witness, forensic evidence, autopsy report Failure to meet the burden: the issue will be decided as a matter of law (the judge makes the decision), in this case, D is presumed innocent Burden of persuasion: if at the close of evidence, the jury cannot decide if P has 27 established with relevant level of certainty that D had committed murder, the jury must find D not guilty of the crime of murder Measure of proof: P has to prove every element of the offence beyond a reasonable doubt, but not necessarily prove every single fact beyond a reasonable doubt. In other countries, criminal law reverses the burden of proof, and there is a presumption of guilt. However, in England and Wales, the Magistrates' Courts Act 1980, s.101 stipulates that where a defendant relies on some "exception, exemption, proviso, excuse or qualification" in his defence, the legal burden of proof as to that exception falls on the defendant, though only on the balance of probabilities. For example, a person charged with being drunk in charge of a motor vehicle can raise the defence that there was no likelihood of his driving while drunk.[19] The prosecution have the legal burden of proof beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant exceeded the legal limit of alcohol and was in control of a motor vehicle. Possession of the keys is usually sufficient to prove control, even if the defendant is not in the vehicle and is perhaps in a nearby bar. That being proved, the defendant has the legal burden of proof on the balance of probabilities that he was not likely to drive.[20] Similar rules exist in trial on indictment. Some defences impose an evidential burden on the defendant which, if met, imposes a legal burden on the prosecution. For example, if a person charged with murder pleads the right of self-defense, the defendant must satisfy the evidential burden that there are some facts suggesting self-defence. The legal burden will then fall on the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant was not acting in self-defence.[20] In 2002, such practice in England and Wales was challenged as contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), art.6(2) guaranteeing right to a fair trial. The House of Lords held that such burdens were not contrary to the ECHR:[20][21] A mere evidential burden did not contravene art.6(2); A legal/ persuasive burden did not necessarily contravene art.6(2) so long as confined within reasonable limits, considering the questions: What must the prosecution prove to transfer burden to the defendant? Is the defendant required to prove something difficult or easily within his access? What is threat to society that the provision is designed to combat? 28 Civil law In civil law cases, the "burden of proof" requires the plaintiff to convince the trier of fact (whether judge or jury) of the plaintiff's entitlement to the relief sought. This means that the plaintiff must prove each element of the claim, or cause of action, in order to recover. The burden of proof must be distinguished from the "burden of going forward," which simply refers to the sequence of proof, as between the plaintiff and defendant. The two concepts are often confused. Decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court In Keyes v. Sch. Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973), the United States Supreme Court stated: “There are no hard-and-fast standards governing the allocation of the burden of proof in every situation. The issue, rather, ‘is merely a question of policy and fairness based on experience in the different situations.’” For support, the Court cited 9 John H. Wigmore, Evidence § 2486, at 275 (3d ed. 1940). In Keyes, the Supreme Court held that if “school authorities have been found to have practiced purposeful segregation in part of a school system,” the burden of persuasion shifts to the school to prove that it did not engaged in such discrimination in other segregated schools in the same system. In Director, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs v. Greenwich Collieries, 512 U.S. 267 (1994), the Supreme Court explained that burden of proof is ambiguous because it has historically referred to two distinct burdens: the burden of persuasion, and the burden of production. The Supreme Court discussed how courts should allocate the burden of proof (i.e., the burden of persuasion) in Schaffer ex rel. Schaffer v. Weast, 546 U.S. 49 (2005). The Supreme Court explained that if a statute is silent about the burden of persuasion, the court will “begin with the ordinary default rule that plaintiffs bear the risk of failing to prove their claims.” In support of this proposition, the Court cited 2 J. Strong, McCormick on Evidence § 337, 412 (5th ed. 1999), which states: The burdens of pleading and proof with regard to most facts have been and should be assigned to the plaintiff who generally seeks to change the present state of affairs and who therefore naturally should be expected to bear the risk of failure of proof or persuasion. At the same time, the Supreme Court also recognized “The ordinary default rule, of course, admits of exceptions.” “For example, the burden of persuasion as to certain elements of a plaintiff's claim may be shifted to defendants, when such elements can fairly be characterized as affirmative defenses or exemptions. See, e.g., FTC v. Morton Salt Co., 334 U.S. 37, 44-45 (1948). Under some circumstances 29 this Court has even placed the burden of persuasion over an entire claim on the defendant. See Alaska Dept. of Environmental Conservation v. EPA, 540 U.S. 461 (2004).” Nonetheless, “[a]bsent some reason to believe that Congress intended otherwise, therefore, [the Supreme Court] will conclude that the burden of persuasion lies where it usually falls, upon the party seeking relief.” Science and other uses Outside a legal context, "burden of proof" means that someone suggesting a new theory or stating a claim must provide evidence to support it: it is not sufficient to say "you can't disprove this." Specifically, when anyone is making a bold claim, either positive or negative, it is not someone else's responsibility to disprove the claim, but is rather the responsibility of the person who is making the bold claim to prove it. In short, X is not proven simply because "not X" cannot be proven (see negative proof). Taken more generally, the standard of proof demanded to establish any particular conclusion varies with the subject under discussion. Just as there is a difference between the standard required for a criminal conviction and in a civil case, so there are different standards of proof applied in many other areas of life. The less reasonable a statement seems, the more proof it requires. The scientific consensus on cold fusion is a good example. The majority believes this can not really work, because believing that it would do so would force the alteration of a great many other tested and generally accepted theories about nuclear physics. References 1. ^ Patterson v. New York, 432 U.S. 197 (1977) 2. ^ "Distributions of Interest for Quantifying Reasonable Doubt and Their Applications" (PDF). http://www.valpo.edu/mcs/pdf/ReasonableDoubtFinal.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-01-14. 3. ^ Miller v. Minister of Pensions [1947] 2 All ER 372 4. ^ See Bugliosi, Till Death Us Do Part (Norton 1979) 5. ^ See, Jackson v Virginia, 443 US 307, 61 L Ed 2d 560, 99 S Ct 2781(1979) See, e.g. N.C.P.I.-Crim. 101.10 BURDEN OF PROOF AND REASONABLE DOUBT. 6. ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/satisfied 7. ^ Jamie Whyte, Crimes Against Logic, page 45 8. ^ Briscoe v. State, 40 Md. App. 120, 388 A.2d 153 (1978). 30 9. ^ In re Winship, 397 U.S. 358 (1970)citing Coffin v. United States,156 U.S. 432, 453 (1895) Competence (law) In American law, competence concerns the mental capacity of an individual to participate in legal proceedings. Defendants that do not possess sufficient "competence" are usually excluded from criminal prosecution, while witnesses found not to possess requisite competence cannot testify. The English equivalent is fitness to plead. United States In United States law, this protection has been ruled by the United States Supreme Court to be guaranteed under the due process clause. If the court determines that a defendant's mental condition makes him unable to understand the proceedings, or that he is unable to help in his defense, he is found incompetent. The competency evaluation, as determined in Dusky v. United States, is whether the accused "has sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding—and whether he has a rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him." Being determined incompetent is substantially different from undertaking an insanity defense; competence regards the defendant's state of mind at the time of the trial, while insanity regards his state of mind at the time of the crime. It has also been referred to as a "7:30 exam". The word incompetent is also used to describe persons who lack mental capacity to make contracts, handle their financial and other personal matters such as consenting to medical treatment, etc. and need a legal guardian to handle their affairs. In 2006, the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit considered the legal standards for determining competence to stand trial and to waive counsel using the standards of objective unreasonableness under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act.[1] Competence to be executed An inmate on death row has a right to be evaluated for competency by a psychologist to determine if sentence can be carried out. This is a result of Ford v. Wainwright, a case filed by a Florida inmate on death row who took his case to the United States Supreme Court, declaring he was not competent to be executed. The court ruled in his favor, stating that a forensic professional must make that competency evaluation and, if the inmate is found incompetent, must provide treatment to aid in his gaining 31 competency so the execution can take place.[2] Competence and Native Americans Competency was used to determine whether individual Indians could use land that was allotted to them from the General Allotment Act (GAA) also known as the Dawes Act. The practice was used after in 1906 with the passing of the Burk Act, also known as the forced patenting act. This Act further amended the GAA to give the Secretary of the Interior the power to issue allotees a patent in fee simple to people classified ‘competent and capable.’ The criteria for this determination is unclear but meant that allotees deemed ‘competent’ by the Secretary of the Interior would have their land taken out of trust status, subject to taxation, and could be sold by the allottee. The Act of June 25 1910 further amends the GAA to give the Secretary of the Interior the power to sell the land of deceased allotees or issue patent and fee to legal heirs. This decision is based on a determination made by the Secretary of Interior whether the legal heirs are ‘competent’ or ‘incompetent’ to manage their own affairs. Competency case law Adjudicative competence has been developed through a body of common law in the United States. The landmark cases are the following:[3] Dusky v. United States (1960) Jackson v. Indiana (1972) Drope v. Missouri (1975) Ford v. Wainwright (1986) Godinez v. Moran (1993) Pate v. Robinson Estelle v. Smith (1981) Medina v. California (1992) Riggins v. Nevada (1992) Cooper v. Oklahoma (1996) Sell v. United States (2003) Hearsay in English law The hearsay provisions of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 reformed the common law relating to the 32 admissibility of hearsay evidence in criminal proceedings begun on or after 4 April 2005. Section 114 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 defines hearsay evidence as a statement not made in oral evidence in criminal proceedings and admissible as evidence of any matter stated but only if certain conditions are met, specifically where, (a) it is in the interests of justice for it to be admissible (see section 114(1)(d)), (b) the witness is unavailable to attend (see section 116), (c) the evidence is contained in a business, or other, document (see section 117) or (d) the evidence is multiple hearsay (see section 121). The meaning of “statements” and “matter stated” is explained in section 115 of the 2003 Act. “Oral evidence” is defined in section 134(1) of that Act. History of the rule The rules of hearsay began to form properly in the late seventeenth century and had become fully established by the early nineteenth century. The issues were analysed in substantial detail in Wright v Doe d Tatham[1]. The technical nature of the discussion in Doe d Tatham inhibited much reasoned progress of the law, whose progress (in the form of judicial capacity to reform it) ended not long afterwards.[2] Later attempts to reform through the common law it got little further, with Lord Reid in Myers v DPP[3] saying "If we are to extend the law it must be by the development and application of fundamental principles. We cannot introduce arbitrary conditions or limitations; that must be left to legislation: and if we do in effect change the law, we ought in my opinion only to do that in cases where our decision will produce some finality or certainty. If we disregard technicalities in this case and seek to apply principle and common sense, there are a number of parts of the existing law of hearsay susceptible of similar treatment, ... The only satisfactory solution is by legislation following on a wide survey of the whole field ... A policy of make do and mend is not appropriate." There was some statutory reform in the nineteenth century (see Bankers' Books Evidence Act), and later the Evidence Act 1938 made some further if cautious reforms. The state of the hearsay rules were regarded as 'absurd' by Lord Reid[3] and Lord Diplock.[4] 33 The Law Commission[5] and Supreme Court committee[6] provided a number of reports on hearsay reform, prior to the Civil Evidence Acts 1968 and 1972. The Criminal Justice Act 2003 ("2003 Act"), which went into force on 4 April 2005, introduced significant reforms to the hearsay rule, implementing (with modifications) the report by the Law Commission in Evidence in Criminal Proceedings: Hearsay and Related Topics (LC245), published on 19 June 1997. Previously, the Criminal Justice Act 1988 had carved out exceptions to the hearsay rule for unavailable witnesses and business documents. These were consolidated into the 2003 Act. See: WikiCrimeLine Hearsay evidence Reasoning behind the rule The reasoning process behind the hearsay rule can be seen by comparing the acceptance of direct evidence and hearsay. In adducing direct evidence (that is, recollection of a witness in court) the court will consider how he would have perceived the event at the time, potential ambiguities and the witness's sincerity. These can be tested in cross-examination. A hearsay statement may duplicate each of these uncertainties (firstly for the absent original witness, secondly for the one in court), and crossexamination of the original witness is impossible. Although the rule is directed only at references to statements asserted for the truth of their contents, the courts were alive to the dangers of circumstantial as well as direct evidence:[7] "the hearsay rule operates in two ways: (a) it forbids using the credit of an absent declarant as the basis of an inference, and (b) it forbids using in the same way the mere evidentiary fact of the statement as having been made under such and such circumstances." The nature of the genuine danger of allowing a jury to make an inappropriate inference about the nature of such evidence has sometime led to misunderstandings about the nature of hearsay.[8] A different rationale can be found in the requirement of justice that the accused is entitled to face his or her opponents. This principle finds support in the European Convention on Human Rights (articles 6(1) and 6(3)(d)) and, in the United States the sixth amendment of its Constitution (its principles tracing back to Raleigh's Trial[9]). Civil proceedings Hearsay is generally admissible in civil proceedings.[10] This is one area in which English law differs 34 dramatically from American law; under the Federal Rules of Evidence, used in U.S. federal courts and followed practically verbatim in almost all states, hearsay is inadmissible in both criminal and civil trials barring a recognized exception. The law concerning hearsay in civil proceedings was reformed substantially by the Civil Evidence Act 1995[11] ("the 1995 Act") and is now primarily upon a statutory footing. The Act arose from a report of the Law Commission published in 1993 which criticized the previous reforming statutes' excessive caution and cumbersome procedures. Section 1 of the Act says "In civil proceedings evidence shall not be excluded on the ground that it is hearsay" This includes hearsay of multiple degree (that is, hearsay evidence of hearsay evidence: for example "Jack told me that Jill told him that she went up the hill"). Other provisions of the 1995 Act preserve common law rules relating to public documents, published works of a public nature and public records.[13] The common law in respect of good and bad character, reputation or family tradition is also preserved.[14] The Act moves some of the focus of hearsay evidence to weight, rather than admissibility, setting out considerations in assessing the evidence (set out in summary form):[15] reasonableness of the party calling the evidence to have produced the original maker whether the original statement was made at or near the same time as the evidence it mentions whether the evidence involves multiple hearsay whether any person involved had any motive to conceal or misrepresent matters whether the original statement was an edited account, or was made in collaboration with another, or for a particular purpose whether the circumstances of the hearsay evidence suggest an attempt to prevent proper evaluation of its weight Criminal proceedings Statutory definition The Criminal Justice Act 2003 defines hearsay as statements "not made in oral evidence in the proceedings" being used "as evidence of any matter stated".[16] 35 General rule Statutory exceptions Unavailable witnesses Evidence of a witness may be read in court if he or she is unavailable to attend court.[17] In order to be admissible, the evidence referred to would have to have been otherwise admissible, and maker of the statement identified to the court's satisfaction. Additionally, the absent person making the original statement must fall within one of five categories: he or she is dead he or she is unfit to be a witness because of his bodily or mental condition he or she is outside the United Kingdom and it is not reasonably practicable to secure his or her attendance he or she cannot be found although such steps as it is reasonably practicable to take to find him or her have been taken that through fear he or she does not give (or does not continue to give) oral evidence in the proceedings, either at all or in connection with the subject matter of the statement In the case of absence through fear, some additional safeguards are impose prior to the statement's admission. The court must be satisfied it is in the interests of justice, particularly considering the statements contents, whether special measures (screens in court, or video live-link) would assist, and any unfairness to the defendant in not being able to challenge the evidence. A party to the proceedings (that is, either the prosecution or defence) who causes any of the above five conditions to occur in order to stop a witness giving evidence cannot then adduce the hearsay evidence of it. The scope of this rule has undergone consideration in cases when much of the prosecution case involves evidence by a witness who is absent from court. In Luca v Italy[18] it was held that a conviction solely or decisively based upon evidence of witnesses which the accused has had no opportunity to examine breached Article 6 of the Convention (right to a fair trial). However in R v Arnold[19] it was said this rule would permit of some exceptions, otherwise it would provide a licence to intimidate witnesses - though neither should it be treated as a licence for prosecutors to prevent testing of their case. Each application had to be weighed carefully. 36 Business documents Documents created in the course of a trade, occupation, profession or public office (referred to as "business") can be used as evidence of the facts stated therein.[20] To be admissible, the evidence referred to in the document must itself be admissible. The person supplying the information must have had personal knowledge of it (or be reasonably supposed to have had), and everyone else through whom the information was supplied must have also been acting in the course of business. If the business information was produced in the course of a domestic criminal investigation, then either one of the above five categories (for absent witnesses) must apply, or the person producing the statement cannot be expected now to have any recollection of the original information. A typical example of this is doctor's notes in relation to an injured person, which is then adduced as medical evidence in a criminal trial. Previous criminal records can be adduced (if otherwise admissible) under this section, but not normally any further details about the method of commission, unless it can be demonstrated that the data inputter had the appropriate personal knowledge.[21] Previous consistent and inconsistent statements Sometimes during the testimony of a witness, the witness may be questioned about statements he previously made outside court on an earlier occasion, to demonstrate either that he has been consistent or inconsistent in his account of events. The Act did not change the circumstances in which such statements could become admissible in evidence (which are still prescribed in the Criminal Procedure Act 1865), but it did change the evidential effect of such statements once admitted. Formerly, such statements were not evidence of the facts stated in them (unless the witness agreed with them in court): they only proved that the witness had kept his story straight or had changed his story, and so were only evidence of his credibility (or lack of it) as a witness. They were not hearsay. Under the 2003 Act, however, such statements are now themselves evidence of any facts stated in them, not just of credibility, and so are now hearsay. Preserved common law exceptions Section 118 of the 2003 Act preserved the following common law rules and abolished the remainder: Public information as evidence of the facts stated therein: published works dealing with matters of a public nature (such as histories, scientific 37 works, dictionaries and maps) public documents (such as public registers, and returns made under public authority with respect to matters of public interest) records (such as the records of certain courts, treaties, Crown grants, pardons and commissions) evidence relating to a person's age or date or place of birth may be given by a person without personal knowledge of the matter Reputation as to character - evidence of a person's reputation is admissible for the purpose of proving his good or bad character Reputation or family tradition - evidence of reputation or family tradition is admissible to prove or disprove (and only so far as it does so): pedigree or the existence of a marriage (or civil partnership following the Civil Partnership Act 2004) the existence of any public or general right the identity of any person or thing Res gestae - statements are admissible if: the statement was made by a person so emotionally overpowered by an event that the possibility of concoction or distortion can be disregarded, the statement accompanied an act which can be properly evaluated as evidence only if considered in conjunction with the statement, or the statement relates to a physical sensation or a mental state (such as intention or emotion). Confessions - all rules relating to the admissibility of confessions or mixed statements Admissions by agents etc as evidence of facts stated: an admission made by an agent of a defendant is admissible against the defendant as evidence of any matter stated, or a statement made by a person to whom a defendant refers a person for information is admissible against the defendant as evidence of any matter stated. Common enterprise - a statement made by a party to a common enterprise is admissible against another party to the enterprise Expert evidence 38 Agreement Hearsay evidence is permitted by agreement between all parties in the proceedings.[22] No such provision existed before the coming into force of the 2003 Act. Interests of justice There are some older cases which threw the rigidities of the hearsay rule into sharp relief. In Sparks v R[23] a U.S. airman was accused of indecently assaulting a girl just under the age of four. Evidence that the four year old victim (who did not give evidence herself) had told her mother "it was a coloured boy" was held not to be admissible (not being res gestae either) against the defendant, who was white. In R v Blastland[24] the House of Lords held in a murder case that highly self-incriminating remarks made by a third party, not at the trial, could not admitted in evidence (the remarks mentioning the murder of a boy whose body had not yet been independently discovered). Under the 2003 Act, any hearsay evidence whether or not covered by another provision may be admitted by the court if it is "in the interests of justice" to do so.[25] This provision is sometimes known as the "safety valve". The Act sets out criteria in determining whether the interests of justice test are met though other considerations can be taken into account: how much probative value (that is, use in determining the case) the statement has (assuming it to be true), or its value in understanding other evidence what other relevant evidence has or can be given its importance in the context of the case as a whole the circumstances in which the statement was made how reliable the maker of the statement appears to be how reliable the evidence of the making of the statement appears to be whether oral evidence of the matter stated can be given and, if not, why not the difficulty involved in challenging the statement the extent to which that difficulty would be likely to prejudice the party facing it References 1. ^ (1837) 7 Ad & El 313 2. ^ Sugden v Lord St Leonards (1876) 1 PD 154; see also Sturla v Freccia, below 39 3. ^ a b [1965] AC 1001 at 1021 4. ^ Jones v Metcalfe [1967] 1 WLR 1286 at 1291 5. ^ 13th Report of the Law Reform Committee Cmnd 2964 (1966), para 11 6. ^ Report of the Committee on Supreme Court practice and procedure, Cmnd 8878 (1953) 7. ^ Thayer, Legal Essays, 1907 8. ^ R v Olisa [1990] Crim LR 721 Dying declaration In the law of evidence, the dying declaration is testimony that would normally be barred as hearsay but may nonetheless be admitted as evidence in certain kinds of cases because it constituted the last words of a dying person. Case law has ruled out this hearsay exception in many criminal law trials, because the criminal defendant has the right to confront witnesses against them.[1] Case law will dicate how this rule is used in the future. In the United States Under the Federal Rules of Evidence, a dying declaration is admissible if the proponent of the statement can establish: (1) Unavailability of the declarant -- this can be established using FRE 804(a)(1)-(5); (2) The declarant’s statement is being offered in a criminal prosecution for murder, or in a civil action; (3) The declarant’s statement was made while under the belief that his death was imminent; and (4) The declarant’s statement must relate to the cause or circumstances of what he believed to be his impending death. For example, suppose Alice stabs Bob and then runs away, and a police officer happens upon Bob as he lies in the gutter, bleeding to death. If Bob manages to sputter out with his last words, "I'm dying Alice stabbed me" (or even just "Alice did it"), the officer can testify to that in court. The declarant does not actually have to die for the statement to be admissible, but they need to have had a genuine belief that they were going to die, and they must be unavailable to testify in court. In the above scenario, if Bob were to recover instead of dying, and were able to testify in court, the officer would no longer be able to testify to the statement. It would then constitute hearsay, and not fall into 40 the exception. Furthermore, the statement must relate to the circumstances or the cause of the declarant's own death. If Bob's last words are "Alice killed Carol", that statement will not fall within the exception, and will be inadmissible (unless Alice killed Bob and Carol in the same act). Furthermore, as with all testimony, the dying declaration will be inadmissible unless it is based on the declarant's actual knowledge. Suppose, for example, Bob bought a cup of coffee at the airport, and was stricken with food poisoning. If his dying last words were that "the people who sold them the coffee mix must have used a defective packing machine", that statement would be inadmissible despite the hearsay exception because Bob had no way of knowing anything about the conditions in which the coffee was packed. In U.S. federal courts, the dying declaration exception is limited to civil cases and criminal homicide prosecutions. Although many U.S. States copy the Federal Rules of Evidence in their statutes, some permit the admission of dying declarations in all cases. The first use of the dying declaration exception in American law was in the 1770 murder trial of the British soldiers responsible for the Boston Massacre. One of the victims, Patrick Carr, told his doctor before he died that the soldiers had been provoked. The doctor's testimony helped defense attorney John Adams to secure acquittals for some of the defendants and reduced charges for the rest. If the defendant is convicted of homicide, but the reliability of the 'dying declaration' is in question, there is grounds for an appeal.[2] In entertainment In the movie The Fugitive, Harrison Ford's character's wife calls out his name, leading to his false conviction. References 1. ^ Court: Dead victim's prior statements can't be used at trial - CNN.com 2. ^ Dying declaration unreliable: SC acquits two « My Nation Foundation - News Declarations against interest Declarations against interest are an exception to the rule on hearsay in which a person's statement may be used, where generally the content of the statement is so prejudicial to the person making it that they would not have made the statement unless they believed the statement was true. The Federal Rules 41 of evidence limit the bases of prejudices to the declarant to tort and criminal liability. Some states, such as California, extend the prejudice to "hatred, ridicule, or social disgrace in the community." A declaration against interest differs from a party admission because here the declarant does not have to be a party to the case, but must have a basis for knowing that the statement is true. Furthermore, evidence of the statement will only be admissible if the declarant is unavailable to testify. For example, California's Evidence Code Section 1230 defines "Declarations against interest" as “ Evidence of a statement by a declarant having sufficient knowledge of the subject is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule if the declarant is unavailable as a witness and the statement, when made, was so far contrary to the declarant's pecuniary or proprietary interest, or so far subjected him to the risk of civil or criminal liability, or so far tended to render invalid a claim by him against another, or created such a risk of making him an object of hatred, ridicule, or social disgrace in the community, that a reasonable man in his position would not have made the statement unless he believed it to be true. 42