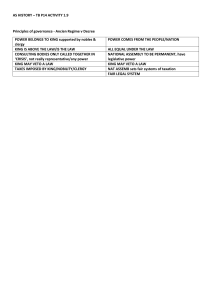

WISCONSIN INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, GHANA (FACULTY OF LAW) LEVEL/SEMESTER: 300 UPPER / 2ND SEMESTER OF 2022/2023 ACADEMIC YEAR COURSE: PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW II (GROUP 5) NAME INDEX NO 1. WASILA MUKTAR WAKASO 11022359 2. GEORGE ASAMOAH AMPONSAH 1101327 3. CHRISLORD J. NSIAH 1101362 4. CHARLOTTE ASARE 1101299 5. WUOBAR JOAN OF ARC NAA 1101084 6. LORETTA AGYEI 1101368 7. GERTRUDE BOAKYE DARKWAH 1101359 8. ABDUL-GANIWU MOHAMMED 1101397 9. AKAMBISA AKADIDIPO PRISCILA 1101311 10. DOUGLAS APPIAH KWADWO SARKODIE (PhD) 1101324 11. GRACE NANA ESI ADAMS 1101395 12. NAOMI KYEKYE 1101318 13. JOSEPH ASUMADU 1101390 14. AMOAH ERIC 1101157 15. Ralph Osew Danquah 16. Kofi Diaba 17. Emmanuel Owusu. 1101389 1101366 100987 Question 5: The use of the veto in the Security Council effectively prevents the use of force to resolve any international problems where one party is either a veto power or enjoys close relations with such a state.’ Discuss with particular reference to one or more contemporary international disputes. INTRODUCTION Sixty years after the birth of the United Nations, UN reform is high on the inter-national political agenda. One of the most controversial issues, if not the single most sensitive one, concerns the structure and practice of the Security Council as the primary actor regarding international peace and security. Indeed, criticism of the Council’s lack of representativeness and transparency has not diminished in recent years, despite a shift towards more openness. On the contrary, as the Council has become ever more active, criticism has increased correspondingly. One of the traditional stumbling blocks has been the existence of the veto power of the Council’s permanent members, which enables any one of the so-called P-5 (France, the United Kingdom, the United States, China and Russia) to block any resolution that is not merely procedural. The veto is considered fundamentally unjust by a majority of States and is thought to be the main reason why the Council failed to respond adequately to humanitarian crises such as in Rwanda (1994) and Darfur (2004). It is thus not surprising that most States wish to abolish or restrain the veto. Equally unsurprising is the fact that the P-5, whose concurring votes and ratifications are required for even the smallest amendment of the UN Charter (under articles 108 and 109) reject any limitation of the veto outright. For this reason, many States have abandoned radical reform proposals and have adopted a pragmatic approach, pleading in particular for voluntary restraint on the veto use. The focus of this paper is to look at the extent to which the use of veto in the Security Council prevents the use of force to resolve international problems particularly where one party is either a veto power or enjoys close relations with such a state. COMPOSITION OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL The Security Council has five permanent members—the United States, China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom—collectively known as the P5. Any one of them can veto a resolution. The Security Council has ten elected members, which serve two -year, nonconsecutive terms, and are not afforded veto power. The P5’s privileged status has its roots in the United Nations’ founding in the aftermath of World War II. The United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) were the outright victors of the war, and, along with the United Kingdom, they shaped the postwar political order. As their plans for what would become the United Nations took shape, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt insisted on the inclusion of the Republic of China (Taiwan), envisioning international security presided over by “four global policemen.” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill saw in France a European buffer against potential German or Soviet aggression and so sponsored its bid for restored great-power status. THE POWER OF VETO The "Power of veto" is not explicitly mentioned in the UN Charter, however, Article 27 requires concurring votes from the permanent members of the United Nations. Owing to this, the "power of veto" is also referred to as the principle of "great power unanimity" and the veto itself is occasionally referred to as the "great power veto. Article 27 of the United Nations Charter, states: 1. Each member of the Security Council shall have a vote. 2. Decisions of the Security Council on procedural matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members. 3. Decisions of the Security Council on all other matters shall be made by an affirmative vote of nine members including the concurring votes of the permanent members; provided that, in decisions under Chapter VI, and under paragraph 3 of Article 52, a party to a dispute shall abstain from voting. The provisions in Chapter VI and Article 52 contain Security Council recommendations which are not binding resolutions under Chapter VII, this, therefore, ensures that the permanent members (P-5) have veto power over all UN sanctions and all United Nations peacekeeping operations. The power of veto arises in Article 37 (3) by the mention of the concurring votes of the permanent members. This means that the nonconcurrent vote of one of the permanent members will impede the adoption of a draft resolution. However, a permanent member that abstains or is absent from the vote will not block a resolution from being passed. A permanent member may abstain rather than vote “nay,” which preserves the resolution. Such a move affords a nation the opportunity to make its moral or political objections clear, while at the same time allowing the resolution to pass; four “yeas” and an abstention will be enough, for example, as long as five nonpermanent Security Council members also are on board. For instance, the Korean War was authorized with the “OK” of only four permanent members; at the time, Communist China’s seat was occupied by the exiled government of Chiang Kai-Shek, and the U.S.S.R. was boycotting the United Nations. THE USE OF FORCE IN INTERNATIONAL LAW The use of force is regulated by the United Nations Charter which prohibits the use of force under Article 2(4) by one state against another, except in certain limited circumstances. The Charter recognizes the inherent right of states to self-defense in the event of an armed attack, but also requires that such use of force is reported to the Security Council and that it be necessary and proportionate to the threat. The use of force in international law is also governed by the principles of jus ad bellum and jus in bello. Jus ad bellum refers to the legal conditions that must be met before a state may use force, such as a just cause, right intention, last resort, proportionality, and reasonable prospects of success. Jus in bello, on the other hand, refers to the legal rules that apply during the conduct of armed conflict, including the principles of distinction, proportionality, and humane treatment of prisoners of war and civilians. Although Article 2(4) of the UN Charter encapsulates broad legal prohibition of the use of force by nations on others, there are two exceptions to the Article 2(4) ban on the threat or use of force which include actions authorized by the UN Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, and actions that constitute a legitimate act of individual or collective selfdefense according to Article 51 of the UN Charter and/or customary international law (CIL). The justification for the use of force by the UN Security Council is succinctly captured in Articles 39, 40, and 41 of the UN Charter as stated below. Article 39 “ the security council shall determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace or act of aggression and shall make a recommendation, or decide what measures should be taken in accordance with articles 41 and 42, to maintain or restore international peace and security”. Article 40 “In order to prevent an aggravation of the situation, the Security Council may, before making the recommendations or deciding upon the measures provided for in Article 39, call upon the parties concerned to comply with such provisional measures as it deems necessary or desirable. Such provisional measures shall be without prejudice to the rights, claims, or position of the parties concerned. The Security Council shall duly take account of failure to comply with such provisional measures”. Article 41 reads: “the Security Council may decide what measures not involving the use of armed force are to be employed to give effect to its decisions, and it may call upon the Members of the United Nations to apply such measures. These may include complete or partial interruption of economic relations and of rail, sea, air, postal, telegraphic, radio, and other means of communication, and the severance of diplomatic relations”. Article 42 reads; “Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations”. The combined effect of Articles 39, 40, 41, and 42 illustrates that when the Security Council decides on the existence of a threat to the peace or a breach of the peace or an act of aggression, the UN Charter is accorded three approaches to the Security Council i.e. to make recommendations according to Article 39; however, prior before that, call upon the parties concerned to comply with such provisional measures as it deems necessary or desirable to prevent an aggravation of the situation, formulate non-military measures (diplomatic and economic sanctions); or formulate military enforcement measures (action by air, land, or sea forces). After haven established the justifications for the use of force by the UN Security Council and providing a vivid meaning of “veto power”, its root, and who is entitled to its usage, attempt will now be made to examine the use of veto by the P5. THE EXERCISE OF VETO BY THE P5 The members of the P5 have exercised the veto power to varying degrees. Counting the years when the Soviet Union held its seat, Russia has been the most frequent user of the veto, blocking 152 resolutions since the Security Council’s founding, as of February 2023. The United States has used the veto eighty-seven times; it last vetoed a resolution in 2020 that called for the prosecution, rehabilitation, and reintegration of those engaged in terrorism-related activities. The country objected to the resolution’s not calling for the repatriation of fighters from the self-proclaimed Islamic State and their family members. China has used the veto more frequently in recent years, though it has historically been more sparing than the United States or Russia; Beijing has now blocked nineteen resolutions, including sixteen since 1997. In contrast, France and the United Kingdom have not exercised their veto power since 1989 and have advocated for other P5 members to use it less. One contemporary international dispute where the veto power has been a significant obstacle to resolving the conflict is the ongoing civil war in Syria. The Security Council has been unable to reach a consensus on how to address the conflict due to Russia and China having vetoed several resolutions calling for the use of force against Syria, which has been in a civil war since 2011. Both countries have argued that military intervention would be counterproductive and that the conflict should be resolved through diplomatic means. Both Russia and China are close allies of the Syrian government. The conflict in Syria began in 2011 when pro-democracy protests against the government of President Bashar al-Assad turned violent, leading to a full-scale civil war. The conflict has resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people and the displacement of millions of Syrians. The Security Council has taken several actions in response to the conflict, including the adoption of resolutions aimed at facilitating humanitarian aid and ceasefires. However, these resolutions have not had a significant impact on the ground due to the veto power of Russia and China. Russia, in particular, has used its veto power on multiple occasions to block resolutions critical of the Syrian government or calls for more significant action to be taken to end the conflict. For example, in 2017, Russia vetoed a resolution that would have imposed sanctions on Syria over its use of chemical weapons. Similarly, in 2018, Russia vetoed a resolution calling for an investigation into the alleged use of chemical weapons in the town of Douma. The use of the veto power by Russia and China in the Security Council has effectively prevented the international community from taking decisive action to address the conflict in Syria. This has resulted in continued suffering and loss of life for the Syrian people. In the case of the resolution condemning Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia exercised its veto power as a permanent member of the UNSC. This prevented the resolution from being passed, although the annexation of Crimea was widely viewed as a violation of international law and a threat to regional stability. The veto was seen as an attempt by Russia to protect its interests in the region, rather than to protect the rights and security of the people affected by the annexation. This is not the only example of a permanent member using its veto power in a way that prioritizes its interests over the protection of civilians. For example, China has used its veto power to block resolutions on human rights abuses in North Korea, while the United States has used its veto power to shield Israel from criticism over its treatment of Palestinians. Mention can also be made of the following instances; Israel-Palestine conflict: The United States has used its veto power to block several resolutions critical of Israel's actions in the occupied territories, including calls for the use of force to protect Palestinian civilians. Kosovo: In 1999, NATO launched a military campaign against Yugoslavia to stop the ethnic cleansing of Albanians in Kosovo. Russia, one of the permanent members, vetoed a UNSC resolution condemning the campaign, arguing that it violated Yugoslavia's sovereignty. CONCLUSION Amnesty International asserted that the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) used their veto power to promote their political or geopolitical interests above the protection of civilians. The UNSC is tasked with maintaining international peace and security, and one of its primary tools for achieving this goal is the use of resolutions. However, the UNSC can only pass a resolution if there are no objections from any of its five permanent members, which are the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom. The veto power granted to the permanent members of the Security Council has been a significant obstacle to resolving the conflict in Syria. As discussed above, the use of the veto power by Russia and China other permanent members of the UN Security Council has effectively prevented the international community from taking decisive action to end the conflict and alleviate the suffering of the Syrian people. REFERENCES: Bardo Fassbender, UN Security Council Reform and the Right of Veto: A Constitutional Perspective, Kluwer Law International, The Hague / London / Boston, 1998 Council on Foreign Relations by Will Freeman and Ariana Rios. David Malone (ed), The UN Security Council: From the Cold War to the 21st Century, Lynne Rienner, Boulder, Colorado, 2004. Luck, Edward C. (2008). "Creation of the Council". In Lowe, Vaughan; Roberts, Adam; Welsh, Jennifer; et al. (eds.). The United Nations Security Council and War: The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945. Pei, Minxin (7 February 2012). "Why Beijing Votes With Moscow". The New York Times. 4 November 2021.