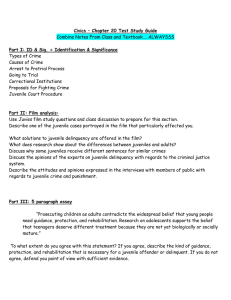

Kristin Ann Bates - Juvenile Delinquency in a Diverse Society-Sage Publications, Inc (2013) (1)

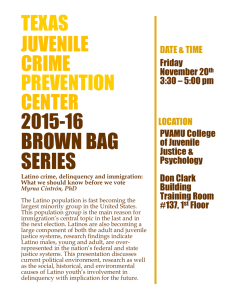

advertisement