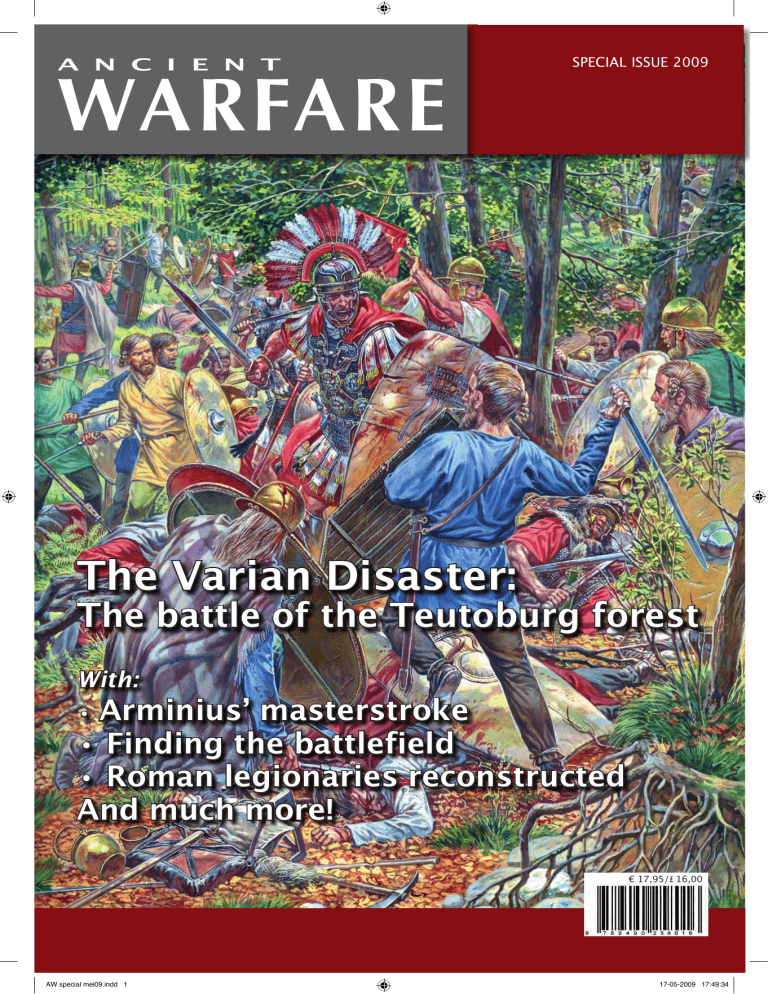

A N C I E N T WARFARE SPECIAL ISSUE 2009 The Varian Disaster: The battle of the Teutoburg forest With: • Arminius’ masterstroke • Finding the battlefield • Roman legionaries reconstructed And much more! € 17,95/£ 16,00 AW special mei09.indd 1 17-05-2009 17:49:34 AW special mei09.indd 2 17-05-2009 17:49:36 A N C I E N T WARFARE Publisher: Rolof van Hövell tot Westerflier, MA, MCL Publisher’s assistant: Gabrielle Terlaak Editor in chief: Jasper L. Oorthuys, MA Sales and marketing: Tharin Clarijs Website design: Christianne C. Beall Art and layout consultant: Matthew C. Lanteigne Contributors: Duncan B. Campbell, Ross Cowan, Sidney Dean, Christian Koepfer, Jona Lendering, Paul McDonnell-Staff, Adrian Murdoch, P. Lindsay Powell, Michael J.Taylor. Illustrations: Andrew Brozyna, Igor Dzis, Stéphane de la Grange, Peter Nuyten, Carlos de la Rocha, Johnny Shumate. Design & layout: © MeSa Design, e-mail: layout@ancient-warfare.com Print: PublisherPartners. www.publisherpartners.com Editorial office PO Box 1574, 6501 BN Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Phone: +44-20-88168281 (Europe) +1-740-994-0091 (US). E-mail: editor@ancient-warfare.com Skype: ancient_warfare Website: www.ancient-warfare.com Contributions in the form of articles, letters and queries from readers are welcomed. Please send to the above address or use the contact form on our website. Subscription Subscription price is 33.50 euros plus postage surcharge where applicable. Subscriptions: www.ancient-warfare.com or Ancient Warfare PO Box 1574, 6501 BN, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Special 2009 4 THE SOURCE Four Misrepresentations 10 THE OPPOSING ARMIES Arming the warrior PRELUDE Bella Germaniae 17 FORTIFICATIONS 26 THE GENERALS 30 THE OPPOSING ARMIES Warrior tactics 48 52 THE BATTLE 62 AFTERMATH 70 THE BATTLEFIELD 74 THE BATTLEFIELD Arminius’ masterstroke Secrets from the soil Road to destiny Distribution Ancient Warfare is sold through selected retailers, museums, the internet and by subscription. If you wish to become a sales outlet, please contact the editorial office or e-mail us: sales@ancient-warfare.com Copyright Karwansaray BV, all rights reserved. Nothing in this publication may be reproduced in any form without prior written consent of the publishers. Any individual providing material for publication must ensure they have obtained the correct permissions before submission to us. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, but in a few cases this proves impossible. The editor and publishers apologize for any unwitting cases of copyright transgression and would like to hear from any copyright holders not acknowledged. Articles and the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of the editor and or publishers. Advertising in Ancient Warfare does not necessarily imply endorsement. 42 After Varus Looking for Varus THE OPPOSING ARMIES Augustan legionaries 37 THE OPPOSING ARMIES The legionary’s equipment In Varus’ footsteps Ancient Warfare is published every two months by Karwansaray BV, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. PO Box 1110, 3000 BC Rotterdam, The Netherlands. ISSN: 1874-7019 ISBN : 978-94-90258-01-6 Printed in the Netherlands Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 3 3 17-05-2009 17:49:46 The Source Four misrepresentations Varus’ defeat in narrative sources Catapult bolt stamped “Leg. XIX” from Döttenbichl, southern Germany. Together with the lead ingot depicted from Haltern, this is the extent of the epigraphical evidence for the Augustan 19th legion. Now in the Archäologische Staatssammlung, Munich, Germany. Until the Kalkriese excavations put an end to the long debate about the site where Varus’ legions were destroyed, the only evidence for the battle was a limited set of sources: Velleius Paterculus, Tacitus, Florus, and Cassius Dio. They are all biased. By Jona Lendering The truth of a scientific or a scholarly statement can be established in two ways: coherence and correspondence. The first approach means that a statement is considered to be true when it is logically deduced from, and coherent with, other well-established facts. The classic example is Euclidean geometry: applying logical means, the Greek mathematician built upon a small number of axioms and definitions a beautiful, grand structure of knowledge. In the second approach, we check a statement, perhaps by an experiment, by comparison to the phenomena. Assuming that all objects fell with a constant acceleration, Galileo climbed to the top of the leaning tower of Pisa, let loose all kinds of weights, and after many experiments, concluded that his hypothesis corresponded to the facts. Historians cannot take this second road. No one can go back to the year 9 to see how Varus’ legions were destroyed. Historical facts can no longer be observed; all we have is indirect evidence (literary sources, archaeological remains, coins, inscriptions). From a theoretical point of view, historical facts belong to the same category as quarks 4 and black holes: although we cannot observe them, we can deduce their existence because they have produced other, observable phenomena. The difference is that the astronomers’ data are pretty clear-cut, while historical sources are ambiguous, biased, and written in dead languages. How can we know that Saltus Teutoburgiensis must indeed be translated as ‘Teutoburg Forest’? Are the motives that our authors attribute to their actors their real motives, or are they merely what the authors thought that their motives had been? Historical interpretation can be hopelessly complex, especially when the sources are limited in number and literary in nature. As a consequence, dozens of theories have been brought forward about the battle in the Teutoburg Forest. They could only be evaluated by checking whether they were coherent with what was known from other sources. Until Kalkriese was discovered, it was impossible to establish correspondence between scholarly statements and archaeological facts. To be honest, ancient historians, hoping for the archaeological discovery © M. Eberlein, Courtesy of the Archäologische Staatssammlung, Munich, Germany. that has now taken place, have always concentrated on the written sources and have not been looking for other ways to check their ideas. As we will see, implausible ideas have had long lives. This can be explained partly from the fact that the ancient texts are exciting, so that it is easy to forget that they are incomplete and insufficient. Let’s therefore have a look at them to see what can and what cannot be deduced from them. Political bias: Velleius Paterculus Our oldest source for Rome’s Germanic Wars was written by a cavalry officer named Velleius Paterculus, who published a Compendium to Roman History in 30 AD. It ends with the reign of Tiberius, a former comrade-in-arms of Paterculus. Because of his enthusiasm for Tiberius’ reign, Paterculus has in the Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 4 17-05-2009 17:49:47 The Source the ill-fated general during the reign of Tiberius, probably - the words quoted above seem to suggest this - by blaming the soldiers. We do not know why Paterculus, writing two decades after the disaster, started to investigate again who were responsible. Of course it is proper that after a war the living defend the honor of the dead - a surprisingly great number of military historical publications was written with this purpose - but we cannot be certain whether this general pattern is applicable in this particular case. What we can do, however, is guess which conditions had to be met before Paterculus could criticize Augustus: the author must have had access to information that he considered to be more reliable than the authorized interpretation of the events. This information must have been given to him by eyewitnesses, and this means that we have to take Paterculus very seriously. Unfortunately, the problem remains that Paterculus, who wanted “to set forth in a larger work the details of this terrible calamity” (2.119.1), focuses in his Compendium on deeds of individual heroism. The author who seems to have had access to the best information, preferred to write something like a speech for the defense instead of a full account of the battle. Moralistic bias: Tacitus The best-known author on the RomanGermanic relations is the senator Cornelius Tacitus (c.56-c.120). It would be wrong to call him an historian, even though he presents himself as such. In fact, he is far too intelligent to be interested in the past only: he tries to fathom the dark depths of human nature and wants to establish how an aristocrat should act properly in the face of tyranny. Tacitus is a moralist. To him, the events in the Teutoburg Forest are an invitation to write a moral analysis, and his account is - like a play in a theater - constructed from contrasting stereotypes. The most important of these is the opposition between barbarism and civilization, represented by Germans and Romans. This contrast is certainly not one of utter darkness and complete light. The barbarous Germans have noble qualities - they long for liberty and are honest - while the civilized Romans must be on their guard for decadence and tyranny. And indeed, if civilized Roman society is threatened by tyrannical emperors, a decadent populace, and savage barbarians, important moral issues arise. In a free commonwealth, a man of dignity could show his care for the community by occupying a magistracy, but in a monarchy, this had become dangerous. The Roman prince Germanicus, however, had shown that it remained possible for an aristocrat, even in the dark days of the despotic Tiberius, to live up to the standards set by the heroes of the republic. Tacitus’ ambition to show that an honorable life remained possible, shapes his treatment of the battle in the Teutoburg Forest, which he mentions several times in his account of Germanicus’ retaliatory campaigns. For example, when the Roman commander decides to visit the battlefield, Tacitus attributes to him pious motives and ignores the fact that no superpower can allow its dead to remain unburied - it was imperative for the Romans to wipe out that symbol of its damaged invincibility. © Karwansaray BV past been criticized: the emperor had a bad reputation, and Paterculus’ passion was taken as evidence of his poor historical judgment. However, historians have reevaluated the career of Tiberius, and think it is unfair to criticize Paterculus’ admiration for a man who, as a general, simply was admirable. It has also been stressed that the author of the Compendium is one of the few historians who lives up to the standards that in Antiquity were set for a historian: he had experience as an official and a soldier, had visited the countries he describes, and had met many of the people whose deeds he describes. Few authors knew so well the tensions between the realities of a war zone and the Augustan propaganda. Although Paterculus adorns his account of Augustus’ reign with the usual compliments, it is easy to discern a portrait of Rome’s first emperor that is quite critical: it is significant that his account focuses on four military crises. The story of the annihilation of Varus’ legions must be seen as part of this portrait. Paterculus’ analysis of the massacre in the Teutoburg Forest is clear: “it is evident that Varus ... lost his life and his magnificent army more through lack of judgment in the commander than of valor in his soldiers.” (2.120.5) More precisely, the general had underestimated the Germanic tribal warriors, “entertaining the notion that the Germans, who were men only in limbs and voice, were human beings and that they who could not be subdued by the sword, could be soothed by the law.” (2.117.3) This is of course implicit disapproval of the man who had appointed Varus, viz. Augustus. It is also criticism of the aristocratic families who had been able to restore the reputation of Lead ingot marked by the 19th legion. To the left of the legionary name is the indication that the ingot weighed 203 Roman lbs. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern, Germany. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 5 5 17-05-2009 17:49:48 The Source © Karwansaray BV Augustan propaganda, or how the Romans liked to see themselves: a plaque showing a Roman soldier with a bound captive. The latter is probably a Gaul, judging by the shield hanging from the tree. The text indicates the workshop where the plaque was made. Now in the British museum, London. “Germanicus was seized with an eager longing to pay the last honor to those soldiers and their general, while the whole army present was moved to compassion by the thought of their kinsfolk and friends, and, indeed, of the calamities of wars and the lot of mankind” Tacitus, Annals 1.61 This burial makes pious Germanicus the opposite of evil Tiberius, who had executed retaliatory campaigns without attempting to bury the dead. However, in order to present Germanicus as the epitome of high moral caliber, Taci6 tus had to ignore something: that the young prince’s visit to the battlefield no matter how pious or rational - was a tactical mistake that easily might have led to a new military disaster. On his return from the funeral, Germanicus’ right-hand man Caecina almost lost an army larger than Varus’ in the wetlands between modern Münster and the Roman legionary base at Haltern. Tacitus presents it as a horror story: “It was a night of unrest, though in contrasted fashions. The barbarians, in high carousal, filled the low-lying valleys and echoing woods with chants of triumph or fierce vociferations: among the Romans were languid fires, broken challenges, and groups of men stretched beside the parapet or staying amid the tents, unasleep but something less than awake. The general’s night was disturbed by a sinister and alarming dream: for he imagined that he saw Varus risen, bloodbedraggled, from the marsh, and heard him calling, though he refused to obey and pushed him back when he extended his hand.” Tacitus, Annals 1.65 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 6 17-05-2009 17:49:49 The Source With descriptions like these, Tacitus distracts the readers’ attention from Germanicus’ responsibility. Had this been mentioned, Tacitus would have admitted that Tiberius, who had not risked the lives of his men with a march through the wetlands, had been the better general. To achieve his literary aims, Tacitus needs a stereotypical German. This barbarian is on the one hand the antiRoman and on the other hand the background against which Roman courage is best shown. As we will see below, Tacitus is not the only one to employ this stereotype. The problem is that parts of Tacitus’ German ethnography are almost fiction - archaeology has clearly shown that the Germans were no savages dressed in animal skins. But to Tacitus, moral typology is more important than historical accuracy. This makes the use of Tacitus as a source a rather frustrating exercise. He leaves out information that is important to an historian, focuses on trivialities, attributes motives that may be untrue. Still, because we have so few sources about the Varian disaster, Tacitus’ references to the battle are important. Besides, we know where he found his information: in the History of the Germanic Wars by Pliny the Elder, who had been able to interview survivors of the battle who had been taken captive and had been liberated in 50/51 by Publius Pomponius Secundus. Although Tacitus reworked the information he found in his source to suit his own aims, it goes back to eyewitness accounts and cannot be ignored. Topographical bias: Cassius Dio Tacitus’ moral and ethnographic bias has a topographic component. The barbarians were, according to the ancients, trapped in a vicious circle. Because they lived in the wilderness, arable farming was impossible, and they were forced to live as poachers and marauders. If someone had the idea to start a farm, his hostile neighbors would force him to give it up. Under these circumstances, there was no room for civilization, and therefore, the barbarian was socially handicapped. He would withdraw from people’s company, and preferred to live in solitude. There was no way out of this circle, and worse: the barbarian had to be permanently on his guard to protect his cattle against thieves. As a consequence, the barbarian had to be armed most of the time, and was a terribly efficient warrior, only comparable to the monsters that were known to live at the edges of the earth (cf. Paterculus’ remark that the Germans were humans only in limbs and voice). Because the Germans were barbarians, they had to be living in an unkind land with an unpleasant climate. References to forests and mountains are therefore to be taken with a pinch of salt: they are not descriptions of what Germania really looked like, but represent Greco-Roman ideas about what the land of the barbarians ought to be. Ideas like these were still common at the beginning of the third century, when senator Cassius Dio had difficulties in understanding the topography of the Germanic Wars. Yet, his History of the Roman Empire is written by a firstrate author. We cannot always check how he used his sources, but where we are able to do so - for example in his treatment of Caesar’s Gallic Wars - we can see that he summarizes carefully and without losing his critical judgment. Still, he has a topographical bias and sometimes makes mistakes when he wants to evoke what had happened. His description of the landscape in which Varus’ campaign took place, where “the mountains had an uneven surface broken by ravines, and the trees grew close together and very high” (56.20), is exemplary. The impenetrable forests belong to the stereotypical topography of the country of the barbarians. However, the Kalkriese area was, according to recent pollen research, an open landscape without great forests, and a small village with farms has been identified just west of Kalkriese. It must have been surrounded by cultivated, open fields. We will return to this point below; for the time being, it may be said that a Teutoburg Forest never existed in Antiquity. The topographical bias of our sources is but rarely recognized. Ancient historians who can easily see through the misogynic or political prejudices of the usually male, white, upper class writers of our sources, lose their critical instincts when faced with, for example, Tacitus’ remark that Germania was a poor and undeveloped country. Worse, modern historians have used this presumed poverty to explain why Rome eventually gave up its conquests east of the Rhine: there was nothing of value to be gained over there. One brief trip along the Lippe or Main, or to the gold mine near the Saalburg, would have been sufficient to discover that Germany is simply not as poor as the sources state. As noticed above, implausible ideas have proved to be surprisingly persistent. Rhetorical bias: Florus and Crinagoras A completely different type of source was written by Publius Annius Florus, a sophist (show orator) who published a Summary of Livy’s ‘Histories’ during the reign of Hadrian. In this presentation of Rome’s past, he focuses on anecdotes that orators might find useful for their speeches. He may not be Rome’s greatest historian, but it is possible to be too harsh in one’s criticism. When he says that after Drusus’ campaigns “there was such peace in Germania that the inhabitants seemed changed, the face of the country transformed, and the very climate milder and softer than it used to be” (2.30), he shares ideas with Tacitus and Dio, who are never criticized for their topographical bias. Other shortcomings of Florus are only mistakes if we measure him against the standard of a historian – which he was not. His text must be seen as some sort of speech and is indeed full of suggestive and entertaining details, which keep the audience interested. As a corollary, he sometimes loses sight of the main outline of his narrative, but his stories are lively and witty. It is no coincidence that in the nineteenth century, he was appreciated as a school author, which explains his remarkable influence on the historiography of the clades Variana. Florus’ account starts with Augustus, who has the idea that it would be useful to occupy the east bank of the Rhine. This makes the first emperor responsible for both success and catastrophe: the first by sending out Drusus, the second by appointing Varus. The expeditions of Tiberius and Ahenobarbus Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 7 7 17-05-2009 17:49:49 The Source and the retaliatory campaigns of Tiberius and Germanicus remain unmentioned. The last lines are about a “standard-bearer, who, carrying his eagle concealed in the folds round his belt, secreted himself in the blood-stained marsh”, which explains – according to Florus – why the Romans had only recovered two of the three legionary standards. Perhaps this incident inspired the Greek poet Crinagoras (c.70 BC - c. 11 AD) when he dedicated a little poem to a heroic soldier named Arrius, who managed to recover a military standard and died without having been defeated (Anthologia Palatina 7.741). Florus’ remark that the third eagle had not been recovered, betrays that his story is based on an eyewitness who could not see what happened next: that the Germanic warriors dredged the eagle from the marsh. We are sure that this happened, because the Romans managed to recover all lost standards: Germanicus obtained two of them, and the third one was discovered in 41 among the Chauci. We can conclude that Florus’ source was written between 17 and 40. Perhaps Florus’ criticism of Augustus belongs to the debate in which Paterculus took part as well: it was tasteless to blame the dead. Both authors stress Varus’ responsibility. As we will, see that may be an incorrect opinion. Pontes longi The “long bridges” were plank roads, causeways through marshy areas and bogs in Germany. They are mentioned by Tacitus in his description of the campaign of 15 AD, where he states that they had been made by Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (1.63.3-4), who had conducted a campaign north of the Danube, had reached the Elbe, and had returned to the Rhine through the country of the Cheruscans. This must have happened in 1 or 2 BC. Their location cannot be established with any certainty. 8 The battle according to the written sources It is frustrating that Paterculus and Florus, who had access to the stories of eyewitnesses, preferred not to write real histories. Tacitus had access to a slightly more recent source and might have written a good military history, but chose to look back upon the battle in moralistic terms. The only real historian is Dio, the latest of our authors. However, he ‘improved’ his account by exaggerating the importance of large forests and rocky mountains. Still, when we take into account the biases of our authors, we can recognize several more or less irrefutable facts. (1) Tacitus and Dio - probably independently - state that the battle lasted several days and was fought on heavy terrain. (2) The contradiction in our sources about the nature of this terrain is only apparent. If we had never had Dio’s references to trees and forests, we would have concluded, with Tacitus and Florus, that the massacre had taken place in a marsh, which would have been correct. The only other indication that the fight took place in a forest, is Tacitus’ name for the battlefield: saltus Teutoburgiensis. Of course the first word can be translated as “forest”, but it can also mean “narrows”, which is an adequate description of the situation at Kalkriese and probably is what Tacitus’s source meant. It may be no coincidence that at the western entrance of the passage between the Kalkriese mountain and the great bog lies the modern village of Engter, which also means “narrows”. (3) Our authors agree that the cause of Arminius’ insurrection was Varus’ attempt to convert Germania into a normal province with normal courts and normal taxes. (This is, incidentally, another indication that the country was not as poor as is often assumed.) Paterculus, Florus, and Dio suggest that Varus had a false sense of security which allowed his trusted adviser Arminius to lure him into a trap. The same authors mention that Varus had other advisers, who gave him more accurate information. The Roman general was, therefore, more competent than Paterculus and Florus insinuate, and the ultimate cause of the disaster may have been that Varus had no chance to evaluate his information: “after this first warning, there was no time left for a second”, Paterculus admits (2.118.4). (4) Tacitus names the tribes involved: the Cherusci, Bructeri, and Marsi. Probably, the Chauci took part as well, because it was in their land that in 41 the Romans recovered the remaining eagle (Dio 60.8.7). There used to be some doubt, however, because the manuscript refers to the otherwise unknown Kauchoi, not to the Chauci. This problem is now solved, because the double fan of finds at Kalkriese suggests that the army was originally marching from the east to the river Ems and the country of the Chauci, until it was attacked and started to move to the southwest. (5) According to Paterculus, the Romans lost three legions. From Tacitus, we learn that among these was the nineteenth, while the Caelius inscription confirms that legion XIIX vanished during “the Varian War.” That the seventeenth was also involved in the fight, is less certain, but can deduced from the absence of this number in the otherwise continuous list of legions. Although the Roman losses were serious, all sources imply that there were survivors. They also agree that Varus committed suicide. From Tacitus’ account, we may perhaps deduce that this happened in the Münsterland, because it was here, along the road from Kalkriese to the pontes longi and Haltern, that Caecina had a vision of the dead Varus. (6) Paterculus explicitly states that the battle was less important than Carrhae. This means that during the reign of Tiberius, the battle was seen as a setback, nothing more. Rome had not abandoned its claims, and from Dio and Tacitus we know that operations on the east bank of the Rhine continued. The only author who states that the Varian disaster was decisive is Florus, who concludes “that the Empire, which had not stopped on the shores of the Ocean, was checked on the banks of the Rhine.” Tacitus is less explicit but implies the same when he says that Arminius was “without any doubt the libera- Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 8 17-05-2009 17:49:49 The Source ©: Karwansaray BV The tombstone of Marcus Caelius is without doubt the most famous monument to the battle in the Teutoburg Forest and the only one explicitly linked to it. The text reads: “To Marcus Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian (voting) district, from Bologna, first centurion of the eighteenth legion. 53 years old. He fell in the Varian War. His bones may be interred here. Publius Caelius, son of Titus, of the Lemonian district, his brother, erected (this monument).” Now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany. tor of Germania” (Annals 2.88). Due to the popularity of Florus and Tacitus as school authors, the decisiveness of the battle in the Teutoburg Forest has become the standard interpretation, but it can be argued that the great, decisive event that determined the future of Europe was the creation of the limes along the Lower Rhine, and not the battle in the Teutoburg Forest. (7) The sources do not tell us why the Romans tried to conquer the land east of the Rhine. There is no written evidence for the common assumption that they wanted to move their frontier from the Rhine to the Elbe, an idea that must be incorrect because the Romans did not look at rivers as frontiers until Claudius created the Rhine limes. (Archaeology can add that so far, Roman forts have only been identified west of the Weser; there is no evidence for occupation of the land between the Weser and Elbe.) historical statements corresponded to the facts, that progress could be achieved. n So, all we can deduce from our sources is that Varus’ attempt to create a province in Germania provoked a rebellion of several tribes and caused the loss of three legions in a protracted battle in a marshy area, which was, once the limes had been created, regarded as decisive. It is frustratingly little, and it comes as no surprise that many historians have proposed all kinds of hypotheses, which could only be evaluated by checking whether they were coherent with our four sources. Given the fact that this quartet offers little real information, none of the theories was refutable. It was only when the Kalkriese excavations made it possible to check whether Jona Lendering is the webmaster of Livius.0rg, has discussed the battle in the Teutoburg Forest in two books, and is a regular contributor to Ancient Warfare. Further reading The translations cited in this article (sometimes slightly adapted) are all from the Loeb Classical Library, and were made by F.W. Shipley (Paterculus), J. Jackson (Tacitus), E.S. Forster (Florus) and E. Cary (Dio). They are online at LacusCurtius (http://tinyurl.com/dyhr5z) Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 9 9 17-05-2009 17:49:51 Prelude Bella Germaniae The German wars of Drusus the Elder and Tiberius 2009 marks the second millennium since the battle of the Teutoburg Forest. What the Romans called the Clades Variana – the “Varian Disaster” – which saw the loss of three legions among the trees and swamps of ancient Germany at the hands of Arminius. It will be the subject of dozens of articles published and documentaries aired during the year. Yet in focusing on the three fateful days of the battle in September of AD 9, it is often overlooked that up to that moment, Magna Germania, the name the Romans gave to the lands beyond the Rhine and Danube, was already well into a process of pacification intended to transform it into a fully functioning province. By P. Lindsay Powell It began with the wars of conquest between 15 BC and 6 AD during which the stepsons of Caesar Augustus, Nero Claudius Drusus (Drusus the Elder) and Tiberius Claudius Nero, fought a German called Maelo. Preparations Casus belli Up to 17 BC, the Romans seemed prepared to accept the Rhine as the northern limit of their imperial ambitions. The event that likely caused the Romans to rethink their policy on the Rhine frontier was what would come to be known as the clades Lolliana – the “Lollian Disaster.” In 17 BC M. Lollius was the propraetor of Gallia Comata and on his watch an alliance of the Germanic tribes on the right bank of the Rhine crossed the river and raided deep into the Roman province. “It was the Sugambri, who live near the Rhenus, that began the war”, asserts the geographer Strabo (Geography 7.1.4). He identifies Melo – Maelo in Augustus’ Res Gestae – as their leader, and the culprit. The Sugambri were joined by the Tencteri and Usipetes, tribes that had been looking for new homelands even in Caesar’s day. The timing could not be worse for the Romans, who had only recently quelled 10 117 – 138), also describes an event that would surely have sent a chill down the spine of any Roman reader. The Germans “had begun hostilities after crucifying twenty of our centurions, an act which served as an oath binding them together, and with such confidence of victory that they made an agreement in anticipation of dividing up the spoils” (History 30.24). It was while tracking down Maelo’s marauders that legio V Alaudae under Lollius’ command was attacked and its sacred eagle standard was taken. Augustus was so concerned by the news that he packed his bags and was about to set off to take command of the situation in person, but was persuaded to delay the trip until the spring of 16 BC. © Karwansaray BV The emperor Augustus (63 BC – AD 14) on a cameo cut from agate, rock crystal and marble, 1st century AD. Found in Rome, it was mounted in a fanciful setting (cut from the photograph) comprised of other ancient elements in the 18th century. Now in the Louvre, Paris. a revolt among the Gallic tribes. The historian L. Annaeus Florus, writing at the time of the Emperor Hadrian (AD Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (63 BC – AD 14) was a conservative man by nature, disinclined to take wild gambles and preferring to act only after having planned his moves thoroughly. Throughout his career he had been assisted by M. Vipsanius Agrippa, his younger friend by one year. He was in Syria on a diplomatic mission while Augustus was in Gallia Comata, but it seems certain that he would have contributed in a major way to crafting the strategy for Germania. Agrippa was twice propraetor for the region – from the spring of 39 BC to the autumn of 38 BC and again from June 20 BC to the spring of 18 BC. He had established cities there and laid down the first road network radiating out from his capital Lugdunum (modern Lyons). He was a superb strategist and tactician and the brains behind the victories at sea at Actium (31 BC) and on land against the Cantabri in Hispania (29 – 19 BC). Perhaps because he was so well travelled and knew key places first hand, Augustus had commissioned Agrippa to produce a map of the world (orbis terrarum). This map, which was prepared by his own team of Greeks and Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 10 17-05-2009 17:49:51 © Carlos de la Rocha Prelude famously put Rome at the centre of the world, would have given him more than any other man in the administration as complete as was possible then a view of the known-world – and the extent to which the world beyond was unknown. He must have been aware of how little was known about their Germanic adversaries and the lands they lived in. Magna Germania was not a single country but, like the Americas of a thousand years later, a patchwork of nations, tribes and clans. Based on Julius Caesar’s Gallic War, the Romans would have only known of some eight German tribes by name. These socalled ‘Germans’ (since they did not identify themselves by that name) were clustered around the Rhine (Rhenus) and Danube (Ister, Danuvius) and believed to have been descendants of the Celtic community called La Têne by modern historians, such as the tribes in Gallia Comata (or Celtica). Those further north and east shared a common linguistic and cultural tradition, different from the Celts, that may be called ‘Germanic’ such as the Cherusci and Chauci. Others were a mix of the two, sharing Celtic and Germanic characteristics, such as the Batavi and Belgae. As Roman observers like Strabo noted “different peoples at different times would cause a breach, first growing powerful and then being put down, and then revolting again, betraying both the hostages they had given and their pledges of good faith” (Geography 7.1.1). The Suebi were the nation most feared by the tribes closest to the Rhine and it was their migration that put pressure on the other tribes to move. The Rhine-Danube was not an impervious frontier. Just as Roman merchants crossed to trade their wares for amber, hides, horses and iron, the ‘Germans’ frequently crossed the rivers in boats to raid the lands to the south for rich pickings. The Cimbri and Teutones from Denmark and northern Germany raided down as far as the Italian peninsular until they were defeated by Marius at Aix-en-Provence Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 11 11 17-05-2009 17:49:53 Prelude ©: Karwansaray BV Drusus’ ditch Nero Claudius Drusus (38-9 BC), father of Germanicus and the emperor Claudius, and stepson of Augustus. Bust from the Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis, Brussels. (Aquae Sextiae) in 102 BC and a year later at Vercellae. The first Roman of importance to cross the Rhine in the other direction was Julius Caesar, first in 55 BC and again in 53 BC, famously building a bridge in just two weeks and marching his army across it, after the Ubii permitted him landfall on the right bank. Agrippa was only the second Roman of status to cross the Rhine. Attacked by the Suebi at its rear in 38 BC, the Ubii nation sought, and was granted, asylum by Agrippa on the left bank of the Rhine where it founded a new settlement, Oppidum Ubiorum on territory made vacant by Caesar’s extermination of the Eburones. One theory 12 Logistic considerations forced the Romans to use rivers to invade Germany. The Main and Lippe were easily accessible, because they emptied themselves into the Rhine. The Ems, Weser, and Elbe, on the other hand, could only be reached from the Wadden Sea, the lagoon-like rim of northwestern Europe, which was unfortunately not connected to the Rhine. The “Drusus’ Ditch” (Fossa Drusiana) mentioned in our sources must have been dug to solve this problem. Its location is a mystery. An old theory is that it connected Fectio (Vechten) to Lake Flevo and is identical to the modern river Vecht; an alternative hypothesis is that it connected Castra Herculis (Arnhem) to the river IJssel, which emptied itself into Lake Flevo. Since an inscription proved that Drusus had built a dam just upstream of Castra Herculis, this has become the preferred identification. Whatever hypothesis one prefers, the general idea was that the Roman ships used it to reach Lake Flevo, and to sail from there to the Wadden Sea, thus avoiding the treacherous North Sea. However, geological investigations published in 1986 proved that a wide strip of land separated the lake from the sea; it was swallowed by the sea in the twelfth century. To rescue the older hypothesis, it was pointed out that Fossa Drusiana is plural, and that a second canal might have been dug through this strip of land. In 2008, geoscientists discovered that the course of water between the Rhine and IJssel, the favorite location, was indeed a canal, but was dug in the tenth century. This leaves us, for lack of alternatives, with the Vecht hypothesis and a canal situated on a place that can no longer be investigated. The location of Drusus’ Ditches is bound to remain a mystery. is the first Roman fort referred to by archaeologists as ‘Neuss A’ (Novaesium) was founded to gather military intelligence in the region for Agrippa, located as it was at the end of the long road from Lugdunum. During the three-year sojourn, Augustus thoroughly reviewed the situation in the region. He understood that the stability of the western end of the empire was closely tied up with the intentions of the peoples across the Rhine, as the raid led by Maelo showed. Augustus brought with him his eldest stepson, the 26-year old Tiberius Claudius Nero – the future emperor Tiberius – and appointed him as propraetor to replace Lollius. Tiberius had proved his natural bent for military life while a tribune in Hispania and diplomatic skills when negotiating with the king of Parthia for the return of the legionary standards lost at Carrhae. Under him, Gallia Comata was reorganised into three new provinces – the Tres Galliae (“three Gauls”) – Aquitania, Belgica and Lugdunensis, while Provincia was renamed Narbonensis. When Augustus left Lugdunum in 13 BC, it is reasonably certain a plan for the invasion of Magna Germania had been worked out with his support and agreement, setting out the objectives, campaign strategy and resources. The initial goal appears to have been to set the new limit of empire at the river Weser (Visurgis). To carry it out, military forces would need to be assembled. Remarkably little is known about the deployment of the Roman army in the Gallic provinces at the time. In 20 BC, when Agrippa had crossed the Rhine for a second time, he had with him the legio V Alaudae and possibly part or all of legio VIIII Hispana. Legions XVII, XVIII and XIX may also have been stationed Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 12 17-05-2009 17:49:54 Prelude Bella Germaniae The first stage of the conquest of Germania was the subjugation of the central European alpine region. This might at first seem a strange priority, however, to move troops from east to west through the Gallic provinces, the only route available to the Romans without going through hostile territory was via the coast road in Narbonensis. By annexing the Alps and the land up to the Rhine and Danube, the Romans could shorten the frontier and begin their German campaign with greater ease. Perhaps in preparation for the campaign, the Ligurian Cottius, son of Donnus, was approached in his Alpine kingdom at this time to agree to provide safe passage for Roman troops and materiel. Augustus appointed his youngest stepson, Nero Claudius Drusus, who was then serving a term as praetor, to lead the campaign. By all accounts, he was dashing, charismatic, and handsome to boot, but he was a novice in military affairs. Just 23-years old, Drusus was, perhaps, being tested by Augustus for the grand campaign to come. In 15 BC, he entered the Alps from the south and achieved swift gains against the Raeti and Vindelici. He was quickly joined by his brother moving eastwards with legions from Tres Galliae. One of these was legio XIX, evidence for whose presence in Raetia has been found in the form of an iron catapult bolt point with its name stamped on it at Döttenbichl, near Oberammergau in Bavaria. Working together in a pincer movement, Raetia and Noricum were brought under Roman control in just one campaign season. To secure these gains, a fort was established at Augsburg (Augusta Vindelicum) and a vexillation of legio XIX was stationed at Dangstetten in Baden-Wurttemberg between c.15 BC and c.8 BC. Having proved himself able to command an army in the field, Drusus was now appointed legatus augusti pro praetore and assumed governorship of the Tres Galliae from his brother. Tiberius continued on eastwards to prosecute the war in Illyricum and Pannonia. Over the next two years (14-13 BC) Drusus oversaw a massive build out of military infrastructure and assembly of materiel in preparation for the invasion of Magna Germania. During this time fortresses were established along the Rhine at Xanten (Vetera), Neuss (Novaesium) and Mainz (Moguntiacum), with smaller forts in between, such as Moers Asberg (Asciburgium), Bonn (Bonna), and possibly Koblenz (Castellum apud Confluentes), Bingen am Rhein (Bingium) and Speyer, all linked by military roads. A fleet of ships was constructed, possibly with help from the local pro-Roman Batavi. Indeed, W.J.H. Willems notes that the Kops plateau around Nijmegen was originally densely wooded with oak and birch trees, but these were completely cleared away in the Augustan period. Were they felled to provide the vast amount of wood required to build the troop transports and barges? A canal (Fossa Drusiana) was constructed from the Rhine to the Gelderse IJssel or Vecht rivers – scholars continue to debate the precise location of the structure – to provide access to the Lake Flevo. This would save the Roman fleet from making a dangerous detour out from the Rhine to the North Sea. A mole or dam was also created at Herwen (Carvium) to regulate the flow of water between the rivers and the inland sea. This investment attests to the considerable care taken in preparing for this Roman D-Day-like campaign. It also possibly hints at the genius of Agrippa in the planning of the war – he was, after all, the architect of naval victories at Actium, Mylae and Naulochus, and the architect of great buildings and public works, such as the Pantheon, and the overseer to repairs to the Aqua Marcia and water supply network in Rome. © Karwansaray BV in the Tres Galliae – but it is far from certain if they were, or even where they were based. With the war against the Astures and Cantabri won in 19 BC, additional military units could be redeployed from Hispania. The tombstone of Marcus Mallius, a legionary of Legio I, who was ‘buried near the mole at Carvium.’ This text almost certainly refers to the same dam that Tacitus reported destroyed during the Batavian revolt. The image of the deceased would originally have been displayed above the inscription. Now in Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 13 13 17-05-2009 17:49:56 © Author’s collection, photo Michael V. Craton Prelude Left: Augustus on a denarius (obverse). Right: Germans offer up victory branches from Raetia to Augustus (reverse). According to Pliny this was a German sign of capitulation. Amphibious Operations On an autumn day in 12 BC, the campaign began in earnest when the army crossed the Rhine and entered the territories of the Sugambri, Tencteri and Usipetes. The mission seems to have been both punitive and intended to disable the tribes from causing trouble while the Romans were active elsewhere. Thus neutralized, the audacious amphibious campaign was launched. Possibly a thousand ships carrying as many as four legions sailed down the Rhine through the Fossa into the Lake Flevo. While intended to deliver troops deep into Germania, the mission may also have been in part a voyage of discovery to establish the true extent of the country; or perhaps based on their understanding of geography – the Romans thought this was a shortcut to the Elbe? – the rationale is not clear. There were some strategically worthwhile outcomes. The Batavi proved their loyalty and treaties were signed with the Cananefates and Frisii to pay tribute and provide men and supplies – indeed, the Frisii provided scouts and warriors and accompanied Drusus’ army from that point on. Clearly, the Romans did not only rely on the pointy end of a pilum to achieve their aims. Diplomacy also played a role in Roman military strategy, facilitated by the lure of trash and trinkets that its civilization offered. The fleet sailed into the Wadden Sea, overcoming resistance at Borkum or Bant (Burchania), before reaching the safety of the estuary of the Ems (Amisia). Part of the fleet sailed down the 371 km long Ems river, leaving the rest anchored at the mouth of river, while part may have sailed along the coast to explore the Weser (Visurgis). 14 The local but impoverished Chauci were engaged on land and soon sued for peace. Some way down the Ems the Roman fleet was attacked by the Bructeri, which the Romans repulsed. As the campaign season drew to a close, Drusus turned back, retracing the route home. While sailing along the Dutch coast several of the ships ran aground and were marooned, but help from the local Frisii freed the stranded ships and the expeditionary force was able to return to the Rhine for the winter. At the end of the first campaign season, Drusus could point to having established treaties with new allies and gained a better understanding of the political and physical geography of the coastal and western interior region of Germania. Agrippa would have watched with great interest from afar, but before the year had ended, he died at the age of 51. Augustus was devastated. More than ever he would need to rely on his stepsons to execute his military strategy. In 11 BC, Drusus turned his attention to the interior lands. From Vetera, his army crossed the Rhine and followed the meandering course of the 220 km long Lippe (Lupia). Supported by river craft carrying supplies, the route took his troops deep into the lands inhabited by the Sugambri and Cherusci nations. Drusus made swift progress because the Sugambri had gone to war against the Chatti for having failed to support them the previous year. Forts were established at Holsterhausen, Beckinghausen and Oberaden, parts of which have been excavated and dated to this time. A bridge was built over the Lippe and the advance continued. On their way to the Weser, Drusus’ forces encountered the Chatti who put up a fierce resistance but were beaten back. Drusus’ ambition would have driven the Romans into trouble had not his generals urged him to turn back concerned at the depleted supplies and the onset of autumn. A fort was constructed among the Taunus mountains, probably to station an intelligence gathering unit in preparation for the campaign the following year. Dio mentions the Romans gave the Chatti lands taken from the Sugambri. Guerilla warfare On the return journey, the army was ambushed by the Cherusci at a place called Arbalo. In Cassius Dio’s account the Cherusci had the upper hand during the struggle but did not press home their advantage out of “a contempt for them, as if they were already captured and needed only the finishing stroke” (Roman history 54.32). The Roman army would have been in formation for marching in hostile country, strung out over many kilometers, with its baggage train (impedimenta) under guard. Perhaps Drusus’ men were simply worn out from the demands of the campaign, or their equipment was in need of repair. The Germanic warriors fought both on foot and horseback and their preferred weapon was the framea, a spear that could be thrown long distance or thrust at close quarters. This weapon may have been particularly dangerous to Roman troops wearing standard-issue chain mail (lorica hamata). Whereas mail afforded good protection from the long slashing sword favoured by the Gauls, the Germanic weapon’s sharp point could pierce the shirts made of riveted interlocking iron or bronze loops. It is quite possible that the segmented articulated plate armour (referred to as lorica segmentata by modern historians, but almost certainly not called that by the Romans) was subsequently invented to provide greater protection from Germanic weaponry and styles of combat. Indeed, the earliest known remains of this plate armour were found at Dangstetten and dated to 9 BC, while other fragments have been found at Kalkriese, near Osnabrück. If not expressly designed for this theatre, the segmented armour was certainly being introduced at this Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 14 17-05-2009 17:49:57 Prelude On the return, somewhere between the Saale (Salas) and Weser, Drusus was wounded in an accident. On receiving the news, his brother rode from Pavia (Ticinum), covering hundreds of miles, and arrived just in time to catch his last words. Thirty days after his fall, at a place Suetonius says the soldiers called “the Accursed Fort” (Castra Scelerata, which Jürgen Martin Regel suggests is modern Schellerten, Germany), Drusus was dead. He was just 29 years old. Tiberius accompanied his brother’s body to Rome “causing the centurions and military tribunes to carry it over the first stage of the journey, as far as the winter quarters of the army” notes Dio (Roman history 55. 2). The body was laid in state in the Forum in Rome and two orations were given. Drusus’ ashes were placed in Augustus’ own mausoleum. An arch was erected in his honour in Rome and posthumously Drusus and his sons were granted the title Germanicus – “conqueror of Germania” – by which his eldest was thereafter known. De Germanis Tiberius returned to Germania the following year determined to complete the mission. Where his brother had used force, Tiberius chose to use diplomacy. Hearing that Tiberius had crossed the Rhine and was mobilizing his forces, the Rhineland nations sent emissaries to him to sue for peace. Initially absent were the Sugambri. Augustus told Tiberius he would not accept terms from the Germans unless the Sugambri were part of the peace deal. When the stakes began to rise, the Sugambri finally came to the negotiating table. Augustus states in his own memoirs that Maelo was one of several named kings that “sent me supplications” (Res Gestae 32). The terms offered to the Sugambri were different than those offered to the other nations. Like the Ubii before them, the Sugambri were relocated across the Rhine – one account mentions 40,000 – to the vicinity of Vetera (Xanten) where they became known as Ciberni or Cugerni. For his victories, Augustus granted Tiberius a triumph. Wells makes the case in his landmark book The German Policy of Augustus that the princeps did not intend the Elbe to be the final frontier. The war of conquest continued. In AD 1 L. Domitius Ahenobarbus, the first governor for Germania appointed by Augustus, actually crossed the Elbe – and was the first Roman of status to do so – and engaged the Hermunduri, which he relocated to Bohaemium in part of the territory of the Marcomanni. Dio notes that Ahenobarbus met no opposition from Marboduus’ people and formed a “pact of friendship” with them (55.10). He erected an altar to Augustus on the Rhine, the structure that gave the Ubian capital its new name, Ara Ubiorum (Cologne), and moved his headquarters there. He attempted to negotiate for Roman hostages held by the Cherusci, but the involvement of other tribes as intermediaries resulted in failure and loss of prestige among the Germans. Tiberius returned to Germania again in AD 4. G. Sentius Saturninus, Left: Drusus on a denarius minted by his son Claudius. Right: De Germanis – victory spoils from Magna Germania of hexagonal German shields, spears (frameae?), horns and a flag standard. © Author’s collection, photo Michael V. Craton time and worn by some Roman soldiers on active service in Germania. Drusus led his battered army back to the Rhine, for which the troops acclaimed him Imperator (commander). In an attempt to secure some gains, garrisons were posted at Oberaden and Haltern – the first time Roman troops had spent a winter on the right bank of the Rhine. Certain triumphal honours were granted to Drusus by Augustus. In 10 BC, Drusus advanced into Germania from Moguntiacum following the Main (Moenus) part way, hoping to reach the Elbe from this direction. The route took them headlong into conflict with the Chatti. They had finally formed an alliance with the Sugambri and their combined forces engaged the Romans near Mattium (near modern Kassel), the capital of the Chatti nation in the Taunus mountains. Despite the opposition, the Romans still punched their way through and made it to the Weser and even some distance beyond. When winter approached they had to turn back. In that same year Marboduus, an enterprising noble from the Marcomanni, who was educated at Rome, returned to his people with ideas about how he might introduce Romanstyle law and government. In a remarkable move, he convinced his tribe to relocate far away from Roman temptation and thousands of Marcomanni migrated to a new homeland in Bohemia (Bohaemium). In 9 BC, Drusus, now consul, marched out from Moguntiacum determined to reach the Elbe that year. It was a slash and burn campaign as the offensive force marched singlemindedly to achieve its mission. In the summer, the army finally reached the Elbe. Drusus would have crossed the river and driven deep into Suebi territory had he not had, what he evidently believed, was a supernatural encounter. Cassius Dio tells how Drusus was visited by a ghoul one night in his tent that demanded he leave immediately, with the warning that his days were numbered. Drusus was so disturbed by it that he decided not to cross the river and ordered, instead, that a trophaeum be erected (possibly at Poppenburg, near Hildesheim) and gave the order to march home. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 15 15 17-05-2009 17:49:57 © Author’s collection, photo Michael V. Craton Prelude Left: Drusus on a denarius minted by his son Claudius. Right: De Germanis – a triumphal arch erected in honour of Drusus’ victories in Magna Germania. who had been a legate under Drusus, now shared command of the campaign. During the next two-years the legions moved to new forward positions at Haltern and Anreppen (Aliso?) along the Lippe, and Marktbreit am Rhein in Bavaria. A new amphibious campaign took the fleet via the North Sea to the Elbe. Part sailed down the 1,091 km long river, while another sailed up the coast of Denmark. An inland invasion led to the Cherusci, Chatti and others again suing for peace terms. The brokered peace remained fragile and there were revolts among the Germanic tribes supposedly under Roman influence. Diplomatic setbacks notwithstanding, it seemed Germania Libera would finally bow to the Roman will. The Romans began their process of pacification – rapid urbanisation, introduction of Roman jurisprudence and a common currency, encouragement of trade, recruitment into the army and tax collection to pay for it all. The Romans by now had a much better understanding of the extent of Magna Germania. Tacitus, writing in the 80s and 90s of the first century, mentions forty tribes by name, which is five times the number than Caesar knew (Ptolemy writing in the 130s cited sixty-nine). Civilian settlements were rapidly founded by the Romans. The remains at Waldgirmes in the Lahn valley, discovered in 1993, complete with a forum and basilica, are proof of this. Others may yet lay awaiting discovery. Roads were constructed throughout the province according to Tacitus, a task usually entrusted to the army. When not involved in breaking and packing stones, Roman soldiers 16 would have been on police duty across the country and spending their small change in the local communities. Tacitus asserts in his Annals that the Germans did not live in towns, yet in the Histories he mentions Mattium, the capital of the Chatti. Further, a study of Claudius Ptolemaeus’ Geography, reveals a remarkable list of named places – including strangely non-Roman sounding names such as Coenoënum, Galaegia, Leufana, Lirimi and Susudata (Geography 2.10). Assuming they are not inventions of Ptolemy’s imagination, these places may have predated the invasion. Excavations at Feddersen Wierde and Flögln, both in Lower Saxony, and Meppen on the Ems river, have revealed substantial native settlements of regular shaped wooden buildings for people and livestock. These German farmers now sold their wares in Roman markets in exchange for Roman goods and currency. With such rapid progress being made, in AD 6 Augustus appointed his new provincial governor to continue the process of Romanisation: P. Quinctilius Varus. And what of the protagonists? The warchief of the Sugambri, Maelo, who started the war, disappears from history. His brother, Baetorix, and nephew, Deudorix, are mentioned by Strabo as having been exhibits in a later triumph of Drusus’ son Germanicus. Cottius was appointed by Augustus as praefectus of the dozen tribes in his region of the Alps and assumed the Roman name M. Julius Cottius. He honoured his patron with a triumphal arch in his capital of Susa (Segusium), which still stands. King Maroboduus and the Marcomanni were now the only remaining obsta- cles to completing the conquest of the country between the Elbe, Rhine and Danube. In late AD 6, Tiberius executed his plan to take the Marcomanni in their homeland of Bohaemium. It was the largest operation ever conducted by the Roman army. At least twelve legions were involved: VIII Augusta from Pannonia, XV Apollinaris and XX (later know as) Valeria Victrix from Illyricum, XXI Rapax from Raetia, XIII Gemina, XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica from Germania plus an unknown unit; while I Germanica, V Alaudae, XVII, XVIII and XIX would attack along the Elbe. However, a rebellion in Pannonia stopped the massed army in its tracks. It took three years of blood and treasure to quell the revolt. Taking part in suppressing that violent insurgency was a young Cheruscan noble leading a Roman cavalry unit. He is known to history as Arminius – ‘Hermann the German.’ n P. Lindsay Powell was born in Wales and developed a life-long interest in Roman history while at school. He is a veteran of The Ermine Street Guard. He has published several articles on aspects of the Roman army and is writing a novel of the German Wars of Drusus the Elder and Tiberius Caesar. He divides his time between Austin, Texas and Wokingham, England. Email him at info@lindsaypowell.com Further reading - M. Carroll, Romans, Celts and Germans: The German Provinces of Rome. Stroud 2001 - J.F. Drinkwater, Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces 50BC-AD260 London 1983 - A. Everett, Augustus: The Life of Rome’s First Emperor. New York 2006 - C.M. Wells, The German Policy of Augustus: An Examination of the Archaeological Evidence. Oxford 1972 - P.S. Wells, The Barbarians Speak: How the Conquered Peoples Shaped Roman Europe. Princeton 1999 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 16 17-05-2009 17:49:58 Fortifications Secrets from the soil The archaeology of Augustus’ military bases Archaeology has been called the ‘handmaiden of history’. Its role is often subordinated to the study of the historical texts. But should these always be elevated to this position of primacy? Without the archaeological study of the sites along the Rhine and in the interior of Germany, we could speculate endlessly on the movements and campaigns of Augustus’ armies. It is only by correlating the narrative sources with the results of archaeological excavation that we obtain a more complete picture. And the material remains provide one or two surprises along the way. By Duncan B. Campbell is clear that it in no way represented a frontier between the Celtic Gauls and the Germanic nations. The Helvetii, for example, had originally lived across the Rhine before they migrated into the © Carlos de la Rocha When Julius Caesar laid down his Gallic command in 51 BC, the border of Gallia Comata (“long-haired Gaul”) lay along the Rhine. This was certainly a convenient administrative boundary, but it Roman province, provoking Caesar’s intervention. Other nations, like the Belgic Eburones in the northeast of Gaul, had made the transition earlier; they were a ‘Gallic’ people of Germanic extraction. And when Octavian finally fell heir to Gaul in 40 BC, the subsequent revolts that occupied his governors usually involved collaboration between the Belgic nations and their erstwhile Germanic cousins across the Rhine. Clearly, the river did not represent a cultural barrier. In fact, Augustus himself recognised this in his treatment of the long corridor of land along the left bank of the Rhine. Notionally belonging to the province of Gallia Belgica, it was set apart as a military zone, to be divided between the armies of Germania Superior (“Upper Germany”) and Germania Inferior (“Lower Germany”). Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 17 17 17-05-2009 17:49:59 Fortifications So, from the time of Caesar, the Romans had maintained a foothold in Germany; they were simply awaiting the opportunity to extend their control. In 16 BC, when Augustus was ready to turn his attention to Germany, having brought Gaul and Spain into line, it was only natural that the legions should be poised on the Rhine. Several major sites can be identified, chiefly because they developed into the familiar legionary fortresses that remained occupied throughout the period of the Principate. However, the Augustan precursors of these fortresses are not well known and still have many secrets to divulge. The Rhine: Nijmegen © Karwansaray BV. At Nijmegen, in the territory of the Germanic Batavians of the Rhine delta, the known legionary fortress sat on the Hunerberg, an area of high ground overlooking the Waal, a continuation of the Rhine. The site was named Batavodurum, and renamed Noviomagus after the Batavian revolt of AD 69/70. The exceptionally small (16.5ha) Flavian fortress, which is known 18 in some detail, was preceded by an enormous Augustan base occupying the entire 42ha area of the hilltop. Its northern defences have yet to be elucidated, but they probably ran along the steep cliff top overlooking the river. Elsewhere, a double ditch was traced, the inner of which was some 6m wide by 2.3m deep, with an outer ditch of slighter proportions. These presumably remained open and in use well into the Julio-Claudian period, to judge from the date of the pottery sherds recovered from the infilling. Curiously, no trace of the rampart survived, perhaps because the turves had been laid without foundations. But there was ample evidence of the towers that once dotted the rampart at 24m intervals. In each case, four substantial postholes marked out a 3.6m x 3m structure, which must have risen to a second storey, perhaps giving a 5m-high vantage point. Both west and east entrances were carefully excavated, to reveal the characteristic Augustan design of gateway, incorporating a recessed double portal. On either side of the entrance, instead of a standard four-post tower, the rampart ended in a six-post tower, which then turned inwards in a massive L-shaped arrangement, before turning again to span the gateway. The net effect was to create a small courtyard, 6m deep by 10m wide, around which Iron Weisenau-type (Robinson Imperial Gallic A) helmet from Nijmegen which was found together with the shield boss and strigil in a pit on the Hunerberg. Now in the Valkhof Museum, Nijmegen. (Note that this is a photo montage, the items are not shown proportional to their size). the walkway was carried at rampart level. Anyone approaching the gates was under observation from all sides. The eastern half of the base was obliterated by the Flavian fortress. But in the western half, excavations during the 1990s exposed an area running in from the west gate along the line of the main east-west road, surely the via principalis. Details of internal timberframed buildings were revealed, chiefly to the south of the road, all sharing the same alignment. Several foundation trenches produced Augustan pottery sherds, confirming the general dating of the base; likewise the many refuse pits dotted around the buildings. The presence of certain forms of terra sigillata (“samian ware” pottery) indicates an early date, perhaps as early as 19 B.C., further confirmed by coinage from the mints of Nemausus (present day Nîmes) and Lugdunum (Lyon). Just visible in the northeastern corner of the excavation area, and thus roughly in the middle of the base, were the foundations of a wall flanked by a row of timber uprights, hinting at the courtyard which was a characteristic component of the legionary headquarters building (principia). The rest was unavailable for excavation. Unfortunately, the large building exposed some way behind it had been partly destroyed by the Flavian ditch. From its position and large size (c. 60m wide), the building was probably the commander’s house (praetorium). Archaeologists exposed several rooms and part of the peristyle courtyard, typical in an upper class Mediterranean-style house. Elsewhere, smaller examples of this atrium houseplan, incorporating a central courtyard, probably represented accommodation for tribunes; although junior to the commander in both age and rank, these were still upper class Romans who expected some home comforts while on campaign. Clearly this base was rather more permanent than the winter quarters (hiberna) endured by Caesar’s troops in Gaul. Many of the remaining features encountered during the excavations belonged to the barrack blocks of the legionaries. These characteristically long, thin buildings, designed to accommodate an entire company of Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 18 17-05-2009 17:50:00 men (centuria), often revealed traces of the cross-walls separating the individual squad rooms (contubernia). In common with other Augustan fortresses, the remains were often found to be rather ephemeral, but the centurion’s house, always located at one end of the block, seemed usually to have been more robustly built. This is perhaps only to be expected, given the centurion’s rank and status. The precise functions of the four or five rooms within each centurion’s house are unknown, though separate sleeping, eating and latrine areas might be imagined. Frustratingly, no evidence has come to light that might identify the troops quartered here, but the size of the Hunerberg base suggests that we should think of a pair of legions, probably with auxiliary support. A base located here, on the last available area of high ground before the coast, was obviously linked to amphibious operations around the Rhine delta, as well as probing attacks into the lands of the Usipeti and their eastern neighbours, the Chauci. Just such operations were apparently mounted in the year 12 BC by Augustus’ stepson Nero Claudius Drusus. “Next Drusus crossed over to the country of the Usipetes, passing along the island of the Batavians, and from there marched along the river to the territory of the Sugambri, much of which he devastated. He then sailed down the Rhine to the ocean, secured the alliance of the Frisians and, crossing the lake, invaded the country of the Chauci, where he ran into danger, as his ships were left stranded by the ebb of the ocean. He was rescued on this occasion by the Frisians, who had joined his expedition with their infantry, and withdrew since it was now winter.” Cassius Dio, History of Rome 54.32.2-3. A little way to the east of the Hunerberg lies another area of high ground, the so-called Kops plateau. Here, a 3m wide earth and timber rampart fronted by a double ditch followed © Karwansaray BV. Fortifications Sword scabbard decoration found at the Fürstenberg, near Castra Vetera. Two Eros-figures hold a shield with a wreath, under the shield is an eagle. Now in the Römermuseum, Xanten. the contours of the hill to create a roughly triangular fort of 3.5ha. Finds of pottery, particularly from a rubbish dump (Schutthügel) on the northern slope of the plateau, indicated a date much earlier than the well-known assemblage from Haltern and more in line with the material from Oberaden (see below for these sites). In short, the site belongs firmly to the campaigns of Drusus. In fact, as we shall see, it has been hailed as his command post in 12 BC, although the case is purely circumstantial. An impressive praetorium, equally as large as the Hunerberg example, stood over towards the north rampart in a rather unorthodox way; the commander’s house usually occupied a more central position. Its large size, in such a small fort, has raised the suspicion that its occupant was a very important personage, although the peristyle building in the similarly sized fort at Rödgen (see below) is not much smaller. Equally, the Kops plateau fort was refurbished in the early years of Tiberius’ reign, and the praetorium may date from that later phase, which also produced quantities of luxury decorated terra sigillata pottery, some from the workshops of the Ateius family. The stamp on the base of one dish indicated that it had been made by a slave of the XIIIth legion (leg(ionis) XIII vern(a) fe(cit) : AE 2000, 1012). The remains of foodstuffs included a pot containing the bones of 30 song thrushes, surely something of a delicacy for a high-ranking Roman. The Rhine: Xanten If the Nijmegen base was sited with an eye to the northern Germanic nations, a second base 50km further upriver near present-day Xanten was clearly intended to control and exploit the River Lippe, which flows from the east into the Rhine at just this point. The siting of successive fortresses here, perched on the high Fürstenberg, emulated Nijmegen’s similarly elevated position. And campaigning along the Lippe is recorded amongst the events of 11 BC. “As soon as spring arrived, Drusus set out again for the war, crossed the Rhine, and subdued the Usipetes. He bridged the Lupia (River Lippe), entered the territory of the Sugambri, and advanced through it into the country of the Cherusci, as far as the Visurgis (River Weser).” Cassius Dio, History of Rome 54.33.1-2. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 19 19 17-05-2009 17:50:01 Fortifications 20 been planted on a virgin site. A separate length of ditch, displaying a classic v-shaped profile but measuring only 2m wide by 1.2m deep, underlay the area required by Camp A-C, and must have belonged to a different phase of occupation. Nothing more is known about this so-called “Camp B”, and we may wonder whether it was, in fact, a marching camp built for the temporary accommodation of troops in transit. A similar situation is found, for example, at Haltern (see below). Later still, another fortress was laid out on the site; its rampart base and parallel ditches were traced for 300m as they curved around the SW corner. With ditches 4.5m and 3.6m wide and around 1.5m deep, these were formidable defences. However, the excavator was able to show that they belonged to the reign of Tiberius, since they cut through a layer of burnt Tiberian pottery debris. Sadly, we have no indication of the size or garrison of this later fortress. The Rhine: Mainz Travelling a further 60km up the Rhine brings us to Neuss, the site of the famous Claudian legionary fortress of Novaesium. However, traces of defensive ditches associated with early terra sigillata pottery suggest that there was Augustan occupation nearby. Such early pottery has also been found at Cologne, 40km further south, where two legions had their base in AD 14 (Tacitus, Annals 1.39). There may have been earlier occupation here, as well; particularly if the graffito allegedly belonging to the “chief centurion of legion XIX” (AE 1975, 626: prin(ceps) leg(ionis) XIX) has been correctly read. A similar situation obtains 30km further on at Bonn, where archaeology has revealed the Claudian fortress of Bonna, but pottery hints at an earlier occupation. And finally, 60km further upriver, the hilltop at Koblenz, overlooking the confluence of Moselle and Rhine, has been suggested as the site of an Augustan fort, on the basis of a few early finds. Such a chain of strongpoints is perhaps more in tune with Tiberian or Claudian retrenchment than with Augustan expansion. But the site of Mainz, 80km upriver from Koblenz, is different. Just as the Xanten base was located opposite the mouth of the Lippe, the base at Mainz sat on high ground above the Rhine, opposite the mouth of the River Main. This was another ideal jumping-off point for an invasion of Germany, this time targeting the lands of the Chatti, as recorded for the years 10 and 9 BC. “Meanwhile the Germans, especially the tribes of the Chatti, were in some cases harassed, in others subdued by Drusus. … In the following year, Drusus … proceeded to invade the lands of the Chatti, and advanced as far as those of the Suebi.” Cassius Dio, History of Rome 54.36.3 & 55.1.2 Detail of some the palisade stakes from Oberaden, clearly showing the markings of the centuria to which they originally belonged. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. © Karwansaray BV. Excavations were conducted on the Fürstenberg at the beginning of the 20th century, when techniques had not yet reached the sophistication that we expect nowadays. Nor was the task of elucidating the early occupation here an easy one. At Nijmegen, we have seen that a large proportion of the original Augustan base remained undisturbed by subsequent occupation. But here, the Julio-Claudian phases on the Fürstenberg were obliterated by a huge (56ha) double fortress, built in stone during the reign of Nero. At some point, the site was named “the old camp” (Tacitus, Annals 1.45: Castra Vetera). Of course, there can be no doubt that an Augustan base lay here. If the historian Tacitus had not recorded that Augustus established a legionary fortress here (Histories 4.23), the discovery of the famous cenotaph of Marcus Caelius, the centurion of legion XIIX who “perished in the war of Varus” (ILS 2244), would have given us a heavy hint. Sadly, the layout remains unknown, but one or two traces have been found. At the northern edge of the Fürstenberg, a substantial military ditch, 6.5m wide by 2.5m deep, was traced for 500m. Two bedding trenches ran along behind it, marking out a 3m-wide rampart. Around 700m to the south, a similar ditch was found, this time with the rampart to the north. If the two ditch lengths belonged to the same fortress, as seems likely, it must have extended for more than 35ha, quite sufficient for two legions. And its fortifications, just like those of the Nijmegen base, must have formed an irregular polygonal perimeter, unlike the classic playing-card shape of its Neronian successor. Both the northern and southern features showed signs of remodelling, suggesting a lengthy period of use subdivided into two phases. A 10m wide break in the southern ditch marked the position of one of the gateways, fronted at a distance of around 9m by a 22m long titulus, the protective bank and ditch often found covering the entrances to a camp. It, too, showed signs of refurbishment. Dating evidence was sparse, but included a late Augustan Nemausus as. This fortress (known to archaeologists as “Camp A-C”) may not have Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 20 17-05-2009 17:50:02 Fortifications The site that the Romans knew as Mogontiacum is entirely built up now, but observations over the years suggest that the fortress enclosed an area of perhaps 36ha inside an almost rectangular perimeter. In the 1950s archaeologists were able to examine an area of around 2.5ha spanning the southeastern defences. In the course of their excavations, definite Augustan remains were identified underneath the stone Flavian fortress. The sequence of seven ditches demonstrates the complicated phasing of the site, as not all will have been in use simultaneously. Curiously, one of them seems to have been a “Punic ditch” (fossa Punica); instead of the usual v-shaped profile, it has an almost vertical outer wall, perhaps to prevent an attacker from retreating once he has crossed it. One or two of these seven ditches must have been contemporary with the earliest rampart, an earth-filled box construction with timber revetment at front and rear. Behind it, the usual intervallum space found in all fortresses extended for 12m, accommodating a mix of rubbish pits, hearths, ovens and the ephemeral traces of lean-to sheds. Along the inside margin ran the 3m-wide perimeter road (via sagularis), allowing troops to speedily make a circuit around the fortress to any threatened position. Its gravelled surface had been repeatedly repaired, incorporating ceramic fragments of Augustan date, and finally building up to a thickness of 1.4m! The water supply for this early fortress remains problematic, but it is perhaps unsurprising that no wells were identified, as little of the fortress interior is known, beyond the ends of some nondescript buildings running up to the via sagularis. The Lippe: Oberaden Nijmegen, Xanten and Mainz represented the main Rhine bases that must have been established in good time to support Drusus’ campaigns. The archaeology is in broad agreement with Cassius Dio’s narrative, though the absence of any securely dated corroborating evidence is disappointing. Dio records that Drusus’ second campaign centred on the River Lippe with its broad east-west valley, opening opposite the Vetera fortress and penetrating the heartlands of the Sugambri. It is here that we must search for the earliest Roman fortress beyond the Rhine. In fact, 90km inland along the Lippe, an enormous (56ha) oblong base was sited on a hill at Oberaden near the modern town of Dortmund. Excavations in the early years of the 20th century revealed the four gateways and traced the 2.7km perimeter. A 5m wide, 3m deep ditch lay some way in front of a 3m wide earth-and-timber rampart, strengthened with towers at 25m intervals. Archaeologists estimated that up to 25,000 trees must have been felled in the neighbourhood to build the defences. Like the Rhine fortresses, this was a permanent base, designed for year-round occupation. “Drusus was scornful of the enemy (Sugambri) and built a fort against them at the junction of the Rivers Lupia and Eliso, and another amongst the Chatti on the Rhine.” Cassius Dio, History of Rome 54.33.4 A fascinating detail was preserved along the northwestern sector, where the ditch was found to contain around 300 wooden stakes, sharpened at both ends with a handle in the middle. Once identified with Caesar’s pila muralia (Gallic War 5.40), they are nowadays given the less contentious label of ‘palisade stakes’; they had probably been set up as an additional obstacle, perhaps along the lip of the ditch. The fortress gateways followed a similarly robust design to those found at Nijmegen. Modern excavations in the 1980s and 1990s concentrated on the area between the headquarters (principia), centrally located as usual, and the front gate (porta praetoria), which in this case faced south. Oberaden’s seven-sided perimeter is by no means unusual amongst the generally irregular shapes of Augustan fortresses, but its internal layout differs from later orthodoxy on two counts: first, the main street (via principalis) runs along the long axis, instead of the short axis preferred by later generations of surveyors; and second, this street runs behind the principia, rather than in front. A final pecu- Archaeological dating It is a complex process to date an archaeological site from the objects found there. Much depends on the type of object and the context of its discovery. A Roman coin (particularly from Flavian times onwards) can often be dated very precisely to a twelvemonth period, but we should remember that this simply tells us when the coin was struck. A single coin could remain in circulation for years or even decades, before finding its way into the archaeological record. And a coin recovered as a stray find in the topsoil of a site has much less value for dating purposes than a coin that was sealed in a primary foundation layer. Pottery is often an archaeologist’s best guide to dating. The Roman army used the red gloss tableware known as terra sigillata (“samian ware”) in huge volumes. The various forms of TS were driven by fashion and changed frequently. In addition, the different workshops, which were mostly still located in northern Italy for much of Augustus’ reign, often stamped their products, enabling us to trace the work of individual potters (e.g. the wellknown Ateius family). But the argument can become circular, as with the Augustan ceramic assemblage from Haltern being used as a fixed point for the wider TS chronology. Other dating methods have become available, as archaeology embraced the scientific techniques of the 20th century. Amongst the first to be embraced was radiocarbon dating, despite two drawbacks: first, it destroys the organic sample during the dating process; and second, the date it provides has a broad margin of error. However, a second technique has come to the rescue. Thanks to the careful recovery and analysis of ancient waterlogged oak and pine timbers in western Europe, dendrochronology has provided an almost complete tree-ring chronology going back over 10,000 years. Unfortunately, the technique fixes the felling date of a tree by identifying the final growth ring, which is not always possible if the archaeological sample is too small. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 21 21 17-05-2009 17:50:03 Fortifications the Lugdunum altar series, a large issue probably intended for soldiers’ pay, suggests that the garrison had left within a few years of 10 BC; archaeologists agree that the fortress was probably evacuated after the campaigning season of 8 BC, which saw the acquiescence of the Sugambri. “… Tiberius crossed the Rhine. All the barbarians were alarmed and sent envoys to make peace … After this, the Sugambri remained at peace for a while.” Cassius Dio, History of Rome 55.6.2 The Lippe: Beckinghausen The fortress at Oberaden lies some distance south of the Lippe, showing that its hilltop location, reminiscent of the Rhine fortresses, took precedence over ease of supply. However, a small base of the sort best characterised as a fort lay 2.5km to the west at Beckinghausen, right on the bank of the Lippe. Its position has often led to its description as a “waterfront fort” (Uferkastell), but the course of the Lippe has changed dramatically over the centuries (as we shall see at Haltern, below), and it is Iron Weisenau-type (or Robinson Imperial Gallic ‘F’) helmet with bronze decorations from Oberaden. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. 22 © Karwansaray BV. liarity involves the siting of the gates, which were each slightly offset from the line of the internal streets. Within the fortress, quantities of clay wall plaster were recovered, still displaying the impression of the wickerwork that must have formed the walls of the half-timbered buildings. There was ample provision of wells for drinking water. One of these, located in the courtyard of an atrium house (presumably a tribune’s billet), proved to be lined with timber slats to a depth of 5m, and contained wooden roof tiles and a 1.26m length of ladder. Elsewhere, when the wells did not take this square, timber slatted form, they utilised old wine casks, sunk up to 9m in the ground, still complete with bung hole and importer’s name branded on the side. Three oblong wood-lined tanks located behind the rampart, roughly 5m x 12m in size, defied explanation, but have been tentatively identified as latrines. One of them contained roofing debris, along with the usual rubbish that clean-up squads typically toss into such places to avoid having to bury it. Seed and pollen analysis affords a rare glimpse of the Augustan legionary’s diet: wheat was well represented, along with lentils and millet; apples, sloes, raspberries and hazelnuts were present, as well as whitethorn and rosehip, perhaps for medicinal purposes; and various imported foodstuffs, including olives, figs, grapes, almonds, and most surprising of all, peppercorns. Fortuitously, the sheer quantity of wood recovered from the excavations, buried deep in the wet clay soil, allowed accurate dendrochronological analysis. The oak timbers used to build the rampart had been felled in the late summer of 11 BC, a fact that neatly corroborates Cassius Dio’s historical account (see above, Xanten). Unfortunately, the date of abandonment cannot be fixed with such precision, but the absence of coins of unlikely that any Roman fortifications lay open to the river. The fort took the form of an elongated oval, 1.6ha in area. Triple ditches fronted a rampart with towers every 30m but only one entrance, located at the west end and marked by the standard massive gateway structure. Little of the interior was available for excavation; apart from a large granary, only some nondescript buildings and two ovens were identified. Pottery from one of these matched similar finds from Oberaden, and the few coin finds included the same Nemausus asses found in the main fortress. Of course, it is virtually certain that the fort and fortress were symbiotic; the legionaries in garrison at Beckinghausen were clearly placed there to receive riverborne supplies in transit to the Oberaden fortress. The Wetter: Rödgen Archaeologists have also sought Drusus east of Mainz, in the lands of the Chatti where campaigning took place in 10 and 9 BC. In fact, in the 1960s, an Augustan fort was discovered and excavated at Rödgen, near Bad Nauheim, about 60km northeast of the Rhine. Here the fortifications followed the contours of a hill, enclosing an area of 3.3ha with a double ditch and 3m wide rampart. The single gateway, located on the east side of the polygonal perimeter, conformed to the standard massive design, but the ditch remained unbroken in front of it, so that there must have been some kind of bridge. The somewhat unusual headquarters building excavated at the centre may, in fact, be the commanding officer’s house. Whoever he was, he appears to have been in charge of a supply base. For, although rows of barrack blocks have been identified, much of the fort interior was taken up by three huge granary structures. Coins of the Lugdunum altar series were missing here, suggesting a similar chronology to that of Oberaden. The pottery recovered from both sites was very similar, and we must wonder whether Rödgen was Drusus’ fort established “amongst the Chatti on the Rhine”. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 22 17-05-2009 17:50:04 Fortifications The Main: Marktbreit Troops were perhaps also moving in a more southerly direction from the Mainz base. The Augustan fortress identified at Marktbreit near Würzberg lies fully 150km away as the crow flies, and much farther for legionaries marching along the winding course of the River Main. The site fits the standard image of an Augustan base in every way: sited on a hilltop, the surveyors followed the contours of the land in laying out its irregular perimeter; its 2.8m wide rampart was fronted by a double ditch; the entrances are marked by massive gate structures; and the internal street layout has its own peculiarities. (In this case, the via principalis, normally the main thoroughfare from one side of the fortress to the other, appears to be blocked by buildings.) At 37ha, it falls into the category of two-legion fortress, just like Mainz itself, and the dating material conforms to the “Haltern horizon” (see further below). Marching camps on Lippe and Lahn Roman armies on the march typically built temporary camps for overnight accommodation. The presence of permanent bases deep within Germany implies that troops en route from the Rhine must have broken their journey behind more temporary fortifications. Unlike the fortresses, these were not intended for permanent occupation, but were simply ditched enclosures to afford the soldiers some degree of protection. Mostly laid out as giant rectangles, they shunned the hilltop locations preferred by the permanent fortresses, and lacked any internal buildings. One such camp has long been known in the Holsterhausen area of Dorsten, on the north bank of the Lippe. At 36km east of the Rhine, this would have been an ideal first stop for troops coming out from Vetera. And, at 54ha, it could accommodate a sizeable battle group involving at least two legions. As expected in a marching camp, there were no structures, for the troops were accommodated in tents, but rubbish pits and field ovens were identified. No trace of the rampart survived, but the single ditch was found to be 4m wide and up to 3m deep, a sen- sible precaution in enemy territory. The perimeter was broken by three 10m wide entrance gaps, much of the fourth side having been washed away by the Lippe. Following the excavations in the 1950s, there were traces of a second camp lying immediately to the northwest, but nobody expected the complex of five (with hints of another two) new camps that came to light over to the west in 1999-2002. Partially overlying one another, these speak eloquently of successive campaigns along the Lippe by battle groups making their first stop here. Such complexes of military works are also known from Britain, and indicate the Roman expertise in reconnoitring an ideal position and revisiting it from year to year. Aerial photography recently revealed traces of a tenth camp, 2km to the north. Besides pits and field ovens, wells had been dug. Clearly, temporary accommodation could extend over several days, or even weeks, depending upon the circumstances. And the history of these camps was not perhaps entirely uneventful: a hoard of 36 denarii had been buried in a pit, presumably for safe keeping but never recovered; its owner perhaps went out on patrol, never to return. Some of the material finds, such as coins of the Nemausus crocodile series and certain forms of pottery, can be dated to the so-called “Oberaden horizon”, suggesting a link with Drusus’ campaigns. Other material, such as terra sigillata from Ateius’ workshops, belongs to the later phase of campaigning, which (as we shall see) is connected with the fortress at Haltern. And a denarius of 41 BC reminds us how long coins could remain in circulation. As we have seen, armies were also moving from Mainz, up the valleys of the Main and Wetter through the lands of the Chatti. However, it is clear that their journey continued onwards, because a 21ha marching camp has been discovered at Dorlar, some 30km northwest of Rödgen, at the headwaters of the Lahne. Again, no traces of rampart were found, but the ditch was some 3m wide by 2.3m deep. Pottery finds suggested a similar date to Haltern, but other earlier camps perhaps await discovery in the same general area. The Lahn: Waldgirmes The camp at Dorlar lies only 2km from Waldgirmes, where a 7.7ha permanent base was sited on high ground above the River Lahn. During the 1990s, a length of the trapezoidal perimeter was excavated and found to comprise the usual 3m wide rampart, fronted Augustan coinage When Augustus became emperor, he assumed sole responsibility for issuing coins across the Empire, and authorised mints at Rome, Lugdunum (Lyon) and Nemausus (Nîmes). The coin types depicted his own profile on the obverse (the “heads” side), sometimes with his trusted deputy, Marcus Agrippa. The reverse (the “tails” side) depicted one of several symbolic images; for example, the crocodile and palm tree, recalling the capture of Egypt in 30 BC, or the Lugdunum altar, dedicated in 10 BC. Legionaries were paid the sum of 75 silver denarii three times per year. In practice, much of this would have been issued in bronze coins (sometimes called aes coinage), which were more easily spent. The choice was between the sestertius, a very large, heavy, yellow brass coin worth 1/4 denarius, or the as, a slightly smaller red copper coin worth 1/4 sestertius; in between lay the dupondius, matching the as in size but the sestertius in colour. Each legionary probably carried a variety of all these coins. However, a peculiar phenomenon occurred in the Augustan military bases in Germany, where dupondii seem regularly to have been cut in half to create two semi-circular asses. This is thought to have been caused by Augustus’ re-valuation of the Lugdunum and Nemausus asses, which were rather on the heavy side, as dupondii. Soldiers must have found that the smallest coin available to them had suddenly doubled in value, so they took the practical step of halving them to create small change! Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 23 23 17-05-2009 17:50:05 © Andrew Brozyna, ajbdesign.com Fortifications Roman fortifications in the Haltern area by a double ditch, the inner of which was some 3.2m wide by 2.3m deep, with an outer ditch of slighter proportions; soil erosion had perhaps reduced the ditch dimensions somewhat. The east gateway was investigated, and the gate structure was found to conform to the usual massive Augustan pattern. Besides traces of ovens, pits and timber buildings, there was evidence of manufacturing, such as the discovery of a small pit containing an anvil. So far, none of these elements would be out of place in an Augustan military base. Some weapons finds were made, also, including the tip of a pilum, a bronze hinged buckle, and an iron spearhead. The terra sigillata matches the ceramics from Haltern, and the coin list lacks the Nemausus issues that define the “Oberaden horizon”. Finally, a dendrochronological date from some well timbers fixed its construction in the year 4 BC. Excavations have continued at the site, and their interpretation has become steadily more complex. Fragments of a gilded bronze equestrian statue raised suspicions that Waldgirmes was no ordinary military base, but archaeologists have now hailed it as the first town in Germany. The stone foundations of the latest building phase, including the idiosyncratically designed principia, certainly suggest that the Romans envisaged a degree of permanence. But whether we accept that the base had taken on 24 civic pretensions, Waldgirmes clearly has more secrets to reveal. The Lippe: Haltern And so we come to the key site of Haltern, some 54km distant from Vetera on the Rhine. Besides a large (34.5ha) marching camp, which clearly came first, several military installations were erected here (see diagram): from west to east, these are the fort on the Annaberg, the Wiegel stores depot, the two-phase fortress on the Silverberg, and the Hofestatt fort, sometimes (like Beckinghausen) incorrectly called a “waterfront fort” (Uferkastell); at some point, a metalled road was laid out, apparently linking the stores depot with the Annaberg fort, and there was time for a cemetery to grow up along its northern side. Part of a second marching camp of at least 20ha was excavated some way to the northeast. All of the material remains appear to be chronologically later than the Oberaden assemblage, so the start of occupation at the site is normally associated with the involvement of Tiberius in Germany from AD 4, but it could belong as early as AD 1, with Marcus Vinicius’ “immense war” against the Germans (immensum bellum: Velleius Paterculus 2.104.2). Unfortunately, excavations began here, specifically in the Annaberg fort, in 1905, when available techniques were rather primitive; in addition, much of the excavated material is now lost, preventing any attempt at reassessment. Equally, interpretation of the Wiegel stores depot, with its complexity of multiple palisades, ditches and pits, was compromised by the excavator’s belief that it was a riverside ‘berth’ with slipways for warships. It is now clear that the Lippe has wandered back and forth across the valley in the intervening centuries and, far from opening directly onto the riverbank, the Wiegel site probably stood some way back, similar to the earlier situation at Beckinghausen. Erosion has also complicated our picture of the Hofestatt fort, which was clearly a three- or four-phase fortification, again standing back from the riverside, but much of it has been washed away. The so-called “main camp” (Hauptlager) is the best-known of the four installations, and presents the most complete plan of an Augustan fortress, with its rows of barrack blocks interspersed with officers’ houses, a large workshop area, and even a hospital building. The principia, a fraction of the size of the Oberaden headquarters but normal by later standards, betrayed two phases of building, in keeping with the fortress itself, which was extended at some stage. Behind it lay the commander’s house (praetorium), with another beside it, hinting that command was somehow shared here. Equally, the multiplicity of atrium houses, surely intended for junior officers but far exceeding the normal requirements of a legionary fortress, suggests that Haltern had a more important role to play. Years of excavations brought thousands of finds to light: pilum heads, spearheads, trilobate arrowheads, arrowheads for catapults, and a fine example of a sword and a dagger. More interesting were the lead bar scratched with the legend L(egio) XIX and the lead stopper from a medicine bottle, which indicated that it contained herba Britannica, the cure for scurvy (AE 1929, 102). The coins and pottery found on the site are uniformly later than the “Oberaden horizon”; although the presumed abandonment of Haltern in AD 9 has been used to date the terra sigillata, thus creating a circular argument, none of the coins were minted after the first decade AD. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 24 17-05-2009 17:50:06 Fortifications The Lippe: Anreppen © Karwansaray BV. Another Augustan base of roughly the same date is known, some 140km further along the Lippe, at Anreppen in the town of Delbrück near Paderborn. The irregular oval perimeter, enclosing an area of 23ha, displayed a peculiar semicircular re-entrant on the north side, where it looked onto the river. Like the other Augustan bases, it was defended by a 3m wide earth-and-timber rampart, fronted by a 6.5m wide, 2.3m deep ditch; the south side was further protected by a second ditch of slighter proportions. Only the northeast and southeast gates could be investigated, and both displayed the now familiar massive timber gate structures. Alongside each one, a long, narrow building positioned behind the rampart presumably accommodated the night watch during inclement weather; the same feature was earlier noticed at Oberaden, too. Much of the interior was unavailable for excavation. The principia in particular was not revealed, but the commander was housed in an impressive 70m wide praetorium, and a truly enormous granary, with a capacity exceeding the three Rödgen granaries combined, stood just inside the southeastern gate, hinting at a wider supply role for the fortress. Several barrack blocks were also located, with the centurions’ houses oddly positioned at the far end, rather than beside the via sagularis, as found elsewhere. All of this serves to remind us that Augustan military bases came in various shapes and sizes, each with its own individuality. The preserved timbers of a well gave a dendrochronological date of AD 5, and the coins and pottery, including dishes from the Ateius workshop, point broadly to occupation in the first decade AD. Indeed, Anreppen’s position at the headwaters of the Lippe has been linked with the events of AD 4, with interesting implications for the inhabitant of the large praetorium. “The defence of the empire brought Tiberius at the beginning of spring (AD 5) back to Germany, where the general had on his departure built his winter camp at the source of the river Lupia, in the very heart of the country.” Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.105.3 The Weser: Hedemünden Perhaps the most exciting discovery of recent years was made near Göttingen at Hedemünden, 200km east of the Rhine, where an Augustan military site has been found. A two-phase ovalshaped fort, enlarged from 3.2ha to 4.5ha, was sited on a wooded hill above the River Werra, a tributary of the Weser. The standard 3m wide rampart was fronted by a ditch 3.5m wide by 1.5m deep. No north gate was observed, but the fort appears to have had an extra east gate, opening onto a large flat area occupied by a 12ha marching camp. A shovel and a beautiful example of the legionary’s pickaxe (dolabra) were discovered buried in the rampart on the east side of the fort, where they had perhaps fallen during the second phase refurbishment. Another three dolabrae have come to light, along with other tools including two adze-hammers. The many metal finds, largely from an area outside the west rampart, included a pilum-head, two daggers, various cataBronze capricorn, possibly formerly part of a standard – the capricorn was the legionary symbol of a number of legions – found in the area of Bentheim, Germany. Copy, now in the Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. pult arrowheads, and 800 hobnails. The excavator also found a phallus-shaped amulet, almost identical to finds from Holsterhausen and Haltern. The interior has not yet been excavated, but magnetometer survey indicated the stone foundations of buildings and the presence of ovens and pits. Curiously, besides a silver coin of 80 BC, the coin list is heavily weighted by the Nemausus issues typical of the ‘Oberaden horizon’. This suggests that Drusus’ campaigns ranged far wider than previously thought. Clearly, we can expect the eventual discovery of more Augustan military installations, perhaps along the Weser, or linking Hedemünden back to the Rhine, either along the Lippe to Vetera or back to Mainz via Rödgen and Waldgirmes. n Duncan B Campbell studied Roman military archaeology for his PhD, and is a part-time lecturer at Glasgow University’s Department of Adult & Continuing Education. His latest book, Roman Auxiliary Forts, is a companion volume to Roman Legionary Fortresses. Further reading - D. B. Campbell, Roman Legionary Fortresses, 27 BC-AD 378. Oxford 2006 - W. Ebel-Zepezauer, “Die augusteischen Marschlager in Dorsten-Holsterhausen”, in: Germania 81 (2003), pp. 539-555 - K. Grote, “Das Römerlager im Werratal bei Hedemünden (Ldkr. Göttingen)”, in: Germania 84 (2006), pp. 27-59 - J. S. Kühlborn (ed.), Germania pacavi: Germanien habe ich befriedet. Münster 1995 - S. von Schnurbein & H.-J. Köhler, “Dorlar. Ein augusteisches Römerlager im Lahntal”, in: Germania 72 (1994), pp. 193-703 - S. von Schnurbein, “Neue Grabungen in Haltern, Oberaden und Anreppen”, in P. Freeman et al. (eds.), Limes XVIII: Proceedings of the XVIIIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Oxford 2002, pp. 527-533 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 25 25 17-05-2009 17:50:07 The generals Road to Destiny Arminius and Varus before AD 9 Arminius and Varus will forever be known as the great antagonists of the Teutoburger Forest. Less famous are the roads both men traveled prior to AD 9. Sidney Dean © Stéphane Lagrange Arminius The vexillum is inspired by a quote from Cassius Dio, who states that this standard bore the name of the commander and the units it represented in red lettering. The abbreviated notation here reads in full: “The army of Germania, legions XVII, XVIII and XIX of the propraetorian legate Publius Quinctilius Varus.” The phalerae on his chest were derived from a sample in the British museum in London, made from blue glass on a silver disc representing members of the imperial family. 26 Everything known about Arminius comes from Roman sources, especially Tacitus and Velleius Paterculus. According to Tacitus (Annals 2.88) he died at age 37 after leading his people for twelve years. The Roman historian, writing around 90 AD, is not precise regarding the year in which Arminius was assassinated. However, his statement establishes a definite framework for the Cheruscan’s vital statistics. On the one hand Tacitus clearly states that Arminius was still alive at some point in 19 AD. On the other hand Tacitus cannot have begun calculating Arminius’ rule any later than 9 AD. Taken together this places his death sometime between 19 and 21 AD, and his birth 37 years earlier, between late 19 BC and 16 BC. In contrast to his vital statistics, his true name remains a mystery. All Roman sources refer to Varus’ adversary by the Latin-form name Arminius. Was this a Latinization of his Germanic given name? One possibility here would by “Irmin” or “Ermin” (meaning “mighty” or “exalted”), the name or by-name of a god worshiped in ancient northern Germany. Another theory is that he was adopted into a Roman family clan, the Gens Arminia, but there is no substantiating evidence. One interesting theory is that Arminius is taken from “Armenium”, a mineral with a vivid shade of Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 26 17-05-2009 17:50:08 The generals © Karwansaray BV light blue or blue-green – presumably a reference to his eyes. This theory builds on the fact that the Romans named Arminius’ younger brother Flavius, meaning “blonde”. The only certainty about his given name is that the modern German appellation of “Hermann”, made popular by Martin Luther, is definitely false. ‘Prince’ of the Cherusci According to Velleius Paterculus (Roman History 2.118), Arminius’ father was named Segimer. Velleius refers to Segimer as “a prince of that nation” without indicating a special status among the various tribal leaders. On the other hand Tacitus (Annals 11.17) writes that Arminius was a member of the Cherusci stirps regia or “royal family”. In fact the Cherusci, like most other Germanic tribes of the era, did not have one supreme monarch. Rather, the territory of the Cherusci was divided into various districts, each with its own chieftain (Roman chroniclers frequently use the term princeps, the title used by Augustus). Even within their own districts these chieftains were not allpowerful but had to consult their aristocratic peers as well as the Thing or assembly of free men to secure consensus on vital issues (Tacitus, Germania 7.11). The council of chieftains met on issues effecting the entire Cherusci people. Only during emergencies – for example to provide unified leadership during war – did they elect temporary kings. Tacitus’ use of the term stirps regia indicates that Arminius’ clan had a special position among the Cherusci aristocracy, leading to speculation by some scholars that in an earlier decade this family had indeed been supreme within the tribe. In any case Segimer seems to have been recognized as war leader by the other Cherusci ‘princes’. In this function Segimer will have led the Cherusci in years of resistance against Rome. Beginning in 12 BC, Emperor Augustus’ adopted son Drusus led annual Roman expeditions across the Rhine in an attempt to subdue the northern Germanic tribes. That same year the Cherusci, the Suebi, and the Sigambri swore a blood oath to jointly resist – sealing the pact by sacrificing 20 captured Roman officers. Arminius No known portrait of Arminius exists, apart from a very doubtful ‘Germanic’ bust in the Capitoline museums in Rome. Generic barbarians are often seen in Roman art however. Among those, Germans are most easily recognized by their ‘Suebian knot’, as is clearly visible on this theatrical mask. Now in the British museum, London. was between seven and ten years of age when his father Segimer, representing the Cherusci, sealed this blood oath. Perhaps the boy was even present to witness the human sacrifice. In any case his youth was marked by years of intermittent bloody conflict against Rome. As the son of a tribal leader, he was trained not only to fight and to ride, but also to plan military operations and to lead the youth of the tribe in battle. He most likely gained combat and leadership experience as a teenager during the immensum bellum or “great war” initiated in 1 AD as a concerted offensive by various tribes against the Roman presence east of the Rhine. But in the end, the legions asserted themselves. Drusus’ brother Tiberius, combining a show of force with a diplomatic offensive, convinced the Cherusci to become Roman foederati (allies) in 4 AD. As was customary, the leading families of the Cherusci were required to present their sons as hostages to ensure compliance with the pact. The treaty also included an obligation to provide military auxiliaries for Rome. In Roman arms Unlike his younger brother and other young hostages provided by foederati tribes, Arminius was too mature to be taken to Rome for education and indoctrination. As Segimer’s oldest son, he was therefore appointed commander of the Cherusci auxiliary contingent. This contingent was stationed at one of the Roman bases under Tiberius’ command in Germania. There Arminius could still be indoctrinated and observed, and he would be vulnerable should Segimer break the treaty. During this time he received formal training in Roman strategy and tactics, in order to effectively lead his contingent in cohesion with the legion units. Given the fact that Arminius had been raised to hate the Romans it is more than likely that he spent this time observing their organization and tactics, consciously learning their weaknesses and strengths while ingratiating himself. He was said to be charming, and won the confidence of many Roman officers. The records concerning Arminius’ military service are again sparse. We do not know the exAncient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 27 27 17-05-2009 17:50:10 The generals © Karwansaray BV act dates of his service with Rome, nor the campaigns he participated in, but much can be inferred from the writings of Velleius and Tacitus. Velleius is a particularly important source. He served as Tiberius’ cavalry commander at the same time as Arminius served, and knew the young German by sight. Indeed, he may have been Arminius’ immediate superior. He describes the Cheruscan as “a young man of noble birth, brave in action and alert in mind, possessing an intelligence quite beyond the ordinary barbarian; (...) and he showed in his countenance and in his eyes the fire of the mind within.” (Roman History 2.118). Velleius also states specifically that Arminius “had been associated with us constantly on private campaigns, and had even attained the dignity of equestrian rank.” The fact that Arminius was granted Roman citizenship and accepted into the ordo equester (i.e. elevated to the status of Roman knight) has been interpreted in two ways. Some scholars believe these honors were automatically accorded Arminius in light of his position in the Cherusci aristocracy – and simultaneously as an attempt to coopt his loyalty. Others believe that at least the knighthood was a reward for meritorious service. The fact that Velleius emphasizes Arminius’ elevation to the “dignity of equestrian rank” indicates that it was not, as a rule, awarded auto- Varus’ portrait on a coin struck during his governorship of the province of Africa (modern Tunisia). Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. 28 matically, but had to be earned. In this context it is important to note that there were two different classes of auxiliary forces: “regular” auxiliaries composed of well trained professional soldiers drawn from client peoples and often led by Roman officers (knights, if they were cavalry units), and tribal levies raised for contingency service. There is nearly unanimous agreement that Arminius originally led such a tribal levy in Tiberius’ campaigns against other Germanic tribes in the 4-6 AD timeframe. This would include service as scouts and skirmishers during Tiberius’ 5 AD campaign against the Langobardi and his campaign to the Elbe River. Presumably they also formed part of the army Tiberius planned to lead in 6 AD into Bohemia, where Marcomanni king Marbod had established a powerful kingdom. At the last minute Tiberius had to divert his forces to the Balkans to deal with the Pannonian Uprising. This begs the question: did Arminius and his levy accompany Tiberius, or did they return to Germany for good in 6 AD? Inextricably tied to this question is: when did Arminius assume leadership of his clan and his tribe? There are, again, various theories. One school of thought believes Arminius and his force remained in Germany to support Governor Sentius Saturninus (as of 7 AD: P. Quintilius Varus) in securing the Rhine lest the Germanic tribes rise up, or that they were even dismissed from service and allowed to return to their tribe. The fact that Varus implicitly trusted Arminius could indicate familiarity developed over a two-year period of acquaintance. Other scholars are convinced that Arminius either accompanied Tiberius to Pannonia in 6 AD, or joined him there in 7 AD when Saturninus was dispatched from the Rhine to reinforce Tiberius with regular legions and auxiliaries. If this theory is correct Arminius, as a knight and a proven leader, was probably promoted to lead a “regular” auxiliary unit, most likely a German cavalry ala of 500 or 1,000 men. Much speaks for this theory. Tiberius needed 15 legions and the equivalent number of auxiliaries to suppress the Pannonian Revolt during three years of intense warfare. And Rome’s policy was to deploy auxiliary forces away from home whenever possible to minimize the likelihood they would switch sides. Sending Arminius and as many Germanic auxiliaries as possible to the Balkans would make military sense. Proponents of this theory interpret Velleius’ statement regarding Arminius’ “constant association” during campaigns to mean Arminius served with Tiberius and Velleius in the Pannonian expedition, the last major campaign before the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. Obviously he cannot have stayed with Tiberius for the duration of the war, which ended in September of 9 AD, only days before the battle in Germany. In light of Tacitus’ statement that Arminius ruled the Cherusci for 12 years, he must have succeeded Segimer sometime between 7 and 9 AD. He may have been released from military service after the major Roman victory at the Bathinus River in August, 8 AD, which significantly reduced the enemy forces. This would have given him a year in which to plan his own uprising and to ingratiate himself with Varus. Alternately, he may have been released at any earlier time during the campaign upon word of his father’s illness or death. Believing Arminius a loyal Roman citizen and soldier, Tiberius would have wanted to guarantee him a smooth transition as tribal leader. Publius Quinctilius Varus In contrast to Arminius, the vital statistics of Publius Quinctilius Varus are precisely known. He was born in 46 BC into an old patrician family. His father, senator Sextus Quinctilius Varus, actively supported Pompey against Julius Caesar, and committed suicide after Marc Antony and Octavian defeated the last republican forces at Philippi (42 BC). The younger Varus thus grew up under difficult circumstances – the family had enjoyed more prestige than wealth to begin with, and lost what remained of both after Sextus’ disgrace and death. As a youth P. Quinctilius Varus began displaying the survival trait that would Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 28 17-05-2009 17:50:11 mark his adult life – subservience to those who could benefit or harm him, arrogance to those he was in a position to benefit or harm. He ingratiated himself with Octavian, was appointed quaestor in 23 BC (below the usual minimum age), and accompanied Octavian (by that time Emperor Augustus) on his three-year tour of the eastern provinces (22-19 BC). As a favorite of the emperor, Varus quickly rose to honors, power, and consequentially wealth. He went through the cursus honorum – a series of increasingly responsible public offices intended to prepare the nation’s future leaders – becoming in turn aedile, praetor, propraetor (probably commanding a legion), and finally, in 13 BC, co-consul of Augustus’ stepson Tiberius, with whom he cultivated a close friendship. That same year both Varus and Tiberius married daughters of the emperor’s close ally, General Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, cementing Varus’ ties to the center of power. When Agrippa died in 12 BC Varus held the funeral oration. The ‘War of Varus’ In 7 BC Varus was appointed governor of the province of Africa for one year. This was a very prestigious assignment, which implied that Varus had not only the Emperor’s trust but also that of the Senate, which had direct authority over Africa. Having proven himself an efficient steward over this vital breadbasket of the empire, Varus was subsequently appointed as governor of Syria – where he succeeded none other than Gaius Sentius Saturninus, whose son he would later succeed as governor of Germania. In contrast to Africa, Varus’ new area of responsibility was under direct authority of the emperor. Syria and the surrounding client states were Rome’s strategic buffer in the East, securing the empire from their powerful Iranian rivals, the Parthians. Upon arriving at his new post in Antioch, Varus took command of three legions, or one sixth of the standing Roman army. The appointment as governor demonstrated Augustus’ high regard for his capabilities – a trust that would prove to be well placed. While Velleius (Roman History 2.117) later accused Varus of abusing his position to line his own pockets, he was © Karwansaray BV The generals The most common form for Germans in Roman art: as a prisoner. What seems to be a ‘Suebian knot’, on the other side of his head, probably marks this bronze statuette out as a Germanic warrior as well. Now in the National Archaeology Museum of Saint-Germain-En-Laye, France. in fact an efficient guardian of Roman interests. Among his other duties, Varus was also responsible for Roman relations with (and control over) the neighboring client kingdom of Judea. When Judea erupted in a major, multipartite civil war in 4 BC following the death of the pro-Roman King Herod, it was up to Varus to restore order in this strategically vital region. At the first sign of unrest he dispatched one legion to secure Jerusalem and the surrounding territory. This occupation of the holy city only fanned the flames of religious and nationalist resentment against Rome and Herod’s heir-designate Archeleaus. When four separate full-blown insurgencies erupted simultaneously throughout Judea, Varus personally led two additional legions and a large force of auxiliaries from neighboring client kingdoms into Judea. All in all, Varus commanded a good 20,000 men, not including his legion besieged at Jerusalem. Moving from north to south he crushed the insurgencies in turn. His campaign was systematic, efficient – and brutal. He personally ordered the complete destruction of two sizeable towns. He ordered 2,000 captured rebels crucified. Tens of thousands of Jews – including many noncombatants, women and children – were sold into slavery. This so-called ‘War of Varus’ was the most dramatic episode of his governorship, and indeed of his career until the disastrous battle of 9 AD. Varus is thought to have returned to Rome in 3 BC. Following the death of his first wife, Vipsania Marcella (with whom he may have had a son), Varus married Claudia Pulchra, a niece of Augustus, with whom he had one son. Little is known of his political activities after leaving Syria until his posting to Germania in 7 AD to replace Saturninus, who was sent to Pannonia to reinforce Tiberius. It is a safe assumption that Varus’ actions in Judea contributed to his later appointment as governor of Rome’s frontier province in the north. n Further reading: - H. Ritter Schaumburg, Der Cherusker: Arminius im Kampf mit der römischen Weltmacht. Munich and Berlin 1988. Ancient sources: Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Tacitus, Annals, both available online at www.gutenberg.org and C. Velleius Paterculus, The Roman History available on Lacus Curtius (http://penelope.uchicago.edu/ Thayer/E/home.html). Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 29 29 17-05-2009 17:50:11 The opposing armies Augustan legionaries Defining features of the Roman army Unlike the great wars of the Late Republic, the conquests and campaigns of the age of Augustus are poorly documented. However, the surviving literary evidence (histories, geographical writings and poetry) and epigraphic sources (epitaphs and dedicatory inscriptions) do provide glimpses of the wars and the legionaries who fought in them. By Ross Cowan The obstinate pilum The pilum was the defining weapon of the Roman legionary (Livy 9.19.7). It was a dual-purpose javelin, suitable for thrusting as well as throwing (cf. Appian, Civil Wars 2.76, Plutarch, Antony 45.3). As a close range missile it was often deadly, designed to punch through shield and armour, and on through flesh and bone (Livy 10.39.12). The legionaries of the age of Augustus carried this distinctive Italian weapon far and wide: it was used in anger from Spain in the West to Arabia in the East, and from Germany in the North and to Egypt in the South. This was the epoch in which a panegyrist of one of Augustus’ generals could confidently envisage “the obstinate pilum breaking down all before it” (Anon., Panegyric of Messalla = [Tibullus] 3.7.90). Its deadliness is demonstrated by great victories like the battle of Negrana in Arabia Felix (23 BC), where 10,000 of the enemy were slaughtered for the cost of only two Roman lives (Strabo, Geography 16.4.24). Even when the pilum did not break down the enemies of Rome and her first Emperor, as at the disastrous battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9, the legionary javelin was the weapon of subsequent revenge (cf. Tacitus, Annals 2.14). It took skill, a strong arm and iron nerve to wield the pilum in the chaos and confusion of battle; it took great courage to follow the path of the thrown pilum into the ranks of the 30 enemy and to barge and batter with scutum, and to hack and stab with gladius. But that is what happened countless times during the reign of Augustus and the great expansion of the Roman Empire. It happened because brave and determined men hurled the obstinate pilum with the same determination and courage that defined their forefathers, the legionaries of Julius Caesar, Sulla and Marius. Valiant centurions The most famous and impressive monument of the Varian Disaster is the cenotaph of Marcus Caelius, a senior centurion of the first cohort of the Eighteenth Legion (ILS 2244). He was killed at the age of 53, probably having spent more than 30 years in the army. The inscription on the stone reveals nothing about Caeilius’ career in the army except for the post he held at the time of his death, but the accompanying sculptural relief of the centurion gives ample evidence of his personal bravery. Caelius is depicted with torques (heavy necklets, but slung on either side of his neck, rather than worn around it), embossed phalerae (‘medallions’) worn on a harness over his cuirass, and armillae (bracelets) on his wrists. All were prizes for bravery in battle. The Roman centurion was traditionally conspicuous for his courage; the Caesarian centurions Baculus, Pullo, Vorenus, Scaeva and Crastinus spring to mind as exemplars of the type (see Ancient Warfare I.2). Caelius’ dona militaria (military decorations) show him to be a worthy successor to these famous warriors. What is more, Caelius’ monument depicts another decoration, one awarded for selfless courage. On his head is a corona civica, the ‘civic crown’ woven from the leafy twigs of the oak tree and presented to a soldier who had saved the life of a comrade in battle. The cenotaph was set up by Caelius’ brother, Publius, conceivably also a legionary and perhaps therefore of senior rank like his brother. It would have taken considerable wealth to pay for the impressive stone monument but centurions, especially primi ordines of the first cohort were not short of cash. Centurions of cohorts II-X probably received fifteen times the basic legionary salary, primi ordines thirty times, and the primus pilus sixty times as much! Caelius would have left money with his family and instructions in his will for the contruction of his memorial in the This legionary is equipped with a bronze helmet with brass browguard, the original of which was found in Haltern; a chain mail with shoulder doubling and fastening hooks after numerous finds from Augustan sites, and a shield based on the find from Kasr-ElHarit, which concurs with pictorial evidence from the period. The shield has a boss similar to finds from Dangstetten and Haltern, and a gilded silver sheetlightning decoration as found in Kalkriese. Under his chainmail he wears a subarmalis with madder-dyed herringbone woolen pteryges over a white tunic. His pattern-welded sword, scabbard and caligae are based on finds from Mainz. The belt and belt plates are based on finds from Dangstetten, Haltern and Augsburg-Oberhausen. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 30 17-05-2009 17:50:12 © Johnny Shumate The opposing armies Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 31 31 17-05-2009 17:50:14 © Karwansaray BV The opposing armies Many Augustan era pugiones, daggers, are highly decorated as is clearly visible on this example from Xanten. Now in the Regionalmuseum, Xanten, Germany. event of his death, and it would have been Publius who instructed the stonemason on how to portray his brother. What we see, the powerfully built individual with a hard flat expression, should be a reliable representation of the man. It is unfortunate that we do not know the circumstances in which Caelius won his dona militaria, especially the civic crown (see Tactius, Annals 3.21 and Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 5.6.14, for the circumstances leading to the eventual award of such a crown in AD 20). The corona aurea, or gold crown, was another award for conspicuous gallantry, and it is to be regretted that we have no idea of where, when or how Titus Statius Marrax, whose last post in the army was as primus pilus of legio XIII Gemina, won his notable tally of five gold crowns and the other decorations for bravery which are listed with pride on his gravestone (ILS 2638). The gravestone of Gaius Allius Oriens, most 32 probably a contemporary of Caelius and Marrax and, coincidently, also a centurion of the Thirteenth, shows three gold crowns – the prizes of three brave deeds (CIL XIII 5206). Once again, we can only guess at how they were won, but considering the known movements of the legion during the reign of Augustus, it is likely Oriens won his decorations in the campaigns to conquer the Balkans or the punitive operations into Germany after AD 9. Lucius Blattius Vetus, a centurion of legio IV Macedonica, may have won his dona militaria in Spain (AE 1893, 119; see Dio 54.11.2-5 for the hard fighting there), while Vergilius Gallus Lusius may have been awarded one of his gold crowns while primus pilus of legio XI (later Claudia) during the Illyrian Revolt of AD 6-9 (ILS 2690). The bravery of Augustan centurions and their habit of leading from the front is reflected in their high battle casualties (cf. Velleius Paterculus 2.112.6), but unlike the centurions of the Late Republic, we possess few literary accounts of individual officers in action. We do know of Cornidius, a centurion who fought in the conquest of Moesia in 29-28 BC: No little terror was inspired in the barbarians by the centurion Cornidius, a man of rather barbarous stupidity, which, however, was not without effect on men of similar character. By carrying on the top of his helmet a pan of coals which were fanned by the movement of his body, he scattered flames from his head and had the appearance of being on fire. Florus, Epitome 2.16 One wonders if Cornidius was decorated for his somewhat bizarre antics on the battlefield. It is possible that the centurion’s legion was IV Scythica, probably awarded its title for service against the ‘Scythians’, a cover-all term for various Danubian peoples, in the Moesian War. It should also be noted here that Cornidius’ general was Marcus Licinius Crassus, grandson of the Crassus who led his army to disaster at Carrhae in 53 BC. The younger Crassus was a far more competent general, and during the The legions’ helpers As well as reorganizing the legions, Augustus formalised allied forces from beyond the Roman frontiers, non-citizen formations from within the Empire, mercenary contingents, and even exiles, like the retinues of dissident Parthian nobles, into permanent infantry cohorts and cavalry alae (“wings” – the title referred originally to allied Italian formations of infantry and cavalry). Some of the cohorts, designated equitatae, also had a cavalry component. Unlike its middle Republican predecessor, the late Republican legion did not have its own cavalry or light troops. Julius Caesar sometimes deployed lightly equipped legionaries (expediti) but he relied on Germans and Gauls for cavalry. Some of these new auxilia (“helpers”, “supporters”) regiments provided the Imperial Roman army with specialists in which the legions were deficient: various types of cavalry, archers (foot and mounted) and light infantry. However, a substantial proportion of infantry cohorts fought as heavy infantry. The number of auxiliaries in Augustus’ army is uncertain; they presumably matched, and possibly outnumbered the legionaries; roughly 150,000 is a reasonable estimate. A typical cohort or ala probably contained some 500 soldiers, who, after a service period of 25 years or more, would be rewarded with Roman citizenship. Some auxiliaries, such as the Batavi, proved themselves invaluable and loyal (until AD 69, at least). Others, such as those recruited from the Pannonians and other Illyrian peoples, once trained and equipped in the Roman manner but still commanded by their own nobles, revolted and threatened to prise back from Augustus his central European and Balkan conquests (AD 6-9). Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 32 17-05-2009 17:50:15 The opposing armies tary governor of a sector of the Black Sea coast, would support his appeals to return to Rome. Yet Ovid’s description of Vestalis in combat does have the ring of authenticity, reminiscent, for example, of the actions of the Caesarian primus pilus Baculus (Caesar, Gallic War 2.2, 3.5, 6.38): Vestalis acts as a primus pilus should, leading from the front and inspiring by personal example. Finally, the spirit of the Augustan centurion is encapsulated by the redoubtable Mevius: Mevius, a centurion of Augustus the god, had often fought with distinction in the Antonian War [the Actium campaign, 31 BC or Egyptian War, 30 BC], but was surprised by an enemy ambush and surrounded and taken to Antony in Alexandria. Asked what should be done with him, he replied “Have me killed, for neither benefit of life nor infliction of death can make me cease to be Caesar’s [i.e. Octavian- © Stéphane Lagrange course of the Moesian War he slew Deldo, king of the Bastarnae, in single combat and claimed the right to dedicate the spolia opima (‘the greatest spoils’ being those stripped from an enemy king) to the god Jupiter Feretrius. He would have been the fourth Roman to do so, following in the glorious path of Romulus, Cornelius Cossus and Claudius Marcellus. However, Octavian could not tolerate this. He had only recently defeated Mark Antony and reunified the Roman world. He was promoting himself as the new Romulus and the ancient magisterial powers were being concentrated in his person. He was effectively emperor – something that was confirmed in January 27 BC when he became Augustus. Generals fought under his auspices: he was the supreme commander and their victories were his. So when Crassus returned to Rome early in 27 BC, he was voted a justly deserved triumph, but Augustus denied him the even greater glory of dedicating the spolia opima. The ambitious and energetic conqueror of Moesia then disappears from Roman history. Cornidius would have been a proud participant in the colourful and dramatic triumphal procession through Rome; his helmet was probably among the curiosities displayed to the masses. Florus’ notice of Cornidius is brief and mocking. Ovid, exiled by Augustus to the Danube delta, preserves a more glorious and laudatory image of a centurion in action. In AD 12, Julius Vestalis, son of an Alpine prince, was primus pilus of one of the legions based in Moesia, and he fought in the recapture of Aegisos from the Getae. Vestalis is described in armour bristling with arrows and a battered scutum, ignoring his wounds and continuing to advance, and clambering over the bodies of the warriors he killed. “It is difficult to recount all your warlike actions, how many you killed or how they died.” Ovid declares that Vestalis’ bravery inspired his legionaries and, like their centurion, they ignored the pain of their wounds to inflict worse punishment on the Getae (Black Sea Letters 4.7). Ovid may have exaggerated Vestalis’ role in the victory. The poet was, after all, in exile and probably hoped that Vestalis, subsequently promoted to the rank of mili- Marcus Caelius brought to life, the primus pilus is wearing his full set of decorations, a highly ornate helmet and similarly adorned greaves. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 33 33 17-05-2009 17:50:16 The original of the helmet portrayed in the reconstruction depicted on page 31, a Robinson-type Coolus E helmet found at Haltern. Augustus] soldier or begin to be yours.” But the more resolutely he despised life, the more easily he obtained it, for in tribute to his valour (virtus) Antony left him unharmed. Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings 3.8.8 (compare Plutarch, Antony 64.2 for an Antonian centurion at Actium) Career Soldiers Many centurions began their careers as lowly milites gregarii (common soldiers) and rose slowly through the ranks. Such a career is inscribed on the gravestone of a centurion of legio XIV Gemina (ILS 2649). The stone is broken and part of the inscription is missing, so we do not know the name of the centurion or where he came from (it can be assumed he was an Italian), and the numerals and titles of all the legions he served in prior to XIV Gemina are lost. However, enough survives to tell us that he served as an ordinary legionary for 16 years, and as veteran sub vexillo –‘under the banner’ of the veterans’ corps – for a further four years. This was the service requirement laid down by Augustus in 13 BC and remained in effect until AD 5/6, after which new recruits had to serve 20 years plus a further five years sub 34 vexillo (Dio 54.25.5-6 and 55.23.1, failing was appointed curator because he had to mention that extra service sub held appropriately senior posts in his vexillo was required). Eventuold century, probably tesserarius (officer ally, of course, all legionaries of the watchword), optio (centurion’s served for 25 or 26 years deputy) or signifer, or had served on the and only became veterstaff of a tribune or legate. ans on discharge (misFollowing his four years under the sio). As discharges banner, our man chose to remain in the were made every army as an evocatus, a veteran ‘recalled’ two years, half of or invited to remain in service with a those legionarstatus approaching that of a centuies who survived rion (see Dio 55.24.8). As experienced to complete their men, evocati were rather useful, being service spent an extra employed to command small detachyear in the legions. ments or carry out special assignments, Our man held the but our man was not content with that rank of curator veteranorank and after three years he secured rum, probably concerned with an actual centurion’s post. Thus it took the administration of the corps of him 23 years to progress to the rank of veterans attached to his legion. Some centurion; in fact, he may not have atscholars have suggested that the curatained his promotion until the reign of tor was in command of the veterans, Tiberius (AD 14-37). He remained in serbut that is most improbable. We know vice for another 23 years, probably until that in AD 20, the veterans serving sub the time of his death. His final centurial vexillo of legio III Augusta numbered post was as centurio princeps, perhaps around 500 (Tacitus, Annals 3.21), but in the first cohort, of legio XIV Gemina. the curator was clearly lower in rank What remains of his gravestone serves than a centurion (as indicated by the also as a reminder of his bravery: it is subsequent career of this soldier), and decorated with the torques and phalthe legionary centurion commanded erae he won in 46 years of soldiering. no more than a century of 80 or so men; Professionals like this man formed the the Augustan legions did not have enbackbone of the legions, but they were larged first cohorts with five doublethe terror of new recruits and shirkers size centuries (as indicated by Tacitus, because they knew all the tricks and Annals 1.32). It seems that the veterans were actually commanded by prefects of equestrian rank (e.g. AE 1926, 82 of legio XII Fulminata). Publius Tutilius, another Augustan curator veteranorum, is known to have held the ranks of signifer (standard bearer) and aquilifer (eagle bearer) in a legio V, perhaps Alaudae, prior to serving sub vexillo (ILS 2338). The duties associated with those posts were as much administrative as they were tactical (Vegetius, Epitome Detail of the tombstone of Marcus Caelius showing his 2.20). We may predecorations: phalerae on his chest, an armilla on his arm sume that our man and torques on a band hanging from his neck. © Karwansaray BV © Karwansaray BV The opposing armies Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 34 17-05-2009 17:50:18 The opposing armies dodges from having served in the ranks themselves; this made their discipline all the more stringent because they had endured toil and hardships and expected the soldiers in their charge to do the same (see Tacitus, Annals 1.20 on Aufidienus Rufus). Other centurions were directly commissioned with no prior military service. Marcus Vergilius Gallus Lusius, adopted into a wealthy equestrian family that could call on Augustus’ patronage, was such an officer (ILS 2690). We have already seen how he was decorated by Augustus (and also by Tiberius), and he must have had a real talent for soldiering, because he rose through the centurions’ ranks to the exalted post of primus pilus, went on to command a cohort of Ubian infantry and cavalry, and then became tribune of a praetorian cohort. This was in the period before all of the cohorts of the Guard were based in Rome (Suetonius, Augustus 49.1; Tacitus, Annals 4.2); he may have found himself at Aquileia, where praetorians were stationed as something of a ‘rapid reaction force’ (CIL V 886, 904, 924, etc. with Tacitus Annals, 1.24). Lusius’ final senior post was as idiologus (chief financial officer) of Egypt, a reflection of the administrative skills developed by senior Roman officers. Resolute and tenacious legionaries If centurions were tough and determined men, so too were the legionaries under their command. In AD 7, at the battle of the Volcaean Marshes (or Mons Claudius), a Roman army of five legions (probably VII, VIII Augusta, XI, and two drafted in from the eastern provinces, perhaps IV Scythica and V Macedonica), auxiliaries and various allies, was surprised during the great Illyrian Revolt. Velleius Paterculus, who served as a legate in the war (but did not fight in this particular battle), describes how the steadiness of the legionaries averted disaster: [The two Batos, leaders of the rebels,] surrounded five of our legions, together with the troops of our allies and the cavalry of the king (for Rhoemetalces, king of Thrace, in conjunction with Augustus’ legionary army Following his victory at Actium in 31 BC, and the conquest of Egypt and Cyrenaica from Antony and Cleopatra in 30 BC, Octavian found himself in control of 60 or 70 legions. More than half of the legions were disbanded, the time-served soldiers of both sides settled in veterans’ colonies. After seven years or so, by which time Octavian had become Augustus, he had whittled the number of legions down to 28, retaining especially those regiments originally enrolled by his adoptive father, Julius Caesar (e.g. V Alaudae, IX Hispana, X Gemina), and, as a mark of conciliation, the most renowned of the Antonian formations (e.g. IV Scythica, VI Ferrata, XII Fulminata). Unlike the legions of the Late Republic, which were raised to fight in a particular war and usually disbanded after six years, Augustus’ imperial legions were permanent formations. Some survived for centuries. Remnants of V Macedonica and IV Scythica are still attested in AD 635/6 and 637/9 (see Ancient Warfare II.5). the aforesaid generals [Caecina Severus and Plautius Silvanus] was bringing with him a large body of Thracians as reinforcements for the war), and inflicted a disaster that came near being fatal to all. The horsemen of the king were routed, the cavalry of the allies put to flight, the auxiliary cohorts turned their backs to the enemy, and the panic extended even to the standards of the legion. But in this crisis the valour of the Roman soldier claimed for itself a greater share of glory than it left to the generals, who departing far from the policy of their commander, had allowed themselves to come into contact with the enemy before they had learned through their scouts where the enemy was. At this critical moment, when some tribunes of the soldiers had been slain by the enemy, the prefect of the camp and several prefects of cohorts had been cut off, a number of centurions had been wounded, and even some of the centurions of the first rank (primi ordines) had fallen, the legions, shouting encouragement to each other, fell upon the enemy, and not content with sustaining their onslaught, broke through their line and wrested a victory from a desperate plight. Velleius Paterculus 2.112.4-6 (cf. Dio 55.32.3) Rigorous training, such as that described by the Panegyrist of Valerius Messalla Corvinus ([Tibullus] 3.7.82105), and experience meant that in circumstances like the near-disaster described above, the legionary could be his own general (cf. Appian, Civil Wars 2.72) and save the day. There were, of course, defeats, not least the disaster in the Teutoburg Forest, and some soldiers were unwilling combatants who would rather be anywhere than on the battlefield, like the poet Tibullus: Let another be stout in war and, Mars to aid him, lay the hostile chieftains low, that, while I drink, he may tell me of his feats in fighting and draw the camp in wine upon the table. Tibullus 1.10.29-32 But Albius Tibullus was a Roman and, despite his fears, he served with distinction under Messalla in the Aquitanian War in 27 BC, winning dona militaria (Suetonius, Life of Tibullus). It was rare for the Augustan legionary to flee from the enemy in panic. Sometimes it did happen, but he usually stood his ground and died fighting or fought his way clear (e.g. Velleius Paterculus 2.119.2 on the Teutoburg; Dio 56.11.3-6 on Raetinum). In 17 BC, the famous Legio V Alaudae was surprised in Gaul by an army of Germanic raiders and its aquila, the eagle standard in which the spirit of the legion resided, was captured (Velleius Paterculus 2.97.1). This was the ultimate disgrace but the Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 35 35 17-05-2009 17:50:19 © Karwansaray BV The opposing armies Gilded silver phalera depicting a dog or, perhaps more likely, a wolf. From Oberaden, now at the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern, Germany. defence of the eagle, although unsuccessful, was fierce. The poet Propertius commemorates the brave defence of the standard by a certain Gallus, who “died for the aquila, bathing it in his blood” (Elegies 4.1.95-96). It has been proposed that Gallus was not an aquilifer, but was actually the primus pilus of the legion. Gallus’ brother, Lupercus, also died in the battle. He was among the cavalry ambushed earlier in the day by the Germans, leaving the legion without its eyes and ears and vulnerable to attack (Propertius, Elegies 4.1.9394, with Dio 54.20.4-5). The Germans, surprised at their success and fearful of the revenge the Romans would wreak upon them, sought terms, handed over hostages to ensure their good behaviour, and presumably also returned the eagle standard (Dio 54.20.6). At the outbreak of the Illyrian Revolt in AD 6, Legio XX was defeated. Sent by Tiberius as an advance force to secure Siscia and guard the route from Pannonia to Italy, the Twentieth was ambushed by one of the Batos and suffered heavy casualties (55.30.1-2). The legion’s legate, however, did not try to retreat; Valerius Messallinus was determined to fulfil his mission. The legion was now reduced to half its usual strength; it was probably not up to full strength (4,800 infantry and perhaps 120 caval36 ry) at the start of its mission, and it is conceivable that Messallinus had only around 2,000 men left to make the second attempt to reach Siscia. On account of their small number, Messallinus and the men of the Twentieth were surrounded by 20,000 of the enemy, but the legionaries broke through the enemy and put them to flight. Siscia was secured (Velleius Paterculus 2.112). It may have been for his part in this second battle that Lucius Antonius Quadratus, a legionary of the Twentieth, received one of his two sets of torques and armillae from Tiberius Caesar (ILS 2272; note also Velleius Paterculus 2.104.4 for the pride of legionaries who had been decorated by Tiberius). It was once thought that the Twentieth was honoured with its famous titles, Valeria Victrix (Valiant, Victorious), for this victory, but the epithets were actually awarded more than 50 years later for its part in defeat of Boudicca in Britain. On the death of Augustus in AD 14, the legions stationed on the Rhine and in Pannonia revolted. The historian Tacitus paints a vivid picture of disgruntled legionaries, forced to serve for many years beyond the terms they had signed on for, living in rudimentary camps, and when they were eventually discharged given scraps of barren land instead of the fertile small holdings they had been promised (Tacitus, Annals 1.16-17). However, Tacitus’ image is somewhat exaggerated. That soldiers were kept under arms beyond the expected 25 years is demonstrated by the funerary inscriptions (e.g. CIL III 2014, 33 years). That the land veterans received instead of a large lump sum pension was poor in certain areas, for example around Emona, has been confirmed by modern archaeology, but the loudest cries among the mutineers came from the unwilling legionaries, that is those conscripted to meet the manpower crises triggered by the Illyrian Revolt and the Varian Disaster. A large proportion of volunteer legionaries mutinied because their pay (good – when it was paid on time) and discharge benefits (potentially good) were viewed as in the gift of Augustus. The early imperial army was very much his private force, and the soldiers were paid mostly out of the emperor’s personal resources. The legionaries knew Tiberius, Augustus’ successor, as a general in the German and Illyrian Wars, but they did not know if he would be as generous as his predecessor, the towering figure who had dominated the Roman world for six decades. The mutinies of AD 14 were stimulated as much, if not more, by fears for the future as by dissatisfaction with the current terms of service. A more contented image of the Augustan legionary is provided by the epitaph of Titus Cissonius, who served in Legio V or VII (ILS 2238 and AE 1998, 1386). As a veteran he was settled far from his native Italy and ended his days in Asia Minor, but he was happy with his lot. The words inscribed on his tombstone were surely requested by the man himself: “While I was alive, I drank freely; you who are alive, drink!” n Ross H. Cowan gained his PhD for a study on Roman elite units and is now a freelance writer and historian. He has published several books and numerous articles on all aspects of warfare in the Ancient world. Further Reading - L. Keppie, Colonisation and Veteran Settlement in Italy 47-14 B.C. . Rome 1983 - L. Keppie, The Making of the Roman Army, From Republic to Empire. London 1984 - L. Keppie, Legions and Veterans: Roman Army Papers 1971-2000. Mavors volume 12. Stuttgart 2000 - V. A. Maxfield, The Military Decorations of the Roman Army. London 1981 - R. Syme, ‘Some Notes on the Legions Under Augustus’, Journal of Roman Studies 23 (1933), 14-33 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 36 17-05-2009 17:50:20 The opposing armies The legionary’s equipment Archaeological evidence Contrary the for to situation Germanic Warriors, evaluation the of archaeological data for the Roman soldier has been an ongoing process since the first sci- © Karwansaray BV entific excavations in Germany. This started under the auspicies of the ‘Reichlimeskommission’ (imperial limes committee) between the 1890s and the end of WWI. Since then a gigantic number of artifacts have been found, evaluated, sorted in relative chronologies and, where possible, linked to absolute dates. Archaeology as a science has improved as well with the result that, today, we have a rather detailed and accurate image of the Roman soldier and his kit, although several detailed questions about his equipment still wait for a definite answer. By Christian Koepfer A collection of lead and earthenware slingshot from Haltern. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. For the first decades of the imperial era, we have ample archaeological evidence from a variety of archaeological sites. Most important of these are – for our purpose –Dangstetten, terminus ante quem (t.a.q., see the note about archaeological terminology on p.50) 9 BC, Augsburg-Oberhausen with a t.a.q of AD 15/16, Haltern with a t.a.q. of AD 15/16, and Kalkriese with a highly disputed t.a.q of AD 15/16. These sites offer an insight into not only what the equipment was like, but also into how the equipment changed over the period between 9 BC and AD 15/16 AD. Defensive equipment The defensive equipment of the Roman soldier consisted of a helmet (galea, cassis), body armor (lorica), and a shield (scutum, parma, clipeus). The helmets dating from this period are of the later Montefortino types, the Mannheim types (‘Jockey-Cap-Helmets’), the Hagenau types (aka Coolus) and the Weisenau types (Imperial Gallic). They were made from iron, bronze, or brass, and in some cases from several of these materials, such as a Hagenau helmet from Haltern, which had a reddish bronze (copper and tin alloy) skull, and a yellowish brass brow-guard (copper, tin and zinc alloy). Most examples of Weisenau helmets also have this feature, e.g. a helmet from Idria pri Baci (Slovenia), which probably had a tinned iron skull and tinned iron cheek pieces, both with brass decorations. In some cases, the decorative rivets of these helmets had red coral or enamel inlays, an Ancient Warfare 37 AW special mei09.indd 37 17-05-2009 17:50:21 The opposing armies © Johnny Shumate 38 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 38 17-05-2009 17:50:23 The opposing armies identical device can be found on daggers and dagger sheaths as well. Attempts have been made to link helmet types to certain periods or historic events; Mannheim types seem to be connected to Caesar´s campaigns in Gaul, and the late Montefortino types to the civil wars. However, considering the length of service such items enjoyed in the Roman army, as testified to by several owners’ inscriptions on a single item, it is sensible to assume that all those types saw service simultaneously during the period under consideration. Masked helmets may have been worn by Roman infantrymen, but then only standard bearers. Body armor was most probably worn over a padded garment (subarmalis), which could have textile straps attached to it covering the lower body and thighs as well as the upper arms. There is some evidence suggesting short-sleeved versions of this garment. This piece of equipment served to protect the body from blunt trauma injuries, as well as making it more comfortable to wear the metal armor especially on the march - while simultaneously protecting the soldier’s clothes from rust, dirt, and damage through chafing. As can be seen on the statue of Augustus from Primaporta, this garment may have been quite colorful, especially the pteryges and their tassels, which are displayed as being red and blue. On the other hand, the colors on that particular statue may simply follow artistic conventions and not be a © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. Foto Christian Grovermann This legionary wears a helmet after a find from Oberaden; an early type of lorica segmentata as suggested by M.C. Bishop after finds from Dangstetten and Kalkriese. Under the segmentata he wears a simple padded subarmalis over a simple white tunic, as suggested by contemporary tombstones and wall paintings. His shield is identical to the legionary in the other picture, but has a different shield boss after a find from Haltern. The belt is based on finds from Augsburg-Oberhausen, the framescabbard is after a find from Kalkriese. Shoes and sword are again based on finds from Mainz. Upper chest plate of a lorica segmentata found at Kalkriese. representation of real equipment. Also, such a colorful version may not have been deemed appropriate for regular soldiers. For body armor chainmail (lorica hamata) and segmented plate armor (lorica segmentata) was commonly used. Although it has often been suggested (based on depictions of soldiers on tombstones) that ‘leather’ or rawhide armor was also in use, so far no material evidence has shown up to support this hypothesis. Moreover, after the conquest of the Alpine region and its foothills, iron was available to the Romans in huge quantities. It seems sensible to stick with the material evidence and dismiss the theory of ‘leather’ armor until solid material evidence becomes available. Leather finds are uncommon, but not too rare to remove the possibility of eventually finding fragments of leather armor, if it existed. Finds related to chainmail and segmented armor exist in larger quantities from the different sites: fragments of chainmail, chainmail closing hooks, and buckles and hinges from segmented armor have been found at the earliest site, in Dangstetten, suggesting a continuous use throughout the period. The earlier types of segmented armor apparently did not yet have the hooks that were used to tie the girdle plates of newer types, so it has been suggested that the early types of this kind of armor were completely closed with belts and buckles. The larger number of such buckles found in Dangstetten and other early sites seem to support this idea. Ancient Warfare 39 AW special mei09.indd 39 17-05-2009 17:50:24 © Karwansaray BV The opposing armies One of the pilum shanks from Oberaden, showing both the clamping piece and the rivets for fastening the shank to the wooden shaft. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. However, among the finds from Kalkriese there are already some hooks of the later type, suggesting the introduction of a new type sometime between the Dangstetten and Kalkriese horizons. The heavy iron armor plates from Kalkriese had a brass edging, and were covered with silver foil, suggesting that these particular objects were used by a soldier of high status. Offensive equipment The common offensive equipment of Roman soldiers consisted of a heavy throwing spear (pilum), a short sword (gladius), and a dagger (pugio). Soldiers may also have been regularly equipped with a sling (funda) and lead sling bullets (glandes). A most interesting series of pila were found at Oberaden. These pieces even had some of the wooden parts preserved, allowing a quite accurate picture of the weapon. The finds consist of a thin, long round or square iron rod, tipped with a pyramidal head, and ending in a flat tang, or spout, or in a thin, tapering tang. The first type of these were set with a tang into a wider section of a wooden shaft, and riveted to it with at least two rivets. Pyramidal, square-sectioned iron clamps held the wood together on the upper point of the wooden shaft. On their lower end the pila were equipped with butt spikes. Several of the pila from this period show decorations in the form of hor- izontal ridges or recesses on the iron rods, or just below the tip. Other than common opinion suggests, the iron shafts and tips were hardened, thus implying that theses shafts were not intended to bend, but rather would deeply penetrate the target’s defenses. The swords from this period, classified as ‘Mainz’ gladii, had a leaf-shaped blade, a usually wooden round pommel, a segmented or incised bone or wooden grip, and a half-circular wooden hand guard with an oval section, supported by a brass or bronze plate. Many of the blades were of a layered construction of different types of steel, visible in the form of a striped blade with lighter and darker stripes running parallel to the edges, simultaneously incorporating the quality of hard steel and soft steel to the blade, resulting in a somewhat flexible blade with sharp edges. Some were of a single type of steel and had welded-on cutting edges. The handle parts were often intricately decorated with carvings. Two different types of frame sheaths for the swords were common, one type with metal-covered facings and interasile decoration, and another type with leather covered facings and a (partial) metal frame. Both types had a set of two horizontal clamps, holding two rings on each side of the scabbard, through which it was connected to the belt. For this connection several theories exist, but it is currently not entirely clear how it worked. A similar problem exists for the dagger (pugio) sheaths, but in some cases belt plates with attached frogs were used for suspension. The daggers were, like the swords, leaf-shaped, and had rather long and thin tips with typically a square section. Many also had a layered construction, displaying differentcolored lines along the fluting or the central ridge. Some examples had silver- or brass- inlayed decorations and decorative rivets with red enamel inlay on their handles. Three types of sheaths are known: plain metal sheaths from Dangstetten, metal sheaths with inlay, wooden sheaths with a silver- or brass-inlayed iron plate on the front and frame sheaths similar to the frame sword scabbards. The exact dating of these is, due to the length of service of these objects, difficult. There are clear dates for some plain metal sheaths and a frame sheath from Dangstetten, as well as a silver-inlayed dagger with red enam- Two iron pilum fastening clamps from Kalkriese. © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. Foto Christian Grovermann 40 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 40 17-05-2009 17:50:25 The opposing armies ply decorated u-shaped buckles were found, whereas Haltern and Kalkriese have brought several pelta-shaped and more intricately decorated buckles to light. Over the course of this period, the design of military belts seems to have changed from rather simple belts with little metal decoration to the plate covered designs as displayed on numerous early 1st century AD military tombstones. However, not all of those later belts were completely covered with plates, as finds from Idria pri Baci (Slovenia) and Windisch (Switzerland) suggest. As Dangstetten was only occupied by a single legion, it may also be that finds just mirror different styles of fashion in different legions. But since ‘earlier’ and ‘later’ types of buckles are both found in Augsburg-Oberhausen and in Haltern, it seems quite sensible to assume a chronological change in style. In the end the military belt became the status symbol that separated civilian from soldier throughout the Imperial period. n elled rivets from Haltern. Slings seem, judging by the amount of lead sling bullets found, to have seen wide use. Since the slings were made of textiles or leather, no examples survive. The weapon seems to have been quite successful, especially in combination with lead bullets, which could reach a theoretical range of circa 450 m due to the high density of the material, with enough energy to easily penetrate a human skull. Clothing Only a small number of actual clothing remains from this period exist, and these are mostly from Egypt. Contemporary depictions show soldiers mostly in white, wide woolen tunics, although other colors like very light blue, green or red are also sometimes seen. The most important source here are the frescoes from the so-called ‘Tomb of the Statilii’ on the Esquiline in Rome. Although depicting the founding myth of Rome and thus referring to an earlier period, it is one of the few contemporary sources for the color of clothing of Roman soldiers from the Augustan period. Tunics and tunic fragments from this time found in Egypt are almost exclusively (off-) white, often decorated with a pair of colored vertical stripes, the clavi. An item often worn over the tunic and under the belt was the so-called fascia ventralis, a kind of cummerbund, which was used to make the belt sit properly, perhaps preventing chafing from the belt plates and fittings, and also to form a bag for small items, since trouser-pockets were no option. The frescoes also suggest the use of colored, in this case red, cloaks. Shoes have been found for example at Mainz, showing intricately cut sandal patterns, with heavy, nailed soles. It may be assumed that Roman soldiers wore naal-bound woolen socks (udones) inside their sandals to cope with the climate north of the Alps. Such socks Christian Koepfer teaches archaeology at Augsburg university where he leads a project on experimental archaeology. Further reading: © Karwansaray BV Bronze alloy belt plates (top and bottom) and a pelta-shaped belt buckle from Haltern. The bottom plate has been silvered. Now in the Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern. were found in Egypt, and are depicted on sculpture such as the late 1st century AD Cancelleria relief in Rome. The belts seem to have undergone a change during this particular period. Whereas we hardly find any rectangular or square belt plates at the site of Dangstetten, some were found on the other sites. Also the belt buckle seems to change in form. In Dangstetten and Augsburg Oberhausen mainly sim- - G. Fingerlin, Dangstetten: Katalog der Funde. 2 volumes. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte von Baden-Württemberg 22 and 69. Stuttgart 1986 and 1998. - S. v. Schnurbein, ‘Die Funde von Augsburg-Oberhausen und die Besetzung des Alpenvorlandes durch die Römer’, in: J. Bellot, W. Czysz und G. Krahe (eds.): Forschungen z. Provinzialröm. Arch. in Bayerisch- Schwaben (1985) - W. Hübener, Die römischen Metallfunde von Augsburg Oberhausen. Kallmünz 1973 - Müller, Die römischen Buntmetallfunde von Haltern. Mainz 2002 - Hamecker, Katalog der römischen Eisenfunde von Haltern. Mainz 1997 Ancient Warfare 41 AW special mei09.indd 41 17-05-2009 17:50:28 © Johnny Shumate The opposing armies 42 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 42 17-05-2009 17:50:30 The opposing armies Hit and run The Germanic warrior in the 1st Century AD The Germanic warrior confronted the Augustan legionary at a distinct material disadvantage. The Augustan legionary was an ‘iron man’, encased in body armor and helmet, savagely armed with a short sword and two javelins. Iron or bronze edged his rectangular shield, culminating in an iron boss. Iron bridled the legionary’s horse, dug his trenches, manacled his prisoners, and even provided traction for his hobnailed boots. A legion on the march, with approximately forty pounds of arms and armor per soldier, bristled with over a hundred tons of steel. By Michael J. Taylor The abundance of iron on the Roman side was the product of the sophisticated Mediterranean economy, and of the complex mechanisms of the Roman state. Iron was mined from diverse locations (Etruria, Southern Gaul, Spain, etc.), transported to the military frontiers by a coordinated system of rivers and roads and then hammered into arms and armor in large-scale legionary fabricae. Weapons and armor Enjoying such a material advantage, a Roman observer such as Tacitus could only marvel at the relative scarcity This figure is based on several finds from Germany. He has a hexagonal shield and a set of three spears, one is a larger thrusting spear, while the two others are ‘multi-purpose’ javelins. His cloak is based on a later find, but it is reasonable to assume that such cloaks were already used at the time of the Clades Variana. He has his hair tied in a ‘suebian knot’, attested to by a bog corpse. of steel tools and weapons amongst Rome’s Germanic opponents: “Iron is not common, a fact that you might gather from the manner of their weapons. Few have swords or long lances, but they carry spears with short and narrow tips which they call framea in their own language. This is such a vicious and handy weapon that they use it for both long range and hand-to-hand combat. Even the cavalryman is content with a framea and shield. Each infantryman spews forth many missiles, and either naked or wearing a light cloak they hurl them immense distances… few wear mail, and scarcely one or two have a helmet or leather cap.” (Germania 6.1-3) Weapons caches in Germany confirm the lack of swords and armor. A cache in Ejsbol Moss in Denmark contained 60 swords, 190 spears, 200 javelins, and 160 shields. While it cannot be said with certainty that any weapons cache will reflect the reality on the battlefield, the interpretation that the Ejsbol Moss hoard reflects the equipment of a company of 160-200 soldiers would imply that only one-in-four Germanic warriors was lucky enough to own a sword. Swords and armor, which equipped the lowliest Roman soldier, were reserved only for the wealthier class of warriors in Germanic society. The Germanic lack of iron was not due to a lack of natural resources. Germany was (and remains) rich in iron ore. Nor was it from a lack of technical skill. Germanic smiths produced weapons of equal quality to their Roman provincial counterparts. But the primitive nature of Germanic society and economy inhibited the mass-production of steel. The collective efforts of village charcoal-burners and smithies in Germania could not match the out-put of slave-run mines in the Roman Empire, where the ore-producing island of Elba was nicknamed “Smokey” (Aethalia) because of the smelting fires. Nor could the hap-hazard efforts of a few German magnates patronizing local craftsmen match the command-directed efforts of legionary craftsmen. Strategy and tactics This basic disparity in arms and armor would inform Germanic tactics on the battlefield. The Germans by and large did not seek head-to-head battles with the Romans. Rather, they utilized ambuscades and harassment tactics. Disadvantaged in close combat, the Germanic barbarian triumphed when he was able to rig the fight in his favor. The Kalkriese battlefield shows clear signs of a pre-planned ambush. Tribal forces constructed an earthwork parallel to the route between the marsh and mountains to conceal themselves while the legions wandered into the ‘kill zone.’ Such ambuscades took advantage of the fact that Germania was heavily forested and poorly drained, with few roads. It was difficult for a legion to move and to maintain a combat effective formation while negotiating marsh and woodlands. Trees covered far more of Germany in the 1st century AD, than today; it would not be until the high Middle Ages that the majority of Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 43 43 17-05-2009 17:50:30 The opposing armies © Karwansaray BV Germany was covered by open fields. There was limited space convenient for a Roman-style pitched battle. The Romans tried to improve their mobility by building bridges and military roads: Domitian constructed over 120 miles of road network in the 80s, but to no avail. The construction of roads and bridges took time, and shortened an already limited campaigning season. When coordinated properly, Germanic ambushes could be devastating. Three legions, or roughly 12,000 men, were wiped out by Arminius. Upwards of 1300 Romans perished when their detachments were separated in a bungled counterattack against the Frisii in 28 AD. An entire legion, the 5th Alaudae, disappeared off the books during an incursion against the Dacians sponsored by Domitian in 85-86 AD, presumably annihilated. Yet coordinated ambushes were still rare. The leadership necessary to coordinate complex ambushes was often lacking amongst the Germanic tribes, which remained non-state societies where the power of leaders rested primarily in persuasion and example. A leader like Arminius was exceptional, able Single-edged Germanic slashing sword dated to the early Imperial era. Now in the Museum for Pre- and Early history, Berlin. 44 to forge a multi-tribal coalition and to coordinate a complex ambush, which included coercing the drudgery required to dig earthworks. But Arminius paid for his unusual authority. Tribesmen alarmed by his waxing power murdered him. Likewise, Marboduus, a king who forged the Marcomanni into an increasingly centralized state, soon suffered exile by those who resented his novel powers. Roman diplomatic efforts, which subsidized and rewarded loyal chieftains, further frustrated coordinated resistance. Arminius’ brother Flavus and his father-in-law Segestes remained Roman collaborators even after the destruction of Varus’ army. The most prominent Germanic tactic was simply to avoid a pitched battle altogether, and wait for the Romans to retire back to their side of the Rhine. Julius Caesar encountered virtually no resistance in his twin crossings of the Rhine in 55 and 52 BC, doing little but burn a few abandoned huts; his Suebic opponents withdrew to the forests to wait out the invasion. Roman commanders were repeatedly frustrated by the unwillingness of their opponents to do battle, knowing that they would easily triumph if they could only achieve a pitched battle. For outclassed Germans discretion was the better part of valor. When the Germans did offer pitched battle, the basic tactical formation for both infantry and cavalry was the wedge (cuneus). The advantages of a wedge formation are many, especially when moving through a heavily forested area. Wedge formations allow for both forward movement and flank protection. A wedge can flatten into a forward facing line to face a frontal attack, or collapse into a column to receive an attack from the flank. With a wedge, only the point makes initial contact with the enemy, allowing the decision to either commit the entire body or withdraw before too many warriors are engaged. Smashing into an enemy formation, a wedge produces a natural double ‘echelon’ attack. The enemy in the center reacts to contact from the point, often by weakening the flanks, which are then hit by the outer edges of the wedge. Certainly their use of wedge formations impressed Roman commanders, who sometimes adopted this formation as well. The skills of Germanic cavalry were notable enough to prompt the Romans to recruit Germanic mercenary cavalry. However, Germanic horsemen were severely disadvantaged by the inferiority of their mounts. Skeletons of Germanic horses reveal that they were significantly smaller than Roman breeds. The Romans often re-mounted Germanic mercenaries on superior Gallic steeds. Germanic cavalrymen were seldom better armed or armored than their infantry counterparts, carrying only a spear and small shield. According to Tacitus, they where capable of rudimentary maneuvers, particularly a right wheel, but nothing comparable to complex equestrian exercises practiced by Roman horsemen. Caesar claims that Germanic riders often dismounted to fight, essentially using their horses as taxi services rather than combat-platforms, a phenomenon like linked to both the inferior size of horse and a lack of effective cavalry saddles. Germanic armies were perhaps more conspicuous for what they could not do. They could not build a bridge. They could not assault a walled town. They could not construct artillery pieces, unless aided by Roman prisoners or deserters. Even archers were rare in the 1st century AD, although by the 2nd Century the Germanic warrior had embraced the military use of the bow. Germanic war-bands had no supply train; the warriors either carried their own rations or lived off the land, and hunger plagued offensive operations. These factors put Germanic armies at a severe disadvantage when faced with the superior military capabilities of Rome. Retinues and raiding The basic combat unit in Germanic society was the retinue (comitatus). A prominent man (princeps) kept a band of young warriors from his personal resources. In the time of Caesar, these retinues were temporary, a posse that formed around an ad-hoc leader for the purpose of a single raid. The retinue dispersed when the objective was accomplished. By Tacitus’ time, however, retinues had become permanent, and retinue leaders formed an increasingly distinct elite in German society. The retinue leader provided his followers with arms, and feasted them in times Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 44 17-05-2009 17:50:31 The opposing armies man wine, eating of Roman tableware and wearing Roman jewelry. In short, economic and military contact with Rome facilitated social stratification in Germanic society, creating a new warrior elite, who “when not at war pass some of their time at hunting, but more in leisure, devoted to food and sleep.” (Germania 15.1)This new warrior-class increasingly took a greater share of societal wealth for itself. Caesar reports that land in Germany was redistributed yearly, to avoid economic stratification. By Tacitus’ time, the same annual distributions occurred, “only now lands are partitioned according to dignity. ” (Germania 26.1) More ominously, some retinue leaders received yearly gifts from both individuals and communities. While Tactitus stresses that these contributions were voluntary, they seem suspiciously similar to ‘protection’ money extorted by modern mafia. Retinue members closely followed their leader, who was distinguished by superior arms and armor. Unlike common warriors, the retinue leader would likely carry a sword rather than a spear, wear some form of body armor and possibly don a helmet. Tacitus sums up the relationship in combat between leader and retinue: “when they come to battle, it is a disgrace for leaders to be surpassed in battle by their retinues, it is shameful for members of retinues not to equal their leaders. Truly, it is the greatest infamy to return from battle having survived one’s leader. To defend him, to guard him, to assign one’s own mighty deeds to his glory is the highest bond of loyalty.” (Germania 14.1-2) cowardice. Given that the fighting capabilities of the male population no doubt varied significantly, select youths were picked on the basis of martial ability to form an elite vanguard of the general mass. Supposedly, elite bands of 100 infantry, appropriately called ‘Hundreds’ were picked by each canton (pagus), which then ran alongside the cavalry in battle. Yet the ‘Hundred’ in Tacitus is controversial. In the Middle Ages, the term ‘Hundred’ was used as an administrative unit (in England a sub-division of a shire). Some scholars believe that Tacitus confused the term for “the levy from the (administrative) hundred” with “a company of 100 men.” However, there is no good reason to discount Tacitus; it is quite possible that Medieval administrative ‘Hundreds’ developed out of military units, just as Roman voting centuries developed out of armed companies. Should the picked Hundreds fail in battle, a levee en masse of all males might mobilize to counter the emer- The Germanic horde In the background of increasingly aggressive retinues, the tribal militia remained, mobilizing the male population for both defense and for shortterm offensive operations. Most free Germanic peasants were expected to own arms. The major rite of passage for a Germanic boy was to be presented before a tribal assembly with a shield and spear, symbolizing his new role in both political and military affairs. The tribal levy doubled as a political assembly in which armed citizens debated war and peace, elected temporary war-chiefs and tried capital cases, particularly military crimes involving desertion and © Karwansaray BV of peace. Moveable wealth, in the form of rings and torques, was the primary form of reward (the theme of a chief or king as ‘ring-giver’ is repeated in medieval Germanic literature; modern readers will see it reflected in the works of JRR Tolkien). A retinue chief was obliged to pursue constant raiding activities: he needed a steady stream of booty to pay and feed his retinue. The raid was the standard form of Germanic warfare. In a society with limited moveable wealth, raids sought primarily slaves and cattle. The successful Germanic raider found a ready market for both in the Roman Empire. German slaves (particularly blondes) were a luxury item in Rome. Roman slave traders wandered deep into the frontiers, buying up hapless barbarians enslaved by inter-tribal raiding. Meanwhile, cattle had always been a primary source of wealth amongst German society, producing a vigorous culture of cattleraids. Rustled cows served to feast the retinues, but also found ready market in the Roman camps, where hides were utilized to produce the thousands of tents and boots required to shelter and shod the legions. The Frisii were even required to pay tribute to Rome in the form of hides. The advent of a Roman market for cattle and slaves may have stimulated an increased in inter-tribal raiding (as well as raids into Roman Gaul) as ambitious retinue leaders sought to obtain cattle and slaves which could in turn be exchanged for Roman luxury goods such as spices and wine. Revenues from raids also financed the purchase of smuggled Roman weapons. With these purchases retinue leaders could arm their retinues with Roman swords and feast them in Roman style. This allowed them to recruit bigger retinues, and raid even more aggressively. Thus was the self-reinforcing economic cycle of violence in Germanic society. Indeed, E.A. Thompson has argued that development of permanent retinues between the time of Caesar (50s BC) and the time of Tacitus (98 AD) was very likely a direct result of Roman contact. Violent Roman incursions disrupted old equilibriums of power, and caused people to look to new military leaders for protection. The increased influx of Roman luxury goods allowed a new elite to define itself by drinking Ro- Edging of a hexagonal shield and decorated shield boss found in eastern Germany. Now in the Museum for Pre- and Early history, Berlin. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 45 45 17-05-2009 17:50:33 gency of invasion. Thus when Germanicus defeated the crack Cheruscan army of Arminius in 16 AD, he subsequently encountered a general force of “chiefs and commons, young and old.” (Annals 2.19) The mass of tribal infantry usually received the contempt of the Romans for poor discipline and performance. Tacitus reports one exception: the Chatti, who unlike the other Germans “know their place in the ranks, recognize opportunities, advance at a steady pace, plan by day, entrench by night, relying not on fortune, which is dubious, but on courage, which is certain. Moreover, they obey a leader rather than the whims of the army, something otherwise conceded only to Roman discipline. You will see other Germans going to battle; the Chatti go to war.” (Germania 30.2-3.) Certainly Tacitus sees the imprint of the Roman army on the Chatii. Given the service of many Germanic warriors as Roman auxiliaries, we can hypothesize that some attempted to reform their forces along Roman lines, enforcing foreign standards of discipline and subordination upon largely egalitarian tribal levies. However, if some chieftains did indeed attempt to reform their army along Roman lines (and we have only hints that they did so), they largely failed. It was simply impossible for non-state societies to replicate the patterns of authority and institutions of command in their sophisticated and stratified Roman neighbor. Germanic armies were organized along family lines, a fact which draws praise from Tacitus, who believed that this inspired courage and solidarity. Women often accompanied their lovedones. Tacitus describes them as ‘cheerleaders’ on the edge of battle, although they also doubled as crude logisticians, providing both “food and encouragement to the fighting men.” Women priestesses, such as Julius Civilis’ advisor Veleda, even played an important role in strategic and tactical decisionmaking through their roles as augurs and prophetesses. In battle While the vast majority of Germanic warfare consisted of small-scale raids, forays and skirmishes, large-scale battles did occur, often as a result of Roman 46 © Karwansaray BV The opposing armies This fairly small spear point may have tipped what Tacitus called a framea, used both as thrusting weapon and thrown as a javelin. Now in the Museum for Pre- and Early history, Berlin. incursion into Germanic territory. Setpiece battles on occasion also erupted between Germanic factions: In AD 18, a coalition of Cherusci and Langobardi under Arminius defeated Marboduus and his Marcomanni. The Chatti battled the Hermunduri for control of salt-flats in 58 AD; the Hermunduri emerged victorious and sacrificed all their captives to evidence their gratitude to the gods. In 98 AD, Roman observers watched as a coalition of Chamavi and Angrivarii defeated the Bructeri, with exaggerated reports of some 60,000 killed. Songs and chants marked the beginning of battle for the Germanic force. These songs recounted the deeds of gods and past heroes, and were in- tended to at once intimidate opponents and to cement group solidarity before the crisis of battle. The period of singing also allowed each side to gain a sense of the size and spirit of the opponent; whoever sang the loudest could expect victory. The positive effect of the rumbling war-chant (barritus) on morale can be measured by the fact that the Romans adopted an identical low-pitched war-cry, hurling back the haunting bellows that greeted them on the cusp of battle. Another marker of group solidarity was the presence of idols and totems of various gods. These religious objects would have been in many ways analogous to the eagles and signa of the Roman army (which were also imbued with quasi-religious significance), serving as a rallying points in battle and as a symbols of common identity. Battle was joined at a distance, with the exchange of great volleys of frameae. Germanic warriors carried multiple darts, and Romans noted their ability to hurl them great distances, largely because they were un-encumbered by cuirasses (the emperor Hadrian considered hurling javelins while burdened by body-armor to be the most difficult feat a Roman soldier could perform). It was important to recover spent missiles in lulls; Tacitus reports that the refusal of Germanicus’s legions to withdraw frustrated Cheruscan attempts to reclaim their spent javelins. In the worst-case scenario, the Germanic warrior was reduced to hurling rocks. At some point, combatants closed to fight hand to hand, although such close combat was usually brief; the weaker side withdrew when it sensed that it was outclassed. Tactius suggests that most confrontations oscillated repeatedly between sudden assaults and temporarily withdrawals. With a touch of characteristic sarcasm he notes “to fall back from a position, only to surge forward again, they judge to be strategy rather than cowardice.” (Germania 6.6) In his assault, the Germanic warrior inspired great terror in the Roman legionary. He was on average taller and more heavily built than his Roman counter-part, thanks to a diet rich in meat and cheese. Unencumbered by armor, the Germanic warrior could indeed Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 46 17-05-2009 17:50:33 The opposing armies rush on with great speed, in assaults that could unnerve a line of Roman infantry, causing them to break their wall of shields. Arminius was sure to secure the high ground opposite Germanicus in 16 AD, so as to add momentum to his warriors’ charge. The Germanic commander, be he king or chieftain, led in a heroic style. Arminius was badly wounded in battle with Germanicus, and smeared his face with blood in order to be better recognized. Vannius, deposed king of the Suevi, added honor to his exile by suffering a wound in a glorious last stand. Germanic warriors expected such heroic leadership, but had its disadvantages. The Germanic commander was in a poor position to actually control the battle once it began, unlike his Roman counterpart who rarely indulged in personal combat but was able to direct maneuvers from the rear. If the Romans held firm, however, their superiority in arms and armor would soon force a withdrawal, prompting Roman accusations that Germanic peoples lacked physical endurance. In reality, they were often merely regrouping for another assault. At other times, a deliberate withdrawal encouraged an over-exuberant Roman pursuit, which disadvantaged them as they lost their cohesion and discipline in the pursuit. If outclassed and forced into a rout, the defeated side withdrew into areas of dense forest or marshland to hinder pursuit. Nonetheless, Tacitus reports that every effort was made by Germanic warriors to recover the bodies of fallen comrades. Leaving behind a shield on the battlefield was also considered a mark of high shame (as it was for a Roman soldier). The end of a battle between the Roman army and Germanic tribes was not the end of the campaign. The Romans, usually victorious, would throw up a trophy and salute their commander. But the Roman army must inevitably withdraw. The commissary wagons would run low on grain; the early northern winter would soon impinge on further operations. As the Romans turned back for the frontier, the ‘defeated’ Germans harassed the Roman rear. Roman soldiers were secure from ambush only when they settled back into their legionary bases. Germania and Rome Roman propaganda from Caesar onward tried to emphasize the threat of Germanic invasion. Caesar himself recalled the invasion of the Cimbri and Teutones, defeated by his maternal uncle Gaius Marius, as justification for his own intervention against the Germanic war-band of Ariovistus. Augustus, following the Kalkriese disaster, repeated the same religious rituals that had been performed after the Cimbric victory at Arausio nearly a century before. Domitian advertised his actions against the Chatti in the 80s, although there was malicious gossip that lacking genuine victories and real prisoners he graced a sham Germanic triumph with actors in blond wigs. In the time of Trajan, Tacitus could argue that the Germanic tribes were an even more dangerous threat than the mighty Parthian Empire. But we should not be deceived by this apparent concern in Roman sources into thinking that the disunited and under-organized tribes of Germania posed a significant threat to the Roman Empire in the early Empire. The Romans themselves, when they set literary bombast aside, referred to Germanic incursions as mere banditry (latronicinium). The barbarian problem was, in the words of historian Peter Brown, little more than a “crime wave.” The Romans were able to hold a sparsely defended frontier with an incredibly circumscribed force. In 20 AD eight legions with auxiliaries, approximately 70,000 troops, manned the 820 mile stretch of the Rhine, with an average density of roughly 85 soldiers per mile. Four legions, roughly 40,000 soldiers with attached auxiliaries, manned the 1771 mile Danube frontier, with an average density of less than 25 soldiers per mile. Yet Roman contact was causing changes in German society. Smaller tribes were forging new confederacies to deal with the Roman threat. The leaders in these political efforts were the new class of warrior aristocracy, the retinue leaders, whose development was encouraged in part due to military and economic contacts with Rome. By the 3rd century, when the historian Ammianus Marcellinus picks up, old tribes like the Cherusci and Chatti have disappeared, to be replaced by new configu- rations: the Alamanni (“The Tribe of Everybody”), Saxons (“the Swordsmen”), Franks (“Fierce Ones”), and Goths (“the Good Guys”). With Rome wracked by a slew of civil wars, and the army withdrawn from the frontiers, the Germanic peoples emerged for the first time as serious threats to Roman survival. Yet these developments lay far in the future at the time of the clades Variana. The victorious alliance of Arminius by no means hobbled Roman power. His victory simply convinced the Romans that conquering Germania was more trouble than it was worth. Romans had being willing to endure far heavier casualties and far more significant setbacks to conquer other lands. But Germania, a heavily forested land which could grown neither grapes nor olives, was adjudged as not worth the cost. Yet the imperial power of Rome continued to be felt with great force. Arminius’ estranged nephew, Italicus, was taken to Rome and raised as a Roman citizen. In 47 AD, the emperor Claudius imperiously imposed Italicus upon the unwilling Cherusci, where he “was an affliction to the Cheruscan people.” (Annals 11.17) Despite the victory at Kalkriese, the Germanic tribes enjoyed their liberty only under the ominous shadow of imperial Rome. n Michael J. Taylor earned a BA in History from Princeton university and is currently a graduate student in Ancient History at UC Berkeley. He is also an officer in the California National Guard and a veteran of the Iraq war. Further reading: - J.G.C. Anderson, Tacitus: Germania. Bristol 1997 - M. Todd, The Early Germans. Oxford 1994 - P. Wells, The Barbarians Speak. Princeton 1999 - E.A. Thompson, The Early Germans. Oxford 1965 - M.P. Speidel, Ancient Germanic Warriors. London and New York 2004 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 47 47 17-05-2009 17:50:33 The opposing armies Arming the warrior Archaeological evidence Research into ancient German peoples suffered from a lack of interest and perhaps even stigmatization in Germany between 1945 and the 1970s. The Nazis had greatly misused extant historical and archaeological evidence to fit their ideological and mystical ideas: to do so, they often preferred to make the evidence fit their ideas of ‘German’ history instead of letting the data speak for itself. It took a while for the subject to become respectable again, while the last archaeologists and historians which were worked for, or under, the Nazis slowly were replaced by a younger generation in the last quarter of the 20th century. These new archaeologists generally had to base their work on results pre-dating the 1930s, but as new finds came to light, the old and new could be combined, resulting in new insights. It remains a politically sensitive topic, however. By Christian Koepfer In the following I will introduce some recent results of research into the arms and equipment of Germanic warriors. Simultaneously I will attempt to give an insight into the archaeological problems one encounters in this field. Chronology and sources One of the major problems in the academic discourse is that the terminology defines groups, which did not really exist as such. The modern historian needs to group cultures. Doing so, he is then able to show differences and similarities and discuss these. The ancient societies in question, however, defined themselves through attachment to a certain tribe and not through abstract terms like ‘Germans’ or ‘Celts’. Having said that, it is also important to remember that not all of these tribes were actually ‘Germanic’ in origin. Some of them had ‘Celtic’ roots, despite deriving from the right side of the river Rhine. The famous mat48 ter-of-fact statement that the Gauls lived on the left side of the Rhine and the Germans on the other comes from Caesar, who made it fit his own agenda. The individual tribes, such as the Chatti, the Cherusci, the Hermunduri, and all the others, were culturally and politically independent entities which nevertheless had a lot in common. They were separated by differences in customs, attire and dialects. Unfortunately, archaeologically these groups can barely be separated. The archaeologist Kossinna attempted to do so in the early days of pre-historic studies, but failed. It did not work for a variety of reasons, the main one being that certain material evidence must not necessarily be linked to certain cultures. For example, a certain type of weapon burial could be used in a certain region, which in itself may have been split among several tribes, which in their turn had a faction living in that region using other burial customs than the rest of the tribe. Or certain items could simply have been traded between tribes, thus suggesting a large area of a singular tribe, where in reality there were several ones. Another difficulty when dealing with this topic arises from the fact that we have hardly any ‘absolute’ (independently verifiable) dates which can be applied to the relative chronology of the material culture of the Germanic tribes. In other words: there is no skeleton to hang the flesh on. Most dates given are rather vague, and many questions about when an item was in use and in which context, have to remain unanswered for the moment. To make matters worse, the extent of archaeological prospecting has been quite uneven: some areas are archaeologically well documented, whereas others are not. This can lead to a distorted image. Finally, the narrative sources such as Tacitus or Cassius Dio are far from ideal. They have biases as explained elsewhere in this volume, they are full of internal contradictions, and often do not concur with the material evidence. Therefore, most statements made about specific ‘Germanic’ topics, in our case armament, have to remain approximations for now. With all these caveats in mind, one archaeological source stands above all others: a number of weapon graves discovered along the river Elbe and in Denmark. Defensive equipment Germanic warriors in the Augustan era seem to have worn no – or very little – body armor. No helmets have been discovered in Germanic context and only some fragments of Roman chain mail were found. Those had been deposited in a grave after having been cut into This warrior has a set of two ‘multipurpose’ spears and a round shield. This equipment is typical for the period: a large number of grave finds show this or very similar equipment. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 48 17-05-2009 17:50:34 © Johnny Shumate The opposing armies Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 49 49 17-05-2009 17:50:36 The opposing armies © Karwansaray BV Grave goods found in the area of the Treveri tribe (Trier region, Germany) dated to about AD 40-50. The deceased was buried with his most valuable possessions according to tribal tradition and shows how quickly they were Romanized. He had a gladius style sword, a Roman pickaxe, coinage and ceramics. The Treveri tribe supplied Rome with cavalry units since the early Augustan era, such as in the Ala Petriana Treverorum. Now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Trier. small pieces. The only type of protection that is attested in large amounts comes in the form of shields. Around 60 percent of warrior graves proved to contain a metal shield boss. Most of those were conical and ended in a spiked point, which suggests an offensive use as well: the shield bearer could thrust forward with his shield hand and thus could cause blunt trauma injuries to his opponent. The shield bosses were held in place by groups of first rather flat and later strongly domed rivets. A number of these shields also had short metal grip reinforcements on the inside. Shield shapes of the time seem to have been mainly round, although hexagonal and long-oval shields were Chronological terminology a l s o used. The shield boards consisted mostly of planks of alder wood, but some fragments also show the use of oak, fir, beech and birch. The planks were glued to each other side by side, tapering towards the shield rim. Again, there are exceptions as an example from Vaedebro shows, in which the shield boards were made from a single plank. The whole construction was held together by rawhide facings on the out- and probably also on the inside of the shield boards. In some cases metal edging for the shield was found as well. Evidence from finds from the northern German area suggests that the shields were painted in bright colors in geometric patterns. Some shields may have been decorated with bracteate (decorated metal) plates, however the dating of these objects is difficult. Archaeology has developed a series of methods which are all linked to a clear terminology describing methodological necessities, results and procedures. Chronology requires terms describing situations mirrored by singular findings or series of findings. There are two types of chronology, relative chronology and absolute chronology. Relative chronologies try to establish how individual findings relate to each other, that is, which objects in a series are older and which are younger. Relative chronologies can be established through a variety of methods, for example by interpreting stylistic elements of a certain group of objects. A good example is changing shapes of fibula brooches. There are more methods to determine relative chronology. Vertical stratigraphy is the identification of different layers of soil to explore what is deeper in the ground (older) and what further up (younger). Horizontal stratigraphy identifies the consecutive deposition within a layer, for example on a graveyard: which graves were dug first and which were added later. Absolute chronologies describe when a certain event took place, counting a number of years, months and days before or after an established date, such as Ab Urbe Condita (From the foundation of the City) or the traditional Western one: 50 They may have come in use only in the course of the first century AD, or at its end. They therefore were probably not in use during the Clades Variana. For the oft-mentioned ‘whicker-shields’ no evidence has come to light so far. Offensive equipment The main Germanic weapons were the spear and javelin. Large numbers of spearheads were found, allowing archaeologists to establish a rough typology based on their shape. Objects to be classified as spearheads need to be at least 15 cm long and have to have a thickness of at least 1.1 cm in one place. The smaller javelin-heads usually have two barbs, in some few cases only one. Spear and javelin shafts were mostly made from ash wood. Javelin shafts were often tapered from their barycentre outwards in both direc- the calculated date of the birth of Christ. In some cases a certain date of a relative chronology can be linked to a date in an absolute chronology, allowing all other objects in the relative chronology to be dated before or after this particular date. The terms used here are terminus post quem (date after which) and terminus ante quem (date before which). Linking relative chronologies to the absolute chronology is a very rare opportunity. For Roman history and archaeology a very important and famous example of such a link is the site of Pompeii: all objects found there can were constructed on or before August 24 AD. So everything found on the site has a terminus ante quem of August 24 AD 79. The date is known from a letter by Pliny the Younger. As often, dating was a puzzle even here. Had the literary account not survived, it would have been considerably more difficult to link the relative chronology of the site to an absolute date. A single piece of evidence in the puzzle can often make all the difference. That is the reason why it is so important to protect archaeological sites from illegal looting. The information gained from archaeological sites tells us, in the end, a lot more about the past than the objects alone and out of their archaeological context. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 50 17-05-2009 17:50:38 Photo Christian Grovermann tions. It is justifiable to assume that the shafts often were decorated with geometric carvings under the head, as can be deduced from later finds. Based on notches found on the edges of some of the larger leaf-shaped spearheads it has been suggested that these were not only used as thrusting weapons, but also as slashing weapons. This has to remain a speculation however, since the notches may also have been applied on purpose to show ‘battle experience’. In general spears seem to have been used to thrust, although it cannot be excluded that they also were thrown when the situation required it. The shape of many spearheads suggest a multi-purpose weapon. In fact, only over the course of the next two centuries did the typical ‘spear-sets’ with distinctively different weapons come into being. A clear division between hunting gear and weapon cannot be made for spears and javelins, probably the same weapon was used in both situations. Butt spikes for both spears and javelins are extremely rare in the archaeological record, so were probably rarely used. Swords are also rather rarely seen among the finds. The two-edged versions and their scabbards are similar to the late La Tène-type and seem to have been used mainly by cavalry. At the same time single-edged swords seem to have been en vogue among those foot soldiers who could afford such weapons. They had a tang that partially enclosed the hand, similar to the Greek falcate, but with a straight and flat blade. Knives are present in the archaeological record in considerable numbers, but the context seems to suggest that these were not regarded as weapons. In average the blades are rather short (7-12cm), and they were found evenly distributed among male, female, and child burials. Moreover, they were not burned before inhumation, contrary to almost all other types of weapons. A similar situation can be observed for axes and hatchets, as well as for bows and arrow. Although these objects are documented in a few cases, there is so far no conclusive reason to identify them as weapons of war in this period. The combinations in which weapons were deposited in graves tells © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. The opposing armies us how the individual soldiers were equipped; of which items their panoply consisted. These can be grouped as follows: A: Sword, shield, spear; B: Shield, spear; C: Shield; D: Spear(s); E: Sword; F: Sword, shield. It is difficult to deduce tactical or social propositions from these groupings, however. Only group A seems to be regularly related to cavalry, so a higher status of the deceased can be assumed in those cases. Clothing A number of Germanic textiles have been found in the northern bogs, mainly in Denmark and in Schleswig-Holstein (on the German-Danish border). A certain continuity in dress can be observed for Germanic males. Generally they wore woolen trousers, a long-sleeved woolen tunic and a rectangular woolen cloak. Details of the weaving patterns and decorations of the cloaks are well documented, showing quite bright colors for the cloaks, with complicated multi-color checkered patterns and striped tablet-woven decorations along the rims, which were often additionally decorated with tassels. The cloaks were usually woven on a weighted loom in one piece, applying different weaving techniques, such as different types of twill. Tunics and trousers seem to have been monochrome, but often had tablet-woven rims as well to stabilize the borders and prolong the life of the clothes. As we have seen, the archaeological evidence is quite difficult to interpret for a variety of reasons. So far it is still difficult to get an exact picture of the Germanic warriors that took part in the defeat of Varus’ army. However, a good approximation can be made. Not too surprisingly, this approximation is quite congruent with Tacitus´ report Metal parts of a Germanic shield, found in Kalkriese. It may have belonged either to a Germanic warrior fighting against the Romans or to a Germanic warrior in Roman service. about the Germanic warriors: "But few use swords or long lances. They carry a spear (framea is their name for it), with a narrow and short head, but so sharp and easy to wield that the same weapon serves, according to circumstances, for close or distant conflict. As for the horse-soldier, he is satisfied with a shield and spear; the foot-soldiers also scatter showers of missiles, each man having several and hurling them to an immense distance, and being naked or lightly clad with a little cloak. There is no display about their equipment: their shields alone are marked with very choice colors. A few only have corselets, and just one or two here and there a metal or leather helmet." Tacitus, Germania 1.6 Christian Koepfer is a regular contributor n Further reading - W. Adler, Studien zur germanischen Bewaffnung. Bonn 1993 - L. Jorgensen et. al. (ed.), The spoils of victory. Gylling 2003 - T. Weski, Waffe in germanischen Gräbern der älteren römischen Kaiserzeit südlich der Ostsee. BAR International Series 147, Oxford 1982. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 51 51 17-05-2009 17:50:38 The battle Arminius’ masterstroke The campaign of AD 9 In September AD 9 the Roman empire suffered its greatest setback at the battle of Teutoburg Forest in northern Germany. “The heaviest defeat the Romans had suffered on foreign soil”, wrote one contemporary of the battle. The winners: Arminius, a nobleman of the Cherusci, a tribe that dominated the area that roughly corresponds to the southern part of the modern state of Lower Saxony, and his confederation of Germanic warriors. The losers: Publius Quinctilius Varus and three legions, three cavalry alae and six auxiliary units. By Adrian Murdoch as he paced his palace on the Palatine Hill in Rome, is well-known, but so serious was the loss of Legions XVII, XVIII, XIX that the survivors of the battle were banned from Italy, the legions themselves were never replaced and in due course the Rhine became a barrier between civilisation and barbarism that was only ever unwillingly crossed © Carlos de la Rocha Arminius did what no military leader up to then had been able to do and few afterwards were to attempt. He stopped the Roman empire in its tracks and halted any imperial pretentions east of the Rhine. The emperor Augustus’ plaintive cry of “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions” (Suetonius, Life of Augustus 23), even into late antiquity. Little wonder that Arminius himself soon became a mythologized figure of German might. A massive statue of the Cheruscan leader, the 26.5 metre tall Hermannsdenkmal near Detmold, remains one of the more popular tourist attractions in Germany. He is as popular today as he ever was, thanks to the discovery in 1987 of the battlefield itself near the town of Kalkriese in Lower Saxony by an amateur British archaeologist – a find justifiably trumpeted in one German newspaper as “a second Troy”. The significance of the battle on German national consciousness can hardly be exaggerated. This, the 2000th anniversary of what the Germans call the Varusschlacht, has been embraced by the whole country, from German chancellor Angela Merkel, who opened Imperium – Conflict – Myth, the year’s flagship exhibition to the battle, to publishers who have flooded the mar- 52 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 52 17-05-2009 17:50:39 ket with new volumes describing the conflict. But how much do we actually know about the conflict itself? Contemporary accounts of the Roman campaign in AD 9 are, inevitably, fragmentary. It is possible to piece together a plausible account of what happened to Varus and his three legions, but there are discrepancies between the accounts of all of the classical historians that go well beyond their personal biases. Tacitus describes the battlefield but not the battle; Velleius Paterculus gives a considerable amount of background to the events and Florus adds colour. Only Cassius Dio gives us the details of the battle itself. But all of them are wise after the event and none of them were there. Varus, one of the Roman empire's most experienced administrators and officers, spent 9 AD on the minutiae of provincial governorship - the process of turning Germany into a province. It was the setting up of governmental infrastructure, day-to-day diplomacy, the drudge of community patrolling and escort duty – all that went with a new province. There had been no military action to speak of. At the end of August, he closed up the summer camp at Minden on the River Weser, a couple of miles downstream from the historic Minden Gap. The campaign season was at an end and it was time to head back to his headquarters in Xanten. An Augustan camp was discovered in Porta Westfalica in the summer of 2008 in Barkhausen, a suburb of Porta Westfalica, near Minden-Lübbecke. The finds of what appear to be a marching camp, rather than a permanent structure, date to the reign of Augustus and his push into Germany in the last years of the first century BC and early AD. While archaeologists were careful not to proclaim that they had found Varus’ summer camp, it is, at least, a plausible identification. Varus sets out As far as Varus was concerned it had been a good year. The only fly in the ointment had been a warning he had received just before the army set out. Some days before departure, Segestes, © Stéphane Lagrange The battle Equipped for a march through the inclement weather of late-Summer northern Germany, the legionaries were well armed and armoured, but, tired and soaked, not in the best condition to defend themselves from the German hit-and-run tactics. This legionary is equipped with a combination of items evidenced by Augustan era sites, such as the Coolus-type helmet, the belt plates and a pilum reconstructed after an Oberaden find. a pro-Roman Cheruscan noble and later Arminius' (unwilling) father-inlaw, had come to Varus to warn him that Arminius was plotting to overthrow Roman rule. Segestes demanded that the plotters be thrown in chains immediately or at the very least that the governor be on his guard. Varus dismissed these demands out of hand. And why shouldn't he? He and Arminius had been constant companions throughout the summer. The Cherusci were not only allies and had given no sign of resenting the Roman yoke, but Arminius himself was a wellrespected and integrated leader. Arminius had been an officer in the Roman army seeing action somewhere in the northern Balkans during what are known as the Pannonian uprisings, the revolts that shook the empire after AD 6. The Roman historian Tacitus writes that Arminius “served… as commander of his fellow-countrymen” (Annals 2.10) the senior officer of an auxiliary corps. He clearly distinguished himself. Arminius’ service record was significant enough for him to have earned not just coveted Roman citizenship but promotion to equestrian status, the admired middle class. The rejection of Segestes’ intelliAncient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 53 53 17-05-2009 17:50:41 The battle gence report hides a broader Roman blunder. Varus misunderstood not only the extent to which Germany was in any sense pro-Roman or even pacified, he completely failed to appreciate the potential for unity among the Germanic tribes. After the dinners and the close comradeship, the idea of betrayal never once crossed Varus’ mind. Arminius' trap was sprung with a finesse bordering on genius. He had organised an uprising within the fledgling province to draw the Roman army out. This was a subtle manoeuvre. It had to be a significant enough incident for Varus to feel he had to lead the army personally to put it down, but not so serious a revolt to awake suspicions either that it was a trap or that it was a precursor to a more concerted national uprising. With the Angrivarii, whose territory was predominantly between the Weser and the Elbe, just north of the modern town of Hanover, primed to rise up, Arminius planned to ambush the Romans when they were off their guard. He reckoned that they could be overpowered easily while marching through what they believed to be friendly territory. As the Roman legions marched out, heading northwest, Varus was later to be criticised for not ordering the army to march in a state of full war-readiness. The train was scattered with civilians, men, women and children from the camp. As with so much that was written at the time, it is difficult not to see this as wisdom after the fact. It was a march through friendly, not hostile territory. The Roman army The subject of how many men Varus had with him on his fateful march has been endlessly debated. Velleius Paterculus states that “three legions, the same number of divisions of cavalry and six cohorts” (2.117) were involved. At face value that would give a figure of around 18,000 legionaries, around 900 cavalry and a further 3,600 allied auxiliaries. That would account for the figure of 22,500 men which is commonly bandied about. But it is extremely unlikely that all, if any, of the battalions were fighting at full strength. Surviving accounts of day54 to-day strength reports suggest a much lower figure. The report of a cohort which was found at Vindolanda camp on Hadrian’s Wall and dates to the end of the first century says that the first cohort of Tungrians from Northern Gaul was 752 men strong commanded by six centurions. Of those 752 men, forty-six were on secondment to the governor of Britain’s guard; 337 men and two centurions were at Corbridge, another camp on the Wall; and one centurion was in London on business unknown. It is impossible to read where the others were, but in the end, there were only 296 men left in Vindolanda under one centurion – of whom thirty-five were unfit for duty, either ill or wounded. That leaves 35% of the men on active service. This state of affairs is corroborated by a daily report from the third century on a detachment of soldiers found on an ostracon (pottery-shard) in Bu Njem in Tripolitania. Of the fifty-seven men stationed at the fort, more than half were away on exercises, sick, or seconded to other projects. None of these figures appear extraordinary for any army before or since. If one considers that some of Varus’ soldiers were out on patrol or policing duty in other parts of the province, even if one adds in the non-combatants who tagged along – women, children and slaves – a total figure for those who set out from Minden of under 14,000 would be well within the realms of possibility. Towards the end of the first day's march, Arminius and his auxiliaries, Varus’ vanguard, begged to be excused. As part of the advance team, they needed to get away, they said, to mobilise other tribal auxiliaries in support of the general and to clear the way for the Roman army. While those hostile to Varus have seen this as a negligent move on his part, it was procedurally common to allow the advance guard to go ahead to smooth the passage of the army. The general knew of the need for reconnaissance in territory like this and as his intelligence sources had failed to give him any advance warning about the tribal uprising, it was reasonable for him to expect Arminius to bring back more detailed information about what was happening on the ground. The problem was that the person he chose to act as scout, to inform and to warn him was the person plotting to attack and kill him. Arminius rendezvous-ed with his fellow conspirators who were waiting nearby. Although by the end of the revolt many, indeed most of the tribes of Germany were involved in the uprising, at this point we can only be confident of three: the Cherusci, the Bructeri, a tribe based between the Lippe and the Ems, and the Marsi, a much smaller tribe which lived south of the Lippe and east of the Rhine. After Arminius headed off late afternoon, it was time to build a camp. “Varus’ first camp with its wide circumference and the measurements of its central space clearly indicated the handiwork of three legions,” is how Tacitus describes it (Annals 1.61). Battle begins The attack came the following afternoon. Varus could not have known how widespread or perfectly choreographed the revolt was already. The detachments that had been sent to the various communities had already been massacred. According to Roman accounts, the terrain was difficult; more mountainous than Varus and his legions were used to and much more forested. Forward detachments had been engaged in clearing a path for the army. The weather had worsened as they headed towards the Wiehengebirge mountain chain making all movement difficult. A literary device? Perhaps, but while the difficulty of the terrain may well be exaggerated, anyone who has visited northern Germany in the autumn knows the account of the storms is plausible. The Roman force suffered its first defeat east of Kalkriese. The first assault came towards the end of the day when the soldiers, tired, wet and anything but alert were beginning to think of rest and their evening meals. An attack from all sides surrounded the army in the forest. An escape route, the way they had come, had been blocked off. The question of how large Arminius’ army was is complicated. With no reliable literary account as a starting point, it becomes a question of population Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 54 17-05-2009 17:50:41 The battle density. Excavations in Scandinavia suggest that three hundred soldiers could be recruited from fifteen hundred people (some fifteen villages of ten homesteads, each with ten inhabitants) the approximate population density for an area between ten and twenty kilometres in diameter. Arminius could easily have massed an army 15,000-strong, drawing on a mere 750 settlements. While these figures are conservative, they are broadly in line with other figures for German forces. The attack of German spears was murderously successful. Slighter than Roman ones, yet with shafts that ranged from one to three metres tipped with 10-20 cm metal heads, these were still formidable weapons, the more so as the Germans often used slings to give them both speed and distance. With Roman cavalrymen protected by shortsleeved, hip-length mail armour, the obvious initial target for the Germans was the horses themselves. Arminius knew that not only was cavalry effectively useless in a confined space, wounded uncontrolled animals could act to his advantage causing confusion in the Roman ranks. The Roman troops could make no serious defence. Under normal circumstance, the cavalry would have been deployed on either sides of the marching legionaries as protection. But this was impossible in a forest. And it was no easier for the infantry. They struggled because of the difficulties in the terrain, hampered by civilians and their baggage wagons. In the confusion and the rain, the number of casualties from friendly fire must have high. It is curious that Varus appears to have organised his train so badly. Gladius scabbard reconstruction with original fittings. It would have had leather covered facings, held onto the wooden core by two clamps which doubled as suspension points and the chape protecting the scabbard point. Certainly it was one of the more serious criticisms levelled against him by Roman authors. “The Romans were not proceeding in any regular order, but were mixed in helter-skelter with the wagons and the unarmed, and so, unable to form readily anywhere in a body, and being fewer at every point than their assailants, they suffered greatly and could offer no resistance at all.” Cassius Dio 56.20.5 Yet again the answer lies in the level of Varus’ faith in Arminius. It is impossible to say when it was that the general realised how misplaced this had been, but it was certainly not quite yet. There was no need for Varus to insist on war readiness, because he was marching through not just subdued, but actively loyal territory. Despite the assault and the shock that it caused, Varus maintained admirable control and presence of mind. He knew what he needed to do. He built a camp. A sign of how serious the attack had been is that Varus insisted that the baggage train be burned or abandoned along with everything that was not strictly necessary. But there is no reason to think that Varus believed that his army would not survive at this stage. He had bought himself a brief respite. There was little chance that the Germans would attack a Roman camp directly. As the senior commanders met that evening to form a plan of action, © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. Photo Christian Grovermann it is likely that they agreed to aim for a river, where the army could pick up transport to take it to Haltern and then down to Xanten. The second day The next morning, one day after the attack, the Romans left their camp and began the march towards the oakcovered slopes of the Kalkriese Berg. Arminius will have known with moderate certainty that this was the general direction his opponent would take. It is wrong to suggest that the Romans were being herded. This was pretty much the only option open to Varus, where the main West/East routes from the midWeser to the lower Rhine converged, avoiding more difficult terrain to the north and the south. Indeed, until 1845 it remained one of the main routes through the area and it is preserved on maps up to that time as the Alte Heerestraße (“the Old Military Road”). Generally speaking, this was farmed and cultivated terrain rather than wild and ancient forest. It was not the landscape of thick, dark oaks. At times, Varus would have looked out to see a damp agrarian landscape not unlike the Fens of England. It had been farmed for millennia while wetter, marshier areas were a source of pasture or used for timber. In landscape like this, Tacitus’ comment (Annals 1.64) that the Cherusci were “experienced at fen-fighting” begins to make sense. As they came round the Kalkriese Berg, the Romans approached a narrow pass called the Kalkrieser-NiewedderSenke, the mountain rising up a hundred and ten metres above the pass to the south, the Great Moor to the north. It would be difficult to think of a more perfect spot for an ambush. The analogy has sometimes been used that it is like a lobster pot that allowed the Romans in, but not out. The Kalkrieser-Niewedder-Senke is a narrow corridor, some six kilometres long and only one kilometre wide. But because of the high water table at the time, it was only passable at the edges, on the ridges of sand that had accumulated, some two hundred metres wide. At the same time, with the nearest Roman relief forces some hundred kilometres to the south, there was no chance of the alarm being raised. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 55 55 17-05-2009 17:50:41 © Carlos de la Rocha The battle Varus and his men had been harried all the way. The constant attack then retreat of the Cherusci began to take its toll. But the losses the Roman forces suffered there were minimal compared to what happened next. This is where archaeology adds another dimension of our knowledge. This is the site that has been found. Arminius renews the attack The Cheruscan commander had had the opportunity to line the pass with arc-shaped turf walls and sand ramparts that curve with the shape of the hill. Three have been found to date with a total length of four hundred metres. Speed was of the essence for him and his troops. From the construction and variety of materials used it is clear that they were built quickly with anything that came to hand (turf predominates where there was meadows, sand, at the eastern end and a mixture of turf, sand and limestone at the western end) all of which suggests that the work had taken at most a few weeks to complete. The style of build of the walls is peculiarly Roman, indeed when they were first discovered it was thought they were rapidly constructed Roman defensive positions. Arminius had learned the lessons of Roman engineering and warfare well. Despite the speed and crudeness with which they were constructed, these walls were massively effective. Some four to five metres wide at the base – something you can work out easily by measuring the space between 56 the drainage ditches that had been dug on the German side and the start of the Roman finds – they were not much more than one and a half metres high, though in all likelihood this was raised by a palisade. Arminius knew that if his men could attack a fragmented Roman tactical formation, they could beat it. For the Cherusci this was less about matching the Roman gladius than out-psyching the legionaries. The forest might help the tribesmen achieve surprise, but it was the basic organisation of the column that needed to be broken. Not only did the construction of the walls preserve the element of surprise for the Germans, it also managed to narrow the path, to guide the Romans into the dampest, most difficult part of the pass where the legionaries could be massacred when the Germans leapt out through the gaps they had left in the walls. Disintegration of the column It was now that the worst of the fighting took place and the greatest Roman casualties occurred. If the human remains that have been found at Kalkriese provide only a snapshot of the thousands that died, then it is a high-definition one. Virtually all of the human remains that have been found are of men of military age, between twenty and forty years old. All of their deaths come from offensive weapons, many of them from sword cuts. The Roman soldiers were cut down easily. Floundering through the pass it was impossible for them to form their famously impregnable legionary lines. Just as the previous day, the cavalry units hindered rather than helped. In trying to mount any kind of defence, let alone attack, both types of unit became entangled, and crashed into each other. Their disorganisation made it even easier for the German forces. Here native traditions had the advantage. Speed and agility were what counted and the chief hope of victory was a rapid, overwhelming attack. In the face of this assault, there was no time to draw on any of the known and trusted techniques to avoid ambush. The Roman soldiers had nowhere to run. They could not reform. Roman remains behind the wall in the drainage ditches suggest that some legionaries did go on the offensive, scrambling over the top to get at their attackers. Certainly the earth rampart, built without wooden supports, began to collapse even during the battle. From an archaeological point of view this was fortuitous as it protected finds, but in the heat of combat, the disintegration of the walls added to the confusion. Testimonies of battle The natural focus of the battle has been on the human element. But another dimension to our knowledge about the battle is added by the animal remains that have been discovered – the few mules that survived Varus’ burning of the baggage train. The remains of a mule were found in 1992 along with its pendants and the decorative glass Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 56 17-05-2009 17:50:42 The battle and from scavenging animals. But the series of finds is not limited to the foot of the Kalkriese mountain as might be expected of an army trying to push its way through the pass to safety. Traces can be found branching off, away from the main army, in a two kilometre wide strip that leads northeast-wards to the edge of the Great Moor. It is clear that one part of the army split off and tried to make a break for it along the sandbars through the boggy forest. It is tempting to ascribe this attempt to the flight of Numonius Vala. Varus’ legate, his deputy, in Velleius Paterculus’ account, did try to escape taking the cavalry with him. It is always dangerous to argue from a lack of evidence but there are remarkably few traces of cavalry and horses at the foot of Kalkriese Mountain. Were Vala’s actions cowardice and a loss of nerve or a calculated saving of skin? We shall never know. Paterculus, as a cavalry man himself, is damning, suggesting that Vala was deserting the legionaries, trying to reach the Rhine and the safety of the Roman zone. Certainly when Varus’ deputy left he was effectively deserting the legionaries. But it is also possible that he was acting on orders. The cavalry was a liability in the narrows of the KalkrieserNiewedder-Senke. For Varus to send Vala away might have seemed appropriate, though we are firmly in the realms of speculation here. Whatever the circumstances, he did not make it and his troops were slaughtered to a man. “Vala did not survive those whom he had abandoned, but died in the act of deserting them,” writes Velleius Paterculus coldly (2.119.4). End of the line The fourth day since they had left Minden brought no let up from the weather, if anything it got worse. The violent winds made throwing javelins impossible and rendered the surviving Roman archers useless. The legionaries could not even defend themselves properly. The rain had soaked through the leather of the heavy Roman shields into the wood, making exhausted and © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. pearls that had fallen off their mountings. The iron clapper on the bronze bell round its neck had been muffled with a handfuls of oats its owner had grabbed from a field while passing to keep them moving as silently as possible. A tangible sign of the state of extreme tenseness of the Romans who had survived the first day’s attack, it is also the analysis of the oats which has allowed archaeologists to date the battle to September. In the heat of battle the mule had broken free from its wagon, still wearing its metal harness, iron ring snaffles and iron rein chains. It fell in front of the wall which collapsed on top of it, preserving the remains. Another, almost complete, skeleton of a mule was found in 2000 at the western end of the wall. Frozen in the moment of death, its head facing west and feet south, jaws still clamped on the snaffle, the animal had tried to escape over the wall and broken its neck in the fall. The wall, there sand reinforced with sandstone, then collapsed on it, protecting its body both from plunder One of the mule skeletons found at Kalkriese near and under the collapsed wall as it was found on-site. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 57 57 17-05-2009 17:50:43 The battle ture? Ceionius, one of Varus' senior officers, decided to surrender. His colleague, Lucius Eggius, another legionary commander, had already died in battle. A wounded Varus decided to kill himself. Even this, the final gesture of the commander-in-chief did not pass Velleius Paterculus’ jaded eye without censure: “The general had more courage to die than to fight, for, following the example of his father and grandfather, he ran himself through with his sword” © Stéphane Lagrange Velleius Paterculus 2.119 After their general’s death, some joined Varus in suicide, others took their cue from Ceionius and surrendered. The manuscript of Cassius Dio breaks off in mid sentence, his account mirroring history. “To flee was impossible, however much one might desire to do so. And so, every man and every horse was cut down without fear of resistance and the…” Cassius Dio 56.22.1 Florus reports: “...the third eagle was wrenched from its pole, before it could fall into the hands of the enemy, by the standard-bearer, who, carrying it concealed in the folds round his belt, secreted himself in the blood-stained marsh.” (Summary of Livy’s ‘Histories’ 2.30). demoralised soldiers carry even more weight. It was perfect weather, however, for the Germans. Given their light equipment, the rain and the wind if anything made their guerrilla attacks easier. They could pick off the enemy and quickly retire before the sodden Romans were able to react. More to the point, Arminius was able to draw on fresh men keen for a fight. Overnight, the German ranks had been swelled by other tribes which ini58 tially had been cautious about throwing their lot in with Arminius. Ranks thinned, surrounded by Germans, with even the weather against them, Varus and his senior officers took their final, unimaginably difficult decision. With ever-strengthening German forces and two eagles already captured, it must have been apparent now that the Roman forces now had no chance of escape. They would never make it back to safety. What was worse, suicide or cap- Aftermath of battle The next day, only the fifth day since the battle started, there was no doubt that Arminius had won. It was time for the mop up operations to begin. Germanic troops looked to their wounds and began the honours for their own dead. Their weapons were carefully collected. It was important for burial rites that a soldier’s arms be buried with him, something that accounts for the lack of native weaponry found by archaeologists at Kalkriese itself. As for Varus, although his body had been partially burned and then buried by his adjutants, it was disinterred and mutilated by the vengeful Cherusci. The corpse was decapitated and Varus’ head was sent as a trophy to another Germanic chief along with an invitation to join Arminius in his war against Rome. Arminius now divided the eagles among his allies – rewarding those who had supported his campaign and supplied troops. In a last ditch attempt Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 58 17-05-2009 17:50:44 The battle GmbH. Photo Christian Grovermann. © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land to save one of the eagles, a Roman standard bearer had wrenched it out of the ground, concealed it in the folds of his belt and thrown it and himself into the marsh. It was a futile gesture. All three eagles were captured. That of Legion XIX was given to the Bructeri, the Marsi was given a second, the Chauci received the third, though it is not known which they were given. What is often ignored is the religious element to Arminius’ campaign. Blood sacrifice and mutilation of war captives was particularly prevalent in Germany and is clear in the way that Roman captives were treated after the battle. The eyes of some legionaries were put out and then after their death, the Germans nailed their heads to the trunks of trees. One legionary’s last sight was of the German soldier who had cut out his tongue. He held it in his hands with the words: “At last, you viper, you have ceased to hiss.” The Roman then had the further ignominy of having his mouth sewn shut. It is one of two grotesque vignettes preserved by Florus (both 2.30). Despite the chronicler’s love of tall tales, there is the sense that these anecdotes were passed down by one of the survivors. The other is the final heroic act performed by Caldus Caelius. Having witnessed the above, rather than suffer the same indignity himself, he seized a section of the iron chain with which he was bound and brought it down with such force upon his own head as to cause his instant death. Any hopes that Ceionius and other senior officers might have had that they would be spared or ransomed were soon dashed. In the adjacent groves the Germans soon set up their barbarous stone altars on which they had immolated tribunes and the first-rank centurions. That was the fate that awaited Marcus Caelius, the centurion of Legion XVIII whose tombstone now rests in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn, and Fabricius, another centurion whose name we know, if they were not already dead. What was going on was the construction of what was already a sacred site, in all likelihood to the Germanic god Donar. Later to became Thor, at the time of the battle Roman authors associated him with Hercules and his cult was centred in the Weser basin. Kalkriese was being constructed as a memorial to celebrate the defeat of the Romans. This is something that Arminius would have encouraged. The localisation of the battle would also celebrate him as the leader. It is in this light that we should see the discovery of Kalkriese’s best-known find, the seventeen centimetre tall iron cavalry face mask that has become the logo of the museum and site itself. It stares blankly out of every book on the subject. Originally covered with silver leaf, it is the oldest preserved mask of its kind found so far. Originally belonging to auxiliary cavalry from Gaul or Thrace, the feeling of intimidation that every viewer who sees it gets is deliberate. It was almost certainly placed against the wall. The Germans would have no use for such a ceremonial piece of armour, and after removing the valuable silver leaf, placed it there as a memento mori. Today there is no trace of this ritualistic aspect of the battleground. What archaeologists have found is the detritus, damaged items, pieces too small to scavenge or simply missed. The most valuable archaeological treasures have been found either because they lay protected under the collapsed wall where scavengers could not get them, for example, or where paleo-botanical analysis has suggested that the grass was too long and they were hidden from German eyes. Even though most of what has been found has been smaller items, they still give a sense of the scope of the disaster: helmets, bosses of shields, random pieces of armour and of belts. And of course there are the weapons themselves. The sheer variety highlights the number of troops that were involved: arrow heads and swords, slingshot and spears. Yet the anonymity of the battlefield is occasionally lifted. One fastener for armour is identified as “Belongs to Marcus Aius, Cohort I, Century of Fabricius”. His name is punched into one fastener with a sharp implement and scratched onto its partner which was found nearby. After the tactically brilliant and definitive ambush at Teutoburg every Roman settlement east of the Rhine was overrun. Even nascent towns like Waldgirmes, an assimilated civilian settlement in the Lahn Valley discovered in 1993, were either abandoned or destroyed. The Germans wanted to erase any trace of the hated invaders. Chain mail fasteners found at Kalkriese. The back of each is inscribed with a text proclaiming that they belonged to a Marcus Aius of the first cohort, in the centuria of Fabricius. Sadly it is not known which legion this soldier served in. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 59 59 17-05-2009 17:50:45 © Igor Dzis AW special mei09.indd 60 17-05-2009 17:50:50 The battle Our knowledge of how widespread this destruction was is growing all the time. The very recent discovery of Augustan coins near Paderborn suggests that Romans there suffered Arminius' anger too. As Cassius Dio pointedly notes, it was the actions and defence of one camp which prevented the Germans from either crossing the Rhine or invading Gaul. It does not matter that it is doubtful whether Arminius would have ever considered pushing into the West. At a time of disaster like this the Romans needed a hero and they found it in Lucius Caedicius, the camp commander of Aliso. Preparations on the limes The modern site of Aliso has never been formally identified, though it has been equated with the Roman camp at Haltern on the River Lippe since 1900. Certainly Haltern was assaulted and burned to the ground that autumn. By the time that Varus had made his last stand, Caedicius might already have heard from scouts or refugees about what had happened to his commander and to his colleagues Lucius Eggius and Ceionius. Caedicius was not the kind of man to panic. He was a primus pilus, the commander of the first cohort and the legion’s most experienced and senior soldier. Although the literary sources do not mention which brigade he was from, it is possible that he was from Legion XIX. We surmise that the legion was stationed there after the discovery of an ingot with CCIII L.XIX ("203 lbs Legion XIX") carved into the lead (shown elsewhere in this magazine). Caedicius appears to have had enough time to get the civilian encampment settled in the safety of the eighteen hectare camp. Initial attacks were repulsed by archers who lined the wooden walls of the fort, supported by ballistae, artillery which could throw bolts and stones. The archaeological evidence suggests that despite this aerial bombardment, A highly decorated Roman centurion goes down fighting. An officer such as Marcus Caelius would owe it to his rank and imperial awards to show the best possible example. the double ring of ditches which protected Haltern – two and a half metres across and three metres deep – was soon to fall to the Germans. They seem to have attacked the south gate, filling up the ditches with hastily cut turfs. That the remains of what is clearly a hastily erected barricade has been found suggests that the Romans were able to fight off even this onslaught and push the Germans back. After the initial attacks failed, it was apparent to the Germanic soldiers that they had little chance of taking the camp by normal means. Certainly Cassius Dio comments that “they found themselves unable to reduce this fort, because they did not understand how to conduct sieges” (56.22.2). With what they must have presumed was a Roman relief force on its way, the Germans partly withdrew, deciding instead to guard the road to Xanten, hoping to catch Roman refugees in an ambush as they left. In its isolation, food soon began to run low which is hardly surprising as the camp was now holding a large number of both military and civilian personnel. Caedicius tried a desperate trick. He led German prisoners round the store-houses in the camp, then cut off their hands and set them free. As he had hoped, they reported back to their tribal compatriots that there was little chance of starving the Romans out as they had enough food to last them. With no sign of assistance coming from Xanten, Caedicius waited for an autumn storm, then crept out. The Romans managed to escape, but Haltern itself went up in flames. The excavations show how rapidly they had to move. Individually they add little, taken together they provide a montage of the disaster which befell the town. The arsenal was found with unused arrow heads and a thousand ballistae bolts. A coin horde was found of 185 silver denarii and one gold aureus – the savings of a legionary. It had clearly been hidden and never recovered. A cellar was found with some thirty pots left untouched. A doctor may have survived, but he left his medicines behind. The lead lid of a jar has been found, the words ex radice Britanica [sic] (“from the British root”, according to Pliny a cure for scurvy) still clear to see. Rome’s response Rome’s reaction to this military debacle was massive mobilisation. The Rhine armies were boosted from five to eight legions under the command of Tiberius throughout AD 10 and 11. A new chapter began in AD 13 with the appointment of Germanicus, Tiberius’ nephew and heir to the throne, as governor and commander-in-chief. His commission was to consolidate his uncle’s work, to repair the damage caused by Varus and to pursue and punish Arminius. In all three he was an abject failure. It took Germanicus three years before he defeated Arminius at the Battle of Idistaviso, an unidentified site along the River Weser, possibly somewhere near Minden. Arminius was injured in the first moments of the battle and the Germanic tribes were routed. A subsequent engagement resulted in further German losses. Germanicus’ plea for one more campaign fell on deaf ears (Emperor Tiberius had a campaign in Armenia to fund) and he was recalled to Rome. Yet on that inconclusive note, Roman involvement on the eastern side of the Rhine ended. His defeat at the Battle of Idistaviso marked the beginning of the end of Arminius’ power. The Cheruscan was faced with a civil war and was soon murdered by a member of his family under somewhat murky circumstances. We do not know who killed him or how he died, though it is a tidy coincidence of history that the same year that saw the death of Germanicus saw his death too.n Adrian Murdoch is a journalist and an ancient historian. He is the author of several books on the classical world including Rome's Greatest Defeat: massacre in the Teutoburg Forest. Further reading - A. Murdoch, Rome’s Greatest Defeat: Massacre in the Teutoburg Forest. Stroud 2008 - P. Wells, The Battle That Stopped Rome: Emperor Augustus, Arminius, and the Slaughter of the Legions in the Teutoburg Forest. London 2005 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 61 61 17-05-2009 17:50:51 Aftermath After Varus Rome and the Rhine When the Romans first encountered Germanic peoples in the late 2nd century BC, the latter destroyed whatever Rome could put in their way. It required a new army under the ‘New man’ Marius to erase the stain. More than a century of confrontation and coop- about what to do when Arminius destroyed Varus’ army. After Marius, the Germanic tribes next enter Roman history when Julius Caesar became embroiled with them in his Gallic Wars. He fought against Germanic mercenaries in Gaul, mounted expeditions across the Rhine, and enlisted them as soldiers himself for service against Vercingetorix and in the Civil war. It was he who arbitrarily fixed upon the Rhine as the border between Celtic and Germanic peoples, though the actual differentiation is often difficult to make since Germanic tribes lived west/south of the Rhine, and Celtic peoples lived east/north of the Rhine, and there were many ‘mixed’ tribes. The next incursion was in 39-38 BC, when Augustus’ closest friend and colleague Agrippa campaigned across the Rhine at the request of the tribe of the Ubii, who were being pressed hard by another, the Suebi. Agrippa settled the former on the western bank, founding Oppidum Ubiorum which would later become an official colony at the behest of Claudius’ wife Agrippina, and be renamed Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, and later still Cologne. In 16 BC, a portent of things to come occurred – the Clades Lolliana (“Lollian disaster”). The governor of Belgica, Marcus Lollius was defeated by the raiding Germanic Sugambri people with at least two legions somewhere in the Meuse valley. Legio V Alaudae lost its Eagle, a terrible disgrace. This was so serious that Augustus himself set 62 off for Gaul, but fortunately Lollius himself recovered the situation, defeating the raiders before they could get back over the Rhine, and apparently recovering the standard as well as obtaining hostages. Although still retaining the favour of Augustus, Lollius would never again command a Roman army. At this time, it is evident that Augustus saw no reason why Rome should not continue to expand, and the completion of the conquest of Spain in 19 BC released numbers of troops for further conquest on the Northern frontiers. Augustus himself stayed three years planning the invasion, until 13 BC. He then handed the matter over to his adoptive son Drusus and returned to Rome. It is clear that the Romans intended to turn the vast area between the Rhine and Elbe into a province. Obviously the inhabitants of the area did not all agree and resistance was soon to come. Further east the confederacy built by Maroboduus, chief of the Marcomanni, with its centre in Bohemia, was seen as a threat. In 5 AD the largest campaign force yet assembled would deal with this threat. The rivers were once again of paramount logistic importance. The army of Germania Superior (Legio I Germanica and V Alaudae) marched east along the river Main. Simultaneously, Tiberius would march to the north from the Danube, gathering eight legions at Bratislava. Five other legions would converge from the Elbe. It was the larg- © Karwansaray BV eration with these belligerent peoples shaped Roman ideas Bronze bust of Tiberius (42 BC – AD 37). He had had a very impressive military and administrative career before he finally succeeded his adoptive father Augustus as emperor. His subsequent problematic relations with the senate ended up damaging his historical reputation. Now in the National Archaeological Museum, Madrid. est military operation planned by Rome to date, larger than the army Caesar had conquered Gaul with, and involving almost half of Rome’s total forces. The campaign was sidetracked by an insurrection however. Pannonia and Dalmatia broke out into revolt, encouraged no doubt by the absence of its Legions. With a possible disaster threatening, Rome offered a hasty peace to Maroboduus. Tiberius took most of the army east to put down the revolt, while Varus continued the pacification of the western German area. He set out to gather taxes and impose a civil administration and justice system in the newly reduced lands. The next four years saw Tiberius at his best as a general subduing the Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 62 17-05-2009 17:50:53 AfTermATh revolt in Illyria. As he was about to celebrate his well-won triumphs, the terrible catastrophe to Varus and his three legions in AD 9 became known, turning the celebration into sorrow, and eventually produced a change in Roman policy towards Germania. Setback for Rome The survivors from the Clades Variana made their way back to a fortress called ‘Aliso’, probably Haltern. There they stubbornly held out through the winter against the victorious tribes under Arminius, ultimately breaking out and escaping. From Mainz, the nephew of Varus, Lucius Nonius Asprenas immediately sent his Legions, I Germanica and V Alaudae hurrying north and occupied the fortresses of Cologne and Xanten. This and the heroic Aliso fortress defence prevented the Germanic tribes from invading Gaul, thus limiting the effects of the defeat. At the same time, Tiberius marched from the Danube to the Rhine with two legions XX (later Valeria Victrix) and XXI Rapax and prepared for Rome’s inevitable retribution. Much is made of Suetonius’ report of Augustus’ reaction. The old emperor supposedly wailed: The immediate effects were serious enough. The loss of three Legions from the existing 25, or some 12 percent of Rome’s legions, was a heavy blow. Augustus did not re-raise legions XVII, XIIX and XIX, probably for superstitious reasons, instead raising Auxiliary cohorts consisting of Roman citizens. However, the manpower reserves of the Empire were ample, and the losses were fairly quickly made up. A more serious setback would not become apparent for many years yet, and that was the loss of the ‘province’ of western Germany between the Rhine and the Elbe, only newly won after much effort and campaigning by Drusus and his brother Tiberius, and, as was now apparent, not fully ‘pacified’. However, Augustus’ empire as a whole was largely unaffected; but the defeat ultimately caused Augustus at least, to re-think continued expansion, and in his will he recommended to his heirs that they stay between the then existing boundaries of the Empire. “He was so greatly affected that for several months in succession he cut neither his beard nor his hair, and sometimes he would bang his head against a door, crying ‘Quinctilius Varus, give me back my Legions!’ and always kept the anniversary as a day of deep mourning.” Seutonius, Augustus 23.4 The tombstone of Publius Clodius, a former soldier of Legio I Germanica which came north after the Varian disaster. This tombstone has been dated to approximately AD 40, which together with Clodius’ 25 years of service may mean that this soldier served during the campaigns of Germanicus. Now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn. AW special mei09.indd 63 © Karwansaray BV Rome strikes back During the winter following his masterstroke, Arminius, mindful that he had only damaged a powerful Rome, worked hard to hold his coalition of tribes together. He also sought to draw the tribes further east under Maroboduus into an alliance – sending him Varus’ head. But Maroboduus had seen what powerful forces an angry Rome could bring to bear, and refused the alliance, sending Varus’ remains on to Rome where Augustus gave them honourable burial in his own family tomb. Nevertheless the Langobardi and Semnones joined Arminius’ coalition, even though they owed their allegiance to Maroboduus. During the next two years Tiberius embarked on a cautious policy. While guarding the Rhine well, he took expeditions into trans-Rhine Germany, but attempted nothing decisive or rash, while Augustus recruited and trained auxiliary cohorts of Roman citizens – an unusual measure - to replace the lost manpower. In AD 11, Tiberius returned to Rome, in effect to become co-emperor with the aging Augustus. He finally got to celebrate his Illyrian Triumph, postponed because of Varus’ disaster and duly ascended the throne upon the death of Augustus in AD 14. When he left Germany, he handed over command to his nephew, and adopted son, Germanicus, who had the eight legions of Upper and Lower Germany under command, together with their associated auxiliaries, something of the order of 70-80,000 men. Unfortunately, upon the accession of Tiberius, the legions of the Rhine and in Pannonia revolted against their service conditions, despite the popularity among the military of Tiberius. Tiberius’ son Drusus – Drusus the Younger – quelled the mutiny in Pannonia among the Danube legions, while Germanicus dealt with the Rhine Legions, resorting to playing on the soldier’s sentiments by displaying his wife and little son Gaius, who was nicknamed Caligula. (“little boots”) by the soldiers, and refusing to accept the Army’s offer to make him Emperor. After quelling the mutiny, the troops were still in a dangerous mood, and Germanicus decided they should vent their frustrations across the Rhine. He built a Ancient Warfare 63 17-05-2009 17:50:56 Aftermath bridge and launched a raid against the hapless tribes across the river, mainly the Marsi. Twelve thousand legionaries accompanied by thirteen thousand auxiliaries and four thousand or so cavalry crossed the bridge, split into four columns and proceeded to ravage the countryside. No mercy was shown. When they returned to winter quarters, their bloodlust and frustrations satiated and laden with booty, morale was high and the mutiny forgotten. A Triumph was decreed for Germanicus, but the war of revenge was far from over. Arminius was not to be allowed to boast of his victory over Varus. The Cherusci and Chatti were to be made to pay for their brief success. During the next campaign season Germanicus gave Aulus Caecina Severus four legions (20,000), around ten cohorts of Auxiliaries (5,000 or so) and a large number of tribal levies from the East side of the Rhine. Germanicus himself took the other four legions (20,000), twenty cohorts of Auxiliaries (10,000) and more levies. The Chatti were completely surprised. The elderly, women and children were killed or captured and sold into slavery in large numbers. Some tried to surrender, but were refused. Germanicus burnt their capital, the town of Mattium. Smoke from fires rose across the landscape. The Cherusci were unable to help, being held at bay by Caecina. It was cause for great satisfaction when the Eagle of the XIXth legion was recovered. Germanicus then went to the battlefields where Varus and his men had died, and survivors pointed to where the standards had been taken, the senior officers and Varus had committed suicide and so on, among the whitened piles of bones. The harrowing groves where Roman officers had been sacrificed were viewed, and the army of Germanicus gathered up the ghastly remains and gave them a proper revered burial. Finally, a turf mound was raised, some six years after the massacre. Tacitus brings all the drama to the fore: “The scene lived up to its horrible associations. Varus’ extensive first camp, with its broad extent and headquarters market out, testified to the whole army’s labours. Then a half-ruined breastwork and shallow ditch showed where the last pathetic remnant had gathered. On the open ground were whitening bones, scattered where men had fled, heaped up where they had stood and fought back. Fragments of spears and of horses’ limbs lay there – also human heads, fastened to tree-trunks.” Tacitus, Annals I.61. However Arminius refused battle, giving ground and posting ambushes. At the end of the campaigning season, the Roman army split up and dispersed to its winter quarters. The army of Caecina had to cross a long causeway across the marshes known as the ‘long bridges’ (see p.8), but Arminius, unburdened by baggage, got there first. The Romans had to repair the causeway, the Germans diverted streams to flood it. Arminius exulted, telling his men that here was another Varus come to the slaughter. The Germans grew bolder and tried to assault the Roman camp. Caecina’s men sallied forth and slaughtered the German tribesmen. Arminius barely escaped. Frustratingly, after two campaigning seasons, Arminius was still free. The Romans had been handicapped by long baggage trains which had to be defended. The supply of baggage animals from Gaul was exhausted – an indication of the effort Rome was putting forth, with one third of its military forces concentrated on the Rhine. Germanicus decided the next campaign in AD 16 would be launched using the fleet, both to transport part of the Army and to bring up supplies. Strategic surprise could be obtained by launching into Germany from the sea, rather than across the Rhine. Unfortunately the strategic surprise did not come off, because of an error in the landing site, which meant much time was wasted building bridges. Germanicus eventually came faceto-face with Arminius across the Weser River. The Roman prudently decided he needed to secure bridges before crossing and fighting. The cavalry were sent across various fords, with the Batavians under their chief Chariovalda crossEvery time an eagle was recovered, it was an opportunity for the reigning emperor to display his prowess. Augustus ordered the return of Crassus’ standards by the Parthians displayed on the cuirass of his, now famous, Prima Porta statue. Having little military experience himself, Caligula, son of Germanicus, had this coin struck to show off the return of the third of Varus’ eagles, proudly proclaiming signis receptis (“return of the standards”). 64 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 64 © The P. Lindsay Powell Collection, photo Michael V. Craton. 17-05-2009 17:50:57 © Carlos de la Rocha Aftermath © Karwansaray BV Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 or 16 BC – AD 19) was adopted by Tiberius in AD 4. He served under Tiberius in Pannonia and Germany before commanding the great expeditions to re-establish order among the tribes. After his triumph of AD 17, he was sent east where he died, a very popular member of the Imperial family, in AD 19. Now in the Louvre, Paris. ing where the current was strongest. The Cherusci feinted a retreat and lured them into an ambush on a level space, surrounded by wooded hills. The Batavians, outnumbered, and surrounded, were inspired by Chariovalda who personally led an escape attempt, but was killed along with many of his chieftains and retinue while doing so. The breakout succeeded however, and the arrival of other Roman cavalry saved the day. Germanicus duly crossed the Weser, and was advised by deserters that Arminius had chosen his battleground, and meant to fight. Furthermore, a surprise night attack was planned on the camp. Arminius tried primitive psy-ops by having a Latin speaker ride up to the camp and promise a wife, money and land to any who deserted. There were no takers – the Romans shouting back that they would help themselves to those things after beating the Germans. Shortly after midnight, the expected ‘surprise’ attack materialised, but the ramparts were fully manned. Battle with Arminius The next day, the Germans marched to a level area which Tacitus calls Idistaviso, (which some translate as ‘Valley of the Maidens / Valkyries’) within a broad bend of the Weser, near modern Rinteln. The river was their left boundary, and they were bounded on their right by a forest, which had clear ground beneath the trees. The Roman army consisted of some 2,000 Praetorians, detachments of eight Legions amounting to some 28,000 men, perhaps 20,000 Auxiliaries, plus something like 5,000 German allies, including Batavians. There were also some 6,000 heavy cavalry, again including Batavians and perhaps 1-2,000 horse archers. The army thus numbered over 60,000 less Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 65 65 17-05-2009 17:50:59 Aftermath into the front line of Auxiliaries, but could not break through to the bowmen, in Tacitus’ words again (ibidem): “..and it would have broken through if the standards of the Raetian, Vindelician and Gallic Auxiliary cohorts had not barred the way.” © Karwansaray BV It was all over in an hour or two. Arminius, though wounded, contrived to escape on horseback, having smeared blood over his face to avoid recognition. Tacitus words again (Annals 2.18): “It was a great victory, and it cost us little. The slaughter of the enemy continued from midday until dusk. Their bodies and weapons were scattered for ten miles around.” Silent testimony to the disastrous journey back across the Wadden Sea. A Coolustype helmet found on the beach of the Dutch island of Texel. Like many helmets, it has been marked on the neckpiece by its former owner: “VI.HIR.#.FIRON.PI”. The text is mystifying to say the least, however. The usual explanation is that VI HIR should be read as VI Hirundo, which would indicate a ‘six’ (a hexere-type warship) named “swallow”. That would be the only example of a Roman warship named after a bird and only the second known ‘six’ from the entire imperial era. Perhaps alternately then, VI is a marker for the unit to which the soldier belonged. a camp-guard and detachments. Arminius commanded a coalition of tribes, the largest three of which were his own Cherusci, the Langobardi and the Semnones. We do not know their numbers, but we might guess that they were fewer than the Romans from their care to guard their flanks, but sufficiently numerous to make Arminius believe he could challenge Germanicus in open battle. At a guess then, he may have had as few as 30,000 men, or as many as 40,000. The Cherusci occupied the centre, on a low hill. Due to the cramped battlefield, Germanicus drew his army up in three lines, the first consisting of Auxiliaries and allied / levied German tribesmen, with a line of archers behind. They were backed by the Praetorians and four Legions, flanked by the pick of the cavalry on their left stretching into the wood and 66 a third line, consisting of the remaining four Legions and the remaining auxiliaries, flanked by more cavalry and horse-archers on their left. The Germans charged impetuously with a roar. Germanicus ordered his first line of cavalry to outflank them through the trees, and the second line were to ride around and attack the rear. The left and right of the German line quickly broke and as Tacitus tells us (Annals 2.17): “Two enemy forces were fleeing in opposite directions, those from the woods into the open and those from the open toward the woods.” The Cherusci in the centre, making the most of their downhill impetus, and inspired by Arminius, slammed Many drowned trying to escape across the Weser, others, having taken shelter from the cavalry by climbing trees, were shot by the archers for sport. It may be that Tacitus exaggerated the Roman success, for Arminius was able to regroup, and gather fresh troops. He had learnt now that he was no match for the Romans in open battle, and so reverted to ambush tactics. Sometime later, Arminius selected a site on the boundary of Cherusci and Angrovarii territory, which was marked by a raised earthwork. He picked a spot having similarities to the Kalkriese site – a narrow space between river and forest. The infantry manned the earthwork, while the cavalry took cover in the woods, so as to take the Romans in the rear when they met the obstacle of the earthwork. But Germanicus was no Varus, as Tacitus says (Annals 2.20): “He knew their plans, positions, their secret as well as their visible arrangements.” This was doubtless due to light cavalry reconnaissance, and the local knowledge of his Batavian and German allies. The Roman infantry split up, part entering the wood and driving Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 66 17-05-2009 17:51:00 Aftermath the German cavalry off, the other part attacking the earthwork. These were initially rebuffed, so Germanicus withdrew the legions, and ordered the archers and slingers to provide covering fire, along with bolt-throwers. A second assault took the earthwork. Germanicus personally led a charge of the Praetorians into the wood. Tacitus again (Annals 2.21): “Either Arminius had been through too many crises, or his wound was troubling him: he did not show his usual vigour” Germanicus tore off his helmet to be recognised, ordering his men to spare none. No prisoners. They were to kill and kill. Once again, a massacre ensued until nightfall, but again Arminius escaped. The Romans continued on their way back to winter quarters, part embarking once more by ship, but a storm ravaged the fleet and caused many casualties. Some were even carried to Britain. Rumours that the entire fleet was lost encouraged more fighting, repressed by Germanicus with harsh measures. A second eagle was recov- The campaigns end Varus was now well and truly avenged, some seven years later. Germanicus felt one more summer campaign would recover the trans-Rhine province. But it was not to be – Tiberius pointed out that he himself had achieved more by diplomacy than force. If there had been great successes, there had also been costly misfortunes. The chastened Cherusci could be left to their own internal disturbances. When Germanicus still protested, Tiberius added that he must leave something for his brother Drusus to have a chance to earn a Triumph – he was to return to Rome and celebrate his own. This represented a turning point in © Karwansaray BV Cast of the ‘Gemma Augusta’, a cameo celebrating the victories over the Germans. Tiberius sits togate with Victoria, while Germanicus stands next to them wearing armor. On the lower half, Roman soldiers set up a victory monument among defeated barbarians. Cast in the Glyptothek, Munich, original in Vienna. ered and ultimately, later still, the third would be too. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 67 67 17-05-2009 17:51:02 © Karwansaray BV Aftermath Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus, known to history as Caligula (AD 12 41), accompanied his popular father on his campaigns. His terrible reputation with the senatorial elite ensured that his military accomplishments were downplayed and ridiculed. Now in the Louvre, Paris. Rome’s policy on its northern frontier. Perhaps, as Tacitus said, it was jealousy of Germanicus’ military glory that prompted this change, but it is unlikely that this was the motive of the cool and calculating Tiberius. Tacitus offers the explanation that Germany simply was not worth the sustained effort required to permanently subdue it. That cannot be entirely true, however. The Taunus mountains had a goldmine and both the Lippe and Main 68 valleys were very fertile. But Germania lacked the developed agriculture of Gaul or the massive minerals of Iberia. It is true that long campaigning with fully one third of Rome’s military might had brought very little actual gain. Perhaps Tiberius decided that indirect control was just as efficient as boots on the ground. The Rhine was to become the ‘de facto’ frontier, but not entirely. The Legions came back to the Rhine it is true – two at Cologne, in the territory of the Ubii, two at Xanten, two at Mainz, and further south one each at Strasbourg and Windisch. However, beyond the Rhine, forts were maintained in the Main-Wetter area and further north, beyond the Rhine mouth, Velsen remained occupied and used down to at least Claudian times. Among the Frisians, in the northern Netherlands, Drusus had imposed a tribute in 12 BC, which was continued – proof of indirect control – provoking a rebellion in 28 AD, and a Roman fortress, probably Velsen, was attacked. Regardless, the frontier remained relatively quiet while the German tribes bickered and fought one another. Arminius, having eluded the Romans, and after also having defeated Maroboduus and driven him into Roman exile, was murdered amidst internecine power struggles. For the rest of Tiberius’ reign, the Rhine frontier remained relatively quiet. A new policy Our sources unfairly ridicule the military efforts of Tiberius’ successor Gaius “Caligula”, son of Germanicus. He found it necessary to visit the Rhine frontier to put paid to a plot to overthrow him, but his visit to the frontiers where he spent his childhood are derided, with him ordering the troops to gather sea-shells as symbols of his ‘Triumph’ over Ocean itself. However, tombstones from the Mainz area suggest serious fighting on the Upper Rhine took place and it would appear that serious preparations for the invasion of Britain were undertaken. The logistics route, as ever, was dependent on river systems, in this case the Rhone, Saone and Rhine route. Bases at the Rhine mouth area were needed and built at Albaniana (Alphen aan de Rijn) and Praetorium Agrippinae (Valkenburg), with increased activity at Fectio (Vechten) – all in the Netherlands. These were previously attributed to Claudius, but archaeology has now established they were constructed by Caligula around AD 40. It now appears Claudius took over invasion plans which were well advanced, and profited from his predecessor’s plans – acceding to the throne in AD 41, he was able to launch a full scale invasion in AD 43. Later, around AD 47 a new commander, the celebrated disciplinarian Corbulo, settled the fractious Frisii, built a fort in their territory to ensure obedience and started to reduce the area to a province until the Emperor Claudius, who had his mind on Britain, and not distractions across the Rhine, ordered him to desist. During Claudius’ reign and after, the two-legion fortresses, launching platforms for offensive campaigns, gradually transformed into more spread out and defensive single legion bases, and forts and fortlets sprang up every 7-8 kilometres/5 miles along the lower Rhine especially. Various Emperors tried different frontier fortification systems, but they were all defensive in nature. The Rhine had transformed from a springboard for further conquest, to the defensive outer limits of the Empire, but, unlike Hadrian’s wall in Britain, the frontier had not been planned and built, but rather evolved over a century or so from the first watchtowers in Augustus’ time, to the chain of stonebuilt forts of Flavian and later times. Nor was the Rhine merely a boundary, but rather a central highway for middle Europe. The defences controlled traffic into the empire, but perhaps even more Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 68 17-05-2009 17:51:03 © Karwansaray BV Aftermath Legio XXI Rapax was moved north to Xanten after AD 9 and remained there for three decades when it was relocated back south. Though his full name is now illegible, this memorial to a soldier of that legion is the only epigraphic evidence for its presence in the area. Now in the Römermuseum, Xanten. to this day, for the peoples of Europe east of the Rhine speak ‘Germanic’ languages, while those west of it speak ‘Romance’ Latin based languages. n ensured western Germany, if no longer a province, remained quiet for 50 years. Peace would be disturbed in AD 69 – the year of the four Emperors – when the Batavii, allies of Rome and hence still strong, sought to take advantage of Rome’s civil wars and rebel. They were ultimately unsuccessful and Germany would pose Rome no more problems until new confederations arose a hundred years later in the 160’s – the Marcomanni and Alamanni - to trouble the soldier-philosopher Emperor Marcus Aurelius not just on the Rhine, but along the Danube too, in wars of even larger scale. In the longer term, northern tribes migrating southward such as the Goths and Vandals would cross the river frontiers of the Rhine and Danube and play their part in the downfall of the Western Roman Empire, and it may be said that the Clades Variana echoes Paul McDonnell-Staff is an Australian and English lawyer who has also had a lifelong passionate interest in ancient warfare. He has researched, travelled extensively, and written professionally about the subject since the 1970’s and is currently writing The Roman Conquest of Spain for Pen & Sword books. important, they controlled traffic along the great river. It never lost its great logistical role. Conclusion The immediate aftermath of the ‘Varian disaster’ had been understandable shock – no-one, bar Romans themselves, had succeeded in destroying a Roman army of several legions since Carrhae in 53 BC when the Parthians destroyed Crassus. In the short term Arminius’ success simply led to a great deal of bloodshed among the tribes of western Germany - the Cherusci and Chatti, and the lesser tribes of Marsi and Bructeri, Angrivarii and so on until Tiberius’ change of heart in AD 17, and afterward internecine warfare between German tribes ensured that in the medium term their names would disappear from history, significantly enough. The destruction wrought by Germanicus Further reading - G. Webster, The Roman Imperial Army 3rd ed. Oklahoma 1998 - L. Keppie, The making of the Roman army London and New York 1998 - Y.Bohec, The Imperial Roman army 2nd ed. London and New York 2000 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 69 69 17-05-2009 17:51:04 THE BATTLEFIELD Looking for Varus The quest for the Teutoburg forest When Tacitus’ Annals and Germanica first appeared in print around AD 1500, these writings brought about a new interest. Contemporary Germans desired to know about their ancient ancestors and their fight against mighty Rome. Very quickly the battle of the Teutoburg Forest became a symbolic mark in German history that was studied, used and abused for all manner of purposes. It goes without saying that this attention raised one big question: where exactly had these events taken place? © Peter Nuyten By Jasper Oorthuys Bird’s eye view of the battlefield: pushed forward by the mass of the Roman column behind it, forward elements of Varus’ army are thrust into the narrows between the hills, and the swamp on the other side. Attacked by German warriors from behind their wall, the column is overwhelmed and torn apart. 70 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 70 17-05-2009 17:51:08 The bATTlefield route with the story of a revolt among the Angrivarii. Unsurprisingly, theories about the location of the battle abounded – some 750 locations were proposed at one time or another – from the moment the historical events caught the public eye. In the 19th century, one theory gained the upper hand and the location seemed settled. The area around Detmold, Germany, got the official stamp of approval in the shape of a 50m tall statue of “Hermann”, completed in 1875. A noble coin collection There was very little to go on. As Jona Lendering argues elsewhere in this volume, some of the geographical descriptions in the narrative sources pertaining to the battle are downright undependable. Those that aren’t, are just vague. The former problem was not always recognized, while the latter is unhelpful. What is left, is the Latin name given by Tacitus: Saltus Teutoburgiensis, usually but possibly incorrectly translated as Teutoburg Forest. It may be misleading if you’re looking for a geographical feature, but the name has come into common usage so much so that it now is the de facto name of the battle. The other clue was that the battle must have taken place somewhere between the site where Varus spent the Summer of AD 9 and the fortresses on the Rhine and Lippe. The former was somewhere on the Weser, probably at or near Minden (see text-box). With a possible beginning and a known end and with knowledge of local geography a likely Roman route could be reconstructed. Frustratingly, there are several possibilities. The question is whether the Romans would have marched down the Weser and then crossed to the closest point on the Lippe, or would they have taken the shortest way and cut across, straight to Haltern? However, even if the standard route were known, that would only have limited use in this quest. After all, Varus was induced to change his course, away from his usual Still, not everyone was satisfied. In fact, the German historian Theodor Mommsen, one of the most important ancient historians ever, pointed to a series of coins found on the estate of a German nobleman some way to the west. The Von Bar family had owned large areas of land to the east of Osnabrück for almost 1,000 years. The farmers who worked their lands had found Roman coinage with some regularity, which had ended up in the family’s collection. Unfortunately, the family did not know exactly where the coins came from, or at least, they kept Mommsen in the dark. He, therefore, was not able to found his theory on any firm evidence. What was important to note, was the proportion of the denominations in the collection. They consisted largely of silver denarii – in other words: army pay – some gold aureii and some copper coinage. Also they all dated to the reign of Augustus. Without more information about the find spots of these coins, even Mommsen could not prove anything other than that these were traces of an Augustan era Roman army. Considering the history of northwestern Germany in that period, that is hardly a surprising conclusion. Fortunately, the coins were fully described and catalogued before they went missing, probably stolen, at the end of WW2. Enter Major Tony Clunn in the 1980s. An amateur archaeologist serving with the British army garrison in Osnabrück, Clunn decided to contact the regional archaeological authority to ask about promising areas to explore and inform them of his plans. Having thus gained their confidence, he was told of the Von Bar collection and brought into contact with the finder of the latest coin. Clunn now had one fixed location. Another tip from Dr.Schlüter, the regional archaeologist, gave him a line along which to search: an old military route running east-west to the northeast of Osnabrück, the Alte Heerstrasse. That last coin had been found near a crossroads on that road. Clunn established an area to examine with his metal detector and soon found more silver coins. Some time later, and having found many more coins, it appeared that the proportions of the denominations were the same as in the missing Von Bar collection. Moreover, they matched in their division along types of coinage – date, obverse and reverse. Further research showed that this matched the coin finds of the camp at Haltern. Obviously, the units that made up the Augustan era garrison of that fort, had been in the area. Continued research showed a large spread of finds, still consisting of coins, but no indication of a battle yet. That changed with a later find. Clunn described it himself as follows: “Basically, it was the finding of three Roman lead sling shot pieces in three separate fields around the area of the crossroads in late 1988. Having spent an inordinate amount of time during 1987 and 1988 investigating not only the fields in Kalkriese but other Roman sites in northern Germany having a link with the possible movement of Varus during AD 9, it was obviously a revelation to finally find some militaria, in reality weapons in this case, to support the theory that this area was indeed the site of an historic Roman battle. By the time I had finished the majority of my surveys of the Kalkriese area in 1989, Professor Schlüter was now, based on my thoughts and observations of the small hill and narrow pass on the edge of the Kalkrieser Berg, moving his start point of proper archaeological investigations to that key area. The results of those first archaeological excavations in 1989 are now a huge marker in German history, and the deluge of Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 71 71 17-05-2009 17:51:12 THE BATTLEFIELD artifacts that were recovered from those early forays into the hill and out onto the eastern side of the feature quickly confirmed that we were indeed sat on the site of the Varusschlacht. The finding of so many artifacts, so much positive dating, so many coins with what is believed to be Varus’ own personal mint-mark, all lent testimony to proving the site.” Probable candidate Reconstructing Varus’ route from his Summer encampments on the Weser to the Rhine began with the question of where the starting point was exactly. It was always expected to be near Minden on the Weser. In fact, in 2008 local archaeological explorations indeed found a Roman settlement, although it is as of yet too early to confirm that it was definitely Varus’ camp of AD 9. Varus’ camp was expected to be at Minden because of its strategic location. At Minden, the Weser cuts a narrow, deep swathe through the highlands bordering the North German Plain. This so-called ‘Minden Gap’ provides both access to and overview of the areas behind. Its strategic importance was confirmed by the battle of Minden in 1759 and codified in NATO strategy during the Cold War. “Heerstrasse” in Europe often do indeed reflect old military routes. It would be logical to expect such a road along the northern side of an east-west ranging range of hills and mountains. It also fits the narrative. If Varus marched in a south-western direction from Minden to his forts at Haltern and Xanten and was diverted in the direction of the Angrivarii to the north-west, he would have ended up on this route. If Arminius prepared his revolt carefully, and it seems he did, he could hardly have found a better location for an ambush than the narrows at Kalkriese. In AD 9, the extent of the area between the foot of the hill and the swamps to the north was barely 100 meters wide. A Roman army would be severely limited in its options for deployment. The wall found at Kalkriese strengthens this supposition, protecting the warriors and denying the use of the hill to the Romans. The finds at Kalkriese are many and varied. A large number of bones were found, belonging both to mules – the pack animal of choice for the Roman © Karwansaray BV What makes Kalkriese a more convincing candidate than any of the other proposed sites? The first and weakest argument of all, is that the location of a narrows between a swamp and a mountain matches the translation of Saltus Teutoburgiensis just as well as does “Teutoburg Forest.” Also, it is not necessarily the case that the name Tacitus gave to the events of AD 9 has a bearing on the final site. The area to the southeast of Kalkriese, where the battle begun and Varus’ temporary camp should be, was forested. More importantly, routes named The Minden Gap 72 Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 72 17-05-2009 17:51:15 © Karwansaray BV THE BATTLEFIELD Two views of the reconstructed wall at Kalkriese. These earth, turf and timber walls closely hug the outline of the mountain. In front small ditches had been dug. Water running off the mountain would have collected there. Thus, the wall itself was safe from water logging, while the area in front would have become even more drenched. army – and human males of military age. Interestingly, most of those bones were found completely intermixed, indicating they had been slowly covered as time passed, instead of being buried where they had fallen. Some skulls showed clear evidence of a violent death. Others had been carefully stacked in burial pits, ostensibly proving Tacitus’ story that Germanicus’ troops had buried the dead where they found them, though the legionaries had obviously not been too diligent in locating each and every skeleton. Further examination of those bones showed that they had lain above ground for several years before interment. Under and among these skeletons, archaeologists discovered the remains of plants and flowers. Not very spectacular; until it was found that they’d been in bloom when they were crushed by caligae. Plant research showed that these particular plants bloom in September, the right time of year for the Clades Variana. There were the mules, as mentioned in Adrian Murdoch’s article, with muffled bells. Heavy bronze keys have been found without a single trace of the strongboxes they were supposed to fit. Were those perhaps left behind in the camp, buried in the hope of being able to dig them back up later? Then finally, there is the trail of the finds themselves. Laid out on a map, it is almost arrow shaped, coming from the southeast, leading to Kalkriese. There the concentration is highest – but of course the exploration has been most intense there as well – and it then splits into two prongs leading southwest and northwest that peter out very soon. In other words, it seems as if the final assault was made on the remaining Roman troops at Kalkriese. A few broke out and escaped west in two groups. The conclusion is obviously that Kalkriese is definitely the site of an ancient battlefield and is, for now, the best candidate for the site of the ‘end of the line’ for Varus’ legions. It should be noted, however, that there have always been detractors of Kalkriese’s status. Some say that Kalkriese is simply too small to be a battlefield for Varus’ entire army. That argument can be countered by the fact that it was simply the end for those that remained, very likely fewer than half of the original 20,000 or so men. A potentially larger problem looms around the coinage that was so essential for the discovery of this site in the first place. Many of the coins found in Germania Inferior and Kalkriese have been countermarked (i.e.: stamped) “VAR”, which has been taken to indicate Varus. The validity of this hypothesis was corroborated by the fact that no coins had ever been attested with this countermark that date after AD 9. There are now some reports of (single) coins of the emperor Tiberius with this countermark. That would mean a different identification is required, someone other than Publius Quinctilius Varus. And that, in turn, might have consequences for the dating of the Kalkriese site, possibly to a later date than AD 9.n Jasper Oorthuys Further reading Tony Clunn published a diary of his quest, interspersed with a dramatized account of the campaign of AD 9 in The quest for the lost Roman legions. An updated edition was released by Savas Beatie in 2009. Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 73 73 17-05-2009 17:51:19 The battlefield Valkhof Museum, Nijmegen In Varus’ footsteps Tips for visiting the area Do not travel to Germany if you want to see sites associated to Varus’ campaigns AND expect to see traces of fortifications. Most Roman sites in this area have seen continual habitation since The Nijmegen Hunerberg and Kops Plateau are among the most thoroughly examined archaeological sites in Europe. Many of the items on display here derive from the late 1st century AD base of Legio X Gemina, and the Batavian recruiting fortress from the middle of that century. However, you’ll also find an excellent collection of Roman helmets here some of which definitely do date to the German campaigns. www.museumhetvalkhof.nl ancient times. Moreover military construction from this era was almost always in wood. Excavations are usually built over, as they are usually in, or close to, a modern city center. A few exceptions exist. Anreppen and Waldgirmes are currently being excavated; on both sites, the archaeologists have erected explanatory signs. If you are in Nijmegen, do go to the Kops Plateau area. It is now a park and if you peek through the trees on the edge of the natural hill, its strategic location becomes immediately and abundantly clear. Similarly, if you go to Kalkriese, do not just visit the museum, but walk through the park. Though somewhat evened out and the swamp has been The mask now used by the Kalkriese museum in its logo. It was originally covered in silver foil, which was removed by Germanic warriors. The mask was then discarded near the wall. Often thought to have been worn by a standard bearer (as seen on some tombstones), it may simply have belonged to a Roman cavalryman. © VARUSSCHLACHT im Osnabrücker Land GmbH. Foto Christian Grovermann 74 drained, it is an evocative place and the geographical funnel is still visible. Museums There simply is no central spot to see all relevant finds relating to the Varian Disaster. Anyone who wants to visit the area and see some of them will have to make a selection. With an eye on military history, we recommend the following in no particular order. n Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, Germany The provincial capital of Germania Inferior was in nearby Cologne and its Römisch-Germanisches museum is certainly worth a visit although its focus is more civilian-administrative. The Rheinisches Landesmuseum in Bonn has a wonderful collection of Roman and Germanic artifacts from all over this Bundesland, a large collection of tombstones and militaria among them. Under normal circumstances, it is the home of the Caelius cenotaph. www.rlmb.lvr.de Römermuseum, Xanten, Germany Landesmuseum, Mainz, Germany Museum und Park Kalkriese, Kalkriese, Germany Westfälisches Römermuseum, Haltern, Germany This recently renovated museum has an excellent collection of Roman militaria on show and, coupled with the archaeological park next door, is definitely worth a visit. Note however that some of the most famous finds – for instance the so-called Lauersfort set of phalerae or the cenotaph of Marcus Caelius – are elsewhere. The famous memorial, however, is in Xanten in 2009 for a special exhibition. www.apx.lvr.de/roemermuseum At the time of writing, this museum was in the final stage of completing a new extension. Just outside Osnabrück, this museum shows the famous finds from the battlefield. Here you’ll find the famous mask, mules and skeletal remains from the battlefield, as well as the partially reconstructed Germanic wall. www.kalkriese-varusschlacht.de Just outside of Germania Inferior, the Landesmuseum is currently under renovation, but once reopened in 2010, will be a must. It has one of the most impressive collections of Roman military tombstones in Europe, mostly dating to the 1st century AD. It also contains a host of artifacts related to the long military occupation of this site, which was the main base for the Roman route along the Main river. www.landesmuseum-mainz.de Though not as large as some of the other museums in this list, this museum has a fine collection of artifacts that all date to the period of the Germanic campaigns. Haltern, after all, was abandoned at the latest when Germanicus was through with revenge. You will also see some of the finds from the camp at Oberaden on display here. www.lwl-roemermuseum-haltern.de Ancient Warfare AW special mei09.indd 74 17-05-2009 17:51:20 AW special mei09.indd 75 17-05-2009 17:51:22 AW special mei09.indd 76 17-05-2009 17:51:24