Attractiveness Privilege: Unearned Advantages | Master's Thesis

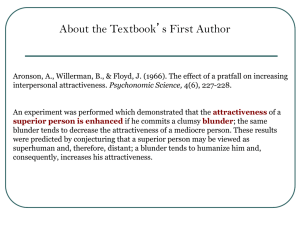

advertisement