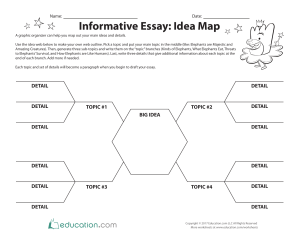

SRI LANKAN ELEPHANTS YALA NATIONAL PARK Group : Group A Name : E C FERDINANDS Index No : CMB/CF/CF/057/12 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION Introduction 2 Origins 3 Species 4-5 II.CHARACTERISTICS Social organizations and Behavior 6 Female and male society 6 Birth and calf development 7 Qestrus and musth 7 Elephant communication and diet 8 III. INTERACTION Sri Lankan elephants 9 Wild elephants 10 Elephants on cultural aspects 11 Economy and tourism 11 IV. CONSERVATION Human-elephant conflict 12 Captive elephants 13 Elephant Transit Home 13 Management of captive elephants 14 Pinnawela Elephant Orphanage 14 INTRODUCTION Elephants is the largest land animal inhabiting in the world as mammals. The adults of the species are herbivorous. They are extremely intelligent social animal by nature. Elephants have captured man’s imagination and respect for thousands of years. In some ways we can draw close parallels between humans and elephants. Like humans, elephants have the capacity to modify their habitats dramatically and their need for space often brings them into direct conflict with expanding human populations. Doyou know there are two species of Elephants in the world? 1. African Elephants - Loxodonta Africanus 2. Asian Elephnat - Elephas Maximus The Asian elephant and its close cousin, the African elephant (Loxodonta African), are the only species surviving in the order Probocidea. Both genera originated in sub-Saharan Africa in the early Pleistocene; Loxondonta remained in Africa, but Elephas moved into Asia during the late Pleistocene. This chapter serves to give a general introduction to the Asian elephant. In describing the lifestyle of a species, it is often convenient to lump all members of the species together and say, for example, “elephants live in families” “elephants prefer to aggregate”, “elephants are seasonal breeders”, or elephants are browsers”. But the study of Asian elephants reveals their social complexity and flexibility, and their ecological adaptability. Page 2 THE ORIGINS OF THE ELEPHANT Today’s elephants are part of the order Proboscidea which consists of modern elephants and their extinct relatives such as mastodons, mammoths, and gomphotheres. Miocene about 22 million years ago and is thought of as part of the second radiation of Proboscidea. Proboscideans may have first evolved in Africa, but both the fossil record and modern elephant distributions show us that they didn’t remain confined to Africa forever. Upon the closing of the Tethys Sea, the landmasses of Africa and Eurasia became reconnected. This allowed members of the order to disperse from Africa into Asia, Europe, and eventually North America and South America as well. The migration of proboscideans from Africa into Eurasia first began in the early Mammutidae (mastodons) originated in Africa in the early Miocene, but by the late early Miocene they had spread into Europe. In the middle Miocene they had migrated across Asia, and eventually entered into North America by crossing the Bering Land Bridge. Mastodons are found in the fossil record of North America as recent as only 12,000 years ago. Mammutidae Page 3 Gomphotheriidae Elephantidae The gomphotheres were a group of proboscideans that often featured two upper tusks and two spatulate lower tusks. By the early Miocene the gomphotheres had already spread through much of Africa, Europe, and Asia, soon followed by migrations into North America via the Bering land bridge in the middle Miocene. In the Pleistocene, the gomphotheres even reached South America. Elephantidae consists of elephants (including those still alive today),mammoths, and other extinct relatives. They originated in Africa about 6-8 million years ago during the Miocene and members of the family dispersed into Asia and Europe multiple times through the mid and late Pliocene. When mammoths went extinct ~4,000 years ago, that left the modern Asian and African elephants (Elephas maximus, Loxodonta cyclotis, and Loxodonta africana, respectively) as the last surviving members of not only Elephantidae, but Proboscidea as a whole. Stegodontidae The stegodontids are a family of proboscideans that are thought to have evolved from gomphotheres somewhere in Asia. They looked a lot like modern elephants on the outside, but had very different teeth. The stegodontids lived from the early to middle Miocene into the late Pleistocene and were spread across Asia and Africa. ELEPHANTS THAT CAN BE SEEN TODAY Page 4 Page 4 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN AN AFRICAN AND SRI LANKAN ELEPHANT Approximately 7.5 million years ago the The ancestors of the African and Asian elephants on this planet were separated and thus began to evolve separately in the African and Asian continents. It is due to the diversity of these two habitats that the African and Asian elephants have evolved with anatomies that have many differences. Ribs up to twenty one pairs Number of toe nails fore feet (4) hind feet(3) De-pigmentation absent Sri Lankan Elephants African Elephants Height 3.5m Weight 4000-7500kg Back Concave Forehead no humps Tip of trunk two finger like projections Ears large with no folds Tusks borne by both male and females Grinding surface of teeth Contains diamond shaped plates Height 3m Weight 3000-6000kg Back flat or convex Forehead has two humps Tip of trunk one finger like projection Ears relatively small with folds Tusks borne by only males Grinding surface of teeth contains oval shaped plates Ribs up to twenty pairs Number of toe nails fore feet (5) hind feet (4) De-pigmentation present Page 5 CHARACTERISTICS SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND BEHAVIOUR Asian elephants live in a fluid and dynamic social system in which males and females live in separate, but overlapping spheres. Related females and their immature offspring live in tightly knit matriarchal family units, while males live a more solitary independent existence with few social bonds. Female society Female elephant society consists of complex multitiered relationships extending from the mother offspring bond to family units, bond groups and clans. The basic social unit is the family which is composed of one to several related females and their immature offspring, and may range in size from two to 30 individuals. Elephants appear to benefit from being part of a large family. Related females will form defensive units against perceived danger and will form coalitions against other nonrelated females or males. Members of families or bond groups display a special greeting ceremony, show a high frequency of association over time, act in a coordinated manner, exhibit affiliative behavior toward one another and are usually related Male society Male elephants leave their natal families at about 14 years of age. Newly independent young males may follow several different courses to social maturity. Some young males leave their families only to join up with another family for a couple of years. Others go off to bull areas and join up with bull groups, while still others stay in female areas moving from family to family. Adult male elephants exhibit a period of heightened sexual and aggressive activity known musth. During sexually inactive and non-musth periods males spend time alone or in small groups of other males in particular bull areas, where their interactions are relaxed and amicable. During active musth periods males leave their bull areas move in search of females, which time they are likely to be found alone or in association with groups of females. Among musth males, dominance is determined by a combination of body size and condition. Two closely matched males will often fight, sometimes to the death of one of them Page 6 Qestrus and musth The oestrous period lasts for four to six days. It has been postulated that ovulation and conception occur during mid-oestrus when females are guarded and mated by a high-ranking musth male. Oestrous females attract males by exhibiting conspicuous behaviour, calling loudly and frequently, and producing urine with particular olfactory components. If a female does not conceive she will come into oestrus again three months later if she is still in good condition. During musth, males secrete a viscous liquid from swollen temporal glands just behind the eyes; they leave a trail of strong smelling urine, and call repeatedly in very low frequencies. A male’s testosterone levels rise to over five times his nonmusth levels, and musth males behave extremely aggressively toward other males, particularly those also in musth Individual males attempt to locate, guard and mate with as many oestrous females as possible during their musth periods. Birth and calf development Elephants are born after a gestation period of 22 months with the average birth weight of males being 120kg, 20-30kg more than that for females. The energetic requirements of calves are met exclusively by milk consumption for the first three months of life. After this age calves begin to feed independently with the time spent feeding increasing rapidly between four and 24 months when it levels off to about 55% of daily time. The majority of calves suckle until the birth of the next calf, but some calves are weaned before the birth of the next calf, while others continue to suckle after their sibling’s birth. Page 7 ELEPHANT COMMUNICATION Elephants communicate vocally using a wide variety of sounds, from the higher frequency screams, trumpets, snorts and bellows to the lower frequency rumbles which contain components below the level of human hearing, some as low as 14Hz. The ability of elephants to produce these very low frequency sounds, at sound pressure levels of up to 102dB at 5m, means that they are, theoretically, able to communicate with one another over distances of 510km, even in thick forest. The fundamental differences in male and female elephant society are no better revealed than by the striking sex difference in the number and variety of vocalizations each uses . Females use some 22 different vocalizations while males use only seven; only three of these calls are made by both sexes. DIET An elephant’s diet may include grass, herbs, bark, fruit and tree foliage. In savanna habitats grass may make up 70% of the elephants’ diet in the wet season, with larger proportions of browse contributing to their diet as the dry season progresses. In tropical forest, an elephant’s diet may include as many as 230 species with leaves, twigs, bark and fruit constituting over 90% of all items eaten. Elephants need a combination of grassland in which they graze and leaves from shrubs and trees to browse. Bacteria in their stomachs break down the cellulose in the plant matter. Baby elephants are born without this bacteria. Baby elephants ingest the dung of adults. This must be an instinctive response that enables them to obtain the microflora they need in their stomachs for digestion. Asian elephants consume round 150kg of vegetable matter in a day. Page 8 INTERACTION SRI LANKAN ELEPHANTS Sri Lanka holds an important position with regard to Asian elephant conservation. Well over 10% of the global Asian elephant population in less than 2% of elephant range makes Sri Lanka the range country with the highest density of elephants. It also has one of the highest human densities among range countries. Therefore successes and failures in Sri Lanka can provide critical insights into mitigating human-elephant conflict and conserving elephants. In addition Sri Lankan elephants are recognized as a distinct subspecies. Although genetic support for a subspecific distinction is low, Sri Lanka has the highest genetic diversity of Asian elephants. wooden carvings, many fine examples of which can be found in the ancient cities of Sri Lanka such as Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura and Kandy as well as contemporary places of worship. Sri Lanka have a very close association with elephants that extends back millennia. Characterization of elephants such as the division into ‘castes’, and the management of captive elephants has been the subject of many ancient treatises. Elephant motifs have been widely used in Sri Lankan art since ancient times. They are a prominent feature of stone and Page 9 WILD ELEPHANTS Sri Lanka is an island of 65,000 km2. The southwest quarter of the island known as the ‘wet zone’, receives rain throughout the year. The rest of Sri Lanka has seasonal rainfall and is known as the ‘dry zone’. Central mountains rise up to about 2500 m. The natural vegetation is dry evergreen forest in the dry zone, rain forest in the wet zone and montane forest in the mountains. Prior to human presence, most of the country was covered in mature forest and elephants probably inhabited the entire island. Elephant densities were likely in the range of 0.1-0.2 elephants /km2 with a total of around 6,00012,000 elephants. The advent of people and especially the rise of a ‘hydraulic civilization’ based on irrigated agriculture in the dry zone around 2500 years ago caused significant environmental changes and likely impacted elephant numbers and distribution profoundly. However shifting cultivation and the construction of innumerable fresh water reservoirs for irrigated agriculture would have enriched the habitat for elephants, allowing higher densities in fringe areas. Large numbers of elephants were captured and domesticated for local use and export. With the rise and fall of kingdoms and shifting of centers of civilization, elephant populations would have alternately become locally extirpated and abundant. Current elephant distribution in Sri Lanka. Areas of distribution are demarcated by a heavy red line. Elephants are absent in polygons demarcated by a thin red line. Green polygons denote DWC protected areas. Numbers and letters indicate areas referred to in the text: N=North, NW=Northwest, NC=North-central, S=South, E=East, 1=Udawalawe NP, 2=Lunugamvehera NP, 3=Yala NP, 4=Yala NP Block I, 5=Bundala NP, 6=Mattala, 7=Sinharaja, 8=Adam’s Peak, 9=Minneriya-Kaudulla NPs and Hurulu Reserve, 10=Kala Wewa, 11=Wilpattu NP Current elephant distribution Page 10 ELEPHANTS ON CULTURAL ASPECTS Elephants hold a central position in the country’s two main religions Buddhism and Hinduism as well as in Sri Lankan culture. The elephant is considered a symbol of physical and mental strength, intelligence, responsibility, good luck and prosperity. Elephants are kept in a number of temples and feature prominently in annual pageants named ‘peraheras’. The most famous is held in August in the city of Kandy, which features up to a hundred richly caparisoned elephants festooned with lights, together with thousands of drummers, musicians, dancers, torch bearers etc. The highpoint of the Kandy perahera is the ceremonial exposition of the tooth relict of the Lord Buddha carried on the back of a majestic tusker of the highest ‘caste’. ECONOMY AND TOURISM Sri Lanka has been identified as one of the most popular destinations in the world by many travel experts. Despite the many attractions, there is one thing that tourist visiting Sri Lanka never miss is the elephants. Many tourist visit Sri Lanka engaging in activities such as elephant safaris, elephant back rides, participating cultural events which use elephants. With this background it can be identified that elephants play a vital role in Sri Lanka's tourism industry and economy. They attract tourist who visit national parks to observe elephants in the wild. According to the report by the Department of wildlife, 2587.97 million rupees was contributed to Sri Lankan economy. Page 11 CONSERVATION HUMAN-ELEPHANT CONFLICT Over the past century the human population has increased rapidly resulting in extensive areas of land being acquired for human habitation, farming and infrastructure development. This expansion has resulted in a loss of habitat for elephants, disruption of their movement patterns and their access to food and water. The result has been a conflict in land use between human and elephants. Faced with a diminishing habitat, elephants stray into areas of human habitation causing damage to property, crops and human life as well. death to elephants. Over the past 15 years alone this conflict has claimed nearly 2000 elephants and 836 human lives. The highest number of conflicts occur in the Northwestern, Central, Eastern and Southern Provinces of Sri Lanka. Statistics show that in this conflict male mortality is higher in both elephants and humans. This is due to the fact that more than 80% of the intrusions are attributed to bull elephants, while it is men that are primarily engaged in protecting farmland and property. In trying to protect their life and property humans cause injury and Page 12 CAPTIVE ELEPHANTS ELEPHANT TRANSIT HOME Captive elephants have been a central feature of Sri Lankan civilization since antiquity. Ancient kings maintained stables of elephants that numbered in the thousands, including hundreds of war elephants. In the colonial period the Portuguese and Dutch rulers had a monopoly over the ownership of all domesticated elephants. Later the Dutch allowed the local Chieftains, who captured wild elephants for their colonial masters as tribute, to keep one or two. This is how the tradition of elephant keeping by private owners started in Sri Lanka. Currently elephants are kept by temples, private owners, the National Zoological Gardens at Dehiwala, the Pinnawela Elephant Orphanage and the Elephant Transit Home at Udawalawe. Some temples and private owners have been given young elephants from Pinnawela. Captive elephants in Sri Lanka do not have any opportunities to interact with wild elephants. There have been very few births in captive elephants outside of the Pinnawela Elephant Orphanage. Currently there are around 112 captive elephants in Sri Lanka with temples and private owners. Captive elephant numbers have decreased steadily over the years. The ETH was set up to take care of orphaned elephants until they are fit enough to be released back to the wild. Orphaned elephants brought to the ETH are treated and taken care of for about three years. The mortality rate of arrivals is around 40%. They remain as a group during the day and are kept in a stall for the night. They are bottle fed every 4 hours throughout the 24 hours. An entrance fee is charged from visitors to the ETH and they can observe elephants being bottle fed. An information centre set up in collaboration with the Dilmah Trust, provides information on elephants to visitors. Page 13 MANAGEMENT OF CAPTIVE ELEPHANTS PINNAWELA ELEPHANT ORPHANAGE Other elephants held by temples and private owners are mostly single animals. They are mainly used in pereheras. A few elephants still work in handling logs etc. and some are engaged in giving rides to tourists especially in Habrana. Elephant owners lobby for legalizing wild captures and releasing elephants from Pinnawala or the ETH on the argument that the captive population is declining and that it is essential to maintain the cultural and religious traditions associated with elephants. Veterinary care for captive elephants is provided by the University of Peradeniya Veterinary Faculty, DWC and private veterinarians. Some owners and mahouts prefer traditional medicine to western. HEC results in baby elephants becoming orphaned due to the mother’s death or abandonment. The Pinnawela Elephant Orphanage was set up in 1975 to take care of such orphans. Started with five orphaned baby elephants, the addition of orphans continued till 1995 when the Elephant Transit Home was created by the DWC. Since then, orphaned babies have been taken to the ETH and addition to the Pinnawela herd has been mostly through births occurring there. So far Pinnawela has recorded 69 births – 38 males and 31 females. Currently there are 88 elephants (37 males and 51 females) in Pinnawela representing 3 generations. There are 48 mahouts (handlers) to look after them. Page 14