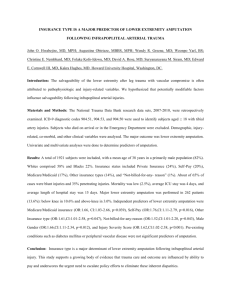

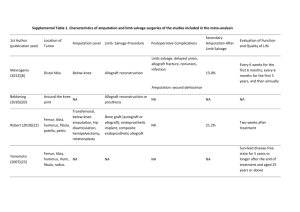

ARTICLE IN PRESS The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 000 (2023) 1−5 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery journal homepage: www.jfas.org Original Research Amputation Acceptance: A Survey of Factors Influencing the Decision to Undergo Lower Extremity Amputation Gina Cach, BA1, Ashley E. Rogers, MD2, Daisy L. Spoer, MS1, Adaah A. Sayyed, BS1, Romina Deldar, MD2, Christopher E. Attinger, MD2, Karen K. Evans, MD2 1 2 Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC A R T I C L E I N F O Level of Clinical Evidence: 3 Keywords: decision-making process multidisciplinary team patient education postoperative satisfaction shared decision making A B S T R A C T Accepting to undergo amputation is an arduous process often fraught with confusion, fear, and uncertainty. To assess how to best facilitate discussions with at-risk patients, we surveyed lower extremity amputees about their experiences surrounding this decision-making process. Patients who underwent lower extremity amputation at our institution from October 2020 to October 2021 were asked to complete a 5-item telephone survey assessing their decision to undergo amputation and postoperative satisfaction. Retrospective chart review of respondent demographics, comorbidities, operative details, and complications was conducted. Of 89 lower extremity amputees identified, 41 (46.07%) responded to the survey, with the majority undergoing below-knee amputations (n = 34, 82.93%). At a mean follow-up of 5.90 § 3.45 months, 20 patients (48.78%) were ambulatory. Surveys were completed at a mean of 7.74 § 4.03 months since amputation. Factors that helped patients decide to undergo amputation included discussions with doctors (n = 32, 78.05%) and concern for worsening health (n = 19, 46.34%). Deteriorating ability to walk (n = 18, 45.00%) was the most common concern prior to surgery. Recommendations by survey respondents to ease the decision-making process included speaking with amputees (n = 9. 22.50%), more discussions with doctors (n = 8, 20.00%), and access to mental health and social services (n = 2, 5.00%); however, many had no recommendations (n = 19, 47.50%), and most were pleased with their decision to undergo amputation (n = 38, 92.68%). Despite most patients primarily citing satisfaction with their decision to undergo lower extremity amputation, it is critical to consider factors that affect patient decisions and recommendations to improve this decision-making process. © 2023 by the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. All rights reserved. Approximately 100,000 traumatic and atraumatic lower extremity (LE) amputations are performed in the United States each year, with more than half occurring in populations with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and peripheral vascular disease (PVD) (1,2). National trends suggest that the overall rate of LE amputation in the United States has decreased over recent years; however, DM and PVD continue to pose a significant disease burden given increasing rates of these comorbidities (1). Despite the rising prevalence of these chronic diseases, there has also been an increase in integrative team-based care as well as utility of procedures such as surgical revascularization, which can decrease the Financial Disclosure: None reported. Conflict of Interest: None reported. MedStar Georgetown University Hospital IRB approved on 11/11/2021 via expedited review: STUDY00004369. Address correspondence to: Karen K. Evans, MD, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, 3800 Reservoir Road NW, First Floor PHC Building, Washington, DC 20007. E-mail address: karen.k.evans@medstar.net (K.K. Evans). risk of amputation (3). Unfortunately, amputation may need to be considered when other treatment options are lengthy, costly, or offer a poor prognosis (4). Our institution’s wound care center includes plastic, podiatric, and vascular surgeons, hospitalists, infectious disease specialists, endocrinologists, nephrologists, rheumatologists, nurses, prosthetists, and physical therapists. We treat approximately 1200 new patients and over 20,000 total patients yearly. As a result of this high at-risk patient volume, our team is routinely tasked with initiating discussions regarding LE amputation with our patients. LE amputation is complicated not only by the aforementioned medical comorbidities, but also by numerous psychosocial factors. Patients are faced with the significant morbidity and mortality of these procedures, along with the task of redefining their identity and functionality postoperatively. Over the last year, 89 patients received LE amputations at our institution. To assess the most effective methods to facilitate amputation discussions and best support at-risk patients, we surveyed recent LE amputees regarding their experiences surrounding this decision-making process. 1067-2516/$ - see front matter © 2023 by the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2022.12.012 ARTICLE IN PRESS G. Cach et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 00 (2023) 1−5 2 Patients and Methods Following institutional review board approval, patients who underwent LE amputation at our institution from October 2020 to October 2021 were asked to complete a 5item telephone survey designed to assess their decision to undergo amputation and their overall satisfaction following the procedure. The full survey text is available (Supplemental Digital Content 1). The survey period began on December 1, 2021 and ended on January 27, 2022. Following the survey collection period, a retrospective chart review was conducted to collect patient demographics, comorbidities, operative details, and complications for those who completed the survey. Patient demographics included age, sex, smoking history, and body mass index (BMI). Comorbidity data was collected to assess comorbidity status using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scoring system. Operative details included the indication for amputation, level of amputation, and whether peripheral nerve procedures such as targeted muscle reinnervation (TMR) or regenerative peripheral nerve interface (RPNI) were performed at time of amputation. Recorded complications were postoperative infection, dehiscence, hematoma, seroma, and return to the operating room (OR). Outcomes such as ambulatory status and the need for an assistive device were also recorded. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize study subjects. Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test of normality. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA v.17 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with statistical significance set at values of p ≤ .05. Results Patient Demographics A total of 89 LE amputees were identified, of which 41 (46.07%) responded to the survey. Thirty respondents were male (73.17%) and 11 were female (26.83%). Mean age and BMI were 59.71 § 15.52 years and 31.70 § 7.02 kg/m2, respectively. Mean CCI score was 5.07 § 2.64, with the most frequent comorbidities being DM (n = 27, 65.85%) and PVD (n = 25, 60.98%). Other comorbidities included chronic kidney disease (CKD; n = 14, 34.15%), end-stage renal disease (ESRD; n = 8, 19.51%), congestive heart failure (CHF; n = 7, 17.07%), history of venous thromboembolism (VTE; n = 5, 12.20%), and history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (n = 5, 12.20%). Patients most commonly had no prior smoking history (n = 26, 63.41%). Table 1 details survey respondent demographics. Table 1 Respondent demographics Variable n (%) Total responses Complete responses Partial responses Age (years) Sex Male Female Smoking history None Prior history Current smoker BMI (kg/m2) CCI Comorbidities DM PVD CKD ESRD VTE Stroke or TIA Months from date of surgery to survey date 41/89 (46.07%) 40/41 (97.56%) 1/41 (2.44%) Mean § SD 59.71 § 15.55 30 (73.17%) 11 (26.83%) 26 (63.41%) 8 (19.51%) 7 (17.07%) 31.71 § 7.02 5.07 § 2.64 27 (65.85%) 25 (60.98%) 14 (34.15) 8 (19.51%) 5 (12.20%) 5 (12.20%) 7.74 § 4.03 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; SD, standard deviation; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VTE, venous thromboembolism. There were no significant differences between survey respondents and nonrespondents with regards to age and sex. Reasons for not completing the survey included being unable to contact the patient after 3 attempts (n = 27, 56.25%), contact information being incorrect (n = 8, 16.67%), the patient being deceased (n = 7, 14.58%), or the patient declining to participate (n = 6, 12.50%). Operative Details and Follow-Up At time of surgery, mean albumin and prealbumin levels were 4.11 g/dL and 15.82 mg/dL, respectively. Average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was 6.62%. The most common indications for LE amputation were infection (n = 22, 53.66%) and ischemia (n = 9, 21.95%), and less commonly Charcot foot (n = 4, 9.76%), chronic pain (n = 4, 9.76%), and chronic wounds (n = 2, 4.88%). The majority of patients underwent below-knee amputations (BKA; n = 34, 82.93%) and received TMR (n = 30, 73.17%) or RPNI (n = 7, 17.07%) at time of amputation. There was no significant difference in type of amputation performed between survey respondents and nonrespondents. Postoperatively, 6 patients (14.63%) experienced complications which required return to the OR. Complications most commonly included dehiscence (n = 5, 12.20%) or infection (n = 3, 7.32%). The mean follow-up was 5.90 § 3.45 months. Based on most recent followup clinic visit data, 20 patients (48.78%) were ambulatory, either independently (n = 11, 26.83%) or with an assistive device (n = 9, 21.95%) such as a walker, crutch, or walking stick. Among ambulatory patients, the mean time to ambulation was 4.07 § 2.65 months postoperatively. Table 2 outlines operative details and postoperative outcomes. Survey Responses There were 41 survey respondents (41/89 amputees, 46.07% response rate), of which 40 (97.56%) completed the entire survey. Table 2 Respondent operative details and follow-up Variable Indication for amputation Infection Ischemia Charcot Chronic pain Chronic wounds Type of amputation BKA AKA Peripheral nerve surgery Total TMR RPNI Preoperative Labs Albumin (g/dL) Prealbumin (mg/dL) HbA1c (%) Complications Infection Dehiscence Return to operating room Follow-up (months) Ambulatory status Yes, independent Yes, with assistive device No Time to ambulation (months) n (%) Mean § SD 22 (53.66%) 9 (21.95%) 4 (9.76%) 4 (9.76%) 2 (4.88%) 34 (82.93%) 7 (17.07%) 37 (90.24%) 30 (73.17%) 7 (17.07%) 4.11 § 3.07 15.82 § 6.77 6.62 § 1.45 3 (7.32%) 5 (12.20%) 6 (14.63%) 5.90 § 3.45 11 (26.83%) 9 (21.95%) 20 (48.78%) 4.07 § 2.65 Abbreviations: AKA, above-knee amputation; BKA, below-knee amputation; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1C; RPNI, regenerative peripheral nerve interface; TMR, targeted muscle reinnervation. ARTICLE IN PRESS G. Cach et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 00 (2023) 1−5 3 Table 3 Survey responses Question Response n (%) What were reasons that HELPED you decide to undergo the amputation? (n = 41) Discussions I had with my doctors Educational materials, pamphlets, brochures Speaking with amputees or reading amputee testimonials I thought it would improve my pain I thought it would improve my ability to walk I listened to my friends and family I was worried my health would worsen without the amputation Speaking with prosthetists I thought it would improve my chronic wounds and infections Discussions I had with my doctors Educational material, pamphlets, brochures Speaking with amputees or reading amputee testimonials I thought it would worsen my pain I thought it would worsen my ability to walk I was worried I would lose my job I was worried my health would worsen with the amputation I was worried about how it would change my body image I was worried I would get depressed Uncertainty of the future Remaining independent Undergoing surgery and postoperative recovery Making the decision quickly due to life-threatening circumstances No worries about amputation More educational materials and information More discussions with my doctors Speaking with amputees Access to videos of amputees walking Access to resources for mental health and social services No additional recommendations Yes No 32 (78.05%) 9 (21.95%) 7 (17.07%) 9 (21.95%) 10 (24.39%) 14 (34.15%) 19 (46.34%) 2 (4.88%) 9 (21.95%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (2.50%) 6 (15.00%) 18 (45.00%) 3 (7.50%) 7 (17.50%) 4 (10.00%) 5 (12.50%) 4 (10.00%) 4 (10.00%) 7 (17.50%) 7 (17.50%) 11 (27.50%) 6 (15.00%) 8 (20.00%) 9 (22.50%) 2 (5.00%) 2 (5.00%) 19 (47.50%) 38 (92.68%) 3 (7.32%) What were reasons you were WORRIED about getting the amputation? (n = 40) How could your surgery team have helped make this an easier decision for you to make? (n = 40) Are you pleased with your decision to undergo amputation? (n = 41) Surveys were completed at a mean of 7.74 § 4.03 months since amputation. The most cited reasons that helped patients decide to undergo LE amputation included discussions with their doctors (n = 32, 78.05%), concern for worsening health if they did not undergo amputation (n = 19, 46.34%), and advice from friends and family (n = 14, 34.15%). Other helpful factors included printed educational materials (n = 9, 21.95%) and hope that undergoing amputation would improve chronic wounds and infections (n = 9, 21.95%), pain (n = 9, 21.95%), and the ability to walk (n = 10, 24.39%; Table 3). Regarding concerns about undergoing amputation, a deteriorating ability to walk (n = 18, 45.00%) was cited as the most common concern among patients. Other concerns included worsening health (n = 7, 17.50%), undergoing surgery itself and postoperative recovery (n = 7, 17.50%), and having to make the decision quickly due to life-threatening circumstances (n = 7, 17.50%). Five patients (12.50%) also reported concerns about depression postoperatively. However, 11 patients (27.50%) reported no concerns with undergoing amputation. Samples of the free responses provided by patients are noted in Table 4. Regarding the usefulness of communication with doctors and staff, one patient stated: “it was helpful that my doctors were upfront, straight-forward, and honest about the possibility of amputation, discussing advantages and disadvantages.” The importance of communication with family and friends was also highlighted through patient responses such as: “it was helpful to bring family to visits prior to the amputation,” and “I had many discussions with family prior to surgery.” As for worries prior to undergoing amputation, some patients voiced concerns regarding their health with comments such as: “my doctor explained that the problem would lead to deterioration of the leg. . . [my decision] was more driven by my health.” Many patients also highlighted both hopes and worries regarding mobility postoperatively: “I felt like I would be able to walk better after surgery,” or “my biggest worry was wearing shoes and walking again.” The uncertainty about life after surgery impacted many patients, with one patient describing “I was worried I would be a burden and not be able to do my daily activities alone.” When asked about ways the surgical team could have eased the decision-making process, many had no additional recommendations Table 4 Themes among survey responses Communication with doctors and staff Communication with family and friends Worries about health Hopes and worries about mobility Uncertainty about life after surgery "It was helpful to speak with various members of the care team across specialties." "It was helpful that my doctors were upfront, straight-forward, and honest about the possibility of amputation, discussing advantages and disadvantages." "I trusted my doctors and care team." "It was helpful to bring family to visits prior to the amputation." "I had many discussions with family prior to surgery." "I was septic and felt I had no other choice." "The infection in my leg was worsening, and my health was deteriorating." "My doctor explained that the problem would lead to deterioration of the leg, that was the most important. It was more driven by my health." "I felt like I would be able to walk better after surgery." "I wanted to get back to walking." "I live on a farm, and I was fearful I would not be able to get back to that." "My biggest worry was wearing shoes and walking again." "I was worried I would be a burden and not be able to do my daily activities alone." "I was worried about the uncertainty of the future." "I had fears of the unknown." ARTICLE IN PRESS 4 G. Cach et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 00 (2023) 1−5 (n = 19, 47.50%), and most patients were pleased with their decision to undergo amputation (n = 38, 92.68%). In comparison, 22.50% (n = 9) stated that speaking with other amputees would have aided in their decision, and 20.00% (n = 8) reported that more discussions with doctors would be helpful. Two (5.00%) patients reported that access to resources for mental health and social services could have made their decision easier. Discussion We present the first study assessing personal and clinical factors impacting a patient’s decision to undergo amputation as well as patient recommendations to improve this process. Patients highlighted the importance of discussions with their physicians along with hopes and fears regarding the impact amputation would have on their ability to walk. Most patients had no recommendations for changes the clinical team could make to improve the process, with most of those surveyed stating that they were pleased with their decision to undergo amputation. The overall satisfaction of our patients with the decision-making process and their amputation emphasizes the importance of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to patient care that we utilize at our wound care center. The MDT approach to the diabetic foot has been widely recognized to improve patient care and to reduce ulcer recurrence, the rate of major limb amputations, and healthcare costs (5,6). These benefits of a MDT are well known and were further substantiated by this study, as most patients (78%) cited discussions with doctors as the most prevalent factor in aiding their decision to undergo LE amputation. Furthermore, 5% of our patients reported that speaking with prosthetists aided their decision. Given the overall satisfaction of our patients with their experience, we highlight the protocol used by our wound care center when approaching patients at-risk for amputation in the Fig. Despite the vast nature of the MDT approach, the inclusion of psychiatry is a potentially overlooked facet of this team. A psychiatrist can not only assist during the amputation decision-making period, but also provide close follow-up in the postoperative period as patients become accustomed to their new life after amputation. Akin to the loss of a loved one, amputees have been said to face the 5 stages of grief (7). Physical disability, such as the loss of a limb, can result in despair, depression, anxiety, nervousness, loss of self-esteem, isolation, stigma, and the recognition of weakness (8). This loss may necessitate assistance as patients transition into a new phase of life without their limb, and the importance of psychiatry as part of the MDT during this transition period has been touted (7). As part of this study, 12.5% of our patients cited concerns about depression postoperatively, and 5% reported access to mental health and support services as a component that could have eased their decision to undergo amputation. An 18-month longitudinal study by the World Health Organization found that 14.1% of amputees reported depression (9). McKechnie et al found levels of anxiety and depression to be significantly higher in amputees compared to the general population, with another study by Horgan et al estimating depression and anxiety to be moderately elevated for up to 2 years following amputation (10,11). While psychiatry has yet to be added to our MDT, it is certainly a consideration to further improve care. Social support represents another critical component of wellness following major amputation. A patient’s perceived social support can not only aid in the decision-making process, but also in the recovery period. Support from family and friends was cited by 34.1% of respondents as a factor that helped them make the decision to undergo amputation. As stated above, many amputees experience depression postoperatively, and studies done among amputees have observed that social support is a protective factor against depression and adjusting to life after amputation (12-14). However, we are conscious that not every patient has close social relationships. At our institution, we host a monthly amputee support group and connect patients with former amputee patients. Seven patients (17.1%) felt that this connection helped them to make the decision. However, results of this study suggest inconsistency with awareness and/or availability, as 22.5% of patients felt they could have benefited from such a resource. Our team recognizes the importance of inquiring about support early on, and ideally preoperatively if possible. Previously, we would initiate discussions based on need, but we now see the value in standardizing this process by inquiring about support at each clinic visit and providing information regarding upcoming amputee meetings or support availability. If a patient is at-risk for amputation, it is also integral to initiate discussions regarding the possibility of amputation as early in the patient’s course as possible. Seven respondents (17.5%) reported that making the decision to amputate quickly due to being in a life-threatening situation was a concern. Deciding to undergo LE amputation is difficult and Fig. Protocol for approaching patients at-risk of amputation. This figure outlines our protocol for approaching patients at-risk of amputation. Our study highlights the relative success of our current protocol given that the majority of patients were pleased with the decision-making process. ARTICLE IN PRESS G. Cach et al. / The Journal of Foot & Ankle Surgery 00 (2023) 1−5 fraught with uncertainty, and for these patients, it was compounded by the pressures of deteriorating health. It is evident that conversations regarding amputation should be initiated early so that patients can be prepared and understand treatment options available to them prior to these critical moments. While this is an option for our established patients, unfortunately these discussions cannot always be planned, such as in trauma patients. Our limb salvage and wound care center also receives many tertiary referral patients, who often travel long distances to our practice. As such, these patients do not have the means to establish care and have discussions regarding amputation in advance. Initiating early discussions regarding amputation also allows for adequate and substantial patient education. While 22% of patients found printed educational materials helpful in making the decision to undergo LE amputation, 15% of our patients reported wanting additional educational materials. Furthermore, 20% of our patients may have benefited from further discussions with our care team. The results of this study have encouraged us to streamline our educational process and consider additional means of providing patients with information regarding amputation, such as a folder to consolidate educational materials or an interactive website that can include testimonies from previous patients, videos of prior amputee patients taking part in physical activities, resources for diseases associated with amputation such as DM, care tips when living with a prosthetic, and details for amputee support groups and online forums. Our study has several limitations, including a small sample size along with the retrospective nature of data collection, which is influenced by the quality of data captured in the electronic medical record. Furthermore, there is a possibility of recall bias given that surveys were completed at a mean of 7.7 months postoperatively. Survey responses could also have been biased by the quick decision-making timeline, as several patients’ decisions to undergo LE amputation were influenced by life-threatening circumstances. Despite the difficulty of making the decision to undergo LE amputation, 92.7% of respondents reported satisfaction with their decision. These positive postoperative satisfaction results could be influenced by the functional-based amputation and pain reduction techniques, such as prophylactic TMR or RPNI, that were performed in 90.2% of patients at the time of amputation. Thus, it is difficult to extrapolate postoperative satisfaction results to other centers that may not utilize these prophylactic techniques. Other limitations include variations in who is initiating the conversation about LE amputation with patients who present to our hospital for limb salvage or amputation. At our institution, these discussions may be started by attendings to chief residents to interns. It may be advantageous to have psychiatry be a central and integral member present for initiation of these discussions to facilitate concerns and provide continuity of care. 5 In conclusion, the majority of patients cited satisfaction with their decision to undergo LE amputation, and many did not recommend changes to their surgical decision-making process. However, it is crucial to recognize the various factors that can affect a patient’s decision, as incorporating patient feedback into our multidisciplinary care team allows us to provide the best care for this vulnerable patient population. Future studies will be necessary to assess the utility and helpfulness of new protocols implemented to our clinic’s approach to patients at-risk for amputation (e.g., updated and accessible educational materials, team psychiatrist). Supplementary Materials Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jfas.2022.12.012. References 1. Barnes J, Eid M, Creager M, Goodney P. Epidemiology and risk of amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020;40:1808–1817. 2. Cai M, Xie Y, Bowe B, Gibson AK, Zayed MA, Li T. Temporal trends in incidence rates of lower extremity amputation and associated risk factors among patients using veterans health administration services from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Network Open 2021;4:e2033953. 3. Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990−2010. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1514–1523. 4. Marso SP, Hiatt WR. Peripheral arterial disease in patients with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:921–929. 5. Musuuza J, Sutherland BL, Kurter S, Balasubramanian P, Bartels CM, Brennan MB. A systematic review of multidisciplinary teams to reduce major amputations for patients with diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2020;71:1433–1446.e3. n-Sa nchez J, Jime nez S, et al. Reducing major lower extremity ampu6. Rubio JA, Arago tations after the introduction of a multidisciplinary team for the diabetic foot. Int J Lower Extremity Wounds 2014;13:22–26. 7. Spiess KE, McLemore A, Zinyemba P, Ortiz N, Meyr AJ. Application of the five stages of grief to diabetic limb loss and amputation. J Foot Ankle Surg 2014;53:735–739. 8. Khan JB, Dogar SF, Masroor U. Family relations, quality of life and post-traumatic stress among amputees and prosthetics. Pakistan Armed Forces Med J 2018:125–130. 9. Seidel E, Lange C, Wetz HH, Heuft G. Anxiety and depression after loss of a lower limb. €de 2006;35:1152, 1154-1158. Der Orthopa 10. Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury 2014;45:1859–1866. 11. Horgan O, MacLachlan M. Psychosocial adjustment to lower-limb amputation: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:837–850. n O, Romild U, Stordal E. Association between social support and 12. Grav S, Hellze depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:111–120. 13. Anderson DR, Roubinov DS, Turner AP, Williams RM, Norvell DC, Czerniecki JM. Perceived social support moderates the relationship between activities of daily living and depression after lower limb loss. Rehabil Psychol 2017;62:214–220. 14. Unwin J, Kacperek L, Clarke C. A prospective study of positive adjustment to lower limb amputation. Clin Rehabil 2009;23:1044–1050.