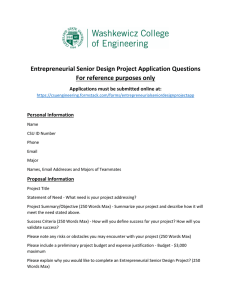

Received: 14 November 2017 Revised: 15 April 2019 Accepted: 19 April 2019 DOI: 10.1002/job.2374 THE JOB ANNUAL REVIEW Entrepreneurial motivation: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research Charles Y. Murnieks1 | Anthony C. Klotz1 | Dean A. Shepherd2 1 College of Business Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon Summary 2 Mendoza College of BusinessNotre Dame University, Notre Dame, Indiana Given the substantial impact that new ventures have on the global economy, under- Correspondence Charles Y. Murnieks, Oregon State University, College of Business, 443 Austin Hall, Corvallis OR 97331. Email: charles.murnieks@oregonstate.edu importance. Although research on the nature, causes, and consequences of entrepre- standing what motivates entrepreneurs is of both practical and theoretical neurial motivation has grown rapidly, it has evolved in distinct theoretical silos that tend to isolate motives based on the phase of business development (e.g., initiation, growth, and exit) rather than acknowledge that individuals often traverse all these phases and experience multiple types of motivation throughout their entrepreneurial journey. To advance the study of motivation in the fields of entrepreneurship and organizational behavior and provide a means through which these advancements can contribute to our understanding of how motivation drives the start‐up, growth, and exiting of businesses, we organize and review the extant literature on entrepreneurial motives based on the phases of the new venture process. In doing so, this article develops a roadmap of the current state of entrepreneurial motivation research and its nomological network and provides suggestions to guide future research in extending our understanding of motivation in the entrepreneurship domain as well as in traditional organizational settings. K E Y W OR D S entrepreneurial motivation, entrepreneurial passion, exit, growth, initiation 1 | I N T RO D U CT I O N motivation in organizations more generally. However, as the study of entrepreneurial motivation has proceeded, it has done so in a some- Motivation—the set of energetic forces that originate within as well as what unorganized manner, leaving us with an incoherent “big picture” beyond individuals to initiate behavior and determine its form, direc- of the role of motivation in the entrepreneurial process. tion, intensity, and duration (Mitchell & Daniels, 2003; Pinder, 1998) Studies of entrepreneurial motivation tend to focus on single —has been a core topic in psychological science and organizational phases of the business development process, namely venture initia- behavior (OB) for over a century (Kanfer, Frese, & Johnson, 2017; tion, growth, or exit. This approach has produced many insights into Mowrer, 1952). During this time, a number of subdomains within the why entrepreneurs act the way they do in each of these individual literature have emerged based on specific theories of motivation and phases. However, to borrow from Ployhart (2008, p. 54), “Frankly, upon how motivation operates in specific contexts. One particularly for most real‐world problems, who cares about motivation at a single active subdomain focuses on understanding what motivates entrepre- point in time?” Ployhart's sentiment may be especially true for entre- neurs to start, grow, and exit their ventures. This research, which preneurs as their motives can change between different phases of examines motivation in the distinct and often extreme entrepreneurial their endeavors. Indeed, entrepreneurs like Paul Allen (Microsoft) context, has not only advanced our understanding of what motivates and Yvon Chouinard (Patagonia) experienced significant shifts in their entrepreneurs but has also produced insights into the dynamics of motives over the course of founding and growing their organizations J Organ Behav. 2019;1–29. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/job © 2019 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 1 2 MURNIEKS ET AL. (Chouinard, 2005; Rich, 2003). Although studies based on different motivation in the field of OB. Regarding the field of entrepreneurship, phases explain unique aspects of entrepreneurial actions, focusing this review will (a) provide the field with a nomological network of the on one stage or another has left the field without a holistic framework causes, types, consequences, mechanisms, and moderators associated for understanding how various motives influence the entrepreneurial with entrepreneurial motivation; (b) build a framework to bridge the process. Moreover, although scholars acknowledge that management study of entrepreneurial motivation across the three phases of research needs to consider time explicitly as a pertinent variable the new venture process; (c) identify understudied motives, the direct (Shipp & Cole, 2015), when it is addressed, researchers tend to and moderating effects of which have the potential to explain mean- dedicate only a few paragraphs to motivation and temporal issues ingful variance in new venture outcomes; and (d) discuss methodolog- (Grant & Shin, 2012). Given the frequent and unpredictable change ical advances in other fields that may be useful to the study of inherent in entrepreneurial environments, this context provides an entrepreneurial motivation. Regarding the field of OB, this review will ideal setting in which to examine changes in motivation over time. (a) summarize what we have learned from studying motivation in the Also, studies of entrepreneurial motivation tend to emphasize either extreme context of entrepreneurship; (b) highlight aspects of entre- the role of endogenous factors like self‐regulatory or affective con- preneurial motivation that have the potential to advance our under- structs (e.g., identity congruence and entrepreneurial passion) or the standing of employee motivation more generally (e.g., passion); and influence of exogenous elements like goals or financial rewards as (c) provide a template for better understanding leader, team, and drivers of entrepreneurial behavior (Shane, Locke, & Collins, 2003). employee motivation across career transitions and organizational In other words, this research concentrates on either intrinsic or extrin- changes by reviewing entrepreneurial motivation research throughout sic motivators. On the one hand, considering intrinsic motives is novel the new venture process. in light of the traditional views of economists who focus on financial drivers of entrepreneurial action (e.g., Hebert & Link, 1988; Schumpeter, 1934). On the other hand, independently investigating 2 | OVERVIEW OF THE REVIEW intrinsic or extrinsic motivation may be misleading given research suggesting that both types of motives, and many others, drive Although some scholars highlight the need to examine certain areas of entrepreneurial behavior; indeed, the two can interact in powerful the entrepreneurial motivation literature more deeply (e.g., Carsrud & ways (e.g., Fauchart & Gruber, 2011; Powell & Baker, 2014). Brannback, 2011; Shane et al., 2003), no comprehensive review of the Moreover, despite evidence that extrinsic rewards can attenuate entrepreneurial motivation literature exists. We followed the proce- (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999) and facilitate (Cerasoli, Nicklin, & dures outlined by Shepherd, Williams, and Patzelt (2015) and Ford, 2014) intrinsic motivation, these contingent relationships have Hodgkinson and Ford (2014), to perform a systematic search for been insufficiently explored in the context of founding, growing, and articles to review. We conducted keyword searches in the Web of exiting organizations. Science and Business Source Premier databases across prominent Finally, investigating motivation in the entrepreneurial context pro- OB journals (Journal of Organizational Behavior, Journal of Applied vides the opportunity to take stock of what we currently understand, Psychology, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, question and extend theoretical boundaries, and highlight the need for and Personnel Psychology), management journals (Academy of Manage- (and inform the formation of) new theories of motivation. These ment Journal, Academy of Management Review, Administrative Science research opportunities arise in the entrepreneurial context given its Quarterly, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies, extreme nature; it is extreme in terms of its high uncertainty Management Science, Organization Science, and Strategic Management (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006), intense time pressure (Baron, 1998), Journal), and entrepreneurship journals (Entrepreneurship Theory and challenges associated with assembling resources (Baum & Locke, Practice, Journal of Business Venturing, Journal of Small Business 2004; Delmar & Wiklund, 2008), and elevated levels of organizational Management, Small Business Economics, and Strategic Entrepreneurship termination (DeTienne, McKelvie, & Chandler, 2015; Ucbasaran, Journal). Following directly from our definition of motivation, we Westhead, Wright, & Flores, 2010). In new ventures, relationships searched titles, keywords, and abstracts for articles containing any of between motivation and other affective, cognitive, and behavioral the words “entrepreneur” (entrepreneur*), “founder” (founder*), or constructs are brought into sharper focus by these extreme condi- “opportunity” (opportunit*) and any of the words “motivation” tions. Indeed, entrepreneurs represent a unique category of working (motiv*), “energy” (energ*), or “initiate” (initiat*). This search generated individuals; they make significant financial and psychological invest- a list of 520 articles, which we refined by excluding articles that ments in their organizations relative to other employees. Thus, in the did not investigate entrepreneurial motivation or when motivation entrepreneurial context, we can explore theoretical boundaries that was not central to the study. In total, we excluded 449 articles. As are obscured by perceptions of predictability and organizational stabil- shown in Table 1, we categorized the remaining 71 articles by venture ity more prevalent in the less entrepreneurial contexts of established, phase and motivation type and summarized the findings related in bureaucratic organizations. each study. In conducting a systematic review of the entrepreneurial motiva- The field of entrepreneurship examines how individuals discover, tion literature, we contribute to the study of motivation in the field evaluate, and exploit opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), of entrepreneurship and to the study of leader and employee which covers the continuum from starting businesses to growing them Phase Initiation Exit Growth Initiation Initiation Study Adkins, Samaras, Gilfillan, and McWee (2013) Akhter, Sieger, and Chirico (2016) Almandoz (2014) Almandoz (2012) Amit, MacCrimmon, Zietsma, and Oesch (2000) 51 founders 271 founding teams 225 founding teams 18 founders (49 firms) 432 founders Sample Motivation and entrepreneurial effects studies TABLE 1 X X X X X X X Intrinsic X EI interacta X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic X X X Intensity X Duration ET AL. (Continues) Wealth attainment is less important to entrepreneurs compared with other motives like innovation, vision, independence, and challenge. Founding teams motivated by financial logic are less likely to persist in founding a bank. Teams motivated by community logic are more likely to persist. In economic turbulence, teams high on both motives are less persistent. During economic stability, this interactive effect is reversed (i.e., it is positive). Financial logic motivation leads to focus on profit maximization and riskier strategies whereas community logic motivation leads to focus on community needs (and less on profits) as well as less risky strategies. Identity‐related motivations play a key role in the decision to shut down (vs. sell) a satellite venture. These relationships are moderated by goals to recycle assets, to restart the satellite, and performance decline. Entrepreneurial motivation to manage work‐life balance leads to increased work– family culture in the venture. Study findings MURNIEKS 3 Phase Growth Growth Growth Initiation Initiation Growth Baron, Mueller, and Wolfe (2016) Baum and Locke (2004) Baum, Locke, and Smith (2001) Benzing, Chu, and Kara (2009) Block, Sandner, and Spiegel (2015) Breugst, Domurath, Patzelt, and Klaukien (2012) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 124 employees 1,526 founders 139 founders 307 founders 229 founders 167 founders Sample X X X X X X Extrinsic X X X X Intrinsic EI interact a X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied X X X X Intensity Duration (Continues) Perceptions of entrepreneurs' passion for inventing and developing increase employee affective commitment; passion for founding reduces employee affective commitment. Entrepreneurs motivated by creativity are more willing to take risks. Extrinsic factors (income, security) are more important motives behind the choice to start a venture than intrinsic ones. Situation‐specific motivation mediates the effects of traits and competencies on venture growth. Motivation (in the form of communicated vision and goals) drives venture growth. Passion drives some types of motives, but it does not lead directly to venture growth. Self‐efficacy positively relates to goal difficulty, but is attenuated by self‐ control. Goal difficulty motivates higher firm growth, but this relationship is curvilinear (inverted). Study findings 4 MURNIEKS ET AL. Phase Initiation Growth Initiation, Growth Initiation, Growth Initiation, Growth Growth Initiation, Growth Brockner, Higgins, and Low (2004) Burmeister‐Lamp, Levesque, and Schade (2012) Cacciotti, Hayton, Mitchell, and Giazitzoglu (2016) Cardon, Post, and Forster (2017) Cardon, Gregoire, Stevens, and Patel (2013) Cardon and Kirk (2015) Cardon, Wincent, Singh, and Drnovsek (2009) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 Conceptual paper 129 founders 158 founders Conceptual paper 65 founders 25 founders Conceptual paper Sample X X X X X X X Extrinsic X X X X Intrinsic X EI interact a X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied X X Intensity X X X X Duration (Continues) Entrepreneurial passion motivates opportunity recognition, venture creation, and growth by enhancing creative problem solving, persistence, and absorption. Passion for both inventing and founding mediate the effect of self‐efficacy on persistence. Entrepreneurial passion for inventing and founding each motivate creativity. Entrepreneurial passion for developing motivates persistence. Team entrepreneurial passion motivates venture team performance and improves quality of team processes. Fear of failure motivates inhibition and withdrawal or persistence and striving behaviors. Promotion focus drives greater time investment when this results in greater risks, but lower time investment when this results in less risk. Prevention focus operates in the opposite manner. Promotion and prevention regulatory motivations provide advantages to distinct elements of venture initiation. Study findings MURNIEKS ET AL. 5 Phase Initiation Initiation Exit Growth Initiation Exit Carsrud and Brannback (2011) Chen, Yao, and Kotha (2009) Collewaert (2012) Delmar and Wiklund (2008) DeMartino and Barbato (2003) DeTienne et al. (2015) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 189 founders 497 founders 673 founders 72 founders 126 students (Study 1), 55 investors (Study 2) Review paper Sample X X X X X X X X X X X Intrinsic EI interacta X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic Intensity Duration MURNIEKS (Continues) Extrinsic motivation negatively relates to preference for stewardship exit strategies, but autonomous motivation positively relates to it. Regarding antecedents to entrepreneurial intentions, women entrepreneurs ranked family friendly policies, family obligations, and spouse employment higher than male entrepreneurs, and wealth creation lower than males. Growth motivation drives subsequent growth motivation and actual firm growth. Entrepreneurial motivation to exit is elevated when higher task and goal conflict are perceived between entrepreneurs and angel investors. Perceived affective passion among entrepreneurs does not influence decisions to invest in ventures; perceived cognitive passion (or preparedness) increases the desire to invest. Entrepreneurs can be motivated to start firms for intrinsic reasons or for external rewards (or both). Study findings 6 ET AL. Phase Exit Growth Growth Initiation Initiation Initiation Initiation DeTienne, Shepherd, and De Castro (2008) Drnovsek, Cardon, and Patel (2016) Dunkelberg, Moore, Scott, and Stull (2013) Edelman et al. (2010) Farmer et al. (2012) George, Kotha, Parikh, Alnuaimi, and Bahaj (2016) Gregoire and Shepherd (2012) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 98 founders (Study 1), 51 founders (Study 2) 1,049 households 563 nascent founders 401 founders 2,994 founders 122 CEOs 89 founders Sample X X X X X X X Extrinsic X X X Intrinsic EI interact a X X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied X Intensity X Duration (Continues) Motivation to start a business moderates the relationship between structural similarity and opportunity beliefs. Social structure disintegration in households motivates venture initiation actions. This effect is moderated by gender of the head of household. Entrepreneurial identity aspiration strength motivates discovery and exploitation behaviors. Expectancy beliefs are key motivators behind starting a venture, among a number of other intrinsic and extrinsic motivators underlying venture initiation. Nonmonetary goals motivate founders to use more of their own and family labor (and less employee labor). Goal commitment partially mediates the positive relationship between passion for developing and venture growth. Personal investments and high extrinsic motivation increase persistence with a failing firm; extrinsic motives increase the importance of personal options. Study findings MURNIEKS ET AL. 7 Phase Initiation Growth Initiation Initiation Growth Growth Grunhagen and Mittelstaedt (2005) Hallen and Pahnke (2016) Haynie and Shepherd (2011) Huyghe, Knockaert, and Obschonka (2016) Jaskiewicz, Combs, and Rau (2015) Kang, Matusik, Kim, and Phillips (2016) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 105 individuals 21 firms 2,308 researchers 10 founders 785 founders 192 founders Sample X X X X X X Extrinsic X X X X Intrinsic EI interact a X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Intensity Duration MURNIEKS (Continues) Risk‐taking climate moderates the relationship between passion for inventing and employee innovative behavior. Entrepreneurial “legacy” motivates incumbent and next‐generation owners to engage in strategic activities that foster transgenerational entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial passion motivates higher spin‐off and start‐up intentions. Obsessive scientific passion motivates spin‐off intentions. These relationships are mediated by entrepreneurial self‐ efficacy and affective organizational commitment. Motivations to become entrepreneurs after traumatic combat injuries include both push (e.g., physical and psychological limits) and pull (e.g., passion, competence, and security) motives. Motivation to access information positively relates to the accuracy of evaluations of venture capitalists. Intrinsic motivation (personal entrepreneurial ambition) is more prevalent among sequential multi‐unit founders (vs. area developer founders). Study findings 8 ET AL. Phase Exit Initiation Initiation Initiation Initiation Khan, Tang, and Joshi (2014) Kollmann, Stockmann, and Kensbock (2017) Kuhn and Galloway (2015) Li, Chen, Kotha, and Fisher (2017) McMullen and Shepherd (2006) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 Conceptual paper 170 students (Study 1), 180 students (Study 2), and 120 students (Study 3) 343 founders 71 students (Study 1), 204 nascent founders (Study 2), and 355 nascent founders (Study 3) 943 founders Sample X X X X X X X X X X Direction X EI interacta X Intrinsic Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic Intensity Duration (Continues) Entrepreneurial action is a function of perceived uncertainty and motivation. Entrepreneurial motivation determines the criteria used to decide whether third‐person opportunities represent first‐person opportunities as well. Displayed passion from entrepreneurs motivates crowdfunders to invest greater funding in the entrepreneurs' projects. Business motivation leads to higher value on promotion and business advice support. Creative expression motives lead to higher value on emotional support, friendship, and production advice. Business motives, not creative expression motives, positively relate to self‐rated performance. Fear of failure motivates more negative opportunity evaluation, through lower perceptions of desirability and feasibility. Entrepreneurial motivation (goal commitment) negatively relates to disengagement. This relationship is moderated by competitive intensity. Study findings MURNIEKS ET AL. 9 Phase Growth Initiation Initiation Initiation Growth Initiation Growth McMullen and Warnick (2015) Miller and Le Breton‐Miller (2017) Miller, Grimes, McMullen, and Vogus (2012) Mitteness, Sudek, and Cardon (2012) Moen, Heggeseth, and Lome (2016) Morgan and Sisak (2016) Morris, Miyasaki, Watters, and Coombes (2006) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 50 founders Conceptual paper 247 firms 64 angel investors Conceptual paper Conceptual paper Conceptual paper Sample X X X X X X X X X X X X Intrinsic EI interacta X X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic X X Intensity X X Duration MURNIEKS (Continues) Both extrinsic and intrinsic factors (e.g., desire to be rich, challenge, prove oneself, happiness, and satisfaction) and high identification with the business motivates high‐ growth founders, relative to modest‐growth founders. Fear of failure suppresses motivation to become an entrepreneur, but it can motivate additional investment by ambitious entrepreneurs. Growth motivation influences revenue and employment growth. Perceived passion among entrepreneurs results in higher evaluations of funding potential from prospective investors. Compassion motivates social entrepreneurship by working through the mechanisms of integrative thinking, prosocial cost‐benefit analysis, and commitment to alleviate others' suffering. Negative personal circumstances motivate adaptive efforts that may foster work discipline, risk tolerance, social skills, and creativity. Supporting the psychological needs of successors motivates them to commit to the family business. Study findings 10 ET AL. Phase Growth Growth Growth Initiation Initiation Mueller, Wolfe, and Syed (2017) Murnieks, Cardon, Sudek, White, and Brooks (2016) Murnieks, Mosakowski, and Cardon (2014) Naffziger, Hornsby, and Kuratko (1994) Patzelt and Shepherd (2011) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 Conceptual paper Conceptual paper 221 founders 53 investors 204 founders Sample X X X X X Extrinsic X X X Intrinsic EI interact a X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied X X X Intensity Duration (Continues) Motivations to address threats to the natural/ communal environments, and motivations to help others drive recognition of opportunities for sustainable development. Entrepreneurial motivation is a function of an entrepreneur's personal characteristics, personal environment, personal goals, the business environment, the idea, and intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. Identity centrality drives entrepreneurs' passion, which relates to self‐ efficacy and entrepreneurial behavior. Angel investors rate ventures more favorably to the extent the founder is passionate about the venture. This relationship is moderated by investor entrepreneurial experience. Passion for developing ventures positively relates to grit, which positively relates to venture performance. Locomotion and assessment orientation mediate the relationship between passion and grit. Study findings MURNIEKS ET AL. 11 Phase Growth Initiation Initiation, Growth Growth Initiation Initiation Initiation Powell and Baker (2014) Renko (2013) Spivack, McKelvie, and Haynie (2014) Stenholm and Renko (2016) Stewart and Roth (2007) Townsend and Hart (2008) Van Gelderen, Kautonen, and Fink (2015) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 161 individuals Conceptual paper Meta‐analysis 2,489 founders 2 founders 193 nascent founders 13 firms Sample X X X X X X X X X X X Intrinsic X EI interacta X X X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic Intensity X Duration MURNIEKS (Continues) Self‐control and doubt negatively moderate the relationship between entrepreneurial intention/ motivation and action. The combined economic and social goals of founders motivate selection of organizational formation as a for‐profit or non‐ profit firm. Entrepreneurs exhibit significantly higher achievement motivation than managers. Passion for inventing and passion for developing increase bricolage, which increases entrepreneurial survival. Behavioral addiction can motivate entrepreneurial addiction among habitual entrepreneurs, which can manifest into other compulsive behaviors and psychological/ physiological problems. Social motivation leads to lower progress toward firm emergence. Entrepreneurs enact different definitions of adversity through distinct identities, which motivate unique ways in which they use their firms to defend who they are or to become who they want to be. Study findings 12 ET AL. Phase Growth Initiation Initiation Initiation Initiation Vik and McElwee (2011) Webb, Bruton, Tihanyi, and Ireland (2013) Weber, Heinze, and DeSoucey (2008) Westhead, Ucbasaran, Wright, and Binks (2005) Williams and Shepherd (2016) (Continued) Study TABLE 1 12 founders (6 firms) 354 founders 24 founders Conceptual paper 943 individuals Sample X X X X X Extrinsic X X Intrinsic EI interact a X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Intensity X Duration (Continues) In the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake (2010), two types of ventures emerged, motivated by desires to either sustain basic needs or facilitate transition toward autonomy and self‐ reliance. Motivations can change over time, especially for PE or SE. Compared with novices, PEs reported personal wealth and intrinsic motives like being challenged more often, whereas SEs cited intrinsic motives like controlling their own time more often. Entrepreneurs choose and persist with ventures because they obtain energy from connecting their work to a sense of self and moral values. Motivation to engage in informal entrepreneurship activities (illegal but not antisocial) can result in both productive and destructive outcomes. Both social and economic motivations drive diversification of activities from original business. Study findings MURNIEKS ET AL. 13 Initiation Initiation Initiation Growth Initiation Witt (2007) Woo, Cooper, and Dunkelberg (1991) Wood, McKelvie, and Haynie (2014) Yamakawa, Peng, and Deeds (2015) York, O'Neil, and Sarasvathy (2016) 25 founders 203 founders 35 founders 510 founders Conceptual paper Sample X X X X X a Indicates Extrinsic × Intrinsic motivation interaction was considered in this paper X X X X Intrinsic EI interacta X X X X X Direction Motivation type and characteristics studied Extrinsic Abbreviations: EI, extrinsic‐intrinsic interaction; PE, portfolio entrepreneur; SE, serial entrepreneur. Phase (Continued) Study TABLE 1 Intensity Duration Commercial and ecological logics motivate environmental entrepreneurs in different manners. Inclusive, exclusive, and co‐created approaches relate to the entrepreneurial motivation. Internal attribution of blame after venture failure and intrinsic motivation to start again drive growth in subsequent business. Task motivation moderates the relationships between industry conditions and knowledge relatedness, and founder willingness to pursue an opportunity. Cluster analyses reveal that different entrepreneurs are motivated by different intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Different methods of classification can increase or decrease the separation of these clusters. Intrinsic motivation relates to initiative, creativity, problem‐solving, and improved task performance among new venture employees. Study findings 14 MURNIEKS ET AL. MURNIEKS 15 ET AL. and then exiting from them (e.g., Fisher, Kotha, & Lahiri, 2016). Across depict a much richer nomological network surrounding entrepreneurial these phases, entrepreneurs experience different types and levels of motivation in the initiation (Figure 2) and growth (Figure 3) phases motivation depending on whether they need to engage in initiation, compared with the exit phase (Figure 4). growth, or exit activities. As our review indicates, however, extant Next, following the roadmap provided by Figure 1, we review research is unbalanced in its treatment of motivation during these research on entrepreneurial motivation during new venture initiation, entrepreneurship phases. Scholars have dedicated considerably more growth, and exit. Within each section, we discuss the different theo- effort to studying the motives behind venture initiation compared ries and types of motivation as well as the antecedents, consequences, with those that drive growth or exit. This imbalance is not necessarily and moderators of entrepreneurial motives. Each section culminates surprising as researchers acknowledge that a defining characteristic of with a discussion of future research opportunities. entrepreneurship as a field is the phenomenon of new venture initiation and understanding how and why entrepreneurs are driven to give them life (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). As shown in Table 1, 68% (48 articles) of the entrepreneurial 3 | ENTREPRENEURIAL MOTIVATION DURING VENTURE INITIATION motivation literature focuses on the venture initiation phase, whereas 27% (19) focuses on the growth phase, and only 5% (4) focuses on the Figure 2 provides an overview of research on the motives and out- exit phase. Most of this research stream is empirical; indeed, 77% (55) comes related to the initiation phase of entrepreneurship. The most of the papers develop and test hypotheses. Of the 14 conceptual arti- prevalent type of motivation studied is extrinsic, particularly, eco- cles, 93% (13) concentrate on venture initiation. To better understand nomic and financial incentives (e.g., Benzing et al., 2009). Other extrin- the network of concepts that scholars have examined in the literature, sic entrepreneurial motives include social equity (Renko, 2013), we model the different constructs and relationships represented, and ecological preservation (York et al., 2016), and work–family balance organize them by entrepreneurial phase. The unevenness of scholarly (Adkins et al., 2013); however, these motives have received far less activity across the three phases is apparent in Figures 2–4, which scholarly attention than economic drivers of entrepreneurship. Studies FIGURE 1 Overview of entrepreneurial motivation across three phases of new venture process 16 MURNIEKS FIGURE 2 Entrepreneurial motivation during venture initiation FIGURE 3 Entrepreneurial motivation during venture growth have also examined intrinsic motives related to identity (Farmer, Yao, ET AL. beyond simply starting a new business. Indeed, studies have investi- & Kung‐Mcintyre, 2011), moral values (Weber et al., 2008), and emo- gated the types of new ventures started (e.g., for‐profit vs. non‐profit; tions (e.g., passion or fear of failure; Cardon et al., 2013; Morgan & Townsend & Hart, 2008), the types of entrepreneurial activities under- Sisak, 2016) as forms of entrepreneurial motivation. Researchers have taken (e.g., legal vs. informal; Webb et al., 2013), and entrepreneurs' explored how entrepreneurial motives shape founder behaviors behaviors during initiation (Dunkelberg et al., 2013). FIGURE 4 Entrepreneurial motivation during venture exit MURNIEKS 3.1 | 17 ET AL. Economic motivations for venture initiation typically considered antisocial (e.g., employing undocumented workers or street vending). The extent to which formal economies oppress At the most general level, the motivation to start a business drives individuals' abilities to earn profits can motivate entrepreneurs to subsequent entrepreneurial activity (e.g., Herron & Sapienza, 1992; engage in informal venturing (Webb et al., 2013). Although economic McMullen & Shepherd, 2006; Van Gelderen et al., 2015); that said, motives may drive entrepreneurs to organize for‐profit firms, social more specific motivations underlie this general motivation. Early writ- motivation can encourage nonprofit structures (Townsend & Hart, ings from economists theorize that the primary motive for entrepre- 2008). Various combinations of economic and intrinsic motives, neurship is the prospect of financial gain (Cantillon, 1931; Casson, including desires to mitigate risk exposure, can prompt entrepreneurs 1982; Hebert & Link, 1988; Knight, 1921; Schumpeter, 1934). to pursue portfolio entrepreneurship (owning multiple businesses at Although many conceptual papers embrace the importance of this one time) or serial entrepreneurship (starting a new venture after clos- type of motivation (e.g., Naffziger et al., 1994), empirical data does ing or exiting a previous one; Cruz & Justo, 2017; Westhead & Wright, not support economic motivation as the primary driver of entrepre- 1998). Collectively, this research lends credence to the notion that neurship (Block et al., 2015; Woo et al., 1991; Yitshaki & Kropp, entrepreneurial motivation drives decisions to initiate ventures and 2016). To this point, a study by Amit et al. (2000) indicates that of shapes the type of ventures that emerge. 11 different entrepreneurial motives, the desire to attain wealth ranks last in importance, behind noneconomic desires, such as achieving independence, making a contribution, and being innovative. Even if they are not the primary reason entrepreneurs start businesses, eco- 3.2 | Noneconomic and intrinsic motivations behind venture initiation nomic motives still play an important role. Indeed, when entrepreneurs look to enter new markets and start businesses, they understand the As mentioned earlier, entrepreneurs often rank noneconomic and importance of earning enough money to make a living (Weber et al., intrinsic entrepreneurial motives, such as achieving independence, 2008; Westhead & Wright, 1998). As such, economic motives may overcoming challenges, and being innovative, higher than economic represent a necessary but insufficient condition to start a venture ones (Amit et al., 2000). Indeed, the forces that motivate venture (Weber et al., 2008). initiation include a diverse range of personal desires, such as self‐ Although profits may not be the primary driver of venture initia- realization, independence, innovation, recognition, and family tradition tion, there are factors that increase the salience of economic motives (Edelman, Brush, Manolova, & Greene, 2010; Westhead & Wright, among entrepreneurs. For example, changes in the economic climate 1998). In particular, family desires can motivate founders to establish can elevate the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial activity. ventures with positive work–family cultures (Adkins et al., 2013). Research conducted in emerging markets shows that shocks to house- Other important noneconomic and intrinsic motives include identity hold social structures (e.g., from calamities like the death of the head and ancestry, patriotism, and prosocial concerns (Williams & Shepherd, of the family) drive frantic searches for new sources of income, includ- 2016). Indeed, prosocial motives are an emerging area of interest ing entrepreneurship (George et al., 2016). Relatedly, negative across entrepreneurial motivation research (e.g., Miller et al., 2012; personal circumstances that adversely impact individuals' income or Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Renko, 2013). Scholars theorize that career advancement may also motivate compensation through prosocial motives activate entrepreneurs' cognitive and affective entrepreneurship (Miller & Le Breton‐Miller, 2017). For instance, processes related to integrative thinking, prosocial judgments, and immigrants who lack linguistic skills or education or individuals commitment to alleviating others' suffering, which in turn drive who face obstacles to traditional employment may be particularly subsequent social venturing (Miller et al., 2012). Researchers have also motivated to undertake entrepreneurial activity (Haynie & Shepherd, analyzed how different prosocial motivations trigger actions to allevi- 2011; Miller & Le Breton‐Miller, 2017). The possibility of raising one's ate the suffering of others, which drives the formation of different earning potential can also increase individuals' motivations to initiate venture types (Williams & Shepherd, 2016). Although prosocial moti- ventures and to allocate more time toward start‐up activities, vation plays a role in firm emergence, it may also slow the speed of especially if they are promotion (versus prevention) focused the initiation process, especially for products that are new to market (Burmeister‐Lamp et al., 2012). Taken together, these studies highlight (Renko, 2013). Intrinsic motives also drive the formation of franchises how economic motives to engage in entrepreneurship should be (Grunhagen & Mittelstaedt, 2005) and other new ventures (Almandoz, viewed from a contingency perspective that accommodates salient 2012; Block et al., 2015). contextual and personal factors. Identity‐related motives can drive entrepreneurial action during Economic motives not only drive the decision to start a business the initiation phase. For instance, entrepreneurial identity aspirations but can also shape the form of entrepreneurship undertaken. For motivate opportunity discovery and exploitation behaviors (Farmer example, some entrepreneurs operate outside the formal economy et al., 2012). Moreover, entrepreneurs' motivation to enter and persist (i.e., informal or illegitimate entrepreneurship) because they seek to in difficult industries often stems from a deep emotional connection to satisfy subsistence needs, accumulate wealth, or avoid excessive taxes their actions, such as congruence between the venture's mission and (Webb et al., 2013). Informal entrepreneurship includes activities that the entrepreneur's identity and values (Weber et al., 2008). Related occur beyond traditional institutional boundaries but that are not theoretical efforts also shed light on the impact of individuals' desires 18 MURNIEKS to achieve congruence between ideal or ought identities on their entrepreneurial behavior, and how this tension impacts opportunity ET AL. 3.5 | Integrating intrinsic and extrinsic entrepreneurial motives recognition and venture formation (Brockner et al., 2004). Just as contextual variables might increase the salience of economic motives, Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations drive venture formation, and both these same factors may stoke prosocial and intrinsic motives (Patzelt should be considered conjointly to determine their effects on venture & Shepherd, 2011). initiation and performance (Kuhn & Galloway, 2015). Among environmental entrepreneurs, it is common for both commercial (economic) and ecological logics to drive venture formation (York et al., 2016). This trend is mirrored among commercial, serial, and portfolio entre- 3.3 | Entrepreneurial passion and venture initiation preneurs, with similar dualities between extrinsic and intrinsic motives spurring venture initiation (Almandoz, 2012, 2014; Carter & Ram, Entrepreneurial passion refers to consciously accessible and intense 2003; Weber et al., 2008; Westhead et al., 2005). That said, scholars positive feelings experienced by engaging in activities associated note that motivation profiles among different types of entrepreneurs with entrepreneurial roles (Cardon et al., 2009). In other words, pas- may vary. For example, portfolio entrepreneurs may be more sion is an intense identity‐related emotion that can have powerful motivated by extrinsic factors related to wealth and financial consider- motivating effects. In general, entrepreneurial passion motivates ations than serial or first‐time entrepreneurs (Westhead & Wright, higher intentions to start a new business (Cardon et al., 2009, 2013; 1998). Kuhn and Galloway (2015) find that a combination of intrinsic Huyghe et al., 2016) and can stimulate the inventive use of available and extrinsic motives lead to higher business performance than resources (i.e., bricolage), which leads to greater persistence during intrinsic motives alone. Similarly, in a study of the influence of financial venture creation (Stenholm & Renko, 2016). Passion also motivates (i.e., extrinsic) and community (i.e., a blend of intrinsic and extrinsic) both creativity and persistence at entrepreneurial endeavors (Baron, logics in driving entrepreneurial behaviors, financial logics led to lower 2008; Cardon et al., 2013) and serves as a mechanism linking entrepreneurial persistence than community logics (Almandoz, 2012). self‐efficacy and persistence (Cardon & Kirk, 2015). Importantly, an Thus, questions still exist about the relative contributions of and entrepreneur's passion for venture initiation can manifest itself as a interactions between motivations (intrinsic and extrinsic) and venture positive signal to investors about his or her motivation (Davis, initiation. Moreover, these findings raise questions about the relative Hmieleski, Webb, & Coombs, 2017; Hsu, Haynie, Simmons, & level of endurance driven by different types of motivation, especially McKelvie, 2014; Li et al., 2017; Warnick, Murnieks, McMullen, & because endurance is an important but relatively neglected dimension Brooks, 2018). Investors are particularly attracted to entrepreneurs of entrepreneurial motivation. In one exception, Khan et al. (2014) who demonstrate passion by preparing logical, coherent presentations find that goal commitment helps entrepreneurs maintain their rather than effusive ones (Chen et al., 2009). These findings indicate motivation during the start‐up process. As described above, both how entrepreneurial motivation may inspire action from other key intrinsic and extrinsic motivations can drive entrepreneurs to start stakeholders to the venture. Moving up one level of analysis, concep- ventures (e.g., Carsrud & Brannback, 2011), and many studies have tual research proposes that entrepreneurial passion influences new assessed both motives simultaneously (e.g., Amit et al., 2000; Block venture team member exit and entry, team processes, and team et al., 2015; Dunkelberg et al., 2013; Weber et al., 2008). However, performance (Cardon et al., 2017) as well. the relative contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic motives to venture initiation remains unclear because scholars have rarely explored interactions between them. 3.4 | Fear of failure and venture initiation 3.6 | Venture initiation dependent variables Fear of failure also associates with entrepreneurial motivation, but unlike passion, its effects are typically negative (e.g., Arenius & Beyond venture launch, scholars have explored other effects of entre- Minniti, 2005; Langowitz & Minniti, 2007; Li, 2011; Minniti & preneurial motivation during venture initiation. For example, individ- Nardone, 2007). For example, fear of failure may hamper opportu- uals' receptiveness to different types of risk is an important nity evaluation and exploitation motives by lowering perceptions of precursor to firm formation (Janney & Dess, 2006), and research the desirability and feasibility of entrepreneurial opportunities shows that extrinsic desires to earn high incomes increase entrepre- (Kollmann et al., 2017). That said, there is a bright side to fear of neurs' willingness to take risks, especially in opportunity‐driven (rela- failure when it comes to entrepreneurial motivation. Although fear tive to necessity‐driven) entrepreneurs (Block et al., 2015). Similarly, of failure arouses feelings of threat, which can dampen entrepre- economic motivations lead to riskier strategic behaviors during new neurial action, under some circumstances, it can motivate increased venture founding, whereas noneconomic motivations lead to more entrepreneurial behavior and persistence (Cacciotti et al., 2016), conservative strategic behaviors (Almandoz, 2014). Also, entrepre- especially in nascent entrepreneurs with high aspirations of career neurs whose primary motivations are nonfinancial (versus financial) success (Morgan & Sisak, 2016). work longer and use higher levels of family labor vis‐à‐vis employee MURNIEKS 19 ET AL. labor to initiate their ventures (Dunkelberg et al., 2013). Regarding the heterogenous motives among team members may obstruct team‐level effect of entrepreneurial motivation on opportunity evaluation, it motivation and contribute to team dysfunction and diminished ven- appears that higher task motivation aimed at assessing opportunities ture performance. Similarly, future research can explore the effect of attenuates the impact of certain negative industry indicators on team‐level motivation on both individual‐level outcomes (e.g., motives, opportunity viability (Wood et al., 2014). Also, explorations of the link aspirations, and effort) and venture‐level outcomes (e.g., venture between motivation and opportunity beliefs indicate how the motiva- emergence and strategy). Indeed, future studies can complement pre- tion to start a business strengthens the relationship between vious research on differences in individuals' motivation (i.e., between‐ opportunity‐evaluation cognitions and the formation of opportunity person differences in motivation) with a temporal perspective on how beliefs (Gregoire & Shepherd, 2012). Finally, limited research into the individuals' motives change over time with the emergence of the ven- dark side of entrepreneurial motivation shows how motivation can ture, the emergence of the team, and the accumulation of experience transform into addiction (Spivack et al., 2014). Researchers investigat- (i.e., within‐person change in motivation). ing the obsessive form of passion in entrepreneurship also explore Finally, entrepreneurial motivation research is largely unidirectional addiction although generally, these studies do not assess the dysfunc- in terms of examining the effect of motives on entrepreneurial behav- tional aspects of this type of motivation (Huyghe et al., 2016; iors. Yet, there are opportunities to explore the reciprocal mechanism: Murnieks et al., 2016). how behavior influences motivation (e.g. Gielnik, Spitzmuller, Schmitt, Klemann, & Frese, 2015). For example, learning from trial and error (i.e., action‐generating feedback) can enhance motivation under some conditions (and demotivate under different conditions), thereby 3.7 Entrepreneurial motivation and venture initiation: Directions for future research | forming a spiral of motivation and trial‐and‐error learning. The research questions then become what starts, perpetuates, and stops Although economic motivation has been the most heavily studied these motivation‐behavior spirals? No doubt there are other mutually driver of venture initiation activity, intrinsic motives, prosocial reciprocal, or feedback relationships, that involve various motives, and motives, and entrepreneurial passion also stimulate behavior during their exploration could enrich our understanding of entrepreneurial this phase (e.g., Amit et al., 2000; Cardon et al., 2009; Williams & motivation. Shepherd, 2016). Collectively, this research has produced deep insights into the actions emanating from different types of motivation; however, scholars rarely analyze interactions between intrinsic and extrinsic entrepreneurial motives (e.g., George, 2007). This 4 | ENTREPRENEURIAL MOTIVATION D U R I N G V E N T U R E G RO W T H understudied topic represents an opportunity to understand when and why these two types of motives act in a complementary versus The scholarly attention given to the role of entrepreneurial motivation an oppositional manner. For example, the desire for financial gain in the growth phase of new ventures pales in comparison with the might work in concert with passion for social venturing. It would be stream of research focusing on entrepreneurs' motivation to start a insightful to know how entrepreneurial start‐up behavior is affected when intrinsic and extrinsic motives are congruent with identity values versus when they are incongruent. Another area of fruitful inquiry is the interaction between intrinsic motivation and other types of externally focused motives such as prosocial ones. Our review highlights the growing emphasis on prosocial motivation as a driver of venture initiation behaviors (e.g., Miller et al., 2012; Williams & Shepherd, new venture. As depicted in Figure 3, economic, intrinsic, identity congruence, social, and entrepreneurial passion motives are prominent drivers of venture growth in addition to playing a similar role in venture initiation. Although scholars tend to emphasize economic motives for venture initiation, studies exploring the growth phase tend to focus on intrinsic motives and entrepreneurial passion. Next, we take a finer‐grained look at this research. 2016). However, emerging research in OB indicates prosocial and intrinsic motives may interact with powerful consequences, 4.1 | Entrepreneurial passion and venture growth including behaviors relevant to venture initiation such as creativity, persistence, and productivity (Bolino & Grant, 2016; Grant, 2008; Similar to research on entrepreneurial motivation during venture Grant & Berry, 2011). initiation, scholars have sought to understand how entrepreneurial The venture initiation literature largely focuses on the motivation passion relates to behavior and venture performance during the of the focal entrepreneur. This approach overlooks the perspective growth phase. The findings reveal that when founders' identities as that teams launch most ventures (Klotz, Hmieleski, Bradley, & entrepreneurs are central to their sense of self, they feel more pas- Busenitz, 2014). Therefore, it is important that we gain a deeper sionate, leading to increased self‐efficacy and to changes in behavior. understanding of new venture team motivation. For example, how More specifically, entrepreneurial passion positively relates to the time do individual motives become team motives and to what effect? Per- founders invest in their ventures during the growth phase (Murnieks haps a venture team possessing heterogeneous motives develops a et al., 2014). Subsequent research extends these findings and shows collective entrepreneurial motivation to enthusiastically undertake that passion corresponds to higher perseverance (i.e., grit) and that the many different tasks necessary for venture initiation. However, entrepreneurial grit relates to firm growth (Mueller et al., 2017). 20 MURNIEKS ET AL. Entrepreneurial passion also drives entrepreneurs to set challenging McElwee (2011) examine the effect of entrepreneurial motivation on goals and remain committed to them, which contributes to firm a specific facet of venture growth—diversification of business activi- growth (Drnovsek et al., 2016). Further, entrepreneurs can establish ties—and find that different motives for growth drive different types organizational climates suffused with innovation, proactivity, and risk of diversification. For example, entrepreneurs who are motivated to taking such that their employees develop passion that drives increased be creative are more likely to grow by branching out into tourism levels of innovative behavior (Kang et al., 2016). In sum, passion moti- and other miscellaneous activities, whereas those who hold social vates entrepreneurs to roll up their sleeves and work extraordinarily yearnings are more likely to expand with initiatives that build a sense hard to grow their ventures. of community (e.g., farming for health). This study shows how consid- In line with work highlighting the link between entrepreneurial pas- ering different forms of firm growth can elucidate how entrepreneurial sion and investor decisions, limited research indicates that passion is motives contribute during this phase (Vik & McElwee, 2011). Second, also useful for securing funding to fuel future growth. Mitteness Powell and Baker (2014) develop a grounded theory of how identity‐ et al. (2012) find that the relationship between angel investors' per- based motives affect entrepreneurs' responses to adversity. In explor- ceptions of entrepreneurial passion and their funding decisions is ing 13 firms facing business adversity, the authors discern patterns of more positive when angels are motivated to mentor entrepreneurs, identity configurations reflecting differences in the way entrepreneurs indicating that entrepreneurs' passion may make investing particularly view the same adversity and thus their motivations to transform, sus- attractive to outsiders who are motivated to help. Entrepreneurial tain, or shrink their ventures. experience also influences the relationship between entrepreneurial Finally, entrepreneurs' growth motivation—their desire to expand passion and the likelihood of investment; passion is a more potent their firms—should relate to firm growth (Delmar & Wiklund, 2008; predictor of angel investment when combined with entrepreneurial Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003), subject to some boundary conditions. experience (Murnieks et al., 2016). Research on growth motivation in a global business setting provides evidence that the strength of the relationship between growth motiva- 4.2 | Entrepreneurs' intrinsic motives and venture growth In addition to entrepreneurial passion, researchers have paid substantial attention to the effect of intrinsic motives on venture growth. Recent conceptual work advances the idea that one path via which family businesses grow over time is the transmission of intrinsic motivation from parents to their children stemming from working in the tion and actual growth depends on the degree to which the firm's orientation matches the business environment (Moen et al., 2016). That is, even if an entrepreneur has a strong growth motivation, if his or her firm does not possess an international orientation, the firm will struggle to grow, suggesting that high levels of growth may only arise when growth motivation matches the firm's orientation (Moen et al., 2016). As such, it is important to consider the fit between different types of motivation and the context of the organization's environment. venture (McMullen & Warnick, 2015). Specifically, as children satisfy their basic psychological needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence by working with their parents, their entrepreneurial motivation is stoked, and they become more likely to pursue a career within the family business (McMullen & Warnick, 2015). Empirical work further supports the notion that to the extent that entrepreneurs experience intrinsic motivation during the growth phase, their ventures benefit. Indeed, one study finds that female entrepreneurs' motivation to challenge themselves leads to a growth orientation that positively impacts venture growth, providing evidence that extrinsic desires contribute to entrepreneurs' growth orientations beyond the effect of intrinsic factors (Morris et al., 2006). Intrinsic motivation also influences the growth of ventures launched after a prior failure. Specifically, intrinsic motivation acts as a persistence mechanism that, along with the learning associated with accepting blame for the prior failure, leads to higher growth in subsequent ventures (Yamakawa et al., 2015). 4.4 | Socioemotional wealth and venture growth A sizable body of family business literature focuses on the effects of socioemotional wealth (SEW) on venture growth and performance. Because recent and comprehensive reviews of the SEW literature exist (e.g., Berrone, Cruz, & Gomez‐Mejia, 2012; Jiang, Kellermanns, Munyon, & Morris, 2018), we did not include SEW articles in our formal review; here, we briefly discuss this body of work and its connection to entrepreneurial motivation. SEW refers to nonfinancial aspects of owning a venture that satisfy a family's social and affective needs such as independence or power, or the perpetuation of a family legacy or dynasty (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez‐Mejia, Haynes, Nunez‐Nickel, Jacobson, & Moyano‐Fuentes, 2007). As such, SEW is motivational because it is tied to family business owners' identities (Berrone, Cruz, Gomez‐Mejia, & Larraza‐Kintana, 2010; Jiang et al., 2018), and family business entrepreneurs often manage their firms 4.3 | Additional research on entrepreneurial motivation and venture growth not to maximize financial outcomes, but to preserve or increase SEW (Gomez‐Mejia, Cruz, Berrone, & DeCastro, 2011; Kets de Vries, 1993; Miller & Le Breton‐Miller, 2014). Moreover, the motivation to Several additional studies not only contribute to our understanding of protect SEW can drive both increasingly conservative or risky the role that entrepreneurial motivation plays in venture growth but decision‐making, depending on how entrepreneurs feel SEW might also highlight distinct ways to study this relationship. First, Vik and be threatened (Gomez‐Mejia et al., 2007; Miller & Le Breton‐Miller, MURNIEKS 21 ET AL. 2014). Given that SEW combines intrinsic and extrinsic motives to entrepreneur's and the venture's motives. For example, how do explain family firms' growth and performance (Cennamo, Berrone, changes in organizational size affect intraindividual and intraventure Cruz, & Gomez‐Mejia, 2012), it can contribute to our understanding motivations over time? It is important to develop and test dynamic of motivation in entrepreneurial and traditional firms. models of motivation throughout the venture growth phase at the individual, team, and venture levels as well as across levels of analysis. Specifically, future research can make important contributions to the 4.5 Entrepreneurial motivation and venture growth: Directions for future research | entrepreneurship and OB literatures by understanding the various causes of these changes and their different effects. The growth stage of the entrepreneurial process has arguably more in common with management in traditional settings than venture initiation or exit. Hence, to expand our understanding of the dynamics of 5 | ENTREPRENEURIAL MOTIVATION AND VENTURE EXIT entrepreneurial motivations during this phase, scholars should consider capturing the antecedents and effects of the additional forms A paucity of research examines the role of motivation in the exit phase and foci of entrepreneurial motives during the growth phase. In addi- of the entrepreneurial process. On the one hand, the relative dearth of tion to exploring intrinsic, extrinsic, and growth motivation, there are studies focused on founder motivation during this final phase of the opportunities to contribute to the literature by examining entrepre- entrepreneurial journey is not surprising given that exit has received neurs' motivation to help others (i.e., prosocial motivation) or make far less attention across the entrepreneurship literature than the themselves look good (i.e., impression management motives). Such nascent and early stages (e.g., DeTienne, 2010; DeTienne & Cardon, research on prosocial motivation and/or impression management can 2012). On the other hand, given the volumes of organizational research shed light on why some founders focus their energy on helping others focused on the role of motivation in employee exits (i.e., voluntary and during the growth phase whereas others choose to focus on the involuntary turnover), it is somewhat unexpected that few authors have external reputation of their firms. For example, in the aftermath of a shined a spotlight on the motivational forces surrounding entrepre- disaster, entrepreneurs may be highly motivated to grow their ven- neurial exit. Moreover, because exits sometimes culminate in a financial tures to alleviate the suffering of those outside their ventures. Future windfall that allows entrepreneurs to realize the fruition of economic research can explore the complementary (or competing) motivations motives to enter entrepreneurship, it is surprising that more studies (e.g., extrinsic and prosocial; intrinsic and prosocial) to grow a venture. have not analyzed this phase. As Figure 4 shows, researchers have stud- What is the nature of the relationships between extrinsic, intrinsic, ied extrinsic, intrinsic, and identity‐congruence motives in this phase. and prosocial motivations in growing a venture to increase sales, Extrinsic drivers related to economic and utility maximization are increase the number of employees, take on more challenging markets, among the most common motivations attributed to entrepreneurial and alleviate more suffering? Given the prevalence of entrepreneurial exit. Scholars contend that entrepreneurs often choose to exit because teams, it is also important to explain heterogeneity in the strength of they seek to liquidate their investment in the current firm or view different types of motivation among team members and the way indi- alternative employment as more attractive (Bates, 2005; Douglas & vidual motives come together to drive venture performance. Shepherd, 2000; Wennberg, Wiklund, DeTienne, & Cardon, 2010). Second, in growing a venture, team members interact with each Some of the deepest insights on motivation during venture exit come other and with outside stakeholders. For example, an entrepreneurial from entrepreneurs who resist exit despite underperformance, which team may interact with a community of inquiry to co‐construct an highlights the potential richness of examining motives toward delaying opportunity (Shepherd, 2015). This interaction and progress in co‐ the end of a given entrepreneurship episode (DeTienne et al., 2008; construction may lead to changes in the motives of the new venture Gimeno, Folta, Cooper, & Woo, 1997). Indeed, when entrepreneurs team (and the community of inquiry). For instance, interactions with ponder the decision of whether to continue or exit an underperforming members of the community of inquiry regarding a technology may firm, their personal investment in the venture, previous organizational reveal suffering that the technology (with refinement) may be able to success, and the munificence of the operating environment positively alleviate, and such a realization may generate prosocial motivation. relate to entrepreneurs' motivation to persist rather than exit. Impor- Alternatively, working with the community of inquiry to solve a com- tantly, extrinsic motivation can influence the relationships between plex problem may make the team realize the benefits of satisfying their these antecedents and the exit‐versus‐persist decision; when entrepre- intrinsic motives to solve complex problems. Future research can neurs are extrinsically motivated, they may be less likely to consider the explore how changes to the venture and the individuals within the importance of personal investment, collective efficacy, and environmental growth phase may lead to changes in the intensity, form, and interac- munificence in their “stay or go” decisions (DeTienne et al., 2008). As such, tion of entrepreneurial motivation. intrinsic and extrinsic motives sometimes play countervailing roles in Finally, although much of the entrepreneurial motivation research focuses on motivation at one point in time and implicitly assumes that the exit process, which highlights how constructs such as SEW can contribute to our understanding of motivation during this phase. motivation has a rather static form and intensity, the growth phase Not all founder exits are alike. Indeed, scholars have classified brings about many changes, which likely lead to alterations in the founder exits as financial harvest strategies (e.g., initial public offering 22 MURNIEKS ET AL. or sale), stewardship strategies (e.g., transfer or sale to family or assess these motivations precisely. Because of the relatively wide‐ employees), and voluntary cessation strategies (e.g., liquidation or open nature of the question of what happens to motivation and pas- retirement; Chevalier, Fouquereau, Gillet, & Bosselut, 2018; DeTienne sion during the exit process, qualitative studies using grounded theory et al., 2015; Wennberg et al., 2010). Reports such as the one published approaches (Murphy, Klotz, & Kreiner, 2017) may be particularly use- annually by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor highlight how across ful for understanding the different ways entrepreneurs experience this the world, founders cite a wide spectrum of reasons for exit. These process. Also, although the decision to exit one's venture is distinct include financial difficulties, other promising opportunities, bureau- from that of the decision to quit one's job, insights from studies on cracy, and retirement (e.g., see Table 4, GERA, 2018). Indeed, scholars the factors that lead to employee turnover (and burnout) may prove have theorized that myriad factors could influence exit motivations useful in building and testing theory related to the role of entrepre- including age, education, entrepreneurial experience, industry experi- neurial motivation in the venture exit process. One of the most pow- ence, human capital, firm performance, switching costs, and opportu- erful theories for explaining why employees voluntarily leave nity costs to name a few (e.g., Bates, 2005; Gimeno et al., 1997; organizations is the unfolding model of turnover (Lee & Mitchell, Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014). Looking specifically at the influence 1994), which posits that the decision to quit often begins with some of equity investors on exit, Collewaert (2012) finds that entrepreneurs' shock concerning an employees' job. This theory goes on to suggest motivation to exit increases as they perceive more task and goal con- that following shocks, individuals take one of several different psycho- flict with their angel investors. Also, the serial entrepreneurship litera- logical paths as they consider whether to stay or go. In this way, it may ture indicates that some entrepreneurs voluntarily exit firms with the be useful to consider the different types of shocks that may cause intention of pursuing a new opportunity or starting a firm in a new entrepreneurs to consider exiting and then examine how motivation industry (Eggers & Song, 2015; Wright, Robbie, & Ennew, 1997). Per- changes as entrepreneurs grapple with the decision of whether and haps most interesting is the finding that the importance of extrinsic how to exit. motivators like monetary gains may decrease after the first exit among Of particular interest is when exit involves venture termination. serial entrepreneurs (Wright et al., 1997). That said, this decrease in Perhaps venture termination represents a critical event during which extrinsic motivation is counterbalanced by a parallel desire to minimize the extrinsic motivation to minimize losses overrides the intrinsic risk exposure in subsequent ventures. As these streams of literature and prosocial motivations to continue with the venture. Although indicate, motivation plays a key role in driving entrepreneurs toward the venture may fail to exist, the individual (ex‐entrepreneur) goes different types of exit strategies. Therefore, to better understand the on. How do the entrepreneur's motivations influence the decision to relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and founder exit, it terminate the venture, and do these different motivations influence is important to consider different types of motivation and recognize the entrepreneur's reaction to the termination (e.g., the level of grief that venture exit is a multidimensional decision. over business failure; Shepherd, 2003)? Further, what effect does Building on this multidimensional approach to studying venture the entrepreneur's reaction have on termination outcomes, such as exits, scholars have investigated the motivational forces involved in learning from the failure, recovering from the negative emotional, family business decisions of whether to exit via selling versus shutting social, and financial outcomes, and moving on to something new down (Akhter et al., 2016). Interestingly, the primary motivation to sell, (perhaps including a new entrepreneurial endeavor)? Moreover, exit as opposed to shut down, is the identity fit between the family and does not always involve termination; it can include sale or the venture—the greater the alignment between the identity of the merger, for both poorly performing and well‐performing ventures family and the venture, the more likely operations will be shut (e.g., Wennberg et al., 2010). It is important to understand the down instead of sold to an outsider (see also Moen et al., 2016). Moti- different motivations for the different modes of exit and the forma- vations to retire represent one specific avenue of exiting a venture tion of new motivations that are presumably different from those (GERA, 2018), and several different intrinsic motives drive founders' before exit. intentions to retire from their organizations (Chevalier et al., 2018; Chevalier, Fouquereau, Gillet, & Demulier, 2013). Across the literature, we also note the unevenness of the study of motivation as it relates to important external stakeholders such as venture investors. Researchers have paid substantial attention to the motivations of venture capitalists and angels in terms of what drives 5.1 | Entrepreneurial motivation and exit: Directions for future research them to support and mentor entrepreneurs and to invest in their firms (e.g., Drover et al., 2017; Mitteness et al., 2012). However, investors not only play an important role in venture growth, but they can also There needs to be more research on the relationship between motiva- influence the timing and path to exit (e.g., Collewaert, 2012; Drover tion and entrepreneurial exit. We note that although a growing et al., 2017). Despite the potential importance of investor motivation number of studies examine the act of exit (e.g., Bates, 2005; during the exit phase, few studies have explored how the motivation Gimeno et al., 1997; Ucbasaran, Lockett, Wright, & Westhead, of investors during the exit phase influences entrepreneurial motiva- 2003), or the specific path of exit, such as acquisition versus liquida- tion and thus the exit path taken. As such, more granular examination tion, (e.g., Wennberg et al., 2010) the motivations behind these actions is needed to understand how investor motives impact the mechanisms are often inferred rather than measured directly. More can be done to driving entrepreneurial exit motivations, intentions, and behaviors. MURNIEKS 23 ET AL. Although we typically laud entrepreneurial motivation because it targeting certain aspects of motivation has created hotspots and blind fuels persistence to overcome obstacles, the other edge of the sword spots―scholars have focused considerable attention on some areas also cuts; if failure occurs, persistence is likely to increase the eco- and minimal attention on others. In systematically organizing this nomic costs of failure (Shepherd, Wiklund, & Haynie, 2009; e.g., the landscape, we uncover these blind spots, especially as we greater the motivation, the increased likelihood of escalating commit- consider how multiple complex motives operate simultaneously ment to a losing course of action; Staw, 1981). More can be done to (Gagne & Deci, 2005) and drive entrepreneurial action. By developing understand the dark side of strong entrepreneurial motivation and a comprehensive framework of entrepreneurial motives, we incorpo- the ways these negative consequences can be minimized or avoided rate fresh theoretical developments, such as prosocial motivation altogether, such as by studying the self‐regulatory mechanisms that and entrepreneurial passion, into the broader discussion of entrepre- entrepreneurs may develop to benefit from strong motivation without neurial motivation. suffering its negative consequences. Second, we explicitly connect three large yet currently discon- Finally, although there have been calls for entrepreneurs to devise nected bodies of work in the study of entrepreneurial motivation. As exit strategies at the time of founding (Wasserman, 2003), a deeper mentioned earlier, extant literature has evolved predominantly in silos understanding of how motivations change and how these changes based on venture phases aligned with starting, growing, and exiting impact exit strategies is needed. In particular, the findings from the organizations. These streams have advanced our understanding of serial entrepreneurship literature demonstrate path dependencies why some individuals jump into (or out of) new ventures and what between exits and subsequent foundings (Carter & Ram, 2003; Hsu, sustains them when they do. However, individuals' motives for initiat- Shinnar, Powell, & Coffey, 2017; Westhead & Wright, 1998; Wright ing a new organization likely affect their motivation to sustain it, which et al., 1997). The change in levels of extrinsic and intrinsic motives may, in turn, influence their motivation to exit the venture and launch indicate a serial entrepreneur's level of motivation may depend on another one (e.g., Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014; Westhead et al., the success or failure of previous venture exits, which attests to the 2005). To date, scholars have largely ignored such path dependencies. importance of considering past history when evaluating present moti- Moreover, as their ventures progress through the entrepreneurial vation. Also, as some exit modes become more likely (and others less process, entrepreneurs' motives may change as well. Research has likely), do motivations change to reflect the new reality? Future been quick to acknowledge the impact of differences between individ- research needs to explore how entrepreneurs' motives impact the for- uals in their motives (i.e., inter‐individual) but has been slower to con- mulation, assessment, and exploitation of exit strategies as well as sider how entrepreneurial motives and actions might change over time how entrepreneurs' exit strategies influence their subsequent entre- (i.e., intra‐individual). Moreover, whereas scholars have made method- preneurial motivations. An obvious point of distinction is between vol- ological progress by considering the passage of time (e.g., lagged untary and involuntary exit, each of which has different implications regressions), theoretical aspects of temporal change in motivation for entrepreneurial motivation. have been largely absent. This lack of attention is noteworthy because calls in the OB literature urge scholars to move beyond static examinations of motivation (Steel & Konig, 2006) to better understand what 6 | DISCUSSION individual and contextual forces might cause motives to wax and wane over time (Grant & Shin, 2012). In our review, we offer opportunities In this review, we map the landscape of research on motivation within to extend the study of individual differences into temporal domains and across each of the three phases of the entrepreneurial process— for both inter‐individual and intra‐individual entrepreneurial motives initiation, growth, and exit. In doing so, we outline the nomological net- and actions. work of motivation constructs as well as highlight the prevalence of research in certain categories (e.g., economic and venture initiation motivations) and the relative dearth of coverage in others (e.g., interactions between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and motives underly- 6.1 | Future directions for entrepreneurial motivation research ing new venture exit). We also assess aspects of entrepreneurial motivation research that could be useful in a better understanding of Motivation involves the study of drivers that produce direction, inten- employee, leader, and team motivation. More broadly, the conclusions sity, and duration of behavior (Mitchell & Daniels, 2003; Pinder, 1998). drawn from our review provide insights to advance the study of moti- As this review shows, the direction of entrepreneurial motivation has vation in the entrepreneurial and OB literatures. received significant scholarly attention. For example, motivation for First, organizing the entrepreneurial motivation literature provides sustaining natural environments directs behaviors toward sustainable a bridge between the advances in our understanding of this phenom- development opportunities (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011), motivation enon made by past research and the ways future research can extend for improving work–family balance directs behaviors toward more our knowledge of what drives entrepreneurs as they start, grow, and family‐friendly cultures at work (Adkins et al., 2013), and motivation exit their organizations. As our review shows, researchers have for business growth directs behaviors toward growing ventures produced valuable insights into why individuals take specific entrepre- (Delmar & Wiklund, 2008). Decidedly less research examines how neurial actions at specific points in time. However, repeatedly motives affect the intensity and duration of founder behavior during 24 MURNIEKS ET AL. the new venture process. Further, although the intensity of behaviors research increases our understanding of the role of the individual in underpinned by motives has been captured to some degree by Likert driving entrepreneurial action, there are opportunities to study entre- scales measuring the frequency or presence of the assessed behavior, preneurial differences beyond demographic variables and personality there is an opportunity to more explicitly understand the conditions constructs. Specifically, research on the biological or physiological fac- under which entrepreneurial motivation leads to low, appropriate, or tors that augment or dampen entrepreneurial motivation is largely “too much” (Pierce & Aguinis, 2011) intensity for a given entrepre- absent. This is a noteworthy oversight as sleep (Murnieks et al., neurial action. Regarding duration, although some research focuses in press; Barnes, 2012; Barnes, Miller, & Bostock, 2017; Gunia, on the persistence of start‐up efforts (e.g., Cardon et al., 2009), other 2018), testosterone (Nicolaou, Patel, & Wolfe, 2018), and cortisol outcomes related to the duration of entrepreneurial behavior are rela- levels (Liu‐Qin, Bauer, Johnson, Groer, & Salomon, 2014; Sherman, tively neglected. This dearth of research may be partly due to the dif- Lemer, Josephs, Renshon, & Gross, 2016) represent factors that may ficulty inherent in gathering episodic and longitudinal field data from a explain meaningful variance in entrepreneurial motivation and draw sample of entrepreneurs. From an analytical perspective, scholars are increasing interest in the OB literature but are understudied in entre- making progress by employing lagged designs in which they tempo- preneurship. More theory and measurement of these individual vari- rally separate motivation assessments from entrepreneurial behaviors ables could expand our understanding of the role of physiology in (e.g., Baron et al., 2016; Delmar & Wiklund, 2008; Renko, 2013). entrepreneurial motivation and also contribute to the OB literature. Nonetheless, there are greater opportunities to use experiential Research in the OB literature argues that motivation at the team sampling designs or other longitudinal methods to determine the level has important consequences for team members and team out- duration‐based comes (Park, Spitzmuller, & DeShon, 2013). As such, the study of boundaries of entrepreneurial motives (Short, Ketchen, Combs, & Ireland, 2010). new venture team motivation represents an opportunity to extend We also encourage scholars to design and conduct rigorous inves- our knowledge of motivation's role in the entrepreneurial process. tigations of the antecedents and effects of entrepreneurial motivation. Investigating the nature, causes, and consequences of team motiva- Most empirical studies reviewed in this paper use survey question- tion in extreme entrepreneurial environments may provide OB naires or secondary data collections wherein motives were inferred researchers with new insights into group processes. In other words, rather than assessed directly. These methods can be subject to the entrepreneurial context represents a fascinating arena to explore response biases and retrospective concerns (Chandler & Lyon, 2001). how individual‐level motivations combine and interact in teams as We suggest researchers use a wider array of study designs, including well as how collective motivations may arise at the team level to experiments and qualitative approaches, to more accurately gauge drive behaviors. causal mechanisms and to distinguish shorter‐term cognitive, behav- Finally, researchers have rarely used meta‐analytic approaches to ioral, and affective outcomes from motivations. In addition, feedback assess the strength of relationships between the antecedents, media- mechanisms may exist between entrepreneurs' motives and their tors, moderators, and outcomes of entrepreneurial motivation (see behavior. That is, entrepreneurs' motivation shapes their subsequent Figures 1–4; for an exception see meta‐analyses on the role of actions, the results of which may then alter their motives. Experimen- achievement motivation in the entrepreneurial process [e.g., Collins, tal manipulations could help tease apart these spirals and loops to Hanges, & Locke, 2004, Stewart & Roth, 2007]). Throughout this inform our theorizing about the iterative nature of these relationships. review, we note the many different motives cataloged as stimulants As ventures grow, they adapt to stakeholders encountered along for entrepreneurial behavior (e.g., economic, prosocial, intrinsic, pas- the way (e.g., investors, employees, and customers); therefore, there sion, and fear‐of‐failure). Given that some of these operate simulta- is an opportunity to clarify how relevant others' motives affect neously, meta‐analytic approaches could determine how much entrepreneurs' motivation over time. Importantly, the motives of variation is attributable to each of these different sources. Studies of stakeholders who support a venture's inception are not necessarily entrepreneurship motivation typically focus on individual motives the same as those who support its growth or exit (e.g., Fassin & without controlling for other types of motivation. Timely meta‐ Drover, 2017). Just as entrepreneurial motives are not static, neither analyses in this area will help entrepreneurship researchers put their are those of the stakeholders surrounding the venture. As such, more findings in context, thereby facilitating the advancement of this line dynamic theorizing should consider entrepreneurial and stakeholder of research as a coherent whole. motives. As indicated by studies investigating the moderators of the relationships in different venture phases (e.g., Akhter et al., 2016; George et al., 2016; Gregoire & Shepherd, 2012; Khan et al., 2014), 7 | CO NC LUSIO N the effects of motivation differ depending on context. This perspective can be applied in future research to clarify how path dependen- In this review, we summarize and integrate the wide body of research cies or key stakeholder concerns might impact motives both as surrounding entrepreneurial motivation. In doing so, we develop a antecedents as well as moderators. roadmap that both outlines the extant literature and highlights Entrepreneurship researchers have examined how individual char- opportunities for future research. Motivation is a cornerstone of the acteristics affect entrepreneurial motivation (e.g., Baron et al., 2016; entrepreneurial process. Our review reinforces the conclusion that Brockner et al., 2004; Miller & Le Breton‐Miller, 2017). Although this entrepreneurial motivation drives essential behaviors related to MURNIEKS 25 ET AL. venture initiation, growth, and exit. Although the forceful nature of motivation is unquestionable, the understanding of its pathways of operation still requires further elaboration by scholars. In particular, our review displays the drastically uneven coverage given to different aspects of motivation throughout the entrepreneurial process and the relative lack of integration of different types of motives that jointly propel behavior. We hope this review makes the somewhat fragmented research on entrepreneurial motivation more accessible and facilitates future contributions to our understanding of what drives the entrepreneurial process. ORCID Anthony C. Klotz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7365-9744 RE FE R ENC E S Adkins, C. L., Samaras, S. A., Gilfillan, S. W., & McWee, W. E. (2013). The relationship between owner characteristics, company size, and the work–family culture and policies of women‐owned businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 51, 196–214. Akhter, N., Sieger, P., & Chirico, F. (2016). If we can't have it, then no one should: Shutting down versus selling in family business portfolios. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10, 371–394. Benzing, C., Chu, H. M., & Kara, O. (2009). Entrepreneurs in Turkey: A factor analysis of motivations, success factors, and problems. Journal of Small Business Management, 47, 58–91. Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez‐Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 25, 258–279. Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez‐Mejia, L. R., & Larraza‐Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family‐controlled firms pollute less? Administrative Science Quarterly, 55, 82–113. Block, J., Sandner, P., & Spiegel, F. (2015). How do risk attitudes differ within the group of entrepreneurs? The role of motivation and procedural utility. Journal of Small Business Management, 53, 183–206. Bolino, M. C., & Grant, A. M. (2016). The bright side of being prosocial at work, and the dark side too: A review and agenda for research on other‐oriented motives, behavior, and impact in organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 10, 599–670. Breugst, N., Domurath, A., Patzelt, H., & Klaukien, A. (2012). Perceptions of entrepreneurial passion and employees' commitment to entrepreneurial ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 36, 171–192. Brockner, J., Higgins, E. T., & Low, M. B. (2004). Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 203–220. Almandoz, J. (2012). Arriving at the starting line: The impact of community and financial logics on new banking ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1381–1406. Burmeister‐Lamp, K., Levesque, M., & Schade, C. (2012). Are entrepreneurs influenced by risk attitude, regulatory focus or both? An experiment on entrepreneurs' time allocation. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 456–476. Almandoz, J. (2014). Founding teams as carriers of competing logics: When institutional forces predict banks' risk exposure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59, 442–473. Cacciotti, G., Hayton, J. C., Mitchell, J. R., & Giazitzoglu, A. (2016). A reconceptualization of fear of failure in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 302–325. Amit, R., MacCrimmon, K. R., Zietsma, C., & Oesch, J. M. (2000). Does money matter? Wealth attainment as the motive for initiating growth‐oriented technology ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 119–143. Cantillon, R. 1931). In H. Higgs (Ed.), trans(1755), Essai Sur la Nature du Commerce en General. London: Macmillan. Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24, 233–247. Barnes, C. M. (2012). Working in our sleep: Sleep and self‐regulation in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review, 2, 234–257. Barnes, C. M., Miller, J. A., & Bostock, S. (2017). Helping employees sleep well: Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 104–113. Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 275–294. Cardon, M. S., Gregoire, D. A., Stevens, C. E., & Patel, P. C. (2013). Measuring entrepreneurial passion: Conceptual foundations and scale validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 373–396. Cardon, M. S., & Kirk, C. P. (2015). Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self‐efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39, 1027–1050. Cardon, M. S., Post, C., & Forster, W. R. (2017). Team entrepreneurial passion: Its emergence and influence in new venture teams. Academy of Management Review, 42, 283–305. Cardon, M. S., Wincent, J., Singh, J., & Drnovsek, M. (2009). The nature and experience of entrepreneurial passion. Academy of Management Review, 34, 511–532. Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33, 328–340. Carsrud, A. L., & Brannback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49, 9–26. Baron, R. A., Mueller, B. A., & Wolfe, M. T. (2016). Self‐efficacy and entrepreneurs' adoption of unattainable goals: The restraining effects of self‐control. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 55–71. Carter, S., & Ram, M. (2003). Reassessing portfolio entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 21, 371–380. Bates, T. (2005). Analysis of young, small firms that have closed: Delineating successful from unsuccessful closures. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 343–358. Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 587–598. Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 292–303. Casson, M. (1982). The entrepreneur: An economic theory. Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble Books. Cennamo, C., Berrone, P., Cruz, C., & Gomez‐Mejia, L. R. (2012). Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family‐controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36, 1153–1173. Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40‐year meta‐ analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 980–1008. 26 Chandler, G. N., & Lyon, D. W. (2001). Issue of research design and construct measurement in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 25, 101–113. Chen, X. P., Yao, X., & Kotha, S. (2009). Entrepreneur passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: A persuasion analysis of venture capitalists' funding decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 199–214. Chevalier, S., Fouquereau, E., Gillet, N., & Bosselut, G. (2018). Unraveling the perceived reasons underlying entrepreneurs' retirement decisions: A person‐centered perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 56, 513–528. Chevalier, S., Fouquereau, E., Gillet, N., & Demulier, V. (2013). Development of the reasons for entrepreneurs' retirement decision inventory (RERDI) and preliminary evidence of its psychometric properties in a French sample. Journal of Career Assessment, 21, 572–586. MURNIEKS ET AL. angel investment, crowdfunding, and accelerators. Journal of Management, 43, 1820–1853. Dunkelberg, W., Moore, C., Scott, J., & Stull, W. (2013). Do entrepreneurial goals matter? Resource allocation in new owner‐managed firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 225–240. Edelman, L. F., Brush, C. G., Manolova, T. S., & Greene, P. G. (2010). Start‐ up motivations and growth intentions of minority nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 48, 174–196. Eggers, J. P., & Song, L. (2015). Dealing with failure: Serial entrepreneurs and the costs of changing industries between ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1785–1803. Farmer, S. M., Yao, X., & Kung‐Mcintyre, K. (2011). The behavioral impact of entrepreneur identity aspiration and prior entrepreneurial experience. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 35, 245–273. Chouinard, Y. (2005). Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman. New York: The Penguin Press. Fassin, Y., & Drover, W. (2017). Ethics in entrepreneurial finance: Exploring problems in venture partner entry and exit. Journal of Business Ethics, 140, 649–672. Collewaert, V. (2012). Angel investors' and entrepreneurs' intentions to exit their ventures: A conflict perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 36, 753–779. Fauchart, E., & Gruber, M. (2011). Darwinians, communitarians and missionaries: The role of founder identity in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 935–957. Collins, C. J., Hanges, P. J., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta‐analysis. Human Performance, 17, 95–117. Fisher, G., Kotha, S., & Lahiri, A. (2016). Changing with the times: An integrated view of identity, legitimacy and new venture life cycles. Academy of Management Review, 41, 383–409. Cruz, C., & Justo, R. (2017). Portfolio entrepreneurship as a mixed gamble: A winning bet for family entrepreneurs in SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 55, 571–593. Gagne, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self‐determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362. Davis, B. C., Hmieleski, K. M., Webb, J. W., & Coombs, J. E. (2017). Funders' positive affective reactions to entrepreneurs' crowdfunding pitches: The influence of perceived product creativity and entrepreneurial passion. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 90–106. George, G., Kotha, R., Parikh, P., Alnuaimi, T., & Bahaj, A. S. (2016). Social structure, reasonable gain, and entrepreneurship in Africa. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 1118–1131. George, J. M. (2007). Creativity in organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 1, 439–477. Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta‐analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668. GERA (Global Entrepreneurship Research Association) (2018). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Global Report for 2017‐18 Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2008). The effect of small business managers' growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 32, 437–457. Gielnik, M. M., Spitzmuller, M., Schmitt, A., Klemann, D. K., & Frese, M. (2015). “I put in effort, therefore I am passionate”: Investigating the path from effort to passion in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1012–1031. DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2003). Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: Exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 815–832. DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 203–215. DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38, 351–374. DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Chandler, G. N. (2015). Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: A typology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 255–272. DeTienne, D. R., Shepherd, D. A., & De Castro, J. O. (2008). The fallacy of “only the strong survive”: The effects of extrinsic motivation on the persistence decisions for under‐performing firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 23, 528–546. Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2000). Entrepreneurship as a utility maximizing response. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 231–251. Drnovsek, M., Cardon, M. S., & Patel, P. C. (2016). Direct and indirect effects of passion on growing technology ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10, 194–213. Drover, W., Busenitz, L., Matusik, S., Townsend, D., Anglin, A., & Dushnitsky, G. (2017). A review and road map of entrepreneurial equity financing research: Venture capital, corporate venture capital, Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783. Gomez‐Mejia, L. R., Cruz, C., Berrone, P., & DeCastro, J. (2011). The bind that ties. Academy of Management Annals, 5, 653–707. Gomez‐Mejia, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Nunez‐Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano‐Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family‐controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52, 106–137. Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 48–58. Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 73–96. Grant, A. M., & Shin, J. (2012). Work motivation: Directing, energizing, and maintaining effort (and research). In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 505–519). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gregoire, D. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2012). Technology‐market combinations and the identification of entrepreneurial opportunities: An investigation of the opportunity‐individual nexus. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 753–785. MURNIEKS ET AL. 27 Grunhagen, M., & Mittelstaedt, R. A. (2005). Entrepreneurs or investors: Do multi‐unit franchisees have different philosophical orientations? Journal of Small Business Management, 45, 207–225. Kuhn, K. M., & Galloway, T. L. (2015). With a little help from my competitors: Peer networking among artisan entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39, 571–600. Gunia, B. C. (2018). The sleep trap: Do sleep problems prompt entrepreneurial motives but undermine entrepreneurial means? Academy of Management Perspectives, 32, 228–242. Langowitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 31, 341–364. Hallen, B. L., & Pahnke, E. C. (2016). When do entrepreneurs accurately evaluate venture capital firms' track records? A bounded rationality perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1535–1560. Haynie, J. M., & Shepherd, D. (2011). Toward a theory of discontinuous career transition: Investigating career transitions necessitated by traumatic life events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 501–524. Hebert, R. F., & Link, A. N. (1988). The Entrepreneur: Mainstream Views and Radical Critiques (2nd ed.). New York: Praeger. Lee, T. W., & Mitchell, T. R. (1994). An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Academy of Management Review, 19, 51–89. Li, Y. (2011). Emotions and new venture judgment in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28, 277–298. Li, J., Chen, X. P., Kotha, S., & Fisher, G. (2017). Catching fire and spreading it: A glimpse into displayed entrepreneurial passion in crowdfunding campaigns. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 1075–1090. Herron, L., & Sapienza, H. J. (1992). The entrepreneur and the initiation of new venture launch activities. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 17, 49–55. Liu‐Qin, Y., Bauer, J., Johnson, R. E., Groer, M. W., & Salomon, K. (2014). Physiological mechanisms that underlie the effects of interactional unfairness on deviant behavior: The role of cortisol activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 310–321. Hodgkinson, G. P., & Ford, J. K. (2014). Narrative, meta‐analytic, and systematic reviews: What are the differences and why do they matter. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, S1–S5. McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31, 132–152. Hsu, D. K., Haynie, J. M., Simmons, S. A., & McKelvie, A. (2014). What matters, matters differently: A conjoint analysis of the decision policies of angel and venture capital investors. Venture Capital, 16, 1–25. McMullen, J. S., & Warnick, B. J. (2015). To nurture or groom? The parent‐ founder succession dilemma. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39, 1379–1412. Hsu, D. K., Shinnar, R. S., Powell, B. C., & Coffey, B. S. (2017). Intentions to reenter venture creation: The effect of entrepreneurial experience and organizational climate. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35, 928–948. Miller, D., & Le Breton‐Miller, I. (2014). Deconstructing socioemotional wealth. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 38, 713–720. Huyghe, A., Knockaert, M., & Obschonka, M. (2016). Unraveling the “passion orchestra” in academia. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 344–364. Miller, D., & Le Breton‐Miller, I. (2017). Underdog entrepreneurs: A model of challenge‐based entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 41, 7–17. Janney, J. J., & Dess, G. G. (2006). The risk concept for entrepreneurs reconsidered: New challenges to the conventional wisdom. Journal of Business Venturing, 21, 385–400. Miller, T. L., Grimes, M. G., McMullen, J. S., & Vogus, T. J. (2012). Venturing for others with heart and head: How compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 37, 616–640. Jaskiewicz, P., Combs, J. G., & Rau, S. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 29–49. Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else's shoes: The role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 2(3), 223–238. Jiang, D. S., Kellermanns, F. W., Munyon, T. P., & Morris, M. L. (2018). More than meets the eye: A review and future directions for the social psychology of socioemotional wealth. Family Business Review, 31, 125–157. Mitchell, T. R., & Daniels, D. (2003). Motivation. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology, volume twelve: Industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 225–254). New York: John Wiley. Kanfer, R., Frese, M., & Johnson, R. E. (2017). Motivation related to work: A century of progress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 338–355. Mitteness, C., Sudek, R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Angel investor characteristics that determine whether perceived passion leads to higher evaluations of funding potential. Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 592–606. Kang, J. H., Matusik, J. G., Kim, T. Y., & Phillips, J. M. (2016). Interactive effects of multiple organizational climates on employee innovative behavior in entrepreneurial firms: A cross‐level investigation. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 628–642. Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (1993). The dynamics of family controlled firms: The good and the bad news. Organizational Dynamics, 21, 59–71. Khan, S. A., Tang, J., & Joshi, K. (2014). Disengagement of nascent entrepreneurs from the start‐up process. Journal of Small Business Management, 52, 39–58. Klotz, A. C., Hmieleski, K. M., Bradley, B. H., & Busenitz, L. W. (2014). New venture teams: A review of the literature and roadmap for future research. Journal of Management, 40, 226–255. Knight, F. H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. Washington, DC: Beard Books. Kollmann, T., Stockmann, C., & Kensbock, J. M. (2017). Fear of failure as a mediator of the relationship between obstacles and nascent entrepreneurial activity—An experimental approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 280–301. Moen, O., Heggeseth, A. G., & Lome, O. (2016). The positive effect of motivation and international orientation on SME growth. Journal of Small Business Management, 54, 659–678. Morgan, J., & Sisak, D. (2016). Aspiring to succeed: A model of entrepreneurship and fear of failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 1–21. Morris, M. H., Miyasaki, N. N., Watters, C. E., & Coombes, S. M. (2006). The dilemma of growth: Understanding venture size choices of women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 44, 221–244. Mowrer, O. H. (1952). Motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 3, 419–438. Mueller, B. A., Wolfe, M. T., & Syed, I. (2017). Passion and grit: An exploration of the pathways leading to venture success. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 260–279. Murnieks, C. Y., Arthurs, J. D., Cardon, M. S., Farah, N., Stornelli, J., & Haynie, J. M. (in press) Close your eyes or open your mind: Effects of 28 MURNIEKS sleep and mindfulness exercises on entrepreneurs' exhaustion. Journal of Business Venturing.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.12.004 Murnieks, C. Y., Cardon, M. S., Sudek, R., White, T. D., & Brooks, W. T. (2016). Drawn to the fire: The role of passion, tenacity, and inspirational leadership in angel investing. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 468–484. Murnieks, C. Y., Mosakowski, E. M., & Cardon, M. S. (2014). Pathways of passion: Identity centrality, passion, and behavior among entrepreneurs. Journal of Management, 40, 1583–1606. Murphy, C., Klotz, A. C., & Kreiner, G. E. (2017). Blue skies and black boxes: The promise (and practice) of grounded theory in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Review, 27, 291–305. Naffziger, D. W., Hornsby, J. S., & Kuratko, D. F. (1994). A proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 18, 29–42. Nicolaou, N., Patel, P. C., & Wolfe, M. T. (2018). Testosterone and tendency to engage in self‐employment. Management Science, 64, 1825–1841. Park, G., Spitzmuller, M., & DeShon, R. P. (2013). Advancing our understanding of team motivation: Integrating conceptual approaches and content areas. Journal of Management, 39, 1339–1379. Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 35, 631–652. Pierce, J. R., & Aguinis, H. (2011). The too‐much‐of‐a‐good‐thing effect in management. Journal of Management, 39, 313–338. Pinder, C. C. (1998). Work motivation in organizational behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Ployhart, R. E. (2008). Work motivation methods, measures, and assessment strategies. In R. Kanfer, G. Chen, & R. Pritchard (Eds.), Work Motivation: Past, Present, and Future (pp. 17–61). New York, NY: Routledge. Powell, E. E., & Baker, T. (2014). It's what you make of it: Founder identity and enacting strategic responses to adversity. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 1406–1433. Renko, M. (2013). Early challenges of nascent social entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 37, 1045–1069. Rich, L. (2003). The Accidental Zillionaire: Demystifying Paul Allen. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13, 257–279. ET AL. Sherman, G. D., Lemer, J. S., Josephs, R. A., Renshon, J., & Gross, J. J. (2016). The interaction of testosterone and cortisol is associated with attained status in male executives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 921–929. Shipp, A. J., & Cole, M. S. (2015). Time in individual‐level organizational studies: What is it, how is it used, and why isn't it exploited more often? Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 237–260. Short, J. C., Ketchen, D. J., Combs, J. G., & Ireland, R. D. (2010). Research methods in entrepreneurship: Opportunities and challenges. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 6–15. Spivack, A. J., McKelvie, A., & Haynie, J. M. (2014). Habitual entrepreneurs: Possible cases of entrepreneurial addiction? Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 651–667. Staw, B. M. (1981). The escalation of commitment to a course of action. Academy of Management Review, 6, 577–587. Steel, P., & Konig, C. J. (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31, 889–913. Stenholm, P., & Renko, M. (2016). Passionate bricoleurs and new venture survival. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 595–611. Stewart, W. H., & Roth, P. L. (2007). A meta‐analysis of achievement motivation differences between entrepreneurs and managers. Journal of Small Business Management, 45, 401–421. Townsend, D. M., & Hart, T. A. (2008). Perceived institutional ambiguity and the choice of organizational form in social entrepreneurial ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 32, 685–700. Ucbasaran, D., Lockett, A., Wright, M., & Westhead, P. (2003). Entrepreneurial founder teams: Factors associated with member entry and exit. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 28, 107–127. Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Flores, M. (2010). The nature of entrepreneurial experience, business failure, and comparative optimism. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 541–555. Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2015). From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: Self‐control and action‐related doubt, fear and aversion. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 655–673. Vik, J., & McElwee, G. (2011). Diversification and the entrepreneurial motivations of farmers in Norway. Journal of Small Business Management, 49, 390–410. Warnick, B. J., Murnieks, C. Y., McMullen, J. S., & Brooks, W. T. (2018). Passion for entrepreneurship or passion for the product: A conjoint analysis of angel and VC decision‐making. Journal of Business Venturing, 33, 315–332. Wasserman, N. (2003). Founder‐CEO succession and the paradox of entrepreneurial success. Organization Science, 14, 149–172. Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–226. Webb, J. W., Bruton, G. D., Tihanyi, L., & Ireland, R. D. (2013). Research on entrepreneurship in the informal economy: Framing a research agenda. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 598–614. Shepherd, D. A. (2003). Learning from business failure: Propositions of grief recovery for the self‐employed. Academy of Management Review, 28, 318–328. Weber, K., Heinze, K. L., & DeSoucey, M. (2008). Forage for thought: Mobilizing codes in the movement for grass‐fed meat and dairy products. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53, 529–567. Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Party on! A call for entrepreneurship research that is more interactive, activity‐based, cognitively hot, compassionate, and prosocial. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 489–507. Wennberg, K., & DeTienne, D. R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 4–16. Shepherd, D. A., Wiklund, J., & Haynie, J. M. (2009). Moving forward: Balancing the financial and emotional costs of business failure. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 134–148. Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2010). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: Divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 361–375. Shepherd, D. A., Williams, T. A., & Patzelt, H. (2015). Thinking about entrepreneurial decision making: Review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 41, 11–46. Westhead, P., Ucbasaran, D., Wright, M., & Binks, M. (2005). Novice, serial, and portfolio entrepreneur behavior and contributions. Small Business Economics, 25, 109–132. MURNIEKS 29 ET AL. Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (1998). Novice, portfolio, and serial founders: Are they different? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 173–204. Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Aspiring for, and achieving growth: The moderating role of resources and opportunities. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1919–1941. Williams, T. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2016). Building resilience or providing sustenance: Different paths of emergent ventures in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 2069–2102. Witt, U. (2007). Firms as realizations of entrepreneurial visions. Journal of Management Studies, 44, 1125–1140. Woo, C. Y., Cooper, A. C., & Dunkelberg, W. C. (1991). The development and interpretation of entrepreneurial typologies. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 93–114. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES Charles Y. Murnieks is an Assistant Professor in the College of Business at Oregon State University. He received his PhD from the University of Colorado, Boulder. His research interests include entrepreneurial passion, motivation, and venture investor decision‐making. Anthony C. Klotz is an Associate Professor in the College of Business at Oregon State University. He received his PhD from the University of Oklahoma's Price College of Business. His research interests include organizational citizenship behavior, moral licensing, team conflict, and employee resignation. Wood, M. S., McKelvie, A., & Haynie, J. M. (2014). Making it personal: Opportunity individuation and the shaping of opportunity beliefs. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 252–272. Dean Shepherd is the Ray and Milann Siegfried Professor of Wright, M., Robbie, K., & Ennew, C. (1997). Serial entrepreneurs. British Journal of Management, 8, 251–268. Dame University. He investigates decision‐making involved in Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Deeds, D. L. (2015). Rising from the ashes: Cognitive determinants of venture growth after entrepreneurial failure. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 39, 209–236. Yitshaki, R., & Kropp, F. (2016). Entrepreneurial passions and identities in different contexts: A comparison between high‐tech and social entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 28, 206–233. York, J. G., O'Neil, I., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2016). Exploring environmental entrepreneurship: Identity coupling, venture goals, and stakeholder incentives. Journal of Management Studies, 53, 695–737. Entrepreneurship at the Mendoza College of Business, Notre leveraging cognitive and other resources to act on opportunities and the processes of learning from experimentation in ways that lead to high levels of performance. How to cite this article: Murnieks CY, Klotz AC, Shepherd DA. Entrepreneurial motivation: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. J Organ Behav. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2374