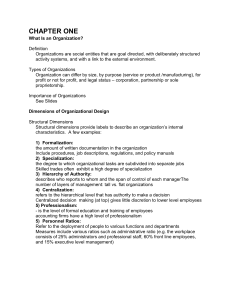

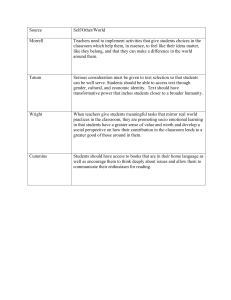

Human Relations DOI: 10.1177/0018726706065371 Volume 59(4): 483–504 Copyright © 2006 The Tavistock Institute ® SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi www.sagepublications.com A model of political leadership Kevin Morrell and Jean Hartley A B S T R AC T In this article we develop a model of political leadership. In doing so, we analyse the challenges facing political leaders in local government in England and Wales. We use this analysis as a basis for broader theorizing: about leadership at other levels of government, and in other countries. The scope for applying extant accounts of leadership in these domains can be enhanced by considering the relational complexities that characterize the environment within which political leaders act; by doing so we offer an agenda for research. We describe the context for political leaders in terms of figurational sociology, where figurations denote interdependent networks of social relations. These take shape in different arenas of action, and are partly influenced by the different roles that political leaders undertake. These figurations are also constituted differently given the diversity inherent in the context for enacting political leadership. We propose a conceptual model that serves both as a heuristic framework to organize conceptualization of this understudied area, and to orient future research. K E Y WO R D S figuration government leadership model political Introduction Although there is a large literature on leadership, much of this is acontextual, framed in terms of the individual, and atomistic. In Fairhurst’s terms (2001: 383), the ‘dominant views of leadership have been shaped by a traditional psychological view of the world where, in a figure-ground 483 484 Human Relations 59(4) arrangement, the individual is figure, the system is background’. This dualism precludes systemic perspectives (Senge, 1990), and accounts that acknowledge the interplay between structural and agentic explanations of social phenomena (Giddens, 1984). As well as potentially oversimplifying associated phenomena, such as charisma, or effectiveness, the ‘traditional psychological view’ privileges research from nomothetic paradigms, at the expense of interpretivist perspectives such as ethnography and social constructionism. This can bias research towards causal and functionalist accounts, at the expense of more detailed exploration of meaning, and intentionality (Ghoshal, 2005). It is important to address these limitations, since the way in which social phenomena are labelled and explained influences them through the Pygmalion effect (Ferraro et al., 2005). Here we offer an account to complement rather than usurp established accounts of leadership. Our approach has broad implications although the aim is to develop research in an understudied area, by focusing on political leaders: those who hold formal political authority, acquired through election in a democratic society. In the organizational behaviour literature, empirical research has operationalized ‘political skill’ as a discrete subset of behaviours that can enhance effectiveness, or explain career success (Moss, 2005). ‘Political power’ has been used narrowly to refer to the ways in which decisions are controlled, and resources are deployed and distributed in organizations (Yukl, 1989). In everyday discourse, ‘politics’ is both a signifier and explanation for a range of unfavourable workplace outcomes; ‘politicking’ describes occasionally unsavoury activities such as lobbying or ‘dirty tricks’. In both senses, these pejorative connotations of politics can colour perceptions, and muddy analysis of political leadership. We argue here that political leadership is a substantive area of activity that is understudied in the contemporary leadership literature, and as such it warrants attention. Political leadership Here we define political leaders as: i) democratically elected ii) representatives who iii) are vulnerable to deselection, and iv) operate within, as well as influence a constitutional and legal framework. Their source of authority is v) a mandate: ‘permission to govern according to declared policies, regarded as officially granted by an electorate . . . upon the decisive outcome of an election’ (Chambers dictionary, 1993). Membership of the electorate is vi) set out in law, and broader than organizational or union forms of membership, since it extends to all citizens with voting rights, in a defined constituency. This summarizes the basis for political leaders’ claims to authority. It illustrates how they differ from other leaders such as: chief executives, Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership managers from the private, public and voluntary sectors and those in the military. The definition is brief and contains a number of terms that could warrant further discussion, or are understood relationally (electorate, citizen, constituency) but we propose the above criteria as necessary conditions that are broad enough to include many different types of political leaders. It covers what we call ‘formal’ political leaders, though not ‘informal’ political leaders, such as those who head special interest groups, or civil rights activists, or trade unionists (Azzam & Riggio, 2003). Nor does it cover despots (Kets de Vries, 2005). Since political leaders are elected rather than appointed, and act as representatives, they require consent from those whom they govern and serve. They have a duty to serve all their constituents and protect the interests of future generations, rather than simply those who supported them. This should include the elderly and disadvantaged groups, as well as those who do not have the power to vote, such as children. These are typical differences in comparison with non-political leaders, but political leaders also operate under different structures of accountability and scrutiny. In addition, they have formal legal responsibility for a broad range of issues: health, law enforcement, taxation, education, legislation and the economic sphere. The networks within which they act have regularities but are also fluid. Political leaders gain authority through the ballot box initially but their authority is potentially subject to challenge on a daily basis, from: their political party (most operate within a party structure), opposition politicians, the media, their constituents, and other bodies (e.g. charities, lobby groups, business confederations). One characteristic of the challenges facing political leaders is that actions and decisions may require the mobilization of different groups in order to build consent. In this sense, the issue for politicians is to gain some consensus across the entire domain of a problem (Thompson, 1967). A further source of complexity is that political leaders are directly responsible for the provision of public services (e.g. street lighting), and also have a regulatory and enforcement role (e.g. in collecting taxes). The ubiquitous language of customer relations breaks down here since many ‘customers’ of regulatory services are unwilling ones (Pollitt, 2003). People’s expectations of what leaders can provide may differ widely from what is actually possible given legal, logistical and practical constraints (Boin & Hart, 2003). These different challenges show how the relationship between leaders, stakeholder groups and the electorate is complex and interdependent. There are some areas of overlap and similarity here with non-political leaders, such as senior chief executives (CEs), and leaders in public administration (Cook, 1998). CEs may feel they, and their organization, have a moral duty to their stakeholders, a term that can be interpreted broadly 485 486 Human Relations 59(4) (Kelly et al., 2000). Accordingly, they may believe they should act in the interests of all stakeholders, even those who are opposed to their appointment and strategies. Governance structures within an organization may be democratic in the sense that those in authority are accountable to their superiors, who are in turn accountable to collective, representative bodies (Ackoff, 1994). These arrangements could be extended to include other stakeholders, bringing the model of a democratic corporation closer to the literal sense of democracy, rule by the people (Skelcher & Mathur, 2004). CEs may seek to influence policy, to mobilize coalitions and consolidate support, for instance prior to a shareholders’ meeting. Writers such as Charles Handy have argued that the boundaries between public and private sector organizations are blurring, an issue that has been explored in greater depth with reference to the public sector generally (Robbins, 1993), and local government in particular (Benington, 2000). Hartley (2000) argues that politically led organizations can provide useful insights into generic processes in organizational behaviour. Similarly, Brunsson (1985: 116) suggests political organizations, ‘expose fundamental problems connected with rationality and action and can teach us a great deal about fundamental problems and solutions in organizations’. Despite areas of overlap and similarity, we submit that the definition above describes a particular kind of activity, one broad enough to reference a large number of leaders for whom leadership is sufficiently coherent and distinctive as to be considered a phenomenon in its own right. The definition orients research away from an exclusive focus on behaviours because it considers the formal basis for authority, and the context within which leadership is enacted. We do not question that the same behaviours may manifest themselves in political and non-political leaders, however, given the particular structures within which political leaders operate, attention to context is also important (Hoggett, 2006; Leach et al., 2005). Though leaders from other sectors face complex challenges, they do not have a similar mandate, and this is not addressed in the contemporary literature. Here we address this gap by offering a model for political leadership that is sensitive to structural constraints, embedded in the context, and constituted in social interaction (Collinson, 2005). Prior to exploring the suitability of existing theories of leadership, we outline the particular contextual complexities facing political leaders. Political leadership in situ In this section, we propose and discuss a summative framework for political leadership. This is developed from consideration of a particular context: local government in the UK. To maintain clarity, subsequent exposition draws on Rolea Executive Scrutiny Advocacy a b KSAs valuesb Key decision-makers, heart of political body Delegation, information processing, persuading, influencing,‘Gets things done’ Investigate broad policy, challenge and examine decisions, review Weighing and determining applications and appeals; direct regulation (discretion) Responsibility of all politicians to their electorate Meeting skills, research, influencing Critical questioning Representation, research, judgement Analytical skills, care, attention Listening, advising, facilitating, research Interested in people, service ethos Diversity Index Ranged profile of leader behaviours Demography (population profile, social change) Scale of change, social diversity No special requirements … Sensitivity, cultural awareness, ability to engage diverse groups Community (consumerism/expectations) Level of social cohesion Foster community initiatives … Encourage wider levels of participation Economy (level of wealth, employment) Levels of wealth, educational attainment, employment Engage poorer parts of community, lobby for funding … Foster growth, satisfy electorate Government (local, regional/national agenda) Relations with other layers of government Consolidate, build on regional/national identity … Negotiate greater regional/national autonomy Partnerships (providing > influencing role) Extent of partnership arrangements Providing services, fostering partnerships … Fiduciary competence, collaborative skills Control or opposition (political stability, influence, culture) Majority/NOC/minority Entrenched/progressive Leading/influencing & persuading … Role model for change/facilitative – empowering, persuading Political allegiance (to party, to government) Ties and lo yalty to party or other political bodies Relative independence from party … Close ties Legitimacy (accountability, open government) Levels of representativeness and turnout Build on democratic legitimacy … Increase visibility and links with voters Modernization (reform agenda and mandate) Perceived effectiveness at innovation and improvement Consolidate strengths … Implement reforms to enhance improvement Technology (eGovernment) Degree to which technology is integrated, used and understood Enable and promote learning and access … Drive forward innovative technologies Size (population, size of council) Population served, number of officers, civil servants Managing bureaucracy, centralization … Leveraging limited resources Information on roles, responsibilities, profile and context is drawn from Stewart (2003), roles found at local, regional, national and international level. KSAs = Knowledge, skills, attitudes. Figure 1 Dimensions of contextual diversity for political leaders Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership Regulatory Responsibilities 487 488 Human Relations 59(4) this context, though as we argue, this summary is potentially applicable to all forms of political leadership as earlier defined (see Figure 1). The framework represents the inherent contextual diversities faced by political leaders. It illustrates these across several domains, which influence how leadership is constructed and enacted. Column 1 shows four generic roles which political leaders undertake: executive, scrutiny, regulatory and advocacy (Stewart, 2003). These are formal descriptions of leadership roles for local politicians in England and Wales, but can reference activities common to political leaders in other contexts, at other levels of government, and in other countries. For each, there is a range of responsibilities, some of which may be part of the role, while others may be self-chosen (column 2). From the responsibilities can be derived a role profile, where a range of knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSAs) are desirable (column 3). Importantly too, political leaders should share some of the values that pertain to living in a democratic society, for example, accepting diversity, and seeking to take into account the interests of all constituents not just those who share one’s political allegiances. They should also be people of integrity and probity since they are responsible for administering public monies and making decisions that have an impact on economic and social well-being. Alongside these generic profiles, we list several dimensions of the context for their leadership, the ‘contextual filter’ (as bracketed). These will vary from place to place, and differences will influence their constituents’, and leader, priorities. Column 4, ‘diversity’, lists each dimension. Column 5, ‘index’, operationalizes the ways in which these may differ. We suggest each dimension can be operationalized with ordinal or scalar measures. Column 6 briefly hypothesizes different behaviours that are likely to prove more or less effective in the light of the particular context. This account does not imply a mapping of the context for each political leader; instead, it illustrates dimensions along which the context is in flux. This offers greater scope than models that are static or exclusively focused on content, or that fail to acknowledge the importance of structural elements. To develop Figure 1, below we describe different contextual features that shape the domains within and across whose boundaries politicians operate. To provide clarity and sufficient detail, this is illustrated using the policy and academic literatures dealing with local government (Hartley & Benington, 1998; Wilson & Leach, 2002). This preserves a consistent level of analysis in the sections that offer in-depth description of contextual complexity. However, we contend that the logic informing this account of political leadership, applies at regional, national and supranational levels, and that Figure 1 stands as a visual summary that is transferable to these Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership contexts. Our account describes three arenas of diversity, respectively: the ‘place’, whether local, regional or national; the ‘authorizing environment’ (Moore, 1995), and the ‘organizational environment’, for example, the local authority, a regional assembly, or national and supranational parliaments. Within each category are a number of sub-categories that influence the diversity of the leadership task. The ‘place’ Some local governments in the United Kingdom (UK) have a relatively stable population where the pace of demographic change is low, for example, certain rural settings with limited inward migration. Other councils face challenges of coping with, for example, national growth plans, economic migrants or asylum seekers. Changes may put pressure on the provision of local public services and the political choices this requires. Political leaders may have to be able to represent and articulate the views of a diverse population. The level of social cohesion also varies immensely. In some areas, where there is a strong sense of community, political leaders may act in a facilitative role, consolidating existing networks; in other areas there will be a challenge to reach out and create a sense of community. The political leadership roles and challenges are likely to be different in these different circumstances (Leach et al., 2005). Finally, the economy affects challenges for political leaders. For example, with high unemployment and social deprivation there may be associated problems of low educational attainment and crime (Lupton, 2003) and a key role for political leaders may be to attract extra resources. Deprivation may also have a depressive impact on aspirations. In areas where there is high employment and prosperity, the local community may create greater demand for more complex service provision. The ‘authorizing environment’ In the UK, local government is highly dependent on central government for legislative and financial freedom. This contrasts with the USA, for example, where authority essentially derives from local government upwards to state and federal bodies. In the UK, there is variation between councils in the degree to which they have achieved some (limited) degree of autonomy from central government. Shifts in emphasis in the role of local government from service provider to collaborative partner in service provision have been pronounced in the last decade (Leach & Wilson, 2002). Some authorities are well practiced in developing suitable partnerships to enact these changes (Geddes & Benington, 2001). In others, political leaders are building these 489 490 Human Relations 59(4) relationships from scratch, which requires a different set of skills and leadership processes. The distribution of power within a local authority may influence the repertoire of behaviours politicians can deploy. For example a minority group opposition faces different challenges to a majority party administration. This may affect the relative emphasis leaders place on core skills, for example, influencing, facilitating, and persuading. Allegiance differs across councils according to how integrated the controlling group is with their political party’s national structure (Leach & Wilson, 2002). This can influence the degree of freedom with which a political leader can operate. Finally, different factors affect the legitimacy of leadership. First, electoral turnout varies across councils and can adversely affect the legitimacy with which politicians govern (Rallings et al., 1996). Second, where councillors are unrepresentative (in terms of demographic characteristics) this may reduce perceptions of legitimacy (Employers’ Organization & I&DeA, 2001). Third, political leaders act in different roles: enforcing and influencing regulation, being advocates, and having responsibility for service provision. This can make it difficult to articulate the relationship between leaders and the communities they govern (Ranson & Stewart, 1994). There may be diverse interpretations of local politicians’ accountability (Pollitt, 2003). Each facet of legitimacy illustrates how leadership is socially constituted. The ‘organizational environment’ The challenge of responding to pressures for reforms is met differently across different politically led organizations, and performance across these also varies. Authorities are likely to be in a position of consolidating on existing strengths, or working hard to reform. Irrespective of the legitimacy of performance ratings (Boyne & Enticott, 2004), these influence stakeholder perceptions and affect the priority political leaders give to internal organizational improvement (Leach et al., 2005). Local authorities also vary in their ability to deploy technologies. These can enhance local democracy and improve the ability of authorities to link with other agencies (Martin, 1997). Though identified as an explanatory variable for a range of phenomena (Child, 1984; Pugh, 1981), few studies explicitly consider the relationship between organizational size and leadership. However, there is reason to expect that the size of a local authority and its population are likely to influence the behaviours of political leaders (Boyne, 2003). For example, the largest local authority in England serves over a million people, with more than 100 elected politicians. Smaller local authorities may serve a population of under 30,000, with fewer than 20 politicians. This variety has implications for the structure of the organization, but also for governance arrangements, Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership and the management of the authority. Having discussed the particular characteristics of, and contexts for, political leadership, the following section briefly reviews the current leadership literature to assess its suitability for studying this phenomenon. The literature on leadership Grint’s The arts of leadership (2000: 2–3) discusses four kinds of leadership theory: trait approaches, contingency approaches, situational approaches and constitutive approaches. He categorizes these according to whether they emphasize the individual or the context as essential. Trait approaches are ‘essentialist’ in terms of the leader but ‘non-essentialist’ in terms of context: ‘a leader is a leader under any circumstances’. Contingency approaches are essentialist in terms of the leader and the context: ‘both the essence of the individual and the context are knowable and critical’. Situational approaches are essentialist in terms of the context, but not in terms of the leader: ‘certain contexts demand certain kinds of leadership – so we do need to be very clear about where we are’. The fourth kind, constitutive approaches, are nonessentialist in terms of the leader and the context: the meaning of context and leader are both contested, ‘leadership must still be perceived as “appropriate’’, but what that means is an interpretive issue’. We use this framework to examine briefly the academic literature on leadership, with a view to assessing its suitability for understanding political leadership. Trait approaches Much leadership research views leaders as individuals with a particular set of traits or abilities, or sees leadership as the exercise of particularly effective sets of behaviours. Leadership dimensions have been developed for example for health service managers (Alimo-Metcalfe & Alban-Metcalfe, 2001) and trait-based approaches have informed the study of union leaders (Metochi, 2002). Similarly, recent theories hypothesize linkages between type of leader and a dependent variable(s). For example, transformational leadership traits have been linked with: knowledge creation, organizational performance, follower self-concordance, work alienation, creativity, and higher order motives (see Vera & Crossan, 2004 for a review). Other studies examine charismatic (Javidan & Waldman, 2003) and transcendental leadership (Sanders et al., 2003) in a similar fashion. This approach exhibits paradigmatic consensus (Pfeffer, 1993); that is, given terms (transformational and transactional leadership) are commonly understood, and there is a 491 492 Human Relations 59(4) methodological consensus – using inventories to assess the type of leadership, and a range of measures to assess the dependent variables (Barker, 2001). One advantage of having paradigmatic consensus is that there is less debate over first assumptions. However, this can be a limitation if it leads to the monolithic representation of phenomena, or leaves little room for diversity in approaches (Zald, 1997). One reason that trait accounts are limited is that they underplay the importance of leaders’ interdependence. For political leaders, effectiveness and identity is not merely a function of character, but socially constituted in a rich, dynamic context, and subject to structural constraints and opportunities. Contingency approaches The most influential contingency model is by Fiedler (1967), which emphasizes leadership style in combination with the relevant features of a given situation. This suggests that performance is a function of leaders’ style and some key features of the context (leader–follower relations, task structure, position power). A contemporary example offered by Liu et al. (2003: 127) suggests leadership styles should be matched to the modes of working of employees, as determined by the ‘objectives and psychological obligations underlying different groups of employees’. Other contingency approaches consider top management teams (upper echelons theory), or shared leadership, where the characteristics of an elite group are viewed as appropriate to a particular context (Ensley et al., 2003; Papadakis & Barwise, 2002). Contingency approaches have an advantage over trait accounts in that they acknowledge the role of context. However, they also imply a mechanistic relationship between style and context, as suggested by notions of ‘matching’ and ‘fit’. This is an instance of a dualist framing of leadership, between ‘the individual and the system’ (Fairhurst, 2001). The difficulty of applying this to politicians is that the context is constantly changing and can be different depending on the nature of particular challenges, or the different actors with whom they interact. Political leaders’ networks are not static, as is implied by the idea of a prevailing mode of working, instead they are highly fluid. Changes in these, or the wider context, influence the contingencies of leadership. Situational approaches There are two prominent theories of situational leadership. Vroom and Yetton (1973) identify five leader decision-making styles, and Hersey and Blanchard (1988) suggest leaders adapt styles to suit the readiness of their Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership followers to perform. In both models, the context determines which style is appropriate. Situational approaches, like contingency approaches, acknowledge the importance of context and thus offer advantages over trait accounts. However, they overlook the ways in which leader and context may be interdependent. This is a limitation because political leaders are concerned with developing far-reaching policies that govern the ‘authorizing environment’ (Moore, 1995) within which organizations and institutions operate. This makes it harder to treat ‘context’ for political leaders as a given (Leach et al., 2005). Managerial leaders typically promote the interests of an organization, or less typically, a coalition of organizations with shared interests. Though managerial leaders have a moral duty to consider what may be loosely called ‘stakeholders’, political leaders bear the social expectation that they will consider the impacts of their decisions on every group in their constituency, and sometimes beyond. These groups may have competing values and goals, so the challenge is to address difficult problems where there is conflict as to what the criteria informing decisions should be, and less consensus about desired outcomes (Burns, 1978; Heifetz, 1994). There is also likely to be disagreement over how outcomes are measured (Behn, 2003). This in turn implies interdependence between leaders and other actors in a network, which an exclusive focus on trait, situational or contingency approaches does not provide. Constitutive approaches The constitutive approach contests the objectivity of the terms ‘leader’ and ‘context’, emphasizing the role of interpretation and the way in which these terms are interrelated (Denis et al., 2001). Though there is less literature on this approach, the logic underlying it can partly be seen in leader member exchange (LMX) theory (Dansereau et al., 1975). This holds that leaders use different leadership styles with different groups of subordinates (Sparrow & Liden, 1997), and where assignment to a favoured ‘in-group’ results in favourable, informal exchanges between leaders and members, whereas ‘outgroup’ interactions are more task-oriented and formal. Following these analyses, the leader and the context (in terms of work group) are defined relationally (Leach et al., 2005). One of the potential benefits of a constitutive approach is that it allows space to explore the ways in which leadership is socially constructed (Grint, 2000, 2005; Heifetz, 1994). This opens opportunities for alternative methodological paradigms, such as ethnography, and methods such as discourse or narrative analyses (Putnam & Fairhurst, 2001). A limitation is that exclusive focus on constitutive accounts makes it harder to pursue prevailing nomothetic paradigms based on quantitative methods. 493 494 Human Relations 59(4) Developing the study of political leadership The brief review above suggests there are shortcomings in each approach identified by Grint’s study of contemporary leadership research. Though we accept these may adversely affect the study of other forms of leadership, there is good reason to address these shortcomings as they concern study of political leadership in particular. Political leadership is a relatively understudied, though discrete and substantive area of interest and in this sense there is more scope to influence future research than in areas where there is a well-established body of literature (McKinley et al., 1999). In addition, for theoretical reasons, it is interesting to explore a phenomenon where: i) structural similarities (as outlined in the earlier definition) persist across different levels, and different geographical areas; and ii) a large number of actors operate in circumstances and settings that are respectively very different (Figure 1); and with iii) different levels of effectiveness. Since political leadership involves relationships of interdependence between leaders, the organization(s) and the context, separately defining ‘leader’ and ‘context’ can be limiting. This suggests that trait, contingency and situational approaches may be usefully complemented by a constitutive approach. For example, certain ‘truths’ about political leadership and leader effectiveness are constructed by the media, by opposition parties, by political colleagues and by constituents and activists (Grint, 2000). The interpretation of particular events such as crises may be inseparable from considerations of leadership (Boin & Hart, 2003). Political leaders also operate across interorganizational domains (Hartley, 2002). Though this is true for (senior) managerial leaders, the influence of political leaders is more fundamental since they govern the institutional and regulatory context for activity (Moore, 1995). Their activity is also multi-nodal in that they must consider the impact of change on different constituencies (Heifetz, 1994). In illustrating the limitations of an exclusive focus on any of the prevalent approaches to studying leadership, we have emphasized how understanding of the individual and understanding of the context are relationally configured, thereby rejecting the dualism implied by casting the individual and the context as separate (Fairhurst, 2001). Different epistemological approaches address the interrelation between individual actions and social structures in diverse ways. Rather than dwell on each at length, introducing and outlining some of these briefly is sufficient to position our argument and epistemology. Systems theory (Senge, 1990; Shaw, 2002) emphasizes interconnectedness, causal complexity and the relation of parts to the whole (Ackoff, 1994). By challenging the notion that social systems can be understood in terms of component parts, it frustrates simple causal explanations Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership of behaviour or outcomes, and underlines the difficulty of predicting the effects of interventions in social practices. Structuration theory was developed to address the problem of how to explain the relationship between individual actions and social structures (Giddens, 1984). One mechanism for doing this is to describe how shared schema (‘scripts’) mediate relations between individual actions and social structures, and influence both recursively. Actor network theory (Latour, 1996), and other approaches to analysing language, such as (D)discourse theory (Honan et al., 2000) or critical discourse analysis (Potter & Wetherell, 1987), interpret social practices by analysing the way in which texts are presented, and deployed as resources. The privileging of some modes of discourse, and identification of antinomies can indicate hegemonies or ideologies that pattern relations and activities, as well as influence the uses and distribution of power in social groups (Foucault, 2002; Putnam & Fairhurst, 2001). A host of other approaches fall under the broad banner of network analysis, including collective action theory, public goods theory, transaction cost economics theory and social capital theory (see Monge & Contractor, 2001 for a review). Though varied, what these share is a concern with relationships and interactions among a given set of actors, and a focus on social processes as well as attributes (Katz & Kahn, 1978). In our model, we use Elias’s term ‘figuration’, which refers to a network of interdependent actors, and the actors themselves (Dopson, 1997; Elias, 1978). Figuration provides a useful, shorthand way of talking about relationally complex domains such as those that characterize the different arenas of politics. More broadly, figurational sociology offers a useful way of interpreting such relational complexity (Newton, 2002). In comparison with the perspectives sketched above, figurational sociology has some advantages that suggest it can be a useful counterpoint to the individual–system dualism in leadership research. First, figurational sociology is primarily focused on people and their interrelationships. As Figure 1 suggests, there are many ways in which leaders’ interactions may be influenced by the context but an important feature of political leadership is the diversity of people with whom they interact in a formal capacity, for example: members from the same party at various levels; other political leaders; representatives of unions, lobby groups and communities of interest; business leaders; and individual voters. In each case, interactions are part of a wider constellation of interrelationships, and recursively influence the context for other interactions. This is a more subtle rendering of interaction than economic approaches (e.g. public goods theory, transaction cost economics), which are expressed in terms of relationships of exchange (Poppo & Zenger, 2002). 495 496 Human Relations 59(4) Second, figurational sociology, or ‘process sociology’, is concerned with change, or ‘flux’ (Gouldsblom, 1977 in Dopson, 1997). ‘Systems thinking’ and some forms of network analysis are often employed in a diagnostic fashion, used in response to implementing a particular change, to shape future strategy, to model a complex process, or as a problem-finding tool (Weisbord & Jaroff, 1995). Similarly, whereas some types of linguistic analysis, such as critical discourse analysis, are acutely sensitive to the particularities of a given context, other more established traditions within sociology, such as sociolinguistics, may treat social structures as given, rather than as being in the act of created (Putnam & Fairhurst, 2001). A third, related advantage is that figurational sociology builds the notion of power into analyses of social networks (Newton, 2002). In any network where actors are not wholly controlled, interdependencies and differential power relations produce a complex interweaving of interests and agendas. One implication of this is that search for single causes is futile, which suggests common ground with systems approaches (Senge, 1990). However, a process approach places more emphasis on how such relationships are in a state of flux, or becoming. The stress on differential power relations, or ‘power chances’, is relevant to understanding political leadership, because in democracies, political leaders’ authority is constantly under scrutiny and they are accountable to different constituencies. Political leaders have to build groups and coalitions to address complex problems (Heifetz, 1994). Also, their authority is dependent on consent, and open to challenge from many quarters. A model of political leadership In light of this discussion, we propose the following (see Figure 2) as a model of political leadership. In doing so, we respond to the call for more theorizing in public sector research (Ferlie et al., 2003; Martin, 1997). By incorporating the contextual filter developed in Figure 1 this captures some sense of the complexities of political leadership. Additionally, it illustrates that leadership is not the province of an individual, but something that is relationally enacted, as represented by the bidirectional arrows. Equally, it incorporates each of the four roles that political leaders variously carry out. The first section (roles, responsibilities and KSAs values) follows from the institutional and legal framework. Though we have used terms from local political leadership in the UK, we suggest these may be common to political leaders in other contexts. The second section (contextual filter) signals contextual contingencies relevant to political leaders, as per Figure 1. Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership 1 ROLES Executive Scrutiny Regulatory Advocacy RESPONSIBILITIES KSAs VALUES 2 CONTEXTUAL FILTER F2 F1 3 LEADERSHIP Fn PERFORMANCE Figure 2 A model of political leadership Notes (by section as numbered): 1. This is taken as axiomatic and following from the policy literature. 2. Contingent, as described in more detail in Figure 1. 3. Leadership is socially constituted and relationally constructed in various figurations. The third section (leadership) shows how leadership may be differently constructed within the different figurations (F1, F2 . . . Fn) in which leaders act. The fourth section (performance) is an outcome measure that shows how leaders’ actions, and the consequences of those actions, subsequently 497 498 Human Relations 59(4) influence future figurations and the contextual filter. Performance could be operationalized in various ways. We have insufficient space to develop this in detail, and measuring public sector outcomes is complex and contested (Morrell, 2006) but empirical measures could include electoral turnout, measures of employment, inflation or mortality. Research agenda As well as serving a heuristic purpose, Figure 2 can be used to frame a research agenda that illustrates how contemporary accounts of leadership can be applied in this setting. This capitalizes on the attraction of both visual and propositional forms of theory (Worren et al., 2002). To illustrate this we can usefully refer back to Grint’s framework of leadership theories. Though we have pointed out the limitations of an exclusive focus on any one of these, the model above can be used to develop a research agenda that usefully complements each approach in the following ways. First, in terms of the different roles leaders undertake, there are differences in the types of generic behaviours that these roles require (Stewart, 2003). For example, scrutinizing proposed policy requires a facility for asking the appropriate questions, and an ability to imagine the effects of policy post implementation. Acting as a representative (a function of all political leaders) requires empathy, a willingness and ability to listen, and a service ethic. Acknowledging the difference between these two roles could engender a more refined account of what ‘transformational’ behaviour could mean for example, since similar behaviours across these roles would not necessarily be equally effective. More specifically, trait or behavioural approaches can be encompassed in certain sections of the model. For example, research could explore the bidirectional relationship between leadership and the contextual filter. One might examine how different leader behaviours have an impact on the perceived effectiveness of reform within a public organization (council, party, national government). Outside the influence on the public body, one could evaluate correlations over time between leaders’ style and various outcome measures, such as employment or crime, or perceptions of different stakeholder groups (business, community leaders, minority groups). Ultimately, there may be a relationship between these behaviours and (re)election. This goes beyond a straightforward translation of trait-based accounts to this context since it foregrounds the complex, interrelated nature of leadership. This more carefully qualifies the reach of trait accounts. Second, in terms of the geographical location, there is reason to believe Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership that the challenges facing leaders, and their consequent requisite skills differ in different localities. This is not simply a case of comparing effectiveness of leadership in (say) a large, metropolitan area versus (say) a small rural setting. Location may be a proxy for a range of differences relating to demography, technology, social cohesion, etc. So, a contingency approach could be enhanced given the greater scope for modelling diversity encapsulated in the ‘contextual filter’. More specifically, contingency approaches could be used to develop hypotheses about the interaction between political leadership roles and the context. Similarly, the effectiveness of leadership in an executive function may be a function of the balance of power in a council, or of the type of executive arrangement (Leach & Wilson, 2002). This could be examined further in the diversity of elected mayoral arrangements. Third, one implication of cybernetics is that models should have requisite variety in order to study or represent a context or scenario (Ashby, 1956). In other words they should have sufficient complexity in their design to enable them to express the range of settings to which they are to be applied (Heylighen, 1992). Figure 1 shows a way in which the diversity of local government can be represented. The challenge of proposing a model of political leadership is that it needs to have sufficient variety built into it. This is not possible with existing approaches, but acknowledging the diversity inherent in the domains for political leadership could extend the reach of situational accounts. For example, local government could be measured according to the different dimensions and a rating could be given to them across each dimension (demography, community, technology, etc.). These could then be examined to see how and why political leadership is situationally specific. Additionally, situational approaches would suggest that certain kinds of leadership behaviour are likely to be more suitable to particular roles (e.g. scrutiny), than others (e.g. representative, or executive leadership). Fourth, common to trait and contingency accounts in particular has been an emphasis on the individual leader as homo clausus (‘enclosed man’, Elias, 1994), yet as Figure 2 illustrates, elected politicians work with others, or build groups or coalitions. Equally, their authority is dependent on consent. The model also illustrates how the particular context for a local authority will: a) influence the interpretation of generic role profiles, and b) influence the type of leadership behaviours deemed effective. The important thing to note about these two relationships is that they describe a figuration, an interdependent network of actors, and those actors themselves. Each phenomenon (profile of desired skills, contextual filter, leadership) is relationally constructed, as represented by the thick bidirectional arrows. Since leadership itself is a function of interrelations between various actors, this is represented by the thin bidirectional arrows. This offers scope to develop 499 500 Human Relations 59(4) constitutive accounts. One could study councils where there is perceived to be a ‘strong’ leader, and examine how far contextual factors engender this perception; or alternatively explore to what extent perceptions of ‘weak’ leadership may be attributed to context. Establishing a bidirectional link between the contextual filter and the four generic roles or profiles, and between the contextual filter and leadership would provide a validation of the constitutive approach, but could also enhance the reach of trait, contingency and situational approaches. Conclusion The detailed outline of the context for political leaders in Figure 1 offers scope to develop the extant literature on leadership. Trait accounts may be complemented or enhanced by this outline, since it stresses the importance of context. Equally, contingency approaches may benefit from alternative perspectives. Figure 1 illustrates how across various dimensions, a vast range of different circumstances within which political leaders act can be modelled. Acknowledging this can enhance the reach of situational models, since these typically posit a limited range of scenarios and strategies (Hersey & Blanchard, 1988; Vroom & Yetton, 1973). Figure 2 details relational complexity and underlines the notion that leadership is in flux. Whilst constitutive approaches are suited to exploring both these aspects of figurational sociology, the definition of political leaders, and discussion of particular roles signal the importance of structural factors in understanding political leadership. By stipulating specific dimensions, operationalizing these, and suggesting particular behaviours, our approach may complement constitutive accounts, offering a clearer empirical agenda for evaluating the ways in which leadership is relationally constructed. This article has offered a glimpse into the world of political leadership. In doing so we provide a model that illustrates the complexity and inherent diversity of the context for political leaders, addressing calls for further theorizing (Leach & Wilson, 2002). The models presented serve a heuristic purpose, as a summary of the ways in which contexts for political leadership differ (Figure 1), and as a representation of the complex way in which political leaders’ authority is configured (Figure 2). These also serve to orient future research, enhancing the various types of approach to studying leadership (Grint, 2000). Trait and behavioural approaches can be used to explore the relationship between the local context and the type of leadership that is effective. Contingency approaches can be used to test propositions relating to the effectiveness of particular behaviours in terms of the role of political leaders and their particular context. Situational approaches can be used to Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership test whether certain behaviours are more or less suitable in terms of political leaders’ generic roles, and examine leader behaviours across a range of contexts. Constitutive approaches can be developed using this model to extend the scope for empirical research through infrequently used paradigms, such as interpretivism and ethnography. Aspects of this approach could be extended to other contexts since, as we have argued, there are some generic similarities across different forms of leadership. Studying political organizations can also shed light on generic issues in organizational behaviour (Hartley, 2000). Here, however, our purpose has been to restate the importance and coherence of the political realm, allowing scope to explore this complex and substantive area in new ways. References Ackoff, R.L. The democratic corporation: A radical prescription for recreating corporate America and rediscovering success. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. Alimo-Metcalfe, B. & Alban-Metcalfe, J. The development of a new transformational leadership questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 2001, 74, 1–27. Ashby, W.R. An introduction to cybernetics. London: Chapman & Hall, 1956. Azzam, T. & Riggio, R.E. Community based civic leadership programs: A descriptive investigation. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 2003, 10, 55–67. Barker, R.A. The nature of leadership. Human Relations, 2001, 54(4), 469–94. Behn, R. Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review, 2003, 63(5), 586–606. Benington, J. The modernization and improvement of government and public services. Public Money and Management, 2000, 20(2), 3–8. Boin, A. & Hart, P.T. Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review, 2003, 63(5), 544–53. Boyne, G. What is public service improvement? Public Administration, 2003, 81, 211–27. Boyne, G. & Enticott, G. Are the poor different? The internal characteristics of local authorities in the five comprehensive performance assessment groups. Public Money and Management, 2004, January, 11–18. Brunsson, N. The irrational organization: Irrationality as a basis for organizational action and change. New York: Wiley, 1985. Burns, J.M. Leadership. New York: Harper and Row, 1978. Chambers dictionary, ed. C. Schwarz. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap, 1993. Child, J. Organization. Cambridge: Harper and Row, 1984. Collinson, D.L. Dialectics of leadership. Human Relations, 2005, 58(11), 1419–42. Cook, B.J. Politics, political leadership, and public management. Public Administration Review, 1998, 58, 225–30. Dansereau, F., Graen, G. & Haga, W. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 1975, 13, 46–78. Denis, J.L., Lamothe, L. & Langley, A. The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 2001, 44(4), 809–37. Dopson, S. Managing ambiguity and change: The case of the NHS. London: Macmillan, 1997. 501 502 Human Relations 59(4) Elias, N. What is sociology? London: Hutchinson, 1978. Elias, N. The civilizing process. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994. (Originally published 1939.) Employers’ Organization and I&DeA. National census of local authority councillors in England and Wales, 2001. Ensley, M.D., Pearson, A. & Pearce, C.L. Top management team process, shared leadership and new venture performance: A theoretical model and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 2003, 13, 329–46. Fairhurst, G.T. Dualisms in leadership research. In F. Jablin & L. Putnam (Eds), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research and methods. London: Sage, 2001, pp. 379–439. Ferlie, E., Hartley, J. & Martin, S. Changing public service organizations: Current perspectives and future prospects. British Journal of Management, 2003, 14, S1–S14. Ferraro, F., Pfeffer, J. & Sutton, R.I. Economics language and assumptions: How theories can become self-fulfilling. Academy of Management Review, 2005, 30(1), 8–24. Fiedler, F.E. A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. Foucault, M. The archaeology of knowledge. London: Routledge Classics, 2002. Geddes, M. & Benington, J. Social exclusion and local partnership in the European Union. London: Routledge, 2001. Ghoshal, S. Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2005, 4, 75–91. Giddens, A. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1984. Grint, K. The arts of leadership. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Grint, K. Problems, problems, problems: The social construction of ‘leadership’. Human Relations, 2005, 58(11), 1467–94. Hartley, J. Leading and managing the uncertainty of strategic change. In P. Flood et al. (Eds), Managing strategic implementation. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000, pp. 109–22. Hartley, J. Leading communities: Capabilities and cultures. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, Special Issue on Public Sector Leadership, 2002, 23, 419–29. Hartley, J. & Benington, J. Community governance in the information society. London: Foundation for Information Technology in Local Government, 1998. Heifetz, R.A. Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994. Hersey, P. & Blanchard, K.H. Management of organizational behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1988. Heylighen, F. Principles of systems and cybernetics: An evolutionary perspective. In R. Trappl (Ed.), Cybernetics and systems. Singapore: World Science, 1992, pp. 3–10. Hogget, P. Conflict, ambivalence and the contested purpose of public organizations. Human Relations, 2006, 59(2), 175–94. Honan E., Knobel, M., Baker, C. & Davies, B. Producing possible Hannahs: Theory and the subject of research. Qualitative Inquiry, 2000, 6, 9–32. Javidan, M. & Waldman, D.A. Exploring charismatic leadership in the public sector: Measurement and consequences. Public Administration Review, 2003, 63(2), 229–42. Katz, D. & Kahn, R. The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley, 1978. Kelly, D., Kelly, G. & Gamble, A. (Eds) Stakeholder capitalism. London: Macmillan, 2000. Kets de Vries, M.F.R. The spirit of despotism: Understanding the tyrant within. Human Relations, 2006, 59(2), 195–220. Latour, B. Aramis, or the love of technology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. Leach, S., Hartley, J., Lowndes, V., Wilson, D. & Downe, J. Local political leadership in the UK. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2005. Leach, S. & Wilson, D. Rethinking local political leadership. Public Administration, 2002, 80(4), 665–89. Liu, W., Lepak, D.P., Takeuchi, R. & Sims, H.P., Jr. Matching leadership styles with Morrell & Hartley A model of political leadership employment modes: Strategic human resource management perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 2003, 13, 127–52. Lupton, R. Poverty street: The dynamics of neighbourhood decline and renewal. Bristol: The Policy Press, 2003. Martin, S. Leadership, learning and local democracy: Political dimensions of the strategic management of change. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 1997, 10(7), 534–46. McKinley, W., Mone, W.A. & Moon, G. Determinants and development of schools in organization theory. Academy of Management Review, 1999, 24(4), 634–48. Metochi, M. The influence of leadership and member attitudes in understanding the nature of union participation. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 2002, 40(1), 87–111. Monge, P.R. & Contractor, N.S. Emergence of communication networks. In F.M. Jablin & L.L. Putnam (Eds), The new handbook of organizational communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001, pp. 440–502. Moore, M. Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1995. Morrell, K. Governance ethics and the NHS. Public Money and Management, 2006, 26(1), 55–62. Moss, J. Race effects on the employee assessing political leadership: A review of Christie and Geis’ (1970) Mach IV Measure of Machiavellianism. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 2005, 11(2), 26–33. Newton, T.J. Creating the new ecological order? Elias and actor-network theory. Academy of Management Review, 2002, 27(4), 523–40. Papadakis, V.M. & Barwise, P. How much do CEOs and top managers matter in strategic decision making. British Journal of Management, 2002, 13, 83–95. Pfeffer, J. Barriers to the advance of organizational science: Paradigm development as a dependent variable. Academy of Management Review, 1993, 18(4), 599–620. Pollitt, C. The essential public manager. London: McGraw Hill, 2003. Poppo, L. & Zenger, T. Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements. Strategic Management Journal, 2002, 23(8), 707–25. Potter, J. & Wetherell, M. Discourse and social psychology. London: Sage, 1987. Pugh, D.S. The Aston program perspective. In A. Van de Ven & W. Joyce (Eds), Perspectives on organization design and behaviour. New York: Wiley, 1981, pp. 135–65. Putnam, L.L. & Fairhurst, G.T. Discourse analysis in organizations. In F. Jablin & L. Putnam (Eds), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research and methods. London: Sage, 2001, pp. 78–136. Rallings, C., Temple, M. & Thrasher, M. Participation in local elections. In L. Pratchett & D. Wilson (Eds), Local democracy and local government. London: Macmillan, 1996, pp. 62–83. Ranson, S. & Stewart, J. Management for the public domain: Enabling the learning society. London: Macmillan, 1994. Robbins, B. (Ed.) The phantom public sphere. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993. Sanders, J.E., Hopkins, W.E. & Geroy, G.D. From transactional to transcendental: Toward an integrated theory of leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 2003, 9(4), 21–31. Senge, P. The fifth discipline. New York: Doubleday, 1990. Shaw, P. Changing conversations in organisations: A complexity approach to change. London: Routledge, 2002. Skelcher, C. & Mathur, N. Governance arrangements and public service performance. Birmingham: University of Birmingham, Inlogov, 2004. Sparrow, R.T. & Liden, R.C. Process and structure in leader member exchange. Academy of Management Review 1997, 22(2), 522–52. 503 504 Human Relations 59(4) Stewart, J. Modernising British local government. London: Palgrave, 2003. Thompson, J.D. Organizations in action. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1967. Vera, D. & Crossan, M. Strategic leadership and organizational learning. Academy of Management Review, 2004, 29(2), 222–40. Vroom, V.H. & Yetton, P.W. Leadership and decision making. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973. Weisbord, M.R. & Jaroff, S. Future search: An action guide to finding common ground in organizations and communities. San Francisco, CA: Berret-Koehler, 1995. Worren, N., Moore, K. & Elliott, R. When theories become tools: Toward a framework for pragmatic validity. Human Relations, 2002, 55(10), 1227–50. Yukl, G.A. Leadership in organizations, 2nd edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989. Zald, M.N. More fragmentation? Unfinished business in linking the social sciences and the humanities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1997, 41, 251–61. Kevin Morrell is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Governance and Public Management, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick. Dr Morrell’s interests centre on behaviour within organizations. To date he has carried out research into employee turnover, ‘leadership’, ethics and value in organizations. The empirical context for his research has been the public sector, viz. the National Health Service and UK local government. As well as drawing out and substantiating the wider implications of this research for other sectors, he has written cognate theoretical papers that are not sector specific. Before joining Warwick Business School, he was an ESRC postdoctoral fellow at Loughborough. [E-mail: kevin.morrell@wbs.ac.uk] Jean Hartley is Professor of Organizational Analysis, Institute of Governance and Public Management, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick. She is an organizational psychologist, whose work is concerned with political and managerial leadership, and organizational innovation and improvement in public services, particularly central and local government, health and the criminal justice system. She has developed a tool for assessment and development of formal political leadership, called the Warwick Political Leadership Questionnaire (WPLQ). Professor Hartley has experience of evaluation research for central and local government. She is currently the Research Director for the research that is monitoring and evaluating the Beacon Scheme concerned with interorganizational learning, innovation and improvement. She has recently been Lead Fellow of the ESRC/EPSRC Advanced Institute of Management Public Services Group. [E-mail: jean.hartley@wbs.ac.uk]