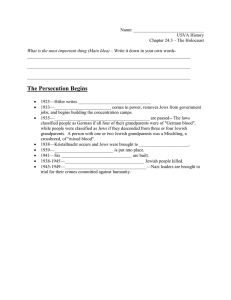

The Holocaust Seminar Studies - David Engel- 1670300060881

advertisement