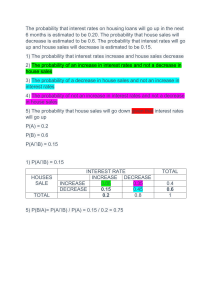

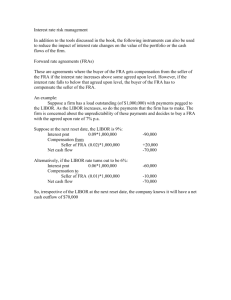

THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR WHAT’S INSIDE LIBOR: Getting to Transition U.S. LIBOR Transition: Demystifying SOFR Brave New World: Operationalizing SOFR! Flashforward: LSTA Releases Draft SOFR “Concept Credit Agreement” What’s Your Fallback? Aligning Loans and CLOs On Accounting, LIBOR Transition Has Been Relatively Smooth 1 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR LIBOR: GETTING TO TRANSITION BY MEREDITH COFFEY, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, RESEARCH AND PUBLIC POLICY L IBOR, “the world’s most important number”, is likely to cease after 2021. This presents significant—but hopefully surmountable—challenges. Below, we discuss the LIBOR problem, timeline and potential shorter- and longer-term solutions. We know whereof we speak; the LSTA is a member of the overall Alternative References Rates Committee (“ARRC”), the body tasked with replacing U.S. dollar LIBOR. We also co-chair the ARRC’s Business Loans Working Group (which is tasked with solving LIBOR transition problems for syndicated and bilateral loans) and the Business Loans Operations Subgroup (which is working to operationalize loan solutions), and are a member of the ARRC’s Securitization Working Group (where we represent the interests of CLOs.) WHAT IS THE “PROBLEM” WITH LIBOR? During the financial crisis, allegations of LIBOR manipulation led to banks paying billions of dollars of fines and people going to jail. Since then, banks have reduced their interbank funding (LIBOR) borrowings. As a result, there is only about $500 million of daily three-month interbank (e.g., LIBOR) trading. These trades are the informational foundation of the LIBOR quotes submitted by banks. These quotes, in turn, are used to create the LIBOR curve—and this LIBOR curve is used to price $200 trillion of contracts (including $4 trillion of U.S. syndicated loans and nearly $700 billion of CLO notes). If something were to happen to LIBOR—like it suddenly ceased or was deemed to be unreliable—there potentially could be significant issues for those $200 trillion of contracts. IS LIBOR “GOING AWAY” AFTER THE END OF 2021? It’s extremely likely. Due to potential legal liability and the small number of actual interbank trades, banks don’t particularly like providing LIBOR submissions. For now, the panel banks have agreed to continue their LIBOR submissions through 2021, but the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have said they would not compel banks to submit LIBOR thereafter. 2 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR LIBOR: GETTING TO TRANSITION, MEREDITH COFFEY At that point, banks may or may not submit LIBOR and LIBOR may or may not continue. That said, Andrew Bailey, CEO of the FCA recently stated that “We do expect bank panel departures from the LIBOR panels at end-2021. That is why we keep stressing that the base case assumption for firms’ planning should be no LIBOR publication after end-2021.” WHAT MIGHT REPLACE LIBOR? In the U.S., the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (“ARRC”) has identified the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”) as the LIBOR replacement for derivatives. SOFR is the combination of three overnight treasury repo rates. It is very liquid and very deep, with roughly $1 trillion of trading on a daily basis. This means that it will likely be robust, durable and hard to manipulate—all alleged shortcomings of LIBOR. It is highly likely that SOFR also will become the replacement rate for cash products like institutional term loans, FRNs and CLOs. HOW ARE SOFR AND LIBOR DIFFERENT? SOFR is an overnight, secured risk-free rate, while LIBOR is an unsecured rate with a term curve. Because SOFR is secured and risk-free, it theoretically should be lower than LIBOR. Moreover, SOFR, being an overnight rate, does not naturally have a “term curve”, in other words forward quotations of a 1-month and 3-month rate. WILL A SOFR “TERM CURVE” BE DEVELOPED? An “indicative” forward looking term SOFR has been developed from futures trading. In addition, the ARRC hopes to develop an IOSCO compliant “SOFR term reference rate” before the end of 2021. However, a forward looking term reference rate can only be developed if there are large and consistent SOFR futures trading volumes—and this is by no means guaranteed. Still, if a SOFR term reference rate cannot be developed, cash products could use a “compounded” overnight SOFR, which already exists. In fact, a safer bet might be to rely on compounded SOFR rather than waiting years for forward looking term SOFR. WILL SOFR BE ADJUSTED TO LOOK MORE LIKE LIBOR? Because SOFR is a secured, risk-free rate, it theoretically should be lower than LIBOR. In turn, market participants are working to develop a spread adjustment, which would make LIBOR and SOFR more comparable. This would be a one-time adjustment; it is meant to apply primarily to legacy LIBORbased loans that would need to transition to SOFR-based loans around LIBOR discontinuance. In December 2018, ISDA released the results of a derivatives fallback consultation, and expects to use a “historical mean/median” spread adjustment for derivatives. They plan to begin publishing the spread adjustment around year-end 2019. In addition, the ARRC has said that it would consider publishing a spread adjustment for cash products. However, it is likely that an ISDA spread adjustment would work equally well for cash products. HOW SHOULD LOAN DOCUMENTS EVOLVE TO ADDRESS A POTENTIAL CESSATION OF LIBOR? Loans tend to be relatively short-lived, are easily refinanced or amended, and always have had a “fallback” to Prime if LIBOR weren’t published. For this reason, syndicated loans already were in better shape than many other asset classes (many of which have longer tenors, limited fallbacks and are hard to amend). However, loans and CLOs still have their work cut out for them. In April 2019, the ARRC released recommended loan fallback language. There are two major components to LIBOR fallback language: First is the trigger event that initiates the transition from LIBOR to a replacement rate. (A simple example is LIBOR cessation.) Second is the fallback rate and spread adjustment. Below is a brief recap of fallback language; please see nearby article for a detailed analysis. The ARRC recommended fallback language includes two fallback options. The first approach—the “amendment” approach—is similar to, but more robust than, what occurs in the loan market today. First, a specifically defined trigger event must occur. Second, the borrower and agent identify a replacement rate and spread. Third, the “Required Lenders”, typically a majority, have a five-day window in which they can reject the proposed rate. The second approach—the “hardwired” approach—is similar to what is occurring in all other cash asset classes. When a trigger occurs, the loan immediately looks to a waterfall of replacement rates and spreads. The first stage of the rate waterfall is forward looking term SOFR plus a spread adjustment (either from ARRC or ISDA). If that does not exist, the second stage of the rate waterfall is compounded overnight SOFR plus a spread adjustment (either from ARRC or ISDA). If that doesn’t exist, the hardwired approach falls back to an amendment approach. Since the ARRC released its fallback recommendations, a number of loan agreements have utilized the “amendment” approach. Market participants agree that a hardwired approach likely will make more sense longer term, but are waiting until they have more clarity into SOFR behavior before locking in that rate. (See related SOFR FAQ for more details on its behavior.) WHAT ELSE DOES THE LOAN MARKET NEED TO DO TO PREPARE FOR A POTENTIAL CESSATION OF LIBOR? The loan market does not exist in isolation. Many loans have embedded hedges and are held in CLOs. In an ideal world, any transition from LIBOR to a new reference rate would occur simultaneously for the loan, hedge and CLO. In reality, the transition will likely be messier; however, market participants should consider the impact on other nearby markets and seek to minimize disruption. 3 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR LIBOR: GETTING TO TRANSITION, MEREDITH COFFEY Making the language of credit agreements (and CLOs) work in a potential LIBOR cessation environment is critical. However, market participants also have to consider other issues, like tax and accounting issues and operational challenges. Bank loan systems already are being recoded to manage a number of different types of interest rates. The way the loan market calculates delayed compensation may also change as the reference rate changes. In addition, issues like multicurrency facilities could be challenging. IS THIS ONLY HAPPENING IN THE U.S.? No. A number of jurisdictions are transitioning away from their relevant currency IBOR to an overnight risk free rate. In the UK, Reformed SONIA (Sterling Overnight Interbank Average Rate) has been identified as the appropriate replacement for GBP LIBOR (and in June 2019, the first SONIA bilateral loan was announced). In Switzerland, SARON (Swiss Average Overnight Rate) already has replaced the TOIS benchmark. In Japan, TONAR (Tokyo Overnight Average Rate) has been selected as the alternative to yen Libor. Some of these risk free rates, such as SONIA, are unsecured, while others, such as U.S.’s SOFR, are secured. In the context of multicurrency facilities, market participants should recognize that different currencies might transition to alternative rates at different times and the different alternative rates may require different spread adjustments. To facilitate an orderly transition, a number of global financial trade associations are collaborating to help ensure that there is coordination across jurisdictions and asset classes. SO WHAT IS THE LSTA DOING? The LSTA is on the ARRC itself, it co-chairs Business Loans Working Group (which developed the LIBOR fallback language) and the Business Loans Operations Subgroup (which is operationalizing SOFR and other potential replacement rates), and is a member of the ARRC’s Securitization Working Group (where we represent CLOs), the Accounting Working Group and the Infrastructure Working Group. We are working actively within the ARRC framework, and we also are coordinating globally with other trade associations such as the LMA, ISDA, the ABA, SFIG, SIFMA, CREF-C and more. In addition, at the end of 2018, we began to tackle operational challenges that a transition away from LIBOR will bring. We firmly believe that if market participants recognize the challenges and mobilize now, an orderly transition is doable. We encourage you to join our efforts. For more information, please contact us! LSTA LIBOR team leaders are Meredith Coffey (mcoffey@lsta.org) for policy and market impact, Tess Virmani (tvirmani@lsta.org) for legal/ documentation, Ellen Hefferan (ehefferan@lsta.org) for operations and Phillip Black (pblack@lsta.org) for accounting. 4 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR U.S. LIBOR TRANSITION: DEMYSTIFYING SOFR BY MEREDITH COFFEY, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, RESEARCH AND PUBLIC POLICY FIGURE 1: 1M LIBOR VS 1M FORWARD LOOKING TERM SOFR 1M LIBOR 1M Forward Looking Term SOFR 2.5 2.25 2 SEP 19 JUL 19 AUG 19 JUN 19 APR 19 MAY 19 MAR 19 JAN 19 FEB 19 DEC 18 NOV 18 SEP 18 1.75 OCT 18 • Forward Looking Term SOFR. This rate would be most analogous to LIBOR in that it would have a term curve and likely be quoted as 1-month or 3-month SOFR. It would be easy to operationalize in loan systems—after all, it locks an interest in in advance, just like LIBOR—and would require few changes to conventions. The negative is that SOFR is actually a daily rate and a Forward Looking Term SOFR would have to be extrapolated from SOFR futures trading. Though an indicative Forward Looking Term SOFR exists today, there is no guarantee that an IOSCO Compliant Forward Looking Term SOFR reference rate can be created. In order for a forward rate to be robust and stable enough to be an IOSCO compliant reference rate, it will have to have significant history and be comprised of a significant and consistent volume of futures trading. Moreover, if lenders simply wait for Forward Looking Term SOFR to exist, the necessary overnight SOFR futures trading won’t occur and a forward looking reference rate won’t develop. Classic chicken-and-egg problem. • Simple Daily SOFR in Arrears. This is the simple—not compounded—rate that accrues during the interest period. Continuing the hypothetical example, for a 30-day loan contract beginning on April 1, the parties would take the daily AUG 18 The derivatives market has determined it will use “SOFR Compounded in Arrears” for its LIBOR fallbacks. However, there are four potential SOFRs that cash products may use: • SOFR Compounded in Arrears. This rate would be compounded during the life of the loan contract. Continuing the hypothetical example, for a 30-day loan contract beginning on April 1, the parties would take the daily SOFR rate (or, potentially, the outstanding balance) and compound it each day through April 30. The positives are that it is the exact real interest rate for the contract period and it’s perfectly hedgeable with swaps. The first negative is that the final rate would not be known at the start of the interest period; this may not be a fatal flaw as the accrued rate would be known at any point in the period and, per the charts below, it would be easy to observe the expected rate in the futures market. Second, loan conventions would need to change and this type of rate would be more complex to operationalize. (We will discuss the operationalization approaches in another section.) JUL 18 We begin with a short explanation of the potential new reference rate. SOFR is comprised of three overnight U.S. Treasury Repo rates. This repo market is very liquid and deep, with around $1 trillion trading every day. Because this market is deep, observable and published by the Federal Reserve, it is hard to manipulate. In light of historical LIBOR experiences, this is a good thing. However, SOFR is also a risk free rate, and it is an overnight rate (as opposed to having a term curve like LIBOR). For these reasons, some adjustments may be needed for SOFR to work well in the cash markets. • SOFR Compounded in Advance. This is the rate that would be compounded over the previous 30/60/90 days. As a simplified hypothetical example, for a 30-day loan contract beginning on April 1, the parties would calculate the compounded rate from March 1-30 and lock it in on April 1. The positives are that, like Forward Looking Term SOFR, the rate would be known in advance and could be operationalized easily. The potential negative is that it could be perceived as being stale and could raise asset-liability management challenges. JUN 18 ost U.S. lenders and borrowers realize that LIBOR is likely to end sometime after 2021. However, they may be less familiar with SOFR, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, which will be the fallback for U.S. dollar derivatives and likely will be the fallback for cash products. Thus, lenders are keenly interested in seeing what SOFR actually looks like. To tackle that issue, we first define the potential SOFRs and then chart the different SOFRs to demonstrate their characteristics. We hope that as market participants become more familiar with the “look and feel” of the various SOFRs, they also will become more comfortable with developing hardwired LIBOR fallback language that references them. Rate (%) M Source: NY Fed, St Louis Fed 5 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR U.S. LIBOR TRANSITION: DEMYSTIFYING SOFR, MEREDITH COFFEY 2.25 2 1.75 JUL 19 AUG 19 JUN 19 APR 19 MAY 19 FEB 19 MAR 19 JAN 19 DEC 18 NOV 18 SEP 18 OCT 18 JUL 18 AUG 18 JUN 18 1.5 Source: NY Fed Next we compare the look and feel of Forward Looking 1-month SOFR against 1-month SOFR Compounded in Arrears. As Figure 3 illustrates, these rates are very similar. In fact, this should not be a surprise. After all, Forward Looking Term SOFR is the expectation of where interest rates should be, while SOFR Compounded in Arrears is simply where interest rates are. Unless there is an unexpected rate change or a period of unexpected volatility, the rates should be fairly similar. One of the reasons some lenders have been uncomfortable with SOFR Compounded in Arrears is that they would not know the exact rate they would receive and the borrower would pay. While it may not be possible to have a Forward Looking Term SOFR reference rate, it should be possible to see the indicative forward looking term rate. Though there would still be operational challenges around SOFR Compounded in Arrears, the lack of visibility into the ultimate rate probably should not be a stumbling block. FIGURE 3: 1M SOFR FORWARD LOOKING TERM SOFR VS. 1M SOFR COMPOUNDED IN ARREARS 1M SOFR Compounded in Arrears 1M Forward Looking Term SOFR 2.5 2.25 2 OCT 19 AUG 19 JUN 19 APR 19 FEB 19 DEC 18 1.75 OCT 18 In Figure 2, we compare 1-month SOFR Compounded in Advance to 1-month SOFR Compounded in Arrears. As one can quickly discern, these are exactly the same rates; the only difference is that the Compounded in Arrears rate (which is compounded during the life of the loan contract) predates the Compounded in Advance rate by one month. There has been some concern that SOFR Compounded in Advance might be stale in periods of rapidly changing rates or for particularly long interest contracts. This potential delay should be weighed against the fact that SOFR Compounded in Advance can be operationalized more easily. 2.5 AUG 18 While many lenders want a forward looking term SOFR, it is certainly possible that there simply will not be enough SOFR futures trading to create a robust IOSCO compliant forward looking term reference rate. For this reason, the market needs to plan for the possibility of using compounded rates. So what do they look like? 1M Compounded in Advance JUN 18 Figure 1 compares 1-month Forward Looking Term SOFR to 1-month LIBOR. As can be seen, SOFR and LIBOR differ. This difference is being addressed. The Alternative Reference Rates Committee (the “ARRC”), the body that is responsible for LIBOR transition in the U.S., has developed recommended loan LIBOR fallback language, e.g., language that addresses the question “If LIBOR ceases, to what rate does my loan fall back?” For loans that fall back from LIBOR to SOFR, the recommendations include a “spread adjustment” to make SOFR more comparable to LIBOR. In its hardwired version, the ARRC first recommends an ARRC-endorsed spread adjustment for cash products. If that doesn’t exist, the fallback language next recommends the ISDA spread adjustment for derivatives. While it’s not completely final, ISDA’s consultation results strongly suggest they would take a historical mean or median of the difference between LIBOR and SOFR to create the spread adjustment. 1M Compounded in Arrears Rate (%) But enough about what these rates are—how do they look and feel? The Federal Reserve has begun to publish an Indicative Forward Looking Term SOFR and Compounded SOFR on its website. To be clear, the indicative rates are only that; they are not to be used in contracts. So how do they look? FIGURE 2: 1M SOFR COMPOUNDED IN ADVANCE VS. COMPOUNDED IN ARREARS Rate (%) SOFR rate each day through April 30, but not compound it. The positives are that it is the exact real interest rate for the contract period, it’s close to hedgeable with swaps and can be operationalized fairly easily. The negative is that the rate, like Compounded SOFR in Arrears, would not be known at the start of the interest period. Again, this would mean that loan market conventions may change substantially to effectuate this type of rate. Source: NY Fed The LSTA is a member of the Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC), co-chairs the ARRC’s Business Loans Working Group (BLWG) and initiated a BLWG Operations Group. For more information, please contact Meredith Coffey (mcoffey@lsta.org) for policy and market analysis, Ellen Hefferan (ehefferan@lsta.org) for operations or Tess Virmani (tvirmani@lsta.org) for legal and fallbacks. 6 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR BRAVE NEW WORLD: OPERATIONALIZING SOFR! BY MEREDITH COFFEY, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, RESEARCH AND PUBLIC POLICY A t this point, most lenders know that LIBOR is likely to cease shortly after the end of 2021 and the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”) is very likely to be the replacement rate for syndicated loans and CLOs. While we know that, a major question remains: How do we make SOFR—a rate that is very different than LIBOR— work for the loan market? We explain some of the key issues for operationalization below. First, as noted in Demystifying SOFR, there actually are four SOFR rates that need to be operationalized. Two of the SOFR rates—Forward Looking Term SOFR and SOFR Compounded in Advance—are very similar to LIBOR and should be relatively simple to operationalize. The other two—SOFR Compounded in Arrears and Simple Daily SOFR in Arrears—are very different and will be much more complicated to operationalize. But there is a decent chance that the syndicated loan market will adopt SOFR Compounded in Arrears, and so it is necessary to operationalize it—and quickly! THE “KNOWN IN ADVANCE” SOFRS Like LIBOR today, borrowers and lenders would know their SOFR in advance of the interest period in a Forward Looking Term SOFR and SOFR Compounded in Advance world. If Forward Looking Term SOFR existed, there would be a forward looking 1-month or 3-month rate published every day. Meanwhile, SOFR Compounded in Advance would be compounded before the interest period begins and therefore the rate would be locked and known at the beginning of the interest period. (Thus, we define these as “Known in Advance” SOFRs.) This is the how LIBOR works today: one rate is plugged into loan systems at the beginning of the interest period and counterparties know the exact amount they will pay or receive, and lenders can easily calculate daily accruals. Thus, for the “Known in Advance” SOFRs, accruals, notices and payment periods can all behave the same way as they do for LIBOR today. The major systems’ change is that for loans that transition from LIBOR to SOFR, a spread adjustment must be added to SOFR to make it more comparable to LIBOR. So, this is very easy. Why isn’t it the sole solution? The first issue is that there is no guarantee that a Forward Looking Term SOFR reference rate will actually exist. It is contingent upon there being enough SOFR futures trading that a robust, stable and permanent forward looking term rate develops. That is by no means definite—and certainly not definite enough for all eggs to be put in this basket. Meanwhile, SOFR Compounded in Advance has the potential to be stale, particularly for longer tenors. For instance, in a rising rate environment, borrowers might be very interested in locking in long-tenored contracts to lock in a low rate for a long time. Meanwhile in falling rate environments, borrowers may trend toward shorter contracts to be able to replace the rate with a lower rate in the near term. This can make asset-liability management challenging. For these reasons, we cannot just assume that one of the “Known in Advance” rates will be the winner. And so, we also have to operationalize the SOFRs that are not “Known in Advance”. And we have to do it quickly. THE “NOT KNOWN IN ADVANCE” RATES The “Not Known in Advance” Rates represent a significant change for the market. For these rates, the interest rate is accrued daily over the life of the loan contract. For instance, here is a hypothetical—and simplified— “Compounded Balance” approach to compounding daily SOFR.1 In 30-day loan contract beginning April 1st, a lender/system would pull the April 1st interest rate on April 2nd and multiply it by the April 1st outstanding balance to determine the April 2nd interest. On April 3rd, the lender/ system would pull the April 2nd SOFR and multiply it by the April 2nd principal plus accrued interest as of April 1st to determine the April 2nd interest accrual. And so on every day for 30 days. (For Simple Daily SOFR in Arrears, the process for pulling SOFR daily is similar, but the process is much simpler because the rate is not compounded.) This is clearly a very different from a world where the rate is known in advance. So what are some of the conventions and systems requirements that have to change to operationalize these “Not Known in Advance” rates? • C ompounding: A critical convention is the recommended compounding methodology, which the ARRC Business Loans Working Group is developing. As of mid-October, there is ongoing debate on whether to compound the SOFR rate itself or compound the outstanding balance of the loan. However, most market participants agree that while SOFR should be compounded, any “spread adjustment” (which will be used to make SOFR more comparable to LIBOR) and the margin on the loan should not be compounded. Compounding only the SOFR rate works if there is no intraperiod prepayment of loans. However, it may be necessary to compound interest on the outstanding balance of a loan if the outstandings fluctuate over the interest period. 1 7 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR BRAVE NEW WORLD: OPERATIONALIZING SOFR!, MEREDITH COFFEY for borrowers to be billed and pay interest the same day. The solution for loans may be a “look back”, which creates a multiple-day gap between when the final interest rate is known, when the borrower is billed, and when the interest is paid. In effect, instead of beginning to compound interest based on the rate published on April 1st, loans would “look back” five business days to March 25th to begin the interest compounding period. Thus, April 1st would use the March 25th SOFR, April 2nd would use the March 26th SOFR…and so on until April 25th. On April 25th, the agent would know the full 30-day interest amount and would be able to bill the borrower. The borrower would then have five days to pay the interest. (A particularly weedy issue—into which we will not delve here!—is whether to use an “observation” shift, which basically would align the business days in a lookback with the weighting of that business day. Again, this is how ISDA’s methodology works, and would be the methodology in any SOFR Index that is developed.) • Tools: If the discussion above seems complicated, that’s because it is. But tools are being developed to help market participants consume LIBOR without doing complicated calculations themselves. First, the Fed is planning to publish official “Compound Averages of SOFR”. The benefit here is that lenders could pull these rates from screens and put them directly into systems and not do any calculations. While these Compound Averages may be most useful for SOFR Compounded in Advance, the New York Fed also is looking to publish a “SOFR Index”, which would internalize all the compounding and holiday conventions and simply spit out a compounded rate when a practitioner selected a start date and an end date. This could both simplify the operationalization of SOFR in loan systems and provide a simple public “golden source” to check the accuracy of interest rates. • Business Day Conventions: Compounding only SOFR aligns loans with derivatives and hedges, which market participants have said is important. But there are other compounding conventions that are necessary to align with derivatives. For instance, derivatives only compound interest on business days; an uncompounded rate is used on weekends or holidays. The loan market is likely to follow this convention. • Billing and Lookbacks: A “Not Known in Advance” rate introduces complexities in billing and paying interest. For instance, if a borrower has a 30-day loan that starts April 1st and accrues every day until April 30th, the final rate will only be known on May 1st. It is not fair • Next Steps: The ARRC’s Business Loans Working Group (BLWG) is developing a full list of recommended SOFR loan conventions. This list includes items mentioned above like compounding methodologies, spread adjustments, look backs and holiday schedules, as well as many other issues like rounding, break funding, SOFR floors and day count conventions. The BLWG is working with its counterparts in the UK, EU and Switzerland to align the recommended conventions as much as possible globally. These recommended conventions are being developed with business people, operations specialists and loan market vendors; this iterative process provides information for vendors to build systems that can internalize all variants of SOFR. And soon, the vendors should provide timelines on when systems should be SOFR-ready. For more information, please contact mcoffey@lsta.org or ehefferan@lsta.org. 8 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR FLASHFORWARD: LSTA RELEASES DRAFT SOFR “CONCEPT CREDIT AGREEMENT” BY TESS VIRMANI, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL & SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLIC POLICY R ecently, the LSTA took the next step in its efforts to educate market participants on replacement benchmarks by distributing a draft “concept credit agreement”1 referencing a compounded average of daily SOFRs calculated in arrears (“Compounded SOFR in Arrears”). The key points to highlight in the draft are discussed below, but readers should bear in mind that the draft is subject to evolution.2 WHY REFERENCE “COMPOUNDED SOFR IN ARREARS”? As we know, LIBOR is a forward-looking rate so it is known at the beginning of the interest period or “in advance.” By contrast, Compounded SOFR in Arrears is a rate that is not known until toward the end of the interest period. While this is a dramatic shift from the way loans, systems and credit agreements work today, Compounded SOFR in Arrears is the rate referenced by many SOFR floating rate notes, the first cash products to reference SOFR, as well as the designated fallback rate for USD LIBOR derivatives that will be incorporated into ISDA standard definitions next year. Moreover, it is the rate that both gives lenders the time value of money for their loans as well as being the most accurate average SOFR rate because the observation period for the rate more closely matches the interest period for which the rate is being determined. Remember, as the official sector has warned, a forward-looking term SOFR reference rate may not be available by 2021.3 For these reasons, the LSTA has developed this concept document. METHODOLOGY AND CONVENTIONS Any version of “Compounded SOFR” is determined by the calculation, methodology and conventions specified in the contract definition. The definition of “Compounded SOFR” found in the LSTA’s concept document follows the general formula used by the Federal Reserve Bank of NY in publishing its indicative compounded SOFR data and provides for a lookback with observation shift (the length of which is to be determined by the parties). A lookback with observation shift would shift the SOFR observation period (e.g., with a two-day business day shift, the observation period would start and end two business days prior to the interest period start and end dates) and each rate applies to the repo transaction period it represents. The use of an observation shift has a number of advantages: it applies the correct weighting to the daily SOFR rates, it would allow for the use of a published compounded SOFR index, and it is easier to align with hedges that have established the same observation period. While the use of a lookback with observation shift would allow for the use of a published SOFR index, the current definition of “Compounded SOFR” does not provide for the use of such an index because one is not currently available (please refer to footnote 9 in the draft concept document for more information). Another important point of discussion is with respect to “SOFR floors.” Largely for operational reasons, this concept document provides for a floor in the definition of “SOFR” (i.e., the daily rate that is used in calculating the compounded average of SOFRs) rather than in the definition of “Compounded SOFR” itself. This proposal is informed by conversations in the ARRC Operations WG, but it is acknowledged that it would be a change in practice to how floors are applied to LIBOR today and could possibly present challenges if Compounded SOFR is calculated using a SOFR index. COST-PLUS FUNDING In conversations with market participants, we have heard a general assumption that new SOFR term loans would be structured as simply referencing a SOFR variant plus the applicable margin, and would not include a spread adjustment intended to make the SOFR rate comparable with LIBOR going forward. Readers should note that this is in contrast to LIBOR-based loans that are falling back to SOFR, where the spread adjustment is designed to make the all-in rate of the loan comparable after the transition. The concept document was developed on this assumption and no spread adjustment is included. Also, given that SOFR, a broad treasury repo rate, may not be reflective of lenders’ cost of funds, “cost plus funding” (or “match funding”) provisions may no longer be applicable. Those provisions customarily in LIBOR-based loans, such as market disruption and breakfunding, have not been included in the concept document. With respect to breakfunding, it is important to remember not only that match funding is likely not applicable The draft was distributed to the LSTA’s Primary Market Committee and the LSTA’s SOFR Working Group for review and feedback and is available to any LSTA member on the LSTA website. 1 For reference purposes, a blackline against the LSTA’s draft LIBOR-based investment grade term loan which shows the cumulative changes made to convert a LIBOR-referencing term loan credit agreement into one referencing Compounded SOFR in Arrears. 2 For more information on SOFR, please refer to “U.S. LIBOR Transition: Demystifying SOFR” on the LSTA website. 3 9 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR FLASHFORWARD: LSTA RELEASES DRAFT SOFR “CONCEPT CREDIT AGREEMENT”, TESS VIRMANI for SOFR-based loans, but also that Compounded SOFR in Arrears is just compounded daily SOFRs so it is difficult to translate today’s LIBOR breakfunding provisions into similar provisions for Compounded SOFR in Arrears. SOFR FALLBACK LANGUAGE If this exercise has taught us anything, it is that nothing is certain. Therefore, the concept document includes robust fallback language if “Compounded SOFR” would no longer be available as a reference benchmark. In drafting this fallback language, we have included a modified version of the ARRC’s recommended “amendment approach” fallback language4 to apply its streamlined amendment process to a future transition away from SOFR. NEXT STEPS When reviewing the concept document readers are encouraged to keep in mind that the concept document does not purport to represent or set any standard market practice. It has been developed simply as a tool to further familiarize market participants with replacement benchmark alternatives, in this case Compounded SOFR in Arrears, which will hopefully further assist each institution with its own transition planning. The concept document will be discussed in detail at the LSTA’s Annual Conference in the “Post-LIBOR Credit Agreements: What Changes and What Stays the Same?” afternoon breakout session. Following the conference, the draft will continue to be open for written feedback from members. After considering all feedback received, the final “concept credit agreement” will be published. As the transition process unfolds, further iterations of the concept document may be developed. For further information on the concept document, please contact Bridget Marsh or Tess Virmani. Please refer to the ARRC website for the ARRC’s recommendation for syndicated loans and additional important information on the transition away from LIBOR. 4 10 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR WHAT’S YOUR FALLBACK? BY TESS VIRMANI, ASSOCIATE GENERAL COUNSEL & SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, PUBLIC POLICY W e know that LIBOR—the world’s ubiquitous benchmark—may well disappear after 2021. Now that we have entered the second half of 2019—with less than 800 days left to go to potential LIBOR cessation— market conversations have clearly evolved from questioning to accepting this fact. U.S. dollar LIBOR is the reference rate for nearly $200 trillion contracts, including $4 trillion of syndicated loans and nearly $700 billion of CLOs. Given its omnipresence in the financial world, the task of transitioning to a replacement mark is a daunting but necessary one. But where to start? Clearly, originating new loans that do not reference LIBOR is a top order of business, but that will take time. Triage dictates that we ensure that new LIBOR loans have robust, workable fallback language, i.e. the credit agreement clearly provides for an alternative and appropriate benchmark (or process for determining such benchmark) when LIBOR ceases. The Federal Reserve-sponsored Alternative Reference Rates Committee (ARRC) spent nearly a year developing fallback language for U.S. dollar-denominated syndicated loans (in addition to several other cash products) and in April the ARRC released recommended fallback language for syndicated loans (https://nyfed.org/2KeXvHn). The article below unpacks the ARRC recommendation, looks at early adoption of the language, and highlights key considerations for market participants as we continue the transition process. HOW WAS THE ARRC RECOMMENDED LANGUAGE DEVELOPED? The process began in the loan market itself. Historically, most syndicated loans provided for a fallback waterfall that would, upon LIBOR not being available, first revert to either the average of quotes in the London interbank market obtained by polling banks or the unsecured borrowing rate in the London interbank market for the administrative agent and then would ultimately fall back to the alternate base rate if such quotes cannot be obtained. This would mean that borrowers would be forced to pay significantly higher borrowing costs for the remaining life of their loans if LIBOR disappeared. Recognizing that this would not be a desirable outcome, credit agreement drafters responded to Andrew Bailey’s now famous speech foretelling the end of LIBOR by providing for a streamlined amendment process that would allow parties to a loan to select a replacement for LIBOR when that time came. Adoption of this new LIBOR replacement language has been widespread, but varies across agreements and is typically simply limited to the permanent end of LIBOR. The ARRC sought to build on what the market had developed to create fallback language that reduced systemic risk and minimized value transfer. The ARRC’s Business Loans Working Group (BLWG), co-chaired by the LSTA and ABA, is a group of many financial institutions who collaborated to develop the recommended language. The result was the release of two sets of fallback language— an amendment approach which built on the market’s LIBOR replacement language and a hardwired approach which would allow for LIBOR to be automatically replaced because all of the necessary terms are predetermined at the time the loan was originated. This latter approach is also closely aligned with the ARRC fallback language recommended for other cash products, such as floating rate notes (FRNs) and securitizations. Both approaches provide for trigger events that initiate the transition from LIBOR to a successor rate as well as the successor rate, and in doing so, try to ensure that LIBOR and the successor rate are made as comparable as possible upon transition. WHAT ARE THE ARRC’S RECOMMENDED TRIGGERS FOR LOANS? To avoid market disruption, the recommended fallback language for cash products like loans, FRNs and CLOs generally attempt to use the same triggers so that a transition would happen simultaneously for all products. Syndicated loans have three triggers that begin the transition process. The first two are “cessation” triggers which will also be incorporated in the ISDA fallback language for derivatives. The triggers state that either i) the benchmark administrator (like ICE Benchmark Administration) or ii) the administrator’s regulator (currently the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority) has announced the administrator has or will cease to provide the benchmark permanently. The third trigger, a “precessation” trigger, is a public statement from the LIBOR administrator’s regulator saying that LIBOR is no longer representative. One of the key features of the ARRC fallback language is the use of clear and objective triggers which are aligned with other cash products. In addition to the three triggers described above, the recommended fallback language for syndicated loans also has an “early opt-in” trigger to allow parties to begin moving away from LIBOR once an alternate benchmark has been accepted in the loan market. For the hardwired approach, once the administrative agent or borrower can identify that a certain number of loans have used Term SOFR, i.e. forward-looking term SOFR 11 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR WHAT’S YOUR FALLBACK?, TESS VIRMANI plus a spread adjustment, then the administrative agent, “Required Lenders” (typically a majority) and borrower can elect to switch to Term SOFR by affirmative vote. In the amendment approach, the administrative agent or “Required Lenders” can determine that loans are being executed or amended to incorporate or adopt an alternate benchmark and can elect to start the transition process. This rate is then selected by the borrower and agent and accepted by an affirmative vote of the “Required Lenders.” The triggers described above are common to both approaches, but how loans would transition away from LIBOR varies across the two recommended approaches. HOW DOES THE ARRC AMENDMENT APPROACH COMPARE TO CUSTOMARY LIBOR REPLACEMENT LANGUAGE? Given that the ARRC recommendations for other cash products do not include an amendment approach, inclusion of this approach for loans was not a foregone conclusion. There are, however, reasons that loans are treated differently in this regard. Unlike most cash products which are difficult to amend after they have been originated, loans do offer some flexibility and are routinely amended or refinanced during their life. It is understandable, therefore, 12 that market participants have decided to use loan flexibility to postpone selection of a successor rate until more is known about alternate rates and corresponding spread adjustments. The ARRC amendment approach draws heavily from the LIBOR replacement language that has been embraced by the market, but it also includes several enhancements to further minimize value transfer and increase operational feasibility. In the amendment approach, once a trigger occurs, the borrower and administrative agent may select a successor rate and spread adjustment, in both cases giving due consideration to a recommendation by the “Relevant Governmental Body” (such as the ARRC, the Federal Reserve Board or FRBNY) or relevant market convention. Once a successor rate is proposed to the lender group, lenders have five business days in which they can object. If lenders constituting “Required Lenders” object, then the loan will bear interest at Prime until agreement on a successor rate. If they do not object or the number of lenders objecting falls short of a majority, LIBOR is then replaced with the successor rate plus spread adjustment. This architecture, which balances expediency and fairness, is present in many credit agreements as we have seen THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR WHAT’S YOUR FALLBACK?, TESS VIRMANI even before the ARRC published its recommendation. In a recent study of 155 publicly available credit agreements dated between May 2018 and April 2019, Practical Law Finance found that 97% of credit agreements included similar LIBOR fallback language. Of that cohort, 97% of credit agreements provided “Required Lenders” with a negative consent right.1 The picture changes somewhat, however, when we focus on the institutional loan market. Covenant Review recently analyzed 107 credit agreements from August and September 2019 and found that 82% included a negative consent right, while 17% did not include a lender objection right and 1% included an affirmative lender consent right. While the vast majority of institutional loans do include a negative consent right for lenders, it is not true of all deals. It should be noted that including a negative consent for lenders, however, allows for a streamlined, efficient amendment process while reducing the discretion of administrative agents and providing opportunity to all stakeholders. The inclusion of a spread adjustment in the ARRC recommended fallback language is seen as important because it helps to minimize value transfer. For instance, because SOFR is secured and expected to be lower than LIBOR, a spread adjustment is necessary to make it more comparable to LIBOR (see related article–LIBOR: Getting to Transition). While the spread adjustment is a critical component to robust fallback language, it is also unknown today. Because the amendment approach language does not specify a successor rate—rather it outlines the path to selecting a successor rate—the spread adjustment is also not specified. The language provides that the borrower and the administrative agent will select the spread adjustment giving due consideration to a recommendation by the Relevant Governmental Body or relevant market convention. Given that some institutional loans do not include lender consent at the time of transition, an explicit placeholder for a spread adjustment is a benefit of the ARRC language. Aside from inclusion of the spread adjustment, the other notable features of the ARRC amendment approach are aimed at bolstering the feasibility of transitioning loans through an amendment process. The flipside to preserving flexibility in the amendment approach is that transition will require each LIBOR-referencing facility to be amended. If LIBOR should cease unexpectedly, it would be extremely cumbersome and costly to transition entire loan portfolios in a short time span. To address this fact, the ARRC language includes an “early opt-in trigger” described above and provides that, in the case of a preannounced cessation of LIBOR, the amendment process can begin up to 90 days before LIBOR ceases. Finally, the ARRC recommended language permits the administrative agent the unilateral 1 ability to make certain technical, administrative or operational changes that may be required to implement and administer the successor rate. It is foreseeable that certain changes to accommodate the successor rate will be required and this ability will allow for smooth administration of the loan. In the six months since the publication of the ARRC recommendations in April there has been some adoption of the ARRC language. Covenant Review's recent analysis also showed that 19% of reviewed credit agreements included the ARRC amendment approach language, while 81% included some form of LIBOR replacement language that had become customary in the loan market prior to the ARRC’s publication. We will see if the ARRC amendment approach takes a stronger hold in the market, but the ARRC recommendation does represent safer, more robust fallback language. The bigger shift will be adopting hardwired fallback language. At the time of writing, we are not aware of any credit agreements which include hardwired fallback language, but that will not always be the case. What it lacks in flexibility, the ARRC hardwired approach more than makes up for in certainty and operational feasibility. It obviates the possibility for gamesmanship because decisions are not made in an unknown economic environment. Moreover, if thousands of credit agreements need to be transitioned simultaneously, the amendment approach might simply not be workable. For these reasons, it is expected that the loan market will eventually adopt hardwired fallback language when the time is right—and that may not be as far off as it initially appears. HOW DOES THE HARDWIRED APPROACH WORK? The hardwired approach includes predetermined terms that provide a waterfall to select the successor rate and spread adjustment. It is also closely aligned with the ARRC recommended fallback language for other cash products, such as FRNs and securitizations and its successor rate waterfall uses two variants of SOFR—the chosen replacement rate for fallback language in U.S. dollar derivatives. Once one of the above-described triggers occurs, the hardwired approach first looks to replace LIBOR with forward-looking term SOFR plus a spread adjustment. If that does not exist, the hardwired approach next looks to replace LIBOR with a compounded average of daily SOFRs plus a spread adjustment. If that too does not exist, then the hardwired approach essentially falls back to the amendment approach as an escape hatch. In looking at the successor rate waterfall, there are several important considerations. First, the availability of a forward looking term SOFR reference rate— at the end of 2021 or beyond—is uncertain. Moreover, we Practical Law Finance, “Current Trends in LIBOR Successor Rate Provisions” (June 2019). 13 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR WHAT’S YOUR FALLBACK?, TESS VIRMANI know that fallback language for derivatives will replace U.S. dollar LIBOR with SOFR compounded in arrears (plus spread adjustment). For market participants that wish to align as closely with derivatives as possible, excluding the Term SOFR step of the waterfall is an option. (It is important to note that Term SOFR is the first step of the replacement rate waterfall in the ARRC recommendations for FRNs and securitizations as well, however the ARRC user’s guides to the FRNs, securitizations and syndicated loans recommendations state that removal of this step would still be consistent with the ARRC’s principles and recommendations.) Second, the next step of the replacement rate waterfall is a compounded average of daily SOFRs, but the language in the hardwired approach would allow for the rate to be calculated in advance (locking it in at the beginning of the interest period) or in arrears (accruing it during the actual interest period). For market participants who wish to keep alignment with derivatives, SOFR compounded in arrears would be the appropriate choice. While this SOFR variant would represent a significant departure from current practice and will require a systems overhaul, it is the rate that is likely to be used on a going forward basis by FRNs, securitizations and derivatives. As described above, SOFR is secured and thus expected to be lower than LIBOR so the hardwired fallback language must also include a waterfall of corresponding spread adjustments. The hardwired approach first suggests a spread adjustment selected or recommended by a Relevant Governmental Body. If that does not exist, the spread adjustment used by ISDA in their fallback language will be applied. such as institutional term loans, which may be sooner able to adopt a hardwired approach to fallback language. From a CLO perspective, in particular, achieving alignment in fallback language across CLO notes and the underlying loan collateral significantly reduces basis risk. For many market participants, understanding what the spread adjustment will be and seeing it published is a gating item for adopting hardwired fallback language in loans. However, ISDA has stated that their spread adjustment (designed for SOFR compounded in arrears) will be available around the end of this year. Once this important unknown is known, the hardwired approach may prove attractive to some loan market participants. For example, FRNs have begun adopting ARRC hardwired fallback language. Moreover, the recommendation ARRC recently published for securitizations, such as CLOs, only includes hardwired fallback language, and hardwired fallback language is being used in the CLO market. It is true that different segments of the loan market may not be accepting of the ARRC recommended hardwired language. For credit facilities, like revolvers, which may need incorporation of a credit component going forward, the ARRC recommendation which focuses on SOFR variants may not be as desirable. It is also true that the ARRC recommendations are specifically designed for U.S. dollar-denominated facilities. Multicurrency facilities pose unique challenges and it may take longer to develop a workable hardwired approach for those types of loans. Hopefully, these pockets of loans do not prevent the movement to a hardwired approach for market segments, Faced with the reality that LIBOR may not exist long after 2021, it is imperative that robust fallback language be included in all financial contracts. Fortunately, for the syndicated loan market, iterative versions of fallback language have been routinely included in new and amended credit agreements in 2018 and 2019. However, both sets of the ARRC recommended fallback language for syndicated loans represent safer, more balanced versions of fallback language. Market participants should educate themselves on the ARRC recommendations and choose to adopt the ARRC language where appropriate. Furthermore, the certainty, clarity and overall feasibility of hardwired fallback language should present many advantages for the market. Now that the FRBNY has published indicative forward term SOFR data and compounded SOFR data, the market has gained insight into how these rates look and feel. (For more information, please refer to U.S. LIBOR Transition: Demystifying SOFR.) Moreover, publication of an indicative spread adjustment to be used in ISDA's derivatives fallback language around the end of 2019, together with a known timeline for the operationalization of compounded SOFR, may tilt the balance in favor of hardwired fallback language sooner than we think. CONCLUSION 14 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR LIBOR: ALIGNING LOANS AND CLOs BY MEREDITH COFFEY, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, RESEARCH AND PUBLIC POLICY T he floating rate markets are busy preparing for the impending end of LIBOR. The first step many markets have taken is to develop workable “fallback” language, which answers the question “If LIBOR ceased, to what rate would my contract fall back?” Critically, both loans and CLOs need to have workable fallback language. And, it would be very helpful if both products fell back at the same time and to the same rate. Below, we discuss how fallback mechanics in both markets work, where they are aligned and where they diverge. There are $1.2 trillion of institutional loans outstanding, and nearly $700 billion are housed in CLOs. When the reference rates of loans and CLOs are not aligned, basis risk emerges. A particularly notable example of this occurred in 2018 when the 1-month/3-month LIBOR curve steepened and corporate borrowers switched to one-month LIBOR while CLO liabilities continued to reference three-month LIBOR. As we move from LIBOR to SOFR for institutional loans and CLOs, the potential of basis risk emerges in several ways. First, it will be important for both products to fall back to the same rate. Second, it would be preferable for them to fall back at the same time. And, third, if we fall back to a certain type of SOFR—specifically SOFR Compounded in Arrears—the 1-month/3-month basis noted above may nearly disappear. So, how would all this work? To begin, there are two major components of ARRC-recommended fallback language: 1) the trigger event that initiates the transition from LIBOR to a replacement rate and 2) the selection of a replacement rate (plus spread adjustment in most cases). The loan hardwired fallbacks (https://nyfed.org/2KeXvHn) and securitization fallbacks (https://nyfed.org/2KtLga7) (including CLOs) have both these components and the ARRC attempted to align them as much as possible. That said, there are some inevitable differences. (Note that because replacement rates are not predetermined in the “amendment approach” to loan fallbacks, it is not possible to determine whether they would be aligned with CLO liabilities.) TRIGGERS Loans and CLOs have the same “basic” triggers, but each add an additional trigger that permit earlier fallbacks. Both loans and CLOs have triggers if the LIBOR administrator or the relevant regulator announces that LIBOR has or will cease, or if the relevant regulator states that LIBOR is no longer representative. If any of these triggers occur, then loans and CLOs convert to a replacement rate at the same time. However, both loans and CLOs want the opportunity to shift to a replacement rate well before the end of LIBOR. For this reason, loans also have an “Early Opt-In” trigger, whereby if a certain number of loans are being issued or amended to shift to term SOFR, then the loan can be more easily amended to transition to SOFR. This permits lenders and borrowers to reduce their LIBOR inventory. Meanwhile, securitizations do not want to have liabilities tied to LIBOR if many of their assets are tied to SOFR. Thus, securitization fallback language also includes a trigger if more than 50% of a securitization’s assets have shifted to a replacement rate. WATERFALLS Both hardwired loan and securitization fallback language have a waterfall of replacement rates and spread adjustments. The first two levels of the waterfall are the same. After those two levels, the loan replacement rate is chosen via the amendment approach, while CLOs continue to work down their waterfall. The first waterfall level for both loans and CLOs is Forward Looking Term SOFR plus a spread adjustment. If Forward Looking Term SOFR does not exist, the second level is Compounded SOFR plus a spread adjustment. The preferred spread adjustment would be the one recommended by Relevant Governmental Body (ARRC or Fed); if that doesn’t exist, it would be the spread adjustment recommended by ISDA. If even that doesn’t exist, the securitization language also has a spread adjustment selected by the “Designated Transaction Representative” (e.g., someone designated to do this dirty work). As discussed above, if neither term SOFR nor compounded SOFR are available, then loans flip to the amendment approach, while CLOs continue down the replacement rate waterfall. The third level of the securitization waterfall is the rate of interest selected by the Relevant Governmental Body plus a spread adjustment. If that doesn’t exist, the fourth level is the ISDA Fallback Rate plus a spread adjustment. If that doesn’t exist, the final stage is that the Designated Transaction Representative selects the rate plus spread adjustment. 15 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR LIBOR: ALIGNING LOANS AND CLOS, MEREDITH COFFEY In fact, most hardwired adherents believe we will not go past the first two stages of the waterfall; after all, Compounded SOFR already exists and ISDA plans to publish the spread adjustment around year-end 2019. However, if for some reason this combination does not still exist at LIBOR cessation, CLOs and loans may diverge. MITIGATING BASIS RISK If loans begin to switch to SOFR first, this will introduce some basis risk into CLOs. However, if the market gets the spread adjustment right, the basis risk should be minimized. Forward Looking Term SOFR also could continue to have some basis risk if borrowers select onemonth SOFR and CLO liabilities are on three-month SOFR. Interestingly, if both markets move to SOFR Compounded in Arrears, the basis risk problem should be nearly eliminated because three-month Compounded SOFR is just a longer version of one-month Compounded SOFR. Ultimately, the best way to minimize basis risk around LIBOR transition likely is for both loans and CLOs to adopt a hardwired approach—and potentially skip directly to SOFR Compounded in Arrears. In such a world, the main triggers and fallback rate would be perfectly aligned. The LSTA is on the ARRC itself, it co-chairs Business Loans Working Group (which developed the LIBOR fallback language) and the Business Loans Operations Subgroup (which is operationalizing SOFR and other potential replacement rates), and is a member of the ARRC’s Securitization Working Group (where we represent CLOs), the Accounting Working Group and the Infrastructure Working Group. We are working actively within the ARRC framework, and we also are coordinating globally with other trade associations such as the LMA, ISDA, the ABA, SFIG, SIFMA, CREF-C and more. In addition, at the end of 2018, we began to tackle operational challenges that a transition away from LIBOR will bring. We firmly believe that if market participants recognize the challenges and mobilize now, an orderly transition is doable. We encourage you to join our efforts. For more information, please contact us! LSTA LIBOR team leaders are Meredith Coffey (mcoffey@lsta.org) for policy and market impact, Tess Virmani (tvirmani@lsta.org) for legal/documentation, Ellen Hefferan (ehefferan@lsta.org) for operations and Phillip Black (pblack@lsta.org) for accounting. 16 THE GREAT MIGRATION AWAY FROM LIBOR ON ACCOUNTING, LIBOR TRANSITION HAS BEEN RELATIVELY SMOOTH BY PHILLIP W. BLACK, ASSOCIATE, RESEARCH & PUBLIC POLICY W hile we’ve experienced plenty of challenges with the LIBOR transition, one area that has been relatively smooth is that of necessary accounting relief. Indeed, to the loan market’s great relief, we’ve helped the relevant accounting and tax bodies knock down the accounting hurdles this year like tenpins. The prime mover in the campaign to ease the transition’s accounting burdens has been the Financial Accounting Standards Board—the FASB—which in June promised to issue relief addressing the critical question of whether it would allow loans to be classified as “modified” following transition without undergoing the tedious and, in cases where many loans are held in portfolio, laborious 10% test. After announcing in July that it would also address the hedge accounting issues raised by transition, the FASB released a comprehensive set of relief in September, addressing both of these major issues at once. And the relief does pretty much what we hoped and expected it to do: it exempts loan market participants from conducting the 10% test on loans and allows hedging relationships to continue unchanged. So much for financial accounting issues. What about taxes? Copyright © LSTA 2019. All rights reserved. | 10-2019 Here, the relevant body isn’t the FASB but the Treasury, and its Internal Revenue Service. They have done their fair share of guidance issuing, too. In October, they issued proposed regulations clarifying that adjustments to debt contracts reflecting transition would not constitute modifications for tax purposes and thus would not result in income tax gains or losses—a big win for loan market participants who worried transition would trigger an unexpected tax event. Of course, these regulatory actions were in no sense preordained. They were the product of engagement, education, and encouragement on the part of private-sector groups that have been monitoring the situation most closely. Primary among these groups is the ARRC and its accounting and tax working group, of which the LSTA is a member. Indeed, the ARRC has been busy submitting letters, memos and analyses to the regulatory bodies identifying the problems and offering solutions. So while progress on the LIBOR front might appear in some places to be slow and full of unexpected hurdles, we should keep in mind that our efforts can lead and indeed already have led to outcomes that will ultimately make the LIBOR transition at the end of 2021 a smooth one. 17