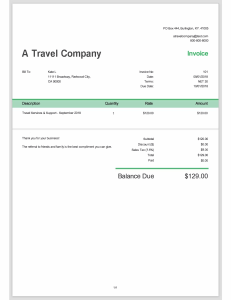

COM3703 PORTFOLIO EXAM 2022 NAME AND SURNAME: REBECCA DELISILE MOKOENA STUDENT NUMBER: 65127072 DUE DATE: 17 OCTOBER 2022 SEMESTER 2 SN Table of Contents Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA SEMIOTICS 1 2.1 Television programme 1 2.1.1 The title of the series 1 2.1.2 The names of the main characters that appear in the episode 1 2.1.3 The basic plotline of the episode 1 2.2 The four kinds of signs 2 2.3 Code 3 2.3.1 What a “code” entails in the context of communication and semiotics 3 2.4 Typology of communication codes 3 2.4.1 The seven types of codes identified by Fiske 3 2.4.2 Five codes from the chosen television programme 7 3 TEXTUAL ANALYSIS: NARRATIVE AND ARGUMENT 8 3.1 The concept of genre, and how it relates to narrative 8 3.2 The concept of argumentation and its three characteristics 9 3.3 Newspaper article 10 3.3.1 The three kinds of rhetorical practice 10 3.3.2 Example of each of the three rhetorical practices discussed found in the chosen article 11 3.3.3 The three modes of persuasion 12 3.3.4 Example of each of the three modes of persuasion found in the chosen article 13 4 FILM THEORY AND CRITICISM 13 4.1 The film: an overview 13 4.2 Theoretical discussion 14 4.2.1 The five characteristics of Strinati 14 4.2.2 A discussion of the work of the following theorists: 14 Jean Baudrillard 14 Frederic Jameson 14 Jean-François Lyotard 14 4.3 A postmodern analysis of the chosen film 15 5 QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEYS IN MEDIA RESEARCH 16 5.1 Formulating a research question 16 5.2 The target population and the accessible population 17 5.3 Sampling method: Probability or Non-probability sampling 17 5.4 Type of questionnaire survey 17 5.4.1 The type of questionnaire survey that would best suit the given scenario 17 5.4.2 Other type of survey that would also be appropriate 18 5.5 Formulating different questions 18 5.5.1 Formulating two open-ended questions 18 5.5.2 Formulating a multiple-choice, or checklist question 18 5.5.3 Formulating a contingency question 18 5.5.4 Formulating a rank-order question 18 5.5.5 Formulating a Likert-type scale question 19 5.5.6 Formulating a matrix question 19 5.5.7 Formulating a semantic differential scale question 19 6 CONCLUSION 20 7 SELF-ASSESSMENT AND SELF-REFLECTION 21 SOURCES CONSULTED 22 1. INTRODUCTION The following portfolio will provide definitions, concepts, discussions, and elaborations under the following themes: Communication and media semiotics, Textual analysis: narrative and argument, film theory and criticism, and questionnaire surveys in media research. A television series (Queen Sugar) will be selected and information about will be provided. Four kinds of signs based on the relationship between the signifier and the referent will be discussed. Information about what “code” entails in the context of communication and semiotics will be provided, the seven types of codes identified by Fiske will be identified and discussed. The concept of genre, and how it relates to narrative will be explained. Also, a newspaper article will be selected, and the three kinds of rhetorical practice will be identified, providing examples from the article. The three modes of persuasion will also be explained. A film of my own choice that I feel will easily support and demonstrate a clear postmodern perspective will be selected. An overview of the film will be provided and discuss the five characteristics of Strinati. Additionally, the work of Jean Baudrillard, Frederic Jameson, and Jean-François Lyotard will be elaborated. A postmodern analysis of the film I selected will be discussed and explained. Lastly, a scenario will be given and I will formulate various questions based on the given scenario. 2. COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA SEMIOTICS 2.1 Television programme 2.1.1 The title of the series Queen Sugar 2.1.2 The names of the main characters that appear in the episode Nova Bordelon, Ralph Angel Bordelon, Hollywood Desonier, Micah West, Violet Badelon, Charley Bordelon West, Blue Bordelon, Davis West, and Darla Bordelon (Queen Sugar full Cast and Crew). 2.1.3 The basic plotline of the episode After her father suffers a stroke, a savvy wife and manager of a professional basketball player who lives a luxurious Los Angeles lifestyle goes to her family farm in Louisiana. 1 2.2 The four kinds of signs Arbitrary signs A linguistic symbol, such as a word, serves as the greatest illustration of an arbitrary sign (Fourie 2018: 51-52). The signifier (symbol) and the referent in this instance are unrelated. The letter D-O-G (the word "dog") does not resemble a genuine dog at all (Fourie 2018: 51-52). Users of that language must consent to give the sign D-O-G a certain meaning in order to comprehend it; they must also acquire the meaning of the word (Fourie 2018: 51-52). The sign D-O-G will have no meaning to a Frenchman; unless he is familiar with the English sign system, he will not naturally attach the same meaning to it as an English speaker would (Fourie 2018: 51-52). Iconic Signs Pictorial or visual pictures are the best kind of iconic signs (paintings, film images, photography, and the like) (Fourie 2018: 52). In this case, the signifier (symbol) corresponds visually with the referent (the thing it refers to) (Fourie 2018: 52). A dog appears like a dog in a picture, on television, or on a sign (Fourie 2018: 52). The sign can be read without any additional training because it is instantly recognisable (Fourie 2018: 52). The iconic sign will have the same literal (denotative) meaning to speakers of all languages (Fourie 2018: 52). It is conceivable for the recipient to mistake an iconic sign for the real thing because of how closely an iconic sign resembles its referent, especially in cinema and television (Fourie 2018: 52). This could account for the influence of television and movies (Fourie 2018: 52). People accept television news more readily than press releases, giving the proverb "seeing is believing" new meaning (Fourie 2018: 52). For example, in the selected television programme, the house in which the family lives in on the farm is an iconic sign because it is instantly recognisable. Symbolic signs The sign (signifier) and its referent have no external correspondence or correlation, much like in language (Fourie 2018: 52). The same holds true for literary and linguistic symbols as it does for pictorial ones. Many people associate Christianity with images of crosses, whereas images of danger with images of skulls (Fourie 2018: 52). From where do these meanings come? (Fourie 2018: 52) The meanings of symbols are set by culture, and people who are a member of that culture absorb these meanings, is the response (Fourie 2018: 52). 2 Indexical signs There is a causal (cause-and-effect) relationship between the sign and its referent in the case of indexical signs (Fourie 2018: 52). The best examples are those seen in nature: clouds indicate rain, smoke indicates fire, and thunder indicates a storm (Fourie 2018: 52). 2.3 Code 2.3.1 What a “code” entails in the context of communication and semiotics A code is the "recipe" or technique by which signs are put together to convey meaning (Fourie 2018: 57). Examples of codes include the grammar we use in our everyday written or spoken linguistic formulations, the rhetorical devices used in public discourse (Fourie 2018: 57), the camera and editing methods used in film and television, and all the codes used in printing, designing, architecture (Fourie 2018:57), theatre, poetry, prose, music, and other forms of culture (Fourie 2018: 57). Not only does the link between a signifier and a signified and the raw material of signs serve as the basis for meaning, but also the relationships between different signs (Fourie 2018: 58). Codes determine and direct how signs interact with one another (Fourie 2018: 58). Therefore, a code is a collection of indications and the instructions for using them (Fourie 2018: 58). This involves researching the ways in which different sign systems are related to one another and how signs are related to one another using codes that users can comprehend (Fourie 2018: 41). For instance, how do grammatical sentence structures (codes) in a language relate words (verbal signs) to one another to generate sentences? (Fourie 2018: 41) How can the usage of the camera and editing procedures (codes) relate the words (for instance, the conversation in a film) and visuals of a film to one another? (Fourie 2018: 41) How do these codes emerge, and what part do culture and cultural norms play in their development, application, and understanding? (Fourie 2018: 41). 2.4 Typology of communication codes 2.4.1 The seven types of codes identified by Fiske The seven types of codes identified by Fiske are, codes of behaviour, signifying codes, analogue and digital codes, presentational and representational codes, elaborated and restricted codes, logical, aesthetic, and social codes, and codes of content and codes of form (Fourie 2018: 58-61). 3 Codes of behaviour Nearly all facets of our social behaviour are codified (Fourie 2018: 58). Behavioural codes control actions like table manners, how we dress for different occasions, how we behave at social gatherings, how we treat our superiors and inferiors, how we obey traffic signs, how we form an orderly line at the bus stop or the box office, how we act at sports events like soccer or tennis, at concerts like pop concerts, at weddings, funerals, or in the church, and so on (Fourie 2018: 58). Such behaviour is governed by what we refer to as codes of behaviour, which are the outcome of cultural traditions and customs as well as the dominant norms and values in a society (Fourie 2018: 58). These are transmitted from one generation to the next, but they are altered over time in response to alterations in politics, the economy, society, and culture (Fourie 2018: 58). In a society, we all agree to follow specific rules of behaviour in particular social contexts. Without these rules of conduct, society would be in disarray (Fourie 2018: 58). Internal policies and codes of conduct in the media can be viewed as codes of conduct - "the way things are done" at a particular newspaper, radio station, television network, etc. (Fourie 2018:59). Signifying codes Contrarily, indicating codes are codes that are unique to a particular sign system, such as grammar codes for languages, camera (Fourie 2018: 58), and editing codes for electronic and digital visual communication (film, television, the internet, etc.) (Fourie 2018: 58). These codes have a specific meaning that they are designed to convey in order to perform a specific communication function (Fourie 2018: 59). The editing techniques of fade, dissolve, and cut in cinema and television are examples of signifying codes; each has its own quality and meaning and can offer a certain meaning to a scene, depending on how it is used by the communicator (Fourie 2018:59). Another illustration of a coding system is the tenses in a grammatical system (Fourie 2018: 59). Each language has a different way of using tenses (Fourie 2018:59). Tenses have definite meanings, and when they are used improperly, they cause grammatical confusion (Fourie 2018: 59). Analogue and digital codes Comparing a digital watch to an analogue watch provides the clearest explanation of how a digital code works (Fourie 2018: 59). A conventional watch does not indicate each second and minute, however a digital watch tells the seconds and minutes one by one (Fourie 2018: 59). 4 Digital codes, like digital watches, have significant differences. The difference between the signifier and the signified applies to digital codes (Fourie 2018: 59). Language is a useful illustration of digital codes because there is a definite separation between sign and meaning (Fourie 2018: 59). Arbitrary codes are easy to record because they are digital and based on convention, consent, and agreement (like music and mathematics) (Fourie 2018: 59). On the other side, the dance is an illustration of an analogue code (Fourie 2018: 59). The motions, posture, and distance that make up the dance are always changing, making it more challenging to capture them on film (Fourie 2018: 59). Nature, which changes continuously without human intervention, is an analogue code, whereas civilization is primarily a digital code (Fourie 2018: 59). Presentational and representational codes The distinction between presentational and representational codes is another crucial one. Texts (such as a book, a play, a comic strip, an internet site, a newspaper article, a television programme, a movie, a radio programme, a legal document, etc.) can be thought of as intrinsically representational codes (Fourie 2018: 59). They represent something else; they were made to serve a particular function, to express something, to make a comment about something, or to express something. Iconic and symbolic codes serve as representations of things (Fourie 2018: 59). Presentational codes, on the other hand, are tied to the communicator's current social setting and work within and for the thing itself (Fourie 2018: 59). Indexical presentational codes are used (Fourie 2018: 60). A good example of a presentational code is nonverbal communication, which is dependent on gestures, eye movements, vocal tonality, and other factors (Fourie 2018: 60). Presentational codes also function in the present (the here and now), with the goal of regulating and guiding interaction (Fourie 2018: 60). For instance, my voice inflection or facial expression may indicate how I feel right now about something, but they are unable to convey how I felt last week (Fourie 2018: 60). Presentational codes are only permitted during face-to-face interactions or when the communicator is physically present (Fourie 2018: 60). Elaborated and restricted codes We can also tell limited codes apart from elaborate ones (Fourie 2018: 60). People from lower socioeconomic groups have been reported to have more restricted linguistic skills (vocabulary, powers of expression, and comprehension) than those from higher socioeconomic classes 5 (although exceptions will always be found) (Fourie 2018: 60). This could be attributed to social and educational factors (Fourie 2018: 60). The first group is seen as having a limited language code, while the second group is thought to have an extended language code. It is possible to apply this distinction to practically all social phenomena (Fourie 2018: 60). It is mostly used in semiotics to distinguish between the restricted codes of various organisations, occupations, bodies, and individuals and to explain how these codes affect meaning (Fourie 2018: 60). For instance, a restricted code would be the norms followed by a subculture like skinheads (Fourie 2018: 60). The same is true for the legal profession; if a person is unfamiliar with the laws and rules (limited code) that regulate court proceedings, they are not allowed to practise law (Fourie 2018: 60). The restrained codes of the army, parliament, and media with its behaviour norms, the medical and health care professions, and other institutions are no different (Fourie 2018: 60). Investigating restricted codes' precise nature will help us understand how they affect the way these organisations and individuals behave as well as the meaning and content of their communications (Fourie 2018: 60). One may also argue that apartheid was a limited social code with its own laws, norms, and regulations and that South African society has tended to operate under more comprehensive codes following apartheid's demise, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Fourie 2018: 60). Logical, aesthetic, and social codes The alphabet, mathematics, Morse code, and road signs are some of the best examples of these three types of codes (Fourie 2018: 61); Theatre, opera, prose, poetry, fine art, sculpture, architecture, television, film, and radio are some examples of aesthetic codes (art and symbolic means of expression such as the media) (Fourie 2018: 61); Social codes (society) include things like dress, food and cooking, objects, social behaviour, customs, sports, furnishings, and games (Fourie 2018: 61). These codes don't appear on their own (Fourie 2018: 61). For instance, the media do not just represent an aesthetic code; they also usually represent a social code and a logical one (Fourie 6 2018: 61). The media are thought to operate and function primarily in terms of an aesthetic code since their portrayal of the world involves a planned and structured creative process (Fourie 2018: 61). Codes of content and codes of form All of the following codes, which may be either codes of content or codes of form or both, are included in the distinction between codes of content and codes of form (Fourie 2018: 61). By using examples from the visual media, it is simple to illustrate the difference between codes of content and codes of form (Fourie 2018: 61). The methods used to connect an image's parts so that they can convey meaning together may be referred to as codes of content (Fourie 2018: 61). These include elements like composition (the image's levels and lines), colour scheme, wardrobe, the performers and their acting styles, and image elements like people, furniture, props, scenery, buildings, and streets (Fourie 2018: 61). These are all examples of codes of content (Fourie 2018: 61). Codes of form, on the other hand, are the elements related to how the camera views the content and how the different shots are edited together. Consider a battle scene from a movie or television drama as an illustration (Fourie 2018: 61). The director plans the shot sequence before the "shoot," which is the recording of the shot on film (Fourie 2018: 61). For instance, he or she can choose to set up the players on horses with a hill in the background (Fourie 2018: 61). They would be dressed in uniforms, and there would be a wide range of characters, hues, sounds, trees, weapons, and other elements typical of a war scenario (Fourie 2018: 62). The hero would come into focus in a single shot (Fourie 2018: 62). The injured hero would be seen falling from his horse in the following shot (Fourie 2018: 62). The horse would then fall on top of the hero in the scene after that, and so on (Fourie 2018: 62). These are all examples of content codes. These codes could be behavioural, artistic, or logical (Fourie 2018: 62). 2.4.2 Five codes from the chosen television programme 1. Logical, aesthetic and social codes The programme is related to aesthetic code, for instance, drama, opera, prose, poetry, fine art, sculpture, architecture, television, film, radio (Fourie 2018: 61). 7 2. Codes of content and codes of form The programme is related to codes of content and codes of form in the sense that the techniques that are used to unite the components of an image to enable them to convey meaning jointly may be described as codes of content (Fourie 2018: 61). These include aspects such as composition (levels and lines in the image), the combination of colours, costume, the actors and their acting techniques, and objects in the image, such as people, furniture, props, scenery, buildings, and streets (Fourie 2018: 61). 3. Presentational and representational codes The programme is related to Presentational and representational codes due to the fact that Texts (a newspaper article, a television programme, film, a radio programme, a legal document, a novel, a play (Fourie 2018: 59), a cartoon strip, internet site, and so on) may be considered to be inherently representational codes (Fourie 2018: 58). 4. Signifying codes The programme is related to this code because, In contrast, signifying codes are codes that are specific to specific sign systems, such as codes of grammar in language and camera and editing codes in electronic and digital visual communication (film, television, the internet, etc.) (Fourie 2018: 58). 5. Codes of behaviour Almost every aspect of human social behaviour has been legislated (Fourie 2018:58). 3. TEXTUAL ANALYSIS: NARRATIVE AND ARGUMENT 3.1 The concept of genre, and how it relates to narrative As a classification that informs the audience of the texts' nature, genres relate to several "kinds" of writings (Prinsloo 2018: 242). It has been said that certain media genres negotiate certain sets of prevailing conflicts (Prinsloo 2018: 242). The prevalence of specific unsettling situations in a given period and place can be connected to the ups and downs in popularity of certain genres (Prinsloo 2018: 242). It might be claimed that the fact that there were so many films about Vietnam produced in the US after the war is a response to the need of US citizens to symbolically engage with the tension of their powerful country fighting and losing a war (Prinsloo 2018: 242). There have been a number of media products in South 8 Africa, including novels, TV series, and films, that deal with the history of South African apartheid with racial opposition as the primary theme (Prinsloo 2018: 242). Similar to this, other South African films discuss the issue of law and order, which is typically the subject of crime fiction and gangster movies, in connection to a modern South African setting (Prinsloo 2018: 242). We can predict specific generic conventions when we use storey theories. These act as guidelines to ensure consistency in the media texts' treatment of the contested issues while maintaining just enough variation to keep things exciting and novel (Prinsloo 2018: 242). It's important to become familiar with the genre-specific conventions and how the narrative is organised (Prinsloo 2018: 243). It also makes it possible to spot instances of genre transgression because no genre is ever static (Prinsloo 2018: 244). 3.2 The concept of argumentation and its three characteristics The verbal and social activity of reason known as argumentation is described as "increasing (or decreasing) the acceptability of a controversial standpoint for the listener or reader by putting forward a constellation of propositions intended to justify (or refute) the standpoint before a rational judge." (Prinsloo 2018: 244) Three characteristics of argumentation are noted in light of this definition (Prinsloo 2018: 244): It is an active process since it seeks to alter or modify an existing situation or behaviour in some way (Prinsloo 2018: 244). It is a social practise since it involves communication in an effort to put an end to a disagreement or persuade the listener to share an opinion (Prinsloo 2018: 244). It is a collaborative effort since persuasion can only succeed if the audience is receptive to the argument (Prinsloo 2018: 244). 9 3.3 Newspaper article Source: BREAKING NEWS LIVE | Gauteng police station robbed of 10 guns by men pretending to report hijacking | News24 3.3.1 The three kinds of rhetorical practice The three kinds of rhetorical practice are forensic, epideictic (or demonstrative) and deliberative (Prinsloo 2018: 244). Forensic Prinsloo (2018: 244) states that Forensic (or judicial) argument emphasises prior behaviour and, as the name implies, is similar to the procedures used in a court of law (Prinsloo 2018: 244). It typically focuses on issues of justice and injustice and either aims to defend or condemn someone (such as a political figure) (Prinsloo 2018: 244). The listener is intended to be biased to the position and person it is criticising or defending through the major focus on proof and the study of facts (Prinsloo 2018: 245). 10 Epideictic Dixon also refers to an epideictic argument as a "demonstrative" argument. He mentions that it came from public rites that either glorified gods or men (Prinsloo 2018: 245). It evolved to include affirmation or defence in addition to criticism or denunciation. It concentrates on the personality or reputation of the subject(s) and makes an effort to influence the audience to either like and accept the subject(s) for their virtue or to despise and reject them for their dishonour (Prinsloo 2018: 245). Deliberative Argumentative deliberation includes weighing the merits or otherwise of potential future courses of action (Prinsloo 2018: 245). It aims to persuade or deter the audience from taking a particular action in the future. News coverage of the American presidential election campaigns and the arguments put forth to persuade voters about the direction of their vote would be a clear example (Prinsloo 2018: 245). Deliberative argument can also be seen in advertisements that aim to persuade students to enrol at their institution or in investigative journalism that examines a local government issue in an effort to hold the power base accountable and elicit a response from the audience (Prinsloo 2018: 245). In Aristotle's words: "If he [for there is no doubt that women had no place in public life at the time Aristotle was writing] urges its acceptance, he does so on the grounds it will do good; if he urges its rejection, he does so on the grounds it will do harm." (Prinsloo 2018: 245). The argument seeks to induce or dissuade the reader (Prinsloo 2018: 245). 3.3.2 Example of each of the three rhetorical practices discussed found in the chosen article Forensic From the article an example of forensic is, The National Police Spokesperson (News24), who can also be a substitute of a political leader. Epideictic An example of Epideictic from the article is, the three suspects that hijacked the policemen. This article focuses on the character or reputation of the persons that were involved in the incident to persuade the audience to dislike them. 11 Deliberative An example would be the suspects being arrested, because in future that is what the audience is anticipating. 3.3.3 The three modes of persuasion The three modes of persuasion are, ethos, pathos, and logos, with each relating to a different point of the rhetorical triangle (Prinsloo 2018: 246). An ethotic argument makes reference to the speaker's personality and qualities (Prinsloo 2018: 246). When both sides of an argument are reasonably persuasive, it is effective to employ an appeal to the speaker's ethos (Prinsloo 2018: 246). This works well when the speaker has personal experience that persuades the audience or when their reliability is taken for granted. As a result, certain individuals in South Africa give weight to a certain argument (Prinsloo 2018: 246). Examples include Archbishop Desmond Tutu and former president Nelson Mandela, whose prominence as moral leaders gives some weight to the arguments they support (Prinsloo 2018: 246). Similar newspaper efforts, like the Daily Sun's "I am a man" ad from 2007, used a variety of celebrities to support the campaign against violent abuse of women, with the justification that if they are supporting it, it must be worthwhile and trustworthy (Prinsloo 2018: 246). Additionally, journalists use this method of justification by using "research" and "studies" as evidence of the validity of their claims and by referencing sources' authority by calling them "Professor," etc (Prinsloo 2018: 246). When a subject is utterly unrelated to the academic's field of expertise, such as Egyptology, Richardson says that people may look to Professor X's viewpoint for advice regarding, say, the advantages of privatisation (Prinsloo 2018: 246). A pathotic argument aims to influence the audience's attitude (Prinsloo 2018: 246). As the arguer attempts to get people into the kind of mindset that will make them receptive to the line of argument, they can be led to pity, fear, indignation, or even guilt through pathos or an appeal to emotion (Prinsloo 2018: 246). The creation of a group of individuals as undeserving and the justification of severe treatment of these people are examples of pathotic arguments (Prinsloo 2018: 247). There are many xenophobic examples, but one of the most horrifying would be the radio broadcast in Rwanda during the 1990s genocide that described Hutus as bugs worthy of being crushed underfoot (Prinsloo 2018: 247). Similar to this, feelings of love, pity, etc. can influence a crowd to act in novel ways (Prinsloo 2018: 247). The arguer can attempt to put the audience in a receptive frame of mind to engage with the argument bycomplimenting them as 12 reasonable and intelligent as well (Prinsloo 2018: 247). It is common to utilise appeals to patriotism and national loyalty to demand certain actions. Consider the catchphrase from World War I, "Your nation needs you." (Prinsloo 2018: 247). The stated logic or proof is a requirement for the logetic argument. Both inductive and deductive reasoning are used in an appeal to logos (Prinsloo 2018: 247). A claim is made in a logical argument by stating a number of statements (Prinsloo 2018: 247). A reasonable inference can be drawn from these assertions, such as the fact that All South African sporting organisations are racist (Prinsloo 2018: 247). A sports body exists for rugby (Prinsloo 2018: 247). Rugby's governing body is racist. (Prinsloo 2018: 247). 3.3.4 Example of each of the three modes of persuasion found in the chosen article Ethotic For example, News24 as the online newspaper that provides national news. Pathotic For example, the article talks about how three men walked into a police station pretending to report a case and ended up hijacking the police station. Through pathos or an appeal to emotion they can be moved to pity, fear, anger, even guilt as the arguer tries to get them into the kind of mind-set that will make them open to the line of argument. 4. FILM THEORY AND CRITICISM 4.1 The film: an overview The title of the film I Saw the Devil The name of the director Kim Jee-woon (Wikipedia 2022) 13 The names of the main characters Kim Soo-Hyun, Jang Kyung-chul, Jang Joo-yun, Squad Chief Jang, Jang Se-Yun, Tae-Joo, and Junior (Wikipedia 2022). Two themes from the film Action and Thriller 4.2 Theoretical discussion 4.2.1 The five characteristics of Strinati 1. With the prominence and influence of the mass media and popular culture expanding, there is a blurring of the line between culture and society (Wigson 2018: 297). All types of social interactions are governed and affected by the media, and mediated cultural representations influence how we view the world (Wigson 2018: 297). 2. As we consume visual and performing arts rather than engaging with written works where we are obliged to think about and ponder over the material, there is an emphasis on style over substance (Wigson 2018: 298). 3. The line between high art and popular culture is blurring as a result of the media's acceptance of both as one (Wigson 2018: 298). 4. Global communication technology, economics, and politics have caused a mismatch between time and space (Wigson 2018: 298). 5. Metanarratives that no longer have relevance in contemporary society, such as Marxism and Christianity, are in decline (Wigson 2018: 298). 4.2.2 A discussion of the work of the following theorists: Jean Baudrillard The work of French cultural theorist, sociologist, and philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007), who was a professor at the Université de Paris-IX Dauphine, is arguably the best example of postmodernism (Wigson 2018: 298). Due to the obscurity and complexity of many of his publications, Baudrillard has a reputation for being contentious (Wigson 2018: 298). For 14 instance, Baudrillard asserts that Disneyland represents the true America, which seems ludicrous (Wigson 2018: 298). He makes the case that postmodern cultures have entered an era of simulation, namely a third-order simulation, as a result of their saturation with media and information technology (Wigson 2018: 298). Frederic Jameson The barrier between high and commercial art forms has been steadily eroding, according to Frederic Jameson (1934-), a Marxist political theorist at Duke University and an American literary critic (Wigson 2018: 299). Eventually, he claims, it will be difficult to discern between the two (Wigson 2018: 299). According to Jameson, it is difficult for an individual style to persist in postmodern society because all styles are shaped by the demands of globalism, consumerism, and capitalism (Wigson 2018: 299). The idea of pastiche and how it varies from parody is crucial to Jameson's theory on the loss of identity (Wigson 2018: 299). Jean-François Lyotard Unlike Baudrillard and Jameson, Jean-François Lyotard (1924–1998), a French philosopher and literary theorist best known for his formulation of postmodernism, believes that the delegitimization of scientific knowledge, not the forces of capitalism, is what is responsible for the decline of high art (Wigson 2018: 300). According to Lyotard, just as postmodernism attacked great art forms, the demise of metanarratives poses a direct challenge to scientific reality (Wigson 2018: 300). A metanarrative is an all-encompassing storey that serves to clarify or make a judgement about the truthfulness of all other stories (Denning 2004) in (Wigson 2018: 300). It is a set of universal and unalterable truths that transcends societal, institutional, and human boundaries (Wigson 2018: 300). This basically indicates that a small-scale study's findings or a person's actions only have meaning when they reflect or support a larger metanarrative, like the quest for justice and truth (Wigson 2018: 300). 4.3 A postmodern analysis of the chosen film It is sometimes referred to as the "3-minute culture" or the culture of the short attention span (Wigson 2018: 302). In this culture, politicians speak to us in 30- second "sound bites" and in "photo opportunities" rather than in speeches (Wigson 2018: 302). It is a culture that encourages us to flit back and forth between TV stations whenever our boredom threshold is reached rather than enjoying a show (Wigson 2018: 302). It is a culture where people rarely 15 focus on doing one thing at a time for an extended period of time; rather, it is a society that caters to those who have short attention spans (Wigson 2018: 302). Postmodernism is troublesome in many respects because of its nebulous character. In that it can be challenging to discern any storey in a postmodern book, postmodern narrative is also frequently conflicting (Wigson 2018: 305). We are trying to analyse postmodern narrative using structuralist techniques because that is all we have available right now, which leads to this paradoxical predicament (Wigson 2018: 305). So, the question of whether we can benchmark postmodern narratives using structuralist tools emerges (Wigson 2018: 305). So, what use does storey theory offer for us as mass communication academics? (Wigson 2018: 306). The importance of the research tool that narrative analysis offers should not be undervalued (Wigson 2018: 306). The themes in the media, especially in film and television, are deeply rooted in the culture that produced them (Wigson 2018: 306). Since every genre—from the news report to the accompanying advertisements—basically tells a storey, it is clear that these genres are all narrative in character (Wigson 2018: 306). Only the world that develops and uses narrative can give it significance. Popular culture, as shown on television, appears to be more rigorously planned and conventional than great art (Wigson 2018: 306). Even television shows that don't explicitly use any aspects of Propp's or Eco's models still have a recognisable structure (Wigson 2018: 306). In each episode of the Star Trek television series, for instance, the USS Enterprise will run into some kind of extra-terrestrial life, crew members will become separated from the ship, a crew member will fall in love, and either the ship or the crew will be in danger (Wigson 2018: 306). According to Kozloff (1987:49) in (Wigson 2018: 306), the predictability of television has diminished one of the main elements that propel narrative, suspense (Wigson 2018: 306). The audience should be intrigued by the several possibilities that each incident in the storey should present (Wigson 2018:306). 5. QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEYS IN MEDIA RESEARCH 5.1 Formulating a research question How can the community get the message in order to stop drinking and driving? 16 5.2 The target population and the accessible population Target population The overall group or segment of society that we are interested in is referred to as the target population (Bornman 2018: 435). The target population in this case is all the adults, who drive, in the community of QwaQwa in the Free State province in South Africa. Accessible population The segment of the population to which we have access in order to sample is referred to as the accessible population (Bornman 2018: 435). The accessible population is all the members of the public whose names appear on the address list. 5.3 Sampling method: Probability or Non-probability sampling The sampling method I will use is the probability sampling. This is because, in most circumstances, probability samples are preferable to and superior to non-probability samples (Bornman 2018: 438). First off, probability sampling eliminates any conscious or unconscious bias that a researcher or fieldworker might have when choosing respondents (Bornman 2018: 438). As a result, the likelihood of producing a sample that is accurately representative of the population is higher (Bornman 2018: 438). Additionally, probability sampling gives the researcher the capacity to analyse the data with advanced statistical methods and extrapolate the results to the entire population (Bornman 2018: 438). There are several methods for creating a probability sample (Bornman 2018: 438). 5.4 Type of questionnaire survey 5.4.1 The type of questionnaire survey that would best suit the given scenario Self-administered surveys. These are suitable for the given scenario because, they are the cheapest and most straightforward method of doing surveys is by far self-administered surveys (Bornman 2018: 449). Self-administered surveys can be carried out by a single researcher because they are also quite easy to set up (Bornman 2018: 449). Typically, these factors are significant for university professors and students with little financial resources (Bornman 2018: 449). For populations with high levels of education and a keen interest in the subject of a survey, response rates may also be high (Bornman 2018: 449). Additionally, participants in selfadministered surveys might be more receptive to answering questions about delicate subjects than they are during interviews (Bornman 2018: 449). 17 5.4.2 Other type of survey that would also be appropriate New technological developments and survey interviewing (Bornman 2018: 456). Numerous recent technology innovations that have an impact on people's lives have also created new opportunities for survey research (Bornman 2018: 456). Particularly recent advancements in computer technology are simplifying both the job of interviewers and, in the case of self-administered surveys, the filling of questionnaires (Bornman 2018: 456). 5.5 Formulating different questions 5.5.1 Formulating two open-ended questions 1. What are the alcohol suppliers’ thoughts on the current situation? 2. How can the campaign address alcohol suppliers to help stop the death toll due to drinking and driving? 5.5.2 Formulating a multiple-choice, or checklist question Should the campaign address alcohol suppliers? (Use an X to answer if it yes or no) YES NO RESPONSE/COMMENT 5.5.3 Formulating a contingency question Does your family subscribe to the initiative placed by the councillor? Yes 1 No 2 If you answered ‘Yes’ to question 1, please skip question 2 and move to question 3. If you answered ‘No’, please answer question 2. 5.5.4 Formulating a rank-order question Here is a list of various timeslots that companies or business within the community can stop selling alcohol. Please rank them in order of your preference. Put an X next to the time slot that you like the best that you like the second best, and so on. _______ 20:30 PM _______ 21:30 PM _______ 22:00 PM 18 5.5.5 Formulating a Likert-type scale question Should drivers not be allowed to drink while driving? and if caught, they will be arrested. Put an X as your answer Strongly agree -------------------Agree ---------------Neither agree nor disagree ------------------- 5.5.6 Formulating a matrix question Indicate to what extent you agree or disagree with the following statements regarding the high accident rate in Free State: Disagree Partially disagree Agree Partially Agree 5.5.7 Formulating a semantic differential scale question Bad Good Unpleasant Pleasant Dull Sharp Polite Rude 19 6. CONCLUSION The portfolio provided definitions, concepts, discussions, and elaborations under the following themes: Communication and media semiotics, Textual analysis: narrative and argument, film theory and criticism, and questionnaire surveys in media research. A television series (Queen Sugar) was selected and information about it was provided. Four kinds of signs based on the relationship between the signifier and the referent were discussed. Information about what “code” entails in the context of communication and semiotics were provided, the seven types of codes identified by Fiske were also identified and discussed. The concept of genre, and how it relates to narrative was explained. Also, a newspaper article was selected, and the three kinds of rhetorical practice were identified, providing examples from the article. The three modes of persuasion was also explained. A film of my own choice that I feel will easily support and demonstrate a clear postmodern perspective was selected. An overview of the film provided and discussed the five characteristics of Strinati. Additionally, the work of Jean Baudrillard, Frederic Jameson, and Jean- François Lyotard will be elaborated. A postmodern analysis of the film I selected was discussed and explained. Lastly, a scenario was given, and I formulated various questions based on the given scenario. 20 7. SELF-ASSESSMENT AND SELF-REFLECTION I have learnt that having knowledge about the representation of Africa in western media, in this respect I have learnt some important topics within the media content. I am now able to conduct independent desktop research, able to compile relevant data together meaningfully and this assignment has put discipline and commitment in me as I had to focus on it. I think I could use focus, discipline and commitment in future life and work environment and the research abilities I have gained could be useful in the work environment. Time-management proved to be one of my shortcomings while doing this assignment. In future I need to properly manage my time when doing any project. To the greater extent I have achieved the learning outcomes of this assignment. These are: Discussing the concepts of international news, Africa in western media, news-related factors influencing global flow of news, theories describing the international flow of news, and how global news agencies influence the content of international news. 21 SOURCES CONSULTED Bornman, E. 2018. Measuring Media Audiences, in Media Studies. Volume 3: Media content and media audiences, edited by PJ Fourie. Cape Town: Juta. Fourie. P, J. 2018. Communication and Media Semiotics, in Media Studies. Volume 3: Media content and media audiences, edited by PJ Fourie. Cape Town: Juta. Media studies: media content and media audiences. Only study guide COM303A for COM3703, edited by J Reid & M van Heerden. Pretoria: University of South Africa. Queen Sugar full Cast and Crew (2016-2022). IMBd Pro. [O]. Available: Queen Sugar (TV Series 2016–2022) - Full Cast & Crew - IMDb Accessed on 5/10/2022 Wikipedia 2022. I Saw the Devil. The free Encyclopedia. [O]. Available: I Saw the Devil - Wikipedia Accessed on 6/10/2022 Wigson, D. 2018. Narrative analysis in Media Studies. Volume 3: Media content and media audiences, edited by PJ Fourie. Cape Town: Juta. 22