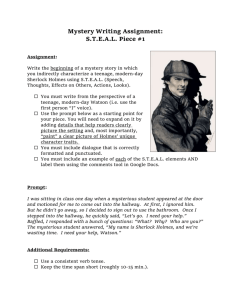

Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Empty House Excerpt

advertisement