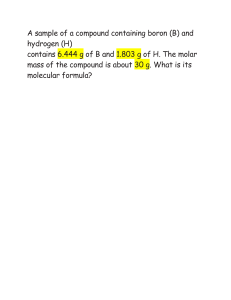

Microbial Transformation of 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid yields: Potent Inhibitors Urease; In-vitro and In-silco studies Abstract Biological structural modification of natural metabolites (products) becomes an important, and worthy approach to diverse pharmacological properties. The current study focuses on the structural modification of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid that was carried out by using Macrophomina phaseolina and Cunninghamella blakesleeana. Microbial bio-transformation of compound 1 with M. phaseolina yielded metabolites 2-6, while metabolites 7 and 8 were obtained with C. blakesleeana. Among them, two metabolites 5 and 6 were found to be new metabolites. Furthermore, all the yielded metabolites were subjected to test their inhibitory potential against urease, which is a key agent in causing different gastric ulcers and other nephropathies. Among the metabolites, compound 1 was found to be potent active (IC50 =13.2 ± 0.9 µM), followed by compounds 7 (IC50 = 22.4 ± 1.13 µM), 4 (IC50 = 23.8 ± 0.64 µM), and 5 (IC50 25.8 ± 0.78 µM). While compound 2 was found to be moderate active (IC50 = 38.6 ± 2.3 µM). Compounds 3, 6, and 8 were found inactive. Acetohydroxamic acid (IC50 = 20.3 ± 0.43 µM) was used as a reference compound in this study. Keywords Biotransformation; 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid; Macrophomina phaseolina KUCC 730; Cunninghamella blakesleeana ATCC 8688A; Urease Inhibition; Gastric Ulcers; 1 Introduction Plant s' derive secondary metabolites have been one of the common sources of drug discovery. Due to the number of limitations associated with the plant natural products i.e. toxicity to normal cells, solubility, and so on, these products are usually modified based on the structure-activity relationship in delivering candidates to the clinic trial [1,2]. Microorganisms exist with a high magnitude of biodiversity than plants, and offers exceptional metabolic adaptability [3]. Therefore, microorganisms with such structural modification capacities will embark on the biotechnology boom especially in drug development and large-scale production. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid/Enoxolone (GA) (1), is a pentacyclic triterpene, is one of the most important bioactive components of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Fabaceae) [4-6]. GA (1) is well known for its biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, 1 and anti-allergic properties [7-9]. Previously, Li, Kun et al. and his co-worker chemical synthesize a number of derivatives of GA (1) with potent anti-cancer activities [10]. Biotransformation or microbial based transformation is one of the method of choice for structural modifications of compounds having complex skeleton because reactions are highly regio- and stereo-selective with environmentally friendly conditions [11]. Biocatalytic conversions can be achieved by several agents, such as enzymes, animals and plant cell cultures, and microorganisms. On the other hand, microbes are most effectively used for this purpose, as they have a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase system that catalyzes the hydroxylation at various unassailable positions of the complex skeleton [12,13]. Biotransformation on GA (1) has been earlier reported by using various biological systems, such as bacteria, and fungi [14-17]. The current study is the continuation of our research on the biotransformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid [15]. This time Macrophomina phaseolina and Cunninghamella blakesleeana were used for derivatization of compound 1. Oxidative ring cleavage, Baeyer-villager oxidation, and hydroxylation at various carbons were observed. Biotransformation of GA acid with these fungi yielded two new 5-6, and five known 2-4, and 7-8 compounds. Urease (EC 3.5.1.5) is a bi-nickel containing metallic-enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolytic decomposition of urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide, and thus enables organisms to use urea as a nitrogen source. Ureases are also had a strict influence on socioeconomic growth and environmental hardals [18-20]. The continuous labor of urease enzyme in both human and animal cells can cause multiple chronic diseases, such as urolithiasis, urinary catheter encrustation, hepatic encephalopathy, peptic, and duodenal ulcers. In view of their diverse functions, urease inhibition is considered as one of the key factors to avoid such chronic infections. Thereby, specific compounds with high efficiency and potency could provide an insight into the treatment of such chronic diseases. Thus we designed the current study to address the current enigma of urease inhibitors. 2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Fungal Strains and Media A bio-transformational study was done by using strains of M. phaseolina, obtained from Karachi University Culture Collection (KUCC), Pakistan, and C. blakesleeana (ATCC 2 8688A), which purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), USA. SDA slants were used for sufficient growth and kept at 4 ˚C. The media ingredients used for the preparation of the growing culture of M. phaseolina and C. blakesleeana are the same. For 1 L distilled water, glucose (10 g), peptone (5 g), sodium chloride (5 g), KH2PO4 (5 g), and glycerol (10.0 mL) were used. 2.2 General experimental details Substrate 1 (18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, GA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Germany). Buchi (M-560) machine was used for measuring melting points. TLC cards (PF254; 20 × 20, 0.25 mm thick) were supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Metabolites were visualized by spraying ceric sulfate on TLC cards. The separation was carried out by column chromatography on Silica gel (70-230, mesh), acquired from E. Merck. Final purification of GA metabolites was carried out by using a recycling reverse phase HPLC, fitted with the JAIGEL ODS-H-80 column. Infrared (IR), Ultraviolet (UV), and optical rotations experiments were recorded on FT-IR-8900 spectrophotometer, UV-240 spectrophotometer, Shimadzu (Tokyo, Japan), and Stuart SMP-10 (chloroform/methanol), respectively. The masses of the resulting metabolite were measured by using a JEOL JMS-600H (JEOL, Akishima, Japan) mass spectrometer, which was used for both low-resolution (EI-MS) as well as for high-resolution electron impact mass spectrometry (HREI-MS). For polar compounds, fast atomic bombardment mass spectroscopic (FAB-MS) measurements were carried out on JEOL TMS-HX110 (Japan) spectrometer, using glycerol or thioglycerol as a matrix, and KI or ScI used as an internal standard to determine the exact masses of organic compounds. Onedimensional (1H-NMR), and two-dimensional (13C-NMR, HSQC, HMBC, COSY, and NOESY) techniques were performed on Bruker Avance-Cryo probe spectrometers, by Bruker, (Zurich, Switzerland) in CD3OD or DMSO-d6. 2.3 Biotransformation of 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (1) with Macrophomina phaseolina (KUCC 730) The above-mentioned media (13 L, 500 mL in 1000 mL flasks) was sterilized and cooled at room temperature, spores of M. phaseolina were added to each flask from a seed flask. After a few days, when enough growth of fungi was observed, a clear solution of substrate 1 (2 g) in methanol was dispensed into 26 flasks. This reaction was carried out for 18 days, with continuous shaking at low temperature (26-28 ˚C) on a rotary shaker. The reaction mixture was also monitored with negative control (A reaction mix. containing media and fungi) as well as with positive control (A reaction mix. containing media and drug). After completion 3 of the reaction, a suitable solvent mainly ethyl acetate was added in it for quenching the reaction. The solution was filtered, extracted, and evaporated yielding a brown gummy material which was then fractionated by column chromatography (4% gradient EtOAc, and 10% gradient MeOH-DCM). Resulting fraction-1 (at 70% EtOAc) was purified using RP-HPLC (Mobile phase MeOH/H2O 8/2), and metabolites 2, and 6 were obtained. The fraction-2 (at 10% MeOH) was further purified by using the same solvent system on HPLC, to obtain metabolite 3-5. 2.3.1 3,4-Seco-4-hydroxy-11-oxo-18β-olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid 3,4-lactone (2) White shiny solid (80 mg). m.p.: 266-270 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : -21.9˚ (c = 0.0012). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 248 (3.6). IR (CHCl3); Vmax cm-1: 3578 (OH), 1724 (lactone), 1690 (enone), 1640 (acid). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): Table-2. 13 C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): Table-2. FAB-MS (+) m/z: 585.3 [M + H]+. HRFAB-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 585.3281 (C30H45O5, 585.3267). 2.3.2 3,4-Seco-4-hydroxy-11-oxo-18β-olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid (3) White amorphous powder (15 mg). tR: 20 min. m.p.: 289-304 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +65.1 (c = 0.0011). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 248 (3.9). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3410 (OH), 1647 (enone), 1557 (acid). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 600 MHz): Table-2. 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 150 MHz): Table-2. FAB-MS (+) m/z: 503.2 [M + H]+. HRFAB-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 503.3385 (C30H47O6, 585.3373). 2.3.3 3,4-Seco-4,7β-dihydroxy-11-oxo-18β-olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid (4) White crystalline solid (15 mg). tR: 18 min. m.p.: 296-310 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +59.7 (c = 0.0013). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 248 (3.9). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3472 (OH), 1682 (enone), 1653 (acid). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz): Table-2. 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz): Table-2. FABMS (+) m/z: 519.2 [M + H] +. HRFAB-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 519.3333 (C30H47O7, 519.3322). 2.3.4 3,4-Seco-4,15α-dihydroxy-11-oxo-18β-olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid (5) White amorphous powder (15 mg). tR: 20 min. m.p.: 258-260 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +80.6 (C = 0.0011). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 243, 248 (3.8). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3457 (OH), 1664 (enone), 1588 (acid). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz): Table-3. 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz): Table-2. FAB-MS (+) m/z: 519.1 [M + H] +. HRFAB-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 519.3335 (C30H47O7, 519.3322). 4 2.3.5 3,4-Seco-4,15α-dihydroxy-11-oxo-18β-olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid,3-methyl ester (6) White shiny solid (15 mg). tR: 18 min. m.p.: 345-350 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +62.7 (c = 0.0011). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 248 (3.9). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3446 (OH), 1735 (ester), 1701 (enone), 1650 (acid). 1H-NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz): Table-3. 13C-NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz): Table-2. FAB-MS (+) m/z: 533.4 [M + H] +. HRFAB-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 533.3498 (C31H49O7, 533.3478). 2.4 Biotransformation of 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (1) with Cunninghamella blakesleeana (ATCC 8688A) This time C. blakesleeana was used for conversion of the same substrate 1 (2.5 g). It was dissolved in acetone and distributed among 25 flasks containing sterilized media and fully grown strains of C. blakesleeana. These flasks were then kept on a rotary shaker for 18 days at low temperatures. Later on, the reaction was stopped by adding ethyl acetate, and the same solvent was used for extraction. The organic layers were evaporated to obtain a gummy crude material which was subjected to column chromatography with 4% acetone in hexanes as solvent system. An impure fraction of about 300 mg was obtained which was again passed through a column of silica gel using 0.5% gradient methanol in dichloromethane to obtain two fractions with small impurity, finally, metabolite 7-8 were purified by recycling HPLC with methanol and deionized water (70:30) as solvent system. 2.4.1 3β,7β-Dihydroxy-11-oxo-Olean-12-en-30-oic acid (7) White shiny solid (70 mg). tR: 34 min. m.p.: 320-327 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +90 (c = 0.14). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 243, 248 nm (4.46). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3393 (OH), 1703 (enone), 1651 (acid). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): Table-3. 13 C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): Table-2. EI-MS m/z (rel. int., %): 486 [M]+ (22), 468 (34), 303 (100). HREI-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 486.3346 (C30H46O5, 486.3345). 2.4.2 3β,7β,15α-Trihydroxy-11-oxo-Olean-12-en-30-oic acid (8) White shiny solid (70 mg). tR: 34 min. m.p.: 320-327 ˚C. [𝛼]25 D : +90 (c = 0.14). UV (MeOH): λmax nm (log ɛ) 243, 248 nm (4.46). IR (CHCl3); νmaxcm-1: 3393 (OH), 1703 (enone), 1651 (acid). 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz): Table-3. 13 C-NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz): Table-2. EI-MS m/z (rel. int., %): 486 [M]+ (22), 468 (34), 303 (100). HREI-MS (mol. formula, calcd value): m/z 486.3346 (C30H46O5, 486.3345). 3 Biology 5 3.1 Urease inhibition Assay: The urease inhibition assay in vitro was performed spectrophotometrically. The reaction mixture is comprised of 25 µL of urease solution (1 U/well) was incubated with 5 µL of test compound (500 µM) for 15 minutes at 30 °C. Thereafter, 55 µL of urea (substrate) with 100 mM concentration was added, and the plate was again incubated for 15 min at 30 °C. After incubation, 45 µL of phenol reagents (1 % w/v phenol and 0.005 % w/v sodium nitroprusside), and 70 µL of alkali reagents (0.5 % w/v sodium hydroxide and 0.1 % sodium hypochlorite) were added to each well. The plate was again incubated for 50 min at 30 °C. The activity of urease was monitored with the rate of production of ammonia continuously, following the method of Weatherburn, [21] and change in absorbance was monitored at 630 nm on an ELISA plate reader (Spectra Max M2, Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Acetohydroxamic acid was used as a standard. For kinetic studies, the concentration of test compounds that inhibits the hydrolysis of substrates (jack bean urease) by 50% (IC50) was determined by monitoring the urease inhibitory effect of various concentrations of both compounds in the assay. The IC50 (inhibitor concentration that inhibits 50% activity of enzyme) values were then calculated using the EZ-Fit Enzyme kinetics program (Perrella Scientific Inc., Amherst, MA, USA). Kinetic Graphs were plotted using the GraFit program (Leather barrow RJ. GraFit Version 4.09. Staines, UK: Erithacus Software Ltd) [22]. 6 4 Results and discussion Macrophomina phaseolina (KUCC 730) has been used extensively for various biotransformation activities. In the present study, its potential for oxidative ring cleavage reactions has been reported for the first time. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) was converted into 3,4-Seco-oleanane-type metabolites, which resulted from the oxidation of 3-oxo intermediates to seven-membered ring lactone, which were then hydrolyzed to get the resulting metabolites, and hydroxylated (C-7, C-15) metabolites. Compounds 2-4 were published earlier through the biotransformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid with Chania antibiotic all spectral data were compared with reported data [18]. Metabolite 5 was obtained as a white amorphous powder through RP-HPLC, fixed with column JAIGEL ODS H-80 (MeOH: H2O; 80:20), at a retention time (tR) of 20 minutes. The molecular formula for metabolite 5 was determined as C30H47O7 by HRFAB-MS ([M + H]+ at m/z 519.3335 (calcd. 519.3322), with an additional mass of 48 a.m.u. in the substrate. There is an addition of three oxygen atoms in metabolite 5. The 1H-NMR spectrum of metabolite 5 indicated an additional peak of methane proton as a double doublet at δ 4.22 (J15α,16α = 11.0 Hz, J15α,16e = 4.5 Hz). The 13C-NMR spectrum of metabolite 5 further indicated the presence of an additional hydroxyl group through the appearance of a downfield peak at δ 65.5 (C-15). However, the 13C-NMR spectrum also showed one of the two carboxyl carbons at δ 170.3, and a downfield signal for tertiary carbinol carbon (C-4) at δ 76.1. This indicated the opening of the ring between C-3, and C-4. The position of newly incorporated hydroxyl moiety was deduced from HMBC correlations. H-15 (δ 4.22, dd) showed correlations with C-16 (δ 36.4), and C-28 (δ 22.8), and indicated hydroxylation at C-15. The hydroxyl moiety at C-15 was further supported by COSY correlations of H2 -16 (δ 1.72, m; 1.46, m) with H-15 (δ 4.22, dd). The position of the other hydroxyl group at C-4 was deduced from HMBC correlations of H-23 (δ 1.26, s), H-24 (δ 1.29, s), and H-5 (δ 1.42, m) with C-4 (δ 76.1). Similarly, H2-1 (δ 2.40, m; 1.93, m), and H2-2 (δ 2.60, m; 2.40, m) showed HMBC correlations with carboxyl C-3 (δ 170.3) and indicated a ring cleavage. The stereochemistry of -OH group at C-15 was assigned as αoriented based on NOESY correlations of β-oriented H-15 with β-oriented H-26 (δ 1.38, s), and H-28 (δ 0.75, s). Based on 1H-NMR, 13 C-NMR, IR, and mass spectrometric analyses, metabolite 5 was deduced as a new compound 3,4-Seco-4,15α-dihydroxy-11-oxo-18β-Olean12-en-3,30-dioic acid (5). Metabolite 6 was isolated as a white shiny solid with the help of recycling RP-HPLC, fixed with column JAIGEL ODS H-80 (MeOH: H2O; 80:20), and retention time (tR) of 18 minutes. Its molecular composition was determined as C31H49O7 by HRFAB-MS ([M + H]+ at m/z 533.3498, calcd. 533.3478), with an increment of 62 a.m.u. This 7 suggested the incorporation of three oxygen atoms and a methyl group. The 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 6 was found to be different from substrate 1 in many ways. First, an additional methyl signal appeared at δ 3.59 as a single, which was not present in the substrate. Secondly, a methine proton appeared as a double doublet at δ 4.22 (J15α,16α = 12.0 Hz, J15α,16e = 4.0 Hz). The 13C-NMR spectrum further indicated the presence of an additional methoxy carbon at δ 51.9 (C-31) and suggested the insertion of a methoxy group. The incorporation of a hydroxyl group at C-15 was observed through the downfield signal at δ 65.3 (C-15). The position of the newly introduced methoxy group was deduced based on the HMBC correlation of H-31 (3.59, s) with C-3. Additionally, H2-1 (δ 2.55, m; 2.18, m), and H2-2 (δ 2.66, m; 2.34, m) showed HMBC correlations with C-3 (δ 176.9), which indicated the incorporation of a methoxy group at C-3. The relative configuration of -OH group at C-15 was assigned as α on the basis of NOESY correlations of geminal β-oriented H-15 with β-oriented, H-26 (δ 1.37, s), and H-28 (δ 0.76, s). Based on spectroscopic data, metabolite 6 was deduced as a new compound, 3,4seco-4,15α-dihydroxy-11-oxo-18β-Olean-12-en-3,30-dioic acid, 3-methyl ester (6). 4.1 Biological Evaluation and Structure-Activity Relationship: 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (1), and its metabolites 2–8 were evaluated for their urease inhibitory assay. The addition of different substituted groups on the icosahydropicene skeleton were carefully studied to elucidate the best possible structure-activity relationship. Compound 1 (substrate) showed a potent activity with an (IC50 =13.2 ± 0.9 µM), as compared to the reference compound, acetohydroxamic acid (IC50 = 20.3 ± 0.43 µM). The activity might be due to the icosahydropicene skeleton and up to some extent due to the hydroxal groups and ketone groups present on the icosahydropicene skeleton. The π-electron of the icosahydropicene skeleton might forms the hydrophobic bonds with the side chains of the amino acids and with the bi-nickel center of the urease enzyme. Such π-electron-metal interactions are very well known for their role in the enzyme-ligand interactions While comparing compounds 7 (IC50 = 22.4 ± 1.13 µM), 4 (IC50 = 23.8 ± 0.64 µM) and 5 (IC50 = 25.8 ± 0.78 µM) with compound 1, a slight decrease in their IC50 values were 8 observed. Such variation in the activity might be due to the modification in their structure by the addition of different functional groups at different positions of the icosahydropicene skeleton. Compound 7 where hydroxal were substituted at C-7, similarly, in compound 4 where a phenyl ring is replaced with the propanoic acid at C-10, hydroxal group and methyl groups at C-4 the compound showed further decrease in the activity in comparison to compound 7, while in compound 5 where a hydroxal group is placed at C-15 the compound activity further increases as compared to compound 4. An interesting correlation was observed from the pattern of the activities of these compounds that the addition of Hydroxal groups at different position significantly vary the compound activity. Whereas, compound 2 was found to be weak active with (IC50 = 38.6 ± 2.3 µM) in comparison to compound 1. While compounds 3, 6, and 8 were found to be inactive. In addition, mechanism-based studies of these compounds revealed the type of inhibition and their Ki values. Kinetic study of the compound 1 inferred that the compound inhibits urease enzyme in a competitive-manner, in competitive inhibition Km changes while Vmax remains constant. On the other hand, compounds 7 and 5 showed a mixed-type of inhibition where an increase occurred in both Km and Vmax values. Whereas, compound 4 was found to be a non-competitive inhibitor, where Km remains constant and Vmax varied. The Ki values and type of inhibition are tabulated in Table-1. Table-1: The IC50 and Ki values of active compounds. Compounds code Ki values µM IC50 values µM Type of Inhibition 1 21.3 ± 0.32 13.2 ± 0.9 Competitive inhibitor 7 25.6 ± 1.62 22.4 ± 1.13 Mixed type inhibitor 4 28.2 ± 1.21 23.8 ± 0.64 Non-competitive inhibitor 5 32.8 ± 0.82 25.8 ± 0.78 Mixed type inhibitor Standard* 17.2 ± 0.21 20.3 ± 0.43 Competitive inhibitor *Acetohydroxamic acid was used as positive control 9 V 0.8 25.0000 0.6 20 20.0000 A B 15.0000 Slope = Km/Vmax 0.4 0.2 1/V G 0 -0.2 10 10.0000 5.0000 0 0.0000 -10 -0.4 -20 -0.6 -0.8 -0.08 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 0 0.04 0.08 Inhibitor 1/S 2.0000 0.2 1.0000 C 0.1 1/V -0.04 3 0.5000 0.2500 0 -0.1 -0.2 -20 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor Figure-1: Urease inhibition by compound 1, (A) Line-weaver Burk plot of reciprocal rate of reaction 1/v against reciprocal of substrate 1/s (urea) in the absence (▲) and in the presence of 5 µM (∆), 10 µM (■), 15 µM (□), 20 µM (●) and 25 µM (○) of compound 1. (B) Secondary replot of Line-weaver Burk plot is between slopes of each line on Line-weaver Burk vs different concentrations of compound 1, and (C) Dixon plot reciprocal of rate of reaction vs different concentrations of compound 1. 10 0.4 Slope = Km/Vmax A 0.2 1/V 25.0000 0.1 20.0000 0 15.0000 0.05 Km/Vmax B 10.0000 0 5.0000 0.0000 -0.05 -0.2 -0.1 -0.4 -2 -1 0 1 -20 2 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor 1/S 0.4 2.0000 1.0000 1/V 0.2 C 0.5000 0.2500 0 -0.2 -0.4 -20 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor Figure-2: Urease inhibition by compound 7, (A) Line-weaver Burk plot of reciprocal rate of reaction 1/v against reciprocal of substrate 1/s (urea) in the absence (▲) and in the presence of 10 µM (■), 15 µM (□), 20 µM (●), and 25 µM (○) of compound 7. (B) Secondary replot of Line-weaver Burk plot is between slopes of each line on Lineweaver Burk vs different concentrations of compound 7, and (C) Dixon plot reciprocal of rate of reaction vs different concentrations of compound 7. 11 0.4 1 16.0000 Slope = Km/Vmax A 0.5 1/V ( 20.0000 0 -0.5 B 0.2 12.0000 8.0000 0 4.0000 0.0000 -0.2 -1 -0.4 -2 -1 0 1/S 1 2 -20 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor 1.5 2.0000 1 1.0000 C 0.5000 0.5 1/V 0.2500 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5 -20 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor Figure-4: Urease inhibition by compound 4, (A) Line-weaver Burk plot of reciprocal rate of reaction 1/v against reciprocal of substrate 1/s (urea) in the absence (▲) and in the presence of 10 µM (∆), 15 µM (■), 20 µM (□), 25 µM (●) and 30 µM (○) of compound 4. (B) Secondary replot of Line-weaver Burk plot is between slopes of each line on the Line-weaver Burk vs different concentrations of compound 4, and (C) Dixon plot reciprocal of rate of reaction vs different concentrations of compound 4. 12 0.3 45.0000 0.06 0.2 35.0000 A 0.1 1/V Slope = Km/Vmax 0.04 0 -0.1 B 30.0000 0.02 25.0000 0 0.0000 -0.02 (Column 7) -0.04 -0.2 -0.06 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 -30 1/S -20 -10 0 10 20 Inhibitor 0.4 2.0000 C 0.2 1.0000 1/V 0.5000 0.2500 0 -0.2 -0.4 -40 -20 0 20 40 Inhibitor Figure-5: Urease inhibition by compound 5, (A) Line-weaver Burk plot of reciprocal rate of reaction 1/v against reciprocal of substrate 1/s (urea) in the absence (∆), and the presence of 15 µM (■), 20 µM (□), 25 µM (●), and 30 µM (○) of compound 5. (B) Secondary replot of Line-weaver Burk plot is between slopes of each line on Lineweaver Burk vs different concentrations of compound 5, and (C) Dixon plot reciprocal of rate of reaction vs different concentrations of compound 5. 4 Conclusion A total of seven 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (1) derivatives were synthesized via biotransformation with M. phaseolina and C. blakesleeana. Two of them, metabolites 5 and 6 were found to be new. Hydroxylations at C-7, and C-15, and oxidative ring cleavage between C-3, and C-4 (Bayer-Villiger-type oxidation), and esterification were observed. In vitro urease inhibition is an important approach for the treatment of diseases caused by urease producing bacteria. The resulted metabolites were evaluated against urease enzyme. Some of the transformed metabolites have shown potent activity against the urease enzyme. This study will help to open new ways in the development of new anti-urease agents. 13 30 Table-2: 1H- and 13C- NMR Data (J in Hz) for metabolites 1–4, chemical shifts are in ppm. 1 Carbon 2 δC 1 38.4 2 26.9 3 4 5 6 76.5 38.7 54.0 17.0 7 32.0 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 42.8 61.1 36.6 198.9 127.2 169.5 44.8 26.0 16 25.7 17 18 19 31.4 48.0 40.5 20 21 43.0 30.3 22 37.4 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28.1 15.9 18.3 16.1 22.9 28.3 27.7 177.5 δH 2.56, m; 0.95,m 1.52, overlap; 1.39, overlap 3.00, m 0.69, overlap 1. 50, overlap; 1.35, overlap 1.62, m; 1.32, overlap 2.31,s 5.38, s 1.73, m; 1.13, m 2.06, m; 0.95, m 2.04, m 1.69, m; 1.66, m 1.77, overlap; 1.35, overlap 1.25, m; 1.31, overlap 0.89, s 0.67, s 1.01, s 1.02, s 1.35, s 0.74, s 1.08, s - δC 3 δH 39.0 31.9 174.5 84.9 51.9 21.6 30.9 43.0 60.7 39.7 198.0 127.3 170.0 44.7 26.0 25.7 31.5 47.9 40.7 43.1 30.3 37.4 31.2 26.0 17.7 17.5 22.7 28.4 27.8 δC 2.30, m; 1.59, m 2.62, m; 2.42, m 1.80, overlap 1.49, m 32.7 1.71, overlap; 1.32, overlap 2.62, s 5.44, s 1.75, m; 1.15, m 2.05, m; 0.95, m 2.10, m 1.69, m; 1.68, m 1.77, m; 1.35, m 1.34, m ; 1.27, m 1.39, s 1.32, s 1.24, s 1.05, s 1.36, s 0.75, s 1.08, s - 33.2 4 δH δC δH 2.93, m; 2.47, m 2.64, m; 2.34, m 1.40, overlap 1. 85, m; 1.25, overlap 1.71, overlap; 1.40, overlap 2.85, s 5.59, s 1.57, overlap 32.1 2.12, m; 1.02, m 2.19, m 27.8 45.0 32.2 39.0 2.48, m; 2.13, m 1.40, overap 2.38, overlap; 1.93, m 2.60, m; 2.35, m 2.21, m 167, m; 1.60, m 3.97, dd (J7α,6α = 11.2, J7α,6e = 4.4) 2.77, s 5.63, s 2.09, overlap; 1.67, overlap 2.09, overlap; 0.98, m 1.53, m 1.89, m; 1.72, m 1.37, overlap 39.0 1.39, m 32.8 28.4 19.0 20.3 23.4 29.2 28.8 180.8 1.28, s 1.27, s 1.16, s 1.38, s 1.44, s 0.83, s 1.16, s - 32.7 28.4 12.3 20.0 23.4 29.2 28.9 181.8 1.29, s 1.27, s 1.12, s 1.38, s 1.59, s 0.82, s 1.29, s - 36.4 171.9 76.0 52.6 27.5 54.8 54.8 52.5 202.3 129.3 171.9 47.0 22.5 27.3 33.0 49.8 42.3 45.1 31.5 36.1 171.9 75.5 50.7 33.3 72.4 42.5 55.3 46.6 201.7 129.5 171.5 51.8 31.2 33.0 49.8 42.7 Table-2: 1H- and 13C- NMR Data (J in Hz) for metabolites 5–8, chemical shifts are in ppm. Carbon 5 δC 1 33.0 6 δH 2.40, m; 1.93, m δC 30.7 7 δH 2.55, m; 2.18, m δC 38.1 8 δH 2.52, overlap; δC 38.2 0.84, m δH 2.55, m; 0.88, overlap 2 36.7 2.62, m; 2.40, m 36.2 2.66, m; 2.34, m 28.4 1.56, m; 1.33, m 26.7 1.64, m; 1.50, m 3 170.3 - 176.9 - 76.4 3.00, m 76.3 3.01, m 14 4 76.1 - 75.7 - 38.4 - 38.4 - 5 52.3 1.42, m 52.7 1.34, m 50.7 0.70, m 50.5 0.72, overlap 6 22.6 1.57, overlap 22.1 1.58, m; 1.48, m 29.5 2.02, m; 1.52, m 26.9 1.43, m; 1.40, m 7 33.3 1.70, m; 33.1 1.74, m; 1.43, 70.7 3.89, dd (J7α,6α = 70.3 3.89, dd (J7a,6a = overlap 1.41, overlap 10.4, J7α,6e = 4.8) 10.8, J7a,6e = 4.8 ) 8 47.2 - 46.8 - 42.9 - 42.9 - 9 54.0 2.83, s 54.1 2.77, s 61.3 2.24, s 61.3 2.21, s 10 46.1 - 42.0 - 36.6 - 36.7 - 11 202.1 - 201.8 - 198.6 - 198.2 - 12 129.3 5.63, s 129.0 5.65, s 127.3 5.41, s 127.8 5.48, s 13 170.3 - 170.3 - 169.7 - 169.9 - 14 47.0 - 47.0 - 44.2 - 49.4 - 15 65.5 4.22, dd (J15α,16α = 65.3 4.22, dd (J15α,16α = 26.1 2.03, m; 0.89, 65.5 4.09, dd (J15α,16α = 11.0, J15α,16e = 4.5 ) 16 36.4 1.72, m; 1.46, m 12.0, J15α,16e = 4.0 ) 36.1 1.74, m; 1.48, overlap 11.6, J15α,16e = 5.2 ) 26.9 1.49, m; 1.38, m 34.8 2.00, m; 1.18, m overlap 17 37.9 - 37.7 - 31.4 - 31.5 - 18 51.8 2.41, m 51.6 2.43, m 48.7 2.06, m 49.1 2.03, m 19 42.5 1.91, m; 1.66, m 42.5 1.91, m; 1.69, m 40.8 1.68, m; 1.65, m 40.4 1.69, m; 1.62, m 20 45.2 - 45.2 - 43.0 - 50.7 - 21 31.8 1.96, m; 1.36, 31.7 1.95, m; 1.37, 30.3 1.76, m; 1.30, m 30.3 1.77, overlap; 1.34, overlap overlap overlap 22 32.6 2.10, m; 1.13, m 32.8 1.12, m; 2.01, m 37.4 1.26, m ; 1.22, m 37.1 1.36, m; 1.22, m 23 32.9 1.29, s 32.7 1.27, s 28.0 0.89, s 27.8 0.90, s 24 28.3 1.26, s 28.2 1.26, s 15.9 0.66, s 16.0 0.67, s 25 19.1 1.17, s 18.9 1.17, s 16.0 1.00, s 15.8 1.00, s 26 20.3 1.38, s 20.1 1.37, s 12.2 0.98, s 12.5 1.00, s 27 24.5 1.51, s 24.2 1.50, s 23.0 1.37, s 17.9 1.32, s 28 22.8 0.75, s 22.6 0.76, s 28.3 0.74, s 28.9 0.76, s 29 29.0 1.15, s 28.8 1.14, s 27.8 1.07, s 28.0 1.08, s 30 182.3 - 182.4 - 177.7 - 177.5 - 51.8 3.59, s 31 15 Figure-1: Biotransformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (1) with M. phaseolina. 16 Figure-2: Biotransformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (1) with C. blakesleean Figure-3: Key HMBC, COSY, and NOESY correlations in metabolite 5. Figure-4: Key HMBC, COSY, and NOESY correlations in metabolite 6. 17 References 1 Erlanson, D. A., Fesik, S. W., Hubbard, R. E., Jahnke, W. and Jhoti, H. Twenty years on: The impact of fragments on drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov., 15, 605 (2016). 2 Guo, Z. The modification of natural products for medical use. Acta Pharm. Sin. B., 7, 119-136 (2017). 3 Harvey, A. L., Edrada-Ebel, R. and Quinn, R. J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov., 14, 111-129 (2015). 4 Fan, B., Jiang, B., Yan, S., Xu, B., Huang, H. and Chen, G. Anti-inflammatory 18βglycyrrhetinin acid derivatives produced by biocatalysis. Planta Med., 85, 56-61 (2019). 5 Cao, D., Jiang, J., Zhao, D., Wu, M., Zhang, H., Zhou, T., Tsukamoto, T., Oshima, M., Wang, Q. and Cao, X. The protective effects of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid against inflammation microenvironment in gastric tumorigenesis targeting PGE2-EP2 receptor-mediated arachidonic acid pathway. Eur. J. Inflamm., 16, 2058739218762993 (2018). 6 Kowalska, A. and Kalinowska‐Lis, U. 18β‐Glycyrrhetinic acid: its core biological properties and dermatological applications. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci., 41, 325-331 (2019). 7 Hussain, H., Green, I. R., Shamraiz, U., Saleem, M., Badshah, A., Abbas, G., Rehman, N. U. and Irshad, M. Therapeutic potential of glycyrrhetinic acids: A patent review (2010-2017). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat., 28, 383-398 (2018). 8 Ma, Y., Liu, J.-M., Chen, R.-D., An, X.-Q. and Dai, J.-G. Microbial transformation of glycyrrhetinic acid and potent neural anti-inscommatory activity of the metabolites. Chin. Chem. Lett., 28, 1200-1204 (2017). 9 Feng, X., Ding, L. and Qiu, F. Potential drug interactions associated with glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhetinic acid. Drug Metab. Rev., 47, 229-238 (2015). 10 Li, K., Ma, T., Cai, J., Huang, M., Guo, H., Zhou, D., Luan, S., Yang, J., Liu, D. and Jing, Y. Conjugates of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives with 3-(1H-benzo [d] imidazol-2-yl) propanoic acid as Pin1 inhibitors displaying anti-prostate cancer ability. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 25, 5441-5451 (2017). 11 Borges, K. B., de Souza Borges, W., Durán-Patrón, R., Pupo, M. T., Bonato, P. S. and Collado, I. G. Stereoselective biotransformations using fungi as biocatalysts. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry., 20, 385-397 (2009). 18 12 Ahmad, M. S., Zafar, S., Bibi, M., Bano, S. and Choudhary, M. I. Biotransformation of androgenic steroid mesterolone with Cunninghamella blakesleeana and Macrophomina phaseolina. Steroids., 82, 53-59 (2014). 13 Farooq, R., Hussain, N., Yousuf, S., Ahmad, M. S. and Choudhary, M. I. Microbial transformation of mestanolone by Macrophomina phaseolina and Cunninghamella blakesleeana and anticancer activities of the transformed products. RSC Advances., 8, 21985-21992 (2018). 14 Yoshida, K., Furihata, K., Yamane, H. and Omori, T. Metabolism of 18βglycyrrhetinic acid in Sphingomonas paucimobilis strain G5. Biotechnol. Lett., 23, 253-258 (2001). 15 Iqbal Choudhary, M., Ali Siddiqui, Z., Ahmed Nawaz, S. and Atta-ur-Rahman. Microbial transformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid by Cunninghamella elegans and Fusarium lini, and lipoxygenase inhibitory activity of transformed products. Nat. Prod. Res., 23, 507-513 (2009). 16 Maatooq, G. T., Marzouk, A. M., Gray, A. I. and Rosazza, J. P. Bioactive microbial metabolites from glycyrrhetinic acid. Phytochemistry., 71, 262-270 (2010). 17 Asada, Y., Saito, H., Yoshikawa, T., Sakamoto, K. and Furuya, T. Biotransformation of 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid by ginseng hairy root culture. Phytochemistry., 34, 10491052 (1993). 18 Hameed, A., Al-Rashida, M., Uroos, M., Qazi, S. U., Naz, S., Ishtiaq, M. and Khan, K. M. A patent update on therapeutic applications of urease inhibitors (2012–2018). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat., 29, 181-189 (2019). 19 Alamzeb, M., Omer, M., Ur-Rashid, M., Raza, M., Ali, S., Khan, B. and Ullah, A. NMR, novel pharmacological and in silico docking studies of oxyacanthine and tetrandrine: Bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids isolated from Berberis glaucocarpa roots. J. Ana. Meth. Chem., 2018 (2018). 20 Larik, F. A., Faisal, M., Saeed, A., Channar, P. A., Korabecny, J., Jabeen, F., Mahar, I. A., Kazi, M. A., Abbas, Q. and Murtaza, G. Investigation on the effect of alkyl chain linked mono-thioureas as Jack bean urease inhibitors, SAR, pharmacokinetics ADMET parameters and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Chem., 86, 473-481 (2019). 21 Weatherburn, M. Phenol-hypochlorite reaction for determination of ammonia. Anal. Chem., 39, 971-974 (1967). 22 Amtul, Z., Kausar, N., Follmer, C., Rozmahel, R. F., Kazmi, S. A., Shekhani, M. S., Eriksen, J. L., Khan, K. M. and Choudhary, M. I. Cysteine based novel noncompetitive inhibitors of urease. Distinctive inhibition susceptibility of microbial and plant ureases. Bioorg. Med. Chem., 14, 6737-6744 (2006). 19 20