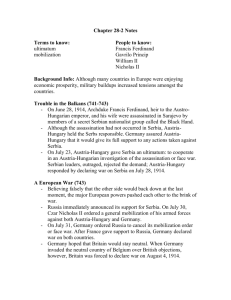

Austro-German Plans for Serbia (1915): Analysis & Documents

advertisement

Austro-German Plans for the Future of Serbia (1915) Author(s): R. W. Seton-Watson Source: The Slavonic and East European Review , Mar., 1929, Vol. 7, No. 21 (Mar., 1929), pp. 705-724 Published by: the Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4202346 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Modern Humanities Research Association and University College London, School of Slavonic and East European Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Slavonic and East European Review This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms UNPRINTED DOCUMENTS. AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR THE FUTURE OF SERBIA (19 I 5). IT will be remembered that in the autumn and winter of I9I4 Serbia showed unexpected powers of resistance to the enemy -and in December defeated the Austro-Hungarian forces at Rudnik and expelled them from Belgrade. There followed a long period of inactivity on the Balkan front, due on the one hand to Serbia's exhaustion and the outbreak of a severe typhus epidemic, and on the other to Austria-Hungary's absorption on the Russian front. During this period the Entente made a series of efforts to win over Italy, Roumania and Bulgaria to active participation on its side. With Italy this resulted in the secret Treaty of London, concluded on 26 April, I9I5, and Italy actually entered the War on 24 May. But with Bulgaria the negotiations were inconclusive-first because the failure of the Dardanelles expedi- tion and the events of the Galician campaign confirmed the King and General Staff in their belief in the ultimate victory of the Central Powers; but secondly because the entry of Bulgaria could only be secured by such a cession of territory in Macedonia as the Serbs were unanimous in refusing. A compromise might perhaps still have been reached, but the Entente realised too late (or failed to realise altogether) that by assigning to Italy under the Treaty of London so large a portion of Jugoslav national territory on the Adriatic, it had made Serbian concessions in the east impossible, since national unity and full access to the Adriatic could alone atone for the loss of the Vardar valley with its economic outlet to the LEgean. Thus from May onwards the Serbian Government in Nis was in a very difficult position and found its allies negotiating behind its back with Italy, and less secretly with Bulgaria, and in each case using vital Jugoslav interests to pay the bill. It was only natural that this should have been regarded by some people as a favourable moment for exploring the possibility of winning Serbia for a separate peace and thus liquidating one at least of the theatres of war. 705 z This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms z 706 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. On 23 May, Germany and Austria-Hungary officially approached Bulgaria, offering in return for mere neutrality both zones of Serbian Macedonia. On 29 May the four Entente Powers handed Bulgaria a note offering in return for war on Turkey the Enos-Midia Line and Macedonia up to the line Egripalanka-VelesOhrid-Monastir, but only if she refrained from immediate occupation and only if Serbia obtained compensation in Bosnia and on the Adriatic-in other words, a futile offer, much inferior to that of the Central Powers. On I4 June Bulgaria replied with a series of questions of detail: but it was not till 4 August that the Entente again answered, guaranteeing the " Undisputed " Mace- donian Zone and Kavala, if Serbia and Greece were compensated elsewhere, and the immediate occupation of Thrace. This being rejected as quite inadequate, Bulgaria on 3 September signed a Convention with Turkey and on 6 September a secret alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, which guaranteed to her in return for entry, not only both Macedonian Zones but also all Serbia proper east of the River Morava from the Danube to the Sar mountains; and the military convention pledged the three High Commands to joint action against Serbia. The Bulgarian Government continued to dupe the Entente representatives, whose further Note on I3 September (threatening to revoke their former offer) was only answered on 4 October and then quite evasively. But already on 6 October the Austro-German forces attacked Serbia on the Danube front, Bulgaria joined in a week later (not declaring war until I4 October in order to delude the Entente up to the last moment), and the conquest of Serbia followed. Skoplje fell on 2I October, Nis on 5 November, and what was left of the Serbian army retreated across Albania to the Adriatic. This brief summary of events will enable the reader to grasp the significance of the following important documents copied from the Austrian archives in the months immediately following the War and handed to me from a trustworthy source. From them it appears that the pressure exercised by the Entente upon Serbia during the summer of I9I5 led to suggestions of a separate peace, that the Roumanian statesman Marghiloman attempted to mediate on these lines, and that late in September Herr von Jagow hoped that Serbia's surrender might avert the impending campaign. Naturally, however, the desire of both AustriaHungary and Bulgaria to crush Serbia overrode the practical considerations of Berlin. The conquest of Serbia naturally led to a discussion of her ultimate fate. Germany proposes that what remains of Serbia This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 707 after Bulgaria has annexed the south and east, should be united with Montenegro and Albania under the Montenegrin dynasty (No. I2). Count Metternich, the new German Ambassador to the Porte, talks, both in Vienna and Sofia, in favour of a separate peace and opposes Serbia's complete disappearance (Nos. I4-I5): and his Austro-Hungarian colleague, Marquis Pallavicini, endorses his view (No. i6) on the ground that a Big Bulgaria would be quite as great a danger to the Central Powers " as the Great Serbia founded in I9I3." Of special interest are two memoranda of the Hungarian Premier, Count Tisza-the first addressed to Francis Joseph, the second to Baron Burian-in which he opposes the annexation of the whole of Serbia, not on grounds of equity or humanity, but simply because it would be difficult and dangerous for the Monarchy to increase the numbers of her Southern Slav subjects. His remedy is one of the most cynical and amazing in the whole war. Bulgaria is to annex Macedonia and all Serbia east of the Morava, Albania would receive territory from both Serbia and Montenegro (this is of course less exceptionable), Montenegro would be cut off from the sea, and Belgrade, with the fertile districts along the south bank of the Save and Danube, would be cut off from Serbia and annexed to Hungary: while Magyar and German colonisation on a grand scale would be adopted in the new frontier districts, with the deliberate object of driving " a wedge between the Serbian State and the Serbian population of Slavonia and Southern Hungary." This " mangled " and isolated Serbian state would then be " bound by economic and military ties to the Monarchy " : the Karagjorgjevic dynasty would of course disappear, and the question of the Montenegrin dynasty might be left open. These memoranda deserve the closest attention, as showing that Tisza's opposition to complete annexation, of which his adherents have made so much capital, is merely part of a well- thought-out project for preventing the development of the Southern Slavs, in the interests of Hungarian hegemony. His relative mildness toward Montenegro is explained by the later series of documents, showing that Crown Prince Danilo had offered himself to the Central Powers, in the hope of supplanting his Serbian kinsmen, and that his brother, Prince Mirko, was definitely in the pay of Vienna. R. W. SETON-WATSON. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 708 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. I. COUNT TARNOWSKI 1 to VIENNA. Tel. No. 2340. Dated Sofia, 22 May, I9I5. My German colleague tells me, has had instructions to impress King and Government, and has warned Mr. Radoslavov,2 that according to certain signs there is inclination in Serbia towards understanding with Austria-Hungary, to which, in view of conflict with Italy, Monarchy might consent. German Minister has also put this flea in ears of Macedonians, in order that they may demand action from Government. I said I had no information at all in the matter. German colleague requested me not to announce the above, but rather to wait until something is communicated to me regarding it. When I then spoke with Premier, he mentioned what Dr. Michahelles 3 had said about Serbia, and asked me what I thought. I said I was quite without information about Serbia and had no view. Radoslavov said he could not believe the story; it couldonly be a matter of floating opinions (Stimmungen) in Serbia. 2. COUNT CZERNIN 4 to VIENNA. 2773-I232. Tel. No. 947. Dated Sinaia, I3 August, I9I5. Mr. Marghiloman 6 told my German colleague that Serbian Minister had spoken to him as follows: " Entente demands from Serbia cession of all Macedonia, including Uskuib, to Bulgaria, without promising access to the Adriatic in return. As compensation Serbia would only obtain Herzegovina." Serbian Minister is said, apparently in agreement with Mr. Pasic,7 -to have expressed his desperation at this demand and at Serbia's ,desperate state, yet to have hinted that Serbia, if she cannot free herself from the arms of the Entente, will have to accept demands. But Serbian Minister appears further to have given Mr. Marghiloman to understand, that separate peace with the Monarchy seems to him desirable, in which case Serbia would be ready tb cede Macedonia as far as the Vardar, if she received assurance of access to the LEgean and were not cut off from Greece. Mr. Pasic, it is alleged, only wants to give a definite answer to Entente in about five days, if he has received further news from the Serbian Minister here. German colleague and Marghiloman have impression that Mr. Pasic, who knows the good relations that we have to Marghiloman, may have intentionally chosen this channel (Weg) and could be strengthened by Your Excellency in his resistance to the Entente. 1Austro-Hungarian Minister in Sofia. 2 Bulgarian Premier. 3German Minister in Sofia. 4 Austro-Hungarian Minister in Bucarest. Summer resort of Roumanian Court. 6 Leading Roumanian Conservative statesman, favourable to Central Powers. 7Italics in original. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 709 Marghiloman comes to-day to me at Sinaia, in order to repeat again to me direct these news, which have already been transmitted through German colleague. German Minister has wired the incident to Berlin. I beg for instructions to regulate my language. 3. COUNT CZERNIN to VIENNA. Tel. No. 963. Dated Sinaia, I9 August, I9I5. (In continuance of my Tel. 952 of I4th) I have to-day repeated to Mr. Marghiloman what my German colleague has already said to him, namely that the German Government has let him know that the Central Powers find no reason for approaching Serbia and must leave it to her to make possible (eventuelle) proposals. Marghiloman thereupon had a conversation with the Serbian Minister, who is alleged to be disappointed at this answer and to have ventilated the view that there was great danger of Serbia and Bulgaria coming to terms against us. 4. PRINCE GOTTFRIED HOHENLOHE 1 to VIENNA. No. 428. Dated Berlin, 27 September, I9I5. (Strictly secret.) The Secretary of State 2 said to me to-day, he had heard from various sides, that it was not excluded that Serbia would not let matters come to a conflict: he had therefore instructed Herr von Tschirschky 3 to discuss with Your Excellency the situation which might result from this, in the event of Serbia really at the last moment, out of fear of being crushed by the Central Powers, being ready to submit to our wishes in a peaceful manner. Herr von Jagow would be glad to know what conditions the Cabinet of Vienna would in this case put to Serbia. I replied that for the present I knew nothing whatever of such an intention on the part of Serbia, and could therefore give him no information as to the attitude which Your Excellency would take in such a case. It also seemed to me not very probable that Serbia, without fighting, would come as far towards us as we should have to demand of her. I considered any half-measure towards Serbia, unless we were simply compelled to content ourselves with this, as incompatible with our prestige, and in view of the future as more than questionable. The possibility of avoiding the whole expedition to Serbia seemed to be extraordinarily desirable to Herr von Jagow. I doubt whether Serbia's attitude will render this possible and would also, for above-mentioned reasons, regard it as by no means desirable. 5. ANSWER OF THE BALLPLATZ to PRINCE HOHENLOHE. (No date.) The German Ambassador came to see me to-day regarding the enquiry which your telegram 428 led me to expect. I answered Herr 1 Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Berlin. 2 Herr von Jagow. 3 German Ambassador in Vienna. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 7IO THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. von Tschirschky, that according to all indications available to us, Serbia will certainly take up the struggle against our attack and will not make any offers of peace. But if this should unexpectedly be the case after all, I regarded it as a fatal error to let ourselves be held back in our action by it for one moment. We must make sure of all the aims which led us to start a new offensive and to conclude our treaties with Bulgaria. This we owed as much to our own interests as to those of our Balkan allies. If Serbia should offer us peace before the beginning of military operations, we must none the less first of all occupy all those parts of the country which we need for the attainment of our war aims, and can then, in possession of the territorial pledge, and of free connection with Bulgaria and Turkey, examine Serbia's proposals. An abandonment or delay of our action in face of a yielding attitude of Serbia, which might after all possibly arise in order to win time, would in my view . . . (verb missing) 1 not only at the Dardanelles and in the Balkans but also in its ultimate effects, in the other theatres of war. The remarks with which Your Excellency met the feeler (Anwurf) of the Secretary of State, meet with my full approval. 6. BARON SZILASSY2 to VIENNA. (Numbers missing.) Dated Athens, 28 September, I9I5. (Strictly secret.) The King 3 told me, with a request for secrecy, that German Government wishes him to mediate peace between us and Serbia, " but that it is difficult." His Majesty told me that Greek Minister in Berlin had announced the impression that we were inclined to give to Serbia North Albania and all Montenegro. In case the German Legation . . . (faulty cipher), I remind you that its cipher has probably been deciphered. 7. ANSWER OF THE BALLPLATZ to BARON SZILASSY. No. 339. 30 September, I9I5. Re your telegram, unnumbered, of 28 inst. For your informatiorn and guidance: here 4 there is no possible cause of any kind to consider peace ideas with Serbia. 8. COUNT TARNOWSKI to VIENNA. No. ii6i. Sofia, 30 September, 19I5. It was widely said here that latterly in military circles serious fears prevailed as to surprise attack of the Serbs, who have sent five divisions to the Bulgarian frontier and could interfere with 1 Either a faulty cipher, or an error on the part of the co 2 Austro-Hungarian Minister in Athens. 3 Constantine XII. of Greece. 4 I.e., in Vienna. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 202, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 7II mobilisation. A connection was even assumed between the ministerial crisis (resignation of Toncev 1) and this fear, in the sense that King and Radoslavov, by negotiations with Democrats and perhaps by their inclusion in the Cabinet, wanted to create a calming effect upon the Entente and thereby hold Serbia back from the attack. Premier said to me in this connection, that at the War Ministry they were really excited, but that there was no ground for this. General Zekov was sensible, but otherwise there was not a man of judgment in the War Ministry, nothing but gas-bags (Schwdtzer), and so on. The theory of a connection with the crisis of Mr. Toncev was nonsense, fear of Serbian attack was quite unfounded; in Serbia indeed there was great fear of Bulgaria, and Premier knew that Mr. Pasic, recognising danger, had put out peace feelers in Berlin. Baron Wangenheim 2 had told Premier that Serbia's peace proposals would not be taken up at all now and without consultation with Bulgaria: they wanted to beat and punish Serbia. 9. BARON SZILASSY to VIENNA. Tel. No. 964. Athens, 2 October, I9I5. (Secret.) His Majesty 3 told me, Serbian Minister here 4 was entirely won for a separate peace. King fears that the Serbian statesmen, bribed by England, will be hard to win over. As last time, I told His Majesty that I knew nothing of this and did not believe that we want separate peace. Your Excellency's telegram No. 339 just received. IO. PRINCE HOHENLOHE to VIENNA. Tel. No. 470. Berlin, 3I October, I9I5. (Secret.) In answer to No. 7I2 of Your Excellency, I have to-day informed the Secretary of State of the contents of above-cited telegram and Your Excellency's remark contained therein: he was already informed through a telegram of Herr von Tschirschky. Herr von Jagow remarked in this connection that to him also an unconditional surrender of Serbia seemed to be the only goal to aim at, but only in the event of our not having to solve yet other difficult tasks in the Balkans. But now according to all news the Entente seems resolved to throw large masses of troops into the Balkans and to wish to strike a great blow there. For this speaks the circumstance that General Monroe, a personal friend and favourite of Lord Kitchener, has taken over the command of the English troops in Salonica, in place of the quite incompetent Hamilton. He therefore asks himself whether it would not be of advantage to have concluded the whole Serbian question by then-that is to say, in the event of the Serbs coming with a request for peace, to make known to them our conditions. I remarked on this, that these conditions, 1 Member of the Radoslavov Cabinet. 2 German Ambassador in Constantinople. King Constantine. 4 Mr. Balugdzi6, afterwards Jugoslav Minister in Berlin. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 7I2 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. apart from the cession of the territories demanded by us, must also consist in the surrender of the Serbian Army. If we could preserve peace on these conditions, continued the Secretary of State, he saw in this the great advantage that for England and France the reason for an expedition to save Serbia would disappear, after the latter had already officially accepted her fate. To this I replied, that if the Entente in spite of everything were to move against Bulgaria and perhaps win successes, Serbia would most probably not worry in the least about pledges given and would in spite of them attack us, if at all possible. Herr von Jagow admitted this indeed, but held that this outweighed in such a case, and besides an accomplished peace with Serbia would have the great advantage of proving to the Entente that we could conclude peace with our opponents even separately. Who knows whether this might not be the prelude to general peace. As regards the unmasking of our treaty with Bulgaria, this was not bound to happen, in view of the fact that we would simply demand of Serbia the cession of territory, without expressing ourselves till later as to its future destination. Herr von Tschirschky had further reported that Your Excellency adhered to the foundation of an independent Albania: as regards this, the Government had an extremely sceptical attitude after the experiences it had had, and had not the slightest desire to take any further share in it. From Your Excellency's remarks that the Monarchy's frontier must march with Albania (as reported by Tschirschky), it seemed to him (i.e., Jagow) to follow that Austria-Hungary wished to occupy the Sandjak, which he found quite comprehensible. In the same way he fully endorsed the wish of the Monarchy that the two coasts of the Adriatic should not come into the same hand: but this could perhaps be met (abgeholfen) by an Austro-Hungarian protectorate over Albania, if we held this to be practicable. He quite agreed with the&ejection of the Karagjorgjevic, but an union of what was left of Serbia with Montenegro seemed to him a less favourable solution than one by which Serbia, in whatever form, came into complete economic and military dependence upon us. I said to Herr von Jagow at the close of our conversation, that for the present there were still no signs whatever of Serbia turning to us with a request for peace: and according to the whole mentality of the Serbs it seemed to me much more probable that they would fight to the end, which must of itself involve unconditional collapse. ii. BARON BURIAN to PRINCE HOHENLOHE. No. I459. Sofia, I4 November, I9I5. (Strictly confidential.) Remains as a draft (bleibt im Concept). He treats as the essential points of peace with Serbia: I, " unconditional capitulation; 2, immediate cession of all territories demanded by us." This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 7I3 I2. SUMMARY OF NOTE DRAWN UP IN THE GERMAN EMBASSY IN VIENNA, dated 4 November, I9I5. Falkenhayn 1 is eager for the speediest possible close of the Serbian war and urges that the conditions which we are both willing to offer to Serbia if she asks for peace, should be quickly stated. The German Government's view of such conditions is: complete capitulation, and union of what is left of Serbia with Montenegro and Albania, under the Montenegrin dynasty. Germany considers the sole way of bringing Serbia to capitulate is if she does not have to capitulate in a state of uncertainty (aufs ungewisse), but receives a clear picture as to her future fate. Germany therefore asks Vienna for its views. I3. SUMMARY OF NOTE DRAWN UP IN THE GERMAN EMBASSY IN VIENNA, dated 5 November, I9I5. The fate of Serbia, Montenegro and Albania is to be discussed at the impending discussion at Berlin. Their union will not be proposed by Austria-Hungary. It is desirable to end the Serbian war as soon as possible, but this can best be attained by war. Neither Serbia nor Montenegro is likely to offer peace, " since they will scarcely abandon till the very last the hope of obtaining help from their allies." I4. COUNT TARNOWSKI to BARON BURIAN. No. I459. Sofia, 14 November, I9I5. Radoslavov recounted to me his conversation with the new German Ambassador in Constantinople, while travelling through here. Count Metternich had expressed his personal view in the sense that speediest possible conclusion of separate peace with Serbia was now urgently desirable, since final termination of this (i.e., Balkan) war must have favourable reaction upon attitude of Roumania and Greece. Premier said, he could not properly understand this idea, firstly because Serbia was not yet conquered and it was likely to last not a few days, as Count Metternich thinks, but several weeks more, till Serbia is altogether finished; and secondly, before considering peace negotiations with Serbia, one must know whether Serbia would exist at all as state. But on this point Count Metternich had not been informed and only mentioned that from a conversation with Count Tisza he had won the impression that the annexation of con- siderable (grosserer) Serbian territories would not suit Hungary. Count Metternich had asked Premier for his opinion on this, whereupon Radoslavov spoke not quite clearly and remarked that this question depended not on Bulgaria, but on the Central Powers, especially on us. To me Radoslavov then said openly that Bulgaria wished the complete disappearance of Serbia. He inquired whether our views in this connection were known to me, which I denied. It 1 German Chief of Staff from Septerrber, I9I4, to August, I9I6. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192ff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 7I4 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. would be very important for him, Premier remarked, to learn something positive on this, and he begged me in friendly way to try and get authentic information on this point. My German colleague confirmed that Count Metternich had questioned Radoslavov and also King regarding views here (in Sofia) about future disposition in the Balkans (Serbia, Albania) ; King Ferdinand was for complete disappearance of Serbia, Radoslavov less pronounced. Count Metternich had also expressed to Radoslavov his personal view, mentioned at outset, as to usefulness of separate peace with Serbia. I5. BARON BURIAN to COUNT TARNOWSKI. No. 664. I5 November, I9I5. The view expressed by Count Metternich as his personal opinion, that now the early conclusion of a separate peace with Serbia is urgently desirable, does not agree with our standpoint and indeed does not coincide with the present German view, so far as is known to us. I can only agree with Radoslavov when he marvels at above frame of ideas of German Ambassador: for it is clear that a peace with Serbia could in practice only be attained if the Serbian army has laid down its arms and if we also have finished with Montenegro. As regards the Premier's question regarding status (Gestaltung) of Serbia, Your Excellency can tell him that our decisions regarding the reduced Serbia are not yet finally reached, we are exchanging ideas on the subject with Germany, but this from the very nature of the case was not yet concluded, since the question is too closely bound up with the further development of affairs. i6. MARQUIS PALLAVICINI to BARON BURIAN. (No. ioo/P. A-C.) Constantinople, i December, I9I5. (Secret.) My best thanks to Your Excellency for the strictly confidential communication of the telegraphic correspondence with Count Tarnowski regarding a conversation between Count Metternich in Sofia and Mr. Radoslavov, in which the former raised the question of Serbia's future. Since receipt of this correspondence I had a longish conversation with the German Ambassador, in which he came to speak on the same theme. He told me he had on his way through Budapest visited Count Tisza and put to him, among other things, his view (which he expressly described as purely personal) that Serbia as such ought not to be allowed to go under completely, because she was according to his conviction a factor in the Balkan Peninsula whose continued existence would be highly useful for Austria-Hungary in the first instance. I have the impression that Mr. Radoslavov perhaps did not understand Count Metternich quite correctly: for as the latter reproduced to me what he had said to Count Tisza, he had no idea of trying This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 7I5 now to reach a separate peace with Serbia: on the contrary he thinks that when Serbia had been completely conquered it might perhaps be useful to let the Serbs know in some way, that the Central Powers by no means have in mind the complete annihilation of Serbia, but would actually wish that a reduced Serbia should continue to exist in future. To this Count Tisza, he said, had answered that the Monarchy must desire a " resigned," not a satisfied Serbia. Count Metternich told me then the further line of argument which he had developed to the Hungarian Premier. There seemed to him to be an advantage in letting the Serbs know of this desire for the continuance of a reduced Serbia, because in this way it might perhaps be easier to reach a general peace. Not that he believed that Russia would at once negotiate on that account, but in that way for Russia the main reason which had caused the war would certainly have been removed. In the same way the situation would be made easier for Serbia, as soon as she knows that the Central Powers do not reckon with her complete annihilation. Besides any further action of the British and French in the Balkans would then lose its raison d'e'tre, and finally the giving of a turn to the future Balkan situation could not remain without influence on the attitude of Roumania and Greece. Count Metternich thinks of the future Serbia as reduced by the loss of all Macedonia and the Morava territory: but as she ought in his view to be capable of life (lebensfahig), he thinks that at least an exit to the Adriatic must be ceded to her. He said he had come more than ever to the view that an independent Albanian state was an Utopia. He believes that the present Albanian territory should be partitioned between Greece, Serbia and possibly Montenegro. He is quite aware that with us there is a general dislike of a Serbian advance to the Adriatic, owing to the Russian influence. But he cannot see what danger there would be in the case of a small and weak Serbia; whereas he would see a far greater danger for AustriaHungary and the Central Powers as a whole, in the establishment of Italy on the East coast of the Adriatic; besides, after all, Montenegro already had a harbour on the Adriatic, so that a Serb-an d ebouche could not be of such far-reaching importance. Count Metternich told me finally that he had had the impression in Sofia that King Ferdinand was against the survival of even a reduced Serbia and would like at all costs to see the Karagjorgjevie dynasty disappear from the surface. Mr. Radoslavov had expressed himself less decidedly, but he (Metternich) thought he could detect in his (Radoslavov's) language, that the Bulgarian Premier would also prefer that there should be in future no independent Serbia. I of course did not mention to Count Mettemich that I was aware of his conversation in Sofia. I only said to him in my replies that so far as I knew, people in Vienna were not of opinion that there could be peace negotiations with Serbia at the present moment. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 7I6 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. Even though the Serbian question does not fall into my present direct sphere, I none the less think that the experiences gathered during my long activity in the Balkans give me the right, and indeed the duty, to express my opinion. I believe that the question whether in future a Serbia should or should not exist, must in the first instance be judged from the general angle of Balkan policy. I should regard it as an error to presuppose that by the foundation of a Great Bulgaria the Southem Slav question as such will have found its solution. A Bulgarian realm stretching from the Marica in the East to the Lake of Ohrid in the West, will still be by no means saturated 1: sooner or later it will want to expand still further. Even now it is clearly recognisable that Bulgaria aims at the Enos-Midia line, and that her aspirations perhaps even go beyond this line: moreover a great Bulgaria will one day have to seize Salonica for itself, and besides in time the western frontier will certainly not suffice, and it will press on to the Adriatic. In short, I believe that this Great Bulgaria in its further development will gradually lose its Bulgarian character and will develop more and more into a, or better said, into the, Southern Slav realm, so that the present King of the Bulgarians will see his goal in becoming Tsar of the Southern Slavs. But such a Great Bulgaria will in my opinion, considered from the standpoint of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, then play a role just as dangerous as the Great Serbia founded at the Treaty of Bucarest. It seems to me not out of the question that this Great Bulgaria also might come into the wake of Russia and pursue under her oegis a far-sighted policy at the expense of the Monarchy. In order to meet this danger, one must therefore try always to restore a certain equilibrium in the Balkans and not allow one of the Balkan states to enjoy, so to speak, sole dominion in the Balkans. This might be attained on the one hand by supporting Greek aspirations so far as possible, especially in South Albania, but on the other hand by allowing the survival of a Serbia, small but still capable of life (lebenlsfdhig). It may be assumed that Serbia under Bulgarian rule would in time be Bulgarised or be swallowed up in the great Southern Slav state, so that the Serbian element as such might disappear. But if an independent, even though small, Serbian state survives, the Serbian element also will be preserved, the antagonism between Serb and Bulgar will thus continue and assert itself to our advantage. If I consider the idea of Count Metternich, as he put it to me, I think it is not to be simply rejected, but on the contrary that it is to be carefully considered whether there would not be a real advan- tage in giving the Serbs a hint that their further existence is desired, and thus enabling them to crawl to the cross, without having to surrender dead or alive. 1 Saturiert was the phrase used by Baron Aehrenthal to express Au Hungary's lack of appetite in I906. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 7I7 I7. COUNT TISZA to FRANCIS JOSEPH,' 4 December, I With regard to my conversation with His Majesty the German Emperor, I feel it my duty, without waiting till my next audience, to report most humbly, that I had noticed, not without anxiety, as a result of recent military events, an atmosphere and point of view which might lead the Emperor William to underestimate the strength of our opponents and the difficulties and dangers still awaiting us, and might lead him to decisions such as would postpone still further the possibility of an advantageous peace. This optimism seems to me all the less justifiable, since from various remarks of Emperor William, I feel bound to draw the con- clusion that in the immediate future (auf absehbare Zeiten) there is no prospect of breaking through the Western front or of a decisive victory in France, and thus the only possibility of bringing at least one of our enemies to his knees is eliminated (entf/llt). A defensive, however effective, on the two main theatres of war, cannot produce among our enemies the necessity (Zwang) of making peace: and it depends in the first instance upon the moderation of our war aims and purposes, whether, under the impression of our successes in other theatres of war, the intention of making peace ripens among the Entente or not. A truth which we ought to neglect all the less because despite all heroism and glorious successes exhaustion must set in sooner with us than with the enemy. I carefully avoided treating the question in such a way as would infer our war weariness or weakness and might have led to disagreeable comparisons between our force and that of the German Empire, but I tried to bring His Majesty to a juster estimate of the enemy reserves and of the toughness (Zdhigkeit) of the English will to warunhappily without any real effect. In any case I feel bound to point out the need of a very close intimate contact with the responsible leaders of German policy, in order that Emperor William may be permanently influenced in the sense of moderation. The intoxicating effect of our last successes also showed itself in His Majesty's remarks about the Balkans. With regard to Emperor William's fundamental views, I could only note with pleasure the change which they show in our favour and could listen with a certain satisfaction to his eloquent plaidoyer (schwangvolle Parteinahme) for Bulgaria and its permanent attachment to the Central Powers, and also his contemptuous judgment on Roumania, who could only be brought back to our sphere of influence and kept there, by fear of us and of Bulgaria-all this in the same room, in which barely a year and a half ago the first attempts were made to win over His Majesty from the very opposite point of view to this just estimate of the Balkan situation. 1 Since published in O5sszes Munkai, III., p. 296. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 7I8 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. Moreover the idea of a Serbian separate peace, coupled with the abandonment of Albania to Serbia, had entirely vanished-though only a few weeks ago, even after the decisively favourable turn in the Serbian campaign, it was strongly advocated not only by the diplomatists, but also by General Falkenhayn. On the contrary, His Majesty put to me in his usual eloquent way, that only a complete dissolution of Serbia and the annexation of what was left of it could bring a satisfactory solution of the Serbian problem. This emphatic support of action so nearly affecting the life of the Monarchy leads me to deal with this matter more closely, and to ask Your Majesty's most gracious permission to submit most humbly my views. I believe I may begin by taking for granted that Serbia will lose the eastern and southern portion promised to Bulgaria and by our annexation of its north-west corner will be completely cut off from the Save and the Danube. I should thus imagine a territory whose south-west frontier, starting from the middle Drina, would join the new Bulgarian Morava frontier not far from the Danube, in which connection military considerations of a favourable strategic line must of course be borne in mind, but an attempt must be made not to make too big the territory to be conquered by us, and to limit it in the main to the fertile river valleys. Serbia would have to suffer a third diminution by the cession of the Albanian territories assigned to her in the London Protocol. Albania would receive back the important Albanian districts taken from her both by Montenegro and by Serbia, and would thus recover economic and ethnographic conditions for national development. Bound up with the exclusion of Montenegro from the Adriatic and the establishment of territorial continuity between Albania and Montenegro, the experiment of an independent national existence must be permitted to the Albanian people, in which connection we must aim mainly at the complete elimination of Italian or Serbian influence there. As to the results of this attempt, it would be premature to express an opinion. It may equally well lead to a more or less ordered national Albanian state, or to the union (Angliederung) of Albania to another state friendly to us. For the further state existence of Serbdom there would thus remain Montenegro, reduced and cut off from the sea, and also the eastern part of middle Serbia-a poor and mainly barren mountainous district cut off from the waterways, shut in between powerful neighbours, economically entirely dependent on the Monarchy. It is my conviction that from the standpoint of our well-conceived interests it is decidedly better not to annex these districts, but under forms such as satisfy their economic interests to bind them economically anI militarily to the Monarchy. In this I also start from the standpoint that we should block the path to a renewal of the Pan-Serb danger,- only I ask whether the This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 7I9 incorporation of Serbia and the union of almost the whole Serbian race is really the most effective means to the attainment of this aim. Very deserving of attention is the circumstance that in the experience of people in close contact with our Serbs, this wish is already showing itself in strongly nationalist Serb circles, even now immediately after the Serbian defeat. The same people who were enthusiastic for a Great Serbia and whose attitude, in the event of a victorious Serbian inroad, would hardly have been free from Irredentist infection, seem now to wish the annihilation of Serbia and the annexation of all Serbian territories, in the just expectation that an ever closer union (Zusammenschluss) of the Serbian inhabitants of Austria, Bosnia, Croatia, Hungary proper and the newly acquired territories would only be a question of time, and that the Serbian element sooner or later would represent a concentrated power in the South of the Monarchy, with which it will be necessary to reckon, and whose national aspirations will assert themselves. The task of shaping conditions properly in Bosnia is in itself a hard test for the centripetal forces of the Monarchy. Here Austria. would hardly enter into the reckoning. In the well-understood interest of her loyal elements it would be most advisable to diminish the number of her Southern Slav subjects: to increase them would be to render the already difficult situation of the Austrian Germans quite impossible. Consequently the task of solving the Southern Slav problem with due regard for the internal unity of the Monarchy and its capac for action as a Great Power, falls in the first instance upon the Hungarian state. Certainly a heavy burden, which must fill with grave cares all those responsible for the fate of their fatherland, even if the Southern Slav population is only augmented by the incorporation of Bosnia and a small part of northern Serbia. If the i,6oo,ooo to 2,000,000 Serbs of what remained of Serbia and Montenegro were to be added, that would not only alter the numerical balance (Krdfteverhdltnisse), but would also kindle the national aspirations and hopes of the already incorporated Serbs to such a degree that the Hungarian State would be in danger of losing its firmly knit unitary stamp (Geprdge). But if those elements which are centrifugal, or if not hostile, at least indifferent to the state, win the upper hand, and if Hungary also loses the character of a living organism blending all its parts into a single whole, then the Monarchy has lost the greatest force which had rendered it possible to stand victoriously the gigantic test of this World War. And with all emphasis I must take my stand against the illusion that the incorporation of all the Serbs in the Monarchy would at least put an end to Russian machinations and to Serbian intrigues against the Monarchy, and that in the worst case by sacrificing the This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 720 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. Hungarian national state Serbdom at least might be permanently won over. The experiences of many decades provide proof that to belong to the Monarchy neither stifles the separatist aims of hostile elements nor has prevented Russia from deliberately carrying her work of destruction into their midst; and the present war has with brutal force opened the eyes even of the blindest. The incorporation of all Serbs would certainly not kill the Great Serbian idea: on the contrary the increase of the Serbian subjects of the Monarchy, the union of all Serbs under the sceptre of one ruler, the strengthening of the Serbian element as against the other races, the creation of a great majority of Orthodox Serbs against the Croats, would be so many factors in the Great Serbian agitation. Every concession made to nationalism would be a new weapon in its hand in the struggle for the final goal, separation from the Monarchy. I believe myself fully justified in recommending the opposite path to this development-thereby assigning to the remainder of the Serbs, reduced in numbers and cut off from the world, a separate state existence: and in that case the question can for the present remain open, whether these territories are to be kept apart as Montenegro and Serbia, or unified under the Montenegrin reigning family or perhaps under a new ruler friendly to the Monarchy, and to receive a new organisation. In any case, however, the whole territory should be bound by economic and military ties to the Monarchy. Its inclusion in the customs area would not noticeably affect home production, but on the other hand would be the greatest possible boon for the territory in question and would make its whole existence and future economic development dependent on our good will. We should thus have achieved their dependence to a sufficient degree, without giving them any share in the political life of the Monarchy and increasing the Serb element inside the Monarchy. This isolation of the Serbs living outside our frontiers from our own Serb population would have to be promoted still further by the incorporation in Hungary proper of the Serbian districts to be annexed. These would for a presumably longish period have to be administered on autocratic lines, and at the same time colonisation of Hungarian and German elements on a grand scale (grosszigig) would have to be begun, so that they would maintain an altogether reliable patriotic majority and would have to serve as a wedge between the Serbian State and the Serbian population of Slavonia and Southern Hungary. Hand in hand with a well-planned (zielbewusst) augmentation of the Hungarian and German settlements in Syrmia, in the Backa and in the Banat, the iron wall protecting our southern frontier and keeping off Great Serbian infection from our native Serbian population, would grow ever stronger. With these remarks I think I have proved that the path proposed This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms AUSTRO-GERMAN PLANS FOR SERBIA. 72I by me is the better one, from the standpoint of the Monarchy's own permanent interests. In conclusion, however, it should be also pointed out that this path is in all probability the only passable one. To this mangling (Verstiimmelung) of the Serbian state, alike territorially and as regards its sovereignty, Russia will certainly submit very reluctantly. The complete annexation of Serbia would be a blow and a humiliation for Russian policy, to which Russia would hardly ever consent without a complete defeat-a complete defeat which certainly does not belong to the most probable events. Unless we want to render it necessary for us to fight out a war a outrance with Russia, and ourselves to block the way to an honourable and advantageous peace, we must avoid putting forward war aims with regard to Serbia, such as go far beyond a due regard for our own safety or the military probabilities of our heroic struggle with a superior force. I8. COUNT TIsZA to. BARON BURIAN. Budapest, 30 December, I9I5. (Strictly secret.)' This Memorandum was an answer to one of the C.G.S., Baron Conrad, on the relation between " foreign policy and military leadership." T'sza argues that " of a complete success we can really only speak in the Balkans, and even there only after the Entente's expulsion from Salonica," and that there can be no question of " a blow at the heart" rof Russia. There is no hope of bringing France or England to theil knees: Italy can only be reduced by a victorious offensive. In short, -a good defensive position, but no chance of complete victory over the main enemy-not a position for fixing war aims " according to our good pleasure'" (nach Gutdiinken). Great caution is needed in proclaiming our desire for annexation. He then deals in detail with the Serbian question. " The formula of a solution of the Serbian or Southern Slav question within the framework of the Monarchy may be variously interpreted. If by it were meant that steps are to be taken to check Serbian des gns against the integrity of the Monarchy and if Serbia's fate is to be regulated in such a way as to make her harmless, nothing could be said against this. But if it means the incorporation of all Serbs in the Monarchy, I must oppose this with the greatest emphasisneedless to say, from the standpoint of the interest of the whole Monarchy. "That this coincides with the properly understood Hungarian national interest, requires in my opinion no further proof. The existence of the Hungarian national state is altogether interwoven with the Monarchy's position as a Great Power. . . . This identity was the fruitful basis of the Ausgleich of I867: it fully proved itself in the Balkan crisis of the seventies and eighties and has undergone I Full text in Grof Tisza Istvain, Osszes Munkdi, III., p. 337. 3 A This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 722 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. the test of fire in the present struggle. . . . Not merely have the loyalty and heroic sacrifice of the Hungarian race been used to help the Monarchy in the trials of the first half of the war . . . but also its constructive power, which unites the zo million inhabitants of Hungary in a living organism. . . . Unless one is quite blinded by prejudice, one cannot after the experience of this war dispute that not only the energy of the Hungarians in an ethnic sense, but the firm framework of the Hungarian national state, is the main support of the whole Monarchy's power. If it is not desired to rob the whole structure of the Monarchy of its strongest support and conjure up dangers worse than any outside enemy, then one must not overlook this point of view in any decision regarding Serbia. " The claim that the incorporation of all Serbs in the Monarchy is the only effective way of dispelling the Serbian danger, rests in my opinion on a double error-(i) that the annexation of Serbia would really remove the Great Serbian danger, and (2) that a Serbdom living its own separate state life could not be brought within the Monarchy's orbit and made harrnless for it. . . . For the annexed Serbs the Monarchy will remain the arch-enemy as much after as before the annexations, and to increase the number of our Serbian subjects by several millions will provide a greater sounding board for Serbian nationalist agitation and raise its hopes and claims. " The saying that the Monarchy is 'territorially saturated' was no phrase ad usum Delphini . . . but expressed the truth that the proportion of centrifugal to centripetal forces in the Monarchy was already highly unfavourable and could not brook an increase in the former. The glorious events of this war must not let us abandon this accurate estimate.... Austria, he went on to argue, could not cope with an increase in the number of hostile elements in the South, and such an experiment would have lamentable consequences in the Austrian state. " Under these circumstances the centre of gravity in the Serbian question falls upon the lands of the Hungarian Crown, and only harmonious cooperation between Hungarians and Croats can assure success. If the Croats were hostile, Hungary would not be strong enough to digest all the Serbs, while to assign all the Serbs to Croatia would be to hand over the Croats to a Serbian majority and would lead in a few decades to their absorption. It is a matter of life and death for the Croats to rely on Hungary in the struggle against Panserbism, and not to take in more Serbs than they can manage. ... "If we want to influence the Serbs of Bosnia, Croatia and South Hungary in a patriotic sense and to improve the situation there, we both have enough to do. An incorporation of several millions in Serbia and Montenegro would confront us with an impossible task . . .and compromise the Monarchy's future. . . On the other hand what remains of Serbia and Montenegro could be transformed in such a way as to give the Monarchy a handle for successfully checking This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MONTENEGRO AND AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. 723 hostile currents. If we cut off from the Serbian state all that was promised to Bulgaria, if we give to Albania the parts of Serbia and Montenegro which belong naturally to her, and if we cut off Montenegro from the Adriatic, then it is only necessary for us to annex the northwest corner of Serbia, in order to cut her and Montenegro off from the outer world and bring them into complete economic dependence on the Monarchy. " There would then remain one or two poor, utterly dependent petty states (Staatchen), for which the good will of the Monarchy would be an absolutely vital question, and which would be brought into permanent dependence by far-reaching trade concessions and military arrangements. " While favouring this solution . . . I would add that I regard any further solution as not only harmful, but also impracticable. The annexation of Serbia would prove to be as much an obstacle to peace as that of Belgium, and the Monarchy must submit to leaving Serbia a certain state existence, just as Germany in the case of Belgium. " It is not the first time that this question has occupied the competent factors of the Monarchy. It was raised by the Hungarian Government before the war and resulted in the unanimous resolution of the Joint Council of Ministers on I9 July, I9I4, by which Serbian territory was only to be annexed within the limits of a rectification of frontier. This decision was a condition of the Hungarian Government's consent to the dispatch of the Note to Serbia, it was put forward as such by me and accepted by all present. It thus forms a solenm admission binding upon all competent factors, such as can only be annulled or altered by unanimous resolution. " Though I feel bound to adhere to this fundamental principle, I cannot resist the grounds which seem to render a certain revision of this decision expedient. The extent of the Serbian territory to be united with the Monarchy may be somewhat greater than was then contemplated, and certain questions connected with the fate of the annexed territory and of what remains of Serbia would have to be cleared up, and on this the military authorities to be established there have every right to be informed. II. MONTENEGRO AND AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. I9. COUNT TARNOWSKI to BARON BURIAN. No. I449. Sofia, II November, I9I5. Transmits a telegram from Crown Prince Danilo of Montenegro to Baron de Kruyff, couched in the following terms: Pouvez-vous pas penetrer veritables intentions des Centrales 'a l'egard de Montenegro, Serbie: faites comprendre si possible Kaiser, annexion de Montenegro serait boulet intrainable, causant troubles continuels; convainquez Vienne avantages reels, grand interet pour Centrales conserver toujours un etat serbe leur reconnaissant, donc attache, pour pouvoir, cas echeant, contrebalancer velleites, aspira- This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms 724 THE SLAVONIC REVIEW. tions etendues Bulgarie devenant probablement bientot trop exigeante. Nous pourrons assurer cet e'quilibre, quand le Montenegro serait aggrandi par partie Serbie, extremite Dalmatie, nord Albanie, dej a occupes, faisant ainsi un seul royaume serbe. Dans ce cas nous serons a meme et disposes faire deriver retraite serbe vers I'Albanie, et pas admettre troupes serbes, non plus troupes allies sur notre territoire et accepter traites avec Centrales sur bases indiquees. Repondez aussi vite que possible, et cas affirmatif agissez sans perdre aucun temps. 20. COUNT TARNOWSKI to BARON BURIAN. No. I474. Sofia, i6 November, I9I5. (Summary.) Reports a conversation with Baron de Kruyff, a kinsman of Crow Prince Danilo of Montenegro. De Kruyff spoke of a Montenegrin request for peace. King Nicholas had been driven into war by the Serbian party in Montenegro. She had always tried to show as little enmity as possible towards the Monarchy, and had already in July, I9I5, tried to open peace negotiations. The interests of Montenegro and Austria-Hungary must henceforth run parallel. De Kruyff was ready to go to Vienna and Switzerland, to see Prince Danilo. 2I. BARON MITTAG to BARON BURIAN. No. I562. Sofia, 5 December, I9I5. Has learnt from Baron de Kruyff that King Nicholas is in order to meet the Duke of Aosta, and King Peter of Serbia if he can get there. 22. BARON BURIAN to COUNT THURN. NO. 5788 pro domo. I7 December, I9I5. Reports desire of Mr. V. Petrovic for conversation with respons representative of Austria-Hungary, and refusal in view of his antecedents. " For this refusal on my part the decisive factor is not merely the person of the said Serbian politician, but above all the consideration that it hardly seems expedient to deal with individual Serbs whose following is more or less restricted: there are at present at our disposal wider and more passable paths by which to establish contact with the people and get to know its wishes and needs." 23. On 26 November Vienna insisted upon being assured of King Nicholas's " knowledge and sanction " as a condition sine qua non of negotiation. 24. On I7 December Baron de Kruyff wrote to Count Forgach, announcing that Crown Prince Danilo proposed visiting Switzerland. 25. On 8 August, I9I8, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Office addressed to the War Office a communication (2I. 38I3), stating that between i April, I9I6, and 31 March, I9I8, it had disbursed I14,000 kronen (&4,75o) on behalf of the late Prince Mirko of Montenegro. It appends full details of twenty-one separate payments (gegen Ersatz vom Kriegsminister) and asks for repayment, showing the various receipts. This content downloaded from 132.174.250.192 on Thu, 03 Feb 2022 21:42:44 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms