SECTION 1 SEGMENTAL PHONETICS

Phonetics as a part of the science of linguistics.

In linguistics, function is usually understood to mean discriminatory

function, that is, the role of the various elements of the language in the

distinguishing of one sequence of sounds, such as a word or a sequence of words,

from another of different meaning. Though we consider the discriminatory

function to be the main linguistic function of any phonetic unit we cannot ignore

the other function of phonetic units, that is, their role in the formation of syllables,

words, phrases and even texts.

Phonetics is an independent branch of linguistics like lexicology, grammar

and stylistics. It studies the sound matter, its aspects and functions.

Phonetics is connected with linguistic and non-linguistic sciences: acoustics,

physiology, psychology, logic, etc.

The connection of phonetics with grammar, lexicology and stylistics is

exercised first of all via orthography, which in its turn is very closely connected

with phonetics.

Phonetics formulates the rules of pronunciation for separate

sounds and sound combinations. The rules of reading are based on the relation of

sounds to orthography and present certain difficulties in learning the English

language, especially on the initial stage of studying.

Through the system of rules of reading phonetics is connected with

grammar and helps to pronounce correctly singular and plural forms of nouns, the

past tense forms and past participles of English regular verbs, e. g. [d] is

pronounced after voiced consonants (beg — begged), [t] — after voiceless

consonants (wish — wished) . It is only if we know that [s] is pronounced after

voiceless consonants, [z] after voiced and [iz] after sibilants, that we can

pronounce the words books, bags, boxes correctly. The ending - ed is pronounced

[id] following [t] or [d], e. g. waited [weitid], folded ['f«uldid]. Some adjectives

have a form with [id], e. g. crooked ['krukid], naked ['neikid], ragged ['rQgid].

One of the most important phonetic phenomena — sound interchange — is

another manifestation of the connection of phonetics with grammar. For instance,

this connection can be observed in the category of number. Thus, the interchange

of [f— v], [s — z], [T — D] helps to differentiate singular and plural forms of such

nouns as: calf— calves [f—v], leaf— leaves [f— v], house — houses [s — z].

Vowel interchange helps to distinguish the singular and the plural of such

words as: basis — bases ['beisis — 'beisi:z], crisis — crises ['kraisis — 'kraisi:z],

and also: man — men [mᴂn — men], foot —feet [fut — fi:t], goose — geese [gu:s

— gi:z], mouse — mice [maus — mais].

Phonetics is also connected with stylistics; first of all through intonation and

its components: speech melody, utterance stress, rhythm, pause and voice tamber

which serve to express emotions, to distinguish between different attitudes on the

part of the author and speaker. Very often the writer helps the reader to interpret

his ideas through special words and remarks such as: a pause, a short pause,

angrily, hopefully, gently, incredulously, etc.

If the author wants to make a word or a sentence specially prominent or

logically accented, he uses graphical expressive means.

Phonetics is also connected with stylistics through repetition of words,

phrases and sounds. Repetition of this kind serves the basis of rhythm, rhyme and

alliteration.

The repetition of identical or similar sounds, which is called alliteration,

helps, together with the words to which they belong, to impart a melodic effect to

the utterance and to express certain emotions.

Onomatopoeia, a combination of sounds which imitate sounds produced in

nature, is one more stylistic device which can serve as an example of the

connection between phonetics and stylistics. E. g.: tinkle, jingle, clink, ting, chink;

chatter, jabber, clatter, babble; chirp, cheep, twitter, chirrup; clap, dab, smack;

crash, bang.

The study of phonetic phenomena from the stylistic point of view is

phonostylistics. It is connected with a number of linguistic and non-linguistic

disciplines, such as: paralinguistics, psychology, psycholinguistics, sociology,

sociolinguistics, dialectology, literary criticism, information theory, etc.

Phonetics as a part of social sciences.

Further point should be made in connection with the relationship between

phonetics and social sciences. Language is not an isolated phenomenon; it is a

part of society. No branch of linguistics can be studied without taking into

consideration at least the study of other aspects of society. In the past two decades

we have seen the development of quite distinct interdisciplinary subjects, such as

sociolinguistics (and sociophonetics correspondingly), psycholinguistics,

mathematical linguistics and others. As their titles suggest, they are studied from

two points of view and thus require knowledge of both.

Sociophonetics studies the ways in which pronunciation functions in society.

It is interested in the ways in which phonetic structures vary in response to

different social functions. Society here is used in its broadest sense, it includes

such phenomena as nationality, regional and social groups, age, gender, different

situations of speaking - talking to equals, superiors, on the “job”, when we are

trying to persuade, inform, agree and so on. The aim of sociophonetics is to

correlate phonetic variations with situational factors. It’s obvious that these data

are vital for language learners who are to observe social norms and to

accommodate to different situations they find themselves in.

One more example of interdisciplinary overlap is the relation of linguistics

to psychology. Psycholinguistics covers an extremely broad area, from acoustic

phonetics to language pathology, and includes such problems as acquisition of

language by children, memory, attention, speech perception, second-language

acquisition and so on. Phonosemantics studies the relations between the sound

structure of a word and its meaning. There is some data proving that the sounds

that constitute a word have their own “inner” meaning, which causes certain

associations in the listener’s mind. For example, close vowels produce the effect of

“smallness”, and voiceless consonants sound more “unpleasant” and “rude” than

their voiced counterparts, etc. Some sounds are associated with certain colours.

These data may be helpful in teaching, for example, “tying” together the sound

structure of a word and its meaning, thus facilitating the process of memorising

new words.

Scientists have always been interested how children acquire their own

language without being taught. They hope that these data might be useful in

teaching grown-up people a foreign language, too.

Pragmalinguistics is a comparatively new science, which studies what

linguistic means and ways of influence on a hearer to choose in order to bring

about certain effects in the process of communication. Correspondently the domain

of pragmaphonetics is to analyse the functioning and speech effects of the sound

system of a language.

Phonetics is closely connected with a number of other sciences such as

physics (or rather acoustics), mathematics, biology, physiology and others. The

more phonetics develops the more various branches of science become involved in

the field of phonetic investigation. Phonetics has become important in a number of

technological fields connected with communication.

Phoneticians work alongside the communication engineers in devising and

perfecting machines that can understand, that is respond to human speech, or

machines for reading aloud the printed page and vice versa, converting speech

directly into printed words on paper. Although scientists are still dissatisfied with

the quality of synthesized speech, these data are applied in security systems,

answering machines and for other technical purposes.

How to teach Phonetics in class.

Pronunciation in the past occupied a central position in theories of oral

language proficiency. But it was largely identified with accurate pronunciation of

isolated sounds or words. The most neglected aspect of the teaching of

pronunciation was the relationship between phoneme articulation and other

features of connected speech. Traditional classroom techniques included the use of

a

phonetic

alphabet

(transcription),

transcription

practice,

recognition/discrimination tasks, focused production tasks, tongue twisters, games,

and the like.

When the Communicative Approach to language teaching began to take over

in the mid- late - 1970s, most of the above-mentioned techniques and materials for

teaching pronunciation at the segmental level were rejected on the grounds as

being incompatible with teaching language as communication. Pronunciation has

come to be regarded as of limited importance in a communicatively-oriented

curriculum. Most of the efforts were directed to teaching supra-segmental features

of the language -rhythm, stress and intonation, because they have the greatest

impact on the comprehensibility of the learner's English

Today pronunciation instruction is moving away from the segmental/suprasegmental debate and toward a more balanced view [Morley 1994]. This view

recognizes that both an inability to distinguish sounds that carry a high functional

load, e.g. list— least, and an inability to distinguish supra-segmental features (such

as intonation and stress differences) can have a negative impact on the oral

communication - and the listening comprehension abilities - of normative speakers

of English.

Teaching pronunciation with

phonemic symbols

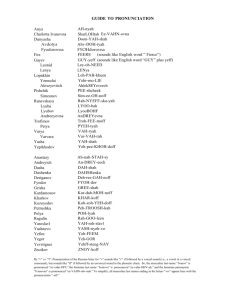

The letters of the alphabet can be a poor guide to pronunciation. Phonemic symbols, in

contrast, are a totally reliable guide. Each symbol represents one sound consistently. Here

are five good reasons why students should know phonemic symbols.

Students can use dictionaries effectively. The second bit of information in

dictionaries for English language learners is the word in phonemic symbols. It comes

right after the word itself. Knowing phonemic symbols enables students to get the

maximum information from dictionaries.

Students can become independent learners. They can find out the pronunciation of a

word by themselves without asking the teacher. What is more, they can write down

the correct pronunciation of a word that they hear. If they cannot use phonemic

symbols for this, they will use the sound values of letters in their own language and

this will perpetuate pronunciation errors.

Phonemic symbols are a visual aid. Students can see that two words differ, or are

the same, in pronunciation. For example they can see that 'son' and sun' must be

pronounced the same because the phonemic symbols are the same. They can use

their eyes to help their ears and if they are able to hold and manipulate cards with

the symbols on, then they are using the sense of touch as well. The more senses

students use, the better they will learn.

Phonemic symbols, arranged in a chart, are part of every student's armoury of

learning resources. Just as they have a dictionary for vocabulary and a grammar

book for grammar, so they need reference materials for pronunciation: the phonemic

symbols and simple, key words that show the sound of each symbol.

Although speaking a language is a performance skill, knowledge of how the

language works is still of great value. Here is another question to ask students: How

many different sounds are there in English? Usually, students do not know.

Phonemic symbols on the wall in a classroom remind them that there are 44. Even if

they have not mastered all of them, they know what the target is and where the

problems are. The chart is a map of English sounds. Even with a map, you can get

lost but you are better off with a map than without one.

Is it important for teachers to know the phonemic symbols?

To be frank, yes. Every profession has specialist knowledge that is not widely known

outside the profession. If you are a doctor, you will be able to name every bone in the

human body, which most people can't do. If you are a language teacher, then you know

phonemic symbols, which most people don't. Students can learn these symbols by

themselves and one day you might meet a student who asks you to write a word on the

board using phonemic symbols. It is best to be prepared.

Is it difficult to learn phonemic symbols?

Absolutely not. 19 of the 44 symbols have the same sound and shape as letters of the

alphabet. This means that some words, such as 'pet', look the same whether written with

phonemic symbols or letters of the alphabet. That leaves just 25 to learn. Compare that with

the hundreds of different pieces of information in a grammar book or the thousands of

words in even a small dictionary. It is a very small learning load. Moreover, it is visual and

shapes are easy to remember. Anyone who can drive is able to recognise more than 25

symbols giving information about road conditions. Even if we go beyond separate, individual

sounds and include linking, elision and assimilation, there is still a limited and clearly

defined set of things to learn.

Integrating pronunciation into

classroom activities

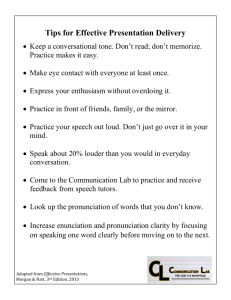

In my work as a teacher trainer I have been surprised at how often experienced teachers

are reluctant to tackle pronunciation issues in class. I can think of at least two reasons why

pronunciation tends to be neglected: firstly, the lack of clear guidelines and rules available

in course books, and secondly the fact that isolated exercises once a month do not seem to

have much of an effect. This is not surprising, however; like all other areas of language

teaching, pronunciation needs constant attention for it to have a lasting effect on students,

which means integrating it into daily classroom procedures. I find that addressing issues

regularly during the language feedback or group correction stage of a lesson helps to focus

learners' attention on its importance and leads to more positive experiences.

Using student talk to teach pronunciation

Word stress

Vowel sounds

Diphthongs

Weak forms

Sentence stress

Conclusion

Using student talk to teach pronunciation

Pronunciation work can be kept simple and employ exercises which are both accessible

and enjoyable for students, whatever their level. Whenever students do a freer speaking

activity, the main aim is usually for them

to develop their spoken fluency in the language. However, the activity also serves to work

on students' accuracy through the feedback we give them on their use of language.

When my students do such a group or pair work activity at any level I listen in and

take notes which are divided into three areas of language: pronunciation, grammar

and lexis. Within the latter, as well as unknown lexis I will also include areas such as

register, function, set phrases…and within the former I will include notes on any area

of pronunciation that leads to miscommunication. This includes diphthongs, vowel

sounds (including weak forms), consonant sounds, word stress and sentence stress.

All of these areas can be dealt with quickly and efficiently by having some simple

exercises ready which require nothing more than the board and a basic knowledge

of the phonemic chart.

If learners are introduced to the phonemic chart one phoneme at a time, it can be

introduced from beginner level and students are quick to appreciate its value. A rule

for when 'ea' is pronounced /e/ (head) and when it is pronounced /i:/ (bead) will not

necessarily aid production, whereas the activities I propose here will. Once your

students get used to the exercises, pronunciation work becomes even more efficient

and, dare I say it, effective.

Word stress

Here is a simple exercise I repeat regularly for work on word stress and individual sounds.

I hear a pre-intermediate learner say: 'I suppose (pronounced with stress on first

syllable) I will see her tonight'. The listener doesn't understand because of the

mispronunciation and asks the other student to repeat until finally they write it down

and we see what the word was.

After the activity, on the board I put a column with two bubbles to represent word

stress, the first small, the second much larger. I write 'suppose' under the bubbles

and drill it before asking students to think of other two-syllable words with secondsyllable stress.

I get 'outside', 'today', 'below' and 'behind', which I accept as correct before asking

for verbs only. I then get 'accept', 'believe', 'forget'….and these go in the same

column.

If a student asks for rules during this exercise, in this case 'Do all 2-syllable verbs

have this stress pattern?', for example, I either ask them to think of examples that

contradict their rule to give myself time to consider it or I tell them we will look at

rules for this the following lesson. As a general rule I find that this procedure

encourages learner autonomy by having learners form their own hypotheses which

are then confirmed or disproved by the teacher in the following lesson.

Vowel sounds

I hear a pre-intermediate learner say: 'Not now because he is did (dead)'.

After the activity, on the board I draw a column with the heading /e/. In this column I

write the word 'dead' and have students repeat it. I then ask for examples of words

which rhyme with this, which students find easy ('red', 'bed', etc.).

I do not write these, however. I then ask for words which rhyme and have the same

vowel spelling, i.e. 'ea'. I put students in pairs or groups to think of words, giving

myself some thinking time, too. In this case, depending on the level I will get 'head',

'bread', 'read', 'lead',… and we end up with an extendable list of words with the same

spelling and sound.

It is the cognitive work of trying to think of similar words, writing them down and their

organisation into columns that helps learners retain sounds and spellings, rather

than their simply revising the lists. This is why all students should be encouraged to

copy the list into their notebooks.

If the classroom allows it, it's also a great idea to have students pin posters with

sound columns up on the wall and add to them whenever a new item comes up for

that sound, particularly if it is a strange or different spelling.

The idea is to get a basic poster with a phoneme at the top and various columns with

different spellings.

/e/

'e' 'ea' 'ai'

bed dead said

pen head

Diphthongs

I hear an intermediate learner say: 'I didn't find (pronounced / f i: n d /) it anywhere'.

I make a column with /ai/, drill 'find' and my students give me 'fight', 'bike', 'buy',

'eye','my', etc. for the sound.

I accept these without writing them and then encourage students to think of other

words spelt like 'find'. I get 'mind' and 'kind'.

There may be only one or two for any given pattern. If I have thought of any other

words myself I add them to the column, ensuring that they are not obscure words or

too high for this particular level (in this case I might choose to introduce 'bind' and

'grind', but probably not 'rind' or 'hind').

Weak forms

I hear an elementary learner say: 'I will buy vegetables (pronouncing 'table' at the end)'. I

note that this is also an opportunity to work on word stress.

I make a column with a schwa, and drill 'vegetable', marking the word stress.

With an elementary class there is a case for simply teaching this point rather than

eliciting known words, so I point out the number of syllables and the stress on the

beginning of the word, explaining that this makes the final syllable weak and not

pronounced as the word 'table'.

I add to the list 'comfortable' and 'presentable' as further examples, but avoid adding

more so as not to overwhelm students at this level.

For the second example I point out that the stress is on the second syllable. I can

think of objections teachers have made to my suggesting this, such as students'

confusion at the lack of a steadfast rule or the non-uniformity of the examples, for

example, but to cater to this merely serves to reinforce students' belief that a

language always obeys a strict set of rules. In my experience this approach is not a

useful one. The only way to learn these fundamental pronunciation points is to notice

them, note them down and practise them regularly.

Sentence stress

I use fluency drills to work on sentence stress. I hear an intermediate learner say:

'He told me I couldn't have

a holiday' (bold words are stressed). This causes confusion due to the stress being placed

on the wrong words

in the sentence, i.e. the pronouns, or grammar words, as opposed to the content words.

1. The activity is simply a choral drill, but of the whole sentence and maintaining an

English rhythm. 'He told me I couldn't have a holiday'.

The trick here is not to over-exaggerate on the stressed words, but keep the stress

and rhythm natural. Think in terms of modelling a rhythm, rather than a stress

pattern. Using gesture like the conductor of an orchestra or tapping on the board to

show the rhythm is especially helpful for students who cannot hear it easily.

Admittedly, this latter exercise on sentence stress does seem to take longer to have an

effect, but if highlighted early on and practised relatively often, students do seem to

internalise how English stress differs from their own language and helps overcome what in

later stages of learning becomes a fossilised way of speaking. Sentence stress causes

more communication problems for a fluent speaker than any number of grammatical errors.

Conclusion

One of the beauties of using student speech for pronunciation work is that it directly

addresses students' problems. I have attempted to provide a couple of very simple

exercises here to help teachers integrate pronunciation into their classes on a regular basis.

Regular work in this area helps learners to develop their own hypotheses and gut-feeling for

English pronunciation, something experts and researchers have long emphasised as an

essential skill of a good language learner.

Practical assignment. Phonetics as a part of linguistic and social sciences.

Practical assignment. Teaching phonetics in class.

1. Read the description of the Pronunciation whispers game. State the aim of

the game. Practice the game in class.

Procedure

Demonstrate the game of 'whispers'. Separate the class into two teams and

have them stand or sit in a row one behind the other. The student at the front

should be able to write on the board or have a pen and piece of paper in front

of them.

Dictate a word or sentence suitable for the level and age that you're teaching

to the two students at the end of each line.

They then whisper the sentence to the person in front of them who in turn

does the same. This is repeated until it reaches the two students at the front

of each line who then write what they heard on the board. The aim is for

the word or sentence to be the same as the teacher's.

Correct any mistakes. Points can then be awarded both for which team was

first and for which team was the most accurate.

Now write words or sentences on the board depending on their stress

pattern. Make two sets for each group. For example if dealing with the stress

of individual words such as countries you might write the following (without

the answers in brackets):

0O (Japan)

O0 (Thailand)

00O00 (Indonesia)

0O00 (Australia)

O (Spain)

O00 (Mexico)

Now without drilling any pronunciation beforehand repeat the activity as

above but now students must write the dictated word next to the stress

pattern.

Extension and adaptations

Dictate only the word or sentence and students write the stress pattern.

Dictate the stress pattern and students write the word

Do the same activity as a pair dictation. Dictate a sentence but say one word

with the incorrect stress pattern. Students dictate and write down the word

pronounced incorrectly.

2. Read the description of the Sound and spelling correspondence game. State

the aim of the game. Practice the game in class.

The chart can be used to highlight both patterns and variations in sound and

spelling correspondence.

As a discovery activity to help learners notice the effect of adding an 'e' to the end of

a word, you could give the learners some of the words from the following list:

cap cape

matmate

pin pine

not note

pet Pete

kit kite

sit site

win wine

hat hate

cut cute

Learners use the chart to help them write the phonemic transcription for each word,

checking with a dictionary if necessary. The teacher then asks them to formulate a

general 'rule' for the effect of adding an 'e' to the end of a word. (It makes the vowel

sound 'say its name', i.e. the 'a' in 'cape' sounds like the letter A as it is said in the

alphabet.)

It is not advisable to over-emphasise the irregularity of English spelling, given that

80% of English words do fit into regular patterns. However, speakers of languages

such as Spanish, Italian or Japanese where there is a very high correspondence

between sound and spelling may need to have their attention drawn to the different

possibilities for pronunciation in English.

One way of doing this is to give them a list of known words where the same letter or

combination of letters, normally a vowel or vowels, represent different sounds.

Learners will have at least some idea of how these words are pronounced, and can

categorise the words according to the sound represented, using the chart to help

them, before holding a final class check. For example, you could give learners the

following list of words including the letter a, which they categorise according to how

the as are pronounced. Where the word contains more than one a with different

sounds, underline which a you want them to use to make their categorisations.

3. Read the description of the Telephone number pronunciation game. State

the aim of the game. Practice the game in class.

This activity practises discrete vowel sounds. It practises both speaking and listening skills.

It works well in pairs or in groups and usually generates lots of fun.

Procedure

Draw the face of a mobile telephone on the board.

Elicit the numbers and then dictate a number to the students.

One by one, erase the numbers and replace them with the words on the worksheet,

drill the pronunciation as you do this.

Dictate another number to the students this time saying the words and not the

numbers.

Students then work together as a class, in groups or in pairs and repeat the

procedure with their own telephone numbers.

If they have given their real numbers, you could get the students to actually phone

the number and check.

Adaptation

To practise scan reading skills.

Give out a classifieds section of a newspaper.

Students choose a number and dictate it using the procedure above.

Students then scan the newspaper page to find the corresponding classified and

either write it on the board or shout it out. This could be done as a team game.

4. Read the description of the Shadow reading game. State the aim of the

game. Practice the game in class.

This activity uses a text from the course book, and involves listening and

pronunciation practice. This task is challenging and motivating and can be used at any

level.

Procedure:

Teacher reads the text aloud and students follow, marking the text for stress

Teacher reads the text a second time and the students mark for linking

Individual chunks that show good examples of linking or problematic pronunciation

can then be drilled

Students practise these aspects of pronunciation by reading the text to themselves

before the teacher reads the text aloud again and they listen

Then the students read the text with the teacher and they have to start and finish at

the same time as the teacher, who reads the text at normal speed

5. Read the description of the Using poetry game. State the aim of the game.

Practice the game in class.

The reasons for using poetry are similar to those for using songs and many activities that

you do with songs can be adapted to poetry.

Any authentic material exposes students to some 'real English' and can be very motivating

for your students, provided they are supported throughout the task. The other great thing

about poems is for students to have the opportunity to see the language work creatively and

freely. Poems can be used in many different ways and the more you use them the more

uses you’ll find for them.

Where can I get the poems from?

Finding poems to use is very easy online. You can find lots of poems by simply typing in the

author and the first line or title. Try:

https://www.poemhunter.com/

If you make worksheets using the poem be sure to acknowledge the author's name and the

source.

How do I choose the right one for my class?

The first thing to consider when you're selecting a poem for your class is the level of

language. If you end up having to explain every single word then the poem may well lose its

spark. On the other hand, students won't need to understand every word to get the general

idea of most poems so don't be put off if you think the language level is slightly above what

they would normally be able to handle. As with songs, if the students are supported

throughout and are pre-taught some of the vocabulary, or given some visual aids to help

them, they will be able to tackle more challenging texts than they are used to.

What activities can I do with a poem?

Introduce a topic

Poems can be a really nice way into a topic. A colleague recently recommended

using a poem called The Ghoul by Jack Perlutsky as a way to introduce a Halloween

lesson. He had made a gap fill by taking out the rhyming words. The students loved

the poem and later on took it in turns reading out the verses with the correct

intonation and taking care to make the rhyming words rhyme. (Thanks to Johnny

Lavery for this idea.)

To introduce the topic of old people and talking about grandparents in a class I've

used Jenny Joseph's poem called Warning. The language is simple and the ideas

are clear and can easily be supported with visual aids for very low levels.

These are just a few examples of linking a poem to a topic. By using a poem as a spring

board into a topic you will make the class memorable for your students.

Ordering the poem

When you have chosen a suitable poem for your class, copy it onto a worksheet and

cut up the verses. If the poem tells a story and the order is logical, ask students to

read the verses and put them into the correct order. If the order isn't obvious, you

can read out the poem and they can listen and put it into order as you read. From

here you can go onto to look at the vocabulary, the rhyming words or to talking about

the meaning of the poem.

Rhyming words

Obviously, some poems lend themselves well to looking at pronunciation. Whether

you want to focus on individual sounds, rhyming pairs, connected speech or

intonation patterns, poems can be a great way into it. Getting students to read out

chunks of a poem as they copy the way you say it can be excellent practice for their

pronunciation.

Learn a verse

Once you have chosen the poem and have worked with it with your class, encourage

the students to learn one verse by heart. It can be really motivating for younger

students to be able to say a whole chunk of English perfectly. Ensure that they want

to learn it and that it has some useful language in it which will be helpful in the future.

Try not to get students to memorise chunks of language just for the sake of it or

because you want to fill in the last few minutes and have run out of activities!

However it can be really satisfying for students to be able to say a nice chunk of

language and to be sure that their pronunciation is good, as they will have practised

it with you.

Record the students

Getting students to record themselves saying a poem can be a nice way to help

them improve their pronunciation. You could put students into pairs or small groups

and get each student to read out aloud one of the verses of the poem. Then listen

back to it in the class.

Write a new verse

If you are teaching higher levels you could ask the students to create a new verse for

the poem or to change one of the existing verses. This would be a challenging

activity for most students so make sure you offer ideas and help to support students

through the task. Be ready to give an example verse to show them that it's do-able!

Role play dialogues

If the poem you are using has any dialogue, you could use it as a springboard into a

role-play. Poems with characters can also be used to inspire role plays. An example

of a poem that would be good for this is A Bad Habit by Michael Rosen.

For most teachers poems are an under-exploited resource that we have available to us.

Although introducing your students to a poem or two throughout the course will take a lot of

thought and a bit of preparation time on your side, I think it will be worth it.

Internet links

BBC Bitesize has some great resources for teaching poetry:

https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/topics/zmbj382

https://www.bbc.com/bitesize/topics/zs43ycw

6. Read the description of the Pronunciation of past simple verbs game. State

the aim of the game. Practice the game in class.

Preparation

You will need to produce a set of around 12 cards, with a (regular) past simple verb on

each. Make sure they're large enough to be seen from the back of the room. You can find

an example below.

Procedure

Start by holding up the cards for students to say what the words have in common.

Once they've identified that they're verbs, past simple and regular (i.e. all with '-ed'

endings), drill the verbs.

Then write up three categories on the board:

-ed = /t/ -ed = /d/ -ed = /Id/

liked learned wanted

Point out that these represent different sounds and ask the class to read them out.

Then show the first card, e.g. liked and ask students to say it aloud and decide which

category it goes in.

Once they indicate the correct category, stick the card to the board. Repeat this for a

second card, e.g. wanted.

Then elicit that the two verbs, like and want, have the same past simple ending, but

the pronunciation is different. Tell the students that you're going to give them the

cards to put in the right category. Depending on the size of the class, hand out two

cards per pair or group.

You can then sit at the back of the class and observe as the students decide where

their verb goes. Remind students to say the verb aloud to help them.

Usually, within minutes, one of the more confident students goes to the board; the

others soon follow.

Once you feel students have done what they can, tell them how many verbs are not

placed correctly, e.g. three, but don't tell them which ones. Encourage students to

make changes, then again tell them how many are now not correct. Continue until all

the cards are in the right place, helping where necessary.

Then ask the class to read all the verbs aloud. Praise them for successfully

completing the task!

With older or more analytically-minded students, the rule for when the verb is

pronounced /Id/ (i.e. when the verb already ends in a /t/ or /d/ sound) can now be

elicited.

Students then have a few minutes to copy their work into their notebooks, adding

one verb of their choice to each category.