How Bargaining Alters Outcomes- Bilateral Trade Negotiations and Bargaining Strategies

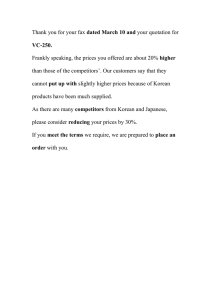

advertisement