Artemisinin Resistance & Malaria Elimination in Mekong Subregion

advertisement

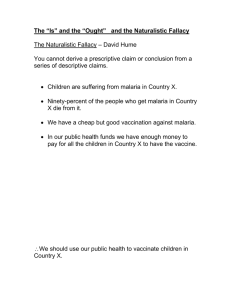

Smith Gueye et al. Malaria Journal 2014, 13:286 http://www.malariajournal.com/content/13/1/286 COMMENTARY Open Access The challenge of artemisinin resistance can only be met by eliminating Plasmodium falciparum malaria across the Greater Mekong subregion Cara Smith Gueye1*, Gretchen Newby1, Jimee Hwang1,2, Allison A Phillips1, Maxine Whittaker3, John R MacArthur2, Roly D Gosling1 and Richard GA Feachem1 Abstract Artemisinin-based combinations are currently the most effective anti-malarials and, in addition to vector control, have led to significant declines in malaria morbidity and mortality. However, foci of artemisinin drug resistance have been identified in the Greater Mekong subregion (GMS) of the Asia Pacific, threatening the major gains made in malaria control and potentially creating a parasite pool that is more difficult to treat and eliminate. Efforts are underway to halt the spread of artemisinin resistance, including coordination of activities and funding, and identification of areas of suspected artemisinin resistance, now using a newly identified molecular marker. However, targeting resources to the containment of resistant parasites is likely inefficient and monitoring impact is challenging. A more sustainable solution is the rapid elimination of all Plasmodium falciparum parasites from the GMS. This strategy is more efficient for several reasons. First, a subregional strategy is in line with current commitment to elimination and will build upon the existing national political support for elimination as well as enhancing collaboration among countries. Second, the challenge of human mobility in the GMS is subregional in scope and requires a harmonized elimination strategy. Third, countries will need to improve and intensify malaria operations to reach elimination, and this will be a singular goal across the subregion. Rallying around the goal of P. falciparum elimination will not only utilize existing regional bodies to catalyze political and funding support, but will also leverage the funding already in place to achieve this subregional goal. Background The Greater Mekong subregion (GMS) of the Asia Pacific, which includes the countries of Cambodia, China (Yunnan Province), Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam, is the epicentre of artemisinin resistance. Foci of resistance have been identified along the Thailand-Myanmar, ThailandCambodia, Vietnam-Cambodia, and Vietnam-Laos borders [1,2], and recently there has been a concerning report of resistance emerging in sub-Saharan Africa, specifically Angola [3]. Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) are currently the most effective antimalarials [1], and, in conjunction with vector control, have led to the significant reduction of malaria morbidity * Correspondence: smithc1@globalhealth.ucsf.edu 1 Malaria Elimination Initiative, Global Health Group, University of California, San Francisco, USA Full list of author information is available at the end of the article and mortality worldwide. The continued development and spread of artemisinin resistance threaten these gains [4,5]. Resistance to anti-malarials has historically originated on the Thailand-Cambodia border; Plasmodium falciparum parasites resistant to chloroquine, then sulphadoxinepyrimethamine, and finally mefloquine were first detected in this part of the world [5]. Initial signs of chloroquine resistance appeared in the late 1950s in Southeast Asia and spread across South Asia to East Africa by 1978 [3], then subsequently across the continent, leading to catastrophic increases in child morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa [1]. Artemisinin resistance could follow the same trajectory, leading to a persistent parasite pool that is harder to eliminate and can increase the incidence of severe or prolonged illness and mortality, particularly in low-transmission areas with reduced population immunity © 2014 Smith Gueye et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. Smith Gueye et al. Malaria Journal 2014, 13:286 http://www.malariajournal.com/content/13/1/286 to malaria [6]. Given this history and the devastating potential impact of global artemisinin resistance, the new reports of the spread of resistance are of grave concern. Current approach Efforts are underway to contain the spread of artemisininresistant P. falciparum, guided by the framework of the World Health Organization’s Emergency Response to Artemisinin Resistance in the Greater Mekong Subregion (ERAR) [1], which outlines the actions needed for improved coordination of activities and funding across the GMS. However, ERAR is in its nascent state and has had limited success to date. Attempts to identify areas of suspected artemisinin resistance through traditional drug efficacy sentinel site monitoring (e.g. monitoring slide positivity on day 3 post-treatment) have been small in scale and difficult to implement, although this process may become easier with the newly identified molecular marker associated with artemisinin resistance [7]. Even so, if identification of areas with resistance is challenging, monitoring the impact of resource-intensive containment efforts and successfully eliminating resistant parasites in these areas will be even more difficult. Moreover, the constant movement of people and parasites in this part of the world translates to continually shifting populations at risk and the ongoing potential to spread resistant infections beyond the area of containment. In light of these challenges, operationally targeting resources to only those areas with resistant parasites has not been effective. Instead, targeting all areas with P. falciparum malaria transmission, regardless of whether resistance has been detected, negates the need to define drug resistance in all sites in real-time, and protects against the spread of resistance to new areas because Page 2 of 4 transmission everywhere is reduced. Thus, there is a strong argument to be made that the only effective and sustainable way to respond to the current resistance situation is the rapid elimination of all P. falciparum parasites from the GMS. Recommended strategy: subregional Plasmodium falciparum elimination Political and financial commitment A subregional elimination strategy is in line with the current commitment to malaria elimination in the GMS and will build political support and enhance collaboration across countries. Five countries in the GMS have already declared an intention to eliminate all forms of malaria within their borders (Figure 1). Cambodia has defined and is actively working toward a P. falciparumspecific elimination goal, and four countries—Cambodia, China, Thailand, and Vietnam—have made major strides toward national elimination of all malaria species [8]. Political commitment for malaria elimination in the GMS is considerable, facilitated by five of the countries’ partnership with, and active participation in, the Asia Pacific Malaria Elimination Network (APMEN), a network of 15 countries across the Asia Pacific region that have declared goals of malaria elimination [8,9]. Leveraging this commitment, a GMS P. falciparum elimination initiative would bring together national programmes and partners around a single, strategic, time-limited goal, presenting an opportunity to achieve a regional public good. A focused, subregional effort specific to artemisinin resistance would improve coordination and harmonization of activities and funding across the six countries and multitude of partners, through the increase of communication and information sharing, launch of operational Figure 1 Countries in the Greater Mekong subregion and their elimination goals. Smith Gueye et al. Malaria Journal 2014, 13:286 http://www.malariajournal.com/content/13/1/286 collaboration in border areas, and identifying and implementing a joint research agenda. All of the countries of the GMS have intensified their control and elimination efforts and are, or will soon be, receiving technical and financial support to boost their operational capacities. Many technical partners are working on research and implementation in the region. Some countries, such as China and Thailand, have made major progress in their capacity for response while others, such as Myanmar, have some work to do to bring the malaria program to a level necessary to meet the resistance challenge. However, well-drafted plans for intensified P. falciparum control and elimination activities will not be impactful unless the GMS countries have the financial resources to make those plans a reality. Funding is now available for GMS countries to increase their capacity, a major source being the Global Fund grant to the Regional Artemisinin Initiative (RAI) [10], but additional and more coordinated funding is necessary to ensure sustainability throughout the region. Making the investment case for a P. falciparum-free GMS may spark the interest of other funders in a way that containment efforts thus far have not. Mobile populations A subregional effort for elimination meets the challenge of human mobility in the GMS. The populations most at risk for development of resistance are primarily located in relatively underdeveloped and remote border regions. The lack of accessible services leads to inadequate detection of resistant malaria and low coverage of preventive and curative services. National malaria strategies typically focus on at-risk populations within country borders, but this approach fails to address the regional nature of migration patterns. Population movement through remote, forested areas and across porous borders increases the difficulty of accessing these groups by any one country. Thus, a comprehensive subregional strategy that relies upon international coordination is essential. Large-scale regional infrastructure developments are underway that necessitate rapid action to prevent the spread of drug-resistant malaria. In late 2015, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will launch the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). The AEC aims to reduce economic disparities among countries through the development of an integrated regional economy, which will create a freer flow of goods, services, capital, and labour, increasing human mobility in the region. Greater population movement in areas with confirmed resistance can facilitate its spread, and the risk will be compounded by the new transport corridors and infrastructure that will increase access to remote areas. Page 3 of 4 Implementing subregional elimination A GMS elimination goal requires that countries improve and intensify malaria control operations and management. A recent joint assessment of containment efforts found insufficient intensity, coverage and quality in the delivery of malaria control interventions [11]. Regional level guidance and technical assistance will help countries develop and maintain the more robust, sustainable and comprehensive set of strategies required to achieve P. falciparum elimination. Such strategies include early diagnosis and treatment, active case detection, case investigation, and effective measures to reduce and prevent transmission. These strategies should be implemented on a national level with robust regional guidance. Execution in a small, foci-based manner will not be as beneficial to the overall health system nor the malaria program. China’s new 1-3-7 malaria surveillance approach provides one operational model of surveillance and response; more countries in the region need to implement surveillance and response measures as an intervention. 1-3-7 defines actions and timelines for effective surveillance activities: case reporting within one day, case confirmation and investigation within three days and appropriate public health response to prevent further transmission within seven days [12]. National malaria programmes must also have adequate budgets for management to ensure that all activities are efficient, well-executed and well-supervised [1]. In addition, because the stakes are high, programmes must be equipped to measure and demonstrate impact. Conclusion Rallying around an urgent and ambitious subregional P. falciparum elimination goal is the only way to effectively remove the historic epicentre of anti-malarial drug resistance. The newly formed Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance (APLMA) presents a timely opportunity: one way to signal commitment to a subregional elimination goal is to have members of the Alliance engage with public and private sector development partners in generating support and mobilizing resources. ASEAN is chaired by Myanmar this year, and encouraging ASEAN to formally indicate that improvements in regional economic trade are linked with anti-malarial drug resistance and subregional malaria elimination would accelerate elimination efforts. This is particularly true given the potential impact of the AEC on the spread of resistance. Finally, proven malaria strategies with the explicit goal of P. falciparum elimination throughout the subregion must be aggressively implemented, without limiting their scope to already-identified resistant focal areas or populations. Progress towards this subregional goal is underway, with encouraging steps taken through the establishment of the RAI, funded by the Global Fund, the Regional Malaria and Other Communicable Disease Threats Trust Smith Gueye et al. Malaria Journal 2014, 13:286 http://www.malariajournal.com/content/13/1/286 Fund hosted by the Asian Development Bank [13], contributions to the ERAR from Australia, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the US Government’s contribution to the President’s Malaria Initiative in the GMS. However, more concerted and long-running efforts are needed. Abbreviations AEC: ASEAN Economic Community; ASEAN: Association of Southeast Asian Nations; APLMA: Asia Pacific Leaders Malaria Alliance; APMEN: Asia Pacific Malaria Elimination Network; ERAR: Emergency response to artemisinin resistance in the Greater Mekong subregion; GMS: Greater Mekong subregion; PDR: Lao People’s Democratic Republic; RAI: Regional Artemisinin Initiative; WHO: World Health Organization. Competing interests The Global Health Group at UCSF exists in part to support global, regional and country efforts to achieve evidence-based malaria elimination. CSG, RG and MW are part of the APMEN Joint-Secretariat and RGAF is co-Chair of APMEN. Authors’ contributions CSG, GN and JH conducted research and analysis and wrote the manuscript. AAP, MW, JM, RDG, and RGAF provided comments on drafts and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements The Malaria Elimination Initiative of the Global Health Group at UCSF is supported by grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Novartis Foundation for Sustainable Development. The work on APMEN at the School of Population Health, University of Queensland, is supported by the Australian Government. The authors declare that no funding bodies had any role in research, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The corresponding author, CSG, confirms that she had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Page 4 of 4 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D: A molecular marker of artemisininresistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 2014, 505:50–55. Asia Pacfic Malaria Elimination Network. 2014. http://www.apmen.org. Gosling RD, Whittaker M, Smith Gueye C, Fullman N, Baquilod M, Kusriastuti R, Feachem RGA: Malaria elimination gaining ground in the Asia Pacific. Malar J 2012, 11:346. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria: Multicountry East Asia and Pacific (RAI). 2014. http://portfolio.theglobalfund.org/en/Country/ Index/MER. Joint Assessment of the Response to Artemisinin Resistance in the Greater Mekong Sub-Region Summary Report. Commissioned by Australian Agency for International Development, Department for International Development (UK), US Agency for International Development and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in collaboration with World Health Organization; 2012. http:// malaria2012conference.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Summary-ofthe-Joint-Assessment-of-the-Response-to-Artemisinin-Resistance.pdf. Cao J, Sturrock HJW, Cotter C, Zhou S, Zhou H, Liu Y, Tang L, Gosling RD, Feachem RGA, Gao Q: Communicating and monitoring surveillance and response activities for malaria elimination: China’s “1-3-7” strategy. PLoS Med 2014, 11:e1001642. Asian Development Bank: Regional strategic response to malaria and other communicable diseases in Asia and the Pacific. 2014. http://www. adb.org/projects/47272-001/main. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-286 Cite this article as: Smith Gueye et al.: The challenge of artemisinin resistance can only be met by eliminating Plasmodium falciparum malaria across the Greater Mekong subregion. Malaria Journal 2014 13:286. Author details 1 Malaria Elimination Initiative, Global Health Group, University of California, San Francisco, USA. 2United States Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Atlanta, USA. 3The School of Population Health, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. Received: 28 May 2014 Accepted: 16 July 2014 Published: 27 July 2014 References 1. WHO: Emergency response to artemisinin resistance in the Greater Mekong subregion: regional framework for action 2013–2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. 2. President’s Malaria Initiative: Greater Mekong Sub-region Malaria Operational Plan FY 2014. http://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-documentlibrary/malaria-operational-plans/fy14/mekong_mop_fy14.pdf?sfvrsn=12. 3. Van Hong N, Amambua-Ngwa A, Tuan NQ, Cuong DD, Giang NTH, Van Dung N, Tinh TT, Van Tien N, Phuc BQ, Duong TT, Rosanas-Urgell A, D’Alessandro U, Van Geertruyden J-P, Erhart A: Severe malaria not responsive to artemisinin derivatives in man returning from Angola to Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20. doi:10.3201/eid2007.140155. 4. Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NPJ, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ: Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 2009, 361:455–467. 5. WHO: Global report on antimalarial drug efficacy and drug resistance: 2000–2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. 6. Bjorkman A, Bhattarai A: Public health impact of drug resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Acta Trop 2005, 94:163–169. 7. Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois A-C, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, Lim P, Leang R, Duong S, Sreng S, Suon S, Chuor CM, Bout DM, Menard S, Rogers WO, Genton B, Fandeur T, Miotto O, Ringwald P, Le Bras J, Berry A, Barale J-C, Fairhurst RM, Benoit-Vical F, Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central and take full advantage of: • Convenient online submission • Thorough peer review • No space constraints or color figure charges • Immediate publication on acceptance • Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar • Research which is freely available for redistribution Submit your manuscript at www.biomedcentral.com/submit