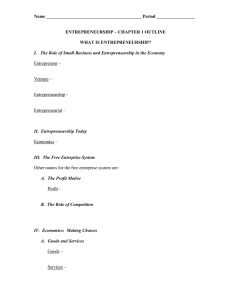

1042-2587-99-233$1.50 Copyright 1999 by Baylor University Corporate Entrepreneurship and !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! the Pursuit of Competitive Advantage Jeffrey G. Covin Morgan P. Miles This paper presents a theoretical exploration of the construct of corporate entrepreneurship. Of the various dimensions of firm-level entrepreneurial orientation identified in the literature, it is argued that innovation, broadly defined, is the single common theme underlying all forms of corporate entrepreneurship. However, the presence of innovation per se is insufficient to label a firm entrepreneurial. Rather, it is suggested that this label be reserved for firms that use innovation as a mechanism to redefine or rejuvenate themselves, their positions within markets and industries, or the competitive arenas in which they compete. A typology is presented of the forms in which corporate entrepreneurship is often mani· fested, and the robustness of this typology is assessed using criteria that have been proposed for evaluating classificational schemata. Theoretical linkages are then drawn demonstrating how each of the generic forms of corporate entrepreneurship may be a path to competitive advantage. Corporate entrepreneurship has long been recognized as a potentially viable means for promoting and sustaining corporate competitiveness. Schollhammer (1982), Miller (1983), Khandwalla (1987), Guth and Ginsberg (1990), Naman and Slevin (1993), and Lumpkin and Dess (1996), for example, have all noted that corporate entrepreneurship can be used to improve competitive positioning and transform corporations, their markets, and industries as opportunities for value-creating innovation are developed and exploited. However, only in recent years has much empirical evidence been provided which justifies the conventional wisdom that corporate entrepreneurship leads to superior firm performance. Perhaps the best evidence of a strong corporate entrepreneurshipperformance relationship is provided in a study by Zahra and Covin (1995). Their study examined the longitudinal impact of corporate entrepreneurship on a financial performance index composed of both growth and profitability indicators. Using data collected from three separate samples and a total of 108 firms, Zahra and Covin (1995) identified a positive and strengthening linkage between corporate entrepreneurial behavior and subsequent financial performance. Assuming that one accepts as valid the espoused and documented utility of corporate entrepreneurship, the reasons why corporate entrepreneurship "works" still remain something of a mystery. That is, the logic of corporate entrepreneurship has not been adequately explained. Recognized bases for competitive advantage, for example, have not been explicitly and systematically linked to corporate entrepreneurial actions. Moreover, the archetypical forms in which corporate entrepreneurial actions are often manifested have not been consistently or clearly delineated in the literature on this topic. However, Spring, 1999 47 until management scholars provide an adequate answer to the question of how corporate entrepreneurship creates competitive advantage, prescriptions for the conduct of corporate entrepreneurship will necessarily remain superficial. Part of the "problem" in trying to infer from the literature why corporate entrepreneurship works is the fact that while there is general agreement that firms per se can be entrepreneurial (e.g., Miles & Arnold, 1991; Morris, Davis & Allen, 1994; Smart & Conant, 1994), there is no consensus on what it means for firms to be entrepreneurial. This situation is exacerbated by the proliferation of labels for entrepreneurial phenomena in organizations. Thus, when management theorists talk about corporate entrepreneurship, they are often talking about different phenomena. And with ambiguity surrounding the nature of the corporate entrepreneurship construct, it is not surprising that a general understanding or theory of why corporate entrepreneurship often creates competitive advantage has failed to emerge. This paper seeks to contribute to the literature on corporate entrepreneurship in two ways. First, this paper will attempt to clarify what it means for firms to be entrepreneurial. In particular, it will be argued that the proliferation in the literature of diverse and often inconsistent definitions of corporate entrepreneurship has created confusion over the nature of the construct, and that much of the writing on this topic fails to recognize what defines the essence of an entrepreneurial firm-level posture. Second, this paper will propose a typology of the common forms of corporate entrepreneurship. The forms identified here are presented as "pure" types that reflect the generic manifestations of the corporate entrepreneurship phenomenon. The robustness of the typology will be assessed using criteria that have been proposed for evaluating classificational schemata. The reasons why the various forms of corporate entrepreneurship may be paths to competitive advantage will then be discussed. CLARIFICATION OF THE CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP CONSTRUCT The label corporate entrepreneurship has been attached to multiple and sometimes distinct organizational phenomena. Three of the most common phenomena that are often viewed as examples of corporate entrepreneurship include situations where (I) an "established" organization enters a new business; (2) an individual or individuals champion new product ideas within a corporate context; and (3) an "entrepreneurial" philosophy permeates an entire organization's outlook and operations. These phenomena are not inherently alternative (i.e., mutually exclusive) constructs, but may co-exist as separate dimensions of entrepreneurial activity within a single organization. The first phenomenon, where an "established" organization enters a new business, has typically been referred to as corporate venturing and is well described in the writings of, for example, Block and MacMillan (1993), Burgelman (1983), and Venkatraman, MacMillan, and McGrath (1992). The second phenomenon, where an individual or individuals champion new product ideas within a corporate context, is perhaps best known by the label "intrapreneurship," a term popularized by Pinchot (1985). The process of intrapreneuring is well documented in writings on product and innovation champions (e.g., Shane, 1994; Kanter, 1982; Jelinek & Schoonhoven, 1990). The third phenomenon, where an "entrepreneurial" philosophy permeates an entire organization's outlook and operations, has been discussed using labels such as entrepreneurial management (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990), entrepreneurial posture (Covin, 1991), entrepreneurial orientation (Ramachandran & Ramnarayan, 1993), firm level entrepreneurship (Morse, 1996), entrepreneurial strategy making (Dess, Lumpkin, & Covin, 1997), and pioneering-innovative management (Khandwalla, 1987). This final phenomenon, 48 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE whereby firms per se act in entrepreneurial manners, is the focus of the current manuscript. That is, the term corporate entrepreneurship is reserved to refer to cases where entire firms, rather than exclusively individuals or other "parts" of firms, act in ways that generally would be described as entrepreneurial. Nonetheless, ambiguities and inconsistencies persist in how corporate entrepreneurship has been operationalized by those who have adopted a firm-level perspective on the topic. For example, Jennings and Lumpkin (1989) equate firm-level entrepreneurship with product innovation or market development. Specifically, in their study of corporate entrepreneurship within the savings and loan industry, Jennings and Lumpkin (1989) refer to any firm that introduces an above-average number of new products or develops an above-average number of new markets as an entrepreneurial firm. Additional criteria are suggested by other researchers before a firm should be referred to as entrepreneurial. Karagozoglu and Brown (1988), for example, categorized a firm as entrepreneurial only if it engaged in product innovation and risk-taking behavior. Morris and Paul (1987), Covin and Slevin (1989,1990), Miles and Arnold (1991), Dean (1993), and Zahra (1991) have all operationalized corporate entrepreneurship in manners consistent with Miller's (1983) argument that entrepreneurial firm-level behavior implies the existence of (1) product or process innovation, (2) a risk-taking propensity by the firm's key decision makers, and (3) evidence of proactiveness with respect to product-market introductions or the early adoption of new administrative techniques or process technologies. (In Miller's earlier research [Miller & Friesen, 1982] this third criterion-proactivenesswas not identified as essential to classifying a firm as entrepreneurial.) In short, there are significant differences of opinion among corporate entrepreneurship researchers regarding what attributes must be present in order to label a firm entrepreneurial. Fortunately, a recent and excellent paper by Lumpkin and Dess (1996) has gone a long way toward helping to define the dimensions of an "entrepreneurial orientation." In particular, based on a thorough review of the broadly defined corporate entrepreneurship literature, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) identified five dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation-namely, autonomy, innovativeness, risk taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness. They, nonetheless, conclude that it is unclear whether all five dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation will always be present in entrepreneurial firms, or whether any of these identified dimensions must always be present before the existence of an entrepreneurial orientation should be claimed. The position taken in this paper is that there is a commonality among all firms that could be reasonably described as entrepreneurial. This commonality is the presence of innovation. Consistent with the observations of Burgelman, Kosnik, and van den Pol (1988), innovation, as conceived of here, refers to the introduction of a new product, process, technology, system, technique, resource, or capability to the firm or its markets. As noted by Stevenson and Gumpert (1985), innovation is the "heart of entrepreneurship." Likewise, Stopford and Baden-Fuller (1994, p. 522) observed that "most authors accept that all types of entrepreneurship are based on innovations." Therefore, the label entrepreneurial should not be applied to firms that are not innovative. Innovation is at the center of the nomological network that encompasses the construct of corporate entrepreneurship. Certainly it is easy to envision how the other dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation identified by Lumpkin and Dess (1996) could be antecedents, consequences, or simple correlates of innovation and, thereby, help to define the domain of corporate entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, without innovation there is no corporate entrepreneurship regardless of the presence of these other dimensions. Still, there appears to be something missing from much of the empirically based as well as purely conceptual literature that purports to focus on corporate entrepreneurship as a firm-level phenomenon. As noted above, corporate entrepreneurship necessarily implies the presence of innovation, but there is more to corporate entrepreneurship than Spring, 1999 49 innovation. For example, firms that replace their core production technologies with newer technologies that are disseminating throughout their industries may be engaged in innovations that from an internal, organizational perspective are quite dramatic. However, such innovations will not typically evoke images of corporate entrepreneurship. Integrated U.S. steel manufacturers-like U.S. Steel, Inland, National, LTV, and Bethlehem-are a good case in point. While several of these firms switched during the 1970s and 1980s from open-hearth furnace technology to newer oxygen-based furnace technology, few would identify these as entrepreneurial firms within their industry segments. Moreover, this additional "missing" element is not simply the presence of autonomy, risk taking, proactiveness, or competitive aggressiveness, although each of these dimensions could easily flourish in entrepreneurial firms. Rather, the element that, we believe, must exist in conjunction with innovation in order to claim an entrepreneurial orientation is the presence of the objective of sustaining high performance or improving competitive standing through actions that radically energize organizations or "shake up" the status quo in their markets or industries. That is, corporate entrepreneurship is engaged in to increase competitiveness through efforts aimed at the rejuvenation, renewal, and redefinition of organizations, their markets, or industries. Corporate entrepreneurship revitalizes, reinvigorates, and reinvents. It is the spark and catalyst that is intended to place firms on the path to competitive superiority or keep them in competitively advantageous positions. In fairness, the preceding "missing element" of the literature on corporate entrepreneurship-the objective of rejuvenating or purposefully redefining organizations, markets, or industries in order to create or sustain a position of competitive superiority-is evident in some definitions and discussions of this phenomenon. Miller (1983, p. 770), for example, states that corporate entrepreneurship is "the process by which organizations renew themselves and their markets...." Likewise, Zahra (1997) includes a "strategic renewal" element in his empirical operationalization of the construct of corporate entrepreneurship. Nonetheless, one cannot keep from being struck by the fact that this recognition, while having strong face validity and intuitive appeal, is not widely reflected in the corporate entrepreneurship literature. The importance of recognizing the centrality of this "rejuvenation and redefinition" element to the corporate entrepreneurship construct can hardly be overstated. Corporate entrepreneurship is not just the old wine of organizational innovation in new bottles, as those who are cynical over the constant emergence of new managerial fads might suggest. Rather, corporate entrepreneurship refers to a distinct, multidimensional, and empirically verifiable set of organizational phenomena. Importantly, the complete academic and practitioner legitimacy of corporate entrepreneurship will only be realized when both the innovation and the rejuvenation and redefinition elements are widely recognized as defining the essence of the construct. THE FORMS OF CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP Having defined corporate entrepreneurship as the presence of innovation plus the presence of the objective of rejuvenating or purposefully redefining organizations, markets, or industries in order to create or sustain competitive superiority, it is possible to envision at least four forms of this phenomenon. These forms will be labeled sustained regeneration, organizational rejuvenation, strategic renewal, and domain redefinition. As conceptualized here, these forms relate to the organization's ability to regularly introduce new products or enter new markets, to the organization per se, to the organization's strategy for navigating its current environment, and to the organization's creation and exploitation of new product-market arenas, respectively. Significantly, all four corporate 50 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE entrepreneurship forms are defined by at least one potential basis for competitive advantage, albeit some more clearly than others. It is important to emphasize that these forms will often concurrently exist in entrepreneurial organizations. However, they will be presented separately here in order to clarify what we regard as fundamental to each. It is also acknowledged that, in reality, organizations typically cannot a-priori determine a particular corporate entrepreneurship outcome. As noted by Hamel (1997, p. 80), "innovative strategies [like the forms of corporate entrepreneurship presented here] are always, and I mean always, the result of lucky foresight." Thus, the emergence of each of the four forms is not something that is simply a matter of managerial choice. Since the outcomes of entrepreneurial processes are uncertain, a form of corporate entrepreneurship cannot be readily enacted as a deliberate strategy with the expectation that particular outcomes will necessarily be realized. Nonetheless, the four forms of corporate entrepreneurship are presented below to elucidate the characteristics of what would seem to be some of the most common firm-level manifestations of entrepreneurial processes. Sustained Regeneration Sustained regeneration is the form of corporate entrepreneurship that is, perhaps, most widely accepted and recognized as evidence of firm-level entrepreneurial activity. In particular, firms that engage in sustained regeneration are those that regularly and continuously introduce new products and services or enter new markets. This ongoing stream of new products and services or new market introductions is intended to capitalize on latent or under-exploited market opportunities using the firm's valued innovationproducing competencies. Firms successful at the sustained regeneration form of corporate entrepreneurship tend to have cultures, structures, and systems supportive of innovation. They also tend to be learning organizations that embrace change and willingly challenge competitors in battles for market share. Moreover, at the same time they are introducing new products and services or entering new markets, these firms will often be culling older products and services from their lines in an effort to improve overall competitiveness through product life cycle management techniques. Arm & Hammer is a good example of a firm that exhibits both the "new products" and "new markets" variants of sustained regeneration. Although it is a small, narrow-line player within its industry, Arm & Hammer has been able to achieve enviable financial returns through the creative introduction of its core product-baking soda-into new product-market arenas. For example, through the development and introduction of baking soda-based toothpaste and deodorizing products, Arm & Hammer has been able to capitalize on emerging product-market opportunities unseen or underappreciated by competitors in its core industry segment. This strategy is not simply one of product development or related diversification. Rather, the proactive, competence-expanding actions of Arm & Hammer reflect conscious decisions to regularly and strategically expand the business of the company for the purpose of ensuring its long-term competitiveness. This is evidence of sustained regeneration. Also typical of firms that exhibit evidence of the sustained regeneration form of corporate entrepreneurship are 3M, Motorola, and Mitsubishi. These firms have reputations as innovation machines. Although each is broadly diversified across multiple business segments, they share the common attributes of entrepreneurial cultures, flexible structures, rapid decision making capabilities, and discontent with the status quo. These firms are constantly striving for a broader market presence or greater market share. Significantly, they view their capacities for innovation as essential core competencies that must be protected, nourished, and leveraged through corporate strategies of continual product/service development. Spring, 1999 51 Organizational Rejuvenation The label organizational rejuvenation is used to refer to the corporate entrepreneurship phenomenon whereby the organization seeks to sustain or improve its competitive standing by altering its internal processes, structures, and/or capabilities. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as organizational renewal (Hurst, Rush, & White, 1989), corporate renewal (Beer, Eisenstat, & Spector, 1990), or corporate rejuvenation (Stopford & Baden-Fuller, 1990) in the corporate entrepreneurship and competitiveness literatures. However, these latter terms are often used in reference to entrepreneurial phenomena that entail strategy as well as organizational changes. In contrast, the current use of the term organizational rejuvenation is intentionally limited to corporate entrepreneurial phenomena for which the focus and target of innovation is the organization per se. This position is adopted because we believe it is important to recognize that firms need not change their strategies in order to be entrepreneurial. Rather, corporate entrepreneurship may involve efforts to sustain or increase competitiveness through the improved execution of particular, pre-existing business strategies. When this is the case, organizational rejuvenation is the label we would attach to the entrepreneurial phenomenon. Improved strategy execution via organizational rejuvenation frequently entails actions that reconfigure a firm's value chain (Porter, 1980) or otherwise affect the pattern of internal resource allocation. For example, Procter and Gamble has been able to greatly improve its inventory and distribution systems in recent years through the extensive adoption of bar-coding technology. This technology has not only revolutionized the entire outbound logistics function within P&G but has enabled the firm to sustain its position as a leading consumer products company by setting the customer service standard against which competitors are being judged. General Electric has introduced numerous and often radical new administrative techniques, operating policies, and human resource practices over the past fifteen years. Many of these innovations have been aimed at transforming the corporation from a change-resistant firm to a continuouslearning organization. The net effect of these internal changes has been to improve GE's competitiveness across its diversified business portfolio. At Chrysler Corporation, the entire process through which automobiles are designed and produced has been reconfigured in recent years. Using what is referred to as a "platform" team structure, Chrysler brings together managers and employees from across the corporation to achieve strong and effective functional integration. Because of their positive impact on things like product development cycle time and product quality, the process reengineering principles adopted at Chrysler are often credited with enabling the firm to sustain its position as a leader in the global automobile industry. In each of the above cases the firm in question introduced an innovation or innovations that (1) redefined how some major aspect of its operations was conducted, (2) created value for the firm's customers, and (3) sustained or improved the firm's ability to effectively implement its chosen strategy. Importantly, identifying each of these innovations as an example of corporate entrepreneurship would likely meet with minimal disagreement. Strategic Renewal The label strategic renewal is used here to refer to the corporate entrepreneurship phenomenon whereby the organization seeks to redefine its relationship with its markets or industry competitors by fundamentally altering how it competes. Whereas the focal point for organizational rejuvenation is the organization per se, the focal point for strategic renewal is the firm within its environmental context and, in particular, the strategy that mediates the organization-environment interface. 52 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE It should be acknowledged that there is a risk in adopting the label strategic renewal when referring to this third form of corporate entrepreneurship. Specifically, like the label corporate entrepreneurship, the label strategic renewal has been used in the past to refer to different phenomena. For example, Guth and Ginsberg (1990, p. 5) defined strategic renewal as "the transformation of organizations through renewal of the key ideas on which they are built." In Guth and Ginsberg's (1990) conceptualization ofthis phenomenon, strategic renewal does not necessarily relate to organizational strategy and could conceivably more closely approximate the aforementioned phenomenon of organizational rejuvenation. In contrast, when Simons (1994) uses the term strategic renewal he is simply referring to the implementation of a "new" business strategy. As conceptualized in the current corporate entrepreneurship typology, the phenomenon of strategic renewal necessarily implies the implementation of a new business strategy. However, the label strategic renewal is intentionally limited to the phenomenon in which new business strategies differ significantly from past practices in ways that better leverage the firm's resources or more fully exploit available product-market opportunities. Defined in this manner, strategic renewal can be observed in a variety of business scenarios. For example, declining firms facing turnaround situations sometimes embrace new product or process technologies that allow them to redefine how they compete and their industry positions. After years of decline within the motorcycle industry, HarleyDavidson reinvented itself through strategic renewal. In a sharp departure from its not-too-distant past, Harley-Davidson is no longer content to let its reputation as an American company and its production of classically styled motorcycles be its primary bases for competition. Through major investments in product and process R&D and the adoption of what is commonly referred to as a marketing orientation (e.g., Miles & Arnold, 1991; Hills & LaForge, 1992), Harley-Davidson has been able to radically change the bases on which it competes. While still appropriately characterized as pursuing a niche-differentiation strategy, Harley-Davidson is now differentiated on the bases of superior quality, excellent service, and responsiveness to customers' product desires. The preceding is not meant to imply that only struggling or somehow disadvantaged firms will benefit from strategic renewal. This form of corporate entrepreneurship may also facilitate the maintenance of competitive superiority among industry leaders. In fact, sometimes industry leaders must embrace strategic change to ensure their viability. For example, when IBM introduced the "System 360" line of mainframe computers in the mid-1960s it already held over two-thirds of the mainframe market share. Yet the System 360 line represented not just a new product line for the company but a new strategy for competition in the mainframe computer industry. This new strategy emphasized the technological compatibility (not just performance) of IBM products, an increasingly valued basis for advantage that simply could not be matched by IBM's competitors. According to Maidique and Hayes (1984, p. 21), IBM's System 360 strategy "redefined the rules of competition for decades to come." Still, given the relative reluctance of industry leaders to modify or abandon strategic recipes that produced positive results in the past (see Schwenk & Tang, 1989; Miller, 1990), strategic renewal may not be as pervasive among industry leaders as among those seeking leadership or, at a minimum, improved positions. The preceding examples are offered as cases where the label strategic renewal applies. These examples are not presented as exhaustive of the specific manifestations of strategic renewal. More important, however, than delineating the various potential manifestations of strategic renewal is communicating the essence of the phenomenon. In every case, it is corporate strategy that is viewed as both the key to energizing the firm and the medium though which long-term competitive advantage is sought. Deliberate and major repositioning actions characterize these strategies of renewal. Spring. 1999 53 Domain Redefinition Finally, domain redefinition is the label used to refer to the corporate entrepreneurship phenomenon whereby the organization proactively creates a new product-market arena that others have not recognized or actively sought to exploit. By engaging in domain redefinition the firm, in effect, takes the competition to a new arena where its first or early mover status is hoped to create some bases for sustainable competitive advantage. Through domain redefinition firms often seek to imprint the early structure of an industry. Under such a scenario, the entrepreneurial firm may be able to create the industry standard or define the benchmark against which later entrants are judged. Thus, firms that engage in domain redefinition are entrepreneurial by virtue of the fact that they exploit market opportunities in a preemptive fashion, redefining where and how the competitive game is played in the process. Two specific manifestations of the domain redefinition form of corporate entrepreneurship are bypass strategies and product-market pioneering. Fahey (1989) describes bypass strategies as "attacking by surpassing competitors." This type of business-level strategy is driven by a firm's desire to (1) avoid competitive confrontation in some specific product-market arena or (2) move the competitive battle to a new arena where current or prospective competitors are likely to suffer from later-entrant status. For example, facing stiff and increasing competition in the financial services industry, twenty years ago Merrill Lynch introduced the Cash Management Account, an allpurpose brokerage account. Through this introduction Merrill Lynch succeeded in both decreasing its vulnerability to the hostilities and uncertainties of the financial services industry and in creating a new product-market arena within this industry. It took competitors well over a decade to catch up. Thus, Merrill Lynch effectively bypassed its competition and enhanced its profitability and competency base through redefining its competitive domain. A similar phenomenon to bypass strategies are product-market pioneering strategies. In fact, these labels can refer to the same phenomenon. However, whereas bypass strategies are strongly motivated by a desire to decrease overall vulnerability to adverse, current competitive conditions, product-market pioneering strategies tend to be more opportunistic in character. That is, they are pursued not so much to avoid the existing but to exploit the potential. In either case, however, the desired effect on the organization is one of increased competitiveness through innovation that positively redefines the firm's product-market domain. Golder and Tellis (1993, p. 159) define a pioneer as "the first firm to sell in a new product category." The term product category refers to a group of products that consumers view as substitutable for one another yet distinct from those in another product category. Product categories are, in effect, product-market arenas. Established firms that "pioneer" are, by definition, redefining their domains. A good example of this phenomenon is Sony's creation and exploitation of a new product-market arena within the audio portion of the consumer electronics industry. Specifically, over a decade ago Sony introduced the Walkman to a very receptive and enthusiastic public. Numerous competitors have since entered this product-market arena. However, due to Sony's accumulated first-mover advantages (in the areas of, for example, patent protection, channel access, and reputation), these competitors have yet to achieve anything near Sony's level of success. In each of the preceding cases, the exploration of a new product-market arena helped to energize and reorient the firm. The products introduced were innovative from the perspective of the firm, the industry, and the market. Proactiveness and at least a moderate amount of risk characterized each of these introductions. In short, the dynamics and 54 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE dimensions of corporate entrepreneurship are clearly manifested in the phenomenon of domain redefinition. A THEORETICAL EVALUATION OF THE PROPOSED TYPOLOGY While the proposed typology of corporate entrepreneurship forms may have a certain amount of face validity, it is important to evaluate this typology using criteria suggested for the development of acceptable classificational schemata. Hunt (1983) offers one such set of criteria. According to Hunt (1983, p. 355), for a classification schema to be maximally robust one should be able to answer the majority of the following five questions in the affirmative: 1) Does the schema adequately specify the phenomenon to be classified? 2) Does the schema adequately specify the properties or characteristics that will be doing the classifying? 3) Does the schema have categories that are mutually exclusive? 4) Does the schema have categories that are collectively exhaustive? 5) Is the schema useful? Regarding the current typology, it is possible to answer the first question in the affirmative because each of the phenomena to be classified-that is, the four forms of corporate entrepreneurship-meets the definitional criteria of corporate entrepreneurship as discussed earlier in this paper. The current typology also fairs well in reference to the second question because the four forms have distinct foci and empirical manifestations that are identified in the descriptions of these forms. The criterion of mutual exclusivity, as suggested by question three, is not met by the current typology. Mutual exclusivity exists, according to Hunt (1983, p. 359), when no single item will fit into two or more categories. The current typology does not have this characteristic. The strategic renewal form of corporate entrepreneurship is the source of difficulty here. Specifically, any time a firm adopts or begins to strongly exhibit an entrepreneurial behavior pattern that represents a fundamental departure from past strategic behavior for the firm, strategic renewal can be said to exist. The problematic matter here is that this single manifestation or form of corporate entrepreneurship-that is, the newly adopted entrepreneurial behavior pattern-s-could be categorized as strategic renewal and whatever other category of corporate entrepreneurship the entrepreneurial behavior reflects. For example, if a conservative, non-innovative firm were to begin acting entrepreneurially by regularly introducing new products, this single expression of entrepreneurial firm-level behavior-that is, the newly adopted strategy of competing through frequent new product introductions-e-could be viewed as evidence of both sustained regeneration and strategic renewal. Fortunately, Hunt (1983) notes that the failure of classificational schemata to meet the mutual exclusivity criterion is not a "mortal blow" to a schema, and that many commonly used classifications (such as the distinction between industrial and consumer goods) fall short of this ideal. Moreover, in defense of the current typology, it might be noted that any of the four forms of corporate entrepreneurship may exist without any of the others existing, and that even an "extreme" manifestation of any of the identified forms of corporate entrepreneurship will not inherently include evidence of any of the other forms. Thus, while sustained regeneration and domain redefinition, for example, may be outcomes of similar entrepreneurial processes, firms that regularly introduce new products or enter new markets (evidence of sustained regeneration) may never have an arena-creating new product-market introduction (evidence of domain redefinition), and firms that achieve Spring, 1999 55 the latter may not be frequent new product-market innovators. Similar observations could be made in regard to the other identified forms of corporate entrepreneurship. The fourth question proposed by Hunt (1983) for assessing the robustness of classificational schemata-Does the schema have categories that are collectively exhaustive?-cannot be definitively answered in the affirmative when applied to the current corporate entrepreneurship typology. This typology contains categories or forms of corporate entrepreneurship that should be widely recognizable to those familiar with firm-level entrepreneurial phenomena. Certainly the typology has content validity. Still, it would be presumptuous to conclude that such phenomena are necessarily limited to those identified in the proposed typology. The fifth question-Is the schema useful?-can be answered in the affirmative on at least two bases. First, the proposed typology represents a rare attempt to attach some unambiguous definitions to entrepreneurial phenomena for the purpose of facilitating a better understanding of the corporate entrepreneurship construct. Second, the proposed typology can be empirically operationalized for the purpose of theory testing, the results of which may eventually contribute to the effective practice of corporate entrepreneurship. Overall, it can be concluded that while the proposed four-forms typology is not beyond all criticism, it enjoys many of the properties that make a classification schema theoretically sound and useful. Thus, the current typology represents a reasonable starting point in an attempt to bring some order and concreteness to how the construct of firm-level entrepreneurship might be depicted in theory and observed in practice. CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE Significantly, the seeds of competitive advantage are evident in each of the aforementioned forms of corporate entrepreneurship. There are several fundamental bases for competitive advantage. Porter's writings (1980; 1985) clarified the logic of overall cost leadership and differentiation as bases for competitive advantage. More recently, strategic management scholars have recognized the importance of speed or quick responsethat is, having a market offering prior to competitors-as a distinct basis for competitive advantage (e.g., Bhide, 1986, Stalk, 1988). Each of the bases for advantage potentially could be exploited by firms that engage in sustained regeneration, organizational rejuvenation, strategic renewal, or domain redefinition. However, overall cost leadership may be the basis for competitive advantage one would most typically associate with the organizational rejuvenation form of corporate entrepreneurship. Specifically, it seems plausible that organizational rejuvenation-s-due to its internal, organizational focus-may most commonly create advantage based on efficiencies achieved through actions that lower an organization's cost structure. Differentiation-based advantage will likely be common among firms engaged in the sustained regeneration form of corporate entrepreneurship. This expectation follows from at least two rationales. First, a reputational distinction and advantage tends to become associated with the most innovative companies, like Sharp Corp. and HewlettPackard. This reputational advantage will often positively differentiate the products of these companies in the minds of prospective consumers. Second, and related to the preceding point, companies that regularly and continuously introduce new products or enter new markets often exploit existing brand names that leverage consumer awareness. Intel Corp., for example, leverages its name recognition in the Pentium line as a basis for competitive differentiation. Finally, quick response is the basis for competitive advantage one might most 56 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE commonly associate with the domain redefinition form of corporate entrepreneurship. Domain redefinition implies taking the competitive battle to a new product-market arena. If competitors have yet to enter this arena, then the quick response basis for advantage is necessarily being exploited. Strategic renewal has the weakest inherent link to any of the three bases for competitive advantage. This observation is not meant to suggest that strategic renewal will likely be weakly linked to some basis or bases for competitive advantage. Rather, there is simply not an obvious "most likely" basis for advantage one would associate with the strategic renewal form of corporate entrepreneurship. The particular reasons why strategic renewal could be expected to result in competitive advantage will depend on the specific manifestation or case of strategic renewal in question. Table I summarizes the "focus" of each form of corporate entrepreneurship as well as the "typical basis for competitive advantage" associated with each. This table also summarizes for each form the "typical frequency of new entrepreneurial acts" and the "magnitude of negative impact if new entrepreneurial act is unsuccessful." A "new entrepreneurial act" is a behavior that reflects the focus of the form of corporate entrepreneurship in question. Thus, as noted in Table I, a new entrepreneurial act in the context of the sustained regeneration form of corporate entrepreneurship is a new product introduction or the entrance of a new (to the firm) but existing market; for organizational rejuvenation it is a major, internally focused innovation aimed at improv- Table 1 Some Key Attributes of the Four Forms of Corporate Entrepreneurship Typical Basis for Competitive Advantage Magnitude of Typical Negative Impact if New Frequency of New Entrepreneurial Entrepreneurial Act is Unsuccessful Acts* Form of Corporate Entrep. Focus of Corporate Entrep. Sustained Regeneration New Products or New Markets Differentiation High Frequency Low Organizational Rejuvenation The Organization Cost Leadership Moderate Frequency Low-to-Moderate Strategic Renewal Business Strategy Less Frequent Moderate-to-High Domain Redefinition Creation and Exploitation of Product-Market Arenas Varies with Specific Form Manifestation Quick Response Infrequent Varies with Specific Form Manifestation and Contextual Considerations *New Entrepreneurial Acts for • Sustained Regeneration: A new product introduction or the entrance of a new (to the firm) but existing market. • Organizational Rejuvenation: A major, internally focused innovation aimed at improving firm functioning or strategy implementation. • Strategic Renewal: The pursuit of a new strategic direction. • Domain Redefinition: The creation and exploitation of a new, previously unoccupied product/market arena. Spring, 1999 57 ing firm functioning or strategy implementation; for strategic renewal it is the pursuit of a new strategic direction; and for domain redefinition it is the act of creating and exploiting a new, previously unoccupied product-market arena. Table I shows that the frequency of new entrepreneurial acts are high, of moderate frequency, less frequent, and infrequent for sustained regeneration, organizational rejuvenation, strategic renewal, and domain redefinition, respectively. The assigned frequency levels are intended to reflect the typical ease with which new entrepreneurial acts are pursued within each form of corporate entrepreneurship. New entrepreneurial acts in the sustained regeneration form are frequent by definition. For most firms, major internal innovations will not be so regularly or easily embraced, so new entrepreneurial acts of organizational rejuvenation are identified as moderate. Changing strategic directions may be even harder for most firms than implementing major internal innovations. Therefore, new entrepreneurial acts of strategic renewal are likely to be even less frequent. Finally, finding ways to bypass competitors or pioneer truly new product-market arenas requires much creativity and marketing savvy, a product like no one else's, and a certain amount of luck. As such, new entrepreneurial acts of domain redefinition may be the most rare. The information on the "magnitude of negative impact if new entrepreneurial act is unsuccessful" is furnished in Table 1 because of the importance of communicating the potential down-side to corporate entrepreneurship. As with the pursuit of any innovative initiative there will be risk to the organization when pursuing the various forms of corporate entrepreneurship. However, these forms are expected to differ in the extent to which they may jeopardize firm performance or viability. Specifically, for sustained regeneration, the magnitude of negative impact on firm performance if a new entrepreneurial act fails is rated as low. One bad product or one poor market entry decision will typically not threaten the viability of a highly innovating firm. The risk to firm performance associated with an unsuccessful major, internal innovation could be somewhat greater depending upon the centrality of the innovation to the firm's effective implementation of its business strategy. Considering two of the aforementioned cases, if P&G had failed to successfully and extensively implement bar-coding technology, one portion of its value chain would have been disrupted and the firm may have been rendered temporarily vulnerable to competitor opportunism. Even so, the negative impact on firm performance would likely have been low. However, if Chrysler had failed to implement its "platform" team structure initiative, more negative consequences could have resulted. This is due to the greater relative importance of the operations function-which the platform team structure mainly affects-to the success of Chrysler's business strategy. A negative impact on firm performance of moderate-to-high magnitude would be expected if new entrepreneurial acts of strategic renewal fail. A failure at strategic renewal implies that a firm has been unable to successfully execute a strategic redirection. Such failures can be costly in both a resource requirement sense and in an opportunity cost sense. The depletion of resources that accompanies failed strategic renewal attempts can easily threaten the viability of a firm. On a similar note, strategies take time to prove themselves, and managers who have committed their firms to new strategies may be unlikely to admit the failure of these new strategies until much time has elapsed and other significant resources have been consumed. At the point of admitting failure, these managers may have sapped so much strength from their businesses that a successful strategic turnaround will be unlikely. Even in the case of a successful firm pursuing a new strategic direction, the prospects of a full recovery from a failed strategic renewal initiative may be slim. For example, if IBM's System 360 strategy had failed, competitors would likely have had an opportunity to gain ground on this industry leader as it struggled to identify yet another new strategy or to reinstitute its past strategy. 58 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE Generalizing about the likely impact of failed domain redefinition acts on firm performance is difficult-to-impossible. This is because the percent of total firm resources gambled in individual domain redefinition initiatives will vary greatly according to such things as the size of the firm, the cost to the firm of trying to exploit the new productmarket arena, and the firm's confidence in the viability or attractiveness of the new product-market arena. For example, the risk to Sony in trying to create and exploit a product-market arena for its Walkman was quite minimal. Sony was so large, and the resources required so relatively small, that a failure in this new product-market arena would likely have had minimal negative impact on overall firm performance. In stark contrast, many small biotechnology firms, like Biodel, have declared bankruptcy or relinquished involvement in more immediately promising product lines after having squandered significant resources trying to create and exploit potentially lucrative new arenas for genetic engineering products. Accordingly, Table 1 notes that the down-side effect of failed domain redefinition acts on firm performance "varies." CONCLUSION This theoretical exploration of the construct of corporate entrepreneurship began with the observation that there is a poor understanding of the reasons why corporate entrepreneurship often produces, or at least is assumed to produce, superior firm performance. Based on the preceding discussions, one response to this uncertainty should be clearer. That is, corporate entrepreneurship has a positive reputation as a generally effective behavioral phenomenon because the organizational actions associated with this phenomenon can often be linked to recognized bases of competitive advantage. A second reason why corporate entrepreneurship may contribute to firm performance is that at least one of the aforementioned forms of corporate entrepreneurship will represent appropriate, defensible, and value-enhancing behavior in any given firm's specific competitive context. For example, organizational rejuvenation would seem to fit particularly well with dominant or otherwise competitively strong firms since these firms' successful strategies will often not "require" major modification. Rather, an emphasis on organizational rejuvenation may further improve the firms' implementation of a strategy that has already led to high performance. On the other hand, strategic renewal implies some amount of strategic repositioning. Such repositioning may generally be of greater value among weaker or nondominant firms whose current strategies, by definition, have not resulted in strong competitive positions. The attractiveness of domain definition would seem to vary in inverse proportion with the attractiveness of an industry. That is, in industries where the long-term prospects for profitability or growth are uncertain or bleak, domain redefinition may be an especially desirable form of corporate entrepreneurship. Finally, sustained regeneration would seem to be particularly viable among firms operating in the expanding product-market domains of growth industries, or in mature industries where product differentiation and market segmentation efforts are often associated with the leading firms. In short, it might also be claimed that corporate entrepreneurship "works" because there will typically be a form of this phenomenon that is a recognized route to success, taking into account the particulars of any given firm's business strength and industry context. Yet another reason for corporate entrepreneurship's enviable reputation may relate to how this phenomenon is manifested in organizations. As emphasized above, the forms of corporate entrepreneurship are presented here as distinct manifestations of firm-level entrepreneurship. However, these forms will often concurrently exist in entrepreneurial organizations. AT&T, for example, can be pointed to as a case where both the sustained regeneration and the domain redefinition forms of corporate entrepreneurship are clearly Spring. 1999 59 evident-sustained regeneration because of AT&T's steady stream of new product introductions and domain redefinition because of AT&T's arena-defining technological pioneering successes. Since the various forms of corporate entrepreneurship may be associated with different bases on which competitive advantage is being sought, it is plausible that another reason why corporate entrepreneurship works is that entrepreneurial firms will often be leveraging multiple bases for advantage. As observed by Hamel and Prahalad (1989), high performance often results when firms are able to "layer" several bases for competitive advantage. Consistent with this point, recent evidence by Dess et al. (1997) suggests that firms with entrepreneurial postures are likely to benefit from engaging in actions that achieve such layering. The significance to managers of these observations is potentially great. The linkage between corporate entrepreneurship and firm performance has been empirically documented in methodologically rigorous research. However, it is only after understanding how and why corporate entrepreneurship produces superior firm performance that reservations regarding the possible spuriousness of this relationship can and should be discounted. The insights and arguments presented in this paper suggest that corporate entrepreneurship produces superior firm performance for identifiable, defensible, and strategically valid reasons. Thus, corporate entrepreneurship should be viewed as more than simply one of the more recent panaceas in a long string of managerial quick fixes that have surfaced over the years. The principal challenge to management researchers is to identify the entrepreneurial processes that lead to various forms of corporate entrepreneurship, and then to theoretically predict and empirically verify the forms of this phenomenon that produce the best results for firms in various business and industry contexts. Admittedly, this is a tough challenge. However, the pay-off in terms of improved firm performance should be substantial. REFERENCES Beer, M., Eisenstat, R., & Spector, B. (1990). The critical path to corporate renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Bhide, A. (1986). Hustle as a strategy. Harvard Business Review, 64(5), 59-65. Block, Z., & MacMillan, I. C. (1993). Corporate venturing: Creating new businesses within the firm. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. Burgelman, R. A. (1983). A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(2), 223-244. Burgelman, R. A., Kosnik, T. I. & van den Pol, M. (1988). Toward an innovative capabilities audit framework. In R. A. Burgelman, M. A. Maidique, (Eds.), Strategic management oftechnology and innovation, pp. 31-44. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Covin, J. G. (1991). Entrepreneurial versus conservative firms: A comparison of strategies and performance. Journal of Management Studies. 28, 439-462. Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). The strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75-87. Covin.J, G., & Slevin, D. P. (1990). New venture strategic posture, structure, and performance: An industry life cycle analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 5, 123-135. Dean, C. C. (1993). Corporate entrepreneurship: Strategic and structural correlates and impact on the 60 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE global presence of United States firms. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas, Denton, TX. Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & Covin, J. G. (1997). Entrepreneurial strategy making and firm performance: Tests of contingency and configurational models. Strategic Management Journal, 18(9),677-695. Fahey, L. (1989). Bypass strategy: Attacking by surpassing competitors. In L. Fahey, (Ed.), The strategic planning management reader, pp. 189-193. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Golder, P. N., & Tellis, G. J. (1993). Pioneer advantage: Marketing logic or marketing legend. Journal of Marketing Research, 30, 158-170. Guth, W. D., & Ginsberg, A. (1990). Guest editor's introduction: Corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 11(Summer), 5-16. Hamel, G. (1997). Killer strategies that make shareholders rich. Fortune, 135(12),70-84. Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Strategic intent. Harvard Business Review, 67(3), 63-76. Hills, G. E., & LaForge, R. W. (1992). Marketing and entrepreneurship: The state of the art. In D. L. Sexton, & J. D. Kasarda (Eds.), The state of the art of entrepreneurship, pp. 164-190. Boston: PWS-Kent. Hunt, S. D. (1983). Marketing theory: The philosophy of marketing science. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Hurst, D. K., Rush, J. C., & White, R. E. (1989). Top management teams and organizational renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 10 (Summer), 87-105. Jelinek, M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1990). The innovation marathon: Lessons from high technology firms. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Jennings, D. F., & Lumpkin, J. R. (1989). Functionally modeling corporate entrepreneurship: An empirical integrative analysis. Journal of Management, 15, 485-502. Kanter, R. M. (1982). The middle manager as innovator. Harvard Business Review, 60(4),95-106. Karagozoglu, N., & Brown, W. B. (1988). Adaptive responses by conservative and entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 5, 269-281. Khandwalla, P. N. (1987). Generators of pioneering-innovative management: Some Indian evidence. Organization Studies, 8(1), 39-59. Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172. Maidique, M. A., & Hayes, R. H. (1984). The art of high technology management. Sloan Management Review, 25(2), 17-31. Miles, M. P., & Arnold, D. R. (1991). The relationship between marketing orientation and entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 15(4),49-65. Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29, 770-791. Miller, D. (1990). The Icarus paradox. New York: HarperCollins. Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1982). Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3( I), 1-26. Morris, M. H., Davis, D. L., & Allen, J. W. (1994). Fostering corporate entrepreneurship: Cross-cultural Spring. 1999 61 comparisons of the importance of individualism versus collectivism. Journal of International Business Studies, 21, 65-89. Morris, M. H., & Paul, G. W. (1987). The relationship between entrepreneurship and marketing in established firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 2, 247-259. Morse, E. A. (1996). Current thought in firm level entrepreneurship. Paper presented at the 1996 Western Academy of Management meeting. Narnan, 1. L., & Slevin, D. P. (1993). Entrepreneurship and the concept of fit: A model and empirical tests. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 137-153. Pinchot, G. (1985). Intrapreneuring: Why you don't have to leave the company to become an entrepreneur. New York: Harper & Row. Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. New York: Free Press. Ramachandran, K., & Ramnayaran, S. (1993). Entrepreneurial orientation and networking: Some Indian evidence. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(6),513-524. Schollhammer, H. (1982). Internal corporate entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, K. H. Vesper, (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship, pp. 209-229. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Schwenk, C. R., & Tang, M. (1989). Economic and psychological explanations for strategic persistence. Omega, 17, 559-570. Shane, S. A. (1994). Are champions different from non-champions? Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 397-421. Simons, R. (1994). How new top managers use control systems as levers of strategic renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 169-189. Smart, D. T., & Conant, 1. S. (1994). Entrepreneurial orientation, distinctive marketing competencies and organizational performance. Journal of Applied Business Research, 10(3), 28-38. Stalk, G., Jr. (1988). Time-The next source of competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review, 66(4), 41-51. Stevenson, H. H., & Gumpert, D. (1985). The heart of entrepreneurship. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 85-95. Stevenson, H. H., & Jarillo, J. C. (1990). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. Strategic Management Journal, 11, Summer, 17-27. Stopford, J. M., & Baden-Fuller, C. W. F. (1990). Corporate rejuvenation. Journal of Management Studies, 27(4), 399-415. Stopford, J. M., & Baden-Fuller, C. W. F. (1994). Creating corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 521-536. Venkatraman, S., MacMillan, I., & McGrath, R. (1992). Progress in research on corporate venturing. In D. L. Sexton, & 1. D. Kasarda, (Eds.), The state of the art of entrepreneurship, pp. 487-519. Boston: PWS-Kent. Zahra, S. A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 259-285. Zahra, S. A. (1993). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behavior: A critique and extension. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 17(4), 5-21. 62 ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE Zahra, S. A. (1997). Governance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: The moderating impact of industry technological opportunities. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1713-1735. Zahra, S. A., & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(1),43-58. Jeffrey G. Covin is Professor of Strategic Management and the Hal and John Smith Chair of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Morgan P. Miles is Professor of Marketing at Georgia Southern University. He is currently visiting the University of Cambridge as a Senior Research Associate. The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers, Michael Heeley, Patricia McDougall, and Shaker Zahra for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Spring. 1999 63