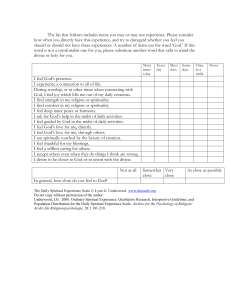

Original Article The Role of Religiosity in Symptom Expression of Advanced Cancer Patients American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine® 2022, Vol. 39(6) 7 05­–709 ª The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/10499091211041349 journals.sagepub.com/home/ajh Sebastiano Mercadante, MD1 , Claudio Adile, MD2, Marianna Ricci, MD3, Marco Maltoni, MD3, Giuseppe Bonanno, MD2, and Alessandro Casuccio, BS4 Abstract Aim: The aim of this study was to assess the religious pattern and its impact on symptom expression in patients with advanced cancer. Methods: A consecutive sample of advanced cancer patients screened at admission to palliative care. Standard epidemiological data were recorded. Patients were asked about their religious beliefs, the degree of social relationship to existing religions, the role of religion in their life, and the frequency of their prayer. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) and Hospital Anxiety Depression scale (HADS) were assessed. Results: Two-hundred-eighty-three patients were screened. Age and gender were found to be independently correlated with religious belief (p ¼ 0.042 and p ¼ 0.016, respectively). Gender (females, p ¼ 0.026), age (p ¼ 0.003), lower Karnofsky performance status (KPS) (p ¼ 0.022), and higher values of HADS-A (p ¼ 0.003) were independently correlated with the degree of social relationship to existing religions. Gender (females, p ¼ 0.002), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.005), and higher values of HADS-A (p ¼ 0.04) were independently correlated with a more relevant role of religiosity. Gender (females, p < 0.0005), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.001), and drowsiness (p ¼ 0.05) were independently correlated with frequency of prayer. Conclusion: The more the patients have demanding religious issues, the greater the state of anxiety, particularly in older and female patients with a lower KPS. The religious pattern did not have relevant role in the expression of other symptoms included in the ESAS. Keywords palliative care, advanced cancer, religiosity, anxiety Introduction The lives of healthy and severely ill people are based on a variety of conceptual matrices, consisting of philosophical, spiritual, and religious convictions, which are particularly relevant in the process of the end of life. At the end of life, patients experience complex physical, psychosocial, and existential concerns. They have to face the fear of suffering, disability, helplessness, isolation, and impending death, that constitute the individual spirituality.1 Patients’ spirituality may serve as a buffer against depression, hopelessness, desire for death, and existential suffering, providing them with a sense of well-being by giving structure and meaning to their difficult experience.2 Some studies of advanced cancer patients have assessed the spiritual distress or spiritual pain, which were found to be associated with poorer quality of life, being younger, lower Karnofsky performance status (KPS), higher physical distress, anxiety or depression, and decreased religiosity and religious coping. 3 Spiritual pain was found in more than 40% of advanced cancer patients and it was correlated with physical and psychological distress.4 It has been reported that spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain may influence symptom distress, quality of life, and coping strategies of patients with advanced and terminal illness. On the other hand, spirituality and religiosity also can be used as integrative therapy to promote general well-being and health.4-7 However, spirituality is a broad concept that may vary in meaning among individuals.5,6 Spirituality is a concept often unknown for many subjects and is also unresolved among anthropologists, sociologists, and philosophers. In some preliminary interviews before starting the study, we recognized the concept of spirituality was difficult to express for us and aboveall, to understand for patients. Religion is a set of beliefs about humanity and divinity which can be experienced as a sense of belonging, for example due to family tradition. It influences the development of attitudes in certain circumstances of life, particularly in the 1 La Maddalena Cancer Center, Via San Lorenzo, Palermo, Sicily, Italy Private Hospital La Maddalena Palermo, Sicilia, Italy 3 Palliative Care Unit, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori”, Meldola, Italy 4 Università di Palermo ITAF Palermo, Sicilia, Italy 2 Corresponding Author: Sebastiano Mercadante, La Maddalena cancer center, Via San Lorenzo 312, Palermo, Sicily 90146, Italy. Email: terapiadeldolore@lamaddalenanet.it ® ® American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 39(6) American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 2706 late-stage cancer, which is associated with a relevant symptom burden. People could be more confident with this term. The role of religiosity and the intensity with which it is experienced with regard to the expression of symptoms have never been asessed. The aim of this study was to assess the religious pattern and possible associations with symptom expression in patients with advanced cancer. Methods A consecutive sample of advanced cancer patients admitted to 2 palliative care units in Italy in a period of 6 months (JanuaryJune 2020) was selected. Advanced cancer was determined as a relapse, a metastasis or a local advanced disease. The protocol was approved by the local ethical committee. Inclusion criteria were: age �18 yrs, a diagnosis of advanced cancer. Exclusion criteria were: incapacity to complete the questions due to cognitive or linguistic problems and a Karnofsly performance status of � 20. Cognitive status was assessed by using the memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS).8 All patients meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria accepted to participate in the study. Table 1. Religious Belief, Level of Religiosity, Role of Religiosity in Patients’ Life, and Frequency of Prayer. Religious belief Catholic Orthodox Protestant Muslim Atheism Other Level of religiosity Non believer Believer Believer and practicing Role of religiosity in patients’ life Fundamental Important Fairly important Poorly important Irrelevant Frequency of prayer Daily Weekly monthly yearly never missed 252 (89%) 4 (1.4%) 9 (3.2%) 3 (1.1%) 12 (4.2%) 3 (1.1%) 15 (5.3%) 177 (62.5%) 91 (32.2%) 52 (18.4%) 89 (31.4%) 78 (27.6%) 48 (17%) 16 (5.7%) 131 (46.3%) 44 ( 15.5% 39 (13.8%) 10 (3.5%) 58 (20.5%) 1 Measurements Standard epidemiological data, including age, gender, primary cancer diagnosis, and Karnosky performance status were recorded. KPS expresses the functional capacity on a scale from 0 to 100.9 Patients were asked about their religious beliefs (Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Muslim, atheism et al), the degree of social relationship with existing religions (non believer, believer, believer and practicing), the role of religion in their life (fundamental, important, fairly important, poorly important, irrelevant), and the frequency of their prayer (daily, weekly, monthly, yearly, never). Other measurement tools included the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS), that is a tool assessing the intensity of most common psychological and physical symptoms, largely validated and reliable for assessing the global symptom burden,10 and HADS (Hospital Anxiety Depression scale), that is a tool consisting of 14 items, with 2 subscales for anxiety and depression. The total score ranges from 0 to 42, with a higher score indicating severe depression and anxiety.11 Statistics The data are expressed as a mean + SD, or frequency (%). Multinomial logistic regression analysis examined the correlation between patient characteristics (independent variables) and religious belief, the degree of social relationship to existing religions, the role of religion in their life, and the frequency of their prayer (dependent variables). All variables that were found to be significantly associated (P � 0.05) at the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate regression model. The data were analyzed by the SPSS software, version 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). All P-values were bilateral and P � 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results Two-hundred-eighty-three patients met the inclusion and exclusion criteria in the period taken into consideration. Onehundred-thirty-three patients were males. The mean age was 63.8 years (range 24-87, SD 11.7), and 133 patients (47%) were males. The mean KPS was 69.5 (range 30-100, SD 20.6). Primary tumors were in a rank order: gastrointestinal n.70 (24.7), lung n.45 (15.9%), pancreas n.33 (11.7%), breast n.24 (8.5%), gynecologic n.21 (7.4%), urinary n.20 (7.1%), prostate n. 9(3.2%), head & neck n.18 (6.4%), liver n.11 (3.9%), brain n.5 (1.8%), hematologic n.3 (1.1%), others n.24 (8.5%). Data regarding religious belief, the degree of social relationship to existing religions, role of religiosity in patients’ life, and frequency of prayer are reported in Table 1. Data regarding ESAS items, MDAS, HADS-A, HADS-D, and total HADS are showed in Table 2. Religious Belief In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, religious belief was correlated with age (younger, p ¼ 0.029), KPS (lower in Catholics, P ¼ 0.035), gender (males were more ateist, p ¼ 0.014). No statistical correlations between religious belief and ESAS items, HADS-A, HADS-D, and total HADS were found (P ¼ >0.05). In the multivariate analysis, age, gender (females) and KPS were found to be independently correlated Mercadante et Mercadante et al al 707 3 Table 2. Mean and SD (Standard Deviation) of ESAS Items, MDAS, HADS-A, HADS-D, and Total HADS (See Text). Table 3. Univariate and Multivariate Analysis. Univariate analysis SD Pain Weakness Nausea Depression Anxiety Poor appetite Poor well-being Dyspnea Drowsiness Total ESAS MDAS HADS-A HADS-D Total HADS 3.0 4.9 1.4 2.8 3.5 4.1 4.9 1.4 3.0 28.9 2.2 6.9 7.0 13.9 2.8 2.9 2.3 3.0 3.1 3.3 2.6 2.5 3.1 12.7 2.4 4.5 4.0 7.9 with religious belief (p ¼ 0.042, p ¼ 0.016, and p ¼ 0.027, respectively) (Table 3). Multivariate analysis* Religious belief Variables OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p Age Gender Karnofsky 0.90(0.82-0.99) 0.08(0.01-0.60) 1.03(1.02-1.07) 0.029 0.014 0.035 0.95(0.9-0.97) 0.07(0.01-0.63) 1.04(1.01-1.07) 0.042 0.016 0.027 Level of religiosity Variables Age Gender Karnofsky Depression Anxiety Total ESAS HADS-A TOTAL HADS OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p 1.04(1.01-1.06) 1.8(1.1-3.1) 1.03(1.01-1.07) 1.1(1.01-1.2) 1.1(1.01-1.2) 1.03(1.01-1.05) 1.1(1.03-1.2) 1.04(1.01-1.07) 0.006 0.024 0.015 0.029 0.028 0.018 0.003 0.041 1.03(1.01-1.07) 1.9(1.1-3.3) 1.04(1.01-1.07) 0.003 0.026 0.022 1.3(1.1-1.6) 0.003 Role of religiosity in patients’ life Degree of Social Relationship to Existing Religions In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, the level of religiousness was correlated with gender and age (females and older, p ¼ 0.024 and p ¼ 0.006, respectively), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.015), depression (P ¼ 0.029), anxiety (P ¼ 0.028), total ESAS (P ¼ 0.018), HADS-A (P ¼ 0.003), and total HADS (P ¼ 0.041). In the multivariate analysis, gender (females, p ¼ 0.026), age (p ¼ 0.003), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.022), and higher values of HADS-A (p ¼ 0.003) were independently correlated with degree of social relationship to existing religions (Table 3). Variables OR 95% CI Gender Karnofsky HADS-A TOTAL HADS 8.9(2.2-35.5) 0.9(0.8-0.95) 1.3(1.1-1.5) 1.1(1.03-1.2) p OR 95% CI p 0.002 0.003 0.004 0.013 9.9(2.4-41.5) 0.93(0.92-0.98) 1.5(1.12.4) 0.002 0.005 0.04 Frequency of prayer Variables Gender Karnofsky Drowsiness OR 95% CI p OR 95% CI p 5.6(2.8-11.0) <0.0005 6.5(3.2-13.2) <0.0005 0.97(0.95-0.98) 0.001 0.97(0.95-0.98) 0.001 1.1(1.05-1.3) 0.036 1.1(1.05-1.3) 0.05 Role of Religiosity in Patients’ Life Discussion In the multinomial logistic regression analysis gender (females, p ¼ 0.002), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.003), HADS-A (P ¼ 0.004), and total HADS (P ¼ 0.013) were correlated with a more relevant role of religiosity. In the multivariate analysis, gender (females, p ¼ 0.002), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.005), and higher values of HADS-A (p ¼ 0.04) were independently correlated with a more relevant role of religiosity (Table 3). The findings of this study revealed interesting aspects on the role of religion profile on symptom expression of advanced cancer patients. Most patients were Catholic, according to a secular tradition of this country. However, belonging to a religious pattern does not often corresponds to the same attitudes in the relationship of supernatural. Believers are not often practicing, religion may have a minor role in patients’ life, or praying is not considered to be necessary. Thus, it is evident that there are different levels of religiosity. Older patients, those with a lower KPS, and females resulted to be Catholic believers. Females, age, a lower KPS, and higher values of anxiety were correlated with being believer and practicing. Similarly, a relevant role of religiosity in patients’ life was more likely to be found in females, in patients with a lower KPS, and higher levels of anxiety. Finally, gender, a lower KPS, and drowsiness were strongly correlated with frequency of prayer. All these data suggest that the more the patients have demanding religious attitudes or Frequency of Prayer In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, the frequency of prayer was correlated with gender (females, p < 0.0005), lower level of KPS (p ¼ 0.001), and drowsiness (p ¼ 0.036). In the multivariate analysis, gender (females, p < 0.0005), lower KPS (p ¼ 0.001), and drowsiness (p ¼ 0.05) were independently correlated with frequency of prayer (Table 3). 4708 consider important their religion, the greater the state of anxiety. On the other hand religious attitudes might be determined oppositely according to their level of anxiety. Thus, the more anxiety religious people feel, the more they are driven to pray. For example, patients might fail to decrease their anxiety by superficial religious attitudes or behaviors, although increasing the frequency of prayer. The relationship between anxiety and religious attitudes remains to be better explored in future studies. These attitudes were more frequently observed in older and female patients with a lower KPS. Of interest, these attitudes did not have relevant role in the expression of other symptoms, particularly in the ESAS physical items. The role of religion has been variably assessed in advanced cancer patients, although the assessment methods and purpose of studies were different, with a major focus on spirituality, that could be defined as a personal search for meaning and purpose in life.1 Some aspects, such as spiritual pain, for example, are difficult to explore. Studies provided controversial data.3-5,12-17 When tested in our population, it was difficult to understand and hardly measurable, probably having different meanings in individuals, particularly those with poor cultural background. More recently, in a study performed in Latin-American patients, spirituality and religiosity were associated with positive coping strategies and higher levels of quality of life. Spiritual pain was also frequent and was associated with physical and psychosocial distress.7 Indeed, the concept of religion involves an organized entity with rituals and practices about a higher power or God. Previous studies assessed the spirituality, the spiritual distress or spiritual pain. In the present study a more understandable concept was examined. The religious “intensity” of advanced cancer patients was more objective and easily measurable, differently from an abstract concept of spirituality, which is difficult to measure, because it may have different meanings among patients. The word was clearly understood by patients during the interviews. Religiosity as a whole has been found to be associated with a greater level of anxiety. Existing data in the setting of palliative care are limited. While early studies showed the religious faith or praying could help relieve death anxiety or pain in societies which are generally religious,18-20 religion does not necessarily have a positive effect on health or lead to a reduction in death anxiety.21 Some papers, prevalently examining religious coping, reported the religiousness was associated with better quality of life. As a part of a study of advanced cancer patients assessed for the prevalence of mental illness and patterns of mental health service utilization, structured interviews showed that a greater use of positive religious coping may play an important role for the quality of life of patients. Types of religious coping strategies used were related to better or poorer quality of life.22 In patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy, spirituality and religious coping were associated with improved quality of life, when patients considered themselves to be spiritual.23 Prayer was significantly related with pain tolerance, but not with pain severity.24 A significant association between praying ® ® American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine 39(6) American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine and pain interference and impairment has been reported. Moreover, praying was associated with anxiety and depression scores.25 It has been reported that very religious patients did find their faith a source of strength, and religion was of little help to them.2 On the other hand, physicians have observed that the absence of religion was associated with higher invasive behaviors.26 Of interest, in most advanced cancer patients, spiritual needs were not supported by religious communities or the medical system, and spiritual support was associated with better quality of life. Moreover, religious individuals more frequently wanted aggressive measures to extend life.27 This study has several limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study it is difficult to establish causality between the religious intensity and other physical and emotional symptoms (particularly anxiety). More studies should be performed to establish if the religion pattern may influence the response to symptomatic treatments. In this study, most patients professed Catholics and the number of other religions was limited, so that differences among religions on a large scale were not reliable and the possible impact of these differences on symptom expression unsearchable. The questionnaire used for this study was not validated, as the many others used in this often ambiguous field. However, this appeared easy to understand, repeatable, and meaningful. Religion can be used in different ways (for example coping) and this could also lead to more positive or adverse associations with psychological outcomes. Thus, the kind of religious coping could affect the linkage between religiosity-psychological outcomes as well. Finally, it should be underlined that this paper did not assessed the role of spiritual or existential issues on patients’ symptom expressions and was based only on religious attitudes. Indeed, the concept of religiousness is more concrete and a significant relationship with symptoms may be interesting for future research in a secularized society like that of a Mediterranean country. In conclusion the findings of this study suggest that the more the patients have more demanding religious attitudes, the greater the state of anxiety, particularly in older and female patients with a lower KPS. The religious pattern did not have relevant role in the expression of other symptoms included in the ESAS. There is a need for qualitative data and the use of validated measures of religiousness, religious coping and spiritual struggle. Further studies in different countries with different religious beliefs should be performed to provide insides on the role of religiosity in advanced cancer patients. Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ORCID iD Sebastiano Mercadante https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9859-6487 Mercadante et Mercadante et al al References 1. Tanyi R. Towards a clarification of the meaning of spirituality. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(5):500-509. 2. Byrne CM, Morgan DD. Patterns of religiosity, death anxiety, and hope in a population of community-dwelling palliative care patients in New Zealand-what gives hope if religion can’t? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37(5):377-384. 3. Pérez-Cruz PE, Langer P, Carrasco C, et al. Spiritual pain is associated with decreased quality of life in advanced cancer patients in palliative care: an exploratory study. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(6):663-669. 4. Delgado-Guay MO, Chisholm G, Williams J, Frisbee-Hume S, Ferguson AO, Bruera E. Frequency, intensity, and correlates of spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients assessed in a supportive/ palliative care clinic. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(4):341-348. 5. Cadge W, Bandini J. The evolution of spiritual assessment tools in healthcare. Society. 2015;52:430-437. 6. Koening HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012;278730. 7. Delgado-Guay MO, Palma A, Duarte E, et al. Association between spirituality, religiosity, spiritual pain, symptom distress, and quality of life among Latin American patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter study [published online ahead of print]. J Palliat Med. 2021. doi:10.1089/jpm.2020.0776 8. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, Smith MJ, Cohen K, Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(3):128-137. 9. Clancey JK. Karnofsky Performance Scale. J Neurosci Nurs. 1995;27(4):220. 10. Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(3):630-643. 11. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. 12. Hui D, de la Cruz M, Thorney S, Parsons HA, Delgado-Guay M, Bruera E. The frequency and correlates of spiritual distress among patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(4):264-270. 13. Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5): 1106-1113. 14. Delgado-Guay MO, Hui D, Parsons HA, et al. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(6):986-994. 709 5 15. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Hui D, De la Cruz MG, Thorney S, Bruera E. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among care-givers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(5):455-461. 16. Peteet JR. Spiritually integrated treatment of depression: a conceptual framework. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:124370. 17. Gijsberts MHE, Liefbroer AI, Otten R, Olsman E. Spiritual care in palliative care: a systematic review of the recent European literature. Med Sci (Basel). 2019;7(2):25. 18. Neimeyer R, Currier J, Coleman R, Tomer A, Samuel E. Confronting suffering and death at the end of life: the impact of religiosity, psychosocial factors, and life regret among hospice patients. Death Stud. 2011;35(9):777-800. 19. Illueca M, Doolittle B. The use of prayer in the management of pain: a systematic review. J Relig Health. 2020;59(2): 681-699. 20. Dezutter J, Robertson LA, Luycks K, Hutsebaut D. Life satisfaction in chronic pain patients: the stress-buffering role of the centrality of religion. J Sci Study Relig. 2010;49(3): 507-516. 21. Pargament K, Smith B, Koenig H, et al. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37:710-724. 22. Tarakeshwar N, Vanderwerker LC, Paulk E, Pearce MJ, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Religious coping is associated with the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3): 646-657. 23. Vallurupalli M, Lauderdale K, Balboni MJ, et al. The role of spirituality and religious coping in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(2):81-87. 24. Dezutter J, Waachholtz A, Corveleyn A. Prayer and pain: the mediating role of positive re-appraisal J Behav Med. 2011; 34(6):542-549. 25. Anderson G. Chronic pain and praying to a higher power: useful or useless? J Relig Health. 2008;47(2):176-187. 26. Dos Anjos CS, Borges RMC, Chaves AC, et al. Religion as a determining factor for invasive care among physicians in end-of-life patients. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(2): 525-529. 27. Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):555-560. Copyright of American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine is the property of Sage Publications Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.