DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

1

PRO – GREAT POWER COMPETITION GOOD ....................................................................................................................3

CHINA ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4

China Threat ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 5

Deterrence Key to Prevent China’s Aggression ........................................................................................................................ 50

China is a Threat/Is Not Defensive ............................................................................................................................................... 57

China Tech Dominance ...................................................................................................................................................................... 63

Threat to Taiwan ................................................................................................................................................................................. 65

AT: Thucydides Trap---Turn ............................................................................................................................................................ 79

RUSSIA.............................................................................................................................................................................................................81

Russia Makes GPC Inevitable ................................................................................................................................................ 82

Russia Threat * .......................................................................................................................................................................... 90

War Impacts .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 91

Russian Revisionism ........................................................................................................................................................................... 94

Putin Revisionism ............................................................................................................................................................................. 104

Threat to Europe............................................................................................................................................................................... 107

Russia Grey Zone ............................................................................................................................................................................... 111

Need Hard Power to Stop Russia ................................................................................................................................................ 113

Threat to World ................................................................................................................................................................................ 126

Russisa/China Threat ..................................................................................................................................................................... 128

AT: NATO’s Fault ............................................................................................................................................................................... 133

AT: Retrenchment Solves ............................................................................................................................................................... 140

AT: Losing in Ukraine ...................................................................................................................................................................... 141

AT: Sanctions Solve .......................................................................................................................................................................... 144

AT: Can’t Fight NATO ...................................................................................................................................................................... 145

AT: Cooperation Solves ................................................................................................................................................................... 148

AT: Humiliation Turn ...................................................................................................................................................................... 151

Abandoning GPC Means Russia Invasion ................................................................................................................................ 155

Answers to: GPC Caused Ukraine Invasion ............................................................................................................................. 160

Cyber Threat ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 165

Cyber Threat to the US ................................................................................................................................................................... 179

Need More Cyber Defense .............................................................................................................................................................. 181

Need Offensive Cyber Operations ............................................................................................................................................... 185

NATO Good .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 187

RUSSIA/CHINA COMBINED ....................................................................................................................................................................... 206

2AC---AT: Spheres of Influence .................................................................................................................................................... 213

ALTERNATIVES FAIL .................................................................................................................................................................................. 214

Multipolarity Fails ............................................................................................................................................................................ 215

Multilateralism Fails ....................................................................................................................................................................... 218

US Not Overstretched ...................................................................................................................................................................... 229

A2: Offshore Balancing Solves ..................................................................................................................................................... 239

International Cooperation Fails ................................................................................................................................................. 256

Soft Power Answers ......................................................................................................................................................................... 260

A2: China Alternative ...................................................................................................................................................................... 263

HEGEMONY GOOD ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 274

CON -- GREAT POWER COMPETITION BAD ................................................................................................................ 285

DOMESTIC OVERSTRETCH......................................................................................................................................................................... 286

GLOBAL WAR .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 288

DISEASE SPREAD ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 289

RACISM/IMPERIALISM .............................................................................................................................................................................. 291

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

2

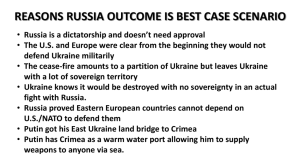

RUSSIA.......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 295

GPC Means War with Russia ........................................................................................................................................................ 296

Russia Threat Defense .................................................................................................................................................................... 300

NATO Bad ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 316

European Military Independence Better ................................................................................................................................. 353

CHINA ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... 356

Security Dilemma ............................................................................................................................................................................. 357

GPC Against China Means War ................................................................................................................................................... 361

China Threat (General) Answers (Defense) ........................................................................................................................... 405

No China Revisionism ...................................................................................................................................................................... 421

No China war ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 429

Accidental War Answers ................................................................................................................................................................ 434

No Existential Threat ...................................................................................................................................................................... 437

China Won’t Replace US Hegemony .......................................................................................................................................... 439

AT: China Economic Downturn Means Lashout ................................................................................................................... 442

AT: China Has Lots of Missiles/Weapons ................................................................................................................................ 444

China Won’t Push the US Out of Asia ........................................................................................................................................ 445

China Does Not Threaten the US ................................................................................................................................................ 447

No Nuclear Escalation .................................................................................................................................................................... 450

Doshi and Pillsbury Indite ............................................................................................................................................................. 452

China Threat Inflation .................................................................................................................................................................... 454

Allies Turn ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 464

Taiwan Defense ................................................................................................................................................................................. 465

Taiwan War Offense ........................................................................................................................................................................ 469

China Threat (South China Sea) Answers ............................................................................................................................... 471

Alternative – Spheres of Influence ............................................................................................................................................. 473

US OVERSTRETCHED ................................................................................................................................................................................. 475

Heg Unsustainable ........................................................................................................................................................................... 476

US Decline Now ................................................................................................................................................................................. 490

GPC LEADS TO GPW................................................................................................................................................................................. 495

GPW LIKELY............................................................................................................................................................................................... 498

ALTERNATIVES ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 504

Multipolarity ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 505

Offshore Balancing Solves ............................................................................................................................................................. 507

Multipolarity is Peaceful ................................................................................................................................................................ 511

US GLOBAL LEADERSHIP GENERALLY BAD ........................................................................................................................................... 514

US LEADERSHIP NOT KEY TO GLOBAL PEACE ...................................................................................................................................... 545

OTHER CONTENTION ANSWERS .............................................................................................................................................................. 559

US Credibility Answers.................................................................................................................................................................... 560

Democracy Answers ........................................................................................................................................................................ 562

Global Order Answers ..................................................................................................................................................................... 564

Global Prolif Answers ...................................................................................................................................................................... 566

Reducing Commitments Not Bad | Prolif Answers .............................................................................................................. 567

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

PRO – Great Power Competition Good

3

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

4

China

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

5

China Threat

China is revisionist – territorial expansion, 5-year plans, and anti-democratic

innovation on all fronts

Beckley 22 – Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, associate professor

at Tufts University (Michael, March/April 2022, "Enemies of My Enemy," Foreign Affairs,

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2021-02-14/china-new-world-order-enemies-my-enemy)//KH

ENTER THE DRAGON

There has never been any doubt about what China wants, because Chinese

leaders have declared the same objectives for

decades: to keep the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in power, reabsorb Taiwan, control the East China

and South China Seas, and return China to its rightful place as the dominant power in Asia and the most

powerful country in the world. For most of the past four decades, the country took a relatively patient and peaceful approach to achieving

these aims. Focused on economic growth and fearful of being shunned by the international community, China adopted a “peaceful rise”

strategy, relying primarily on economic clout to advance its interests and generally following a maxim of the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping:

“Hide your strength, bide your time.”

In recent years, however, China

has expanded aggressively on multiple fronts. “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy has

replaced friendship diplomacy. Perceived slights from foreigners, no matter how small, are met with

North Korean–style condemnation. A combative attitude has seeped into every part of China’s foreign policy, and it is confronting

many countries with their gravest threat in generations.

This threat is most apparent

in maritime East Asia, where China is moving aggressively to cement its vast

territorial claims. Beijing is churning out warships faster than any country has since World War II, and it

has flooded Asian sea-lanes with Chinese coast guard and fishing vessels. It has strung military outposts

across the South China Sea and dramatically increased its use of ship ramming and aerial interceptions to

shove neighbors out of disputed areas. In the Taiwan Strait, Chinese military patrols, some involving a dozen warships

and more than 50 combat aircraft, prowl the sea almost daily and simulate attacks on Taiwanese and

U.S. targets. Chinese officials have told Western analysts that calls for an invasion of Taiwan are

proliferating within the CCP. Pentagon officials worry that such an assault could be imminent.

China

has gone on the economic offensive, too. Its latest five-year plan calls for dominating what

Chinese officials call “chokepoints”—goods and services that other countries can’t live without—and then

using that dominance, plus the lure of China’s domestic market, to browbeat countries into concessions. Toward that end, China has

become the dominant dispenser of overseas loans, loading up more than 150 countries with over $1

trillion of debt. It has massively subsidized strategic industries to gain a monopoly on hundreds of vital

products, and it has installed the hardware for digital networks in dozens of countries. Armed with economic

leverage, it has used coercion against more than a dozen countries over the last few years. In many cases, the punishment has been

disproportionate to the supposed crime—for example, slapping tariffs on many of Australia’s exports after that country requested an

international investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

China has also become a potent antidemocratic force, selling advanced tools of tyranny around the

world. By combining surveillance cameras with social media monitoring, artificial intelligence,

biometrics, and speech and facial recognition technologies, the Chinese government has pioneered a system that allows

dictators to watch citizens constantly and punish them instantly by blocking their access to finance, education, employment,

telecommunications, or travel. The apparatus is a despot’s dream, and Chinese companies are already selling and operating aspects of it in

more than 80 countries.

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

6

Western encirclement, aging populations, and attempted expansion prove China is a

volatile revisionist power on the verge of lash-out

Beckley and Brands 21– *Jeane Kirkpatrick Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute,

associate professor at Tufts University; **resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, Henry A.

Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International

Studies. (*Michael and **Hal, January 1, 2021, “Into the Danger Zone - Coming Crisis in US-China

Relations," American Enterprise Institute, Targeted News Service, ProQuest via UMich Libraries,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep27632?seq=1)//KH

Red Flags

Most debate on America's China policy focuses on the dangers of a rising and confident China.3 But the

United States actually faces a more complex and volatile threat: an already powerful but increasingly

insecure China beset by internal problems and a brewing international backlash.

China already has the money and muscle to challenge the United States in key areas. Thanks to decades of rapid

growth, China boasts the world's largest economy (measured by purchasing power parity), manufacturing output,

trade surplus, financial reserves, navy by number of ships, and conventional missile force. Chinese

nationals lead four of the 15 United Nations specialized agencies.4 Chinese investments and loans span

the globe, and Beijing is pushing for primacy in key technologies such as 5G telecommunications and

artificial intelligence (AI).5 Add in that the American-led world order has experienced four years of geopolitical disarray under President

Donald Trump and that much of the world has suffered through many months of a crippling COVID-19 pandemic, and it is hardly

surprising that Beijing is testing the status quo everywhere from the South China Sea to the border with

China.

But China's

geopolitical window of opportunity may be closing as fast as it opened. Since 2007, China's

annual economic growth rate has dropped by more than half, and productivity has declined by nearly 10

percent, meaning that China is spending more to produce less.6 Meanwhile, debt has ballooned eightfold and is on

pace to total 335 percent of gross domestic product by the end of 2020.7 No country has racked up so much debt so fast in peacetime.

China has little hope of reversing these trends, because it is about to suffer the worst aging crisis in

history. Over the next 30 years, China will lose 200 million working-age adults and gain 300 million senior

citizens./8 Any country that has aged, accu-mulated debt, or lost productivity at anything close to China's current pace has lost at least one

decade to near-zero economic growth. And as economic growth falls, the dangers of social and political unrest

rise./9 China's leaders are well aware of these trends./10 President Xi Jinping has given multiple internal

speeches warning party members of the potential for a Soviet-style collapse./11 China's gov-ernment

has outlawed negative economic news, and Chinese elites are moving their money and children out of

the country en masse./12

Meanwhile, China

faces a rising wave of foreign hostility. According to leaked Chinese government reports

and independent Western analyses, nega-tive views of China have soared to highs not seen since the

Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989./13 This surge of anti-China sentiment is a response to Beijing's internal

repression and external assertiveness, and it is now manifesting in ways that threaten to crush China's

geopolitical ambitions. Nearly a dozen countries have suspended or canceled their participation in Belt

and Road Initiative projects./14 Another 16 countries, including eight of the world's 10 largest economies, have

banned or severely restricted use of Huawei products in their 5G networks./15 India has been turning hard

against China, since a clash between the two countries killed 20 soldiers in June. Japan has ramped up military spending,

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

7

turned amphibious ships into aircraft carriers, and strung missile launchers along the Ryukyu Islands near Taiwan, where a

record number of citizens now identify solely as Taiwanese, not Chinese./16 The European Union has labeled China a

"systemic rival," and Europe's three great powers--France, Germany, and the United Kingdom--are

sending naval patrols to counter Beijing's expansion in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean./17

These intensifying

headwinds will make China a less competitive long-term rival to the United States but a

more explosive near-term threat. Simply put, it is hard to see how a country facing so many severe

challenges can ultimately outpace America and its many allies. Yet whereas a rising China could afford to

shelve disputes and deescalate crises--confident that its wealth, power, and status were growing and that the Chinese Communist

Party's (CCP) legitimacy was secure--a slowing and increasingly encircled China will be eager to score geopolitical

wins while it still can. There is no mystery about what China's ambitions are, because the CCP has enshrined them in

national law: to make the Chinese nation whole again; reunite Taiwan with the mainland; control the

East and South China Seas, thereby turning the western Pacific into a Chinese lake; and restore China's status as

a great power. The looming danger is that China will act more aggressively to achieve them as its future prospects

dim.

History Rhymes

If China goes down this ugly path, it wouldn't be the first great power to do so. We

tend to think that rising revisionists pose

the greatest danger to the existing order. "It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this inspired in

Sparta that made war inevitable," Thucydides wrote. But historically, the most desperate dashes have often come from dissatisfied

powers that had been on the ascent but grew worried that their time was running short./18

World War I is the classic example. The growing German challenge to the United Kingdom provided the strategic background to that conflict.

Yet in the foreground in the run-up to 1914 were nagging German fears of decline. The growth of Russian military power and strategic mobility

was menacing the eastern flank. New French conscription laws were changing the balance in the west. A tightening Franco-Russian-British

entente was leaving Germany surrounded. If Berlin did not act quickly, its military strategy--based on fighting a two-front war--would collapse,

its dreams of world power and geopolitical greatness would vanish, and the internal strains caused by intensifying political clashes might

become unmanageable. This was a principal reason Berlin acted so recklessly during the July crisis--by issuing its "blank check" to AustriaHungary and then enacting its plan for a rapid, two-front war--despite the obvious peril, as Chief of General Staff Helmut von Moltke

acknowledged, of a continental war that might "annihilate the civilization of almost the whole of Europe for decades to come."/19

The same decision-making dynamics were present in other cases. Imperial Japan made its fatal gamble in 1941, after the US oil embargo and

naval rearma-ment made it clear that Tokyo's window to dominate the Asia-Pacific was closing fast./20 In the 1970s, Soviet global expansion

peaked as Moscow's military buildup matured and the slowing of the Soviet economy created an impetus to lock in geopolitical gains sooner

than later. Even the United States once fit this pattern. The flurry of American expansion and the buildup of US naval power in the 1890s came

after an economic slump that exacerbated internal tensions and amid a global upsurge of imperial aggran-dizement that left some US

strategists concerned that Washington would be left behind by emerging European mega-empires.

In some of these instances, it

was economic dis-tress following a long period of growth that stoked anxious

aggression. In others, it was the onset of strategic encirclement, often self-provoked, by rival powers. In

all cases, an upsurge in a revisionist state's power gave it the means to challenge the status quo, but an

apparent downturn in its future prospects gave it the motive to do so boldly, even violently. Given that

China is currently facing both a grim economic forecast and tightening strategic encirclement, the next

few years may prove partic-ularly turbulent./21

Failing to effectively counter China causes war — we’re on the brink.

Colby 22 — Elbridge Colby, Co-Founder and Principal of The Marathon Institute—a policy initiative

focused on developing strategies to prepare the United States for an era of sustained great power

competition, Member of the Council on Foreign Relations, former Director of the Defense Program at

the Center for a New American Security, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and

Force Development at the U.S. Department of Defense, Recipient of the Distinguished and Exceptional

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

8

Public Service Awards from the U.S. Department of Defense and of the Superior and Meritorious Honor

Awards from the U.S. Department of State, holds a J.D. from Yale Law School, 2022 (“China, Not Russia,

Still Poses the Greatest Challenge to U.S. Security,” The National Interest, July 1st, Available Online at

https://nationalinterest.org/feature/china-not-russia-still-poses-greatest-challenge-us-security-203228,

Accessed 07-12-2022)

American foreign policy after—indeed, during—the Russo-Ukrainian War should promptly head to the

world’s most decisive region: Asia. This will require that American foreign and defense policy genuinely

put Asia first—in our military investments, in our allocation of political capital and resources, and in

our leaders’ attention.

Nothing that has happened since Russia’s abominable invasion of Ukraine has changed a set of facts:

Asia is the world’s largest market area, and it is growing in global share. Located in the middle of Asia is

China which, alongside the United States, is one of the world’s two superpowers. China’s behavior has

become increasingly aggressive and domineering and appears oriented toward establishing Beijing’s

hegemony over Asia. If Beijing achieves this goal, the resulting consequences for American life will be

dire.

Preventing China from establishing this hegemony over Asia must therefore be the priority of U.S.

foreign policy—even in the face of what is happening in Europe. The simple fact is that Asia is more

important than Europe, and China is a much greater threat than Russia. By way of comparison, Asia’s

economy is roughly twice as large as Europe’s today—but within twenty years it will likely be multiple

times greater. China, in the meantime, has a GDP roughly an order of magnitude larger than Russia’s.

If current trends continue, China appears on a trajectory to achieve its hegemonic ambitions. Beijing

has been building a military distinctly not limited to territorial defense. Rather, it will be capable of

enabling Beijing’s pursuit of much larger and ambitious goals—first by ingesting Taiwan, but not ending

there. Indeed, amidst the furor over the war in Ukraine, Beijing announced yet again that it would

increase its defense spending by 7 percent this year. Meanwhile, despite much talk, the United States

has neglected its military position in Asia, while many of its allies—especially Japan and Taiwan—have

been laggard in maintaining their defenses. As a result, the military balance in Asia has continued to shift

markedly against the United States and our allies. In blunt terms, we are now rapidly approaching, if not

already in, the window of opportunity where China might well decide to attack Taiwan—and we might

lose.

Avoiding this outcome must be the top, overriding priority for U.S. policy. This does not mean Europe is

unimportant or that we should neglect or abandon it. We should actively support Ukraine with weapons

and other forms of support while remaining firmly committed to NATO, albeit with our contributions

being more focused and narrow in scale. But it does mean Asia must be our priority, and genuinely so,

not just rhetorically as has so often been the case in the past.

Because of these factors, shifting our focus to Asia would make sense regardless of how Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine fared. But, if anything, the war in Ukraine and the reaction to it has made it even

more palatable for the United States to turn to Asia. Moscow, while still menacing and dangerous, has

vividly demonstrated that its power is less formidable than many of us had feared. Russia is very likely to

try to recover its strength, but the losses of war and the impact of sanctions are likely to make that

process slow and difficult. At the same time, Europe has stood up, announcing major increases in

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

9

defense spending, supporting Ukraine’s own self-defense, and demonstrating an unprecedented degree

of cohesion in applying sanctions and other forms of pressure on Russia.

The result is that Moscow appears less of a threat than many of us had supposed, while Europeans are

doing more to shoulder their own defense. If anything, this should make the United States more, not

less, ready to focus on Asia. Indeed, in these circumstances, it is actually hard to understand the logic of

increasing America’s focus on Europe. Why would we double down in Europe at the expense of Asia

when there is less of a threat from Russia and more European self-help—all while the danger in the

primary theater only increases?

Yet many in the foreign policy and political elite seem to view the Russo-Ukrainian War as an

opportunity precisely to double down in Europe. Even more, for some, it is a chance to try to turn the

foreign policy clock back to the globe-spanning liberal imperialism of two decades ago.

Washington must resist this temptation like the plague. The breathtakingly hubristic foreign policies of

the 2000s were unwise even in the period of unipolarity, as we have found to our chagrin. As American

leaders sermonized on an end to evil, China rose at our expense; our military expeditions in the Middle

East ended in frustration, when not failure; and we lost our military edge and many of our economic

advantages. But such policies would be even more extraordinarily ill-advised when we are now locked in

a strategic rivalry with a superpower China that is far more powerful than the USSR, Germany, or Japan

ever were. We simply do not have the preponderance of power to waste our resources anymore.

Time, then, to focus on the region and the contest that really matters: the effort to deny China’s

dominance of Asia. We are already well behind in that struggle, and every day we neglect to increase

our focus further increases the chances of crisis, war, and defeat—with grievous consequences for all

Americans.

China is rising – domestic and international infrastructure and agricultural exports

outpace any other nation

McCoy 22 – Alfred McCoy is the J.R.W. Smail Professor of History at the University of WisconsinMadison (Alfred, 2-25-2022, "Will the Fight for Hegemony Survive Climate Change?," Nation,

https://www.thenation.com/article/environment/climate-china-usa-beijing/)//KH

THE RISE OF CHINESE GLOBAL HEGEMONY

China’s rise to world power could be considered not just the result of its own initiative but also of

American inattention. While Washington was mired in endless wars in the Greater Middle East in the decade

following the September 2001 terrorist attacks, Beijing began using a trillion dollars of its swelling dollar

reserves to build a tricontinental economic infrastructure it called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that

would shake the foundations of Washington’s world order. Not only has this scheme already gone a long way

toward incorporating much of Africa and Asia into Beijing’s version of the world economy, but it has

simultaneously lifted many millions out of poverty.

During the early years of the Cold War, Washington funded the reconstruction of a ravaged Europe and the development of 100 new nations

emerging from colonial rule. But as the Cold War ended in 1991, more than a third

of humanity was still living in extreme

poverty, abandoned by Washington’s then-reigning neoliberal ideology that consigned social change to

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

10

the whims of the free market. By 2018, nearly half the world’s population, or about 3.4 billion people, were

simply struggling to survive on the equivalent of five dollars a day, creating a vast global constituency for

Beijing’s economic leadership.

For China, social change began at home. Starting in the 1980s, the Communist Party

presided over the transformation of

an impoverished agricultural society into an urban industrial powerhouse. Propelled by the greatest mass migration

in history, as millions moved from country to city, its economy grew nearly 10 percent annually for 40 years and lifted

800 million people out of poverty—the fastest sustained rate ever recorded by any country. Meanwhile,

between 2006 and 2016 alone, its industrial output increased from $1.2 trillion to $3.2 trillion, leaving

the United States in the dust at $2.2 trillion and making China the workshop of the world.

By the time Washington awoke to China’s challenge and tried to respond with what President Barack Obama called a

“strategic pivot” to Asia, it was too late. With foreign reserves already at $4 trillion in 2014, Beijing launched its Belt and Road

Initiative, while establishing an Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, with 56 member nations and an impressive

$100 billion in capital. When a Belt and Road Forum of 29 world leaders convened in Beijing in May 2017, President Xi Jinping hailed the

initiative as the “project of the century,” aimed both at promoting growth and improving “people’s wellbeing” through “poverty alleviation.” Indeed, two years later a World Bank study found that BRI transportation projects

had already increased the gross domestic product in 55 recipient nations by a solid 3.4 percent.

Amid this flurry of flying dirt and flowing concrete, Beijing

seems to have an underlying design for transcending the

vast distances that have historically separated Asia from Europe. Its goal: to forge a unitary market that will

soon cover the vast Eurasian land mass. This scheme will consolidate China’s control over a continent that is home to 70 percent

of the world’s population and productivity. In the end, it could also break the US geopolitical grip over a region that has

long been the core of, and key to, its global power. The foundation for such an ambitious transnational

scheme is a monumental construction effort that in just two decades has already covered China and much

of Central Asia with a massive triad of energy pipelines, high-speed rail lines, and highways.

To break that down, start with this: Beijing

is building a transcontinental network of natural gas and oil pipelines

that will, in alliance with Russia, extend for 6,000 miles from the North Atlantic Ocean to the South

China Sea.

For the second arm in that triad, Beijing

has built the world’s largest high-speed rail system, with more than

15,000 miles already operational in 2018 and plans for a network of nearly 24,000 miles by 2025. All this, in

turn, is just a partial step toward what’s expected to be a full-scale transcontinental rail system that

started with the “Eurasian Land Bridge” track running from China through Kazakhstan to Europe. In addition to its

transcontinental trunk lines, Beijing plans branch-lines heading due south toward Singapore, southwest through

Pakistan, and then from Pakistan through Iran to Turkey.

To complete its transport triad, China

has also constructed an impressive set of highways, representing (like those

pipelines) a problematic continuation of Washington’s current petrol-powered world order. In 1990, that

country lacked a single expressway. By 2017, it had built 87,000 miles of highways, nearly double the

size of the US interstate system. Even that breathtaking number can’t begin to capture the extraordinary engineering feats

necessary—the tunneling through steep mountains, the spanning of wide rivers, the crossing of deep gorges on towering pillars, and the

spinning of concrete webs around massive cities.

China is revisionist --- Deterrence key

Rogan 19 --- Tom Rogan, BA War Studies from King's College London; MSc Middle Eastern Politics from

The School of Oriental and African Studies; GDL from The College of Law senior fellow with the

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

11

Steamboat Institute, "Signaling a harder edge for 2019, China threatens US carriers, an invasion of

Taiwan, and nuclear war" Jan 3rd 2019, https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/signaling-aharder-edge-for-2019-china-threatens-us-carriers-an-invasion-of-taiwan-and-nuclear-war

In a highly aggressive editorial on Thursday, Chinese state media taunted the U.S. with nuclear weapons,

threatened U.S. aircraft carriers, and called for preparations to invade Taiwan. The editorial reflects

growing Chinese nationalist fury in the face of Trump administration pressure. Offered up by the Global

Times newspaper, a mouthpiece for the hard nationalists, the editorial didn't pull any punches. To

consider what it means for the U.S., let's consider each element in turn. First up, the nuclear taunt: The

year 2019 marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China. We look

forward to seeing the public debut of Chinese deterrence's trump card, the Dongfeng-41

intercontinental ballistic missile. This is a not-so-subtle signal that the Dongfeng-41 will be shown in

public at a military parade later this year. But note the "trump card" language. A personal rebuke of

President Trump, it's a sign of Beijing's growing frustration that the president won't accept an easy deal

to end the current U.S.-China trade war. But back to the nuclear weapon issue. While the Dongfeng-41 is

an impressive nuclear intercontinental ballistic missile platform, it will not fundamentally alter the

nuclear balance of power against the U.S. Instead, the mobile system is designed to strengthen China's

ability to threaten the U.S. up the escalation curve. In tandem with other capabilities in cyberspace, in

space, and with conventional long-range missiles, China is showing it intends to pose a growing threat

across the spectrum of warfare. The U.S. must pursue and posture greater capability to deter China.

Next up is the Global Times' aircraft carrier threat. China should carry out more maritime combat

exercises with live ammunition, especially training to strike aircraft carriers. There is no need to worry

that doing so would make Washington unhappy. Making them concerned is the whole point of the

exercise. This is not terribly surprising. China has a powerful conventional ballistic missile capability

across short, medium, and long ranges. It is also developing hypersonic missiles of the kind recently

mastered by Russia. The import of these threats is in restricting where and how the U.S. Navy can

operate aircraft carriers. But what's most interesting here is the specific Chinese focus on "making

[Washington]" upset." This reflects a Chinese nudge into the ongoing U.S. debate over whether it would

ever attempt to destroy a U.S. aircraft carrier in battle. Some believe that China would not do so in fear

of meeting a massive U.S. response. I'm less sure about that. That leaves us with the threat to Taiwan.

To promote peaceful reunification, the People's Liberation Army should also carry out more

preparations to respond to a military crisis across the Taiwan Straits, formulate various plans such as a

military blockade around the island, destroying military facilities there and preventing external military

interventions, which can be disclosed to the outside world appropriately when necessary. Note the

absurd Orwellian-language here: "[T]o promote peaceful reunification," carry out attack preparations. It

sums up the nature of Chinese President Xi Jinping's regime. Still, Xi views the subjugation of Taiwan to

Chinese rule as of paramount importance to his legacy. And the Chinese president is certainly making

increased references to what he says is Taiwan's inevitable return to Beijing. Yet, in the context of next

year's 70th anniversary of China's capture of Hainan Island from the nationalists, and Taiwan's upcoming

2020 general election, China's military threats to Taiwan must take on more attention. Ultimately, this

editorial is another warning for the U.S. — a warning that challenging China's island imperialism and its

feudal economic strategy is only going to become more complicated. And while growing allied support

for U.S. actions in the Indo-Pacific are positive, in the end, China will only be deterred by America. We

must seek a more constructive relationship and resist China's defining challenge.

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

12

Deterrence solves

Greenert July 20 --- Jonathan W. Greenert, holds the John M. Shalikashvili Chair in National Security

Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research (United States), Tetsuo Kotani Tomohisa Takei John P.

Niemeyer Kristine Schenck, “Navigating Contested Waters: U.S.-Japan Alliance Coordination in the East

China Sea”, asia policy, volume 15, number 3 (july 2020), 1–57, https://www.nbr.org/wpcontent/uploads/pdfs/publications/ap15-3_eastchinasea_rt_july2020.pdf

Thus, the question is whether Beijing intends to occupy the Senkaku Islands through either paramilitary

or military means. So far, Beijing has not indicated that the islands are part of its national rejuvenation,

despite the fact that it claims them as part of Taiwan. Although China could outnumber the JGC and

occupy the islands by paramilitary means, this could escalate into an armed conflict and invite U.S.

intervention, which is still too costly. Therefore, it is less likely that China will seek to physically seize the

Senkaku Islands in the near future. With the CCG’s daily presence in the vicinity of the islands as well as

occasional intrusions into Japan’s territorial waters, Beijing ably demonstrates its opposition to Japanese

control of the Senkaku Islands, which appeals to the Chinese people. However, should Taiwan eventually

be reunified through either peaceful or coercive means, the Senkaku Islands would remain a “lost

territory.” Furthermore, reunification would shift the military balance in the East China Sea dramatically

in favor China. In such a scenario, armed conflict over the Senkaku Islands would become more likely.

Facing China’s assertive attempts to establish a new normal in the East China Sea, Japan has reinforced

its law-enforcement capabilities to deal with paramilitary challenges and bolstered both its own selfdefense force and its alliance with the United States to deal with the PLA’s counter-intervention

capabilities. The ideal scenario is that Beijing will accept peaceful dispute resolution and the rule of law

in the East China Sea, but such a scenario is unlikely as long as Beijing sticks to its nationalist ambitions.

Even if time is on China’s side, Japan and the United States need to maintain a military balance to make

an armed conflict over Taiwan and the Senkaku Islands too costly to Beijing

China represents a revisionist challenge to the military and economic order—weak American responses

embolden Chinese aggression and prompt global wars. Effective balancing preserves stability.

Choi 18—Ji Young Choi, associate professor in the Department of Politics and Government and affiliated

professor in the International Studies Program and East Asian Studies Program at Ohio Wesleyan

University (“Historical and Theoretical Perspectives on the Rise of China: Long Cycles, Power Transitions,

and China's Ascent,” Asian Perspective, Vol. 42, Issue 1, January-March 2018, pages 61-84, Available

through ProQuest)

I have explored in light of historical and theoretical perspectives whether China is a candidate to

become a global hegemonic power. The next question I will address is whether the ascent of China will

lead to a hegemonic war or not. As mentioned previously, historical and theoretical lessons reveal that a

rising great power tends to challenge a system leader when the former's economic and other major

capabilities come too close to those of the latter and the former is dissatisfied with the latter's

leadership and the international rules it created. This means that the rise of China could produce intense

hegemonic competition and even a global hegemonic war. The preventive motivation by an old

declining power can cause a major war with a newly emerging power when it is combined with other

variables (Levy 1987). While a preventive war by a system leader is historically rare, a newly emerging

yet even relatively weak rising power at times challenges a much more powerful system leader, as in the

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

13

case of Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 (Schweller 1999). A historical lesson is that "incomplete

catch-ups are inherently conflict-prone" (Thompson 2006, 19). This implies that even though it falls

short of surpassing the system leader, the rise of a new great power can produce significant instability in

the interstate system when it develops into a revisionist power. Moreover, the United States and China

are deeply involved in major security issues in East Asia (including the North Korean nuclear crisis, the

Taiwan issue, and the South China Sea disputes), and we cannot rule out the possibility that one of these

regional conflicts will develop into a much bigger global war in which the two superpowers are

entangled. According to Allison (2017), who studied sixteen historical cases in which a rising power

confronted an existing power, a war between the United States and China is not unavoidable, but

escaping it will require enormous efforts by both sides. Some Chinese scholars (Jia 2009; Wang and Zhu

2015), who emphasize the transformation of China's domestic politics and the pragmatism of Beijing's

diplomacy, have a more or less optimistic view of the future of US-China relations. Yet my reading of the

situation is that since 2009 there has been an increasing gap between this optimistic view and what has

really happened. It is premature to conclude that China is a revisionist state, but in what follows I will

suggest some important signs that show China has revisionist aims at least in the Asia Pacific and could

develop into a revisionist power in the future. Beijing has concentrated on economic modernization

since the start of pro-market reforms in the late 1970s and made efforts to keep a low profile in

international security issues for several decades. It followed Deng Xiaoping's doctrine: "hide one's

capabilities, bide one's time, and seek the right opportunity." Since 2003, China's motto has been

"Peaceful Rise" or "Peaceful Development," and Chinese leadership has emphasized that the rise of

China would not threaten any other countries. Recently, however, Beijing has adopted increasingly

assertive or even aggressive foreign policies in international security affairs. In particular, China has been

adamant about territorial issues in the East and South China Seas and is increasingly considered as a

severe threat by other nations in the Asia Pacific region. Since 2009, for example, Beijing has increased

naval activities on a large scale in the area of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea. In 2010,

Beijing announced that just like Tibet and Taiwan, the South China Sea is considered a core national

interest. We can identify drastic rhetorical changes as well. In 2010, China's foreign minister publicly

stated, "China is a big country . . . and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact"

(Economist 2012). In October 2013, Chinese leader Xi Jinping also used the words "struggle and achieve

results," emphasizing the importance of China's territorial integrity (Waldron 2014, 166-167).

Furthermore, China has constructed man-made islands in the South China Sea to seek "de facto control

over the resource-rich waters and islets" claimed as well by its neighboring countries (Los Angeles Times

2015). As of now, China's strategy is to delay a direct military conflict with the United States as long as

possible and use its economic and political prowess to pressure smaller neighbors to give up their

territorial claims (Doran 2012). These new developments and rhetorical signals reflect significant

changes in China's foreign policies and signify that China's peaceful rise seems to be over. A rising great

power's consistent and determined policies to increase military buildups can be read as one of the

significant signs of the rising power's dissatisfaction with the existing order and its willingness to do

battle if it is really necessary. In the words of Rapkin and Thompson (2003, 318), "arms buildups and

arms races . . . reflect substantial dissatisfaction on the part of the challenger and an attempt to

accelerate the pace of military catchup and the development of a relative power advantage." Werner

and Kugler (1996) also posit that if an emerging challenger's military expenditures are increasing faster

than those of a system leader, parity can be very dangerous to the international political order. China's

GDP is currently around 60 percent of that of the United States, so parity has not been reached yet.

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

14

China's military budget, however, has grown enormously for the past two decades (double-digit growth

nearly every year), which is creating concerns among neighboring nations and a system leader, the

United States. In addition to its air force, China's strengthening navy or sea power has been one of the

main goals in its military modernization program. Beijing has invested large financial resources in

constructing new naval vessels, submarines, and aircraft carriers (Economist 2012). Furthermore, in its

new defense white paper in 2015, Beijing made clear a vision to expand the global role for its military,

particularly its naval force, to protect its overseas economic and strategic interests (Tiezzi 2015). Sea

power has special importance for an emerging great power. As Mahan (1987 [1890]) explained cogently

in one of his classic books on naval strategy, Great Britain was able to emerge as a new hegemonic

power because of the superiority of its naval capacity and technology and its effective control of main

international sealanes. Naval power has a special significance for China, a newly emerging power, as well

as for both economic and strategic reasons. First, its economy's rapid growth requires external

expansion to ensure raw materials and the foreign markets to sell its products. Therefore, naval power

becomes crucial in protecting its overseas business interests and activities. Second, securing major sealanes becomes increasingly important as they will be crucial lifelines for the supply of energy, raw

materials, and other essential goods should China become involved in a hegemonic war or any other

major military conflict (Friedberg 2011). In light of this, it is understandable why China is so stubborn

over territorial issues in the South China and East China Seas. In fact, history tells us that many rising

powers invested in sea power to expand their global influence, and indeed all the global hegemons

including Great Britain and the United States were predominant naval powers. Another important

aspect is that Beijing is beginning to voice its dissatisfaction with the existing international economic

order and take actions that could potentially change this order. The Chinese economy has overall

benefited from the post-World War II international liberal order, but the Bretton Woods institutions like

the IMF and the World Bank have been dominated by the United States and its allies and China does not

have much power or voice in these institutions. Both institutions are based in Washington, DC, and the

United States has enjoyed the largest voting shares with its veto power. Along with other emerging

economies, China has called for significant reforms, especially in the governing system of the IMF, but

reform plans to give more power to China and other emerging economies have been delayed by the

opposition of the US Congress (Choi 2013). In response to this, Beijing recently took the initiative to

create new international financial institutions including the AIIB. At this moment, it is premature to say

that these new institutions would be able to replace the Bretton Woods institutions. Nonetheless, this

new development can be read as a starting point for significant changes in global economic and financial

governance that has been dominated by the United States since the end of World War II (Subacchi

2015). China's historical legacies reinforce the view that China has a willingness to become a global

hegemon. From the Ming dynasty in the late fourteenth century to the start of the first Opium War in

1839, China enjoyed its undisputed hegemonic position in East Asia. "Sino-centrism" that is related to

this historical reality has long governed the mentality of Chinese people. According to this hierarchical

world view, China, as the most advanced civilization, is at the center of East Asia and the world, and all

China's neighbors are vassal states (Kang 2010). This mentality was openly revealed by the Chinese

foreign minister's recent public statement that I quoted previously: "China is a big country . . . and other

countries are small countries and that is just a fact" (Economist 2012). This view is related to Chinese

people's ancient superiority complex that developed from the long history and rich cultural heritage of

Chinese civilization (Jacques 2012). In a sense, China has always been a superpower regardless of its

economic standing at least in most Chinese people's mind-set. The strong national or civilizational pride

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

15

of Chinese people, however, was severely damaged by "the Century of Humiliation," a period between

the first Opium War (1839) and the end of the Chinese Civil War (1949). During this period, China was

encroached on by the West and invaded by Japan, experienced prolonged civil conflicts, and finally

became a semicolony of Great Britain while its northern territory was occupied by Japan. China's

economic modernization is viewed as a national project to lay an economic foundation to overcome this

bitter experience of subjugation and shame and recover its traditional position and old glory (Choi

2015). Viewed from this perspective, economic modernization or the accumulation of wealth is not an

ultimate objective of China. Rather, its final goal is to return to its traditional status by expanding its

global political and military as well as economic influence. What it ultimately desires is recognition

(Anerkennung), respect (Respekt), and status (Stellung). These are important concepts for

constructivists who see ideational motives as the main driving forces behind interstate conflicts (Lebow

2008). This reveals that constructivist elements can be combined with long cycle and power transition

theories in explaining the rise and fall of great powers, although further systematic studies on it are

needed.Considering all this, China has always been a territorial power rather than a trading state. China

does not seem to be satisfied only with the global expansion of international trade and the conquest of

foreign markets. It also wants to broaden its (particularly maritime) territories and spheres of influence

to recover its traditional political status as the Middle Kingdom. As emphasized previously, the type or

nature and goals or ideologies of a rising power matter. Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan (territorial

powers) experienced rapid economic expansion and sought to expand their territories and influence in

the first half of the twentieth century. For example, during this period Japan's goal was to create the

Japanese empire in East Asia under the motto of the East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere. On the other

hand, democratized Germany and Japan (trading powers) that enjoyed a second economic expansion

did not pursue the expansion of their territories and spheres of influence in the post-World War II era.

Twentiethcentury history suggests that political regimes predicated upon nondemocratic or nonliberal

values and cultures (for instance, Nazism in Germany and militarism in Japan before the mid-twentieth

century, and communism in the Soviet Union during the Cold War) can pose significant challenges to

democratic and liberal regimes. The empirical studies of Lemke and Reed (1996) show that the

democratic peace thesis can be used as a subset of power transition theory. According to their studies,

states organized similarly to the dominant powers politically and economically (liberal democracy) are

generally satisfied with the existing international rules and order and they tend to be status quo states.

Another historical lesson is that economic interdependence alone cannot prevent a war for hegemony.

Germany was one of the main trade partners of Great Britain before World War I (Friedberg 2011), and

Japan was the number three importer of American products before its attack on Pearl Harbor (Keylor

2011). A relatively peaceful relationship or transition is possible when economic interdependence is

supported by a solid democratic alliance between a rising great power and an existing or declining one.

Some scholars such as Ikenberry (2008) emphasize nuclear deterrence and the high costs of a nuclear

war. Power transition theorists agree that the high costs of a nuclear war can constrain a war among

great powers but do not view them as "a perfect deterrent" to war (Kugler and Zagare 1990; Tammen et

al. 2000). The idea of nuclear deterrence is based upon the assumption of the rationality of actors

(states): as long as the costs of a (nuclear) war are higher than its benefits, an actor (state) will not

initiate the war. However, even some rationalists admit that certain actors (such as exceedingly

ambitious risk-taking states) do not behave rationally and engage in unexpected military actions or

pursue military overexpansion beyond its capacity (Glaser 2010). The state's behaviors are driven by its

values, perceptions, and political ambitions as well as its rational calculations of costs and benefits.

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

16

Especially, national pride, historical memories, and territorial disputes can make states behave

emotionally. The possibility of a war between a democratic nation and a nondemocratic regime

increases because they do not share the same values and beliefs and, therefore, the level of mistrust

between them tends to be very high. China and the United States have enhanced their cooperation to

address various global issues like global warming, international terrorism, energy issues, and global

economic stability. But these issues are not strong enough to bring them together to overcome their

mistrust that stems from their different values, beliefs, and perceptions (Friedberg 2011). What is more

important is whether they can set mutually agreeable international rules on traditional security issues

including territorial disputes.

US-China entente is impossible—strategic competition is driven by bipolar balancing and ideological

divergence between two incompatible visions of the global order.

Friedberg 18—Aaron L. Friedberg, Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Princeton University,

PhD in Government from Harvard, deputy assistant for national-security affairs and director of policy

planning in the office of the Vice President from 2003-2005 (“Competing with China,” Survival: Global

Politics and Strategy, Vol. 60, No. 3, June-July 2018, pages 7-64, Taylor & Francis Online)

If there is a single theme that unifies much of what follows, it is the often underestimated importance of

political beliefs and ideology. America's post-Cold War strategy for dealing with China was rooted in

prevailing liberal ideas about the linkages between trade, economic growth and democracy, and a faith

in the presumed universality and irresistible power of the human desire for freedom. The strategy

pursued by China's leaders, on the other hand, was, and still is, motivated first and foremost by their

commitment to preserving the Chinese Communist Party's monopoly on domestic political power. The

CCP's use of militant nationalism, its cultivation of historic claims and grievances against foreign powers,

and its rejection of the idea that there are, in fact, universal human values are essential pieces of its

programme for mobilising popular support and bolstering regime legitimacy. It is impossible to make

sense of the ambitions, fears, strategy and tactics of China's present regime without reference to its

authoritarian, illiberal character and distinctive, Leninist roots.

The intensifying competition between the United States and China is thus driven not only by the

traditional dynamics of power politics – that is, by the narrowing gap between a preponderant hegemon

and a fast-rising challenger – but also by a wide and deep divergence in values between their respective

regimes. The resulting rivalry is more intense, the stakes are higher, and the likelihood of a lasting

entente is lower than would otherwise be the case. The two powers are separated not only by divergent

interests, some of which could conceivably be reconciled, but by incompatible visions for the future of

Asia and the world. China's current rulers may not be trying actively to spread their own unique blend of

repressive politics and semimarket economics, but as they have become richer and stronger they have

begun to act in ways that inspire and strengthen other authoritarian regimes, while potentially

weakening the institutions of young and developing democracies. Beijing is also using its new-found

clout to reach out into the world, including into the societies, economies and political systems of the

advanced industrial democracies, to try to influence the perceptions and policies of their people and

governments, and to suppress information and discourage the expression of opinions seen as

threatening to the CCP.

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

17

If they wish to respond effectively to these new realities, American and allied policymakers cannot

afford to downplay the ideological dimension in their own strategy. Beijing's obsessive desire to squelch

dissent, block the inward flow of unfavourable news and discredit ‘so-called universal values’ bespeaks

an insecurity that is, in itself, a form of strategic vulnerability. China's rulers clearly believe the

ideological realm to be a crucially important domain of competition, one that they would be only too

happy to see the United States and the other Western nations ignore or abandon.

Deterrence is key to co-existence --- try-or-die

Osnos 20 --- Evan Osnos, joined The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2008 and covers politics and foreign

affairs, Previously, Osnos worked as Beijing bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune, where he was part of a

team that won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize, “The Future of America’s Contest with China”, New Yorker, Jan

6th 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/01/13/the-future-of-americas-contest-withchina

The most dangerous frontier between Chinese and American power today is the contested terrain of the

Western Pacific: Taiwan, the South China Sea, and a series of shoals and islands that are unfamiliar to

the American public. In the South China Sea, the U.S. protests China’s claims by deploying warships and

jets close to the artificial islands, while Chinese vessels and planes try to scare them off, a game of

chicken that has produced, by the Pentagon’s count, at least eighteen unsafe encounters since 2016—

near-collisions at sea or in the air that could have killed troops. Adding to the risk, the U.S. and Chinese

militaries have abandoned some lines of communication, and failed to agree on sufficient rules of

conduct at sea, the kinds of measures that prevented minor incidents from escalating into catastrophe

during the Cold War.

Johnson, the former C.I.A. analyst, said the United States must make realistic decisions about where it is

prepared to deter China’s expansion and where it is not. “If we think we can maintain the same

dominance we have had since 1945, well, that train has left the station,” he told me. “We should start

by racking and stacking China’s global ambitions and determining what we can’t accommodate and what

we can, then communicate that to the Chinese at the highest levels, and operationalize them through

red lines we will enforce. We’re not doing that. Instead, what we’re doing are things that masquerade as

a strategy but, in fact, amount to just kicking them in the balls.”

By the end of 2019, nearly two years into the new era of confrontation, China and America were moving

steadily toward a separation that is less economic than political and psychological. Each side had

embraced a form of “fight fight, talk talk,” steeling for a “peace that is no peace,” as Orwell had it.

But Henry Kissinger considers America’s contest with China to be both less dire and more complex than

the Soviet struggle. “We were dealing with a bipolar world,” he told me. “Now we’re dealing with a

multipolar world. The components of an international system are so much more varied, and the lineups

are much more difficult to control.”

For that reason, Kissinger says, the more relevant and disturbing analogy is to the First World War. In

that view, the trade war is an ominous signal; economic polarization, of the kind that pitted Britain

against Germany before 1914, has often been a prelude to real war. “If it freezes into a permanent

conflict, and you have two big blocs confronting each other, then the danger of a pre-World War I

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

18

situation is huge,” Kissinger said. “Look at history: none of the leaders that started World War I would

have done so if they had known what the world would look like at the end. That is the situation we must

avoid.” Westad agrees. “The pre-1914 parallel is, of course, not just the growth in German power,” he

said. “What we, I think, need to focus on is what actually led to war. What led to war was the German

fear of being in a position where their power would not strengthen in the future, where they were, as

they put it in the summer of 1914, at the maximum moment.”

On each side, the greatest risk is blindness born of ignorance, hubris, or ideology. If the Trump

Administration were to gamble on national security the way that Navarro did with his botched

predictions on trade, the consequences would be grave; if Xi embraces a caricature of America

determined to exclude China from prosperity, he could misperceive this as his “maximum moment.”

The most viable path ahead is an uneasy coexistence, founded on a mutual desire to “struggle but not

smash” the relationship. Coexistence is neither decoupling nor appeasement; it requires, above all,

deterrence and candor—a constant reckoning with what kind of change America will, and will not,

accept. Success hinges not on abstract historical momentum but on hard, specific day-to-day decisions—

what the political scientist Richard Rosecrance, in his study of the First World War, called the “tyranny of

small things.”

To avoid catastrophe, both sides will have to accept truths that so far they have not: China must

acknowledge the outrage caused by its overreaching bids for control, and America must adjust to

China’s presence, without selling honor for profit. The ascendant view in Washington holds that the

competition is us-or-them; in fact, the reality of this century will be us-and-them. It is naïve to imagine

wrestling China back to the past. The project, now, is to contest its moral vision of the future.

A2: Containment Fails

Perceptions of containment lead to moderation, not lash out.

Christensen 15 (Thomas, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs,

Professor of World Politics and director of the China and the World Program at Princeton. “Epilogue: The

China Challenge” in The China Challenge: Shaping the Choices of a Rising Power, 2015. W. W. Norton &

Co. ISBN 978-0-393-08113-8, pp. 292-293)

Although the United States should not feed Chinese fears about U.S. hostility, Chinese anxiety about a

U.S. containment effort could carry some benefits for the United States: the potential for future

encirclement may encourage Chinese strategists to be more accommodating. Under conditions in which

Chinese analysts believe in the possibility of containment, even the most pessimistic realpolitik thinkers

might join their more optimistic colleagues, in prescribing moderate policies. Chinese strategists

sometimes recognize that more coercive Chinese policies toward neighbors increase both the

willingness and the ability of Washington to encircle and constrain China. Just as many American experts

DebateUS!

Release 10-1-22

19

understand that any attempt by the United States to contain China’s rise now would likely weaken the

United States, many Chinese observers think bullying by Beijing will create a tighter and more expansive

set of U.S.-led security relationships in the region.

Deterrence SOLVES crises instability

Matthew Kroenig, an associate professor of government at Georgetown University and a senior fellow

of the Atlantic Council, served in the administration of George W. Bush. “The Logic of American Nuclear

Strategy” Ebook, 2018

Use ’em or lose ’em enjoys a certain superficial plausibility, but, upon closer inspection, there are two

fundamental reasons why the logic simply does not hold up. First, it ignores the fact that the superior