CPD

Page 60

Ankylosing spondylitis

multiple choice

questionnaire

CONTINUING

PROFESSIONAL

DEVELOPMENT

Page 61

Read Patience Fordjour’s

practice profile on

respiratory infection

Page 62

Guidelines on

how to write a

practice profile

Ankylosing spondylitis: diagnosis

and management

NS724 Bond D (2013) Ankylosing spondylitis: diagnosis and management.

Nursing Standard. 28, 16-18, 52-59. Date of submission: April 23 2013; date of acceptance: October 18 2013.

Aims and intended learning outcomes

Abstract

This article provides an overview of ankylosing spondylitis, including

signs and symptoms, diagnosis and management. The article focuses

on the difficulties and delays associated with diagnosing this chronic

inflammatory disease and developments in diagnostic criteria. Changes

in the management of patients with the disease are also discussed,

particularly in light of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy.

Author

Deborah Bond

Lead biologics specialist nurse, Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic

Diseases, Bath.

Correspondence to: Deborah.Bond@rnhrd.nhs.uk

Keywords

Ankylosing spondylitis, anti-TNF therapy, back and joint pain, diagnostic

criteria, inflammatory disease, long-term conditions

Review

All articles are subject to external double-blind peer review and checked

for plagiarism using automated software.

Online

Guidelines on writing for publication are available at

www.nursing-standard.co.uk. For related articles visit the archive and

search using the keywords above.

This article discusses the management of

patients with ankylosing spondylitis in the

context of modern therapy options. After

reading this article and completing the time out

activities you should be able to:

Describe ankylosing spondylitis, including

the signs and symptoms.

Explore the effect of ankylosing spondylitis

on patients’ lives.

Understand the diagnostic criteria

for ankylosing spondylitis and issues

surrounding delay in diagnosis.

Discuss the pharmacological and

non-pharmacological treatment of patients

with this long-term condition.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic

inflammatory disease primarily affecting

the spine and sacroiliac joints. It is the most

common of a group of diseases known as

spondyloarthritides, which are rheumatic

diseases with common clinical symptoms. The

disease is estimated to affect up to 1% of the

general population (Baraliakos et al 2011).

However, prevalence varies depending on race,

with 0.04-0.06% of non-Caucasians affected

by the disease compared with 0.1-1.4% of

Caucasians (Boonen and van der Heijde 2004).

Variation in prevalence is thought to occur

because of the presence of the human leucocyte

antigen (HLA)-B27 gene within different

populations. HLA-B27 is a protein on the

surface of white blood cells. The effect of the

gene is unclear (Bowness 2002), but over 90%

of people with ankylosing spondylitis have the

52Downloaded

decemberfrom

18 ::rcnpublishing.com

vol 28 no 16-18by

:: 2013

© NURSING

STANDARD

/ RCN

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014.

For personal

use only. No

other PUBLISHING

uses without permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

and social activities, and increasing the risk of

depression (National Ankylosing Spondylitis

Society (NASS) 2010a). Therefore, early disease

management is essential to prevent damage

and disability. In a survey of people with

ankylosing spondylitis, 72% of respondents

were in employment, however only 38% of

these individuals received advice or help on

coping with symptoms of the condition while at

work (NASS 2010b). Pain, fatigue and physical

limitations were identified as the main factors

affecting a person’s ability to work.

Symptoms

There are a variety of symptoms of ankylosing

spondylitis, and these include:

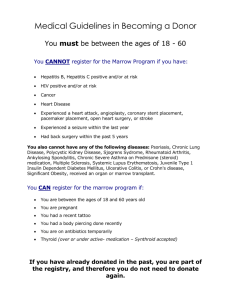

FIGURE 1

Ankylosed vertebrae (bamboo spine)

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

HLA-B27 gene, although only one in 15 people

who carry it will develop the disease (MiceliRichard and Dougados 2004). This suggests

that environmental factors such as stress might

also influence the development of the disease.

Ankylosing spondylitis is more common in

men than in women, although the reason for

this is unknown. However, estimates vary:

Gladman (2003) reported a 9:1 male to female

ratio of the disease, Rudwaleit et al (2004)

stated that it affects twice as many men as

women, and McKenna (2010) suggested a 5:1

male to female ratio of ankylosing spondylitis.

The onset of ankylosing spondylitis is

typically between 30 and 50 years, although

it can occur earlier (Gossec and Dougados

2004). Like all inflammatory diseases, there

are periods of flare and dormancy that make

it difficult to distinguish inflammatory back

pain from mechanical back pain (Table 1). As a

result, there may be a delay in diagnosis of up to

ten years (Khan 2003).

Ankylosing spondylitis causes pain and

stiffness in the back, eventually resulting in

joint damage and fusion predominantly of the

sacroiliac joints, and ankylosing of the vertebrae

leading to a classic bamboo spine (Figure 1),

although this does not always occur. It can affect

the rest of the axial skeleton (shoulders and

hips), leading to reduced range of motion and

pain. Some individuals develop joint destruction

and may require total joint replacement. This

can occur at a much earlier age than usual in

individuals with ankylosing spondylitis. The

disease can also cause peripheral symptoms

affecting the knees, hands and feet, which can

appear similar to rheumatoid arthritis, with

patients experiencing pain and swelling. This

can lead to misdiagnoses, thereby delaying

appropriate treatment (Khan 2003).

There are several extra-articular

(non-skeletal) features that may be associated

with ankylosing spondylitis, for example acute

anterior uveitis affects between 25% and 40% of

people with ankylosing spondylitis (Gossec and

Dougados 2004). Acute anterior uveitis or iritis,

characterised by inflammation of the iris, may be

the first indication that a person has ankylosing

spondylitis. This condition needs to be treated

as an emergency to prevent long-term problems

such as glaucoma or reduced vision (Khan 2003).

Cardiovascular manifestations such as valve

disorders and aortic incompetence may be more

common in those who are HLA-B27 positive and

can worsen with age (Bakland et al 2011).

Ankylosing spondylitis can have a significant

effect on patients’ lives, affecting work, family

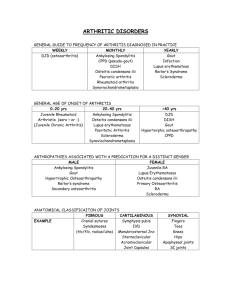

TABLE 1

Comparison of inflammatory and mechanical back pain

Inflammatory back pain

Mechanical back pain

Onset in those under 40 years.

Onset at any age.

Insidious onset.

More likely to be sudden onset.

Symptoms improve with exercise.

Symptoms often become worse with

exercise.

No improvement in symptoms

with rest.

Symptoms often improve with rest.

Pain at night, with improvement

on getting up.

Pain at night is less likely.

(Adapted from Sieper et al 2009a, Harris et al 2012)

© NURSING

/ RCNbyPUBLISHING

:: vol

nouses

16-18

:: 2013

53

Downloaded

fromSTANDARD

rcnpublishing.com

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014. For december

personal use18

only.

No28

other

without

permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

CPD inflammatory conditions

Early morning stiffness – can take from a few

minutes to many hours to ease, and it can

take up to two or more hours for a person

to get going in the morning. Sitting down

for any length of time can cause the spine to

stiffen up again (Khan 2003).

Pain – tends to develop gradually over weeks

or months rather than days, and occurs

mainly in the spine. Pain is worse at rest and

is eased by exercise (Sieper et al 2009a).

Enthesitis – is pain and swelling where

ligaments and tendons attach to bone.

A common site is the heel and pain on

walking can be significant, particularly in

the morning when the heel has been rested

overnight (Gossec and Dougados 2004).

Fatigue – constant exhaustion not relieved

by sleep (Mengshoel 2010).

Feverishness or night sweats – are commonly

reported symptoms in people with

ankylosing spondylitis. However, these

symptoms are also associated with other

inflammatory and autoimmune disorders

and there is a lack of evidence about the

cause of feverishness or night sweats (Mold

et al 2012).

Shortness of breath – as the disease

progresses it can cause fusion of the

thoracic vertebrae and also the attached

ribs, limiting expansion of the chest. If

the spine becomes fully ankylosed it can

lead to a stoop, which will also limit chest

expansion (Khan 2003).

Flares – individuals can go through periods

where ankylosing spondylitis is dormant

and then flares up. Cooksey et al (2009)

suggested that 70% of people with the

disease experience flares in any one week.

Complete time out activity 1

BOX 1

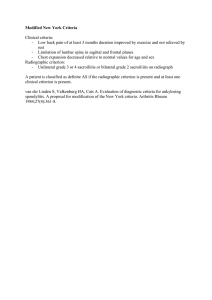

Modified New York criteria for diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis

Clinical criteria:

Low back pain for more than three months, which is improved by exercise

and not relieved by rest.

Limitation of lumbar spine motion in both the sagittal and frontal planes.

Limitation of chest expansion relative to normal values for age and sex.

Radiological criterion:

Sacroiliitis grade 2 or above. Grade 2 is bilateral sacroiliitis, grade 3-4 can

be unilateral or bilateral depending on the degree of fusion.

Diagnosis:

Definite ankylosing spondylitis if radiological criterion is present, including

at least one clinical criterion.

Probable ankylosing spondylitis if three clinical criteria are present, or if the

radiological criterion is present, but there are no clinical signs of disease.

(van der Linden et al 1984)

In individuals where ankylosing spondylitis

starts at a young age, there may be increased

comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease,

amyloidosis and infection, and complications

of a fused spine such as spinal fractures,

resulting in increased mortality (Bakland

et al 2011). According to Peters et al (2010),

the risk of myocardial infarction is almost

four times higher in people with the disease

compared with the general population – this

is similar to other inflammatory disorders.

It is, therefore, important that people

with the disease are monitored carefully

and that developing comorbidities such as

hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia are

managed appropriately.

Diagnosis

A better understanding of ankylosing

spondylitis and developments in diagnostic

techniques have led to changes in the diagnostic

criteria for the disease. Initially, ankylosing

spondylitis was thought to be a variation of

rheumatoid arthritis, however it was not until

the advent of diagnostic tests such as that for

the HLA-B27 gene that ankylosing spondylitis

was recognised as being different from

rheumatoid arthritis. The modified New York

criteria can be used to diagnose ankylosing

spondylitis (van der Linden et al 1984) (Box 1).

One of the difficulties associated with using

the modified New York criteria is that it can

take up to five years before there is radiological

evidence of sacroiliitis, by which time there

might be significant joint destruction. Use

of more advanced imaging technology such

as magnetic resonance imaging reduces the

time to diagnosis, with images showing

inflammatory changes years before bony

damage occurs. In 2009, the Assessment

of SpondyloArthritis International Society

(ASAS) published a consensus statement on

the classification of axial spondyloarthritis

(Rudwaleit et al 2009) (Figure 2).

Assessment

There is an internationally recognised set of

outcome measures for use with patients who

have ankylosing spondylitis known as the

Bath indices. These were designed to provide

comprehensive information relating to an

individual’s disease and the effect on his or her

life and health (Irons and Jeffries 2004). The

indices were devised in the 1990s and include

(Irons and Jeffries 2004):

54

decemberfrom

18 ::rcnpublishing.com

vol 28 no 16-18by:: ${individualUser.displayName}

2013

© NURSING

STANDARD

/ RCN

Downloaded

on Jun 22, 2014.

For personal

use only. No

other PUBLISHING

uses without permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity

index (BASDAI).

Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index

(BASFI).

Bath ankylosing spondylitis global score

(BAS-G).

Bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index

(BASMI).

The Bath indices are patient-reported outcome

measures and use visual analogue scales

(VASs). These scales are designed to gauge

an individual’s level of agreement with a

statement. Scores range from 0-10, with 0

being good and 10 being bad. The use of VASs

has limitations in that patients’ experiences,

perceptions and life issues can affect how

they perceive their disease and scores can be

influenced by other events that may act as

additional stressors. It is, therefore, possible

that the patient’s physical, objective score,

such as inflammatory markers and metrology,

indicate improvement, while subjective

measures, such as pain, may worsen (Kievit

et al 2010). The Bath indices, in particular

the BASDAI, are used as part of the screening

process to assess the patient’s suitability for

anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy

(Irons and Jeffries 2004).

Complete time out activity 2

Alternatives to the Bath indices have been

suggested, such as the ankylosing spondylitis

disease activity score (ASDAS) (Gossec and

Dougados 2004). This scoring system attempts

to make assessment a more objective process,

with the use of inflammatory markers such as

C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation

rate. However, it is important to note that as

many as 50% of individuals with ankylosing

spondylitis will not have raised inflammatory

markers, thereby reducing the reliability of the

ASDAS (Gossec and Dougados 2004).

Treatment

For many patients, ankylosing spondylitis

remains a mild disease that has minimal effects

on their activities of daily living and can be

self-managed.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Exercise Daily exercise might be helpful in the

treatment of ankylosing spondylitis, and should

include stretching and strengthening activities.

Dagfinrud et al (2008) found sufficient

evidence to support the conclusion that any

form of exercise is better than no exercise in

the management of ankylosing spondylitis, and

that supervised group therapy is preferable to

group physiotherapy alone.

Patients can access NHS run courses that

include education on various topics, including

exercise, treatments and self-management

of ankylosing spondylitis. These courses are

available on an inpatient or outpatient basis

and some run on a one-day-a-week basis, while

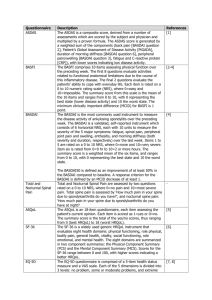

FIGURE 2

Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for axial

spondyloarthritis (in patients with chronic back pain and age at onset under 45 years)

Sacroiliitis on imaging plus one or

more axial spondyloarthritis feature

or

Sacroiliitis on imaging:

Active (acute) inflammation on magnetic

resonance imaging highly suggestive

of sacroiliitis associated with axial

spondyloarthritis.

Or:

Definite radiographic sacroiliitis according

to the modified New York criteria.

(Adapted from Rudwaleit et al 2009, Sieper et al 2009b)

Positive test for HLA-B27 gene plus two or

more other axial spondyloarthritis features

Axial spondyloarthritis features:

Inflammatory back pain.

Arthritis.

Enthesitis (heel).

Uveitis.

Dactylitis.

Psoriasis.

Crohn’s disease or diagnosis of colitis.

Good response to non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs.

Family history of axial spondyloarthritis.

Positive test for HLA-B27 gene.

Elevated C-reactive protein levels.

1 What effect might

the symptoms of

ankylosing spondylitis

have on a 21-year-old

man? How might these

symptoms affect this

person’s self-esteem

and confidence, and

what could you do to

help improve his quality

of life?

2 Read the personal

accounts of living with

ankylosing spondylitis

using the following NASS

web address: tinyurl.

com/mch48cp. Reflect

on what a diagnosis of

ankylosing spondylitis

might mean for patients

and their families. What

support might family

members require and

what resources could

you direct them to?

© NURSING

/ RCNbyPUBLISHING

:: vol

nouses

16-18

:: 2013

55

Downloaded

fromSTANDARD

rcnpublishing.com

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014. For december

personal use18

only.

No28

other

without

permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

CPD inflammatory conditions

others are an intensive two-week programme.

Education An understanding of ankylosing

spondylitis and the various aspects of

management is one of the most important

aspects of treatment. Patients who are engaged

with and participate in the management of

their disease are more likely to have better

outcomes than those who do not actively

participate in disease management (NASS

2012). Individuals’ understanding of the

disease and learning will vary, therefore

education should be tailored to the individual.

However, there is some basic information

that all patients will need to be given about

the disease, including signs and symptoms,

short and long-term effects, treatment options,

and general health issues such as smoking

reduction and cessation, weight management

and limiting alcohol intake. Individuals should

also be provided with information that they

can give to employers, schools and family

members (NASS 2010a).

Symptom control

If possible, management of ankylosing

spondylitis should involve the multidisciplinary

team. For many patients, pain, physical

limitations and fatigue are the main symptoms

that need to be addressed (Heiberg et al 2011).

Pain and physical limitations are managed

most effectively through a combination of

medication and exercise (NASS 2010a).

Physical limitations might also be addressed

with physiotherapy, occupational therapy

and medication.

Fatigue, although significant, is frequently

ignored by healthcare professionals (Davies

et al 2013, Hammoudeh et al 2013). Physical,

mental and activity-related fatigue, and loss

of motivation may be common in people with

ankylosing spondylitis (Missaoui and Revel

2006). Fatigue can also be associated with the

disease, drug treatment or other conditions

such as depression. It is not unique to

ankylosing spondylitis and is common in other

inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid

arthritis (Husted et al 2009, National

Rheumatoid Arthritis Society 2010).

There appears to be a link between fatigue

and factors such as pain, sleep and activity.

If sleep patterns can be improved, pain and

fatigue will also be improved (Mengshoel

2010). Mengshoel (2010) distinguished

between tiredness associated with daily life

such as work and sport, and fatigue associated

with illness. She described fatigue as an

unnatural whole body tiredness that leads to

feelings of exhaustion, helplessness and pain.

Pain at night is significant because it leads to

disturbed sleep. Lack of sleep affects function

and the individual’s ability to cope with fatigue

(Farren et al 2013). Hammoudeh et al (2013)

stated that pain at night occurs in 62-63%

of people with ankylosing spondylitis and

Mengshoel (2010) suggested that fatigue levels

increase about 24 hours after pain peaks. Advice

for patients should be centred on managing

factors that worsen fatigue as shown in Box 2.

There is some debate as to whether

medications lessen fatigue, particularly

in relation to the use of non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

(Dernis-Labous et al 2003). There is no

definitive answer to this and pharmacological

management of patients’ fatigue appears to

depend on individual response. There have

been more encouraging reports of fatigue

reduction with anti-TNF therapies, with

BOX 2

Advice for patients on managing factors that

worsen fatigue

Good sleep hygiene:

Avoid stimulants before bed.

Ensure hot baths are taken at least one hour

or more before bed to allow body temperature

to drop.

Ensure the bedroom is not too hot and

bedclothes are not too heavy. A good supportive

mattress may also be helpful to ensure comfort.

Diet and fluids:

Consume a healthy and balanced diet and remain

hydrated with non-alcoholic fluids.

Exercise:

Ensure exercise is regular, varied and manageable,

including exercises designed to improve muscle

strength, spinal flexibility and stability.

Pacing:

Understand and apply pacing to break activities

into small more manageable parts.

Plan ahead. If an individual knows he or she has

a busy day, the advice would be to take it easy

before and afterwards.

Identify activity patterns through the use of

diaries and activity records. This can help to

pace and plan activity.

Pain management:

Use non-pharmacological interventions, such

as exercise.

Use pharmacological interventions, such as

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and

anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy.

(National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society 2010)

56

decemberfrom

18 ::rcnpublishing.com

vol 28 no 16-18by:: 2013

© NURSING

STANDARD

/ RCN

Downloaded

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014.

For personal

use only. No

other PUBLISHING

uses without permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

positive responses to etanercept (Hammoudeh

et al 2013), golimumab (Deodhar et al 2010)

and adalimumab (Revicki et al 2008).

Complete time out activity 3

Pharmacological interventions

For the majority of patients, symptoms of

ankylosing spondylitis will be managed using

a variety of treatment options. At all times, the

prescriber needs to be aware of the risk and

benefit of particular drugs, as well as any other

comorbidities the individual may have. This

is especially important in people who have

long-term health conditions that may require

lifelong use of medications. This article focuses

on the use of pharmacological treatments

aimed at controlling disease activity; however,

many patients will require other treatments

such as analgesics, antidepressants, hypnotics

and antispasmodics.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs can be effective in reducing the pain

and inflammation associated with ankylosing

spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis (Escalas

et al 2010). Poddubnyy et al (2012) and Kroon

et al (2012) published evidence suggesting

that NSAIDs have a disease-modifying action

in ankylosing spondylitis and may limit the

development of ankylosis. NSAIDs should

be taken on a regular basis if the individual

is experiencing prolonged, active and

symptomatic disease (Braun et al 2011).

For most patients, the use of NSAIDs such as

naproxen or ibuprofen is preferable because they

are associated with a low risk of cardiovascular

problems (National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence (NICE) 2009). It is important

to be aware that there are safety risks associated

with NSAIDs and they should only be prescribed

when the patient’s full medical history is known.

These drugs should be avoided where there

is a history of cardiovascular, renal or gastric

problems. It is recommended that an appropriate

proton pump inhibitor is prescribed at the same

time as the NSAID especially when, as with

ankylosing spondylitis, patients may be receiving

treatment for many years (NICE 2009).

With regular use of NSAIDs, effectiveness can

diminish and many patients will have tried three

or more NSAIDs over the years to maintain a

reduction in pain and stiffness (Dougados et al

2002). NSAIDs in combination with analgesics

tend to be more effective than either treatment

alone (NICE 2009, Ong et al 2010).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs are

used regularly in rheumatology to treat a

number of inflammatory conditions, however

they seem to have little or no effect on patients

with axial ankylosing spondylitis (Zochling

et al 2006). Methotrexate or sulfasalazine

may be used in the treatment of patients with

peripheral problems such as pain and swelling

of the joints of the hands and feet (Zochling

et al 2006).

Biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic

drugs The development of biologic therapies

such as anti-TNF drugs have resulted in

advances in the treatment of ankylosing

spondylitis and the limitation of disease

progression potentially leading to reduced

disease activity. Evidence suggests that

anti-TNFs are the most effective of the

biologics in treating ankylosing spondylitis

(Zochling et al 2006).

Before an individual can be considered

for anti-TNF therapy, active disease as

defined by NICE (2008) must be established.

This includes a diagnosis of ankylosing

spondylitis using the modified New York

criteria, previous NSAID use, and appropriate

BASDAI and pain scores of 4 or above on the

VAS. The BASDAI and pain scores have to

be repeated three months apart in line with

NICE requirements.

The patient should undergo a thorough

assessment to identify actual and potential risk

factors before treatment. The Royal College

of Nursing (RCN) (2009) provides useful

information on assessing, managing and

monitoring biologic therapies for inflammatory

arthritis. Relevant investigations such as chest

X-ray also need to be completed.

Complete time out activity 4

Several biologic therapies are used in

rheumatology, including anti-TNF agents,

B cell depletors, interleukin-6 inhibitors

and T cell modulators. However, only

anti-TNF therapy appears to have an effect

in the management of ankylosing spondylitis

(Singh et al 2011). The main anti-TNF

therapies are adalimumab, etanercept,

golimumab and infliximab. Certolizumab

pegol is also awaiting licensing for this

indication. These therapies are grouped

according to their mode of action, which is

to block the action of a protein or eliminate

a cell. In this case, the purpose of these

therapies is to block the action of TNF

proteins. Soluble receptors (cepts) compete

with TNF-receptors to reduce the amount

of TNF attaching to cell receptors

(Abbas and Lichtman 2006).

Complete time out activity 5

3 Reflect on a

time when you were

extremely tired, perhaps

after a long shift. How

did it make you feel and

how did you cope with

it? How do you think you

would cope if you had

to deal with extreme

fatigue on a daily basis?

4 Read the RCN (2009)

document on assessing,

managing and monitoring

biologic therapies for

inflammatory arthritis.

Look, in particular, at

the section on screening.

Why is screening so

important? You may wish

to discuss your thoughts

with a colleague.

5 Access the most

recent copy of the British

National Formulary and

list some of the side

effects associated with

anti-TNF therapies.

© NURSING

/ RCNbyPUBLISHING

:: vol

nouses

16-18

:: 2013

57

Downloaded

fromSTANDARD

rcnpublishing.com

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014. For december

personal use18

only.

No28

other

without

permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

CPD inflammatory conditions

Monitoring

6 Consider the

implications for

individuals undergoing

long-term treatment

with immunosuppressant

therapies. How would

you help to prevent the

risk of infection. Provide

the rationale for your

suggestions.

7 Now that you have

completed the article,

you might like to write

a practice profile.

Guidelines to help you

are on page 62.

Once on a treatment regimen, patients

need to be monitored to ensure the safety

and effectiveness of any drugs. They should

be advised to have regular blood tests to

identify any adverse events that may occur

as a result of immunosuppression, such

as increased infections (Ding et al 2010).

There also needs to be evidence that the

treatment has reduced disease activity

as identified by NICE (2008). This means

that the BASDAI and pain scores have to

drop by 2cm or 50% from the original

VAS scores before treatment, and this has

to be reassessed every three months. If there

is any indication of initial non-response

or later failure, the scores should be

repeated six weeks later, and if there has

been no improvement the treatment should

be stopped.

Although NICE (2008) does not

recommend switching to an alternate

anti-TNF drug, there is some evidence to

show that individuals might respond to an

alternative anti-TNF because the drugs are

slightly structurally different from each other

(Lie et al 2011, Glintborg et al 2013).

Complete time out activity 6

Conclusion

Ankylosing spondylitis can cause severe pain,

fatigue and disability, thereby affecting all

aspects of an individual’s life. Identifying

the disease early is crucial to limit the physical

and psychological effects on patients.

Involvement of the multidisciplinary team and

local support groups can help the individual to

maintain a normal life with minimal disruption.

It has been shown that regular exercise can

reduce pain and maintain mobility. This,

combined with appropriate pain management,

can reduce the effect of fatigue and the incidence

of depression. NSAIDs and analgesics are

the mainstay of treatment for many people and

may limit disease progression. However, for

those with more advanced or debilitating disease,

newer biologics have been developed and are

associated with reduced pain and disability NS

Complete time out activity 7

References

Abbas AK, Lichtman AH (2006)

Basic Immunology Functions

and Disorders of the Immune

System. Second edition. Saunders

Philadelphia PA.

Bakland G, Gran JT, Nossent JC

(2011) Increased mortality in

ankylosing spondylitis is related

to disease activity. Annals of

the Rheumatic Diseases. 70, 11,

1921-1925.

Baraliakos X, Listing J, Fritz C et al

(2011) Persistent clinical efficacy

and safety of infliximab

in ankylosing spondylitis after

8 years-early clinical response

predicts long-term outcome.

Rheumatology. 50, 9, 1690-1699.

Boonen A, van der Heijde D (2004)

Epidemiology and socioeconomic

impact. In Dougados M,

van der Heijde D (Eds) Ankylosing

Spondylitis. Health Press, Oxford,

24-31.

Bowness P (2002) HLA B27 in

health and disease: a double-edged

sword? Rheumatology. 41, 8,

857-868.

Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X

et al (2011) 2010 update of the

ASAS/EULAR recommendations for

the management of ankylosing

spondylitis. Annals of the Rheumatic

Diseases. 70, 6, 896-904.

Cooksey R, Brophy S, Gravenor MB,

Brooks CJ, Burrows CL, Siebert S

(2009) Frequency and

characteristics of disease flares in

ankylosing spondylitis.

Rheumatology. 49, 5, 929-932.

Dagfinrud H, Kvien TK, Hagen KB

(2008) Physiotherapy interventions

for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews.

Issue 1, CD002822.

Davies H, Brophy S, Dennis M,

Cooksey R, Irvine E, Siebert S

(2013) Patient perspectives of

managing fatigue in ankylosing

spondylitis, and views on potential

interventions: a qualitative study.

BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders.

14, 163.

Deodhar A, Braun J, Inman RD

et al (2010) Golimumab reduces

sleep disturbance in patients with

active ankylosing spondylitis:

results from a randomized,

placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis

Care and Research. 62, 9, 1266-1271.

Dernis-Labous E, Messow M,

Dougados M (2003) Assessment

of fatigue in the management of

patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Rheumatology. 42, 12, 1523-1528.

Ding T, Ledingham J, Luqmani R

et al (2010) BSR and BHPR

rheumatoid arthritis guidelines on

safety of anti-TNF therapies.

Rheumatology. 49, 11, 2217-2219.

Dougados M, Dijkmans B, Khan M,

Maksymowych W, van der Linden SJ,

Brandt J (2002) Conventional

treatments for ankylosing

spondylitis. Annals of the Rheumatic

Diseases. 61, Suppl 3, iii40-iii50.

Escalas C, Trijau S, Dougados M

(2010) Evaluation of the treatment

effect of NSAIDs/TNF blockers

according to different domains in

ankylosing spondylitis: results of a

meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 49, 7,

1317-1325.

58

decemberfrom

18 ::rcnpublishing.com

vol 28 no 16-18by:: ${individualUser.displayName}

2013

© NURSING

STANDARD

/ RCN

Downloaded

on Jun 22, 2014.

For personal

use only. No

other PUBLISHING

uses without permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.

Farren W, Goodacre L, Stigant M

(2013) Fatigue in ankylosing

spondylitis: causes, consequences

and self-management.

Musculoskeletal Care. 11, 1, 39-50.

Gladman D (2003) Established

criteria for disease controlling drugs

in ankylosing spondylitis. Annals

of the Rheumatic Diseases. 62, 9,

793-794.

Glintborg B, Østergaard M,

Krogh NS et al (2013) Clinical

response, drug survival and

predictors thereof in 432 ankylosing

spondylitis patients after switching

tumour necrosis factor D inhibitor

therapy: results from the Danish

nationwide DANBIO registry. Annals

of the Rheumatic Diseases. 72, 7,

1149-1155.

Gossec L, Dougados M (2004)

Clinical features. In Dougados M,

van der Heijde D (Eds) Ankylosing

Spondylitis. Health Press, Oxford,

32-45.

Hammoudeh M, Zack DJ, Wenzhi L,

Stewart VM, Koenig AS (2013)

Associations between

inflammation, nocturnal back

pain and fatigue in ankylosing

spondylitis and improvements

with etanercept therapy. Journal

of International Medical Research.

41, 5, 1150-1159.

Harris C, Gurden S, Martindale J,

Jeffries C (2012) Differentiating

Inflammatory and Mechanical

Back Pain: Challenge Your Decision

Making. www.astretch.co.uk/

M208%20IBP%20Module%20

Booklet.pdf (Last accessed:

December 5 2013.)

Heiberg T, Lie E, van der Heijde D,

Kvien TK (2011) Sleep problems

are of higher priority for

improvement for patients with

ankylosing spondylitis than for

patients with other inflammatory

arthropathies. Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 70, 5, 872-873.

Husted JA, Tom BD, Schentag CT,

Farewell VT, Gladman DD (2009)

Clinical and epidemiological

research extended report:

occurrence and correlates of fatigue

in psoriatic arthritis. Annals of

the Rheumatic Diseases. 68, 10,

1553-1558.

Irons K, Jeffries C (2004) The

Bath Indices. Outcome Measures

for Use with Ankylosing Spondylitis

Patients. NASS, Surrey.

Khan MA (2003) Clinical features

of ankylosing spondylitis. In

Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen S,

Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH (Eds)

Rheumatology. Third edition.

Ankylosing Spondylitis Excerpta

Medica Publications, London,

1161-1181.

Kievit W, Hendrikx J,

Stalmeier PF, van de Laar MA,

Van Riel PL, Adang EM (2010)

The relationship between change

in subjective outcome and change

in disease: a potential paradox.

Quality of Life Research. 19, 7,

985-994.

Kroon F, Landewé R, Dougados M,

van der Heijde D (2012) Continuous

NSAID use reverts the effects of

inflammation on radiographic

progression in patients with

ankylosing spondylitis. Annals of

the Rheumatic Diseases. 71, 10,

1623-1629.

Lie E, van der Heijde D, Uhlig T

et al (2011) Effectiveness of

switching between TNF inhibitors

in ankylosing spondylitis: data

from the NOR-DMARD register.

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

70, 1, 157-163.

McKenna F (2010)

Spondyloarthritis. Arthritis

Research UK, Chesterfield.

Mengshoel AM (2010) Life

strain-related tiredness and

illness-related fatigue in

individuals with ankylosing

spondylitis. Arthritis Care and

Research. 62, 9, 1272-1277.

Miceli-Richard C, Dougados M

(2004) Genetic aspects. In

Dougados M, van der Heijde D (Eds)

Ankylosing Spondylitis. Health

Press, Oxford, 17-23.

Missaoui B, Revel M (2006)

Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis.

Annales de Readaptation

et de medicine Physique. 49, 6,

389-391.

Mold JW, Holtzclaw BJ,

McCarthy L (2012) Night sweats:

a systematic review of the

literature. Journal of the

American Board of Family

Medicine. 25, 6, 878-893.

National Ankylosing Spondylitis

Society (2010a) Looking Ahead.

Best Practice for the Care of People

with Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS).

NASS, Surrey.

National Ankylosing Spondylitis

Society (2010b) Working with

Ankylosing Spondylitis. NASS,

Surrey.

National Ankylosing Spondylitis

Society (2012) Ankylosing

Spondylitis (AS), Guidebook,

Answers and Practical Advice.

NASS, Surrey.

National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (2008)

Adalimumab, Etanercept and

Infliximab for Ankylosing

Spondylitis. Technical appraisal

No. 143. NICE, London.

National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (2009)

Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clinical

guideline No. 79. NICE, London.

National Rheumatoid Arthritis

Society (2010) Fatigue –

Beyond Tiredness. www.nras.

org.uk/includes/documents/

cm_docs/2010/f/fatigue_beyond_

tiredness_aug_10.pdf (Last

accessed: December 5 2013.)

Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P,

Merry AF (2010) Combining

paracetamol (acetaminophen)

with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory

drugs: a qualitative systematic

review of analgesic efficacy

for acute postoperative pain.

Anesthesia and Analgesia. 110, 4,

1170-1179.

Peters MJ, Visman I, Nielen MM

et al (2010) Ankylosing spondylitis:

a risk factor for myocardial

infarction? Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 69, 3,

579-581.

Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M,

Haibel H et al (2012) Effect of

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs on radiographic spinal

progression in patients with axial

spondyloarthritis: results from

the German Spondyloarthritis

Inception Cohort. Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 71, 10,

1616-1622.

Revicki DA, Luo MP,

Wordsworth P et al (2008)

Adalimumab reduces pain,

fatigue, and stiffness in patients

with ankylosing spondylitis:

results from the adalimumab

trial evaluating long-term

safety and efficacy for

ankylosing spondylitis (ATLAS).

Journal of Rheumaology. 35, 7,

1346-1353.

Royal College of Nursing (2009)

Assessing, Managing and

Monitoring Biologic Therapies for

Inflammatory Arthritis: Guidance

for Rheumatology Practitioners.

RCN, London.

Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J,

Braun J, Sieper J (2004) Prediction

of a major clinical response

(BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis

factor D blockers in ankylosing

spondylitis. Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 63, 6,

665-670.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D,

Landewé R et al (2009) The

development of Assessment

of SpondyloAarthritis

International Society

classification criteria for axial

spondyloarthritis (part II):

validation and final selection.

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

68, 6, 777-783.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D,

Landewé R et al (2009a) New

criteria for inflammatory back

pain in patients with chronic back

pain: a real patient exercise by

experts from the Assessment of

SpondyloArthritis International

Society (ASAS). Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 68, 6,

784-788.

Sieper J, Rudwaleit M,

Baraliakos X et al 2009b)

The assessment of

SpondyloArthritis International

Society (ASAS) Handbook: a guide

to assess spondyloarthritis. Annals

of the Rheumatic Diseases. 68,

Suppl 2, ii1-44.

Singh JA, Wells GA,

Christensen R et al (2011)

Adverse effects of biologics: a

network meta-analysis and

Cochrane overview. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews.

Issue 2, CD008794.

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA,

Cats A (1984) Evaluation of

diagnostic criteria for ankylosing

spondylitis. A proposal for

modification of the New York

criteria. Arthritis and Rheumatism.

27, 4, 361-368.

Zochling J, van der Heijde D,

Burgos-Vargas R et al (2006)

ASAS/EULAR recommendations

for the management of ankylosing

spondylitis. Annals of the

Rheumatic Diseases. 65, 4,

442-452.

© NURSING

/ RCNbyPUBLISHING

:: vol

nouses

16-18

:: 2013

59

Downloaded

fromSTANDARD

rcnpublishing.com

${individualUser.displayName} on Jun 22, 2014. For december

personal use18

only.

No28

other

without

permission.

Copyright © 2014 RCN Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved.