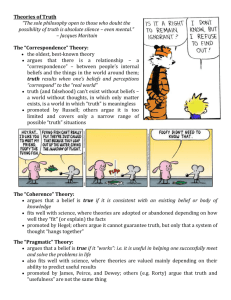

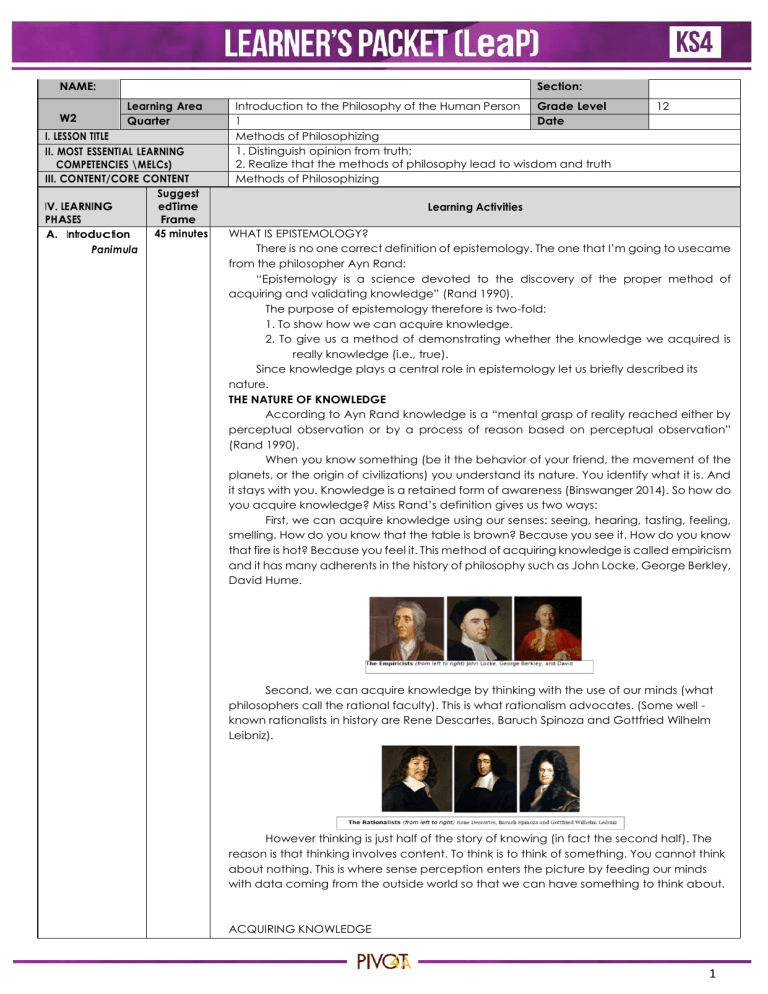

Section: NAME: W2 Learning Area Quarter I. LESSON TITLE II. MOST ESSENTIAL LEARNING COMPETENCIES \MELCs) III. CONTENT/CORE CONTENT Suggest IV. LEARNING edTime PHASES Frame 45 minutes A. Introduction Panimula Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Grade Level 1 Date Methods of Philosophizing 1. Distinguish opinion from truth; 2. Realize that the methods of philosophy lead to wisdom and truth Methods of Philosophizing 12 Learning Activities WHAT IS EPISTEMOLOGY? There is no one correct definition of epistemology. The one that I’m going to usecame from the philosopher Ayn Rand: “Epistemology is a science devoted to the discovery of the proper method of acquiring and validating knowledge” (Rand 1990). The purpose of epistemology therefore is two-fold: 1. To show how we can acquire knowledge. 2. To give us a method of demonstrating whether the knowledge we acquired is really knowledge (i.e., true). Since knowledge plays a central role in epistemology let us briefly described its nature. THE NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE According to Ayn Rand knowledge is a “mental grasp of reality reached either by perceptual observation or by a process of reason based on perceptual observation” (Rand 1990). When you know something (be it the behavior of your friend, the movement of the planets, or the origin of civilizations) you understand its nature. You identify what it is. And it stays with you. Knowledge is a retained form of awareness (Binswanger 2014). So how do you acquire knowledge? Miss Rand’s definition gives us two ways: First, we can acquire knowledge using our senses: seeing, hearing, tasting, feeling, smelling. How do you know that the table is brown? Because you see it. How do you know that fire is hot? Because you feel it. This method of acquiring knowledge is called empiricism and it has many adherents in the history of philosophy such as John Locke, George Berkley, David Hume. Second, we can acquire knowledge by thinking with the use of our minds (what philosophers call the rational faculty). This is what rationalism advocates. (Some well known rationalists in history are Rene Descartes, Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz). However thinking is just half of the story of knowing (in fact the second half). The reason is that thinking involves content. To think is to think of something. You cannot think about nothing. This is where sense perception enters the picture by feeding our minds with data coming from the outside world so that we can have something to think about. ACQUIRING KNOWLEDGE 1 Let us now explore the first part of epistemology: the process of acquiring knowledge. 1. Reality To know is to know something. This “something” is what philosophers call reality, existence, being. Let us employ the term existence. Existence is everything there is (another name for it is the Universe [Peikoff 1990]). It includes everything we perceive (animals, plants, human beings, inanimate objects) and everything inside our heads (e.g., our thoughts and emotions) which represents our inner world. Existence is really all there is to know. If nothing exists knowledge is impossible. 2. Perception Our first and only contact with reality is through our senses. Knowledge begins with perceptual knowledge. At first the senses give us knowledge of things or entities (what Aristotle calls primary substance): dog, cat, chair, table, man. Later we became aware not only of things but certain aspects of things like qualities (blue, hard, smooth), quantities (seven inches or six pounds), relationships (in front of, son of) even actions (jumping, running, flying). These so called Aristotelian categories cannot be separated from the entities that have it. Red for example cannot be separated from red objects; walking cannot be separated from the person that walks, etc. 3. Concept After we perceive things we began to notice that some of the things we perceive are similar to other things. For example we see three individuals let’s call them Juan, Pablo and Pedro who may have nothing in common at first glance. But when we compare them with another entity, a dog for example, suddenly their differences become insignificant. Their big difference to a dog highlights their similarity to one another (Binswanger 2014) We therefore grouped them into one class or group, named the group (“man” or “human being”) and define what that group is to give it identity (Peikoff 1990). We now have a concept which according to one dictionary means “an abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary) The first concepts we formed are concepts of things like dog, cat, man, house, car. These elementary concepts are called first level concepts (Rand 1990). From these first level concepts we can form higher level concepts through a process which Rand calls “abstraction from abstractions” (Rand1990). Let us describe the two types of abstraction from abstractions: wider generalizations (or simply widenings) and subdivisions (or narrowings) (Binswanger 2014): Wider generalization is the process of forming wider and wider concepts. For example from Juan, Pedro and Pablo we can form the concept “man”. Then from man, dog, cat, monkey we can form a higher and wider concept “animal”. And from plant and animal we can form a still higher and wider concept “living organism”. As we go up to these progressive widenings our knowledge increases. Subdivisions consist of identifying finer and finer distinctions. For example “man” is a first level concept that we can subdivide according to profession (doctor, entertainer, fireman, teacher), or race (Asian, Caucasian [white], black), or gender (man, woman, lesbian, gay), or nationality (Filipino, Chinese, American) among other things. As we go down these progressive narrowings our knowledge of things subsumed under a concept increases. The result of this progressive widenings and narrowings is a hierarchy (or levels) of concepts whose based is sense perception. As we move further from the perceptual base knowledge becomes more abstract and as we move closer to the perceptual level knowledge becomes more concrete. 4. Proposition When we use concepts in order to classify or describe an “existent” (a particular that exist be it an object, a person, an action or event, etc) (Rand 1990) we use what philosophers call a proposition (Binswanger 2014). A proposition is a statement that expresses either an assertion or a denial (Copi, 2002) that an existent belongs to a class or possess certain attribute. Proposition is usually expressed in a declarative sentence. When I say, for 2 example, that “Men are mortals” I am making an assertion of men which are affirmative in nature (thus the statement is an affirmative proposition). When I make an opposite claim however, “Men are not mortals” I am denying something about men and thus my statement is negative in nature (thus the proposition is called a negative proposition) An affirmative proposition therefore has the following structure: “S is P” (where S is the subject, P is the predicate and “is” is the copula stating the logical relationship of S and P) while the negative proposition has the structure “S is not P” (“is not” is the copula expressing denial). Notice that statements like “Men are mortals”, “Angels are not demons”, and “Saints are not sinners” can either be true or false. “Truth and falsity are called the two possible truth values of the statement” (Hurley 2011). (Later were going to explore the nature of truth). 5. Inference How do we demonstrate that the statement is true? By providing an argument. According to Hurley an argument “is a group of statements, one or more of which (the premises) are claimed to provide support for, or reason to believe one of the others (the conclusion) (Hurley 2011). To clarify this definition let’s give an example using the famous Socratic argument: All men are mortals Socrates is a man. Therefore Socrates is mortal. Here we have three related statements (or propositions). The last statement beginning with the word “therefore” is what we call a conclusion. A conclusion is a statement that we want to prove. The first two statements are what we call premises (singular form: premise). A premise provides justification, evidence, and proof to the conclusion. An argument expresses a reasoning process which logicians call inference (Hurley 2011). Arguments however is not the only form of inference but logicians usually used “argument” and “inference” interchangeably. There are still many things to be discuss on the topic of knowledge acquisition. We only provided a brief overview of the topic. THE NATURE OF TRUTH Now that we know how we know, it’s time to see whether the knowledge we acquired is “really” knowledge i.e., is true. This is the second part of epistemology: validating one’s knowledge. The first step in validating one’s knowledge is to ask oneself the following question: “How did I arrive at this belief, by what steps?” (Binswanger 2014). Thus you have to retrace the steps you took to acquire the knowledge, “reverse engineer” the process (Binswanger 2014). This is what Dr. Peikoff calls reduction (Peikoff 1990). One will therefore realize that the steps you took to acquire knowledge (perception-concept-propositioninference) are the same steps needed to validate knowledge (but in reverse order). Thus what the ancient pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus said is true when applied to epistemology: “the way up [knowledge acquisition] is the way down [knowledge validation]” (quoted by Dr. Binswanger 2014). If we perform the process of reduction we will realized that all true knowledge rest ultimately on sense perception. “A belief is true if it can be justified or proven through the use of one’s senses” (Abella 2016). Consider the following statements (Abella 2016): I am alive. I have a body. I can breathe. You can only validate the above statements if you observed yourself using your senses. Feel your body. Are you breathing? Feel your pulse. Observe your body. Is it moving? These and countless examples provided by your senses proved that you’re alive (Abella 2016). Not all statements however can be validated directly by the senses. Some beliefs 3 or ideas need a “multi-step process of validation called proof’ (Binswanger 2014). Nevertheless proof rests ultimately on sense perception. Statements based on sense perception are factual and if we based our beliefs on such facts our beliefs are true (Abella 2016). For example the belief that human beings have the right to life rests on the following claim: 1. Human beings are rational animals. 2. Animals (including human beings) are living organisms. And of course the fact that we are alive can be demonstrated perceptually as shown above. A third way to determine if the statement is true is through a consensus (Abella 2016). If the majority agrees that a statement is true then it is true. However there are certain limitations to this approach. Far too many times in history false ideas became popular which ultimately leads to disaster. For example the vast majority of Germans during the time of Adolph Hitler believed that Jews are racially inferior. This is obviously false supported by a pseudo biological science of the Nazi. The result of this false consensus is the extermination of millions of Jews in many parts of Europe. A fourth way to determine whether a statement is true is to test it by means of action (Abella 2016). For example you want to know if a person is friendly. Well the best way to find out is to approach the person. Thus the famous Nike injunction of “Just do it” is applicable in this situation. TRUTH VS OPINION Identifying truth however can sometimes be tricky. The reason is that there are times when we strongly held an idea that we feel “deep down” to be true. For example religious people strongly believed that there is life after death. Some people who embraced democracy may passionately embraced the idea that the majority is always right. Or on a more personal level you may feel strongly that your sister is “selfish”. However we must not confused strongly held beliefs with truth. Truth is knowledge validated and when we say validated we mean they are based on the facts of reality. You must understand dear student that the facts of reality are independent of your thoughts, feelings or preferences (Ayn Rand calls this the primacy of existence [Rand 1982]). That is the characteristic of truth. For example the statement “Jose Rizal died in 1896” is true. You may not like that statement or deny it strongly. That does not change the fact that the statement is true because it is based on what really happened in the past. There are many sources that can validate the truth of that statement if one cared to look. However when you say that “Jose Rizal is the greatest man who ever lived” you are stating your preference and not facts. This is an opinion. Now it is true that there are many facts about Rizal but that statement is asserting something that is beyond what the facts state. That statement represents not facts but your interpretation of facts which may reveal your biases. To summarize an opinion has the following characteristics: 1. Based on emotions 2. Open to interpretation 3. Cannot be confirmed 4. Inherently biased While truth is: 1. Based on the facts of reality 2. Can be confirmed with other sources 3. Independent of one’s interpretation, preferences and biases In knowing the truth or falsity of a statement, we generally use the following Theories 4 of Truth: 1. The Correspondence theory of Truth: The basic idea of the correspondence theory is that what we believe or say is true if it corresponds to the way things actually are based on the facts. It argues that an idea that correspond with reality is true while an idea, which does not correspond to reality is false. For example, if I say, “The sky is blue” then I looked outside and saw that it is indeed blue, then my statement is true. On the other hand, if I say, “Pigs have wings” and then I checked a pig and it does not have wings, then my statement is false. In general, statements of beliefs, propositions, and ideas are capable being true or false. However, according the Eubulides, a student of the Megara school of philosophy, “the correspondence theory of truth leaves us in the lurch when we are confronted with statements such as “I am lying” or “What I am saying here is false.” These are statements and therefore, are capable of being true or false. But if they are true because they correspond with reality, then any preceding statement or proposition must be false. Conversely, if these statements are false because they do not agree with reality, then any preceding statement or proposition must be true. Thus, no matter what we say about the truth or falsehood of these statements, we immediately contradict ourselves.” This does not mean that the Correspondence Theory of Truth is wrong or useless and, to be perfectly honest, it is difficult to give up such an intuitively obvious idea that truth must match reality. Nevertheless, the above criticisms should indicate that it probably is not a comprehensive explanation of the nature of truth. Arguably, it is a fair description of what truth should be, but it may not be an adequate description of how truth actually “works” in human minds and social situations (Cline, 2007). Austin Cline argues, it is important to note here that “truth” is not a property of “facts.” This may seem odd at first, but a distinction must be made between facts and beliefs. A fact is some set of circumstances in the world while a belief is an opinion about what those facts are. A fact cannot be either true or false because it simply the way the world is. A belief, however, is capable of being true or false because it may or may not accurately describe the world. 2. The Coherence Theory of Truth: It has already been established that the Correspondence Theory assumes that a belief is true when we are able to confirm it with reality. In other words, by simply checking if the statement or belief agrees with the way things really are, we can know the truth. However, as Austin Cline argues, this manner of determining the truth is rather odd and simplistic. Cline said that a belief can be an inaccurate description of reality that may also fit in with a larger, complex system of further inaccurate descriptions of reality. Thus, by relying on the Correspondence Theory, that inaccurate belief will still be called “truth” even though it does not actually describe actual state of things. So how do we resolve this problem? In order to know the truth of a statement, it must be tested as part of a larger set of ideas. Statements cannot be sufficiently evaluated in isolation. For example, if you pick up a ball and drop it accidentally, the action cannot be simply explained by our belief in the law of gravity which can be verified but also by a host of other factors that may have something to do with the incident, such as the accuracy of our visual perception. For Cline, only when statements are tested as part of a larger system of complex ideas, then one might conclude that the statement is “true”. By testing this set of complex ideas against reality, then one can ascertain whether the statement is “true” or “false”. Consequently, by using this method, we establish that the statement “coheres” with the larger system. In a sense, the Coherence Theory is similar to the Correspondence Theory since both evaluates statements based on their agreement with reality. The difference lies in the method where the former involves a larger system while the latter relies on a single evidence of fact. As a result, Coherence Theories have often been rejected for lacking justification in their application to other areas of truth, especially in statements or claims about the natural world, empirical data in general, and assertions about practical matters of psychology and society, especially when they are used without support from the other 5 major theories of truth. Coherence theories represent the ideas of rationalist philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and the British philosopher F.H Bradley. Moreover, this method had its resurgence in the ideas of several proponents of logical positivism, notably Otto Neurath and Carl Hempel. 3. The Pragmatist Theory of Truth: The Pragramatic Theory of Truth states that a belief/statement is true if it has a useful (pragmatic) application in the world. If it does not, then it is not true. In addition, we can know whether a belief/statement is true by examining the consequence of holding or accepting the statement/belief to be true. For example, there are some people who think that there are “ghosts” or “vampires” because they find it useful in explaining unusual phenomena and in dealing with fears (Mabaquiao, 2016). So, if we are going to use the word “truth”, we define it as that which is most useful to us. However, there are objections against this theory of truth. For Austin Cline, truth that is based on what works is very ambiguous. What happens when a belief works in one sense but fails in another? Suppose a belief that one will succeed may give a person the psychological strength needed to accomplish a great deal but in the end he fails in his ultimate goal. Was his belief “true”? In this sense, Cline argues that when a belief works, it is more appropriate to call it useful rather than “true”. A belief that is useful is not necessarily true and in normal conversations, people do not typically use the word “true” to mean “useful”. To illustrate, the statement “It is useful to believe that my spouse is faithful” does not at all mean the same as “It is true that my spouse is faithful.” Granted that true beliefs are also usually the ones that are useful, but it is not usually the case. As Nietzsche argued, sometimes untruth may be more useful than truth. B. Development Pagpapaunlad 45 minutes Activity: Inquire and Discover Read the passage from “Plato’s Allegory of the Cave” “Some prisoners are chained inside a cave, facing the back wall. Behind them is a fire, with people passing in front of it. The prisoners cannot turn their heads, and have always been chained this way. All they can see and hear are shadows passing back and forth and the echoes bouncing off the wall in front of them. One day, a prisoner is freed, and dragged outside the cave. He is blinded by the light, confused, and resists being led outside. But, eventually his eyes adjusts so that he able to see clearly the things around him, and even the sun itself. He came to realize that the things he thought were real were merely shadows of real things, and that life outside of the cave is far better than his previous life in chains. He pities those still inside. He ventures back into the cave to share his discovery with the others— only to be ridiculed because he can hardly see (his eyes have trouble at first re-adjusting to the darkness). He tried to free the other prisoners but they violently resisted (the other prisoners refuse to be freed and led outside, and they even tried to kill him)”. (https://wmpeople.wm.edu/asset/index/cvance/allegory) 1. What does this story mean? ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. How does this passage from Plato help you turn your attention toward the right thing (i.e., truth, beauty, justice and goodness)? ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 C. Engagement Pakikipagpalihan D. Assimilation Paglalapat V. ASSESSMENT (Learning Activity Sheets for Enrichment, Remediation or Assessment to be given on Weeks 3 and 6) 60 minutes Activity: Theories of Truth (Critical Thinking) Direction: Identify the different theories of truth on the following statements. Write your answer on the space provided before the number. _________1. There is a water fountain in front of the Cultural Center of the Philippines. _________2. Bachelors are unmarried men. _________3. The sun will rise tomorrow. _________4. A dream board is necessary for dreams to come true. _________5. What is more important to me at this time is my family. _________6. A wooden table is a solid object. _________7. Ghost and vampires exist. _________8. 2+2=4 _________9. Cats are animals. _________10. The Sky is blue. 60 minutes Direction: Make a reflection paper on Truth. (RECLECTION NOTEBOOK) (Critical Thinking, Character, Creativity, Communication) Guide Question: What is truth? How you tell the truth to others? 15 minutes Direction: Select the keyword that best fits the statement in each item. Encircle your answer. 1. Beliefs and statements are true if they are consistent with actual state of affairs. A. correspondence B. coherence C. pragmatic D. deflationary 2. Beliefs that lead to the best "payoff", that are the best justification of our actions that promote success, are truths. A. pragmatic theory C. correspondence theory B. semantic theory D. coherence theory 3. Check the headline information fair, objective, and moderate A. It’s time to consider other means of cash aid distribution B. Other countries around the world have much better means in cash aid distribution C. Government vows to faster distribution of coronavirus aid D. We can also learn lesson from Vietnam how they distribute their cash aid 4. Statements are true on the degree to which it "hangs together" with all the other beliefs in a system of beliefs. A. pragmatic B. coherence C. deflationary D. correspondence 5. The five senses are useful tools to verify the truthfulness of propositions. A. coherence theory B. pragmatic theory C. correspondence theory D. semantic theory 6. Why do we need epistemology? A. To overcome poverty C. To become geniuses B. To acquire and validate knowledge D. To succeed in life 7. Knowledge is ultimately grounded on ______________. A. Emotions B. Convictions C. Beliefs D. Sense perception 8. Philosophers who believed that knowledge is based on sense perception. A. Idealists B. Rationalists C. Empiricists D. Nominalists 9. Identify which of the following statements is factual? 1. My brother arrived at 11 pm. 2. My brother always come home late because he is a good for nothing individual. 3. Man is a living organism. 4. Free trade simply promotes the selfish greed of businessmen. A. 1 and 4 B. 2 and 3 C. 1 and 3 D. 2 and 4 10. Identify which statements above are mere opinions. A. 1 and 3 B. 2 and 4 C. 2 and 3 D. 1 and 4 Prepared by: GABRELLE MARIE D. OGAYON Subject Teacher Checked by: ROLAND V. MAGSINO Head Teacher II Noted by: ERIC A. MOLINES Principal I 7