The only guide you need for LPIC 1 exam success . . .

You’re holding in your hands the most comprehensive and effective guide available for the Linux Professional

Institute Certification 1 exams. Veteran Linux administrators Jason and Angie Nash deliver incisive, crystal-clear

explanations of every topic covered, highlighting exam-critical concepts and offering hands-on tips that can help

you in your real-world IT career. Throughout, they provide pre-tests, exam-style assessment questions, scenario

problems, and computer-based lab exercises—everything you need to master the material and pass the exams.

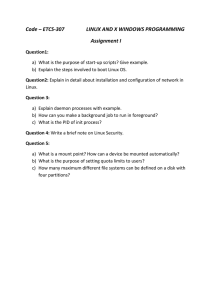

• Using the shell

• Installing software

• Processing text

• Managing network services

• Using shells and scripts

• Using documentation

• Using X

• Managing users and groups

• Installing Linux

• Working with the kernel

• Printing

• Networking fundamentals

• Managing security

Learn to set up

graphical window

managers

Labs include complete

installation instructions

for Red Hat and Debian

▲

• Administering the system

• Understanding the boot process • Managing files

• Using partitions and file systems

About the Authors

Test-Prep Material on CD-ROM

• Hungry Minds test engine powered by top-rated Boson Software

• Linux FAQs and HOWTOs for

exam preparation

• A searchable e-version of the book

Angie Nash is IT Consultant for her own firm, Tarheel Solutions.

She has her LPIC 1 certification and works primarily with Linux

and Microsoft operating systems to provide solutions for small

businesses.

Jason Nash is a LPIC 1–certified independent consultant experienced with Linux, Solaris, and several BSD variants. He has written

several books for the Microsoft world, but now spends most of his

time in Linux and BSD.

processor running at 90 MHz or faster; 20MB+

RAM; CD-ROM drive

$59.99 USA

$89.99 Canada

£44.99 UK incl. VAT

Reader Level:

Shelving Category:

Beginning to Advanced

Certification/Linux

ISBN 0-7645-4772-0

*85 5 -AFDH j

Covers LPI exams

101 and 102

COMPREHENSIVE

AUTHORITATIVE

WHAT YOU NEED

www.hungr yminds.com

,!7IA7G4-feh ca!:p;p;T;T;t

ONE HUNDRED PERCENT

—Tim Sosbe, Editorial Director, Certification Magazine

ONE HUNDRED PERCENT

NASH

NASH

Certification

Linux Professional Institute, www.lpi.org

System Requirements: PC with a Pentium

100%

C O M P R E H E N S I V E

LPIC1

Get complete coverage of the LPIC 1

exam objectives as you learn the ins

and outs of:

100%

“The ultimate reference guide to LPI Level 1 certification,

packed with useful tips and self-assessment features.”

Bible

Test-prep

material on

CD-ROM

Master the material

for Linux Professional

Institute exams 101

and 102

Test your knowledge

with assessment

questions, scenarios,

and labs

Practice on stateof-the-art testpreparation software

LPIC 1

Hungry Minds

Test Engine powered by

Angie Nash and Jason Nash

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page i

LPIC 1 Certification

Bible

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page ii

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page iii

LPIC 1 Certification

Bible

Angie Nash and Jason Nash

Best-Selling Books • Digital Downloads • e-Books • Answer Networks • e-Newsletters • Branded Web Sites • e-Learning

Indianapolis, IN ✦ Cleveland, OH ✦ New York, NY

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page iv

LPIC 1 Certification Bible

Published by

Hungry Minds, Inc.

909 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10022

www.hungryminds.com

Copyright 2001 Hungry Minds, Inc. All rights

reserved. No part of this book, including interior

design, cover design, and icons, may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the

prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2001090743

ISBN: 0-7645-4772-0

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1P/RY/QW/QR/IN

Distributed in the United States by Hungry Minds,

Inc.

Distributed by CDG Books Canada Inc. for Canada; by

Transworld Publishers Limited in the United

Kingdom; by IDG Norge Books for Norway; by IDG

Sweden Books for Sweden; by IDG Books Australia

Publishing Corporation Pty. Ltd. for Australia and

New Zealand; by TransQuest Publishers Pte Ltd. for

Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Hong

Kong; by Gotop Information Inc. for Taiwan; by ICG

Muse, Inc. for Japan; by Intersoft for South Africa; by

Eyrolles for France; by International Thomson

Publishing for Germany, Austria, and Switzerland; by

Distribuidora Cuspide for Argentina; by LR

International for Brazil; by Galileo Libros for Chile; by

Ediciones ZETA S.C.R. Ltda. for Peru; by WS

Computer Publishing Corporation, Inc., for the

Philippines; by Contemporanea de Ediciones for

Venezuela; by Express Computer Distributors for the

Caribbean and West Indies; by Micronesia Media

Distributor, Inc. for Micronesia; by Chips

Computadoras S.A. de C.V. for Mexico; by Editorial

Norma de Panama S.A. for Panama; by American

Bookshops for Finland.

For general information on Hungry Minds’ products

and services please contact our Customer Care

department within the U.S. at 800-762-2974, outside

the U.S. at 317-572-3993 or fax 317-572-4002.

For sales inquiries and reseller information, including

discounts, premium and bulk quantity sales, and

foreign-language translations, please contact our

Customer Care department at 800-434-3422, fax

317-572-4002 or write to Hungry Minds, Inc., Attn:

Customer Care Department, 10475 Crosspoint

Boulevard, Indianapolis, IN 46256.

For information on licensing foreign or domestic

rights, please contact our Sub-Rights Customer Care

department at 212-884-5000.

For information on using Hungry Minds’ products

and services in the classroom or for ordering

examination copies, please contact our Educational

Sales department at 800-434-2086 or fax 317-572-4005.

For press review copies, author interviews, or other

publicity information, please contact our Public

Relations department at 317-572-3168 or fax

317-572-4168.

For authorization to photocopy items for corporate,

personal, or educational use, please contact

Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive,

Danvers, MA 01923, or fax 978-750-4470.

LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: THE PUBLISHER AND AUTHOR HAVE USED THEIR

BEST EFFORTS IN PREPARING THIS BOOK. THE PUBLISHER AND AUTHOR MAKE NO

REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE

CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF

MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. THERE ARE NO WARRANTIES WHICH

EXTEND BEYOND THE DESCRIPTIONS CONTAINED IN THIS PARAGRAPH. NO WARRANTY MAY BE

CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES REPRESENTATIVES OR WRITTEN SALES MATERIALS. THE

ACCURACY AND COMPLETENESS OF THE INFORMATION PROVIDED HEREIN AND THE OPINIONS

STATED HEREIN ARE NOT GUARANTEED OR WARRANTED TO PRODUCE ANY PARTICULAR RESULTS,

AND THE ADVICE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR EVERY

INDIVIDUAL. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR ANY LOSS OF PROFIT OR

ANY OTHER COMMERCIAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL,

CONSEQUENTIAL, OR OTHER DAMAGES.

Linux Professional Institute and the LPI logo are trademarks of Linux Professional Institute, Inc. The Linux

Professional Institute does not endorse any third party exam preparation material or techniques. For further

details please contact info@lpi.org.

Trademarks: All trademarks are property of their respective owners. Hungry Minds, Inc. is not associated

with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

is a trademark of

Hungry Minds, Inc.

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page v

About the Authors

Angie Nash is an IT Consultant for her own firm, Tarheel Solutions. She works

primarily with Linux and Microsoft operating systems to provide solutions for small

businesses. Her free time is spent adding new products to her arsenal. She can be

reached at angie@the-nashes.net.

Jason Nash is an independent consultant experienced with Linux, Solaris, and several

BSD variants. He has written several books for the Microsoft world, but now spends

most of his time in Linux and BSD. He can be reached at jason@the-nashes.net.

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page vi

Credits

Acquisitions Editors

Nancy Maragioglio

Katie Feltman

Project Editors

Brian MacDonald

Kevin Kent

Technical Editor

Theresa Hadden-Martinez

Copy Editor

Kevin Kent

Editoral Managers

Ami Frank Sullivan

Kyle Looper

Project Coordinator

Emily Wichlinski

Graphics and Production Specialists

Gabriele McCann

Brian Torwelle

Quality Control Technicians

Andy Hollandbeck

Susan Moritz

Carl Pierce

Charles Spencer

Permissions Editor

Laura Moss

Media Development Specialist

Megan Decraene

Media Development Coordinator

Marisa Pearman

Proofreading and Indexing

TECHBOOKS Production Services

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page vii

This book is dedicated to two women who have made a profound impact on both our

lives. The unconditional love and support that we have received from Marie Ward and

Melva Hamby are always with us.

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page viii

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page ix

Preface

W

elcome to the LPIC 1 Certification Bible. This book is designed to help you

prepare for the Linux Professional Institute Certification Level 1 exams 101

and 102. The Linux Professional Institute is a distribution-independent, nonprofit

organization. The exams are developed to certify an individual’s expertise with

Linux systems. Level 1 certification is based upon many general tasks involving

Linux systems. This book provides all the information you need to perform these

tasks. Because of this, the book is useful as a study guide as well as a general Linux

reference. We believe that this book will prove to be a useful tool when preparing

for the LPIC exams and that you will want to keep it nearby as a handy resource

while working with Linux systems.

How This Book Is Organized

This book is organized into four major parts, followed by several appendixes, a

robust glossary, an index, and a compact disc.

Here’s what you’ll find in this book:

Part I: Installing Linux and Getting Started

Part I presents basic information about Linux. It covers the basic installation and

configuration of the Linux operating system. This part introduces the shell environment and its usage. Finally, this part covers software installation, including the

packaging systems used on Debian and Red Hat distributions.

Part II: Getting Around in Linux

Part II covers the basics of using Linux. This part explains many of the text processing tools available for Linux. Information on working with Linux partitions and file

systems is also covered in this section. Another task required to get around in

Linux is managing files and directories. This part introduces the commands most

often used for this task. The documentation resources available to aid with the

proper use of these commands and many of the tasks required on Linux are also

covered here. Part II also explores the boot process, detailing the use of various

configuration files and run levels. Finally, this part explores XFree86, the graphical

user interface available for Linux.

4772-0 FM.F

x

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page x

Preface

Part III: Administering Linux

Part III is all about administering and securing resources on a Linux computer. This

part begins by explaining how to manage users and groups. It also presents detailed

instructions on how to administer the system. This discussion covers a variety of

tasks such as system logging, making backups, and managing quotas. Additionally,

Part III explores the ins and outs of managing printing. This part also shows you

how to work with and even upgrade the kernel. Then Part III ends by building on

Part I, including more detailed information on shell usage.

Part IV: Managing the Network

Part IV covers the various concerns of a networked Linux computer. This part introduces the basics of TCP/IP protocols, files, and tools. Additionally, Part IV explains

how to create and configure network and dial-up connections. It also covers the

various server functions Linux can provide on a network. Finally, Part IV shows you

how to efficiently secure a Linux system.

At the end of the book are several valuable appendixes. You’ll find full practice

exams for both the 101 and 102 tests, a table of the actual exam objectives for both

LPIC exams (including cross-references to the section in this book where each

objective is covered), important information and tips on how to prepare for the

exams, and a complete listing and description of the contents of the compact disc

included with this book.

CD-ROM

This book includes a CD-ROM with several useful programs and utilities. First you’ll

find the Hungry Minds test engine, which is powered by Boson Software and features practice test questions to help you prepare for the exam. The disk also

includes an electronic version of the book in PDF format along with Adobe Acrobat

Reader so you can easily navigate this resource. Also included are several useful

Linux guides, FAQs, and HOWTOs, documentation that can help you grow in your

facility with and understanding of Linux systems.

How Each Chapter Is Structured

When this book was designed, a lot of thought went into its structure, particularly

into the specific elements that would provide you with the best possible learning

and exam preparation experience.

Here are the elements you’ll find in each chapter:

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xi

Preface

✦ A list of exam objectives (by exam) covered in that chapter

✦ A Chapter Pre-Test that enables you to assess your existing knowledge of

the topic

✦ Clear, concise text on each topic

✦ Step-by-step instructions on how to perform Linux tasks

✦ A Key Point Summary

✦ A comprehensive Study Guide that contains the following:

• Exam-style Assessment Questions

• Scenario problems for you to solve, as appropriate

• Lab Exercises to perform on your computer, as appropriate

• Answers to Chapter Pre-Test questions, Assessment Questions, and

Scenarios

How to Use This Book

This book can be used either by individuals working independently or by groups in

a formal classroom setting.

For best results, we recommend the following plan of attack as you use this book.

First, take the Chapter Pre-Test and then read the chapter and the Key Point

Summary. Use this summary to see if you’ve really got the key concepts under your

belt. If you don’t, go back and reread the section(s) you’re not clear on. Then do all

of the Assessment Questions and Scenarios at the end of the chapter. Finally, do the

Lab Exercises. Remember that the important thing is to master the tasks that are

tested by the exams.

The chapters of this book have been designed to be studied sequentially. In other

words, it would be best if you complete Chapter 1 before you proceed to Chapter 2.

A few chapters could probably stand alone, but all in all, we recommend a sequential

approach. The Lab Exercises have also been designed to be completed in a sequential order and often depend on the successful completion of the previous labs.

After you’ve completed your study of the chapters and reviewed the Assessment

Questions and Lab Exercises in the book, use the test engine on the compact disc

included with this book to get some experience answering practice questions. The

practice questions help you assess how much you’ve learned from your study and

also familiarize you with the type of exam questions you’ll face when you take the

real exams. Once you identify a weak area, you can restudy the corresponding

chapters to improve your knowledge and skills in that area.

xi

4772-0 FM.F

xii

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xii

Preface

Prerequisites

Although this book is a comprehensive study and exam preparation guide, it does

not start at ground zero. We assume you have the following knowledge and skills at

the outset:

✦ Basic terminology and basic skills to use Linux systems

✦ Basic software and hardware terms used with computers and networking

components

If you meet these prerequisites, you’re ready to begin this book.

How to determine what you should study

Your individual certification goals will ultimately determine which parts of this

book you should study. If you want to pass both LPIC exams or simply want to

develop a comprehensive working knowledge of Linux, we recommend you study

the entire book in sequential order.

If you are preparing only for the 101 exam, we suggest you follow the recommended

study plan shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Chapters to Study for Exam 101

Chapter Number

Chapter Title

2

Using the Shell

4

Processing Text

5

Using Partitions and File Systems

6

Managing Files

7

Using Documentation

8

Understanding the Boot Process

10

Managing Users and Groups

11

Administering the System

If you are preparing only for the 102 exam, we suggest you follow the recommended

study plan shown in Table 2.

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xiii

Preface

Table 2

Chapters to Study for Exam 102

Chapter Number

Chapter Title

1

Installing Linux

3

Installing Software

5

Using Partitions and File Systems

8

Understanding the Boot Process

9

Using X

12

Printing

13

Working with the Kernel

14

Using Shells and Scripts

15

Networking Fundamentals

16

Managing Network Services

17

Managing Security

Hardware and Software You Need

You need access to various hardware and software to be able to do the Lab

Exercises in this book. It’s extremely important that you do these labs to acquire

the skills tested by the LPIC Level 1 exams.

Caution

Some of the Lab Exercises in this book have the potential to erase or corrupt data

on existing hard disks. Make sure you back up all important data and programs

before you attempt to perform the labs. Better yet, do the labs on a computer that

doesn’t contain any vital data or programs.

Here are the minimum hardware requirements:

✦ Intel-based computer with Pentium/133MHz processor, 256MB of RAM, and

2GB of hard disk space.

✦ Keyboard

✦ CD-ROM drive

✦ Mouse or other pointing device

✦ VGA monitor and graphics card

✦ Network adapter card

xiii

4772-0 FM.F

xiv

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xiv

Preface

We strongly recommend that you use only hardware found on the Linux Hardware

Compatibility List. This list can be located on the Web sites of all Linux distributions such as http://www.redhat.com/support/hardware/ for Red Hat and

http://www.ibiblio.org/mdw/HOWTO/Hardware-HOWTO.html for Debian.

Optional equipment that you might benefit from using includes the following:

✦ Printer

✦ Tape drive

✦ Modem and Internet connection (so you can access online resources)

The software you need includes Linux Installation Software. This book covers both

Red Hat- and Debian-based distributions.

Conventions Used in This Book

Every book has its own set of conventions, so we’ll explain the ones we’ve used in

this book to you right up front.

New terms

How could we talk about Linux and other computer stuff without using all kinds of

fancy acronyms and terms, without using that alphabet soup you throw into everyday conversation around the dinner table that causes your family members to roll

their eyes?

We’ve chosen to italicize new or potentially unfamiliar terms, such as pwd, as we

define them. Normally, we define a new term right after its first mention. If you happen to see an unfamiliar word that is italicized, such as pwd, but is not followed by

a definition, you can flip to the glossary to read the definition of the term.

Code

All code listings and commands in this book are presented in monospace font, like

this:

# ls -al

We’ve also used this type of font to identify names of files, folders, Web addresses,

and character-based screen content when presented verbatim.

When you see monospace font presented in italics, the italicized text represents a

variable that could actually have a different name. This can be used to represent a

filename or perhaps a directory, like this:

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xv

Preface

ldd file_name

When you see monospace font presented in bold, the bold text represents text that

you would type, usually at the command prompt, like this:

[root@redhat jason]# ls /etc/pine*

Icons

Several different icons are used throughout this book to draw your attention to matters that deserve a closer look:

Caution

This icon is used to warn you that something unfortunate could happen if you’re

not careful. It also points out information that could save you a lot of grief. It’s

often easier to prevent a tragedy than it is to fix it afterwards.

CrossReference

This icon points you to another place in this book for more coverage of a particular topic. It may point you back to a previous chapter where important material has

already been covered, or it may point you ahead to let you know that a topic will

be covered in more detail later on.

Exam Tip

This icon points out important information or advice for those preparing to take

the LPIC exams.

In the

Real World

Sometimes things work differently in the real world than books — or product documentation — say they do. This icon draws your attention to the authors’ realworld experiences, which will hopefully help you on the job, if not on the LPIC

exams.

Objective

This icon appears at the beginning of certain parts of the chapter to alert you that

objective content is covered in this section. The text of the objective appears next

to this icon for your reference.

Tip

This icon is used to draw your attention to a little piece of friendly advice, a helpful

fact, a shortcut, or a bit of personal experience that might be of use to you.

How to Contact Us

We’ve done our very best to make sure the contents of this book are technically

accurate and error free. Our technical reviewer and editors have also worked hard

toward this goal.

However, we know that perfection isn’t a possibility in the real world, and if you

find an error, or have some other comment or insight, we’d appreciate hearing from

you. You can contact us via the Internet at angie@the-nashes.net and

jason@the-nashes.net.

xv

4772-0 FM.F

xvi

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xvi

Preface

We always read all of our readers’ e-mail messages and, when possible, include your

corrections and ideas in future printings. However, because of the high volume of

e-mail we receive, we can’t respond to every message. Please don’t take it personally if we don’t respond to your e-mail message.

Also, one last note: although we enjoy hearing from our readers, please don’t write

to us for product support or for help in solving a particular Linux problem you’re

experiencing on your computer or network. In this book we cover various places

available for locating support with these types of problems.

Well, that about wraps up the general comments. From here you can get started on

the nuts and bolts of learning about Linux and get ready to pass those exams. We

wish you great success!

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xvii

Acknowledgments

I

must first give my thanks to Nancy Maragioglio, Acquisitions Editor, Brian

MacDonald, Senior Project Editor, and Kevin Kent, Project and Copy Editor, for

this wonderful opportunity and all the work they have done to ensure that this

book reaches its full potential. This could not be done without all of their hard work

and dedication. The people at Hungry Minds have contributed to making this book

a positive experience, even amidst the frantic pace that seems to surround me.

I must acknowledge my husband and coauthor Jason, but words fail me. He is truly

my best friend and partner through all that life brings. I also have a wonderfully

supportive and loving family that has always made me feel special. My parents,

Martin and Kathy Brummitt, have selflessly sacrificed for my benefit. The debt I

owe them can never be repaid. I must also send my love and thanks to my siblings:

Jenny, Michael, and Chris; to Debbie, Jerry, Jeff, Steve, Renee, and Kim Hamby; and

to Nettie Cope and all the others in my family who have contributed to my life.

I must include a special thanks to Tim and Margaret Franks. You are wonderful people and deserve only the best life has to offer. I love you both. I also need to thank

my wonderful friends, Cathelene Shanaberger and Lisa Anderson. They have been

there for me whenever I have needed an ear or a shoulder. To all of my friends

online and through life, I could never fit everyone in this book. You know who you

are and so do I. Thank you.

— Angie Nash

Every acknowledgment you read, if you take the time to do so, starts with the

author thanking the publishing group they work with. I always figured that this was

a simple gratuitous action, but not anymore. The people at Hungry Minds are still

excellent to work with. On this project I would like to thank Nancy Maragioglio, our

Acquisitions Editor, Brian MacDonald, our Senior Project Editor, and Kevin Kent,

our Project and Copy Editor. Good people make projects like this go much

smoother, especially when deadlines seem to appear from nowhere.

At the top of my list is my wife Angie, who coauthored this book. She is by far the

most important thing in my life and my best friend, who I love very much. When

you look back in your life, it sometimes surprises you the influence that others had,

and without them you would not be where you are today. My mother and stepfather, Peggy and Tim Franks, and my grandmother Marie Ward have helped me more

than this entire book could hold. Special thanks are also due to my father Bill Nash,

my sister Jeanie, and my grandparents Homer and Frances Nash.

4772-0 FM.F

xviii

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xviii

Acknowledgments

This is the part I hear about long after the book is published. First, I’d like to say

thank you to some of my close friends: Jacob Hall, Robert Mowlds, Johnathan

Harris, Todd Shanaberger, and Lee Johnson. We have a large number of online

friends, and instead of listing them here and hearing about a couple we forgot,

we’ve just used their names in examples throughout the book. You know who you

are. Finally, I’d like to thank the members of the open source community that are

leading a revolution. Without them none of this would be possible.

— Jason Nash

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xix

Contents at a Glance

Preface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xvii

Part I: Installing Linux and Getting Started . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Chapter 1: Installing Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Chapter 2: Using the Shell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Chapter 3: Installing Software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Part II: Getting Around in Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157

Chapter 4: Processing Text . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter 5: Using Partitions and File Systems

Chapter 6: Managing Files . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter 7: Using Documentation . . . . . . .

Chapter 8: Understanding the Boot Process .

Chapter 9: Using X . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

159

201

231

275

295

331

Part III: Administering Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385

Chapter 10: Managing Users and Groups

Chapter 11: Administering the System .

Chapter 12: Printing . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter 13: Working with the Kernel . .

Chapter 14: Using Shells and Scripts . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

387

409

443

477

513

Part IV: Managing the Network . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 559

Chapter 15: Networking Fundamentals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 561

Chapter 16: Managing Network Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 599

Chapter 17: Managing Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 695

Appendix A: What’s on the CD-ROM

Appendix B: Practice Exams . . . . .

Appendix C: Objective Mapping . . .

Appendix D: Exam Tips . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

747

753

775

787

Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Index . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

End-User License Agreement . . .

CD-ROM Installation Instructions

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

791

803

845

848

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xx

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxi

Contents

Preface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ix

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . xvii

Part I: Installing Linux and Getting Started

1

Chapter 1: Installing Linux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

History of Linux and GNU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

The GNU General Public License . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

What Does Free Mean? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Why Use Linux? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Linux is multiuser . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Linux is multitasking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Linux is stable . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Linux has lots of available software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Linux has a wide range of supported hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Linux is fast . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Overview of the Linux Architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Kernel space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

User space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Linux Distributions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Red Hat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Mandrake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Debian . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

SuSE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Slackware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Caldera . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Turbolinux . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Preparing Hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

CPU requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Memory requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Hard disk controller requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Hard disk space requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Video requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

BIOS settings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Peripherals and other hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Resolving Conflicts and Configuring Plug-and-Play Hardware . . . . . . . . 18

Hardware addresses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Viewing configuration addresses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Configuring Plug-and-Play devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20

4772-0 FM.F

xxii

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxii

LPIC 1 Certification Bible

Partitioning Schemes . . . . .

Using fdisk . . . . . . . .

Using Disk Druid . . . . .

Using cfdisk . . . . . . . .

Boot Managers . . . . . . . . .

Installing Linux . . . . . . . . .

Red Hat installation . . .

Debian installation . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . .

Assessment Questions .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

21

23

25

26

28

28

28

41

59

61

61

61

61

62

Chapter 2: Using the Shell . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63

Understanding Shells . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using the Command Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Command completion . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Editing commands with the Readline Library

Command substitution . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using the history file . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

fc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Environment Variables and Settings . . . . . . . . .

Editing the PATH variable . . . . . . . . . . . .

The init process and the PATH variable . . . .

Prompt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

HOME . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Managing Processes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Modifying Process Priorities . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lab Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

65

67

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

76

76

77

77

82

85

89

89

90

90

90

92

Chapter 3: Installing Software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93

Installing Software from Source Code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95

Obtaining the source code . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96

Decompressing the tarball . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97

Running the configure script . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98

Making changes to the Makefile . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

Compiling the software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101

Installing the software . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxiii

Contents

Managing Shared Libraries . . . . . . .

Viewing required shared libraries

Setting library paths . . . . . . . .

Configuring shared libraries . . .

Red Hat Package Manager . . . . . . . .

Package files . . . . . . . . . . . .

The RPM database . . . . . . . . .

The rpm tool . . . . . . . . . . . .

Debian Package Management . . . . . .

Using dpkg . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using dselect . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using apt-get . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using alien . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lab Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Red Hat labs . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Debian labs . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . .

Scenario Answers . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Part II: Getting Around in Linux

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

103

104

104

104

105

106

107

107

118

119

127

132

137

141

144

145

145

147

153

153

153

155

157

Chapter 4: Processing Text . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 159

Working with Input and Output . . . . . .

Redirection . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pipes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

tee . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

xargs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Modifying Text with Filters . . . . . . . .

Sorting lines of a file . . . . . . . . .

Cutting text . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pasting text . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Converting tabs to spaces . . . . .

Formatting paragraphs . . . . . . .

Deleting or substituting characters

Viewing the beginning of a file . . .

Viewing the end of a file . . . . . . .

Joining multiple files . . . . . . . . .

Dividing files into multiple pieces .

Displaying files in other formats . .

Converting files for printing . . . .

Displaying files backwards . . . . .

Displaying numeric details of a file

Adding line numbers to a file . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

161

161

164

165

166

167

167

170

171

172

173

175

176

176

177

179

180

181

182

183

183

xxiii

4772-0 FM.F

xxiv

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxiv

LPIC 1 Certification Bible

Using the stream editor . . . . . . . . . .

Using grep . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Enhancing Searches with Regular Expressions

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lab Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

185

187

188

192

195

195

197

197

197

199

Chapter 5: Using Partitions and File Systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 201

Linux File Systems Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

File system types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Considerations when making a file system . . .

Creating Partitions and File Systems . . . . . . . . . .

Partition types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

File system tools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Checking the File System . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

fsck . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

du . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

df . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mounting and Unmounting File Systems . . . . . . . .

Mounting file systems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Unmounting file systems . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Checking available file systems with /etc/fstab

Checking mounted file systems with /etc/mtab

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lab Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

203

204

206

207

207

208

212

212

215

216

217

218

218

219

220

222

225

225

228

228

228

229

Chapter 6: Managing Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 231

Managing Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Changing directories . . . . . . .

Listing directory contents . . . .

Determining a file type . . . . . .

Changing file time stamp . . . .

Copying files . . . . . . . . . . .

Moving files . . . . . . . . . . . .

Deleting files . . . . . . . . . . .

Creating directories . . . . . . .

Understanding File System Hierarchy

Standard file locations . . . . . .

System directories . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

233

233

235

239

240

241

245

246

246

247

247

248

4772-0 FM.F

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxv

Contents

Locating Files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

find . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

locate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

which . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

whereis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Creating File Links . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Hard links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Symbolic links . . . . . . . . . . . .

Working with Permissions . . . . . . . . .

Symbolic and numeric permissions

Files, directories, and special files .

User and group permissions . . . .

SUID and SGID . . . . . . . . . . . .

Sticky bit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using Compression Tools . . . . . . . . .

tar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

gzip and gunzip . . . . . . . . . . . .

compress . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

bzip2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Managing Quotas . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

quota . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

edquota . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

repquota . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

quotaon and quotaoff . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

248

249

249

250

251

251

252

252

253

253

253

254

258

258

259

259

260

261

262

263

263

264

265

265

268

271

271

271

272

273

Chapter 7: Using Documentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 275

Getting Help with Man Pages . . . . . . .

Locating man pages . . . . . . . . .

Searching man page sections . . . .

Using Documentation Stored in /usr/doc

Documentation on the Internet . . . . . .

Linux Documentation Project . . . .

Vendor sites . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Newsgroups . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mailing lists . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Creating Documentation . . . . . . . . . .

Providing Technical Support . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . . . . . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

277

279

281

284

285

285

286

286

286

287

287

290

292

292

292

293

293

xxv

4772-0 FM.F

xxvi

5/14/01

4:20 PM

Page xxvi

LPIC 1 Certification Bible

Chapter 8: Understanding the Boot Process . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 295

Using LILO . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Configuring LILO . . . . . . .

Installing and updating LILO

Viewing boot messages . . .

Understanding Runlevels and init

Using runlevels . . . . . . . .

Configuring the init process

Customizing the Boot Process . .

BSD startup . . . . . . . . . .

Sys V startup . . . . . . . . .

Troubleshooting the Boot Process

Troubleshooting LILO . . . .

Booting to single-user mode

Creating a boot disk . . . . .

Creating repair disks . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lab Exercises . . . . . . . . . . . .

Answers to Chapter Questions . .

Chapter Pre-Test . . . . . . .

Assessment Questions . . . .

Scenarios . . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.