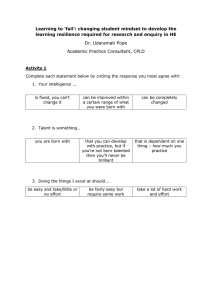

Introduction A person with a "global perspective" has the ability to influence individuals who think and act differently than themselves. The tactics deployed and the outcomes they produce today are extremely sensitive to how a multinational organization and its managers perceive and interpret the global and economic context in which they operate (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2002). From a cognitive standpoint, managers are considered information workers whose principal objectives are to acquire and share knowledge about prospective risks and benefits. Nonetheless, managers have their most considerable difficulty in overcoming the ambiguity and complexity of the information world. It is feasible to describe a "global mindset" as a collection of traits that enable individuals to learn, perform well in unfamiliar contexts, and achieve success. In order to adapt to the new and more complex global environment, corporate executives and managers will need to seek new ways to rethink continuously. To effectively manage globalization, global managers must articulate an implementable global strategy, encourage the creation of procedures that support this plan, and provide the conditions for this alignment to occur throughout the organization's strategy, process, culture, and structure. One definition of globalization is the phenomenon by which national boundaries lose significance, economic interdependencies intensify, and cultural differences among nations become a key concern for commercial organizations. In this essay, we will discuss THE Increasing demand exists for managers who can think globally and act locally. We suggest that a global perspective and technological skills must support a global perspective. Beginning with the inwardly oriented defender, managers might proceed to the exploratory, controlling, and integrating positions as their careers progress. Those in positions of global management responsibility must adopt the mentality of an integrator to succeed in their employment. For an organization to have a global perspective, its structure, procedures, people, and culture must evolve from a collection of independent departments into a coherent and efficient transnational network. Characteristics of Global Perspective A global mentality is more a state of mind than a collection of skills. It is a perspective that enables us to see things in the world that most people fail to see. A global perspective is the capacity to view the world holistically, scanning for emerging trends and opportunities that constitute a threat or present an opportunity to pursue professional, personal, or institutional objectives (Rhinesmith, 1993). Although a global mindset is a state of being essentially characterized by openness, and an ability to recognize complex interconnections, global managers need a certain set of supportive knowledge and skills to sustain the mindset. Knowledge and skills are needed to meet the changing, emerging, and increasingly complex conditions associated with globalization (Rhinesmith, 1993). provides an illustration of how global mindset, knowledge, and skills are interrelated. KNOWLEDGE • CULTURAL ISSUES PERSOECTIVE SKILLS • LEADERSHIP FOR MANAGING DIVERSITY GLOBAL MINDSET We argue that a global perspective is necessary but insufficient for global managers to navigate international competition successfully. Knowledge and skills are essential but insufficient for fostering and maintaining a global perspective. The success of management depends on their expertise in multiple disciplines. On the other hand, managers' skills are the intangible human and behavioral abilities that enable them to operate better in a cross-cultural situation. This global mentality, knowledge, and skills are sufficient for global managers. Knowledge for a Global Mindset The development of intellectual or behavioral abilities is not the primary objective of knowledge. Recognizing the importance of diversity is the basis of knowledge, and competence is the application of this knowledge. Their acquaintance with various pertinent issues might enhance the efficiency of a global manager. Mastering technology and applying it effectively within the perspective of a company's global operations is crucial. A second key piece of background information is understanding the sociopolitical aspects of other nations and how they affect corporate operations. Understanding the effects of cultural differences on management is the third field of competence. In addition to understanding the sociopolitical, economic, and cultural aspects of the global environment and other nations, global managers must also have technological knowledge. The knowledge required of global managers forms the basis of a global perspective and global attitude. The maxim "the more you learn, the more you want to learn" encapsulates the notion that a global manager's technical, business, and industry knowledge is an essential attribute that enables him or her to manage the competitive process locally and worldwide successfully (Rhinesmith, 1993). This comprehension must be broad and in-depth, with a strong emphasis on the global context, as demonstrated by behaviors such as the continual monitoring of information and globally competitive and market conditions. Knowledge requirements for global managers are the basic building blocks toward a global perspective, and a global mindset. Understanding cultural differences between nations and communities is essential for any global manager. Managers can only get to the next stage of open-mindedness, where they can begin to comprehend the myriad cultural factors and how they influence behavior if they are first made aware of culture's complexity. Skills for a Global Mindset Acquiring practical skills enables you to apply your knowledge. Managers may have a great deal of knowledge, for instance, about culture, but lack the complex abilities essential to put that knowledge to good use. Understanding the numerous cultural elements that influence behavior is the talent required here. Because intellectual activity may not immediately transform into a high skill level without substantial experience, one should act based on knowledge and comprehension (Lane et al., 1997). The only method that guarantees mastery of a subject is learning by doing. Any manager who operates on a global basis must be able to understand and adapt to diverse cultures. Leadership and utilizing diversity to benefit one's organization is another crucial skill. Learning to adapt to other cultures is one of the most difficult problems for global managers, as is learning to motivate and direct staff from diverse backgrounds. We live in a global, fast-paced world where adaptability and quickness are essential. The world in which managers live is filled with ambiguity and inconsistency. The former efficiency, hierarchy, and centralization paradigm is being replaced with one that encourages responsiveness, centralization, cooperation, and teamwork. Organizations must embrace a more organic structure to remain globally competitive and flexible to market shifts. To meet these objectives, it is critical to cultivate a global mentality and build robust process mechanisms. The challenge for global managers is interpreting the significance of cultural norms and determining how to leverage cultural differences in the workplace to increase productivity and production. American characteristics such as individualism, goal- and achievement orientation, competitiveness, and hostility must be adapted to the ideals of other cultures, which place a more considerable emphasis on collaborating to achieve common goals. Instead of attempting to change the cultural habits of others, global managers should consider how to utilize the many cultural viewpoints of their staff to achieve their goals. The inextricable link between language and culture can be highly advantageous for global managers. That is because the global manager's effectiveness is likely to increase if they communicate in a language their subordinates understand. MANAGERIAL MINDSETS The perspectives of management theorists have undergone significant changes over time. This section will outline some prevalent managerial ways of thinking and demonstrate how these distinct ways of thinking environmental impact studies and dictate managerial decisions. The following explanations and ideas were generated and developed with aid from Baird, although with significant modifications (1994). Less critical than tracing a straight progression through time is shedding attention on the variety of current worldviews and the effort required to switch between them. This presentation of four mindsets will demonstrate that some mindsets are less effective in today's intensified global competition and expanding economic interdependences since competitiveness, culture, and nation-states are intricately intertwined. The degree to which a person identifies with each of the four mindsets indicates the extent to which he or she has formed a worldwide viewpoint, consisting of a global mentality, knowledge, and abilities. Then, we categorize and characterize the four attitudes we have identified. Defender Explorer Controller Integrator. The Defender The defender's worldview rests around the notion that culturally or ethnically diverse individuals and groups offer a threat. The defender is aware of the existence of other individuals but has little regard for them. Despite having limited options to attract international clients due to a lack of marketing and distribution infrastructure, the defender makes no effort to reach out to or research international markets. Frequently, the defense is oblivious to the fact that the acts of international competitors directly impact the home market's trajectory. When confronted by foreign adversaries, the defense prefers hiding behind the protection of the domestic legal and political system rather than waging war. Rarely do the defendant's business ideas incorporate a global vision. The Explorer While the explorer, like the defender, prioritizes domestic issues, they are also aware of the possible financial benefits of expanding into other markets. The traveler is aware that there are people from various cultural origins all around the globe. Despite this, the explorer is not necessarily of the opinion that it is desirable to avoid or ignore non-native civilizations. Different local cultures may impede entry, but the explorer can still improve product reach and revenue by entering new markets. (Baird, 1994) The Controller If the controller is motivated by self-interest, it may adopt subsets of its particular mentality to accomplish its objectives. The controller may adopt a polycentric mentality, in which case its strategic decisions will be adapted to the norms of each country in which it operates; alternatively, it may adopt a polycentric mentality, in which case its interests will be combined with those of its subsidiaries on a more narrowly geographical scale (Chakravarthy & Perlmutter, 1985). However, when running a business and making important choices, the controller's perspective triumphs. Notably, the central controller office focuses on techniques for managing and, to a lesser extent, coordinating the numerous divisions and locations. The chosen concept holds that the parent company is supreme and that all critical decisions must be approved and sanctioned by corporate headquarters. The Integrator We claim that the integrator is the only type of manager who can truly work on a global scale, owing to their enlarged awareness (knowledge) and skill sets (skills). The integrator has a worldwide perspective and networks with organizations throughout the globe, including those that supply them, create their products, design their packaging, and distribute their goods (Baird, 1994). Managers play a vital role in facilitating the efficient movement of information and knowledge throughout the global system. Integrators construct data networks to regulate dependent relationships and maximize the benefits of diversity. Regarding competition, integrators recognize that the optimal strategy is a win-win (Brandenburger & Nalebuff, 1993), as opposed to the zero-sum game attitude that may characterize the perspectives of defenders, explorers, and controllers. Integration, coordination, and the management of change, as opposed to limitation and control, are more critical to the integrator than the establishment of stability. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION Given the quick rate of change, there is an urgent need for managers with a global perspective. A global perspective involves a particular way of thinking, a body of knowledge, and a set of skills. A manager from one region can readily work in another region if they have the knowledge and awareness that comes with a global mindset. When management adopts a global mindset, their competency and efficiency will grow. Managing and motivating a multicultural staff is crucial for any global manager. Global managers must both direct and coach their teams. Globally minded managers must educate themselves. A manager must be able to utilize cutting-edge technology effectively, as well as appreciate and evaluate the impact of technology on the company's global operations. We believe that globalization came prior to the ability of many managers to adapt to new and complex situations. As has been established, the worldviews of many top-level executives continue to be grossly out of sync with the realities of today's internationally competitive corporate environment. The issue arises in determining which mindsets managers hold and how they prevent them from realizing their full potential. Reference: Gupta, A., & Govindarajan, V. (2002). Cultivating a global mindset. Academy of Management Perspectives, 16, 116-126. Rhinesmith, S. H. (1993). A manager’s guide to globalization: Six keys to success in a changing world. New York, Irwin. Baird, L., Briscoe, J., Tuden, L., & Rosansky, L. M. H. (1994). World class executive development. Human Resource Planning, 17(1): 1–10. Brandenburger, A. M. & Nalebuff, B. J. (1993). The right game: Use game theory to shape strategy. Harvard Business Review, JulAug: 57–71. Chakravarthy, B. & Perlmutter, H. V. (1985). Strategic planning for a global economy. Columbia Journal of World Business, Summer: 3–10.