Bystanders' Reactions to Witnessing

Repetitive Abuse Experiences

Gregory R. Janson, JoLynn V Carney, Richard J. Hazier,

and Insoo Oh

Wmhe Impact of Event Scale—Revised (D. S. Weiss & C. R. Marmar, 1997) was used to obtain self-reported trauma levels

from 587 young adults recalling childhood or adolescence experiences as witnesses to common forms of repetitive

abuse defined as bullying. Mean participant scores were in a range suggesting potential need for clinical assessment

at the time these events occurred. Multiple regression analysis identified significant predictors of distress levels, with

intensity of abuse being the strongest. Additional results and implications of findings are discussed.

Concern over different forms of interpersonal violence in

schools remains an increasing concern for millions of students,

parents, educators, and communities not just in the United

States, but worldwide (Carney, Hazier, & Higgins, 2002; Cole,

Cornell, & Sheras, 2006; Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Smith,

Nika, & Papasideri, 2004). The literature has well established

that bullying is not the harmless, minor, developmentally

appropriate behavior of popular belief, but it is one that puts

many young people at considerable physical and psychological

risk (Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005; Rigby, 2002; Wolke,

Woods, Bloomfield, & Karstadt, 2001). The vast majority of

these studies on school bullying have focused on those who

bully and their direct victims, whereas few have explored the

impact of observing this form of repetitive abuse on the many

times greater number of young people who witness it (Hazier,

1996; Janson & Hazier, 2004).

Recent research (Janson & Hazier, 2004) suggests that

witnessing low-level repetitive abuse may aifect bystanders

and direct victims in similar physiological and psychological

ways that can stay with them for years to come. Bullying appears to have the potential to create levels of psychological

distress that approach, and in some cases exceed, the levels

reported for groups in the literature who have suffered traumatic experiences widely recognized as severe. These findings

lend support for the position of some researchers that the

effects of repetitive psychological abuse may be as damaging and enduring as the effects of physical abuse (Janson &

Hazier, 2004). Although this type of research on bystanders

to bullying, harassment, and other common forms of everyday abuse is still uncommon, studies of other forms of abuse

have demonstrated that differences in the impact on victim

and bystander are often blurred (Boney-McCoy & Finkelhor,

1995). Characteristic responses seen in victims and shared

by bystanders are physiological arousal (Hosch & Bothwell,

1990); repression of empathy (Gilligan, 1991); desensitiza-

tion to negative school behaviors (Safran & Safran, 1985);

dangerous, negative behaviors in general (Garbarino, 2001);

and feelings of isolation, hopelessness, and ineffectiveness

(Hazier, 1996). Recognition of the common risks shared by

bystanders and direct victims can be seen in the literature in

the use of alternate terms used to describe bystanders, such

as covictims (Shakoor & Chalmers, 1991) or indirect victims

(Morgan & Zedner, 1993).

Growing recognition of the potential harm to youthful

witnesses of repetitive abuse (Janson & Hazier, 2004) has

been accompanied by identification of their essential roles

in programs aimed at decreasing such abuse among youth

(Hazier & Carney, 2006). The fact that bystanders far outnumber the abusers and victims, who have been traditionally

perceived as the targets of research, makes it all the more

important that research be conducted on the situational and

personal factors that infiuence bystanders' reactions to youthful repetitive abuse.

•Situational Characteristics

The definition of bullying that has become standard in worldwide investigations into youthful repetitive abuse contains

three defining components: a negative action that harms

someone, an imbalance of power, and repetition over time

(Monks & Smith, 2006; Olweus, 1996). These situational

factors in combination appear to have a major influence on

the degree of harm done by repetitive abuse.

Type of harm has recently been a focus of discussion in

the literature (Carney & Hazier, 2001; Craig, Henderson, &

Murphy, 2000; Hazier, Miller, Carney, & Green, 2001), with

physical and emotional types getting much attention. Children

subjected to physical harm are the most easily identified and

generally get immediate attention because of visible signs

of injury that may be evident (e.g., blood, bruises, scratches.

Gregory R. Janson, Counseling and Psychological Services, Ohio University; JoLynn V. Carney, Rlchanl J. Hazier, and Insoo

Oh, all at Department of Counselor Education, Counseling Psychology, and Rehabilitation Services, The Pennsylvania State

University, University Park. Insoo Oh is now at the Department of Education, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Gregory R. Janson, Counseling and Psychological Services, Ohio

University, 345 Baker Center, Athens, OH 45701 (e-mail: gregory@ohlo.edu).

© 2009 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved.

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

319

Janson, Carney, Hazier, & Oh

ripped clothing). It is more challenging to identify children

who are hurt as the result of emotional harm, such as namecalling, verbal abuse, or social isolation (Rigby, 2002), Because the causative actions and the internal scars of this type

of abuse are emotional in nature, they are more difficult to

see and therefore generally receive less attention. The results

are significant feelings of humiliation, hopelessness, and

helplessness with corresponding fantasies of revenge and

suicidal thoughts (Carney, 2000; Hazier & Carney, 2000;

Rigby &Slee, 1999),

Bullying differs from the traditional physical or social

concept of a developmentally appropriate peer conflict because

abusers have an unfair advantage over their targets through

physical strength or size, verbal ability, or social sophistication. The bully's advantage maintains a power inequity that

leaves victims frustrated and expressing feelings of personal

inadequacy, \ov/ self-worth, and limited abilities to gain itifluence (Hazier & Carney, 2000),

The repetition aspect of bullying is a relationship component that convinces victims that their abusers are in total

control. The fact that the bully can repeat the abuse time and

again results in feelings of helplessness, with each incident

reinforcing the perception of being trapped in a hopeless

cycle of violence (Hazier, 1996; Hazier & Carney, 2000),

This repetitive exposure appears to exacerbate distress and

produces more problematic symptoms in children (Garbarino,

2001; Richters & Martinez, 1993),

•Personal Characteristics

A number of personal characteristics of witnesses and victims have been suggested as playing a part in the reactions of

witnesses to youthful repetitive abuse. Sex of the victim has

received considerable attention, whereas sex of the witness

has received considerably less. Females involved in repetitive

abuse have been more likely to be involved in those situations

related to emotional harm, termed relational bullying, than

have males (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Monks & Smith, 2006),

There is little information on how the sex of witnesses plays

into their reactions, although one study did support the idea

that women were more likely to say they would intervene in

bullying situations (Craig et al,, 2000),

Grades 5-8 have been consistently found to be the grades

in which bullying is most likely to take place (Nansel et al,,

2001), In this age range, and on a daily basis, youth must find

ways to deal with the changes of puberty combined with a

change in education format that increases both the number

of teachers and new students. Social, physical, and emotional

changes press students to reevaluate who they are in the

context of others, which leads to a time of unease and power

struggles that often takes the form of bullying, harassment,

and other kinds of repetitive abuse.

The physical characteristics of victims, their race, and

emotional or intellectual abilities have all been cited as factors

320

that can play a role in whether an individual will be targeted as

a victim (e,g., Hanish & Guerra, 2000; Hazier, Carney, Green,

Powell, & Jolly, 1997), Although it is clear that witnessing

repetitive abuse negatively affects bystanders, it is not well

understood how such personal factors influence current and

nature levels of trauma.

Previous research has established that bystanders to

traumatic events can be significantly affected by what they

observe, even when the level of abuse is low, but repeated over

time. It is therefore appropriate to more closely examine the

degree of impact such repetitive abuse might have on bystanders witnessing common forms of repetitive abuse as well as

situational and personal factors that might have an impact on

trauma. The core questions for this study are as follows:

1, To what degree do young adults who were witnesses

to low-level repetitive abuse at an earlier age recall

the level of trauma they experienced?

2, What factors commonly associated with witnessing

repetitive abuse experiences appear to influence how

trauma reactions are recalled by bystanders?

•Method

Participants

Open enrollment classes in a college of education and college

of health and human services were used to recruit 587 participants at a midsized state university (> 20,000) located in

the Midwest, Because some participants did not respond to

all questions on the survey, the data reported here may vary

slightlyfi-omone category to the next.

Participants were primarily traditional-age college students, with 566 (96,4%) who were ages 18 to 24 years; 559

(95,2%) students were single. Women (515, 87,7%) were the

majority participants. Of the educational levels spread across

class ranks, 206 (35.1%) were 1 st-year students, 146(24,9%)

were sophomores, 94 (16%) were juniors, 97 (16,5%) were

seniors, 13 (2,2%) were 5th-year students, and 14 (2,4%)

were students who reported their status as "other," Seventeen

participants (2,9%) did not indicate their educational level.

The sample included 514 (87,6%) European Americans,

13 (2,2%) African Americans, 9 (1,5%) Native Americans, 5

(,9%) Latino/Latina Americans, 3 (,5%) Asian Americans, 4

(,7%) biracial individuals, 9 (1,5%) in the "other" category,

and 30 (5,1%) who did not respond. Self-reported gross

family incomes identified 438 (74,6%) with family incomes

above $42,000 per year, 305 (52%) above $60,000, and only

40 (6,8%) below $30,000,

Procedure

The study was conducted in classroom settings where each

participant received a packet containing a cover sheet (describing the research, confidentiality, and risks) and three

paper-and-pencil instruments. The approach taken in this study

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

Bystanders' Reactions to Witnessing Repetitive Abuse

was to gather data in the least threatening, least emotionally

arousing method possible while also using reliable instrumentation to measure trauma. Participants were therefore asked to

silently recall how they felt at a time in their past when they

witnessed repetitive abuse of another individual and then to

complete the survey instruments.

Instruments

Three instruments were used to answer the research questions

and to understand the characteristics ofthe participants. The

Personal Information Survey was developed by the authors

ofthe current study to describe aggregate participant characteristics. The Repetitive Abuse Description Form was adapted

from a previous study (Janson & Hazier, 2004) to direct participants in the recall of being a bystander to abuse activity

during their K-12 school years and also to provide descriptive

information on the events they recalled. The Impact of Event

Scale—Revised (IES-R; Weiss & Marmar, 1997) evaluated

the degree of trauma participants recalled from their experience as witnesses to repetitive abuse experiences.

Repetitive Abuse Description Form. This form set the stage

for participants and collected information on issues surrounding the situation experienced by the bystander. Participants

were asked to consider situations they experienced during their

K—12 school career. Directions then began with instructions

on what type of event was to be recalled:

Here's what we would like you to do:

a. Please recall a time in your life when you witnessed another

person or persons being threatened, abused, picked-on,

put-down, bullied, or embarrassed, not just once or twice,

but repeatedly.

b. This experience should be one in which you did not participate, but witnessed only.

c. The abuse may have been psychological, emotional, or

physical. It could have happened in childhood, in school, at

home, or in your workplace. Examples of common forms

of repetitive abuse include bullying, racism, sizism, homophobia, corporal punishment, and sexual harassment.

Following these instructions were a set of 12 questions.

These were designed to help participants recall the quantitative factual circumstances of the abuse they witnessed (participants' age, sex, and grade level when the abuse took place

and characteristics of the victim) and qualitative aspects that

were more likely to be emotionally charged (physical and/or

emotional nature ofthe abuse; duration, intensity, and frequency

ofthe abuse).

IES-R. Participants filled out the IES-R as a measure of

the level of trauma they experienced as a bystander at the

time ofthe repetitive abuse event they chose to describe. The

instrument is based on the original Impact of Event Scale

(IES; Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979), used in hundreds

of clinical studies over the past 25 years, with precipitating

events that range from a ship capsizing to natural disasters and

bullying. The advantages ofthe IES-R are simplicity (short,

clinically transparent items), ease of administration (less than

10 minutes), and correlation to three ofthe four diagnostic

criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The IES-R asks respondents to identify a distressing or

traumatic event or closely related series of events (anchoring

event) and to report the subjective impact of those events during the previous 7 days by responding to 22 statements, such

as "Any reminder brought back feelings about it" and "I felt

irritable and angry." A 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1

= a little bit, 2 = moderately, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = extremely)

provided scores to yield a total score (0-88) and three subscale

scores (Intrusion, Avoidance, and Hyperarousal).

A number of studies have shown IES-R scores to reliably measure psychological distress and hyperarousal that

can follow exposure to stressful events in both clinical and

nonclinical samples (Janson & Hazier, 2004; Marmar, Weiss,

Metzler, Ronfeldt, & Foreman, 1996; Weiss, Marmar, Metzler,

& Ronfeldt, 1995). Reliability ofthe IES-R scores has been

established using test-retest analyses, item-to-scale correlations, and internal consistency (Weiss, 2004).

The relationship ofthe IES-R to the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for traumatic stress syndromes

provided important construct validity support (Weiss, 2004;

Weiss & Marmar, 1997). Correlations are also high with other

well-established measures, such as the Global Symptom Index

ofthe Symptom Checklist—90—^Revised (Derogatis, 1992), the

Mississippi Scale of Combat-Related PTSD (Keane, Caddell, &

Taylor, 1988), and the Dissociative Experiences Scale (Bernstein

& Putnam, 1986).

The current study used the IES-R as a forensic instrument

to measure participants' recollections of distress levels at

the time they witnessed a series of past events. Accordingly,

the time frame in the instructions section ofthe IES-R was

changed from "during the past seven days" to "during the

time that these stressful life events were occurring." Similar

alterations ofthe time frame ofthe IES and its versions have

been made by other researchers (Janson & Hazier, 2004;

Sanders Thompson, 1996). Reliability ofthe IES-R scores in

the present study was supported by a high degree of internal

consistency using Cronbach's alpha (alpha = .90).

•Results

Research Question 1

To what degree do young adults who were witnesses to lowlevel repetitive abuse at an earlier age recall the level of trauma

they experienced?

The two methods used to evaltiate the degree of trauma first compared the overall means to the original IES level of concern categories and then to IES-R scores from other studies of trauma.

Journal of Counseling & Development • Summer 2 0 0 9 • Volume 87

321

Janson, Carney, Hazier, & Oh

Tests of significance were run to establish whether there

were differences in trauma scores within demographic variables. No category initially demonstrated any significant

differences among groups. The race/culture category, however, showed an unusual pattern where scores for European

Americans (n = 505, M = 15.71) and African Americans (n =

13, M= 15.38) were very similar, whereas scores for Asian

Americans (« = 3, M = 29.0), Latino/Latina Americans (n

= 5, M= 26.0), Native Americans (n = 9, M = 22.2), and

participants in the "other" category {n = S,M= 19.25) were

considerably higher. When categories were collapsed into

Afiican American, European American, and other, an analysis

of variance demonstrated a significant difference {df= 2, F

= 3.85, p = .02). Although the "other" category contained a

small sample size, which must be viewed with caution, this

result does suggest important potential differences between

groups, where Asian Americans, Latino/Latina Americans,

Native Americans, and those who self-identified as "other"

had higher levels of traumatic reactions to their experiences

as bystanders to repetitive abuse when compared with African

Americans and European Americans.

Three different levels of potential concern have been recommended for the original IES instrument based on a total

score of the Intrusion and Avoidance subscales. These levels

of concern are low (0-8.5), medium (8.6-19), and high (> 19

[Zilberg, Weiss, & Horowitz, 1982]).

The Intrusion and Avoidance subscales of the IES-R

summed and adjusted for comparison with the scoring

guidelines of the original IES resulted in a mean of 15.64.

This score places these recollections, of past witnessing of

another person being repetitively abused, above the sub-

clinical range and into the medium range. Symptoms for a

score of 15.64 range from mild to moderate, with levels of

distress sufficiently elevated to warrant further evaluation

and possible clinical intervention.

Current results were also compared with those of other

IES-R studies of people's traumatic symptoms following

earthquakes (Marmar et al., 1996; Weis et al., 1995), and the

results of another set of studies consisting of undergraduate

students following interviews about previously being bystanders

to repetitive abuse situations (Janson & Hazier, 2004; see Table

1). IES-R Trauma subscale scores from the current study were

all higher than those reported by emergency personnel following two different earthquakes. Trauma reports of current study

bystanders were fewer than comparable recalled trauma from

another study of 77 college students following interviews of

their past repetitive abuse witness experience. Scores were similar, however, to student-reported trauma after years had passed.

It should be noted that the scores reflect trauma reactions of

individuals and not the qualities of the events themselves.

Research Question 2

What factors commonly associated with witnessing repetitive

abuse experiences appear to influence how trauma reactions

are recalled by bystanders?

Entry method multiple regression was selected as the primary

analysis method for this question to examine the effect of

predictor variables on psychological trauma. The specific

seven variables selected for this analysis were chosen based

on research and theory that suggests a potential relationship

to the degree of trauma.

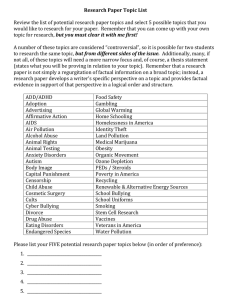

TABLE 1

Studies From the Literature: Subscale and Totai iVIean Scores for the Impact of Event Scale—Revised

Intrusion

Subscale

study and Population

Present study

Undergraduate student reactions to past

witness of common forms of repetitive

abuse (A/ = 566)

Weiss, Marmar, Metzler, & Ronfeldt, 1995

Emergency personnel, San Francisco

earthquake (A/ = 367)

Marmar, Weiss, Metzler, Ronfeldt, & Foreman,

1996

Reactions to earthquake

Police (n= 149)

Firefighters (n = 75)

EMT/Paramedics (n = 100)

Highway staff (n = 115)

Janson & Hazier, 2004

Undergraduate reactions following Interview

on distress as bystander to common

forms of repetitive abuse (A/ = 77)

Current trauma

Past trauma

Avoidance

Subscale

Hyperarousal

Subscaie

Total

Score

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

M

SD

6.08

5.62

6.43

5.35

3.49

3.64

16.03

12.64

4.99

6.05

4.34

6.63

2.08

3.87

—

—

0.5

5.2

5.4

5.1

6.01

5.76

5.91

6.91

3.4

4.8

4.7

4.8

5.55

7.08

6.25

7.70

1.6

2.0

2.5

2.5

3.68

3.18

4.16

4.64

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

6.32

10.66

5.74

6.11

5.53

8.83

5.97

6.32

3.73

7.56

4.49

5.94

15.78

27.05

14.75

16.39

Note. Dashes are used to indicate that total means and standard deviations were not reported.

322

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

Bystanders' Reactions to Witnessing Repetitive Abuse

The regression model predicted an i? of .344, (R^=.ll9, SEE

= 11.85), which was found to be significant (df= 1,F= 9.26,/» =

.00) based on results of a follow-up analysis of variance. These

results identify a significant but small prediction value where

approximately 12% of the variance in psychological trauma

reactions could be attributed to the combination of the situation

(abuse type,frequency,duration, and intensity) and human factors

(witness sex, victim sex, and witness grade level ). An examination of coefficients relating each of the predictor variables to the

regression formula demonstrates that the greatest contributor

to regression model significance was how people answered the

question on intensity of abuse they observed. Additional analysis of structure coefficients also indicated that intensity was the

noteworthy predictor of trauma (see Table 2).

•Discussion

Levels of Trauma

The Intrusion and Avoidance subscales from the IES-R were

summed and adjusted to allow for result comparisons to scale

criteria for the original IES. The overall adjusted IES-R mean

of 15.64 was found to be in the medium range (8.6-19), which

is defined as a level of distress high enough to warrant fiirther

evaluation and possible clinical intervention. This finding

suggests that participants experienced significant traumatic

reactions as a result of witnessing common forms of repetitive abuse between their peers, reactions that were significant

enough to call for direct attention by counselors.

Trauma recalled by bystanders in the current study were

found to be substantially higher than levels found in emergency workers, firefighters, police, paramedics, and highway

workers following earthquakes in California (Marmar et al.,

1996; Weiss et al., 1995). In another recent study (Janson &

Hazier, 2004), undergraduates recalling being bystanders to

repetitive abuse demonstrated even greater differences in

recalled trauma compared with these emergency workers

and had higher levels of trauma than did the bystanders in

the current study. These results suggest that the experience of

witnessing common forms of repetitive abuse in childhood or

adolescence generated higher levels of psychological trauma

in bystanders than has been reported by other groups following

events such as earthquakes, where injury, death, and destruction are objectively viewed as far more catastrophic.

TABLE 2

Seven-Factor Regression Model

Variable

Constant

Abuse type

Frequency

Duration

Intensity

Witness sex

Victim sex

Witness grade level

ß

-.23

.00

.03

.32

.00

-.03

-.07

f

Sig.

0.53

-5.17

0.06

0.76

7.30

0.03

-0.65

-1.53

.599

.606

.951

.446

.000

.976

.515

.128

Note. Sig. = significance; SC = structure coefficient.

SC

0.04

0.01

0.29

1.02

0.06

-0.19

-0.24

One consideration in the evaluation of these results is that

the current study took the least threatening, least arousing

method of measuring trauma levels by asking students sitting

in a classroom to recall on their own how they experienced

being a bystander to repetitive abuse at the time the abuse was

occurring. It could be expected that recalling these memories

from years past might produce very different responses than

from individuals experiencing the freshness of memory, tension, and direct involvement resulting from the catastrophic

events described in the earthquake studies. Traumatic stress

symptoms tend to recede over time (Sundin & Horowitz,

2003), and one would expect that levels of distress associated

with recalling past bystander experiences would be lower than

if measured at the time of the experience, to the degree that

those memories of pain and suffering had faded over time.

The Janson and Hazier (2004) study took a more aggressive

approach by individually interviewing students for 15 or 20

minutes about their past experiences before asking them to recall

their trauma symptoms. Present tensions and traumatic memories

might well be fewer because of the absence of talking about the

past event with another person over a 15-minute period.

One thought-provoking finding was that racial/cultural

factors resulted in different reported trauma levels. The

limited number of non-European Americans involved in

this study emphasizes caution in the interpretation of findings that show significantly higher levels of recalled psychological trauma for minorities. African Americans had

a mean score quite close to that of European Americans,

but Asian Americans, Latino/Latina Americans, and Native

Americans, along with participants in the "other" category,

reported considerably greater psychological trauma. There

is a paucity of literature on this topic; however, one possible

explanation for this finding may be the differing levels of

language, accent, immigration, and assimilation separating

Caucasian and African American students from Asian, Native

American, and Latino/Latina students. Findings reported by

Rosenbloom and Way (2004) on comparative discrimination

among young people support this view and suggest that differences in patterns of victimization may be due to the fact

that Black and Latino high school students reported higher

levels of repetitive abuse at the hands of adults (e.g., teachers, police officers, administrators), whereas Asian American

students reported greater harassment from peers. These researchers found that teachers and other adults often favored

Asian Americans students, based on the biased perception

that Asian American minorities focus on academic achievement and are model students, a perception that Latino and

African American students clearly recognized and reacted

to by abusing their Asian American peers. Numbers are too

low to draw major conclusions, but the pattern does highlight

concerns that minorities experience more frequent harassment, which may consequently infiuence them more than it

does nonminorities (Fitzpatrick, Dulin, & Piko, 2007; Fox

& Stallworth, 2005; Graham & Juvonen, 2002).

Journal ofCounseling & Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

323

Janson, Carney, Hazier, & Oh

Factors Related to Trauma

The findings on situational factors expected to predict the

amount of trauma experienced provided mixed results. The

only situational factor found to be significantly related to bystander-recalled trauma was bystanders' rating of the intensity

of abuse. Multiple regression analysis indicated that type of

abuse, fi-equency, and duration did not appear to infiuence

trauma levels significantly for this sample. This finding goes

against most of the literature on bullying and harassment that

suggests these factors would have an interaction effect that is

not apparent in the current study data.

One explanation for this finding might be that participants

were asked to "please recall a time in your life when you witnessed another person or persons being threatened, abused,

picked-on, put-down, bullied, or embarrassed, not just once

or twice, but repeatedly." This request may have focused

participants on the single most severe episode of abuse rather

than focus on the repeat aspect of the behavior.

The potential roles of participants' sex and grade level of

the event and victims' sex were also not found to be significant predictors of recalled trauma levels. It is possible, based

on the findings, that although these factors are significant in

determining how (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995) or why (Nansel

et al., 2001) repetitive abuse occurs, they may not affect the

degree to which a person is hurt by the experience.

It is essential to interpret the results of this study as individual

reactions to events and not the events themselves. Similarities

in recollection of trauma responses to widely varied Stressors

suggest that trauma is, to a great extent, a subjective and phenomenological experience (Shopper, 1995). This perspective is

particularly important when consideration is given to the links

between stress and somatic symptoms (Selye, 1976), emotional

dysfimction (Allen, McBee, & Justice, 1981), and later life

satisfaction (Royse, Rompf, & Dhooper, 1991).

•Conclusion and Clinical Implications

The most significantfindingfi'omthis study for counselors is that

participants clearly recalled experiencing psychological trauma at

levels of distress that would call for increased attention to youthfiil

bystanders ofrepetitive abuse. Victims ofbullying, harassment, and

other forms of repetitive abuserightfiillydeserve priority attention

from the counseling profession, but it has become increasingly clear

that many bystanders share symptoms and emotional responses

with direct victims and need such attention as well (O'Brien, 1998).

Ifbullying is the harmless, developmentally appropriate experience

it is often said to be—especially for bystanders who are frequently

believed to be just passive observers—one would expect any report

of distress levels to remain in a subclinical range. This was certainly

not what students reported in this study and others (e.g., Janson &

Hazier, 2004). The results of moderate to high IES-R scores give

rise to potential clinical considerations for bystanders to repetitive

abuse at least in terms of assessing their needs as counselors would

do for hurricane or earthquake survivors.

324

Various forms of violence, war, and terrorism first brought

attention to the problems of bystanders who witness degradation, injury, or death of others. More current research is now

providing data on the need to accept a higher level of concern

and attention for bystanders of childhood repetitive abuse situations. Counselors are aware that trauma is often expressed in

youth as depression, anxiety, helplessness, somatic complaints

such as severe headaches/stomachaches, and truancy for many

youth who fear the school environment (Rigby, 2002). The

bystanders in the current study were no different as we can

see in excerpts of their many statements showing the complex

emotions of anger, hurt, sadness, and frustration.

Sample Quotes of Affective Reactions and Somatic

Complaints From Bystanders

Sadness andfear. "The emotional abuse of name-calling was

extremely significant. It made me very tense and sad all the

time because I thought they might start making fun of me."

"This boy from school was tall and had bright red hair.

People would taunt him.... He would go on rampages down

the hall. It was really scary. He tried to punch me once because

I was the closest person to him."

Anger and emotional pain. "One boy in particular would

say the meanest things to her, all the time calling her. . . . I

was so mad and hurt by this boy's actions all through middle

school and early into high school."

Helplessness. "People made fun of her because she was

overweight and always wore stretchy clothes. . . . As 1 look

back on it now, it really bothers me. I am so sad and I feel

like I was a coward too."

Physically sick. "It really gave me a sick feeling. The

constant picking on the kid always made me want to say

something, but I didn't know what and I never did."

Intervention and Prevention

The first step for providing support to bystanders is enhancing

counselors' understanding of bystanders' realities by assessing

the level of trauma that bystanders are experiencing. Specifics

to assess are (a) type of witnessed abuse; (b) relationship to

the abuse victim and/or perpetrator; (c) intensity, frequency,

and duration of witnessed abuse; and (d) bystanders' emotional state such as depression, anxiety, anger, and so forth.

Assessing these specific indicators will assist counselors in

developing treatment strategies.

Two key therapeutic approaches have been suggested in

working with individuals exposed to trauma and repetitive

abuse—^narrative therapy for all clients and play therapy specifically for children. The narrative therapy process entails the

telling and retelling of the experience through counselor-guided

questions allowing individuals to seek a more realistic perspective affording them greater options for dealing with the trauma

(Payne, 2006; Shapiro, Friedberg, & Bardenstein, 2006).

Play therapy is used across cultural contexts (Landreth,

2002) with children having various clinical disorders includ-

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

Bystanders' Reactions to Witnessing Repetitive Abuse

ing symptoms assoeiated with trauma (Kot & Tyndall-Lind,

2005), Posttraumatic play therapy is designed speeifieally

to maximize treatment efforts through structured strategies

incorporated into treatment plans (Dripchak, 2007),

Prevention programs for bullying and harassment have increased dramatically over the past decade because the extent of

the problems has become more apparent to counselors and other

professionals dealing with youth. The vast majority of these programs place primary emphasis on investing all students, faculty,

and staff in understanding the problems and providing them vnth

ways to take effective prevention, intervention, and supportive

actions (Hazier & Carney, 2006). Bystanders are appropriately

identified in these programs as helpers in these efforts while their

own psychological needs are generally not addressed. Bystanders

are often the underserved and undertreated population in response

to trauma. As research continues to identify additional difficulties experienced by bystanders, counselors must be prepared to

teach these youthfijl witnesses to identify and seek appropriate

assistance for the trauma they are experiencing,

•References

Allen, R, H,, McBee, G,, & Justice, B, (1981), Influence of life

events on psychosocial functioning. Journal of Social Psychology, 113, 95-100,

American Psychiatric Association, (2000), Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed,, text rev,), Washington,

DC: Author,

Bernstein, E, M,, & Putnam, R W, (1986), Development, reliability,

and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease, 174, 727-735,

Boney-McCoy, S,, & Finkelhor, D, (1995), Psychosocial sequelae

of violent victimization in a national youth sample. Journal of

Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63, 726-736,

Carney, J, V (2000), Bullied to death: Perceptions of peer abuse

and suicidal behavior during adolescence. School Psychology

International, 21, 44-54,

Carney, J, V, & Hazier, R, J, (2001), How do you know if it's bullying?

Common mistakes and their consequences, Topic-Educational

Research, 26, 1-4,

Carney, J, V, Hazier, R, J,, & Higgins, J, (2002), Characteristics of

school bullies and victims as perceived by public school professionals. Journal of School Violence, 3, 91-106,

Cole, J, C, M,, Cornell, D, G,, & Sheras, P (2006), Identification of

school bullies by survey methods. Professional School Counseling, 9, 305-3 \2.

Craig, W, M,, Henderson, K,, & Murphy, J, G, (2000), Prospective

teachers' attitudes toward bullying and victimization. School

Psychology International, 21, 5-21,

Crick, N, R,, & Grotpeter, J, K, (1995), Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development,

66, 710-722,

Derogatis, L, R, (1992), SCL-90 administration, scoring & procedures

manual—//, Townson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research,

Dripchak, V L, (2007), Posttraumatic play: Towards acceptance and

resolution. Clinical Social Work, 35, 125-134,

Espelage, D, L,, & Swearer, S, M, (2003), Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we

go from here? School Psychology Review, 32, 365-383,

Fitzpatrick, K, M,, Dulin, A, J,, & Piko, B, F, (2007), Not just pushing and shoving: School bullying among African-American

adolescents. Journal of School Health, 77, 16-22,

Fox, S,, & Stallworth, L, E, (2005), Racial/ethnic bullying: Exploring

links between bullying and racism in the US workplace. Journal

of Vocational Behavior, 66, 438-456,

Garbarino, J, (2001), An ecological perspective on the effects of violence

on ááWtn. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 361-378,

Gilligan, J, (1991, May), Shame and humiliation: The emotions of

individual and collective violence. Paper presented at the Erickson

Lectures, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA,

Graham, S,, & Juvonen, J, (2002), Ethnicity, peer harassment, and

adjustment in middle school: An exploratory study. Journal of

Early Adolescence, 22, 173-199,

Hanish, L, D,, & Guerra, N, G, (2000), The roles of ethnicity and

school context in predicting children's victimization by peers,

American Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 201-223,

Hazier, R, J, (1996), Breaking the cycle of violence: Interventions for

bullying and victimization. New York: Taylor & Francis,

Hazier, R, J,, & Carney, J, V, (2000), When victims turn aggressors:

Factors in the development of deadly school violence. Professional School Counseling, 4, 105-112,

Hazier, R, J,, & Carney, J, V (2006), Critical characteristics of effective

bullying prevention programs. In S, R, Jimerson & M, J, Furlong

(Eds,), Handbook of school violence and school safety: From research to practice (pp, 273-292), Mahwah, NJ: Eribaum,

Hazier, R, J,, Carney, J, V, Green, S,, Powell, R,, & Jolly, L, S, (1997),

Areas of expert agreement on identification of school bullies and

victims. School Psychology International, 18, 5-14,

Hazier, R, J,, Miller, D,, Carney, J, V, & Green, S, (2001), Adult

recognition of school bullying situations. Educational Research,

43, 133-146,

Horowitz, M, J,, Wilner, N,, & Alvarez, W, (1979), Impact of Event

Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine,

41, 209-2\&.

Hosch, H, M,, & Bothwell, R, K, (1990), Arousal, description and

identification accuracy of victims and bystanders. Journal of

Social Behavior and Personality, 5, 481—488,

Janson, G, R,, & Hazier, R, J, (2004), Trauma reactions of bystanders and victims to repetitive abuse experiences. Violence and

Victims, 19, 239-255,

Keane, T M,, Caddell, J, M,, & Taylor, K, L, (1988), Mississippi

Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 35-90,

Kot, S,,&Tyndall-Lind, A, (2005), Intensive play therapy with child

witnesses of domestic violence. In L, A, Reddy, T Files-Hall,

& C, Schaefer (Eds,), Empirically based play interventions for

children (pp, 31-49), Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association,

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87

325

Janson, Carney, Hazier, & Oh

Landreth, G. L. (2002). Play therapy: The art ofthe relationship

(2nd ed.). New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., Metzler, T., Ronfeldt, H., & Foreman, C.

(1996). Stress responses of emergency services personnel to the

Loma Prieta Earthquake Interstate 880freewaycollapse and control

traumatic incidents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 63-85.

Monks, C. P., & Smith, R K. (2006). Definitions of hullying: Age differences in understanding ofthe term, and the role of experience.

Journal of Developmental Psychology, 24, 801-821.

Morgan, J., & Zedner, L. (1993). Researching child victims: Some

methodological difficulties. International Review ofVictimology,

2, 295-308.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton,

B., & Scheidt, P (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth:

Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal

of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094-2100.

Nishina, A., Juvonen, J., & Witkow, M. R. (2005). Sticks and stones

may break my bones, but names will make me feel sick: The

psychosocial, somatic, and scholastic consequences of peer

harassment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 3 7 ^ 8 .

O'Brien, L. S. (1998). Traumatic events and mental health. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Olweus, D. (1996). Bully/victim problems at school: Fact and effective intervention. Journal ofEmotional and Behavioral Problems,

5, 15-22.

Payne, M. (2006). Narrative therapy: An introduction for counselors

(2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P (1993). The NIMH Community Violence Project: I. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence.

Psychiatry, 56, 7-21.

Rigby, K. (2002). New perspectives on bullying. Philadelphia: Jessica

Kingsley Publishers.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. (1999). Suicidal ideation among adolescent

school children, involvement in bully-victim problems and perceived social support. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior,

29, 119-130.

Rosenbloom, R. R., & Way, N. (2004). Experiences of discrimination

among African American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth & Society, 35, 420-451.

326

Royse, D., Rompf, E. L., & Dhooper, S. S. (1991). Childhood trauma

and adult life satisfaction in a random adult sample. Psychological

Reports, 69, 1227-1231.

Safran, S. P, & Safran, J. S. (1985). A developmental view of children's behavioral tolerance. 5eÄav/ora/£)isorí/ew, 10, 87-94.

Sanders Thompson, V (1996). Perceived experiences of racism as

stressful life events. Community Mental Health Journal, 32,

223-233.

Selye, H. (1976). The stress of life. New York: MacMillan.

Shakoor, B., & Chalmers, D. (1991). Co-victimization of AfricanAmerican children who witness violence: Effects on cognitive,

emotional, and behavioral development. Journal ofthe National

Medical Association, 83, 233-238.

Shapiro, J. P, Friedberg, R. D., & Bardenstein, K. K. (2006). Child

and adolescent therapy: Science and art. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Shopper, M. (1995). Medical procedures as a source of trauma. 5«/letin ofthe Menninger Clinic, 59, 191-204.

Smith, P K., Nika, V, & Papasideri, M. (2004). Bullying and violence in

schools: An international perspective and findings in Greece. Psychology: The Journal ofthe Hellenic Psychological Society, 11, 184-203.

Sundin, E. C , & Horowitz, M. J. (2003). Horowitz's Impact of Event

Scale evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosomatic Medicine,

65, 870-876.

Weiss, D. S. (2004). The Impact of Event Scale—Revised. In J. R

Wilson & T. M. Keane, Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD

(2nd ed., pp. 168-189). New York: Guilford Press.

Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The Impact of Event S c a l e Revised. In J. P. Wilson &T. M. Keane, Assessing psychological

trauma and PTSD (pp. 399-411). New York: Guilford Press.

Weiss, D. S., Marmar, C. R., Metzler, T. J., & Ronfeldt, H. M.

(1995). Rredicting symptomatic distress in emergency services

personnel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63,

361-368.

Wolke, D., Woods, S., Bloomfield, L., & Karstadt, L. (2001). Bullying involvement in primary school and common health problems.

Archives of Disease in Childhood, 85, 197-201.

Zilberg, N. J., Weiss, D. S., & Horowitz, M. J. (1982). Impact of Event

Scale: A cross-validation study and some empirical evidence supporting a conceptual model of stress response syndromes. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50, 407—414.

Journal ofCounseling& Development • Summer 2009 • Volume 87