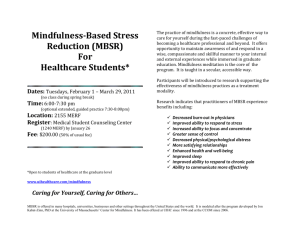

56 ALTERNATIVE THERAriES. MAY/|UNE 2005, VOL, II, NO. 3 Conver'iations with [on Kahat-Zinn, i'hi CONVERSATIONS JON KABAT-ZINN, PHD BRINGING MINDFULNESS TO MEDICINE Interview by Karolyn A. Gazella • Pliotograpliy by MilliceiU Harvey Jon Kabal-Zinn. I'hn. is Professor of Medicine Enwrilus al ihe University of Massachusetts Medical School. Worcester. Mass, where he was the founding executive director ol the Center lor Mindfuhiess in Medicine, Health Care, and Society. He is the Jormer Director of the Center's world-renowned Stress Reduction Clinic. Under his direction, the Center lor Mindjtilncss conducUd mindfulness-based stress-reduction (MBSR) courses in the inner citv and the Massachusetts state prison system. Today, more than 200 centers und clinics use the MBSR model, including 17 in the Kaiser-Pernianente ,^'steni in northern Calijornia. Dr. Kahat-Zinn reeeived his PhD in molecular biology from the Massaehitsetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Cambridge. From 1979 to 2002. his research foeused on the elinieal applieations of mindfulness meditation training for people with chronic pain and stress-related disorders. He is a founding fellow of the Feizer Institute, a Fellow of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, and a niemher of the Board of the Mind and Life Institute, a group that organizes dialogues hetween the Dalai Lama and Western scientists to promote a deeper understanding of different ways to know and prohe the nature of mind, emotions, and reality. Dr. Kahat-Zinn is a .sought-after lecturer and an accomplished author. His latest hook. Come to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Throngh Mindfulness. was released in January 2005. class, hard-core, data-driven scientist. He was a molecular immunologist at Columbia University Medical School. My mother was a prolific painter, but she never showed her work. My father got a huge amount of recognition for his groundbreaking work in ininumology. and my mother never got any recognition for her paintings outside the family and a small circle of friends. But she was an extraordinary painter and loved art and music. She would take me to tbe Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art almost every weekend io look at paintings. When 1 was very young, three to five years old. I even attended art school at the Museum of Modern Art. I don"t recall being particiihirly enamored with art as a young child. I think I used up all of my artistic talent in one clay elephant that I made when 1 uas five years oid. and never went anywhere after that. Aiternative Therapies (AT): Was there a series of events or crossroads that led you to take your particular professional path? I think living and growing up in that kind ofa household, what CR Snow, the British author and physicist, referred to in the 19.S0S as "the two cultures." influenced me greatly. There is the culture of the humanities and the culture of the sciences. They speak different languages and have different perceptual frameworks for understanding reality, but neither is complete without the other. In fact, there are many more cultures than just those two. There are all sorts of different wa)'s of knowing the world. And it's not just the outside world that is important, but the inside world as well. That, of course, didn't get as much credence in my family or in my scientific training. 1 think growing up in a faniih' like that gave me a profound love of learning and a profound love of seeing, of appreciating the beauty in the light shimmering off ofa pond or the many different colors in one flower. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD: This is a wonderful line of inquiry. What are the factors that determine how a person's life unfolds? It's very hard to put my finger on i t ^ t o say, "yes. it happened then." In retrospect, however, there are antecedents that were instrumental in nudging me along a specific path, one of which is that 1 grew up in a family in which my father was a world- Another element that caused me to choose my professional path is a love for science and for the importance, in my mind, of trying to understand the nature of nature, the nature of reality, and the nature of ourselves as human heings. That's uhat biology is all about—the study of life and living .systems. The subtext is, what can we learn by studying other organisms that might influence how we know ourselves and how we can Jon KabatZinn, PhD, .shown here outside his home in Mass. works to bring mindfulness into the mainstream ofmedicine. plume, (7<iO) (i.U-.mil or (1166) S2S-2%2:fax. (7601 633-3918: e-mud. uliernolive.thmipies^) innerdotmniv.nm. Recently. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine interviewed Dr. Kahat-Zinn in San Diego, following a presentation at the Scripps Centerfor Integrative Medieine. itii Ion Kat>ai-Ziiin. I keprtnl reque^lv. tnniiVi^tiin Ciimnuintaitii'n\ !MSiixmiy Rd. Siiilt IO,i, Ijhiniliis, t.l ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES. MAY/|UNt 2005. VOf. H. NO. 3 ^2024: 57 cure a disease? At the same time, I was very intrigued by the question of consciousness. Since consciousness conies out of biology, the question is, what is the relationship of consciousness to biology? What influence do our thoughts and emotions have, and how does all of this activity happen in the complex nervous system, which includes perhaps 10 trillion neurons and countless other cells? Another turning point came when I was 15 years old and my father took me to Europe on one of his sabbaticals. 1 attended a French high school in Paris. It turned ouf to be one of the top three Lycees in the country. It was a real powerhouse, the quintessence of the French educational system. And I didn't know any French. I had gone to Stuyvesant High School in New York City and got 100 (a perfect score) on the New York State Regent's exam in lOth-grade geometry. Then I went to 11th grade at the Lycee Henri IV in Paris and was shocked to learn that I was five years behind in geometry and preffy much every other subject, including Fnglish. It took me three months to learn French, and it opened my mind. A different culture has an entirely different way of looking at the world. There is a huge amount of overlap, but when you think in French, you think different thoughts to some degree than you think in English. For example. French has one-fifth the number of words that English does. In fact, there is no French word for mindfulness. You have to use five or six words just to say "mindfulness." All of these things made an impression on me when 1 was growing up. My idea was to become a basic scientist, a molecular hiologist. and just push fhe frontiers of understanding the nature of living systems. But 1 was interested in the subtext of the nervous system—in how we generate consciousness, how we see. how we hear, and how we know. While I was studying molecular biology at Mff. my horizons began to expand even more. After all, it was Cambridge in tbe mid-19(i0s. It was a period of amazing growth, social inquiry, :md discovery. You could get an incredible education just hy going to seminars at MIT and Harvard. You hardly had to be enrolled in school: you could just attend all of these different seminars. Plus, it was a time when every swami, guru, and meditation teacher was coming to Cambridge, peddling their wares, so fo speak, "t'ou could get an incredible parallel education by seeing what all of these people froiTi other cultures had to say about the power of the mind. Philip Kapieau. author of The Three Pillars ol Zen. came to MIT at the invitation of Houston Smith. I was walking down the corridor at MIT one day. depressed because of the Vietnam War. things not going well in the lab, and all sorts of other things, and I saw a sign on the u all saying, "The 'Fhree Pillars of Zen," a talk by Philip Kapieau. at the invitation of Houston Smith. I had no idea what Zen was. I had no idea who Philip Kapieau was. I had no idea who Houston Smith was. for that mafter. But I went to that talk. Why, I can't really say. Something told me there would be something interesting tbere. and it bad to do with the nature of consciousness. At the tinte, I did know that Zen was a form of meditation that came 58 out of the East. But on that particular afternoon. I didn'f want to go back to the lab so 1 went to the talk. Very few people attended the talk, maybe four or five out of all of MIT. Kapieau just blew the top off my head. I had never heard anybody talk like that. He told his personal story about being a reporter at the Nuremberg War Trials and how, afterwards, he wound up sitting in some freezing cold monastery in tbe middle of winter in northern Japan, and after six months his ulcers went away. He began to feel like a human being fbr the flrst time in his life. So. I'm (aking this all in and it's quite amazing. He explained that if's about paying attention to your own inner experience hy quieting the mind, by investigating the mind through direct first-person experience. Of course, from the outside it just looks insane, you are just sitting there doing nothing. But if turns out that just sitting tbere doing nothing may be tbe hardest work in the world. and it may be its own form of laboratory investigation. The laboratory of your own life may be at least as valid to look at as the laboratory of other people's brains or nervous systems, or as designing experiments in the lah to test one thing or another, which is a third-person orientation. But the first-person orientation is, "Who am I?" Why not bring scientific rigor to tbat kind of inquiry? Wh}' not use all the instruments at our disposal—our multiple senses? I would say there are more than five of them—including the capacity to refme awareness. Perhaps we can then find a way to come to some kind of greater integrity' and balance in our lives. So it's not just about accomplishing great things and pushing back the frontiers of science, but also living your own life with a degree of balance and well-being that might influence not only physical health, but also mental and spiritual health. So these were all threads that got woven into a tapestry that looks like it is the story of Jon Kabat-Zinn. But there are many different threads in anyone's story, and many different ways we might tell our stories, so it is hard to put your finger on what is behind all tbe narratives, something deeper and perhaps truer. Although it may be important in some respects to share one's story with the world in some way, what's more important is living your life as if it really matters. The underlying message in the work of the past 25 years in the stress-reduction clinic and the Center for Mindfulness is that it is not about the story of the personal pronoun, of "I" and "me." but about a deeper knowing tbat we are capable of. that comes out of silence, stillness, clear seeing, and embodied wakefulness, a knowing ihat doesn't take the vagaries of life so personally. AT: What is the emphasis of your work right now? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: I view this work of "coming to our senses," the title of my latesf book, as being very real in our own lives and minds. It is a core element at the heart of healing. Eor that to happen, we have to cultivate intimacy with aspects of our being that we don't even know are possible, one of which is stillness—being silenf and dropping underneath onr stories and underneath and in between our thoughts, and again, not tak- ALTERNATIVG THERAPIbS. MAY/|UNE 2005, VOL 11. NO. 3 CnnversaliLiiis vxith Ion Kabat-Zinn. PhD ing them personally or as the truth of things when they are only opinions and interpretations. We bave the innate capacity for a more accurate seeing, for learning, growing, healing, and transformation across our entire life span. \bu are the authority and the author of your own life. If you are always paying attention to other people's lives rather than your own, you are missing not only the point, you are missing your life. The challenge is to live your life as if it really matters. And to be conscious of how you conduct your life—from what you eat and drink to the newspapers you read and the television programs you watch, to how you are in relationship with everything, with those you love, with nature, with your body, with the world. some people have been investigating this subject in different ways. A leader in the fleld is the late Francisco Varela, Co-Founder of the Mind and Life Institute, a group that conducts periodic dialogues between Western scientists and the Dali Lama and other contemplativeson tbe nature of reality, mind, life, and so forth. Francisco emphasized the key importance of mindfulness or mindful awareness within tbe discipline he called neuro-phenomenology, within fhe framework of cognitive neuroscience. From fhe start, the nature of first-person experience and the nature of awareness has been at the heart of these conversations—including the public meeting we held at MIT in 2003, called "Investigating the Mind." We are going to be holding another public dialogue in Washington, DC, in November 2005, also on Investigating the Mind, emphasizing the science and clinical applications of meditation. EING PRESENT IS NOT THAT SIMPLE. WE HAVE TO WORK TO GET BETTER AT BEING PRESENT WE DO THAT BY CULTIVATING MINDEULNESS— MOMENT-TO-MOMENT NON-JUDGMENTAL AWARENESS. , Everything has an influence on us in ways that can influence our mental health and well-being. The challenge is. can we live more consciously? In a sense, mindfulness and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) are really about the art of conscious living. That would also include MBSR's "kissing cousin," mindfulnessbased cognitive therapy. There is also a growing number of other mindfiilness-based interventions, including mindfulnessbased eating interventions for people with eating disorders and addictions. Our work in .MBSK is based on the conviction that human beings are miraculous beings, and we have infinitely more capacity and dimensions associated with our brains and our ner\ ous systems, u ith our deep intelligences—and I emphasize the plural—that we usually simply ignore. Even the educational system emphasizes on!\' certain aspects of development, such as critical thinking, but it doesn't emphasize somatic experience or intuitive experience or the cultivation of compassion or, for that matter, self-compassion or empathy and all sorts of other aspects of being human—including perhaps the most fundamental of all—awareness itself, which is an innate capacity we share by virtue of being human. And yet. there are no courses that I know of in the educational system that explicitly refme and cultivate awareness. There's also relatively little research investigating what awareness is and how it comes about. This is, in part, because it is so difficult even to conceptualize. It's like the eyeball trying to look at itself and understand wbat it is. But from a biological and neurological standpoint, it is wonderfully interesting, and Conversations with Jon Kabat-Zinn, AT: And these are for healthcare professionals? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: Yes, and neuroscientists. In fact, it will be held in conjunction with the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, for which the Dali Lama is gi\ing the opening keynote address. Never before bave these uni\erses been so poised for mutual exploration, opening up the possibility of exploring profound contemplative experiences and capacities and how they might interface with science and medicine to increase our understanding of tbe mind itself, and of our humanity. These conversations take place at the highest levels of scientific rigor. This is not some kind of airy, fairy, new-wave, spiritual self-congratulatory effort. We are talking about a valid scientiflc inquiry that expands the domain of what it means to be human, what it means to be a scientist, and how to use one's mind in multiple channels to investigate the nature of the mind itself. AT: From a practical standpoint, why is if important for a healthcare professional to practice mindful medicine? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: It goes back to the Hippocratic oath: "First do no harm." Human beings are very sensitive beings. We are sensitive to relationality. the relationships we are in with each otber and tbe world. One of the most profound ways to harm another person is to disregard him or her. That is particularly AfTl^KNATiVE THEFIAPIES, MAY/JUNE 2005, VOL If NO. 3 59 wounding if the person is already vulnerable because he or she has some kind of health problem. Patients go to their doctor because either something is worrying them or they are in pain. It's part of the Hippocratic commitment to real!)' be present for a person who is in a vuhierable state. But being present is not tbat simple. We have to work to get better at being present. We do that by culti\'ating mindfulness. Mindfulness, as I define it operationally, is moment-tomoment, non-judgmental avvarene.ss. It is cultivated attention in a particular way, namely, on purpose in the present moment—and. I emphasize, non-judgmentally. As a rule, this kind of attention, although we are all capable of it and use it sometimes, has to be cultivated through practice for it to become at all robust and reliable, it is not just a good idea because without specifically nurturing it, left to our own devices, we so easily get carried awa\' by streams of tbought. by how busy we are. by what's happening with the previous patient we saw or tbe next patient. It is very difficult to just he with a patient unless you are trained to watch out for all of the ways your own mind can subvert you, interrupt you, or divert you to some other place. The patient, of course, is an extremely sensitive instrument for detecting our attention. Patients know when we are not paying attention to them. That is the core reason fbr cultivating mindfulness. A large part of it is learning how to listen, how to see and hear heneath surface appearances. rather than at the patient, typing the whole time, so his or her attention is already split. Many doctors multitask. This can make patients feel disregarded. If there isn't an empathic connection, patients may not feel comfortable telling doctors what's really on their mind and what tbeir fears and concerns are. The doctor gives them the impression he or she doesn't have time to hear it anyway. Valuable diagnostic information often does not get into a patient's chart because the patient doesn't feel comfortable telling the doctor what's really going on. Our former Chief of Medicine at UMass, Dr. James Dalen, who became Dean at fhe University of Arizona School o( Medicine, used to say tbat if you want to know what's going on with the patient, ask the patient. But then, you also have to listen. Mindfulness reminds us of the Hippocratic oath so that we don't unwittingly betray the very calling of medicine, it also helps us bring the art and tbe science of medicine together in the 21st century. AT: Are we any closer to getting mindfulness training into medical schools? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: I think so. It is gradually entering mainstream medical education, and some places are accepting if more cjuickly than others. I recently heard of two places where MBSR is being incorporated into residence training programs. And Another part of learning is recognizing that all interactions, especially in medicine, are in some way intimate communications. If you are not aware that a patient values your words as a physician, as an authority figure, you may influence the patient in ways you had not intended. Just with tone of voice and choice of words, you are sending the patient signals about his or her diagnosis or prognosis. You may be broadcasting all sorts of things you are not even aware of, just through your soma. your own body language, For example, and we teach this in medical school, do not talk to the patient with your hand on the doorknob. If you are feeling rushed or impafient. deal u ith it inwardly because otherwise you are showing severe disregard to the patient. How can we titrate that in a way that is manageable and sensible? That is the art of clinical medicine. It is what used to be called good bedside manner. It is a teachable, meditative art. AT: Is your philosophy that even if a healthcare professional has only 15 minutes fbr the patient, he or she can make the best of those 15 minutes by being mindful? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: I don't want to give the impression that I am in favor of making the medical encounter shorter and shorter. Short office visits are disrespectful to the patient and maddening and stressful for both the physician and the patient. The movement to make the clinical encounter as short as possible is a travesty in many ways because it doesn't give the patient time to even say why be or she is there. I know this from first-hand experience with my mother and my own experience with physicians. Often, the doctor is looking at the computer screen 60 ALTERNATIVE THERAI'IES. MAY/JUNE 2005, VOE. il. NO. 3 Conversations with Jon Kabal-Zinn. it's not just mindfulness per se. It's also, fbr example. Dr. Rachel Remen's course on the healing art. which is spreading through medical schools like crazy because it's so compelling and beautiful. It's about understanding your own interiorifies so that you can be emotionally intelligent in front of the patient, way beyond merely doing a skillful clinical assessment or diagnosis or treatment. Remember that it's the interaction. the relationship, that is most important. If you are practicing great medicine but bave an emotionally myopic reiationship with the patient, it may become iatrogenic in one way or another. I want to add that if a docfor has only 10 minutes. 10 mindful minutes is actually a huge amount of time because there are an infinite number of moments in 10 minutes to a first approximation. There is the same number of moments to a first approximation as there are in an hour. So it is important to make the best use of the moments you have, outside of time. and to be aware of what's important: the quality of your listening and the quality of your embodied presence, rather than just getting through a checklist in those 10 minutes. This can make even a 10-minute encounter extremely satisfying for the patient, or at least take the edge off tbe brevity of it. Sometimes it helps even to acknowledge that explicitly. MSBR is now being used in medical centers and clinics and hospitais around the country and around the world. And as it becomes more widely available in hospitals, doctors will ConviTsations wiili Jon Kabat-Zinn, be able to say after a 10-minute encounter with a patient, when appropriate. "We have a program where you can actually train in cultivating aspects of your own being that might be valuable complements to what I can do to help you move toward greater levels of health and well-being. It's called the Stress Reduction Clinic, and if you are open to it, I'd like to refer you there so that you can do your part, in partnership uith us, to cultivate aspects of your being to which you [nay not have paid much attention, but that might have a profound effect on your mental and physical health. Tben I will check back uith you Irom time to time to see how it's going." Can you imagine how healing and how stress-reducing thaf would be for a physician? Patients who are not doing well or have psycho-social stress and problems or are falling through cracks of the system for whatever reason could be sent to a place where they couid train to tap into tbeir own interiority and tap their own deep inner resources for learning, growing, healing, and transformation. A lot of what has heen considered "alternative medicine" has reached a point where it is perceived as having much more virtue and value rather than being perceived as a liability because it is strange. Today. 1 don't think anyone thinks meditation is weird, whereas 25 years ago, virtually everybody in the mainstream tbought it was weird. Twenty-five years ago. the idea of bringing meditation into medicine got a reaction kind of like: "Wait a minute! We have spent the last 100 years trying to fmd AETERNATIVE THERATIES, MAY/JUNE 2005, VOL 11. NO. 3 61 a scientific foundation for medicine, which was, to a iarge degree, just voodoo before tbat. And now all ot the sudden, yoga and meditation are fmding their way in, pulling the deep foundation out of the rational scientific framework of medicine." But nou: that view is very much in abeyance. People now recognize that the words medicine and meditation sound very similar, and that's because the)' come from the same root. And they share something profbund: the root of medicine and meditation is the Latin niederi. which means "to cure." But the deep Indo-European etymological root is actually "to measure." Now, what does medicine liave to do with measuring, or for that matter, what does meditation have to do with measuring? Nothing, if you think of measurement as holding up an external standard and measuring how iong a tabie is or the volume of water in a bottle. But this is more the Platonic notion that everything has its own right inward measure. So medicine would be tbe restoration ofa human being's right inward measure througb surgery, drugs, and other medicai interventions. And what is meditation then? Meditation is the direct receiving of right inward measure— the measure of our thoughts, the measure of our emotions, the measure of our body sensations, and embracing aii that in awareness. It means to know right inward measure intimately through our own direct, first-person experiencing of it: to know tbe bodyscape, the soundscape. the mindscape, the breathscape, the beartscape. And you can only know that territory by cultivating intimacy with it. So meditation and medicine are actually linked at the hip very, very far back in the root definitions of these words. I think sometimes we would do better in medicine to teach medical students the meaning of words so they can keep in mind that this is a calling. Medicine is a magnificent enterprise and one of tbe greatest achiexements of human culture, and it is continually growing and changing. Science is continualy transforming medicine in little and big ways. And tbat includes the discoveries of neuroscience. and now, hopefully the "inner work" of meditative practices and their understandings of the mind and fhe body. All of this is contributing to changing medicine in our time. think, " \ o w I have to be completely aware at every single moment." But it's not about that. It's not about self-consciousness; it's about consciousness. Tbere are many interesting, technical questions about how to become more mindful, but I want to emphasize that becoming even a tiny bit more mindful is good. You do not have to be totally mindful at every hour of the day and night. That is merely an ideal, based in thought, which can become an impediment to understanding and motivation. If you make that into a goal, you will most likely hecome rapidiy discouraged. Such striving is not in the spirit of mindfulness at all. All we need to do is become a tiny bit more mindful in this moment. That can wind up having a profound effect on the quality of the next moment, and the adventure unfolds, just NEED TO KNOW MORE ABOUT THE SCIENCE OE COMPASSION, THE SCIENCE Of EMPATHY, THE SCIENCE OF ACCEPTANCE AS WELL AS THE ART OE COMPASSION, THE ART OE EMPATHY... AT: How critical is this to fixing our broken healthcare system? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: I agree with you that the healthcare system is broken. My friend and colleague, Dr. Ralph Snyderman, who just stepped do\i7i from his position as Chancellor of Duke University Medical Center, said when speaking about medicine that the chassis is broken and the wheels are falling off. The sysfem is broken, but fhe knowiedge base is not broken. The beauty of the Hippocratic oath is not broken: that is incredibly vital. We do not need to exaggerate fhe problems in medicine, but rather to remember that the system of medicine is not medicine. The more we can break our attachment to particular interest groups that keep medicine \'ery tightly constrained, the more effectively medicine can grow into the medicine of the 21st century, grounded in the most beautiful science, and in the most beautiful elements of the art of medicine that are known and can be scientificaily studied. From tbat point of view. I am not really worried about medicine because it is never going to run out of customers, and every person who works in medicine is going to at some point or other be a customer as well. That should give us pause to treat eacb patient as if he or she was our own parent or our own child. I think mindfulness. along with a lot of other things, has the potential to aid or catalyze the transformation of medicine into its larger self When I talk about becoming more mindful, people tend to 62 like learning to waik. There is a lot of falling on one's butt and on one's face. AfTERNATiVE THERAPIES. MAY/IUNE 2005. VOL 11, NO. 3 I am now one of several senior advisors to a group known Conversations wilh lun Kabat-Zinn, as the Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine (CAHCIM), which formed a number of years ago with eight medical schools that were doing cutting-edge work in the mind-body area of integrafive medicine on the research. education, or clinical front. Now the con.sortium is up to 27 medical centers and the n u m h e r is growing annually. Mindfulness is at the very heart of this enterprise and at the root of integrative medicine itself So this is anotber piece of evidence that a commitment to mindfulncss is growing within medicine and healthcare. The original idea was not just that engaged faculty would come together to explore the potential for transforming medicine, but that we vvould also involve our chancellors and deans and other people at the top levels of our institutions and expose them in the deepest of ways about what integrati\e medicine and mind-body medicine are ail about, not just conceptually butexperientially. The heart of this enterprise is not limited to a conceptual framework for educational reform and refining research directions and clinical practice. important as those agendas are. it has even more to with the orthogonal dimension of interiority that involves wakefniness. presence, comfort, silence, stillness, and the new dimensions of seeing and being, as well as tbe boundless creativity that can emerge out of the psyche of human heings througb self-examination and self-knowing. AT: Can you give us your insight on the mind-hody medicine field? Dr. Kahat-Zinn: You could say that this field of mind-body medicine, and the larger umbrella of integrative medicine, are in tbeir infancy. We are not talking about alternative medicine. We are not talking about complementary medicine. We are not talking about mind-body medicine, we are not talking about integrative medicine, we are not even talking about participatory medicine—we are really talking about good medicine, period. Good medicine is something tbat is always growing, a moving target. To some degree, we do have to live witb the dinosaur features of the past. but. at tbe same time, there is the possibility of us coming to our senses and waking up and fashioning a medicine tbat will serve us all. In a recent paper, we showed that people with psoriasis who meditate while receiving ultraviolet treatments heal at four times tbe rate of control subjects who get oniy the light. This results in the meditators needing fewer treatments, which translates to cost reduction. In another study, in collaboration with Dr. Richard Davidson of the Laboratory of Affective Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin, a clinical trial of MBSR in a work setting, we showed that people undergoing MBSR training showed shifts in the activation of certain regions of the prefrontal cortex, which is consistent with more effective handling of difficult emotions under stress and corresponding increases in immune responsivity compared with wait-list control subjects. We have anecdotal evidence from 25 years of clinicai practice in the Stress Reduction Clinic that peopie who participate in MBSR have fewer emergency' visits and Conversations with Ion Kah;U->!iiiii. I fewer hospitalizations or are discharged from the hospital faster—aii things that can he studied systematically. In fact, we are currentiy conducting a study looking at three diagnoses in terms of cost benefit of participating in the MBSR program. These are difficult studies to conduct, and there needs to be more of them. The Nationai Institutes of iieaith (NIH) heid a day-iong symposium in May 2004 called "Mindfuiness Meditation and iieaith." More than 500 people attended. As far as i know, it was a first for the Nii-I. At the end of tbe symposium, an NiH physician and researcher stood up and said. "Given the budget priorities. I propose that we rename the NIII the National Institutes of Disease." This was coming from somebody who had been working there his whoie career, i don't think that we need to get info poiemics about the NiH— it is one of the most incredible institutions on the planet; they are doing and supporting extraordinary work. But I think he was sa\ ing that the Nil 1 could devote more resources to investigating the nature of healing and health as opposed to the nature of disease. It is a matter of balancing resources and aiso contributing to envisioning what rational, 21st'Century medicine would look like, Presumabh', that would responsibly take the controversial elements of the mind-body connection into account as weil as its potential, as patients want to have more alternatives. The NIH in general, and The National Center for Complementary and Aiternative Medicine (NCCAM) in particuiar, have made great strides in putting a scientific foundation under otber forms of medicine and investigating them to gain a deeper understanding of the human organism and how it can he encouraged to maintain health across the entire life span. AT: What excites you the most about fhe future of mindfuiness in medicine? Dr. Kabat-Zinn: One thing that excites me is tbe huge interest among neuroscieniists in meditation and the papers that are coming out about it. Another is the growing work of the Mind and Life Institute, where i serve as a Board Member and ViceChair, We recently instituted what will be an annual summer research institute. We invite graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and faculty members in universities and research institutions around the world to come and train in a meditative enviroimient for one week with tbe faculty of the Mind and Life meetings. We engage in diaiogue with peopie from various contemplative traditions, long-term meditators and yogis, and have conversations across these discipline boundaries in ways that embody the deepest third-person investigative possibilities. And simultaneousiy, participants get a taste of the first-person dimension of direct meditative experience, because tbat direct first-person experience can inform the scientists" study designs, coilaborations, and decisions about what to work on in ways that will potentiaily extend the boundaries of neuroscience and good medicine way beyond where they are right now. That would be tremendousiy instrumental to aspects ofpsycholog}' that reaily have not been studied ALTERNATIVE THEIIAI'IES. MAY/|UNE 2005, VOL. 11. NO. 3 63 mucb until now. Compassion, for instance, is hardiy a subject of investigation in the psychological literature, but medicine is based on compassion. So we need to know more about the science of compassion, the science of empathy, the science of acceptance, as well as the art of compassion, tbe art of empathy, the art of acceptance, and for that matter, the potential of what ue might call wisdom fbr enhancing health and well-being, of both individuals and of the society as a whoie. the hody politic, you migiit say. Perhaps we are aii learning to draw effectively from the weil of the multiple dimensions of our human capacity fbr investigation and knowing, both inwardly and outwardly, inciuding from the the dimension of our not knowing, in ways that have integrity and kindness. This would allow us clinically to meet our patients where they are. out of the fullness of our being as well as with our clinical expertise, and thus optimize the potentiai for connection and healing and minimize the potentiai for ignoring whaf is most fundamentai in medicine, the sacred quality of the encounter itself what excites me. The imaginative approaches that are being taken and researched are truly inspiring, and bode weil for a more mindful and more heartful medicine and heaithcare in the fufure. These practices are now making their way into business, the legal profession, and education at all ieveis, from elementary school to graduate school, i find these developments hugely promising and see them as potentially transformative and healing of our society and its institutions, i am aiso hugely inspired by the work on so many fronts of my colieagues at the Center for Mindfulness at the UMass Medical Schooi, who, under the wise leadership of Dr. Saki Santorelii. my long-term colleague and friend, are offering, among other things, a rigorous certification trajectory for health professionais in MBSR. and who now host an annual conference on Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Medicine and Health Care that brings people to Worcester, Massachusetts, from around the world, to one of the most inspiring gathering of people committed to bringing mindfulness into the world that 1 have ever seen. And finally, the depth of the work of ciinicians and scientists around the country and around the worid engaged in MBSR. MBCT. and other mindfulness-based interventions is More information is available at: www.umassmed.edu/em and www.mindandlife.org M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in Psychology or Human Science v^ith a concentration in * Integrative Health Studies Study with pioneers of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Jeanne Achterberg, Lyn Freeman, Don Moss and Saybrook's outstanding faculty • Experience tbe power and convenience of Saybrook's individualized menfored distance study • Create your own unique program integrating your personal learning journey af tbe frontiers of CAM • fearn fhe skills and strategies to compete successfully for NIH research funding of CAM and mind-body topics • Work witb research faculfy exploring human energy fields, traditional bealing, imagery and distant healing intentionalify GRADUATE SCHOOL* RESEARCH CENTER WASC Accredited 877.729.2766 • www.saybrook.edu b4 ALTEKNATIVt THERAlMhS, MAY/JUNE 2005. VOL 11, NO, 3 ConversaiioTi.s with loii Kal)al-/iiin,