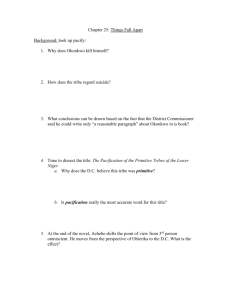

Humanizing the Dehumanized in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart Ester Ignacio-Tas 472887 Global Literatures Drs Carel Burghout HAN University of Applied Sciences December 2021 Humanizing the Dehumanized Humanizing the Dehumanized in: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart Chinua Achebe’s much acclaimed novel Things Fall Apart (1958) is one of the most canonized African novels. Doherty (2014) states that Things Fall Apart “is meant to challenge not simply the image of the African but the underlying principle, as Achebe would understand it, that Africa had no history, culture, or civilization until the arrival of the Europeans.” Indeed, African -Igbo- culture is widely explored in this novel, nonetheless Things Fall Apart is not mainly a novel about African culture and history but first and foremost a character-driven novel. It is not a story about the magical African man or the story of an uncomplicated native culture in which everything was peaceful. The colonial gaze (Shama, 2018), though present, does not give identity to the Africans. The storyline evolves around the inner thoughts and external actions of one main protagonist: Okonkwo, a leader in the Igbo-tribe whose ideas on masculinity are challenged within and outside of his culture. Okonkwo and his friend Obierika, who represents the voice of reason (Burghout, 2021), both argue against the notion of essentialism (Fanon, 1967) which reduces “the other” to a stereotype. Through their story they challenge the notion of hegemony for “the body of British texts all too frequently still acts as a touchstone of taste and value” (Ashcroft, 1989). Things Fall Apart quintessentially is a realistic novel about a struggling man that could have been set anywhere in the world. This is where it derives its power. First the broader context of the setting of Things Fall Apart needs to be addressed. The novel recuperates a version of Nigerian Igbo history just before the advent of the colonizer’s rule. It captures and dramatizes a crucial historical, psychological and philosophically charged moment, recreating and examining both Western colonialism and the end of African traditional ways (Wisker, 2007). The projection of Africa as a dark place with voiceless natives is disapproved by Achebe as one can read in his critique on Conrad “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1978). Things Fall Apart centres around Okwonko, who has his own voiced opinion what constitutes a man and maleness. Though a flawed character the story is built on the result of Okwonko’s own choices and actions: “Okwonko was well known throughout the nine villages and even beyond. His fame rested on solid personal achievements” (p. 3). In that same vein, in Igbo-society, in so far as Achebe chose to picture this society (Nnoromele, 2000, p. 148), individual achievement is highly regarded. Titles are earned and not inherited. This notion is stressed on the very first page of the novel. Okwonko, by his own achievement, first finds himself in the core of his society. By actions that do not coincide with expectations within his Igbocommunity, Okwonkwo’s place alters in that of one in the periphery. These actions point to the keyconcept of essentialism for Okwonko is clearly portrayed as a person. He is not ‘one of that group of savages’. He is defined as Okwonko, an individual within this Igbo-tribe. Further underpinning this notion are the various tribes within the novel. One does not read about a plethora of Nigerian tribes all 2 Humanizing the Dehumanized acting identically, but rather about small societies living by their own value system. Similar to any society, these diverse Igbo-tribes make rules to keep out people and to hold on to people. Within those societies individuals sometimes choose to adjust to the system and other times to oppose it. This then leads to the character of Obierika, Okonwkwo’s best friend in Things Fall Apart. Thoughts and actions of both characters can be linked to Yates’s The Second Coming, a poem Achebe refers to in the opening page of the novel. Yates’s poem talks about “the centre that cannot hold’ and about ‘a gyre’ – a funnel like structure that is widening and widening. When linked to Okwonko and Obierika, both have to deal with the tangibility of being confronted with one time-frame having ended – that of the original Igbo-tribe culture-, and a new timeframe - that of the British colonizers - which is emerging. Okwonko is in open revolt to this new timeframe and ‘grounds his teeth in disgust’ (p.151) for his tribesmen- to him- seem unable to act according to their tribe’s set of values when the sacred royal python/tribesmen is killed (p. 149, 150). Obierika on the other hand contemplates the white man’s actions and knows it is of no use to fight them for now their own Igbo-men have joined the Christian God (165-167). Okwonko sets his face like flint and fiercely clings to and acts out (p. 194) the truths he unswervingly holds. Okwonko, a man of action and anger kills the – white - head messenger, who to him represents all that is lost within his community. This then leads to Okwonko’s irreversible alienation from his own kinsmen (p. 194) whose response ‘Why did he do it?’ forecasts Okwonko’s suicide. It should be noted that Achebe does paint a vivid picture of the Igbo-society. Therefore Things Fall Apart is a novel with a clear cultural context. When the characters are examined in the light of this specific culture with its social customs, traditions and cultural milieu of a people characters and their actions are better understood. When the British colonizers arrive, the Umufoia people have to deal with what seems like a total imposition of one cultural, social and political structure upon another. It is only within this context Okwonko’s thoughts and actions are best understood. He realized that accepting the culture of the British colonizers would be done at the expense of the things that compromised his identity and defined his values. To further illustrate their differences Things Fall Apart ends with the colonial gaze. Okwonko kills himself which in Igbo-culture is ‘the unforgivable sin’ and therefore his own tribesmen cannot bury him. The reader then finds himself in the mind of the British Commissioner, who, in one paragraph, dismisses the life of Okonkwo (p. 197). Okwonko’s life, a life fully lived by a man who raised his voice, right or wrong, a man who made choices influenced by his culture and at the same time acted autonomously, is dehumanized by this Commissioner. In one page. No, in one paragraph. For ‘one must be firm in cutting out details’ (p. 197). In the course of this essay I have argued that the characters in Things Fall Apart are normal people and their events are real human events. By writing Things Fall Apart Achebe tried to break into the hegemony of English literary texts ‘which all too frequently acts as a touchstone of taste and value’ (Ashcroft, 1989). Achebe gave voice to a colonized human being. Okwonko. Okonkwo’s actions are 3 Humanizing the Dehumanized therefore an abberation and not necessarily a representation of the entire Igbo-culture. Okonkwo is someone who makes a choice to be the man he is based on his position within the traditional Igboculture and acts accordingly. By telling Okwonko’s story and not the colonizer’s version of the story, it is the narrator, and through him Achebe, who has humanized the dehumanized. References Achebe, C., (1958). Things Fall Apart. Pinguin. Adichie, C.N., (2008). The Headstrong Historian. The NewYorker. Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., & Tiffin, H. (2007). Post-colonial studies: The key concepts (2nd ed.) Routledge. Curry, T. (2021). Countries and their Tribes. Retrieved from https://www.everyculture.com/MaNi/Nigeria.html#ixzz7EZ5qsoHl. Nnoromele, P. C. (2000). The Plight of a Hero in Achebe s “Things Fall Apart.” College Literature, 27(2), 146–156. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25112519 Wisker, G. (2006). Key Concepts in Postcolonial Literature. Macmillan Learning 4