Chapter One Notes-Interpretation & Definition of Classical Mythology

advertisement

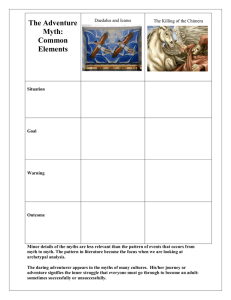

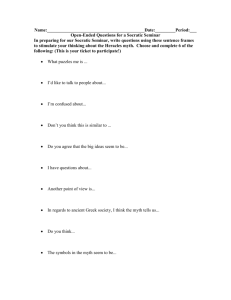

Chapter One What is Mythology? Mythology can be broken down into two parts, the first being Myth and the second -ology. Mythos- depending upon context, “word”, “speech”, “tale” or “story” logy- a suffix meaning the study of. The problem with defining mythology as one thing or the other is that there has been a difficulty reaching consensus in what should or should not be considered a myth. This word has been used improperly to describe urban legends, something difficult to believe or simply as a way to dismiss something one disagrees with as untrue. (see Mythbusters). Because of this pollution, in addition to the issue of “story” being far too general, there are several terms used to further classify what exactly a story should be classified as. Myth- Not a comprehensive term for all stories but only for those primarily concerned with the gods and their relations with mortals. Think of the Theogony a description of the genealogy of Gods Saga or Legend- A story containing a kernel of historical truth, despite later fictional accretions. Think of Johnny Appleseed or Troy. Folktale- A story, usually of oral origin, that contains elements of the fantastic, often in the pattern of the adventure of a hero or heroine. Its main function is entertainment, but it can also educate with all sorts of insights. Under this rubric may be classed fairy tales, which are full of supernatural beings and magic and provide a more pointed moral content. Rarely in Greek or Roman Mythology does any tale fall so neatly into anyone grouping or description. Lets not group anyone into one box. For example what would Beowulf be? Could there have been a prince of Norway visiting Denmark who vanquished a dehumanized foe? Could it all have been a Folktale, crafted throughout the ages? and more so where do the ideas for Folktales come from? They are stories from life that are enhanced, chopped up, and made into something new. So everything is based in reality really.... Myth and Truth- Most commonly myth is associated with something fictional, outrageous or just plain silly. Like crocodiles in NYC sewers...(they would freeze...). Myth and Truth cannot be used in the way that Science and Truth are. Myth is an abstract concept that acts as more of a negative or a time now gone. It encapsulates to a degree what was and how ideas were shaped. Myths are not truth in themselves but a tool that we use to extract truth from a time unfortunately very much wiped away. Myth and Religion- The study of myth is very much the same as the study of religions, religious beliefs and religious rituals. They describe a time and place that very much treated these beliefs as religions. There was belief that Neptune ruled over the sea, when one died they were sent to meet Hades and that Zeus was born of Rhea who was born of the Earth/Gaia. Euhemerism- an attempt to rationalize classical mythology, attributed to Euhemerus. Claimed Gods were the great men and kings of old. Consider these the Rationalists, the school of thought is trying to Rationalize a cause for mythology Allegory- A sustained metaphor. The allegorical approach to mythology is to see myths as an extension and interweaving of various allegories. (Think of how Moses told people that god had weird dietary restrictions for them so that they would stop getting salmonella from fish.) Allegorical Nature Myths- For max Muller in the nineteenth century, myths are to defined as explanations of the meteorological and cosmological phenomena. Muller’s theory is too limited. Some Greek and Roman Myths, but by no means all, are indeed about nature. Most likely there is a little of each, as the case with most things. Max Muller (1823-1900)● Believed myths were allegorical in nature ● Believed most belief systems came back to a Solar mythology ● Many/most beliefs came back to a battle of Light VS Darkness ● Believed myth to descend from the disease of language. Figurative language specifically in which over time flowery, poetic language was no longer seen as such and was taken far too literally. Everything is a metaphor and everyone is an idiot. Battle of Light VS Darkness- Muller believed that early man is preoccupied with the dichotomy between light and darkness. That the battle between the two, between night and day, hot and cold, winter and summer, perpetuates through all myth. This is widely regarded as oversimplified and generally a bad idea. Sir James Frazer (1854-1941) ● The Golden Bough is his most famous work ● ● ● Myth was an encoded ritual Cambridge school of thinkers, AKA The Ritualists. Reductionist and dismissive. Grove of Nemi- The grove of Nemi was a grove of worship toward the goddess Diana and was tended to by a Priest-King. You became Priest-King by escaping slavery and then murdering the current Priest-King. What is the Golden Bough?- One of the episodic tales written in the epic Aeneid, book VI, by the Roman poet Virgil (70-19 BC), which narrates the adventures of the Trojan hero Aeneas after the Trojan War. What Frazer believes is that this narrative is replicated across all cultures in one way or the other. Think of Apocalypse Now when Martin Sheen almost replaces the previous Priest-King Kurtz. This view is dismissive and merely states that yes humans are cut from the same cloth but ignores the details that are added later by the seamstress. Myth and Psychology- The theories of Freud and his student Jung are fundamental and far reaching in their influence. Although they are continually challenged they provide the tools for a profound, introspective interpretation of mythology. Freud- Centering on psychosexual development, the interpretation of dreams, the theory of the unconscious, and the Oedipus Complex, Freud’s analysis has deeply influenced both modern day culture and the study of these myths, granting new insight into why the myths come together in the way they do, what that might mean for those who heard them and why they may have been created in the first place. Oedipus Complex- Developed in a work that attempts to explain the particularly uneasy and timeless dramatic import of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannos, the theory of the Oedipus complex holds that a male child’s first sexual feelings are directed towards the mother with the concomitant arousal of jealousy and hatred towards the rival for those affections, the father. The female version has been identified by Carl Jung as the Electra complex, in which the daughter's love is towards the father with hatred of the mother. Freud saw dreams as the expression of repressed or concealed desires. The “dream-work” of sleep has three basic functions: to condense elements; to displace elements, by altering them; and to represent elements through symbols. In this regard, symbols of dreams can work in much the same way as the symbols of myths. Carl Jung ● Collective Unconscious Jung went beyond the connection of myths and dreams with the individual to interpret myths as the projection of what he called the “collective unconscious,” that is, the revelation of the continuing psychic tendencies of a society. Jung made an important distinction between the personal unconscious, concerning matters of an individual’s own life, and the collective unconscious, embracing political and social questions of the group. ● Archetypes Myths contain images or “archetypes,” according to Jung, traditional expressions of collective dreams, developed over thousands of years, of symbols upon which the society as a whole has come to depend. These archetypes, revealed in peoples' tales, establish patterns of behavior that can serve as exemplars, as when we note that the lives of many heroes and heroines share a remarkable number of similar features that can be identified as worthy of emulation. Similarly, other kinds of concept are to be classified among the many and varied types of Jungian archetype embedded in our mythic heritage, e.g., the great earth mother, the supreme sky-god, the wise old man, the idealistic young lover. THE STRUCTURALISTS ● Claude Lévi-Strauss The structuralist Claude Lévi-Strauss sees myth as mode of communication in which the structure or interrelationships between the parts, rather than the individual elements alone, establish meaning. In the belief that human behavior is patterned and that the human mind has a binary structure, Lévi-Strauss argues that the creations of the mind, including myths in particular, partake of a binary structure. One of the principal aims of myth is to negotiate between binary pairs or pairs of opposites (e.g., raw/cooked, life/death, hunter/hunted, nature/culture, male/female, inside/outside), and to resolve them. Since the meaning of a myth is “coded” in its structure, all versions of a myth have the capacity to be equally valid. ● Vladimir Propp Vladimir Propp, a Russian folklorist, developed the structuralist approach to myth before Lévi-Strauss by analyzing a select group of tales with similar features and isolating the recurrent, linear structure manifest in them. In this pattern Propp identified 31 functions or units of action, which have been termed motifemes. All these motifemes need not be present in one tale, but those that are will always appear in the same sequential order. This comparative approach to mythology has proven useful in analyzing a wide range of seemingly dissimilar tales across many different cultures, which satisfy the sequential pattern, such as those about a hero’s quest or, in particular, the thematic details concerning his mother and his birth, which Walter Burkert has broken down into five motifemes: ● The girl leaves home. ● The girl is secluded. ● She becomes pregnant by god. ● She suffers. ● She is rescued and gives birth to a son. The understanding of classical mythology can be made both easier and more purposeful if underlying structures are perceived and arranged logically. The recognition that these patterns are common to stories told throughout the world is also most helpful for the study of comparative mythology. ● Walter Burkert Walter Burkert has attempted a synthesis of various theories about the nature of myths, most important being those having a structuralist and a historical point of view. To Burkert, of great significance is the fact that a myth has a “historical dimension.” In its development a myth may incorporate “successive layers” of narrative, each of which has addressed the particular needs of a particular storyteller with a particular audience in a particular time. To support his synthesis, he has developed four theses: ● Myth belongs to the more general class of traditional tales. ● The identity of a traditional tale is to be found in a structure of sense within the tale itself. ● Tale structures, as a sequence of motifemes, are founded on basic biological or cultural programs of actions. ● Myth is a traditional tale with secondary, partial reference to something of collective importance. COMPARATIVE STUDY AND CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY Oral and Literary Myth. Many insist that a true myth must be oral and anonymous. The tales told in primitive societies are the only true myths, pristine, timeless, and profound. The written word brings contamination and specific authorship. We disagree with such a narrow definition of mythology. Myth need not be just a story told orally. It can be danced, painted, and enacted, and this is, in fact, what primitive people do. Myth is no less a literary than an oral form. Despite the successive layers that have been grafted onto Greek and Roman stories and their crystallization in literary works of the highest sophistication, comparative mythologists have been able to isolate the fundamental characteristics that classical myths share with other mythologies, both oral and literate. Joseph Campbell. A comparative mythologist, perhaps best known for his series of PBS interviews with Bill Moyers, Campbell did much to popularize the comparative approach to mythology. Though his attention was largely devoted to myths from other traditions, many of his observations, as he himself was well aware, can be profitably applied to classical mythology. Feminism, Homosexuality, and Mythology ● Feminism Feminist critical theory focuses upon the psychological and social situation of female characters in terms of the binary nature of human beings, especially in the opposition (or complementary relationship) of female and male. Feminist scholars have used the critical methods of deconstruction to interpret myths from their points of view about political, social, and sexual conflict between men and women in the ancient and modern world. Their conclusions are sometimes determined by controversial reconstructions of two major topics: the treatment and position of women in ancient Greece and the theme of rape. ● Women in Greek Society Here are four out of many observations that could be made about the treatment and position of women in Greek society: ● Women were citizens of their communities, unlike noncitizens and slaves—a very meaningful distinction. They did not have the right to vote. No woman anywhere won this democratic right until 1920. ● The role of women in religious rituals was fundamental; and they participated in many festivals of their own, from which men were excluded. ● A woman’s education was dependent on her future role in society, her status or class, and her individual needs (as was that of a man). ● The cloistered, illiterate, and oppressed creatures often adduced as representative of the status of women in antiquity are at variance with the testimony of all the sources: literary, artistic, and archaeological. ● The Theme of Rape What are we today to make of classical myths about ardent pursuit and amorous conquest? Are they love stories or are they all, in the end, horrifying tales of victimization and rape? The Greeks and the Romans were obsessed with the consequences of blinding passion, usually evoked by Aphrodite, Eros, or Dionysus and his satyrs, and of equally compulsive chastity, epitomized by a ruthless Artemis or one of her nymphs. The man usually, but by no means always, defines lust and the woman chastity. Often there is no real distinction between the love, abduction, or rape of a woman by a man and of a man by a woman. Stories about abduction, so varied in treatment and content, have many deeper meanings embedded in them, e.g., social, psychological, and very often religious. The supreme god Zeus may single out a chosen woman to be the mother of a divine child for a grand purpose, and the woman may or may not be overjoyed. Thus the very same tale may embody themes of victimization, sexual love, and spiritual salvation, one or all of these conflicting eternal issues or more. Everything depends on the artist and the person responding to the work of art: each individual’s gender, sexual orientation, age, experience or experiences, politics, and religion. There is no one “correct” interpretation, just as there is no one “correct” definition of a myth. These stories from antiquity to the present have evoked so wide a range of responses that they should not be subjected to a criticism reduced to a simple harangue about the mistreatment of women—or of men. Romantic critics in the past sometimes chose not to see the rape; many today choose to see nothing else. ● Homosexuality Homosexuality was accepted and accommodated as a part of life, certainly in Athens. There were no prevailing hostile religious views to condemn it as a sin. Yet there were serious moral codes of behavior, mostly unwritten, that had to be followed to confer respectability upon homosexual relationships and individuals who were homosexual. Homosexuality may be found as a major theme in some stories, e.g., Zeus and Ganymede, Poseidon and Pelops, Apollo and Hyacinthus, Apollo and Cyparissus, Achilles and Patroclus, Orestes and Pylades, and Nisus and Euryalus. Thus Greek and Roman mythology embraces beautifully the themes of homosexuality (and bisexuality) but, overall, it reflects the dominant concerns of a heterosexual society from the Olympian family on down. Female homosexuality in Greek and Roman society and mythology is as important a theme as male homosexuality but it is not nearly as visible. Sappho, a lyric poetess from the island of Lesbos (sixth century B.C.), perhaps offers the most overt evidence. SOME CONCLUSIONS AND A DEFINITION OF CLASSICAL MYTH We have provided a representative (and by no means exhaustive) sampling of influential definitions and interpretations that can be brought to bear on classical mythology. It should be remembered that no one theory suffices for a deep appreciation of the power and impact of all myths. Certainly the panorama of classical mythology requires an arsenal of critical approaches. Let us end with a definition of classical mythology that emphasizes its eternal qualities, which have assured a miraculous afterlife. It may be that a sensitive study of the subsequent art, literature, drama, music, dance, and film, inspired by Greek and Roman themes and created by genius, offers the most worthwhile interpretative insights of all. A classical myth is a story that, through its classical form, has attained a kind of immortality because its inherent archetypal beauty, profundity, and power have inspired rewarding renewal and transformation by successive generations.