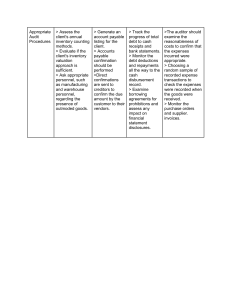

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359861452 Accounting All-in-One For Dummies Book · April 2022 CITATIONS READS 0 222 1 author: Imtiyaz Oxford Academy of Athens 6 PUBLICATIONS 16 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: dictionary arabic View project All content following this page was uploaded by Imtiyaz Oxford on 10 April 2022. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Accounting ALL-IN-ONE Accounting ALL-IN-ONE by Ken Boyd, Lita Epstein, Mark P. Holtzman, Frimette Kass-Shraibman, Maire Loughran, Vijay S. Sampath, John A. Tracy, Tage C. Tracy, and Jill Gilbert Welytok Accounting All-In-One For Dummies® Published by: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, www.wiley.com Copyright © 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/ permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, Dummies.com, Making Everything Easier, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc., and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor m ­ entioned in this book. LIMIT OF LIABILITY/DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTY: WHILE THE PUBLISHER AND AUTHOR HAVE USED THEIR BEST EFFORTS IN PREPARING THIS BOOK, THEY MAKE NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE CONTENTS OF THIS BOOK AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. NO WARRANTY MAY BE CREATED OR EXTENDED BY SALES REPRESENTATIVES OR WRITTEN SALES MATERIALS. THE ADVISE AND STRATEGIES CONTAINED HEREIN MAY NOT BE SUITABLE FOR YOUR SITUATION. YOU SHOULD CONSULT WITH A PROFESSIONAL WHERE APPROPRIATE. NEITHER THE PUBLISHER NOR THE AUTHOR SHALL BE LIABLE FOR DAMAGES ARISING HEREFROM. For general information on our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 877-762-2974, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3993, or fax 317-572-4002. For technical support, please visit www. wiley.com/techsupport. Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print v ­ ersions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com. Library of Congress Control Number: 2013954224 ISBN 978-1-118-75800-7 (pbk); ISBN 978-1-118-81365-2 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-81374-4 (ebk) Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents at a Glance Introduction................................................................. 1 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System.................... 5 Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics............................................ 7 Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts................ 17 Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers.............................................................. 27 Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method................................................................ 43 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions................. 53 Chapter 1: Keeping the Books......................................................................................... 55 Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases....................................................................................... 67 Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales...................................................................................... 79 Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits................................................ 91 Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes.................................................. 111 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries...................... 123 Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets........................................................................... 125 Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest................................................................... 137 Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash.................................................................................. 147 Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries................................. 157 Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy............................................................................ 175 Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books.................................................................................... 185 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets......................................................... 195 Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards..................................................... 197 Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit........................ 207 Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet's Asset Section........................................... 223 Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section.................... 239 Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equit y Section of the Balance Sheet........... 253 Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet................................ 265 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements......... 279 Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation........................ 281 Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity........................................ 291 Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements................................................................. 305 Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures........................................... 321 Chapter 5: Studying the Repor t to the Shareholders................................................. 335 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business.... 347 Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business..................................................................... 349 Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business............................................... 361 Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash............................................ 371 Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line.......................................................... 383 Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting..................................................... 395 Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations......................................................... 407 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions................ 419 Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing............................................................ 421 Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing........................................................... 437 Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin................................................................. 453 Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis....................................... 469 Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions................................................................ 487 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions................................................... 497 Chapter 1: Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue.............................. 499 Chapter 2: Exploring Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions........................................... 507 Chapter 3: Answering the Question: Should I Buy That?........................................... 519 Chapter 4: Knowing When to Use Debt to Finance Your Business.......................... 533 Chapter 5: Interpreting Your Financial Results as a Manager.................................. 547 Book IX: Auditing and Detecting Financial Fraud........ 555 Chapter 1: Mulling Over Sarbanes-Oxley Regulation................................................. 557 Chapter 2: Preventing Cash Losses from Embezzlement and Fraud....................... 571 Chapter 3: Assessing Audit Risk................................................................................... 585 Chapter 4: Collecting and Documenting Audit Evidence........................................... 607 Chapter 5: Auditing a Client’s Internal Controls......................................................... 625 Chapter 6: Getting to Know the Most Common Fraud Schemes.............................. 647 Chapter 7: Cooked Books: Finding Financial Statement Fraud................................. 663 Index....................................................................... 673 Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................. 1 About This Book............................................................................................... 1 Foolish Assumptions........................................................................................ 2 Icons Used in This Book.................................................................................. 2 Beyond the Book.............................................................................................. 3 Where to Go from Here.................................................................................... 3 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System.................... 5 Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics . . . . . . . . . 7 Knowing What Bookkeeping and Accounting Are All About...................... 8 Distinguishing between bookkeeping and accounting...................... 8 Taking a panoramic view of bookkeeping and accounting............... 9 Wrapping Your Brain around the Accounting Cycle................................. 10 Working the Fundamental Accounting Equation........................................ 14 Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 Getting to Know the Chart of Accounts....................................................... 17 Connecting the chart of accounts to financial statements.............. 18 Organizing the accounts...................................................................... 18 Balancing transactions......................................................................... 19 Setting Up Your Chart of Accounts.............................................................. 20 Mulling Over Debits versus Credits............................................................. 21 Understanding Double-Entry Accounting.................................................... 22 Revisiting the balance sheet equation............................................... 22 Recording journal entries.................................................................... 22 Figuring out a complex journal entry................................................. 24 Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 Keeping a Journal........................................................................................... 27 Using journals to record cash transactions...................................... 28 Recording accrual transactions.......................................................... 31 Exploring other journals...................................................................... 33 Checking out examples of common journal entries......................... 35 Bringing It All Together in the Ledger......................................................... 37 Realizing what a ledger is.................................................................... 37 Posting to the ledgers.......................................................................... 38 viii Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Viewing an example of a general ledger............................................. 38 Recognizing the purpose of the trial balance................................... 39 Putting Accounting Software to Work for You............................................ 40 Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43 Distinguishing between Cash and Accrual Basis........................................ 43 The cash basis....................................................................................... 44 The accrual basis.................................................................................. 45 Sorting through Standards for Other Types of Accounting...................... 46 Managerial accounting......................................................................... 47 Not-for-profit accounting..................................................................... 47 Governmental accounting................................................................... 48 International accounting...................................................................... 49 Considering the Conceptual Framework of Financial Accounting........... 49 The objective of financial reporting................................................... 50 Characteristics of accounting information........................................ 50 Elements of the financial statements................................................. 51 Financial statement measurements.................................................... 52 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions.................. 53 Chapter 1: Keeping the Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55 Analyzing the Effect of Business Transactions........................................... 55 Revisiting the fundamental accounting equation............................. 56 Getting familiar with accounts............................................................ 56 Defining debits and credits.................................................................. 57 Knowing more about the transaction methodology........................ 57 Managing Your Bookkeeping and Accounting System.............................. 58 Categorizing your financial information: The chart of accounts......................................................................................... 58 Standardizing source document forms and processing procedures............................................................. 59 Hiring competent personnel................................................................ 60 Enforcing strong internal controls..................................................... 62 Wrapping Up with End-of-Period Procedures............................................. 63 Tidying up the books............................................................................ 63 Leaving good audit trails..................................................................... 64 Staying alert for unusual events and developments........................ 64 Designing truly useful reports for managers..................................... 65 Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67 Keeping Track of Inventory........................................................................... 68 Entering initial cost.............................................................................. 69 Managing inventory and its value....................................................... 71 Table of Contents Buying and Monitoring Supplies................................................................... 75 Staying on Top of Your Bills.......................................................................... 76 Segregating duties to prevent theft.................................................... 76 Taking advantage of discounts........................................................... 77 Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79 Collecting on Cash Sales................................................................................ 79 Discovering the value of sales receipts............................................. 80 Recording cash transactions in the books........................................ 81 Selling on Credit.............................................................................................. 82 Deciding whether to offer store credit............................................... 82 Recording store credit transactions in the books............................ 83 Proving Out the Cash Register...................................................................... 85 Tracking Sales Discounts............................................................................... 86 Recording Sales Returns and Allowances................................................... 87 Monitoring Accounts Receivable.................................................................. 89 Accepting Your Losses.................................................................................. 89 Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . 91 Staffing Your Business................................................................................... 91 Completing government forms........................................................... 92 Picking pay periods.............................................................................. 96 Determining wage and salary types................................................... 97 Collecting Employee Taxes........................................................................... 98 Sorting out Social Security tax............................................................ 98 Making sense of Medicare tax............................................................. 98 Figuring out federal withholding tax.................................................. 99 Settling up state and local w­ithholding taxes................................. 100 Determining Net Pay.................................................................................... 100 Surveying Your Benefits Options............................................................... 101 Tax-exempt benefits........................................................................... 101 Taxable benefits.................................................................................. 102 Dealing with cafeteria plans.............................................................. 102 Preparing Payroll and Posting It in the Books.......................................... 103 Calculating payroll for hourly employees....................................... 103 Doling out funds to salaried employees.......................................... 104 Totaling up for commission checks................................................. 104 Putting it together to prepare payroll.............................................. 106 Depositing Employee Taxes........................................................................ 107 Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111 Paying Employer Taxes on Social Security and Medicare...................... 111 Filing Form 941.................................................................................... 112 Knowing how often to file.................................................................. 113 ix x Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Completing Unemployment Reports and Paying Unemployment Taxes............................................................................... 113 How states calculate the FUTA tax rate........................................... 114 Calculating FUTA tax.......................................................................... 114 Filing and paying unemployment taxes to state governments..... 118 Carrying Workers’ Compensation Insurance............................................ 118 Maintaining Employee Records.................................................................. 120 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries....................... 123 Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125 Defining Depreciation................................................................................... 125 Knowing what you can and can’t depreciate.................................. 126 Figuring out the useful life of a fixed asset...................................... 127 Delving into cost basis....................................................................... 128 Evaluating Your Depreciation Options...................................................... 128 Walking through the straight-line method...................................... 130 Accelerating by using declining balance......................................... 130 Calculating sum-of-the-years’-digits................................................. 132 Using the units-of-production method............................................. 133 Seeing how the methods compare................................................... 133 Figuring partial year depreciation.................................................... 135 Tackling Taxes and Depreciation............................................................... 135 Section 179........................................................................................... 136 MACRS.................................................................................................. 136 Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 Deciphering Types of Interest..................................................................... 137 Simple interest.................................................................................... 138 Compound interest............................................................................. 138 Handling Interest Income............................................................................ 139 Delving into Loans and Interest Expenses................................................ 140 Short-term debt................................................................................... 140 Long-term debt.................................................................................... 143 Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 147 Why Prove Out the Cash?............................................................................ 147 Making Sure Ending Cash Is Right.............................................................. 148 Closing the Cash Journals........................................................................... 150 Finalizing cash receipts...................................................................... 150 Finalizing cash outlays....................................................................... 154 Using a Temporary Posting Journal........................................................... 155 Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries . . . . 157 Reconciling Bank Accounts......................................................................... 157 Tracking down reconciling items..................................................... 159 Using a computerized system........................................................... 160 Table of Contents Posting Adjustments and Corrections....................................................... 161 Prepping to Close: Checking for Accuracy and Tallying Things Up................................................................................................... 162 Paying attention to initial transaction details................................. 162 Summarizing journal entries............................................................. 163 Analyzing summary results............................................................... 167 Planning for cash flow........................................................................ 168 Posting to the General Ledger.................................................................... 168 Checking Out Computerized Journal Records.......................................... 169 Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175 Working with a Trial Balance...................................................................... 175 Conducting your trial balance........................................................... 176 Dealing with trial balance errors...................................................... 178 Testing Your Balance by Using Computerized Accounting Systems..... 179 Developing a Financial Statement Worksheet.......................................... 181 Replacing Worksheets with Computerized Reports................................ 183 Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185 Adjusting All the Right Areas...................................................................... 185 Depreciating assets............................................................................ 187 Allocating prepaid expenses............................................................. 188 Counting inventory............................................................................. 189 Allowing for bad debts....................................................................... 190 Recognizing unpaid salaries and wages........................................... 193 Testing an Adjusted Trial Balance............................................................. 194 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets................................................... 195 Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 Exploring the Origins of Accounting Standards....................................... 198 Recognizing the Role of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA)................................................................................ 199 Tying together regulators for audits of publicly traded companies........................................................................... 199 ASB audit and attestation standards................................................ 200 AICPA Code of Professional Conduct............................................... 201 Checking Out the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)...... 202 Getting to Know the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)........ 203 Understanding generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP)........................................................................... 204 Looking online for FASB standards.................................................. 205 Pick a standard: Domestic or international..................................... 205 xi xii Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 207 Understanding the Nature of Profit............................................................ 207 Choosing the Income Statement Format................................................... 208 Deciding What to Disclose in the Income Statement............................... 210 Considering expense disclosure....................................................... 210 Presenting the right amount of expense information.................... 210 Examining How Sales and Expenses Change Assets and Liabilities............................................................................................ 211 Sizing up a business’s financial condition....................................... 211 Noting how accounting transactions affect the income statement and balance sheet......................................................... 212 Considering the Diverse Financial Effects of Making a Profit................. 214 Introducing T-accounts...................................................................... 214 Combining activity into one journal entry...................................... 215 Explaining additional transactions related to profit...................... 216 Reporting Extraordinary Gains and Losses.............................................. 217 Segregating the income statement................................................... 217 Considering business disruptions.................................................... 217 Questioning whether activity is truly unusual................................ 219 Correcting Common Misconceptions about Profit.................................. 220 Clearing up profit misconceptions................................................... 220 Comparing to industry standards.................................................... 221 Waving the red flag when you see revenue and credit sales increase.................................................................................. 221 Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section . . . . . . . . . 223 Homing in on Historic Cost......................................................................... 224 Discovering What Makes an Asset Current............................................... 224 Cash...................................................................................................... 224 Short-term investments..................................................................... 226 Accounts receivable........................................................................... 227 Notes receivable................................................................................. 230 Inventory.............................................................................................. 230 Prepaid expenses................................................................................ 232 Keeping Track of Noncurrent (Long-Term) Assets.................................. 232 Meeting the tangibles: Property, plant, and equipment (PP&E)................................................................... 233 Investigating intangible assets.......................................................... 235 Exploring the Asset Section of the Balance Sheet.................................... 237 Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239 Seeing How Businesses Account for Liabilities........................................ 239 Keeping Current Liabilities under Control................................................ 241 Accounts payable............................................................................... 242 Payroll and taxes................................................................................ 243 Table of Contents Unearned revenue.............................................................................. 244 Other short-term liabilities................................................................ 244 Planning for Long-Term Obligations.......................................................... 246 Financing asset purchases with debt versus equity...................... 247 Managing long-term debt................................................................... 247 Anticipating contingent liabilities..................................................... 248 Accounting for Bond Issuances.................................................................. 249 Mulling over bond basics................................................................... 249 Examining sample bond transactions.............................................. 250 Journaling bond transactions........................................................... 251 Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equit y Section of the Balance Sheet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 253 Understanding How Owner Equity Varies among Business Entities....................................................................................... 253 Sole proprietorship............................................................................ 253 Partnership.......................................................................................... 254 Corporation......................................................................................... 255 Distinguishing between Two Types of Capital Stock............................... 255 Preferred stock.................................................................................... 255 Common stock.................................................................................... 256 Recording stock transactions on the balance sheet...................... 256 Defining Paid-In Capital................................................................................ 257 Recording Retained Earnings...................................................................... 258 Spotting Reductions to Stockholders’ Equity........................................... 258 Paying dividends................................................................................. 259 Buying back shares: Treasury stock................................................ 261 Exploring Stock Splits.................................................................................. 261 Computing Earnings per Share................................................................... 262 Simple capital structure..................................................................... 262 Complex capital structure................................................................. 263 Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet . . . . 265 Rejoining the Income Statement and Balance Sheet................................ 266 Seeing connections between accounts............................................ 266 Using transactions to explain the connections............................... 267 Introducing Operating Ratios...................................................................... 269 Comparing expected with actual operating ratios......................... 269 Generating balance sheet amounts by using ratios....................... 270 Adding Fixed Assets, Depreciation, and Owners’ Equity........................ 273 Dealing with fixed assets and depreciation..................................... 273 Tacking on owners’ equity................................................................ 275 Completing the Balance Sheet with Debt.................................................. 276 Going over the debt section of the balance sheet.......................... 276 Tying in the new equity section........................................................ 277 xiii xiv Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements.......... 279 Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 281 Clarifying the Values of Assets in Balance Sheets.................................... 281 Considering options for balance sheet ­valuation........................... 282 Comparing two balance sheet valuations........................................ 283 Introducing Business Valuation.................................................................. 285 Grasping the practical applications of business valuations......... 285 Considering a CVA designation......................................................... 286 Comparing Business Valuation Methods.................................................. 287 Replacing assets: Replacement value.............................................. 287 Using future earnings and cash flow................................................ 288 Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity . . . . . . . . . 291 Understanding the Difference between Cash and Profit......................... 291 Seeing how noncash transactions affect profit............................... 292 Distinguishing costs from expenses................................................. 292 Realizing the Purpose of the Statement of Cash Flows............................ 293 Walking through the Cash Flow Sections.................................................. 294 Figuring cash operating results........................................................ 295 Showing cash investing transactions............................................... 297 Accounting for financing activities................................................... 298 Recognizing Methods for Preparing the Statement of Cash Flows........ 299 Using the direct method.................................................................... 301 Starting indirectly with net income.................................................. 302 Interpreting the Statement of Cash Flows................................................. 303 Looking Quickly at the Statement of Changes in Stockholders Equity............................................................................. 304 Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 305 Judging Solvency and Liquidity.................................................................. 305 Understanding the risks of late payments....................................... 306 Recognizing current assets and liabilities....................................... 306 Brushing up on current and quick ratios........................................ 308 Understanding That Transactions Drive the Balance Sheet................... 310 Analyzing three types of balance sheet transactions.................... 310 Reviewing changes in balance sheet accounts............................... 311 Measuring Profitability................................................................................ 312 Understanding trend analysis........................................................... 313 Focusing on return on investment................................................... 314 Homing in on return on equity.......................................................... 315 Exploring Activity Measures....................................................................... 315 Accounts receivable turnover........................................................... 316 Inventory turnover............................................................................. 317 Table of Contents Comparing Horizontal and Vertical Analysis............................................ 317 Using horizontal analysis................................................................... 318 Implementing vertical analysis......................................................... 319 Using Common Size Financial Statements................................................. 320 Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures . . . . . . . . . . 321 Realizing How Corporations Should Govern Themselves....................... 321 Identifying Corporate Characteristics....................................................... 322 Reviewing Common Explanatory Notes.................................................... 324 Leveling the playing field among financial statements.................. 324 Explaining significant accounting policies...................................... 325 Looking for important event disclosures........................................ 328 Putting the Onus on the Preparer.............................................................. 332 Chapter 5: Studying the Repor t to the Shareholders . . . . . . . . . . . . . 335 Why Private and Public Companies Treat Annual Reports Differently.................................................................................................. 336 Fulfilling Three Purposes............................................................................. 337 Serving a marketing and PR function............................................... 337 Stating financial performance and goals.......................................... 337 Meeting regulatory requirements..................................................... 338 Reading the Annual Report to Shareholders............................................ 338 Meeting the chair of the board of directors.................................... 339 Highlighting key financial data.......................................................... 339 Touting company achievements....................................................... 341 Looking into the future...................................................................... 341 Getting to know key management and board members................ 342 Walking through Form 10-K......................................................................... 342 Facing page: Identifying the affected company............................... 343 Part I: Finding out more about the registrant................................. 343 Part II: Revealing the company’s financial performance............... 343 Part III: Identifying management and corporate governance........ 345 Part IV: Exhibits, financial statement schedules, and signature........................................................................................... 346 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business..... 347 Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 349 Securing Capital: Starting with Owners..................................................... 349 Contrasting two sources of equity................................................... 350 Leveraging equity capital with debt................................................. 352 Recognizing the Legal Roots of Business Entities.................................... 353 Incorporating a Business............................................................................. 354 Issuing stock shares........................................................................... 355 Offering different classes of stock shares........................................ 355 xv xvi Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Determining market value of stock shares...................................... 357 Keeping alert for dilution of share value......................................... 358 Recognizing conflicts between stockholders and managers........ 360 Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business . . . . . . . . . . . . 361 Differentiating between Partnerships and Limited Liability Companies.................................................................................. 361 Partnerships........................................................................................ 362 Limited liability company (LLC)....................................................... 363 Limiting liability: Professional corporations and LLPs.................. 363 Understanding how partnerships and LLCs distribute profits..... 364 Going It Alone: Sole Proprietorships.......................................................... 365 Describing a sole proprietorship...................................................... 365 Understanding liability and financial reporting.............................. 365 Choosing the Right Legal Structure for Income Tax................................ 366 C corporations.................................................................................... 366 S corporations..................................................................................... 368 Partnerships and LLCs....................................................................... 369 Summing up the legal structure issue.............................................. 370 Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash . . . . . . . . . . 371 Outlining the Basic Business Plan.............................................................. 371 The executive summary..................................................................... 372 The market assessment..................................................................... 373 The operational overview.................................................................. 374 The financial summary: Performance and required capital.......... 374 Developing a Business Plan......................................................................... 375 Recognizing the evolution of business plans: BOTE, WAG, and SWAG......................................................................................... 375 Getting the process going.................................................................. 377 Analyzing and streamlining information with SWOT and KISS..... 378 Incorporating Third-Party Information into Your Plan............................ 380 Gathering the info............................................................................... 381 Riding the CART concept: Complete, ­accurate, reliable, and timely......................................................................... 381 Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 383 Brushing Up on Budgeting Basics.............................................................. 383 Meeting the master budget................................................................ 384 Understanding key budgeting concepts.......................................... 384 Planning strategically......................................................................... 385 Recognizing Factors That Impact Your Budgeting Process.................... 385 Experience counts.............................................................................. 386 Timing is everything........................................................................... 386 People get you headed in the right ­direction.................................. 387 Sales projections pay off.................................................................... 387 The Nuts and Bolts of Budgeting................................................................ 388 Understanding the budgeting financials.......................................... 389 Reviewing revenue and production ­budgets.................................. 392 Table of Contents Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 395 Budgeting with Cash or Accrual Accounting............................................ 395 Cash basis accounting: Using your checkbook to budget............. 396 I accrue, you accrue, we all accrue with accrual accounting....... 398 Budgeting to Produce the Income Statement and Balance Sheet.......... 398 The well-balanced balance sheet...................................................... 399 The incredible income statement..................................................... 399 Flexing Your Budget: When Plans Change................................................ 400 Controlling your business................................................................. 400 Dealing with budget variances.......................................................... 401 Implementing a flexible budget......................................................... 402 Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 407 Managing Long-Term Debt.......................................................................... 407 The many faces of notes payable..................................................... 408 Treasury bonds defined..................................................................... 413 The dark side of debt-free.................................................................. 414 Accounting for Bonds.................................................................................. 415 Valuing bonds payable....................................................................... 415 Figuring out the present value of a bond......................................... 416 Issuing at face value........................................................................... 417 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions................ 419 Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 421 Understanding How Job Costing Works.................................................... 421 Cost objects: The sponges that absorb money.............................. 422 Charging customers for direct and indirect costs.......................... 423 Implementing job costing in manufacturing: An example................. 425 Taking a Closer Look at Indirect Costs by Using Normal Costing.......... 428 Budgeting for indirect costs.............................................................. 429 Following a normal job costing system........................................... 430 Following the Flow of Costs through a Manufacturing System.............. 432 Control starts with control accounts............................................... 432 Walking through a manufacturing cost example............................ 433 Applying the methodology to other control accounts.................. 435 Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 437 Avoiding the Slippery Slope of Peanut Butter Costing............................ 437 Recognizing a single indirect cost allocation.................................. 438 A fly in the peanut butter: Dealing with different levels of client activity............................................................................... 439 Undercosting and overcosting.......................................................... 440 Designing an Activity-Based Costing System............................................ 442 Refining your approach...................................................................... 442 Grouping costs by using a cost hierarchy....................................... 443 Testing your ABC design.................................................................... 444 xvii xviii Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Using Activity-Based Costing to Compute Total Cost, Profit, and Sale Price............................................................................................ 448 Allocating indirect costs evenly by product................................... 449 Analyzing and reallocating cost activities....................................... 449 Changing allocations to cost pools.................................................. 450 Changing prices after ABC................................................................. 451 Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 453 Computing Contribution Margin................................................................ 454 Figuring total contribution margin................................................... 454 Calculating contribution margin per unit........................................ 456 Working out contribution margin ratio............................................ 456 Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis................................................... 457 Drafting a cost-volume-profit graph................................................. 457 Trying out the total contribution margin formula.......................... 459 Practicing the contribution margin per unit formula..................... 460 Eyeing the contribution margin ratio formula................................ 460 Generating a Break-Even Analysis.............................................................. 461 Plotting the break-even point............................................................ 461 Using the formula approach.............................................................. 462 Shooting for Target Profit............................................................................ 463 Observing Margin of Safety......................................................................... 465 Using a graph to depict margin of safety......................................... 465 Calculating the margin of safety....................................................... 465 Taking Advantage of Operating Leverage................................................. 466 Graphing operating leverage............................................................. 466 Looking at the operating leverage formula..................................... 467 Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis . . . . . . . 469 Setting Up Standard Costs........................................................................... 469 Establishing direct materials standards.......................................... 470 Determining direct labor standards................................................. 472 Calculating the overhead rate........................................................... 473 Adding up standard cost per unit..................................................... 474 Understanding Variances............................................................................ 474 Computing direct materials variances............................................. 475 Calculating direct labor variances.................................................... 478 Computing overhead variances........................................................ 481 Looking past the favorable/unfavorable label................................ 482 Teasing Out Variances................................................................................. 483 Interpreting variances in action........................................................ 483 Focusing on the big numbers............................................................ 484 Tracing little numbers back to big problems.................................. 485 Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 487 Differentiating Products.............................................................................. 487 Taking All Costs into Account with Absorption Costing......................... 488 Table of Contents Pricing at Cost-Plus...................................................................................... 489 Computing fixed markups.................................................................. 489 Setting a cost-plus percentage.......................................................... 490 Considering problems with cost-plus pricing................................. 490 Extreme Accounting: Trying Variable-Cost Pricing.................................. 491 Working out variable-cost pricing.................................................... 492 Spotting the hazards of variable-cost pricing................................. 493 Bull’s-Eye: Hitting Your Target Cost........................................................... 493 Calculating your target cost.............................................................. 494 Knowing when to use target costing................................................ 495 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions.................................................... 497 Chapter 1: Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue . . . 499 Defining Costs and Expenses in the Business World............................... 500 Satisfying the Matching Principle............................................................... 500 Identifying Product and Period Costs........................................................ 501 Discovering Which Costs Are Depreciated............................................... 501 Handling real property depreciation................................................ 502 Allocating costs between land and buildings.................................. 502 Expensing repairs and maintenance................................................ 503 Preparing a Depreciation Schedule............................................................ 503 Deciding When to Recognize Revenue....................................................... 505 Going over the revenue recognition principle................................ 505 Recognizing revenue and cash flow................................................. 506 Chapter 2: Exploring Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions . . . . . . . . . . 507 Discovering How Inventory Valuation Affects the Financial Statements.......................................................................... 507 Comparing merchandising and manufacturing companies.......... 508 Connecting inventory to revenue..................................................... 508 Logging Inventory for Service Companies................................................. 509 Classifying Inventory Types........................................................................ 509 Accounting for merchandising company inventory....................... 509 Accounting for manufacturing company inventory....................... 512 Getting to Know Inventory Valuation Methods........................................ 513 Understanding guidelines used for all methods............................. 513 Specific identification......................................................................... 514 Weighted average............................................................................... 514 First-in, first-out (FIFO)....................................................................... 515 Last-in, first-out (LIFO)....................................................................... 515 Comparing inventory cost-flow assumptions................................. 515 Preparing an Inventory Worksheet............................................................ 518 xix xx Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Chapter 3: Answering the Question: Should I Buy That? . . . . . . . . . . 519 Identifying Incremental and Opportunity Costs....................................... 520 Keeping It Simple: The Cash Payback Method......................................... 520 Using the cash payback method with equal annual net cash flows.................................................................................. 521 Applying the cash payback method when annual net cash flows change each year.................................................................. 522 It’s All in the Timing: The Net Present Value (NPV) Method.................. 523 Calculating time value of money with one payment for one year...................................................................................... 524 Finding time value of money with one payment held for two periods or more........................................................ 525 Calculating NPV with a series of future cash flows........................ 526 Measuring Internal Rate of Return (IRR)................................................... 529 Considering Qualitative Factors................................................................. 530 Chapter 4: Knowing When to Use Debt to Finance Your Business . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 533 Understanding the Basics of Debt Capital................................................. 534 Debt maturity...................................................................................... 534 Debt security....................................................................................... 535 Other debt attributes......................................................................... 536 Determining When Debt Is Most Appropriate.......................................... 537 When you can offer security or collateral....................................... 537 When business is stable..................................................................... 538 When you have financial strength.................................................... 538 Using Loans, Leases, and Other Sources of Debt..................................... 539 Borrowing from banks........................................................................ 539 Making friends with asset-based lenders........................................ 541 Leasing as a source of capital........................................................... 542 Tapping government programs and the SBA.................................. 543 Using other sources of debt-based capital...................................... 544 Getting Creative with Capital...................................................................... 545 Generating internal cash flow........................................................... 545 Leveraging unsecured creditors....................................................... 545 Going after government aid, gifts, and grants................................. 546 Partnering up....................................................................................... 546 Chapter 5: Interpreting Your Financial Results as a Manager . . . . . 547 Gauging the Relative Importance of Information..................................... 548 Reviewing Profit and Earnings.................................................................... 548 Judging profit performance............................................................... 548 Testing earnings per share (EPS) against change in bottom line.................................................................................. 549 Judging the Company’s Cash Position....................................................... 551 Tackling Extraordinary Gains and Losses................................................. 552 Recognizing the Risks of Restatement....................................................... 553 Remembering the Limits of Financial Reports.......................................... 554 Table of Contents Book IX: Auditing and Detecting Financial Fraud........ 555 Chapter 1: Mulling Over Sarbanes-Oxley Regulation . . . . . . . . . . . . 557 Pre-SOX Securities Laws.............................................................................. 558 The Securities Act of 1933: Arming investors with information.............................................................................. 558 The Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Establishing the SEC.......... 559 Other securities laws.......................................................................... 563 The Scope of SOX: Securities and Issuers................................................. 563 Determining what a security is......................................................... 564 Defining an issuer............................................................................... 565 Figuring out how stock exchanges work......................................... 566 Unveiling the SOX surprise................................................................ 567 The Post-SOX Paper Trail............................................................................ 569 Form 10-K............................................................................................. 569 Form 10-Q............................................................................................. 570 Form 8-K............................................................................................... 570 Chapter 2: Preventing Cash Losses from Embezzlement and Fraud . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 571 Setting the Stage for Protection.................................................................. 571 Preventing loss with internal controls............................................. 572 Recognizing the dual purpose of internal accounting controls............................................................................................ 573 Struggling with fraud committed by the business.......................... 574 Putting Internal Controls to Work.............................................................. 575 Going down the internal controls checklist.................................... 576 Considering some important details of internal control............... 580 Recognizing Limitations of Internal Controls........................................... 582 Keeping internal controls under control......................................... 583 Finding fraud that slips through the net.......................................... 583 Chapter 3: Assessing Audit Risk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 585 Using the Audit Risk Model......................................................................... 585 Listing the financial statements........................................................ 586 Introducing audit risk......................................................................... 586 Inherent risk: Recognizing the nature of a client’s business......... 587 Control risk: Assessing a client’s ability to detect and correct problems............................................................................ 589 Detection risk: Figuring out your chances of overlooking inaccuracies........................................................... 590 Following Risk Assessment Procedures.................................................... 592 Recognizing the nature of the company.......................................... 593 Examining the quality of company management............................ 593 Asking employees for information.................................................... 594 Analyzing processes and paperwork............................................... 595 Observing the client at work............................................................. 596 xxi xxii Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Figuring Out What’s Material and What Isn’t............................................ 597 Distinguishing errors from fraud...................................................... 598 Explaining the triangle of fraud......................................................... 600 Evaluating Your Audit Risk Results............................................................ 604 Tailoring the audit to a low-risk situation....................................... 604 Responding to a high-risk assessment............................................. 605 Documenting audit risk results......................................................... 606 Chapter 4: Collecting and Documenting Audit Evidence . . . . . . . . . . 607 Management Assertions: Assessing the Information a Client Gives You..................................................................................... 608 Defining financial statement presentation and disclosure............ 608 Monitoring classes of transactions.................................................. 609 Analyzing account balances.............................................................. 611 Eyeing the Four Concepts of Audit Evidence............................................ 612 The nature of the audit evidence...................................................... 612 The competence of the audit evidence............................................ 613 The sufficiency of the audit evidence.............................................. 614 The evaluation of the audit evidence............................................... 615 Applying Professional Judgment................................................................ 617 Exercising skepticism......................................................................... 617 Brainstorming with audit team members........................................ 618 Using Your Audit Program to Request the Right Evidence..................... 620 Documenting the Audit Evidence............................................................... 621 Types of documentation.................................................................... 621 Ownership and retention of the audit documentation.................. 624 Chapter 5: Auditing a Client’s Internal Controls . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 625 Defining Internal Controls........................................................................... 626 Identifying the Five Components of Internal Controls............................. 627 Determining When You Need to Audit Internal Controls........................ 629 Defining substantive strategy and control testing strategy.......... 629 Figuring out which strategy is best.................................................. 630 Testing a Client’s Reliability: Assessing Internal Control Procedures.................................................................................. 631 Considering external factors............................................................. 631 Evaluating how management assesses its controls....................... 632 Using questionnaires to evaluate internal controls....................... 634 Designing your tests of controls....................................................... 635 Using sampling to test internal controls.......................................... 636 Knowing when internal controls are sound or flawed................... 639 Documenting your conclusion.......................................................... 641 Limiting Audit Procedures When Controls Are Strong............................ 641 Tailoring Tests to Internal Control Weaknesses...................................... 642 Timing a Client’s Control Procedures........................................................ 643 Setting a timeline for the client......................................................... 644 Conducting interim versus year-end audits.................................... 644 Table of Contents Chapter 6: Getting to Know the Most Common Fraud Schemes . . . . 647 Frauds Committed by Businesses.............................................................. 647 Preying on vulnerable populations.................................................. 648 Picking investors’ pockets................................................................. 648 Doing business with bribes............................................................... 649 Laundering money.............................................................................. 649 Perpetrating construction fraud....................................................... 650 Dealing in subprime and predatory lending.................................... 651 Taking advantage of employees........................................................ 651 Frauds Committed against Businesses...................................................... 652 Employee theft.................................................................................... 653 Vendor and customer fraud.............................................................. 653 Insurance fraud................................................................................... 653 Real estate and mortgage fraud........................................................ 654 Bilking the Government............................................................................... 655 Tax fraud.............................................................................................. 655 Contract fraud..................................................................................... 658 Medicare and Medicaid fraud........................................................... 659 Social Security fraud........................................................................... 660 Introducing the Ponzi Scheme.................................................................... 661 Chapter 7: Cooked Books: Finding Financial Statement Fraud . . . . . 663 Exploring the Financial Statement Fraud Triangle................................... 664 Understanding the incentive behind financial statement fraud............................................................................... 664 Seeing the fraud opportunity............................................................ 665 Coming up with a rationalization for the fraud............................... 665 Spotting the Common Methods of Fraud.................................................. 666 Hidden liabilities................................................................................. 666 Cookie jar reserves............................................................................. 667 Off–balance sheet transactions......................................................... 667 Notes no one can comprehend......................................................... 668 Uncovering Financial Statement Fraud...................................................... 669 Comparative techniques.................................................................... 669 Ratio analysis...................................................................................... 670 Beneish model..................................................................................... 671 Data mining.......................................................................................... 672 Index........................................................................ 673 xxiii xxiv Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Introduction T o the general public, accounting means crunching numbers. Accountants are bean counters, whose job it is to make sure enough money is coming in to cover all the money going out. Most people also recognize that accountants help individuals and businesses complete their tax returns. Few people give much thought to the many other facets of accounting. Accounting is much more than just keeping the books and completing tax returns. Sure, that is a large part of it, but in the business world, accounting also includes setting up an accounting system, preparing financial statements and reports, analyzing financial statements, planning and budgeting for a business, attracting and managing investment capital, securing loans, analyzing and managing costs, making purchase decisions, and preventing and detecting fraud. Although no single book can help you master everything there is to know about all fields of accounting, this book provides the information you need to get started in the most common areas. About This Book Accounting All-In-One For Dummies expands your understanding of what accounting is and provides you with the information and guidance to master the skills you need in various areas of accounting. This book covers everything from setting up an accounting system to preventing and detecting fraud. This book gives you nine Books in one: ✓ Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System ✓ Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions ✓ Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries ✓ Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements ✓ Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 2 Accounting All-In-One For Dummies ✓ Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions ✓ Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions ✓ Book IX: Auditing and Detecting Financial Fraud Foolish Assumptions In order to narrow the scope of this book and present information and guidance that would be most useful to you, the reader, a few foolish assumptions about who you are had to be made: ✓ You’re an accountant, accountant wannabe, a businessperson who needs to know about some aspect of business accounting, or an investor who needs to know how to make sense of financial statements. This book doesn’t cover how to budget for groceries or complete your 1040 tax return. In other words, this book is strictly business. Some chapters are geared more toward accountants, while others primarily address business owners and managers. ✓ You’re compelled to or genuinely interested in finding out more about accounting. If you’re not motivated by a need or desire to acquire the knowledge and skills required to perform fundamental accounting tasks, you probably need to hire an accountant instead of becoming one. ✓ You can do the math. You don’t need to know trigonometry or calculus, but you do need to be able to crunch numbers by using addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Icons Used in This Book Throughout this book, icons in the margins cue you in on different types of information that call out for your attention. Here are the icons you’ll see and a brief description of each. It would be nice if you could remember everything you read in this book, but if you can’t quite do that, then remember the important points flagged with this icon. Tips provide insider insight. When you’re looking for a better, faster way to do something, check out these tips. Introduction “Whoa!” This icon appears when you need to be extra vigilant or seek professional help before moving forward. Beyond the Book In addition to the abundance of information and guidance on accounting that’s provided in this book, you also get access to more help on the web. There’s a free Cheat Sheet at www.dummies.com/cheatsheet/­accountingaio that you can check out from any web-enabled device. It features ten key a ­ ccounting terms, tips for controlling cash, essential formulas for cost accounting, and definitions of key financial accounting terms. It also explains the relationship between cash flow and profit. To dig into some bonus materials, visit www.dummies.com/extras/ accountingaio, where you’ll find articles that explain how to ✓ Choose accounts for a chart of accounts in your industry ✓ Create an audit trail to facilitate the review of your accounting records ✓ Adjust your accounting records with accruals and deferrals ✓ Make your business an attractive borrower ✓ Assess profitability of investments with present value and future value ✓ Manage inventory strategically to improve profit ✓ Eliminate bottlenecks that increase production costs ✓ Evaluate capital spending and opportunity costs ✓ Segregate duties to help prevent fraud Where to Go from Here Although you’re certainly welcome to read Accounting All-In-One For Dummies from start to finish, feel free to skip and dip, focusing on whichever area of accounting and whichever topic is most relevant to your current needs and interests. If you’re just getting started, Books I to III may be just what you’re looking for. If you’re facing the daunting challenge of preparing financial statements for a business, consult Books IV and V. If you own or manage a business, check out Books VI to VIII for information and guidance on managerial accounting. And if you’re in charge of preventing and detecting incidents of fraud, check out the chapters in Book IX. 3 4 Accounting All-In-One For Dummies Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System Visit www.dummies.com for free content that helps you learn more and do more. In this book… ✓ Wrap your brain around bookkeeping and accounting fundamentals. These basic concepts allow you to correctly post accounting transactions. ✓ Create a chart of accounts, so you can track debits and credits by using double-entry accounting. Every type of accounting transaction uses some combination of accounts. ✓ Maintain financial journals and the general ledger and use accounting software to simplify these tasks. These tools help you generate meaningful financial statements. ✓ Distinguish among cash, accrual, and other accounting methods and choose the right method for a business. Most businesses use accrual accounting, which allows the company to match revenue with the expenses incurred to generate the revenue. Chapter 1 Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics In This Chapter ▶ Examining the differences between bookkeeping and accounting ▶ Getting to know the accounting cycle ▶ Maintaining balance with the fundamental accounting equation M ost folks aren’t enthusiastic bookkeepers. You probably balance your checkbook against your bank statement every month and somehow manage to pull together all the records you need for your annual federal income tax return. But if you’re like most people, you stuff your bills in a drawer and just drag them out once a month when you pay them. Individuals can get along quite well without much bookkeeping — but the exact opposite is true for a business. A business needs a good bookkeeping and accounting system to operate day to day. A business needs accurate and timely data to operate effectively. In addition to facilitating day-to-day operations, a company’s bookkeeping and accounting system serves as the source of information for preparing its periodic financial statements, tax returns, and reports to managers. The accuracy of these reports is critical to the business’s survival. That’s because managers use financial reports to make decisions. If the reports aren’t ­accurate, managers can’t make intelligent decisions. Obviously, then, a business manager must be sure that the company’s ­bookkeeping and accounting system is dependable and up to snuff. This chapter shows you what bookkeepers and accountants do, so you have a clear idea of what it takes to ensure that the information coming out of the accounting system is complete, accurate, and timely. 8 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Knowing What Bookkeeping and Accounting Are All About In a nutshell, accountants “keep the books” of a business (or not-for-profit or government entity) by following systematic methods to record all the ­financial activities and prepare summaries. This summary information is used to create financial statements. Financial statements are sent to stakeholders. Stakeholders are people who have a stake in the business’s success or failure. Here are some examples of stakeholders: ✓ Stockholders: If you own stock in General Electric, for example, you receive regular financial reports. Stockholders are owners of the ­business. They need to know the financial condition of the business they own. ✓ Creditors: Entities that loan money to your business are creditors. They need to review financial statements to determine whether your business still has the ability to repay principal and make interest payments on the loan. ✓ Regulators: Most businesses have to answer to some type of ­regulator. If you produce food, you send financial reports to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Reviewing financial statements is one ­­responsibility of a regulator. The following sections help you embark on your journey to develop a better understanding of bookkeeping and accounting. Here you discover the ­differences between the two and get a bird’s-eye view of how they interact. Distinguishing between bookkeeping and accounting Distinguishing between bookkeeping and accounting is important, because they’re not completely interchangeable. Bookkeeping refers mainly to the recordkeeping aspects of accounting — the process (some would say the drudgery) of recording all the detailed information regarding the transactions and other activities of a business (or other organization, venture, or project). The term accounting is much broader; it enters the realm of designing the bookkeeping system, establishing controls to make sure the system is ­working well, and analyzing and verifying the recorded information. Accountants give orders; bookkeepers follow them. Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics Bookkeepers spend more time with the recordkeeping process and d ­ ealing with problems that inevitably arise in recording so much information. Accountants, on the other hand, have a different focus. You can think of accounting as what goes on before and after bookkeeping: accountants design the bookkeeping and accounting system (before) and use the ­information that the bookkeepers enter to create financial statements, tax returns, and various internal-use reports for managers (after). Taking a panoramic view of bookkeeping and accounting Figure 1-1 presents a panoramic view of bookkeeping and accounting for businesses and other entities that carry on business activities. This brief overview can’t do justice to all the details of bookkeeping and accounting, of course. But it serves to clarify important differences between bookkeeping and accounting. Figure 1-1: Panoramic view of bookkeeping and accounting. , ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Bookkeeping has two main jobs: recording the financial effects and other relevant details of the wide variety of transactions and other activities of the entity; and generating a constant stream of documents and electronic outputs to keep the business operating every day. Accounting, on the other hand, focuses on the periodic preparation of three main types of output — reports to managers, tax returns (income tax, sales tax, payroll tax, and so on), and financial statements and reports. These ­outputs are completed according to certain schedules. For example, financial statements are usually prepared every month and at the end of the year (12 months). 9 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 10 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Accounting All-In-One For Dummies is concerned predominately with f­ inancial and management accounting. Financial accounting refers to the periodic ­preparation of general-purpose financial statements (see Books IV and V ). General purpose means that the financial statements are prepared according to s­ tandards established for financial reporting to stakeholders, as explained earlier in this chapter. These financial statements are useful to managers as well, but managers need more information than is reported in the external financial s­ tatements of a business. Much of this management information is confidential and not for circulation outside the business. Management accounting refers to the ­preparation of internal accounting reports for business managers. Management accounting is used for planning business activity (Book VI) and to make informed business decisions (Book VII). This chapter offers a brief survey of bookkeeping and accounting, which you may find helpful before moving on to the more hands-on financial and ­management topics. Wrapping Your Brain around the Accounting Cycle Figure 1-2 presents an overview of the accounting cycle. These are the basic steps in virtually every bookkeeping and accounting system. The steps are done in the order presented, although the methods of performing the steps vary from business to business. For example, the details of a sale may be entered by scanning bar codes in a grocery store, or they may require an ­in-depth legal interpretation for a complex order from a customer for an expensive piece of equipment. The following is a more detailed description of each step: 1. Prepare source documents for all transactions, operations, and other events of the business; source documents are the starting point in the bookkeeping process. When buying products, a business gets an invoice from the supplier. When borrowing money from the bank, a business signs a note ­payable, a copy of which the business keeps. When preparing payroll checks, a business depends on salary rosters and time cards. All of these key ­business forms serve as sources of information entered into the ­bookkeeping system — in other words, information the bookkeeper uses in recording the financial effects of the activities of the business. Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics 11 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System Figure 1-2: Basic steps of the accounting cycle. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2. Determine the financial effects of the transactions, operations, and other events of the business. The activities of the business have financial effects that must be recorded — the business is better off, worse off, or affected in some way as the result of its transactions. Examples of typical business ­transactions include paying employees, making sales to customers, ­borrowing money from the bank, and buying products that will be sold to customers. The bookkeeping process begins by determining the ­relevant information about each transaction. The chief accountant of the business establishes the rules and methods for measuring the financial effects of transactions. Of course, the bookkeeper should comply with these rules and methods. 3. Make original entries of financial effects in journals, with appropriate references to source documents. Using the source documents, the bookkeeper makes the first, or o ­ riginal, entry for every transaction into a journal; this information is later posted in accounts (see the next step). A journal is a chronological record of transactions in the order in which they occur — like a very detailed personal diary. Here’s a simple example that illustrates recording a transaction in a ­journal. Expecting a big demand from its customers, a retail ­bookstore purchases, on credit, 100 copies of The Beekeeper Book from the ­publisher, Animal World. The books are received, a few are placed on 12 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System the shelves, and the rest are stored. The bookstore now owns the books and owes Animal World $2,000, which is the cost of the 100 copies. This example focuses solely on recording the purchase of the books, not recording subsequent sales of the books and payment to Animal World. The bookstore has established a specific inventory asset account called “Inventory–Trade Paperbacks” for books like this. And the liability to the publisher should be entered in the account “Accounts Payable– Publishers.” Therefore, the original journal entry for this purchase records an increase in the inventory asset account of $2,000 and an increase in the accounts payable account of $2,000. Notice the balance in the two sides of the transaction: an asset increases $2,000 on the one side and a liability increases $2,000 on the other side. All is well (­ assuming no mistakes). 4. Post the financial effects of transactions to accounts, with references and tie-ins to original journal entries. As Step 3 explains, the pair of changes for the bookstore’s purchase of 100 copies of this book is first recorded in an original journal entry. Then, sometime later, the financial effects are posted, or recorded in the s­ eparate accounts — one an asset and the other a liability. Only the ­official, e ­ stablished chart, or list of accounts, should be used in r­ ecording transactions. An account is a separate record, or page, for each asset, each liability, and so on. One transaction affects two or more accounts. The journal entry records the whole transaction in one place; then each piece is recorded in the accounts affected by the t­ ransaction. After ­posting all transactions, a trial balance is generated. This d ­ ocument lists all the accounts and their balances, as of a certain date. The importance of entering transaction data correctly and in a timely manner cannot be stressed enough. The prevalence of data entry errors is one important reason that most retailers use cash registers that read bar-coded information on products, which more accurately captures the necessary information and speeds up data entry. 5. Perform end-of-period procedures — the critical steps for getting the accounting records up-to-date and ready for the preparation of ­management accounting reports, tax returns, and financial statements. A period is a stretch of time — from one day (even one hour) to one month to one quarter (three months) to one year — that’s determined by the needs of the business. Most businesses need accounting reports and financial statements at the end of each quarter, and many need monthly financial statements. Before the accounting reports can be prepared at the end of the period (see Figure 1-1), the bookkeeper needs to bring the accounts up to date and complete the bookkeeping process. One such end-of-period ­requirement, for example, is recording the depreciation expense for the period (see Book III, Chapter 1 for more on depreciation). Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics The accountant needs to be heavily involved in end-of-period ­procedures and be sure to check for errors in the business’s accounts. Data entry clerks and bookkeepers may not fully understand the unusual nature of some business transactions and may have entered ­transactions incorrectly. One reason for establishing internal controls (see Book II, Chapter 1) is to keep errors to an absolute minimum. Ideally, accounts should contain no errors at the end of the period, but the accountant can’t assume anything and should perform a final check for any errors. 6. Compile the adjusted trial balance for the accountant, which is the basis for preparing management reports, tax returns, and financial statements. In Step 4, you see that a trial balance is generated after you post the accounting activity. After all the end-of-period procedures have been completed, the bookkeeper compiles a comprehensive listing of all accounts, which is called the adjusted trial balance. Modest-sized ­businesses maintain hundreds of accounts for their various assets, ­liabilities, owners’ equity, revenues, and expenses. Larger businesses keep thousands of accounts. The accountant takes the adjusted trial balance and combines similar accounts into one summary amount that is reported in a financial report or tax return. For example, a business may keep hundreds of separate inventory accounts, every one of which is listed in the adjusted trial balance. The accountant collapses all these accounts into one summary inventory account presented in the balance sheet of the business. In grouping the accounts, the accountant should comply with established financial reporting standards and income tax requirements. 7. Close the books — bring the bookkeeping for the fiscal year just ended to a close and get things ready to begin the bookkeeping ­process for the coming fiscal year. Books is the common term for a business’s complete set of accounts along with journal entries. A business’s transactions are a constant stream of activities that don’t end tidily on the last day of the year, which can make preparing financial statements and tax returns ­challenging. The business has to draw a clear line of demarcation between activities for the year ended and the year to come by closing the books for one year and starting with fresh books for the next year. Most medium-sized and larger businesses have an accounting manual that spells out in great detail the specific accounts and procedures for recording transactions. A business should regularly review its chart of accounts and accounting rules and policies and make revisions. Companies don’t take this task lightly; discontinuities in the accounting system can be major shocks and have to be carefully thought out. The remaining chapters in Book I lead you through the process of developing an accounting system. See Book III for details on adjusting and closing entries. 13 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 14 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Working the Fundamental Accounting Equation The fundamental accounting equation (also known as the accounting equation or the balance sheet equation) helps explain the concept that all transactions must balance. Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity Net assets equals assets minus liabilities. If you do some algebra and subtract liabilities from both sides of the previous equation, you get this formula: Assets – Liabilities = Owners’ equity Or: Net assets = Owners’ equity Before going any further, acquaint yourself with the cast of characters in the equation: ✓ Assets are resources a company owns. Book IV, Chapter 3 discusses all the typical types of business assets. Some examples are cash, ­equipment, and cars. You use assets to make money in your business. In other words, the resources are used up over time to generate sales and profits. ✓ Liabilities are debts the company owes to others — people other than owners of the business. See Book IV, Chapter 4 for the scoop on ­liabilities. The biggies are accounts payable and notes payable. ✓ Owners’ equity (or simply equity) is what’s left over in the business at the end of the day. If you sold all your assets for cash, then paid off all your liabilities, any cash remaining would be equity. Many ­accounting textbooks define equity as the owners’ claim to the company’s net assets. Book IV, Chapter 5 discusses the different components of equity. You may read the explanation of owners’ equity and think, “That’s just another way to say ‘net worth.’” But you can’t use the term net worth interchangeably with owners’ equity in an accounting setting. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), explained in Book IV, Chapter 1, don’t allow accountants to restate all assets to their fair market value, which would be required to calculate a company’s net worth. Chapter 1: Grasping Bookkeeping and Accounting Basics Here’s a simple example of the fundamental accounting equation at work: Assets = Liabilities + Equity $100 = $40 + $60 Or, after subtracting liabilities from each side of the equation: Assets – Liabilities = Equity $100 – $40 = $60 Finally, you can restate assets less liabilities and net assets: Net assets = Owners’ equity $60 = $60 15 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 16 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Chapter 2 Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts In This Chapter ▶ Introducing the chart of accounts ▶ Warming up with balance sheet accounts ▶ Creating your own chart of accounts ▶ Grasping the basics of debits and credits ▶ Getting schooled in double-entry accounting C an you imagine the mess your checkbook would be if you didn’t record each check you wrote? If you’re like most people, you’ve probably forgotten to record a check or two on occasion, but you certainly learn your lesson when you realize that an important payment bounces as a result. Yikes! Keeping the books of a business can be a lot more difficult than maintaining a personal checkbook. You have to carefully record each business transaction to make sure that it goes into the right account. This careful bookkeeping gives you an effective tool for figuring out how well the business is doing financially. You need a road map to help you determine where to record all those transactions. This road map is called the chart of accounts. This chapter introduces you to the chart of accounts and explains how to set up your chart of accounts. This chapter also spells out the differences between debits and credits and orients you to the fine art of double-entry accounting. Getting to Know the Chart of Accounts The chart of accounts is the road map that a business creates to organize its financial transactions. After all, you can’t record a transaction until you know where to put it! Essentially, this chart is a list of all the accounts a 18 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System business has, organized in a specific order; each account has a description that includes the type of account and the types of transactions that should be entered into that account. Every business creates its own chart of accounts based on the nature of the business and its operations, so you’re unlikely to find two businesses with the exact same chart. Connecting the chart of accounts to financial statements Some basic organizational and structural characteristics are common to all Charts of Accounts. The organization and structure are designed around two key financial reports: ✓ The balance sheet shows what your business owns (assets) and who has claims on those assets (liabilities and equity). ✓ The income statement shows how much money your business took in from sales and how much money it spent to generate those sales. You can find out more about income statements and balance sheets in Books IV and V. The following lists present a common order for these accounts within each of their groups, based on how they appear on the financial statements. Organizing the accounts The chart of accounts starts with the balance sheet accounts, which include ✓ Current assets: Accounts that track what the company owns and expects to use in the next 12 months, such as cash, accounts receivable (money collected from customers), and inventory ✓ Long-term assets: Accounts that track what assets the company owns that have a lifespan of more than 12 months, such as buildings, ­furniture, and equipment ✓ Current liabilities: Accounts that track debts the company must pay over the next 12 months, such as accounts payable (bills from vendors, contractors, and consultants), interest payable, and credit cards payable ✓ Long-term liabilities: Accounts that track debts the company must pay over a period of time longer than the next 12 months, such as mortgages payable and bonds payable Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts ✓ Equity: Accounts that track the owner’s claims against the company’s net assets, which includes any money invested in the company, any money taken out of the company, and any earnings that have been reinvested in the company The rest of the chart is filled with income statement accounts, which include ✓ Revenue: Accounts that track sales of goods and services as well as revenue generated for the company by other means ✓ Cost of goods sold: Accounts that track the direct costs involved in selling the company’s goods or services ✓ Expenses: Accounts that track expenses related to running the business that aren’t directly tied to the sale of individual products or services When developing the chart of accounts, you start by listing all asset, liability, equity, revenue, and expense accounts. All these accounts come from two places: the balance sheet and the income statement. This chapter introduces the key account types found in most businesses, but this list isn’t cast in stone. You should develop an account list that makes the most sense for how you’re operating your business and the financial information you want to track. The chart of accounts is a management tool that helps you make smart business decisions. You’ll probably tweak the accounts in your chart annually and, if necessary, add accounts during the year if you find something that requires more detailed tracking. You can add accounts during the year, but it’s best not to delete accounts until the end of a 12-month reporting period. Balancing transactions A chart of accounts helps you keep your balance sheet accounts in balance in accordance with the balance sheet equation discussed in Chapter 1: Assets = Liabilities + Equity As you see in the prior section, the chart of accounts groups accounts based on the three categories in the balance sheet equation. All the asset accounts, for example, have account numbers that are close together, as explained in the next section. You can easily separate the chart of accounts into assets, liabilities, and equity — and see whether the balance sheet equation balances (in total dollars). 19 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 20 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Setting Up Your Chart of Accounts Cooking up a useful chart of accounts doesn’t require any secret sauce. All you need to do is list all the accounts that apply to your business. A good brainstorming session usually does the trick. When first setting up your chart of accounts, don’t panic if you can’t think of every type of account you may need for your business. Adding to the chart of accounts at any time is very easy. Just add the account to the list and distribute the revised list to any employees who use the chart of accounts for entering transactions into the system. (Even employees not involved in bookkeeping need a copy of your chart of accounts if they code invoices or other transactions or indicate to which account those transactions should be recorded.) The chart of accounts usually includes at least three columns: ✓ Account: Lists the account names ✓ Type: Lists the type of account — asset, liability, equity, revenue, cost of goods sold, or expense ✓ Description: Contains a description of the type of transaction that should be recorded in the account Nearly all companies also assign numbers to the accounts, to be used for coding charges. If your company is using a computerized system, the computer automatically assigns the account number. Otherwise, you need to develop your own numbering system. The most common number system is: ✓ Asset accounts: 1,000 to 1,999 ✓ Liability accounts: 2,000 to 2,999 ✓ Equity accounts: 3,000 to 3,999 ✓ Revenue accounts: 4,000 to 4,999 ✓ Cost of goods sold accounts: 5,000 to 5,999 ✓ Expense accounts: 6,000 to 6,999 This numbering system matches the one used by computerized accounting systems, making it easy for a company to transition to automated books at some future time. Most companies create an accumulated depreciation account and match it with each unique fixed asset account. So, if you have a fixed asset account called delivery trucks, you likely have an account called accumulated depreciation – delivery trucks. Book value is defined in Book III, Chapter 1 as cost less accumulated depreciation. This chart of accounts approach allows Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts management to view each asset’s original cost and the asset’s accumulated depreciation together — and calculate book value. If you choose a computerized accounting system, one major advantage is that a number of different Charts of Accounts have been developed for various types of businesses. When you get your computerized system, whichever accounting software you decide to use, all you need to do is review its list of chart options for the type of business you run, delete any accounts you don’t want, and add any new accounts that fit your business plan. If you’re setting up your chart of accounts manually, be sure to leave a lot of room between accounts to add new accounts. For example, number your cash in checking account 1,000 and your accounts receivable account 1,100. That leaves you plenty of room to add other accounts to track cash. Mulling Over Debits versus Credits In this section, you discover the mechanism of journal entries, which you use to enter financial information into the company’s accounting software. To properly post journal entries, you need to understand debits and credits. Writing journal entries is a major area of confusion for anyone who’s just getting started in accounting, because they involve debits and credits that are often counterintuitive. If you’re just starting out in accounting, consider reading this section more than once. After you read this section and start posting some journal entries, you’ll get the hang of it. These rules regarding debits and credit are always true: ✓ Debits are always on the left. In journal entries, debits appear to the left of credits. ✓ Credits are always on the right. In journal entries, credits appear to the right of debits. See the next section for examples of journal entries. The following rules are also true, but with a few exceptions: ✓ Assets and expenses are debited to add to them and credited to subtract from them. In other words, for assets and expenses, a debit increases the account, and a credit decreases it. ✓ Liability, revenue, and equity accounts are just the opposite: These accounts are credited to add to them and debited to subtract from them. In other words, for liability, revenue, and equity accounts, a debit decreases the account, and a credit increases it, as you would expect. 21 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 22 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System This book covers three exceptions to these two rules. Treasury stock (covered in Book IV, Chapter 5), allowance for doubtful accounts (see Book IV, Chapter 3), and accumulated depreciation (Book III, Chapter 1) are contra-accounts, which offset the balance of a related account. Other than these exceptions, these two rules hold true. Understanding Double-Entry Accounting All businesses, whether they use the cash-basis or accrual accounting method (see Chapter 4), use double-entry accounting — a practice that helps minimize errors and increase the chance that your books balance. Double-entry accounting doesn’t mean you enter all transactions twice; it means that you enter both sides of the transaction, debiting one account and crediting another. Revisiting the balance sheet equation In double-entry accounting, the balance sheet equation plays a major role, as explained in “Balancing transactions” earlier in this chapter. In order to change the balance of any accounts, you use a combination of debits and credits. In some cases, you may debit and credit multiple accounts to record the same transaction. Regardless of how many accounts are affected, these additional rules hold true: ✓ The total dollar amount debited will equal the total amount credited. ✓ The total dollar change in the asset accounts (increase or decrease) will equal the change in the total dollar amount of liabilities and equity. This concept is consistent with the balance sheet equation: Assets on the left must equal liabilities on the right. Recording journal entries All accounting transactions for a business must be recorded as journal entries, following a specific three-column format followed by a transaction description: ✓ Account titles in the left column ✓ Debit dollar amounts in the middle column ✓ Credit dollar amounts in the right column ✓ Transaction description below the journal entry (to indicate the nature and purpose of the transaction for future reference) Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts Here’s an example: Book I Account Debit Inventory $3,000 Credit Accounts payable $3,000 To purchase sprockets for sale to customers. The following sections present some typical journal entries — entries that many companies frequently post in their accounting records. Posting entries to one side of the balance sheet equation Suppose you purchase a new $1,500 desk for your office. This transaction actually has two parts: You spend an asset — cash — to buy another asset — furniture. So, you must adjust two accounts in your company’s books: the cash account and the furniture account. Here’s what the transaction looks like in double-entry accounting: Account Debit Furniture $1,500 Cash 23 Credit $1,500 To purchase a new desk for the office. In this transaction, the debit increases the value of the furniture account, and the credit decreases the value of the cash account. Both accounts impacted are asset accounts, so the transaction affects only the assets side of the balance sheet equation: Assets + $1,500 furniture – $1,500 cash = L iabilities (no change) + Equity (no change) In this case, the books stay in balance because the exact dollar amount that increases the value of the furniture account decreases the value of the cash account. Using both sides of the equation To see how you record a transaction that impacts both sides of the balance sheet equation, consider an example that records the purchase of inventory. Suppose you purchase $5,000 worth of widgets on credit. These new Setting Up Your Accounting System 24 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System widgets add value to both inventory (an asset account) and accounts payable (a liability) account. Here’s what the transaction looks like in double-entry accounting: Account Debit Inventory $5,000 Accounts payable Credit $5,000 To purchase widgets for sale to customers. In this case, the books stay in balance because both sides of the equation (assets on the left and liabilities on the right) increase by $5,000: Inventory + $5,000 = Accounts payable + $5,000 + Equity (no change) You can see from the two example transactions in this section how double-entry accounting helps to keep your books in balance — as long as each entry into the books is balanced. Balancing your entries may look simple here, but sometimes entries can get complex when more than two accounts are impacted by the transaction. Figuring out a complex journal entry To take the subject of journal entries one step further, take a look at a more complex journal entry. Assume you sell a company truck. You bought the truck for $30,000. As of the date of sale, you’ve recognized $25,000 of accumulated depreciation. You receive $6,000 for the sale. The transaction is complex, because more than one debit and credit are required. Starting with cash As an accountant, you have several issues to resolve. First, consider which accounts in the chart of accounts are affected. Second, the total debits must equal total credits. Accountants figure out journal entries every day. If you’re not sure where to start, think about whether or not cash should be part of the journal entry. In this case, the answer is yes. Because cash increased, you need to debit the asset account cash for $6,000. Now go over the other “knowns” for this transaction. You sold someone the truck (an asset). In the “Mulling over Debits versus Credits” section earlier in this chapter, you see that you credit to reduce assets. The truck account should be credited for $30,000. Chapter 2: Outlining Your Financial Road Map with a Chart of Accounts 25 Getting to a balanced entry Book I In Book III, Chapter 1, you discover that accumulated depreciation represents all depreciation taken on an asset since the purchase date. You also see that accumulated depreciation carries a credit balance. When you sell the truck, you remove the accumulated depreciation by debiting the account for $25,000. Setting Up Your Accounting System Now for the hardest part. So far, you’ve debited cash $6,000 and debited accumulated depreciation for $25,000. On the credit side, you credited the truck account for $30,000. In total, you have $31,000 in debits ($6,000 + $25,000) and $30,000 in credits. To balance this entry you need an additional $1,000 credit. Think about which account you should use. If you sell an asset, accounting standards require that you record a gain or loss on sale. Because you need a credit entry, you record a gain. Here’s how your complex journal entry looks: Account Debit Cash $6,000 Accumulated depreciation $25,000 Credit Truck $30,000 Gain on sale of truck $1,000 To record the sale of a truck for a gain. The combination for the cash received and depreciation removed ($31,000) was more than the original cost of the truck sold ($30,000). The result is a gain of $1,000. This thought process is what accountants use to post complex journal entries. 26 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Chapter 3 Using Journal Entries and Ledgers In This Chapter ▶ Becoming familiar with journals and the general ledger ▶ Writing journal entries ▶ Balancing the books ▶ Saving time and reducing errors with accounting software A ccounting involves a great deal of record keeping or booking — the ­process of recording accounting transactions. Some booking tasks involve basic data entry done by clerks. Junior accountants or bookkeepers may p ­ erform other booking tasks, such as preparing journal entries — the ­accountant’s way to enter transactions into the accounting system. (For e ­ xample, the accountant records any bank charges shown on the company’s monthly bank statement.) You find out more about journal entries later in this chapter. Whether you’ll need to book journal entries during your accounting career depends on a couple factors. If you work for a small company in a one- or two-person accounting department, you could very well be the c­ ontroller (the chief accounting officer for the business) and be doing the journal entries yourself. If, instead, you work for a large accounting firm that p ­ rovides ­services to many clients, chances are you won’t book journal entries ­yourself. However, you’ll most certainly review journal entries while ­providing your services, such as when you audit a company’s financial ­statements. And you may propose journal entries for your client to book if you find errors. No matter where your accounting career takes you, you need to know what booking involves, as explained in this chapter. Keeping a Journal Accounting journals, like diaries, keep a record of events. But a ­ ccounting ­journals record business transactions taking place within a company’s ­accounting ­department. Accountants call journals the books of original entry because no transactions get into the accounting records without being entered into a journal first. 28 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System A business can have many different types of journals. In this section you find out about the most common journals, which are tailored to handle cash, accrual, and special transactions. Using journals to record cash transactions All transactions affecting cash go into the cash receipts or cash disbursements journal. Some accountants and accounting software programs refer to the record of cash disbursements as the cash payments journal. No worries — both terms mean the same thing. When accountants use the word cash, it doesn’t just mean paper money and coinage; it includes checks and credit card transactions. In accounting, cash is a generic term for any payment method that is assumed to be automatic. See Book IV, Chapter 3 for balance sheet details. When you sign a check and give it to the clerk behind the store counter, part of your implicit understanding is that the funds are immediately available to clear the check. Ditto paying with a credit card, which represents an immediate satisfaction of your debit with the vendor. Cash receipts journal The cash receipts journal keeps a record of all payments a business receives in cash or by check, debit card, or credit card. Book II, Chapter 3 discusses cash activity related to sales to customers. This discussion of cash covers a variety of transactions. Here are examples of some cash events that require posting to the cash receipts journal: ✓ Customer sales made for paper money and coinage: Many types of businesses still have booming cash sales involving the exchange of paper money and coins. Some examples are convenience stores, retail shops, and some service providers such as hair salons. ✓ Customers making payments on their accounts: If a business lets its customers buy now and pay later, any payments due are entered into accounts receivable, which is money customers owe the business. See “Recording accrual transactions,” later in this chapter, for details. Any payments a customer makes toward those amounts owed are recorded in the cash receipts journal. ✓ Interest or dividend income: When a bank or investment account pays a business for the use of its money in the form of interest or dividends, the payment is considered a cash receipt. Many businesses record ­interest income reported on their monthly bank statements in the ­general journal, discussed a little later in this section. Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers Interest and dividend income is also known as portfolio income and may be considered passive income because the recipient doesn’t have to work to receive the portfolio income (as you do for your paycheck). ✓ Asset sales: Selling a business asset, such as a car or office furniture, can also result in a cash transaction. As an example, suppose a company is outfitting its executive office space with deluxe new leather chairs and selling all the old leather chairs to a furniture liquidator; the two parties exchange cash to complete the sale. Keep in mind that this list isn’t comprehensive; these are just a few of the many instances that may necessitate recording a transaction in the cash receipts journal. Cash receipts may receive different treatment on a company’s income s­ tatement. For example, cash sales to customers are treated one way, while cash received for the sale of a building — a transaction that’s not part of the normal business activity — is treated differently. The details are explained in Book IV, Chapter 2. Setting up the cash receipts journal The cash receipts journal normally has two columns for debits and four columns for credits: ✓ Debit columns: Because all transactions in the cash receipts journal involve the receipt of cash, one of the debit columns is always for cash. The other is for sales discounts, which reflect any discount the business gives to a good customer who pays early. For example, a customer’s invoice is due within 30 days, but if the customer pays early, it gets a 2 percent discount. ✓ Credit columns: To balance the debits, a cash receipts journal contains four credit columns: • Sales • Accounts receivable • Sales tax payable, which is the amount of sales tax the business collects on a transaction (and doesn’t apply to every transaction) • Miscellaneous, which is a catchall column where you record all other cash receipts such as interest and dividends Not all sales are subject to sales tax. Your state department of revenue ­ etermines which sales transactions are taxable. For example, in many states, d fees for accounting or legal services aren’t subject to sales tax. 29 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 30 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System In addition to the debit and credit columns, a cash receipts journal also ­contains at least two other columns that don’t have anything to do with debits or credits: ✓ The date the transaction occurs ✓ The name of the account affected by the transaction Depending on the company or accounting system, additional columns may be used as well. Figure 3-1 shows an example of a portion of a cash receipts journal. Figure 3-1: A partial cash receipts journal. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Cash disbursements journal On the flip side, any payment the business makes by using a form of cash gets recorded in the cash disbursements (or payments) journal. Here are a few examples of transactions that appear in a cash disbursements journal: ✓ Merchandise purchases: When a merchandiser, a company selling goods to the public, pays cash for the goods it buys for resale (inventory), the transaction goes in the cash disbursement journal. ✓ Payments the company is making on outstanding accounts: This includes all cash disbursements a company makes to pay for goods or services it obtained from another business and didn’t pay for when the original transaction took place. More on this topic in the “Recording accrual transactions” section later in this chapter. ✓ Payments for operating expenses: These transactions include checks or bank transfers a business uses to pay utility or telephone invoices. Operating expenses are incurred to manage your day-to-day business, in addition to your cost of sales. The cash disbursements journal normally has two columns for debits and two for credits: Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers ✓ Credit columns: Because all transactions in the cash disbursements journal involve the payment of cash, one of your credit columns is for cash. The other is for purchase discounts, which are reductions in the amount a company has to pay the vendors for any purchases on account. For example, a business offers vendors a certain discount amount if they pay their bills within a certain number of days. It’s the same process that’s explained in the earlier cash receipts journal ­section. In this case, the company pays less, due to a discount. With cash receipts, a discount means that the company may receive less. ✓ Debit columns: To balance these credits, the debit columns in a cash ­disbursements journal are accounts payable and miscellaneous (a ­catchall column in which you record all other cash payments for transactions, such as the payment of operating expenses). A cash disbursements journal also contains at least three other columns that don’t have anything to do with debiting or crediting: ✓ The date the transaction occurs ✓ The name of the account affected by the transaction ✓ The pay-to entity (to whom the payment is made) Depending on the company or accounting system used, more columns could be used as well. Figure 3-2 shows an example of a partial cash disbursements journal. Figure 3-2: A partial cash disburse­ ments journal. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Recording accrual transactions Accrual transactions take place whenever cash doesn’t change hands. For example, a customer makes a purchase with a promise to pay within 30 days. Using accruals and recording business transactions using the accrual method are the backbone of accounting. Unfortunately, figuring out accruals, ­understanding how accrual transactions interact with cash transactions, and knowing when to record an accrual transaction can be quite a challenge. 31 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 32 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Never fear. The following sections introduce the two accrual workhorse journals — the sales and purchases journals — walk you through the accrual transactions you’re likely to encounter, and provide a sampling of typical accrual transactions. Book III, Chapter 6 explains many types of accrual ­journal entries in detail. Sales journal The sales journal records all sales that a business makes to customers on account, which means no money changes hands between the company and its customer at the time of the sale. A sales journal affects two d ­ ifferent accounts: accounts receivable and sales. In the sales journal, accounts ­receivable and sales are always affected by the same dollar amount. Figure 3-3 presents an example of a sales journal. Figure 3-3: A partial sales journal. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. When you record credit sales in your sales journal, you follow up by posting the transactions to each customer’s listing in the accounts receivable ledger. (See the “Bringing It All Together in the Ledger” later in this chapter.) Use the sales journal only for recording sales on account. Sales returns, which reflect all products customers return to the company after the sales are done, aren’t recorded in the sales journal. Instead, you record them in the general journal, discussed later in this chapter. Purchases journal Any time a business buys products or services by using credit (on account), it records the transaction in its purchases journal. The purchases journal typically has a column for date, number, and amount. It also has the following columns: ✓ Accounts payable: Because the company is purchasing on account, the current liability account called “accounts/trade payable” is always affected. ✓ Terms: This column shows any discount terms the company may have with the vendor. For example, 2/10, n/30 means the company gets a 2 percent discount if it pays within 10 days; otherwise, the full amount is due in 30 days. (The n in this shorthand stands for “net.”) Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers ✓ Name: The company records the name of the vendor from whom the purchase is made. ✓ Account: This column shows to which financial statement account(s) the purchase is taken. The example in Figure 3-4 shows two accounts — accounts payable (A/P) and purchases. Because no other accounts (such as sales tax) are affected, A/P and purchases are for the same dollar amount. If the company collects sales tax too, a column is added to report this amount as well. Figure 3-4: A partial purchases journal. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Exploring other journals The discussion of journals wouldn’t be complete without a brief rundown of other special journals you’ll see during your foray into accounting, as well as the general journal. The following sections cover both topics. Special journals Here are three additional journals you’ll encounter: ✓ Payroll journal: This journal records all payroll transactions including gross wages, taxes withheld, and other deductions (such as health insurance paid by the employee) leading to net pay, which is the amount shown on the employee’s check. Head over to Book II, Chapters 4 and 5 for more on payroll accounting. ✓ Purchases return and allowances journal: This journal shows all ­subtractions from gross purchases because of products a company returns to a vendor or discounts given to the company by the vendor. ✓ Sales returns and allowances journal: This journal shows all ­subtractions from gross sales as a result of products customers return or discounts given to customers. This list isn’t all-inclusive; some companies have other journals, and some smaller companies may not use all of these. However, if you understand the basic methodology of all the journals discussed in this chapter, you’ll be well prepared to tackle journal entries. 33 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 34 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System General journal The general journal is a catchall type of journal in which transactions that don’t appropriately belong in any other journal show up. Many companies record interest income and dividends in the general journal. This journal is also used for adjusting and closing journal entries: ✓ Adjusting journal entries: One key reason you would adjust journal entries is to make sure the accounting books are recorded by using the accrual method. For example, on April 30, employees have earned but not yet been paid $5,000 in gross wages (the next payroll date is May 2). So to make sure that your company’s revenue and expenses are matched, you book an adjusting journal entry debiting wages expense account for $5,000 and crediting wages payable (or accrued wages) for $5,000. You also adjust journal entries to reclassify transactions. This occurs when the original transaction is correct but circumstances change after the fact and the transaction needs to be adjusted. For example, your company buys $1,000 of supplies on April 1, and the transaction is originally booked as supplies inventory. On April 30, an inventory of the supplies is taken. Only $800 of the supplies remain, so you have to debit your supplies expense account for $200 and credit supplies inventory for $200. ✓ Closing journal entries: You use this type of entry to zero out all t­emporary accounts. These accounts don’t make it into the financial statements. Revenue and expense accounts are temporary accounts, because their ­balances are adjusted to zero at the end of each ­accounting period (month or year). You then transfer the net amounts (net income or a net loss) to the balance sheet. (See Book IV, Chapter 2 for information about the income statement.) There are four closing journal entries: • You debit all revenue accounts and credit income summary for the same amount. Income summary is a temporary holding account you use only when closing out a period. • You credit all expenses and debit income summary for the same amount. • You either debit or credit income summary to reduce it to zero and take the same figure to retained earnings. Retained earnings r­ epresent the cumulative net income, less all dividends (distributions of profit) paid to owners since the company was formed. Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers Here’s an example: If in step one you credit income summary for $5,000 and in step two you debit income summary for $3,000, you now have a credit balance of $2,000 in income summary. So to reduce income summary to zero, you debit it for $2,000 and credit retained earnings for the same amount. • Finally, if the owners have paid themselves any dividends during the period, you credit cash and debit retained earnings. Honestly, you likely never have to prepare the first three closing entries ­ ourself because all accounting software systems perform this task for you y automatically. However, you do need to understand what goes on with the debits and credits when the books close. You have to do the fourth closing entry yourself. That’s because the automated accounting systems requires a manual journal entry for the dollar amount of the dividend. You clear out only temporary accounts with closing journal entries. Balance sheet accounts are permanent accounts. Until you cease using the account (for example, you close a bank account), no balance sheet accounts are zeroed out at closing. Checking out examples of common journal entries It’s time for you to review a few journal entries so the concepts related to them really come to life. First, keep in mind the general format of a journal entry, which is shown in Figure 3-5: Figure 3-5: The standard journal entry format. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ✓ The date of the entry is in the left column. ✓ The accounts debited and credited are in the middle column. ✓ The amounts are shown in the two right columns. 35 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 36 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Proper journal entries always list debits first followed by credits. See Book II, Chapter 2 for an explanation of debits and credits. Journal entries can have more than one debit and more than one credit. And the number of accounts debited and credited doesn’t have to be the same. For example, you can have five accounts debited and one account credited. However, the dollar amount of the debits and credits has to match. Consider an example of a journal entry for service income, which records cash and accrual income. You provide a service to your client, Mr. Jones, on May 15, giving him invoice #200 in the amount of $700 for services rendered. Before he leaves your office, he pays you $200 in cash with a promise to pay the remaining balance of $500 next week. The journal entry to record this transaction is shown in Figure 3-6. Figure 3-6: Recording service income. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Under the accrual method of accounting (see Chapter 4), both the cash receipts and the promise to pay the remaining balance have to be reported at the time the transaction takes place because the service has been rendered and the income has been earned. Every journal entry should have a brief description. It doesn’t have to be a ­paragraph but should be long enough that you or anyone else reviewing the journal entry can figure out why you made it. A common mistake is to make the description just a little too brief, forcing you to go back through the t­ ransaction to figure out why you made the journal entry. The description for the journal entry in Figure 3-6 (“To record invoice #200”) is brief but totally understandable. Take a look at one more journal entry before moving on. Suppose you borrow $5,000 from your bank on July 1. Your arrangement calls for you to pay $200 interest on July 31 and pay back the loan in full plus another $200 in interest on August 30. Figure 3-7 shows how your journal entries look from soup to nuts. Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers 37 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System Figure 3-7: Journalizing a loan transaction. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Bringing It All Together in the Ledger At this point you may be thinking, “Okay, the journals are the books of original entry, but what happens then? How do entries into these journals turn into financial statements?” That’s the topic of this section. The accounts and amounts debited or credited affect the company’s ledgers, as explained next. Realizing what a ledger is A ledger records applicable transactions taking place in a company during a particular accounting cycle. Picture a big book. Every page of the book has a title that corresponds with an account from the chart of accounts. For instance, page 1 may be titled “1001 Cash in Bank.” On this page, you’d list the total of the funds you deposited in your company checking account, as well as the total of all the withdrawals for a given period — say for a month. A business has one big dog ledger: the general ledger, which lists all ­transactions taking place in all the accounts during the specified a ­ ccounting period. You may also see subsidiary ledgers that list in detail transactions ­happening only in specific accounting circumstances. For example, the ­payroll subsidiary ledger lists all payroll transactions. The accounts ­receivable ­subsidiary ledger lists all customers owing your company money and the amount of their current outstanding balances. 38 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Posting to the ledgers When you post to the ledgers, you simply take accounts and numbers from transactions entered in the journals and record them in the correct ledger. If a subsidiary ledger is the first point of recording, the transaction e ­ ventually flows through the subsidiary ledger to the general ledger. For example, a ­customer sale on account first posts to the sales journal and then is reported in the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger under the customer’s name. Then that amount flows from the accounts receivable subsidiary ledger to the accounts receivable listing in the general ledger, combining with all other ­customers owing the business money to show a grand total of accounts ­receivable. Following with the same transaction, the combined total of all the transactions in the sales journal also posts to the sales listing in the general ledger. Until modern accounting software arrived, posting to the ledgers was a ­laborious process requiring the use of ledger paper with 14 columns. Fortunately, this practice has become a thing of the past because accounting software has become so affordable and easy to use. Most accounting software programs require no formal procedure to post to the ledgers. Every time you enter a transaction in a journal, it automatically posts to the correct ledger. However, proprietary accounting software (which means a business holds exclusive rights to use) may require the user to actively select the posting command. Viewing an example of a general ledger General ledgers vary according to the nature of the business, a company’s preferences, and the software used. Figure 3-8 shows a very simple partial general ledger for a small services company. It starts with a revenue account, “consulting fees,” and ends with an operating expense account, “bank charge.” Columns similar to the debit, credit, and balance columns in Figure 3-8 are used in earlier figures in this chapter. Here’s what some of the other columns mean: ✓ Type: The original nature of the transaction. ✓ Date: The day the transaction took place. ✓ No.: The identifying number from the journal of original entry. For ­example, 1008 is the company check number used to pay James Fine. ✓ Name: Whatever name you put in the journal of original entry. Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers 39 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System Figure 3-8: A partial general ledger. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ✓ Memo: Any explanation for the transaction that you put in the original entry. Using this section is important. If your journal entry involves four accounts, each account has this same memo information when it’s posted to general ledger. The memo notes make it much easier to ­understand why the entry was posted. Recognizing the purpose of the trial balance The trial balance is a listing of all the accounts in the general ledger and the balance of each account as of a certain date. The trial balance checks to make sure all debits equal credits. Any imbalance indicates the presence of an error that must be identified and corrected. Accountants also use the trial balance as a front-line tool to review the accuracy of the financial statements. To find out more about running trial balances, see Book III, Chapter 5. This chapter provides a short explanation, and an example trial balance. Suppose you run a trial balance, quickly scan it, and see that an expense account carries a balance that seems too high based on your professional judgment and knowledge of the company. You check the general ledger and see that a rent payment of $5,000 was posted to postage expense by mistake. You can then correct the error before producing any financial statements. Figure 3-9 shows an example of a partial trial balance. 40 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Figure 3-9: A partial trial balance. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Accounting software shouldn’t allow a user to enter a transaction that’s out of balance. (Out of balance means that the total dollar amount of debits doesn’t equal credits.) If an out-of-balance transaction occurs, the software has a serious bug that you need to report to the developer. Putting Accounting Software to Work for You A bewildering array of accounting software is available today for small- and medium-sized businesses. (Larger corporations tend to develop their own computer-based accounting systems or hire a programmer to develop ­specialized software.) Today a business can select from a wide array of accounting software ­ ackages. Two popular choices for small businesses are QuickBooks and Sage p Peachtree. A quick Internet search for “accounting software” can help you track down additional options. Unless your company has its own custom Chapter 3: Using Journal Entries and Ledgers accounting software and information technology (IT) staff, consider seeking the advice and assistance of an outside consultant in choosing, implementing, upgrading, and replacing accounting software. If you don’t have the funds to hire a consultant, here’s some free advice: ✓ Choose your accounting software very carefully. Switching to a different accounting program later is a major headache, so choose software that serves your current needs and provides room to grow. ✓ In evaluating accounting software, you and your accountant should ­consider three main factors: ease of use; whether it has the p ­ articular features and functionality you need; and the likelihood that the vendor will continue in business and be around to update and make ­improvements to the software. ✓ Make sure your accounting software leaves good audit trails, which you need for management control, for your CPA when auditing your financial statements, and for the IRS when it decides to audit your income tax returns. The lack of good audit trails looks very suspicious to the IRS. See Book IX for a discussion of audits. ✓ Pay attention to security features and best practices. You need very tight controls over all aspects of using the accounting software and who is authorized to make changes in any of the modules. Online accounting systems that permit remote input and access over the Internet or a local area network with multiple users present ­special ­security problems. Think twice before putting any part of your ­accounting system online (and if you do, institute airtight controls). More and more businesses seem to be switching to the cloud for doing more and more of their accounting tasks. The cloud consists of a network of offsite computer servers that users connect with over the Internet. You can choose to do your accounting in the cloud or use the cloud simply as the backup storage location for your accounting records. Cloud providers offer a wide variety of accounting and business software and services that are too ­numerous to discuss here. Cloud servers have a reputation of being very secure, but you still need very strong controls over the transmission of accounting information to and from the cloud. 41 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 42 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System Chapter 4 Choosing an Accounting Method In This Chapter ▶ Getting clear on the cash and accrual methods of accounting ▶ Walking through other types of accounting ▶ Finding out about FASB’s conceptual framework T o perform accounting tasks, you must choose to follow either of two methods: cash basis or accrual basis. In addition, you can approach accounting in several ways, depending on the nature of your business and the audience that reads your financial statements. For example, businesses use accounting to track transactions and keep investors informed; and their managers use accounting to make better decisions. Not-for-profit organizations primarily use accounting to help with budgeting and grant proposals. Accountants serving government agencies must also focus on budgeting while providing citizens and government agencies and officials with the information they need. This chapter explains the differences between cash and accrual basis accounting, describes the various ways accounting is used, and introduces you to the Financial Accounting Standards Board’s Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts. (If you aren’t familiar with the FASB, check out Book IV, Chapter 1.) This chapter walks you through some of these concepts, tying them into material you encounter in Books IV and V. Distinguishing between Cash and Accrual Basis You can’t keep books unless you know how you want to go about doing so. The two basic accounting methods are cash-basis accounting and accrual accounting. The key difference between these two accounting methods is the point at which you record revenue and expenses in your books. If you choose 44 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System cash-basis accounting, you record transactions only when cash changes hands. If you use accrual accounting, you record revenue when it’s earned, and expenses when they’re incurred — regardless of when cash changes hands. The accrual method of accounting allows you to apply the matching principle of your transactions. This principle states that revenue should be matched with the expenses incurred to produce the revenue, regardless of when cash changes hands. Suppose your company buys products to sell from a vendor but doesn’t actually pay for those products for 30 days. If you’re using cash-basis accounting, you don’t record the purchase until you actually lay out the cash to the vendor. If you’re using accrual accounting, you record the purchase when you receive the products, and you also record the future debt in an account called accounts payable. The following sections describe each method in greater detail along with the pros and cons of each method. The cash basis Cash-basis accounting couldn’t be easier. You record revenue when the company receives payments, and you record expenses when the company pays for something. The cash basis is essentially posting accounting transactions by using your checkbook. Your checkbook deposits for March represent March revenue, and your checks and debits for March are your expenses for that month. Missing the matching principle The ease of using the cash method is more than offset by the fact that the method fails to match revenue to the expenses the company incurs to earn that revenue. Because the matching principle isn’t applied, cash basis financial statements usually don’t present as accurate a picture of how the business is performing as accrual method financial statements do. Consider an example. Let’s say ABC Corp. has revenue of $40,000 and expenses totaling $15,000 associated with that revenue in April. $20,000 of the revenue was received in cash, and the rest is on account. ABC Corp. paid cash for the entire $15,000 of expenses. Using the cash method, ABC Corp.’s net income for April is $5,000 ($20,000 cash revenue less $15,000 cash expenses). But that $5,000 of net income grossly under-represents the volume of activity the company had during the month. The figures could be just as wildly inaccurate if the company didn’t pay any of its expenses and had cash sales of $30,000 — or for any other scenario involving the use of cash changing hands as a criteria for recording net income. Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method 45 Adjusting the accounting records Book I Some small businesses use the cash method because they have little activity in the way of accounts receivable or payable. But the vast majority of businesses use the accrual basis, explained in the next section. Setting Up Your Accounting System Because of the issues companies encounter with the cash method, most companies eventually switch to the accrual method. Often a financial statement user insists on the change. Maybe you’re applying for a company bank loan. Your banker believes that the accrual method provides a more accurate view of your profit and loss each period. So, the banker asks to see prior year financials using the accrual period. As you can imagine, adjusting your accounting records from the cash to accrual method may take a lot of work. You must review every revenue and expense transaction and determine whether the accounting needs to be changed. The accrual basis Using the accrual method of accounting, you record revenue when it’s earned and realizable, and you record expenses when they’re incurred — regardless of whether or when money changes hands. Wondering what the criteria are for revenue to be earned and realizable? The earned criterion is satisfied when the vendor satisfactorily performs on its contract with the customer. Typically, revenue is considered earned when the vendor delivers the goods or services. Realizable means that the company has good reason to believe it will receive payment; for example, the customer swipes his debit card and enters his PIN. A company can choose the criteria it uses to recognize revenue in the accounting records. The timing of revenue recognition depends on the company’s industry, as well as the firm’s history of receiving payments. A company may recognize revenue when it sends an invoice, or when it ships the goods. Even if the revenue is realizable, the point at which the revenue is considered earned can vary. The accrual method takes cash out of the equation, because money changing hands doesn’t determine whether you recognize a transaction. As a result, a company using the accrual method has an accounts receivable, which shows how much money customers owe to the business, and an accounts payable, which shows all the money a company owes to its vendors. 46 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System The statement of cash flows, discussed briefly at the end of this chapter and explained in detail in Book V, Chapter 2, is the accountant’s bridge between the cash and accrual methods of accounting. That’s because the statement of cash flows shows cash sources and uses — an aspect missing from the accrual method. Therefore, it gives the users of the financial statements a chance to look beyond and through the accrual-based numbers. Sorting through Standards for Other Types of Accounting Financial accounting is the process of compiling accounting transactions to create financial statements. Here are some other types of accounting that accountants may perform: ✓ Managerial accounting: Creating internal accounting reports that company managers use to make decisions. ✓ Not-for-profit accounting: Generating financial statements for not-forprofit entities, using a different set of financial reports. Not-for-profit firms raise money from donations, grants, and other sources. They don’t produce revenue primarily from selling a product or service. As a result their financial reports are different. ✓ Governmental accounting: Like not-for-profits, governments (federal, state, and local) have a unique method for creating financial statements. ✓ International accounting: The global accounting industry is attempting to create a single set of accounting standards for international commerce. At this point, countries outside the U.S. maintain at least some accounting rules that are different. As a result, rules for foreign entities may differ from U.S. accounting rules. The following sections explore these different areas of accounting more closely. If you work in an accounting field other than financial accounting, you must follow standards different from (or in addition to) those discussed in Book IV, Chapter 1. Other organizations besides the financial accounting standard-setters give official guidance on how to prepare financial statements and reports. For example, instead of following generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), governmental entities follow procedures set up by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB). Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method To find out more about financial accounting, see “Considering the Conceptual Framework of Financial Accounting,” later in this chapter. The next few sections give you the lowdown on other types of accounting and note who provides guidance to accountants in these fields. Managerial accounting Managerial accountants provide economic and financial information for the internal users of financial statements, such as a company’s department heads, shift leaders, and human resources department. For example, human resources personnel use managerial accounting reports to make sure they have the right mix of employees to maintain a smooth-running operation. Additionally, managerial accounting reports measure quality, performance, and how close each department or business unit comes to meeting its goals. They also measure managerial effectiveness and efficiency. In order to be useful, managerial reports are issued frequently — sometimes daily. There’s no messing around! Other times, accounting staff prepare and distribute the reports the day after a reporting period ends. For internal reporting to management, the rules are similar to those you follow when playing horseshoes — getting close is often good enough. Because managerial reports are used only internally, no regulatory bodies or other outside agencies mandate how managerial accountants do their job. Instead, managerial accountants look to the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA) for guidance on carrying out their accounting duties. The managerial accountant code of ethics is contained in the Standards of Ethical Conduct for Management Accountants. For more information, check out the IMA website at www.imanet.org. To find out more about managerial accounting, see Managerial Accounting For Dummies by Mark P. Holtzman, CPA (Wiley). Not-for-profit accounting Not-for-profit businesses are run for the public good — not driven by any profit motive. You may consider these entities to be “mission-driven.” Every not-for-profit has a particular mission that it has defined for itself. These types of organizations include hospitals, schools, religious organizations, and charitable agencies. Net income of an exempt organization isn’t taxed federally. To qualify for exempt status in the United States, an organization fills out an application package that must be approved by the Internal Revenue Service. After the approval process, which can take months, the organization is then exempt from paying the normal taxes levied on a for-profit business by the federal government. 47 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 48 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System The not-for-profit accountant’s job involves two important components (in addition to the typical accounting duties): preparing budgets and preparing the financial information for grant applications. Budgets are crucial because the organization needs to be able to predict what amount of money it must obtain through grants, donations, and fundraising efforts in order to serve the organization’s purpose. Not-for-profits apply for grants awarded by government entities and private foundations. The purpose of the grant should fit the organization’s mission. If your organization promotes trails for hiking and biking, you might apply for a grant to encourage kids to walk or ride bikes to school. The entity awarding the grant requests financial information in the grant application and insists that the not-for-profit report periodically on how the funds are used. Wondering if not-for-profits also have to report by using accrual basis accounting and according to FASB and GAAP standards? As explained in Book IV, Chapter 1, the FASB Accounting Standards Codification is the source of authoritative GAAP to be applied by all nongovernmental entities. So the answer is yes, a not-for-profit follows FASB and GAAP unless an FASB pronouncement specifically excludes not-for-profits. One difference in keeping the books for profit seeking versus not-for-profit organizations is that not-for-profits use fund accounting, which groups accounting transactions together into funds or accounts that share a similar purpose. This way, the organization has a better idea of the resources it has available for each specific function. If not-for-profit accounting interests you, check out Nonprofit Bookkeeping & Accounting For Dummies by Sharon Farris (Wiley) for much more information about this field. Governmental accounting Governmental accountants work for city, county, state, and federal government agencies. Their job is similar to the not-for-profit accountant’s job because they deal with budgets and government agencies that have no profit motive. Budgeting is important because budgets serve as the primary tool in allocating governmental cash sources to urban, suburban, and rural parts of the communities served. At the city, county, or state level, the cash comes in from sources such as ad valorem (property) taxes; funding from the federal government such as for schools, streets, and roads; interdepartmental governmental transfers; fines and forfeitures; sales and use tax; licenses and permits; and municipal bond issuances. Funds are then appropriated to cover costs. The appropriations are either approved or disapproved during the setting of the budget. Finally, disbursements are made throughout the fiscal year for approved budget items. Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method Governmental accountants also prepare financial statements that are open to the general public. The financial statements must show accountability to citizens while pursuing the goals of efficiency and effectiveness. The financial statements are also used by external users to decide whether to invest in the municipality’s bond issuances. The regulatory authority for governmental accountants is the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB). You can find out more information about GASB at www.gasb.org. International accounting International accountants work for multinational businesses performing financial and managerial accounting, tax return preparation, and auditing. (Auditing is the process of investigating financial information prepared by someone else to see whether it’s stated fairly. Check out Book IX for additional details.) They should be familiar with the legal regulations and standards of the countries in which their employers conduct business. International accountants have to deal with foreign currency translations, such as how many U.S. dollars (USD) equal how many euros (EUR). They also manage two special risks: ✓ Expropriation: The seizure of company assets by the host government ✓ Blocked funds: When the host government doesn’t allow any company funds to be repatriated to the United States An important organization for international accountants is the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), whose website is www.iasb.org. The IASB is currently working in tandem with the FASB to provide comparability between the accounting standards — in other words, to bring U.S. and international GAAP together. This process is referred to as harmonization, and the purpose is to develop a single set of global accounting standards that will provide high quality, transparent, and comparable financial statement reporting. Considering the Conceptual Framework of Financial Accounting Accounting dates back to the Stone Age as a way of figuring out the supply and demand of commerce. Long before people had stores and cash registers, they had to have some way of ensuring an equitable trade of goods for goods or goods for service. Also, accounting was put to use as far back as the Holy Roman Empire (and probably even earlier) to make sure that all subjects to the empire were paying their assessed taxes. 49 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 50 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System As noted in Book IV, Chapter 1, accounting standards were virtually nonexistent until the Great Depression of 1929. And it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) began the process of spelling out a framework of financial accounting concepts. The FASB organizes its conceptual framework in Statements of Financial Accounting Concepts or Concept Statements. (Accountants use the abbreviation CONs to refer to them.) Financial accounting textbooks usually mention these CONs only in passing. However, if you’re new to the wonderful world of financial accounting, these concepts can give you a firm foundation for understanding financial accounting. The information that comes next provides general background on why financial accounting standards work the way they do and what they attempt to accomplish. The following sections provide the condensed version of the concepts, but first you find out about what financial accounting is attempting to accomplish. The objective of financial reporting The purpose of financial accounting is to classify and record all accounting events taking place during the course of a company’s business. These events include earning revenue, paying bills, bringing in gains, and incurring losses. The results of all these events are arranged on the correct financial statement (the balance sheet, income statement, and/or statement of cash flows) and reported to the external users of the financial statements. External users include investors, creditors, banks, and regulatory agencies such as the IRS and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Characteristics of accounting information Besides organizing accounting events into financial statements, financial accountants serve the needs of external users by delivering the information they need in a format they understand. To achieve this goal, accountants must produce financial reports that exhibit the following characteristics: ✓ Understandability: The information on the financial statement has to be understandable to people not privy to the internal workings of the business. The financial information must be laid out in a fashion so that users with a reasonable understanding of the business world (and a willingness to do research on specific topics as needed) can ferret out all important accounting facts about the business. Chapter 4: Choosing an Accounting Method ✓ Relevance: This characteristic means that the financial statements give the users enough info so they can form opinions about the final outcome of events that took place in the past and how any present or future events are likely to shake out. Also, the financial statements should give the users enough info so that they can tell whether any opinions they made about future events that have now come to fruition were indeed correct. ✓ Reliability: Financial statements aren’t worth the paper they’re written on unless the information they present is verifiable, neutral, and materially correct. For example, if the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2) shows $10 million of sales, that $10 million should represent sales that actually took place, not projections (or what company management wants the users to think occurred). ✓ Comparability: Comparability means the quality of the information is such that users can identify differences and similarities among companies they’re evaluating — or among different financial periods for the same company. For example, users need to know what method(s) the companies are using to depreciate assets. Without this knowledge, the users can’t accurately evaluate the relative worth of one company over the other. (Head over to Book III, Chapter 1 for more on depreciation.) ✓ Consistency: Consistency means the company uses the same accounting treatment for the same type of accounting transactions — both within a certain financial period and among various financial periods. Doing so allows the user to know that the financial accountant isn’t doing the accounting equivalent of comparing apples to oranges. Elements of the financial statements A primary focus of accounting in the business world centers on the proper preparation of financial statements: the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows. Accountants can’t just stick accounting transaction data on the statements wherever they feel like. GAAP contains many, many rules that dictate how information must be organized on the statements (see Book IV, Chapter 1). These rules pertain to both how the financial accountant shows the accounting transactions and on which financial statements the information relating to the transactions appears: ✓ Income statement: This financial statement shows the results of business operations consisting of revenue, expenses, gains, and losses for a specific period of time. The end product is net income or net loss. Here are the basic facts on the four different income statement components: • Revenue: Gross receipts earned by the company selling its goods or services • Expenses: The costs to the company to earn the revenue 51 Book I Setting Up Your Accounting System 52 Book I: Setting Up Your Accounting System • Gains: Income from non-operating-related transactions, such as selling a company asset • Losses: The flip side of gains, such as losing money when selling the company car A lot of non-accountants call the income statement a statement of profit or loss or simply a P&L. These terms are fine to use because they address the spirit of the statement. ✓ Balance sheet: The balance sheet, which is compiled as of a certain date, has three sections: assets, liabilities, and equity. Standing on their own, these sections contain valuable information about a company. However, a user has to see all three together on the balance sheet to form an opinion about the company’s operations. Here are the basics about each balance sheet component: • Assets: Resources owned by a company, such as cash, equipment, and buildings • Liabilities: Debt the business incurs for operating and expansion purposes, such as accounts payable, accrued wages and notes payable • Equity: The amount of ownership left in the business after deducting total liabilities from total assets ✓ Statement of cash flows: The statement of cash flows, created as of a specific date, contains certain components of both the income statement and the balance sheet. The purpose of the statement of cash flows is to show cash sources and uses during a specific period of time — in other words, how a company brings in cash and what the company uses that cash for. Financial statement measurements Communicating via the financial statements with parties interested in the business requires the measurement of all accounting transactions. Measurement refers to the fact that every accounting event must have a cost or a value in order to be recognized on the financial statements. You may be confused about the difference between cost and value. Well, you’re not alone. This issue can be thorny even among seasoned financial accountants. Depending on their nature, accounting transactions may be recorded in different ways. If a transaction is recorded at historic cost, it shows how much the company paid in cash or assumed in debt during the transaction. Net realizable value (NRV) can also be used, which is the amount of cash a business anticipates receiving from an asset in the normal course of business — after factoring in any related costs. You find all sorts of good information about historic cost in Book IV, Chapter 3. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions Check out www.dummies.com/extras/accountingaio for additional g­ uidance on documenting your accounting transactions to leave a clear audit trail. In this book… ✓ Manage your accounting system to keep your books balanced. When you post entries to your accounting system, the total dollar amount of debit entries should equal the credits. ✓ Track purchases, inventory, and costs, and pay your bills. For many companies, inventory is the largest cost to the business. ✓ Record sales in cash and store credit and account for discounts, returns, and bad debt. These practices help you calculate total sales correctly. ✓ Prepare and record payroll to keep track of employee compensation and payroll taxes. This is one of the most complex areas of accounting, because the rules on tax withholdings frequently change. ✓ Account for Social Security and Medicare taxes, unemployment compensation, and workers’ compensation. Each of these entities receives reports on payroll withholdings, along with payments. Chapter 1 Keeping the Books In This Chapter ▶ Getting a bird’s-eye view of accounts and transactions ▶ Establishing your accounting system ▶ Closing out at the end of a period I ndividuals can get along quite well without much bookkeeping — but the exact opposite is true for a business. In addition to facilitating dayto-day operations, a company’s bookkeeping system serves as the source of information for preparing its periodic financial statements, tax returns, and reports to managers. The accuracy of these reports is critical to the business’s survival. Obviously, then, business managers have to be sure that their company’s bookkeeping and accounting system is dependable and up to snuff. This chapter shows you what bookkeepers and accountants do, mainly so you have a clear idea of what it takes to be sure that the information coming out of the accounting system is complete, timely, and accurate. Analyzing the Effect of Business Transactions This section walks you through the basics of bookkeeping, including the rule of debits and credits and why proper debiting and crediting keeps the financial statements in balance. You also discover the five steps for entering transactions into the accounting records. Modern financial accounting is a double-entry system: For every entry into the company accounting records, there has to be an opposite and equal entry. In other words, debits must always equal credits. Technology gives you a hand here: No accounting software package worth its salt will let you enter an unbalanced transaction into the accounting books. For more about double-entry accounting, see Book I, Chapter 2. 56 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Revisiting the fundamental accounting equation The fundamental accounting equation (also known as the accounting equation or the balance sheet equation) requires that all transactions balance when they’re posted to the equation. It demands that Assets = Liabilities - Owners’ equity A truncated version of this equation states Net assets = Owners’ equity This version of the equation just moves liabilities over to the other side of the equal sign; net assets are all assets minus all liabilities. Before you can begin to set up your accounts and enter transactions, you must have a good grasp of this fundamental accounting equation, discussed in Book I, Chapter 1. Getting familiar with accounts As an accountant within a business, you summarize accounting transactions into accounts that you use to create financial reports. Every account your company uses is annotated in a list called the chart of accounts — a list of all accounts and each account’s balance. The business uses that chart of accounts to record transactions in its general ledger. The general ledger is the record of all financial transactions within the company during a particular accounting cycle. You find out more about the general ledger later in this chapter. The chart of accounts isn’t a financial report. It’s merely a list of all accounts you’ve previously set up to handle the company transactions. When you’re “doing the books,” as the saying goes, you record your normal business transactions by using accounts you set up in the chart of accounts. Each account in the chart of accounts has a unique account number. Regardless of what accounting software package your company uses, the numbering sequence is pretty much set in stone to ensure consistency among companies and among their financial reports. For more about creating and using a chart of accounts, see the section “Categorizing your financial information: The chart of accounts,” later in this chapter. Chapter 1: Keeping the Books 57 Defining debits and credits When you understand the basics of accounts and the chart of accounts (see the previous sections), it’s time to find out about the mechanism of journal entries, which you use to enter financial information into the company’s accounting records. Writing journal entries is a major area of concern for small business owners, first-year accounting students, and students who are taking accounting only because it’s required for a business degree. The logistics of presenting the journal entry don’t cause the concern; instead, the worry is how to figure out which account is debited and which is credited. Assets and expense accounts are increased with a debit and decreased with a credit. Liability, revenue, and equity accounts are just the opposite: These accounts are credited for increases and debited for decreases. There are some occasional exceptions to these rules. Book III, Chapter 6 explains accumulated depreciation. This account is a contra-asset, which is an asset account that’s increased by crediting. Accumulated depreciation is the only exception discussed in the book. Knowing more about the transaction methodology Before you enter an event into a business accounting system, you have to consider the transaction methodology, a five-step process for deciding the correctness of whatever entry you’re preparing. After you get into the financial accounting rhythm, this process becomes an automatic analysis you do by rote. Here are your five considerations: ✓ What’s going on? This question addresses the precipitating event for the entry. For example, did the company buy a new piece of business equipment or sell some product to a customer? ✓ Which accounts does this event affect? Is the account an asset, liability, owners’ equity, revenue, or expense? Assets would definitely be affected by the purchase of business equipment, and revenue would be affected by a customer sale. To get started, ask yourself whether the event affects cash. Cash is often the most-used account in your chart of accounts. ✓ How are the accounts affected — by a debit or credit? Looking back to your rules of debits and credits, buying assets adds to the account, so it’s a debit. Making a sale adds to a revenue account, so it’s a credit. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 58 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions ✓ Do all debits for an entry equal all credits for the same entry? Think about the fundamental accounting equation discussed earlier in this chapter. Every debit requires an equal credit. ✓ Does the entry make sense? Do the accounting actions you take match the facts and circumstances of the business event? For example, although the net effect on the books is the same, you can’t credit an expense to record revenue. Each type of account in your chart of accounts has a normal balance. The normal balance is the balance you expect to see in an account at any point in time. For example, you debit cash (an asset balance) to increase it. A normal balance for an asset account is a debit balance. If you review account balances and notice a credit balance in cash, that fact should be a red flag. It may mean that your cash account is overdrawn or negative. Managing Your Bookkeeping and Accounting System Too many business managers and owners ignore their bookkeeping and accounting systems or take them for granted — unless something goes wrong. They assume that if the books are in balance, everything is okay. Book I, Chapter 2 covers exactly what having “books in balance” means — it does not necessarily mean that everything is okay. To determine whether your bookkeeping system is up to snuff, check out the following sections, which provide a checklist of the most important elements of a good system. Categorizing your financial information: The chart of accounts Suppose that you’re the accountant for a corporation and you’re faced with the daunting task of preparing the annual federal income tax return for the business. For instance, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires that you report the following kinds of expenses (and this list contains just the minimum!): ✓ Advertising ✓ Bad debts ✓ Charitable contributions ✓ Compensation of officers ✓ Cost of goods sold Chapter 1: Keeping the Books 59 ✓ Depreciation ✓ Employee benefit programs ✓ Interest ✓ Pensions and profit-sharing plans ✓ Rents ✓ Repairs and maintenance ✓ Salaries and wages ✓ Taxes and licenses You must provide additional information for some of these expenses. For example, the cost of goods sold expense is determined in a schedule that also requires inventory cost at the beginning of the year, purchases during the year, cost of labor during the year (for manufacturers), other costs, and inventory cost at year-end. Where do you start? For each category of information that you must report, you need an account, a record of the activities in that category. An account is basically a focused history of a particular dimension of a business. Individuals can have accounts, too — for example, your checkbook is an account of the cash inflows and outflows and the balance of your checking account (assuming that you remember to record all activities and reconcile your checkbook against your bank statement). You probably don’t keep a written account of the coin and currency in your purse, wallet, or pockets, but a business needs to keep track of all its cash no matter where it is. An account serves as the source of information for preparing financial statements, tax returns, and reports to managers. The formal index or list of all accounts is referred to as the chart of accounts. The chart of accounts, even for a relatively small business, often contains more than 100 accounts. Larger business organizations sometimes need thousands of accounts. The larger the number, the more likely that the accounts have number codes according to some scheme — for example, all assets may be in the 100 to 300 range, all liabilities in the 400 to 500 range, and so on. To get the lowdown on how to set up your chart of accounts, check out Book I, Chapter 2. Standardizing source document forms and processing procedures Just as humans need a constant circulation of blood to live, businesses need a constant flow of paperwork. Even in this modern age of the Internet, electronic communication, and computers, a business generates and depends on a lot of paperwork. And much of this paperwork is used in the accounting Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 60 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions process. Placing an order to buy products, selling a product to a customer, determining the earnings of an employee for the month — virtually every business transaction needs paperwork, generally known as source documents. Source documents serve as evidence of the terms and conditions agreed upon by the business and the other person or organization that it’s dealing with. Both parties receive some kind of source document. For example, for a sale at a cash register, the customer gets a sales receipt, and the business keeps a running record of all the transactions in the register, which can be printed later if need be. Clearly, an accounting system needs to standardize the forms and procedures for processing and recording all normal, repetitive transactions and should control the generation and handling of these source documents. From the bookkeeping point of view, these business forms and documents are very important because they provide the input information needed for recording transactions in the business’s accounts. Sloppy paperwork leads to sloppy accounting records, which won’t do when the time comes to prepare tax returns and financial statements. If you’re the owner of a small business, you may want to check out an office supply store to see the kinds of forms that you can buy right off the shelf. You can find many basic forms and documents for executing and recording business transactions. Also, computer accounting software packages today include templates for most business forms and source documents that a business needs. Hiring competent personnel A business shouldn’t be penny-wise and pound-foolish: What good is meticulously collecting source documents if the information on those documents isn’t entered into your system correctly? You shouldn’t try to save a few bucks by hiring the lowest-paid people you can find. Bookkeepers and accountants, like all other employees in a business, should have the skills and knowledge to perform their functions. Here are some guidelines for choosing the right people to enter and control the flow of your business’s data and for making sure that those people remain the right people: ✓ Education and experience: The ideal level of education and experience for accounting employees can vary greatly. Many accountants in large business organizations have a college degree with a major in accounting. This may also be the case for the head of accounting in a smaller company. However, as you move down the pay scale in any accounting department, you find that more and more employees don’t have a college degree and perhaps don’t even have any courses in Chapter 1: Keeping the Books 61 accounting — they learned bookkeeping methods and skills through on-the-job training. Even without the degree or formal accounting coursework, these employees can be very effective workers. ✓ Certifications: When hiring higher-level accountants in a business organization, decide whether they should be certified public accountants (CPAs). Larger businesses insist on this credential, along with a specific number of years’ experience in public accounting. Until recently, the other main professional accounting credential was the CMA, or certified management accountant, sponsored by the Institute of Management Accountants (IMA). The CMA credential is American born and bred. In contrast, the Chartered Global Management Accountant, or CGMA designation, is co-sponsored by the American Institute of CPAs and the British Chartered Institute of Management Accountants. Unlike the CPA license, the CMA and CGMA designations recognize professional achievement and experience but the government doesn’t regulate these credentials. A business is prudent to require the CPA, CGMA, or CMA credential for its chief accountant (who usually holds the title of controller). Alternatively, a business could regularly consult with a CPA in public practice for advice on its accounting system and on any accounting problems that arise. Note: For bookkeepers, the American Institute of Professional Bookkeepers sponsors the Certified Bookkeeper designation. For more information, visit www.AIPB.org. ✓ Continuing education: Bookkeepers and accountants need continuing education to keep up with changes in the income tax law and financial reporting requirements, as well as changes in how the business operates. Ideally, bookkeepers and accountants should be able to spot needed improvements and implement these changes — to make accounting reports to managers more useful. Fortunately, many courses are available at reasonable costs for keeping up on the latest accounting developments. Many continuing education courses are available on the Internet, but be cautious and check out the standards of any Internet course. States generally require that CPAs in public practice take 30 to 40 hours per year of continuing education to keep their licenses. ✓ Integrity: Possibly the most important quality to look for is also the hardest to judge. Bookkeepers and accountants need to be honest people because of the control they have over your business’s financial records. Conduct a careful background check when hiring new accounting personnel. Small-business owners and managers have closer day-in and day-out contact with their accountants and bookkeepers, which can be a real advantage — they get to know their accountants and bookkeepers on a personal level. Even so, you can find many cases where a trusted bookkeeper has embezzled many thousands of dollars over the years. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 62 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Enforcing strong internal controls Any accounting system worth its salt should establish and vigorously enforce effective internal controls — additional forms and procedures over and above what’s strictly needed to move operations along. These additional procedures serve to deter and detect errors (honest mistakes) and all forms of dishonesty by employees, customers, suppliers, and even managers. Unfortunately, many businesses pay only lip service to internal controls; they don’t put into place good internal controls, or they don’t seriously enforce their internal controls (they just go through the motions). Internal controls are like highway truck weigh stations, which make sure that a truck’s load doesn’t exceed the limits and that the truck has a valid license plate. You’re just checking that your staff is playing by the rules. For example, to prevent or minimize shoplifting, most retailers now have video surveillance and security tags in or on their merchandise. Likewise, a business should implement certain procedures and forms to prevent (as much as possible) theft, embezzlement, kickbacks, fraud, and simple mistakes by its own employees and managers. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (see Book IV, Chapter 1) requires that public companies establish and enforce a special module of internal controls over their external financial reporting. Although the law applies only to public companies, some accountants worry that the law’s requirements will have a trickle-down effect on smaller private businesses as well. Unlikely, but it could happen. Many small-business owners tend to think that they’re immune to insider embezzlement and fraud, especially when the people working for them are family members or friends. Yet, in fact, many small businesses are hit very hard by fraud and usually can least afford the consequences. To protect your business, you should put checks and balances into place to discourage dishonest practices and to uncover any fraud and theft as soon as possible. Following are five common internal control procedures you can implement to protect your business: ✓ Require a second signature on cash disbursements over a certain dollar amount. ✓ Match receiving reports based on actual counts and inspections of incoming shipments with purchase orders before cutting checks for payment to suppliers. ✓ Require both a sales manager’s and another high-level manager’s approval for write-offs of customers’ overdue receivable balances (that is, closing the accounts on the assumption that they won’t be collected), including a checklist of collection efforts that were undertaken. Chapter 1: Keeping the Books 63 ✓ Require that auditors or employees who don’t work in the warehouse take surprise counts of products stored in the company’s warehouse and compare the counts with inventory records. ✓ Require mandatory vacations by every employee, particularly bookkeepers and accountants, during which time someone else does that person’s job (because a second person may notice irregularities or deviations from company policies). Wrapping Up with End-of-Period Procedures Suppose that all transactions during the year have been recorded correctly. Your job’s done, right? Not so fast. Now you need to tidy up those books and prepare end-of-period reports for management. As you perform those tasks, you also need to be sure to leave clear audit trails and keep an eye out for any out-of-the-ordinary events or developments. The following sections explain what you need to do to wrap it up at the end of a period. Tidying up the books Prior to creating financial reports, you need to perform a couple additional procedures at the end of the period to make sure that the accounts are correct and complete. After those steps are completed, you can prepare financial statements and income tax returns for the year. Two main things have to be done at the end of the period: ✓ Record routine adjusting entries: Depreciation expense isn’t a transaction that’s recorded during the day-to-day bookkeeping process. (Book IV, Chapter 2 explains depreciation expense.) You record depreciation expense at the end of the accounting period (a month or a year). Accountants refer to these transactions as adjusting entries. The purpose of adjusting entries is to update and correct the revenue, income, expense, and loss accounts for the year. Year-end adjusting entries are necessary to have correct balances for determining profit for the period. ✓ Review other business developments that may affect the accuracy of the accounts: Assume a company discontinued a product line during the year. The product line’s remaining inventory may have to be removed from the inventory asset account, with a corresponding loss recorded in the period. Maybe the company settled a long-standing lawsuit, and the amount of damages needs to be recorded. Layoffs and severance packages are another example of what the chief accountant needs to look for before preparing financial reports. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 64 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions End-of-period accounting procedures can stir up controversy of the heateddebate variety. These procedures require that the accountant make decisions and judgment calls that upper management may not agree with. For example, the accountant may suggest recording major losses that would put a big dent in profit for the year or cause the business to report a loss. The outside CPA auditor (assuming that the business has an independent audit or review of its financial statements) often gets in the middle of the argument. These kinds of debates are precisely why business managers need to know some accounting. Leaving good audit trails Good accounting systems leave good audit trails. An audit trail is a clear-cut, well-marked path of the sequence of events leading up to an entry in the accounts. The trail starts with the source documents and follows through to the final posting in the accounts. You create an audit trail so an auditor can “re-walk” the path. Even if a business doesn’t have an outside CPA do an annual audit or review, the accountant has frequent occasion to go back to the source documents. An accountant may need to either verify certain information in the accounts or reconstruct the information in a different manner. Suppose that a salesperson is claiming some suspicious-looking travel expenses; the accountant would probably want to go through all this person’s travel and entertainment reimbursements for the past year. If the IRS comes in for a field audit of your income tax return, you’d better have good audit trails to substantiate all your expense deductions and sales revenue for the year. The IRS has rules about saving source documents for a reasonable period of time and having a well-defined process for making bookkeeping entries and keeping accounts. Think twice before throwing away source documents too soon. Also, ask your accountant to demonstrate and lay out for your inspection the audit trails for key transactions, such as cash collections, sales, cash disbursements, and inventory purchases. Even computer-based accounting systems recognize the importance of audit trails. Well-designed computer programs provide the ability to backtrack through the sequence of steps in the recording of specific transactions. Staying alert for unusual events and developments Business managers should encourage their accountants to stay alert to anything out of the ordinary that may require attention. Suppose that the accounts receivable balance for a customer is rapidly increasing — that is, the customer is buying more and more from your company on credit but isn’t paying for these purchases quickly. Maybe the customer has switched more Chapter 1: Keeping the Books 65 of his company’s purchases to your business and is buying more from you only because he is buying less from other businesses. That’s a good thing. But maybe the customer is planning to stiff your business. Or maybe the customer is planning to go into bankruptcy soon and is stockpiling products before the company’s credit rating heads south. Two really bad things. Don’t forget internal time bombs: A bookkeeper’s reluctance to take a vacation could mean that she doesn’t want anyone else looking at the books. To some extent, accountants have to act as the eyes and ears of the business. Of course, that’s one of the main functions of a business manager as well, but the accounting staff can play an important role. Designing truly useful reports for managers End-of-period reports include the three biggies — income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement — and any other financial statements management requires to do its job. End-of-period reports, when done well, serve several purposes: ✓ Fulfill government financial reporting requirements ✓ Keep investors posted on the financial state of the business ✓ Keep management posted on the financial state of the business ✓ Provide financial information to managers, so they can make better business decisions To produce clear and useful reports, consult management to assess its needs. Proactively study the manager’s decision-making responsibilities and provide the information that is most useful, presented in the most easily digestible manner. In designing the chart of accounts, keep in mind the type of information needed for management reports. To exercise control, managers need much more detail than what’s reported on tax returns and external financial statements. Consider regrouping expenses into different categories for management decision-making analysis. A good chart of accounts looks to both the external and the internal (management) needs for information. So what’s the answer for a manager who receives poorly formatted reports? Demand a report format that suits your needs! Books IV and V cover financial reporting in detail. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 66 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Chapter 2 Tracking Purchases In This Chapter ▶ Tracking inventory and monitoring costs ▶ Keeping your business supplied ▶ Paying your bills I n order to make money, your business must have something to sell. Whether you sell products or offer services, you have to deal with costs directly related to the goods or services you sell. Those costs primarily come from the purchase or manufacturing of the products you plan to sell or the items you need in order to provide the services. All companies must keep careful watch over the cost of the products to be sold or services to be offered. Ultimately, your company’s profits depend on how well you manage those costs because, in most cases, costs increase rather than decrease over time. How often do you find a reduction in the price of needed items? Doesn’t happen often. If costs increase but the price to the customer remains unchanged, the profit you make on each sale is less. In addition to the costs to produce products or services, every business has additional expenses associated with purchasing supplies needed to run the business. The bookkeeper has primary responsibility for monitoring all these costs and expenses as invoices are paid. Bookkeepers can alert company owners or managers when vendors increase prices. This chapter covers how to track purchases and their costs, manage inventory, buy and manage supplies, and pay the bills for your purchases. 68 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Keeping Track of Inventory Products to be sold are called inventory. As a bookkeeper, you use two accounts to track inventory: ✓ Purchases: Where you record the actual purchase of goods to be sold. You use this account to calculate the cost of goods sold, which is an item on the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2 for more on the income statement). ✓ Inventory: Where you track the value of inventory on hand. This value is shown on the balance sheet as an asset in a line item called inventory (see Book IV, Chapters 3–5 for more on the balance sheet). Companies track physical inventory on hand by using one of two methods: ✓ Periodic inventory: Conducting a physical count of the inventory in the stores and in the warehouse. This count can be done daily, monthly, yearly, or for any other period that best matches your business needs. (Many stores close for all or part of a day when they count inventory.) ✓ Perpetual inventory: Adjusting inventory counts as each sale is made. In order to use this method, you must manage your inventory by using a computerized accounting system that’s tied into your point of sale (usually cash registers). Even if you use a perpetual inventory method, it’s a good idea to periodically do a physical count of inventory to be sure those numbers match what’s in your computer system. Because theft, damage, and loss of inventory aren’t automatically entered in your computer system, the losses don’t show up until you do a physical count of the inventory you have on hand. When preparing your income statement at the end of an accounting period (whether that period is for a month, a quarter, or a year), you need to calculate the cost of goods sold in order to determine your profit. In order to calculate the cost of goods sold, you must first find out how many items of inventory were sold. You start with the amount of inventory on hand at the beginning of the month (called beginning inventory), as recorded in the inventory account, and add the amount of purchases, as recorded in the purchases account, to find the goods available for sale. Then you subtract the inventory on hand at the end of the month, which is determined by counting remaining inventory. Here’s how you calculate the number of goods sold: Beginning inventory + Purchases = Goods available for sale – Ending inventory = Items sold Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases 69 After you calculate goods available for sale, remember that your goods can end up in only two places: You may sell the goods (cost of goods sold) or have unsold goods sitting on your shelves (ending inventory). After you determine the number of goods sold, you compare that number to the actual number of items sold by the company during that accounting period, which is based on sales figures collected through the month. If the numbers don’t match, you have a problem. The mistake may be in the inventory count, or items may be unaccounted for because they’ve been misplaced or damaged and discarded. In the worst-case scenario, you may have a problem with theft by customers or employees. These differences are usually tracked within the accounting system in a line item called inventory shrinkage. Entering initial cost When your company first receives inventory, you enter the initial cost of that inventory into the bookkeeping system based on the shipment’s invoice. In some cases, invoices are sent separately, and only a packing slip is included in the order. If that’s the case, you should still record the receipt of the goods, because the company incurs the cost from the day the goods are received and must be sure it will have the money to pay for the goods when the invoice arrives and the bill comes due. (You track outstanding bills in the accounts payable account.) Entering the receipt of inventory is a relatively easy entry in the bookkeeping system. For example, if your company buys $1,000 of inventory to be sold, you make the following record in the books: Purchases (Asset account) Accounts payable Debit $1,000 Credit $1,000 The purchases account increases by $1,000 to reflect the additional costs, and the accounts payable account increases by the same amount to reflect the amount of the bill that needs to be paid in the future. The purchases account is used to isolate inventory purchased during the period (month or year). Purchases are part of the formula to calculate cost of goods sold (Book II, Chapter 2 explains this formula in detail): Cost of goods sold = Beginning inventory + Purchases – Ending inventory When inventory enters your business, in addition to recording the actual costs, you need more detail about what was bought, how much of each item was bought, and what each item cost. You also need to track Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 70 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions ✓ How much inventory you have on hand. ✓ The value of the inventory you have on hand. ✓ When you need to order more inventory. Tracking these details for each type of product bought can be a nightmare, especially if you’re trying to keep the books for a retail store. That’s because you need to set up a special inventory journal with pages detailing purchase and sale information for every item you carry. (See Book I, Chapter 3 for the scoop on journals.) Computerized accounting simplifies this process of tracking inventory. Details about inventory can be entered initially into your computer accounting system in several ways: ✓ If you pay by check or credit card when you receive the inventory, you can enter the details about each item on the check or credit card form. ✓ If you use purchase orders, you can enter the detail about each item on the purchase order, record receipt of the items when they arrive, and update the information when you receive the bill. ✓ If you don’t use purchase orders, you can enter the detail about the items when you receive them and update the information when you receive the bill. When you receive inventory with a bill, you can collect the data in a computerized accounting software program. Similar information is collected on the software program’s check, credit card, and purchase order forms. In addition to recording the name of the vendor, date received, and payment amount, you also record details about the items bought, including the quantity and cost. When you load each item into the computerized accounting system, you can easily track cost detail over time. After you receive the inventory, you then set up an inventory item in the computerized accounting system. Note that in addition to the item name, two descriptions are added to the accounting system: One is an abbreviated version you can use on purchase transactions (to save time), and the other is a longer description that’s displayed on customer invoices (sales transactions). You can input a cost and sales price if you want, or you can leave them at zero and enter the cost and sales prices with each transaction. If you have a set contract purchase price or sales price on an inventory item, it saves time to enter it on this form so you don’t have to enter the price each time you record a transaction. But, if the prices change frequently, it’s best to leave the space blank so you don’t forget to enter the updated price when you enter a transaction. Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases 71 Your accounting system should collect information about inventory on hand and when inventory needs to be reordered. To be sure your store shelves are never empty, you can enter a number that indicates at what point you want to reorder inventory. Accountants refer to this point as the reorder point. When the number of units on hand declines to the reorder point, you order more product. After you complete and save the form that records the receipt of inventory, your accounting software should automatically: ✓ Adjust the quantity of inventory you have in stock. ✓ Increase the asset account called inventory. Book II ✓ Lower the quantity of items on order (if you initially entered the information as a purchase order). Recording Accounting Transactions ✓ Average the cost of inventory on hand. ✓ Increase the accounts payable account. Managing inventory and its value After you record the receipt of inventory, you have the responsibility of managing the inventory you have on hand. You also must know the value of that inventory. You may think that as long as you know what you paid for the items, the value isn’t difficult to calculate. Well, accountants can’t let it be that simple, so there are actually four different ways to value inventory: ✓ LIFO (last in, first out): You assume that the last items put on the shelves (the newest items) are the first items to be sold. Retail stores that sell nonperishable items, such as tools, are likely to use this type of system. For example, when a hardware store gets new hammers, workers probably don’t unload what’s on the shelves and put the newest items in the back. Instead, the new tools are just put in the front, so they’re likely to be sold first. ✓ FIFO (first in, first out): You assume that the first items put on the shelves (the oldest items) are sold first. Stores that sell perishable goods, such as food stores, use this inventory valuation method most often. For example, when new milk arrives at a store, the person stocking the shelves unloads the older milk, puts the new milk at the back of the shelf, and then puts the older milk in front. Each carton of milk (or other perishable item) has a date indicating the last day it can be sold, so food stores always try to sell the oldest stuff first, while it’s still sellable. ✓ Weighted average: You average the cost of goods received, so there’s no reason to worry about which items are sold first or last. This method of inventory is used most often in any retail or services environment where 72 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions prices are constantly fluctuating and the business owner finds that an average cost works best for managing the cost of goods sold. ✓ Specific identification: You maintain cost figures for each inventory item individually. Retail outlets that sell big-ticket items, such as cars, which often have a different set of extras on each item, use this type of inventory valuation method. Accountants are big on consistency. After you choose an accounting method, you should stick with it. If your accounting method is the same each year, your financial results will be comparable year-to-year. A financial statement reader will be able to compare your results and notice trends. If you decide to change the method, you need to explain the reasons for the change in your financial statements. You also have to go back and show how the change in inventory method impacts your prior financial reporting. Figuring out the best method for you You may be wondering why it matters so much which inventory valuation method you use. The key to the choice is the impact on your bottom line as well as the taxes your company will pay. The total cost of your inventory and the number of units purchased and sold are the same — regardless of whether you choose the FIFO, LIFO, or weighted average method (see the previous section for explanations of these methods). Also, if prices rise over time (which is normally the case), your newer inventory items will be more expensive. This analysis assumes that the three inventory methods use the same sale prices per unit. After all your inventory items are sold, your total profit will be the same for the three methods. FIFO, because it assumes the oldest (and most likely the lowest-priced) items are sold first, results in a low cost of goods sold number. Because cost of goods sold is subtracted from sales to determine profit, a low cost of goods sold number produces a high profit. For more on cost of goods sold, see “Keeping Track of Inventory,” earlier in this chapter. The opposite is true for LIFO, which uses cost figures based on the last price paid for the inventory (and most likely the highest price). Using the LIFO method, the cost of goods sold number is high, which means a larger sum is subtracted from sales to determine profit. Thus, the profit margin is low. The good news, however, is that the tax bill is low, too. Rather than constantly dealing with the ups and downs of inventory costs, the weighted average method smooths out the numbers used to calculate a business’s profits. Cost of goods sold, taxes, and profit margins for this method fall between those of LIFO and FIFO. If you’re operating a business in which inventory prices are constantly going up and down, you should definitely choose this method. Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases 73 Comparing the methods To show you how much of an impact inventory valuation can have on profit margin, this section compares three of the most common methods: FIFO, LIFO, and weighted average (see the earlier section “Managing inventory and its value” for details on each). In this example, assume Company A bought the inventory in question at different prices on three different occasions. Beginning inventory is valued at $500 (that’s 50 items at $10 each). Here’s the calculation for determining the number of items sold (see “Keeping Track of Inventory”): Beginning inventory + Purchases = Goods available for sale – Ending inventory = Items sold 50 + 500 = 550 – 75 = 475 Here’s what the company paid to purchase the inventory: Date April 1 April 15 April 30 Quantity 150 150 200 Unit Price $10 $25 $30 Here’s an example of how you calculate the cost of goods sold by using the weighted average method: Account Beginning inventory Purchases Total inventory Average inventory cost Cost of goods sold Ending inventory Units and Dollar Amounts 50 units 150 units @$10 150 units @$25 200 units @$30 550 units $11,750 ÷ 550 units = $21.36 475 units × $21.36 = $10,146 75 units @$21.36 = $1,602 Total $500 $1,500 $3,750 $6,000 $11,750 As mentioned earlier in the section “Keeping Track of Inventory,” your goods available for sale can end up in only two places: cost of goods sold or ending inventory. The total inventory listed in the previous table is also goods available for sale. Your total inventory ($11,750) should equal the sum of cost of goods sold and ending inventory ($10,146 + $1,602 = $11,748). The slight difference is due to rounding the weighted average cost per unit. Use this formula to check any inventory valuation method. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 74 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Here’s an example of how you calculate the cost of goods sold by using the FIFO method. With this method, you assume that the first items received are the first ones sold, and because the first items received here are those in beginning inventory, this example starts with them: Account Beginning inventory Next in — April 1 Then — April 15 Then — April 30 Cost of goods sold Ending inventory Units and Dollar Amounts 50 units @$10 150 units @$10 150 units @$25 125 units @$30 475 units 75 units @$30 Total $500 $1,500 $3,750 $3,750 $9,500 $2,250 Note: Only 125 of the 200 units purchased on April 30 are used in the FIFO method. Because this method assumes that the first items into inventory are the first items sold (or taken out of inventory), the first items used are those on April 1. Then the April 15 items are used, and finally the remaining needed items are taken from those bought on April 30. Because 200 were bought on April 30 and only 125 were needed, 75 of the items bought on April 30 are left in ending inventory. Here’s an example of how you calculate the cost of goods sold by using the LIFO method. With this method, you assume that the last items received are the first ones sold, and because the last items received were those purchased on April 30, this example starts with them: Account April 30 Next — April 15 Then — April 1 Cost of goods sold Ending inventory Units and Dollar Amounts 200 units @$30 150 units @$25 125 units @$10 475 units 75 units @$10 Total $6,000 $3,750 $1,250 $11,000 $750 Note: Because LIFO assumes the last items to arrive are sold first, the ending inventory includes the 25 remaining units from the April 1 purchase plus the 50 units in beginning inventory. Here’s how the use of inventory under the LIFO method impacts the company profits. The example assumes the items are sold to the customers for $40 per unit, which means total sales of $19,000 for the month (that’s $40 × 475 units sold). This example looks only at the gross profit, which is the profit from sales before considering expenses incurred for operating the company. See Book IV, Chapter 2 for information about the different profit types and what they mean. Gross profit is calculated with the following equation: Sales – Cost of goods sold = Gross profit Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases 75 Table 2-1 shows a comparison of gross profit for the three methods used in this example scenario. Table 2-1 Comparison of Gross Profit Based on Inventory Valuation Method Income Statement Line Item FIFO LIFO Weighted Average Sales $19,000 $19,000 $19,000 Cost of Goods Sold $9,500 $11,000 $10,146 Gross Profit $9,500 $8,000 $8,854 Looking at the comparisons of gross profit, you can see that inventory valuation can have a major impact on your bottom line. LIFO is likely to give you the lowest profit because the last inventory items bought are usually the most expensive. FIFO is likely to give you the highest profit because the first items bought are usually the cheapest. And the profit produced by the weighted average method is likely to fall somewhere between the two. Keep in mind that all three inventory valuation methods generate the same total cost and total profit, when all the inventory items are sold, as explained earlier in this section. Buying and Monitoring Supplies In addition to inventory, all businesses must buy supplies that are used to operate the business, such as paper, pens, and paper clips. If the supply cost can’t be directly traced to the manufacturing or purchase of goods or services for sale, the cost is immediately expensed. Your best bet is to carefully track supplies that make a big dent in your budget with an individual account. For example, if you anticipate paper usage will be very high, monitor that usage with a separate account called “paper expenses.” Many companies don’t use the bookkeeping system to manage their supplies. Instead, they designate one or two people as office managers or supply managers and keep the number of accounts used for supplies to a minimum. Other businesses decide they want to monitor supplies by department or division and set up a supply account for each one. That puts the burden of monitoring supplies in the hands of the department or division managers. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 76 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Staying on Top of Your Bills Eventually, you have to pay for both the inventory and the supplies you purchase for your business. In most cases, the bills are posted to the accounts payable account when they arrive, and they’re paid when due. A large chunk of the cash paid out of your cash account (see Book VIII for more information on the cash account and handling cash) is in the form of the checks sent out to pay bills due in accounts payable, so you need to have careful controls over the five key functions of accounts payable: ✓ Entering the bills to be paid into the accounting system ✓ Preparing checks to pay the bills ✓ Signing checks to pay the bills ✓ Sending out payment checks to vendors ✓ Reconciling the checking account As you pay bills, you need to take precautions to keep everyone honest and try to take advantage of any discounts vendors offer for early payment, as discussed in the following sections. Segregating duties to prevent theft Segregation of duties is the process of delegating different tasks to different people to prevent fraud. To segregate duties, assign one person to each of the following three roles: ✓ Custodian: An individual in your organization who has physical custody of assets, such as the checkbook and keys to the company warehouse. ✓ Check signer: The check signer has authority to access or move assets. When you write a check, you’re moving cash. ✓ Record keeper: After the transaction is completed, the record keeper records the transaction in the accounting system. In your business, the person who enters the bills to be paid into the system probably also prepares the payment checks, but someone else should do the other tasks. You should never allow the person who prepares the checks to review the bills to be paid and sign the checks, unless of course that person’s you, the business owner. Chapter 2: Tracking Purchases 77 Properly managing accounts payable can save your company a lot of money by avoiding late fees or interest and by taking advantage of discounts offered for paying early. If you’re using a computerized accounting system, the bill due date and any discount information should be entered when you receive the inventory or supplies. If you’re working with a paper system rather than a computerized accounting system, you need to set up some way to be sure you don’t miss bill due dates. Because an increasing number of businesses are using computerized systems, this book won’t spend more time explaining the nuances of a paper system. Taking advantage of discounts In some cases, companies offer a discount to customers who pay their bills early. Assume a vendor gives you payment terms of “2% 10 Net 30.” That means that if the bill is paid in 10 days, the vendor company can take a 2 percent discount; otherwise, the amount due must be paid in full in 30 days. In addition, many companies state that interest or late fees will be charged if a bill isn’t paid in 30 days. A firm has an amount due for the bill of $1,000. If the company pays the bill in ten days, it can take a 2 percent discount, or $20. That may not seem like much, but if your company buys $100,000 of inventory and supplies in a month and each vendor offers a similar discount, you can save $2,000. Over the course of a year, discounts on purchases can save your business a significant amount of money and improve your profits. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 78 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Chapter 3 Counting Your Sales In This Chapter ▶ Taking in cash and offering in-store credit ▶ Staying on top of discounts, returns, and allowances ▶ Monitoring customer payments due ▶ Dealing with bad debt E very business loves to take in money, and that means bookkeepers have a lot to do to make sure sales are properly tracked and recorded in the books. In addition to recording the sales, you must track customer accounts, discounts offered to customers, and customer returns and allowances. Unfortunately, some customers never pay, in which case you must adjust the books to reflect nonpayment as a bad debt. This chapter reviews the basic responsibilities that fall to a business’s ­ ookkeeping and accounting staff for tracking sales, making adjustments b to those sales, monitoring customer accounts, and alerting management to slow- and no-paying customers. Collecting on Cash Sales Most businesses collect some form of cash as payment for the goods or ­services they sell. Cash receipts include more than just bills and coins; checks and credit cards also are considered cash sales for the purpose of bookkeeping. In fact, with electronic transaction processing, a deposit is usually made to the business’s checking account the same day (sometimes within just seconds of the transaction, depending on the type of system the business sets up with the bank). The only type of payment that doesn’t fall under the umbrella of a cash payment is purchases made on store credit — credit offered to customers directly by your business rather than through a third party, such as a bank credit card or loan. See “Selling on Credit,” later in this chapter, for details. 80 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Discovering the value of sales receipts Businesses generate sales receipts in one of three ways: by the cash register, by the credit card machine, or by hand (written out by the salesperson). Whichever of these three methods you choose for your sales transactions, the sales receipt serves two purposes: ✓ Gives the customer proof that the item was purchased on a particular day at a particular price in your store, in case he needs to exchange or return the merchandise. ✓ Gives the store a receipt that can be used at a later time to enter the transaction into the company’s books. At the end of the day, the receipts also are used to prove out the cash register and ensure that the cashier has taken in the right amount of cash based on the sales made. You’re probably familiar with cash receipts. To show you how much useable information can be generated on a sales receipt, here’s a sample receipt from a sale at a bakery: Sales Receipt 4/25/2015 Item Quantity Price Total White Serving Set Cheesecake, Marble Cheesecake, Blueberry 1 1 1 $40 20 20 $40 20 20 80.00 4.80 84.80 90.00 5.20 Sales Tax @ 6% Cash Paid Change A look at a receipt, such as this one, tells you the amount of cash collected, the type of products sold, the quantity of products sold, and the amount of sales tax collected. Your company may use some type of computerized system at the point of sale (usually the cash register) that’s integrated into the company’s accounting system. Sales information is collected throughout the day by the cash register. The automated system can post accounting entries to sales, sales tax collected, cash, inventory, and other accounts. Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales 81 If you don’t use a computerized system, you can post accounting entries manually, based on cash register activity. Here’s what an entry in the cash receipts journal would look like for the receipt of cash: Debit Cash in checking Sales Sales tax collected Cash receipts for April 25, 2015 Credit $84.80 $80.00 4.80 Here’s an explanation of each line item in the receipts journal ✓ Cash in checking, an asset account on the balance sheet, is debited, which increases the asset account. ✓ Sales is a revenue account that’s posted to the income statement. The credit to sales increases the revenue account. ✓ Sales tax collected is a liability account in the balance sheet. (See Book IV for more about balance sheets and income statements.) The credit to sales tax collected increases the liability account. Note that total debits equal total credits ($84.80). This is referred to as a ­balanced entry. Debits and credits are discussed in Book I, Chapter 2. Businesses pay sales tax to state and local government entities either monthly or quarterly, depending on rules set by the states. Your business must hold the money owed in a liability account to be certain you’re able to pay the taxes collected from customers when they’re due. Recording cash transactions in the books If you’re using a computerized accounting system, you can enter more detail from the day’s receipts and track inventory sold as well. A standard sales receipt includes the following key pieces of information: ✓ Customer’s name and address and perhaps the ID number you assign to that customer ✓ A description of the item(s) sold, along with the number or quantity sold ✓ Payment method; for example, cash, check, credit card, or debit ✓ The option to print the receipt or e-mail it to the client Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 82 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions In addition to the information included in the cash receipts journal, a ­computerized accounting system also collects information about the items sold in each transaction. The system then automatically updates inventory information, reducing the amount of inventory on hand as product is sold. When the inventory number falls below the reorder number you set (see Chapter 2), the accounting system alerts you to pass the word on to whoever is responsible for ordering more inventory. If your company accepts credit cards, expect sales revenue to be reduced by the fees paid to credit card companies. You may face monthly fees as well as fees per transaction; however, each company sets up individual arrangements with its bank regarding these fees. Sales volume impacts how much you pay in fees, so when researching bank services, be sure to compare credit card ­transaction fees to find a good deal. A company records these fees in a credit card fee expense account. Selling on Credit Many businesses decide to sell to customers on direct credit, meaning credit offered by the business and not through a bank or credit card provider. This approach offers more flexibility in the type of terms you can offer your ­customers, and you don’t have to pay bank fees. However, it involves more work for you, the bookkeeper, and more risk if a customer doesn’t pay what he or she owes. If you accept a customer’s bank-issued credit card for a sale and the c ­ ustomer doesn’t pay the bill, you get your money, and the bank is responsible for ­ collecting from the customer and takes the loss if he or she doesn’t pay. That’s not the case if you decide to offer credit to your customers directly. If a c ­ ustomer doesn’t pay, your business takes the loss. Deciding whether to offer store credit The decision to set up your own store credit system depends on what your competition is doing. For example, if you run an office supply store and all other office supply stores allow store credit to make it easier for their ­customers to get supplies, you probably need to offer store credit to stay competitive. If you want to allow your customers to buy on store credit, the first thing you need to do is set up some ground rules. You have to decide Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales 83 ✓ How you plan to check a customer’s credit history ✓ What the customer’s income level needs to be to be approved for credit ✓ How long you give the customer to pay the bill before charging interest or late fees ✓ What maximum dollar amount you plan to give the customer as a credit limit The harder you make it to get store credit and the stricter you make the bill-paying rules, the less chance you have of a taking a loss. However, you may lose customers to a competitor with less restrictive credit rules. Keep in mind that if you loosen your qualification criteria and bill-paying requirements, you have to carefully monitor your customer accounts to be sure they’re not falling behind. The key risk you face is selling product for which you’re never paid. Recording store credit transactions in the books When sales are made on store credit, you have to enter specific information into the accounting system. In addition to inputting information regarding cash receipts (see “Collecting on Cash Sales” earlier in this chapter), you update the customer accounts to be sure each customer is billed and the money is collected. You debit the accounts receivable account, an asset account shown on the balance sheet (see Book IV), which shows money due from customers. Here’s how a journal entry of a sale made on store credit looks: Debit Accounts receivable Sales Sales tax collected Cash receipts for April 25, 2015 Credit $84.80 $80.00 4.80 In addition to making this journal entry, you enter the information into the customer’s account so that accurate customer statements can be sent out at the end of the month. When the customer pays the bill, you update the ­individual customer’s record to show that payment has been received and enter the following into the bookkeeping records: Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 84 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Debit Cash Accounts receivable Payment from S. Smith on invoice 123. Credit $84.80 $84.80 You’ll send the customer an invoice (a bill). You see in the previous table that S. Smith was sent invoice #123. Most of the information on the invoice is ­similar to the sales receipt form (see “Collecting on Cash Sales”), but the invoice also has space to enter a different address for shipping (the “ship to” field) and includes payment terms (the “terms” field). An automated accounting system uses the information on the invoice form to update the following accounts: ✓ Accounts receivable ✓ Inventory ✓ The customer’s account ✓ Sales tax collected When the time comes to bill the customer at the end of the month, your accounting system can generate statements for all customers with outstanding invoices (unpaid bills). You can easily generate statements for specific customers or all customers on the books. When you receive payment from a customer (as you do earlier in the chapter with the S. Smith invoice), here’s what happens: 1. Accounts receivable is reduced by crediting. 2. Cash is increased with a debit. 3. The customer’s individual account is updated to reflect the payment. If your company uses a point of sale program that’s integrated into the ­computerized accounting system, recording store credit transactions is even easier for you. Sales details feed into the system as each sale is made, so you don’t have to enter the detail at the end of day. These point of sale programs save a lot of time. Even if customers don’t buy on store credit, point of sale programs provide businesses with an incredible amount of information about their customers and what they like to buy. This data can be used in the future for direct ­marketing and special sales to increase return business. Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales 85 Proving Out the Cash Register To ensure that cashiers don’t pocket a business’s cash, at the end of each day, cashiers must prove out cash. This is a process to show that the cashier has the correct amount of cash in the register. The cash balance changes based on the sales transactions during the day. The balance is also affected by the amount of cash, checks, and charges that the cashier took in during the day. This process of proving out a cash register actually starts at the end of the previous day, when cashier John Doe and his manager agree to the amount of cash left in John’s register drawer. Cash sitting in cash registers or cash drawers is recorded as part of the cash on hand account. When John comes to work the next morning, he starts out with the amount of cash left in the drawer. At the end of the business day, either he or his manager runs a summary of activity on the cash register for the day to produce a report of the total sales taken in by the cashier. John counts the amount of cash in his register as well as totals the checks, credit card receipts, and store credit charges. He then completes a cash-out form that looks something like this: Cash Register: John Doe, 4/25/2015 Receipts Beginning cash Cash sales Credit card sales Store credit sales Total sales Sales on credit Cash received Total cash in register Sales Total $100 $400 800 200 1,400 1,000 400 500 A store manager reviews John Doe’s cash register summary (produced by the actual register) and compares it to the cash-out form. If John’s ending cash (the amount of cash remaining in the register) doesn’t match the cashout form, he and the manager try to pinpoint the mistake. If they can’t find a mistake, they fill out a cash-overage or cash-shortage form. Some businesses charge the cashier directly for any shortages; others take the position that the cashier’s fired after a certain number of shortages of a certain dollar amount (say, three shortages of more than $10). Most companies post cash shortages to a shortage expense account. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 86 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions The store manager decides how much cash to leave in the cash drawer or register for the next day and deposits the remainder. He does this task for each of his cashiers and then deposits all the cash and checks from the day in a night deposit box at the bank. He sends a report with details of the deposit to the bookkeeper so that the data makes it into the accounting system. The bookkeeper enters the data on the cash receipts form (see the previous table) if a computerized accounting system is being used or into the cash receipts journal if the books are being kept manually. Tracking Sales Discounts Most businesses offer discounts at some point in order to generate more sales. Discounts are usually in the form of a sale with 10 percent, 20 percent, or even more off purchase price. When you offer discounts to customers, it’s a good idea to track your sales discounts in a separate account so you can keep an eye on how much you discount sales in each month. If you find you’re losing more and more money to discounting, look closely at your pricing structure and competition to find out why it’s necessary to frequently lower your prices in order to make sales. You can track discount information very easily by using the data found on a standard sales register receipt. The following receipt from a bakery includes sales discount details. Sales Receipt 4/25/2015 Item Quantity Price Total White Serving Set Cheesecake, Marble Cheesecake, Blueberry 1 1 1 $40 20 20 $40 20 20 80.00 Sales Discount @ 10% (8.00) Sales Tax @ 6% 4.32 Cash Paid Change 80.00 3.68 72.00 76.32 From this example, you can see clearly that the stores take in less cash when discounts are offered. When recording the sale in the cash receipts journal, you record the discount as a debit. This debit increases the sales discount account, which is subtracted from the sales account to calculate the net Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales 87 sales. (Book IV, Chapter 2 walks you through all these steps and calculations as it discusses preparing the income statement.) Here’s the bakery’s entry for this particular sale in the cash receipts journal: Debit Cash in checking Sales discounts Sales Sales tax collected Cash receipts for April 25, 2015 Credit $76.32 8.00 $80.00 4.32 Book II If you use a computerized accounting system, add the sales discount as a line item on the sales receipt or invoice, and the system automatically adjusts the sales figures and updates your sales discount account. Recording Sales Returns and Allowances Most stores deal with sales returns on a regular basis. Instituting a no-return policy is guaranteed to produce unhappy customers, so to maintain good customer relations; you should generally allow sales returns. Sales allowances (sales incentive programs) are becoming more popular with businesses. Sales allowances are most often in the form of a gift card. A gift card that’s sold is actually a liability for the company because the company has received cash, but no merchandise has gone out. For that reason, gift card sales are entered in a gift card liability account. When a customer makes a purchase at a later date by using the gift card, the gift card liability account is reduced (debited) and inventory is also reduced (with a credit). Monitoring the gift card liability account allows businesses to keep track of how much is yet to be sold without receiving additional cash. Accepting sales returns can be a more complicated process than accepting sales allowances. Usually, a business posts a set of rules for returns that may include: ✓ Returns will be allowed within only 30 days of purchase. ✓ You must have a receipt to return an item. ✓ If you return an item without a receipt, you can receive only store credit. Recording Accounting Transactions 88 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions You can set whatever rules you want for returns. For internal control ­ urposes, the key to returns is monitoring how your staff handles them. In p most cases, you should require a manager’s approval on returns. Also, be sure your staff pays close attention to how the customer originally paid for the item being returned. You certainly don’t want to give a customer cash if she paid on store credit — that’s just handing over your money! After a return’s approved, the cashier returns the amount paid by either cash or credit card. Customers who bought the items on store credit don’t get any money back. That’s because they didn’t pay anything when they purchased the item, but expected to be billed later. Instead, a form is filled out so that the amount of the original purchase can be subtracted from the customer’s store credit account. You use the information collected by the cashier who handled the return to input the sales return data into the books. For example, a customer returns a $40 item that was purchased with cash. You record the cash refund in the cash receipts journal like this: Debit Sales returns and allowances Sales tax collected @ 6% Cash in checking To record return of purchase, 4/30/2015. Credit $40.00 2.40 $42.40 If the item had been bought with a discount, you’d list the discount as well and adjust the price to show that discount. In this journal entry, ✓ The sales returns and allowances account increases. This account normally carries a debit balance and is subtracted from sales when ­preparing the income statement, thereby reducing revenue received from customers. ✓ The debit to the sales tax collected account reduces the amount in that account because sales tax is no longer due on the purchase. ✓ The credit to the cash in checking account reduces the amount of cash. Chapter 3: Counting Your Sales 89 Monitoring Accounts Receivable Making sure customers pay their bills is a crucial responsibility of the ­bookkeeper. Before sending out the monthly bills, you should prepare an aging summary report that lists all customers who owe money to the c ­ ompany and how old each debt is. If you keep the books manually, you collect the necessary information from each customer account. If you keep the books in a computerized accounting system, you can generate this report automatically. Either way, your aging summary report should look similar to this example report from a bakery: Aging Summary — As of April 30, 2015 Customer Current 31–60 Days S. Smith J. Doe H. Harris M. Man Totals $84.32 $46.15 61–90 Days >90 Days $65.78 89.54 173.86 46.15 65.78 $125.35 125.35 The aging summary quickly tells you which customers are behind in their bills. In this example, customers are cut off from future purchases when their payments are more than 60 days late, so J. Doe and M. Man aren’t able to buy on store credit until their bills are paid in full. Give a copy of your aging summary to the sales manager so he can alert staff to problem customers. He can also arrange for the appropriate collections procedures. Each business sets up its own collections process, but usually it starts with a phone call, followed by letters, and possibly even legal action, if necessary. Accepting Your Losses You may encounter a situation in which a customer never pays your business, even after an aggressive collections process. In this case, you have no choice but to write off the purchase as a bad debt and accept the loss. Most businesses review their aging reports monthly and decide which accounts need to be written off as bad debt. Accounts written off are tracked in a general ledger account called bad debt. (See Book I, Chapter 3 for more Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 90 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions information about the general ledger.) The bad debt account appears as an expense account on the income statement. When you write off a c ­ ustomer’s account as bad debt, the bad debt account increases (debit), and the accounts receivable account decreases (credit). To give you an idea of how you write off an account, assume that one of your customers never pays the $105.75 due. Here’s what your journal entry looks like: Debit Bad debt Accounts receivable Credit $105.75 $105.75 In a computerized accounting system, you enter the information by using a customer payment form and allocating the amount due to the bad debt expense account. Finally, make a note of the bad debt on each customer’s individual account. Going forward, you’ll know which customers didn’t pay an invoice. That information will help you make a decision about doing ­business with the customer going forward. Chapter 4 Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits In This Chapter ▶ Hiring employees ▶ Collecting and depositing employee taxes ▶ Keeping track of benefits ▶ Preparing and recording payroll U nless your business has only one employee (you, the owner), you’ll most likely hire employees, and that means you’ll have to pay them, offer benefits, and manage a payroll. Responsibilities for hiring and paying employees usually are shared among the human resources staff and the bookkeeping staff. As the bookkeeper, you must be sure that all government tax-related forms are completed and handle all payroll responsibilities including paying employees, collecting and paying employee taxes, collecting and managing employee benefit contributions, and paying benefit providers. This chapter examines the various employee staffing issues that bookkeepers need to be able to manage. Staffing Your Business After you decide that you want to hire employees for your business, you must be ready to deal with a lot of government paperwork. In addition to paperwork, you face many decisions about how employees will be compensated and who will be responsible for maintaining the paperwork required by state, local, and federal government entities. Knowing what needs to be done to satisfy government bureaucracies isn’t the only issue you must consider before hiring your first employee; you also must decide how frequently you’ll pay employees and what type of wage and salary scales you want to set up. 92 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Completing government forms Even before you sign your first employee, you need to start filing government forms related to hiring. If you plan to hire staff, you must first apply for an Employer Identification Number, or EIN. Government entities use this number to track your employees, the money you pay them, and any taxes collected and paid on their behalf. Before employees start working for you, they must fill out forms including the W-4 (tax withholding form), I-9 (citizenship verification form), and W-5 (for employees eligible for the Earned Income Credit). The following sections explain each of these forms as well as the EIN. Employer Identification Number (EIN) Every company must have an EIN to hire employees. If your company is incorporated (see Book VI, Chapter 2 for the lowdown on corporations and other business types), which means you’ve filed paperwork with the state and become a separate legal entity, you already have an EIN. Otherwise, to get an EIN you must complete and submit Form SS-4, which you can see in Figure 4-1. Luckily, the government offers four ways to submit the necessary information and obtain an EIN. The fastest way is to call the IRS’s Business & Specialty Tax Line at 800-829-4933 and complete the form by telephone. IRS officials assign your EIN over the telephone. You can also apply online at www.irs.gov, or you can download Form SS-4 at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/fss4.pdf and submit it by fax or by mail. In addition to tracking pay and taxes, state entities use the EIN number to track the payment of unemployment taxes and workers’ compensation taxes, both of which the employer must pay (see Chapter 5 for details). W-4 Every person you hire must fill out a W-4 form called the “Employee’s Withholding Allowance Certificate.” You’ve probably filled out a W-4 at least once in your life, if you’ve ever worked for someone else. You can download this form and make copies for your employees at www.irs.gov/pub/ irs-pdf/fw4.pdf. This form, shown in Figure 4-2, tells you, the employer, how much to take out of your employees’ paychecks in income taxes. On the W-4, employees indicate whether they’re married or single. They can also claim additional allowances if they have children or other major deductions that can reduce their tax bills. The amount of income taxes you need to take out of each employee’s check depends upon how many allowances he or she claimed on the W-4. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 93 Book II Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 4-1: You must file IRS Form SS-4 to get an Employer Identification Number before hiring employees. Courtesy of IRS 94 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 4-2: IRS Form W-4 should be completed by all employees when they’re hired so that you know how much to take out of their paychecks for taxes. Courtesy of IRS It’s a good idea to ask an employee to fill out a W-4 immediately, but you can allow the employee to take the form home if he or she wants to discuss allowances with a spouse or an accountant. If an employee doesn’t complete a W-4, you must take income taxes out of his or her check based on the highest possible amount for that person. See “Collecting Employee Taxes” later in this chapter. An employee can always fill out a new W-4 to reflect life changes that impact the tax deduction. For example, if the employee was single when he started working for you and gets married a year later, he can fill out a new W-4 and claim his spouse, lowering the amount of taxes that must be deducted from his check. Another common life change that can reduce an employee’s tax deduction is the birth or adoption of a child. I-9 All employers in the United States must verify that any person they intend to hire is a U.S. citizen or has the right to work in the United States. As an employer, you verify this information by completing and keeping on file an I-9 form from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The new hire fills out Section 1 of the form by providing information, including name and address, birth history, Social Security number, and U.S. Citizenship or work permit. You fill out Section 2, which requires you to check for documents that establish identity and prove employment eligibility. Workers can provide a driver’s license; a military ID, student ID, or official state ID; or a Social Security card, birth certificate, or U.S. passport. Instructions provided with the form list all acceptable documents you can use to verify work eligibility. You must complete Section 2 of the I-9; making copies of the employment eligibility documents (IDs) for your files isn’t enough. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 95 Figure 4-3 shows a sample I-9 form. You can download the form and its instructions from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website at www.uscis.gov/files/form/i-9.pdf. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 4-3: U.S. employers must verify a new hire’s eligibility to work in the United States by completing Form I-9. Courtesy of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services 96 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions W-5 Some employees you hire may be eligible for the Earned Income Credit (EIC), which is a tax credit that refunds some of the money the employee would otherwise pay in taxes, such as Social Security or Medicare. In order to get this credit, the employee must have a child and meet other income qualifications that are detailed on the form’s instructions. The government started the EIC credit, which reduces the amount of tax owed, to help lower-income people offset increases in living expenses and Social Security taxes. Having an employee complete Form W-5 allows you to advance the expected savings of the EIC to the employee on his paycheck each pay period rather than make him wait to get the money back at the end of the year after filing tax forms. The advance amount isn’t considered income, so you don’t need to take out taxes on this amount. As an employer, you aren’t required to verify an employee’s eligibility for the EIC tax credit. The eligible employee must complete a W-5 each year to indicate that he still qualifies for the credit. If the employee doesn’t file the form with you, you can’t advance any money to the employee. If an employee qualifies for the EIC, you calculate his paycheck the same as you would any other employee’s paycheck, deducting all necessary taxes to get the employee’s net pay. Then you add back in the EIC advance credit that’s allowed. Any advance money you pay to the employee can be subtracted from the employee taxes you owe to the government. For example, if you’ve taken out $10,000 from employees’ checks to pay their income, Social Security taxes, and Medicare taxes and then returned $500 to employees who qualified for the EIC, you subtract that $500 from the $10,000 and pay the government only $9,500. You can find out more about form W-5 and its instructions at www.irs.gov. Picking pay periods Deciding how frequently you’ll pay employees is an important point to work out before hiring staff. Most businesses choose one or more of these four pay periods: ✓ Weekly: Employees are paid every week, and payroll must be done 52 times a year. ✓ Biweekly: Employees are paid every two weeks, and payroll must be done 26 times a year. ✓ Semimonthly: Employees are paid twice a month, commonly on the 15th and last day of the month, and payroll must be done 24 times a year. ✓ Monthly: Employees are paid once a month, and payroll must be done 12 times a year. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 97 You can choose to use any of these pay periods, and you may even decide to use more than one type. For example, some companies pay hourly employees (employees paid by the hour) weekly or biweekly and pay salaried employees (employees paid by a set salary regardless of how many hours they work) semimonthly or monthly. Whatever your choice, decide on a consistent pay period policy and be sure to make it clear to employees when they’re hired. For each employee who’s paid hourly, you need to have some sort of time sheet to keep track of work hours. These time sheets are usually completed by the employees and approved by their managers. Completed and approved time sheets are then sent to the bookkeeper so that checks can be calculated based on the exact number of hours worked. Determining wage and salary types You have a lot of leeway regarding the level of wages and salary you pay your employees, but you still have to follow the rules laid out by the U.S. Department of Labor. When deciding on wages and salaries, you have to first categorize your employees. Employees fall into one of two categories: ✓ Exempt employees are exempt from the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which sets rules for minimum wage, equal pay, overtime pay, and child labor laws. Executives, administrative personnel, managers, professionals, computer specialists, and outside salespeople can all be exempt employees. They’re normally paid a certain amount per pay period with no connection to the number of hours worked. Often, exempt employees work well over 40 hours per week without extra pay. ✓ Nonexempt employees must be hired according to rules of the FLSA, meaning that companies within certain parameters must pay a minimum hourly wage. Any nonexempt employee who works more than 40 hours in a seven-day period must be paid a higher hourly rate for the additional hours worked, often called overtime. Minimum wage doesn’t have to be paid in cash. The employer can pay some or all of the wage in room and board provided it doesn’t make a profit on any noncash payments. Also, the employer can’t charge the employee to use its facilities if the employee’s use of a facility is primarily for the employer’s benefit. For details about who can be designated an exempt employee, visit the U.S. Department of Labor’s website at www.dol.gov. Federal and state minimum wage laws change over time, so be sure to check with your state department of labor to be certain you’re meeting the wage guidelines. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 98 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions If you plan to hire employees who are under the age of 18, pay attention to child labor laws. Federal and state laws restrict what kind of work children can do, when they can do it, and how old they have to be to do it, so be sure you become familiar with the laws before hiring employees who are younger than 18. For minors below the age of 16, work restrictions are even tighter than for teens aged 16 and 17. (You can hire your own child without worrying about these restrictions.) You can get a good summary of all labor laws at the Business Owner’s Toolkit online at www.toolkit.cch.com/text/p05_4037.asp. Collecting Employee Taxes In addition to following wage and salary guidelines set for your business, when calculating payroll, you, the bookkeeper, must also be familiar with how to calculate the employee taxes that must be deducted from each employee’s paycheck. These taxes include Social Security; Medicare; and federal, state, and local withholding taxes. Sorting out Social Security tax Employers and employees share the Social Security tax equally: Each must pay a certain percentage of her income toward Social Security up to a specified cap per year per person. The amount an employee earns above the cap may not be subject to Social Security tax. The federal government adjusts the cap each year based on salary level changes in the marketplace. Essentially, the cap gradually increases as salaries increase. The calculation for Social Security taxes is relatively simple. For example, for an employee who makes $1,000 per pay period, assuming a rate of 6.2 percent for Social Security, you calculate Social Security tax this way: $1,000 × 0.062 = $62 The bookkeeper deducts $62 from this employee’s gross pay, and the company also pays the employer’s share of $62. Thus, the total amount submitted in Social Security taxes for this employee is $124. Making sense of Medicare tax Employees and employers also share Medicare taxes. However, unlike Social Security taxes, the federal government places no cap on the amount that must be paid in Medicare taxes. So even if someone makes $1 million per Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 99 year, the Medicare tax percentage is calculated for each pay period and paid by both the employee and the employer. Here’s an example of how you calculate the Medicare tax for an employee who makes $1,000 per pay period, assuming a Medicare tax rate of 1.45 percent: $1,000 × 0.0145 = $14.50 The bookkeeper deducts $14.50 from this employee’s gross pay, and the company also pays the employer’s share of $14.50. Thus, the total amount submitted in Medicare taxes for this employee is $29. Figuring out federal withholding tax To avoid dealing with nearly all withholdings from pay, you can hire a payroll company to handle the task. ADP and Paychex are two large providers of payroll services. You may find that the rate you pay an outside company is far less than the time and expense of performing this task yourself. For bookkeepers and accountants, deducting federal withholding taxes is a much more complex task than deducting Social Security or Medicare taxes. You not only have to worry about an employee’s tax rate, but also must consider the number of withholding allowances the employee claimed on her W-4 and whether the employee is married or single. Generally speaking, the first so many thousands of dollars are taxed at one low rate. As an individual or couple earns more, that income may bump them into higher tax brackets, meaning that extra income gets taxed at a higher rate. Trying to figure out taxes separately for each employee based on his or her tax rate and number of allowances would be an extremely time-consuming task, but luckily, you don’t have to do that. The IRS publishes tax tables in Publication 15, “Employer’s Tax Guide,” that let you just look up an ­employee’s tax obligation based on the taxable salary and withholdings. You can access the IRS Employer’s Tax Guide online at www.irs.gov/­ publications/p15/index.html. You can find tables for calculating ­withholding taxes at www.irs.gov/publications/p15/ar03.html. The IRS’s tax tables give you detailed numbers for levels of withholding allowances. Table 4-1 shows a sample tax table with only seven allowances because of space limitations. But even with seven allowances, you get the idea — just match the employee’s wage range with the number of allowances he or she claims, and the box where they meet contains the amount of that employee’s tax obligation. For example, if you’re preparing a paycheck for an employee whose taxable income is $1,000 per pay period, and he claims three withholding allowances — one for himself, one for his wife, and one for his child — then the amount of federal income taxes you deduct from his pay is $106. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 100 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Table 4-1 Portion of an IRS Tax Table for Employers If Wages Are: And the Number of Allowances Claimed Is: At Least But Less Than 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 $1,000 $1,010 $144 $125 $106 $91 $80 $68 $57 1,010 1,020 146 127 109 92 81 70 59 1,020 1,030 149 130 111 94 83 71 60 Settling up state and local w­ithholding taxes In addition to the federal government, most states have income taxes, and some counties and cities even have local income taxes. You can find all state tax rates and forms online at www.payroll-taxes.com. If your state, county, or city has income taxes, they need to be taken out of each ­employee’s paycheck. Determining Net Pay Net pay (commonly referred to as take-home pay) is the amount a person is paid after subtracting all tax and benefit deductions. After you figure out all the necessary taxes to be deducted from an employee’s paycheck, you can calculate the check amount. Here’s the equation and an example of how you calculate the net pay amount: Gross pay – (Social Security + Medicare + Federal withholding tax + State withholding tax + Local withholding tax + Benefit deductions) = Net pay 1,000 – (62 + 14.50 + 106 + 45 + 0 + 0) = 772.50 Many businesses offer their employees health, retirement, and other benefits but expect the employees to share a portion of those costs. The fact that some of these benefits are tax deductible and some aren’t makes a difference in when you deduct the benefit costs. If an employee’s benefits are tax deductible and taken out of the check before federal withholding taxes are calculated, the federal tax rate may be lower than if the benefits are deducted after calculating federal withholding taxes. Many states follow the federal government’s lead on tax-deductible benefits, so the amount deducted for state taxes will be lower as well. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 101 Surveying Your Benefits Options Benefits include programs that you provide your employees to better their lives, such as health insurance and retirement savings opportunities. Some benefits are tax-exempt, which means that the employee isn’t taxed for them. However, some benefits are taxable, so the employee has to pay taxes on the money or the value of the benefits received. This section reviews the different tax-exempt and taxable benefits you can offer your employees. Tax-exempt benefits Some benefits are tax-exempt (not taxed). In some cases, healthcare and retirement benefits are tax-exempt. You may have a flexible spending plan at work, for example. Your company provides tax-exempt payments that you can use to pay for medical expenses. In fact, accident and health benefits and retirement benefits make up the largest share of employers’ pay toward employees’ benefits. If the benefits are tax-exempt, anything an employee pays toward them is deducted from the gross pay, so the employee doesn’t have to pay taxes on that part of his salary or wage. The rules change frequently, so check with a tax advisor. For example, if an employee’s share of tax-exempt health insurance is $50 per pay period and he makes $1,000 per pay period, his taxable income is actually $1,000 minus the $50 health insurance premium contribution, or $950. As the bookkeeper, you calculate taxes in this situation on $950 rather than $1,000. Employee contributions to the retirement plan you offer may be tax deductible, too. Here’s an example, assuming the tax deduction is allowed: If an employee contributes $50 per pay period to your company’s 401(k) retirement plan, that $50 can also be subtracted from the employee’s gross pay before you calculate net pay. So if an employee contributes $50 to health insurance and $50 to retirement, the $1,000 taxable pay is reduced to only $900 taxable pay. You can offer a myriad of other benefits to employees, as well, including: ✓ Adoption assistance: You can provide up to a certain cap per child that an employee plans to adopt without having to include that amount in taxable gross income. The value of this benefit must be included when calculating Social Security and Medicare taxes, however. ✓ Athletic facilities: You can offer your employees the use of a gym on premises your company owns or leases without having to include the value of the gym facilities in gross pay. In order for this benefit to qualify as tax-exempt, the facility must be operated by the company primarily for the use of employees, their spouses, and their dependent children. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 102 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions ✓ Dependent care assistance: You can help your employees with dependent care expenses, which can include children and elderly parents, provided you offer the benefit in order to make it possible for the employee to work. ✓ Education assistance: You can pay employees’ educational expenses up to a certain amount without having to include that payment in gross income. ✓ Employee discounts: You can offer employees discounts on the company’s products without including the value of the discounts in their gross pay, provided the discount isn’t more than 20 percent less than what’s charged to customers. ✓ Group term life insurance: You can provide group term life insurance up to a specified coverage level to your employees without including the value of this insurance in their gross pay. Premiums for coverage above the cap may be added to calculations for Social Security and Medicare taxes. ✓ Meals: Meals that have little value (such as coffee and doughnuts) don’t have to be reported as taxable income. Also, occasional meals brought in so employees can work late don’t have to be reported in employees’ income. ✓ Moving expense reimbursements: If you pay moving expenses for employees, you don’t have to report these reimbursements as employee income as long as the reimbursements are for items that would qualify as tax-deductible moving expenses on an employee’s individual tax return. Employees who have been reimbursed by their employers can’t deduct the moving expenses for which the employer paid. Again, check with a tax professional on the deductibility and taxability of these benefits. Taxable benefits You may decide to provide some benefits that are taxable. These benefits may include the personal use of a company automobile, life insurance premiums for coverage over the cap, and benefits that exceed allowable maximums. Dealing with cafeteria plans Cafeteria plans are benefit plans that offer employees a choice of benefits based on cost. Employees can pick and choose from those benefits and put together a benefit package that works best for them within the established cost structure. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 103 Cafeteria plans are becoming more popular among larger businesses, but not all employers decide to offer their benefits this way. Managing a cafeteria plan can be much more time consuming for the bookkeeping and human resources staff. Many small businesses that offer a cafeteria plan for benefits do so by outsourcing benefit management services to an outside company that specializes in managing cafeteria plans. For example, a company tells its employees that it will pay up to $5,000 in benefits per year and values its benefit offerings this way: Health insurance Retirement Child care Life insurance $4,600 1,200 1,200 800 Joe, an employee, then picks from the list of benefits until he reaches $5,000. If Joe wants more than $5,000 in benefits, he pays for the additional benefits with a reduction in his paycheck. The list of possible benefits could be considerably longer, but in this case, if Joe chooses health insurance, retirement, and life insurance, the total cost is $6,600. Because the company pays up to $5,000, Joe needs to copay $1,600, a portion of which is taken out in each paycheck. If Joe gets paid every two weeks for a total of 26 paychecks per year, the deduction for benefits from his gross pay (with rounding) is $61.54 ($1,600 ÷ 26). Preparing Payroll and Posting It in the Books When you know the details about your employees’ withholding allowances and their benefit costs, you can then calculate the final payroll and post it to the books. Calculating payroll for hourly employees When you’re ready to prepare payroll for nonexempt (hourly) employees, the first thing you need to do is collect time records from each person who is paid hourly. Some companies use time clocks, and some use time sheets Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 104 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions to produce the required time records. Whatever method is used, the m ­ anager of each department usually reviews the time records for each employee supervised. After the manager’s review, he or she sends those time records to you, the bookkeeper. With time records in hand, you have to calculate gross pay for each employee. For example, if a nonexempt employee worked 45 hours and is paid $12 an hour, you calculate gross pay like so: 40 regular hours × $12 per hour = $480 5 overtime hours × $12 per hour × 1.5 overtime rate = $90 $480 + $90 = $570 In this case, because the employee isn’t exempt from the FLSA (see “Determining wage and salary types” earlier in this chapter), overtime must be paid for any hours worked over 40 in a seven-day workweek. This employee worked five hours more than the 40 hours allowed, so assume he needs to be paid at time plus one-half (the hourly rate paid over 40 hours may change). Doling out funds to salaried employees In addition to preparing payroll for hourly employees, you also must prepare payroll for salaried employees. Paychecks for salaried employees are relatively easy to calculate — all you need to know are their base salaries and their pay period calculations. For example, if a salaried employee makes $30,000 per year and is paid twice a month (totaling 24 pay periods), that employee’s gross pay is $1,250 for each pay period. Totaling up for commission checks Running payroll for employees paid based on commission can involve complex calculations. To show you a number of variables, this section calculates a commission check based on a salesperson who sells $60,000 of product during one month. For a salesperson on a straight commission of 10 percent, you calculate pay by using this formula: Total amount sold × Commission percentage = Gross pay $60,000 × 0.10 = $6,000 Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 105 For a salesperson with a guaranteed base salary of $2,000 plus an additional 5 percent commission on all products sold, you calculate pay by using this formula: Base salary + (Total amount sold × Commission percentage) = Gross pay $2,000 + ($60,000 × 0.05) = $5,000 Although this employee may be happier having a base salary he can count on each month, he actually makes less with a base salary because the commission rate is so much lower. By selling $60,000 worth of products, he earned only $3,000 in commission at 5 percent. Without the base pay, he would have made 10 percent on the $60,000 or $6,000. The salesperson actually got paid $1,000 less with a base pay structure that includes a lower commission pay rate. If he has a slow sales month of just $30,000 worth of products sold, his pay would be: $30,000 × 0.10 = $3,000 on straight commission of 10 percent and $30,000 × 0.05 = $1,500 plus $2,000 base salary, or $3,500 For a slow month, the salesperson would make more money with the base salary than with the higher commission rate. There are many other ways to calculate commissions. One common way is to offer higher commissions on higher levels of sales. Using the figures in the next example, this type of pay system encourages salespeople to keep their sales levels over $30,000 to get the best commission rate. With a graduated commission scale, a salesperson can make a straight commission of 5 percent on his first $10,000 in sales, then 7 percent on his next $20,000, and finally 10 percent on anything over $30,000. Here’s what his gross pay calculation looks like, using this commission pay scale: ($10,000 × 0.05) + ($20,000 × 0.07) + ($30,000 × 0.10) = $4,900 Gross pay One other type of commission pay system involves a base salary plus tips. This method is common in restaurant settings in which servers receive between $2.50 and $5 per hour plus tips. Businesses that pay less than minimum wage must prove that their employees make at least minimum wage when tips are accounted for. Today, that’s relatively easy to prove because most people pay their bills with credit cards and include tips on their bills. Businesses can then come up with an average tip rate by using that credit card data. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 106 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Employees must report tips to their employers on an IRS Form 4070, Employee’s Report of Tips to Employer, which is part of IRS Publication 1244, Employees Daily Record of Tips and Report to Employer. If your employees receive tips and you want to supply the necessary paperwork, you can download it at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p1244.pdf. The publication provides details about what the IRS expects you and your employees to do if they work in an environment where tipping is common. As an employer, you must report an employee’s gross taxable wages based on salary plus tips. Here’s how you calculate gross taxable wages for an employee whose earnings are based on tips and wages: Base wage + Tips = Gross taxable wages ($3 × 40 hours per week) + $300 = $420 If your employees are paid by using a combination of base wage plus tips, you must be sure that your employees are earning at least the minimum wage rate. Checking this employee’s gross wages, the hourly rate earned is $10.50 per hour. Hourly wage = $10.50 ($420 ÷ 40) Taxes due are calculated on the base wage plus tips, so the check you prepare for the employee in this example is for the base wage minus any taxes due. Putting it together to prepare payroll After calculating paychecks for all your employees, you prepare the payroll, make up the checks, and post the payroll to the books. In addition to cash, many accounts are impacted by payroll, including: ✓ Accrued federal withholding payable, where you record the liability for future federal tax payments. ✓ Accrued state withholding payable, where you record the liability for future state tax payments. Many companies have withholding accounts for FICA, Medicare, local taxes, and other categories. ✓ Accrued employee medical insurance payable, where you record the liability for future medical insurance premiums. ✓ Accrued employee elective insurance payable, where you record the liability for miscellaneous insurance premiums, such as life or accident insurance. When you post the payroll entry, you indicate the withdrawal of money from the cash account as well as record liabilities for future cash payments that Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 107 will be due for taxes and insurance payments. As an example of the proper setup for a payroll journal entry, assume the total payroll is $10,000 with $1,000 set aside for each type of withholding payable. In reality, your numbers will be much different, and your payables will probably never be all the same. Here’s what your journal entry for posting payroll should look like: Salaries and wages expense Accrued federal withholding payable Accrued state withholding payable Accrued medical insurance payable Accrued elective insurance payable Cash To record payroll for May 27, 2015. Debit $10,000 Credit $1,000 1,000 1,000 1,000 6,000 In this entry, you increase the expense account for salaries and wages as well as all the accounts in which you accrue future obligations for taxes and employee insurance payments. When cash payments are made for the taxes and insurance payments, you post those payments in the books. Here’s an example of the entry you would post to the books after making the federal withholding tax payment: Debit Accrued federal withholding payable $1,000 Cash in checking To record the payment of May federal taxes for employees. Credit $1,000 Depositing Employee Taxes Any taxes collected on behalf of employees must be deposited in a financial institution authorized to collect those payments for the government or in the Federal Reserve Bank in your area. Most major banks are authorized to collect these deposits; check with your bank to see whether it is or to get a recommendation of a bank you can use. IRS Form 8109, Federal Tax Deposit (FTD) Coupon, is the coupon businesses use to deposit taxes. You can’t get a copy of this form online; it’s available only from the IRS or a bank that ­handles your deposits. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 108 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Form 8109 can be used to deposit many different kinds of federal payments, including: ✓ Form 941, Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return (includes federal withholding taxes, Social Security taxes, and Medicare taxes) ✓ Form 940, Employer’s Annual Federal Unemployment (FUTA) Tax Return ✓ Form 1120, U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return When depositing funds by using Form 8109, be sure to include the EIN and name of the company on the coupon as well as the form number related to the payment. The IRS tracks payments by EIN number and form number filed. For the purposes of tax payments collected from employees for the federal government, you must complete Form 941, which is shown in Figure 4-4. This form summarizes the tax payments made on behalf of employees. You can get instructions and Form 941 online at www.irs.gov — just search on the site for the term “Form 941.” (For more about the various forms employers must file, see Chapter 5.) During the first year as an employer, the company will have to make monthly deposits of employee taxes. Monthly payments must be made by the 15th day of the month following when the taxes were deducted. For example, taxes collected from employees in April must be paid by May 15. If the date the deposit is due falls on a weekend or bank holiday, the payment is due on the next day the banks are open. As your business grows, you may need to make more frequent deposits. You can also make employee tax payments electronically by using the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). To find out more, check out IRS Publication 15 at www.irs.gov. Chapter 4: Processing Employee Payroll and Benefits 109 Book II Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 4-4: Employers must file Form 941 to report taxes collected on behalf of employees. 110 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 4-4: (continued) Courtesy of IRS Chapter 5 Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes In This Chapter ▶ Tallying the employer’s share of Social Security and Medicare ▶ Filing and paying unemployment taxes ▶ Figuring out workers’ compensation ▶ Keeping accurate employee records A fter your company hires employees, you need to complete regular reports for the government regarding the taxes you must pay toward the employees’ Social Security and Medicare, as well as unemployment taxes. In most states, employers also are required to buy workers’ compensation insurance based on employees’ salary and wages. This chapter reviews the federal, state, and local government reporting requirements for employers as well as the records you, the accountant, must keep in order to complete these reports. You also find out about the requirements for buying workers’ compensation insurance. Paying Employer Taxes on Social Security and Medicare In the United States, both employers and employees must contribute to the Social Security and Medicare systems. In most cases, employers share equally with employees the tax obligation for both Social Security and Medicare. 112 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions As discussed in Chapter 4, the employer and the employee each must pay a certain percentage of an employee’s compensation for Social Security. Employer and employee must also pay a percentage of wages toward Medicare. When you finish calculating payroll checks, you calculate the employer’s portion of Social Security and Medicare. When you post the payroll to the books, you set aside the employer’s portion of Social Security and Medicare in an accrual account. Filing Form 941 Each quarter you must file federal Form 941, Employer’s Federal Tax Return, which details the number of employees who received wages, tips, or other compensation for the quarter. In Chapter 4, you can see what the form looks like. Table 5-1 shows you what months are reported during each quarter and when the reports are due. Table 5-1 Filing Requirements for Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return (Form 941) Months in Quarter Report Due Date January, February, March On or before April 30 April, May, June On or before July 31 July, August, September On or before October 31 October, November, December On or before January 31 The following key information must be included on Form 941: ✓ Number of employees who received wages, tips, or other compensation in the pay period ✓ Total of wages, tips, and other compensation paid to employees ✓ Total tax withheld from wages, tips, and other compensation ✓ Taxable Social Security and Medicare wages ✓ Total paid out to employees in sick pay ✓ Adjustments for tips and group-term life insurance ✓ Amount of income tax withholding Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes 113 ✓ Advance earned income credit payments made to employees (see Chapter 4 for an explanation) ✓ Amount of tax liability per month Knowing how often to file As an employer, you file Form 941 on a quarterly basis, but you may have to pay taxes more frequently. Most new employers start out making monthly deposits for taxes due by using Form 8109 (shown in Chapter 4), which is a payment coupon that your company can get from a bank approved to collect deposits or from the Federal Reserve branch near you. Others make deposits online by using the IRS’s Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). For more information on EFTPS, go to www.eftps.gov. Employers on a monthly payment schedule (usually small companies) must deposit all employment taxes due by the 15th day of the following month. For example, the taxes for the payroll in April must be paid by May 15. Larger employers must pay taxes more frequently, depending on the number of workers employed and the dollar amount of payroll. Completing Unemployment Reports and Paying Unemployment Taxes As an employer, you’re responsible for paying a share of unemployment compensation based on your record of firing and laying off employees. The fund you pay into is known as the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) fund. For FUTA, employers pay a percentage rate based on each employee’s earnings. The employee earnings are capped at a certain dollar amount. So, even though each employee earns a different level of salary, FUTA taxes are calculated only on the first dollars each employee earns. As of this writing, the cap for FUTA taxes is on the first $7,000 of income. States also collect taxes to fill their unemployment fund coffers. The federal government allows you to subtract a portion of the state unemployment payments from your federal contributions. Essentially, the amount you pay to the state can serve as a credit toward the amount you must pay to the federal government. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 114 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Each state sets its own unemployment tax rate. Many states also charge additional fees for administrative costs and job-training programs. You can check out the full charges for your state at payroll-taxes.com. How states calculate the FUTA tax rate States use four different methods to calculate how much you may need to pay in FUTA taxes: ✓ Benefit ratio formula: The state looks at the ratio of benefits collected by former employees to your company’s total payroll over the past three years. States also adjust your rate depending upon the overall balance in the state unemployment insurance fund. ✓ Benefit wage formula: The state looks at the proportion of your company’s payroll that’s paid to workers who become unemployed and receive benefits, and then divides that number by your company’s total taxable wages. ✓ Payroll decline ratio formula: The state looks at the decline in your company’s payroll from year to year or from quarter to quarter. ✓ Reserve ratio formula: The state keeps track of your company’s balance in the unemployment reserve account, which gives a cumulative representation of its use by your former employees who were laid off and paid unemployment. This recordkeeping dates back from the date you were first subject to the state unemployment rate. The reserve account is calculated by adding up all your contributions to the account and then subtracting total benefits paid. This amount is then divided by your company’s total payroll. The higher the reserve ratio, the lower the required contribution rate. These formulas can be very complicated, so your best bet is to contact your state’s unemployment office to review how your company’s unemployment rate will be set. In addition to getting a better idea of what may impact your FUTA tax rate, you can also discuss how best to minimize that rate. Calculating FUTA tax After you know what your rate is, calculating the actual FUTA tax you owe isn’t difficult. Here’s what you do: 1. Multiply $7,000 by the federal unemployment tax rate to determine how much you owe per employee in federal unemployment. That $7,000 is the cap on earnings, which was discussed earlier. Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes 115 2. Multiply the result from Step 1 by the number of employees to determine the total federal unemployment tax you owe. If the state rate is lower than the federal rate, you’re done. You pay the federal program the federal calculation, less the amount you pay into the state unemployment fund. If the state rate is higher than the federal rate, proceed to Step 3. 3. Subtract the state rate from the federal rate. 4. Multiply the result from Step 3 by $7,000 to determine the additional amount of state unemployment tax you must pay per employee. 5. Multiply the result from Step 4 by the number of employees. 6. Add the amounts from Steps 2 and 5. Here’s an example, assuming a state tax rate of 2.7 percent and a federal rate of 6.2 percent: State unemployment taxes: $7,000 × 0.027 = $189 per employee $189 × 10 employees = $1,890 Federal unemployment taxes: $7,000 × 0.062 = $434 $434 × 10 employees = $4,340 Because the federal rate is higher than the state rate, you can subtract the amount in state unemployment tax you owe from the total. In this case, you would pay $1,890 to the state, and $2,450 ($4,340 – $1,890) to the federal unemployment fund. Each year, you must file IRS Form 940 Federal Unemployment (FUTA) Tax Return, shown in Figure 5-1. You can find Form 940 online at www.irs.gov/ pub/irs-pdf/f940.pdf. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 116 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 5-1: Employers report their FUTA tax on Form 940. Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes 117 Book II Recording Accounting Transactions Figure 5-1: (continued) Courtesy of IRS You can pay taxes for Form 940 by using the same coupon (Form 8109) used to pay Form 941 taxes (see “Filing Form 941” earlier in this chapter for an ­explanation). Most employers pay unemployment taxes quarterly. 118 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Filing and paying unemployment taxes to state governments Many states collect their unemployment taxes on a quarterly basis, and most states allow you to pay your unemployment taxes online. Check with your state to find out how to file and make unemployment tax payments. Unfortunately, the filing requirements for state unemployment taxes may be more difficult to complete than those for federal taxes (see the discussion of Federal Form 940 in the previous section). States require you to detail each employee by name and Social Security number. The state must know how much an employee was paid each quarter in order to determine his or her unemployment benefit, if the need arises. Some states also require you to report the number of weeks an employee worked in each quarter because the employee’s unemployment benefits are calculated based on the number of weeks worked. Each state has its own form and filing requirements. Some states require a detailed report as part of your quarterly wage and tax reports. Other states allow a simple form for state income tax and a more detailed report with your unemployment tax payment. Carrying Workers’ Compensation Insurance Taxes aren’t the only thing you need to worry about when figuring out your state obligations after hiring employees. Nearly every state requires employers to carry workers’ compensation insurance, which covers your employees in case they’re injured on the job. If an employee gets hurt on the job, workers’ compensation covers costs of lost income, medical expenses, vocational rehabilitation, and, if applicable, death benefits. Each state sets its own rules regarding how much medical coverage you must provide. If the injury also causes the employee to miss work, the state determines the percentage of the employee’s salary you must pay and how long you pay that amount. If the injury results in the employee’s death, the state also sets the amount you must pay toward funeral expenses and the amount of financial support you must provide the employee’s family. Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes 119 Each state makes up its own rules about how a company must insure itself against employee injuries on the job. Some states create state-based workers’ compensation funds to which all employers must contribute. Other states allow you the option of participating in a state-run insurance program or buying insurance from a private company. A number of states permit employers to use HMOs, PPOs, or other managed-care providers to handle workers’ claims. If your state doesn’t have a mandatory state pool, you have some other resources to obtain workers’ compensation insurance coverage. States set the requirements for coverage, and either a national rating bureau called the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI) or a state rating bureau establishes the premiums. For the lowdown on NCCI and workers’ compensation insurance, visit www.ncci.com. You may find lower rates over the long term if your state allows you to buy private workers’ compensation insurance. Many private insurers give discounts to companies with good safety standards in place and few past claims. So the best way to keep your workers’ compensation rates low is to encourage safety and minimize your company’s claims. Your company’s rates are calculated based on risks identified in two areas: ✓ Classification of the business: These classifications are based on historic rates of risk in different industries. For example, if you operate a business in an industry that historically has a high rate of employee injury, such as a construction business, your base rate for workers’ compensation insurance is higher than that of a company in an industry without a history of frequent employee injury, such as an office that sells insurance. ✓ Classification of the employees: The NCCI publishes classifications of hundreds of jobs in a book called the Scopes Manual. Most states use this manual to develop the basis for their classification schedules. For example, businesses that employ most workers at desk jobs pay less in workers’ compensation than businesses with a majority of employees operating heavy machinery. Be careful how you classify your employees. Many small businesses pay more than needed for workers’ compensation insurance because they misclassify employees. Be sure you understand the classification system and properly classify your employee positions before applying for workers’ compensation insurance. Be sure to read the information at www. ncci.com before classifying your employees. Book II Recording Accounting Transactions 120 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions When computing insurance premiums for a company, the insurer (whether the state or a private firm) looks at employee classifications and the rate of pay for each employee. For example, consider the position of an administrative assistant who earns $25,000 per year. If that job classification is rated at 29 cents per $100 of income, the workers’ compensation premium for that employee is: ($25,000 ÷ 100) × 0.29 = $72.50 Most states allow you to exclude any overtime paid when calculating workers’ compensation premiums. You may also be able to lower your premiums by paying a deductible on claims. A deductible is the amount you would have to pay before the insurance company pays anything. Deductibles can lower your premium by as much as 25 percent, so consider that as well to keep your upfront costs low. Maintaining Employee Records When you consider all the state and federal filing requirements for employee taxes that you must keep, it’s clear that you must have very good employee records. Otherwise, you’ll have a hard time filling out all the necessary forms and providing detail on your employees and your payroll. The best way to track employee information is to set up an employee journal and create a separate journal page for each employee. You can set this up manually, or through an automated accounting system. The detailed individual records you keep on each employee should include this basic information, most of which is collected or determined as part of the hiring process: ✓ Name, address, phone number, and Social Security number ✓ Department or division within the company ✓ Start date with the company ✓ Pay rate ✓ Pay period (weekly, biweekly, semimonthly, or monthly) ✓ Whether hourly or salaried ✓ Whether exempt or nonexempt ✓ W-4 withholding allowances ✓ Benefits information ✓ Payroll deductions ✓ All payroll activity Chapter 5: Computing and Reporting Payroll Taxes 121 If an employee asks to change the number of withholding allowances and file a new W-4 or asks for benefits changes, his or her record must be updated to reflect such changes. The personal detail that doesn’t change each pay period should appear at the top of the journal page. Then, you divide the remaining information into ­columns. Here’s a sample showing what the top of an employee’s journal page may look like. Name: SS#: Address: Tax Info: Married, 2 WH Pay Information: $8 hour, nonexempt, biweekly Benefits: None Book II Recording Accounting Transactions The following is an example of the body of the journal page. It contains columns for date of check, taxable wages, Social Security and Medicare tax (in one total), federal tax withholding, state tax withholding, and the net check amount. Date 4/8/2015 4/22/2015 Taxable Wages $640 640 SS & Med $39.68 38.68 Fed WH $9.28 9.28 State WH $8.62 8.62 Check $582.42 582.42 You may want to add other columns to your employee journal to keep track of things such as ✓ Non-taxable wages Examples include health or retirement benefits that are paid before taxes are taken out. ✓ Benefits If the employee receives benefits, you need at least one column to track any money taken out of the employee’s check to pay for those benefits. In fact, you may want to consider tracking each benefit in a separate column. Check out Chapter 4 for more on benefits. ✓ Sick time ✓ Vacation time 122 Book II: Recording Accounting Transactions Clearly, these employee journal sheets can get very lengthy very quickly. That’s why many small businesses use computerized accounting systems to monitor both payroll and employee records. Figures 5-2 and 5-3 show you how a new employee is added to the QuickBooks system. Figure 5-2: New employee personal and contact information can be added in QuickBooks to make it easier to keep track of employees. Figure 5-3: QuickBooks enables you to track salary and deduction information, as well as information about sick time and vacation time. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries Check out www.dummies.com/extras/accountingaio for specifics on how to adjust your accounting records with accruals and deferrals. In this book… ✓ Choose the best depreciation method for your long-term assets. Assets are used to generate revenue, and depreciation expenses the cost of the asset as it’s used in business. ✓ Account for interest your business pays or receives. If your business borrows or lends money, it pays or collects interest. Either way, you need to account for that interest. ✓ Prove out the cash to ensure that what’s on paper matches the real dollar amounts in a store or office. Your cash account typically has a lot of transactions. As a result, you need to carefully account for cash to ensure that all the activity is properly recorded. ✓ Reconcile accounts and confirm that your journals and general ledger are correct. Reconciling your books is a great way to check your work, correct any errors, and even spot signs of fraud! ✓ Double-check your books by running a trial balance, correct any errors, and prepare a financial statement worksheet. A trial balance lists all your accounts and their dollar balances. ✓ Adjust the books in preparation of preparing financial reports. Trial balances are adjusted before being used to create financial statements to ensure accuracy in financial reports. Chapter 1 Depreciating Your Assets In This Chapter ▶ Understanding depreciation: What you do and why you do it ▶ Exploring depreciation methods ▶ Looking at depreciation’s tax impact A ll businesses have fixed assets — equipment, furnishings, and vehicles that last more than a year. Although they may last longer than other assets, even fixed assets eventually wear out or become obsolete and need replacing. Of course, fixed assets, like other assets, are an expense, but because fixed assets last longer, you have options in how you account for those expenses. For example, you may choose to deduct the entire cost of a fixed asset the year you purchase it. Another option is to use a method called depreciation to write off the cost of the asset over several years or perhaps even over the life of that asset. Each option has its benefits and drawbacks. This chapter introduces you to the various ways you can depreciate your assets and explains how to choose a depreciation method, calculate depreciation, and reap its tax benefits. Changes in the tax law may also impact your decisions about depreciation. Defining Depreciation Accountants use depreciation as a way to allocate the costs of a fixed asset over the period in which the asset is useable to the business. You, the accountant, normally record the full cost of the asset when the asset is purchased. Subtracting a portion of that value as a depreciation expense each year gradually reduces the value of the asset. 126 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Depreciation expenses don’t involve the exchange of cash; they’re solely done for accounting purposes . . . and to reap tax benefits. Most companies enter depreciation expenses into the books once a year just before preparing their annual reports, but others calculate depreciation expenses monthly or quarterly. One key reason to write off assets is to lower your tax bill, so the IRS gets involved in depreciation, too. As a business owner, you probably won’t be able to write off the cost of all major purchases in one year. The IRS has strict rules about how you can write off assets as tax-deductible expenses. For more about the IRS’s rules, see “Tackling Taxes and Depreciation,” later in this chapter. Knowing what you can and can’t depreciate Businesses don’t depreciate all assets. Low-cost items or items that aren’t expected to last more than one year are expensed immediately. In other words, these items aren’t recorded as assets. For example, office supplies are expense items and not depreciated, but that office copier, which you’ll use for more than one year, is recorded in the books as a fixed asset and depreciated each year over the course of its expected useful life. Lifespan isn’t the deciding factor for depreciation, however. Some assets that last many years are never depreciated. One good example is land; you can always make use of land, so its value never depreciates. You also can’t depreciate any property that you lease or rent. If you make improvements to leased property, however, you can depreciate the cost of those improvements. In that case, you write off the lease or rent as an expense item and depreciate the lease improvements over their estimated useful life. You can’t depreciate any items that you use outside your business, such as your personal car or home computer. If you use these assets for both personal needs and business needs, you can depreciate a portion of them based on the percentage of time or other measurement that proves how much you use the car or computer for business. For example, the portion of a car that can be depreciated can be based on the miles driven for business versus the miles driven for personal use. If you drive your car a total of 12,000 miles in a year and have records showing that 6,000 of those miles were for business purposes, you can depreciate 50 percent of the cost of the car. That percentage is allocated over the anticipated useful life of the car. Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets 127 Another example of depreciation of a dual-usage asset is a room in your home designated exclusively for your business. You may be able to depreciate a portion of your home’s cost as part of your business expenses. The amount you can depreciate is based on the portion of your home used for business. Figuring out the useful life of a fixed asset You’re probably wondering how you figure out the useful life of a fixed asset. Well, the IRS has done the dirty work for you by creating a chart that spells out the recovery periods allowed for business equipment (see Table 1-1). Recovery periods are the anticipated useful lifespan of a fixed asset. For example, cars generally have a five-year recovery period because the IRS anticipates that they’ll have a useful lifespan of five years. Although the car will probably run longer than that, you’re not likely to continue using that car for business purposes after the first five years. You’re more likely to trade it in and get a new car. Table 1-1 Depreciation Recovery Periods for Business Equipment Property Class Recovery Period Business Equipment Book III 3-year property Tractor units and horses over two years old 5-year property Cars, taxis, buses, trucks, computers, office machines (faxes, copiers, calculators), research equipment, and cattle Adjusting and Closing Entries 7-year property Office furniture and fixtures 10-year property Water transportation equipment, singlepurpose agricultural or horticultural structures 15-year property Land improvements, such as shrubbery, fences, roads, and bridges 20-year property Farm buildings that aren’t agricultural or horticultural structures 27.5-year property Residential rental property 39-year property Nonresidential real estate, including a home office but not including the value of the land 128 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Delving into cost basis In order to calculate depreciation for an asset, you need to know the cost basis of that asset. Cost basis represents all the costs you incur to use the asset in your business. You use assets to make money — to make a product or service to sell. The equation for cost basis is: Cost of the fixed asset + Sales tax + Shipping and delivery costs + Installation charges + Other costs = Cost basis ✓ Cost of the fixed asset: What you paid for the equipment, furniture, structure, vehicle, or other asset. ✓ Sales tax: What you were charged in sales tax to buy the fixed asset. ✓ Shipping and delivery costs: Any shipping or delivery charges you paid to get the fixed asset. ✓ Installation charges: Any charges you paid in order to have the equipment, furniture, or other fixed asset installed on your business’s premises. ✓ Other costs: Any other charges you need to pay to make the fixed asset usable for your business. For example, if you buy a new computer and need to set up certain hardware in order to use that computer for your business, those setup costs can be added as part of the cost basis of the fixed asset (the computer). Training costs may also be part of your cost basis. For additional details on how to determine which costs can be included in depreciation, see Book VIII, Chapter 1. Evaluating Your Depreciation Options For the purposes of this book, you may choose from among four methods of depreciation. Three are based on time: straight-line, declining balance, and sum-of-the-years’-digits. The fourth method, units-of-production, is based on actual physical usage of the fixed asset. Here’s a brief explanation of each: ✓ Straight-line method: This method spreads out the cost of the fixed asset evenly over its useful life. ✓ Declining balance method: This is an accelerated method of depreciation, meaning the depreciation expense is higher in the earlier years of ownership. Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets 129 ✓ Sum-of-the-years’-digits method: This is another accelerated method of depreciation. With this method, you figure depreciation expense by assigning numbers (in declining order) to each year of the fixed asset’s expected useful life. For example, an asset used for three years would require this calculation: 3 + 2 + 1 = 6. Your depreciation rate for any given year is the year’s assigned number divided by that sum, so the year 1 rate would be 3/6 (or 1/2). ✓ Units-of-production method: Using this method, you compare the total estimated number of units the fixed asset will produce over its expected useful life to the number of units produced in the current accounting period. Depletion, which is the annual expense for the use of natural resources, is also based on actual physical usage. Examples of natural resources subject to depletion are oil, timber, and minerals. Don’t worry; the sections that follow walk you through a detailed example of each of the previously listed methods of depreciation. And to show how the choice of a depreciation method affects the amount of depreciation expense taken each year, each example uses the same asset facts and circumstances. For the purposes of calculating depreciation in this chapter, here are the facts and circumstances for your sample fixed asset — a delivery van that the company buys on January 1, 2015: ✓ The cost basis of the asset: The earlier section “Delving into cost basis,” explains which costs to include in the cost basis — the total cost of the fixed asset. The cost base of the delivery van is $30,000. ✓ How long the company anticipates being able to use the fixed asset: The company may measure the length in years, in production hours, or in miles driven. For this example, the business anticipates using the delivery van for 5 years or 50,000 miles. ✓ The value of the asset after the company is done using it (known as its salvage value): The salvage value is an estimate that management makes for how much the fixed asset will be worth when it’s retired. When the delivery van is replaced, the company anticipates receiving $3,000 in trade-in value. Cost basis less the salvage value equals depreciable base. Consider depreciable base to be the dollar amount you use to compute depreciation. ✓ The depreciation method the company uses: The method the business uses to depreciate should be appropriate for the asset. Accountants apply the matching principle to match revenue with the expense incurred to generate the revenue. For financial accounting, the standard of appropriateness is met if the company uses the method that most closely matches expenses to revenue. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 130 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries A business can’t arbitrarily switch methods after using one depreciation method for an asset. To do so would be a change in accounting method. If you do choose to change an accounting method, you need to justify the change (see Book I, Chapter 4 for more on selecting accounting methods). ✓ Date of purchase and whether the company is on a calendar or fiscal year-end: The date is when the fixed asset is ready for use. Calendar year-end is on December 31. A fiscal year ends on the last day of any other month of the company’s choosing during the year. For example, a fiscal year can be April 1 through March 31. This business has a calendar year-end of December 31. The delivery van is purchased on January 1. Ready? Well, start your engines and let’s depreciate this delivery van! Walking through the straight-line method When using the straight-line method, the salvage value reduces the depreciable base. So the cost of the delivery van ($30,000) less its salvage value ($3,000) gives you a depreciable base of $27,000. The expected useful life is 5 years. So depreciation expense for the van is $27,000/5 or $5,400 depreciation expense per year for each of the 5 years. Book value at the end of year 5 is $3,000. Accelerating by using declining balance To depreciate an asset more quickly during the earlier years of its use (than by using the straight-line method), you can use a declining balance method. Several declining-balance methods are available, but the double-declining balance method is used most often. It enables you to depreciate an asset at twice the rate of the straight-line method. The double-declining balance method is ideal for assets whose primary usefulness is in the early years of life. To calculate depreciation by using the double-declining balance method, use this formula: 2 × ( 1 ÷ Estimated useful life) × Book value at the beginning of the year = Depreciation expense Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets 131 Note that double-declining balance calculates depreciation on cost ($30,000), not depreciable base ($27,000). Also, the straight-line method spreads depreciation evenly over 5 years, or 20 percent a year. Double-declining balance multiplies the cost by 40 percent — twice the 20 percent rate. The calculation for the van’s depreciation expense in the first year, using the declining balance method, is: 2 × (1 ÷ 5) × $30,000 = $12,000 At the beginning of the second year, you need to reduce the value of the asset by the year one depreciation amount; in this example, $30,000 – $12,000 = $18,000. $18,000 is your new book value. In other words, $18,000 is the amount you plug into the formula to get year two depreciation. Plug that number into the formula, and you get: 2 × (1 ÷ 5) × $18,000 = $7,200 Perform the same calculation for the remaining years of useful life, and the five-year depreciation looks like this: ✓ Year 1: $12,000 ✓ Year 2: $7,200 Book III ✓ Year 3: $4,320 Adjusting and Closing Entries ✓ Year 4: $2,592 ✓ Year 5: $888 If you add the 5 years of depreciation in this example, the total is $27,000. You’ve seen the number before: $30,000 cost less $3,000 salvage value. Your total depreciation using double-declining balance can’t be more than cost less salvage value. When you reach salvage value, you sell the asset. So, depreciation stops at that point. Figure 1-1 shows how to figure double-declining balance depreciation. Note that in year 5, the 40 percent depreciation rate doesn’t matter because you have to limit the depreciation to salvage value. Because the ending net book value is $3,888 in year 4, depreciation is limited to $888 in year 5. 132 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Figure 1-1: A doubledeclining balance depreciation calculation. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Calculating sum-of-the-years’-digits Like all methods of depreciation, the sum-of-the-years’-digits method of depreciation bases the depreciation rate on the useful life of the asset, but with a twist. Using this method, you depreciate the asset by adding the useful life years together (5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 15) to get the denominator for the rate fraction. The numerator is the number of years remaining in the depreciation schedule. In year one, your multiplier is 5/15 (1/3); in year two, the multiplier is 4/15; and so on. As with straight-line depreciation, you back out the salvage value before you start, so in this example, you start with $30,000 – $3,000 = $27,000. The depreciation expense for the first year is: $27,000 × 5/15 or 1/3 = $9,000 So here’s how sum-of-the-years’-digits depreciation expense plays out for the delivery van over 5 years: ✓ Year 1: $27,000 × 5/15 = $9,000 depreciation expense ✓ Year 2: $27,000 × 4/15 = $7,200 depreciation expense ✓ Year 3: $27,000 × 3/15 = $5,400 depreciation expense ✓ Year 4: $27,000 × 2/15 = $3,600 depreciation expense ✓ Year 5: $27,000 × 1/15 = $1,800 depreciation expense Check the math: Adding up all five years of depreciation expense equals $27,000, which is the cost of the delivery van less the salvage value! Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets 133 Using the units-of-production method The units of production (UOP) method of depreciation works well primarily in a manufacturing environment because it calculates depreciation based on the number of units produced in a year. Companies whose machinery usage varies greatly each year depending on the market and the number of units needed for sale make use of this depreciation method. Finally, this method helps you match an expense (depreciation expense) with revenue (sales of the items produced). The matching principle is mentioned earlier in this chapter. The formula for calculating depreciation by using units of production is a two-step process: 1. Find the UOP rate by using this formula: (Cost – Salvage value) ÷ Estimated number of units to be produced during estimated useful life = UOP rate 2. Find the depreciation expense by using this formula: Units produced during the year × UOP rate = Depreciation expense You need to use the units-of-production depreciation method only if you’re manufacturing the products you sell and the usage of your equipment fluctuates widely from year to year. Here’s how this method works with the delivery van purchase example: The business anticipates using the delivery van for 50,000 miles over the course of the 5 years when a depreciation expense is to be deducted. First, find the cost of the delivery van less salvage value: $30,000 – $3,000 = $27,000. Divide this figure by your anticipated usage: $27,000/50,000 miles equals $0.54 per mile. If the van travels 8,000 miles in any given year, the depreciation expense for that year is: 8,000 × $0.54 = $4,320 In essence, using this method for the delivery van is giving you a standard mileage rate. If you’ve ever done your own tax return and had to figure your mileage expense for charitable work you’ve done, it’s the same concept. Seeing how the methods compare Just for fun, Figure 1-2 shows how the different depreciation methods result in a different amount of depreciation expense per year. Notice that over the entire 5-year useful life, total depreciation is $27,000 regardless of the method Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 134 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries used. Thus, the different methods result in different depreciation expense amounts in each of the years but not in a difference in total depreciation over the life of the asset. Figure 1-2: Comparison of depreciation expense among methods. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Pretty cool, huh?! Depending on the depreciation method the company uses for the fixed asset, depreciation expense can be all over the map. A business can use a different depreciation method for different types of assets as long as the depreciation method fairly shows the use of the asset over time. More depreciation expense in an accounting period results in less net income, and vice versa. Chapter 1: Depreciating Your Assets 135 Figuring partial year depreciation The delivery van example was neat and clean because the company purchased the van on January 1 (the first day of its fiscal year). What happens if the company buys a fixed asset mid-year? How do you figure depreciation expense for a partial year? Here’s the solution: You prorate the depreciation expense among the accounting periods involved. For example, if the sample company buys a delivery van on June 1, the first year of depreciation is prorated by using the fraction 7/12 (because seven months remain in the fiscal year). Any leftover depreciation is taken in year 6. Consider the delivery van while using the straight-line method. Depreciation expense in year 1 is now $3,150 ($5,400 × 7/12). For years 2 through 5, the depreciation expense remains $5,400. In year 6, you finish up by expensing the remaining $2,250 ($5,400 × 5/12). The journal entry (see Book I, Chapter 3) to book depreciation is to debit depreciation expense and credit accumulated depreciation. Tackling Taxes and Depreciation Depreciation calculations for tax purposes are a completely different animal from the calculations used to record depreciation for accounting purposes. You can use straight-line depreciation to calculate your depreciation expense for book (accounting record) purposes. Many businesses, however, use an accelerated method of depreciation for tax purposes. These companies prefer to write off the highest expense legally permissible and reduce their tax bills by the greatest amount as soon as possible. Accountants reconcile differences between the accounting records (“book”) and the tax return (“tax”). You may hear accountants discussing book versus tax issues. One issue that causes these differences is the treatment of depreciation. The reconciliation process isn’t discussed in this book, but you should keep this concept in mind. In addition to straight-line depreciation, two other acceptable IRS methods for writing off assets are: Section 179 and Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS). The big advantage of the Section 179 Deduction is that you can write off up to 100 percent of the cost basis of qualifying property. If the property doesn’t qualify under Section 179, many businesses choose to use MACRS rather than straight-line depreciation. (The following sections describe Section 179 and MACRS depreciation in greater detail.) Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 136 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Section 179 Section 179, which gets its name from a section of the tax code, is a great boon for companies. Businesses can write off up to 100 percent of the full purchase price of the property. The primary reason for this part of the tax code is to encourage businesses to buy new property in order to stimulate the economy. That’s why only certain types of property are included, and the tax code limits the amount that can be deducted for some types of property. Basically, Section 179’s qualifying property includes tangible property such as machines, equipment, and furniture. In addition, some storage facilities qualify. Cars and SUVs between 6,000 and 14,000 pounds can be partially written off under Section 179. You can get full details about Section 179 by ordering a copy of IRS Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property, from the IRS or accessing it online at www.irs.gov. If you’re a business owner, work with your accountant to determine what’s eligible and how much of the cost basis is eligible for the Section 179 deduction. MACRS The most common type of depreciation write-off used by businesses is Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System, or MACRS. The recovery period shown in Table 1-1 is the basis for this depreciation method. After you know what type of property you have (three-year, five-year, and so on), you use the MACRS table in IRS Publication 946, How to Depreciate Property, to figure out the depreciation expense you can write off. If you’re a business owner, you can leave MACRS calculations for your accountant to do when he prepares your business tax forms. Chapter 2 Paying and Collecting Interest In This Chapter ▶ Understanding interest calculations ▶ Making the most of interest income ▶ Calculating loan interest F ew businesses are able to make major purchases without taking out loans. Whether loans are for vehicles, buildings, or other business needs, businesses must pay interest, a percentage of the amount loaned, to their lenders. Some businesses also loan money to borrowers and receive interest payments as income. In fact, a savings account can be considered a type of loan because by placing your money in the account, you’re giving the bank the opportunity to loan that money to others. That interest is income for your company. This chapter reviews different types of loans and how to calculate and record interest expenses for each type. It also explains how you calculate and record interest income in your business’s books. Deciphering Types of Interest Any time you make use of someone else’s money (whether that someone else is an individual or a bank), you have to pay interest for that use — whether you’re buying a house, a car, or some other item you want. The same is true when someone else is using your money. For example, when you buy a corporate bond or deposit money in a money market account, you’re paid interest for allowing someone to use your funds. The financial institution that has your money will likely combine your money with that of other depositors and loan it to other people to make more interest than it’s paying you. A corporation will use the proceeds from the bond issue to finance its business’s expansion. The company wants to generate more in earnings than it will pay in interest expense. 138 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Financial institutions use two types of interest calculations: ✓ Simple interest is calculated only on the principal amount of the loan. ✓ Compound interest is calculated on the principal and on the interest previously earned. Simple interest Simple interest is simple to calculate. Here’s the formula for calculating simple interest: Principal × Interest rate × n = Interest The n in the equation stands for number of periods. To understand how interest is calculated, assume that someone deposited $10,000 in the bank in a money market account earning 3 percent (0.03) interest for three years. So the interest earned over three years is $10,000 × 0.03 × 3 = $900. Compound interest Compound interest is computed on both the principal and any interest earned. You must calculate the interest each year and add it to the balance before you can calculate the next year’s interest payment, which will be based on both the principal and the interest earned. Here’s how you would calculate compound interest: Principal × Interest rate (Principal + Year one interest earned) × Interest rate (Principal + Years one and two interest earned) × Interest rate = = Interest for year one Interest for year two = Interest for year three You repeat this calculation for all years of the deposit or loan. Compound interest assumes that interest payments are reinvested and earn additional interest. Compounding means that you’re earning interest on a larger investment amount. To understand how compounding interest impacts your earnings, notice how the amount of interest changes from one year to the next on a three-year deposit of $10,000 at 3 percent (0.03): Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest $10,000 × 0.03 ($10,000 + 300) × 0.03 ($10,000 + 300 + 309) × 0.03 Total interest earned = = = = 139 $300.00 (Year one interest) $309.00 (Year two interest) $318.27 (Year three interest) $927.27 You can see that you earn an extra $27.27 during the first three years of the deposit if interest is compounded. When working with much larger sums or higher interest rates for longer periods of time, compound interest can make a big difference in how much you earn or how much you pay on a loan. The Rule of 72 is a tool you can use to remember how compound interest works. Seventy-two divided by the rate of compound interest gives you the number of years it will take for your money to double. For example, if the rate of compound interest is 6 percent, your money will double in 72 ÷ 6, or 12 years. The higher the compound interest rate, the faster your money will double. At 12 percent, your money doubles in 72 ÷ 12, or 6 years. Ideally, you want to find a savings account, certificate of deposit, or other savings instrument that earns compound interest. But if you want to borrow money, look for a simple interest loan (see the previous section). Also, not all accounts that earn compound interest are created equally. Watch carefully to see how frequently the interest is compounded. The preceding example assumes that interest is compounded annually. But if you can put your money into an account that compounds interest monthly, the interest you earn will be even higher. Monthly compounding means that interest earned is calculated each month and added to the principal each month before calculating the next month’s interest, which results in a lot more interest than a bank that compounds interest just once a year. Likewise, opt for loans that compound interest annually instead of quarterly or monthly. Handling Interest Income The income that your business earns from its savings accounts, certificates of deposits, or other investment vehicles is called interest income. As the bookkeeper, you’re rarely required to calculate interest income by using the simple interest or compounded interest formulas described in the earlier sections of this chapter. In most cases, the financial institution sends you a monthly, quarterly, or annual statement that has a separate line item reporting interest earned. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 140 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries When you get your monthly statement, you then reconcile the books — your accounting records. Reconciliation is a process in which you prove out whether your bank balance (on the bank statement) is equal to the cash balance in your accounting records. For more about reconciling bank accounts, see Chapter 4. One step in the reconciliation process involves recording any bank activity that may not be posted to your books. Often, companies wait until they get the bank statement to post certain bank transactions. Two common transactions are interest earned and bank fees. You may post these entries after you receive the monthly bank statement. If you’re keeping the books manually, a journal entry to record interest income would look similar to this: Debit Cash Interest income To record interest income from American Savings Bank. Credit $100 $100 To record bank fees, you would debit (increase) an expense account and credit cash (a decrease). You pay bank fees in cash via your bank account. When preparing financial statements, you show interest income on the income statement in a section called other income (see Book IV, Chapter 2 for more information about the income statement). Other income includes any income your business earned that wasn’t directly related to your primary business activity — selling your goods or services. Delving into Loans and Interest Expenses Businesses borrow money for both short-term periods (less than 12 months) and long-term periods (more than 12 months). Short-term debt usually involves some form of credit card debt or line-of-credit debt. Long-term debt can include a five-year car loan, 20-year mortgage, or any other type of debt paid beyond one year. Short-term debt Any money due in the next 12-month period is shown on the balance sheet as short-term or current debt. Any interest paid on that money is shown as an interest expense on the income statement. Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest 141 For the purposes of this book, a current asset represents cash or items that will be converted to cash within one year. Current liabilities will be paid in cash within one year. In most cases, you don’t have to calculate your interest due. The financial institution sending you a bill gives you a breakdown of the principal and interest to be paid. Calculating credit card interest When you get a credit card bill at home, a line always shows you new charges, the amount to pay in full to avoid all interest, and the amount of interest charged during the current period on any money not paid from the previous bill. If you don’t pay your credit card in full, interest on most cards is calculated by using a daily periodic rate of interest, which is compounded each day based on the unpaid balance. When not paid in full, interest is calculated on the unpaid principal balance plus any unpaid interest. Table 2-1 shows what a typical interest calculation looks like on a credit card. Table 2-1 Credit Card Interest Calculation Average Daily Balance Daily Periodic Rate Corres-­ ­ponding Annual Rate Finance Charges Daily Rate Transaction Fees Purchases $1,000 0.033973% 12.40% $0.34 $50 Cash $200 0.045178% 16.49% $0.09 $20 On many credit cards, you start paying interest on new purchases immediately, if you haven’t paid your balance due in full the previous month. When opening a credit card account for your business, be sure you understand how interest is calculated and when the bank starts charging on new purchases. Some issuers give a grace period of 20 to 30 days before charging interest. In Table 2-1, the finance charges include the daily rate charged in interest based on the daily periodic rate plus any transaction fees. For example, if you take a cash advance from your credit card, many credit card companies charge a transaction fee of 2 to 3 percent of the total amount of cash taken. This fee may also apply when you transfer balances from one credit card to another. Although the company entices you with an introductory rate of 1 or 2 percent to get you to transfer the balance, be sure to read the fine print. You may have to pay a 3 percent transaction fee on the full amount transferred, which makes the introductory rate much higher. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 142 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Using credit lines As a small-business owner, you generally get better interest rates by using a line of credit with a bank than with a credit card. Interest rates are usually lower on lines of credit. Typically, a business owner uses a credit card for purchases, but if he can’t pay the bill in full, he draws money from his line of credit rather than carry over the credit card balance. When the money is first received from the credit line, you record the cash receipt and the liability. Just to show you how this transaction works, here’s a sample journal entry for the receipt of a credit line of $1,500: Debit Cash Credit line payable To record receipt of cash from credit line. Credit $1,500 $1,500 In this entry, you increase the cash account and the credit line payable account balances. When you make your first payment, you must record the use of cash, the amount paid on the principal of the loan, and the amount paid in interest. Here is what that journal entry looks like: Debit Credit line payable Interest expense Cash To make monthly payment on credit line. Credit $150 $10 $160 This journal entry reduces the amount due in the credit line payable account, increases the amount paid in the interest expense account, and reduces the amount in the cash account. If you’re using a computerized system, you simply complete a check form and indicate which accounts are impacted by the payment. The system updates the accounts automatically. When you prepare the check for printing in an automated system, you can add the accounts that are impacted by the payment. Your accounting system can then print the check and update all affected accounts. You don’t need to do any additional postings to update your books. Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest 143 Long-term debt Most companies take on some form of long-term debt — debt to be paid over a period longer than 12 months. This debt may include car loans, mortgages, or promissory notes. A promissory note is a written agreement stating that you agree to repay someone a set amount of money at some point in the future at a particular interest rate. The term can be monthly, yearly, or some other period specified in the note. Most installment loans are types of promissory notes. Recording a debt When the company first takes on a long-term debt, it’s recorded in the books in much the same way as a short-term debt: Debit Cash Notes payable To record receipt of cash from American Bank promissory note. Credit $500 $500 Book III Payments are also recorded in a manner similar to short-term debt: Debit Notes payable Interest expense Cash To record payment on American Bank promissory note. Credit $100 $5 $105 Although the way you enter the initial information isn’t very different, a big difference exists between how short- and long-term debts appear on the financial statements. All short-term debt appears in the current liability section of the balance sheet. Long-term debt is split and appears in different line items. The portion of the debt due in the next 12 months appears in the current liabilities section, which is usually a line item named something like “current portion of longterm debt.” The remaining balance of the long-term debt due beyond the next 12 months appears in the long-term liability section of the balance sheet as notes payable. Adjusting and Closing Entries 144 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Considering major purchases and long-term debt Sometimes a long-term liability is set up at the same time as you make a major purchase. You may pay some portion of the amount due in cash as a down payment and the remainder as a note. To see how to record such a transaction, assume that a business has purchased a truck for $25,000, made a down payment of $5,000, and signed a five-year (60 month) promissory note at an interest rate of 6 percent for $20,000. Here’s how you record this purchase in the books: Debit Vehicles Cash Notes payable – vehicles To record payment for the purchase of the blue truck. Credit $25,000 $5,000 $20,000 You then record payments on the note in the same way as you do on any other loan payment: Debit Notes payable – vehicles Interest expense Cash To record payment on the purchase of the blue truck. Credit $2,000 $300 $2,300 Separating principal and interest When recording the payment on a long-term debt for which you have a set installment payment, you may not get a breakdown of interest and principal with every payment. For example, when you take out a car loan, you may receive a coupon book with just the total payment due each month. Each payment includes both principal and interest, but you don’t get any breakdown detailing how much goes toward interest and how much goes toward principal, which may change with each payment. (With many loans, you pay a greater portion of interest earlier in the term, so banks can collect their interest earlier, and a greater portion of the principal with later payments.) In order to record long-term debt for which you don’t receive a breakdown each month, you need to ask the bank that gave you the loan for an amortization schedule, create your own amortization schedule, or enter the details of the loan into your accounting program. An amortization schedule lists the total payment, the amount of each payment that goes toward interest, the amount that goes toward principal, and the remaining balance to be paid on the note. Chapter 2: Paying and Collecting Interest 145 Some banks provide an amortization schedule automatically when you sign all the paperwork for the note. If your bank can’t give you one, you can easily generate one online by using an amortization calculator. BankRate.com has a good one at www.bankrate.com/brm/amortization-calculator.asp. Using that calculator, an amortization schedule is generated for the entire 60-month term of the loan showing the principal and interest breakdown for each payment. Table 2-2 displays payment information for each of the first six months. As you can see, the amount paid to principal on a long-term note gradually increases, while the amount of interest paid gradually decreases as the note balance is paid off. Table 2-2 Six-Month Amortization Chart for Truck Payments Total Payment Principal Interest Remaining Note Balance $386.66 $286.66 $100.00 $19,713.34 $386.66 $288.09 $98.57 $19,425.25 $386.66 $289.53 $97.13 $19,135.72 $386.66 $290.98 $95.68 $18,844.75 $386.66 $292.43 $94.22 $18,552.32 $386.66 $293.89 $92.76 $18,258.42 Book III Looking at the six-month amortization chart, here is what you would need to record in the books for the first payment on the truck: Debit Notes payable – vehicles Interest expense Cash To record payment on note for blue truck. Credit $286.66 $100.00 $386.66 In reading the amortization chart in Table 2-2, notice how the amount paid toward interest is slightly less each month as the balance on the note still due is gradually reduced. By the time you start making payments for the final year of the loan, interest costs drop dramatically because the principal balance is so much lower. As you lower your principal balance, much less of your payment goes toward interest and much more goes toward reducing principal. That’s why many financial specialists advise you to pay down principal as fast as possible if you want to reduce the term of a loan and, more importantly, the total amount you end up paying in interest. Adjusting and Closing Entries 146 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Chapter 3 Proving Out the Cash In This Chapter ▶ Understanding the purpose of closing out the cash ▶ Counting your company’s cash ▶ Finalizing the cash journals ▶ Using temporary posting journals A ll business owners — whether the business is a small, family-owned candy store or a major international conglomerate — like to p ­ eriodically verify how well their businesses are doing. They also want to be sure that the numbers in their accounting systems actually match what’s p ­ hysically in their stores and offices. After they check out what’s in the books, these business owners can prepare financial reports to determine the c ­ ompany’s financial ­success or failure during the last month, quarter, or year. This process of ­verifying the accuracy of your cash is called proving out the cash. This chapter explains how to ensure the cash counts are accurate, finalize the cash journals for the accounting period, prove out the bank accounts, and post any adjustments or corrections to the general ledger. Why Prove Out the Cash? You’re probably thinking that proving out the cash is a major, time-sucking endeavor. You’re right — it’s a big job, but it’s also a very necessary one to do periodically so you can be sure that what’s recorded in your accounting system realistically reflects what’s actually going on in your business. Any accounting system is susceptible to mistakes, and, unfortunately, any business can fall victim to incidents of theft or embezzlement. One way to minimize the risk is to periodically prove out the cash. The process of ­proving out the cash is a big part of the accounting cycle, discussed in detail in Book I, Chapter 1. 148 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries The first three steps of the accounting cycle — recording transactions, making journal entries, and posting summaries of those entries to the ­ general ledger — involve tracking cash flow throughout the accounting period. All three steps are part of the process of recording a business’s ­financial ­activities throughout the entire accounting period. The rest of the steps in the accounting cycle are conducted at the end of the period and are part of the process of proving out the accuracy of your books. They include running a trial balance and creating a worksheet (see Chapter 5), adjusting journal entries (see Chapter 6), creating financial ­statements (see Books IV and V), and closing the books (see Chapter 4). Most businesses prove out their books every month. Of course, you don’t want to shut down your business for a week while you prove out the cash, so select a day during each accounting period on which you’ll take a financial snapshot of the state of your accounts. The balance sheet is always generated on a specific day to provide a snapshot in time. The income statement, on the other hand, displays your profit and loss for a period of time (month or year). If you try to generate a balance sheet for the month of June, you’ll get an error message. Likewise, if you ask your system to produce an income statement for June 15, you’ll get another error message. If you’re preparing monthly financial reports at the end of the month, you test the amount of cash your business has on hand as of that certain time and day, such as 6 p.m. on June 30 after your store closes for the day. The rest of the testing process — running a trial balance, creating a worksheet, adjusting journal entries, closing the books, and creating financial statements — is based on what happened before that point in time. When you open the store and sell more products the next day and buy new things to run your business, those transactions and any others that follow your test become part of the next accounting cycle. Making Sure Ending Cash Is Right Testing your books starts with counting your cash. Why start with cash? Because, for most businesses, the cash account has more transactions than any other account. More transactions in an account can mean a higher risk of error. Cash is also the asset most susceptible to theft. If you prove your cash balance first, you’re addressing your most difficult account first. Before you can even begin to test whether the books are right, you need to know whether your books have captured what’s happened to Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash 149 your company’s cash and whether the amount of cash shown in your books actually matches the amount of cash you have on hand. Accountants spend a lot of time looking at business transactions and ­ onsidering which accounts are affected. When mulling over a transaction, c ask yourself: Did anything happen to cash? Because cash is so often affected by business activity, this approach helps you post the activity to the right accounts. Book II, Chapter 3 discusses how a business proves out the cash taken in by each of its cashiers. That process gives a business good control of the point at which cash comes in the door. The cashier accepts cash from customers who buy the company’s products or services. Cashiers also process cash refunds given to customers who returned items. So, proving cash handled by cashiers is important. But the points of sale and return aren’t the only times cash comes into or goes out of the business. If your business sells products on store credit (see Book II, Chapter 3), you (or the bookkeeping staff responsible for tracking customer credit accounts) collect some of the cash from customers at a later point in time. And when your business needs something, whether products to sell or s­ upplies for ­various departments, you must pay cash to vendors, suppliers, and ­contractors. Sometimes you pay cash on the spot, but many times you record the bill in the accounts payable account and pay it at a later date. Your amount of cash on hand at any one time includes not only what’s in the cash registers but also what’s on deposit in the company’s bank accounts. You need to know the balances of those accounts and test those balances to be sure they’re accurate and match what’s in your company’s books. Some departments may also have petty cash accounts, requiring that you total that cash as well. The total cash figure is what you report as an asset called “cash” on the first line of your company’s balance sheet. The balance sheet shows all that the company owns (its assets) and owes (its ­liabilities) as well as the equity the owners have in the company. (To find out more about the balance sheet and how you prepare one, see Book IV, Chapters 3–5.) The actual cash you have on hand is just one tiny piece of the cash moving through your business during the accounting period. The true detail of what cash has flowed into and out of the business is in your cash journals. Closing those journals is the next step in the process of figuring out how well your business is doing. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 150 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Closing the Cash Journals As explained in Book I, Chapter 3, you can find a record of every transaction that involves cash in one of two cash journals: the cash receipts journal (cash that comes into the business) and the cash disbursements journal (cash that goes out of the business). If you use a computerized accounting system, you have many additional ways to find the same information. You can run reports of sales by customer, item, or sales representative. You can also run reports that show you all the company’s purchases by vendor or item as well as list any purchases still on order. Cash receipts should be debited to increase cash. In the same way, cash disbursements are credited to reduce cash. If you identify all the cash receipts and disbursements, you should be able to match those transactions with the debits and credits. A typical automated accounting system can generate purchase reports. You can run these reports by the week, month, quarter, or year. You can also customize the reports to show a particular period of time that you’re analyzing. For example, if you want to know what purchases occurred between June 5 and 10, you can run a report specifying those exact dates. You have the same capability to generate sales reports. In addition to the sales and purchase reports, you can generate other transaction detail reports, including customers and receivables; jobs, time, and mileage; vendors and payables; inventory; employees and payroll; and banking. One big advantage of a computerized accounting system when you’re trying to prove out your cash is the number of different ways you can develop reports to check for accuracy in your books if you suspect an error. Although the ability to generate tons of information is great, try to avoid information overload. Get training on your accounting system so you can quickly access the most meaningful and useful reports. Knowing how to generate the most useful reports quickly will save you time. Don’t create ten sales reports if you use only two. Finalizing cash receipts If all your books are up-to-date, when you summarize the cash receipts journal to prove out your cash, you should come up with a total of all cash received by the business at that time. Up-to-date books ensure that all cash receipt transactions are posted to your accounting system. Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash 151 Unfortunately, in the real world of bookkeeping, things don’t always come out so nice and neat. In fact, you probably wouldn’t even start entering the transactions from that particular day into the books until the next day, when you enter the cash reports from all cashiers and others who handle incoming cash (such as the accounts receivable staff who collect money from customers buying on credit) into the cash receipts journal. After entering all the transactions from the day in question, the books for the period you’re looking at may still be incomplete. Sometimes, adjustments or corrections must be made to the ending cash numbers. For example, monthly credit card fees and interest received from the bank may not yet be recorded in your cash journals. As the bookkeeper or accountant, you must be sure that all bank fees are recorded to the cash disbursement journal. Interest earned is recorded in the cash receipts journal. After posting those entries, you can summarize the journals for the period you’re analyzing. Remembering credit card fees When your company allows customers to use credit cards, you must pay fees to the bank that processes these transactions, which is probably the same bank that handles all your business accounts. These fees actually lower the amount you take in as cash receipts, so the amount you record as a cash receipt must be adjusted to reflect those costs of doing business. Monthly credit card fees vary greatly depending upon the bank you’re using and other factors, but here are some of the most common fees your company should expect: ✓ Address verification service (AVS) fee is a fee companies pay if they want to avoid accepting fraudulent credit card sales. Businesses that use this service take orders by phone or e-mail and therefore don’t have the credit card in hand to verify a customer’s signature. Banks charge this fee for every transaction that’s verified. ✓ Chargeback and retrieval fees are charged if a customer disputes a transaction and wins the dispute. ✓ Customer support fees are charged to companies that want bank support for credit card transactions 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Companies such as mail-order catalogs that allow customers to place orders 24 hours a day look for this support. Sometimes companies even want this support in more than one language if they sell products ­internationally. ✓ Discount rate is a fee that all companies using credit cards must pay; it’s based on a percentage of the sale or return transaction. The rate your company may be charged varies greatly depending on the type of Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 152 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries ­ usiness you conduct and the volume of your monthly sales. Companies b that use a terminal to swipe cards and electronically send transaction information usually pay lower fees than companies that use paper credit card transactions, because the electronic route creates less work for the bank and eliminates the possibility of key-entry errors by employees. ✓ Equipment and software fees are charged to your company if you lease credit card equipment and related software from the bank. You may have the option of buying the equipment and software for a one-time charge instead. ✓ Monthly minimum fee is the least amount a business is required to pay for the ability to offer its customers the convenience of using credit cards to buy products. ✓ Secure payment gateway fee, which allows the merchant to process transactions securely, is charged to companies that transact business over the Internet. If your business sells products online, you can expect to pay this fee based on a set monthly amount. ✓ Transaction fee is a standard fee charged to your business for each credit card transaction you submit for authorization. You pay this fee even if the cardholder is denied and you lose the sale. Reconciling your credit card statements Each month, the bank that handles your credit card sales will send you a statement listing ✓ All your company’s transactions for the month. ✓ The total amount your company sold through credit card sales. ✓ The total fees charged to your account. If you find a difference between what the bank reports was sold on credit cards and what the company’s books show regarding credit card sales, it’s time to play detective and find the reason for the difference. In most cases, the error involves the charging back of one or more sales because a customer successfully disputes the charge. In this case, the cash receipts journal is adjusted to reflect that loss of sale, and the bank statement and company books should match up. For example, suppose $200 in credit card sales were disputed. The original entry of the transaction in the books should look like this: Sales Cash To reverse disputed credit card sales recorded in June. Debit $200 Credit $200 Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash 153 This entry reduces the total sales for the month as well as the amount of the cash account. If the dispute is resolved and the money is later retrieved, the sale is then reentered when the cash is received. You also record any fees related to credit card fees in the cash disbursements journal. For example, if credit card fees for the month of June total $200, the entry in the books should look like this: Credit card fees Cash To record credit-card fees paid for the month of June. Debit $200 Credit $200 Summarizing the cash receipts journal When you’re sure that all cash receipts as well as any corrections or ­adjustments to those receipts have been properly entered in the books (see the previous two sections), you summarize the cash receipts journal as explained in detail in Book I, Chapter 3. After summarizing the cash receipts journal for the accounting period you’re analyzing, you know the total cash that was taken into the business from sales as well as from other channels. A customer who buys a product either pays at the time of purchase or on credit. So, in the cash receipts journal, sales usually appear in two columns: ✓ Sales: The cash shown in the sales column is cash received when the customer purchases the goods by using cash, check, or bank credit card. ✓ Accounts receivable: The accounts receivable column is for sales in which no cash was received when the customer purchased the item. Instead, the customer bought on credit and intends to pay cash at a later date. (For more about accounts receivable and collecting money from customers see Book II, Chapter 3.) After you add all receipts to the cash receipts journal, entries for items bought on store credit can be posted to the accounts receivable journal and the individual customer accounts. You then send bills to customers that reflect all transactions from the month just closed as well as any payments still due from previous months. Billing customers is a key part of the closing process that occurs each month. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 154 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries In addition to the sales and accounts receivable columns, your cash receipts journal should have at least two other columns: ✓ General: The general column lists all other cash received, such as owner investments in the business. ✓ Cash: The cash column contains the total of all cash received by the business during an accounting period. Finalizing cash outlays After you close the cash receipts journal (see “Summarizing the cash receipts journal”), the next step is to close the cash disbursements journal. Any adjustments related to outgoing cash receipts, such as bank credit card fees, should be added to the cash disbursements journal. Before you close the journal, you must also be certain that any bills paid at the end of the month have been added to the cash disbursements journal. Bills that are related to financial activity for the month being closed but that haven’t yet been paid have to be accrued, which means recorded in the books, so they can be matched to the revenue for the month. These accruals are necessary only if you use the accrual accounting method. If you use the cash-basis accounting method, you need to record the bills only when cash is actually paid. For more on the accrual and cash-basis methods, flip to Book I, Chapter 4. You accrue bills yet to be paid in the accounts payable account. For example, suppose that your company prints and mails flyers to advertise a sale during the last week of the month. A bill for the flyers totaling $500 hasn’t been paid yet. Here’s how you enter the bill in the books: Advertising Accounts payable To accrue the bill from Jack’s printing for June sales flyers. Debit $500 Credit $500 This entry increases advertising expenses for the month and increases the amount due in accounts payable. When you pay the bill, the accounts payable account is debited (to reduce the liability), and the cash account is ­credited (to reduce the amount in the cash account). You make the actual entry in the cash disbursements journal when the cash is paid out. Chapter 3: Proving Out the Cash 155 When proving out the cash, also review any accounts in which expenses are accrued for later payment, such as sales tax collected, to be sure all accrual accounts are up-to-date. These tax accounts are actually liability accounts for taxes that will need to be paid in the future. If you use the accrual accounting method, the expenses related to these taxes must be matched to the revenues collected for the month they’re incurred. Using a Temporary Posting Journal Some companies use a temporary posting journal to record payments that are made without full knowledge of how the cash outlay should be posted to the books and which accounts will be impacted. For example, a company using a payroll service probably has to give that service a certain amount of cash to cover payroll even if it’s not yet known exactly how much is needed for taxes and other payroll-related costs. In this payroll example, cash must be disbursed, but transactions can’t be entered into all affected accounts until the payroll is done. Suppose a company’s payroll is estimated to cost $15,000 for the month of May. The company sends a check to cover that cost to the payroll service and posts the payment to the temporary posting journal. After the payroll is calculated and completed, the company receives a statement of exactly how much was paid to employees and how much was paid in taxes. After the statement arrives, allocating the $15,000 to specific accounts such as payroll expenses or tax expenses, that information is posted to the cash disbursements journal. If you decide to keep a temporary posting journal to track cash coming in or going out, before summarizing your cash disbursements journal and closing the books for an accounting period, be sure to review the transactions listed in the temporary posting journal that may need to be posted in the cash ­disbursements journal. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 156 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Chapter 4 Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries In This Chapter ▶ Reconciling accounts and making adjustments ▶ Confirming that your journals are correct ▶ Gathering journal information for closing ▶ Posting adjustments to the general ledger ▶ Examining your journals in a computerized system A s the old saying goes, “The devil is in the details.” When it comes to your bookkeeping, especially if you keep your books manually, those details are in the accounts and journals you keep. And any errors in those tiny details can lead to big problems down the road. To ensure accuracy, you must reconcile your accounts and prove out your journals and close them at the end of an accounting period, which is what this chapter is all about. Within these pages, you also find out how to post all corrections and adjustments to the general ledger after you make them in the appropriate journal. (To find out how to set up your journals, see Book I, Chapter 3.) Reconciling Bank Accounts Reconciling bank accounts involves verifying whether the cash balance in your accounting records agrees to the cash balance on your bank statement. Accountants use the phrase balance per book to refer to the cash balance in the accounting records. Balance per bank refers to your cash balance ­according to the bank statement. 158 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Table 4-1 walks you through the bank reconciliation process. You’ve p ­ robably reconciled your personal checking account at least a few times over the years, and you’ll be happy to hear that reconciling business accounts is a similar process that goes something like this: 1. Set up bank reconciliation template. Set up a template with two columns. The bank statement column represents bank activity and the cash account column lists information from your accounting records. Post the beginning balances at the top. The bank balance is taken from the bank statement. The cash balance is the ending balance from your cash account. 2. Mark cleared transactions. Compare the transactions in your cash accounting records with the bank statement and mark cleared transactions — transactions that appear both in the bank records and in your records. Because your book balance (accounting records) agrees with the bank statement, you don’t need to do anything further with these transactions. Note, however, that you’re not finished with the reconciliation process. 3. Note deposits in transit. Deposits in your cash account that aren’t listed in the bank statement are called deposits in transit. Post the total dollar amount as an addition to the bank column. In Table 4-1, deposits in transit total $300. 4. Post outstanding checks. Checks that aren’t posted to the bank statement are considered outstanding checks. Post the total dollar amount as a subtraction from the bank column. In Table 4-1, outstanding checks total $600. 5. Review the bank activity that isn’t posted to the cash account. Some transactions in your bank statement may not be posted to the cash account. In Table 4-1, $20 in bank interest is added to the cash b ­ alance — because the interest isn’t yet posted to the cash account. If you have bank fees, you subtract those fees from the cash account column. 6. Compare the bank and cash balances. If you have properly reconciled, the bank balance should agree with the cash balance. In the table, both ending balances are $720. Your cash account is reconciled with the bank statement. If the balances don’t agree, you have more reconciling items to investigate. Table 4-1 shows a common format for reconciling a bank account. Table 4-1 includes three reconciling items (entries accounted for on the ­statement but not on the books or vice versa): outstanding checks, deposits in transit, and bank interest. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries Table 4-1 Bank Reconciliation Bank Statement Cash Account Starting balance $1,020 $700 Deposits in transit (not shown on statement) 300 Outstanding checks (not shown on statement) (600) Interest (on statement but not posted to books) Adjusted balance 159 20 720 720 Tracking down reconciling items Often, your book balance and the bank statement balance don’t agree. That’s okay, because reconciling items are common. You just need to adjust for uncleared transactions. Here’s a more complete list of ­reconciling items: ✓ If the adjusted bank balance is higher than your balance, check to be sure that all the deposits listed by the bank appear in the cash account in your books. If you find that the bank lists a deposit that you don’t have, do some detective work to figure out what that deposit was for and add the detail to your accounting records. Also, make sure you’ve recorded all outstanding debits and added those amounts (as negative values) to the ending balance on the bank statement. ✓ If the bank balance is lower than your balance, check that all checks listed by the bank are recorded in your cash account. You may have missed one or two checks that were written but not properly recorded. You also may have missed a deposit that you have listed in your cash account but that the bank hasn’t listed on the statement yet. If you notice a missing deposit on the bank statement, be sure you have your proof of deposit and confirm with the bank that the cash is in the account. ✓ If all deposits and checks are correct but you still see a difference, your only option is to make sure all checks and deposits were entered correctly (and not entered twice by mistake or for a different dollar amount) and check your calculations. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 160 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Using a computerized system If you use a computerized accounting system, reconciliation should be much easier than if you keep your books manually. In QuickBooks, for example, when you start the reconciliation process, a screen pops up in which you can enter the ending bank statement balance and any bank fees or interest earned. Figure 4-1 shows you that screen. Figure 4-1: Displaying the reconciliation process in QuickBooks. Intuit.com After you click Continue, you get a screen that lists all checks written since the last reconciliation as well as all deposits. You put a check mark next to the checks and deposits that have cleared on the bank statement, as shown in Figure 4-2, and then click Reconcile Now. QuickBooks automatically reconciles the accounts and provides reports that indicate any differences. It also provides a reconciliation summary, shown in Figure 4-3, that includes the beginning balance, the balance after all cleared transactions have been recorded, and a list of all uncleared transactions. QuickBooks also calculates what your check register should show when the uncleared transactions are added to the cleared transactions. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries Figure 4-2: To reconcile checking by using QuickBooks, you put a check mark next to all the checks and deposits that have cleared the account and click Reconcile Now. 161 Intuit.com Book III Figure 4-3: After reconciling your accounts, QuickBooks automatically provides a reconciliation summary. Adjusting and Closing Entries Intuit.com Posting Adjustments and Corrections After you close out the cash receipts and cash disbursements journals and reconcile the bank account with your accounting system, you need to post any adjustments or corrections that you uncover to accounts that may be impacted by the change. For example, Table 4-1 lists a reconciling item of $20 for bank interest. That interest isn’t yet posted to your books. To post the item, debit (increase) cash $20 and credit (increase) other income $20. 162 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries If you find that several customer payments haven’t been entered in the cash receipts journal, you need to post those payments to the cash receipts ­journal, the accounts receivable journal, and the customers’ accounts. The same is true if you find payments on outstanding bills that haven’t been entered into the books. In such cases, post the payments to the cash ­disbursements journal and the accounts payable journal as well as to the individual vendors’ accounts. Prepping to Close: Checking for Accuracy and Tallying Things Up Closing the books is the process of finishing up all your accounting activity for the period (month or year). Said another way, closing the books ensures that your accounting records are ready to start the next accounting period. As you prepare to close the books, you first need to total what’s in your ­journals, which is called summarizing the journals. During the process, it’s a good idea to look for errors and be sure that the entries accurately reflect the business transactions during the accounting period. Even the smallest error in a journal can cause a lot of frustration when you try to run a trial balance and close out your books, so it’s best to do a thorough search for errors as you close out each journal for the month. Finding an error at this point in the closing process is much easier than trying to track it back through all your various accounts. Paying attention to initial transaction details Do a quick check to be sure the transaction details in your journals are ­accurate. The prior section explains how to do this type of check with the cash journals. When you follow the rules of accrual accounting, however, not all transactions involve cash. In accrual accounting, noncash transactions can include customer purchases made on store credit (which you track in the accounts receivable journal) and bills you will pay in the future (which you track in the accounts payable journal). You may also create other journals to track transactions in your most active accounts, and you probably also keep details about sales in the sales journal and payroll in the payroll journal. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 163 In the payroll journal, make sure that all payroll for the month has been added with all the proper details about salaries, wages, and taxes. Also verify that you’ve recorded all employer taxes that need to be paid. These taxes include the employer’s portion of Medicare and Social Security as well as unemployment taxes. (For more about payroll and payroll taxes, see Book II, Chapters 4 and 5.) Summarizing journal entries When you close your books at the end of the month, you summarize all the journals — that is, you total the columns and post the totals to the general ledger. Journals are temporary holding accounts for transactions. Eventually, all accounting activity must be posted to the general ledger. The general ledger, after all, is used to create financial statements. Summarizing a journal is a four-step process: 1. Number each journal page at the top if it isn’t already numbered. 2. Total any column that’s not titled general debit or general credit. Any transactions recorded in the general debit or general credit columns need to be recorded individually in the general ledger. 3. Post the totals to the general ledger account. Each transaction in the general credit or general debit column must be posted separately. Enter the date and journal page number as well as the amount of the debit or credit, so you can quickly find the entry for the original transaction if you need more details. Keep in mind that total debits in the general ledger should equal total credits. 4. In the post reference (PR) column of the journal, record ­information about where the entry is posted. If the entry to be posted to the accounts is summarized and totaled at the bottom of the page, you can just put a check mark next to the entry in the PR column. For transactions listed in the general credit or general debit columns, you should indicate an account number for the account into which the transaction is posted. This process helps you confirm that you’ve posted all entries in the general ledger. Figure 4-4 shows a summarized journal page, specifically the cash receipts journal. You can see that entries listed in the sales credit and cash debit columns on the cash receipts journal are just checked. Only one entry was placed in the general credit column, and that entry has an account number in the PR column. Although Figure 4-4 doesn’t list all the transactions for the month, which would of course be a much longer list, it does show how you summarize the journal at the end of the month. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 164 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Figure 4-4: Summary of cash receipts journal entries after the first five days. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. As you can see in Figure 4-4, after summarizing the cash receipts journal, there are only four general ledger accounts (general credit, accounts receivable credit, sales credit, and cash debit) and three customer accounts (S. Smith, J. Jones, and P. Perry) into which you need to post entries. Even better, the entries balance: $2,900 in debits and $2,900 in credits! To verify the credit total, add the totals at the bottom of each credit column. The customer accounts total $500, which is good news because it’s the same amount credited to accounts receivable. The accounts receivable account is decreased (credited) by $500 because payments were received, as is the amount due from the individual customer accounts. Summarizing the accounts receivable journal gives you a grand total of all transactions for that period that involved customer credit accounts. Figure 4-5 shows a summary of an accounts receivable journal. The accounts receivable journal includes transactions from the sales journal (where c ­ ustomer purchases on store credit first appear) and the cash receipts journal (where customers’ payments toward their store credit accounts first appear) as well as any credit memos for customer returns. The example in Figure 4-5 is only a few lines long, but, in most companies, the accounts receivable journal is very active with transactions posted every day the business is open during the month. When you summarize the accounts receivable journal, you get a closing balance that shows the total of all financial activity recorded in that journal. Figure 4-5 shows a closing balance of $2,240, which is the amount outstanding from customers. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 165 Figure 4-5: A sample accounts receivable journal summary. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Each transaction in the journal should have a reference number next to it, which tells you where the detail for that transaction first appears in the books. Each line item in Figure 4-5 has a journal page reference. When you check for errors in the journal, you may need to review the original source information used to enter some transactions in order to double-check that entry’s accuracy. In Chapter 3, you go over how to prove out cash, which includes a review for errors. In addition to the accounts receivable journal, you also have individual journal pages for each customer; these pages detail each customer’s purchases on store credit and any payments made toward those purchases. At the end of an accounting period, accountants prepare an aging summary detailing all outstanding customer accounts. This report shows you what money is due from customers and how long it has been due. (See Book II, Chapter 3 for more about managing customer accounts.) For the purpose of proving out the books, the aging report is a quick summary that ensures that the customer accounts information matches what’s in the accounts receivable journal. Table 4-2 shows what an aging summary would look like as of March 31, 2015. Table 4-2 Aging Summary: Accounts Receivable as of March 31, 2015 Customer Current 31–60 Days 61–90 Days S. Smith $300 J. Doe H. Harris 100 $300 $200 500 240 M. Man 400 200 Total 1,300 740 200 >90 Days Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 166 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries In this sample accounts receivable aging summary, the total amount ­outstanding from customers matches the balance total in the accounts receivable journal ($2,240) in Figure 4-5. To compute the total, add the total receivable amount in each column above ($1,300 + $740 + $200 = $2,240). Therefore, all customer accounts have been accurately entered in the books, and the bookkeeper shouldn’t encounter any errors related to customer accounts when running a trial balance, as explained in Chapter 5. If you find a difference between the information in your journal and your aging summary, review your customer account transactions to find the problem. An error may be the result of: ✓ Recording a customer purchase in the accounts receivable journal without recording the details of that transaction in the customer’s account. ✓ Recording a customer purchase directly into the customer’s account without adding the purchase amount to the accounts receivable journal. ✓ Recording a customer’s payment in the customer’s account without recording the cash receipt in the accounts receivable journal. ✓ Recording a customer’s payment in the accounts receivable journal without recording the cash receipt in the customer’s account record. The process of summarizing and closing out the accounts payable journal is similar to that of the accounts receivable journal. For accounts payable, you can prepare an aging summary for your outstanding bills as well. That summary should look something like Table 4-3. Table 4-3 Aging Summary: Accounts Payable as of March 31, 2015 Vendor Current American Bank $150 Carol’s Realty 800 31–60 Days Helen’s Paper Goods $250 Henry’s Bakery Supplies 500 Plates Unlimited 400 200 Total 1,350 950 61–90 Days >90 Days Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 167 The total of outstanding bills on the accounts payable aging summary should match the total shown on the accounts payable journal summary for the accounting period. If yours match, you’re ready for a trial balance. If they don’t, you must figure out the reason for the difference before closing out the accounts payable journal. Keep in mind that the vendor is the company that sold you the product or service on credit. The problem may be the result of: ✓ Recording a bill due in the accounts payable journal without recording it in the vendor’s account. ✓ Recording a bill due in the vendor’s account without recording it in the accounts payable journal. ✓ Making a payment to the vendor in the vendor’s account without ­recording it in the accounts payable journal. ✓ Making a payment to the vendor and recording it in the accounts ­payable journal but neglecting to record it in the vendor’s account. Correct any problems you find before closing out the journal. If you know that you may be working with incorrect data, you don’t want to try to do a trial ­balance. A trial balance with errors can’t be used to generate accurate ­financial reports. Generating a trial balance without checking for errors is wasted effort. Book III Analyzing summary results You may be wondering how you can find problems in your records by just reviewing a page in a journal. Well, that skill comes with experience and practice. As you summarize your journals each month, you’ll become familiar with the expected level of transactions and the types of transaction that occur month after month. If you don’t see a transaction that you expect to find, take the time to research the transaction to find out why it’s missing. Perhaps the transaction didn’t occur or someone forgot to record it. For example, suppose that when summarizing the payroll journal, you notice that the payroll for the 15th of the month seems lower than normal. As you check your details for that payroll, you find that the amount paid to hourly employees was recorded, but someone didn’t record the amount paid to ­salaried employees. For that particular payroll, the payroll company ­experienced a computer problem after running some checks and as a result sent the final report on two separate pages. The person who recorded the payroll numbers didn’t realize there was a separate page for salaried ­employees, so the final numbers entered into the books didn’t reflect the full amount paid to employees. Adjusting and Closing Entries 168 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries As you close the books each month, you’ll get an idea of the numbers you can expect for each type of journal. After a while, you’ll be able to pick out ­problems just by scanning a page — no detailed research required! Planning for cash flow The process you go through each month as you prepare to close your books helps you plan for future cash flow. Reviewing the accounts receivable and accounts payable aging summaries tells you what additional cash you can expect from customers during the next few months and how much cash you’ll need in order to pay bills for the next few months. If you notice that your accounts payable aging summary indicates that more and more bills are slipping into past-due status, you may need to find another source for cash, such as a credit line from the bank. For example, the accounts payable aging summary reveals that three key vendors — Helen’s Paper Goods, Henry’s Bakery Supplies, and Plates Unlimited — haven’t been paid on time. Late payments can hurt your business’s working relationship with vendors; they may refuse to deliver goods unless cash is paid upfront. And if you can’t get the raw materials you need, you may have trouble filling customer orders on time. The lesson here is to act quickly and find a way to improve cash flow before your vendors cut you off. (For more on accounts payable management, check out Book II, Chapter 2.) You may also find that your accounts receivable aging summary reveals that certain previously good customers are gradually becoming slow or nonpaying customers. For example, J. Doe’s account is past due, and at least some portion of his account is overdue by more than 60 days. The bookkeeper dealing with these accounts may need to consider putting a hold on that account until payment is received in full. (For more on accounts receivable management, check out Book II, Chapter 3.) Posting to the General Ledger An important part of closing your books is posting to the general ledger any corrections or adjustments you find as you close the journals. This type of posting consists of a simple entry that summarizes any changes you found. For example, suppose you discover that a customer purchase was recorded directly in the customer’s account record but not in the accounts receivable journal. You have to research how that transaction was originally recorded. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 169 If the only record was a note in the customer’s account, both the sales account and the accounts receivable account are affected by the mistake — both ­balances are understated. The correcting entry looks like this: Accounts receivable Sales To record sale to J. Doe on 3/15/2015 — corrected 3/31/2015. Debit $100 Credit $100 If you find this type of error, the sales transaction record for that date of sale isn’t accurate, which means that someone bypassed your standard bookkeeping process when recording the sale. You may want to research that part of the issue as well because there may be more than just a recording problem behind this incident. Someone in your company may be allowing customers to take product, purposefully not recording the sale appropriately in your books, and pocketing the money instead. It’s also possible that a salesperson recorded a sale for a customer that never took place. If that’s the case and you bill the customer, he would likely question the bill, and you’d find out about the problem at that point. The process of proving out your journals, or any other part of your b ­ ookkeeping records, is a good opportunity to review your internal controls as well. As you find errors during the process of proving out the books, keep an eye out for exceptions (probably similar errors that appear frequently) that may indicate bigger problems than just bookkeeping mistakes. Repeat errors may call for additional staff training to be sure your bookkeeping rules are being followed to a T. Unfortunately, such errors may be evidence that someone in the company is deliberately recording false ­information. Whatever the explanation, you need to take corrective action. (See Book IX, Chapter 2 for coverage of internal controls.) Checking Out Computerized Journal Records Although you don’t have to close out journal pages if you keep your books by using a computerized accounting system, running a spot-check (at the very least) of what you have in your paper records versus what you have on your computer is a smart move. Simply run a series of reports by using your ­computerized accounting system and then check to be sure that those ­computer records match what you have in your files. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 170 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries For example, in QuickBooks, go to the Report Navigator and click on Vendors & Payables. The first section of the navigator page, shown in Figure 4-6, is called A/P Aging (due and overdue bills). This section offers three possible reports: Summary, which shows how much is due for each vendor; Detail, which gives a list of bills due and overdue; and an Accounts Payable Graph that illustrates your outstanding bills. Figure 4-6: QuickBooks allows you to run a number of reports concerning vendors and payables. Essentially, these reports tell you how much money your company owes to others. Intuit.com Figure 4-7 shows you the kind of detail you get when you select the Detail report. The Detail report is divided into: ✓ Current bills ✓ Bills overdue by 1 to 30 days ✓ Bills overdue by 31 to 60 days ✓ Bills overdue by 61 to 90 days ✓ Bills overdue by more than 90 days Obviously, anything in the last two sections — overdue by more than 60 days — is bad news. You can expect a supplier or vendor whose bills appear in these ­columns to soon cut you off from additional credit until your account is up-to-date. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 171 Figure 4-7: When you run an Accounts Payable Detail report in QuickBooks, you get a listing of all outstanding bills, the dates the bills were received, and the dates they’re due. Intuit.com In addition to locating your bill-paying problem areas, you can also use the information in the Detail report to verify that the paper bills you have waiting to be paid in vendor files match what you have on your computer. You don’t need to check every bill, but doing a spot-check of several bills is good practice. The goal is to verify the accuracy of your records as well as make sure that no one’s entering and paying duplicate or nonexistent bills. When it comes to cash flow out of the business, keep tight controls on who can actually sign checks and how the information that explains those checks is recorded. See Book II, Chapter 2 for more about the importance of s­ eparating duties to protect each aspect of your bookkeeping system from corruption. You can also run reports showing the information recorded in your accounts receivable account. Figure 4-8 shows you a list of possible reports to run from the Customers & Receivables page. In addition to the Summary, Detail, and Accounts Receivable Graph, you can also run a report for Open Invoices, which lists outstanding customer invoices or statements, and Collections, which lists not only overdue customers but also how much they owe and their contact information. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 172 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Figure 4-8: In QuickBooks, you can run a series of reports that summarize customer accounts. Intuit.com Again, running spot-checks on a few customer accounts to be sure your paper records of their accounts match the information in your computerized system is a good idea. There’s always a chance that a customer’s purchase was entered in error in the computer, and you could end up sending the bill to the wrong person. Some companies double-check their accounts receivable bookkeeping for accuracy by sending surveys to customers periodically (usually twice a year) to see whether their accounts are correct. If you choose to do this, include with the customer’s bill a postage-paid card asking whether the account is ­correct and giving the customer room to indicate any account problems before mailing the card back to your company. You can also send a survey by e-mail. In most cases, a customer who has been incorrectly billed will contact you soon after getting that bill — especially if he or she has been billed for more than anticipated. In addition to keeping actual accounts, such as accounts payable or accounts receivable, your computerized accounting system keeps a journal of all your company’s transactions. This journal contains details about all your transactions over a specified time period and the accounts that were impacted by each transaction. Figure 4-9 is a sample computerized journal page. Chapter 4: Reconciling Accounts and Closing Journal Entries 173 Figure 4-9: A computerized accounting system keeps a journal of all transactions, which you can review during the closing process. Intuit.com If you need to be reminded of how you recorded a transaction into your ­ omputerized accounting system, run the journal report by date, isolating all c transactions that took place at a particular time. Running a report by date can be a helpful tool if you’re trying to locate the source of an error in your books; if you find a questionable transaction, you can open the detail of that ­transaction and see how it was entered and where you can find the original source material. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 174 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Chapter 5 Checking Your Accuracy In This Chapter ▶ Checking your math with a trial balance ▶ Finding and correcting errors ▶ Preparing a worksheet ▶ Generating reports from your computerized system A fter you close all your journals and do your best to catch any and all errors (flip to Chapter 4 for instructions on how to do this), the time comes to test your work. If you’ve entered all double-entry transactions into the books correctly, the books balance out, and your trial’s a success! Unfortunately, few bookkeepers get their books to balance on the first try. And in some cases, the books balance, but errors still exist. This chapter explains how you do a trial balance of your books and gives tips on finding any errors that may be lurking. You also find out how to take your first step toward developing financial reports (see Books IV and V) by creating a worksheet. Working with a Trial Balance When you first start entering transactions in a dual-entry accounting system, you may think, “This is a lot of work, and I don’t know how I’m ever going to use all this information.” You enter all your transactions, using debits and credits, without knowing whether they’ll actually produce useful financial information that you can use to gauge how well your business is doing. It’s not until after you close your journals and prepare your first set of financial reports that you truly see the value of double-entry accounting. The first step toward producing useable reports that help you interpret your financial results is doing a trial balance — a worksheet prepared manually or spit out by your computer accounting system that lists all the accounts in your general ledger and each account balance at the end of an accounting period. 176 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries The purpose of the trial balance is to prove that, at least mathematically, your debits and credits are equal. If any errors exist in your calculations or in the way you summarized the journals or posted the summaries to the general ledger, they’re uncovered in the trial balance when total debits and total credits don’t come out equal. Conducting your trial balance If you’ve entered transactions manually, you create a trial balance by listing all the accounts with their ending debit or credit balances. (See Book I, Chapter 2 for more about debits and credits.) After preparing the list, you total both the debit and credit columns. If the totals at the bottom of the two columns are the same, the trial is a success, and your books are in balance. Following are step-by-step instructions for developing a trial balance: 1. Prepare a worksheet with three columns: one for account titles, one for debits, and one for credits. 2. Fill in all the account titles and record their balances in the appropriate debit or credit columns. 3. Total the dollar amounts in the debit column and write the total at the bottom of the column. 4. Total the dollar amounts in the credit column and write the total at the bottom of the column. 5. Compare the debit and credit column totals. Figure 5-1 shows a sample trial balance for a company as of May 31, 2014. Note that the debit column and the credit column both equal $57,850, making this a successful trial balance. A successful trial balance is no guarantee that your books are free of errors; it just means that all your transactions have been entered in balance. The books may still contain errors related to how you entered your transactions, including: ✓ You forgot to put a transaction in a journal or in the general ledger. ✓ You forgot to post a journal entry to the general ledger. ✓ You posted a journal entry twice in either the general ledger or in the journal. ✓ You posted the wrong amount. ✓ You posted a transaction to the wrong account. ✓ Your account doesn’t display a normal balance, as explained in the next section. Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy 177 Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries Figure 5-1: A sample trial balance. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Understanding normal balances for your accounts Every account should consistently display either a debit or credit balance, depending on the type of account. Accountants refer to these balances as normal balances. Asset accounts normally display debit balances. Cash, an asset account, should have a debit balance at any point in time. Expense accounts in the income statement also have a normal debit balance. Liability and equity accounts have normal credit balances. Accounts payable, a liability account, should have a credit balance. Revenue (or sales) in the income statement also has a normal credit balance. 178 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries During your trial balance review, if you notice an account that doesn’t have a normal balance, that could be the sign of an error. You should consider making a journal entry to adjust the account. Every account should have a normal balance, or a balance of zero. Adjusting an account to properly reflect a normal balance Assume that you compile your trial balance and notice that your ending balance in cash is a credit balance of $100. A normal balance for cash, an asset account, is a debit balance. The credit balance in cash is a negative balance. If you have a negative balance in the bank, that means the bank has given you a loan. The negative amount (or overdraft) must be paid back to the bank. As mentioned in the previous section, you need to post a journal entry to adjust the cash balance to zero. In this case, you would debit cash $100 and credit loans payable (a liability account) $100. Your cash balance is now zero, and you have properly set up a loan balance for the amount you owe the bank. If, by chance, the errors listed here slip through the cracks, there’s a good chance that the discrepancy will become evident in the financial reports. Dealing with trial balance errors If your trial balance isn’t correct, you need to work backward in your closing process to find the source of the mathematical error. And remember, bookkeepers and accountants work with pencils instead of pens for this reason — pencils make correcting errors much easier. When you need to find errors after completing a trial balance that fails, follow these four basic steps to identify and fix the problem: 1. Check your math. Keep your fingers crossed and total the debits and credits in your trial balance again to be sure the error isn’t just one of addition. That’s the simplest kind of error to find. Correct the addition mistake and re-total your columns. 2. Compare your balances. Double-check the balances on the trial balance worksheet by comparing them to the totals from your journals and your general ledger. Be sure you didn’t make an error when transferring the account balances to the trial balance. Correcting this type of problem isn’t very difficult or time-consuming. Simply correct the incorrect balances, and total the debits and credits in your trial balance again. Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy 179 3. Check your journal summaries. Double-check the math in all your journal summaries, making sure that all totals are correct and that any totals you posted to the general ledger are correct. Running this kind of a check, of course, is somewhat time-consuming, but it’s still better than rechecking all your transactions. If you do find errors in your journal summaries, correct them, reenter the totals correctly, change the numbers on the trial balance worksheet to match your corrected totals, and retest your trial balance. 4. Check your journal and general ledger entries. Unfortunately, if Steps 1, 2, and 3 fail to fix your problem, all that’s left is to go back and check your actual transaction entries. The process can be time-consuming, but the information in your books isn’t useful until your debits equal your credits. If Step 4 is your last resort, scan through your entries looking specifically for ones that appear questionable. For example, if you see an entry for office supplies that’s much larger or much smaller than usual, check the original source material for that entry to be sure it’s correct. If you carefully proved out the accounts payable and accounts receivable journals as explained in Chapters 3 and 4, you can concentrate your efforts on accounts with separate journals. After you find and correct the error(s), run another trial balance. If total debits and total credits still don’t match up, repeat the steps listed here until your debits and credits equal out. You can always go back and correct the books and do another trial balance before you prepare the financial reports. Don’t close the books for the accounting period until the financial reports are completed and accepted. See Books IV and V for more about preparing financial reports. Testing Your Balance by Using Computerized Accounting Systems If you use a computerized accounting system, it automatically generates your trial balance for you. Because the system enables you to enter only transactions that are in balance, the likelihood that your trial balance won’t be successful is pretty slim. But that doesn’t mean your accounts are guaranteed error-free. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 180 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Remember the saying, “Garbage in, garbage out?” If you make a mistake when you enter transaction data into the system, even if the data’s in balance, the information that comes out will also be in error. Although you don’t have to go through the correction steps covered in the earlier section “Dealing with trial balance errors” to reach a successful trial balance, you still may have errors lurking in your data. Accountants frequently run an automated trial balance report at the end of every period. You’ll get in the habit of reviewing the trial balance, making corrections, and running a new trial balance. In addition to the trial balance, automated systems can generate a report showing the general ledger, transaction detail by account, journal detail, voided transactions, and transactions by date. In QuickBooks, you can assess the Accountant & Taxes page, as shown in Figure 5-2, to find these reports. A business’s accountant is likely to use many of the report options to doublecheck that transactions were entered correctly and that no one is playing with the numbers. In particular, the accountant may use a report option called Audit Trail, which reveals what changes impacted the company’s books during an accounting period and who made those changes. This type of report is available in most automated accounting systems. Figure 5-2: The Accountant & Taxes page of Quick­ Books’s Report Navigator provides the option of creating many useful reports. Intuit.com Although it doesn’t match the trial balance done manually in Figure 5-1, the QuickBooks trial balance shown in Figure 5-3 gives you an idea of what a computerized accounting trial balance looks like. Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy 181 Figure 5-3: A sample trial balance report produced by QuickBooks. Intuit.com Developing a Financial Statement Worksheet After your accounts successfully pass a trial balance test (see “Conducting your trial balance” earlier in this chapter), you can take your first stab at creating financial statements, including a balance sheet and an income statement. The first step in producing these statements is using the information from the trial balance and its corrections to develop a worksheet that includes the initial trial balance, the accounts that would normally appear on a balance sheet, and the accounts that would normally appear on an income statement. You create the worksheet that includes these seven columns: ✓ Column 1: Account list ✓ Columns 2 and 3: Trial balance (one column for debits, one column for credits) ✓ Columns 4 and 5: Balance sheet (one column for debits, one column for credits) ✓ Columns 6 and 7: Income statement (one column for debits, one column for credits) Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 182 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Figure 5-4 shows a sample of a worksheet developed from trial balance numbers. Note that the numbers of the trial balance are transferred to the appropriate financial statement; for example, the cash account, which is an asset account, is shown in the debit column of the balance sheet. (See Books IV and V for more about creating financial statements.) Figure 5-4: This sample worksheet shows the first step in developing a company’s financial statements. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. After you transfer all the accounts to their appropriate balance sheet or income statement columns, you total the worksheet columns. Don’t panic when you see that the totals at the bottom of your columns aren’t equal, because the net income hasn’t been calculated yet. However, the difference between the debits and credits in both the balance sheet and the income statement totals should be the same. That amount should represent the net income that will appear on the income statement. (See Book IV, Chapter 2 for more about the income statement.) Chapter 5: Checking Your Accuracy 183 In Figure 5-4, the $4,500 difference for the balance sheet is shown as a credit, representing an increase in retained earnings. The retained earnings account reflects the profits that have been reinvested into the company’s assets in order to grow the company. You can find more about retained earnings in Book IV, Chapter 5. In some companies, earnings are taken out in the form of dividends paid to stockholders. Dividends are a portion of the earnings divided among stockholders. The board of directors of the corporation establishes that a certain amount per share be paid to stockholders. A company must have earnings (either from the current year or in retained earnings) to pay a dividend. If a company has no earnings at all — either in the current year or accumulated in retained earnings from past years — payments to shareholders are considered to be return of capital. Many other small companies that haven’t incorporated pay earnings to their owners by using a drawing account, which tracks any cash taken out by the owners. Each owner should have his or her own drawing account so that you have a history of how much each owner withdraws from the company’s resources. Replacing Worksheets with Computerized Reports If you use a computerized accounting system, you don’t have to create a worksheet. Instead, the system gives you the option of generating many different types of reports to help you develop your income statement and balance sheet. One of the advantages of your computerized system’s reports is that you can easily look at your numbers in many different ways. To get the report you want, all you do is click on the report title. A typical computerized accounting system can generate a number of different reports within the following categories: ✓ Profit and loss (income statement): Some key reports in this section include • A standard report that shows how much the company made or lost during a specific period of time • A detail report that includes all the year-to-date transactions • A report that compares year-to-date figures with the previous year (provided you kept the accounts by using the computerized system in the previous year) Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 184 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries ✓ Income and expenses: Some key reports in this section include • Income by customer (both a summary and a detailed report) • Expenses by vendor (both a summary and a detailed report) ✓ Balance sheet and net worth: Some key reports in this section include • A standard balance sheet showing a summary of assets, liabilities, and equity • A detail report of assets, liabilities, and equity • A report that compares the assets, liabilities, and equity levels with those of the previous year ✓ Cash flow: Some key reports in this section include • A statement of cash flows for the year • A forecast of cash flows during the next few weeks or months based on money due in accounts receivable and money to be paid out in accounts payable Computerized accounting systems provide you with the tools to manipulate your company’s numbers in whatever way you find useful for analyzing your company’s results. And if a report isn’t quite right for your needs, you can customize it. For example, if you want to see the profit and loss results for a particular week during an accounting period, you can set the dates for only that week and generate the report. You can also produce a report looking at data for just one day, one month, one quarter, or any combination of dates. Most computerized accounting systems, including QuickBooks, enable you to custom design reports that meet your company’s unique financial information needs. Many companies customize reports to collect information by department or division. You’re limited only by your imagination! As you work with your computerized system, you’ll be asked for information not easily found by using standardized reports. The first few times you pull that information together, you may need to do so manually. But as you get used to your computerized accounting system and its report functions, you’ll be able to design customized reports that compile and present information in just the way you need it. Chapter 6 Adjusting the Books In This Chapter ▶ Going over types of accounting adjustments ▶ Making adjustments for noncash transactions ▶ Taking your adjustments for a trial (balance) run D uring an accounting period, your bookkeeping duties focus on your business’s day-to-day transactions. When the time comes to report transactions in financial statements, you must make some adjustments to your books. Your financial reports are supposed to report your company’s financial condition, so your books must reflect any significant change in the value of your assets, even if that change doesn’t involve the exchange of cash. Those changes are adjustments. If you use cash-basis accounting, many adjustments aren’t necessary because you record transactions only when cash changes hands. (See Book I, Chapter 4 to find out more about the two accounting methods: accrual and ­cash-basis.) This chapter reviews the types of adjustments you need to make to the books before preparing financial statements. Adjustments include calculating asset depreciation, dividing prepaid expenses, updating inventory numbers, ­dealing with bad debt, and recognizing salaries and wages not yet paid. Adjusting All the Right Areas Even after testing your books by using the trial balance process explained in Chapter 5, you still need to make some adjustments before you’re able to ­prepare accurate financial reports. 186 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries Adjusting entries can be grouped into four categories: ✓ Converting assets into expenses: This book defines assets as resources you use to make money in your business. As you use assets, those dollars become expenses. Assume that your company owns a truck. When you recognize depreciation on your truck, you make an adjusting entry to reduce the asset’s value and post-depreciation expense. ✓ Converting liabilities into revenue: Unearned revenue is defined as payments you receive from customers before you provide a product or service. Unearned revenue is a liability account. If you don’t deliver the product or service, you have to return the payment. When you pay for a one-year magazine subscription in advance, your payment represents unearned revenue to the magazine publisher. As the publisher delivers magazines to you, it moves some of your payment into earned revenue. That journal entry is an adjustment. ✓ Accruing unpaid expenses: When you owe money for an expense at the end of an accounting period, you make an adjustment to accrue the expense. Suppose you owe payroll to your staff for the last week of December. Your next payroll pay date is January 5. On December 31, you debit payroll expense and credit accrued payroll liability for December payroll. ✓ Accruing uncollected revenue: If you’ve earned revenue, but haven’t yet received the payment in cash, you make an adjustment to accrue revenue. If you’ve earned interest on your bank balance, but haven’t yet received interest from the bank, you make an adjustment. You debit (increase) accounts receivable and credit interest income (revenue) for the interest earned. An adjusting entry always uses a balance sheet account and an income statement account. Keep that in mind when posting adjusting entries. Here are three other specific adjustments you may make to your books: ✓ Prepaid expenses: Prepaid expenses are expenses incurred for benefits to be received in the future. This adjustment matches expenses incurred with the benefits received for a period of time. For example, if you pay an annual insurance premium with a single payment, you should move 1/12th of that payment to insurance expense each month of the year. ✓ Bad debts: Bad debt expense is posted to acknowledge that some customers will never pay. Accountants refer to the process as writing off a receivable account. You debit bad debt expense and credit (reduce) accounts receivable. ✓ Supplies: Many companies perform a count of the supplies they have on hand at the end of the month. They use that count to calculate the dollar amount of supplies used during the month. The adjustment is to debit supply expense and credit an asset account — supplies. Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books 187 Depreciating assets The largest noncash expense for many businesses is depreciation. Depreciation is an accounting chore that’s important for every business because it reflects the use and decline in value of assets. (For more on depreciation and why you do it, check out Chapter 1.) The time to adjust the books for depreciation is when you close the books for an accounting period. Some businesses record depreciation expenses every month to more accurately match monthly expenses with monthly revenues, but many business owners make depreciation adjustments only once a year, when they prepare their annual financial statements. Depreciation doesn’t involve the use of cash. By accumulating depreciation expenses on an asset, you’re reducing the value of the asset as shown on the balance sheet (see Book IV, Chapter 4 for the lowdown on balance sheets). Readers of your financial statements can get a good idea of the usefulness of your assets by reviewing your accumulated depreciation. If a financial statement shows that assets are close to being fully depreciated, readers know that you’ll probably need to spend significant funds on replacing or repairing those assets sometime soon. As readers evaluate the financial health of the company, they take that future obligation into consideration before making a decision to loan money to the company or possibly invest in it. Usually, you calculate depreciation for accounting purposes by using the straight-line depreciation method. This method is used to calculate an amount to be depreciated that will be equal each year based on the anticipated useful life of the asset. For example, suppose your company purchases a car that costs $25,000. You anticipate that car will have a useful lifespan of five years and will be worth $5,000 after five years. Using the straight-line depreciation method, you first subtract $5,000 from the total car cost of $25,000 to find the value of the car during its five-year useful lifespan ($20,000). $20,000 represents the depreciable base. Next, you divide $20,000 by 5 to find your depreciation expense for the car ($4,000 per year). When adjusting the assets at the end of each year in the car’s five-year lifespan, your entry to the books should look like this: Depreciation expense Accumulated depreciation: Vehicles To record depreciation for vehicles. Debit $4,000 Credit $4,000 Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 188 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries This entry increases depreciation expense, which appears on the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2). The entry also increases accumulated depreciation, which is the use of the asset and appears on the balance sheet directly below the vehicles asset line. The vehicle asset line always shows the value of the asset at the time of purchase (cost). So, the fixed asset section of your balance sheet after one year of vehicle depreciation would be: Vehicle Accumulated depreciation: Vehicles $25,000 (Cost) ($5,000) You see several times in this book that you debit asset accounts to increase them. Accumulated depreciation is an exception to that rule — this account is a contra-asset account (an account with a normal balance that is the oppo­­­site of other accounts in the same category, as explained in Book IV, Chapter 3). In the previous journal entry, accumulated depreciation is credited for an increase in depreciation expense. Using a credit for accumulated depreciation allows you to present a reduction in the asset you’re depreciating. So, the $25,000 vehicle has $5,000 in depreciation expense. Each asset in your fixed asset listing has its own accumulated depreciation account. You can speed up depreciation if you believe that the asset will be used more heavily in the early years of ownership. Book III, Chapter 1 discusses alternative depreciation methods in greater detail. If you use a computerized accounting system as opposed to keeping your books manually, you may not need to make this adjustment at the end of an accounting period. If your system is set up with an asset management feature, depreciation is automatically calculated, and you don’t have to do it. Check with the person who set up the asset management feature before ­calculating and recording depreciation expenses. Allocating prepaid expenses Most businesses have to pay certain expenses at the beginning of the year even though they’ll benefit from that expense throughout the year. Insurance is a prime example of this type of expense. Most insurance companies require you to pay the premium annually at the start of the year even though the value of that insurance protects the company throughout the year. For example, suppose your company’s annual car insurance premium is $1,200. You pay that premium in January in order to maintain insurance ­coverage throughout the year. For accounting purposes, you need to match the benefit you receive (insurance coverage) with the expense of that benefit (paying insurance premiums). Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books 189 As a first step, you record the cost as an asset called prepaid expenses, and then you adjust the value of that asset to reflect that it’s being used up. Prepaid expenses are assets, because they represent costs that are already paid for. In other words, you don’t have to pay the cost later — and that’s an asset to you. Your $1,200 annual insurance premium is actually valuable to the company for 12 months, so you calculate the actual expense for insurance by dividing $1,200 by 12, resulting in a monthly expense of $100. At the end of each month, you record the use of that asset by preparing an adjusting entry that looks like this: Insurance expenses Prepaid expenses To record insurance expenses for one month. Debit $100 Credit $100 This entry increases insurance expenses on the income statement and decreases the asset prepaid expenses on the balance sheet. No cash changes hands in this entry because cash was reduced when the insurance bill was paid, and the asset account prepaid expenses was increased in value at the time the cash was paid. Counting inventory Inventory is a balance sheet asset that needs to be adjusted at the end of an accounting period. During the accounting period, your company has several issues related to inventory: ✓ Beginning inventory: When you open your doors at the beginning of a period (month, year), you have a certain amount of inventory on hand, or beginning inventory. ✓ Purchases: During the month, you make purchases. You debit inventory and credit cash or accounts payable. ✓ Sales: When you sell inventory, you debit cash or accounts receivable and credit sales for the sale price. You also debit cost of sales (an expense account) and credit inventory for the cost of inventory. The ­difference between sales and cost of sales is your profit. Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 190 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries At the end of the accounting period, you adjust the inventory value to reflect your ending inventory balance. Here’s the formula to calculate ending ­inventory: Beginning inventory + Purchases – Sales = Ending inventory The steps for making proper adjustments to inventory in your books are as follows: 1. Perform a physical count of ending inventory. In addition to calculating ending inventory by using the previous ­formula, you should consider performing a physical count of inventory to be sure that what’s on the shelves matches what’s in the books. Try to perform the physical count as close as possible to the last day of the accounting period, so the physical inventory on hand will be close to your accounting record balance for the last day of the period. 2. Consider the value of your ending inventory. The value of ending inventory varies depending on the method your company chooses to use for valuing inventory. For more about ­inventory value and how to calculate the value of ending inventory, see Book II, Chapter 2. As mentioned in that chapter, you should apply the same valuation method for your inventory each year. If you choose to change the method, you need a justification. 3. Adjust the ending inventory balance. When you physically count the units of inventory and compute each unit’s value, you add up the total. The total ending inventory value in the physical count may differ from that value in your accounting records. If the two values differ, you need to investigate. Either the accounting records are wrong, or your count had an error. You may need to adjust your inventory records, depending on the results of the count. That’s another adjustment at the end of the period. If you track inventory by using your computerized accounting system, the system makes adjustments to inventory as you record sales and make purchases. At the end of the accounting period, the value of your company’s ending inventory should be adjusted in the books already. Allowing for bad debts No company likes to accept the fact that it will never see the money owed by some of its customers. Unfortunately, that’s what happens to most ­companies that sell items on store credit. When your company determines Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books 191 that a customer who has bought products on store credit will never pay for them, you record the value of that purchase as a bad debt. (For an explanation of store credit, check out Book II, Chapter 3.) To find out more about accounting for bad debt, continue reading the sections that follow. Using an aging report At the end of an accounting period, you should list all outstanding customer accounts in an aging report (see Book II, Chapter 3). This report shows which customers owe you money, how much they owe, and for how long they’ve owed you. After a certain amount of time, you have to admit that some customers simply aren’t going to pay. Each company sets its own determination of how long it waits before tagging an account as a bad debt. For example, your company may decide that when a customer is six months late with a payment, you’re unlikely to ever see the money. After you determine that an account is a bad debt, you should no longer include its value as part of your assets in accounts receivable. Including its value doesn’t paint a realistic picture of your situation for the people reading your financial reports. Because the bad debt is no longer an asset, you reduce the value of your accounts receivable to reflect the loss of that asset. Selecting a bad debt method Book III You can record bad debts (write them off) in a couple of ways: ✓ By customer: Some companies identify the specific customers whose accounts are bad debts and calculate the bad debt expense each accounting period based on specific customer accounts. ✓ By percentage: Other companies look at their bad-debts histories and develop percentages that reflect those experiences. Instead of taking the time to identify each specific account that qualifies as a bad debt, these companies record bad debt expenses as a percentage of their accounts receivable. However you decide to record bad debts, you need to prepare an adjusting entry at the end of each accounting period to record bad debt expenses. Here’s an adjusting entry to record bad debt expenses of $1,000: Bad debt expense Accounts receivable To write off uncollectible customer accounts. Debit $1,000 Credit $1,000 Adjusting and Closing Entries 192 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries You can’t have bad debt expenses if you don’t sell to your customers on store credit. You need to deal with bad debt only if you offer your customers the convenience of buying your products on store credit. If you use a computerized accounting system, check the system’s instructions for how to write off bad debt. The following steps walk you through the process of writing off a bad debt and present an example to put all the concepts in context: 1. Initial accounting entries for a sale. Suppose you sell $1,000 in goods to Acme Painting Company. You debit accounts receivable and credit sales for $1,000. Assume your inventory cost was $870. You make a second entry to debit cost of sales and credit (reduce) inventory for $870. Your profit is sales less cost of sales, or ($1,000 – $870 = $130). 2. Review your aging reports. You review an aging report for accounts receivable each month. As time goes on, you notice that the $1,000 Acme Painting receivable becomes older. 3. Attempt collection of the debt. Every company should have a process for following up on past due amounts. In your case, you send Acme letters requesting collection and make phone calls. 4. Determine whether the amount is collectable. Acme Painting goes out of business. Because the company has insufficient assets to pay its bills, you determine that the $1,000 receivable isn’t collectible. 5. Post the bad debt expense entry. Knowing the specific debt isn’t collectible; you debit bad debt expense and credit accounts receivable for the $1,000 Acme owed. Consider the impact on your business. The bad debt means that you’ll collect $1,000 less than you planned. If bad debt amounts are large, they can impact your cash flow planning. Check out Book IV, Chapter 3 for details on planning your cash flow. Growing your sales and dealing with the issue of bad debt Every company wants to grow, which means increasing sales. Selling more usually means selling to new customers. By definition, a new customer has no payment history, so do your homework. Many companies purchase data that documents the creditworthiness of various businesses. The data is similar to what you’d find in a personal credit report. Set financial guidelines for new clients. In addition to checking credit reports, insist that new customers pay on time. Until that client builds a track record of timely payments, you can’t take the risk of the client paying late or not at all. If a new customer doesn’t pay or pays late, consider whether continuing to do business with that customer is a good idea. Chapter 6: Adjusting the Books 193 Suppose your company generates $1,000,000 in sales and has bad debts totaling 2 percent of sales ($20,000). Next year, you’re able to grow sales by $200,000, with bad debt on your new sales of $10,000. A $10,000 bad debt level is 5 percent of your new sales ($10,000 ÷ $200,000). Your bad debt as a percentage of sales for the entire $1,200,000 is $30,000, or 2.5 percent. You sold more, but your bad debt expense (both in total dollars and as a percentage of sales) increased. Increasing sales is good, but if your collections on the new total sales amount decline, you have a problem. A larger bad debt expense can result in lower profit. In the previous example, bad debt expense increased from 2 to 2.5 percent of sales. Profit declined by 0.5 percent for every dollar in sales revenue. Recognizing unpaid salaries and wages Not all pay periods fall at the end of a month. If you pay your employees every two weeks, you may end up closing the books in the middle of a pay period. For example, assume employees aren’t paid for the last week of March until the end of the first week of April. Your fiscal period ends on March 31, which isn’t a payroll pay date. In this case, you need to make an adjusting entry to record the payroll expense incurred but not yet paid, also called accrued payroll. You estimate the amount of the adjustment based on what you pay every two weeks. Here’s how you can accrue for payroll: 1. Calculate your daily payroll expense. Take your total payroll for the period (both before and after the end of the period) and divide that amount by the number of days in the pay period. Typically a pay period is two weeks. Assume your two-week payroll is $2,800. Your daily payroll accrual is ($2,800 ÷ 14 days = $200 per day). 2. Compute payroll accrual. Compute the number of days to be accrued. In this case, assume you need to accrue 7 days — the last week of March. Your payroll accrual is (7 days × $200 per day = $1,400). 3. Post your accrual entry. Here’s the entry you post on March 31 to accrue unpaid March payroll: Payroll expenses Accrued payroll expenses To record payroll expenses for the last week of March. Debit $1,400 Credit $1,400 Book III Adjusting and Closing Entries 194 Book III: Adjusting and Closing Entries After the cash is actually paid out, you reverse the accrual entry. You debit to reduce the liability account (accrued payroll expenses) and credit cash account, to account for the payment. Doing these extra entries may seem like a lot of extra work, but if you didn’t match the payroll expenses for March with the revenues for March, your income statements wouldn’t reflect the actual state of your affairs. Without the payroll accrual, your March payroll would be understated. Testing an Adjusted Trial Balance In Chapter 5, you find out why and how you run a trial balance on the accounts in your general ledger. Adjustments to your books call for another trial balance, the adjusted trial balance, to ensure that your adjustments are correct and ready to be posted to the general ledger. You track all the adjusting entries on a worksheet similar to the one shown in Chapter 5. You need to use this worksheet only if you’re doing your books manually. It’s not necessary if you’re using a computerized accounting system. The key difference in the worksheet for the adjusted trial balance is that additional columns must be added to the worksheet. Columns include ✓ Column 1: Account titles. ✓ Columns 2 and 3: Unadjusted trial balance — the trial balance before the adjustments are made — with Column 2 for debits and Column 3 for credits. ✓ Columns 4 and 5: Adjustments. All adjustments to the trial balance are listed in Column 4 for debits and Column 5 for credits. ✓ Columns 6 and 7: Adjusted trial balance. A new trial balance is calculated that includes all the adjustments. Be sure that the credits equal the debits when you total that new trial balance. If they don’t, find any errors before posting entries to the balance sheet and income statement columns. ✓ Other columns: Use data from the adjusted trial balance columns and create columns for a balance sheet and an income statement. When you’re confident that all the accounts are in balance, post your adjustments to the general ledger so that all the balances in the general ledger include the adjusting entries. With the adjustments, the general ledger can be used to generate financial statements. After you finalize your general ledger for the year, you may want to make changes to your chart of accounts, which lists all the accounts in your accounting system. You may add or subtract accounts, depending on the activity in your business. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets You can use income statements and balance sheets to prove your business’s creditworthiness to prospective lenders. Find out how by visiting www.dummies.com/ extras/accountingaio. In this book… ✓ Understand accounting standards that govern financial reporting for businesses and nonprofit organizations. To ensure accuracy and transparency, you need to know and comply with these standards. ✓ Prepare an income statement to disclose a company’s bottom line — its net profit or loss. Business owners, executives, and managers, along with investors, often head first to the bottom line to assess an organization’s financial condition. ✓ Report the value of a company’s current assets on the balance sheet. Assets are everything the business uses to generate a profit. See how a business converts current assets into cash and puts it to use within the course of a year. ✓ Disclose debt in the balance sheet’s liabilities section and distinguish short-term from long-term debt. (Hint: Short-term debt must be repaid in less than a year. Long-term debt is repaid over the course of a year or longer.) ✓ Calculate the dollar amount of equity in a company and report it in the equity section of the balance sheet. Discover a business’s equity — what it would be worth if it were to sell all its assets and pay back all its debt. ✓ Use the income statement and balance sheet in tandem to draw conclusions about a company’s financial condition. Viewing these sheets side-by-side reveals more than you may imagine. Chapter 1 Brushing Up on Accounting Standards In This Chapter ▶ Looking back at the origins of financial accounting standards ▶ Introducing the accountant’s code of conduct (set by the AICPA) ▶ Reviewing rules set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) ▶ Finding out about generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) A lthough accountants often ply their trade as freelancers, accounting isn’t a free-for-all. Accountants are expected to operate according to a professional code of conduct and practice generally accepted accounting ­principles (GAAP) — best practices for accounting in the United States. This chapter begins with a whirlwind tour through the history of a ­ ccounting that highlights the origins of accounting standards. Following this brief historical account is an overview of the financial accounting code of ­professional conduct, which is set by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). These standards give you a roadmap to follow when you’re trying to figure out how to interact with your clients or employer. The standards also explain how to handle various accounting transactions taking place during day-to-day business operations. Finally, you meet the financial accounting standard-setting bodies. You find out why publicly owned companies (those whose stock shares are traded on a public stock exchange) abide by a different set of standards than privately owned companies. 198 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Exploring the Origins of Accounting Standards Although the history of accounting dates back to prehistoric times, the birth of accounting standards is fairly recent. Here’s a brief timeline that traces the history of accounting up to the present: ✓ Human ancestors probably traded whatever they had or produced to acquire food and other basic necessities. These trades required some equitable method of measuring the relative value of goods, thus ­originating the concept of keeping track of — or accounting for — items. ✓ Later in history, formal accounting records were kept to make sure people paid the required amount of taxes. ✓ The Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries ushered in the mass production of manufactured goods. Mass production required a more sophisticated approach to recording the movement of goods, ­services, and money. As a result, the accounting field had to operate with a higher level of professionalism and expertise. Many owners needed more people to properly manage the business. Mass production resulted in the separation of ownership from management. ✓ Accountants plied their trade in a mostly unmonitored and unregulated environment until the stock market crash of 1929. After this horrific event, the American Institute of Accountants, which is now the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, partnered with the New York Stock Exchange to agree upon five principles of accounting. ✓ Fast-forwarding to the present, these five principles have expanded into hundreds of principles covering every accounting topic imaginable, from how to prepare financial statements to how to keep the books for ­different types of businesses. If you’re just getting started in accounting, you may be wondering why you have to record financial events in such a nit-picky fashion. You may also wonder who the head nit-pickers are and from whence they get their ­authority. Well, read on! This chapter answers both questions and gives you a good foundation for understanding why accountants perform certain tasks the way they do. Sometimes, accountants handle transactions in a certain way simply because that’s the way it’s done. Instead of trying to understand the logic or lack thereof, develop a general understanding of the regulatory system, as explained in this chapter and then go with the flow. As you spend more time working in accounting, the standards will make more sense to you. Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards 199 Recognizing the Role of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) is the national professional organization for all certified public accountants (CPAs). Through its senior technical committee, called the Auditing Standards Board (ASB), the AICPA is responsible for establishing auditing and attestation standards for companies in the United States. To understand what that entails, you need to know the meaning of three key terms: ✓ Auditing: The purpose of auditing is to gather evidence about a company’s financial statements and to use that evidence to determine whether the statements are free of material (significant) misstatements. The company creates the financial statements — the auditor is an independent entity who issues an opinion on the company’s financials. ✓ Attestation: Accountants create other reports on financial statements that don’t provide an opinion. Those reports are considered attestation services. For example, a company may hire you to calculate the rate of return on the company’s investments (see Book VIII, Chapter 3), making sure your figures match the company’s report on the same topic. ✓ Nonpublic: Nonpublic companies are privately owned. Their stock isn’t traded on any open-to-the-public stock exchange. For example, if you start a corporation, you aren’t required to sell any of your shares of stock unless you want to. Tying together regulators for audits of publicly traded companies Shares of publicly traded companies are available for purchase on stock exchanges, such as the New York Stock Exchange, or over-the-counter markets, such as the NASDAQ. To issue securities to the public, companies must register their securities with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) oversees audits of publicly traded companies. The SEC has oversight over the PCAOB. The SEC approves the PCAOB’s rules and standards and its budget. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 200 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The AICPA also enforces a code of professional conduct for its members, which governs how accountants perform their duties. Those duties include performing audits and attestation services. The Auditing Standards Board (ASB) sets audit and attestation standards. This organization is a senior ­committee within the AICPA. When the company involved is publicly traded, the PCAOB and the SEC have oversight. As a result, auditing standards created by the ASB are adopted by the PCAOB and approved by the SEC. If you look through the standards listed on the PCAOB website, you’ll see a list of auditing standards from the ASB. Establishing and adhering to accounting standards ensures that financial reports have accurate information so investors and others can make wellinformed decisions. As an accountant, you’re responsible for serving at least two masters: the organization that hires you to produce the financial reports and investors who use that information to make investment decisions. Accounting standards help to ensure that everyone is making decisions by using timely and accurate financial information. You don’t have to be a CPA or a member of the AICPA to perform your job ethically, or to get work as an accountant. However, membership in the AICPA has many benefits, including automatic accounting standards updates, research tools, and educational resources. ASB audit and attestation standards The ASB is a senior technical committee of the AICPA. The ASB issues the standards and procedures that accountants must follow when conducting attestation and audit services for nonpublic companies. As explained in the prior section, the ASB is also involved with accounting work on publicly traded companies. The ASB also sets quality control standards to use when conducting peer reviews, which occur when one CPA firm evaluates the operations of another CPA firm. Most ASB members work for public accounting firms (such as KPMG LLP), are university professors or governmental accountants, or practice in some other accounting field. Curious about these mysterious ASB standards? They’re called Statements on Auditing Standards (SAS). Here are just a couple of the standards, so you have some idea of what they cover: ✓ SAS No. 1 Section 410 establishes that the auditor must state whether the financial statements are presented in accordance with GAAP. ✓ SAS No. 85 defines the responsibilities that management of a company has for the preparation of the financial statements. Management also must provide written representations about financial statement preparation to the auditors. Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards 201 More information about the ASB standards and procedures is available free of charge on the AICPA website at www.aicpa.org. From the home page, select Research and then Standards. You can access all sorts of good financial ­accounting info on the topics of audit, attest, compilation, and review standards. A compilation occurs when an accountant prepares financial statements for a company by using only data received from company management. A review occurs when the accountant gives limited assurance that no material modifications need to be made to financial statements prepared by company management. AICPA Code of Professional Conduct The AICPA’s Code of Professional Conduct contains six principles of professional conduct by which its members must abide: responsibilities, serving the public interest, integrity, objectivity and independence, taking due care, and the scope and nature of services. Following are brief definitions of the six principles: ✓ Responsibilities: As an accountant, you hold yourself to high moral and ethical standards in order to maintain the public’s confidence in your financial reporting. For example, accountants have the responsibility to participate in self-governance by performing peer reviews of other CPA/ financial accounting firms’ work to check for accuracy and consistency among the profession. ✓ Serving the public interest: An accountant’s public interest is the company for whom she is preparing the financial statements, as well as the users of the financial statements (such as people thinking about purchasing shares of the company stock). The public interest also includes banks and other businesses that are considering granting credit to the company, governmental agencies such as the Internal Revenue Service (which measures the company’s compliance with the tax code), current and prospective investors, and other members of the business and financial community who rely on the objectivity and integrity of CPAs. ✓ Integrity: Having this characteristic means you’re honest when dealing with others. In the world of accounting, integrity means that you serve the company for whom you’re preparing the financial statements to the best of your ability. Keep in mind that this may not be the same as completely agreeing with the way the company wants its financial statements prepared. You can’t be worried that business management is going to be mad at you or fire you if you disagree with them. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 202 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Objectivity and independence: When you’re objective, you’re neutral and unbiased in all decision-making processes. You base your opinions only on facts and not on any preconceived notions you may have. You interpret rules and policies, such as GAAP, in a truthful and sincere manner — staying true to both the form and spirit of the particular ­principle or regulatory issue. Accountants who provide auditing and other attestation services must be independent in both fact and appearance. Being independent means you have no special relationship to or financial interest with the company that would cause you to disregard evidence and facts when evaluating the company. For example, preparing the financial statements for a business owned by a close relative can justifiably cause those reading your report to doubt your objectivity. ✓ Taking due care: In a nutshell, this principle means you have the education and experience to perform the work at hand. You must be both competent and diligent. In addition, due care means you plan and supervise adequately any professional activity for which you’re responsible. ✓ Scope and nature of services: All the principles in this list lead up to this final one. Accountants consider all the preceding principles when determining whether they can provide specific services in individual ­circumstances. For more about these six principles, visit www.aicpa.org/About/code/ sec50.htm. If being a member of the AICPA isn’t mandatory in order to get a job as an accountant, you may wonder why its code of conduct is such a big deal. Well, if you want to be an accountant practicing as a CPA, you must be licensed by your state, which recognizes the authority of the AICPA. State and federal courts consistently hold that all practicing CPAs, regardless of membership in the AICPA, must follow the professional ethical standards contained in the AICPA’s Code of Professional Conduct. Checking Out the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) In addition to the AICPA, other organizations give accountants official guidance on how to prepare financial statements. Public and nonpublic corporations have different agencies that monitor their activities. Perhaps the best known of the regulating agencies is the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The earlier section “Tying together regulators for audits of publicly traded companies” tells you that the SEC has oversight over auditors of public companies. Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards 203 In response to the stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression, Congress passed the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which led to the formation of the SEC. The SEC’s mission is to make sure publicly traded companies tell the truth about their businesses and treat investors in a fair fashion by putting the needs of the investor before the needs of the company. The SEC is run by five commissioners who are appointed to five-year terms by the President of the United States. Their terms are staggered, and no more than three commissioners can be from the same political party at the same time. These commissioners ride herd over the SEC’s power to license and regulate stock exchanges, the companies whose securities are traded on the exchanges, and the brokers and dealers who conduct the trading and sell securities to investors. The enforcement authority given by Congress allows the SEC to bring civil enforcement actions against individuals or companies alleged to have ­committed accounting fraud, provided false information, or engaged in insider trading or other violations of the securities law. The SEC also works with criminal law enforcement agencies to prosecute individuals and ­companies alike for offenses that include criminal violations. As an accountant, your exposure to the regulatory authority of the SEC will be limited unless you work for a company whose shares of stock are publicly traded or you work for a CPA firm conducting financial statement audits for publicly traded companies. Getting to Know the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) The Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF ) was established as a nonprofit corporation in June 1972. FAF was created in response to congressional ­criticism of the standard-setting work being done by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). The FAF in turn established the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), which is the private sector body establishing GAAP for all nongovernmental entities. FAF also established the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB). Governmental entities follow GASB procedures. The FASB has five full-time members, who are selected by FAF. All are required to have knowledge of accounting, finance, and business. For more info about the FASB, accounting standards, and FAF, check out the FASB ­website at www.fasb.org. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 204 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets In 1984, the FASB formed the Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF ) to help identify accounting issues in need of standardization. The EITF is composed of accounting professionals who meet regularly to mull over current economic, business, and industrial developments. Understanding generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) defines the acceptable practices in the preparation of financial statements in the United States. Specifically, GAAP tells accountants exactly how financial data must be presented on the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows. For example, GAAP states that assets, liabilities, and equity must be posted on the balance sheet and not on the income statement. GAAP is also pretty darn picky as to how these accounts are arranged on the balance sheet (you find out more about the balance sheet starting in Chapter 3). In addition, GAAP gives specific rules for separating operating revenue (which is related to the business purpose) from non-operating revenue (non-businessrelated revenue, such as profit from selling a company asset), as explained in Chapter 3. Some of this detail is also explained in the footnotes of the financial statements. Check out Book V, Chapter 4 for more on footnotes. Like most rules, the rule that all businesses must follow GAAP has exceptions. Some businesses, including airlines, franchisors, and healthcare entities, can deviate from GAAP. However, these companies are required to justify their deviation from GAAP in their financial statements. Is GAAP the same for public and nonpublic companies? For now, yes. The SEC has the statutory authority to set accounting standards for publicly held companies, but historically it has relied on private sector bodies to set those standards. As explained earlier in this chapter the SEC oversees the PCAOB in regard to audits. However, the auditing standards listed by the PCAOB are nearly all written by the AICPA’s Auditing entity. The AIPCA is the private sector body setting standards — and the SEC relies on those standards. But hold onto your hats! How accountants view GAAP changed with the adoption of FASB Accounting Standards Codification. FASB Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) became the single source of authoritative GAAP in the United States. Before you get in a dither, keep in mind that the ASC doesn’t change GAAP; the FASB didn’t rewrite all the accounting rules. Instead, the ASC organizes GAAP in a more user-friendly fashion and (mercifully) uses a consistent format across the board for all GAAP topics. Chapter 1: Brushing Up on Accounting Standards 205 Looking online for FASB standards The FASB allows free, limited access to the Accounting Standards Codification. To check it out, visit asc.fasb.org. After you complete the login procedure, you can browse the topics to see how to apply GAAP for accounting topics such as revenue, assets, liabilities and equity, and presentation. Each topic allows you to drill down to more detailed information. For example, if you select Equity, you can further select Treasury Stock to find out how to account for treasury stock under GAAP. For better search functions that allow for a fully functional view of the codification, you can upgrade to ASC’s professional version for an annual subscription cost. If you’re still in school, ask your accounting instructor whether your school has academic access. Pick a standard: Domestic or international For many years, the size of a company — and whether it was public or private — wasn’t considered germane for the accounting and financial reporting standards that should be used by a business. The business world in the United States was under the dominion of one set of accounting and financial reporting standards, GAAP, which applied to all businesses. GAAP was considered the gold standard and good for the rest of the world as well. In recent years, the movement toward adopting international standards gained momentum. Companies using U.S. GAAP may also be affected by international financial reporting standards (IFRS). If you do business outside the U.S., ask your accounting firm whether any IFRS rules affect your business. Serious efforts have arisen to simplify accounting and financial reporting for private businesses. The Private Company Council (PCC), established by FAF, is tasked with making recommendations to the FASB for modifying and making exceptions to GAAP to alleviate the burden on private companies in complying with complex GAAP standards. A movement is underway within the AICPA to allow small- and medium-sized owner-managed entities to deviate even further from GAAP under a frame of reference called Other Comprehensive Basis of Accounting. Where this movement is heading is anyone’s guess, but change seems inevitable. Stay tuned. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 206 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Chapter 2 Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit In This Chapter ▶ Getting a grip on what profit is and isn’t ▶ Designing the income statement and deciding what to disclose ▶ Recognizing how profit affects a business and its financial condition ▶ Handling unusual gains and losses in the income statement ▶ Correcting misconceptions about profit A n income statement shows in black and white how much money a business earned and spent over any given period along with a bottom-line figure — net profit or loss. As an accountant, you create income statements for your company and other users, including investors. Business owners and managers use income statements to determine the overall financial condition of their business and to make informed decisions. Investors and lenders may also refer to a company’s income statements when deciding whether to buy or sell shares in the company or loan the company money. This chapter begins with the components that make up the income statement. It then moves on to disclosures and income statement presentation and leads you through the process of deciding how much information a financial statement reader needs. This chapter also explains extraordinary gains and losses. Finally, you find out about common misconceptions surrounding the calculation and reporting of profit. Understanding the Nature of Profit Profit doesn’t have just one universal meaning or definition. Generally, you can separate profit into three categories: 208 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Selling an asset for a gain: You profit when you buy something and sell it for a gain. Real estate and investment companies are in the business of buying assets that appreciate in value. ✓ Selling a product: Manufacturers make a product and sell it for a profit. Retailers buy products as inventory and make a profit when the inventory is sold. Both types of companies sell a product for more than their total costs. ✓ Providing a service: Plumbers, carpenters, and electricians provide a service for a fee. If the total fees generated are more than the total costs, the business earns a profit. For more about the various ways a business generates profits and reports those profits, keep reading. Throughout this book, asset is defined as a resource you use to generate profit. Businesses need to raise capital to invest in assets. Chapter 4 explains how companies raise money by using debt. If you’re wondering about selling stock (equity) in your business, check out Chapter 5. Profit is a calculated number equal to the difference between revenue and expenses. Revenue is on one side of the scale, expenses are on the other side, and profit is the measure of how much the revenue side outweighs the expense side. To locate profit, you must trace the effects of revenue and expenses. Suppose a business collects cash for all its sales and pays cash for all its expenses during the year. You need to look to only one place — its cash account — to find the business’s profit. However, a business may make credit sales and not collect cash from all its sales during the year. Furthermore, the typical business doesn’t pay all its expenses during the year and pays some expenses before the start of the year. In short, sales and expenses affect several assets, including cash and liabilities. Choosing the Income Statement Format The bottom-line profit (or loss) in an income statement draws the most attention, but the income statement is really about revenue and expenses. A business can’t make profit without revenue and expenses. An income statement reports three basic items of information, in the following order: ✓ Revenue ✓ Expenses ✓ Profit or loss Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 209 Income statements are reported in two basic formats (although in actual practice, you see many variations of them): ✓ Multi-step format: This format typically presents four measures of profit — gross margin, operating earnings, earnings before income tax, and net income (see Figure 2-1 for an example). One revenue line and four profit lines are presented. One purpose of this format is to disclose gross margin, which is a key determinant in the bottom-line profit performance of businesses that sell products. Gross margin is the revenue less cost of goods sold. Any slippage in gross margin as a percent of sales revenue is viewed with alarm. ✓ Single-step format: In this format, all expenses are added and their total is deducted from revenue (see Figure 2-2 for an example). Unlike the multi-step format, the single-step format presents only one profit line, which is bottom-line net income. Figure 2-1: Example of multi-step income statement format. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Book IV Figure 2-2: Example of single-step income statement format. Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The income statement examples shown in Figures 2-1 and 2-2 are simplified versions compared to actual income statements in external financial reports. 210 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Deciding What to Disclose in the Income Statement After a business decides on the format for reporting its income statement (multi-step or single-step, as explained in the preceding section), the next decision concerns how much information to disclose about its expenses. Considering expense disclosure Accountants work with different requirements for expense disclosure, depending on whether the company is public or private. Public companies are subject to financial disclosure rules issued by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). A publicly owned business has no choice but to abide by these rules. Otherwise, trading in its stock shares could be suspended by the SEC — the kiss of death for a public company. Income statement disclosure standards for nonpublic businesses (that is, those not subject to the SEC’s jurisdiction) are less specific. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) provide broad guidance on how much information should be disclosed about expenses in the income statement. (For more about GAAP and other accounting standards, see Chapter 1.) Generally speaking, businesses that sell products report their cost of goods sold expenses, and almost all businesses report their interest and income tax expenses. However, generalizing about the disclosure of other expenses is much more difficult. Figures 2-1 and 2-2 disclose only one large operating expense category: selling and general expenses. Some businesses disclose only this expense because they’re reluctant to reveal any more detail about their operating expenses. Other businesses report five or ten operating expenses in their income statements. Presenting the right amount of expense information When deciding how much expense disclosure to include in income statements, consider the following three factors: Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 211 ✓ Confidentiality: Many businesses don’t want to reveal the compensation of the officers of the business, for example. They argue that this information is private and personal. ✓ Materiality: Most businesses don’t see any point in reporting expense information that’s relatively insignificant and would only clutter the income statement. ✓ Practicality: Businesses limit the income statement contents to what fits on one page. A business can put additional detail about expenses in the footnotes to its financial statements, but many argue that shareowners and lenders have only so much time to read financial statements and putting too much information in their financial reports is counterproductive. If you’re a major outside shareowner in a business, you may request information about four expenses: repairs and maintenance, advertising, pension and profit-sharing plans, and employee benefit plans. The information could be reported in the income statement itself or in the footnotes to the financial statements. Why these four? Repairs and maintenance expense can be manipulated by management to push profit up or down for the year. Advertising is a discretionary expense that you may want to compare to sales revenue. Pension and profit-sharing plans and employee benefit plans can be large encumbrances on a business. Examining How Sales and Expenses Change Assets and Liabilities In a financial report, the income statement may seem disconnected from the balance sheet and the statement of cash flows. Nothing is further from the truth. The three financial statements are interdependent and interconnected. For example, if sales revenue or one of the expenses had been just $10 different from the amount reported in the income statement, a $10 difference would appear somewhere in the balance sheet and statement of cash flows. The following sections explain how income statement activity is connected to the balance sheet and how the two together reflect the financial condition of a business. Sizing up a business’s financial condition Financial condition is the status of the firm’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a certain point in time. For this book, financial condition refers to the amounts presented in the balance sheet. This section explains how income statement activity is connected to the balance sheet. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 212 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets As explained earlier in this chapter, in the section “Choosing the Income Statement Format,” an income statement reports revenue, expenses, and profit (or loss). But an income statement doesn’t report how revenue and expenses change the financial condition of the business. For example, in Figure 2-1, $26,000,000 revenue is reported in the annual income statement of a business. The business also reports $24,310,000 total expenses for the year (the sum of the four expense line items). How did the sales revenue and expenses change its financial condition? The income statement doesn’t answer that question. The balance sheet does, as explained in Chapters 3 to 5. Business managers rely on their accountants to explain how sales and expenses change the assets and liabilities of their businesses. Business lenders and shareowners also need to understand these effects in order to assess the health of a business. Noting how accounting transactions affect the income statement and balance sheet Typical accounting transactions — accounting entries that many businesses make every month — affect income statement activity that relates to balance sheet accounts. Suppose you’re the chief accountant of the business whose income statement is presented in Figure 2-1. The president asks you to explain the financial effects of revenue and expenses reported in its latest annual income statement at the next meeting of its board of directors. To help organize your thoughts for the presentation, you decide to prepare summary revenue and expense journal entries for the year. Based on your analysis, you prepare the following summary journal entries for revenue and expenses reported in the income statement: Revenue and receivables Account Cash Accounts receivable Sales revenue Debit $25,000,000 $1,000,000 Credit $26,000,000 The business makes credit sales. When recording a credit sale, the asset account accounts receivable is debited (increased). When the customer pays, accounts receivable is credited (a decrease). The business initially collected $25,000,000 in cash payments from customers. The accounts receivable ­balance for the period increased by $1,000,000. Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 213 Cost of goods sold expense and inventory Account Cost of goods sold expense Inventory Cash Accounts payable Debit $14,300,000 $2,000,000 Credit $14,500,000 $1,800,000 The business purchases $16,300,000 of product during the year. Of that total, $14,300,000 represents cost of goods sold. The remaining $2,000,000 in purchases remained in inventory. The company didn’t pay cash for all its $16,300,000 in purchases. Its accounts payable for inventory purchases increased $1,800,000. Therefore, cash outlay for purchases during the year was $14,500,000 ($16,300,000 – $1,800,000). Selling and general expenses and payables Account Selling and general expenses Prepaid expenses Cash Accounts payable Accrued expenses payable Accumulated depreciation Debit $8,700,000 $300,000 Credit $6,900,000 $850,000 $725,000 $525,000 Selling and general expenses is a somewhat complicated entry because operating expenses involve several balance sheet accounts. The business added $300,000 to its prepaid expenses balance during the year. It recorded $525,000 depreciation expense for the year. In this instance, depreciation expense is included in the selling and general expenses debit amount reported in its income statement. That same amount is credited to accumulated depreciation, as shown in the previous table. Not all expenses were paid for by the end of the year; unpaid expenses caused an $850,000 increase in accounts payable and a $725,000 increase in accrued expenses payable. Interest expense and payables Account Interest expense Cash Accrued expenses payable Debit $400,000 Credit $350,000 $50,000 Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 214 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The business paid $350,000 interest during the year. The amount of unpaid interest at year-end increased $50,000. A general liability account for accrued expenses is shown in this entry. (The business may credit a more specific account, such as accrued interest payable.) Income tax expense and payables Account Income tax expense Cash Accrued expenses payable Debit $910,000 Credit $830,000 $80,000 At the end of last year, the business didn’t owe any income tax. During the year, it made $830,000 installment payments toward its estimated income tax. Based on the final determination of its income tax for the year, the business still owes $80,000, which it will pay when it files its tax return. The general liability account for accrued expenses is shown in this entry. (The business may credit a more specific account, such as income tax payable.) Considering the Diverse Financial Effects of Making a Profit Making sales and incurring expenses cause a multitude of effects on the assets and liabilities of a business. In other words, making profit causes many changes in the financial condition of a business. It would be convenient if a $1 profit caused a $1 cash increase and nothing more, but the effects of making profit are much broader and reach throughout the balance sheet. This section introduces a tool, called a T-account, to explain how profit affects the entire balance sheet. Introducing T-accounts The journal entries in the preceding section summarize the effects of sales and expenses on a business’s assets and liabilities. Figure 2-3 shows these changes in T-accounts for the assets and liabilities. T-accounts aren’t the official, formal accounts of a business. Rather, T-accounts are like scratch paper that accountants use to analyze and “think out” the effects of transactions. A T-account has two columns: debits are always put in the left column and credits in the right column. The rules for debits and credits are explained in Book II, Chapter 1. Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 215 Figure 2-3: Changes in assets and liabilities caused by sales and expenses. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Figure 2-3 uses seven asset and liability accounts to illustrate the recording of revenue and expenses for the year. Even a relatively small business may have 100 or more asset and liability accounts in its chart of accounts (see Book I, Chapter 2). However, the seven asset and liability accounts in the example are sufficient to illustrate the effects of revenue and expenses on the financial condition of a business. Combining activity into one journal entry In order to help you understand what profit consists of, the activity in Figure 2-3 is combined into one comprehensive journal entry. In this entry, the $1,690,000 profit for the year is shown as an increase in the retained earnings owners’ equity account. Comprehensive Journal Entry that Summarizes Changes in Assets and Liabilities from Profit-Making Activities during the Year Account Cash Accounts receivable Inventory Prepaid expenses Accounts payable Accrued expenses payable Accumulated depreciation Owners’ equity — retained earnings Debit $2,420,000 $1,000,000 $2,000,000 $300,000 Credit $2,650,000 $855,000 $525,000 $1,690,000 Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 216 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The totals for each balance sheet account represent the totals in the T-accounts in Figure 2-3. Simply add the amounts you see in each T-account. The cash total, however, is a little more complicated. For cash, take the $25,000,000 debit and subtract the sum of the credit entries ($22,580,000) to arrive at the $2,420,000 balance in cash. Profit improves the net worth of a business. Net worth, another name for the owners’ equity, equals total assets minus total liabilities. In this example, the business makes a profit, and the effect on the balance sheet is that assets increase more than liabilities, which is the typical profit effect. To figure out how to calculate retained earnings, head over to Chapter 5. Explaining additional transactions related to profit The profit-making activities of a business include more than just recording revenue and expenses. Additional transactions are needed, which take place before or after revenue and expense are recorded. You see some common transactions in the “Noting how accounting transactions affect the income statement and balance sheet” section, earlier in this chapter. This section offers a more generic explanation of before-and-after transactions. These explanations apply to dozens of accounting entries in your business. ✓ Collecting cash from customers for credit sales made to them. The cash is collected after recording the sales revenue. ✓ Purchasing (or manufacturing) products that are put in inventory and held there until the products are sold sometime later. When a sale occurs, the cost of products sold is charged to expense in order to match costs with the revenue from the sale. ✓ Paying for products bought on credit and for other items that aren’t charged to expense until sometime after the purchase. These purchased items are considered assets until they’re used (expensed). ✓ Paying for expenses that have been recorded sometime earlier. ✓ Making payments to the government for income tax expense that has already been recorded. Only revenue and expenses are reported in the income statement, but the other transactions change assets and liabilities, and they definitely affect cash flow. See Book V, Chapter 2 for more about cash flow. Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 217 Reporting Extraordinary Gains and Losses When accountants refer to extraordinary transactions, they mean activity that’s not related to your day-to-day business. Assume you manufacture blue jeans. You incur costs to buy denim material. You pay labor costs and collect cash from sales. If you happened to sell your headquarters building for a gain, that transaction would be out of the ordinary (extraordinary). After all, you’re in the business of making blue jeans — not selling real estate. Any profit from the sale of the building would be an extraordinary gain. Segregating the income statement Extraordinary gains and losses require an income statement that’s split into two distinct sections. Many businesses report unusual, extraordinary gains and losses in addition to their usual revenue, income, and expenses. Remember that recording a gain increases an asset or decreases a liability. And recording a loss decreases an asset or increases a liability. When a business records an extraordinary gain or loss during the period, its income statement is divided into two sections: ✓ The first section presents the ordinary, continuing sales, income, and expense operations of the business for the year. ✓ The second section presents any unusual, extraordinary, and nonrecurring gains and losses that the business recorded in the year. Considering business disruptions The road to profit is anything but smooth and straight. Every business experiences an occasional discontinuity — a serious disruption that comes out of the blue, doesn’t happen regularly or often, and can dramatically affect its bottom-line profit. In other words, a discontinuity is something that disrupts operations or the regular flow of profit-making activities. Here are some examples of discontinuities: ✓ Downsizing and restructuring the business: Layoffs may require severance pay or trigger early retirement costs; major segments of the business may be disposed of, causing large losses. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 218 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Abandoning product lines: When leadership decides to discontinue selling a line of products, the business loses at least some of the money it paid to obtain or manufacture the products, because it either sells the products below cost or writes off products it can’t sell as a loss. ✓ Settling lawsuits and other legal actions: Paying damages or fines or receiving awards from favorable rulings are nonrecurring extraordinary losses or gains. ✓ Writing down (also called writing off) damaged and impaired assets: If products become damaged and unsellable, or fixed assets need to be replaced unexpectedly, you need to remove these items from the assets accounts. Even when certain assets are in good physical condition, if they lose their ability to generate future sales or other benefits to the business, accounting rules say that the assets have to be taken off the books or at least written down to lower book values (see Book III, Chapter 1). ✓ Changing accounting methods: A business may decide to use a different method for recording revenue and expenses than it did in the past, in some cases because the accounting rules (set by the authoritative accounting governing bodies — see Chapter 1) have changed. Often, the new method requires a business to record a one-time cumulative effect caused by the switch in accounting method. These special items can be huge. ✓ Correcting errors from previous financial reports: If a business discovers that a past financial report had an accounting error, it must make a correction entry, recording a loss or gain that had nothing to do with the performance of the business in the current year. According to financial reporting standards, a business must make these onetime losses and gains very visible in its income statement. So in addition to the main part of the income statement that reports normal profit activities, a business with unusual, extraordinary losses or gains must add a second layer to the income statement to disclose these out-of-the-ordinary happenings. If a business has no unusual gains or losses in the year, its income statement ends with one bottom line, usually called net income, as shown in Figures 2-1 and 2-2. When an income statement includes a second layer, the net income line becomes net income from continuing operations before unusual gains and losses. Below this line, each significant, nonrecurring gain or loss appears. Suppose a business suffered a relatively minor loss from ending a product line and a very large loss from a major lawsuit whose final verdict went against the business. The second layer of the business’s income statement would look something like the following: Net income from continuing operations Discontinued operations, net of income taxes Earnings before effect of legal verdict Loss due to legal verdict, net of income taxes Net earnings (loss) $267,000 ($20,000) $247,000 ($456,000) ($209,000) Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 219 The gains and losses reported in the second layer of an external income statement are generally complex and may be quite difficult to spot. When looking for extraordinary gains or losses, answer the following questions: ✓ Why wasn’t the loss or gain recorded on a more piecemeal and gradual year-by-year basis instead of as a one-time charge? ✓ Was the loss or gain really a surprising and sudden event that couldn’t have been anticipated? ✓ Is such a loss or gain likely to occur again in the future? Questioning whether activity is truly unusual Every company that stays in business for more than a couple of years experiences a discontinuity of one sort or another. But beware of a business that takes advantage of discontinuities in the following ways: ✓ Discontinuities become continuities: A successful business makes consistent profits from continuing operations. It’s the day-to-day business that drives profit. Beware of a business that makes an extraordinary loss or gain a regular feature on its income statement. Suppose that every year or so, the business loses a major lawsuit, abandons product lines, or restructures itself. It reports “nonrecurring” gains or losses on a recurring basis. You should question whether the company’s core business could be profitable without all the unusual transactions. ✓ A discontinuity is used as an opportunity to record all sorts of writedowns and losses: When recording an unusual loss (such as the cost of settling a lawsuit), the business opts to record other losses at the same time and writes off everything but the kitchen sink (and sometimes that, too). According to this big-bath strategy, you may as well take a big bath now in order to avoid taking little showers in the future. Consider whether all the write-offs truly relate to the event that occurred or whether the company is taking advantage of the situation to expense unrelated items. A business may just have bad (or good) luck regarding extraordinary events that its managers couldn’t have predicted. If a business is facing a major, unavoidable expense this year, cleaning out all its expenses in the same year so it can start fresh next year can be a clever, legitimate accounting tactic. But where do you draw the line between these accounting manipulations and fraud? Staying alert to these potential problems is an important first step. The subject of fraud is covered in Book IX, Chapter 7. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 220 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Correcting Common Misconceptions about Profit To wrap up this chapter, consider some misconceptions about profit. It’s critical that an accountant understand these issues. The first section covers misconceptions generally. The second discussion focuses on your firm’s profit compared with profit standards in your industry. Finally, you consider an analysis of credit sales and bad debt. The purpose of this section is to remind business owners to stop and consider what their level of profit really means to the business. Clearing up profit misconceptions Many accountants find themselves clearing up these misconceptions for other people in the organization: ✓ Profit does not increase cash by the same amount. Book III, Chapter 6 explains the difference between cash- and accrual-basis accounting. Most companies use the accrual method, which matches revenue earned with expenses incurred to earn the revenue. Using this method, you may post revenue and record expenses without cash moving in or out of your business. As a result, a $20,000 profit doesn’t mean your cash account is immediately $20,000 higher. ✓ Some revenue and expense entries are based on estimates. Another misconception about profit is that the numbers reported in the income statement are precise. Many journal entries are based on estimates, which require using judgment. Recognizing bad debt expense, for example, often requires an estimate of the percentage of customers who won’t pay. The expense may be adjusted later, when the actual amount of bad debt is known. (For more on bad debt expense, see “Waving the red flag when you see revenue and credit sales increase,” later in this chapter.) Profit calculations are partially based on estimates. ✓ A high level of profit doesn’t mean that the balance sheet is necessarily attractive to investors. Consider how a company acquires and uses assets to generate a profit. Assume a company borrows heavily to meet high customer demand. The plan works, and the firm generates a high level of profit. If sales levels go down, profit may decline. The business will have less in revenue to make the larger debt payments. Ramping up spending to meet high demand may become a drag on profits if sales decline. An investor may shy away from investing in a company with a high debt load and declining sales. Chapter 2: Preparing an Income Statement and Considering Profit 221 Comparing to industry standards When considering your level of profit, comparing your profit to that of other companies in your industry may be useful. Here are some points to mull over. The percentages used are profit margin percentages (net income divided by sales): ✓ Reasonableness: Your shop sells sporting goods to hikers, mountain bike riders, and other outdoor sports participants. You earn what you believe to be an unusually high level of profit of 25 percent for the year. After some research, you find that similar shops had profits in the same range. Turns out that great weather increased demand for outdoor sporting goods. You conclude that the profit — which is higher than you expected — is reasonable, based on the industry average. ✓ Sustainable level of profit: Assume your grocery store has a 10 percent profit for the year. Stores in your industry typically have an annual profit of 2 percent. You do research to determine whether the 10 percent profit is sustainable. After all, your profits should be in line with the industry’s profit levels over time. You find that your high profit level was due to more demand, due to a nearby grocery store closing. You decide to plan future sales and costs based on the industry’s 2 percent profit. ✓ Adding a product line: You manage a roofing company, which installs and repairs roofs for the residential market. You’re considering adding siding installation to your business. To estimate a profit margin for your new venture, you can consider the industry profit averages. Assume that your roofing business generates a 12 percent profit and the siding industry averages a 5 percent profit. You can consider how your total company profit would look, after you add the new product line. Your goal is to plan and manage your business based on a reasonable, sustainable level of profit. Industry standards should be part of your analysis. Waving the red flag when you see revenue and credit sales increase When comparing income statements from different periods for the same business, watch out for this common big red flag: an increase in revenue that’s tied to an increase in credit sales. (See Book V, Chapter 3 for additional guidance on analyzing financial statements.) Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 222 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Credit sales mean that you’re selling a product that will be paid for at a later date. When a business increases its credit sales, it needs to consider how much of those sales are credit sales to new customers. New customers, by definition, don’t have a track record of making timely payments on credit sales. You may find that credit sales are increasing, but that bad debt expense is increasing even faster. A business needs to perform some analysis to determine whether sales to new customers will be profitable over the long term. Here’s an example. You note these results from the prior year: Prior year results: Credit sales $1,200,000, bad debt expense $24,000 (2% of credit sales) The profit on the credit sales includes all expenses — including bad debt expense. In the current year, you note an increase in credit sales. You also see that bad debt expense increased to 3.5 percent of credit sales. Here are the current year results: Current year results: Credit sales $1,500,000, bad debt expense $52,500 (3.5% of credit sales) Bad debt expense increases by $28,500 ($52,500 less $24,000). You can see how this additional expense would eat away at profit. Assuming everything else remained the same, this higher bad debt expense would reduce the profit margin. Every dollar increase in credit sales generates a higher dollar amount of bad debt, compared to the prior year. If you own or run the business, you must consider whether the new customers are worth the risk of bad debt. Book III, Chapter 6 has more information on bad debt expense. Chapter 3 Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section In This Chapter ▶ Sticking with an asset’s historic cost ▶ Listing common current assets ▶ Distinguishing between tangible and intangible assets ▶ Preparing the asset section of a balance sheet A balance sheet reports a company’s assets, liabilities (claims against those assets), and equity (the amount of money left when you sell what you own and pay what you owe). This chapter gets the party started by focusing on assets; Chapter 4 walks you through the liabilities section, and Chapter 5 covers equity. Assets are resources a company owns and uses to generate revenue. Businesses have many different types of assets, which are categorized as either current or noncurrent. Current assets (such as checking accounts, accounts receivable, and inventory) are liquid, which means they either are cash or can quickly be turned into cash. Noncurrent assets aren’t liquid; converting them to cash may take time. Converting these assets to cash may result in a loss or a gain on sale. Examples of noncurrent assets include tangible assets (things you can touch) such as a company’s cars, computers, office buildings, or factories. Not every noncurrent asset is tangible. For example, consider a company’s patents and trademarks, as well as investments that a business makes in other companies — these are all intangible assets. Another intangible asset, goodwill, is created when a business buys another company. Current? Noncurrent? Tangible? Intangible? The topic of assets may seem a little overwhelming at first because so many kinds of assets exist. But this chapter gives you a straightforward, easy-to-understand tutorial on the ABCs of assets. 224 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Homing in on Historic Cost Before exploring typical business assets, you need to understand how the value of most assets normally shows up on the balance sheet. Most assets are valued on the balance sheet at their original historic cost — the cost of the item when it was acquired plus any other costs to prepare the asset for use. Historical cost isn’t fair market value, which is what a buyer is willing to pay for the asset in an open marketplace. Here’s an example: Suppose a company buys a building for $200,000 in 1999. That $200,000 is the building’s historic cost. In 2015, the fair market value of that building is $400,000, but the value of the asset on the balance sheet stays at $200,000 — the historical cost. Book value is defined as cost minus accumulated depreciation. If you consider buying an asset, the “true value” of the asset is its book value. Check out Book III, Chapter 1 for more on book value and depreciation. Record marketable securities — securities that the company purchases to sell in the short term — at their fair market value. See “Short-term investments,” later in this chapter, for details. Keep in mind that some assets, such as marketable securities, use fair market value as the asset’s value on the balance sheet. Discovering What Makes an Asset Current For this book, current assets include cash and any asset that a company anticipates converting to cash within a 12-month period from the date of the balance sheet. On the balance sheet, you should list current assets in order of liquidity. Because cash is the most liquid (it’s already cash), it shows up on the balance sheet first. Other common current assets are short-term investments, accounts receivable, notes receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses. The following sections cover each type in turn. Cash Cash consists of paper bills, coinage, and accounts backed by cash. For example, when you go to the grocery store and use your debit card to pay for your groceries, that debit transaction is the same as paying with cash. That’s because when you swipe your card and enter your PIN, you attest to the fact that funds in your checking account are sufficient and immediately available to cover the cost of your groceries. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 225 Depending on the size of the business, it may organize and manage its revenue and bill paying in one or more types of cash accounts. For example, a retail business probably has a separate operating account and merchant account (an account where credit card transactions deposit). A large service business may have a separate operating account and payroll account. Some companies have cash accounts for which they earn interest income. You may be wondering why a company complicates its bookkeeping with different bank accounts to pay expenses and accept revenue. In some cases, having different bank accounts creates a safer business environment. For example, having a dedicated payroll account allows payroll disbursing employees to do their job (process payroll paper checks and electronic transfers) while having access to a limited, defined amount of cash. But with cash accounts, it’s really the Wild West out there in the business world. Some small businesses have more accounts than they actually need, and some large businesses have only one. In terms of the balance sheet, the most important point to remember about cash accounts is that they’re included in the current section of the balance sheet. However, understanding the business purpose for different types of cash accounts is also important — so here they are, with brief descriptions: ✓ Operating checking account: A business usually earmarks a particular checking account, which it calls its operating account, to handle business activities such as depositing revenue and paying bills. ✓ Payroll checking account: Many companies have a checking account used only to pay employees. The company calculates the total dollar amount of checks or transfers going to pay employees and transfers that amount from its operating account to cover the payroll checks. Often, businesses hire a payroll service to perform these tasks. Head to Book II, Chapters 4 and 5 for more on payroll. ✓ Merchant account: If a business allows customers to pay by credit card, it probably has a dedicated merchant account into which the only deposits are from its merchant provider: the company that helps it process customer credit card transactions. Normally, withdrawals from this account go to the operating cash account to cover bill-paying withdrawals. ✓ Petty cash account: Most companies have a cash box to pay for small daily expenses. This account is also known as an imprest account, which means it always carries the same balance. Anytime the cash box is checked, it should contain cash or receipts equaling the petty cash fund amount. So if the fund balance is $300, cash and receipts in the box must equal $300. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 226 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Sweep account: A sweep account is a way for the company to ­automatically earn investment income. Each evening, any extra cash in the company’s operating account is gathered up and transferred (swept) into investment accounts. Money from many different companies is pooled into a bigger pot, thereby providing the advantage of a higher rate of return. Then as the company needs the money in order to clear checks and withdrawals, the money is swept back into the operating account. A negative (credit) balance in a cash account is considered a loan. If you have a negative balance, your account is overdrawn. That means that you owe the bank money. This situation requires an adjustment at the end of an accounting period. You should debit cash (to adjust the account to zero) and credit a loan or payable account. A credit entry increases a liability account. Short-term investments A business may make short-term investments by purchasing securities issued by other companies to the public. These investments can be equity (stock) and debt (bond) securities that a company uses to invest any idle cash and earn a return. (For more about bonds, see Chapter 4. Stocks are covered in Chapter 5.) Instead of investing idle cash in a bank account, a company invests idle cash in stocks and bonds. To classify these investments as short-term (current assets), the company must be planning to sell them within 12 months of the balance sheet date. Two types of common short-term investments are trading and available-forsale securities, which the following sections describe. Trading securities Trading securities are debt and equity securities that a business purchases to sell in the short term to make a profit. You record trading securities on the balance sheet initially at cost. Then, as their value fluctuates, you record them at fair market value with any unrealized gain or loss going to the income statement. Unrealized means the gain or loss is only on paper. You won’t have realized gain or loss until you actually sell the securities. You must have a buy and a sell to have a realized gain or loss. An unrealized gain or loss on a security means that a gain or loss would occur if you were to sell the security. Until you sell the asset, the gain or loss is unrealized. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 227 For example, suppose your company buys 100 shares of common stock in ABC Corp. for $1,000. To record this transaction, the balance sheet’s trading securities account is increased by $1,000 and cash is decreased by the same amount. Sadly, at the end of the month after purchase, these 100 shares are now worth only $900. To adjust the current asset section of the balance sheet, you need to credit (reduce) trading securities by the $100 drop in value. Then you also debit (increase) other losses on the income statement (see Chapter 2) by $100. As explained previously in the chapter, historic cost isn’t used on the balance sheet when you’re dealing with marketable securities. In this example of ABC Corp. stock dropping in value, the value of ABC Corp. stock on the balance sheet is reflected at less than historic cost. Available-for-sale securities Available-for-sale securities are debit and equity investments that a company opts not to classify as trading securities. The difference is important because unrealized fluctuations in the value of available-for-sale securities do not show up on the income statement as gain or loss. Instead, any changes (net of tax) go onto the balance sheet as accumulated other comprehensive income. Here’s how to handle an available-for-sale transaction: Suppose Reeves Corporation buys 2,000 shares of common stock for $5,000, deciding to classify the stock as available-for-sale. At the end of the month, the fair value of the shares is $6,000. Woohoo! That’s an unrealized gain of $1,000! To record this transaction, you increase (debit) the value of the security on the balance sheet by $1,000 (from $5,000 to $6,000) and increase (credit) accumulated other comprehensive income by $1,000. Accounts receivable Accounts receivable (A/R) is the amount of money that customers owe a business for merchandise or services they purchased from the business on credit. Many companies sell products and services on credit, because the practice encourages customers to do business. As a result, many companies have accounts receivable balances. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 228 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Assume you perform a service and give a client an invoice for $500. A couple weeks later, your client mails you a check for payment in full. In that two-week period between when you performed the service and received the payment, that $500 is on your books as an accounts receivable. Unfortunately, some customers who buy on credit don’t pay their bills. Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP; see Chapter 1), you have to make a valuation adjustment for such uncollectible accounts, called bad debt. If you determine that a customer isn’t going to pay, the receivable balance should be recorded as bad debt expense. If you extend credit to customers, GAAP requires that you estimate your uncollectible accounts. Companies usually base their estimate on their past experiences with bad debt. For example, a company finds that 2 percent of all credit sales over the past 5 years were never collected. Those balances were written off as bad debt expense. That history of bad debt experience (2 percent of sales) can be used to estimate bad debt in the current period. Using the allowance method for bad debt expense The allowance method enables you to estimate the amount of bad debt expense, based on some percentage of credit sales. In the previous example, you estimate that 2 percent of credit sales will be uncollectible. Suppose sales on account are $50,000. Using the 2 percent figure, the estimate for uncollectible accounts is $1,000 ($50,000 × 0.02). The journal entry to record this amount is to debit (increase) bad debt expense $1,000. Bad debt expense is an income statement account. You also credit (increase) allowance for doubtful accounts $1,000. Allowance for doubtful accounts is considered a contra account. A contra account carries a balance opposite to the account’s normal balance. Because the normal balance for an asset is a debit, the normal balance for a contra-asset account, such as allowance for doubtful accounts, is a credit. The amount of money you expect to collect from credit sales is defined as net receivables. Here’s the formula: Net receivables = Accounts receivable – Allowance for doubtful accounts Allowance for doubtful accounts tells the financial statement reader the dollar amount of credit sales you estimate as bad debt. Until the company is reasonably sure that a customer on account won’t cough up the cash, the journal entry is just an estimate not tied to any particular customer. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 229 When you determine that a particular customer’s account is uncollectible (maybe the company declares bankruptcy), your next step is to remove the amount from both allowance for doubtful accounts and the customer accounts receivable balance. After all, the mystery is over — you know the customer won’t be paying. For example, Newbury Supplies owes you $1,000. You send it a past-due notice that the post office returns as undeliverable with no forwarding address. After following up, you have no success at locating Newbury. You must make a journal entry to debit (decrease) allowance for doubtful accounts for $1,000 and credit (reduce) Accounts Receivable–Newbury Supplies for $1,000. Now, what if the owner of Newbury Supplies sends you a check for the $1,000 after you’ve written off the balance due? Then you record the payment by debiting cash and crediting allowance for doubtful accounts. Keep in mind that you already removed (credited) the receivable when you determined the amount was uncollectible. So, when you collect on a receivable that has been written off already, you don’t post an entry to accounts receivable. The allowance method for bad debt adheres to the accounting principle of conservatism. The principle is discussed throughout this book. When in doubt, the principle instructs the accountant to err on the side of conservatism. That means that you should delay recognizing revenue until you’re certain about your estimate. You should also recognize expense sooner rather than later. The principle helps you generate financial statements that aren’t overly optimistic. The allowance method posts bad debt expense early. The bad debt entry is based on your estimate of bad debt. When you’re certain that a customer won’t pay, you reduce (debit) the allowance account and reduce (credit) accounts receivable. Going over the direct write-off method Using the direct write-off method, you post bad debt only when you’re certain that you won’t be paid. It doesn’t use an allowance account to estimate uncollectible balances, so it doesn’t meet GAAP requirements. When an account is determined to be uncollectible, the direct write-off method requires you to debit (increase) bad debt expense and credit (reduce) accounts receivable. For more about the direct write-off method, see Book III, Chapter 6. Note the difference between the allowance and direct write-off methods. The allowance method posts bad debt when you estimate uncollectible balances. The direct write-off method posts the bad debt only when you’re certain that you won’t be paid. Because the allowance method posts bad debt sooner, the approach is more conservative, thus conforming to GAAP. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 230 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Notes receivable A note receivable is a short-term debt that someone owes you, meaning it comes due within 12 months of the balance sheet date. In many cases this current asset arises from a trade receivable: money your customer owes you for the purchase of goods or services you rendered. This situation can arise if the customer has cash flow problems that prevent it from paying for a purchase. The customer goes to its vendor and asks for extended terms in a formal written document, which replaces the less formal agreement to pay for the goods or services — the invoice. A note receivable has three major components: ✓ Principal: The amount owed to the company by the debtor. ✓ Rate: The amount of interest the debtor pays on the principal. It’s almost always stated as an annual rate, even if the note is for a period shorter than one year. ✓ Time: The period in which the debtor has to pay back the note. If you ever have to convert an accounts receivable to a note receivable, you can breathe a sigh of relief because it’s a simple journal entry (see Book I, Chapter 3). You increase (debit) notes receivable and decrease (credit) the customer’s accounts receivable. A note receivable appears in the current asset part of the balance sheet only for the debt you anticipate will be paid back within 12 months of the balance sheet date. Any portion of the note receivable extending past that 12-month period gets put in the long-term asset section of the balance sheet. Inventory Inventory is another current asset you need to account for in the asset section of the balance sheet. You need to account for two different types of inventory. The first is retail inventory, which is merchandise available for sale in stores and shops. The second, used by manufacturers, is product inventory, which includes direct materials: work in process and finished goods. Book VIII, Chapter 2 is devoted entirely to inventory. The following two sections give you brief descriptions and examples of inventory terms. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 231 Retail (or merchandise) inventory Accounting for retail inventory is easier than accounting for manufacturing inventory because a merchandising company, such as a retail store, has only one class of inventory to keep track of: goods the business purchases from various manufacturers for resale (the goods on the store’s shelves). Here’s an example of how a retailer handles an inventory purchase: The associate in charge of lawn mower inventory at a major home improvement store notices that the department is running low on a certain type of mower. He informs the department manager. The manager follows the department store’s purchasing process, and the department receives a shipment of mowers from its vendor. This transaction is a purchase, which is part of inventory (an asset account). When the mowers are sold, the inventory is reclassified as cost of goods sold (an expense account). Manufacturing inventory Because a manufacturing company doesn’t simply buy finished goods for resale to customers, it has a more complicated inventory with three major components: ✓ Direct material inventory: Also known as raw materials, this inventory reflects all materials the company owns that it will use to make a product. For the lawn mower manufacturer, raw materials include the steel to form the body, leather or fabric for the seat, and all the other gizmos and parts that make the mower work. In essence, any materials that you can directly trace back to making the mower are direct material inventory. ✓ Work-in-process inventory: At any point in time during the manufacturing process, the company probably has items that are in the process of being made but aren’t yet complete, which is work in process. With a lawn mower manufacturer, this category includes any mowers that aren’t completely assembled at the end of the financial period. The company values its work-in-process inventory based on the mower’s percentage of completion. If the mower is 70 percent complete, the mower’s cost is likely to include 70 percent of the costs incurred. ✓ Finished goods: These are costs you associate with goods that are ready for sale to customers but haven’t yet been sold. For the lawn mower manufacturer, this category consists of mowers not yet sold to retailers, such as hardware stores. Finished goods can end up in two places: If you sell the goods, the cost is posted to cost of sales (an expense account). If you don’t sell the finished goods, the cost is included in ending inventory — an asset account. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 232 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Companies can use many different methods to place a dollar value on ending inventory. See Book VIII, Chapter 2 for details. Prepaid expenses Rounding out the discussion of current assets are prepaid expenses, which are expenses the business pays before they’re due. Many companies pay six months’ worth of business insurance in advance. In a similar way, your car insurance policy requires insurance premium payments before your coverage starts. Companies may also pay rent in advance. Prepaid expenses are considered an asset, because you don’t have to pay for the expense later. For example, assume a company pays an invoice for $1,200 that covers 12 months of car insurance for the company vehicle. You originally book this amount as an increase (debit) to prepaid expense and a credit (reduction) to cash. Then, as each month goes by, you move the portion of the insurance cost from the balance sheet to the income statement. Each month, you debit (increase) insurance expense for $100 ($1,200/12 months) and credit (reduce) prepaid expense for the same amount. See Book III, Chapter 6 for additional coverage of prepaid expenses. Keeping Track of Noncurrent (Long-Term) Assets Recall that assets are used to make money in your business. You classify an asset as noncurrent or long-term if the asset will be used up over the course of more than 12 months after the date of the balance sheet. For example, any part of a note receivable that the company expects to receive after the 12-month cutoff date is classified as noncurrent. Natural resources such as coal, oil, and timber are also noncurrent assets. So are mineral deposits, such as gold and diamonds. This section focuses on the most common types of noncurrent assets you’ll encounter, starting with tangible assets and then moving on to intangibles. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 233 Meeting the tangibles: Property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) Tangible assets, also called fixed assets, include property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) — a category that includes land, buildings, equipment, furniture, and fixtures. The following sections describe the various tangible assets included in PP&E. Land Land, also called real property, is the earth on which the company’s office buildings or manufacturing facilities sit. The cost of the land plus any improvements the company has to make to the land to use it for business operations is your total cost. Land is posted to the balance sheet at historic cost. Four types of costs are included in the land account: ✓ Contract price: The purchase price for the land. ✓ Closing costs: Expenses to exchange the title of the land from buyer to seller. These costs include real estate broker commissions, legal fees, and title insurance. ✓ Survey costs: Costs for a land surveyor to give you a professional opinion as to where the boundaries of the property lie. ✓ Land improvements: Expenses the company incurs to get the land ready for use, which include the cost of clearing the land if necessary to build the manufacturing plant or adding sidewalks and fences to an existing property. Because land isn’t considered to be “used up” the way that other PP&E is, land is never depreciated. If a company buys land as an investment, you record it in the investment section of the balance sheet rather than PP&E. Wondering whether it would go in the current or long-term section? Well, that classification depends on how long the company plans on owning the land. If it anticipates selling the land within 12 months of the balance sheet date, it’s a current asset. Otherwise, record it as noncurrent (long-term). Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 234 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Buildings This category covers the company-owned structures in which the company conducts business operations. It includes office buildings, manufacturing facilities, and retail shops. If the business owns off-site storage facilities or warehouses, these assets go in the buildings category too. Unlike land, buildings are depreciable (see Book III, Chapter 1). Also, when preparing a balance sheet, make sure you list land and buildings separately because doing so is a GAAP requirement. To figure out the cost of the land and buildings separately, do one of the following: ✓ If the business purchased the land and buildings together, hire an appraiser to determine the value of the land and the value of the building. ✓ If the business purchased a piece of raw land and constructed its own building, use the purchase agreement to determine the value of the land and all invoices related to erecting the building to determine its value. Equipment This category is quite broad, encompassing any equipment a company uses to make the products it sells to customers. For example, a manufacturing company such as a bread baker includes all the mixers, ovens, and packaging machines it uses to turn the yeast and flour into loaves of bread and package them to ship to grocery stores. A merchandising company (a retailer, which doesn’t make any products) includes in this category any office computer equipment it owns, plus forklifts or mechanized ladders to move inventory around. Retail shops categorize their cash registers as equipment. Furniture and fixtures Last up in the parade of PP&E are furniture and fixtures, which include desks, chairs, and filing cabinets. Add to these three very common examples any other furniture items you see in an office setting: credenzas, conference tables, area rugs — the list goes on and on. A merchandiser has fixtures to present wares for sale, such as glass display cases and display racks. Mannequins are also considered fixtures and, depending on their quality, can be a very high dollar item on the balance sheet. If the company leases any of its PP&E, the leased items may not be considered company property and don’t show up in the PP&E section of the balance sheet. However, if the lease has aspects of ownership that pass the GAAP sniff test, you do record the leased asset on the balance sheet as a capitalized lease. For more about leases, see Book V, Chapter 4. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 235 Investigating intangible assets The big difference between tangible and intangible assets is that intangible assets (usually) don’t have a physical presence. When you really dig into the subject, you’ll probably find intangibles a lot more interesting than steel desks and swivel chairs. The following sections describe the types of intangible assets and explain how to write off intangible assets and generate intangible assets internally. Identifying patents, trademarks, and other intangible assets The first type, which is the most common, includes long-lived assets such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights: ✓ Patents: Patents provide licensing for inventions or other unique processes and designs. Items that patents can protect run the gamut from pharmaceuticals to automobile circuitry to unique jewelry designs. ✓ Copyrights: Securing a copyright means that someone can’t use the company’s printed work (such as books or articles) or recorded work (such as musical scores or movies) without permission. ✓ Trademarks: When a company has a trademarked name or symbol (for example, Xerox), no other company can use it without getting permission from the trademark owner. See “Writing off intangibles by using amortization,” later in this chapter, for details on how to determine the value of these intangible assets and account for them on the balance sheet. Introducing goodwill The second category of intangibles, goodwill, comes into play only when one business purchases another for a price greater than the fair market value of the net assets acquired during the sale. (Net assets are total assets less total liabilities.) For example, ABC Corp. buys XYZ Corp. for $250,000. XYZ’s net assets are $175,000. ABC Corp. acquires $75,000 ($250,000 – $175,000) of goodwill in the transaction. Goodwill is posted as an asset on ABC’s books. Consider the logic of paying more than the fair market value of the net assets when purchasing a company. Net assets represents the true value of the company. If you sell all the assets and use the cash to pay off all the liabilities, you’re left with net assets (equity). So consider why someone would pay more than the net assets. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 236 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The buyer — who pays more than the net asset value — believes that the company has assets or other opportunities not fully valued in the financials. For example, the buyer is willing to pay more for the company’s brand name and reputation in the marketplace. Maybe the company has a customer list, and the buyer believes that he can generate more business from that list. Those are reasons to pay more than the value of net assets. Writing off intangibles by using amortization Amortization is similar to depreciation (see Book III, Chapter 1) because you use amortization to move the cost of intangible assets from the balance sheet to the income statement. Both amortization and depreciation are expenses. Most intangibles are amortized on a straight-line basis, using their expected useful life. Assume, for example, that the U.S. government grants patent protection for a period of 20 years. Unless the patent has become obsolete, 20 years would probably be the expected useful life the business uses for its patent amortization. An obsolete patent has no value. The cost would be immediately expensed. What about the balance sheet cost of intangibles? Leasehold improvements are easy: The amount is the actual cost for any improvements the company makes. The useful life for leasehold improvements is usually the term of the underlying lease. Patents, trademarks, and copyrights the business purchases are treated similarly: You have the cost of purchase as a basis for the amount you amortize. Generating intangible assets for company use The cost of developing an intangible asset in-house can be minimal. For example, maybe some employees were just spit-balling in a meeting and came up with a catch phrase that eventually became very valuable because of the success of the product associated with the phrase. In this case, the company can include the legal costs to file the trademark with the federal government in a trademark asset account. Legal expenses incurred to defend the trademark against infringement (unauthorized use) can also be added to the trademark asset account. Keep in mind, however, that most research and development costs to create an intangible asset are expensed as incurred. Those costs aren’t posted to an asset account. The second category of intangibles, goodwill, is never amortized. Accountants test goodwill yearly for impairment. The company determines whether any goodwill has declined in value and writes off (removes) that value from the balance sheet. Chapter 3: Assessing the Balance Sheet’s Asset Section 237 Exploring the Asset Section of the Balance Sheet To wrap up this chapter, Figure 3-1 shows what the asset section of the ­balance sheet looks like. Liabilities and equity are each merely a line item in Figure 3-1. Check out Chapter 4 to see the liability section and Chapter 5 to see the equity section of a balance sheet fully developed. Figure 3-1: The asset section of a balance sheet. Book IV ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Current assets are always shown first, in order of liquidity, followed by any long-term assets, which typically include notes receivable (notes due more than 12 months past the balance sheet date). The company’s PP&E appears next with the accumulated and amortization shown as a separate line item at the bottom of the section. Appearing at the end are any nonphysical intangibles — usually net of amortization, which means that amortization is subtracted before listing the intangibles’ values on the balance sheet. Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 238 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Chapter 4 Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section In This Chapter ▶ Discovering how a company raises cash ▶ Identifying current liabilities ▶ Finding out about long-term debt ▶ Knowing when loss contingencies are reportable ▶ Accounting for bonds N obody likes debt, but it’s often an inevitable part of a company keeping its doors open for business. This chapter covers both current and longterm debt, collectively known as liabilities. You discover the types of current liabilities that help a business manage its day-to-day operations. You also find out about long-term debt obligations that businesses use to acquire assets. This chapter discusses basic long-term debt — such as mortgages and notes payable — and bonds, focusing on the many facets of this complicated topic. A third type of liability — loss contingencies — also gets some space in this chapter. These liabilities aren’t always included in financial accounting reports; you get the lowdown on when and how to include them. Seeing How Businesses Account for Liabilities Liabilities are claims on company assets (cash) by other businesses or its employees. Because a company uses assets to pay liabilities, accountants refer to liabilities as a “claim on assets.” Examples include: 240 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets ✓ Accounts payable: Money a company owes to its vendors for services and products it purchased. ✓ Unearned revenues: Money received from clients before the business provides goods or services to the customer. When you pay for a oneyear magazine subscription, your payment is unearned revenue to the magazine publisher. The revenue isn’t earned until the publisher starts to deliver magazines to you. ✓ Salaries payable: Wages the company owes to employees. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP, discussed in Chapter 1) dictate that when you prepare the liability section of the balance sheet, any claims against the company have to be broken out between current and long-term obligations. For this book, the dividing line between the two is the one-year mark: All liabilities that are due within one year of the balance sheet date are considered current. All others are considered long-term. If a company refinances a current liability, that new liability may be treated as long-term. For example, a company may replace an accounts payable balance with a note payable (a formal loan document to pay the balance — possibly owed over several years). See Chapter 2 for details. Book I, Chapter 1 introduces the fundamental accounting equation, which is: Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity Based on the order of elements in this equation, liabilities show up on the balance sheet after total assets but before equity accounts, with current liabilities first, followed by long-term liabilities. (Current and long-term assets receive similar treatment; see Chapter 3.) Using the accrual method of accounting (explained in Book I, Chapter 4), all revenue must be matched with expenses incurred during the production of that revenue. So if a company incurs costs but money doesn’t change hands, a liability shows up on the balance sheet to reflect the amount that eventually has to be paid. For example, the company may make a purchase from a vendor without immediately paying for it. That item will appear in accounts payable, which is a current liability. Figure 4-1 shows a simple liability section of the balance sheet, with all asset and equity accounts consolidated to a single line item each (the two shaded lines). Check out Chapter 3 for a more formal presentation of all sections of the balance sheet. Also note that each account’s chart of account number is included. (See Book I, Chapter 2 for more info about the chart of accounts.) A formal balance sheet usually won’t include chart of account numbers. Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 241 Figure 4-1: The liability section of a balance sheet. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Keeping Current Liabilities under Control This section introduces nearly every type of current liability you’re likely to encounter. It even tosses in some journal entries, so you can see how the transactions get into the accounting records (see Book I, Chapter 3). But before you start, you need to understand the reason why breaking out current from long-term liabilities is so important. GAAP requires the division so the user of the financial statements can easily glean the information necessary to compute several important financial ratios. Liquidity ratios measure how well a company is prepared to pay short-term liabilities (bills due in less than a year) with assets available in the short term. One important liquidity ratio is working capital, which is current assets minus current liabilities. A variation on working capital is the current ratio, which is current assets divided by current liabilities. These ratios are important to many users of financial reports, who may be investors, banks, or anyone else with an interest in the company’s financial health. These financial ratios and tools (spelled out in Book V, Chapter 3) give the user specific criteria for deciding how well the company is performing. For example, a bank’s loan officer deciding whether to loan a business money wants to gauge the expectation of being paid back on time. Working capital and the current ratios are very helpful in that arena. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 242 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets For this reason, netting current assets with current liabilities is rarely okay under GAAP. To do so would eliminate the ability to use any sort of ratio ­analysis involving current asset or liability accounts. For example, if you purchase inventory on account (on credit), both the inventory and accounts payable accounts increase. Accounts payable Accounts payable (A/P) includes money a company owes its vendors for services and products it has purchased. Accounts payable is a current liability, because the company anticipates paying the liability in the short term. For example, the company purchases inventory from a manufacturer. The transaction originally goes in the purchases journal, which shows purchases on account, with a debit going to whatever cost or expense account is most applicable and a credit going to accounts payable. Per GAAP, A/P is always assumed to be a current liability. However, a transaction originally entered as A/P could eventually be reclassified as a long-term debt. This change may happen if the company couldn’t pay the vendor and the vendor agreed to convert the short-term A/P to a long-term note (a formal document showing an amount owed and a mutually acceptable interest rate and payback period spanning more than a year). Note that the terms accounts payable and trade payables are often used synonymously. But technically, trade payables generally refer to vendors from which a company buys business supplies and direct materials — items it uses to manufacture products for sale (see Book VII, Chapter 4). Accounts payable includes all vendors you intend to pay within a year. Some accounting systems may include both categories simply as accounts payable. Many vendors selling on credit give a discount to customers who pay their balances early. For example, the terms of the purchase may call for full payment in 30 days but a discount of 2 percent if the customer pays the bill within 10 days. Accountants refer to this type of arrangement as 2/10 net 30. If the company got a 1 percent discount for paying in 15 days with the total amount due in 45 days, it looks like this: 1/15 net 45. The seller is willing to accept a smaller payment (by offering a discount) in order to collect the payment sooner. Collecting payments quickly provides the business more cash to operate. Figure 4-2 illustrates the debiting and crediting for $1,000 of inventory purchased on account with discount terms of 2/10 net 30 and the subsequent payment. Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 243 Figure 4-2: Inventory purchase on account and payment within discount period. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Payroll and taxes The nature of the beast is that most companies accrue payroll and related payroll taxes. With an accrual, the business recognizes a liability that hasn’t yet been paid. At the end of many accounting periods, a company may owe payroll to employees. This concept is easy to understand if you think about the way an employer has paid you in the past. Most companies have a built-in lag time between when employees earn their wages and when the paychecks are cut. For example, Penway Manufacturing pays its employees on the 1st and 15th of every month with 15 days of wages in arrears. This means that when the employees get their paychecks on July 15, the paychecks compensate work they did from June 16 through June 30. To match expenses to revenue when preparing financial statements for the one-month period ending June 30, the gross wages earned but not yet paid as of June 30 have to be added to the balance sheet as a current liability. You also have to account for any payroll taxes or benefits that will be deducted from the employees’ paychecks when the checks are finally cut. Book II, Chapters 4 and 5 provide details on these topics. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 244 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Unearned revenue Unearned revenue is a liability that arises when a company receives payment for goods or services rendered before it has actually provided the goods or services. Because the business has an obligation to deliver the product or service, the unearned revenue is a liability until the company completes its end of the transaction. Unearned revenue can be a short-term (a year or less) or a long-term liability. To record revenue, it has to be earned and realizable. If the customer pays in advance, the revenue is realized. However, the revenue isn’t earned until the product or service is delivered to the client. Suppose you pay a $1,200 deposit to a cabinet maker to build customized cabinets for your office building. Until the cabinet maker delivers the cabinets to your office, your payment isn’t 100 percent earned revenue for the cabinet maker. The way this works on the cabinet maker’s end is that it debits cash and credits unearned revenue for your payment of $1,200. After delivering the completed cabinets, it records revenue by debiting (reducing) unearned revenue and crediting (increasing) gross sales for $1,200. Other short-term liabilities Other short-term liabilities include items such as loan payments that are payable within 12 months. Current debt can originate as short-term bank loans, or it can be the portion of a long-term debt that’s due within the next 12 months. Another type of current liability you’re likely to encounter is estimated warranty, which reflects how much money a company may have to pay to repair or replace products sold to customers. Here’s more information on short-term bank loans, current maturities of long-term debt, and estimated warranty expense: ✓ Short-term bank loans: When a company takes out a loan, it doesn’t always have to be for an extensive period (such as a 30-year mortgage). Frequently, a company anticipates getting paid for a job it has performed and just needs a brief influx of cash to pay expenses such as payroll. A good example of this situation is a working capital loan, which a bank makes with the expectation that the loan will be paid back from collection of accounts receivable. As long as the loan is due in full fewer than 12 months after the balance sheet date, you classify borrowed funds as current liabilities. Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 245 Short-term debt is important to examine when determining the financial health of a company because it indicates whether a cash flow issue could arise in the future. If the short-term debt is unreasonably high, the company may not have the excess money to make the loan payments. A company can also have a revolving line of credit, which is a loan with a preset limit on how much the company can withdraw at any one time. This type of financing is considered a current liability. This sort of ­current debt is much more flexible than a loan because the company borrows against it only when necessary. ✓ Current maturities of long-term debt: Suppose a company has a 30-year mortgage on its land and building, and it’s in the third year of paying off the loan. To properly reflect this mortgage on the balance sheet, the principal amount the company owes in the next 12 months has to be recorded as a current liability. The rest of the mortgage payable is a long-term liability, a subject covered in the next section. You can use an amortization schedule, which shows how much of each mortgage payment goes to principal versus interest, to figure out the current portion of the long-term debt. ✓ Estimated warranty liability: Warranties on products may be included in the purchase price of a product or something the purchaser elects to buy separately — usually at the time of purchase. A great example is the guarantee of performance relating to the purchase of a computer from an electronics retail shop. For example, the computer comes with a sixmonth warranty from the manufacturer covering numerous performance and repair issues. If the computer breaks down within the six-month warranty period, the purchaser can send it back to be fixed, free of charge. The company has to take two steps in this situation to ensure its financial reports are complete: • Provide a disclosure about the warranty in a footnote to its ­financial statements (see Book V, Chapter 4) • Calculate and book an estimate of how much it costs the company to fulfill the terms of the warranty A popular way to estimate warranty expense is to use a percentage of sales. This percentage is normally figured historically. If in the past the company has incurred an actual warranty expense of 4 percent, that same percentage should be the current year’s estimate until the facts change. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 246 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Here are the steps to estimate and record warranty expense: 1. Compute the total dollar amount of sales under warranty. 2. Calculate the dollar amount of warranty expense. Use a percentage of total sales based on your experience with warranty expenses in past years. 3. Post an entry to debit estimated warranty expense and credit accrued warranty liability for the warranty estimate. 4. Debit accrued warranty liability and credit cash for actual payments for warranty expenses. 5. Compare your estimate of warranty expense with your actual payments for warranty expenses (cash payments). Consider whether the warranty estimates should be increased or decreased to accurately reflect your warranty expenses going forward. Ready to see how to journalize these transactions? Figure 4-3 gives you the lowdown on the entry to book the estimate and record actual warranty expense. Figure 4-3: Recording accrued and actual warranty expense. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Planning for Long-Term Obligations If you own a car you financed, you’re probably all too familiar with long-term debt — loans that won’t be paid off within the next 12 months. Companies have long-term debt, too. Although a company usually uses current liabilities (loans) as a vehicle to meet short-term obligations such as payroll, it may incur long-term debt for the financing of company assets. Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 247 Financing asset purchases with debt versus equity Corporations raise money to purchase assets in one of two ways: debt or equity. Debt means the company borrows money with an obligation to pay the borrowed funds back. Equity means the company sells shares of its own stock to investors. If you issue debt, you have creditors. If you issue stock, the purchasers of your stock are owners. What makes equity investing appealing is that the company may not be under any obligation to buy back the shares of stock from the investors. However, it also means that equity investors have some say in the decisions of your business, including voting rights on major corporate decisions. Equity investors also want a return on investment, possibly in the form of a dividend. Oddly enough, debt can end up making a company money. This situation is called financial leverage, and it takes place when the borrowed money is expected to earn a higher return than the cost of interest payable on the debt. Additionally, interest expense on debt is normally a tax deduction while dividends payable to investors are not. Here’s an example: You borrow funds at 6 percent to purchase a new machine to manufacture a product. The new machine operates more efficiently. You incur less repair and maintenance cost, and you’re able to produce more product each month. As a result, your company earnings increase by 8 percent. Your 8 percent growth in earnings more than offsets your 6 percent borrowing cost. Book VIII, Chapter 4 provides more insight on this concept. Managing long-term debt If the company needs to raise cash and decides to do so by accumulating debt, the most common types are mortgages, notes payable, capitalized leases, and bonds. Following is your accounting guide to the first three of these categories of long-term debt. Bonds are a much more complicated subject, covered later in this chapter in the section “Accounting for Bond Issuances.” Any type of debt instrument between a lender and a borrower specifies principal (the amount borrowed), rate (how much interest the company pays to borrow the money), and term (the duration of the note). A portion of each payment is applied to principal and the other portion to interest. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 248 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Mortgages Mortgages are used to finance the purchase of real property assets (building and land, for example). The property collateralizes the mortgage, which means that the property is held as security on the mortgage. If the borrower defaults on the mortgage, the lending institution seizes the property and sells it to recoup as much of the borrowed money as possible. Notes payable Notes payable are formal written documents that spell out how money is being borrowed. The earlier section “Other short-term liabilities” explains that the part of a note payable that’s going to be paid off within the 12 months of the balance sheet date is classified as short-term debt. The remainder of the note is considered a long-term debt. Capitalized leases Another type of long-term debt involves capitalized leases. A company doesn’t always buy its fixed assets (see Chapter 3); sometimes it leases them. Leasing often makes sense for any fixed asset that’s replaced frequently. For example, leasing computers makes sense for businesses that need to stay current with computer technology. Capital leases have characteristics of ownership, which means the cost of the leased capital asset goes on the balance sheet as a depreciable asset. This book offers a full discussion of accounting for leases in Book V, Chapter 4. Anticipating contingent liabilities A contingent liability is a liability that may cause a future loss depending on events that may or may not occur. Here are two examples of common contingent liabilities: ✓ Pending litigation: A company is actively involved in a lawsuit that hasn’t been settled. ✓ Guarantee of obligations: A business agrees to step in and satisfy the debt of another borrower if need be. A company may guarantee the debt of a supplier if the supplier’s product is critical to the company’s production process. Perhaps the supplier can’t operate without a loan, and the lender insists on a co-signer for the loan to be approved. You typically record contingent liabilities in the footnotes to the financial statements (see Book V, Chapter 4) rather than as a dollar amount in the ­financial statements. However, if a loss due to a contingent liability meets the Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 249 following two criteria, it should be accrued and reported in the company’s financial statements as a dollar amount: ✓ The chance of the loss event happening is probable — likely to occur. Consider the guarantee of obligation example: If the debtor business (the supplier) has gone out of business and the owners have disappeared into the night, the lender will probably come after the back-up guarantor to pay off the loan balance. ✓ The amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated, which means you can come up with an accurate dollar amount of the loss. Continuing with the guarantee of obligation example, the loss is reasonably estimated because it should be the remaining balance on the loan, interest owed, and any additional charges tacked on by the lender in accordance with the obligatory note. If the loss contingency meets these two standards for accrual, the journal entry involves a debit to a relevant loss account (an expense) and a credit to a liability account. For example, the company could take the debit to “loss on guaranteed debt” and to some sort of liability account such as “amount due on guaranteed obligation.” Accounting for Bond Issuances Bonds are long-term lending agreements between borrowers and lenders. For example, a municipality (such as a city or village) may issue bonds to finance the building of new roads or a hospital. Corporations generally issue bonds to raise money for capital expenditures, operations, and acquisitions. The person who purchases a bond receives interest payments at the bond’s stated interest rate during the bond’s term or for as long as he holds the bond. When the bond matures (the term of the bond expires), the company pays the bondholder back the bond’s face value, or principal amount. A bond is either a source of financing or an investment, depending on which side of the transaction you’re looking at. The company issuing the bond incurs the long-term liability. The person or company acquiring the bond views it as an investment; for a business, this investment is an asset. Mulling over bond basics Bonds are normally issued at face amount (the principal amount printed on the bond, as explained in the following list). When a bond is issued, it’s sold to the public for the first time. After issuance, a bond may be bought and sold between many investors over time, based on the market price for the bond. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 250 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The market price of a bond can be expressed in one of three ways: ✓ Face amount (also known as par value): The principal amount printed on the bond, typically in denominations of $1,000 ✓ A discount: Less than face value ✓ A premium: More than face value When considering bond prices and rates of return, consider the following: ✓ Principal repayment: The bond issuer is obligated to repay the face amount at maturity regardless of the price the investor paid for the bond. For example, if the bond’s face amount is $1,000, the bond issuer must pay back $1,000. ✓ Interest payments: Most bonds pay interest monthly or semi-annually (twice a year). Bonds issued by corporations typically pay interest semi-annually. ✓ Yield to maturity: An investor has two cash flows that impact his or her total return. One cash flow is the interest payments, which are based on the stated, fixed interest rate. Investors may also have a gain or loss, depending on whether they bought the bonds at a premium or a discount. The interest income plus the gain or loss is the yield to maturity. You can view yield to maturity as the total return on the bond investment. Examining sample bond transactions To get a handle on bond prices and yield to maturity, consider an example of a bond purchased at a discount, and then an example of a bond bought at a premium. Buying a bond at a discount A $1,000, 6-percent, 10-year face amount bond is originally issued at $1,000. One year later, an investor purchases the bond at $920. Because the purchase price is less than the face amount, the bond is purchased at a discount. That investor has two cash flows: ✓ Annual interest payments of $60 ($1,000 × 6 percent) ✓ The principal amount paid at maturity, less the cost of the bond ($1,000 – $920 = $80) The investor’s yield to maturity (total return) is more than 6 percent. That’s because the investor earns $80 when the bond matures, along with the 6 percent interest rate. When you buy a bond at a discount, you earn more than the stated interest rate of the bond. Chapter 4: Digging for Debt in the Balance Sheet’s Liabilities Section 251 Investing in a bond at a premium Using the same numbers, assume a 6-percent, 10-year face amount bond is originally issued at $1,000. One year later, an investor purchases the bond at $1,050. Because the purchase price is more than the face amount, the bond is purchased at a premium. That investor has two cash flows: ✓ Annual interest payments of $60 ($1,000 × 6 percent) ✓ The principal amount paid at maturity, less the cost of the bond ($1,000 – $1,050 = –$50) The investor’s yield to maturity (total return) is less than 6 percent, because the investor loses $50 when the bond matures. When you buy a bond at a premium, you earn less than the stated interest rate of the bond. Kicking around the logic of paying a premium Given the fact that paying a premium for a bond reduces the net interest earned, you may wonder why an investor would pay a premium for a bond. Bonds are priced at a premium because the stated interest rate on the bond is higher than the interest rate of bonds currently being issued (for the same maturity and credit quality). Consider the example in the previous section. Assume 10-year maturity bonds of similar creditworthiness are being issued at a 5-percent interest rate. An investor may pay $1,050 for the 6-percent bond, because current bonds being issued have a stated rate of less than 6 percent. The investor is willing to pay an extra $50 to earn more interest income. This discussion also explains why bonds are priced at a discount. If a bond’s stated interest rate is less than similar bonds currently being issued, the market price of the bond is less than the face amount. If bonds are being issued at 5 percent, an existing 4-percent interest rate bond sells at a discount. Book IV Journaling bond transactions When a company issues a bond and when the bond is purchased (at a premium or a discount), the company must make a journal entry to record the activity, as explained in the following sections. Issuing a bond As mentioned in a previous section, bonds are most often issued at face amount (par value). If a bond is issued at par value of $1,000, the entry is to debit cash $1,000 and credit bond payable (a liability account) for $1,000. Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 252 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Issuing a bond means that the company is selling the bond to an investor. As a result, the company receives cash from the buyer. Issuing a bond at a premium or discount doesn’t happen that often, so you don’t need to concern yourself with those scenarios. Accounting for a bond purchased at a premium Assume a buyer purchases a $1,000 bond for $1,020. Because the buyer pays more the $1,000, the bond was purchased at a premium. The buyer debits bond investment for $1,000 (the face amount). Premium on bond investment is debited for $20, and cash is credited for $1,020. The premium of $20 is amortized, meaning the bond premium is moved into an expense account over time until the bond matures. The premium is an extra cost to the buyer. Handling a bond purchased at a discount Assume the buyer purchases a $1,000 bond for $980. Because the buyer pays less than the $1,000, the bond is purchased at a discount. The buyer debits bond investment for $1,000 (the face amount). Note that the bond investment is debited for $1,000 — regardless of whether the bond is bought at a premium or discount. Discount on bond investment is credited for $20, and cash is credited for $980. The discount of $20 is also amortized. In this case, the bond discount is moved into an income account over time until the bond matures. So, the bond discount is extra income to the buyer. Considering the bond seller’s entries Now consider the seller of the bond and the related entries. When selling a bond at a premium, the seller receives more than the face amount. The premium must be amortized over time into an income account. On the other hand, when selling at a discount, the seller receives less than face amount. That discount must be amortized into an expense account. What you should notice is that additional expense for the buyer generates income for the seller. The reverse is also true: Additional income for the buyer results in more expense for the seller. Understanding debt and other liabilities is a critical area for a business owner. Debt is one of the two ways an owner can raise capital to run the business. A manager needs to understand repayment terms and the total liabilities on the balance sheet in order to make well-informed business decisions. Chapter 5 Explaining Ownership in the Equit y Section of the Balance Sheet In This Chapter ▶ Meeting the three types of business entities and two types of stock ownership ▶ Investigating paid-in capital and retained earnings ▶ Checking out reductions in stockholder’s equity ▶ Understanding how corporations pay their investors T his chapter gets into the nitty-gritty of how the owners’ interest in the business shows up on the balance sheet. Equity (also referred to as net assets) is the combined total of each owner’s investment in the business. Both terms refer to the difference between assets (resources a company owns) and liabilities (claims against the company). Understanding How Owner Equity Varies among Business Entities Depending on the type of business entity, the owners’ equity section of the balance sheet can range from bare-boned to quite elaborate, as explained in the following sections. For more about different business entities in general and the pros and cons of each, check out Book VI, Chapter 2. Sole proprietorship Sole proprietorships (one-owner businesses) have an equity account called owner capital. Cash and other contributions that the owner makes to the business, such as equipment, increase the owner capital account. Business earnings (net income) also increase the owner capital account. 254 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets The owner draw account shows money and other assets the owner takes from the business to convert to personal use. Owner draw reduces the owner capital account. Although owner draws are accounted for in a unique account, keep in mind that you need to keep track of owner draw activity to calculate owner capital. Here’s a formula to calculate an owner’s capital balance: Owner’s capital balance = Beginning capital balance + Owner capital contributions + Year-to-date net income – Capital draws Figure 5-1 shows the owner’s equity section of the sole proprietorship for Penway Manufacturing owned by Mike Penway. Figure 5-1: A statement of owner’s equity for a sole propri­ etorship. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Partnership Partnerships (businesses owned by two or more people) mimic sole proprietorships in that the equity section on the balance sheet has capital and draw accounts. Figure 5-2 shows the partner equity section of the DoubleTrouble Partnership, whose partners, Tom and Dottie Double, each own 50 percent of the business. The amount of draws and income distributions a partner is allowed to take can differ from that person’s partnership interest (ownership interest). So even though you have two equal partners, that doesn’t mean they have to take the same draw amount. Hence the differences in beginning and ending partners’ capital accounts between partners in Figure 5-2. If one 50-percent owner takes a higher draw each year, his capital account declines faster over time (everything else being equal). That’s why Tom’s capital account balance is lower than Dottie’s ($12,000 versus $17,000). Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equity Section of the Balance Sheet 255 Figure 5-2: A statement of partners’ equity. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Corporation Unlike sole proprietorships and partnerships, corporations are owned by stockholders. The balance sheet section called “stockholders’ equity” represents the claim shareholders of the corporation have to the company’s net assets. Stockholders’ equity is made up of four components: capital stock, paid-in capital, treasury stock, and retained earnings. Capital stock, paid-in capital, and treasury stock involve transactions dealing with the corporate stock issuances and repurchases. Retained earnings contain income and dividend transactions. The sections that follow give each of these components their due, but first you need to know a little something about the differences in capital stock. Distinguishing between Two Types of Capital Stock To sell ownership in a corporation, the corporation issues stock that investors can purchase. According to general accepted accounting principles (GAAP), all stock transactions must be reported on the balance sheet. The following sections describe the types of stock covered in this book (common and preferred), and show how to record stock transactions on the balance sheet. Preferred stock Preferred stock has two advantages over common stock (discussed next). First, preferred stock shareholders receive their dividends before common stock shareholders. If earnings are insufficient to pay both common and preferred dividends, only the preferred dividend is paid. The preferred dividend is a specific amount, stated as a percentage or a dollar amount. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 256 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets If a corporation sells its assets and closes its doors, preferred shareholders receive their portion of the sales before common shareholders receive theirs. In other words, in the event a company liquidates, preferred shareholders are more likely to recoup all or a portion of their investment in the company. Common stock Common stock shareholders also may earn a dividend. However, the amount of the dividend is at the discretion of the corporation (the dividend amount isn’t stated). The dividend may be higher or lower than last year — or even zero for the year. In the unfortunate event a corporation is liquidated, a common shareholder’s claim on assets comes after preferred shareholders’ claims are paid. In fact, common stock claims on assets are last in line — after bondholders, creditors, and preferred stockholders. Recording stock transactions on the balance sheet GAAP dictates that you properly describe stock transactions on the balance sheet. Figure 5-3 shows the proper balance sheet descriptions for common and preferred stock. Note the following terms: Figure 5-3: Capital stock balance sheet descrip­ tions. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equity Section of the Balance Sheet 257 ✓ Par value: The value per share that’s posted to the stock account balance. Note the difference in par values for common and preferred stock. Common stock has a par value of $5; preferred stock is $200. ✓ Authorized shares: The maximum number of shares the corporation can issue, according to its articles of incorporation. When a company is formed, the owners determine how many shares they want to authorize. ✓ Issued shares: Authorized shares sold to the public. ✓ Outstanding shares: Authorized and issued shares held by the public. If the corporation repurchases issued shares, they’re considered treasury stock. Treasury stock shares aren’t outstanding. (See “Buying back shares: Treasury stock,” later in this chapter, for details.) ✓ Dividend: As you see in the prior section, the preferred stock dividend is a stated amount: 5 percent in this case. The 5 percent is based on the $200 par value. So the dividend is 5 percent × $200, or $10 per share. The common stock doesn’t have a stated dividend amount. Defining Paid-In Capital Paid-in capital represents money invested in the business (contributed capital). Paid-in capital has two components: ✓ Par value of common or preferred stock: The par value of the stock purchased (either common or preferred) multiplied by the number of shares purchased. If you buy 100 shares of $5 par value common stock, you would post $500 (100 × $5) to the common stock line in the balance sheet. ✓ Additional paid-in capital: Additional paid-in capital is the dollar amount you pay for the stock above its par value. “Additional” in this case refers to “more than par value.” Consider the previous example. Assume you spend $700 to buy 100 shares of the $5 par value common stock. $500 is posted to common stock. The remaining $200 ($700 purchase price less $500 par value) is posted to additional paid-in capital. For additional details about how to issue stock shares, see Book VI, Chapter 1. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 258 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Recording Retained Earnings The retained earnings account lists the sum of all net income earned by the company since inception less all dividends paid to shareholders since the company opened for business. These transactions change the retained earnings balance: ✓ Net income: Net income (profit) for the current year increases retained earnings. A net loss reduces retained earnings. ✓ Dividends: Earnings distributed to shareholders. If a company pays a dividend, the payment reduces retained earnings. Consider this formula for year-end retained earnings: Year-end retained earnings = Beginning retained earnings + Current year net income – Current year dividends For example, assume your company opens its doors on January 2, 2015. On January 2, retained earnings are 0 because the company didn’t previously exist. From January 2 to December 31, 2015, your company has a net income of $20,000 and pays out $5,000 in dividends. On January 1, 2016, the retained earnings amount balance is $15,000 ($20,000 – $5,000). To compute retained earnings as of December 31, 2016, you start with $15,000 and add or subtract the amount of income the company made or lost during 2016. You also subtract any dividends paid during the year. Book IV, Chapter 2 discusses how balance sheet accounts (such as retained earnings) are related to the income statement. Spotting Reductions to Stockholders’ Equity Three accounting transactions reduce stockholders’ equity: incurring a net loss (as explained in the previous section), paying dividends, and repurchasing treasury stock. (The following sections explain how paying dividends and repurchasing treasury stock result in reductions to stockholders’ equity. Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equity Section of the Balance Sheet 259 Paying dividends Dividends are distributions of company earnings to the shareholders in the form of cash (yeah!) or additional stock. For most investors, receiving stock dividends isn’t quite as exciting as getting a check in the mail. However, stock dividends can be quite profitable in the long run, especially if the stock’s price rises, because the investor has more shares to sell. Companies pay dividends only to shareholders of record — investors who own their shares on a specific date referred to as the record date. In other words, an investor can’t simply purchase stock the day before dividends are paid, collect the dividends the next day, and then sell the stock. Calculating dividends Whether your company decides to pay cash dividends or stock dividends, you need to know how to calculate the amount to pay investors of record. Here’s an explanation of both cash and stock dividend calculations: ✓ Cash dividends: Shareholders of record receive cash dividends based upon how many shares of stock they own. For a company to pay cash dividends, two conditions have to be met: • The company has net income for the current period or retained earnings from prior periods. • The company has enough ready cash to pay the dividends. For example, assume an investor owns 1,500 shares of common stock in Penway Manufacturing Corporation. Penway has both a surplus of cash and a retained earnings balance, so the board of directors decides to pay a cash dividend of $12 per share. The investor’s dividend is $18,000 (1,500 shares times $12). ✓ Stock dividends: As the name implies, a stock dividend means that shareholders of record receive additional shares of stock, not cash. The additional shares received are based on the number of shares the investor already owns. This type of dividend is expressed as a percentage rather than a dollar amount. For example, if an investor receives a stock dividend of 5 percent on 1,500 Penway shares, the investor receives an additional 75 shares of stock (1,500 × 0.05). Posting dividends to the accounting records Now that you know the amount of cash or number of shares paid as a dividend, you can post journal entries. (Recording the stock dividend is slightly more complex than the cash dividend entry.) Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 260 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Dividends are not an expense of doing business. They’re a balance sheet transaction only, serving to reduce both cash (in the case of cash dividends) and retained earnings. The reduction to retained earnings for a cash dividend is straightforward: You reduce (debit) retained earnings by the amount of the dividend and credit cash to reduce that account for the payment. Posting the stock dividend is more complex: 1. Determine the fair market value of the stock on the declaration date — the date on which the board of directors decides to pay a dividend. 2. Calculate the total number of shares to be paid as a stock dividend. As explained in the prior section, multiply the stock dividend percentage by the number of shares outstanding. 3. Multiply the fair market value per share by the number of stock dividend shares. This total represents the fair market value of the stock dividend in total dollars. 4. Debit retained earnings for the fair market value in dollars. 5. Credit common stock dividends distributable for the par value of the stock dividend shares. 6. Credit additional paid-in capital for the fair market value of the stock that is greater than the par value. Here’s an example of a stock dividend transaction: Penway declares a 5 percent stock dividend at a time when it has 30,000 shares of $10 par value common stock outstanding. At the date of declaration of the stock dividend, the fair market value (FMV) of the stock is $15. The stock dividend totals 1,500 shares (5 percent × 30,000 shares). The net effect is to decrease retained earnings by $22,500 (1,500 × FMV of $15 per share) and increase common stock dividends distributable by $15,000 (par value of $10 × 1,500 shares). Additional paid-in capital increases by the difference between the two: $7,500. This entry reduces retained earnings and shifts the dollar amount ($22,500) to common stock and paid-in capital. When Penway issues the stock dividend, common stock increases by $15,000 and the common stock dividends distributable is adjusted to zero. Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equity Section of the Balance Sheet 261 Corporations may issue stock dividends when they’re low in operating cash but still want to throw the investors a bone. The investors stay happy because they feel they’re getting more of a return on their investment. Buying back shares: Treasury stock Treasury stock represents shares of stock that a corporation issued (sold) to investors and then bought back. You record treasury stock on the balance sheet as a contra stockholders’ equity account. Contra accounts carry a balance opposite to the normal account balance. Because equity accounts normally have a credit balance, a contra equity account weighs in with a debit balance, because company equity is reduced by treasury stock. For more about contra accounts, see Book IV, Chapter 3. Your journal entry to record the purchase of treasury stock is to debit treasury stock and credit cash (for payments to the sellers of stock). In accordance with GAAP, don’t record any gain or loss on treasury stock transactions. One reason a corporation buys back shares of its own stock is to prevent a hostile takeover. The fewer shares trading in the open market, the smaller the chance that another company can purchase controlling interest. Exploring Stock Splits One other type of stock transaction that doesn’t reduce retained earnings is a stock split, which increases the number of shares outstanding while decreasing the price per share proportionally. A company typically performs a stock split when it believes the share price is too high to attract investors. For example, Penway Manufacturing Corporation stock is trading for $100, and the company thinks the price is too high to attract the average investor. To get the price of the stock down to $25 per share, the company issues a 4-for-1 split. Every outstanding share now equals four shares, each of which is worth $25. The logic here is that one share worth $100 is equal to four shares worth $25. The common stock caption, which is the descriptive line on the balance sheet, changes to reflect the split on the books. If the caption originally read “Common stock, 1,000 shares at $100 par,” it now reads “Common stock, 4,000 shares at $25 par.” Note that the total dollar value remains the same — $100,000 — no reduction to retained earnings. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 262 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Computing Earnings per Share Earnings per share (EPS) is calculated as net income divided by shares of common stock outstanding. (Although variations exist, this is the basic formula most often used to calculate EPS.) Potential investors like to see the EPS calculation so they can make educated investment decisions; earnings per common share is a frequently used measure of profitability. The following sections explain how to calculate EPS for a simple capital structure and give you basic information on EPS in a complex capital structure. Simple capital structure If a company issues only common stock — or common stock with nonconvertible preferred stock outstanding — it has a simple capital structure. The following sections define convertible securities, so you know what nonconvertible stock is, and explain how to calculate the EPS for a corporation that has a simple capital structure. Understanding convertible securities A simple capital structure assumes that the company has no convertible securities outstanding. Convertible securities are those that can be converted into common stock; for example, convertible bonds, convertible preferred stock, stock options, warrants, and rights. Computing EPS for weighted average shares To calculate EPS for a corporation with a simple capital structure, divide income available to common shareholders by the weighted-average number of common shares outstanding for the period. The weighted-average is figured by multiplying the number of shares outstanding by the fraction of the period in which they’re outstanding. For example, if the company has 10,000 shares of stock outstanding in January, February, and March, its weighted average for the year (12 months) is 2,500 (10,000 × 3⁄12). Suppose ABC Manufacturing Corporation has net income of $473,400. During the year, the corporation has 38,000 outstanding shares of $4.50, $70 par value preferred stock, and the weighted-average number of common shares outstanding totals 205,000. The owners of the 38,000 shares of preferred stock get a dividend of $4.50 per share first, which equals $171,000 (38,000 shares × $4.50 per share). This figure has to be subtracted from net income before figuring the EPS of common stock ($473,400 – $171,000 = $302,400). Dividing $302,400 by the shares of common stock outstanding (205,000) equals $1.48 EPS of common stock. Chapter 5: Explaining Ownership in the Equity Section of the Balance Sheet 263 If net income includes items such as extraordinary gains or losses, a separate EPS is required for each major component of income, as well as for net income. See Chapter 2 for more information on gains and losses. Complex capital structure If items that could cause a potential dilution to EPS exist, the company’s capital structure is complex. Dilution refers to the idea that total earnings are spread out over more shares of stock. Convertible securities mentioned in the prior section are potential sources of dilution. Accountants say potential source, because the owner of each security can choose to convert the security to common stock. When the potential for dilution exists, you have to show both basic and diluted EPS. To figure diluted EPS, use the number of common shares outstanding that would be issued if every potentially dilutive share were converted to common stock. Presenting the diluted EPS gives the user of the financial statements the worst-case scenario for EPS, relating to any exercise of existing options or the conversion of existing securities. In other words, diluted EPS displays the lowest possible EPS figure. Check out Figure 5-4 for an abbreviated income statement showing how basic EPS looks, including extraordinary items. Note that the figure includes a line item reflecting diluted EPS. Figure 5-4: Showing EPS and diluted EPS on the income statement. Book IV ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 264 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Chapter 6 Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet In This Chapter ▶ Seeing connections between the income statement and balance sheet ▶ Fitting key pieces into the balance sheet puzzle with operating ratios ▶ Adding assets to the balance sheet ▶ Examining debt versus equity on the balance sheet E very time you record a sale or expense entry by using double-entry accounting, you see the connections between the income statement and balance sheet (see Book I, Chapter 2 for more about double-entry accounting and the rules for debits and credits). A sale increases an asset or decreases a liability, and an expense decreases an asset or increases a liability. Therefore, one side of every sales and expense entry is in the income statement, and the other side is in the balance sheet. You can’t record a sale or an expense without affecting the balance sheet. The income statement and balance sheet are inseparable, but they aren’t reported that way! To properly interpret financial statements — the income statement, the balance sheet, and the statement of cash flows — you need to understand the links between the three statements. Unfortunately, the links aren’t obvious. Each financial statement appears on a separate page in the annual financial report, and nothing highlights connections between related items on the different statements. In reading financial reports, non-accountants — and even some accountants — usually overlook these connections. Chapter 2 presents the income statement, and Chapters 3 to 5 cover the balance sheet. This chapter stitches these two financial statements together and marks the connections between sales revenue and expenses (in the income statement) and their corresponding assets and liabilities (in the balance sheet). Book V, Chapter 2 explains the connections between the amounts reported in the statement of cash flows and the other two financial statements. 266 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Rejoining the Income Statement and Balance Sheet When reading financial statements, you should “see,” in your mind’s eye, lines connecting related amounts on the income statement and balance sheet. Because financial reports don’t offer a clue about these connections, actually drawing the lines, as done in the next section, may help you see the connections. Seeing connections between accounts Here’s a quick summary explaining the lines of connection between items on the income statement and balance sheet, as shown in Figure 6-1, starting from the top and working down: ✓ Making sales (and incurring expenses for making sales) requires a business to maintain a working cash balance. ✓ Making sales on credit generates accounts receivable. ✓ Selling products requires the business to carry an inventory (stock) of products. When inventory is sold, the inventory cost is posted to cost of goods sold — an expense account. ✓ Acquiring inventory items on credit generates accounts payable. ✓ Prepaying expenses (such as insurance premiums) creates an asset account balance. ✓ Depreciation expense is recorded for the use of fixed assets (long-term operating resources). ✓ Depreciation is also recorded in the accumulated depreciation contra account (instead of decreasing the fixed asset account). (For more about contra accounts, see Book IV, Chapter 3.) ✓ Amortization expense is recorded for limited-life intangible assets. ✓ Operating expenses is a broad category of costs encompassing selling, general, and administrative expenses: • Some of these operating costs are prepaid before the expense is recorded, and until the expense is recorded, the cost stays in the prepaid expenses asset account. • Some of these operating costs involve purchases on credit that generate accounts payable. • Some of these operating costs are from recording unpaid expenses in the accrued expenses payable liability. Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 267 ✓ Borrowing money on notes payable generates interest income for the lender and interest expense for the borrower. ✓ Net income results in income tax expense. A portion of income tax expense for the year may be unpaid at year-end. The unpaid balance is recorded in the accrued expenses payable liability. ✓ Earning net income increases retained earnings, which also increases the equity section of the balance sheet. Figure 6-1: Connections between income statement and balance sheet accounts. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Book IV Using transactions to explain the connections Figure 6-1 provides a nice visual tool to connect balance sheet and income statement accounts. Keep that tool in mind as you consider some common accounting transactions, as explained in the following sections. Estimating a receivable balance at year-end Figure 6-1 shows how the sales account (in the income statement) is connected to accounts receivable in the balance sheet. An accountant can use historical trends in these two accounts to project an accounts receivable balance at year-end. Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 268 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Suppose for the year just ended, a business reports $5,200,000 sales revenue, as shown in Figure 6-2. All sales are made on credit (to other businesses). Historically, the company’s year-end accounts receivable balance equals about five weeks of annual sales revenue; in other words, an amount equal to five weeks of annual sales revenue is not yet collected at the end of the year. Figure 6-2: Income statement of a business for the year just ended. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Sales are level throughout the year. To determine the amount of accounts receivable to expect in the business’s year-end balance sheet, divide the $5,200,000 by 52 weeks to get $100,000 per week. After that, multiply by 5 weeks to get $500,000 of sales revenue in accounts receivable. Projecting ending inventory balance and accounts payable If historical trends allow you to project accounts receivable, you may also be able to forecast an ending balance in inventory and a year-end accounts payable figure. Assume the same business has an annual cost of goods sold expense of $3,120,000 (refer to Figure 6-2), and its ending inventory balance historically equals about 13 weeks of annual sales. You can expect the amount of inventory in its year-end balance sheet to be: $3,120,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $60,000 average cost of goods sold per week × 13 weeks = $780,000. Historically, the business’s accounts payable for inventory purchases equals about four weeks of annual cost of goods sold. (Note: The accounts payable balance also includes an amount from purchases of supplies and services on credit, but this example concerns only the amount of accounts payable from inventory purchases.) Here’s how you calculate the amount of accounts payable for inventory purchases you’d expect to see in its year-end balance sheet: $3,120,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $60,000 average cost of goods sold per week × 4 weeks = $240,000. Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 269 Accruing other year-end expenses A company has other expenses in addition to cost of goods sold. You may be able to estimate the amount of other expenses that are accrued at year-end (see Book I, Chapter 3 for more about accruals). Assume a business has annual operating expenses of $1,378,000 (which excludes depreciation, amortization, interest, and income tax expenses). Historically, its year-end balance of accrued expenses payable equals about six weeks of its annual operating expenses. Ignoring accrued interest payable and income tax payable, you’d expect the amount of accrued expenses payable in its year-end balance sheet to be: $1,378,000 ÷ 52 weeks = $26,500 average operating expenses per week × 6 weeks = $159,000. For this same business, the average amount borrowed on notes payable during the year was $1,500,000. The average annual interest rate on these notes was 6.5 percent. To determine the amount of interest expense you’d find in the business’s income statement for the year: $1,500,000 average notes payable × 6.5 percent interest rate = $97,500. Introducing Operating Ratios One way to connect a balance sheet account to the income statement is to use a ratio. Accountants use a variety of ratios to measure financial performance. This section explains the use of operating ratios. An operating ratio expresses the size of an asset or liability on the basis of sales revenue or an expense in the annual income statement. A normative operating ratio refers to how large an asset or liability should be relative to sales revenue or its related expense. You can use operating ratios to judge how a business is performing compared to its own past performance and to the performance of other companies in the same industry. Comparing expected with actual operating ratios To manage businesses, managers compare expected performance with actual results. As explained previously, a normative operating ratio is a benchmark. It’s a result that’s expected or planned. Your actual ratio may differ. The process of evaluating the difference between planned and actual results is called variance analysis. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 270 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Suppose a business, Company X, makes all its sales on credit and offers its customers one month to pay. Very few customers pay early, and some customers are chronic late-payers. To encourage repeat sales, the business tolerates some late-payers. As a result, its accounts receivable balance equals five weeks of annual sales revenue. Thus, its normative operating ratio of accounts receivable to annual sales revenue is 5 (weeks) divided by 52 weeks, which equals 9.615 percent of sales revenue. The 5:52 operating ratio is the normative ratio between accounts receivable and annual sales revenue; it’s based on the sales credit policies of the business and how aggressive the business is in collecting receivables when customers don’t pay on time. When you consider actual results, minor deviations from the normative ratios are harmless. However, significant variances deserve serious management attention and follow-up. Check out Book VII, Chapter 4 for more on variances. Generating balance sheet amounts by using ratios Figure 6-2 presents the annual income statement of Company X. From the sales revenue and expenses reported in the income statement, you can determine the balances of several asset and liability accounts by using the normative operating ratios for the business. Presenting ratios used for balance sheet calculations Operating ratios can be expressed in terms of a number of weeks in a 52-week year or as percentages of annual sales revenue or annual expense. The normative operating ratios for the business whose income statement is presented in Figure 6-2 are as follows (expressed as weeks in a year): ✓ Cash: 7/52 or seven weeks of annual sales revenue ✓ Accounts receivable: 5/52 or five weeks of annual sales revenue ✓ Inventory: 13/52 or 13 weeks of annual cost of goods sold ✓ Prepaid expenses: 4/52 or four weeks of annual selling and general expenses ✓ Accounts payable for inventory acquisitions: 4/52 or four weeks of annual cost of goods sold Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 271 ✓ Accounts payable for supplies and services bought on credit: 4/52 or four weeks of annual selling and general expenses ✓ Accrued expenses payable for operating expenses: 6/52 or six weeks of annual selling and general expenses Calculating balance sheet amounts Using the operating ratios for Company X, whose income statement appears in Figure 6-2, you can determine the balances for the assets and liabilities driven by its sales revenue and expenses. Take the following steps: 1. Determine the revenue or expense account to be used for the operating ratio. 2. Divide the revenue or expense dollar amount by 52 weeks to compute a weekly level of activity. 3. Multiply the fraction you calculated in Step 2 by the total dollar amount of revenue or expense. The result is the dollar amount in the balance sheet account. Using the operating ratios presented in the earlier section, “Presenting ratios used for balance sheet calculations,” you can calculate dollar amounts for the balance sheet accounts: Assets 7/52 × $5,200,000 sales revenue = $700,000 Cash 5/52 × $5,200,000 sales revenue = $500,000 Accounts receivable 13/52 × $3,120,000 cost of goods sold = $780,000 Inventory 4/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses = $110,000 Prepaid expenses Liabilities (4/52 × $3,120,000 cost of goods sold) + (4/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses) = $350,000 Accounts payable 6/52 × $1,430,000 selling and general expenses = $165,000 Accrued expenses payable These asset and liability balances are normative, not the actual balances that would be reported in the business’s balance sheet. See the section, “Comparing expected with actual operating ratios” earlier in this chapter for additional guidance. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 272 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Tackling other balance sheet issues You may find the list of ratios to be straightforward. Calculating other amounts in the balance sheet requires more explanation. These balance sheet accounts aren’t typically derived by using an operating ratio. Consider these points: ✓ Intangible assets: The business doesn’t own intangible assets and therefore doesn’t have amortization expense. An intangible asset, such as a patent or trademark, isn’t usually derived by using an operating ratio. ✓ Accrued interest payable: This year-end liability typically is a relatively small balance compared with the major assets and liabilities of a business. Also, the expense that drives this balance isn’t an operating expense. The year-end balance of accrued interest payable depends on the terms for paying interest on the business’s debt. ✓ Accrued income tax payable: Income tax payable is similar to interest payable. This balance is typically smaller than the other amounts in the balance sheet. The expense that drives this balance is the income tax status of the business and its policies regarding making installment payments toward its annual income tax during the year. Income tax expense isn’t considered an operating expense. ✓ Fixed assets: The ratio of annual depreciation expense to the original cost of fixed assets can’t be normalized. Different fixed assets are depreciated over different estimated useful life spans. Some fixed assets are depreciated according to the straight-line method and others according to an accelerated depreciation method. (See Book III, Chapter 1 for more about these and other depreciation methods.) In Figure 6-3, you can see a partial balance sheet that presents only the assets and liabilities determined in the preceding example. Later in the chapter, you fill in the remainder of this balance sheet, including fixed assets, long-term debt, and owners’ equity (see Figure 6-4, which is also a partial balance sheet). A complete balance sheet is displayed in Figure 6-5. Figure 6-3: Partial balance sheet with asset and liability balances. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 273 Adding Fixed Assets, Depreciation, and Owners’ Equity One asset is obviously missing in the partial balance sheet shown in Figure 6-3: the fixed assets of the business. Fixed assets are usually physical, tangible assets you use to make money in your business (see Chapter 3). Virtually every business needs these long-lived economic resources to carry on its profit-making activities. This section adds fixed assets, depreciation, and owners’ equity to the balance sheet detail. Dealing with fixed assets and depreciation Unfortunately, you can’t use an operating ratio method to determine the balance sheet amount for fixed assets or depreciation expenses for two reasons: ✓ Different fixed assets are depreciated over different estimated useful life spans, using different depreciation methods (such as straight-line and accelerated), so you can’t simply divide total depreciation expense by the original costs of the fixed assets to compute a consistent ratio for expensing fixed assets. ✓ Generalizing about the cost of fixed assets relative to annual sales revenue is very difficult. As a ballpark estimate for this ratio, you could say that annual sales revenue of a business is generally between two to four times the total cost of its fixed assets, but this ratio varies widely from industry to industry and even among companies in the same industry. The cost and accumulated depreciation of a business’s fixed assets depend on these factors: ✓ The type of depreciation method used ✓ When the assets were purchased (recently or many years ago) ✓ Whether the business leases or owns these assets Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 274 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Fitting in fixed assets and depreciation to the balance sheet Next, you see where fixed assets and depreciation fit into the balance sheet. Take a look at the partial balance sheet shown in Figure 6-4. Notice the following: ✓ The total current asset number ($2,090,000) is the same number you see in Figure 6-3. ✓ Figure 6-4 adds three numbers to the asset column. Note that these three numbers are below current assets. That means that the added numbers are long-term assets — assets that will be used over several years. ✓ Total assets in Figure 6-4 are $3,855,000. Note that this total doesn’t balance with total liabilities and equity ($350,000 + $165,000). In fact, the right column doesn’t list any equity. That issue is addressed in the “Tacking on owners’ equity” section later in the chapter. ✓ Book I, Chapter 1 explains the fundamental accounting equation, which dictates that Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity. Because that isn’t the case in Figure 6-4, this balance sheet is incomplete. You fill in the remaining balance sheet numbers as you move through the chapter. Calculating depreciation Now that you see where fixed assets and depreciation show up in the balance sheet, you can go over the calculation of depreciation. Book III, Chapter 1 covers deprecation in detail. This section gives a more general discussion. Figure 6-4: A partial balance sheet that includes assets and liabilities. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 275 Here are the accounts related to fixed assets in Figure 6-4: $2,450,000 property, plant, and equipment – $685,000 accumulated depreciation = $1,765,000 cost less depreciation Accumulated depreciation is the total of all depreciation expense since the asset was purchased. Property, plant, and equipment is a common term for fixed assets. If all the assets were bought on the same day, and no depreciation had been expensed, the total property, plant, and equipment balance would be ($2,450,000 + $685,000 = $3,135,000). As you see in the earlier section “Dealing with fixed assets and depreciation,” there is no single method for calculating depreciation. So, the $685,000 is a combination of different depreciation methods. Some methods recognize depreciation evenly each year; others record more depreciation expense in the early years. For this chapter, assume that the $685,000 accumulated depreciation is a combination of different methods. Tacking on owners’ equity At this point, you’ve seen all the components that make up the total assets (refer to Figure 6-4). In the right column of the figure, you see two liability numbers — but no data for owners’ equity. You can use the fundamental accounting equation to calculate total equity. As explained in Book I, Chapter 1, the fundamental accounting equation looks like this: Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ equity or Assets – Liabilities = Owners’ equity Using the numbers from the balance sheet shown in Figure 6-4, you can calculate owners’ equity. $3,855,000 assets – $515,000 liabilities = $3,340,000 owners’ equity Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 276 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Completing the Balance Sheet with Debt If you own Company X, whose balance sheet is depicted in Figure 6-4, how should you raise the $3,340,000 in capital? You can debate this question until the cows come home, because no answer is right or best. The two basic sources of business capital are interest-bearing debt and equity (more precisely, owners’ equity). Company management decides what percent of capital is raised by using debt, and how much from equity. Many businesses use debt for part of their capital needs. This practice makes sense as long as the business doesn’t overextend its debt obligations. Going over the debt section of the balance sheet Figure 6-5 presents the complete balance sheet for Company X, including its debt and owners’ equity accounts. These are the final pieces of the balance sheet puzzle (if you start at the beginning of this chapter, this is what you’re working toward). Figure 6-5: Complete balance sheet of Company X. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 6: Coupling the Income Statement and Balance Sheet 277 The business has borrowed $500,000 on short-term notes payable (due in one year or less) and $1,000,000 on long-term notes payable (due in more than one year). Interest rates and other relevant details of debt contracts are disclosed in the footnotes to the financial statements. For example, debt covenants (conditions prescribed by the debt contract) may limit the amount of cash dividends the business can pay to its shareowners. (See Book V, Chapter 4 for a discussion of footnotes.) Tying in the new equity section Note that Figure 6-5 displays a more detailed equity section than the simple equity total presented in Figure 6-4. The following sections describe the sources of these details. Bringing up common stock The shareowners in Company X invested $750,000, for which they received 10,000 shares of capital stock. Typically, a footnote is necessary to fully explain the ownership structure of a business corporation. As a general rule, private business corporations don’t have to disclose owners — the owners of their capital stock. In contrast, public business corporations are subject to many disclosure rules regarding the stock ownership, stock options, and other stock-based compensation benefits of their officers and top-level managers. Stroll over to Chapter 5 for more on equity topics. Addressing retained earnings Retained earnings represent the sum of all net income earned by the company since inception, less all dividends paid to shareholders since the business started. For more, head over to Chapter 2. Over the years, the business in this scenario retained $1,090,000 of its yearly profits (see retained earnings in Figure 6-5). Two details aren’t explained in the retained earnings line item: ✓ You can’t determine how much of the cumulative total is from any single year’s net income. ✓ Retained earnings don’t reveal how much of the company’s $255,125 profit for the year just ended (see Figure 6-2) was distributed as a cash dividend to shareowners during the year just ended. One purpose of the statement of cash flows (explained in Book V, Chapter 2) is to report the cash dividends paid from net income to shareowners during the year. Book IV Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets 278 Book IV: Preparing Income Statements and Balance Sheets Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements To gauge how profitable an investment is likely to be, visit www.dummies.com/ extras/accountingaio for guidance on calculating present and future values. In this book… ✓ Use the balance sheet to assess and report the financial condition of a business, as measured by its assets, liabilities, and equity. ✓ Produce a cash flow statement and summarize changes in stockholders’ equity. Use the cash flow statement to explain how your business raised funds and how it used cash to generate profit. Use the stockholders’ equity report to reveal changes in earnings, dividends, and company ownership. ✓ Read and interpret financial statements to evaluate a business’s financial health. Assess your own business’s financial fitness and size up other businesses you’re thinking of doing business with. ✓ Make sense of explanatory notes and disclosures you’re likely to find in a corporation’s annual financial report. Reading this extra data may change your opinion about the company’s plans for growth. ✓ Pick out valuable pieces of financial information from a company’s report to its shareholders. You may find additional disclosures that clarify the company’s financial performance. Chapter 1 Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation In This Chapter ▶ Valuing assets in balance sheets ▶ Using the balance sheet to estimate the value of a business ▶ Considering methods to value an entire business T he balance sheet, also called the statement of financial condition, gives a snapshot of a business’s financial health at a point in time. It presents the assets of a business on the one hand and the liabilities and equity sources of the business on the other hand, reflecting the balance sheet equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity This chapter considers how to value (estimate the monetary worth of) the assets and liabilities in the balance sheet. Traditionally, a business values assets at historical cost. In this chapter, you find out how to use other methods to value assets and how to compute a valuation for an entire business. This chapter also explores the various uses for valuations and touches on the field of performing valuations as an occupation. You finish the chapter with a discussion of business valuations based on earnings and cash flow. Clarifying the Values of Assets in Balance Sheets The evidence is pretty strong that readers of financial reports aren’t entirely clear about the dollar amounts reported for assets in a balance sheet. Other than cash — the value of which is clear — the amounts reported for assets in a balance sheet aren’t at all obvious to non-accountants. 282 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Of course, accountants should be clear about the valuation of every asset reported in the balance sheet. In preparing a year-end balance sheet, an accountant should do a valuation check on every asset. Recent authoritative pronouncements on financial accounting standards have been moving in this direction. Accountants now must check at the end of the accounting year to see whether the value of any asset has been impaired (diminished in economic value to the business), and if so, write down (decrease) the book value of the asset. Book value is the cost of the asset less accumulated depreciation. Head over to Book III, Chapter 1 for more on depreciation. Considering options for balance sheet ­valuation If you need to value assets in the balance sheet, you may consider using historical cost, a value below cost, or a balance sheet value above cost: ✓ Historical cost: Most of the assets in a typical balance sheet are valued at historical cost (original cost). That value should be your starting point. ✓ Impairment: Accountants are required to write down impaired assets. The value of an impaired asset is typically below cost. ✓ Increase in market value of asset: In some cases, the value of the asset is above cost. Short-term investments in marketable securities held for sale may have an adjusted value above cost. The recorded values of nearly all other assets aren’t written up (increased) to recognize appreciation in the replacement value or market value of the asset. One reason is because assets you use in your business (buildings, equipment) aren’t held for sale. Also, these assets are likely to be used for many years. It’s not your intention to sell assets you use in your business. Looking at balance sheet valuation entries The dollar amounts reported for assets in a balance sheet are the amounts that were recorded in the original journal entries made when recording the asset transactions. These journal entries could have been recorded last week, last month, last year, or 20 years ago for some assets. Here are some examples: ✓ The balance of the asset accounts receivable is from amounts entered in the asset account when credit sales were recorded. These sales are recent, probably within the few weeks before the end of the year. ✓ The balance in the inventory asset account is from the costs of manufacturing or purchasing products. These costs could be from the last two or three months. Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation ✓ The costs of fixed assets reported in the property, plant, and equipment asset account in the balance sheet may go back five, ten, or more years — these economic resources are used for a long time. Connecting balance sheet values and expenses As you see earlier in this chapter, most balance sheet assets are valued at historical cost. The amount of cost used to value the asset depends partly on how expenses are treated. Merchandisers (retailers) purchase inventory and sell those goods to the public. Inventory is an asset. Accounting rules dictate that the cost of inventory should be the price paid for the asset plus any other costs incurred to prepare the goods for sale. Those other costs may include shipping, storage, and even costs to build display racks. The additional costs to prepare the good for sale are not immediately expensed. Instead, the costs are posted to inventory. Those costs become expenses when the inventory item is sold. At that point, all the costs are posted to cost of sales (or cost of goods sold). If you buy jeans for your retail shop, for example, the shipping costs you pay to get the jeans to your shop are considered part of inventory. If you need to build displays racks by the front window, those costs are part of inventory, too. (For more about inventory, see Book II, Chapter 2.) Another example to connect expenses with balance sheet values is the area of leasehold improvements — changes made to a leased space to meet a tenant’s needs. Instead of immediately expensing this amount, accountants capitalize the cost as an asset. The asset is usually depreciated over the remaining life of the lease. Assume you lease a factory building to a manufacturer. To accommodate truck shipments for the manufacturer/tenant, you need to widen the road approaching the factory. The spending on the road isn’t immediately expensed. Instead, the cost is posted to an asset account called leasehold improvements. (See Book V, Chapter 4 for more about lease-related financial disclosures.) Comparing two balance sheet valuations Consider two different valuations for the same asset, and how the difference impacts the balance sheet. Refer to the balance sheet in Figure 1-1. The business uses the straight-line depreciation method, by which an equal amount of depreciation is allocated to each year of a fixed asset’s estimated useful life (see Book III, Chapter 1 for more about depreciation methods). 283 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 284 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Figure 1-1: Balance sheet for a company that uses straight-line depreciation. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Assume the business had used an accelerated depreciation method for its fixed assets instead. In this case, $700,000 more in depreciation would be expensed, using the accelerated method. The change in depreciation method results in several changes in the balance sheet, as shown in Figure 1-2: Figure 1-2: Balance sheet for the same company, using accelerated depreciation. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation ✓ Depreciation expense over the years would be $700,000 higher. As a result, accumulated depreciation is $700,000 higher ($2,100,000 versus $1,400,000 in Figure 1-1). ✓ Using accelerated depreciation reduces the total value of assets. With that method, total assets are $7,300,000, compared with $8,000,000 total assets by using straight-line depreciation. ✓ The higher amounts of depreciation expense reduce cumulative net income by $700,000. Lower net income means that retained earnings is also lower ($1,500,000 versus $2,200,000 in Figure 1-1). Introducing Business Valuation The previous section shows how different valuation methods affect various items on the balance sheet, including inventory, leasehold improvements, and depreciation. You can also use different valuation methods to estimate the dollar worth of the entire company. The following sections present the uses of business valuations and explain the Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA) designation for anyone interested in making a career of performing business valuations. Grasping the practical applications of business valuations Accountants don’t perform business valuations simply to stick a dollar figure on a business. They do valuations for clients who need a general idea of how much money a business is worth in order to make well-informed decisions regarding that business. The following sections introduce a few of the more practical applications of business valuations. Negotiating a business purchase The most basic reason to place a dollar figure on a business is to help sellers or buyers determine what they think is a reasonable price for the business. Imagine if you were considering buying a pizza restaurant. You’d probably want to take a look at the ovens, equipment, and furniture — and consider how soon those fixed assets would need to be replaced. That analysis would help you determine what the business is truly worth to you, and how much you’d be willing to pay for it. 285 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 286 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Securing a bank loan Commercial loan officers work with loans to businesses. The loan officer is concerned about the company’s ability to generate enough earnings to make the interest payments on the loan and repay the principal amount borrowed. If a valuation based on earnings shows the company’s earnings are trending higher, the business is likely to be in a better position to make loan payments in the future. Say, for example, that your firm has a $2,000 monthly interest payment on a loan. The interest payment would be less of a burden if your earnings were $50,000 a month versus $5,000 a month. See the later section “Using future earnings and cash flow” to find out more about business valuations based on earnings. Explaining a company’s value to investors Businesses often raise money by selling shares of the business to investors who want to know the value of what they’re getting for their money. Unfortunately, the balance sheet may fail to reflect the true value of a ­particular asset or exclude the value of certain assets. For example, suppose a company purchases a time-saving machine that will eventually save it far more than the cost of that machine; the machine is worth more than the dollar amount the company paid for it. Assets that don’t even appear on the balance sheet are customers or clients. A business may have strong longterm relationships with certain clients that generate significant sales and earnings, but the value can’t be posted to the balance sheet as an asset. A business valuation takes this important asset into account. Considering a CVA designation The demand for business valuations and valuation analysis has resulted in a designation called a Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA). If you find business valuation fascinating and want to pursue it as a career, you may want to consider getting your CVA designation. The following sections show you how to get started and highlight other professions that do business valuations. Visiting the NACVA website The CVA designation is offered through the National Association of Certified Valuators and Analysts (NACVA), which you can find on the web at www. nacva.com. NACVA trains and certifies Certified Valuators and Analysts. The website explains that a primary requirement to become a CVA is to hold a valid license as a Certified Public Accountant. Understanding other professionals and valuations Many other professionals perform work that may be classified a business ­valuation, even though the work they produce isn’t considered a certified Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation valuation. When a business is subject to litigation, an attorney may perform some analysis on a firm’s balance sheet and income statement. If the owners of a firm are in a legal dispute about the value of each owner’s share of the business, for example, an attorney may perform an analysis. Appraisers perform value analysis of commercial property to estimate its current worth. Although other professionals may perform similar analysis, a CVA may be brought in to perform a certified valuation. Your accounting skills along with CVA training and designation ensure that you’re up to the task. Comparing Business Valuation Methods Just as you can use different valuations to estimate the dollar value of assets listed on the balance sheet, you can use different methods to perform business valuations. And different methods lead to different conclusions. Keep in mind, however, that the values calculated for a valuation may not be the amounts listed on the balance sheet. A valuation may use concepts inconsistent with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). See Chapter 1 for more on GAAP and other accounting standards. The question of whether determining the market value of a business is more of an art or a science is open to debate. One school of thought is that business valuation should be based on a complicated, multi-factor, formula-driven model — a scientific approach in which a business’s dollar value can be quantified. The opposite camp argues that in buying a business you’re buying a future stream of earnings, not merely a collection of assets. Their argument is that you’re just as well off using a simple method, but this simple method requires forecasting future earnings, which is notoriously difficult, not to mention unreliable. Both sides agree on one point: The profit performance track record of the business (reported in its recent income statements) and its present financial condition (reported in its latest balance sheet) are absolutely essential for the valuation of a business. The debate concerns how you should analyze and use that information. The following sections present two common approaches to performing business valuations. Replacing assets: Replacement value One measurement of a business’s worth in dollars is its book value — the cost of all assets less all accumulated depreciation. The following sections consider the cost of replacing assets used in a business. 287 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 288 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Pairing fixed asset accounts Most companies pair each fixed asset account with its own accumulated depreciation account, both of which are included in the company’s Chart of Accounts (see Book I, Chapter 2). Your office furniture asset account, for example, is paired with an account called accumulated depreciation- office furniture. The asset account less the accumulated depreciation equals the office furniture’s book value. Note: Accounting systems commonly give each fixed asset account its own accumulated depreciation account; those account titles usually include a dash like the one in accumulated depreciation- office furniture. Forecasting spending on fixed assets Suppose you’re in the market for a car repair shop. The big assets on the books are large pieces of equipment, such as hydraulic lifts for vehicles, and lots of other tools and equipment. All these items are listed as fixed assets on the balance sheet, each with its own accumulated depreciation account. A potential buyer most likely wants to buy the business and use it to generate earnings over many years. Big considerations include when each asset needs to be replaced and how much the replacement asset will cost. The prospective buyer can scan the fixed asset listing and make a judgment on each asset. Assets with a large amount of cost posted to accumulated depreciation probably need to be replaced soon. An analyst can estimate each asset’s replacement cost and the year of replacement. That list represents the required cash flow to maintain the assets needed to operate the business. The listing’s total dollar amount, plus the initial purchase price of the business, is the total investment required to buy and maintain the business. At that point, the investor can decide whether the business is worth the investment. Using future earnings and cash flow Although asset value provides a snapshot of a company’s current value, it doesn’t provide much insight into the company’s potential future value. Taking into account the replacement value of assets, as explained in the previous section, is one way to project the company’s future value. Another approach is to look at the company’s ability to produce earnings and cash flow into the future. Several tools are available for measuring a company’s potential profit. Book III, Chapter 6 explains the difference between cash basis accounting and the accrual basis. Nearly all companies use the accrual method, which requires that they recognize revenue when it’s earned rather than when they actually receive payment. The accrual method also posts expenses when they’re incurred instead of waiting until the bills are actually paid. As a result, the earnings using the accrual method differ from the cash method. Chapter 1: Presenting Financial Condition and Business Valuation 289 Earnings first Book V Your first approach to determine future value may be potential earnings. Take a look at the firm’s past financial performance. Next, consider how your industry knowledge could help increase sales. Mull over the firm’s reputation and customer list. Reporting on Your Financial Statements Maybe you’re considering buying an ad agency. The firm has a stable group of clients that have used the company for advertising for years. Your purchase price includes retention bonuses to motivate current key employees to stay with the company. Based on your long experience in the industry, you conclude that you can generate a 15 percent profit margin — or a 15-cent profit on every dollar in sales (see Book IV, Chapter 2 for more on profit ­measurements). Every investment has an opportunity cost associated with it. Opportunity cost is cash you invest in the purchase that you can’t use for some other purpose. Assume you invest $500,000 in a greeting card shop instead of investing the same amount in a convenience store. The profit earned by the convenience store owner is given up — that’s the opportunity cost of investing in the greeting card shop. Moving to cash flow Earnings are important, but a better measure of a company’s value may be the cash flow it generates. If you decide to invest in a company, you use cash. That cash has to come from somewhere. Consider these points: ✓ If you borrow funds, you stand to pay interest expense on the loan. ✓ Investors that issue stock expect a return on their investment, possibly in the form of a dividend. ✓ If you use cash from your existing company’s operations, you’ll have a tougher time meeting the cash flow needs of your business. A business needs to recover its cash investment as soon as possible. Given these considerations, a potential buyer may look at future cash flows of the new business to determine a company’s value. Assume you’re looking at a $600,000 investment in a bookstore. Based on your analysis, you determine that the business will generate $100,000 in cash inflow per year. The calculation you need to use is payback period: Payback period = Initial investment ÷ Cash inflow per period In this case, the payback period is 6 years ($600,000 ÷ $100,000). You can make a judgment as to whether or not 6 years is a reasonable period to 290 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements recover your original cash investment. See Book VIII, Chapter 4 for more about making purchase decisions. Putting a present value on cash flows Many analysts add a present value assumption into cash flow analysis because of inflation, which is broadly defined as a rise in the general level of prices for goods and services. In other words, today’s dollar is likely to buy you more than a dollar will buy you five years from today. Inflation impacts the value of the cash flows you receive from the business you purchase. The cash inflows should be adjusted to their present value (the current worth of a future sum of money). You should consider the ­present value of the cash flows you receive, because that amount represents the current purchasing power of those dollars. Your annual cash inflows in the prior section total $100,000 per year. Assume a 3 percent inflation rate. You’re interested in the present value of the payment received at the end of year 5. You need to multiply the cash inflow by a present value factor of 3 percent per period for 5 periods. You can find numerous versions of present value tables online. When you find a table, the period “n” is 5 (five years). After you find the n value for 5, scroll over to the 3 percent column. The table should show 0.863 (depending on rounding in your table). You can multiply this present value factor by the cash inflow amount: Present value of $100,000 at 3 percent, end of year 5 = $100,000 × 0.863 = $86,300 If you find a present value factor for all payments, you can compute the present value of all cash inflows. Use the sum of the cash inflows to judge the value of the business. Chapter 2 Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity In This Chapter ▶ Separating cash from profit ▶ Connecting the dots with the statement of cash flows ▶ Presenting cash flow by using the direct and indirect methods ▶ Summarizing changes in stockholders’ equity W hile accounting is all about the accrual method, which means revenue is recorded when it’s earned and expenses are recorded when they’re incurred, the missing piece of the puzzle is cash changing hands. For the users of financial statements to get a total picture of the health of the business, cash payments and receipts have to be reconciled with accrual transactions. You accomplish this reconciliation by preparing a statement of cash flows. In this chapter, you find out about the three sections of the statement of cash flows — operating, investing, and financing — and what types of accounting information are reported in each. This chapter also brings you up to speed on the two acceptable ways to prepare the statement of cash flows — by using the direct or indirect method — and concludes with a brief explanation of the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity. Understanding the Difference between Cash and Profit As explained in Book I, Chapter 4, the accrual method records revenue when it’s earned, regardless of whether money changes hands. You also record expenses when you incur them, regardless of whether they’re paid. Book I, Chapter 4 also introduces another accounting method — the cash method — which uses the criteria of cash changing hands to determine when revenue and expense transactions are recorded. The cash method is simply posting revenue and expenses by using your checkbook checks, debits, and deposits. 292 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Recognizing accounting transactions doesn’t hinge on cash being exchanged. As a result, you can expect to see a difference between a company’s cash balances and profit shown on the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2). Not all costs are immediately expenses, and until a cost is an expense, it doesn’t appear on the income statement. In the same way, not all cash receipts are immediately revenue. If a customer pays you in advance, you don’t recognize revenue until you provide the product or service to the client. This section first shows you how noncash transactions influence a company’s net income. It then illustrates the difference between costs and expenses. Seeing how noncash transactions affect profit The statement of cash flows homes in on the difference between two amounts: ✓ Ending balance in cash for the period ✓ Net income for the period Differences exist because net income factors in revenue earned but not yet collected from customers and expenses incurred but not yet paid — rather than reflecting only transactions involving cash. In other words, net income is computed by using the accrual method of accounting. The accrual method means that a business is likely to have a balance in accounts receivable (for credit sales) and accounts payable (for purchases it hasn’t yet paid for). For example, suppose that in June a company deposits $2,000 into its checking account and writes checks to pay bills for $1,800. If you look only at the cash flowing in and out of the business, the company spent $200 less than it brought in, so it shows a profit of $200. But what if, in June, the company also used a credit card it doesn’t intend to pay for until August to pay monthly bills in the amount of $1,000? Taking this transaction into account, the company actually spent more than it made, resulting in a loss of $800 ($2,000 in deposits less $2,800 in checks and credit card usage). Distinguishing costs from expenses When using the accrual method of accounting, one of the big distinctions you need to make and keep in mind is that costs aren’t the same as expenses. Take a look at the differences: ✓ Costs: A cost is the money the company uses to produce or buy something — money that’s not available to use anymore. Costs are a use of company cash, be it to purchase inventory, make investments, or pay back debt. Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity ✓ Expenses: Expenses are costs directly applied to revenue-producing activities during a financial period. When spending is applied (or matched) with revenue, the spending becomes an expense. Book I, Chapter 4 explains the matching principle for revenue and expenses. Suppose a company buys a shipment of aluminum for $25,000 cash in order to manufacture lawn mowers to sell to customers. The aluminum is a raw material, which appears on the balance sheet as an inventory account. When the company buys the aluminum, the price it pays, or promises to pay, is a cost. The company uses the aluminum to manufacture lawn mowers. When the lawnmower is sold, the cost of the aluminum used is reclassified as an expense (cost of goods sold). If the company uses half of the aluminum in production during the accounting period — and the lawn mowers produced are sold — the cost is $25,000, but the expense is only $12,500. The remaining $12,500 stays in inventory until it’s needed to produce the product and the product is sold. Check out Book II, Chapter 2 for more on inventory. The statement of cash flows is so important; it ties together the costs shown on the balance sheet with the expenses shown on the income statement. Realizing the Purpose of the Statement of Cash Flows The primary purpose of the statement of cash flows is to show a company’s cash sources and uses during the financial period. Although cash can come from many different sources, such as customer payments, loans, and sales of assets, uses of cash directly trace back to costs. This information is interesting to the external users of the company’s financial statements, who aren’t privy to the day-to-day operations of the business, because it provides a basis for understanding how wisely a company manages its cash. A company can be a real go-getter in the business world, but if cash is thrown around like chewing gum, the business may not be able to give prospective investors a reasonable return on their investment. Also, poor cash management may hinder a company’s ability to make timely payments of principal and interest on a loan. The statement of cash flows provides guidance for the following questions: ✓ Does the company have the ability to generate positive cash flow in the future? You don’t want to invest in a one-hit wonder. Viewing a current statement of cash flows gives a hint as to the company’s future prospects. Investors look for companies that can generate positive cash flow year after year. 293 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 294 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements ✓ Does the company have enough cash to make loan or dividend payments? If you’re a potential investor or lender for a corporation, letting the business use your money for free probably isn’t very smart. You want to check out the statement of cash flows to see how the business manages its money and gauge the probability of the company having enough cash to satisfy its loan obligations and pay dividends. ✓ Is the reason for the difference between net income and cash transactions indicative of a healthy business? All cash is not created equal. Cash a company brings in from gross receipts is a lot more exciting to a potential investor than cash the company has left over because it sold some assets. After all, the business can own only a finite number of assets, while the sky’s the limit for bringing in revenue from operations, assuming the business is managed well. You ferret out this information by reviewing the different sections of the statement of cash flows. Each section ties back to how accounting transactions affect the income statement and balance sheet. So you’re not looking at new information; instead, you’re looking at the same information presented in a different way. Walking through the Cash Flow Sections A statement of cash flows has the following three sections: ✓ Operating: The sources and uses of cash in this section come from dayto-day business operations: cash received from sales to customers, and cash paid out for payroll, inventory, and other common costs. ✓ Investing: The investing section is all about buying and selling assets. This section shows sources and uses of cash from investment purchases and sales. The section also includes purchases and sales of property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). ✓ Financing: This section involves raising money to run a business and paying it back. This section includes cash inflows from loans and cash outflows for principal payments. It also includes equity related items (the sale of company stock and payment of dividends). If some of these terms are unfamiliar to you, don’t worry. By the time you finish reading the rest of this section, you’ll be an old pro on cash flow. Most of a company’s cash transactions are in the operating section of the cash flow statement, because operations represent the common, day-to-day activity of the business. If you’re reviewing cash activity, find the investing and financing transactions first. When you finish, any cash activity that remains unassigned should be posted to the operating section. Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity Figuring cash operating results Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) has a guide to what shows up in the operating section: The operating section contains transactions not listed as investing or financing transactions. The following sections offer examples of operating sources and uses of cash. (See Book IV, Chapter 1 for details on GAAP.) Operating sources of cash Here are examples of operating sources of cash: ✓ Cash receipts from the sale of goods or services: This source is the cash that customers pay the company when the sale occurs. When the company collects cash from accounts receivable, that cash inflow is also from operations. For example, you go into Target and buy a new DVD player for $65. You fork over the cost of the purchase plus sales tax in cash. Target records this receipt as a source of cash. On the flip side, let’s say that on October 12, you go into an appliance warehouse to buy a new washer and dryer. The warehouse is holding a “90 days same as cash” promotion, which means that as long as you cough up the cash for the washer and dryer within 90 days, you pay no interest. On October 12, the appliance warehouse has no cash source from you, and it won’t have that source until you pay for your purchase on or before January 12. The appliance warehouse can’t record the sale as a source of cash until it receives your payment. ✓ Trading portfolio sales: Trading securities are assets a business purchases to make a profit in the short term. The intention is to trade the securities (buy and sell them). Assume a business has spare cash lying around that it doesn’t need access to in the immediate future. Rather than leaving the cash in the bank earning little or no interest, the company buys highly liquid (easily convertible to cash) stocks, bonds, or loans. The business tries to invest in something that won’t drop in value during the holding period. Then, when the company sells the investment, the cash it receives goes on the statement of cash flows in the operating section rather than investing. The key here for operating section placement is that the investment is short term. See Book IV, Chapter 3 for more information about short-term investments. ✓ Interest and dividends: If the company makes loans to other businesses or individuals, any interest income it receives on those loans goes in the operating section. An example is a loan to a shareholder who is also an employee and needs cash beyond what she’s receiving in her paycheck. This situation happens often in a closely held corporation. Also, some companies make loans to key vendors needing a short-term infusion of cash to keep their doors open. A company takes this step if it’s in the company’s best interest to keep an essential vendor in business. 295 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 296 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements After all, if you like to buy your widgets from Joe’s Widget Shop and Joe goes out of business, you’ll have to find another widget vendor, and maybe you won’t like working with that vendor (or paying its prices) as much as you liked working with Joe. As reported on the income statement, dividends are income paid to shareholders based on their proportional ownership of the corporation. For example, ABC Corp. owns 2,000 shares of XYZ, Inc. stock. ABC receives dividends from XYZ at $2 per share totaling $4,000 ($2 × 2,000 shares); this amount is posted to the operating section as a source of cash. You can find out more about the process behind declaring and paying dividends in Book IV, Chapter 5. Operating uses of cash Cash uses also show up in the operating section of a statement of cash flows. The cash outflows are kind of the flip side of the cash inflows. For example, accounts receivable from customers is an inflow, and accounts payable paid to vendors is an outflow. Here are the operating cash outflows you’re likely to encounter: ✓ Satisfying accounts payable: Accounts payable is the amount a company owes vendors for services and products purchased. When the original purchase takes place, no money changes hands between the customer and the supplier. Rather, the transaction contains a promise to pay within a certain amount of time. For example, suppose you order $500 of office supplies from Folders Office Supply, and Folders immediately invoices your company for $500. Your company doesn’t record this amount as a cash outlay, because Folders wasn’t paid yet; it merely has your promise to pay within 10 days (or 30 days, or whatever). This $500 becomes a cash outlay only after you sign and mail the payment check to Folders. ✓ Trading portfolio purchases: Just as sales of trading securities are a cash source, the amount of money the company pays to buy any trading security is a use of cash. No securities other than trading securities go in the operating section of the statement of cash flows. Again, the key here for operating section placement is that the investment is short term. See Book IV, Chapter 3 for more information about short-term investments. ✓ Payments for other business expenses: This category includes any cash outlays to buy inventory, pay employees, remit income taxes due, or pay any other suppliers (such as utility providers or the telephone company). You can find out more information about inventory purchases in Book II, Chapter 2. ✓ Interest payments: Any cash paid to lenders in the form of interest also goes in the operating section. The purpose or source of the loan doesn’t make any difference. So interest paid to a related party, such Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity as a shareholder, for an operating capital loan (cash made available for day-to-day business functions) is treated the same as interest paid to a vehicle financing company for the note on the company car. When a company borrows funds to operate, the cash inflow from the loan represents cash flow from financing. However, interest payments on the loan are an operating activity. Keep this difference in mind. The main thrust of the operating section of the statement of cash flows is to reconcile the cash versus accrual treatment of income statement items. Because paying dividends to shareholders isn’t a business expense, dividend payments don’t show up on the income statement, so they’re not an operating use of cash. Showing cash investing transactions Investing transactions involve the purchase and sale of noncurrent assets (see Book IV, Chapter 3). Noncurrent assets are assets the company anticipates owning for more than one year past the date of the balance sheet. Examples of noncurrent assets are long-term debt and equity investments; property, plant, and equipment; and intangible assets such as patents and copyrights. What exactly are debt and equity investments? ✓ Common stock is an example of an equity investment. Equity refers to ownership in a company. Suppose you buy AT&T common stock. As a shareholder, you’re an investor who gets paid back for the purchase of the stock only if you sell it to someone else. ✓ Bonds are debt investments. Corporations generally issue bonds to raise money for capital expenditures, operating expenses, and acquisitions. Because the investors are owed the principal amount they invest with the company, they’re company creditors. For example, a municipality sells bonds to the public for the purpose of financing a new hospital. Bondholders receive interest payments at the bond’s stated interest rate. When the bond matures, the company pays the bondholder the face amount of the bond. Investing sources of cash Investing transactions show up as sources of cash in the following ways: ✓ Long-term debt sales and collection: A company’s investments in debt may fall into three categories: loans, held-to-maturity debt investments, and available-for-sale debt portfolios. Here’s how they differ: • Loans are easy to understand; they’re merely money the company loans to others that won’t be repaid within 12 months of the balance sheet date. You know from your own personal debts (such 297 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 298 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements as car loans) that when you owe money, you periodically have to make payments on the principal portion of the loan. The same holds true with businesses. So any collection of principal on loans is a cash source for the company lending the money. • Held-to-maturity debt investments are those the company anticipates holding onto until the debt matures. For example, ABC Corp. buys five-year bonds issued by the city of Orlando to build a new sports arena. When the bonds mature, the cash proceeds go in the investing section. See Book IV, Chapter 4 for details on bonds. • Available-for-sale debt investments are one of those accounting topics defined by what they aren’t rather than what they are. They don’t fall into the held-to-maturity or trading category. However, as with the held-to-maturity investments, any cash the company receives from their sale or collection of principal at maturity reflects as a cash source in the investing section of the statement of cash flows. ✓ Sales of equity investments: If the company sells stock it owns in other corporations, the cash it receives is an investing source. So suppose your company owns 500 shares of ABC Corp. common stock, and you decide to sell all 500 shares. Any money you receive for the sale of your shares goes in the investing section. ✓ Sales of property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) and intangibles: The cash proceeds from any PP&E the corporation sells (such as cars, buildings, and equipment) is an investing source of cash. Ditto if the company sells an intangible asset such as a patent. (A patent provides licensing for inventions or other unique processes and designs.) Investing uses of cash Here are the potential uses of cash that appear in the investing section of the statement of cash flows: ✓ Loans and debt purchases: Any cash the company loans to another company is a cash outlay. So is any cash the company uses to buy bonds. ✓ Purchase of equity investments: This category includes any cash the company uses to buy stock in another corporation. ✓ Purchase of PP&E: If the business pays cash for any fixed asset acquisition or an intangible asset, this outlay of cash must appear in the investing section. Accounting for financing activities Financing activities show transactions with lenders such as long-term liabilities (paying or securing loans beyond a period of 12 months from the balance sheet date) and equity items (the sale of company stock and payment of dividends). Sound familiar from the investing section? Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity The one main financing cash source is cash proceeds if a business issues its own stock or debt. For example, ABC Corp. sells $3,000 of its own stock to XYZ, Inc. The cash ABC receives from XYZ for this transaction is a financing source of cash on ABC’s statement of cash flows. Short-term and long-term debt the company issues is included in the financing section. How long the creditor plans to hold the debt determines whether it’s recorded on the creditor’s books as short- or long-term debt. Now, here are the uses of cash that would appear in the financing section of the statement of cash flows: ✓ Treasury stock transactions: Treasury stocks are shares of corporate stock that were previously sold and have since been bought back by the issuing corporation. The use of the cash is to buy back stock from shareholders. See Book IV, Chapter 5 for more information about treasury stock. ✓ Cash dividend payments: Cash dividends are earnings paid to shareholders based on the number of shares they own. Dividends can also come in the form of stock dividends, which don’t involve cash changing hands. So remember, only cash dividends go in the financing section. You find more about cash and stock dividends, plus some info on stock splits (also a noncash transaction), in Book IV, Chapter 5. ✓ Paying back debt: Any principal payment a company makes on bonds or loans is a financing activity. Recognizing Methods for Preparing the Statement of Cash Flows Two methods are available to prepare a statement of cash flows: the indirect and direct methods. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB; see Book IV, Chapter 1) prefers the direct method, while many businesses prefer the indirect method. Regardless of which method you use, the bottom-line cash balance is the same, and it has to equal the amount of cash you show on the balance sheet. The last step in compiling the statement of cash flows is to verify that the ending balance in the cash flow statement equals the ending balance in the cash account on the balance sheet. If they don’t agree, there must be a mistake or missing cash transactions in the cash flow statement. This is the process used for both the direct and indirect method. 299 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 300 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements The following figures show you what the statement of cash flows looks like when you use both the direct and indirect methods of preparation. Figure 2-1 is the statement of cash flows using the direct method, and Figure 2-2 is the statement of cash flows using the indirect method. As you look at both, note that the cash balance on 12/31/2015 is the same for both methods. Figure 2-1: A direct method statement of cash flows. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity 301 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements Figure 2-2: An indirect method statement of cash flows. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Using the direct method The direct method of preparing the statement of cash flows shows the net cash from operating activities. This section shows all operating cash receipts and payments. Some examples of cash receipts you use for the direct method are cash collected from customers, as well as interest and dividends the company receives. Examples of cash payments are cash paid to employees and other suppliers and interest paid on notes payable or other loans (see Book IV, Chapter 4). Here are three key facts to remember about the direct method: ✓ You present cash received and paid — not net income or loss as shown on the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2). ✓ Any differences between the direct versus the indirect method are located in the operating section of the statement of cash flows. The financing and investing sections are the same regardless of which method you use. 302 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements ✓ The FASB prefers the direct method because it believes the direct method gives the users of the financial statements a more complete picture of the health of the business. Starting indirectly with net income When you use the indirect method of preparing the statement of cash flows, the operating section starts with net income from the income statement. You then adjust net income for any noncash items hitting the income statement. One typical adjustment is for depreciation, which is a noncash transaction (see Book III, Chapter 1). Other common items requiring adjustment are gains and losses from the sale of assets (see Book IV, Chapter 2). This is because the gains or losses shown on the income statement for the sale will rarely if ever equal the cash a company receives. In other words, gain or loss is based on the difference between the asset’s net book value, which is cost less accumulated depreciation, and the amount the item sold for — not how much cash the buyer hands over to the seller. Assume a business has a machine it no longer uses. Because it no longer needs the machine, the business sells it to another company for $1,500. The cash received is $1,500, but what about gain or loss on disposal? Consider these facts: ✓ The company originally paid $3,000 to purchase and install the machine. ✓ The asset was depreciated, meaning that the asset’s cost was gradually posted to depreciation expense over the machine’s useful life. The total amount depreciated over time (accumulated depreciation) was $2,000. Check out Book III, Chapter 1 for more on depreciation. ✓ Book value for the machine on the date of sale was $1,000 ($3,000 cost – $2,000 accumulated depreciation). ✓ The company debits (increases) cash for $1,500 and debits (reduces) accumulated depreciation for $2,000. When the asset is sold, the accumulated depreciation account is adjusted to zero. Debits total $3,500. ✓ The asset is credited (reduced) by $3,000, which is the original cost. ✓ Gain on disposal is a credit for $500, which is the difference between $3,500 total debit and the $3,000 credit. After the gain is posted, total debits and credits both equal $3,500. Chapter 2: Laying Out Cash Flows and Changes in Equity You see that the cash received ($1,500) differs from the gain on disposal ($500). These are the types of transactions that are reconciled in the statement of cash flows. The net income change ($500 gain) doesn’t match the $1,500 cash inflow. Book IV, Chapter 2 goes into more detail in gains and losses. Interpreting the Statement of Cash Flows Users of the statement of cash flows are primarily interested in whether the company has positive cash flows from operations. As a general rule, a company should be covering its costs by the cash it brings in from the day-to-day running of the business, rather than from borrowed funds. A potential investor or creditor wants to see that cash the company brings in through operations exceeds any cash brought in by selling assets or borrowing money. This is because selling assets or borrowing money can never be construed as a continuing event, such as bringing in cash from selling goods or services. Book IV, Chapter 2 explains this concept in more detail. A company may issue stock or bonds in order to expand its operations. On a nonrecurring basis, that situation can be okay because successful expansion is a good thing for investors and creditors. Successful expansion leads to more sales and higher overall profits. However, unless cash from operations exceeds cash from other sources with some consistency, a company will be paying back debt with either more debt or equity being issued, which is decidedly not a good thing. Here’s how investors and lenders use the statement of cash flows: ✓ Investor: An investor wants to make sure the corporation has enough cash flow to pay an adequate return on investment. In other words, can the investor anticipate getting a cash dividend each year? Also important is using the statement of cash flows to evaluate how well the company is managing its cash because investors may eventually sell their shares of stock. If the company mismanages its cash to such a point that it goes out of business, there won’t be any buyers for the company’s stock — the stock may be worthless. ✓ Creditor: The creditor also has a vested interest in making sure the company has sound cash management. After all, in addition to the interest expense the debtor pays for the use of the loan, the creditor wants to make sure it also gets paid back the principal portion of the loan. It’s never a good sign if a business is paying back debt by assuming more debt or issuing more equity. 303 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 304 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Looking Quickly at the Statement of Changes in Stockholders Equity Larger businesses generally have more complicated ownership structures than smaller and medium-sized companies. Larger businesses are most often organized as a corporation in contrast to other forms of legal structures. (See Book VI, Chapter 2 for more about the legal structure of a business.) Corporations can issue more than one class of stock shares, and many do. One class, preferred stock, has certain perks that the other class, called common stock, doesn’t. Also, a corporation may have both voting and non-voting stock shares. And corporations can buy back their own stock shares (treasury stock) for a variety of reasons. Book IV, Chapter 5 addresses these transactions. The point is that many businesses, especially larger public companies, engage in activities that change their owners’ equity components. These owners’ equity activities tend to get lost from view in a comparative balance sheet and in the statement of cash flows. Yet the activities can be important. Therefore, the business prepares a separate statement of changes in stockholders’ equity covering the same period as its income statements. The statement of changes in stockholders’ equity is where you find certain technical gains and losses that increase or decrease owners’ equity but that are not reported in the income statement. You have to read this summary of changes in the owners’ equity accounts to find out whether the business had any such gains or losses. Look in a column headed comprehensive income for these gains and losses, which are very technical. The general format of the statement of changes in stockholders’ equity includes columns for each class of stock, additional paid in capital, treasury stock, retained earnings, and the comprehensive income element of owners’ equity. Professional stock analysts have to pore over these statements. Average financial report readers probably quickly turn the page when they see this statement. But it’s worth a quick glance if nothing else. Many financial reports include a statement of changes in stockholders’ equity in addition to their three primary financial statements. It’s not really a full-fledged financial statement. Rather, it serves as a columnar footnote for the various owners’ equity accounts in the balance sheet. For more about changes in owners’ equity, see Book IV, Chapter 5. Chapter 3 Analyzing Financial Statements In This Chapter ▶ Evaluating a business’s financial health ▶ Categorizing business transactions ▶ Connecting revenue and expenses with their assets and liabilities ▶ Focusing on profitability and activity measures ▶ Preparing vertical and horizontal analyses S takeholders in a business are naturally curious about the financial condition of a company, as reported in its financial statements. Stakeholders include everyone who may be affected by the financial success or failure of the business — owners, investors, lenders, the CEO and other executives, managers, employees, and even vendors. This chapter offers practical tips to help investors, lenders, or anyone who has a financial stake in a business glean important insights from financial statements. These tips also help anyone else with an interest in the financial condition of a business. Judging Solvency and Liquidity Solvency and liquidity both measure the ability of an entity to pay its debts. Solvency has a long-term focus, while liquidity addresses short-term payments. Solvency refers to the ability of a business to pay its liabilities on time. Solvency measures whether or not a company is viable — a business that can generate sufficient cash flow to operate over the long-term (multiple years). Liquidity, on the other hand, refers to the ability of a business to keep its cash balance and cash flows at adequate levels so that operations aren’t disrupted 306 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements by cash shortfalls. When considering liquidity, the focus is on the next six months or the next year. For more on this important topic, check out Cash Flow For Dummies by Tage C. Tracy and John A. Tracy (Wiley). Understanding the risks of late payments Delays in paying liabilities on time can cause serious problems for a business. Customers may shy away from doing business with a company that has financial problems. Vendors may not be willing to sell the company product because of the risk of not being paid. Customers and vendors may hear about a company’s financial issues through media reports (newspaper, TV, web). In extreme cases, a business can be thrown into involuntary bankruptcy. In a bankruptcy, a court-appointed trustee may take substantial control over the business and its decisions about debt payment. Even the threat of bankruptcy can cause serious disruptions in the normal operations of a business. Recognizing current assets and liabilities Short-term, or current, assets include: ✓ Cash ✓ Marketable securities that can be immediately converted into cash ✓ Assets expected to be converted into cash within one year The operating cycle is the process of converting current assets (largely inventory and accounts receivable) into cash. The term operating cycle refers to the repetitive process of putting cash into inventory, holding products in inventory until they’re sold, selling products on credit (which generates accounts receivable), and collecting the receivables in cash. In other words, the operating cycle is the “from cash — through inventory and accounts receivable — back to cash” sequence. The operating cycles of businesses vary from a few weeks to several months, depending on how long inventory is held before being sold and how long it takes to collect cash from sales made on credit. Short-term, or current, liabilities include non-interest-bearing liabilities that arise from the operating (sales and expense) activities of the business. A typical business keeps many accounts for these liabilities — a separate account for each vendor, for instance. In an external balance sheet you usually find only three or four operating liabilities. It’s assumed that the reader knows Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements that these operating liabilities don’t bear interest (unless the liability is seriously overdue and the creditor has started charging interest because of the delay in paying the liability). The balance sheet example shown in Figure 3-1 discloses three operating liabilities: accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, and income tax payable. The terminology for these short-term operating liabilities varies from business to business. Figure 3-1: Typical comparative balance sheet for a product business at the end of its two most recent years (in vertical, or portrait format). ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 307 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 308 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements In addition to operating liabilities, interest-bearing notes payable that have maturity dates one year or less from the balance sheet date are included in the current liabilities section (see short-term notes payable in Figure 3-1). The current liabilities section may also include certain other liabilities that must be paid in the short run (which are too varied and technical to discuss here). Notice the following points in Figure 3-1 (dollar amounts refer to year-end 2015): ✓ The first four asset accounts (cash, accounts receivable, inventory, and prepaid expenses) are added to give the $8,815,000 subtotal for current assets. ✓ The first four liability accounts (accounts payable, accrued expenses payable, income tax payable, and short-term notes payable) are added to give the $4.03 million subtotal for current liabilities. ✓ The total interest-bearing debt of the business is separated between $2.25 million in short-term notes payable (those due in one year or sooner) and $4 million in long-term notes payable (those due after one year). Brushing up on current and quick ratios If current liabilities become too high relative to current assets — which constitute the first line of defense for paying current liabilities — managers should move quickly to resolve the problem. A perceived shortage of current assets relative to current liabilities could sound the sirens in the minds of the company’s creditors and owners. The current and quick ratios measure this risk. Making a judgment about the ratios you compute depends on your industry. However, a current ratio of at least 1.0 is considered a minimum expectation for company liquidity (see the earlier section on liquidity). At that ratio, you have at least $1 in current assets to pay each dollar of current liabilities. Business managers know that acceptable ratios also depend on general practices in the industry for short-term borrowing. Some businesses do well with current ratios less than 2.0 and quick ratios less than 1.0; so take these benchmarks with a grain of salt. Lower ratios don’t necessarily mean that the business won’t be able to pay its short-term (current) liabilities on time. Applying the current ratio Current assets are the first source of money to pay current liabilities when these liabilities come due. Remember that current assets consist of cash and assets that will be converted into cash in the short run. Ideally, a company will use current assets as a payment source, rather than additional borrowing or other financing. Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements To size up current assets against total current liabilities, the current ratio is calculated. Using information from the company’s balance sheet (refer to Figure 3-1), you compute its year-end 2015 current ratio as follows: $8,815,000 current assets ÷ $4,030,000 current liabilities = 2.2 current ratio Generally, businesses don’t provide their current ratio on the face of their balance sheets or in the footnotes to their financial statements — they leave it to the reader to calculate this number. On the other hand, many businesses present a financial highlights section in their financial report, which often includes several financial ratios. Moving to the quick ratio The quick ratio is more restrictive than the current ratio. Only cash and assets that can be immediately converted into cash are included, which excludes inventory. In some businesses, it may take many months to sell inventory. Here is the adjusted asset number you use for the quick ratio (refer to Figure 3-1): $8,815,000 current assets – $3,450,000 inventory = $5,365,000 assets for quick ratio You compute the quick ratio as follows: $5,365,000 assets for quick ratio ÷ $4,030,000 current liabilities = 1.3 quick ratio Wrapping up with working capital The same data used to calculate current and quick ratios is used to compute working capital. Here’s the formula: Working capital = Current assets – Current liabilities A current ratio of at least 1.0 is considered reasonable for liquidity purposes. That’s because the ratio displays at least $1 in current assets for each dollar of current liabilities. Assume that current assets and current liabilities each total $1,500,000. The current ratio is 1.0 ($1,500,000 ÷ $1,500,000). Put the same data in the working capital formula. Working capital would be zero ($1,500,000 less $1,500,000). Negative working capital would mean that current assets are less than current liabilities. So, the minimum expectation of 1.0 for a current ratio is the same as a $0 working capital calculation. 309 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 310 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Understanding That Transactions Drive the Balance Sheet A balance sheet is a snapshot of the financial condition of a business at an instant in time. If the fiscal, or accounting, year of a business ends on December 31, its balance sheet is prepared at the close of business at midnight December 31. (A company should end its fiscal year at the close of its natural business year or at the close of a calendar quarter — September 30, for example.) This freeze-frame nature of a balance sheet may make it appear that a balance sheet is static. Nothing is further from the truth. A business doesn’t shut down to prepare its balance sheet. The financial condition of a business is in constant motion because the activities of the business go on nonstop. Analyzing three types of balance sheet transactions Transactions change the makeup of a company’s balance sheet — that is, its assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity. The transactions of a business fall into three basic types. Notice that these three types match up with the three categories of cash flow in the statement of cash flows (see Chapter 2): ✓ Operating activities: This category refers to making sales and incurring expenses, and also includes accompanying transactions that relate to the recording of sales and expenses. For example, a business records sales revenue when sales are made on credit, and then, later, records cash collections from customers. The transaction of collecting cash is the indispensable follow-up to making the sale on credit. For another example, a business purchases products that are placed in its inventory (its stock of products awaiting sale), at which time it records an entry for the purchase. The expense (the cost of goods sold) isn’t recorded until the products are actually sold to customers. Keep in mind that the term operating activities includes the associated transactions that precede or are subsequent to the recording of sales and expense transactions. ✓ Investing activities: This term refers to making investments in assets and (eventually) disposing of the assets when the business no longer needs them. The primary examples of investing activities for businesses that sell products and services are capital expenditures. A capital expenditure is an amount spent to modernize, expand, or replace the long-term operating assets of a business. A business may also invest in financial assets, such as bonds and stocks or other types of debt and equity instruments. Purchases and sales of financial assets are also included in this category of transactions. ✓ Financing activities: These activities include securing money from debt and equity sources of capital, returning capital to these sources, and Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements distributing profit to owners. For instance, when a business pays cash dividends to its stockholders the distribution is treated as a financing transaction. The decision whether or not to distribute some of its profit depends on whether the earnings generated are needed to operate the business. If the company distributes earnings by paying a dividend, the equity section of the balance sheet is reduced. (See Book VIII, Chapter 1 for more about accounting for financing activities.) Reviewing changes in balance sheet accounts Figure 3-2 presents a summary of changes in assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity during the year. Notice the middle three columns in Figure 3-2, for each of the three basic types of business transactions discussed in the prior section. One column is for changes caused by its revenue and expenses and their connected transactions during the year, which collectively are called operating activities. The second column is for changes caused by its investing activities during the year. The third column is for the changes caused by its financing activities. Figure 3-2: Summary of changes in assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity during the year according to basic types of transactions. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 311 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 312 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Note: Figure 3-2 doesn’t include subtotals for current assets and liabilities. (The formal balance sheet for this business is presented in Figure 3-1.) The summary of changes in assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity isn’t a required financial statement for external users (stakeholders). The purpose of Figure 3-2 is to demonstrate how the three major types of transactions change the assets, liabilities, and owners’ equity accounts during the year. Tying in profit Figure 3-2 lists a $1.69 million increase in owners’ equity–retained earnings account. See the operating activities column. The increase represents net income earned for the year. The operating activities column in Figure 3-2 is worth lingering over for a few moments because the financial outcomes of making profit appear in this column. Most people see a profit number, such as the $1.69 million in this example, and stop thinking any further about the financial outcomes of making the profit. This is like going to a movie because you like its title, but you don’t know anything about the plot and characters. You probably noticed that the $1,515,000 increase in cash in this column differs from the $1,690,000 net income figure for the year. The cash effect of making profit (which includes the associated transactions connected with sales and expenses) almost always differs from the net income amount for the year. Book V, Chapter 2 explains this difference. Managing balance sheet activity The summary of changes presented in Figure 3-2 gives a sense of the b ­ alance sheet in motion, or how the business got from the start of the year to the end of the year. Having a good sense of how transactions propel the balance sheet is important. A summary of balance sheet changes, such as those shown in Figure 3-2, can be helpful to business managers who plan and c ­ ontrol changes in the assets and liabilities of the business. They need a clear understanding of how the three basic types of transactions change assets and liabilities. Also, Figure 3-2 provides a useful platform for the statement of cash flows explained in Book V, Chapter 2. Measuring Profitability In addition to having a handle on how well a company covers its current debt with current assets, just about all financial statement users want to be able to evaluate the relative robustness of a company’s income over a series of years or financial periods. Looking at a company’s performance over a long period of time is called trend analysis. Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements This section explains how trend analysis works and why it’s so important when evaluating profitability. It then moves on to explain two profitability measures: return on investment and return on equity. Understanding trend analysis A single profitability measure standing alone doesn’t really tell you much about a company or how it’s performing compared to its competitors. This is true for two reasons: ✓ The company may have had an exceptionally good or bad year. Unless a company’s performance is static from year to year, looking at only one year of financial statement results is misleading. The statement user sees an inaccurate vision of the company’s performance over time. Consider a personal example. Suppose you win $50,000 in the lottery this year, making your total income (after adding in your earnings from your part-time job) $62,000. The next year and the year after that, you don’t have any winning lottery tickets (darn it!), and your average income is $33,000 per year. Clearly, looking at your income for only the year you won the lottery gives an inaccurate indication of your typical annual income, because that year’s income includes an unusual, nonrepeating event. ✓ Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), companies are allowed to use various methods to estimate some expenses. If a financial statement user is trying to compare Company A to Company B by applying a single set of profitability ratios, he’s not going to see the whole picture. For example, two equally profitable companies using different inventory valuation methods (see Book VIII, Chapter 2) may report big differences in net income. The same holds true for depreciation of long-term assets, discussed in Book III, Chapter 1. Different options are also available for booking an estimate for bad debt expense, which is the money the company reckons it won’t be able to collect from credit customers (see Book III, Chapter 6). Many more differences may arise by using allowable GAAP methods, but you get the picture. Trend analysis gives much more meaningful information to the financial statement user because differences in accounting methods tend to smooth out over time. For example, although the method a company uses for depreciation affects the amount of depreciation expense by year, it never affects original cost. In other words, an asset costing $1,000 can never be depreciated for more than $1,000. After the asset is fully depreciated, total depreciation expense is the same, regardless of the method used. Analyzing ratios over a period of several years should be somewhat consistent, which permits the financial statement user to do some useful trend comparisons. 313 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 314 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Using trend analysis means looking at profitability ratios over a number of years. Doing so is usually more helpful to the financial statement user than any single ratio is because everything is relative. Seeing how profitability ratios go up and down (when comparing current performance to past performance and when comparing the company with other companies in the same industry) is more meaningful than just looking at one stand-alone ratio. Most investors consider at least five years — sometimes up to ten. Focusing on return on investment Return on investment (ROI) is a measuring tool investors use to see how well their investment in a particular company is faring — and to help them make that important decision to sell a stock and move on or to stick with it. Potential investors also use ROI when trying to make a decision among different companies in which to plunk their spare cash. Investors want to see how well company management is using the company assets to make money. This information gives the investor some idea of the competency of management and the relative profitability of a business when compared to others the investor is considering. Investors can calculate ROI, which is expressed as a percentage, a few ­different ways. All the methods involve using some form of comparing income to assets. Here are two common methods: ✓ Net income divided by average total assets: Net income (see Book VIII, Chapter 1) is the bottom-line total of what’s left over after you deduct all business expenses and losses from all revenue and gains for the same financial period. Assets are all the resources a company owns. So if a company has net income of $100,000 and average total assets of $2,700,000, its ROI is 3.7 percent ($100,000 ÷ $2,700,000). To determine the average of any account, add the account balance at the beginning of the financial period to the ending balance and divide that figure by two. So, if total liabilities are $50,000 on January 1 and $75,000 on December 31, average total liabilities is $125,000 ÷ 2 = $62,500. ✓ Operating income divided by average operating assets: This form of ROI calculation starts with income before income taxes and interest and divides it by average operating assets, which are long-lived assets such as property, plant, and equipment. So if a company’s operating income is $82,000 and its average operating assets are $1,200,000, ROI using this method is 6.83 percent ($82,000 ÷ $1,200,000). In real life, it doesn’t make any difference which method an investor uses. As long as the chosen method is used consistently, trend analysis using any ROI method will give the investor a significant resource for making a decision as to which company to invest in. Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements Homing in on return on equity As explained in the prior section, return on investment measures how well you generate profits from company assets. Return on equity (ROE) measures the profit earned for each dollar invested in a company’s stock. You figure it by dividing net income by average owners’ equity (see Book IV, Chapter 5), which is what’s left over in the business after all liabilities are subtracted from all assets. The higher the ROE ratio, the more efficient management is at utilizing its equity base. This measurement is important to stockholders and potential investors because it compares earnings to owners’ investments (equity). Because this calculation takes into account retained earnings — the company’s cumulative net income less dividends — it gives the investors much-needed data as to how effectively their capital is being used. Having net income grow in relation to increases in equity presents a picture of a well-run business. Take a walk through a quick calculation. If a company’s net income is $35,000 and the average owners’ equity is $250,000, ROE is 14 percent ($35,000 ÷ $250,000). Once again, to make wise investment decisions, users of this information look at ROE as it trends over a series of years and compare it to the ROE of other companies. Exploring Activity Measures This section discusses activity measures that quantify the relationship between a company’s assets and sales. Accounting textbooks usually mention a few activity measures. This section discusses the ones most commonly used: those that measure accounts receivable and inventory activity. For many companies, accounts receivable and inventory represent the largest account balances in the balance sheet. As a result, performing analysis on these accounts is an important indicator of financial performance. Ratio analysis that studies activity shows you how well a company is using its assets to make money. This calculation is an expansion of the return on investment (ROI) measurement. The premise is that how well a company uses its assets to generate revenue goes a long way toward telling the tale of its overall profitability. Presumably, a business that’s effectively and efficiently operated, which activity measures show, will generally be more successful than its less effective and efficient competitors. Asset turnover analysis shows how well you use assets to generate sales. A higher ratio means more sales per dollar of assets, which is the goal. In other 315 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 316 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements words, efficiently turning over assets indicates a well-run business. The basic formula to calculate asset turnover is this: Asset turnover = Sales ÷ Average assets The two most important current assets for the majority of businesses are accounts receivable and inventory. The following sections explain each turnover ratio. Accounts receivable turnover Accounts receivable turnover shows the average number of times accounts receivable is turned over during the financial period. In this case, turned over means how often a receivable is posted to the books and then received in cash. Here’s the formula: Accounts receivable turnover = Net credit sales ÷ Average accounts receivable Net credit sales represent sales made on credit, less any sales returns and discounts. See Book I, Chapter 3 for more detail on receivables. Average accounts receivable is simply the beginning receivable balance for the period plus the ending receivable balance divided by two. See “Focusing on return on investment,” earlier in this chapter for instructions on how to compute an average balance. The sooner a company collects receivables from its customers, the sooner the cash is available to take care of the needs of the business. This turnover rate is a big deal, because the more cash the company brings in from operations, the less it has to borrow for timely payment of its liabilities. Here’s an example of how to figure accounts receivable turnover: Village Shipping has net credit sales of $35,000 for the year. Accounts receivable (A/R) was $2,500 at January 1 and $1,500 at December 31. The average A/R is ($2,500 + $1,500) ÷ 2 = $2,000. The accounts receivable turnover is $35,000 ÷ $2,000 = 17.5, or 17.5 times. Another often-used accounts receivable activity measure is the average collection period for accounts receivable, also called day’s sales outstanding. This measure calculates the average number of days that credit sales remain in accounts receivable — a valuable aid in helping companies develop credit and collection policies. The average collection period for accounts receivable is figured by dividing accounts receivable as of the last day of the financial period by the average day’s sales (all sales in the financial period divided by Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements 365 days or 366 days in a leap year). This calculation assumes that a business is open each day of the year. It may not be realistic, but it allows the formula to be compared among businesses. Inventory turnover Inventory turnover shows how efficiently the company is handling inventory management and replenishment. The less inventory a company keeps on hand, the lower the costs are to store and hold it, thus lowering the cost of inventory having to be financed with debt or by selling equity to investors. However, keep in mind that running out of inventory hurts business. Low inventory levels can cause lost sales and late deliveries and perhaps strain the company’s relationship with its customers. Also, running low on inventory may cause the company to panic and buy the same inventory for a higher price to get it right now. Too much of that sort of mismanagement can play havoc with the bottom line. Here’s the formula for inventory turnover: Inventory turnover = Cost of goods sold ÷ Average inventory value You calculate average inventory the same way you compute the average for accounts receivable in the prior section. If cost of goods sold are $35,000, and average inventory is $8,500, inventory turnover is $35,000 ÷ $8,500 = 4.12, or 4.12 times. Comparing Horizontal and Vertical Analysis A good way to do some ratio and trend analysis work is to prepare both horizontal and vertical analyses of the income statement. Both analyses involve comparing income statement accounts to each other in dollars and in percentages. Understanding horizontal and vertical analysis is essential for managerial accounting, because these types of analyses are useful to internal users of the financial statements (such as company management), as well as to external users. If analysis reveals any unexpected differences in income statement accounts, management and accounting staff at the company should isolate the reasons and take action to fix the problem(s). 317 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 318 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements You can do the same types of analyses for balance sheet accounts. For a horizontal analysis, you compare like accounts to each other over periods of time — for example, accounts receivable (A/R) in 2014 to A/R in 2015. To prepare a vertical analysis, you select an account of interest (comparable to total revenue) and express other balance sheet accounts as a percentage. For example, you may show merchandise inventory or accounts receivable as a percentage of total assets. Using horizontal analysis Horizontal analysis compares account balances and ratios over different time periods. For example, you compare a company’s sales in 2014 to its sales in 2015. Figure 3-3 is an example of how to prepare a horizontal analysis for two years. For useful trend analysis, you need to use more years (most investors use five), but this example gives you all the info you need to prepare a horizontal analysis for an unlimited number of years. Figure 3-3: Income statement horizontal analysis for 2014 and 2015. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The analysis computes the percentage change in each income statement account at the far right. The first number you might consider is the change in profit. Net income declined by 42.29 percent. Consider these two numbers and how they contributed to the decline: ✓ Repairs expense increased by 39.76 percent ✓ Sales declined by 5 percent Chapter 3: Analyzing Financial Statements To isolate the reason for the net income decline, look at the change in total dollars, as well as the percentage change. The repair expense is the largest percentage change — an increase in costs. But note that the dollar amount of change is only $1,650 ($4,150 to $5,800). On the other hand, the sales decline was $25,000 ($500,000 to $475,000). The decrease in sales has a bigger impact on the net income decline, when dollars are considered. Implementing vertical analysis Vertical analysis restates each amount in the income statement as a percentage of sales. This analysis gives the company a heads up if cost of goods sold or any other expense appears to be too high when compared to sales. Reviewing these comparisons allows management and accounting staff at the company to isolate the reasons and take action to fix the problem(s). Figure 3-4 is an example of how to prepare a vertical analysis for two years. As with the horizontal analysis, you need to use more years for any meaningful trend analysis. This figure compares the difference in accounts from 2014 to 2015, showing each account as a percentage of sales for each year listed. Figure 3-4: Income statement vertical analysis for 2014 and 2015. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. At the bottom of the analysis, note that net income, as a percentage of sales, declined by 2.62 percentage points (6.67 percent to 4.05 percent). As a dollar amount, net income declined by $14,096 ($33,333 to $19,237). As mentioned in the prior section, management should consider both the percentage change and the dollar amount change. 319 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 320 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Using Common Size Financial Statements One way to visually zero in on potential problems and missteps taking place within a business is to prepare and study common size financial statements. Common size financial statements get rid of the dollars and cents, reflecting account balances as percentages. For example, with the vertical analysis of income statement items, all income statement items are shown as a dollar amount and percentage of total sales. With a common size income statement, you omit any references to the dollar figures. The big deal about common size financial statements is that the distraction of the dollar amounts is taken away. Cleaning up the statements this way allows the user to compare different companies in the same industry in a more equitable manner. For example, just because one company has higher total revenue than another doesn’t necessarily make it a better company to invest in or loan money to. Showing accounts as a percentage of another account of interest rather than a dollar amount really allows you to see the big picture of how the business is doing rather than obsessing about the difference in dollar amounts. Chapter 4 Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures In This Chapter ▶ Touching on corporate governance ▶ Studying the characteristics of a corporation ▶ Finding out more about a company by reading its notes and disclosures ▶ Figuring out who is responsible for full disclosure T his chapter begins with a quick overview of corporate governance and ends by shedding light on the explanatory notes and other information found in most corporate annual reports. For a complete picture of corporate annual reports, see Chapter 5. Annual reports educate the shareholders about corporate operations for the past year. Also in this chapter, you find out how a business becomes a corporation, and you review the four characteristics of a corporation: continuity, easy transferability of shares, centralized management, and (the biggie) limited liability. The complete list of notes and disclosures that may appear on a corporate annual report is quite long, so this chapter can’t cover them all. Instead, it focuses on the most common explanatory notes and disclosures popping up on corporate annual reports. Realizing How Corporations Should Govern Themselves Simply put, corporate governance is the framework under which a corporation operates. At its core, this framework involves establishing financial controls (policies and procedures that govern how the company’s finances are handled), 322 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements showing accountability to the shareholders, and making sure corporate management acts in the best interest of the shareholders and the community in which it operates. Financial controls and accountability are covered in depth in the upcoming section “Reviewing Common Explanatory Notes.” Part of a corporation’s self-regulation includes fully disclosing information on its financial statements. Hence the focus on corporate governance in a chapter about financial statement notes and disclosures. The subject of corporate governance could fill an entire book. But here are just a couple examples of ways that corporations need to self-regulate: ✓ Acting in the best interests of the shareholders: The corporation should operate so that the shareholders can expect a reasonable rate of return. For example, the corporation doesn’t pay excessive bonuses to corporate officers that reduce cash flow to such a point the business can’t effectively operate. ✓ Being sensitive to environmental concerns: The corporation shouldn’t pollute or cause health issues through its business waste or other byproducts for those living in the communities in which the business operates. Identifying Corporate Characteristics Many people have only a murky understanding of how a business becomes a corporation and what being a corporation means. This section quickly walks you through the process and explains the characteristics of a corporation to provide a broader context for understanding corporate governance and financial statement disclosures. Incorporation — the process of turning a regular old business into a corporation — is governed by state statute. If a company wants to set up shop as a corporation, it must play by the rules of the state in which it operates. For more about incorporating, see Book VI, Chapter 1. In most states, the incorporation process kicks off when the company files a corporate charter or articles of incorporation with the Secretary of State. This document contains all pertinent facts about the new corporation, including its name, address, and information about the type and number of stock shares it’s authorized to issue. The corporation must name a registered agent: the person the Secretary of State contacts with questions about the corporation. After the charter is accepted by the Secretary of State, parties interested in purchasing shares of stock in the business hold a meeting. These new shareholders then elect a board of directors, and the corporation is off and running! Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures This is a very simplified version of the incorporation process, which can vary by state. An initial public offering (IPO) — when a company offers shares of common stock to the public for the first time — is much more complicated than the previous paragraph may lead you to believe. Every corporation has four characteristics: ✓ Limited liability: This term means that investors in a corporation normally can’t be pursued for corporate debt. If a vendor, a lender, or some other entity to which it owes money sues the corporation, the individual investors are generally off the hook. However, you may encounter exceptions to this general rule, which hinge on the corporation managing itself according to state statute. Also, the federal government and state departments of revenue can go after shareholders or corporate officers for certain types of unpaid taxes. One example is the trust fund portion of the payroll taxes, which includes the employee portion of federal withholding tax, Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax, and Medicare. ✓ Easy transferability of shares: This characteristic means that if a person has the money, he can purchase shares of stock in a corporation — with the expectation of selling the shares in the future if he needs the money. However, for closely held corporations (those with few shareholders), this characteristic doesn’t quite ring true. If you’re the majority shareholder in a private corporation, you don’t have to sell shares to just anyone. Easy transferability of shares applies more to the purchase and sale of shares of publicly traded stock. Publicly traded stocks trade on exchanges, which are set up to connect buyers and sellers. For example, if you want to buy shares of AT&T stock, you don’t have to get permission from good ole’ Ma Bell. You just call up your friendly neighborhood stockbroker — or go online. In either case, you make the trade through an exchange. ✓ Centralized management: The management of a corporation shouldn’t be divided among many different groups. For the corporation to function at full efficiency, shareholders give up the right to chime in on every decision it makes. The shareholders elect the board of directors, who oversee the corporate operations and choose officers to handle the day-to-day business operations. ✓ Continuity: Until the corporation is formally dissolved, it’s assumed to have unlimited life, continuing out into perpetuity. The members of the board of directors can change, corporate officers can change, or there can be a different mix of shareholders, but the corporation just rolls on and on. 323 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 324 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Reviewing Common Explanatory Notes As noted earlier in this chapter, one aspect of corporate self-governance is giving financial statement users the complete information they need in order to accurately gauge the company’s performance and financial health. Some of that information comes in the form of explanatory notes. Leveling the playing field among financial statements Explanatory notes are discussions of items accompanying the financial statements; they contain important disclosures that aren’t presented in the financial statements themselves. The financial statements are the income statement (see Book IV, Chapter 2), balance sheet (see Book IV, Chapters 3 to 5 and Book V, Chapter 1), and statement of cash flows (see Book V, Chapter 2). Another term for an explanatory note is footnote or just note. This chapter uses all three terms so you get used to seeing them used interchangeably. Such notes are essential to fulfill the needs of the external users of the financial statements: people like you who may be interested in investing in the business, banks thinking about loaning the company money, or governmental agencies making sure the company has complied with reporting or taxation issues. External users don’t work for the company, so they aren’t privy to the day-to-day accounting transactions taking place within the business. Information that can’t easily be gleaned from reviewing the financial statements has to be spelled out in notes and disclosures, which explain how or why a company handles a transaction a certain way. Full disclosure allows external users to understand what’s going on at the company and creates a level playing field so an external user can compare the financial statements of one company with those of another company. Such notes are part of the corporate annual report (see Chapter 5), which provides shareholders with both financial and nonfinancial information about the company’s operations in past years. The notes come after the financial statements in the corporate annual report and are ordered to mirror the presentation of the financial statements. In other words, notes for income statement accounts come first, followed by balance sheet notes, and then items reflecting on the statement of cash flows. Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), introduced in Book IV, Chapter 1, requires certain explanatory notes specifically for publicly traded companies. However, as a best practice, many preparers of financial statements for private companies follow SEC guidelines. Explaining significant accounting policies This section explains the explanatory notes commonly addressed in financial accounting textbooks. Most of these subjects are presented elsewhere in this book in more detail, so you get just a brief overview here and a reference to let you know where you can find more info. Keep in mind that each of these explanatory notes is just a light-bite (truncated) version. Depending on the company and the complexity of the underlying accounting transaction, explanatory notes can be long and boring to wade through for all but the most diligent and experienced investor. Each type of note is accompanied by a simple version of what you see in real life. The first order of business when a company prepares its explanatory notes is to describe in general the business and its significant accounting policies. Some businesses break the two broad topics into different notes. The first could be called “Basis for Presentation” and the second “Accounting Policies.” Alternatively, the company could have just one note called “Summary of Business and Accounting Policies.” Taking this first step creates a fairer presentation of the financial statements. Information about accounting policies helps financial readers to better interpret the statements. A footnote is needed for each significant accounting choice the company makes. At the very least, the explanatory notes should include what depreciation methods are in use, how a company values its ending inventory, its basis of consolidation, how it accounts for income taxes, information about employee benefits, and accounting for intangible assets. The following sections touch on each of these subjects in turn. Note also that explanatory notes may explain the time period and payments due on a capital lease. Leases aren’t covered in detail in this book, but keep in mind that you may see leases in the notes section. Reviewing depreciation and inventory valuation methods Depreciation (see Book III, Chapter 1) consists of spreading the cost of a long-term asset over its useful life, which may be years after the purchase. Inventory valuation methods detail how a business may value its ending inventory (see Book VIII, Chapter 2). 325 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 326 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements The methods a company opts to use for both depreciation expense and inventory valuation can cause wild fluctuations for the amount of assets shown on the balance sheet and the amount of net income (or loss) shown on the income statement. Because of this fluctuation, the financial statement user needs to know which methods the company uses in order to more fairly compare one company’s financial statement figures to another’s. Differences in net income could merely be a function of depreciation or valuation methodology — a fact the user would be unaware of without the footnote. Assuming that depreciation and inventory are addressed in note 1, here’s a truncated example of how such a note looks: NOTE: SUMMARY OF BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING POLICIES We compute inventory on a first-in, first-out basis. The valuation of inventory requires we estimate the value of obsolete or damaged inventory. We compute depreciation for financial reporting purposes using the straight-line method, generally using a useful life of 2 to 5 years for all machinery and equipment. Consolidating financial statements Consolidation is what happens when companies merge or when a larger company (called a parent company) acquires one or more smaller ones (subsidiaries). In the context of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), consolidation refers to the aggregation of financial statements of two or more companies so those statements can be presented as a whole. In this section of the footnotes, the company confirms the fact that the consolidated financial statements do indeed contain the financial information for all its subsidiaries. Any deviations from including all subsidiaries must be explained. Here’s a truncated example of a note addressing consolidation: NOTE: SUMMARY OF BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING POLICIES Our consolidated financial statements include our parent account and all wholly owned subsidiaries. Intercompany transactions have been eliminated, and we use the equity method, which means we report the value based on our proportionate ownership, to account for investments in which we own common stock. Accounting for income taxes Financial statements prepared by using GAAP and those prepared for tax purposes differ. The former are created by using what’s called book accounting, and the latter are created by using tax accounting. Temporary and permanent differences can exist between the book and tax figures. Keep reading for a brief explanation of each difference. Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures Here’s an example of a permanent difference: Using book accounting, assume a business can expense 100 percent of meals and entertainment costs it incurs in the normal course of business. For tax purposes, however, it can expense at most 50 percent of that same cost. This is a permanent difference because under the Internal Revenue tax code, the business is never able to expense 100 percent. The difference between book and tax expenses is permanent. The most common temporary difference relates to depreciation. Assume that, for book purposes, a company uses straight-line depreciation and for tax purposes a more accelerated method. In the short run, there will be a difference in depreciation expense. Eventually, over time, the amount of depreciation the company expenses for an asset will balance out so that under either method the total amount of depreciation is the same. The difference in depreciation expense is only temporary. The company must address the differences between book and tax, called deferred tax assets and liabilities, in the footnotes to the financial statements. Here’s a truncated example of how such a note may look: NOTE: TAXES Income before taxes was $7.68M, and the provision for federal taxes was $2.78M, an effective tax rate of 36.2 percent. Deferred income taxes reflect the net tax effects of temporary differences between the carrying amounts of assets and liabilities for financial reporting versus for tax reporting purposes. Spelling out employee benefits Details about the company’s expense and unpaid liability for employees’ retirement and pension plans are also spelled out in the footnotes. The obligation of the business to pay for postretirement health and medical costs of retired employees must also be addressed. Accounting for employee benefits is a somewhat advanced accounting topic. Just remember that employee benefits require an explanatory note, and you’ll be fine. Here’s a truncated example of how such a note looks: NOTE: RETIREMENT BENEFIT PLANS We provide tax-qualified profit sharing retirement plans for the benefit of our eligible employees, former employees, and retired employees. As of December 31, 2015, approximately 80% of our profit sharing fund was invested in equities with the rest in fixed-income funds. We have independent external investment managers. 327 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 328 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Walking through intangibles Intangible assets aren’t physical in nature as is a desk or computer. Two common examples of intangibles are patents, which license inventions or other unique processes and designs, and trademarks, which are unique signs, symbols, or names that the company uses. (See Book IV, Chapter 3 for more information about intangibles.) Besides explaining the different intangible assets the company owns via an explanatory note, the business also needs to explain how it has determined the intangible asset’s value posted to the balance sheet. Here’s a truncated example of how such a note looks: NOTE: INTANGIBLE ASSETS We classify intangible assets with other long-term assets. As of December 31, 2015, our intangible assets consisted of the following: patents, copyrights, and goodwill. They are generally amortized on a straight-line basis. We perform a yearly review to determine whether useful life is properly estimated, and to determine whether the value of the intangible asset has been impaired. Looking for important event disclosures A company must also provide information in its annual report explaining the following topics: accounting changes, business combinations, contingencies, events happening after the balance sheet date, and segment reporting. The topic of event disclosure is usually discussed separately from the topic of explanatory notes that accompany financial statements. But keep in mind that event disclosure information goes in the footnotes to the financial statements right along with the accounting method information described in the previous section. Accounting changes A company may have up to three types of accounting changes to report: a change in accounting principle, a change in an accounting estimate, or a change in a reporting entity. Narrative descriptions about accounting changes go in the explanatory notes to the financial statements very early in the game — usually in the first or second note. Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures Following is an explanation of each type of accounting change: ✓ Accounting principles guide the way the company records its accounting transactions. Under GAAP, a company is usually allowed different ways to account for transactions; for example, GAAP allows companies to use different depreciation methods to expense the cost of long-lived assets. For financial statements, changes in accounting principle have to be shown by retrospective application to all affected prior periods (unless doing so isn’t practical). This process involves three steps: • Adjust the carrying amounts of affected assets and liability accounts for the cumulative effect of the change. • Take any offset (difference in amounts) to beginning retained earnings. In other words, the difference in carrying amounts either increases or decreases beginning retained earnings. • If the financial report shows multiple years for comparison, show the effect of the new accounting principle in each of the reported years. ✓ Accounting estimates are numbers a company enters into the financial records to reflect its best guesses as to how certain transactions will eventually shake out. For example, going back to the depreciation example, consider the estimate for salvage value, which is how much a company assumes it will be able to get for a long-lived asset when the time comes to dispose of it. If something happens to make you believe your original estimate of salvage value was wrong and you change it, that’s a change in accounting estimate. A change in accounting estimate has to be recognized currently and prospectively. For example, if salvage value is recalculated, the current and future financial statements show the salvage value as corrected. No change is made to prior period financial statements. ✓ Reporting entities reflect which business combinations are shown on the financial statements, also known as consolidated financial statements. When a business owns more than 50 percent of another business, the investor business is called a parent and the investee is the subsidiary. If something changes in the way the subsidiaries show up on the financial statements, that’s a change in reporting entity. Changes in reporting entities are shown retrospectively to the financial statements of all prior periods. This means you have to show the dollar amount effect of the change of reporting entities in the balances of all related assets and liabilities. Any offsetting amount goes to the beginning balance of retained earnings. 329 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 330 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Business combinations Accounting textbooks typically cover basic business combinations, which include these three: ✓ Mergers: Two or more companies combine into a single entity. Mergers are usually regarded as friendly combinations — not hostile takeovers. ✓ Acquisitions: One company acquires another business. The business doing the acquiring takes over, and in essence the target (acquired) company ceases to exist. Acquisitions usually aren’t quite as friendly as mergers. ✓ Dispositions: A company transfers, sells, or otherwise gets rid of a portion of its business. For example, a shoe manufacturer makes dress shoes, slippers, and tennis shoes and decides to sell its slipper division to another company. If a company involves itself in any of these three activities during the financial reporting period, it has to explain the transaction and spell out the effect of the business combination on the financial statements. Business combination information goes in the explanatory notes to the financial statements very early in the game; it first crops up in the first or second note, and then it’s addressed as needed in subsequent notes. If a company is involved in a disposition, GAAP dictates that it disclose not only the facts and circumstances surrounding the disposition but also any anticipated operational losses from getting rid of a portion of its business. The losses are calculated net of tax, which means you factor in any increase or decrease in tax due because of the disposition. The company must also show any loss or gain on the sale of that portion of the business (also net of tax) on the income statement. These results are pulled out and reported separately because they won’t continue into the future. This activity is typically posted to an account called income (or loss) from discontinued operations. Contingencies A contingent liability exists when an existing circumstance may cause a loss in the future depending on other events that have yet to happen (and, indeed, may never happen). For example, the company is involved in an income tax dispute. Disclosing this contingent liability is a requirement if the company will owe a substantial amount of additional tax penalties and interest should the unresolved examination end up in the government’s favor. See Book IV, Chapter 4 for a general discussion about contingencies. Here’s a truncated example of a contingency note: NOTE: COMMITMENTS AND CONTINGENCIES Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures As of December 31, 2015, we were contingently liable for guarantees of indebtedness owed by third parties in the amount of $3 million. These guarantees relate to third-party vendors and customers and have arisen through the normal course of business. The amount represents the maximum future payments that we could be responsible to make under the guarantees; however, we do not consider it probable that we will be required to satisfy these guarantees. A contingent liability needs to be reported not only as a disclosure via a footnote to the financial statements but also in the financial statements if it’s probable and the amount of loss can be reasonably estimated. This disclosure specifically states that the company doesn’t consider the loss contingency probable, so footnote disclosure without inclusion in the financial statements is all that’s required for this example. Events happening after the balance sheet date The company also must address any subsequent events happening after the close of the accounting period but before the financial statements are released. Like contingent liabilities, depending on their nature, subsequent events may just need a disclosure in the footnotes to the financial statements, or they may require both a disclosure and an adjustment to the figures on the financial statements to reflect the dollar amount effect of the subsequent event. How the company handles the event happening after the balance sheet date depends on whether the event is classified as a Type I or Type II event: ✓ Type I events: These events affect the company’s accounting estimates reflecting on the books but not confirmed as of the balance sheet date. (See the earlier section “Accounting changes” for an explanation of accounting estimates.) A good example is the estimate for uncollectible accounts. This estimate exists on the books at the balance sheet date, but the company can’t be sure of the resolution of the estimate until a subsequent event occurs, such as a customer filing for bankruptcy. At that point, the company confirms that the amount is actually uncollectible. If the confirming event (such as the bankruptcy) occurs after the balance sheet date but before the financial statements are finalized, the company has to adjust its financial statements. Footnote disclosure can be used to explain the event as well. ✓ Type II events: These events aren’t on the books at all before the balance sheet date and have no direct effect on the financial statements under audit. The purchase or sale of a division of the company is a classic example of a Type II event. These events are also called nonrecognized events. This means that if they’re material, they have to be disclosed in footnotes to the financial statements, but the financial statements don’t have to be adjusted. 331 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 332 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Here’s a truncated example of a note on an event taking place after the balance sheet date: NOTE: SUBSEQUENT EVENT On February 1, 2015, we entered into an agreement to sell our ownership interests in our ABC division to XYZ Manufacturing for approximately $5 million in cash. The transaction is subject to certain regulatory approvals. We expect the transaction to close in the 4th quarter of 2015. Segment reports Business segments are components operating within a company. For example, a clothing manufacturer makes dresses, blouses, pants, and sweaters; these are all business segments. If a business has various segments, it must disclose info about each segment — such as its type, geographic location, and major customer base — so that the users of the financial statements have sufficient information. Here’s a truncated example of how such a note looks: NOTE: SEGMENT REPORTING As of December 31, 2015, our organizational structure consisted of the following operating segments: North America and Europe. Our North American segments derive the majority of their revenue from the sale of finished clothing. Our European segment derives the majority of its revenue from the sale of fabric and notions to other European companies. Putting the Onus on the Preparer The explanatory notes and disclosures, like the financial statements themselves, are the responsibility of the company’s management and its accounting staff. Management and the internal accounting staff prepare the explanatory notes and disclosures by using the applicable American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) disclosure checklist. All GAAP guides contain a comprehensive appendix listing the full AICPA disclosure checklist. After management prepares the financial statements and explanatory notes and disclosure information, the company often hires an independent certified public accountant (CPA) to evaluate management’s work. The CPA is independent, which means she has no special relationship to or financial interest in the company. The CPA may or may not be required to be independent, depending on the work the CPA performs for the client. Chapter 4: Reading Explanatory Notes and Disclosures CPAs perform three major types of financial statement work: ✓ Audits: Auditing is the process of investigating information that’s prepared by someone else, usually company management and the accountants the company employs, in order to determine whether the financial statements are fairly stated. CPAs performing audits must investigate the assertions that a company makes on its financial statements, including any notes and disclosures. Financial statement assertions often relate to how the company conducts business, such as how it makes and spends money and how it records financial information about its property, plant, and equipment; its long-term liabilities and equity; and its cash and investments. An audit provides a reasonable level of positive assurance, which means the financial statements are free of material errors and are stated in accordance with GAAP. An audit does not, however, provide an absolute guarantee that the financial statements contain no errors. Also, an audit isn’t designed or performed to detect all fraud. Although accountants employed by the business prepare the financial statements (including the notes and disclosures), only an independent CPA can audit them. If auditing is a subject that interests you, check out Auditing For Dummies by Maire Loughran (Wiley). ✓ Reviews: When a CPA conducts a review, she looks at the company’s documents and provides negative assurance, which means the CPA finds no reason to believe the information prepared by company management is incorrect. For example, the CPA looks over the company’s financial statements, noting whether they’re of proper appearance. For example, do the statements contain appropriate explanatory notes and disclosures per the AICPA disclosure checklist? Do they conform to GAAP? Reviews are usually performed for privately owned companies when the users of the financial statements require some sort of assurance about the financial statements’ assertions but don’t require a full-blown audit. ✓ Compilations: If a CPA is hired to do a compilation, she can compile financial statements (using information provided by company management) that omit footnote disclosures required by GAAP or that use another comprehensive basis of accounting, such as cash-basis accounting (see Book III, Chapter 6). Preparing the statements this way is okay as long as omitting the explanatory notes and disclosures is clearly indicated in the report without intent to mislead users. When footnote disclosures have been omitted, CPAs add a paragraph to the compilation report stating that management has elected to omit disclosures. This paragraph lets the user know that if the financial statements did contain the explanatory notes or disclosures, that information may affect their conclusions. 333 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 334 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Here’s an example of the language used when a company is omitting compilation disclosures: Management has elected to omit substantially all the disclosures required by generally accepted accounting principles. If the omitted disclosures were included in the financial statements, they might influence the users’ conclusions about the company’s financial position, results of operations, and its cash flows. Accordingly, these financial statements are not designed for those who are not informed about such matters. Chapter 5 Studying the Repor t to the Shareholders In This Chapter ▶ Staying private or going public: Why annual reports differ among companies ▶ Identifying the three purposes of a corporate annual report ▶ Recognizing common sections in an annual report ▶ Analyzing Form 10-K M ost of the chapters in Books IV and V are devoted to explaining how to prepare financial statements (the income statement, balance sheet, and statement of cash flows). But what happens to these statements after they’re done? Do they just get filed away in case anyone asks to see them? Absolutely not! The financial statements become the heart of a company’s annual report to its shareholders. An annual report is a document that the company can share with its current owners, potential investors, creditors, the media, and so on; it can be an important public relations tool that shows the outside world how the company is doing. For many companies, the report is also a regulatory requirement. This chapter explains the ins and outs of a corporate annual report, including the three key purposes it serves. Here you also find out about Form 10-K, an annual filing that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires from most publicly traded companies. 336 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Why Private and Public Companies Treat Annual Reports Differently A corporate annual report (which may also be called the annual report or the annual report to shareholders) may look different depending on whether the company in question is private or public. The corporate annual report for a private company — one whose stock isn’t traded on the open market — is usually a bare-bones document that gives users just the mandatory information about how the company performed in the past year. You don’t find many bells and whistles in a private company’s report. That’s because most private companies are closely held (they have a small number of owners), so they aren’t too concerned about how a larger audience will react to the report. On the other hand, a public company’s report is often loaded with bells and whistles, such as marketing material designed to tout the company to potential investors and creditors. Another key difference between the annual reports of private and public companies is that private companies don’t always have their financial statements audited, while public companies do. A private company usually has its financial statements audited only if doing so is required to fulfill a business purpose. (Perhaps a creditor or an insurer providing bonding — compensation to customers in case the company doesn’t fulfill its obligations — requires an audit.) As explained later in this chapter, public companies’ financial statements must always be audited in order to fulfill regulatory requirements. What does it mean for the statements to be audited? After the company creates the statements, it employs an independent certified public accountant (CPA) to gather sufficient information to express an opinion on whether the statements are materially correct. (In other words, they don’t contain any misstatements that could significantly impact the decisions made by the financial statement users.) See Book IX for a more detailed explanation of auditing. Only after a public company’s financial statements are audited can they be included in the company’s annual report to the shareholders. This chapter focuses on the annual reports that large public companies prepare to show you what the most elaborate reports look like. You can access the corporate annual report for just about any publicly traded corporation online. Go to the home page of any company in which you have an interest. Look for an “Investor” link on the home page, and click it. Voilà! Chances are you’re looking at the annual report. If you can’t easily find the “Investor” link, don’t spin your wheels. Just search the web by using the key phrase “[Company name] corporate annual report.” You’ll likely locate it easily. Chapter 5: Studying the Report to the Shareholders Fulfilling Three Purposes This section spells out the three distinct goals of the annual report for a public corporation: to promote the company, to display its financial ­performance and goals, and to meet regulatory requirements. Something to keep in mind: Going forward, large public corporations will undoubtedly turn more and more toward electronic media to distribute their annual reports. Doing so is a cost-saver and demonstrates a corporation’s commitment to using resources wisely. Serving a marketing and PR function A substantial portion of a corporate annual report is devoted to the company’s bragging about what it has accomplished during the preceding year and where it expects to go in the coming year. The language can be full of hyperbole and puffery. The purpose of this marketing and public relations material is to keep existing shareholders pumped up about the wisdom of their investment and to attract new shareholders to the fold. Stating financial performance and goals Less flashy but of decidedly more interest to serious investors are the sections addressing the corporation’s financial performance in the past year. The information in these sections indicates how closely the company came to hitting projected revenue figures. Additionally, the company addresses how it intends to improve financial performance going forward. Here are some examples of financial goals: ✓ Increasing revenue by expanding into global markets. ✓ Becoming regarded as a premier employer. ✓ Managing operations for the greatest effectiveness. ✓ Increasing brand awareness. Brand awareness is a fancy way of saying the company wants to make sure consumers recognize the company and its signature products. The purpose of brand awareness is also tied to making the company’s products preferred over similar ones marketed by the competition. 337 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 338 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Meeting regulatory requirements Most large companies would produce an annual report even if the U.S. ­government didn’t require them to. That’s because an annual report is such a crucial marketing and PR tool. However, because publicly traded companies must adhere to stringent regulatory requirements, not issuing an annual report isn’t an option. Companies that issue publicly traded securities — as well as companies that meet certain other criteria — have to file annual reports with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The specific report required by the SEC is called Form 10-K. The final section of this chapter explains which companies have to file this form and what exactly it entails. To avoid having to create two separate types of annual reports, some companies include in their reports to shareholders all the information that the SEC requires be included in Form 10-K. SEC and other regulatory bodies are addressed in Book IV, Chapter 1. Reading the Annual Report to Shareholders This section takes you through the sections that you most often find in a corporate annual report. With the exception of the audited financial statements, the sections are put together in an effort to draw the external reader into the inner workings of the business in an attempt to raise the users’ comfort with and confidence in the company. Audited financial statements, on the other hand, require a specific presentation. Writing the narrative for a corporate annual report is an art. Many times, the report is contracted out to professionals rather than produced in-house, although the company’s chief executive or managing director always has a say in the format of the report. Keep in mind that this section contains just a brief overview of what you may expect to see in a corporate annual report. Especially if a company is large, it may include a plethora of additional information. If you have the time, check out Reading Financial Reports For Dummies by Lita Epstein (Wiley). While the following sections touch on the fundamentals, this book walks you through reviewing financial reports from A to Z. Chapter 5: Studying the Report to the Shareholders Meeting the chair of the board of directors Most casual investors in a corporation have absolutely no idea who the chairperson of the board of directors is or what that person does. Although the duties of the chairperson are similar from company to company, the individual holding the position is unique to the particular company. The chairman of the board of directors is the head honcho who oversees the board of directors (and is usually elected by the other members of the board). The board of directors consists of individuals elected by the shareholders to guide the company based on the firm’s mission or vision. The board of directors doesn’t handle the day-to-day activities of any business; that’s management’s job. However, approving the hiring of upper management personnel, such as the chief executive officer (CEO), is a function of the board of directors. In the corporate annual report, you meet the chairman via a letter whose salutation is something like “Dear Fellow Shareholder.” The letter gives the company’s top management team a chance to review all the accomplishments the company achieved during the preceding year. The letter also summarizes goals for the future. It ends by thanking the shareholders for their support and offering a firm promise to work tirelessly to continue earning the trust of the shareholders and growing their value in the company stock. Highlighting key financial data In the beginning of the annual review, the company gives the shareholders a condensed version of how well the company performed during the preceding year. This condensed info provides the more casual readers with what the company perceives as the main points of interest. At the least, this section contains a summary of operations, earnings per share data, and balance sheet data: ✓ Summary of operations: This summary shows the company’s bottom line net income for at least three years (and preferably five to ten years). Net income is the excess of revenue and gains over expenses and losses during a financial period. ✓ Earnings per share (EPS): This calculation shows the net income per outstanding share of common stock. Read on for an explanation of this formula. Many investors focus on this figure, comparing it to their other investments and to other companies’ EPS in the same industry. For example, an investor may compare the EPS of The Coca-Cola Company to the EPS of PepsiCo to gauge the value of one company’s stock over the other, given that these companies are in the same industry. 339 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 340 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Three calculations you may see in an annual review are basic EPS, diluted EPS, and cash dividends (see Book IV, Chapter 5 for additional details on all three). Here’s an example of each: • Basic EPS: To figure basic EPS, take net income for the financial period and divide it by the weighted average number of shares of common stock outstanding. The weighted average factors in the fluctuations of stock outstanding during the entire year instead of just taking stock outstanding at January 1 and stock outstanding at December 31 and dividing it by two. If ABC Corp. has net income of $100,000, and the weighted average number of shares of common stock outstanding is 21,833, basic EPS is $100,000 ÷ 21,833 = $4.58. • Diluted EPS: If the company has issued stock options or convertible debt or convertible preferred stock that the investor has the option to convert into common stock, the company has to show diluted EPS, which is a complicated calculation. (Stock options are benefits allowing employees to purchase a certain number of shares of company stock at a pre-determined date and price.) Diluted EPS calculates earnings per share by estimating how many shares could theoretically exist after all stock options and convertible securities have been exercised into common stock shares. So if ABC Corp.’s weighted average of common stock outstanding after adding in these extras is 24,989, its diluted EPS is $100,000 ÷ 24,989 = $4.00. • Cash dividends: This calculation is the amount per share paid to shareholders of record. The company must have earnings to pay a dividend, because dividends are a payment of earnings. The board of directors determines the dividend paid, if any, to shareholders of record. ✓ Balance sheet data: This section shows selected figures from the balance sheet in which the company believes the shareholders have an interest. For example, the company may show total assets, which are all assets (current and long-term) that the company owns as of the balance sheet date. The company may also show long-term debt, which is any debt the company won’t have paid off within 12 months of the balance sheet date. Even though these figures are compressed, they’re based upon — and must reconcile with — the audited financial statements. Figure 5-1 shows an example of this condensed financial data. Chapter 5: Studying the Report to the Shareholders 341 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements Figure 5-1: Select financial information. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Touting company achievements In this section, which has a distinct public relations purpose, the company expands upon any facts the chairman of the board discusses in his letter to the shareholders. For example, this section may break out how the company has increased growth per capita, which is the average per person living in an area the company serves. Per capita growth could mean that the company sold more products to existing consumers or expanded its sales base into new markets or countries. Companies want to emphasize that they’re attracting new customers while still maintaining a bond with existing customers. Looking into the future In its annual report, a company also addresses where it sees itself in the future — both short-term and long-term. Although the business may not provide specific financial targets (like total sales or new customers), it gives the reader its strategy for moving forward. Doing so addresses any concerns that an investor may have that the business is a going concern: that it will be able to stay in business for at least 12 months beyond the balance sheet date, generating or raising enough cash to pay its operating expenses and make appropriate payments on debt. Obviously, investors aren’t going to get all fired up about their ownership in the company stock if they believe the company will be around for only a couple more years. Therefore, annual reviews normally give a three-to-fiveyear plan on growth methodology. Often, companies associate their growth predictions with social and economic transitions — for example, changes in population demographics such as aging and income. 342 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements Getting to know key management and board members This section of the annual report introduces other members of the board of directors, the management team for each division of the company, and committee members (such as members of the audit committee). Most likely, the report includes pictures of all of them posed at the company headquarters. Walking through Form 10-K The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires that all companies registered with it annually file Form 10-K shortly after the end of the company’s fiscal year. The SEC also requires that Form 10-Q must be filed each fiscal quarter. Companies that have a certain class of securities, a certain level of assets or number of holders, and/or which are publicly traded must register with the SEC: ✓ Class of securities: Any company issuing securities traded publicly on a stock exchange or in the over-the-counter market (where dealers buy from and sell to interested investors for their own accounts via the phone or computer) must register with the SEC. ✓ Assets or holders: Any company with more than $10 million in assets and 500 or more holders of any class of equity, such as common or preferred stock, must register as well. ✓ Publicly traded: Any company whose equity (stock) or debt (bonds) is publicly sold pursuant to a registration statement must register with the SEC. A registration statement is filed with the SEC when a company wants to issue securities to the public. It includes a full and fair disclosure of the securities being issued, info about the company and what it does, the company’s financial position, and what the company plans to do with the proceeds from the issuance. The company submitting the filing is referred to as the registrant. Registration with the SEC doesn’t mean the SEC is giving the company a stamp of approval. It merely means the company has provided all documents required for registration. Form 10-K consists of a facing page and four additional parts: business, market/financial, management/corporate governance, and exhibits/financial statement schedules. The following sections explain each part in turn. Chapter 5: Studying the Report to the Shareholders Facing page: Identifying the affected company The facing page of Form 10-K gives basic info about the company (the SEC registrant), including its name, address, telephone number, and the fiscal year in question. It also lists the title and class of securities (equity and debt) that are registered with the SEC and the number of shares outstanding. Some more advanced information appears on the facing page as well, such as whether the company is required to file certain reports or has done so voluntarily. Part I: Finding out more about the registrant Part I contains information about the company, including an overview of what the company does and any risk factors surrounding it. An example of a risk factor may be heightened competition hurting the core business or a significant depletion of the raw materials needed to make its products. This section requires the following additional info: ✓ The year the company organized ✓ Its form of organization ✓ Any bankruptcy proceedings, business combinations, or changes in the method of conducting its business For example, the registrant may state, “We were incorporated in February 1945 under the laws of the State of Delaware and succeeded to the business of a New York corporation.” The Part I information can be incorporated by reference from the annual report to the stockholders if that report contains the required disclosures. If the company opts to do this, it must cross-reference Form 10-K to the annual report showing what was incorporated and from which pages in the annual report. For example, the company could write, “See page 10 of the 2015 annual report for this information.” Part II: Revealing the company’s financial performance Part II is really the meat of Form 10-K because it reveals a company’s financial performance in the past year. This part features information about 343 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 344 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements where the company’s stock is traded, analysis and discussion from company ­management, and the audited financial statements. Market information and financial highlights In Part II, the company tells the SEC in which market the company’s common stock lists and trades. Two U.S. examples are the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. The company also lists the high and low common stock market prices and dividends declared for the year in question. More than likely, the company will also include its key financial data from the annual report to stockholders. (See the earlier section “Highlighting key financial data.”) Management discussion and analysis Part II also includes a management discussion and analysis section. Normally, management recaps business operations and discusses significant financial trends within the company during the past couple years. For example, for a fast-food restaurant, management would probably discuss how government regulations to combat obesity are expected to affect the business. Audited financial statements The audited financial statements, critical accounting policies, estimates, and explanatory notes and disclosures also appear in Part II. Accounting policies include how a company recognizes revenue and expenses and where these figures show up on the financial statements. An example of an estimate is the allowance for uncollectible accounts, which is what the company anticipates it won’t be able to collect from customers who have purchased on credit; see Book IV, Chapter 3. For additional guidance on explanatory notes and disclosures, see Chapter 4. Auditing is the process of systemically gathering enough evidence to support the facts a company is showing in the financial statements. The results of an audit are communicated to all interested users in a format that they can both understand and use for their intended purposes. The goal of a financial statement audit is for the auditor to form an opinion regarding whether the financial statements are or aren’t free of material misstatement. Auditors aren’t responsible for preparing the financial statements they’re auditing. In fact, they can’t prepare them; to do so would violate the concept of independence. Therefore, the items under audit are company management’s responsibility. In other words, the financial statements contain management assertions — management’s assurance that the information provided is materially correct. A company accountant uses these assertions to produce the financial statements. Chapter 5: Studying the Report to the Shareholders After conducting the audit of the financial statements, the auditor can express one of four basic options: ✓ Unqualified: An unqualified opinion is the best the client can get! It means that the audit has been conducted in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards (GAAS) and that the financial statements conform with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in all material aspects. ✓ Qualified: An auditor may have to issue a qualified opinion when the company doesn’t use GAAP consistently, or circumstances may have prevented the auditor from getting enough evidence to be able to issue an unqualified opinion. When the end user (a potential investor, for example) sees this opinion, she knows she can’t rely on the information in the financial report as much as she could if the auditor offered an unqualified opinion. Qualified opinions are referred to as “except for” opinions, because the language in the audit report often uses the phrase “except for” to explain why the report is qualified. ✓ Adverse: As you can probably guess, an adverse opinion isn’t good! The auditor issues an adverse opinion if the financial statements don’t present the client’s financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with GAAP. This type of opinion is issued only when the financial statements contain material departures from GAAP. (Book IV, Chapter 1 defines materiality and how it applies to financial statements. For now, just realize that what is material for one business may not be material for another.) ✓ Disclaimer of opinion: This happens when the auditor can’t form an opinion on a client’s financial statements. For example, a disclaimer may be issued in cases when the auditor isn’t independent. Book IX, Chapter 1 displays a standard unqualified audit opinion. That report gives you some idea of the language used. Part III: Identifying management and corporate governance Yippee! You’ve successfully navigated the more detailed parts of Form 10-K. Heading toward the finish line, next up is a discussion of management and governance. In this short section, the company lists its directors and executive officers — most likely with a reference back to Part I of Form 10-K (if that section has already provided sufficient information). 345 Book V Reporting on Your Financial Statements 346 Book V: Reporting on Your Financial Statements For example, Part III may read as follows: “See Item X in Part I of this report for information regarding executive officers of the corporation.” Otherwise, the company lists here each individual’s name, title/office, and any other relevant information (such as whether the individual is associated with another unrelated organization). Now, what about corporate governance? Some of the issues corporate governance addresses are ethical business behavior, responsibility for the community in which the company operates, and equitable treatment of the shareholders. For example, corporate governance demands full and fair disclosure associated with the financial statements so investors can make informed decisions. For a manufacturing company, this section may note that it takes care not to pollute the drinking water of adjacent cities with illegal dumping of factory runoff. Most companies state that they have a Code of Business Conduct for both employee and nonemployee directors. If the code isn’t included in Form 10-K, the form will at least provide information as to where on the company website this information resides. See Chapter 4 for more about corporate governance. Part IV: Exhibits, financial statement schedules, and signature This section merely lists the documents that are part of Form 10-K and gives the exhibit number where each document can be found. This section can go on interminably, listing such exhibits as “Exhibit No. 6.8.5: 2005 Stock Option Plan of the Company: amended and restated through December 31, 2015.” Pretty exciting stuff! Finally, the last page contains the signature of the chairman of the board of directors, the chief executive officer, the chief financial officer, the principal accounting officer, all directors, and the attorney-in-fact (the individual holding power of attorney) attesting to the fact the report doesn’t contain any untrue statement of a material fact or omit any necessary material facts. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Managing inventory can boost profits. Discover various strategies for managing inventory cost-effectively by visiting www.dummies.com/extras/accountingaio for free guidance. In this book… ✓ Structure a business to attract capital and issue stock shares to raise capital. Find out more about what potential investors really want to see in a company’s financials. ✓ Choose the appropriate legal structure for a business — sole-proprietorship, partnership, LLC, C-corp., S-corp., or something else. The right legal structure provides valuable legal protection and potential tax savings. ✓ Draft a business plan that increases your chances of securing loan approval or attracting eager investors. Tell your company’s growth story to prospective shareholders. ✓ Build a budget to help executives and managers make better business decisions and boost their organization’s bottom line. Budgeting not only keeps your business on track financially but also helps inform spending decisions so you get the most bang for your buck. ✓ Tweak your budget to accommodate different levels of production and other potential variables. Play “what-if” with different production and product-development scenarios to plan production and sales and maximize profit. ✓ Get a handle on long-term debt to reduce interest and improve cash flow. Make informed decisions about how much cash your business needs to operate and how much of that cash you’ll generate through debt. Chapter 1 Incorporating Your Business In This Chapter ▶ Structuring the business to attract capital ▶ Taking stock of the corporate legal structure ▶ Issuing and managing stock shares T he obvious reason for investing in a business rather than putting your money in a safer type of investment is the potential for greater rewards. Note the word potential. As an owner of a business, you’re entitled to your fair share of its profit, as are the other owners. At the same time, you’re subject to the risk that it could go down the tubes, taking your money with it. Ignore the risks for a moment and look at just the rosy side of the picture: Suppose the doohickeys that your business sells become the hottest products of the year. Sales are booming, and you start looking at buying a fivebedroom mansion with an ocean view. Don’t make that down payment just yet — you may not get as big a piece of the profit pie as you’re expecting. Some claims to that profit may rank higher than yours, and you may not see any profit after all these claims are satisfied, because the way the profit is divided among owners depends on the business’s legal structure. This chapter shows how legal structure determines your share of the profit — and how changes beyond your control can make your share less valuable. Securing Capital: Starting with Owners Every business needs capital. Capital provides money for the assets a business needs to manufacture products, make sales, and carry on operations. Common examples of assets are the working cash balance a business needs for day-to-day activities, products held in inventory for sale, and long-life operating assets (buildings, machines, computers, office equipment, and so on). 350 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Assume a typical business in your industry needs capital equal to one-half of annual sales revenue. You would plan your financing efforts to raise that amount of capital. Of course, this ratio varies from industry to industry. Many manufactures need a high ratio of capital to sales, so they’re described as being capital intensive. One of the first questions that providers of business capital ask is how the business entity is organized legally. That is, which specific form or legal structure is the business using? The different types of business legal entities present different risks and potential rewards to business capital providers. Whatever its legal structure, a business gets the capital it needs from two basic sources: debt and equity. Debt refers to the money borrowed by a business, and equity refers to money invested in the business by owners plus profit earned and retained in the business (instead of being distributed to its owners). No matter which type of legal entity form it uses, every business needs a foundation of ownership (equity) capital. Owners’ equity is the hard-core capital base of a business. In starting a new business from scratch, its founders typically must invest a lot of sweat equity, which refers to the grueling effort and long hours to get the business off the ground and up and running. The founders don’t get paid for their sweat equity, and it doesn’t show up on the balance sheet. Contrasting two sources of equity Every business — regardless of how big it is, whether it’s publicly or privately owned, and whether it’s just getting started or is a mature enterprise — has owners. Virtually no business can get all the capital it needs by borrowing. Your firm can obtain equity financing from two sources: ✓ Investors: Outside investors can provide the business with both start-up and a continuing base of capital, or equity. ✓ Owners: The firms’ founders may provide their own capital in exchange for equity. Without the foundation of equity capital, a business wouldn’t be able to get credit from its suppliers and couldn’t borrow money. As they say in politics, the owners must have some skin in the game. Considering what investors want The equity capital in a business always carries the risk of loss to its owners. So, what do the owners expect and want from taking on this risk? Their expectations include the following: ✓ Share in profits: They expect the business to earn profit on their equity capital in the business and to share in that profit by receiving cash distributions from profit and from increases in the value of their ownership shares, with no guarantee of either. Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business 351 ✓ Participate in management: They may expect to directly participate in the management of the business, or they may plan to hire someone else to manage the business. In smaller businesses, an owner may be one of the managers and may sit on the board of directors. In very large businesses, however, you’re just one of thousands of owners who elect a representative board of directors to oversee the managers of the business and protect the interests of the non-manager owners. ✓ Share in sales proceeds: Looking down the line to a possible sale of the business or a merger with another business, they expect to receive a proportionate share of the proceeds if the business is sold or to receive a proportionate share of ownership when another company buys or merges with the business. Or they may end up with nothing in the event the business goes kaput and nothing’s left after paying off the creditors. When owners invest money in a business, the accountant records the amount of money as an increase in the company’s cash account. And, using doubleentry accounting, the amount invested in the business is recorded as an increase in an owners’ equity. (See Book I, Chapter 2 to find out about doubleentry accounting.) Owners’ equity also increases when a business makes profit. See Book IV, Chapter 2 for more on why earning profit increases the amount of assets minus liabilities, which is called net worth, and how this increase in net worth (due to profit) is balanced by recording the increase in owners’ equity. Dividing owners’ equity Certain legal requirements often come into play regarding the minimum amount of owners’ capital that a business must maintain for the protection of its creditors. Therefore, the owners’ equity of a business is divided into two separate types of accounts: ✓ Invested capital: This type of owners’ equity account records the amounts of money that owners have invested in the business, which could have been many years ago. Owners may invest additional capital from time to time, but generally speaking they can’t be forced to put additional money in a business (unless the business issues assessable ownership shares, which is unusual). Depending on the legal form of the entity and other factors, a business may keep two or more accounts for the invested capital from its owners. ✓ Retained earnings: The profit a business earns over the years that has been retained and not distributed to its owners is accumulated in the retained earnings account. If all profit is distributed every year, retained earnings has a zero balance. (If a business loses money, its accumulated loss causes retained earnings to have a negative balance, which generally is called a deficit.) If none of the annual profits of a business are distributed to its owners, the balance in retained earnings is the cumulative profit the business has earned since it opened its doors (net of any losses along the way). Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 352 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Whether to retain part or all of annual net income is one of the most important decisions that a business makes; distributions from profit have to be decided at the highest level of a business. A growing business needs additional capital for increasing its assets, and increasing the debt load of the business usually can’t supply all the additional capital. So, the business plows back some of its profit for the year into the business, rather than distributing it to its owners. In the long run, this may be the best course of action, because it provides additional capital for growth. Leveraging equity capital with debt Leverage refers to the idea of using debt to add capital to your business. Leverage is a good strategy if the company can generate more in earnings than it pays in interest expense and fees on the debt. If a business is interested in leverage, the first consideration is how much of the balance sheet should include debt. Suppose a business has $10 million in total assets. ( You find assets in the balance sheet of a business — see Book IV, Chapter 3.) The balance sheet equation (in Book I, Chapter 1) is Assets less Liabilities equals Equity. $10 million in total assets doesn’t mean that the company has $10 million of equity. You have to subtract liabilities from assets to compute equity. Assuming the business has a good credit rating, it probably has some amount of trade credit extended for purchases, which is recorded in the accounts payable liability account (see Book IV, Chapter 4). Other kinds of operating liabilities may also come into play. Suppose its accounts payable and other operating liabilities total $2 million. At this point, you’ve identified $10 million in total assets, less $2 million in liabilities. That leaves $8 million to account for. The $8 million could represent other liabilities. Some of the $8 million may be equity. In a sense, you’re filling in the numbers in the balance sheet equation: $10 million total assets – $2 million liabilities = $8 million to be identified (either more liabilities or equity) Some businesses depend on debt for more than half of their total capital. In contrast, others have virtually no debt at all. You find many examples of both public and private companies that have no borrowed money. But as a general rule, most businesses carry some debt (and therefore, have interest expense). The debt decision isn’t really an accounting responsibility as such; although once the decision is made to borrow money, the accountant is very involved in recording debt and interest transactions. Deciding on debt is the responsibility of the chief financial officer and chief executive officer of the business. Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business 353 In medium-sized and smaller businesses, the chief accounting officer (controller) may also serve as the chief financial officer. In larger businesses, two individuals hold the top financial and accounting positions. The loan contract between a business and its lender may prohibit the business from distributing profit to owners during the period of the loan. Or the loan agreement may require that the business maintain a minimum cash balance. Generally speaking, the higher the ratio of debt to equity, the more likely a lender is to charge higher interest rates and insist on tougher conditions. That’s because the lender has higher risk that the business may default on the loan. A high debt-to-equity ratio means the company has more debt for every dollar of equity. When borrowing money, the president (or another officer in his or her capacity as an official agent of the business) signs a note payable document to the lender. In addition, the lender may ask the major investors in a smaller, privately owned business to guarantee the note payable of the business as individuals in their personal capacities — and it may ask their spouses to guarantee the note payable as well. The individuals may endorse the note payable, or a separate legal instrument of guarantee may be used. The individuals promise to pay the note if the business can’t make payments. You should definitely understand your personal obligations if you’re inclined to guarantee a note payable of a business. You take the risk that you may have to pay some part or perhaps the entire amount of the loan from your personal assets if the business is unable to honor its obligation. Recognizing the Legal Roots of Business Entities The U.S. legal system enables entities to be created for conducting business activities. These entities are separate and distinct from the individual owners of the business. Business entities have many of the rights of individuals; for example, the rights to own property and enter into contracts. In starting a business venture, one of the first tasks the founders must attend to is to select the type of legal structure to use — which usually requires the services of a lawyer who knows the laws of the state in which the business is organized. A business may have one or more owners. A one-owner business may choose to operate as a sole proprietorship, a limited liability company, or a corporation; a multi-owner business must choose to be a partnership, a limited liability company, or a corporation. The most common type of business is a corporation (although the number of sole proprietorships would be larger if part-time, self-employed people were included in this category). No legal structure is inherently better than another; which one is right for a particular Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 354 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business business is something that the business’s managers and founders need to decide when starting the business. The following discussion focuses on the basic types of legal entities that owners can use for their business. Incorporating a Business The law views a corporation as a real, live person. Like an adult, a corporation is treated as a distinct and independent individual who has rights and responsibilities. (A corporation can’t be sent to jail, but its officers can be put in the slammer if they’re convicted of using the corporate entity for carrying out fraud.) A corporation’s “birth certificate” is the legal form that it files with the Secretary of State of the state in which the corporation is created (incorporated). A corporation must also have a legal name. You’re not allowed to use certain names, such as the State Department of Motor Vehicles. Consult a lawyer when choosing a name for your corporation. The corporate legal form offers several important advantages. A corporation has unlimited life; it stays alive until the shareowners vote to terminate the entity. The ownership interests in a corporation, specifically the shares of stock issued by the corporation, are generally transferable. You can sell your shares to another person or bequeath them in your will to your grandchildren. You don’t need the approval of the other shareholders to transfer ownership of your shares. Each ownership share typically has one vote in the election of directors of a business corporation. In turn, the directors hire and fire the key officers of the corporation. This provides a practical way to structure the management of a business. Just as an adult child is an entity separate from his or her parents, a corporation is separate from its owners. For example, the corporation is responsible for its own debts. Assuming you didn’t cosign for one of your parents’ loans, the bank can’t come after you if your parents default on their loan, and the bank can’t come after you if the corporation you invested money in goes belly up. If a corporation doesn’t pay its debts, its creditors can seize only the corporation’s assets, not the assets of the corporation’s owners. This important legal distinction between the obligations of the business entity and its individual owners is known as limited liability — that is, the limited liability of the owners. Even if the owners have deep pockets, they have no legal exposure for the unpaid debts of the corporation (unless they’ve used the corporate entity to defraud creditors). The legal fence between a corporation and its owners is sometimes called the “corporate shield” because it protects the owners from being held responsible for the debts of the corporation. So when you invest money in a corporation as an owner, you know that the most you can lose is the amount you put in. You may lose every dollar you put in, but the corporation’s creditors can’t reach through the corporate entity to grab your assets to pay off the business’s liabilities. (But to be prudent, you should check with your lawyer on this issue to be sure.) Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business 355 Issuing stock shares When raising equity capital, a corporation issues ownership shares to people who invest money in the business. These ownership shares are documented by stock certificates, which state the name of the owner and the number of shares. (An owner can be an individual, another corporation, or any other legal entity.) The corporation has to keep a register of how many shares everyone owns. Many public corporations use an independent agency to maintain their ownership records. Stock shares are commonly issued in book entry form, which means you get a formal letter (not a stock certificate) attesting to the fact that you own so many shares. Your legal ownership is recorded in the official books, or stock registry of the business. The owners of a corporation are called stockholders because they own stock shares issued by the corporation. The stock shares are negotiable, meaning the owner can sell them at any time to anyone willing to buy them without having to get the approval of the corporation or other stockholders. Publicly owned corporations are those whose stock shares are traded in public markets, such as the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. The stockholders of a private business have the right to sell their shares, although they may enter into a binding agreement restricting this right. For example, suppose you own 20,000 of the 100,000 stock shares issued by the business. You have 20 percent of the voting power in the business (one share, in this case, has one vote). You may agree to offer your shares to the other shareowners before offering the shares to someone outside the present group of stockholders. Or you may agree to offer the business itself the right to buy back the shares. In these ways, the continuing stockholders of the business control who owns the stock shares of the business. Offering different classes of stock shares Before you invest in stock shares, you should ascertain whether the corporation has issued just one class of stock shares. A class is one group, or type, of stock shares all having identical rights; every share is the same as every other share. A corporation can issue two or more classes of stock shares. For example, a business may offer Class A and Class B stock shares, giving Class A stockholders a vote in elections for the board of directors but not granting voting rights to Class B stockholders. State laws generally are liberal in allowing corporations to issue different classes of stock shares. A whimsical example is that holders of one class of stock shares could get the best seats at the annual meetings of the stockholders. But whimsy aside, differences between classes of stock shares are significant and affect the value of the shares of each class of stock. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 356 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Common stock and preferred stock are two classes of corporate stock shares that are fundamentally different. Here are two basic differences: ✓ Fixed dividend amount: Preferred stockholders are promised (though not guaranteed) a certain amount of cash dividends each year, but the corporation makes no such promises to its common stockholders. (The company must generate earnings to pay any type of dividend, including dividends on preferred stock.) Each year, the board of directors must decide how much, if any, cash dividends to distribute to its common stockholders. ✓ Claims on assets: Common stockholders have the most risk. A business that ends up in deep financial trouble is obligated to pay off its liabilities first and then its preferred stockholders. By the time the common stockholders get their turn to collect, the business may have no money left to pay them. In other words, the common shareholders are last in line to make a claim on assets. Neither of these points makes common stock seem very attractive. But consider the following points: ✓ Preferred stock shares are promised a fixed (limited) dividend per year and typically don’t have a claim to any profit beyond the stated amount of dividends. (Some corporations issue participating preferred stock, which gives the preferred stockholders a contingent right to more than just their basic amount of dividends. This topic is too technical to explore further in this book.) ✓ Preferred stockholders may not have voting rights. They may not get to participate in electing the corporation’s board of directors or vote on other critical issues facing the corporation. The advantages of common stock, therefore, are the ability to vote in corporation elections and the unlimited upside potential: After a corporation’s obligations to its preferred stock are satisfied, the rest of the profit it has earned accrues to the benefit of its common stock. Although a corporation may keep some earnings as retained earnings, a common stock shareholder may receive a much larger dividend than a preferred shareholder receives. Here are some important points to understand about common stock shares: ✓ Each stock share is equal to every other stock share in its class. This way, ownership rights are standardized, and the main difference between two stockholders is how many shares each owns. ✓ The only time a business must return stockholders’ capital to them is when the majority of stockholders vote to liquidate the business in part or in total. Otherwise, the business’s managers don’t have to worry about stockholders withdrawing capital. If one investor sells common stock to another shareholder, the company’s capital balance is unchanged. Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business 357 ✓ A stockholder can sell his or her shares at any time, without the approval of the other stockholders. The stockholders of a privately owned business, however, may agree to certain restrictions on this right when they first become stockholders in the business. ✓ Stockholders can put themselves in key management positions, or they may delegate the task of selecting top managers and officers to the board of directors, which is a small group of people selected by the stockholders to set policies and represent stockholders’ interests. Now don’t get the impression that if you buy 100 shares of IBM you can get yourself elected to its board of directors. On the other hand, if you have the funds to buy 100 million shares of IBM, you could very well get yourself on the board. The relative size of your ownership interest is key. If you put up more than half the money in a business, you can put yourself on the board and elect yourself president of the business. That may not be the most savvy business decision, but it’s possible. The stockholders who own 50 percent plus one share constitute the controlling group that decides who’s on the board of directors. Note: The all-stocks-are-created-equal aspect of corporations is a practical and simple way to divide ownership, but its inflexibility can be a hindrance. Suppose the stockholders want to delegate to one individual extraordinary power, or to give one person a share of profit out of proportion to his or her stock ownership. The business can make special compensation arrangements for key executives and ask a lawyer for advice on the best way to implement the stockholders’ intentions. Nevertheless, state corporation laws require that certain voting matters be settled by a majority vote of stockholders. If enough stockholders oppose a certain arrangement, the other stockholders may have to buy them out to gain a controlling interest in the business. (The limited liability company legal structure permits more flexibility in these matters.) Determining market value of stock shares When you consider selling your shares of stock in a company, you probably want to know the market value of each of your shares. There’s a world of difference between owning shares of a public corporation and owning shares of a private corporation. Public means an active market exists for the stock shares of the business; the shares are liquid. You can convert your shares into cash in a flash by calling your stockbroker or going online to sell them. You can check a daily financial newspaper — such as The Wall Street Journal — for the current market prices of many large publicly owned corporations. Or you can go to one of many websites (such as finance.yahoo.com) that provide current market prices. But stock shares in privately owned businesses aren’t publicly traded, so you need to take a different approach to determine the value of your shares. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 358 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Stockholders of a private business rarely worry about putting a precise market value on their shares — until they’re serious about selling their shares or something else happens that demands putting a value on the shares. When you die, the executor of your estate has to put a value on the shares you own for estate tax purposes. If you divorce your spouse, a value is needed for the stock shares you own, as part of the divorce settlement. When the business itself is put up for sale, a value is put on the business; dividing this value by the number of stock shares issued by the business gives the value per share. Other than during events like these, which require that a value be put on the stock shares, the shareowners of a private business get along quite well ­without knowing a definite value of their shares. This doesn’t mean they have no idea regarding the value of their business and what their shares are worth. They read the financial statements of their business, so they know its profit performance and financial condition. In the backs of their minds they should have a reasonably good estimate regarding how much a willing buyer may pay for the business and the price they would sell their shares for. So even though they don’t know the exact market value of their stock shares, they’re not completely in the dark about that value. Generally speaking, the value of ownership shares in a private business depends on the recent profit performance and the current financial condition of the business, as reported in its latest financial statements. The financial statements may have to be trued up, as they say, to bring some of the historical cost values in the balance sheet up to current replacement values. For more about performing business valuations, see Book V, Chapter 1. Business valuation is highly dependent on the specific circumstances of each business. The present owners may be very eager to sell, and they may be willing to accept a low price instead of taking the time to drive a better bargain. The potential buyers of the business may see opportunities that the present owners don’t see or aren’t willing to pursue. Even Warren Buffett, who has a well-deserved reputation for knowing how to value a business, admits that he’s made some real blunders along the way. Keeping alert for dilution of share value Watch out for developments that cause a dilution effect on the value of your stock shares — that is, that cause each stock share to drop in value. Specifically, dilution means that your earnings per common stock share have declined. If this earnings per share figure declines, investor interest in the common stock also is likely to decline. The most basic level of measuring earnings per share involves common stock, as explained in this section. Chapter 1: Incorporating Your Business 359 Sometimes the dilution effect may be the result of a good business decision, so even though your earnings per share decreases in the short term, the long-term profit performance of the business (and, therefore, your value of the common stock shares) may benefit. But you need to watch for these developments closely. The following situations cause a dilution effect: ✓ Issuing additional shares: A business issues additional stock shares at the going market value but doesn’t really need the additional capital — the business is in no better profit-making position than it was before issuing the new stock shares. For example, a business may issue new stock shares in order to let a newly hired chief executive officer buy them. The immediate effect may be a dilution in the value per share. Total earnings are the same, but those earnings are spread over more common stock shares. Over the long term, however, the new CEO may turn the business around and lead it to higher levels of profit that increase the stock’s value. ✓ Offering additional shares at a discount: A business issues new stock shares at a discount below its stock shares’ current value. For example, the business may issue a new batch of stock shares at a price lower than the current market value to employees who take advantage of an employee stock-purchase plan. Issuing stock shares — at any price — has a dilutive effect on the market value of the shares. But in the grand scheme of things, the stock-purchase plan may motivate its employees to achieve higher productivity levels, which can lead to superior profit performance of the business. Finally, keep in mind that issuing shares at a discount means that you don’t raise as much capital for the business. Now here’s one for you: The main purpose of issuing additional stock shares is to deliberately dilute the market value per share. For example, a publicly owned corporation doubles its number of shares by issuing a two-for-one stock split. Each shareholder gets one new share for each share presently owned, without investing any additional money in the business. As you would expect, the market value of the stock drops in half — which is exactly the purpose of the stock split. The lower stock price may attract more investors. After all, 100 shares of a $20 stock cost less than 100 shares of a $40 stock. Note that a stock split doesn’t change the total market value of the company. When the number of shares is doubled in a two-for-one stock split, the value of each share is cut in half. As a result, the total market value stays the same. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 360 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Recognizing conflicts between stockholders and managers Stockholders are primarily concerned with the profit performance of the business; the dividends they receive and the value of their stock shares depend on it. Managers’ jobs depend on living up to the business’s profit goals. But whereas stockholders and managers have the common goal of optimizing profit, they have certain inherent conflicts of interest: ✓ Manager compensation: The more money that managers make in wages and benefits, the less stockholders see in bottom-line net income. Stockholders obviously want the best managers for the job, but they don’t want to pay any more than they have to. Most public business corporations establish a compensation committee consisting of outside directors that sets the salaries, incentive bonuses, and other forms of compensation of the top-level executives of the organization. An outside director is one who has no management position in the business and who, therefore, should be more objective and shouldn’t be beholden to the chief executive of the business. This scenario is good in theory, but it may not work out all that well in practice — particularly if the top-level executive of a large public business has the dominant voice in selecting the people to serve on its board of directors. Being a director of a large public corporation is a prestigious position, to say nothing of the annual fees that can be fairly substantial at many corporations. ✓ Control over the business: The question of who should control the business — managers who are hired for their competence and are intimately familiar with the business, or stockholders who may have no experience relevant to running this business but whose money makes it tick — can be tough to answer. Ideally, the two sides respect each other’s contributions to the business and use this tension constructively. Of course, the real world is far from ideal, and in some companies, managers control the board of directors rather than the other way around. As an investor, be aware of these issues and how they affect the return on your investment in a business. If you don’t like the way your business is run, you can sell your shares and invest your money elsewhere. (However, if the business is privately owned, there may not be a ready market for its stock shares, which puts you between a rock and a hard place.) Chapter 2 Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business In This Chapter ▶ Partnering with others in business ▶ Gaining legal protections with an LLC ▶ Looking out for number one in a sole proprietorship ▶ Considering the tax ramifications of your choices F orming a business can be easy as pie or extremely complicated, depending on the type of business entity being created. If you’re flying solo, you’re a business unto yourself and really don’t need to do anything to establish yourself as a sole proprietorship. Unless you say otherwise, the IRS considers your business a sole proprietorship. With a little extra effort, you can establish your business as a partnership, to share duties and profits among owners, or create a limited liability company (LLC) to provide your business with some extra legal protection. With a little more effort, and a lot more paperwork, you can establish your business as a full-fledged corporation. This chapter presents the ABCs of the three types of business entities: partnerships, LLCs, and corporations. First, you get a brief overview of sole proprietorships and partnerships. Then you find out all you need to know about the different types of corporations — C corporations and S corporations — and the tax considerations for each. Differentiating between Partnerships and Limited Liability Companies Suppose you’re starting a new business with one or more other owners, but you don’t want it to be a corporation. You can choose to create a partnership or a limited liability company (LLC ), which are the main alternatives to the corporate form of business. 362 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business A partnership is also called a firm. You don’t see this term used to refer to a corporation or limited liability company nearly as often as you do to a partnership. The term firm connotes an association of a group of individuals working together in a business or professional practice. Compared with the relatively rigid structure of corporations, the partnership and LLC forms of legal entities allow the division of management authority, profit sharing, and ownership rights among owners to be very flexible. The following sections highlight the key features of these two legal structures. Partnerships Partnerships avoid the double-taxation feature that corporations are subject to (see “Choosing the Right Legal Structure for Income Tax,” later in this chapter for details), because all profits and losses “pass through” the business to its partners. Partnerships also differ from corporations with respect to owners’ liability: ✓ General partners are subject to unlimited liability. If a business can’t pay its debts, its creditors can reach into general partners’ personal assets. General partners have the authority and responsibility to manage the business. They’re roughly equivalent to the president and other highlevel managers of a business corporation. The general partners usually divide authority and responsibility among themselves, and often they elect one member of their group as the senior general partner or elect a small executive committee to make major decisions. ✓ Limited partners escape the unlimited liability that the general partners have hanging around their necks. Limited partners aren’t responsible, as individuals, for the liabilities of the partnership entity. These junior partners have ownership rights to the business’s profit, but they don’t generally participate in the high-level management of the business. A partnership must have one or more general partners; not all partners can be limited partners. Many large partnerships copy some of the management features of the corporate form — for example, a senior partner who serves as chair of the general partners’ executive committee acts in much the same way as the chair of a corporation’s board of directors. In most partnerships, an individual partner can’t sell his interest to an outsider without the consent of all the other partners. You can’t just buy your way into a partnership; the other partners have to approve your joining the partnership. In contrast, you can buy stock shares and thereby become part owner of a corporation without the approval of the other stockholders. Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business 363 Limited liability company (LLC) The LLC is an alternative type of business entity. An LLC is like a corporation regarding limited liability, and it’s like a partnership regarding the flexibility of dividing profit among the owners. An LLC can elect to be treated either as a partnership or as a corporation for federal income tax purposes. Consult a tax expert if you’re facing this choice. The key advantage of the LLC legal form is its flexibility, especially regarding how profit and management authority are determined. For example, an LLC permits the founders of the business to put up, say, only 10 or 20 percent of the money to start a business venture but to keep all management authority in their hands. The other investors share in profit but not necessarily in proportion to their invested capital. LLCs have a lot more flexibility than corporations, but this flexibility can have a downside. The owners must enter into a very detailed agreement that spells out the division of profit, the division of management authority and responsibility, their rights to withdraw capital, and their responsibilities to contribute new capital as needed. These schemes can get very complicated and difficult to understand, and they may end up requiring a lawyer to untangle them. If the legal structure of an LLC is too complicated and too far off the beaten path, the business may have difficulty explaining itself to a lender when applying for a loan, and it may have difficulty convincing new shareholders to put capital into the business. Limiting liability: Professional corporations and LLPs Professional partnerships — physicians, CPAs, lawyers, and so on — may choose to become professional corporations (PCs), which are a special type of legal structure that state laws offer to professionals who otherwise would have to operate under the specter of unlimited partnership liability. States also permit limited liability partnerships (LLPs) for qualified professionals (such as doctors, lawyers, CPAs, and dentists), in which all the partners have limited liability. These types of legal entities were recently created in reaction to large damage awards in malpractice lawsuits against partners. The professionals pleaded for protection from the unlimited liability of the partnership form of organization, which they had traditionally used. Until these types of legal entities came along, the code of professional ethics of the various professions required that practitioners operate as a partnership (or as sole practitioners/ proprietors). Today, almost all professional associations are organized as PCs or LLPs. They function very much as partnerships do but without the unlimited liability feature, which is like having the best of both worlds. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 364 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Understanding how partnerships and LLCs distribute profits A partnership treats salaries paid to partners (at least to its general partners) as distributions from profit. In other words, profit is determined before the deduction of partners’ salaries. LLCs are more likely to treat salaries paid to owner-managers as an expense (as a corporation does). Accounting for compensation and services provided by the owners in an LLC and the partners in a partnership gets rather technical and is beyond the scope of this book. The partnership or LLC agreement specifies how to divide profit among the owners. Whereas owners of a corporation receive a share of profit directly proportional to the number of common stock shares they own, a partnership or LLC doesn’t have to divide profit according to how much each owner invested. Invested capital is only one of three factors that generally play into profit allocation in partnerships and LLCs: ✓ Treasure: Owners may be rewarded according to how much of the treasure — invested capital — they contributed. So if Jane invests twice as much as Joe, her cut of the profit may be twice as much as his. ✓ Time: Owners who invest more time in the business may receive more of the profit. Some partners or owners, for example, may generate more billable hours to clients than others, and the profit-sharing plan reflects this disparity. Some partners or owners may work only part-time, so the profit-sharing plan takes this factor into account. ✓ Talent: Regardless of capital and time, some partners bring more to the business than others. Maybe they have better business contacts, or they’re better rainmakers (they have a knack for making deals happen), or they’re celebrities whose names alone are worth a special share of the profit. However their talent impacts the business, they contribute much more to the business’s success than their capital or time suggests. A partnership needs to maintain a separate capital (ownership) account for each partner. The total profit of the entity is allocated into these capital accounts, as spelled out in the partnership agreement. The agreement also specifies how much money each partner can withdraw from his or her capital account. For example, partners may be limited to withdrawing no more than 80 percent of their anticipated share of profit for the coming year, or they may be allowed to withdraw only a certain amount until they’ve built up their capital accounts. The capital that remains in the partnership is used to operate the business. Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business 365 Going It Alone: Sole Proprietorships A sole proprietorship is basically the business arm of an individual who decides not to do business as a separate legal entity (as a corporation, partnership, or LLC). It’s the default when you don’t establish a legal entity. Describing a sole proprietorship A sole proprietorship isn’t a separate entity; it’s like the front porch of a house — attached to the house but a separate and distinct area. You may be a sole proprietor of a business without knowing it! An individual may do house repair work on a part-time basis or be a full-time barber who operates on his own. Both are sole proprietorships. Anytime you regularly provide services for a fee, sell things at a flea market, or engage in any business activity whose primary purpose is to make profit, you’re a sole proprietor. If you carry on business activity to make profit or income, the IRS requires that you file a separate Schedule C “Profit or Loss From Business” with your annual individual income tax return. Schedule C summarizes your income and expenses from your sole proprietorship business. Understanding liability and financial reporting As the sole owner (proprietor), you have unlimited liability, meaning that if your business can’t pay all its liabilities, the creditors to whom your business owes money can come after your personal assets. Many part-time entrepreneurs may not know this or may put it out of their minds, but this is a big risk to take. Some part-time business consultants operate their consulting businesses as sole proprietorships. If they’re sued for giving bad advice, all their personal assets are at risk — though they may be able to buy malpractice insurance to cover these losses. Obviously, a sole proprietorship has no other owners to prepare financial statements for, but sole proprietors should still prepare these statements to know how their businesses are doing. Banks usually require financial statements from sole proprietors who apply for loans. One other piece of advice for sole proprietors: Although you don’t have to separate invested capital from retained earnings as corporations do, you should still keep these two separate accounts for owners’ equity — not only for the purpose of tracking the business but also for the benefit of any future buyers of the business. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 366 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Choosing the Right Legal Structure for Income Tax When deciding which type of legal structure is best for securing capital and managing their business, owners should also consider the income tax factor. They should know the key differences between the two alternative kinds of business entities from an income tax point of view: ✓ Taxable-entity, C corporations: These corporations are subject to income tax on their annual taxable income. Plus, their stockholders pay a second income tax on cash dividends that the business distributes to them from profit, making C corporations and their owners subject to double taxation. The owners (stockholders) of a C corporation include in their individual income tax returns the cash distributions from the after-tax profit paid to them by the business. ✓ Pass-through entities — partnerships, S corporations, and LLCs: These entities don’t pay income tax on their annual taxable income; instead, they pass through their taxable income to their owners, who pick up their shares of the taxable income on their individual tax returns. Pass-through entities still have to file tax returns with the IRS, even though they don’t pay income tax on their taxable income. In their tax returns, they inform the IRS how much taxable income is allocated to each owner, and they send each owner a copy of this information to include with his or her individual income tax return. Most LLCs opt to be treated as pass-through entities for income tax purposes. But an LLC can choose instead to be taxed as a C corporation and pay income tax on its taxable income for the year, with its individual shareholders paying a second tax on cash distributions of profit from the LLC. Why would an LLC choose double taxation? Keep reading. The following sections explain the differences between the two types of legal structures in terms of income taxes. These examples assume that the business uses the same accounting methods in preparing its income statement that it uses for determining its taxable income — a realistic assumption, though there are many technical exceptions to this general rule. To keep this discussion simple, the examples focus on differences in federal income tax, which is much larger than any state income tax that may apply. C corporations A corporation that doesn’t qualify as an S corporation (explained in the next section) or that doesn’t elect this alternative if it does qualify, is referred to as a C corporation in the tax law. A C corporation is subject to federal income tax Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business 367 based on its taxable income for the year, keeping in mind that a host of special tax credits (offsets) could reduce or even eliminate the amount of income tax a corporation has to pay. Suppose a business is taxed as a C corporation. Its abbreviated income statement for the year just ended is shown in Figure 2-1. (See Book IV, Chapter 2 for more about income statements.) Figure 2-1: Abbreviated annual income statement for a C corporation. Book VI ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Given the complexity and changing nature of the income tax law, the following discussion avoids going into details about income tax form numbers and the income tax rates used to determine the income tax amounts in each example. By the time you read this section, the tax rates probably will have changed, but the following discussion does use realistic income tax numbers. Refer to the C corporation income statement example again (Figure 2-1). Based on its $2.2 million taxable income for the year, the business owes $748,000 income tax — assuming a 34 percent tax rate for this level of corporate taxable income. (Most of the annual income tax should have been paid in installments to the IRS before year-end.) The income tax is a big chunk of the business’s hard-earned profit before income tax. Finally, don’t forget that net income means bottom-line profit after income tax expense. Being a C corporation, the business pays $748,000 income tax on its profit before tax, which leaves $1,452,000 net income after income tax. Suppose the business distributes $500,000 of its after-tax profit to its stockholders as their just rewards for investing capital in the business. The stockholders include the cash dividends as income in their individual income tax returns. Assuming that all the individual stockholders have to pay income tax on this additional layer of income, as a group they would pay $75,000 in income tax to Uncle Sam (based on a 15 percent rate on corporate dividends). A business corporation isn’t legally required to distribute cash dividends, even when it reports a profit and has good cash flow from its operating activities. But paying zero cash dividends may not go over well with all the stockholders. If you’ve persuaded your Aunt Hilda and Uncle Harry to invest some of their money in your business, and if the business doesn’t pay any cash dividends, they may be very upset. Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 368 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business S corporations A business that meets the following criteria (and certain other conditions) can elect to be treated as an S corporation: ✓ It has issued only one class of stock. ✓ It has 100 or fewer people holding its stock shares. ✓ It has received approval for becoming an S corporation from all its stockholders. Suppose that the business example presented in the previous section qualifies and elects to be taxed as an S corporation. Its abbreviated income statement for the year is shown in Figure 2-2. An S corporation pays no income tax itself, as you see in this abbreviated income statement. But it must allocate its $2.2 million taxable income among its owners (stockholders) in proportion to the number of stock shares each owner holds. If you own one-tenth of the total shares, you include $220,000 of the business’s taxable income in your individual income tax return for the year regardless of whether you receive any cash distribution from the profit of the S corporation. That’s likely to push you into a high income tax rate bracket. Figure 2-2: Abbreviated annual income statement for an S corporation. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Considering the pros and cons When its stockholders read the bottom line of this S corporation’s annual income statement, it’s a good news/bad news thing. The good news is that the business made $2.2 million net income and doesn’t have to pay any corporate income tax on this profit. The bad news is that the stockholders must include their respective shares of the $2.2 million on their individual income tax returns for the year. The total amount of individual income tax that would be paid by the stockholders as a group is tough to pin down. Each investor’s tax situation is different. An S corporation could distribute cash dividends to its stockholders, which would provide them with the money to pay the income tax on their shares of the company’s taxable income. Chapter 2: Choosing a Legal Structure for a Business 369 Choices regarding taxation The main tax question concerns how to minimize the overall income tax burden on the business entity and its stockholders. Should the business be an S corporation (assuming it qualifies) and pass through its taxable income to its stockholders, which generates taxable income to them? Or should the business operate as a C corporation (which always is an option) and have its stockholders pay a second tax on dividends paid to them in addition to the income tax paid by the business? Here’s another twist: In some cases, stockholders may prefer that their S corporation not distribute any cash dividends. They’re willing to finance the growth of the business by paying income tax on the taxable profits of the business — without taking a distribution from the S corporation. This strategy relieves the business of making cash distributions to pay the income tax. Many factors come into play in choosing between an S and C corporation. Choosing the best option isn’t easy. Consult a CPA or other tax professional before making your final decision. Partnerships and LLCs The LLC type of business entity borrows some features from the corporate form and some features from the partnership form. The LLC is neither fish nor fowl; it’s an unusual blending of features that have worked well for many business ventures. A business organized as an LLC has the option to be a pass-through tax entity instead of paying income tax on its taxable income. A partnership doesn’t have an option; it’s a pass-through tax entity by virtue of being a partnership. Following are the key income tax features of partnerships and LLCs: ✓ Pass-through tax entity: A partnership is a pass-through tax entity, just like an S corporation. When two or more owners join together and invest money to start a business and don’t incorporate and don’t form an LLC, the tax law treats the business as a de facto partnership. Most partnerships are based on written agreements among the owners, but even without a formal, written agreement, a partnership exists in the eyes of the income tax law (and in the eyes of the law in general). ✓ Making a choice: An LLC has the choice between being treated as a pass-through tax entity and being treated as a taxable entity (like a C corporation). All you need to do is check off a box in the business’s tax return to make the choice. Many businesses organize as LLCs because they want to be pass-through tax entities (although the flexible structure of the LLC is also a strong motive for choosing this type of legal organization). Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 370 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business The partners in a partnership and the shareholders of an LLC pick up their shares of the business’s taxable income in the same manner as the stockholders of an S corporation. They include their shares of the entity’s taxable income in their individual income tax returns for the year. For example, suppose your share of the annual profit as a partner, or as one of the LLC’s shareholders, is $150,000. You include this amount in your personal income tax return. Summing up the legal structure issue Choosing the best legal structure for a business is a complicated affair that goes beyond just the income tax factor. You need to consider many other factors, such as the number of equity investors who will be active managers in the business, state laws regarding business legal entities, ease of transferring ownership shares, and so on. After you select a particular legal structure, changing it later isn’t easy. Asking the advice of a qualified professional is well worth the money and can prevent costly mistakes. Sometimes the search for the ideal legal structure that minimizes income tax and maximizes other benefits is like the search for the Holy Grail. Business owners shouldn’t expect to find the perfect answer — they have to make compromises and balance the advantages and disadvantages. In its external financial reports, a business has to make clear which type of legal entity it is. The type of entity is a very important factor to the lenders and other creditors of the business, and to its owners of course. One other thing bears mentioning here. In this Internet age, many people form their own entities, whether it be a corporation or an LLC, through the assistance of online software and websites, with the assumption that they now have the limited liability asset protection afforded that entity. However, forming an entity and keeping it legal can be a complex task, and every state has different rules. One little misstep can make it easy for the corporate shield to be pierced in the event of a lawsuit. Hire a competent business attorney to make sure you’re protected. Consider it a form of insurance. Chapter 3 Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash In This Chapter ▶ Examining the four basic parts of a business plan ▶ Creating a business plan, from idea through development ▶ Including reliable third-party info in your business plan ▶ Remembering to use data that’s complete, accurate, reliable, and timely W hether a business is a start-up or a mature operation, a clear and concise business plan is an essential tool to assist businesses with securing cash, managing their operations, and protecting their interests. This chapter provides the basic understanding and tools needed to develop a viable business plan, which is translated into economic value via the production of financial forecasts and projections. The planning process described in this chapter includes numerous elements. This chapter discusses obtaining current market information (on the potential demand for a new product and what price the market will support) and evaluating personnel resources (to ensure that proper professionals are available to support a business). Another issue addressed is determining how great operational constraints (such as manufacturing space availability or environmental regulations) may be in terms of expanding into a new location. Outlining the Basic Business Plan All too often companies proceed with strategies anchored in the past instead of evaluating and investigating the markets in which they operate and looking to the future. Management’s reason for doing something a certain way often sounds like this: “We’ve always done it like that” or “This is how the industry has operated for the past umpteen years.” Developing a business plan compels management to be more future focused. 372 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business A solid business plan should represent management’s foundation and justification for birthing, growing, operating, and/or selling a business based on present economic and market conditions and future projections. Without a solid plan, a business is destined to operate by trial and error — an approach that often leads to failure. Business plans come in a variety of shapes, sizes, forms, and structures and often take on the characteristics of the business founder(s). It may resemble its creators by emphasizing certain traits or areas of expertise the founders have. For instance, a type-A personality may use a number of bold adjectives to describe the massive, huge, unlimited, exceptional potential of a future market opportunity. As for unique areas of expertise, different sections of the business plan may be developed in depth, whereas other sections may be presented in quasi-summary format because the needed information isn’t readily available (for presentation). Herein lies the first lesson of developing a business plan: The business plan should be built from the outside looking in so that any reasonable party can clearly and quickly understand the business concept. The business plan can come in a multitude of formats and include all types of information, data, graphs, charts, analyses, and more. The basis of every business plan, however, is in four main sections, as explained in the following sections. The executive summary The executive summary is a brief overview of the business concept in terms of the market opportunity, the operational logistics required to bring a product and/or service to market, the management team that’s going to make it happen, the amount of capital needed to execute the plan, and the potential economic return. This section of the business plan is really nothing more than a condensed summary of the entire business concept, presented in a neat and tidy overview of five pages or (hopefully) fewer. The general idea is that the executive summary should capture the critical content of each of the three primary areas of the business plan in an efficient and easy to digest manner. Although the meat of the business plan resides in the remainder of the document, this section is the most critical in terms of attracting interest from capital sources and/or management. The reader of the business plan must be able to conceptualize, understand, and justify the business concept from the information presented in the executive summary. This section must gain the reader’s interest, generate some type of excitement, and move him with a sense of urgency to pursue the business opportunity at hand. Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash 373 Although the executive summary is the first section of the business plan, consider writing it last, so you can draw information from the other sections of the plan. If you write it first, you’re probably going to need to rewrite it later to make it consistent with information in the remaining sections. The market assessment The market assessment substantiates the present or future need for a product or service that’s not being met in the current marketplace. Although this section of the business plan isn’t necessarily more important than the others, it takes precedence because without a market for the product or service, a business has no reason to provide it. You support the business concept by quantifying the size of the market in coordination with qualifying the market need, but that step is only half the battle (and often the easier of the two halves). Beyond providing information and supporting data on the market size, characteristics, and trends, the market assessment must also present a clear understanding of the business’s competitive niche, target market, and specific marketing strategies. Identifying the specific niche and target market and developing an effective marketing strategy to capitalize on the opportunity present is often more challenging and critical to the future success of the business venture. And to top it all off, locating reliable and meaningful data essential to supporting your conclusions on the market opportunity can often be difficult. All marketing sections should include a summary of the competition that savvy entrepreneurs or business managers can use to their advantage in several ways: ✓ By including an overview of the competition, the business establishes credibility with the readers (because it indicates that you’ve done your homework). ✓ By reading in-depth competitor assessments, managers may identify weaknesses in competitors’ plans that can be exploited. ✓ By evaluating competitors’ strengths and weaknesses, managers can better understand business risks. For more about competitive analysis, check out Competitive Intelligence For Dummies by Jim Underwood (Wiley). Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 374 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business The operational overview Following the market segment of the business plan is a well-developed company operating overview. This segment of the business plan addresses a number of operational issues, including personnel requirements, technological needs, locations (for offices, production/manufacturing, warehouses/ distribution centers, and so on), company infrastructure requirements, international considerations, professional/expert counsel resources, and the like. This segment drives various business-operating elements in terms of the resources needed to implement and execute the business plan. For example, if a company is planning on expanding into new foreign markets where the local government still “influences” the distribution channels, then the operating segment needs to address how the product will be distributed and which international partners will be essential to the process. Business plans often dedicate a large portion of the operational overview to providing an overview of the management team. The overview covers the members’ past credentials as well as their responsibilities with the new business concept. The market may be ripe and capital plentiful, but without a qualified management team, the business concept will sink more times than not. In today’s challenging economic environment, management qualifications and credibility have taken on an entirely new level of importance, given the heightened sensitivity to management accountability and transparency. The management team responsible for executing the business plan is a key component of the business plan. Initially, financing and capital sources are lured in by business plans and may turn over any concept in the plan to a slew of professionals for further due diligence, reviews, evaluations, and critique. For example, if a capital source has concerns over the technological basis within a biomedical company, then medical- or technology-based professionals can be brought in to complete additional research and analysis and either approve or dismiss the idea. However, the management team standing behind the business plan and its execution is really what the capital and financing sources invest in. The integrity, experience, determination, passion, commitment, and competence of the management team are of utmost importance. Any weakness in this area is likely to drive away investors and their capital. The financial summary: Performance and required capital In a sense, the financial summary brings all the elements of the business plan together from an accounting and financing perspective. In the financial summary, financial forecasts project the anticipated economic performance of Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash 375 the business concept based on the information and data presented earlier in the business plan: ✓ The market segment drives the revenue portion of the forecasts, because the information accumulated and presented there substantiates items such as potential unit sales growth (in relation to market size), pricing, and revenue sources by product and service. ✓ The operational overview drives the expense element of the forecast, because it addresses the business cost structure in terms of personnel, assets, company infrastructure, and so on. You can look at the financial summary as a projected financial report that includes a forecasted income (profit and loss) statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. All this information quantifies the capital required to execute the business plan. Developing a Business Plan Accounting is more art than science, especially when it comes to developing a business plan. Nobody can tell you precisely what to put into your business plan, but the following sections provide valuable guidance and tools to explain the process and get you started. Business plans shouldn’t be reserved for new companies just starting out or an existing business looking at launching new products. All companies should implement formal business-planning processes to ensure that their business interests are properly managed and protected. Recognizing the evolution of business plans: BOTE, WAG, and SWAG The real start of developing any business plan is coming up with the initial concept, idea, or thought. Over time, the plan evolves usually in line with the following progression: ✓ BOTE: Back of the envelope ✓ WAG: Wild-ass guess ✓ SWAG: Scientific wild-ass guess These acronyms on developing business plans and projections are presented somewhat in jest, but at the same time, they do help you understand the evolution of a business plan and projection model from how an idea is born to how it’s communicated in financial language to various parties. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 376 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Whether you apply these acronyms and follow this logic or rely on another creation and development cycle, the same key concept holds. Business plans and projection models should continue to evolve, improve, and strengthen over time as more and more effort is invested to bring the idea to life. BOTE BOTE usually represents the very first financial projection developed for a business plan: back of the envelope (or back of a napkin at a restaurant). Yes, even the majority of the most astute and experienced business professionals and entrepreneurs can attest to jotting down the basic concepts, needs, potential sales, costs, and profits of a business idea or concept on a random piece of paper (or with a simple mobile communication device application). Sometimes you need to get it out of your head and down in writing just to see whether it makes any sense to begin with. You’d be amazed at how often BOTE estimates are used. WAG If the idea passes the BOTE test, the next step in the evolution of the planning process is the ever-present WAG (or wild-ass guess). The WAG is somewhat more sophisticated than the BOTE in that it tends to incorporate more thought and some basic research. WAGs are usually produced by using software tools such as Microsoft Excel and incorporate the basic economic structure of the business, starting with sales and then moving through the remainder of the income statement by capturing costs of sales, operating expenses, and overhead or general and administrative costs. You can then draw two simple conclusions: ✓ How profitable the idea will be ✓ More importantly, how much capital or cash the idea needs in order to achieve success These conclusions aren’t overly sophisticated, but they’re an early attempt to assign numbers to the idea. SWAG If your idea has passed both the BOTE and WAG stages, congratulations are in order because you now can use the much more powerful tool, SWAG (scientific wild-ass guess) to further the development of your business plan. In other words, the business plan and supporting projection model are actually getting some serious attention and logical consideration. You can begin to use external sources (or third-party data/information) to actually start to substantiate and corroborate the idea’s potential. The first real form to the business plan and projection models are taking shape. You may be incorporating the use of technology tools to draft the business plan (for example, Microsoft Word), to build version 1.0 of the projection model (perhaps with Microsoft Excel), and to begin to prepare a presentation to summarize the plan (for example, with Microsoft PowerPoint). Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash 377 Getting the process going After the business’s executive management teams or new company founders have decided that the concept for the new business endeavor has merit (which is by no means a small task), you can begin drafting the business plan. You can prepare a draft by following four simple steps: 1. Delve into historical business information. In order to start the budgeting process, you should have a good understanding of your company’s prior financial and operating results. Review as much history as is available and relevant to the current idea, whether it stretches back three months, one year, five years, or longer. Of course if you’re planning an entirely new business, the availability of internal historical information is limited, but plenty of external information is usually available from similar businesses. Remember that although the history of a company may provide a basic foundation on which to develop a budget, by no means is it an accurate predictor of the future. 2. Involve key management. You must ensure that all key management team members are involved in the planning process, covering all critical business functions, to produce a reliable projection. The accounting and financial departments actively participate in the planning (and rightfully so, as these are the people who understand the numbers the best) and they produce the final forecast. Critical business data comes from numerous parties and sources, and all of that data must be included in the planning process to produce the most reliable projections possible. 3. Gather reliable data. The availability of quality market, operational, and accounting data represents the basis of the budget. A good deal of this data often comes from internal sources. For example, salespeople may pick up on customer needs that aren’t being met in the marketplace or a company executive may hear about pending legislation that’s likely to lead to new opportunities. With this information and some research, you can begin to determine sales volumes, personnel levels, wages rates, commission plans, and so on. The internal information is certainly of value, but it represents only half of what you need, because external information and data are just as critical. Having access to quality and reliable external third-partyproduced information is absolutely essential to the overall business planning process and the production of reliable forecasts. Market forces and trends that aren’t apparent in internal data may be occurring and set to impact your new business, product, or service over the next 24 months. (For more about gathering information from external sources, see “Incorporating Third-Party Information into Your Plan” later in this chapter.) Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 378 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 4. Coordinate the start of the planning process. Most companies tend to start the planning process for the next year in the fourth quarter of their current calendar year. This way, they have access to recent financial results on which to support the budgeting process moving forward. The closer the date of the financial data is to when the projection is made, the more detailed the information and results being produced. If you prepare a budget for the coming fiscal year, then you can reasonably include monthly financial statement forecasts (with more detailed support available). Looking two or three years out, you can produce quarterly financial statement projections (with more summarized assumptions), and so on. When preparing your company’s budgets, try to use information that’s as complete, accurate, reliable, and timely as possible. Though you can’t be 100 percent sure about the data and information gathered for your plan (because by definition, you’re attempting to predict the future with a projection), with proper resources (including appropriate internal management, external subject-matter experts or consultants, and allocating financial resources to secure critical information that’s not readily available or free), you can avoid large information “black holes.” What worked two years ago may not provide management with the necessary information today on which to make appropriate business decisions. Just ask any retailer that formerly relied on brick-and-mortar stores and print-based advertising campaigns how the Internet and e-commerce have reshaped their business models. Although management has put forth the effort to restructure the company’s operations in a changing market environment, a plan based on an old projection model with outdated assumptions doesn’t capture the essence of the new market realities. Remember, the planning process represents a living, evolving thing that must constantly be updated and adapted to changing market conditions. Analyzing and streamlining information with SWOT and KISS If you’re not careful, the data-accumulation process can engulf the entire planning effort. And if you get too much data, you can’t digest it or draw any type of meaningful conclusion. Fortunately two simple but powerful planning tools are available to make sense of the data and present it in an easily accessible format: SWOT and KISS. The SWOT analysis Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats: A SWOT analysis is an effective planning and budgeting tool used to keep businesses focused on critical issues that may lead to wonderful successes or horrible failures. The SWOT Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash 379 analysis should be as comprehensive as possible and capture both relevant information for the specific idea as well as incorporating more broad-based data about the company, the industry, and the competition. The simple SWOT analysis (or matrix) in Figure 3-1 provides a better understanding of how it works. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Figure 3-1: A simple SWOT analysis. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. A SWOT analysis is usually broken down into a matrix containing four segments. Two of the segments are geared toward positive attributes (for instance, a company’s strengths and its opportunities) and two are geared toward negative attributes (weaknesses and threats). In addition to illustrating these categories, Figure 3-1 makes reference to the terms internal versus external. This distinction highlights the fact that certain attributes tend to come from internal company sources (namely, strengths and weaknesses) and other attributes from external sources (typically opportunities and threats). 380 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Used correctly, a SWOT analysis not only provides invaluable information to support the planning process but also (and more importantly) helps identify the type of management a business has in place. The success of any business plan hinges on having the right leaders driving the bus to take the opportunity from a concept to reality. A frontline manager in need of direction can assist with this process but generally isn’t qualified to lead. You need a bona fide businessperson to lead the charge. A variety of different parties may conduct SWOT analysis. In a larger or wellestablished business, the management team assigned to complete a project or pursue an opportunity may take the lead. The SWOT analysis is then evaluated and interpreted by the company’s executives, who consider whether it’s viable and whether the right people are in place. On the other hand, two founders just starting a business may complete a SWOT analysis. When the SWOT is complete, company executives may ask a third-party consultant to review the document. An outside expert can provide management with an unbiased view on whether the analysis is realistic. Remember to KISS You know what KISS stands for: Keep it simple, stupid. Used in the marketing world for years, the concept of KISS also applies to business plans. When developing a business plan, be as clear and direct as possible. Summarize the data, use images and graphs wherever necessary to illustrate points, and present clear directives for moving forward. And follow the credo “When in doubt, leave it out.” That is, if information isn’t essential to making a point, omit it. Don’t make the end user of the business plan sift through it to extract meaning. If you’re an executive or owner of a business, you must be able to understand the big picture and the key economic drivers of your company’s success in order to prepare proper business plans, strategies, and, ultimately, forecasts. The ability to understand and positively affect the key economic drivers of your business and empower the management team to execute the business plan represents the end game. Getting lost in excessive amounts of detail (“Why did you spend an extra $500 on the trip to Florida?”) generally isn’t the best use of senior management’s time, because every level of detail adds more and more complexity to the plan, which can get overwhelmed with TMI (too much information). Incorporating Third-Party Information into Your Plan When building reliable and credible business plans, don’t underestimate the importance of accumulating data and information from reliable independent third parties (including various trade and industry sources). The following sections explain how and where to gather the information you need and the importance of starting with solid data. Chapter 3: Drawing Up a Business Plan to Secure Cash 381 Gathering the info Not so long ago, valuable third-party market, industry, and technological information was gathered via archaic methods such as researching in a library, subscribing to trade journals and magazines, and attending seminars or educational trade shows. Today, most of the information you need is available electronically over the World Wide Web, which has improved the efficiency of accumulating information significantly. Most industries’ trade organizations now regularly produce and provide content via the web, but you have to be prepared to pay for it, because reliable information costs money. Incorporate trade shows, seminars, and educational events into your efforts to accumulate third-party data. These events can not only offer a great source of information, but also (and potentially more importantly) be places to make contacts with potential future employees, vendors, customers, and funding sources that can assist with the execution of the business plan. The third-party information you gather should cover multiple aspects of your business. Following are three examples of data sources for a jewelry ­company: ✓ The World Gold Council provides an excellent overview of consumer gold-buying trends and patterns by price points, types of jewelry, and different sales channels. This information can support the marketing segment of the business plan. ✓ If the production of jewelry is required, then information on available manufacturing sources is needed. Because a large majority of jewelry is produced globally (from Southeast Asia to Europe to Central America), the company needs to make sure that it has a good handle on the political, social, and economic stability of any foreign suppliers. ✓ In addition, if the jewelry company is going to sell products through retail storefronts, then an overview of commercial real estate rental rates, trends, and so on can be incorporated (for a specific geographical area) to support a critical expense driver in the business. Riding the CART concept: Complete, ­accurate, reliable, and timely During the planning process, evaluate your data to make sure it’s complete, accurate, reliable, and timely (CART). Actually, you should apply the concept of CART to all business segments; whether you’re developing a business plan, analyzing periodic operating results, or evaluating an employee benefit plan. Business owners and managers must have complete, accurate, reliable, and timely information to make savvy business decisions. Whether the information Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 382 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business and data is coming from internal or external sources, from the marketing or manufacturing departments, the basis of the budget is having access to complete, accurate, reliable, and timely information. ✓ Complete: Financial statements include a balance sheet, income statement, and a statement of cash flows (see Books IV and V for more on these statements). All three are needed in order to understand the entire financial picture of a company. If a projection model is incorporating an expansion of a company’s manufacturing facility in a new state (to keep up with rising demand), all information related to the new facility needs to be accumulated to prepare the budget. This info includes the cost of the land and facility, utility costs in the area, potential environmental issues, whether a trained workforce is available, and so on. Overkill isn’t the objective; having access to all “material” information and data is. ✓ Accurate: Incorporating accurate data is absolutely essential for preparing the business plan. Every business plan needs to state the price your company charges for the goods or services it sells, how much employees are paid, what the monthly office rent is, what evolving patterns exist in sales channels, and every other relevant detail. Accumulating accurate information, whether from internal sources or external third parties, represents a critical and ongoing management endeavor. ✓ Reliable: The concepts of reliability and accuracy are closely linked, but they differ as well. A piece of information may be accurate without being reliable. For example, you may conduct some research and find that the average wage for a paralegal in San Diego, California, is $24 per hour. This data sounds accurate, but if the business model you’re developing requires paralegals with special training who demand $37 per hour, the information isn’t reliable. ✓ Timely: Finally, the information and data must be accumulated in a timely fashion. Data provided six months after it was needed doesn’t do management much good. Companies live and die by having access to real-time information on which to make business decisions and change course (and forecasts) if needed. An old phrase that’s often quoted, “Don’t put the cart before the horse,” means you shouldn’t buy a cart before you have a horse to pull it; in other words, you should do things in the proper order. However, the CART principle is a case in which the “cart” always needs to come first. You must put the CART information and data before the horse (the business plan). If you attempt to offer a business plan that hasn’t been created through CART data, the end result will be nothing short of disastrous. Chapter 4 Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line In This Chapter ▶ Getting up to speed on budgeting fundamentals ▶ Gathering accurate information and projections ▶ Drawing up a budget — the essential budget documents Y ou need accurate information to make smart decisions about your ­business. A well-planned budget may be the most important piece of information you use. Budgeting is a proactive process. It’s the thinking ­person’s accounting. You anticipate future outcomes and can maximize them. You anticipate problems and may be able to minimize or eliminate them. That’s a lot better than operating in ignorance and reacting to events as they arise. In this chapter, you look at budgets, consider how to anticipate costs, and work through some essential budget documents. Brushing Up on Budgeting Basics A budget is a financial plan that includes both financial and non-financial ­information. Its most obvious features are revenue and expense projections — how much you anticipate earning and spending. The budget can also contain non-financial information, such as how many employees you think you need. A budget is a forecasting document, but businesses also use it as a financial control tool to monitor activities in their business. One control is to review spending and ensure that you don’t exceed your budgeted spending. Often, a company (or a division or a department within it) isn’t allowed to spend more than has been budgeted. Budgets cover a specific period of time, most commonly a year, and they look into the future. Although you use historical information to develop a budget, the activities you plan happen in the future. 384 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Meeting the master budget The master budget is a comprehensive picture of your plans for the future and how the plans will be accomplished. It’s a summary of your financial and operating plans: ✓ The financial plan (financial statements, really) is what you share with outside parties who need your budgeted information, including lenders, stockholders, and perhaps even government regulatory agencies. ✓ The operating plan (also known as the operating budget) is used internally, mostly by managers, to set sales goals and develop their own budgets. You hand out the operating plan to each manager, and the managers implement the plan. Operating plans can contain non-financial information. Decisions about production, hiring, and selling efforts are components of operating plans. Understanding key budgeting concepts Budgeting forces you to plan how to use your assets wisely to generate revenue. (Assets are resources, including cash, buildings, machinery, office equipment, and anything else your businesses uses to conduct business.) As you develop your budget, keep the following key concepts in mind: ✓ Depreciation: Long-term assets, such as trucks and machinery, depreciate; that is, they wear out and are worth a little less every day as you use them up. You need to budget for operating costs and depreciation, so you have sufficient cash to replace these assets when they’re used up or no longer useful. (Head over to Book III, Chapter 1 for more on depreciation.) Milk all the revenue you can from an asset before disposing of it, unless maintenance of that asset exceeds the cost of replacing it or a newer model would improve efficiency to the point of at least paying for itself. ✓ Opportunity cost: When you use an asset to manufacture product A, you give up the opportunity to use that asset to produce product B, which would have generated revenue, too. When developing a budget, consider opportunity cost, and make choices on how to use assets that minimize these costs. ✓ Cash flow: When you conduct business, cash flows through your business. It flows in as revenue and flows out as expenses. One of your primary goals when developing a budget is to make sure you have at least as much cash flowing in as you do flowing out. Book V, Chapter 2 goes into more detail on cash flow. Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line 385 Planning strategically Whether you’re starting a new business, launching a new division or a new product line, or simply preparing for the future, you need to develop a strategic plan — your business’s road map to the future. The plan reminds you, your employees, and third parties what you do, how you do it, the customers you do it for, and maybe even how you’ll do it in a superior way. Your strategic plan summarizes where your business is, where it wants to go, and how it’s going to get there. Your budget, of course, is an important part of strategic planning. The budgeting process forces you to think, make decisions, and come up with reasonable forecasts. You can’t sidestep potential negatives, either. That would be like a farmer overlooking the possibility of a drought. If you’re trying to attract financing to fuel your business venture, you’d better have a strategic plan (business plan) in place that lays out exactly how the business is going to generate sufficient revenue to cover its bills and either make payments on its loans or produce a return on any investments in the business. Nobody will lend money or invest in a business without seeing how that business plans to make money. Strategic planning methods exist in abundance and seem to be a thriving cottage industry. They contain more letters than ten cans of alphabet soup, and include SWOT, PEST, STEER, EPISTEL, ATM, and RCA. Be cautious, and use common sense before embracing a planning methodology. For additional guidance in developing a strategic plan, check out Strategic Planning For Dummies by Erica Olsen ( Wiley). Recognizing Factors That Impact Your Budgeting Process Whether you’re developing a budget for a business or a household, one of the biggest challenges is coming up with good ballpark estimates. Consulting a fortune teller or staring into a crystal ball probably won’t help. Useful information comes from your experience, what you know about timing, the facts and figures your staff supplies, and your own sales projections. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 386 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Experience counts Business owners with little experience in an industry often plan poorly, in part because they don’t have much personal history to go on. Also, some people have trouble accepting the reality of their business prospects. For example, they really want the business to grow 30 percent and can’t accept the fact that 10 percent is more realistic. Consider three brothers who were opening a pizza-parlor franchise. The franchise was successful in other parts of the county. The brothers were opening a store in a new area of town. All good. None of the brothers had any restaurant industry experience. Two of the brothers sold business envelopes, and the third was a professional golfer. Not so good. The brothers performed an analysis and determined that the profit margin was only 5 percent, barely enough to pay each of them a meager salary. They went forward with the business anyway. Perhaps they thought that 5 percent figure was wrong or that they could somehow increase it. Within a few years, the brothers closed the business. If the brothers had experience in the pizza business, they probably wouldn’t have bought the parlor, or they would have at least had more realistic expectations. Timing is everything Different business decisions have different timelines that depend, in part, on the dollar amount of the decision you’re making. Understanding your timeline helps you make intelligent decisions about spending. For example, if you decide to use a different supplier for your materials, you could start buying materials from that company immediately. No problem. On the other hand, completing a move into a newly constructed building may take a year or more. You need to consider timelines for your more expensive business decisions. If you’re building a new office, determine how long the construction will take. Based on the timeline, you can plan your payments for the building and how you’ll generate cash to make the payments. Explain your timeline in your business plan. If you’re providing financial statements (discussed later in this chapter) for one year, you may need to explain payments for a building (asset) that isn’t yet completed. It’s ­perfectly reasonable to expect a business to pay for major assets over a long period. Just be sure to explain it to your investors or lenders. You may have a one-year operating budget, along with a capital ­expenditure budget for three to five years. The capital expenditure budget is the ­big-things-I’ll-buy-and-pay-for-long-term budget. This budget helps you and others v ­ isualize your long-term plans and spending. Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line 387 People get you headed in the right ­direction The budgeting process isn’t only about numbers; it also involves people. A budget is something that a group of people typically reviews and eventually comes to an agreement on. Involve people, consider their opinions, and get their buy-in on the budget. If the company’s managers don’t generally agree on where you’re headed in your budget, you may need to revise it. Talk to your staff. If you’re concerned about wasting material in the manufacturing process, talk to people on the factory floor. Maybe you’ll find out that poor quality is the reason some material is wasted during production. Maybe some denim you use to make jeans tears too easily, and you need to find a new supplier. You may never find out about that if you don’t spend some time on the factory floor. Talk with the sales staff to plan sales for the year. Good salespeople know their clients. They may know about a client’s purchasing plans for next year. They may even know a client’s budget to buy your product! Also, a good salesperson knows the customer’s financial condition. If the customer’s business is growing, he or she may buy more from you. If the business is in financial trouble, sales may decline. Have a conversation with the accountant during planning. She knows how cash flow turned out last year. You can look at the data on how quickly you collected cash for sales. Also, your attorney may remind you of any legal issues that could possibly generate expenses during the year. There may be costs for legal services or costs to settle litigation. Those costs require cash, and you need to include them in your plan. When your budget is in good shape, present it to your staff and explain where the company is headed. They’ll feel more confident knowing the company’s direction and prospects, especially if they played a role in developing the budget. Sales projections pay off Sales projections help answer the question of how you earn a reasonable level of profit. Of course, the answer is complicated if competitors are selling the same product or service, because it suggests you may have to lower prices to stay competitive. If you want to cut prices to attract business, you need to plan your costs so your profit level remains reasonable. Another ­possibility is to improve the design of your products and not change prices. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 388 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business If you do that, you add the cost of design to product costs. But increased sales without cutting prices may offset the cost of design. Good planning is useful, and poor planning leads to projections (of profit, sales, and company growth) that aren’t useful. If you base decisions on inaccurate projections, you’re likely to use assets in ways that won’t maximize your profits. Simply put, you end up spending time and money on the wrong activities. Coming up with accurate sales projections often begins with market research. Suppose you’re selling running shoes in the United States, and you discover that 10 million people buy running shoes each year in the U.S. On average, they spend $80 for a pair. Fortunately, you’ve priced your shoes at $78, so you’re right around the average. Next, you estimate that your firm can capture 10 percent of the U.S. runningshoe market. That means a total sales volume of 10 percent of a 10 millionunit market, or 1 million units sold in a year. At $78 a pair, you project your sales to be $78 million. Finally, you consider whether the market is growing or shrinking. If the running-shoe market is growing at 10 percent per year, you could reasonably increase your sales projection by 10 percent each year, also. Of course, market growth is impacted by the overall economy and the specific industry (sporting goods, in this case). Competitors may also impact your growth. You’d need to project all these contingencies before coming up with a reasonable sales forecast. The sales growth rate drives decisions about spending, employee hiring, and cash planning. If you’re selling 30 percent more, you can plan to increase your spending and hire employees to manufacture 30 percent more of your product. You also probably can expect a 30 percent increase in cash inflow as a result of growth. But wait! If a more careful review indicates 10 percent growth, your 30 p ­ ercent projection creates some problems for you. You increased your spending and hiring assuming the 30 percent level, but the sales and cash inflows will only come in at 10 percent. Put simply, you’re planning on spending 20 percent too much. Whether you’re building homes or selling running shoes, the numbers still apply. The Nuts and Bolts of Budgeting Begin the budgeting process by deciding which company entities require a budget and how detailed it needs to be. You may decide to develop a budget for the entire company or for each division or department within it. In budgeting, you begin with some assumptions. The assumptions are called standard costs and are the specific planned levels of cost and activity. For example, you may assume a standard labor rate (cost) of $20 per hour for Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line 389 a sewing-machine operator. You may assume a standard material rate of $75 per square foot for marble for kitchen countertops. When you create your budget (based on reasonable assumptions) and start the year’s business, you have actual costs and levels of activity to review. A ­difference between an actual cost and standard cost is a variance. A ­variance is a scorecard that tells you how close your budget assumptions were to actual results. Fortunately, you can make modifications to your budget to deal with variances. (See Book VII, Chapter 4 for more about variance a ­ nalysis.) Understanding the budgeting financials Your budget becomes a set of pro forma financial statements. Pro formas are what-if statements, filled with budgeted, planned, and forecasted items. Unless you have a crystal ball, your budget is always a collection of educated best guesses about the future. To keep things simple, a budget uses three basic financial statements: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the statement of cash flow (head over to Books IV and V for more on financial statements). Another aspect is an explanation of your source of funds. Source of funds Your budget determines whether you have enough funds to run your business. Hopefully, you get all the money you need from selling products or services, but that’s not always the case. The financial plan (also loosely called the business plan) explains the source of funds to run the business. You can raise money by borrowing cash (debt) or by offering investors ownership in the business (equity) in exchange for cash. (See Chapter 1 for guidance on raising funds.) For now, consider how you budget for the process. If you borrow, you repay a creditor the original amount borrowed (principal) and interest on the loan, usually on a written schedule. The interest cost and principal repayment must be included in the budget. You can also raise funds by selling ownership in your business, offering investors equity. Equity investors are rewarded in two ways: stock appreciation and dividends. The most common way to sell ownership is to sell common stock. Investors expect you to explain (through your budget) how you plan to generate a profit for the year. If the company is profitable, the value of their ownership in your business increases. They could eventually sell their ownership ­interest to someone else for a profit. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 390 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business You also need to consider whether to pay dividends. Dividends are a share of the profits earned by the company paid to equity investors. Of course, ­without any company earnings, you can’t pay dividends. Using the balance sheet The balance sheet lists the company’s assets, liabilities, and equity (essentially the difference between assets and liabilities) as of a certain date. Think of the actual balance sheet as a snapshot in time; think of the budgeted balance sheet as a pretty good estimate of the actual financial statement. Liabilities are claims on your assets. A liability means that you owe ­someone money. Liabilities include items such as unpaid utility bills and payroll costs you haven’t yet paid. Future interest and principal payments on a loan are also liabilities. When you pay a liability, you use an asset (cash, in most cases) to make payments. This gets you to the balance sheet equation, introduced in Book I, Chapter 1: Assets – Liabilities = Equity Consider this scenario: Assume you own a little shop. You sell all your assets — your inventory, furniture, and your building. You use the cash you receive to pay off all your liabilities — utility bills, payroll, and bank loan. Whatever cash remains after you pay off your liabilities is your equity. Equity is the true value of your business. So now you can see the logic behind the balance sheet formula: Assets less liabilities equals equity. Working with the income statement The income statement shows revenue, expenses, and net income (profit) or loss. For most business owners, the income statement is the most important report. It shows whether a business was profitable over a period of time (such as a month, quarter, or year), whereas the balance sheet shows assets, liabilities, and equity as of a specific date. The nice thing about modern accounting software is that it can generate an income statement almost instantly. Think of the budgeted income statement as a pretty good projection of your company’s sales, expenses, and profit. The income statement formula is incredibly simple: Revenue – Expenses = Net income or loss Analyzing the statement of cash flows The statement of cash flows analyzes sources of cash (cash inflows) and uses of cash (cash outflows) over a period of time. Stroll over to Book V, Chapter 2 for more on cash flows. Cash flows are grouped into three categories: Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line 391 operating, financing, and investing activities. When an accountant puts together a cash flow statement, she reviews every transaction that affected cash. A very simple model is what’s in your checkbook. If inflows are good, you probably have enough cash to operate. If the checkbook shows that you’re overdrawn, outflows have exceeded inflows, and you’ve got trouble. The goal is to assign every cash transaction to one of three categories, although most of your cash activity is in the operating activities section. To simplify the process, find the financing and investing activities first — because they represent fewer transactions. The remaining transactions are operating activities. The three cash flow categories are: ✓ Operating activities occur when you run your business each day. You buy material, pay for labor, ship goods, pay interest on loans, and collect cash from customers. ✓ Financing activities occur when you raise money for your business, and when you pay lenders or investors. You receive cash when you sell equity, and you receive cash when you borrow. You pay cash when you pay dividends, and you pay cash when you pay down a loan (pay back some of the principal). ✓ Investing activities occur when you buy or sell assets. Writing a check for a new vehicle and receiving cash when you sell equipment are ­investing activities. The statement of cash flows lists the beginning cash balance; all the cash activity for the period, grouped into three categories; and the ending cash balance: Ending cash balance = Beginning cash balance +/– Net cash flow of ­ perating activities +/– Net cash flow of financing activities +/– Net o cash flow of investing activities A simpler formula is Ending cash balance = Beginning cash balance + Cash inflows for the period – Cash outflows for the period The ending cash balance in the statement of cash flows equals the cash ­balance in the balance sheet (well, it’s supposed to, anyway). For example, if the statement of cash flows is for March, the ending cash balance should equal the balance sheet cash balance for the last day of March. When you create your budget, it should include all three financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows). Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 392 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Reviewing revenue and production b­ udgets Revenue and production budgets, put simply, forecast how many units you plan to produce and how many units you plan to sell. Say you’re budgeting to manufacture garage doors. You need to forecast how many sales you expect. Then consider how many garage doors you already have in inventory and plan how many you need to manufacture to meet the sales forecast. Ta da! When you know the number of doors you need to make, you can budget for material and labor costs. Material and labor costs are considered direct costs, because they can be traced directly to your product. Indirect costs are those that can’t be directly traced to the product. Repair and maintenance costs for a machine, for example, are indirect costs. You may assign these costs by dividing the total cost incurred by the number of hours the machine ran during the month. That would give you a rate per machine hour. If you incur two hours of machine time to make one unit of product, you would multiply two hours by the machine rate per hour. That indirect cost total would be added to the unit of product. Revenue, production, inventory, direct materials, direct labor, indirect costs (overhead), and cost of goods sold all are budgeted items. Applying the revenue formula Suppose you forecast selling 200 garage doors in March. Consider how many garage doors you need to manufacture. Assuming a sales price of $300 per door, here’s your revenue budget: Revenue budget = 200 units × $300 Revenue budget = $60,000 Using the inventory formula And now for the famous inventory formula: Ending inventory = Beginning inventory + Production – Sales Your production will change based on how many garage doors you already have in inventory. So if you already have 75 completed garage doors in ­beginning inventory, you won’t need to manufacture all 200 units you plan to sell. (For more about inventory, see Book II, Chapter 2.) Chapter 4: Budgeting for a Better Bottom Line 393 But wait! Do you want any garage doors in ending inventory? If you think you’ll have orders during the first few days of the next month, you probably want to have at least a few garage doors left at the end of this month. So maybe you decide on an ending inventory of 50 garage doors. Take the inventory formula and calculate the garage door production you need. Assume x is production in units, and solve for x: Ending inventory = Beginning inventory + Production – Sales 50 = 75 + x – 200 50 – 75 + 200 = x Book VI x = 175 This simple algebra problem shows that production should be 175 units. Table 4-1 shows a production budget. Table 4-1 Garage Door Production Budget Cost Quantity Price Total Direct material (wood) 80 square feet $1 per square foot $80 Direct labor (labor) 2 hours $25 per hour $50 Indirect costs allocated 1 hour $15 per hour $15 Cost per unit Production cost $145 Units Unit cost Total cost 175 $145 (above) $25,375 The production budget includes direct materials, direct labor, and indirect costs (overhead). In this example, the indirect cost is allocated based on machine hours. Add the costs to get a unit cost. Then multiply units to be produced by the cost per unit. That amount is the total cost of production of $25,375. Assessing cost of goods sold The goods you produce for customers end up in one of two places: You either sell them (cost of goods sold), or they’re still on the shelf (finished goods inventory). Beginning inventory and production don’t matter. Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 394 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business What costs should be attached to the goods you sell? How much did they cost to produce? (If you’re a retailer, how much did they cost to get?) To ­continue with the garage door manufacturing example, assume the first goods you sell are from beginning inventory. Because all 75 units of beginning inventory are sold, use a formula to determine how many units of the March production are sold: March production sold = Total sales – Beginning inventory March production sold = 200 – 75 March production sold = 125 Assume also that the cost per unit of beginning inventory is $143. That cost is different from the March production cost of $145. (Why the change? Because the costs of materials and labor to make a garage door rose.) Table 4-2 displays the cost of goods sold budget. Table 4-2 Garage Door Cost of Goods Sold Budget Units Cost Per Unit Total Cost Beginning inventory 75 $143 $10,725 March production sold 125 $145 $18,125 Total 200 $28,850 The total cost of goods sold is higher ($28,850) than total production cost in Table 4-1 ($25,375). That makes sense, because Table 4-1 deals only with producing 175 units. You sold 200 units, but 75 units were from inventory. Because of adjustments for beginning and desired ending inventory, you don’t always need to produce in a month the number of units you sell in a month. One more calculation. (There’s always one more calculation.) Now calculate your ending inventory budget: Ending inventory budget = Units × Per unit cost Ending inventory budget = 50 × $145 Ending inventory budget = $7,250 You’ve planned revenue, production, and inventory. Great! Now you need to figure out how to pay for it all. If you don’t have a budget for an adequate cash amount to operate, you can’t do business. See Chapter 5 for guidance. Chapter 5 Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting In This Chapter ▶ Applying accrual accounting to the budget process ▶ Producing a budgeted income statement and balance sheet ▶ Creating a flexible budget Y ou can master budgeting basics and figure out how to budget for sales and production in Chapter 4. Then you’re ready to tackle more detailed aspects of budgeting, weigh the pros and cons of budgeting with cash-basis or accrual accounting, and develop a flexible budget. This chapter explains how to use the information from your budget for sales and production to create a budgeted income statement and balance sheet. It also reveals how to put together a flexible budget that accommodates different levels of production. But the first order of business is to understand why accountants use accrual rather than cash-basis accounting to create budgets. Budgeting with Cash or Accrual Accounting Nearly every large corporation uses accrual accounting both to record transactions and to budget. Small businesses have a choice: They can use cash basis accounting or accrual basis accounting: ✓ Cash basis accounting posts revenue and expenses to the financial statements based solely on cash transactions. Nothing happens until you take cash in or pay it out. It’s a simple way of doing things — no accounts receivable and no accounts payable. 396 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business ✓ Accrual basis accounting states that expenses are matched with revenue, regardless of when cash moves in or out of the checkbook. The accrual basis is a better method to account for profits, because revenue and expenses are matched more precisely. See the section “I accrue, you accrue, we all accrue with accrual accounting.” You can use either method to produce a budget, but accrual is better and is used by all large organizations. (See Book I, Chapter 4 for more about cash and accrual accounting.) This section discusses these concepts in the context of the budgeting process. A useful budget uses accrual accounting, which matches revenue with expenses. Using the cash method — budgeting based on cash inflows and outflows — doesn’t provide an accurate picture of your budgeted profit level. Cash basis accounting: Using your checkbook to budget On a very basic level, your cash budget is a reflection of your checkbook. It’s the sum of the deposits you make (revenue) and the checks you write (costs). The budgeting result of cash basis accounting is a cash budget. Such a budget assumes that all your customers pay for sales in cash during the month of sale and that you pay all costs during the month that the goods are sold. This scenario is highly unlikely for most businesses. It’s more likely that you write a check in February for materials for a product you sell in April. Similarly, you may pay an employee in December for work to make a product that’s sold in January. Assume you own a shop that sells greeting cards, flowers, and gifts. Your beginning cash balance for the month is $100,000. Table 5-1 displays a cash budget for a gift shop. Table 5-1 Gift Shop Cash Budget — Month of March Amount Beginning cash balance Add customer payments for sales $100,000 $50,000 Less: Inventory purchases $20,000 Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting 397 Amount Payroll costs $10,000 Utilities costs $1,000 Lease cost $3,000 Ending cash balance $116,000 This cash budget has a $16,000 increase in cash during the month ($116,000 – $100,000). You had $50,000 in sales. If you hadn’t collected any cash from customers during March, your cash balance would decrease by $34,000, the total of all the cash outflows. If that happened, you’d start the next month with $34,000 less cash. You need to consider whether your April cash budget (next month) would work with a lower beginning balance in cash. You don’t want to start in the red. If you don’t think you’ll have enough cash for a period, you can consider how to get it. The cash budget is similar to the statement of cash flows. Table 5-2 shows an example statement of cash flows for the gift shop. Table 5-2 Gift Shop Budgeted Statement of Cash Flows Amount Beginning cash balance Cash flow from operations $100,000 $16,000 Cash flow from financing $0 Cash flow from investing $0 Ending cash balance $116,000 Note that the beginning and ending cash balances in Table 5-2 agree with the cash budget ($100,000 at the beginning and $116,000 at the end). The cash flow calculation from operations is Net cash inflow from operations = Customer payments – Cash outflows Net cash inflow from operations = $50,000 – $34,000 Net cash inflow from operations = $16,000 All the cash flows for the gift shop are related to day-to-day operations. None of the cash activity is related to financing or investing. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 398 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business I accrue, you accrue, we all accrue with accrual accounting An effective budget applies the matching principle. The principle states you should match the timing of the expenses of creating and delivering your product or service with the timing of getting revenue from the sale. This is accrual basis accounting (as opposed to cash basis accounting). Accrual accounting ensures that revenue is more precisely matched with the expenses incurred to generate revenue. With accrual accounting, when you create an invoice, the accounts receivable (A/R) system generates a receivable, even though the customer may not pay for, say, 30 days. When the payment arrives, the receivable is adjusted to zero, meaning it’s been satisfied by the payment. Accrual accounting is considered to provide a more accurate reflection of business activity than cash accounting. By the way, the system still allows for straight cash sales — where you sell now and the customer pays now. The same is true of purchases you make. When you buy now and pay later, you create a payable. When the bill comes and you pay it, the payable is adjusted to zero. Of course, the system allows you to make straight cash purchases — where you buy and pay your vendor now. Suppose you manage a catering business. The food, preparation cost, and delivery expenses related to the Jones family reunion should be matched with the revenue from the Jones family. Ideally, you want the expense and the revenue to be posted in the same time period. You wouldn’t want the Jones expenses posted in March and the Jones revenue posted when they paid (say, in April). That’s not the best reflection of your business activity. The downside of accrual accounting is that your income statement revenue and expenses rarely match your cash inflows and outflows. You can be rich in receivables and darned poor in cash. But most companies still prepare a cash flow statement even if they’re using accrual accounting. Budgeting to Produce the Income Statement and Balance Sheet A final step in the budgeting process is to create a budgeted balance sheet and budgeted income statement. Your balance sheet and income statement, whether budgeted or actual, are the two great financials. They reflect the bottom line, showing how the business is doing. Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting 399 The well-balanced balance sheet Your balance sheet is a fine indicator of business health. Table 5-3 shows a healthy balance sheet. Table 5-3 Budgeted Balance Sheet Amount Assets $100,000 Less liabilities $50,000 Book VI Equals equity $50,000 Planning and Budgeting for Your Business As you review your balance sheet budget, keep in mind the goal is to maintain enough assets to run your business, which includes production (if you make things), buying inventory (if you’re a retailer), or employing people (for manufacturing, retailing, or service businesses). The balance sheet should include assets needed for selling and distributing your products. Managing your business generates liabilities, too (accounts payable, long-term debt, and so forth). That’s okay, as long as you have a plan to pay them. If revenue doesn’t supply you enough of the best asset — cash — you need a plan to raise capital. Capital represents an investment in your business. If a business owner invests $20,000 into his business, the $20,000 is considered capital for the business. That means you’re probably either issuing debt (taking out a loan) or selling equity (shares of the company) to stockholders. The incredible income statement Most business owners are most interested in the income statement. The owner typically plans this budget document first. Table 5-4 shows a budgeted income statement that projects a healthy net income. Table 5-4 Budgeted Income Statement Amount Revenue $50,000 Less expenses $25,000 Equals net income $25,000 400 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Here’s the thought process: You figure out how much revenue the company can generate. Then you subtract likely expenses from the revenue, and the result is your net income. After that, think about how cash will “move” (the cash flow statement) and where your company will get sufficient assets to operate (the balance sheet). As you move forward in managing your business, don’t be surprised if cash flow becomes the most important budget item for you. Without enough cash flow, not much happens. Flexing Your Budget: When Plans Change Regardless of how carefully you budget, plans may change. Assume you plan a cross-country family camping trip. You diligently create a budget spreadsheet based on your research and assumptions. Unfortunately, nearly everything costs more than you estimated. A 30-percent increase in the price of gas adds more than $1,000 to the cost of the trip. And although you timed the trip to drive 600 miles per day, you don’t take into account stops for coffee, restrooms, or motion sickness. As the road trip attests, budgets don’t have to be set in stone. This section explains how to use flexible budgets to manage your business’s operations. Controlling your business Budgeting helps you plan your business’s operations. However, you also need to control your business — to monitor what’s actually happening. Controlling involves constantly comparing actual activity to your budget and carefully analyzing and understanding any differences. To accomplish this task, you need budget reports that compare your budgets (what should have happened) to what actually happened. For example, suppose your company budgeted $100,000 for sales in the first quarter. Actual sales for the quarter fall short, at only $70,000. First, call the sales manager to find out what happened. (Maybe a computer snafu accidentally canceled customer orders.) Then, take corrective action. (Fix your computer and call your customers to apologize.) Finally, adjust your future plans. (Cut next quarter’s production estimates.) Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting 401 Chapter 4 provides the basic template for budgeting, offering projections for sales, expenses, production levels, and cash flows to help you plan for future periods. However, its major flaw is that it’s static — it projects only one scenario based on a single set of sales estimates. It can’t change. Therefore, a $30,000 difference throws off more than just your sales budget. It also necessitates changing your production, purchases, direct labor, overhead costs, and selling and administrative expenses, ruining the entire planning process and making it impossible for you to make future comparisons between your budgets and actual results. Enter the flexible budget. As activity levels change, you can easily adjust a flexible budget and continue to use it to plan and control your business. Dealing with budget variances One of the benefits of flexible budgeting is that it helps you to understand the reasons for your company’s variances, the differences between actual and budgeted amounts. Chapter 4 introduces the concept of a variance. The next section gives you the lowdown on the flexible budgeting process, but first you should delve a little deeper into the issue of variances. Always indicate whether a variance is favorable or unfavorable. A variance is usually considered favorable if it improves net income and unfavorable if it decreases income. Therefore, when actual revenues exceed budgeted amounts, the resulting variance is favorable. When actual revenues fall short of budgeted amounts, the variance is unfavorable. On the other hand, when actual expenses exceed budgeted expenses, the resulting variance is unfavorable; when actual expenses fall short of budgeted expenses, the variance is favorable. Management should investigate the cause of significant budget variances. Here are some possibilities: ✓ Changes in conditions: For example, a supplier may have raised prices, causing the company’s costs to increase. ✓ The quality of management: Special care to reduce costs can result in favorable variances. On the other hand, management carelessness can drive up unfavorable variances. ✓ Lousy budgeting: An unrealistically ambitious budget is likely to cause unfavorable variances. Many managers use a system called management by exception. They investigate the largest variances, whether favorable or unfavorable, and ignore the rest. This strategy helps managers prioritize potential problem areas in operations. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 402 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Implementing a flexible budget To compute variances that can help you understand why actual results differed from your expectations, creating a flexible budget is helpful. A flexible budget adjusts the budget for your actual sales or production volume. For example, your budget may have assumed that you’d produce 5,000 units; however, you actually produce 5,100 units. The flexible budget accommodates this new number, making all the appropriate adjustments to sales and expenses based on the unexpected change in volume. To prepare a flexible budget, you need to have a budget, really understand cost behavior, and know the actual volume of goods produced and sold. Consider Kira, president of the fictional Skate Company, which manufactures roller skates. Kira’s accountant, Steve, prepares the overhead budget shown in Figure 5-1. Figure 5-1: Skate’s static overhead budget. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Skate had a great year; actual sales came to 125,000 units. However, much to the disappointment of Steve and Kira, the overhead budget report, shown in Figure 5-2, reports major overruns. For each category of overhead, Steve computes a variance, identifying unfavorable variances in indirect materials, indirect labor, supervisory salaries, and utilities. Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting 403 Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Figure 5-2: Skate’s overhead budget report. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Skate’s total overhead exceeds budget by $25,000. Steve makes the elementary mistake of treating variable costs as fixed. After all, portions of overhead, such as indirect materials, appear to be variable costs. If Skate increases production from 100,000 units to 125,000 units, these variable costs should also increase. In other words, comparing the $60,000 actual indirect cost of making 125,000 units to the $50,000 budgeted indirect cost of making just 100,000 units makes no sense. You’re comparing apples and oranges. Different levels of activity (units) generate a different level of variable costs (indirect costs). Instead, Steve should flex the budget to determine how much overhead he should have, assuming that the company makes more or less than the budgeted number of units. The following sections show you how. Separating fixed and variable costs Some costs are variable — they change in response to activity levels — while other costs are fixed and remain the same, regardless of activity level. For example, direct materials are variable costs because the more goods you make, the more materials you need. On the other hand, some overhead costs, such as rent, are fixed; no matter how many units you make, these costs stay the same. To determine whether a cost is variable or fixed, think about whether or not the total cost changes when the level of activity changes. 404 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business For Skate, an analysis indicates that indirect materials, indirect labor, and utilities are variable costs. On the other hand, supervisory salaries, rent, and depreciation are fixed. Steve recomputes variable costs with the assumption that the company makes 125,000 units, as shown in Figure 5-3. Figure 5-3: Flexing variable overhead costs. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. In the original budget, making 100,000 units results in total variable costs of $130,000. Dividing total cost of each category by the budgeted production level results in variable cost per unit of $0.50 for indirect materials, $0.40 for indirect labor, and $0.40 for utilities. To compute the value of the flexible budget, multiply the variable cost per unit by the actual production volume. Figure 5-3 indicates that the variable costs of producing 125,000 should total $162,500 (125,000 units × $1.30). Comparing the flexible budget to actual results The final step is to combine the variable and fixed costs in order to prepare a new overhead budget report, inserting the new flexible budget results into the overhead budget report as shown in Figure 5-4. Chapter 5: Mastering and Flexing Your Budgeting 405 Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Figure 5-4: Skate’s flexible overhead budget. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Look at that! After you adjust for the change in production level, Skate’s variance is suddenly favorable. Actual overhead of $355,000 was $7,500 less than the $362,500 flexible budget. 406 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Chapter 6 Planning for Long-Term Obligations In This Chapter ▶ Discovering how a company raises cash ▶ Identifying long-term liabilities ▶ Accounting for notes payable ▶ Reporting gain or loss on debt extinguishment ▶ Considering bonds I f you own a car or house you financed, you’re probably all too familiar with long-term debt: loans that won’t be paid off by the end of the next 12-month period. Well, companies have long-term debt, too. A company usually uses current debt as a vehicle to meet short-term obligations like payroll and incurs long-term debt to finance company assets. This chapter gives you the lowdown on two types of long-term debt: notes and bonds payable. Notes payable are debt a company takes on typically through lending institutions, such as banks, to finance asset purchases. Asset purchases include cars, equipment, and buildings. Bonds payable are typically issued by hospitals and municipalities to fund expansion (although corporations can issue them too). Here you find out all you need to know about this complicated topic. Managing Long-Term Debt An immutable fact of running a business is that at some point the company will have to take on long-term debt to grow its operations. After all, unless the business owners are running the business just for fun, they want to expand operations in the hopes of making more money. 408 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business The way you structure long-term debt affects the expense of borrowing the money. When you finance a vehicle or home purchase, you probably shop around for interest rates and evaluate the options of financing the loan for a shorter or longer term. Businesses do the same, but they may carry millions of dollars of debt on their balance sheet, and they have to service this debt. Debt service is the process of making principal and interest payments on debt. Managing the debt service is crucially important because minute differences in terms can have a large effect on interest and the bottom line. A company may raise cash to purchase assets, expand existing operations, or maybe even buy another company. If the firm decides to do so by accumulating long-term debt, management evaluates the relative merits of available forms of long-term debt. The most common types of long-term debt are mortgages, notes payable, and bonds payable. The next few sections discuss mortgages and notes payable. See “Accounting for Bonds,” later in this chapter, for coverage of bonds. The many faces of notes payable Notes payable are formal written documents that spell out how money is being borrowed. This type of agreement between a lender and a borrower specifies principal (amount borrowed), rate (interest percentage the company pays to borrow the money), frequency of payments, and term (the amount of time the company has to pay off the loan). Notes payable are issued in three different ways: face; no-face, no-interest; and no-face, interest. These terms may make lending and borrowing seem like a silly game of peek-a-boo, so take a look at their definitions in the following sections. Keep in mind that face refers to face amount — a specific dollar amount stated on the face of the note payable. It represents the principal amount that the borrower must repay. The note payable document should list everything that the borrower and lender need to know about the liability, including the principal amount owed. Face Face is the easiest type of note to account for. With this type of note, the present value of the note payable is the same as its face, which is the amount stated on the note. (For more about present value, check out Book V, Chapter 1.) This sameness results because the effective interest rate, which is the market interest rate, and the stated interest rate (what’s printed on the face of the note payable) are the same. Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations 409 Market is the interest rate for a note of similar risk. The level of risk refers to the creditworthiness of the borrower — the ability to repay principal (face amount) and interest on time. For example, if one company loans another company $5,000 at an effective and stated rate of 10 percent due in three years, the journal entry for the borrower to record issuance of the note is to debit cash and credit notes payable for $5,000. Each year, the borrower records interest expense at $500 ($5,000 × 0.10). The journal entry is to debit interest expense and credit cash for $500. When the company pays off the debt at the end of the three years, the borrower records a credit to cash and a debit (reduction) to notes payable for $5,000. No-face, no-interest A no-face, no-interest note payable is issued for the present value of the amount the borrower receives from the lender, which is less than the face value (future value) of the note. The difference between the face value and present value of the note is called a discount, which represents the total interest to be paid over the life of the loan. To determine the present value of the amount borrowed and figure the discount, use a present value of $1 table. This table assumes a single payment and that you need to compute the present value of that payment. Search the web to find present value tables for a single payment and for multiple payments (annuities). Take the following steps, which assume a single payment: 1. Using a present value of $1 table, find the factor at the intersection of the loan percentage and period, as shown in Table 6-1. For example, for a five-year loan at 8 percent annual interest, skim down the Periods column (on the left) until you find 5, and then follow that row to the right until you hit the 8.00% column. In this case, the factor inside the intersection of row 5 and column 8.0% is 0.6805. If the decimal is extended one more place, the more precise factor is 0.68058. Use that more precise factor for this analysis. 2. Multiply the present value factor you found in Step 1 by the future value of the loan amount to find the present value. In this example, the face amount (future value) of the loan amount is $20,000, so to find the present value of $20,000, take $20,000 × 0.68058 = $13,611.60 (rounded to $13,612). This is the present value of $20,000, discounted at 8 percent for five years. 3. Subtract the present value from the future value to determine the discount. The discount is $20,000 face amount (future value) – $13,612 (present value) = $6,388. Figure 6-1 shows how to journalize this transaction. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 410 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Table 6-1 Present Value of $1 Lookup Table Periods 7.0% 7.5% 8.0% 8.5% 1 0.9345 0.9302 0.9259 0.9216 2 0.8734 0.8653 0.8573 0.8494 3 0.8162 0.8049 0.7938 0.7829 4 0.7628 0.7488 0.7350 0.7215 5 0.7129 0.6965 0.6805 0.6650 Figure 6-1: Journalizing a zero-rateinterestbearing note payable. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The discount on a notes payable account is a contra liability account. It follows the note payable, amortized over the five-year life. The process of amortization moves the discount balance (in the balance sheet) to the income statement via interest expense by using the effective interest method. Figure 6-2 gives you a bird’s-eye view on how this works, assuming that the effective interest rate is 8 percent. Journalize the first year by debiting interest expense for $1,089 and crediting discounts on notes payable for the same amount. For the second year, debit interest expense for $1,176 and credit discounts on notes payable for the same amount — and so on for the remaining three years. Note these points regarding amortization: ✓ The carrying amount of the note increases to face amount ($20,000) over the life of the note payable (five years). ✓ The entire discount balance ($6,388) is moved to interest expense over the same five-year life of the note payable. No-face, interest bearing Now that you’ve tackled zero-interest-bearing notes payables, you can dig into interest-bearing notes. Going back to the $20,000 example from the “No-face, no-interest” section, assume the note payable has a stated (face) interest rate of 6 percent. At that stated rate, interest is $1,200 per year ($20,000 × 0.06). The borrower pays interest to the lender at the end of each year. Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations 411 Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Figure 6-2: Discount amortization schedule: zero-rateinterestbearing note. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Note that the stated interest rate on the note payable is 6 percent. However, both the cash interest payments ($1,200 per year) and the principal amount are discounted based on an 8-percent rate. You know that the present value of the principal is $13,612. However, you also need to figure out the present value of the interest portion of the note. Use Table 6-2 to find the present value of an annuity of $1 table. Because the interest paid is a series of payments for the same amount, the payments are referred to as an annuity. When you calculate the present value of the note payable (Table 6-1), it’s the present value of a single amount. Table 6-2 Present Value of an Annuity $1 Lookup Table Periods 6% 8% 10% 1 0.9434 0.9259 0.9091 2 1.8334 1.7833 1.7355 3 2.6730 2.5771 2.4869 4 3.4651 3.3121 3.1699 5 4.2124 3.9927 3.7908 412 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business The factor at the intersection of 8 percent and five years in the present value of an annuity of $1 table is 3.9927. The present value of the interest is $4,791 (rounded) ($1,200 × 3.9927). Add the two present value figures to get the carrying value of the note, which is $18,403 ($13,612 + $4,791). Subtract $18,403 from the face value of the note payable to get the discount of $1,597 ($20,000 – $18,403). Figure 6-3 shows how to journalize this transaction, and Figure 6-4 gives you the lowdown on the amortization table used to prepare the journal entry. Figure 6-3: Recording discounted note payable. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Figure 6-4: Discount amortization schedule: interestbearing note payable. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations 413 To record the borrower’s interest payment at the end of each year, journalize the first year by crediting discounts on notes payable for $272 and debiting interest expense for $1,472. The credit goes to cash for $1,200. For the second year, you credit discounts on notes payable for $294, debit interest expenses for $1,494, and credit cash for $1,200 — and so on for the remaining three years. Discussing mortgages payable The most common type of note payable is a mortgage, which is used to finance the purchase of real property assets such as land and buildings. The property collateralizes the mortgage, which means the property is held as security on the mortgage. If the company defaults on the mortgage, the lending institution seizes the property and sells it in an attempt to recover as much of the loan balance as possible. Mortgages require a formal closing procedure that’s typically done at the offices of a title company, an independent middleman that coordinates the rights and obligations during the sale for the buyer, seller, and mortgage company. As in the purchase of a personal residence, reams of paperwork (such as the mortgage document and the transfer of the property’s title) are passed back and forth among the buyer, seller, and closing agent for approval and signature. Another type of long-term debt involves capitalized leases. A company doesn’t always buy its fixed assets — sometimes it leases them. In this scenario, the lessee, the person leasing the property, records the capital lease as both a leased asset and a leased liability. Read more about accounting for leases in Book VIII, Chapter 4. Treasury bonds defined Treasury bonds are debt the government of the United States issues to pay for government projects. As with any bond, repayment of principal is ­accompanied by a fixed (or variable in some new, inflation-proof U.S. bonds) interest rate. Treasury bonds have nothing to do with treasury stock, which is corporate stock the issuing corporation buys back from investors. See Book IV, Chapter 5 for more about treasury stock. To understand how to account for corporate bond debt, see the “Accounting for Bonds” section in this chapter. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 414 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business The dark side of debt-free If a company pays off a debt (whether a note or a bond) early, the company must determine whether a gain or loss was incurred on the transaction. (Paying off a debt early is also referred to as debt extinguishment.) With an early payoff, any unamortized discount or premium on the debt payable is removed from the books. Because the debt is removed, any remaining discount or premium related to the debt should also be removed. This transaction may generate a gain or loss. When computing a gain or loss related to an early payoff, keep these points in mind: ✓ The liability is always debited (reduced) for the face amount of the debt. ✓ Cash is credited (reduced) for the amount paid to remove the debt. ✓ An unamortized discount is credited to adjust the remaining balance to zero. ✓ After you post the first three entries, consider the remaining amount you need in the journal entry to balance debits and credits. If you need a debit, it’s a loss on bond extinguishment. A credit entry would be posted as a gain. Imagine that a company repurchases a note payable for $104,000; the face value is $100,000. It was issued at a discount, and $3,000 of the discount isn’t yet amortized at the date of repurchase. Here’s the journal entry: ✓ Debit bond payable $100,000 and loss on bond extinguishment $7,000 ✓ Credit cash (paid to lender) $104,000 and discount on bond payable $3,000 Remember that a business can remove the debt from its balance sheet only if one of the following occurs: ✓ The debtor pays the creditor and is totally relieved of the obligation. For example, the debt was for $10,000 and the debtor paid the creditor the full $10,000 plus all required interest. ✓ The creditor legally releases the debtor from any further obligation. For example, the creditor agrees to cancel a portion of the debt. This chapter doesn’t discuss troubled debt restructuring, which is an advanced financial accounting topic. This takes place when terms of the debt are modified for market or legal reasons. A good example is when the financial institution lowers the interest rate. Another example is a short sale of a home, in which the lender allows the homeowners to sell the home for less than the balance due on the loan, so the homeowners can get out from under a home they can’t afford and the borrower can recoup a portion of the principal. Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations 415 Accounting for Bonds Bonds are long-term lending agreements between a borrower and a lender. For example, when a municipality (such as a city, county, town, or village) needs to build new roads or a hospital, it issues bonds to finance the project. Corporations generally issue bonds to raise money for capital expenditures, operations, and acquisitions. The selling price of bonds, like publicly traded stock, is normally set by what the market will bear. The issuer of the bond sets the interest rate, which is known as the stated, coupon, face, or nominal rate. All four terms mean the same thing — the interest rate stated in the bond indenture. A bond indenture is similar to any type of legal financing document that you may have signed to finance a house or car. It describes the key terms of the bond issuance, including maturity date and interest rate. The people who purchase a bond receive interest payments during the bond’s term (or for as long as they hold the bond) at the bond’s stated interest rate. When the bond matures (the term of the bond expires), the company pays back the bondholder the bond’s face value. A bond is either a source of financing or an investment, depending on which side of the transaction you’re looking at. Because this is a chapter on longterm liabilities, most of the text looks at this transaction from the source of financing viewpoint. Valuing bonds payable A company can issue bonds either at face value (also known as par value), which is the principal amount printed on the bond; at a discount, which is less than face value; or at a premium, which means the bond sells for more than its face value. Usually face value is set in denominations of $1,000. Understanding premiums, discounts, and yields To understand the value placed on a bond, you need to know the relationship between bonds prices and yield to maturity. Yield to maturity can be thought of as an investor’s total return on a bond. The total return has two components: ✓ Interest income earned on the bond. ✓ If the bond is purchased at a discount, the investor is paid the face amount at maturity. The difference between the discount and the face amount is a gain. The gain adds to the total return on the bond. A bond purchased at premium results in a loss when the investor is paid the face amount. The loss reduces the investor’s total return on the bond. Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 416 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business Going over the effective interest rate Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) prefers the effective interest method when accounting for bonds issued at a discount or a premium. When using the effective interest method, you amortize by using the carrying value of the bonds, which is face amount plus unamortized premium or minus unamortized discount. You see the effective interest method used to amortize the no-face, no-interest note payable (see “No-face, no-interest” earlier in this chapter). In that instance, the discount represents the interest earned by the lender over time. Check out Figure 6-2. The carrying amount started as the cash received by the issuer when the note payable was issued. That amount can also be stated as the face amount less the unamortized discount, or $20,000 – $6,388 = $13,612. Over time, the carrying amount is increased by the discount amortization each year. At the note’s maturity, the carrying amount is equal to the face amount, $20,000. If you’re the borrower, the amortization of the discount generates more interest expense to you (see Figure 6-2). For the investor, amortization of the discount generates more interest income. In either case, amortization increases the carrying amount until it equals the face amount. GAAP allows the straight-line method if the result is materially the same: straight-line method versus effective interest rate method. Keep in mind that International Financial Accounting Standards (IFRS) requires use of the effective interest method. Figuring out the present value of a bond In many ways, this present value process is the same as the concepts used for notes payable. Assume a company issues a $100,000 bond due in four years paying seven percent interest annually at year-end. Here are the steps to compute the present value of the bond: 1. Compute annual interest expense. The interest expense is $100,000 × 0.07 = $7,000 interest expense per year. 2. Find the market interest rate for similar bonds. You can check a financial publication, such as The Wall Street Journal, for current market rates on bonds. The market interest rate may differ from the rate actually being paid. You want the market rate, because in the next step you use the market rate to look up the present value factor for the interest payments. Assume that the market rate for similar bonds is 11 percent. Specifically, similar bonds (with similar credit rating, stated interest rate, and maturity date) are priced to yield 11 percent. Because the stated rate is 7 percent, the bond must be priced at a discount. The discount is amortized into income, which increases the yield to maturity (see “Understanding premiums, discounts, and yields” earlier in this chapter for details). Chapter 6: Planning for Long-Term Obligations 417 3. Find the present value factors for the face value of the bond and interest payments. Use the present value of $1 table to find the present value factor for the bond’s face amount. Use the present value of an annuity table to find the present value factor for the interest payments. In each case, find the factor for four periods (years) at 11 percent interest. In this example, the present value factor for the bond’s face amount is 0.65873, and the present value factor of the interest payments is 3.1025. Search the web to find a present value of $1 table and a present value of an annuity table. Look for tables that list the factors out to the fifth decimal place. 4. Use the present value factors to calculate the present value of each amount in dollars. The present value of the bond is $100,000 × 0.65873 = $65,873. The present value of the interest payments is $7,000 × 3.10245 = $21,717, with rounding. 5. Add the present value of the two cash flows to determine the total present value of the bond. In this example, $65,873 + $21,717 = $87,590. Issuing at face value This one is the easiest type of bond transaction to account for. The journal entry to record bonds that a company issues at face value is to debit cash and credit bonds payable. So if the corporation issues bonds for $100,000 with a five-year term, at 10 percent, the journal entry to record the bonds is to debit cash for $100,000 and to credit bonds payable for $100,000. Face value (or face amount) refers to the amount of debt stated on the face of the bond certificate. It represents the amount that must be repaid at maturity. For bonds, par value has the same meaning as face value. This section uses the term face value, because that term refers to the amount stated on the bond certificate. Mulling over bond pricing Bond prices are expressed as a percentage of par value (face amount). A bond with a face amount of $1,000 may have a bond price of 100, or 100 percent of par value ($1,000). Bonds issued at a premium have a bond price of more than 100. For example, a price of 102 means 102 percent of par value. In this case, a $1,000 bond’s price would be $1,020. A bond priced at 98 (a discount), would have a price of $980 per $1,000 bond. Calculating interest payments Interest payments don’t change, regardless of whether the bond is priced at par, a premium, or a discount. To calculate interest payments on a bond, multiply the principal amount by the interest rate stated on the face of the certificate (stated rate). For example, suppose the stated rate of a bond Book VI Planning and Budgeting for Your Business 418 Book VI: Planning and Budgeting for Your Business is 10 percent, interest is to be paid semiannually (every six months), the bonds are issued on July 1, and the first interest payment isn’t due until December 31. The interest payment is principal multiplied by interest rate multiplied by time; in this case, $100,000 × 0.10 × ½ = $5,000. So your journal entry on December 31 is to debit bond interest expense for $5,000 and credit cash for $5,000. The interest expense may change, depending on whether the bond is priced at a premium or a discount. However, the cash payment for interest is fixed. See Book IV, Chapter 4 for examples of issuing bonds at both a premium and a discount. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions Discover ways to fix bottlenecks, increase efficiency, and lower production costs at www.dummies.com/extras/accountingaio. In this book… ✓ Estimate production cost by using job costing and process costing and use either of those values to ballpark a profitable price to charge for a product. Set the right price from the get-go. ✓ Calculate the product cost based on activities that go into manufacturing and selling the product, so your cost per product and pricing are more accurate. Find out what peanut-butter costing is and why and how to avoid it. ✓ Analyze a product’s break-even point, target profit, and margin of safety. Savvy business owners use these tools to plan production and sales levels. ✓ Calculate variance into the pricing equation to avoid any nasty surprises. Variance analysis compares budgeting plans with actual results. ✓ Survey various pricing models to make smart pricing decisions. Decide which pricing method will cover all your costs and generate a reasonable profit. ✓ Size up the financial condition of your business and recognize the most common early warning signs of financial trouble. Use the results to improve your business. Chapter 1 Estimating Costs with Job Costing In This Chapter ▶ Going over how job costing works ▶ Identifying cost objects ▶ Using job costs to price a product or service ▶ Reviewing the flow of costs through a manufacturing system J ob costing is a methodology you use when the costs to manufacture a product or provide a service vary according to each customer’s unique needs. Job costing allows you to provide detailed price estimates based on the product or service provided. A roofing business, for example, uses job costing, because the cost varies according to the customer’s needs. The amount of material depends on the type of roof and the square footage. Labor time varies, depending on the roof’s size, pitch, and unique angles. A cost object is the product, activity, or process that causes your company to incur costs. In this chapter, you see how to assign costs to the cost object. You also find out how to follow the flow of manufacturing costs as a product moves through the production process. Understanding How Job Costing Works For some businesses, nearly every customer job has different costs, and that’s where job costing asserts its value. You need a job costing estimate in order to get the customer’s business, and you need to track costs accurately so you generate a reasonable profit. The different costs for different jobs are often self-evident. Material costs, labor hours, mileage cost, and type of equipment used are likely to vary. For example, a tree trimming company incurs more costs to remove a 30-foot tree than to remove a small stump. The big tree takes more labor and different equipment. 422 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Some factors could lower costs and make a business more competitive in price (or improve its bottom line). For example, a tree trimming company working on a job in a certain neighborhood may distribute a flyer offering free estimates to other homes in the neighborhood. It’s a smart business move. If the tree-trimming services already stands to incur the cost to locate its employees and equipment in a certain area, why not perform as much work as possible while it’s there? The business can spread some costs (mileage, for example) over several jobs. As a result, its cost per job in that neighborhood is lower, boosting its profit. The business lesson is that a little bit of flyer can go a long way. Cost objects: The sponges that absorb money A cost object is anything that causes you to incur costs. Think about a cost object as a sponge that absorbs your money. The object can be a customer, job, product line, or company division. Carefully identifying cost objects helps you cost your product or service accurately. Assume you manage a group of plumbers. You’re reviewing the month’s mileage expense (the equivalent of gasoline) for your staff and notice a 20 percent increase from the prior month. Why? You start asking questions. As it turns out, the customer demand for plumbing work required your staff to drive more miles. The average customer lived farther away. You grumble, “That driving ran up a lot of costs!” Yes, it did, and you do the driving to meet the needs of your customers. In this example, the cost object was the group of customers for the month. Without any customers, you wouldn’t have paid for all the gas. (Well, you wouldn’t have had any income either, but never mind that.) No cost object means no costs incurred. Direct costs are traced to the cost object, and indirect costs are allocated to the cost object. Indirect costs can be fixed or variable. Insurance costs on vehicles are a fixed indirect cost. The premiums are fixed, and the cost is indirect to the job because you can’t trace the vehicle insurance cost directly to a specific job. Utility costs for the office (such as heating and cooling) are variable indirect costs. Costs vary with the weather, but as with the insurance premiums, you can’t trace them directly to any one job. Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 423 Here’s how fixed and variable costs are assigned to cost objects: ✓ Direct costs Variable direct costs, such as denim material, where denim jeans are the cost object Fixed direct costs, such as a supervisor salary at an auto plant, where an automobile produced is the cost object ✓ Indirect costs Variable indirect costs, such as utility costs for a television plant, where a television produced is the cost object Fixed indirect costs, such as insurance for a plumbing vehicle, where a plumbing job is the cost object Charging customers for direct and indirect costs To bill a customer and calculate a profit, you add up all the costs for that ­customer, whether they’re direct or indirect costs. Book VII If, for example, you manufacture kitchen countertops, you include all direct and indirect costs of a custom countertop installation in order to bill the customer. A direct cost may be marble (for material). To find the total cost of material for the job, you compute direct material cost as Marble × Square footage used × Cost per square foot. Indirect costs are different. If your kitchen countertop business makes lease payments on an office building, the cost is indirect. You can’t know the exact amount of indirect costs for the client. You also can’t trace the cost directly to a specific customer, but you can allocate it by using a cost allocation base. For job costs to be accurate, you need to collect information before you bill the client. You also need to consider the difference between your cost estimate and the final bill. Your client needs to understand how costs higher than the estimate will be handled. Should the customer expect to pay it, or will you absorb the cost (and lower your profit)? If this isn’t handled correctly, the customer may be upset. Unforeseen things happen, of course, and you should explain when you hand the customer the estimate that the final bill may be different. A customer is likely to accept additional labor costs. That’s because the exact cost of labor is probably hard for you to predict. Making Savvy Business Decisions 424 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Allocating indirect costs Think about allocating indirect costs this way: You need to allocate a dollar amount of cost (say, $100). You spread that cost over a group of customers, a level of production, or some other activity level. In this section, you see how that may work. A carpenter owns trucks that require repair and maintenance expense. That cost can’t be traced to specific customers; instead, these indirect costs are allocated to a cost object. You find a “best” method to assign repair and maintenance expense to clients, perhaps labor hours worked for the customer. The logic is that if you work more hours for a specific customer, you probably use your truck more. If you use the truck more, that customer should absorb more of your truck’s repair and maintenance cost. Tracing the repair and maintenance cost of the truck back to a specific c­ustomer is virtually impossible. So you make your best educated guess to distribute the cost. Defining cost allocation Cost allocation is the process of connecting an indirect cost to a cost object. A cost pool is a grouping of similar costs. You can think of a cost pool as a bunch of similar cost objects thrown together. In this case, the cost object is a specific job. A cost driver is an item that changes the total costs. If you drive the trucks more, they require more repair and maintenance. An activity (driving to see customers) drives up your costs (repair and maintenance). Just to clarify: The cost object is the “sponge” that absorbs the cost. The cost driver adds to the size of the sponge. A bigger sponge absorbs more cost. Assume the total repair and maintenance expense for three carpentry trucks is $3,000. During the month, your workers provide service to 300 clients. Each customer is allocated $10 of repair and maintenance expense ($3,000 ÷ 300 clients). If the cost driver increases to 400 clients per month, the carpenters drive more miles. As a result, the trucks require more maintenance and possibly repairs. Your monthly repair and maintenance expense is higher. At 400 customers for the month, assume total repair and maintenance expense for three carpentry trucks is $3,600. Now each customer is allocated repair expense of $9 ($3,600 ÷ 400 clients). The cost driver increase Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 425 (number of customers) changes your total cost to $3,600. Because you also have an increase in total customers (400), the $3,600 is spread over a larger group. The total cost increases, but the cost allocated per customer declines. You can see how the cost allocation process can get complicated. Grouping similar costs into the same cost pool is often beneficial when the cost driver is the same. Consider a cost pool for the indirect costs for the carpentry trucks. In addition to repair and maintenance expense, the company pays for insurance and depreciation on the three trucks. None of these costs can be traced to a specific customer; instead, you need to allocate these costs. A good cost pool includes depreciation, insurance, and repair costs on the trucks. This cost pool can be allocated in the same way as the repair and maintenance costs in the previous example. Implementing job costing in manufacturing: An example To implement job costing in a manufacturing company, first think about dividing your costs into two piles: direct costs and indirect costs. In a manufacturing setting, you have direct materials and direct labor you can trace directly to any given job. So far, so good. Next, think about what’s driving indirect costs. You spread those indirect costs to the work you perform. As an example, Reliable Fencing manufactures and installs wooden fences for the residential market. Reliable has a manufacturing component and a service component. Reliable provides the customer a cost estimate. The estimate is based on the type of fence, fence height and length, and labor hours needed for installation. Because nearly every job has a different set of costs, Reliable Fencing uses job costing. This system allows Reliable to compute costs accurately. And from that, Reliable can calculate a selling price that generates a reasonable profit. Imagine that you’re the manager of Reliable Fencing. The Johnsons have requested an estimate for a fence in their backyard. To provide the estimate, you discuss the fence models and types with them. You measure the length needed for the fence and the height requested. Finally, you consider any extra labor costs you may incur. For example, the Johnsons want the fence to jog around several trees so the fence doesn’t damage the tree trunks. The Johnsons’ fence is the cost object. Reliable will incur costs if the client orders a fence and work starts on the project. But before getting an order, you have to provide a cost estimate. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 426 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figuring out direct costs Reliable combines the cost of wood, paint, and a waterproofing treatment for the wood. That combined cost represents direct materials. As the manager, you compute direct material costs: Direct materials = Quantity of materials × Unit price paid for material You buy material measured in square feet. The unit cost is the price per square foot. Here’s the amount of material needed and the cost: Direct materials = 600 square feet of material needed × $5 per square foot Direct materials = $3,000 Your other direct cost is direct labor. Your staff must cut the wood, paint it, waterproof it, and build the fence. Thinking through it further, your staff must measure and dig postholes. They then fill the area around the posts and nail the fence boards onto the posts, all while keeping everything level. Not easy! It takes real skill and planning. As a result, the owners of Reliable Fencing know it’s best to hire skilled people and pay them a reasonable hourly rate. Your experience as Reliable’s manager allows you to estimate the labor time needed based on several factors. You consider the square footage of material needed; the length and height of the fence; and any extra work, such as going around those tree trunks. Here’s your formula for direct labor costs: Direct labor = Hours of labor × Rate paid for labor Note a difference in terms: Price is used for materials, and rate is the term used for labor. That distinction comes up in the world of cost variances. You estimate that 2 people working 20 hours can complete the job. Using these numbers, you determine the labor cost: Direct labor = Number of workers × Hours of labor per worker × Hourly rate paid for labor Direct labor = 2 workers × 20 hours × $20 per hour Direct labor = $800 Consider one more direct cost. You see a discussion of mileage expense earlier in chapter. That formula is also used here: Cost per mile = Cost per gallon of gas ÷ Miles per gallon for the vehicle Mileage costs = Miles needed for client × Cost per mile Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 427 You calculate 15 miles (round trip) from your office to the job site. However, the work will be completed over several days, so you estimate 45 total miles. Your trucks get 20 miles to the gallon, and your fuel cost is $4 per gallon. It’s not much, but here is the direct cost for mileage: Cost per mile = $4 gallon of gas ÷ 20 miles per gallon Cost per mile = $0.20 per mile Mileage costs = 45 miles needed for client × $0.20 per mile Mileage costs = $9.00 So you have three direct costs: materials, labor, and mileage. They’re direct costs because they can be traced to the cost object: the Johnsons’ fence. Calculating indirect costs To allocate indirect costs, you decide on two cost pools. One pool is your vehicle and equipment costs, which includes depreciation, maintenance, repair, and insurance costs. The other pool is office cost, which includes salary, benefits, accounting costs, and legal costs for your company. The cost object for allocating these indirect costs is the customer base: Vehicle and equipment costs Office cost Customers serviced $4,000 $7,000 200 After you resolve how to allocate costs, try to keep it simple. You combine the indirect costs into one amount: $4,000 + $7,000 = $11,000. You then divide the indirect cost total by the number of clients for the month: Indirect cost allocation rate = $11,000 ÷ 200 customers = $55 per customer Indirect cost allocation rate = $55 per customer Your office assistant asks a question: “Is that really fair? What if one client has a $3,000 job, and another’s project is only $500? Should we be charging the same amount of costs to both?” You think about the issue over lunch. After lunch, you stop by your office assistant’s desk and say: “You know, a client should expect that if we show up for a job of any size we’re going to incur some office and vehicle costs. I don’t think a client will be surprised by those fees.” Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 428 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions The assistant thinks for a minute. “Yeah, that’s fair. If they showed up at my house for a job, those indirect costs seem okay. I guess I’d expect to pay for it somehow. As long as the cost charged to a small job isn’t huge, I think charging a rate per customer is reasonable.” The discussion with your office assistant may convince you that your indirect cost allocation should be more specific. If you could show the client how the specific job generates indirect costs, he or she would be more inclined to agree with your billing. You need to weigh the cost and time needed to allocate costs with the benefit of knowing more specific information. If customers generally accept the $55 allocation rate as reasonable, great. Probably no reason to dig further into your indirect costs. If the majority of your customers have a problem with the rate, you should consider more detailed analysis and present a more detailed indirect cost billing. If not, you may lose the opportunity to do more work with the same group of clients. Presenting total job costs Table 1-1 shows the total costs for the Johnsons’ fence job. Table 1-1 Job Cost Sheet — Johnson Fence Job Cost Type Amount or Quantity Price or Rate Total Cost Direct material 600 square feet $5 per square foot Direct labor 40 hours $20 per hour Mileage 45 miles $0.20 per mile $9 Indirect costs 1 customer $55 allocation $55 Total job costs $3,000 $800 $3,864 Taking a Closer Look at Indirect Costs by Using Normal Costing In this section, you apply indirect costs to your product or service. You also plan direct and indirect costs by using a normal costing system. Actual costs represent what comes out of your checkbook. You determine actual costs after the work is completed. Normal costing instead uses budgeted data, which is generated before the work is completed. Normal costing uses a budgeted price or rate multiplied by the actual quantity used. Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 429 Planning your work without some budgeted rates of cost is difficult. Normal costing creates budgeted rates that you can use to plan your work. Although normal costs may not equal your actual costs, they do give you a basis for planning your spending each period. Suppose you operate a landscaping company. Changes in costs can make planning difficult. Maybe the costs you pay for materials, labor, and other costs change as the year progresses. The cost of grass seed may go up, increasing your material costs. Or your labor costs decline because the economy slows. More people with the needed skills are looking for landscaping work, so you can offer a lower pay rate. If you use actual costs, which change over time, pricing your product to generate a reasonable profit is difficult. For example, if you had a 15 percent profit above costs, a cost increase would eat away at your profit. Maybe higher costs lower your profit to 10 percent. Planning your cash needs is also more challenging. If you need to buy $10,000 of grass seed in the next 30 days, what if the price goes up? Maybe a shortage increases your grass seed cost to $12,000. That means that the check you need to write will be $12,000, not $10,000. Now you need to have $2,000 more cash available. Budgeting and cash management is similar to planning a vacation. First, you determine the costs (airline, car rental, hotel, gas). Next, you plan your cash flow to pay for the vacation cost. If the prices are constantly fluctuating, planning is difficult. Many people try to book a vacation trip well in advance, so at least airfare and lodging costs are fixed for the trip! Budgeting for indirect costs When you budget for indirect costs, you spread those costs to cost objects based on a cost driver (refer to the section “Cost objects: The sponges that absorb money”). Before you spread the indirect cost, you come up with a rate to allocate the costs to the product or service. The indirect cost rate allows you to price your product to produce a reasonable profit. As the manager for the landscaping company, you decide on a cost pool for indirect costs. Your only indirect cost is for vehicles and equipment (depreciation, insurance, and repair costs). Your company is new, with virtually no office costs to consider yet. Many companies have planning meetings around the end of their fiscal (­business) year. In the meetings, they make assumptions about many issues, including next year’s costs. This is when a company plans predetermined or Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 430 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions budgeted indirect cost rate. The predetermined overhead rate depends on total indirect costs and the cost driver you select. Indirect costs are also referred to as overhead costs. During a planning session, you consider the prices and rates you paid last year. You think about how prices and rates have changed and consider your estimates of miles driven each month. Based on that analysis, here is your budgeted indirect cost rate: Predetermined or budgeted indirect cost rate = $7,500 ÷ 1,400 miles = $5.36 per mile Not until the end of the year does the company know what the actual total indirect costs and the actual miles driven will be. Here’s the actual indirect cost rate for the vehicles and equipment (using miles driven for the month as the cost object). The formula is explained in the section “Computing direct costs and indirect costs”: Indirect cost allocation rate = $8,000 ÷ 1,300 miles = $6.15 per mile Predetermined or budgeted means planned in advance. Your budgeted monthly rate has a lower monthly cost level ($7,500 versus $8,000) but more monthly miles (1,400 versus 1,300). As a result, the budgeted overhead rate is lower. You use this rate to apply indirect costs to every job during the year. At the end of the year, you realize that you didn’t allocate enough costs to your jobs. As a result, your actual profit will be lower than what you budgeted. Because actual costs aren’t known until the end of the year, you almost always have a difference between budgeted and actual results. Following a normal job costing system Put together your budgeting process for indirect costs with a plan for direct costs. Think of the combined process as normal costing. This chapter keeps hammering away at this point, but it’s important: You trace direct costs and allocate indirect costs. Normal costing combines indirect cost rate with actual production. The ­process gets you closer to actual total costs for your product. Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 431 Computing direct costs and indirect costs To implement normal costing, you compute direct and indirect costs: ✓ Direct costs: Traced to the cost object by multiplying actual prices and/ or rates × actual quantity for a specific job object ✓ Indirect costs: Allocated to the cost object by multiplying predetermined or budgeted indirect cost rate × actual quantity for a specific job object Note that both direct and indirect costs use actual quantity in the formula. While you come up with an indirect cost rate in planning, the rate is multiplied by actual quantities. In this case, the quantity is jobs for the month. Introducing the job cost sheet A job cost sheet lists every cost incurred for a particular job, including direct material, direct labor, and all indirect costs. The job cost sheet is your basis for computing your sale price and your profit. You use this document to prepare a cost estimate for a client. Table 1-2 shows a job cost sheet using normal costing for a landscaping job. Because some job costs are based on budgets and estimates, many businesses round the calculations. You see that total costs are rounded in Table 1-2. Table 1-2 Normal Job Cost Sheet — Landscaping Job Cost Type Amount or Quantity Price or Rate Direct material 100 square feet of grass seed $12 per square foot Direct labor 15 hours of labor $15 per hour Mileage 30 miles driven $0.18 per mile $5 Indirect costs 30 miles driven $5.36 per mile $161 Total job costs Total Cost (Rounded) $1,200 $225 $1,591 The indirect cost calculation (vehicle and equipment costs) uses the actual quantity (miles driven) and the estimated rate per mile. The other direct costs on the job sheet use actual quantities and actual prices/rates. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 432 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Following the Flow of Costs through a Manufacturing System Costs flow through a manufacturing system, from buying materials for a product all the way to the customer sale. When you envision the flow of costs, you find it easier to collect all the product costs you need to price a product. When you know all the steps, you remember all the costs related to those steps! The manufacturing process described in the following sections assumes the company uses process costing. Process costing assumes that each product manufactured is similar to the others, maybe even identical. As a result, you can track costs as they move from one production department to another. You don’t need to track costs by each customer or each customer job. Control starts with control accounts Control accounts are temporary holding places for costs. Managing costs has to start somewhere, and in accounting, that process most often starts with control accounts. Labor, materials, and indirect costs start off in control accounts. It may sound strange, but these accounts and their balances don’t appear in the financial statements. That’s because the balances are eventually moved to other accounts. All the checks you write for manufacturing costs are posted first to control accounts. For many manufacturers and retailers, inventory is the biggest investment; more cash is spent on inventory than any other asset. Because of that, a big part of operating a profitable business is to control the costs of inventory. Inventory is an asset you eventually sell to someone. (That’s a little different, of course, from buildings and equipment.) For manufacturers, inventory has three components: raw materials, work-in-process, and finished goods, whereas retailers just have finished goods. Raw materials inventory is, broadly, products not yet started; work-in-process inventory is partially completed products; and finished goods inventory is completed products. The three kinds of inventory are assets, because you eventually sell the goods to a customer. When you do, the inventory asset becomes an expense — cost of goods sold. Managing inventory starts in a control account. Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 433 Following are the three major categories of control accounts. The amounts in each of these accounts are eventually moved into production. ✓ Materials: You buy materials (such as wood for making kitchen cabinets) in advance of making your products. Materials control is the term for the control account for material costs. ✓ Labor: Consider labor costs. Employees report the hours they work on time cards each week. Those cards list hours worked on various projects. For custom cabinets, the time cards list customer jobs that employees completed, and the hours worked. Wages payable control is the term for the control account for labor. ✓ Indirect costs: A business (such as the kitchen cabinet business) has indirect costs (for example, machine repair and maintenance). Your firm has some method to allocate those costs to clients (see “Budgeting for indirect costs”). However, you may not get to the allocation until after you write checks for the cost. Overhead control is the term for the control account for indirect costs. Control accounts (materials, labor, and overhead), work-in-process, and finished goods are inventory accounts, which are assets. Cost of goods sold (COGS) is an expense account. When you make a sale to a customer, you “use up” the asset. The asset becomes an expense. Debiting increases all these accounts, and crediting decreases all these accounts. The balance for any of these accounts is equal to debit balance less credit balance. For more about debits and credits, see Book I, Chapter 2. Walking through a manufacturing cost example Say you’re the manager of Homewood Custom Cabinets. You order $20,000 in lumber. You then take $5,000 of the lumber and start making cabinets for a customer. When you buy the lumber, cash (an asset) goes down, but the material control account (as asset) goes up. The material control account is increased (debited) when you buy the lumber. The material control account balance is decreased (credited) when you take $5,000 in lumber to start using the material for a customer. Now how does your material control account look? Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 434 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Material control account Debit $20,000 Credit $5,000 If the month ends with no other activity, the ending material control balance is $15,000 ($20,000 – $5,000). But the $5,000 doesn’t just vanish. When you put materials into production, you reduce (credit) the material control account and increase (debit) the work-in-process control account. Work-in-process control account Debit $5,000 Credit You reduce one asset (material control account) and increase another asset (work-in-process control account). Now assume that the people on the shop floor finish some cabinets and move $2,000 of the $5,000 work-in-process to finished goods. Work-in-process control account Debit $5,000 Credit $2,000 You reduce one asset (work-in-process control account) and increase another asset (finished good control account). If the month ends with no other activity, the ending balance in work-in-process is $3,000 ($5,000 – $2,000). Again, no money disappears. The “other side” of the transaction hits the finished goods control account. Finished goods control account Debit $2,000 Credit So one more time, you reduce one asset (work-in-process control account) and increase another asset (finished goods control account). Chapter 1: Estimating Costs with Job Costing 435 At some point, you sell what you made. You have $2,000 in finished goods. Because you make custom cabinets, you have one customer identified as the buyer. That customer “raised her hand” and placed an order. The finished goods control account shows this: Finished goods control account Debit $2,000 Credit $2,000 You’re almost home. When goods are sold, you reduce (credit) the finished goods account and increase (debit) cost of goods sold. And that’s an expense account. At last! Cost of goods sold Debit $2,000 Credit The difference between your sale price and the cost of goods sold is your profit. The reason you do this exercise is to fully track where your inventory money is. For custom cabinets, it can be a big deal if you’re building for, say, 20 customers at once. For off-the-shelf cabinets, it can be a very big deal. You may be delivering 2,000 cabinets per month. The flow lets you see where the inventory money is and spot production logjams. Too much in the material control account suggests that you’re overbuying or not producing at the rate you expected. Too much in the work-in-process control account suggests that you’re not producing completed product as planned. Too much in the finished goods control account suggests that you’re not selling and you have “dead inventory.” Applying the methodology to other control accounts Use the same flow process for labor and indirect costs. Labor costs accumulate in the control account until they’re traced to a customer or product line. At that point, the cost moves to work-in-process. When the goods are Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 436 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions completed, the costs move to finished goods. When goods are sold, the cost moves to cost of goods sold. The labor cost process mirrors the system for material costs described in the previous section. For more about cost allocation see the “Budgeting for indirect costs” section earlier in this chapter. For example, you’re recognizing depreciation expense and repair costs on vehicles. Those costs are in an overhead account. You plan a budgeted rate to apply indirect costs to products. As those costs are incurred, the overhead control account is increased (debited). When you allocate indirect costs to a customer or product line, you reduce (credit) the overhead account and increase (debit) work-in-process c ­ ontrol account. After that, the process is the same as with the other control accounts. Costs move from work-in-process to finished goods to cost of sales. Chapter 2 Performing Activity-Based Costing In This Chapter ▶ Understanding peanut butter costing ▶ Designing and implementing an activity-based costing system ▶ Using activity-based costing to increase profits in the budgeting process A s a business owner or manager, you can always use more useful information — information that helps you make informed decisions. Chapter 1 introduces two widely used costing methods: job costing and process costing. Now dig deeper for better information on costs. Pull apart your product or service and find out more about the activities that create cost. The result is an activity-based costing system. With activity-based costing (ABC) you incur costs when production and sales happen. When you take an order over the phone, manufacture a product, or place a box on a delivery truck, the activities generate costs. The activity becomes the focus to assign costs. Because you’re connecting cost to the activity that creates the cost, your cost per product is more accurate, and so is your pricing. Avoiding the Slippery Slope of Peanut Butter Costing Despite the benefits of ABC costing, many business managers use cost smoothing, or peanut butter costing, instead, which spreads costs over a broad range of cost objects. When you spread peanut butter, you smooth it over the entire slice of bread. You don’t pay much attention to how much cost is assigned to any particular part of the bread. Likewise, cost smoothing spreads the cost without paying too much attention to how much cost is assigned to any particular cost object. The trouble is, costs aren’t assigned as accurately as they should be. 438 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Cost allocation is the process of allocating indirect costs to products and services. The cost allocation base is the level of activity you use to assign costs. Maybe you use 1,000 machine hours or 200 labor hours. Also, keep in mind that direct costs are traced to products and services, not allocated. Stroll over to Chapter 1 for more. To understand the benefits of ABC, you need to see the slippery slope of peanut butter costing. Here’s the setup: Say you’re a food distributor. You have five restaurant clients that order meat, fish, and poultry every day. You take orders, package them, and deliver the food to these businesses every day. Your restaurant clients have high expectations; they expect high-quality, fresh food to be delivered quickly so they can prepare their meals. Your order manager handles the details of order processing. Her salary, benefits, and other costs total $5,000 per month, an indirect cost. The cost must be charged to the restaurant clients. You can’t trace the cost of the order manager to your service. Instead, you need to allocate it. The following sections explain how to allocate indirect costs by using one type of activity. You can see that using single indirect cost allocation can lead to errors in assigning costs. Recognizing a single indirect cost allocation A single indirect cost allocation uses one cost pool. (Chapter 1 defines cost pools.) The food distribution setup uses one pool of costs — order manager costs. With ABC, you end up dividing the costs of order management into more cost pools, and you’re better off for it. Everybody pretty much starts by creating a predetermined or budgeted overhead rate (described in Chapter 1). When you plan at the beginning of the year, using a single indirect cost pool, you come up with an overhead rate for the order manager’s cost, such as the following: Annual budgeted indirect cost rate = Cost ÷ orders = $60,000 ÷ 1,250 = $48 per order The order manager’s cost of $5,000 per month amounts to $60,000 per year. The five restaurants order nearly every business day of the year. You figure that total orders will be 1,250 — 250 orders per year from five customers. (Isn’t it great that in samples all customers order exactly the same number of times?) Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing 439 The single indirect cost allocation spreads the cost (order manager) ­uniformly over the cost object (orders). That’s $48 dollars per order. This is an example of peanut butter costing, where all services receive the same or similar amounts of cost. A fly in the peanut butter: Dealing with different levels of client activity If some customers or activities eat up more costs than others, peanut butter costing isn’t a true reflection of the costs. A customer or activity that demands more effort should get a larger cost allocation. So companies that use peanut butter costing miss the chance to allocate costs more precisely. You no doubt know from experience that some customer orders are usually smooth as glass. Other orders, from problem customers, often require your staff to jump through extra hoops. For example, say you notice that your order manager is spending a lot of time with two customers in particular. The Steak Place and Riverside Fishery are making big demands. They change their orders at the last minute at least once a week. When they make this change, the order manager has to cancel the original invoice (the bill), make a new one, and e-mail it. Then she has to change the shipping instructions document; you don’t want the wrong goods put on the truck and sent to the restaurant. So the order manager cancels the original shipping instructions and makes new instructions. “It’s really frustrating,” the manager says. “Sometimes they call so late that I have to call the driver and tell him not to leave the dock. We unload the truck and start over.” Well, no doubt you want to be known for your high level of customer service, but this is getting ridiculous. Another issue is that when the invoice and shipping orders change, the goods coming out of inventory also change. Your pickers are taking products off the shelf, putting them back, and then taking different products. These constant changes eventually lead to mistakes in inventory. A picker may move a product in or out and not record it in the accounting records. And here’s another point to consider: Your business supplies meat, fish, and poultry — items that aren’t known for having a long shelf life. The excesses of The Steak Place and Riverside Fishery may leave you with heaps of spoiled product. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 440 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions You decide to take another run at allocating the office-manager cost. “Why don’t we track the time spent on each client? Let’s try that for three months and see how your time shakes out. It sounds like we should assign more costs to the two customers you mentioned.” You change the cost allocation from orders placed to time spent per customer. After three months, you review the time spent per customer. Fortunately, you’ve been tracking time carefully, and you’re using an excellent spreadsheet program. The office manager works 24 days per month, 8 hours per day. Her total monthly hours are 192 hours (24 days × 8 hours). Table 2-1 shows the ­breakdown. Table 2-1 Order Manager — Monthly Hours Per Customer Restaurant Customer Hours for Month Percent of Total Apple Core Diner 30 15.6 Blue Lantern 30 15.6 Meadowbrook Grill 30 15.6 Riverside Fishery 56 29.2 The Steak Place Total hours 46 24.0 192 100.0 Aha! The situation is just as the order manager described, but now you have some metrics. Half the costing battle is measuring reality to confirm your instincts. With peanut butter costing, you spread the cost evenly. You assigned 20 percent of order-manager costs to each customer. Now you see that two customers account for more than 50 percent (!!!) of the order manager’s effort. The time to reallocate the cost has arrived. Undercosting and overcosting If you use cost smoothing, you’re likely to incur product undercosting or product overcosting. ✓ Product undercosting occurs when a product or service uses more resources (costs) than you assign. ✓ Product overcosting occurs when a product or service uses fewer resources (costs) than you assign. Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing 441 If either of these costing errors occurs, the cost of the product isn’t accurate, and your profit calculation is incorrect. Discussing product-cost cross-subsidization Undercosting or overcosting creates product-cost cross-subsidization, meaning that if you undercost one product, you will overcost another. It’s common sense and simple math. You have a fixed amount of cost to assign. If you’re “over” in one product, you’ll be “under” in another. That situation throws off your cost and profit calculations. Say you have two products, A and B. (Obviously, your marketing department needs to come up with better product names.) The total cost to be allocated is $100. You allocate $50 of costs to product A and $50 to product B. If you overcost product A by $10, you allocate $10 too much. That means you undercost product B by $10. In other words, the actual costs should be $40 for product A and $60 for product B. You start with $100 in your “bucket” of costs. When you allocate too much for product A, too little remains to allocate to product B. Undercosting or overcosting direct costs is relatively easy to figure out and fix. How do you catch mistakes? You trace direct costs, so you can determine the exact cost of material used in production. Undercosting or overcosting of indirect costs is harder to catch. Allocating indirect costs is less precise than tracing direct costs. For example, allocating utility costs in a factory is a bit difficult, but you can do it. The cost accounting “secret” is to invest time investigating the activities that result in utility costs. For example, if one of the manufacturing machines runs twice as long as another, that activity is probably consuming twice as much electricity. The higher machine activity should result in twice as much utility expense. Table 2-1 shows that investigation pays off. Two customers are chewing up more than 50 percent of the order manager’s effort by requiring more hours of her time. The investigation of the activity produces metrics, which form the basis of a better cost allocation plan. For the tools and techniques, see the section “Designing an Activity-Based Costing System,” later in this chapter. Underallocating or overallocating messes up pricing Underallocating or overallocating costs impacts your product price and your profit. If your product costs aren’t accurate, you can’t price your product ­correctly. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 442 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Say you overallocate costs for retailing a men’s dress shirt. You think total shirt cost is $31 in direct and indirect costs, and you want a $10 profit per shirt. You therefore price your shirts at $41. But that may not be correct! If the true cost of the shirt is only $30, $1 is overallocated. As a result, your profit is $11 ($41 – $30). Well, what’s wrong with that? You’d prefer to make $11 a shirt instead of $10. But with that higher price, you may lose some sales. Most people have a price point — a maximum price they’re willing to pay based on the value they perceive. Because the apparel industry is highly price-driven, you could be losing sales, which would hurt your bottom line. If a lot of customers say to themselves, “The most I would pay for that shirt is $40,” you may lose sales by charging $41. Although you make another dollar per shirt at $41, your sales may decline to the point where you make less total profit. A bigger pricing problem may be when a product’s cost is underallocated. Assume that you underallocate another men’s dress shirt by $5. You think the total cost is $50. To make a $10 profit per shirt, you set the sale price at $60, so everything’s fine, right? Wrong! If costs are allocated correctly, the real profit is $5 ($60 – $55). Underallocation has resulted in a sale price that’s too low, and that reduces profit. You can’t make up this deficiency through volume sales. Usually, shirts selling for $60 don’t go flying off the display table. Designing an Activity-Based Costing System If your ABC system is well designed, you allocate costs more precisely. This section helps you carefully separate costs between direct costs and indirect costs. You also consider the specific activities that drive the indirect costs higher. Finally, the indirect costs are allocated to the activities that cause those costs to be incurred. Refining your approach ABC is a refined costing system, or a more specific way to assign costs to cost objects. The system avoids using big, generic categories, such as splitting a cost evenly between divisions. Instead, it allocates indirect costs to the Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing 443 activities that generate those costs. The result is likely to be more accurate costing and product pricing. The refined costing system requires you to perform the following three tasks: ✓ Direct cost tracing: Review your direct costs and categorize more costs as direct costs, if possible. ✓ Cost pools: Review cost pools and create more pools, if necessary. ✓ Cost-allocation bases: Decide on cost-allocation bases by using causeand-effect criteria. Direct costs are traced to cost objects. As a result, the amount of cost is fairly easy to determine. For example, determining the amount of leather used to make the leather handbags is easy. Cost pools should be homogeneous; that is, each of the costs has the same cost allocation base. The costs have a similar cause-and-effect relationship. Therefore, if you have more than one allocation base, you should have more than one cost pool. A good example is a cost pool combining vehicle depreciation, repair and maintenance, and fuel costs. The costs all increase when your vehicles drive more miles. The cost allocation base should be mileage, and you simply allocate a dollar amount of indirect cost per mile driven. Grouping costs by using a cost hierarchy A cost hierarchy groups costs into cost pools based on cost drivers or cost allocation bases. A cost hierarchy has levels, which explain how broadly you look at costs and activities. Here are levels you may use in a cost hierarchy: ✓ Unit-level costs are cost activities performed on an individual unit, whether a product or service. If you make blue jeans, your unit is one pair of jeans. An individual tax return is a unit, if you prepare tax returns for clients. ✓ Batch-level costs are cost activities that generate costs at the batch level. For example, when an automobile plant changes from one car model to another, it’s changing batches and incurring setup costs. The plant is “retooling,” which may include moving machinery, and certainly includes changing out the dies and reprogramming the welding robots. ✓ Customer-level costs are cost activities generated for one customer. If you’re remodeling a kitchen, your labor costs, materials used, and overhead costs incurred for a specific customer are all customer-level costs. Customer-level costs may include multiple orders from the same client. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 444 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions ✓ Product-sustaining costs are cost activities that support a particular product or service line, regardless of the number of units produced. A product-sustaining cost extends the life of a product; technology products are good examples. To stay relevant with customers, software companies come out with endless new versions of software. Extending a product’s life is supposed to keep customers buying it. Design costs can be product-sustaining costs. To keep the technology product current, you change the design. You can allocate product-sustaining costs to a product or to an entire product line (sometime called a “product family” in high tech). ✓ Facility-sustaining costs are cost activities that support the overall company, such as legal and accounting activities. The rent, insurance, and maintenance on the company’s building are facility-sustaining costs, because the building is essential to keeping the entire company running. The costs should be allocated over the entire company. Companies with multiple buildings sometimes cost allocate for each building to see whether a building is too expensive to occupy. If you use a fine-enough granularity, you can get really precise costing. On the other hand, too much granularity will make you crazy. The financial benefit of precise costing should be greater than the time and expense to track the cost information. The financial benefit is more accurate product costs and more precise profit calculations. Testing your ABC design The following example begins by separating direct and indirect costs. You also see descriptions of the activities that generate indirect costs. This example allocates indirect costs and calculates the full cost of the product. For this example, assume you manage a company that makes and installs automobile windshields. You have a forward-looking product called a smart windshield, which uses lasers, infrared sensors, and a camera to help drivers with vision problems drive well. You sell two products: sedan windshields and van windshields. The company wants to implement activity-based costing for indirect costs. Ready, set, go! Dealing with direct costs You begin by sitting down with the production manager to get a handle on direct costs. You produce 1,500 windshields each year (750 for sedans and 750 for vans). You trace $300 of direct materials per windshield and $500 in direct labor per unit. Table 2-2 shows direct costs. Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing Table 2-2 445 Windshield Direct Costs Type of Cost Units × Cost Total Direct material 1,500 units × $300 $450,000 ($225,000 per type) Direct labor 1,500 units × $500 $750,000 ($375,000 per type) Diving into the cost pools Next, you and the production manager list the indirect cost activities to manufacture and install windshields. Your goal is to pull apart the cost pools. In other words, you make sure that each cost pool is based on a specific activity. The more specific the cost pool, the more likely you’re allocating costs to products correctly. Table 2-3 shows the indirect costs for producing and installing windshields. Table 2-3 Indirect Cost Activities — Windshield Production and Installation Activity Description Molding setup Install mold in machine to create a windshield Machine operation Run machine to convert material in mold to a windshield Quality inspection Review product for defects Packaging and delivery Pack windshield; load into truck for delivery to client Installation Install windshield at client location You review to see whether any of these costs are direct costs. That would be good, because it gets you out of the cost allocation business. Using a direct cost traced to a product results in greater precision than using an indirect cost allocated to a product. Applying indirect costs by using a cost allocation base The next step is to link the indirect costs to the cost pools (the activities) by using a cost allocation base. At the start, you agree that labor hours should be used to allocate indirect costs for each activity, except for machine operation. The machine cost is allocated based on machine hours. Table 2-4 allocates each cost pool (activity) based on the total hours required to complete each activity. You perform this analysis for all products. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 446 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Table 2-4 Cost Allocation Rates Activity Allocation Base Molding setup Labor hours Machine operation Machine hours Quality inspection Labor hours Packaging and delivery Installation Total Cost Total Hours Allocation Rate/Hour $20,000 150 $133/hour $500,000 5,700 $88/hour $100,000 1,050 $95/hour Labor hours $50,000 525 $95/hour Labor hours $30,000 900 $33/hour Allocate and celebrate: Assigning the cost allocation rates to the products You have the allocation rate per hour (either machine hours or labor hours). Now decide how many hours to use to apply the rate. The goal is to tie the cost allocation to the activity as closely as possible. Each product has a different mold. Your company changes the windshield being produced by changing the mold. Because of the sedan windshield’s curve, more labor hours are required to set up the sedan’s mold. More machine hours are required to produce the van windshield, simply because the van windshield is bigger. The van’s larger windshield also requires more time to inspect, package, and deliver. Installation costs are the same for both products. Table 2-5 lists the cost ­allocation for each product and the percentage of the total hours for each activity. Table 2-5 Cost Allocation as a Percentage of Total Hours Activity Allocation Rate/Hour Sedan Cost and (Percent Hours) Van Cost and (Percent Hours) Molding setup $133 $13,333 (67%) $6,667 (33%) Machine ­operation $88 $236,842 (47%) $263,158 (53%) Quality ­inspection $95 $42,857 (43%) $57,143 (57%) Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing Activity Allocation Rate/Hour Sedan Cost and (Percent Hours) Van Cost and (Percent Hours) Packaging and delivery $95 $21,429 (43%) $28,571 (57%) Installation $33 $15,000 (50%) $15,000 (50%) 447 At long last, you review the total product costs for sedan and van windshields (see Table 2-6). Table 2-6 Total Costs by Type — Sedan and Van Windshields Type of Costs Sedan (750 Units) Van (750 Units) Total (1,500 Units) Direct material $225,000 $225,000 $450,000 Direct labor $375,000 $375,000 $750,000 Molding setup $13,333 $6,667 $20,000 Machine operation $236,842 $263,158 $500,000 Quality inspection $42,857 $57,143 $100,000 Book VII Packaging and delivery $21,429 $28,571 $50,000 Installation $15,000 $15,000 $30,000 Total costs $929,461 $970,539 $1,900,000 Making Savvy Business Decisions Cost per windshield $1,239.28 $1,294.05 The cost per van windshield ($1,294.05) is slightly higher than the cost per sedan windshield. The higher cost for vans makes sense. You can use the total costs in Table 2-4 and the percentages in Table 2-5 to assign costs. You get the same cost allocation that’s calculated by using the rates per hour in Table 2-5. You need the cost allocation rates to easily assign costs to all of your production. That’s why the rates per hour are important. Take a look at indirect costs. Installation costs are evenly split, so disregard that cost pool. Consider the other indirect costs. Other than molding setup, all the remaining indirect cost pools have a larger allocation to the van. That’s reasonable, because the van windshield is bigger than the sedan windshield. It costs more to run it through a machine, to inspect it, and to package it. 448 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Using Activity-Based Costing to Compute Total Cost, Profit, and Sale Price The only constant is change. Demand for your product is probably always changing. Material costs may increase (they rarely go down). Increased competition may force you to lower your prices to prevent sales from slipping. Luckily for you, activity-based costing is a tool to manage indirect cost allocations effectively as conditions change. Take a look at the following example, which shows how to use cost allocation to compute total cost, profit, and a sale price. Say you operate a lawn care business that provides two services: flower bed planting and care, and lawn planting and care. You plan and price your work based on a 25-squarefoot area. One unit for your business is 25 square feet, whether it’s a lawn or flower bed. You refer to one unit as one customer yard. Table 2-7 shows a summary of the cost objects for the business. Table 2-7 Flower Bed and Lawn Care Costs Type of Costs Flower Bed Lawn Care Direct materials Mulch and fertilizer Sod, grass seed, and fertilizer Direct labor Clear area, plant, or install material Clear area, plant, or install material Estimator cost (indirect cost) Flower bed inspection and analysis Lawn inspection and analysis Transportation cost (indirect cost) Depreciation, i­nsurance for vehicles, and ­mileage Depreciation, insurance for vehicles, and mileage Office cost (indirect cost) Costs for dispatcher/ accountant Costs for dispatcher/ accountant In planning, you determine that your business will service 500 units in the upcoming year. Assume that the sales will be evenly split between the two services (250 yards each). Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing 449 Allocating indirect costs evenly by product Initially, you allocate indirect costs by splitting the indirect costs between the product types. Table 2-8 shows an even allocation of indirect costs. The direct costs are traced to each service you provide, either flower bed work or lawn care. Table 2-8 Costs and Profit by Product — Flower Bed and Lawn Care Cost (250 Units of Each Product) Flower Bed Lawn Care Total Direct material $25,000 $30,000 $55,000 Direct labor $37,500 $25,000 $62,500 Estimator cost (indirect cost) $15,000 $15,000 $30,000 $7,500 $7,500 $15,000 Office cost (indirect cost) $12,500 $12,500 $25,000 Total costs $97,500 $90,000 $187,500 Transportation cost (indirect cost) Add: Profit (10 percent of cost) $9,750 $9,000 $18,750 $107,250 $99,000 $206,250 Cost per unit (yard) $390 $360 Book VII Sale price per unit $429 $396 Making Savvy Business Decisions Total sales Estimator cost, transportation cost, and office cost are evenly split. Now think about profit as a percentage of total costs. In Table 2-8, the flower bed profit calculation is $9,750, or 10 percent of costs ($97,500 × 0.10). To compute your sale price for flower beds, add the total cost to profit. That’s $107,250. Finally, divide both the total cost and total sales by 250 yards. That provides cost per unit of $390 and sale price per unit of $429 for flower beds. Analyzing and reallocating cost activities A key point of activity-based costing is basing each cost pool on a specific activity. This puts you on the road to more accurate costing of your product. To find out more, ask your staff in detail about their activities. The estimator’s job is to discuss each project with the client. She assesses the current condition of the yard and the labor and materials needed for the project. Finally, she supervises the work to completion. You ask your estimator to track the amount of time she spends on each type of product. It’s simple: She will post her time to a flower bed column or a lawn column on a spreadsheet. 450 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions After a few months, you find that the estimator spends 70 percent of her time on flower bed projects. “Flower beds take more time to discuss with the client,” she says. “Most of time, we’re dealing with an existing flower bed. The customer decides what to keep and what to throw out. Lawns are easier. You don’t have much to discuss, other than the current condition of the grass.” Based on this discussion, clearly you should assign 70 percent of the estimator’s cost to the flower bed product. At the same time, the estimator tracks mileage on the trucks and vehicles. “If you look at this map, you’ll see that most of our flower bed work is in the wealthier area of town. That’s farther from our office than most of the lawn work.” She looks through her mileage log. “I calculated that 60 percent of our drive time and mileage is spent on flower bed work.” Okay, more progress! You probably should allocate 60 percent of the transportation costs (vehicle depreciation, insurance, and fuel) to the flower bed product. Your last stop is your office assistant’s desk. “You know we get a lot of cancellations and rescheduled work for lawn care.” He pauses for a minute. “I think because the work isn’t complicated, and we have a lot of competitors, people don’t take it as seriously. They change and cancel without much thought.” Well, a cancellation or rescheduling fee would reduce the problem, but that’s a cost story for another day. For now, just consider the activities that generate office costs. The office assistant’s cost (salary, office supplies, and computer) can be allocated based on his time. When a customer cancels or reschedules, the office assistant spends time on the phone with customers, the estimator, and employees. In addition, the paperwork for the project has to be changed. After more analysis, the two of you decide that 60 percent of the office assistant cost should be allocated to lawn work. Changing allocations to cost pools You investigate indirect costs and make some changes. Table 2-9 shows the cost allocation changes to the three indirect cost pools. The direct costs don’t change, because they’re traced directly, not allocated. Total costs are still $187,500. That makes sense, because activity-based costing changes cost allocations, not cost totals. Costs change by product but not in total for the company. Sales are still $206,250. Because the per unit sale prices stay the same, the profit calculations change. Profit for flower beds is now $4,750 ($107,250 – $102,500). Profit for lawn care is now $14,000 ($99,000 – $85,000). Chapter 2: Performing Activity-Based Costing Table 2-9 Activity-Based Costing by Product — Flower Bed and Lawn Care Cost (250 Units of Each Product) Flower Bed Lawn Care Total Direct material $25,000 $30,000 $55,000 Direct labor $37,500 $25,000 $62,500 Estimator cost (indirect cost) $21,000 $9,000 $30,000 Transportation cost (indirect cost) Office cost (indirect cost) Total costs Profit (total sales less total costs) $9,000 $6,000 $15,000 $10,000 $15,000 $25,000 $102,500 $85,000 $187,500 $4,750 $14,000 $18,750 $107,250 $99,000 $206,250 Cost per unit (yard) $410 $340 Sale price per unit $429 $396 Total sales 451 In Table 2-9, the flower bed total cost increases by $5,000 (from $97,500 to $102,500). As a result, profit for flower beds declines by $5,000 (from $9,750 to $4,750). ABC has the opposite effect on the lawn care business. Lawn care costs go down by $5,000 (from $90,000 to $85,000). Profit increases by $5,000 (from $9,000 to $14,000). Changing prices after ABC You overcosted lawn care and undercosted flower beds. When you reallocate that from lawn care to flower beds, the change throws off your profit calculation! You want a profit of 10 percent for each product, but flower beds are producing only a 4.6 percent profit ($4,750 profit ÷ $102,500 in sales). The lawn care profit produces a 16.5 percent profit ($14,000 ÷ $85,000). See the explanation for the profit and sales numbers earlier in the chapter. Here’s the problem: 4.6 percent may be too small a profit margin. You’re spinning your wheels for a bunch of petunias. Calculate the new sale price for flower beds, based on the ABC and a 10 percent profit, as shown in Table 2-10. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 452 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Table 2-10 Calculating a New Sale Price for Flower Beds Cost (250 Units of Each Product) Flower Beds Total costs in Table 2-9 $102,500 Profit (10 percent of total cost) Total sales $10,250 $112,750 Cost per unit (yard) $410 Sale price per unit $451 The original price per unit for flower beds was $429. The new flower bed unit price is $451, which is $22 higher than before ($451 to $429). To make a 10 percent profit, change the flower bed sale price to $451 per unit. At the old price, you weren’t making your desired profit. Now you will. And that’s the value of using ABC. You could make up for the lower profit on flower beds by earning more on lawn care. But really, you should assess each product on its own and price each one to produce the correct profit. Chapter 3 Examining Contribution Margin In This Chapter ▶ Figuring contribution margin ▶ Meeting income goals with cost-volume-profit analysis ▶ Analyzing your break-even point, target profit, and margin of safety ▶ Exploring operating leverage W hen you have to make a business decision about what to sell, how much of it to sell, or how much to charge, you first need to understand how your decision is likely to affect net income — your profit. Suppose you sell one refrigerator for $999.95. How does that sale affect your net income? Now suppose you sell 1,000 of the same make and model at this price. How does that sales volume affect net income? Contribution margin simplifies these decisions. In this chapter, you find out how to calculate contribution margin and how to apply it to different business decisions, using both graphs and formulas. You also find out how to prepare something called a cost-volume-profit analysis, which explains how the number of products sold affects profits. And you discover how to prepare a break-even analysis, which indicates exactly how many products you must sell in order to break even and start earning a profit. Suppose you set a target profit — a goal for net income this period. This chapter shows you how to estimate the number of units you need to sell in order to meet your target profit. It also explains how to measure something called margin of safety, or how many sales you can afford to lose before your profitability drops to zero. Finally, this chapter explains and demonstrates operating leverage, which measures a company’s riskiness. 454 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Computing Contribution Margin Contribution margin measures how sales affects net income or profits. To compute contribution margin, subtract variable costs of a sale from the amount of the sale itself: Contribution margin = Sales – Variable costs For example, if you sell a gadget for $10 and its variable cost is $6, the contribution margin for the sale is $10 – $6 = $4. Selling this gadget increases your profit by $4, before considering fixed costs. Your contribution margin less fixed costs equals your profit. When computing contribution margin, subtract all variable costs, including variable manufacturing costs and variable selling, general, and administrative costs. Don’t subtract any fixed costs. You compute gross profit by subtracting cost of goods sold from sales. Because cost of goods sold usually includes a mix of fixed and variable costs, gross profit doesn’t equal contribution margin. You can calculate contribution margin in three forms, as discussed in the following sections: in total, per unit, or as a ratio. Contribution margin, in any of its forms, explains how different factors in the company — sales price, sales volume, variable costs, and fixed costs — interact. This understanding helps you make better decisions when planning sales and costs. Figuring total contribution margin Total contribution margin measures the amount of contribution margin earned by the company as a whole. You calculate it by using this formula: Total contribution margin = Total sales – Total variable costs To determine overall profitability, subtract total fixed costs from total contribution margin. Net income equals the excess of contribution margin over fixed costs. You can use total contribution margin to create something called a contribution margin income statement. This document differs from a multi-step income statement (shown in Figure 3-1), where you first subtract cost of goods sold from sales and then subtract selling, general, and administrative costs. Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 455 Figure 3-1: Multi-step income statement. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. A contribution margin income statement first subtracts the variable costs and then subtracts fixed costs, as shown in Figure 3-2. Here, variable costs include variable costs of both manufacturing and selling. Likewise, fixed costs include more manufacturing and selling costs. Figure 3-2: Contribution margin income statement. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The contribution margin income statement makes understanding cost behavior and the way sales will affect profitability easier. In Figure 3-2, the company earns $1,000 in sales, $400 of which goes toward variable costs. This scenario results in $600 of contribution margin. These amounts — sales, variable costs, and contribution margin — change in proportion to each other. If sales increase by 10 percent, then variable costs and contribution margin also increase by 10 percent; $1,100 in sales increases variable costs to $440 and contribution margin to $660. On the other hand, fixed costs always remain the same: The $300 in fixed costs is $300 regardless of any increase or decrease in sales and contribution margin. The contribution margin income statement presents the same net income figure as a traditional income statement. However, the contribution margin income statement isn’t in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). (See Book IV, Chapter 1 for more about GAAP.) Managers can internally use a contribution margin income statement to better understand their own companies’ operations. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 456 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Calculating contribution margin per unit Contribution margin per unit measures how the sale of one additional unit affects net income. You calculate it by subtracting variable costs per unit from sales price per unit, as in this formula: Contribution margin per unit = Sales price per unit – Variable costs per unit Say a company sells a single gadget for $100, and the variable cost of making the gadget is $40. Contribution margin per unit on this gadget equals $100 – $40 = $60. Therefore, selling the gadget increases net income by $60, assuming no change in fixed costs. Increasing the sales price doesn’t affect variable costs because the number of units manufactured, not the sales price, is what usually drives variable manufacturing costs. Therefore, if the gadget company raises its sales price to $105, the variable cost of making the gadget remains at $40, and the contribution per unit increases to $105 – $40 = $65 per unit. The $5 increase in sales price goes straight to the bottom line as net income. Again, this assumes that fixed costs don’t change. Working out contribution margin ratio Contribution margin ratio measures the percentage of each sales dollar that represents net income. To calculate it, divide contribution margin by sales, either in total or per unit: Contribution margin ratio = Total contribution margin ÷ Total sales or Contribution margin ratio = C ontribution margin per unit ÷ Sales price per unit Suppose a gadget selling for $100 per unit brings in $40 per unit of contribution margin. Its contribution margin ratio is 40 percent: Contribution margin ratio = $40 ÷ $100 = 0.40 or 40% To find out how sales affect net income, multiply the contribution margin ratio by the amount of sales. In this example, $1,000 in gadget sales increases net income by $1,000 × 0.40 = $400 (before considering fixed costs). Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 457 Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis Contribution margin indicates how sales affects profitability. When running a business, a decision-maker needs to consider how four different factors affect net income: ✓ Sales price ✓ Sales volume ✓ Variable cost ✓ Fixed cost Cost-volume-profit analysis helps you understand different ways to meet your net income goals. The following sections explain cost-volume-profit analysis by using graphical and formula techniques. These sections pay special attention to computing net income based on different measures of contribution margin: total contribution margin, contribution margin per unit, and the contribution margin ratio. The graphs provide a helpful way to visualize the relationship among cost, volume, and profit. However, when solving problems, you’ll find that plugging numbers into formulas is much quicker and easier. Book VII Drafting a cost-volume-profit graph Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 3-3 visually describes the relationship among cost, volume, and profit for a company called Pemulis Basketballs. It sells its basketballs for $15 per basketball. The variable cost of the basketballs is $6. Pemulis has total fixed costs of $300 per year. In this figure, the fixed costs of $300 are represented by a horizontal line because regardless of the sales volume, fixed costs stay the same. Total variable costs are a diagonal line, starting at the origin (the point in the lowerleft corner of the graph where sales are zero). Total costs (the sum of total variable costs and total fixed costs) are a diagonal line starting at the $300 mark because when the company makes and sells zero units, total costs equal the fixed costs of $300. Total costs then increase with volume. Finally, total sales forms a diagonal line starting at the origin and increasing with sales volume. Figure 3-4 shows when the company will earn net income or incur a loss. When the sales curve exceeds total costs, the company earns net income (represented by the shaded right side of the X in Figure 3-4). However, if total 458 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 3-3: Costvolumeprofit graph. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. sales are too low to exceed total costs, then the company incurs a net loss (the shaded left side of the X). The higher the sales volume — that is, the more sales volume moves to the right of the graph — the higher the company’s net income. Figure 3-4: Identifying net income and loss in a costvolumeprofit graph. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Dropping numbers into the chart shows exactly how much income can be earned at different sales levels. Assuming Pemulis has a sales price of $15 per unit, a variable cost per unit of $6, and total fixed costs of $300, what happens if Pemulis sells 60 basketballs? Total sales come to 60 units × $15 = $900. Total variable costs multiply to 60 units × $6 = $360. Add these total variable costs to total fixed costs of $300 to get total costs of $660. Figure 3-5 illustrates these amounts. Total sales of $900 sits on the Total sales line. Total costs of $660 sits on the Total cost line. The difference between these amounts of $240 represents the net income from selling 60 units. Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 459 Figure 3-5: Applying a costvolumeprofit graph to a specific case. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Trying out the total contribution margin formula The following formula, based on total contribution margin, follows the same structure as the contribution margin income statement. (Flip to the earlier section “Figuring total contribution margin” for details on total contribution margin and its related income statement.) Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs Assume that Pemulis Basketballs sells 60 units for $15 each for total sales of $900 (see the preceding section for more on the origins of this example). The variable cost of each unit is $6 (so total variable costs come to $6 × 60 = $360), and total fixed costs are $300. Using the contribution margin approach, you can find the net income in two easy steps: 1. Calculate total contribution margin. Use the formula provided earlier in the chapter to compute total contribution margin, subtracting total variable costs from total sales: Total contribution margin = Total sales – Total variable costs = (60 × $15) – (60 × $6) = $900 – $360 = $540 Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 460 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions This total contribution margin figure indicates that selling 60 units increases net income by $540 (before considering fixed costs). 2. To calculate net income, subtract the fixed costs from the total contribution margin. Just plug in the numbers from Step 1: Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs = $540 – $300 = $240 Subtracting fixed costs of $300 from total contribution margin of $540 gives you net income of $240. Practicing the contribution margin per unit formula If you know the contribution margin per unit (see “Calculating contribution margin per unit” earlier in this chapter), the following approach lets you use that information to compute net income. Here’s the basic formula equating net income with contribution margin per unit: Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs Say Pemulis Basketballs now wants to use this formula. It can simply plug in the numbers — 60 units sold for $15 each, variable cost of $6 per unit, fixed costs of $300 — and solve. First compute the contribution margin per unit: Contribution margin per unit = Sales price per unit – Variable costs per unit = $15 – $6 = $9 Next, plug contribution margin per unit into the net income formula to figure out net income: Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs = (60 × $9) – $300 = $540 – $300 = $240 Eyeing the contribution margin ratio formula If you want to estimate net income but don’t know total contribution margin and can’t find out the contribution margin per unit, you can use the contribution margin ratio to compute net income. Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 461 As noted in the earlier section “Working out contribution margin ratio,” you can compute contribution margin ratio by dividing total contribution margin by total sales. So if your contribution margin is $540 and your sales is $900, your contribution margin ratio is 60 percent: Contribution margin ratio = Total contribution margin ÷ Total sales = Contribution margin per unit ÷ Sales price per unit = $540 ÷ $900 = 0.60 = 60% This means that 60 cents of every sales dollar increases net income, after considering fixed costs. After you know the contribution margin ratio, you’re ready for the net income formula: Net income = ( Sales volume in units × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs To calculate net income for the earlier example company, plug the ­contribution margin ratio of 60 percent into the formula: Net income = ( Sales volume in units × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs = ($900 × 0.60) – $300 = $540 – $300 = $240 Generating a Break-Even Analysis How much do you need to sell in order to break even? The break-even point (BE) is the amount of sales needed to earn zero profit — enough sales to avoid a loss, but insufficient sales to earn a profit. This section shows you a couple of different ways — graphs and formulas — to locate your break-even point. Plotting the break-even point In a cost-volume-profit graph, the break-even point is the sales volume where the total sales line intersects with the total costs line. This sales volume is the point at which total sales equals total costs. Suppose that, as with the basketball example earlier in the chapter, a company sells its products for $15 each, with variable costs of $6 per unit and total fixed costs of $300. The graph in Figure 3-6 indicates that the company’s break-even point occurs when the company sells 34 units. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 462 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 3-6: Plotting the break-even point. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. For many products (such as basketballs), you can sell only whole units. Therefore, if you sell whole units, the break-even point must always be a whole number. If break-even analysis results in some fractional volume of sales (such as 33.33333 units), always round up (in this case, to 34 units), even if the fraction is closer to the lower whole number than the higher number. If your break-even point equals 33.0001, round it up to 34. If you round down (to 33 units), then the actual sales volume is below the break-even point, and at this volume level, your company reports a net loss. Using the formula approach When you need to solve actual problems, drawing graphs isn’t always practical. For a quicker approach, you want to rely on the three formulas that use contribution margin to measure net income. (See “Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis” earlier in the chapter.) The break-even point is where net income is zero, so just set net income equal to zero, plug whatever given information you have into one of the equations, and then solve for sales or sales volume. Better yet: At the break-even point, total contribution margin equals fixed costs. Suppose a company has $30,000 in fixed costs. How much total contribution margin does it have to generate in order to break even? Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 463 Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs 0 = Total contribution marginBE – Fixed costs 0 = Total contribution marginBE – $30,000 $30,000 = Total contribution marginBE Here, too, at the break-even point, total contribution margin equals fixed costs of $30,000. Now suppose a company has contribution margin per unit of $6 and fixed costs of $600. What’s the break-even point in units? Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs 0 = (Sales volumeBE × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs 0 = (Sales volumeBE × $6) – $600 $600 = Sales volumeBE × $6 $600 ÷ $6 = 100 units Another company has a contribution margin ratio of 40 percent and fixed costs of $1,000. Sales price is $1 per unit. What’s the break-even point in dollars? Net income = (Sales × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs 0 = (SalesBE × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs 0 = (SalesBE × 0.40) – $1,000 $1,000 = SalesBE × 0.40 $1,000 ÷ 0.40 = SalesBE $2,500 = SalesBE You can express break-even point in units or dollars. If your formula gives you units and you want dollars, multiply the number of units by the sales price. If your formula gives you dollars and you want units, just divide by the sales price. Shooting for Target Profit If you’ve set a specific goal for net income, contribution margin analysis can help you figure out the needed sales. This goal for net income is called target profit. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 464 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions To compute target profit, just adapt one of the three net income formulas. (Head to the earlier section “Preparing a Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis” to see these formulas.) Then plug target profit into one of these formulas as net income. For example, say a company is pushing to earn $20,000 in profit and has to pay $10,000 in fixed costs. How much total contribution margin does the company need to generate in order to make its target profit of $20,000? Net income = Total contribution margin – Fixed costs $20,000 = Total contribution marginTarget – $10,000 $30,000 = Total contribution marginTarget Total contribution margin of $30,000 will result in $20,000 worth of net income. Now suppose a company has set its target profit for $2,000, earns contribution margin per unit of $5, and incurs fixed costs of $500. How many units must the company sell? Net income = (Sales volume × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs $2,000 = (Sales volumeTarget × Contribution margin per unit) – Fixed costs $2,000 = (Sales volumeTarget × $5) – $500 $2,500 = Sales volumeTarget × $5 $2,500 ÷ $5 = Sales volumeTarget 500 units = Sales volumeTarget If the company wants to earn $2,000 in profit, it needs to sell 500 units. Consider another company with a contribution margin ratio of 40 percent and fixed costs of $1,000. The company is looking to earn $600 in net income. How much does that company need in sales? Net income = (Sales × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs $600 = (SalesTarget × Contribution margin ratio) – Fixed costs $600 = (SalesTarget × 0.40) – $1,000 $1,600 = SalesTarget × 0.40 $1,600 ÷ 0.40 = SalesTarget $4,000 = SalesTarget Don’t confuse dollars with units. The formula that uses contribution margin per unit gives you sales in units. However, the formula that uses contribution margin ratio gives you sales in dollars. To translate between these units, just multiply or divide by the sales price as described at the end of the previous section. Also be sure to label the numbers in your analysis, so you don’t confuse terms. For example, use a dollar sign for dollars and the word “units” when dealing with units. Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 465 Observing Margin of Safety Margin of safety is the difference between your actual or expected profitability and the break-even point. It measures how much breathing room you have — how much you can afford to lose in sales before your net income drops to zero. When budgeting, compute the margin of safety as the difference between budgeted sales and the break-even point. Doing so will help you understand the likelihood of incurring a loss. Turn to Book VI, Chapters 4 and 5 for more about budgeting. Using a graph to depict margin of safety Figure 3-7 shows you how to visualize margin of safety with a graph. In this example, margin of safety is the difference between current or projected sales volume of 60 units and break-even sales volume of 34 units, which is 26 units. Sales would have to drop by 26 units for existing net income of $240 to completely dry up. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 3-7: Graphing margin of safety. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Calculating the margin of safety To compute margin of safety directly, without drawing pictures, first calculate the break-even point and then subtract it from actual or projected sales. You can use dollars or units: Margin of safety (in dollars) = SalesActual – SalesBE Margin of safety (in units) = Unit salesActual – Unit salesBE For guidance on finding the break-even point, check out the earlier section “Generating a Break-Even Analysis.” 466 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions You can compute margin of safety either in sales dollars or in units, but be consistent. Don’t subtract break-even sales in units from actual sales in dollars! Taking Advantage of Operating Leverage Operating leverage measures how changes in sales can affect net income. For a company with high operating leverage, a relatively small increase in sales can have a fairly significant impact on net income. Likewise, a relatively small decrease in sales for that same company will have a devastating effect on earnings. Operating leverage is typically driven by a company’s blend of fixed and variable costs. The larger the proportion of fixed costs to variable costs, the greater the operating leverage. For example, airlines are notorious for their high fixed costs. Airlines’ highest costs are typically depreciation, jet fuel, and labor — all costs that are fixed with respect to the number of passengers on each flight. Their most significant variable cost is probably just the cost of the airline food, which, judging from some recent flights couldn’t possibly be very much. Therefore, airlines have ridiculously high operating leverage and unspeakably low variable costs. A small drop in the number of passengermiles can have a dreadful effect on an airline’s profitability. Graphing operating leverage In a cost-volume-profit graph (see Figure 3-3 earlier in the chapter), operating leverage corresponds to the slope of the total costs line. The more horizontal the slope of this line, the greater the operating leverage. Figure 3-8 compares the operating leverage for two different entities, Safe Co., which has lower operating leverage, and Risky Co., which has higher operating leverage. Figure 3-8: How operating leverage increases risk. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 3: Examining Contribution Margin 467 In this example, Risky Co. has higher fixed costs and lower variable costs per unit than Safe Co. Therefore Risky’s total cost line is more horizontal than Safe’s total cost line. Accordingly, Risky has the potential to earn much higher income with the same sales volume than Safe does. Because its fixed costs are so high, Risky also has the potential to incur greater losses than Safe does. Looking at the operating leverage formula The formula for operating leverage is Operating leverage = Total contribution margin ÷ Net income Suppose that Safe Co. and Risky Co. each earn sales of $400 on 50 units. Assume that on these sales, Safe Co. has $150 in contribution margin and Risky has $300 in contribution margin. Safe Co. has fixed costs of $50, while Risky Co. has fixed costs of $200. Safe’s net income comes to $100 ($150 – $50). At this volume level, Risky’s net income also works out to be $100. Here’s the math: Operating leverage = Total contribution margin ÷ Net income Operating leverageSafe Co. = $150 ÷ $100 = 1.5 Operating leverageRisky = $300 ÷ $100 = 3.0 According to these measures, Risky Co. has twice the operating leverage of Safe Co. Although a 10-percent increase in sales boosts Safe Co.’s net income by 15 percent, a similar 10-percent increase in sales for Risky Co. increases that company’s net income by 30 percent! That said, high operating leverage can work against you. For Safe Co., a 10-percent decrease in sales cuts income by 15 percent; for Risky, a 10-percent decrease in sales reduces net income by 30 percent. Because automation replaces labor with machines, it usually replaces the variable costs (from direct labor) with fixed overhead (associated with running equipment). As such, automation tends to increase operating leverage. However, outsourcing usually has the opposite effect. Companies that close factories and pay other companies to make goods for them replace fixed costs (needed to run factories) with variable costs (used to pay other companies to make the goods). Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 468 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Chapter 4 Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis In This Chapter ▶ Understanding and setting standard costs ▶ Figuring out direct materials prices and direct labor rates ▶ Using formulas to compute variances ▶ Exploiting a shortcut for calculating direct material and direct labor variances ▶ Identifying variances that require further investigation W hen things don’t go according to plan, inevitably you’re left asking “Why?” To find the answer, examine the factors under your control. For example, suppose you don’t like to diet. As an accountant, you should enjoy counting calories. But maybe you don’t. Maybe you don’t like to exercise either. That said, if you weigh yourself only to find that you’re gaining rather than losing weight, you may ask “Why?” You thought you were being so careful this week. Why did you gain three pounds? It all comes down to three factors under your control: what you eat and drink, how much you eat and drink, and how much you exercise. Examining each of these factors helps you change your routine so that you can more successfully manage your weight in the future. Variance analysis plays a similar role for business. When things go wrong, or even when they go more right than expected, variance analysis explains why. What caused higher-than-expected profits? What about unexpected losses? You can use all this information to improve future operations. Setting Up Standard Costs You can’t measure variances without first setting standard costs or standards — predetermined unit costs of materials, labor, and overhead. Standards are really the building blocks of budgets; budgets predict total costs (as explained in 470 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Book VI, Chapters 4 and 5), but standards predict the cost of each unit of direct materials, direct labor, and overhead. Standard costs provide a number of important benefits for managers. For example, they ✓ Help managers budget for the future. ✓ Help employees focus on keeping costs down. ✓ Help set sales prices. ✓ Give managers a benchmark for measuring variances and identifying related problems. ✓ Simplify collecting and managing the cost of inventory. ✓ Provide useful information for variance analysis (as explained in this chapter). Implementing standards often forces managers to face a critical dilemma: Should standards be aspirational or realistic? ✓ Ideal or aspirational standards can encourage employees to work hard to achieve rigorous goals. However, overly aggressive standards can unduly pressure employees, causing them to report false information or to just give up on the standards out of frustration, deeming them unattainable. ✓ Realistic standards provide more accurate cost information and are less likely to lead to the kind of unfavorable variances that result in lower-than-expected income. However, realistic standards don’t always encourage employees to “go the extra mile” to improve cost control and productivity. Therefore, the first step in variance analysis is to set up expectations: your standards. These standards must include both the cost and the quantity needed of direct materials and direct labor, as well as the amount of overhead required. After you establish standards, you can use them to compute variances. Whenever actual performance strays from expectations, variances help you identify the reasons why. Establishing direct materials standards Direct materials are raw materials traceable to the manufactured product, such as the amount of flour used to make a cake. To compute the direct materials standard price (SP), consider all the costs that go into a single unit of direct materials. Because several different kinds of direct materials are often necessary for any given product, you need to establish separate direct materials standard prices and quantities for every kind of direct materials needed. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 471 Suppose that the Band Book Company usually pays $10 per pound for paper. It typically pays $0.25 per pound for freight and another $0.10 per pound for receiving and handling. Therefore, as shown in Figure 4-1, total cost per pound equals $10.35. Figure 4-1: Adding up direct materials standard price (SP). ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Another standard to consider is the direct materials standard quantity (SQ) per unit. This number is the amount of direct materials needed to make a single unit of finished product. It includes not only the direct materials actually used but also any direct materials likely to get scrapped or spoiled in the production process. Variance costing involves juggling many different figures and terms. To simplify matters, use abbreviations such as SP (for direct materials standard price) and SQ (for direct materials standard quantity). Doing so makes remembering how to calculate variances easier later in this chapter. For example, assume that Band Book Company needs 25 pounds of paper to make a case of books. For every case, three pounds of paper are deemed unusable because of waste and spoilage. Therefore, the direct materials standard quantity per unit equals 28 pounds, as shown in Figure 4-2. Figure 4-2: Computing direct materials standard quantity (SQ) per unit. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 472 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Determining direct labor standards Direct labor is the cost of paying your employees to make products. Proper planning requires setting standards with respect to two factors: the direct labor standard rate and the direct labor standard hours per unit. To compute the direct labor standard rate or SR (the cost of direct labor), consider all the costs required for a single hour of direct labor. For example, suppose Band Book usually pays employees $9 per hour. Furthermore, it pays an additional $1 per hour for payroll taxes and, on average, $2 per hour for fringe benefits. As shown in Figure 4-3, the direct labor standard rate equals $12 per hour. Figure 4-3: Computing the direct labor standard rate (SR). ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. You also need to estimate the amount of direct labor time needed to make a single unit, the direct labor standard hours (SH) per unit. This measurement estimates how long employees take, on average, to produce a single unit. Include in this rate the time needed for employee breaks, cleanups, and setups. For example, employees at Band Book Company need three hours to produce a single case of books, plus an average of 30 minutes of setup time and 30 minutes of break time. Therefore, the direct materials standard quantity equals four hours, as shown in Figure 4-4. Figure 4-4: Computing direct labor standard hours (SH). ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 473 Calculating the overhead rate Standard costs also need to account for overhead (the miscellaneous costs of running a business) in addition to direct materials and direct labor. Overhead is much more difficult to measure than direct materials or direct labor standards because overhead consists of indirect materials, indirect labor, and other costs not easily traced to units produced. Therefore, measuring how much overhead should be applied to different units produced is very challenging. To assign overhead costs to individual units, you need to compute an overhead allocation rate. Remember that overhead allocation entails three steps: 1. Add up total overhead. Add up estimated indirect materials, indirect labor, and all other product costs not included in direct materials and direct labor. This amount includes both fixed and variable overhead. For example, assume that total overhead for Band Book Company is estimated to cost $100,000. 2. Compute the overhead allocation rate. The allocation rate calculation requires an activity level. You choose an activity that closely relates to the cost incurred. The most common activity levels used are direct labor hours or machine hours. Divide total overhead (calculated in Step 1) by the number of direct labor hours. Assume that Band Book plans to utilize 4,000 direct labor hours: Overhead allocation rate = Total overhead ÷ Total direct labor hours = $100,000 ÷ 4,000 hours = $25.00 Therefore, for every hour of direct labor needed to make books, Band Book applies $25 worth of overhead to the product. 3. Apply overhead. Multiply the overhead allocation rate by the number of direct labor hours needed to make each product. Suppose a department at Band Book actually worked 20 hours on a product. Apply 20 hours × $25 = $500 worth of overhead to this product. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 474 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Adding up standard cost per unit To find the standard cost, you first compute the cost of direct materials, direct labor, and overhead per unit, as explained in the previous sections. Then you add up these amounts. Figure 4-5 applies this approach to Band Book Company. To calculate the standard cost of direct materials, multiply the direct materials standard price of $10.35 by the direct materials standard quantity of 28 pounds per unit. The result is a direct materials standard cost of $289.80 per case. To compute direct labor standard cost per unit, multiply the direct labor standard rate of $12 per unit by the direct labor standard hours per unit of 4 hours. The standard cost per unit is $48 for direct labor. Now multiply the overhead allocation rate of $10 per hour by the direct labor standard hours of 4 hours per unit to come to a standard cost of overhead per unit of $40. Figure 4-5: Summing up standard cost per unit. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Add together direct materials, direct labor, and overhead to arrive at the standard cost per unit of $289.80 + $48 + $40 = $377.80. Making a single case of books costs Band Book $377.80. Understanding Variances A variance is the difference between the actual cost and the standard cost that you expected to pay. (Standard costs are covered earlier in this chapter.) When actual cost exceeds the standard, then the resulting variance is considered unfavorable because it reduces net income. On the other hand, when actual costs come in under standard costs, then the resulting variance is considered favorable because it increases net income. Variances can arise from direct materials, direct labor, and overhead. In fact, the variances arising from each of these three areas, when added together, should equal the total variance: Total variance = D irect materials variance + Direct labor variance + Overhead variance Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 475 In turn, you can further break down direct materials and direct labor variances into additional price and quantity variances to understand how changes in materials prices, materials quantities used, direct labor rates, and direct labor hours affect overall profitability. Generally, you incur a variance for one of two reasons: Either you used more or less than you planned (a quantity variance), or you paid more or less than you planned (a price or rate variance). Computing direct materials variances A direct materials variance results from one of two conditions: differences in the prices paid for materials or discrepancies in the quantities used in production. To find these variances, you can use formulas or a simple diagram approach. Using formulas to calculate direct materials variances The total direct materials variance is comprised of two components: the direct materials price variance and the direct materials quantity variance. To compute the direct materials price variance, take the difference between the standard price (SP) and the actual price (AP), and then multiply that result by the actual quantity (AQ): Direct materials price variance = (SP – AP) × AQ To get the direct materials quantity variance, multiply the standard price by the difference between the standard quantity (SQ) and the actual quantity: Direct materials quantity variance = SP × (SQ – AQ) The total direct materials variance equals the difference between total actual cost of materials (AP × AQ) and the budgeted cost of materials, based on standard costs (SP × SQ): Total direct materials variance = (SP × SQ) – (AP × AQ) Consider the Band Book Company example described in “Setting Up Standard Costs” earlier in the chapter. Band Book’s standard price is $10.35 per pound. The standard quantity per unit is 28 pounds of paper Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 476 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions per case. This year, Band Book made 1,000 cases of books, so the company should have used 28,000 pounds of paper, the total standard quantity (1,000 cases × 28 pounds per case). However, the company purchased 30,000 pounds of paper (the actual quantity), paying $9.90 per case (the actual price). Based on the given formula, the direct materials price variance comes to a positive $13,500, a favorable variance: Direct materials price variance = (SP – AP) × AQ = ($10.35 – $9.90) × 30,000 = $13,500 favorable This variance means that savings in direct materials prices cut the company’s costs by $13,500. The direct materials quantity variance focuses on the difference between the standard quantity and the actual quantity, arriving at a negative $20,700, an unfavorable variance: Direct materials quantity variance = SP × (SQ – AQ) = $10.35 × (28,000 – 30,000) = –$20,700 unfavorable This result means that the 2,000 additional pounds of paper used by the company increased total costs $20,700. Now, you can plug both parts in to find the total direct materials variance. (You could just plug in the final results, but I show you the longer math here.) Compute the total direct materials variance as follows: Total direct materials variance = (SP × SQ) – (AP × AQ) = ($10.35 × 28,000) – ($9.90 × 30,000) = $289,800 – $297,000 = –7,200 unfavorable Diagramming direct materials variances Figure 4-6 provides an easier way to compute price and quantity variances. To use this diagram approach, just compute the totals in the third row: actual cost, actual quantity at standard price, and the standard cost. The actual cost less the actual quantity at standard price equals the direct materials price variance. The difference between the actual quantity at standard price and the standard cost is the direct materials quantity variance. The total of both variances equals the total direct materials variance. To apply this method to the Band Book example, take a look at Figure 4-7. Start at the bottom. Direct materials actually cost $297,000, even though the standard cost of the direct materials is only $289,800. The actual quantity of direct materials at standard price equals $310,500. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 477 Figure 4-6: Diagram of how price and quantity variances contribute to direct materials variance. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. To compute the direct materials price variance, subtract the actual cost of direct materials ($297,000) from the actual quantity of direct materials at standard price ($310,500). This difference comes to a $13,500 favorable variance, meaning that the company saves $13,500 by buying direct materials for $9.90 rather than the original standard price of $10.35. To compute the direct materials quantity variance, subtract the actual quantity of direct materials at standard price ($310,500) from the standard cost of direct materials ($289,800), resulting in an unfavorable direct materials quantity variance of $20,700. Because the company uses 30,000 pounds of paper rather than the 28,000-pound standard, it loses an additional $20,700. This setup explains the unfavorable total direct materials variance of $7,200 — the company gains $13,500 by paying less for direct materials, but loses $20,700 by using more direct materials. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 478 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 4-7: Computing direct materials variances by using a diagram. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Calculating direct labor variances A direct labor variance is caused by differences in either wage rates or hours worked. As with direct materials variances, you can use either formulas or a diagram to compute direct labor variances. Utilizing formulas to figure out direct labor variances To estimate how the combination of wages and hours affects total costs, compute the total direct labor variance. As with direct materials, the price and quantity variances add up to the total direct labor variance. To compute the direct labor price variance (also known as the direct labor rate variance), take the difference between the standard rate (SR) and the actual rate (AR), and then multiply the result by the actual hours worked (AH): Direct labor price variance = (SR – AR) × AH To get the direct labor quantity variance (also known as the direct labor efficiency variance), multiply the standard rate (SR) by the difference between total standard hours (SH) and the actual hours worked (AH): Direct labor quantity variance = SR × (SH – AH) Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 479 The direct labor variance equals the difference between the total budgeted cost of labor (SR × SH) and the actual cost of labor, based on actual hours worked (AR × AH): Total direct labor variance = (SR × SH) – (AR × AH) Now you can plug in the numbers for the Band Book Company example from earlier in the chapter. Band Book’s direct labor standard rate (SR) is $12 per hour. The standard hours (SH) come to 4 hours per case. Because Band made 1,000 cases of books this year, employees should have worked 4,000 hours (1,000 cases × 4 hours per case). However, employees actually worked 3,600 hours, for which they were paid an average of $13 per hour. With these numbers in hand, you can apply the formula to compute the direct labor price variance: Direct labor price variance = (SR – AR) × AH = ($12.00 – $13.00) × 3,600 = –$1.00 × 3,600 = –$3,600 unfavorable According to the direct labor price variance, the increase in average wages from $12 to $13 causes costs to increase by $3,600. Now plug the numbers into the formula for the direct labor quantity variance: Direct labor quantity variance = SR × (SH – AH) = $12.00 × (4,000 – 3,600) = $12.00 × 400 = $4,800 favorable Employees worked fewer hours than expected to produce the same amount of output. This change saves the company $4,800 — a favorable variance. To compute the total direct labor variance, use the following formula: Total direct labor variance = (SR × SH) – (AR × AH) = ($12.00 × 4,000) – ($13.00 × 3,600) = $48,000 – $46,800 = $1,200 favorable According to the total direct labor variance, direct labor costs were $1,200 lower than expected, a favorable variance. Employing diagrams to work out direct labor variances Figure 4-8 shows you how to use a diagram to compute price and quantity variances quickly and easily. First, compute the totals in the third row: actual cost, actual hours at standard rate, and the standard cost. To get the direct labor price variance, subtract the actual cost from the actual hours at standard. The difference between the standard cost of direct labor and the actual hours of direct labor at standard rate equals the direct labor quantity variance. The total of both variances equals the total direct labor variance. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 480 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 4-8: How price and quantity variances add up to direct labor variance. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Take a look at Figure 4-9 to see this diagram in action for Band Book: Starting from the bottom, the actual cost of direct labor amounts to $46,800. The actual hours of direct labor at standard rate equals $43,200. The standard cost of direct labors comes to $48,000. To compute the direct labor price variance, subtract the actual hours of direct labor at standard rate ($43,200) from the actual cost of direct labor ($46,800) to get a $3,600 unfavorable variance. This result means the company incurs an additional $3,600 in expense by paying its employees an average of $13 per hour rather than $12. To compute the direct labor quantity variance, subtract the standard cost of direct labor ($48,000) from the actual hours of direct labor at standard rate ($43,200). This math results in a favorable variance of $4,800, indicating that the company saves $4,800 in expenses because its employees work 400 fewer hours than expected. The $1,200 favorable variance arises because of two factors: the company saves $4,800 from fewer hours worked but incurs an additional $3,600 expense by paying its employees more money per hour than planned. This scenario begs the question “Are higher-paid workers more productive?” But that’s a discussion for the human resources experts. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 481 Figure 4-9: Computing the direct labor variances the easy way with a diagram. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Computing overhead variances Whenever you see direct labor and direct materials, overhead can’t be far behind. To compute overhead applied, multiply the overhead application rate by the standard number of hours allowed: Overhead applied = Overhead application rate × SH So you can determine overhead variance by subtracting actual overhead from applied overhead: Overhead variance = Overhead applied – Actual overhead Band Book Company incurs actual overhead costs of $95,000. The company’s overhead application rate is $25 per hour. (You can find the math for that calculation in the earlier section “Calculating the overhead rate.”) In that prior section, you use direct labor hours as the activity level for applying overhead. In order for Band Book’s workers to produce 1,000 cases, you can expect them to work standard hours of 4 direct labor hours per case. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 482 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions SH equals 1,000 cases produced × 4 direct labor hours per case, or 4,000 direct labor hours. This amount results in overhead applied of $100,000: Overhead applied = Overhead application rate × SH = $25.00 × 4,000 = $100,000 To compute the variance, subtract actual overhead from the overhead applied: Overhead variance = Overhead applied – Actual overhead = $100,000 – $95,000 = $5,000 Because actual overhead is less than overhead applied, the $5,000 variance is favorable. Spending too much or too little on overhead — or using overhead inefficiently — often causes overhead variance. Like direct labor and direct materials, overhead, too, can have price and quantity variables. However, fixed and variable cost behaviors considerably complicate the calculation of overhead variances. These complexities are outside the scope of this book. Looking past the favorable/ unfavorable label The unfavorable and favorable labels describe variances only in terms of how they affect income; favorable variances aren’t necessarily always good, and unfavorable variances aren’t necessarily always bad. For example, a favorable variance may result because a company purchases cheaper direct materials of poorer quality. These materials lower costs, but they also hurt the quality of finished goods, damaging the company’s reputation with customers. This kind of favorable variance can work against a company. On the other hand, an unfavorable variance may occur because a department chooses to scrap poor-quality goods. In the long run, the company benefits from incurring a short-term unfavorable variance to provide better-quality goods to its customers. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 483 Teasing Out Variances In your business, variance analysis helps you identify problem areas that require attention, such as ✓ Poor productivity ✓ Poor quality ✓ Excessive costs ✓ Excessive spoilage or waste of materials Identifying and working on these problems helps managers improve production flow and profitability. Managers and accountants often talk about management by exception — using variance analysis to identify exceptions, or problems, where actual results significantly vary from standards. By paying careful attention to these exceptions, managers can root out and rectify manufacturing problems and inefficiencies, thereby improving productivity, efficiency, and quality. Interpreting variances in action Book VII The previous sections in this chapter lay out what happens to the costs of the Band Book Company over the course of a year. Figure 4-10 summarizes Band Book’s variances. Figure 4-10: Band Book’s variances. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Making Savvy Business Decisions 484 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions A complete analysis of Band Book’s variances provides an interesting story to explain why the company has a $1,000 unfavorable variance. The following events transpire: ✓ The company pays less than expected for direct materials, leading to a favorable $13,500 direct materials price variance. ✓ Perhaps because of the cheaper, lower-quality direct materials, the company uses an excessive amount of direct materials. This overage results in a $20,700 unfavorable direct materials quantity variance. ✓ The company pays its employees a higher wage rate, resulting in an unfavorable direct labor price variance of $3,600. ✓ The company saves money because employees work fewer hours than expected, perhaps because they’re more productive, higher-paid workers. The favorable direct labor quantity variance is $4,800. ✓ The company saves $5,000 in reduced overhead costs. Focusing on the big numbers Management by exception directs managers to closely investigate the largest variances. For example, the two largest variances in Figure 4-10 are the direct materials quantity variance ($20,700 unfavorable) and the direct materials price variance ($13,500 favorable). Band Book’s managers should focus on how the company buys and uses its direct materials. Here, the direct materials quantity variance resulted because the company should have used 28,000 pounds of paper but actually used 30,000 pounds of paper. Why? Here are a few possibilities: ✓ The paper was poor quality, and much of it needed to be scrapped. ✓ The company underestimated the amount of paper needed (the standard quantity needs to be changed). ✓ Someone miscounted the amount of paper used; 2,000 pounds of paper are sitting in the back of the warehouse (oops). ✓ A new employee misused the machine, shredding several thousand pounds of paper. Management by exception directs managers to where the problem may have occurred so that they can investigate what happened and take corrective action. Chapter 4: Accounting for Change with Variance Analysis 485 Now take a look at the favorable direct materials price variance of $13,500. How did the purchasing department come to purchase direct materials for only $9.90 a pound, rather than the $10.35 standard? Did the purchased materials meet all of the company’s quality standards? Should the company reduce its standard price in the future? Consider setting control limits to determine which items are sufficiently large to investigate. A variance exceeding its control limit takes priority over less significant variances. Tracing little numbers back to big problems Be careful! Don’t focus exclusively on the big numbers and ignore the little numbers. Big problems can also hide in the small numbers. For example, although many frauds (such as stealing raw materials) may trigger large variances, a well-planned fraud may be designed to manipulate variances so that they stay low, below the radar, where managers won’t notice them. For example, knowing the standard price of a raw material is $100 per unit, a crooked purchasing manager may arrange to purchase the units for exactly that price — $100 per unit — while receiving $10 per unit as a kick-back gratuity from the supplier. This scheme results in a direct materials price variance of zero, but it doesn’t reflect what should be the company’s actual cost of doing business. A more scrupulous purchasing manager would have arranged a purchase price of $90, resulting in a large positive direct materials price variance. To avoid these problems, managers should still investigate all variances, even while focusing most of their time on the largest figures. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 486 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Chapter 5 Making Smart Pricing Decisions In This Chapter ▶ Understanding the importance of product differentiation ▶ Addressing absorption costing ▶ Using cost-plus pricing ▶ Taking risks with variable-cost pricing ▶ Aiming for target costing H ave you ever seen the game show The Price Is Right? The host challenges contestants to guess the prices of different merchandise. Guessing the right price can win you cash and all sorts of valuable prizes. Even if you get the price wrong, you still walk away with your novelty ­nametag and maybe a chance to spin a giant wheel. The stakes get a lot higher when you’re naming prices in the real business world. Prices that are too high scare away customers. Too low, and losses may wipe out your business. Prices must be low enough to lure customers but high enough to cover your costs and help you earn a profit. Therefore, before setting a price, you must understand both market forces and the cost structure of your business. This chapter explains how to use your knowledge of cost behavior to make savvy pricing decisions. Differentiating Products Product differentiation allows consumers to see differences among different companies’ products, which makes them willing to spend more money for some brands than for others. Hence, a company that successfully differentiates its products can charge a higher price than its competitors, making it a price maker. Companies that don’t differentiate their products need to use low prices to get a leg up on the competition. Marketers call these companies price takers. 488 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Customers usually have trouble seeing any difference among the products offered by different mainstream supermarkets. Therefore, all supermarkets — price takers — need to price their products competitively in line with each other. On the other hand, premium supermarkets such as Whole Foods have done a brilliant job of differentiating themselves from competitors, so much so that customers often pay significantly more money to shop there. Whole Foods is a price maker. Regardless of how well a company differentiates its products, its prices must take into account both market forces and the company’s own cost behavior. Taking All Costs into Account with Absorption Costing Absorption costing (sometimes also called full costing) is the predominant method for costing goods that companies manufacture and sell. Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) require all U.S. companies to use absorption costing in their financial statements. International accounting standards have similar requirements worldwide. Absorption costs include all product costs — the costs of making products. Product costs include a variable component that increases and decreases with volume and a fixed component that doesn’t change regardless of how much or how little you produce. The costs of direct materials, raw materials that you can directly trace to the manufactured product, are variable. After all, the more units you make, the more direct materials you need to make them. The same goes for direct labor, the cost of paying employees to make your products. Overhead costs, such as the miscellaneous costs of running a factory, usually consist of a mixture of fixed and variable costs. Absorption costing requires you to spread out the fixed costs over all units produced. (Flip to Chapter 4 for details on direct and overhead costs.) Suppose your factory makes T-shirts. Each T-shirt requires $8 worth of variable costs (direct materials, direct labor, and variable overhead), and your factory pays $100,000 for fixed costs each year for rent and utilities. This year, you plan to make 50,000 T-shirts. How much will each T-shirt cost? According to absorption costing, the cost of a T-shirt includes both variable and fixed components. You know that the variable component per shirt is $8. Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions 489 The fixed component of $100,000 applies to all the shirts, however, so you need to spread it out among them. Divide the total fixed costs of $100,000 by the number of units you plan to produce (50,000) to get a fixed cost per unit of $2. Therefore, each T-shirt includes $8 worth of variable costs and $2 worth of fixed costs, resulting in total cost per unit of $10. Pricing at Cost-Plus Many retailers and manufacturers set their prices at cost-plus by adding a fixed markup to their absorption cost. Cost-plus pricing ensures that prices are high enough to meet profit goals. Figure 5-1 illustrates how cost-plus pricing computes the sales price by adding markup to a product’s fixed and variable costs. Book VII Figure 5-1: Cost-plus pricing includes absorption cost of the product plus a markup. Making Savvy Business Decisions ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Computing fixed markups To figure out the markup for cost-plus pricing, divide total desired profit by the number of units produced. For example, suppose that Saint Company wants to earn $100,000 on the production of 100 Model 51 Robots: Desired profit ÷ Units produced = Markup = $100,000 ÷ 100 = $1,000 490 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Dividing the desired profit by units produced results in a planned markup of $1,000 per unit. To set the price, add this planned markup to the cost. Assume that Saint’s cost to produce each robot is $4,000: Cost + Markup = Sales price = $4,000 + $1,000 = $5,000 If Saint Company wants to earn a total of $100,000, it should set the price at $5,000 per unit. Setting a cost-plus percentage Because companies often sell many different products at different prices, they commonly use a cost-plus percentage or percentage markup on cost that applies to all their products. To figure this percentage, you divide the markup, in dollars, by the total product cost. Then, to determine the products’ sales prices, you apply this percentage to all products, or to different categories of products. For example, Saint Company’s Model 51 Robot has a $1,000 markup on a cost of $5,000. Markup ÷ Product cost = $1,000 ÷ $4,000 = 0.25 or 25% Here, Saint earns a 25-percent cost-plus percentage. The company can then apply the same cost-plus percentage to set the prices of other products. For example, another robot, Model 6, costs Saint Company $6,000 to produce. The markup on this robot amounts to $6,000 × 0.25 percent = $1,500, pricing it at $6,000 + $1,500 = $7,500. Considering problems with cost-plus pricing Cost-plus pricing works because it’s easy to use. However, it carries a few drawbacks. First, it ignores market factors. Just because you like to mark up your merchandise 20 percent doesn’t necessarily mean your customers are willing to pay this price or that your competitors will cooperate with you by setting their prices even higher. Second, because cost-plus pricing relies on absorption costing, it treats fixed costs as though they were variable. Saint Company wants to sell 100 Model 51 Robots, which means it can distribute its fixed costs over 100 units. Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions 491 However, the fixed costs remain the same regardless of how many units Saint actually sells; if the company sells only 50 robots, the fixed costs are spread over fewer units (50 robots rather than 100), and the cost per unit rises. Check out Figure 5-2. If production drops to 50 robots, then the cost per unit increases to $6,000 per unit. This change puts Saint into a tight bind. Figure 5-2 shows how this miscalculation causes Saint’s profits to vaporize into a $50,000 loss. Figure 5-2: Cost-plus pricing gone wild. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Look on the bright side: If your sales volume is higher than you expected, then spreading fixed costs will have a disproportionately positive effect on income — delivering profits way beyond your wildest dreams. That’s because you’ll spread the fixed costs over more units, which lowers the total cost per unit sold. Extreme Accounting: Trying Variable-Cost Pricing Variable-cost pricing offers an adventurous variation on cost-plus pricing (refer to the earlier section “Pricing at Cost-Plus”). Instead of adding a markup on total cost, variable-cost pricing adds a markup on just the variable cost. It disregards fixed costs altogether. Figure 5-3 compares variable-cost pricing with boring old cost-plus pricing. The following sections show you how variable-cost pricing works and point out the drawbacks of using this system. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 492 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Figure 5-3: Comparing cost-plus (a) and variablecost pricing (b). ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Working out variable-cost pricing When you use variable-cost pricing, your markup must cover both the desired profit and the expected fixed costs. Therefore, to figure out your markup, divide the total desired profit plus expected fixed costs by the number of units produced. Suppose that Sparl Industries makes the Red Rover model. The entire production run of Red Rover requires $900,000 worth of fixed costs. Each unit costs another $90,000 in variable costs. Sparl wants to earn $400,000 in profit on the production and sale of 20 units of this model. First, figure out how much markup you need on each unit to cover both the desired profit and the fixed costs: (Desired profit + Fixed costs) ÷ Units produced = Markup = ($400,000 + $900,000) ÷ 20 = ($1,300,000) ÷ 20 = $65,000 The markup is $65,000 per unit. Now set the price at this planned markup plus the variable cost: Variable cost + Markup = $90,000 + $65,000 = $155,000 According to this analysis, if Sparl Industries wants to earn $400,000 in profit and cover $900,000 worth of fixed costs by selling 20 units, it should set the sales price at $155,000. Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions 493 Spotting the hazards of variable-cost pricing Variable-cost pricing is especially useful for companies pricing special orders when they have excess capacity, meaning they have sufficient resources to produce more goods. However, when operating at full capacity, variable-cost pricing may be hazardous to the health of your business. Suppose that you operate a hotel with vacant rooms. Each room has a variable cost of $10/night, and a fixed cost of $90/night. Cost-plus pricing requires you to base your price on a total cost of $100/night. However, variable-cost pricing allows you to base your price on a variable cost of just $10/night. If your hotel has vacancies (read: excess capacity) and a customer walks in without a reservation, offering to pay $52 for a room for the night, variable-cost pricing indicates you should take the guy in. After all, $52 exceeds the variable cost of $10, increasing your profits by $42. (Cost-plus pricing tells you to refuse the offer. Each room costs $100/night. Why would you willingly lose $48?) But if your hotel is completely booked, the only way to house the $52 customer would be to turn away a full-price-paying customer, reducing revenue. Variable-cost pricing poses another severe danger: To earn a profit, your sales must exceed costs. Because variable-cost pricing doesn’t fully account for fixed costs, it can trick managers into setting prices so low that they hurt profits, or worse yet, cause net losses. As explained in the preceding example, occasionally selling a room for $52 may increase your profits. However, selling too many rooms at such low prices (even if you’re never at full capacity) causes you to lose a lot of money. Bull’s-Eye: Hitting Your Target Cost Many industries use price points — special “magic” price levels that customers expect to pay. You’ve probably seen these prices in the store: $99.99, $26.99, $19.95, and so on. Understanding customer expectations and competitor ­pricing, manufacturers design products specifically so that the products can be produced and sold at the magic price points. Although traditionally you first design the product and then set the price, target costing requires you to set the price before you design the product. After you know the price, you can engineer the product so that its cost is Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 494 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions low enough to ensure that you earn the expected profit margin. Done right, target costing avoids problems caused by products that are priced too high for consumers or are too expensive to make. It engineers the price, the profit margin, and the cost right into the product. Calculating your target cost With target costing, the company starts with market price and markup and uses that information to figure out the product’s cost and specifications. (In contrast, cost-plus pricing starts with the product cost and desired profit and uses that information to set the price. You can read about cost-plus pricing earlier in the chapter.) To figure out the target cost, subtract the desired profit from the market price: Market price – Desired profit = Target cost Figure 5-4 illustrates how this process works. Figure 5-4: In target costing, the market price determines the product’s cost. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. For example, suppose you head to a big-box store to buy a new desktop computer, and you’re determined to pay no more than $750 plus tax. You discover four different desktop models, priced at $599.99, $749.99, $999.99, and $1,299.99. You take the $749.99 model, because you want the best computer you can get for $750 or less. Assume that the store sets prices so that gross profit equals 10.51 percent of the company’s sales price. An inventory item that sells for $100 typically includes gross profit worth $100 × 0.1051 = $10.51, costing the company $100.00 – $10.51 = $89.49. Gross profit is defined as sales less cost of sales. Check out Chapter 3 for more detail. Chapter 5: Making Smart Pricing Decisions 495 The company’s desired profit on your computer model equals $749.99 × 0.1051 = $78.82. Plug it into the formula: Market price – Desired profit = $749.99 – $78.82 = $671.17 The math indicates that the store should pay $671.17 for computers that it can sell for $749.99. Target costing works both for retailers (like that big-box store) and for manufacturers (such as the maker of your new computer). Therefore, after the store determines that it’s willing to pay $671.17 for these computers, the maker needs to figure out how to make computers with all the right bells and whistles that it can sell for $671.17. The computer maker works to earn a 22.7-percent profit margin on sales. Therefore, the company’s desired profit equals $671.17 × 22.7 percent = $152.36: Market price – Desired profit = $671.17 – $152.36 = $518.81 After subtracting desired profit of $152.36 from its expected sales price of $671.17, the computer maker works out that it needs to engineer and produce computers that cost $518.81. Armed with this knowledge, the engineers pick and choose various specifications and features to cook up a computer that costs exactly this amount. Knowing when to use target costing Target costing works especially well for companies whose products aren’t well differentiated (such as electronic accessories and economy automobiles), where price is often a key consideration for customers selecting which brand to buy. This technique ensures that the company can sell a competitive product with all the features — and the price — that customers expect. Book VII Making Savvy Business Decisions 496 Book VII: Making Savvy Business Decisions Book VIII Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Don’t overlook opportunity costs — the cost of missed opportunities when you allocate money to certain business ventures. To find out more about opportunity costs and how to account for them, visit www.dummies.com/extras/accountingaio. In this book… ✓ Tell the difference between costs and expenses, figure out which costs you can depreciate, and know when to recognize revenue. ✓ Take a look at how inventory calculations impact cash flow and other financial statements. Inventory is often your largest asset account balance, so understanding these issues is crucial. ✓ Determine when something you’re thinking of purchasing is likely to pay for itself. Consider the cash inflows that the new purchase helps you generate and calculate your break-even point. ✓ Grasp the pros and cons of taking on debt to leverage equity. Weigh the cost of interest on a loan with a potential dividend that you would pay a shareholder. Chapter 1 Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue In This Chapter ▶ Knowing the ins and outs of costs and expenses ▶ Understanding the difference between product and period costs ▶ Figuring out which costs to depreciate ▶ Mulling over revenue recognition T his chapter is your introduction to a company’s tangible assets, which you can touch and feel — they have a physical presence. Tangible assets, also called fixed assets, include property, plant, and equipment (PP&E). Many fixed assets are used for years, and a company relies on a mysterious accounting tool called depreciation to keep its financial statements in line with the reality of how long those assets stay in use. If you read this entire chapter, depreciation won’t seem so mysterious anymore. This chapter helps you understand what depreciation is and how it connects a business’s costs to its expenses. (Yes, costs and expenses are two different things in the business world.) This chapter also walks you through the information you find in a schedule of depreciation. Because you match expenses with revenue, this chapter wraps up with a discussion of revenue recognition — the event or transaction that determines when revenue is posted to your accounting records. 500 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Defining Costs and Expenses in the Business World In the world of business, costs aren’t the same as expenses. Note this ­process: ✓ When a business incurs a cost, it exchanges a resource (usually cash or a promise to pay cash in the future) to purchase a good or service that enables the company to generate revenue. ✓ Later, when the asset is used to create a product or service, the cost of the asset is converted into an expense. ✓ When the product or service is sold, the company generates revenue. The revenue is matched with the expenses incurred to generate the revenue. Businesses use this matching principle to calculate the profit or loss on the transaction. Here’s an example of a common business transaction that demonstrates the process: Suppose you’re the manager of the women’s apparel department of a major manufacturer. You’re expanding the department to add a new line of formal garments. You need to purchase five new sewing machines, which for this type of business are fixed assets. When you buy the sewing machines, the price you pay (or promise to pay) is a cost. Then, as you use the sewing machines in the normal activity of your business, you depreciate them: You reclassify the cost of buying the asset to an expense. So the resources you use to purchase the sewing machines move from the balance sheet (cost) to the income statement (expense). Your income statement shows revenue and expenses. The difference between those two numbers is the company’s net income (when revenue is more than expense) or net loss (when expenses are higher than revenue). Still wondering what the big deal is with accountants having to depreciate fixed assets? Well, the process ties back to the matching principle, discussed in the next section. Satisfying the Matching Principle In accounting, every transaction you work with has to satisfy the matching ­principle (see Book I, Chapter 4). You have to associate all revenue earned during the accounting period to all expenses you incur to produce that ­revenue. Chapter 1: Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue 501 The idea is that the expenses are matched with the revenue — r­ egardless of when the expense occurs. Continuing with the sewing machine example from the previous section, s­ uppose the life of the sewing machine — the average amount of time the company knows it can use the sewing machine before having to replace it — is five years. The average cost of a commercial sewing machine is $1,500. If the company expenses the entire purchase price (cost) of $1,500 in the year of purchase, the net income for year one is understated and the net income for the next four years is overstated. Why? Because although the company laid out $1,500 in year one for a machine, the company anticipates using the machine for another four years. So to truly match the sales the company generates from garments made by using the sewing machine, the cost of the machine has to be allocated over each of the years it will be used to crank out those garments for sale. Identifying Product and Period Costs The way a company classifies a cost depends on the category the cost falls into. Using generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) as explained in Book IV, Chapter 1, business costs fall into the two general categories in the following list: ✓ Product costs: Any costs that relate to manufacturing or merchandising an item for sale to customers. A common example is inventory (see Chapter 2), which reflects costs a manufacturing company incurs when buying the raw materials it needs to make a product. For a merchandiser (retailer), the cost of inventory is what it pays to buy the finished goods from the manufacturer. ✓ Period costs: Costs that, although necessary to keep the business’s doors open, don’t tie back to any specific item the company sells. You can also think of period costs as costs you incur due to the passage of time, such as depreciation, rent, interest on a loan, and insurance ­premiums. Discovering Which Costs Are Depreciated When a company purchases a fixed asset (see Book IV, Chapter 3), such as a computer or machine, the cost of the asset is spread over its useful life, which may be years after the purchase. Therefore, depreciation is a period cost: As time passes, the fixed asset is used to generate revenue. The cost of the fixed asset is converted into an expense. Book VIII Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions 502 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Your next question may be: “Which costs associated with purchasing a fixed asset do you add together when figuring up the entire cost? Just the purchase price? Purchase price plus tax and shipping? Other costs?” Except for the allocation of cost between land and buildings (see the section, “Allocating costs between land and buildings”), figuring depreciated cost is straightforward. Per GAAP, the business has to record all fixed asset purchases on its balance sheet at their original cost plus all the ordinary and necessary costs to get the fixed asset ready to use. The total cost of the fixed asset is referred to as its depreciable base. For example, a company makes pencils and buys a new machine to automatically separate and shrink-wrap ten pencils into salable units. Various costs of the machine may include the purchase price, sales tax, freight-in, and assembly of the shrink-wrapping machine on the factory floor. (Freight-in is the buyer’s cost to get the machine from the seller to the buyer.) Handling real property depreciation Now, what about real property — land and buildings? Both are clearly fixed assets, but the cost of the land a building sits on isn’t depreciated and has to be separated from the cost of the building. Your financial statements will list land and building as two separate line items on the balance sheet. Why? The answer is that GAAP mandates that separation — no ifs, ands, or buts about it. The cost of land is never depreciated either under GAAP or on the company’s tax return. That’s because the land a building stands on is assumed to retain its value. In other words, it won’t be used up or run down through use over time. So, if a company pays $250,000 to purchase a building to manufacture its pencils and the purchase price is allocated 90 percent to building and 10 percent to land, how much of the purchase price is spread out over the useful life of the building? Your answer is: $250,000 × 0.90 = $225,000. Allocating costs between land and buildings Frequently, a company pays one price for both a building and the land that the building sits on. Figuring out the allocation of costs between land and building is a common challenge. The best approach is to have an appraisal done during the purchasing process. Chapter 1: Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue 503 An appraisal occurs when a licensed professional determines the value of real property. If you’ve ever purchased a home and applied for a mortgage, you’re probably familiar with property appraisals. Basically, the appraisal provides assurance to the mortgage company that you’re not borrowing more than the property is worth. Even if a business doesn’t have to secure a mortgage to purchase a real property asset, it still gets an appraisal to make sure it’s not overpaying for the property. Alternatively, the county property tax records may show an allocation of costs to land. However, that allocation is just for property tax purposes; it may not be materially correct for depreciation purposes. Just remember to subtract land cost from the total before calculating real property depreciation (depreciation on just the building). Land improvements, such as fences, roads, and gates, are depreciable. Land improvements should be shown as a separate line item on the balance sheet (see Book IV, Chapter 3). If a business purchases a piece of raw land and constructs its own building, the accounting issue is more straightforward, because you have a sales price for the land and construction costs for the building. Expensing repairs and maintenance Preventative repair and maintenance costs are expensed in the period in which they’re incurred. For example, on June 14, a florist business has the oil changed and purchases new tires for the flower delivery van. The cost of the oil change and tires goes on the income statement as an operating expense for the month of June. The next month, the delivery van’s transmission goes completely out, stranding the driver and flowers at the side of the road. Rebuilding the transmission significantly increases the useful life of the delivery van, so you have to add the cost of the new transmission to the net book value of the van on the balance sheet. Net book value (or book value for short) is the difference between the cost of the fixed asset and its accumulated depreciation at any given time. Preparing a Depreciation Schedule Book III, Chapter 1 explains the different methods a business can use to calculate depreciation and how the methods compare to each other. A company may use different depreciation methods for different types of assets. Book VIII Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions 504 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions All businesses keep a depreciation schedule for their assets showing all the relevant details about each asset. Here is the basic information that shows up on a depreciation schedule: ✓ Description: The type of asset and any other identifying information about the fixed asset. For a truck, the description may include the make and model of the truck and its license plate number. ✓ Cost: The purchase price of the asset plus any other spending that should be added to the asset’s cost. See “Discovering Which Costs Are Depreciated,” earlier in this chapter for an explanation of other costs that are included with the purchase price. Although most additions to purchase price take place when the company acquires the asset, the fixed asset cost can be added to after the fact if material renovations are performed. (Think about the truck transmission example from the earlier section “Expensing repairs and maintenance.”) ✓ Life: How long the company estimates it will use the fixed asset. ✓ Method: The method of depreciation the company uses for the fixed asset. ✓ Salvage value: The estimated value of the fixed asset when the company gets rid of or replaces it. ✓ Date purchased: The day the asset was purchased. ✓ Current depreciation: The depreciation expense booked in the current period. ✓ Accumulated depreciation: The total amount of depreciation expensed from the day the company placed the fixed asset in service to the date of the financial report. ✓ Net book value: The difference between the fixed asset cost and its accumulated depreciation. Depending on the size of the company, the depreciation schedule may also have the fixed asset’s identifying number, the location where the fixed asset is kept, property tax information, and many more facts about the asset. In order to audit fixed assets, auditors may perform a physical count of the assets. (See Book IX for more about auditing.) If you store tools and equipment in a warehouse, for example, the auditors want to verify that each asset on your fixed asset listing (accounting records) is actually located in the warehouse. Assigning each asset a unique number is important, so that the number on the fixed asset listing can be matched to the same number on the asset itself. That policy allows the audit process to go smoothly. Chapter 1: Identifying Costs and Matching Costs with Revenue 505 Having a nicely organized depreciation schedule allows the company to keep at its fingertips a summary of activity for each fixed asset. Check out Figure 1-1 to see the basic organization for a depreciation schedule. Figure 1-1: Example of a depreciation schedule. ©John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Deciding When to Recognize Revenue The matching principle requires that you match costs incurred with the revenue a company generates. Previously in this chapter, you explore the costs side of the matching principle. You wrap up this chapter by considering the revenue side of the matching principle. Going over the revenue recognition principle The revenue recognition principle, first mentioned in Book I, Chapter 4, requires that, if you use the accrual basis of accounting, you recognize ­revenue by using these two criteria: ✓ Revenue is recorded when it has been earned ✓ Revenue is considered earned when the revenue generation process is substantially complete Generally, the revenue generation process is complete when you deliver your product or service. So, when the clothing store receives jeans from the manufacturer, the company that produced the jeans should recognize revenue. If you’re a tax accountant, you recognize revenue when you deliver the completed tax return to the client. Book VIII Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions 506 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Recognizing revenue and cash flow With accrual accounting, you can recognize revenue prior to receiving any payment from the client. A company recognizes revenue as soon as it delivers the goods or services. For businesses that use accrual accounting, revenue recognized for the month may be very different from cash inflows for sales for the same period. Specifically, the increase in cash may not equal sales for the month. (See Book V, Chapter 2 for more about cash flows.) A business using cash-basis accounting recognizes revenue when the cash is received from the client. (See Book I, Chapter 4 for more about the difference between cash- and accrual-basis accounting.) If you review the checkbook of a cash-basis company, the deposits for the month will match the revenue for the month. Most businesses, however, use the accrual-basis of accounting. Chapter 2 Exploring Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions In This Chapter ▶ Seeing how inventory calculations impact financial statements ▶ Comparing service companies and manufacturers ▶ Recognizing a variety of inventory types ▶ Sampling inventory valuation methods ▶ Looking at an inventory worksheet S ome people think that inventory is only the merchandise available for sale in a store, commonly called retail or merchandise inventory. This chapter covers retail inventory, but it also introduces you to other kinds of product inventory used by manufacturers, including direct materials, work in process, and finished goods. You also find out in this chapter about two methods a company may use to keep track of merchandise inventory, as well as the four methods businesses may use to value ending inventory: specific identification; weighted average; last-in, first-out; and first-in, first-out. Some businesses, such as service companies, may not carry any inventory. Although they may carry a minimal amount of office supplies, they’re in the business of selling a service (legal advice, consulting) rather than a product. Discovering How Inventory Valuation Affects the Financial Statements In accounting, you’re preparing financial statements for users outside the business, such as investors and lenders (see Book I, Chapter 4). They need accurate financial statements to make informed decisions on whether they want to invest in the company or loan it money. 508 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Comparing merchandising and manufacturing companies For manufacturing companies (which make products) and merchandising companies (which sell the products made by the manufacturers), inventory can be a big part of the balance sheet. Along with accounts receivable, inventory may be the largest current asset account. So proper accounting for inventory is important, and that includes the value placed on ending inventory. A company can inadvertently prepare a set of highly inaccurate financial statements by expensing purchases rather than keeping them on the balance sheet as inventory (an asset account). So which costs are okay to expense directly on the income statement, and which costs should stay on the balance sheet as assets? Here’s a quick and dirty answer: Any item that a company buys for eventual sale to a customer should be recorded as inventory, which appears on the balance sheet. Connecting inventory to revenue Inventory ties into both the revenue process and the cost of goods sold (see Book IV, Chapter 6). Associating inventory with cost of goods sold makes common sense — you have to buy something before you can sell it. But you may be wondering how revenue and inventory relate to each other. Well, remember that you need to use generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), introduced in Book IV, Chapter 1. GAAP’s matching principle dictates that expenses are matched with revenue earned for the period. How does inventory come into the revenue equation? Book IV, Chapter 6 shows how to compute cost of goods sold for both a merchandising and a manufacturing company. Consider this process: ✓ Product costs are any costs that a company incurs when purchasing or manufacturing an item for sale to customers. Product costs are part of inventory (an asset account). ✓ When a sale occurs, product costs are posted to cost of goods sold (an expense account). ✓ Any product costs for unsold inventory remain in the inventory (asset) account at the end of the period. Chapter 2: Exploring Inventory Cost Flow Assumptions 509 Logging Inventory for Service Companies Although discussions of inventory focus on manufacturing and merchandising companies, you also need to consider service companies: those that don’t provide a tangible good and normally don’t have any appreciable inventory. However, if a service company keeps a large amount of office or other supplies on hand, it may inventory them instead of applying the cost of supplies purchased to the supply expense each month. Suppose a service company purchases supplies on account, which means the company promises to pay for them at a later date. The supplies cost $700 at the beginning of September. The $700 represents purchases. For this example, no beginning inventory exists for September. On the last day of September, an inventory is taken and supplies in the amount of $230 remain in the cabinet. Your journal entry to record the purchase is to debit supplies (an asset account) and credit accounts payable for $700. So far you haven’t affected the income statement. Now at the end of the month, you have to adjust supplies inventory to the actual on hand, which involves expensing the portion of supplies used. The company purchased $700 of supplies and only $230 remain, so you know that $700 – $230 = $470 of supplies were used and should be expensed for the month of September. So your journal entry is to debit supplies expense (an income statement account) and credit supplies (an asset account). Classifying Inventory Types Depending on the type of business, you’ll encounter different types of inventory. To make it easier for you to understand, this section breaks out the subject between inventory for merchandising companies and inventory for manufacturing companies. Accounting for merchandising company inventory Accounting for merchandise inventory is generally easier than accounting for manufacturing inventory. That’s because a merchandising company, such as a retail store, has only one class of inventory to keep track of: goods the business purchases from various manufacturers for resale. Book VIII Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions 510 Book VIII: Handling Cash and Making Purchase Decisions Here’s an example of the basic flow of inventory for a retailer: A linen sales associate at a major department store tells the manager that a certain