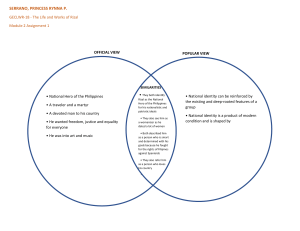

COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES SAINT THERESA COLLEGE OF TANDAG, INC. GENERAL EDUCATION AREA Semesters, A.Y. TEACHING-LEARNING MODULE Course Code Course Title Class Schedule Room No. Professor E-mail Address Consultation Hours : : : : : : : GE 9 Life and Works of Rizal Maria Satthia Q. Luna/Moises U. Palomo lunasatsat@gmail.com A. Course Description This course covers the significant life of Rizal his works and writings. It further discusses and critics how his writings meanly affect the rise of Filipino people before and emulate some of his plans and actions for our youth of the 20th century. The study of Dr. Jose P. Rizal’s life, works and writings has been mandated by Republic Act no. 1425 known as the Rizal law, enacted on June 12, 1956 and took effect on August 16, 1956. The law mandates that a course on the life of Dr. Jose Rizal should be included in the curricula in all schools.Furthermore, it analyzes the works and life of Rizal and how this contributes to our freedom and democracy. This course is essential for the students to understand and the historical contribution of Rizal to the present. B. Course Outcomes (CMO): At the end of the course, the students should be able to: 1. Understand Rizal Law in the context of maintaining Filipino values. 2. Explain how the life and works of Rizal affects students on the role of nation building. 3. Understand Rizal’s contribution to Philippine History and the present. C. Course Requirements: The course will focus on practicing the student’s ability to introspect and relate the contribution of historical events to modern-day Philippines and acknowledge its input on the lives of youths today. The life and works of Jose Rizal subject aims to bring Philippine education closer to what is needed and expected in the twenty-first century and makes the students realize the relevance of turning the Rizal Bill into Law. Page 1 of 72 MODULE 1 LESSON 1 UNDERSTANDING THE RIZAL LAW, NATION AND NATIONALISM Lesson Introduction: As an introduction to the life and works of Jose Rizal, you will study RA 1425 within its context, look into major issues and debates surrounding the bill and its passage into law, and reflect on the impact and relevance of this legislation throughout history and the present time. One of the major reasons behind the passage of the Rizal Law was the strong intent to instill nationalism in the hearts and minds of the Filipino youth. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) DAY 1 LESSON NO. LESSON TITLE DURATION/HOURS Specific Learning Outcomes: 1 Understanding the Rizal Law, Nation and Nationalism 3 1/2 Hours During the students' learning engagements, they will be able to: Determine the issues and interests at stake in the debate over Rizal Bill and relate the issues to the present-day Philippines. Define nationalism in relation to the concepts of nation, state, and nation-state. Appreciate the development of nationalism in the country and explain its relevance to nation-building at present. TEACHING LEARNING ACTIVITIES OPENING GUIDE QUESTIONS (5-minute Free Form formative assessment) 1. Why is there a need to make the Rizal Bill into Law? 2. How does a nation-state affect or influence a nation? Engaging Activity 1: Analysis (15-20 minutes) (LO 1: Determine the issues and interests at stake in the debate over Rizal Bill and relate the issues to the present-day Philippines). Instructions: Read the following excerpts from the statement of the legislators who supported and opposed the passage of the Rizal law in 1956. Then, answer the questions that follow. FOR "Noli Me Tångere and El Filibusterismo must be read by all Filipinos. They must be taken to heart, for in their pages we see ourselves as in a mirror, our defects as well as our strength, our virtues as well as our vices. Only then would we become conscious as a people and so learn to prepare ourselves for painful sacrifices that ultimately lead to self-reliance, self-respect, and freedom." — Senator Jose P. Laurel "Rizal did not pretend to teach religion when he wrote those books. He aimed at inculcating civic consciousness in the Filipinos, national dignity, personal pride, and patriotism and if references were made by him in the course of his narration to certain religious practices in the Philippines in those days, and to the conduct and behavior of erring ministers of the church, it was because he portrayed faithfully the general situation in the Philippines as it then existed." —Senator Claro M. Recto AGAINST "A vast majority of our people are, at the same time, Catholic and Filipino citizens. As such, they have two great loves: their country and their faith. These two loves are not conflicting loves. They are harmonious affections, like the love for his father and for his mother. This is the basis of my stand. Let us not create a conflict between nationalism and religion, between the government and the church." —Senator Francisco "Soc" Rodrigo 1. What was the major argument raised by Senator Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo against the passage of the Rizal Bill? _________________________________________________________________________________________ Page 2 of 72 _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. What were the major arguments raised by Senators Jose P. Laurel and Claro M. Recto in support of the passage of the Rizal Bill? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Are there points of convergence between the supporters and the opposers of the Rizal Bill based on these statements? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ Activity Processing: 1. How do you find the activity? 2. Does the activity help you understand our topic? How? Engaging Activity 2: Infographic (20 minutes) (LO 2: Define nationalism in relation to the concepts of nation, state, and nation-state). Instruction: Create an Infographic summarizing: The major roots of the theory of nation. The definitions of nation and nationalism, and their relationship to state and nation-state. The development of explanatory models of the origins of state and nation-state. The Context of the Rizal Bill How a Bill Becomes a Law: The Legislative Process The Senate and the House of Representatives follow the same Legislative procedure. Proposals emanate from a number of sources. They may be authored by the members of the Senate or House as part of their advocacies and agenda; produced through the lobbying from various sectors; or initiated by the executive branch of the government with the President's legislative agenda. Once a legislative proposal, like a bill, is ready, it will go through the steps discussed below. Step 1: Bill is filed in the Senate Office of the Secretary. It is given a number and is calendared for first reading. Step 2: First Reading. The bill’s title, number, and author(s) are read on the floor. Afterwards, it is referred to the appropriate committee. Step 3: Committee Hearings. The bill is discussed within the committee and a period of consultation is held. The committee can approve or reject. After the committee submits the committee report, the bill is calendared for second reading. Step 4: Second Reading. The bill is read and discussed on the floor; the author delivers a sponsorship speech. Other members of the Senate may engage in discussions regarding the bill and a period of debates will pursue. Amendments may be suggested. Step 5: Voting on Second Reading. The senators vote on whether to approve or reject the bill. If approved, the bill is calendared for third reading Step 6: Voting on Third Reading. Copies of the final versions of the bill are distributed to the members of the Senate who will vote for its approval or rejection. Step 7: Consolidation of Versions from the House. The similar steps are followed by the House of Representatives. If there are differences between the Senate and House versions, a bicameral conference committee is called to reconcile the two. After this, both chambers approve the consolidated version. Step 8: Transmittal of Final Versions to Malacanan. The bill is then submitted to the President for signing. The president can either sign the bill into a law or veto and return it to Congress. From the Rizal Bill to the Rizal Law On April 3, 1956, Senate Bill No. 438 was filed by the Senate Committee on Education. On April 17, 1956, then Senate Committee on Education Chair Jose P. Laurel sponsored the bill and began delivering speeches for the proposed legislation. Soon after, the bill became controversial as the powerful Catholic Church began to express opposition against its passage. As the influence of the Church was felt with members of the Senate voicing their opposition to the bill, its main author, Claro M. Recto, and his all ies in the Senate entered into a fierce battle arguing for the passage of SB 438. Debates started on April 23, 1956. The Page 3 of 72 debates on the Rizal Bill also ensued in the House of Representatives. House Bill No. 5561, an identical version of SB 438, was filed by Representative Jacobo Z. Gonzales on April 19, 1956. The House Committee on Education approved the bill without amendments on May 2, 1956 and the debates commenced on May 9, 1956. A major point of the debates was whether the compulsory reading of the tex ts. Noli Me Tångere and El Filibusterismo appropriated in the bill was constitutional. The call to read the unexpurgated versions was also challenged. As the country was soon engaged in the debate, it seemed that an impasse was reached. To move the procedure to the next step, Senator Jose P. Laurel proposed amendments to the bill on May 9, 1956. In particular, he removed the compulsory reading of Rizal's novels and added that Rizal's other works must also be included in the subject. He, however, remained adaman t in his stand that the unexpurgated versions of the novels be read. On May 14, 1956, similar amendments were adopted to the House version. The amended version of the bills was also subjected to scrutiny but seemed more palatable to the members of Congress. The passage, however, was almost hijacked by technicality since the House of Representatives was about to adjourn in a few days and President Ramon Magsaysay did not certify the bills as priority. The allies in the House skillfully avoided the insertion of any other amendment to prevent the need to reprint new copies (which would take time). They also asked the Bureau of Printing to use the same templates for the Senate version in printing the House version; Thus, on May 17, 1956, the Senate and House versions were approved. The approved versions were then transmitted to Malacanan and on June 12, 1956, President Magsaysay signed the bill into law which became Republic Act No. 1425. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) REPUBLIC ACT NO. 1425 AN ACT TO INCLUDE IN THE CURRICULA OF ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SCHOOLS, COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES COURSES ON THE LIFE, WORKS AND WRITINGS OF JOSE RIZAL, PARTICULARLY HIS NOVELS NOLI ME TANGERE AND EL FILIBUSTERISMO, AUTHORIZING THE PRINTING AND DISTRIBUTION THEREOF, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES WHEREAS, today, more than any other period of our history, there is a need for a re-dedication to the ideals of freedom and nationalism for which our heroes lived and died; WHEREAS, it is meet that in honoring them, particularly the national hero and patriot, Jose Rizal, we remember with special f ondness and devotion their lives and works that have shaped the national character; WHEREAS, the life, works and writing of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels Noli Me Tangere and E/ Filibusterismo, are a constant and inspiring source of patriotism with which the minds of the youth, especially during their formative and decisive years in sch ool, should be suffused; WHEREAS, all educational institutions are under the supervision of, and subject to regulation by the State, and all schools are enjoined to develop moral character, personal discipline, civic conscience and to teach the duties of citizenship; Now, therefore, SECTION 1. Courses on the life, works and writings of Jose Rizal, particularly his novels Noli Me Tangere and E/ Filibusterismo, shall b e included in the curricula of all schools, colleges and universities, public or private: Provided, That in the collegiate cour ses, the original or unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo or their English translation shall be used as basic texts. The Board of National Education is hereby authorized and directed to adopt forthwith measures to implement and carry out the provisions of this Section, including the writing and printing of appropriate primers, readers and textbooks. The Board shall, within sixty (60) days from the effectivity of this Act, promulgate rules and regulations, including those of a dis ciplinary nature, to carry out and enforce the provisions of this Act. The Board shall promulgate rules and regulations providing for the exemption of students for reasons of religious belief stated in a sworn written statement, from the requirement of the provision contained in the second part of the first paragraph of this section; but not from taking the course provided for in the first part of said paragraph. Said rules and regulations shall take effect thirty (30) days af ter their publication in the Official Gazette. SECTION 2. It shall be obligatory on all schools, colleges and universities to keep in their libraries an adequate number of copies of the original and unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, as well as of Rizal's other works and biography. The -said unexpurgated editions of the Noli Me Tangere and E/ Filibusterismo or their translations in English as well as other writings of Rizal shall be included in the list of approved books for required reading in all public or private schools, colleges and universities. The Board of National Education shall determine the adequacy of the number of books, depending upon the enrollment of the school, college or univer sity. SECTION 3. The Board of National Education shall cause the translation of the Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, as well as other writings of Jose Rizal into English, Tagalog and the principal Philippine dialects; cause them to be printed in cheap, popula r editions; and cause them to be distributed, free of charge, to persons desiring to read them, through the Purok organizations and Barrio Councils throughout the country. SECTION 4. Nothing in this Act shall be construed as amendment or repealing section nine hundred twenty -seven of the Administrative Code, prohibiting the discussion of religious doctrines by public school teachers and other persons engaged in any public school. SECTION 5. The sum of three hundred thousand pesos is hereby authorized to be appropriated out of any fund not otherwise a ppropriated in the National Treasury to carry out the purposes of this Act. SECTION 6. This Act shall take effect upon its approval. Approve d: June 12, 1956 Published in the Official Gazette, Vol. 52, No. 6, p. 2971 in June 1956. NATION AND NATIONALISM Page 4 of 72 Nation, State, Nation-State To better understand nationalism, one must learn first the concepts of nation and nationhood as well as state and nation-state: Nation: A group of people that shares a common culture, history, language and other practices like religion, affinity to a place etc. A nation is a community of people that are believed to share a link with one another based on cultural practices, language, religion or belief system, and historical experience, to name a few. A state, on the other hand, is a political entity that has sovereignty over a defined territory. States have laws, taxation, government, and bureaucracy— basically, the means of regulating life within the territory. This sovereignty needs diplomatic recognition to be legitimate and acknowledged internationally. The state's boundaries and territory are not fixed and change across time with war, sale, arbitration and negotiation, and even assimilation or secession. Zaide, G. et al. (1997) The nation-state, in a way, is a fusion of the elements of the nation (people/community) and the state (territory). The development of nationstates started in Europe during the periods coinciding with the Enlightenment. The "classical" nation-states of Europe began with the Peace of Westphalia in the seventeenth century. Many paths were taken towards the formation of the nation-states. In the "classical" nation-states, many scholars Nation-State: A state governing a posit that the process was an evolution from being a state into a nation-state in which the members of the bureaucracy (lawyers, politicians, diplomats, etc.) nation. eventually moved to unify the people within the state to build the nation- state. A second path was taken by subsequent nation-states which were formed from nations. In this process, intellectuals and scholars laid the foundations of a nation and worked towards the formation of political and eventually diplomatic recognition to create a nation-state. A third path taken by many Asian and African people involved breaking off from a colonial relationship, especially after World War II when a series of decolonization and nation-(re)building occurred. During this time, groups initially controlled by imperial powers started to assert their identity to form a nation and build their own state from the fragments of the broken colonial ties. A fourth path was by way of (sometimes violent) secessions by people already part of an existing state. Here, a group of people who refused to or could not identify with the rest of the population built a nation, asserted their own identity, and demanded recognition. In the contemporary world, the existing nation-states continuously strive with projects of nation-building especially since globalization and transnational connections are progressing. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) State: A political entity that wields sovereignty over a defined territory. Nation and Nationalism As mentioned, one major component of the nation-state is the nation. This concept assumes that there is a bond that connects a group of people together to form a community. The origin of the nation, and concomitantly nationalism, has been a subject of debates among social scientists and scholars. In this section, three theories about the roots of the nation will be presented. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) The first theory traces the root of the nation and national identity to existing and deep -rooted features of a group of people like race, language, religion, and others. Often called primordialism, it argues that a national identity has always existed and nations have "ethnic cores." In this essentialist stance, one may be led to conclude that divisions of "us" and "them" are naturally formed based on the assumption that there exists an unchanging core in everyone. The second theory states that nation, national identity, and nationalism are products of the modern condition and are shaped by modernity. This line of thinking suggests that nationalism and national identity are necessary products of the social structure and culture brought about by the emergence of capitalism, industrialization, secularization, urbanization, and bureaucratization. This idea further posits that in pre-modern societies, the rigid social hierarchies could accommodate diversity in Page 5 of 72 language and culture, in contrast with the present times in which rapid change pushes statehood to guard the homogeneity in society through nationalism. Thus, in the modernist explanation, nationalism is a political project. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) The third theory—a very influential explanation— about nation and nationalism maintains that these ideas are discursive. Often referred to as the constructivist approach o understanding nationalism, this view maintains that nationalism is socially constructed and imagined by people who identify with a group. Benedict Anderson argues that nations are "imagined communities" (2003). He traces the history of these i magined communities to the Enlightenment when European society began challenging the supposed divinely ordained dynastic regimes of the monarchies. This idea was starkly exemplified by the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution. The nation is seen as imagined because the people who affiliate with that community have a mental imprint of the affinity which maintains solidarity; they do not necessarily need to see and know all the members of the group. With this imagined community comes a "deep, hori zontal comradeship" that maintains harmonious co-existence and even fuels the willingness of the people to fight and die for that nation. Anderson also puts forward the important role of mass media in the construction of the nation during that time. He underscores that the media (1) fostered unified fields of communication which allowed the millions of people within a territory to "know" each other through printed outputs and become aware that many others identified with the same community; (2) standardized languages that enhanced feelings of nationalism and community; and (3) maintained communication through a few languages widely used in the printing press which endured through time. Pangilinan, M. (2016) Nation and Bayan In the Philippines, many argue that the project of nation-building is a continuing struggle up to the present. Considering the country's history, historians posit that the nineteenth century brought a tremendous change in the lives of the Filipinos, including the actual articulations of nation and nationhood that culminated in the first anti-colonial revolution in Asia led by Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan. Furthermore, scholars note the important work of the propagandists like Rizal in the sustained efforts to build the nation and enact change in the Spanish colony. As you continue to familiarize yourselves with the concepts of nation and nationalism, it would be worthwhile to look at how these ideas have been articulated in the past as well as how scholars locate these efforts in the indigenous culture. Many Filipino scholars who endeavored to understand indigenous/local knowledge have identified concepts that relate to how Filipinos understand the notions of community and, to an extent, nation and nation-building. The works of Virgilio Enriquez, Prospero Covar, and Zeus Salazar, among others, attempted to identify and differentiate local categories for communities and social relations. The indigenous intellectual movements like Sikolohiyang Pilipino and Bagong Kasaysayan introduced the concepts of kapwa and bayan that can enrich discussions about nationalism in the context of the Philippines. Kapwa is an important concept in the country's social relations. Filipino interaction is mediated by understanding one's affinity with another as described by the phrases "ibang tao" and "'di ibang tao." In the formation and strengthening of social relations, the kapwa concept supports the notion of unity and harmony in a community. From this central concept arise other notions such as "pakikipagkapwa," "pakikisama," and "pakikipag-ugnay," as well as the collective orientation of Filipino culture and psyche. In the field of history, a major movement in the indigenization campaign is led by Bagong Kasaysayan, founded by Zeus Salazar, which advances the perspective known as Pantayong Pananaw. Scholars in this movement are among the major researchers that nuance the notion of bayan or banua. In understanding Filipino concepts of community, the bayan is an important indigenous concept. Bayan/Banua, which can be traced all the way to the Austronesian language family, is loosely defined as the territory where the people live or the actual community they are identifying with. Thus, bayan/banua encompasses both the spatial community as well as the imagined community. The concept of bayan clashed with the European notion of naciön during the Spanish colonialism. The proponents of Pantayong Pananaw maintain the existence of a great cultural divide that separated the elite (naciön) and the folk/masses (bayan) a s a product of the colonial experience. This issue brings the project of nation-building to a contested terrain. Throughout Philippine history, the challenge of building the Filipino nation has persisted, impacted by colonialism, violent invasion during World War II, a dictatorship, and the perennial struggle for development. The succeeding chapters will look into the life and works of José Rizal and through them, try to map how historical events shaped the national hero's understanding of the nation and nationalism. Zulueta, F. (2004) Moving on... Individual Guide Processing Questions: Page 6 of 72 1. How does the influence of kapwa contribute to modern-day interactions? 2. What is the relevance of the Rizal Law to your present life as a student? (5-10-minute engagements) Formative Activity 1: ESSAY (15 minutes) Instructions: Answer the following questions below. 1.Do you think Rizal subject should be integrated in our curriculum? 2.Do you think the debates on the Rizal Law have some resonance up to the present? If yes, in what way? If no, why? 3. How does nationalism contribute to nation-building at present? Activity Processing: 1. How did you find the activity? 2. Does the activity help you understand our topic? How? Rubrics: Criteria Creativity Clarity of Content Score Ideas were written creatively(10) Ideas were expressed in a clearly (10) Organization Ideas were organized and were easy to understand (10) Ideas were written fairly creative(5) Ideas were expressed in a pretty clear manner(5) Ideas were expressed but could have been organized better (5) Total Ideas were dull and incoherent(3) Ideas were not clearly expressed (3) Ideas seemed to be a collection of unrelated sentences and are difficult to understand (3) SYNTHESIS: The lesson focuses on the Rizal Law and how it is considered a landmark legislation in the postwar Philippines. During this period, the Philippines were trying to get up on its feet from a devastating war and aiming towards nation-building. The imperative of instilling nationalism in the minds of the youth was a major factor behind the passage of the Rizal Law. ASSESSMENTS TEST I- All competencies/outcomes (EA1 Analysis, EA2 Infographic, FA1 Essay) are graded and are recorded as major assessments. TEST II– Examine each statement. Write “True” if the statement is correct, and write “False” If the statement is incorrect. 1. The Rizal Law could be considered a landmark legislation in the postwar Philippines. 2. Teaching Jose Rizal’s life and works is not mandated to all public and private educational institutions. 3. Nation is defined as a state governing nation. 4. Nation-state is a political entity that wields sovereignty over a defined territory. 5. State is a group of people that shares common culture, Page 7 of 72 history and language. 6. Primordialism argues that a nation identity has always existed and nations have ethnic cores. 7. Nation, national identity and nationalism are products of modern condition and are shaped by modernity. 8. Deeper unconscious level where true meaning of dream lies is called Latent Content 9. Kapwa is a Filipino interaction mediated by understanding one’s affinity with another. 10. One of the major reasons of Rizal Law is to instill nationalism in the hearts and minds of Filipino youth. TEST III-ANALYZE AND EVALUATE Instructions: Answer the questions below: 1. Recall an experience where you portrayed nationalism. 2. From the experience that you recalled, cite the relevance of nationalism and its influence on your self-concept as a Filipino citizen? ASSIGNMENTS Instructions: Answer the question below: 1. In what way does the Life and Works of Rizal as a subject relate to your present life as a student? RESOURCES: Prepared by: MARIA SATTHIA Q. LUNA MOISES U. PALOMO Instructor/s Zaide, Gregorio F. and Sonia M. Zaide (1997)Jose Rizal; Life, Works, and Writings of a genius, Writer, Scientist and National Hero All Nation Publishing Co. Inc. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) The Life and Works of Jose Rizal. C & E Publishing Inc.. Metro Manila Pangilinan, M. (2016) Dr. Jose P. Rizal Life, Works and Writings, C&E Publishing Co. Manila Zulueta, Francisco M. (2004) Rizal’s , works and ideals, National Bookstore Reviewed by: Program Chair Verified and validated by: Dean, College of Page 8 of 72 Approved by: Vice President for Academic Services MODULE 1 LESSON 2 REMEMBERING RIZAL AND THE LIFE OF JOSE RIZAL Lesson Introduction: Jose Rizal lived in the nineteenth century, a period in Philippine history when changes in public consciousness were already being felt and progressive ideas were being realized. Rizal's execution on December 30, 1896 became an important turning point in the history of Philippine revolution. His death activated the full-scale revolution that resulted in the declaration of Philippine independence by 1898. Under the American colonial government, Rizal was considered as one of the most important Filipino heroe s of the revolution and was even declared as the National Hero by the Taft Commission, also called the Philippine Commission of 1901. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) DAY 1 LESSON NO. LESSON TITLE DURATION/HOURS Specific Learning Outcomes: 2 Remembering Rizal And The Life of Jose Rizal 3 1/2 Hours During the students' learning engagements, they will be able to: Evaluate Rizal’s heroism and importance in the context of Rizalista groups. Compare and contrast the different views on Rizal among the Rizalistas. Discuss about Rizal’s family, childhood, and early education and its relevance to the factors that led to his execution. TEACHING LEARNING ACTIVITIES OPENING GUIDE QUESTIONS (5-minute Free Form formative assessment) 1. What was the purpose of Rizal groups? 2. Why was Rizal honored as the “Filipino Jesus Christ”? 3. What are the events that influenced Rizal’s early life? Engaging Activity 1: Analysis (15-20 minutes) (LO 1: Evaluate Rizal’s heroism and importance in the context of Rizalista groups). Instruction: Briefly answer the following: 1. How do Rizalista groups view Jose Rizal and other National Heroes? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 2. What are the similarities between Jesus Christ and Rizal as seen by the millenarian groups? _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Name some influencial women in various Rizalista groups and explain their significant roles in their respective organizations.______________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________ Activity Processing: 1. How do you find the activity? 2. Does the activity help you understand our topic? How? Engaging Activity 2: Venn Diagram (20 minutes) (LO 2: Compare and contrast the different views on Rizal among the Rizalistas). Instruction: Choose two of the Rizalista groups that were discussed. On a separate sheet of paper, create a Venn Diagram showing the beliefs and practices that are similar and different between the two groups. Page 9 of 72 G 1 Differences Similarities G 2 Differences REMEMBERING RIZAL A Rizal monument was built in every town and December 30 was declared as a national holiday to commemorate his death and heroism. In some provinces, men—most of whom were professionals— organized and became members of Caballeros de Rizal, now known as the Knights of Rizal. Influenced by both the Roman Catholic Church and the pre-hispanic spiritual culture, some Filipino masses likewise founded organizations that recognize Rizal not just as an important hero but also as their savior from all the social ills that plague the country. These groups, which can be linked to the long history of millenarian movements in the country, are widely known as the Rizalistas. These organizations believe that Rizal has a Latin name of Jove Rex A1, which literally means "God, King of All." Zaide, G. et al (1997) The Canonization of Rizal: Tracing the Roots of Rizalistas The earliest record about Rizal being declared as a saint is that of his canonization initiated by the Philippine Independent Church (PIC) or La Iglesia Filipina Independiente. Founded on August 3, 1902, the PIC became a major religious sect with a number of followers supporting its anti-friar and anti-imperialist campaigns. As a nationalist religious institution, PIC churches displayed Philippine flags in its altars as an expression of their love of country and recognition of heroes who fought for our independence (Palafox, 2012). In 1903, the PIC'S official organ published the "Acta de Canonizacion de los Grandes Martires de la Patria Dr. Rizal y PP. Burgos, Gomez y Zamora" (Proceedings of the Canonization of the Great Martyrs of the Country Dr. Rizal and Fathers Burgos, Gomez and Zamora). According to the proceedings, the Council of Bishops headed by Gregorio Aglipay met in Manila on September 24, 1903. On this day, José Rizal and the three priests were canonized following the Roman Catholic rites. After Rizal's canonization, Aglipay ordered that no masses for the dead shall be offered to Rizal and the three priests. Their birth and death anniversaries will instead be celebrated in honor of their newly declared sainthood. Their statues were revered at the altars; their names were given at baptism; and, in the case of Rizal, novenas were composed in his honor. PIC's teachings were inspired by Rizal's ideology and writings. One of PIC'S founders, Isabelo de los Reyes, said that Rizal's canonization was an expression of the "intensely nationalistic phase" of the sect (Foronda, 2001). Today, Rizal's pictures or statues can no longer be seen in the altars of PIC. His birthday and death anniversary are no longer celebrated. However, it did not deter the establishment of other Rizalista organizations. Groups Venerating José Rizal Adarnista or the Iglesiang Pilipina In 1901, a woman in her thirties, Candida alantac of Ilocos Norte, was said to have started preaching in Bangar, La Union. Balantac, now known as the founder of Adarnista or the Iglesiang Pilipina, won the hearts of her followers from La Union, Pangasinan, and Tarlac. This preaching eventually led her to establish the organization in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija where she resided until the 1960s (Ocampo, 2011). Balantac's followers believe that she was an engkantada (enchanted one) and claimed that a rainbow is formed (like that of Ibong Adarna) around Balantac while she preached, giving her the title "Inang Adarna" and the organization's name, Adarnista. Others call Balantac Maestra (teacher) and Espiritu Santo (Holy Spirit). The members of the Adarnista believe in the following (Foronda, 2001): - Rizal is a god of the Filipino people. - Rizal is true god and a true man. - Rizal was not executed as has been mentioned by historians. - Man is endowed with a soul; as such, man is capable of good deeds. - Heaven and hell exist but are, nevertheless, "within us." - The abode of the members of the sect in Bongabon, Nueva Eciia is the New Jerusalem or Paradise. - The caves in Bongabon are the dwelling place of Jehovah or God. - There are four persons in God: God, the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost, and the Mother (Virgin Mary). Like the Catholic Church, the Adarnista also conducts sacraments such as baptism, confirmation, marriage, confession, and rites of the dead. Masses are held every Wednesday and Sunday, at 7:00 in the morning and lasts up to two hours. Special religious ceremonies are conducted on Rizal's birthday and his death anniversary which start with the raising of the Filipino flag. In a typical Adarnista chapel, one can see images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Our Lady of Perpetual Help, and in the center is the picture of Rizal. The Adarnista has more than 10,000 followers. Sambahang Rizal Literally the "Rizal Church," the Sambahang Rizal was founded by the late Basilio Aromin, a lawyer in Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija, in 1918. Aromin was able to attract followers with his claim that Sambahang Rizal was established to honor Rizal who was sent by Bathala to redeem the Filipino race, like Jesus Christ who offered His life to save mankind (Foronda, 2001). Bathala is the term used by early Filipinos to refer to "God" or "Creator." Aromin's group believes that Rizal is the "Son of Bathala" in the same way that Jesus Christ is the "Son of God." Noli Me Tångere and El Filibusterismo serve as their "bible" that shows the doctrines and teachings of Rizal. Their churches have altars displaying the Philippine flag and a statue of Rizal. Similar to the Catholic Church, the Sambahang Rizal conducts sacraments like baptism, confirmation, marriage, and ceremonies for the dead. It assigns preachers, called lalawigan guru, who are expected to preach Rizal's teachings in different provinces. Aromin, the founder, held the title Pangulu guru (chief preacher). At the height of its popularity, the organization had about 7,000 followers found in Nueva Ecija and Pangasinan (Foronda, 2001). Rizal as the Tagalog Christ In late 1898 and early 1899, revolutionary newspapers La Independencia and El Heraldo de la Revolucion reported about Filipinos commemorating Rizal's death in various towns in the country. In Batangas, for example, people were said to have gathered "tearfully wailing before a portrait of Rizal" (Ileto, 1998) while remembering how Christ went through the same struggles. After Rizal's execution, peasants in Laguna were also reported to have regarded him as "the lord of a kind of paradise in the heart of Mount Makiling" (Ileto, 1998). Similar stories continued to spread after Rizal's death towards the end of t he Page 10 of 72 nineteenth century. The early decades of 1900s then witnessed the founding of different religious organizations honoring Rizal as the "Filipino Jesus Christ" (Ocampo, 2011). In 1907, Spanish writer and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno gave Rizal the title "Tagalog Christ" as religious organizations venerating him had been formed in different parts of the Philippines (Iya, 2012). The titles given to some earlier Filipino revolutionary leaders reveal that associating religious beliefs in the social movement i s part of the country's history. Teachings and traditions of political movements that were organized to fight the Spanish and American colonial powers were rooted in religious beliefs and practices. These socio -religious movements known as the millenarian groups which aim to transform the society are often symbolized or represented by a hero or prophet. The same can also be said with the Rizalista groups which, as mentioned, have risen in some parts of the country after Rizal's death in 1896. Each group has its own teachings, practices, and celebrations, but one common belief among them is the veneration of José Rizal as the reincarnation of Jesus Christ. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) People saw the parallel between the two lives being sent into the world to fulfill a purpose. As Trillana (2006, p. 39) puts it, "For both Jesus and Rizal, life on earth was a summon and submission to a call. From the beginning, both knew or had intimations of a mission they had to fulfill, the redemption of mankind from sin in the case of Jesus and the redemption of his people from oppression in the case of Rizal." Reincarnation in the context of Rizalistas means that both Rizal and Jesus led parallel lives. "Both were Asians, had brilliant minds and extraordinary talents. Both believed in the Golden Rule, cured the sick, were rabid reformers, believed in the universal brotherhood of men, were closely associated with a small group of followers. Both died young (Christ at 33 and Rizal at 35) at the hands of their enemies. Their liv es changed the course of history" (Mercado, 1982, p. 38). THE LIFE OF JOSE RIZAL Rizal's Family José Rizal was born on June 19, 1861 in the town of Calamba, province of Laguna. Lam-co is said to have come from the district of Fujian in southern China and migrated to the Philippines in the late 1600s. In 1697, he was baptized in Binondo, adopting "Domingo" as his first name. He married Ines de la Rosa of a kn own entrepreneurial family in Binondo. Domingo and Ines had a son whom they named Francisco Mercado. The surname "Mercado," which means "market," He had a son named Juan Mercado who was also elected as capitan del pueblo in 1808, 1813, and 1823 (Reyno, 2012 as cited in Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018). Juan Mercado married Cirila Alejandra, a native of Binan. They had 13 children, including Francisco Engracio, the father of José Rizal. In 1848, Francisco married Teodora Alonso (1826—1911) who belonged to one of the wealthiest families in Manila. (Letter to Blumentritt, November 8, 1888). José Rizal (1861 —1896) is the seventh among the eleven children of Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso. The other children were: Saturnina (1850—1913); Paciano (1851—1930); Narcisa (1852-1939); Olimpia (1855-1887); Lucia (18571919); Maria (1859—1945); Concepcion (1862—1865); Josefa (1865-1945); Trinidad (1868-1951); and Soledad (1870-1929). Pangilinan, M. (2016) Childhood and Early Education Page 11 of 72 As a young boy, Rizal demonstrated intelligence and learned easily. His first teacher was Doria Teodora who taught him how to pray. He was only three years old when he learned the alphabet. At a very young age, he already showed a great interest in reading books. He enjoyed staying in their library at home with his mother. Eventually, Dofia Teodora would notice Rizal's skills in poetry. She would ask him to write verses. Later, she felt the need for a private tutor for the young Rizal. Just like the other children from the principalia class, Rizal experienced education under private tutors. His first private tutor was Maestro Celestino followed by Maestro Lucas Padua. But it was Leon Monroy, his third tutor, who honed his skills in basic Latin, reading, and writing. This home education from private tutors prepared Rizal to formal schooling which he first experienced in Binan. At the age of nine, Rizal left Calamba with his brother to study in Binan. In Binan, he excelled in Latin and Spanish. He also had painting lessons under Maestro Cruz' father-in-law, Juancho, an old painter. Rizal's leisure hours were mostly spent in Juancho's studio where he was given free lessons in painting and drawing. After receiving a letter from his sister, Saturnina, Rizal returned to Calamba on December 17, 1870 after one-and-a-half year of schooling in Binan. He went home on board the steamship Talim and was accompanied by Arturo Camps, a Frenchman and friend of his father (P. Jacinto, 1879 as cited in WaniObias, R et al. (2018). Student of Manila Rizal was sent by his father to Ateneo Municipal, formerly known as Escuela Pia, for a six -year program, Bachiller en Artes. He took the entrance exam on June 10, 1872, four months after the execution of Gomburza. He followed the advice of his brother, Paciano, to use the name José Rizal instead of Jose Mercado. He feared that Rizal might run into trouble if it was known openly that they were brothers since Paciano was known to have links to Jose Burgos, one of the leaders of the secularization movement and one of three priests executed. During this time, Ateneo Municipal was known to offer the best education for boys. Like all colleges in Manila, Ateneo was managed by priests, but with an important difference in t he sense that these religious were not friars but Jesuit Fathers. Ateneo was also known for its rigid discipline and religious instruction that trained students' character. Students in Ateneo were divided into two groups, the Romans and the Carthaginians. The Roman Empire was composed of students boarding at Ateneo while the Carthaginian Empire was composed of non-boarding students. This grouping was done to stimulate the spirit of competition among the students. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) Rizal studied at Ateneo from 1872—1877. In those years, he consistently showed excellence in his academic performance. He passed the oral examination on March 14, 1877 and graduated with a degree Bachiller en Artes, with the highest honors. After finishing Bachiller en Artes, Rizal was sent by Don Francisco to the University of Santo Tomas. Initially, Dofia Teodora opposed the idea for fear of what had happened to Gomburza. Despite this, Rizal still pursued university education and enrolled in UST. During his freshman year (1877—1878), he attended the course Philosophy and Letters. Also in the same year, he took up a vocational course in Ateneo that gave him the title perito agrimensor (expert surveyor) issued on November 25, 1881. In his second year at UST, Rizal shifted his course to Medicine. He felt the need to take up this course after learning about his mother's failing eyesight. Rizal's academic performance in UST was not as impressive as that in Ateneo. He was a good student in Medicine but not as gifted as he was in Arts and Letters. In 1882, Rizal and Paciano made a secret pact—Rizal would go to Europe to complete his medical studies there and prepare himself for the great task of liberating the country from Spanish tyranny. Rizal in Europe On May 3, 1882, Rizal left the Philippines for Spain. In his first trip abroad, Rizal was very excited to learn new things. Rizal reached Barcelona on June 16, 1882. In this city, Rizal found time to write an essay entitled " El Amor Patrio" (Love of Country). Rizal was awarded with the degree and title of Licentiate in Medicine for passing the medical examinations in June 1884. With this title, Rizal was able to practice medicine. Rizal also took examinations in Greek, Latin, and world history. He won the first prize in Greek and a grade of "excellent" in history. He also obtained the degree Licenciado en Filosofia y Letras (Licentiate in Philosophy and Letters) from the Universidad Central de Madrid on June 19, 1885 with a rating of sobresaliente. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) In between his studies, Rizal made time for meeting fellow Filipinos in Madrid. Known as ilustrados, these Page 12 of 72 Filipinos (enlightened ones) formed the Circulo Hispano-Filipino which held informal programs with activities like poetry-reading and debates. As a prolific writer and poet, Rizal was asked to write a poem. As a result, he wrote Mi Piden Versos (They Ask Me for Verses). It was in Madrid that he was able to write the first half of his novel, Noli Me Tångere. While in Madrid, Rizal was exposed to liberal ideas through the masons that he met. He was impressed with the masons' view about knowledge and reasoning and how they value brotherhood. He joined the Masonry and became a Master Mason at the Lodge Solidaridad on November 15, 1890. Filipinos in Madrid occasionally visited Don Pablo ortiga y Rey, the former city mayor of Manila under the term of Governor-General carios Maria de la Torre. Rizal joined his fellow Filipinos at Don Pablo's house where he met and became attracted to Consuelo, Don Pablo's daughter. However, Rizal did not pursue her because of his commitment to Leonor Rivera. His friend, Eduardo de Lete, was also in love with Consuelo but did not want to ruin their friendship. Zulueta, F. (2004) Rizal specialized in ophthalmology and trained under the leading ophthalmologists in Europe like Dr. Louis de Weckert of Paris for whom he worked as an assistant from October 1885 to March 1886. In Germany, he also worked with expert ophthalmologists Dr. Javier Galezowsky and Dr. Otto Becker in Heidelberg in 1886 and Dr. R. Schulzer and Dr. Schwiegger in 1887 (De Viana, 2011). During his stay in Germany, Rizal befriended different scholars like Fredrich Ratzel, a German historian. Through his friend, Ferdinand Blumentritt, Rizal was also able to meet Feodor Jagor and Hans Virchow, anthropologists who were doing studies on Philippine culture. Rizal mastered the German language and wrote a paper entitled Tagalische Verkunst (Tagalog Metrical Art). He also translated Schiller's William Tell into Tagalog in 188 6. It was also in Berlin where he finished Noli Me Tångere which was published on March 21, 1887 with financial help from his friend Maximo Viola. After five years in Europe, Rizal went home to Calamba on August 8, 1887. He spent time with the members of his family who were delighted to see him again. He also kept himself busy by opening a medical clinic and curing the sick. He came to be known as Doctor Uliman as he was mistaken for a German. His vacation, however, was cut short because he was targeted by the friars who were portrayed negatively in his novel Noli Me Tångere. He left the country for the second time on February 16, 1888. WaniObias, R et al. (2018) Rizal's Second Trip to Europe In his second trip, Rizal became more active in the Propaganda Movement with fellow ilustrados like Marcelo H. del Pilar, Graciano Lopez Jaena, Antonio Luna, Mariano Ponce, and Trinidad Pardo de Tavera. The Propaganda Movement campaigned for reforms such as: (1) for the Philippines to be made a province of Spain so that native Filipinos would have equal rights accorded to Spaniards; (2) representation of the Philippines in the Spanish Cortes; and (3) secularization of parishes. Rizal became preoccupied with writing articles and essays which were published in the Propaganda Movement's newspaper, La Solidaridad. Among his intellectual works in Europe is his annotation of Antonio de Morga's Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (1890) in which Rizal showed that even before the coming of the Spaniards, the Filipinos already had a developed culture. He also wrote an essay entitled "Sobre la Indolencia de los Filipinos" (On the Indolence of the Filipinos) published in 1890 in which he attributed the Filipinos' "indolence" to different factors such as climate and social disorders. Another essay he wrote strongly called for reforms; it was called "Filipinas Dentro de Cien Aios" (The Philippines a Century Hence) published in parts from 1889 to 1890. By July 1891, while in Brussels, Rizal completed his second novel, El Filibusterismo, which was published on September 18, 1891 through the help of his friend, Valentin Ventura. Compared with his Noli, Rizal's El Fili was more radical with its narrative portrayed of a society on the verge of a revolution. Zulueta, F. (2004) In 1892, Rizal decided to return to the Philippines thinking that the real struggle was in his homeland. In spite of warnings and his family's disapproval, Rizal arrived in the Philippines on June 26, 1892. Imme diately, he visited his friends in Central Luzon and encouraged them to join the La Liga Filipina, a socio -civic organization that Rizal established on July 3, 1892. Unfortunately, just a few days after the Liga's formation, Rizal was arrested and brought to Fort Santiago on July 6, 1892. He was charged with bringing with him from Hong Kong leaflets entitled Pobres Frailes (Poor Friars), a satire against the rich Dominican friars and their accumulation of wealth which was against their vow of poverty. In spite of his protests and denial of having those materials, Rizal was exiled to Dapitan in Mindanao. Exile in Dapitan Rizal arrived in Dapitan on board the steamer Cebu on July 17, 1892. Dapitan (now a city within Zamboanga Page 13 of 72 del Norte) was a remote town in Mindanao which served as a politico-military outpost of the Spaniards in the Philippines. It was headed by Captain Ricardo Carnicero, who became a friend of Rizal during his exile. He gave Rizal the permission to explore the place and required him to report once a week in his office. The quiet place of Dapitan became Rizal's home from 1892 to 1896. Here, he practiced medicine, pursued scientific studies, and continued his artistic pursuits in sculpture, painting, sketching, and writing poetry. He established a school for boys and promoted community development projects. He also found time to study the Malayan language and other Philippine languages. He engaged himself in farming and commerce and even invented a wooden machine for making bricks. On September 21, 1892, Rizal won the second prize in a lottery together with Ricardo Carnicero and another Spaniard. His share amounted to 6,200 pesos. A portion of Rizal's winnings was used in purchasing land approximately one kilomete r away from Dapitan in a place known as Talisay. He built his house on the seashore of Talisay as well as a school and a hospital within the area. In his letter to Blumentritt (December 19, 1893), Relative to Rizal's project to improve and beautify Dapitan, he made a big relief map of Mindanao in the plaza and used it to teach geography. With this map, which still exists today, he discussed to the town people the position of Dapitan in relation to other places of Mindanao. Assisted by his pupils, Rizal al so constructed a water system to supply the town with water for drinking and irrigation. He also helped the people in putting up lampposts at every corner of the town. Having heard of Rizal's fame as an ophthalmologist, George Taufer who was suffering from an eye ailment traveled from Hong Kong to Dapitan. He was accompanied by his adopted daughter, Josephine Bracken, who eventually fell in love with Rizal. They lived as husband and wife in Rizal's octagonal house after being denied the sacrament of marriag e by Father Obach, the parish priest of Dapitan, due to Rizal's refusal to retract his statements against the Church and to accept other conditions. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) On the eve of June 21, 1896, Dr. Pio Valenzuela visited Rizal in Dapitan and i nformed him about the founding of Katipunan and the planned revolution. Rizal objected to it, citing the importance of a well -planned movement with sufficient arms. Meanwhile, Rizal had been sending letters to then Governor -General Ramon Blanco. Twice he sent letters, one in 1894 and another in 1895. He asked for a review of his case. He said that if his request would not be granted, he would volunteer to serve as a surgeon under the Spanish army fighting in the Cuban revolution. On July 30, 1896, Rizal's request to go to Cuba was approved. The next day, he left for Manila on board the steamer Espaüa. And on September 3, 1896, he boarded the steamer Isla de Panay which would bring him to Barcelona. Upon arriving at the fort, however, Governor -General Despujol told him that there was an order to ship him back to Manila. On November 3, 1896, Rizal arrived in Manila and was immediately brought to Fort Santiago. Trial and Execution The preliminary investigation of Rizal's case began on November 20, 1896. He was accused of being the main organizer of the revolution by having proliferated the ideas of rebellion and of founding illegal organizations. Rizal pleaded not guilty and even wrote a manifesto appealing to the revolutionaries to discontinue the uprising. Rizal's lawyer, Lt. Luis Taviel de Andrade, tried his best to save Rizal. However, on December 26, 1896, the trial ended and the sentence was read. José Rizal was found guilty and sentenced to death by firing squad. On December 28, 1896, Governor-General Camilo de Polavieja signed the court decision. He later decreed that Rizal be executed by firing squad at 7:00 a.m. of December 30. Rizal, on his last remaining days, composed his longest poem, Mi Ultimo Adios, which was about his farewell to the Filipino people. When his mother and sisters visited him on December 29, 1896, Rizal gave away his remaining possessions. He handed his gas lamp to his sister Trinidad and murmured softly in English, "There is something inside." Eventually, Trining and her sister Maria would extract from the lamp the copy of Rizal's last poem. At 6:30 in the morning of December 30, 1896, Rizal, in black suit with his arms tied behind his back, walked to Bagumbayan. The orders were given and shots were fired. Consummatum est! ("It is finished!" ) Rizal died offering his life for his country and its freedom. WaniObias, R et al. (2018) Moving on... Individual Guide Processing Questions: 1. How does Rizal’s family and childhood influence his early success? 2. Why was Jose Rizal executed? Page 14 of 72 (10-minute engagements) Formative Activity 1: CONCEPT MAP (15 minutes) (LO 3: Discuss about Rizal’s family, childhood, and early education and its relevance to the factors that led to his execution). Instruction: Pick one aspect of Rizal’s life (e.g family, early education, etc.). Research further on this aspect of Rizal’s life and create a Concept Map. Activity Processing: 1. How did you find the activity? 2. Does the activity help you understand our topic? How? SYNTHESIS: The lesson focuses on how Rizal’s ideas and works were influenced by his education in Manila and later in Europe. His active participation in the Propaganda Movement made him one of the most known reformist. The lesson further discusses the emergence of Rizalista Groups in different parts of the country could be associated with the long struggle of Filipinos for freedom and independence. ASSESSMENTS TEST I- All competencies/outcomes (EA1 Analysis, EA2 Venn Diagram, FA1 Concept Map) are graded and are recorded as major assessments. TEST II– Briefly answer the following: 1. Describe the background of Rizal’s ancestry that might have contributed to his life and education. 2. Compare the experiences of Rizal as a student in Ateneo Municipal, UST, and Madrid. 3. Who were the important persons that influenced Rizal in his intellectual persuits? 4. What were Rizal’s activities in Dapitan and their impact? 5. How would you assess Rizal’s objection to the revolution? TEST III-ANALYZE AND EVALUATE Instruction: Create an Infographic that contains people or events that influenced Rizal’s early life. Rubrics: Criteria Creativity Clarity of Content Score Ideas were written creatively(10) Ideas were expressed in a clearly (10) Organization Ideas were organized and were easy to understand (10) ASSIGNMENTS Ideas were written fairly creative(5) Ideas were expressed in a pretty clear manner(5) Ideas were expressed but could have been organized better (5) Total Ideas were dull and incoherent(3) Ideas were not clearly expressed (3) Ideas seemed to be a collection of unrelated sentences and are difficult to understand (3) Write a 1-2 paragraph essay about your view or reaction about the topics discussed above. Page 15 of 72 RESOURCES: Prepared by: MARIA SATTHIA Q. LUNA MOISES U. PALOMO Instructor/s Zaide, Gregorio F. and Sonia M. Zaide (1997)Jose Rizal; Life, Works, and Writings of a genius, Writer, Scientist and National Hero All Nation Publishing Co. Inc. Wani-Obias, R et al. (2018) The Life and Works of Jose Rizal. C & E Publishing Inc.. Metro Manila Pangilinan, M. (2016) Dr. Jose P. Rizal Life, Works and Writings, C&E Publishing Co. Manila Zulueta, Francisco M. (2004) Rizal’s , works and ideals, National Bookstore Reviewed by: Program Chair Verified and validated by: Dean, College of Page 16 of 72 Approved by: Vice President for Academic Services