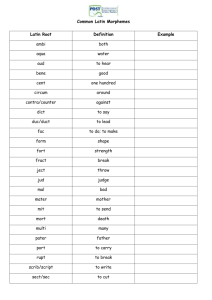

3rd year 1st term • • • • • • • Linguistics 2021-2022 Characteristics of human language and language acquisition Language capacity is species-specific; it is restricted to humans. The ability to acquire language is independent of intelligence. Whether a child is intelligent or not, he or she will acquire and produce language relatively at the same age. Language is acquired with relative ease. It is not difficult for children to acquire their first language (mother tongue). Children acquire language without instruction. Children show creativity which goes beyond the input they are exposed to. Creativity means that they produce and understand utterances they have never heard before. Children are as proficient as adults at using language. Children are unaware of the linguistic knowledge which enables them to use language because their linguistic knowledge is unconscious. Linguistic Knowledge (Competence) The linguistic knowledge of the native speaker is unconscious. Linguistic knowledge includes knowledge of the sound system, knowledge of words, and knowledge of sentence structure. Knowledge of the sound system • Knowledge of the sound system includes knowing the inventory of sounds, what sounds are in a language and what sounds are not. For example, the sound /v/ is not part of the Arabic sound system. • It allows native speakers to pronounce words correctly. • It allows native speakers to unconsciously divide words into syllables, for example: beautiful = beau·ti·ful. • It includes knowing the phonological rules of the language like assimilation. Assimilation is a process in which neighboring sounds become similar. For example, a native speaker would say "haf to" instead of "have to". • It enables native speakers to stress words correctly. For example, the word object is stressed on the first syllable as a noun, 'object, and on the second as a verb ob'ject. Knowledge of words • Knowing a language includes knowing that certain sound sequences signify certain concepts or meanings. • The relationship between sequences of sounds and the meanings they represent is arbitrary. Arbitrariness means that there is no one-to-one relationship between form and meaning. • However, in Onomatopoeic words such as: meow ()مواء القطة, buzz ( )أزيزor tick ( )دقة الساعةthere is a natural relationship between form and meaning. Knowledge of sentence structure • Memorization of all sentences is impossible. • Humans are genetically endowed with a system of linguistic rules which enables them to produce language. • Our linguistic knowledge includes knowledge of the rules for forming sentences. • These rules also permit us to make grammaticality judgments to determine which strings of words are grammatical and which are not. • The rules are finite (limited) in number so that they can be stored in the human brain. • These limited rules permit us to understand and produce an infinite number of sentences. • These rules are not taught in a grammar class. They are unconscious constraints on sentence formation that are learned when language is acquired in childhood. • Our ability to speak and understand, and to make judgments about the grammaticality of sentences, reveals our knowledge of the rules of our language. facebook.com/e.tutor.101 WhatsApp 0946762744 – 0982555965 1 Chomsky’s Theories Creativity of linguistic knowledge The creative aspect of language use is the ability of humans (native speakers) to produce and understand new utterances never heard before. According to Chomsky, the ability to acquire language is genetically-endowed. All humans are born with a set of rules (principles and parameters) which govern language production. Input The input that the child is exposed to is called the primary linguistic data (PLD). It is the language the child receives from his environment. The input determines the language that the child acquires. The input activates the unconscious rules and the acquisition process starts. Humans learn language through a genetically endowed language acquisition device (LAD). When children are exposed to the input (PLD), it triggers the LAD and the acquisition process begins. The poverty of stimulus (the logical problem of language acquisition) The mismatch between the limited input and the unlimited output gives rise to what is known as the poverty of the stimulus. Children can produce an infinite number of utterances that they have never heard before despite the limited input. Competence and performance • Competence is the native speaker’s abstract (ideal) knowledge of his language. It is perfect and not liable to mistakes. Competence is the abstract and unconscious linguistic knowledge. It forms the actual rules of language. • Performance is the actual use of linguistic knowledge in speech production and comprehension. Performance is prone to mistakes. It is not always a reflection of competence; even native speakers commit slips of the tongue. Universal Grammar (UG) / Principles and Parameters • Universal grammar is part of the inbuilt system that enables humans to acquire language. • Universal grammar is part of the human genetically (biologically) endowed language faculty. • This innate system of universal grammar depends on input to be activated (triggered). • All languages are based on the same pattern, which is Universal Grammar. • UG includes invariant principles across languages, as well as parameters which allow for variation from language to language. • Principles are the rules and constraints shared among all languages. • Parameters are the variations of these rules among languages, and they account for the differences between languages. For example, every phrase has a head; this is a principle. Head-direction is a parameter that has two values: head-initial or head-final. In head-initial languages, such as English, the head precedes its complement while in head-final languages the head follows its complement. Certain properties of language are too abstract, subtle and complex to be acquired without assuming some innate constraints on grammars and grammar acquisition, for example, the overt pronoun constraint. Overt Pronoun Constraint • Languages differ in the phonetic realization of subject pronouns. Subject pronouns can be overt or covert. In English pronouns are always overt, but in Spanish they may be overt or covert. • Languages that allow the pronoun to be overt or covert are called pro-drop languages (or nullsubject languages). However, there are certain restrictions; subject pronouns cannot be dropped in every sentence. These restrictions (constraints) are related to binding or what the pronoun refers to. 2 • In English, the subject pronoun is always overt, and it can have more than one interpretation regarding its reference. Within the sentence, it can refer to a noun, a quantifying expression such as everyone, or a wh-word such as who. Mary thinks that she will win. Everyone thinks that she will win. Who thinks that she will win. • In Spanish, which is a pro-drop language, the subject pronoun can be either overt or covert, but there are certain restrictions on dropping the pronoun. The following sentences are grammatical: • The pronoun is covert (null pronoun); it refers to the noun “John” John cree que _ es inteligente. John believes that (he) is intelligent • The pronoun is covert (null pronoun); it refers to the quantifying expression. Nadie cree que _ es inteligente. Nobody believes that (he) is intelligent • The pronoun is overt, it can refer to the noun “John” John cree que el es inteligente. John believes that he is intelligent • However, in Spanish, an overt pronoun cannot refer to a quantifying expression. So the following sentence is ungrammatical: *Nadie cree que el es inteligente. Nobody believes that he is intelligent The universal principle that underlies these sentences is the overt pronoun constraint. It states that overt pronouns in all languages cannot receive a bound variable interpretation, in other words, overt pronouns cannot have a quantifying expression or a wh-word as an antecedent in situations where a null pronoun is allowed. These examples show that it is too complicated for children to know these subtle rules from the input alone. The input is insufficient; the input underdetermines the output. This proves the existence of an innate mental faculty that enables native speakers to acquire such complex and infrequent structures unconsciously and easily. This shows that the slightest input is enough to trigger (activate) the language faculty. Grammar Descriptive grammar • The linguist's descriptive grammar is an attempt at a formal, explicit description of the native speakers' grammar. • Descriptive grammars describe the internalized, unconscious set of rules of a language. • The linguist's description must be a true model of the native speakers' linguistic capacity. A successful description of the grammar must agree with the native speakers' intuition. • Descriptive grammar describes the speakers' linguistic competence. It describes the native speaker's internalized mental grammar. • Descriptive grammar does not tell speakers how they should speak; it describes their basic linguistic knowledge. It explains how it is possible to speak and understand, and it tells what native speakers know about the sounds, words, phrases, and sentences of their language. Prescriptive grammar prescribes rather than describes the rules of grammar. Purist grammarians believe that language change is corruption; language for them must be static and constant. They believe that there are certain correct forms that all educated people should use in speaking and writing. For example, the following sentences are considered ungrammatical because of prescriptive rules: • I don't have none. Two negatives make a positive, and therefore one should say “I don't have any.” • You was wrong about that. Even when “you” is singular it should be followed by the plural “were”. • Mathilda is older than me. “I” not “me” should follow “than” in comparative constructions. facebook.com/e.tutor.101 WhatsApp 0946762744 – 0982555965 3 Purists failures (How did prescriptive grammarians go wrong?) • Prescriptivists (Purists) fail to recognize that language is dynamic and constantly changing. • They should be more concerned about the thinking of the speakers than about the language that they use. • All languages and dialects are rule-governed, and what is grammatical in one language may be ungrammatical in another language. • No language or dialect is superior or inferior to another, linguistically speaking. Teaching grammar • Teaching grammar is a set of language rules written to help speakers learn a foreign language. Teaching grammars are used in school to fulfill language requirements. • Teaching grammars state explicitly the rules of the language, list the words and their pronunciations, and aid in learning a new language. • Teaching grammars assume that the student already knows one language and compares the grammar of the target language with the grammar of the native language. • Teaching grammars might be considered prescriptive because they attempt to teach the student what is or is not grammatical in the new language. However, their aim is different from prescriptive grammars that attempt to change the rules or usage of a language already learned. Morphology Morphology is the study of the internal structure of words and the rules of word formation. Mental lexicon Inside the human brain there is a mental dictionary called the lexicon. The mental lexicon includes information regarding a word's meaning, pronunciation, spelling, grammatical categories, and so on. Content words and function words Content words Content words include nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Content words denote concepts and ideas, and they have a lexical meaning. Content words are called open class words because we can add new words to these classes, for example: download, byte, email, google, steganography. Different languages may express the same concept using words of different grammatical classes. Function words Function words include conjunctions, prepositions, articles, auxiliaries, and pronouns. Function words do not have a clear lexical meaning, but they have a grammatical function. Function words are called closed class words. The brain treats content and function words differently There is psychological and neurological evidence to support this claim. • Some brain-damaged patients have greater difficulty in using or understanding function words than they do with content words. Other patients do the opposite. • The two classes of words appear differently in slips of the tongue. For example, a speaker may switch content words but not function words. • There is also evidence from language acquisition. In the early stages of development, children often omit function words from their speech. Morphemes A morpheme is the minimal (smallest) unit of linguistic meaning or grammatical function. It is an arbitrary union of a sound and a meaning that cannot be further analyzed. For example, the word cats consists of the content morpheme cat and the function morpheme -s. The word undesirable consists of three morphemes: un + desire + able. The word study consists of only one morpheme. 4 Morphemes vs Morphs • A morpheme is an abstract entity. A morph is an actual physical entity. • There is usually a one-to-one matching between morphemes and morphs: unhappy has two morphs and two morphemes (un + happy), played has two morphs and two morphemes (play + past tense ed), cats has two morphs and two morphemes (cat + plural s). However caught has one morph but two morphemes (catch + past tense ed), went has one morph but two morphemes (go + past tense ed). mice has one morph but two morphemes (mouse + plural s). • A morph may stand for one or more morphemes: The morph /s/ marks the third person, singular number, present tense of the verb as in sits. It also marks the plural as in cats, and it also marks possession as in book's title. • A morpheme may stand for one or more morphs, for example: The past tense morpheme -ed can be realized (pronounced) as /t/ in thanked, /d/ in played, /ɪd/ in faded. The plural morpheme -s can be realized (pronounced) as /s/ in cats, /z/ in bags, /ɪz/ in roses. Morphological knowledge Words have internal structure, which is rule-governed. Morphological knowledge has two components: knowledge of the individual morphemes and knowledge of the rules that combine them. For example, uneaten is a word in English, but *eatenun is not a word. Morpheme vs Word: Bound and free morphemes Free morphemes (free roots) can stand alone and constitute words by themselves, like star, hope, and man. Bound morphemes are never words by themselves, for example: un-, -ly, -ed; they must be attached to other morphemes. These include bound roots (such as the Latinate morphemes mit and ceive) and affixes. Affixes: • Prefixes precede other morphemes, such as pre-, un-, re-. • Suffixes follow other morphemes, such as -ing, -er -ist, -ly. • Infixes are inserted into other morphemes, for example: abso-bloody-lutely • Circumfixes (discontinuous morphemes) are attached to another morpheme both initially and finally, for example: the past participle geliebt of the German verb lieb. There are no circumfixes in English. Cross-linguistic differences • Languages may differ in how they use their morphemes. A morpheme that is a prefix in one language may be a suffix or infix in another language. In English, scientist is derived from science by adding a suffix while in Arabic it is derived using an infix. Problems in the definition of morphemes A morpheme is defined as the basic element of meaning, an arbitrary union of a sound and a meaning that cannot be further analyzed. However, this definition has some problems: • Morphemes sometimes do not have an actual (phonetic) realization, for example: the past tense marker (-ed) is not phonetically realized in the past tense verb cut. • Some morphemes have no meaning in isolation but acquire meaning only in combination with other specific morphemes, for example: cran-, huckle-, and boysen- have meaning only when combined with berry to form the words cranberry, huckleberry, and boysenberry. • Some morphemes occur only in a single word combined with another morpheme. For example: luke- occurs only in the word lukewarm. facebook.com/e.tutor.101 WhatsApp 0946762744 – 0982555965 5 • Some morphemes occur in many words, but they don't have a constant meaning from one word to another. For example, the words receive, conceive, and deceive share the root -ceive, and the words permit, commit, and admit share the root -mit. For the original Latin speakers the morpheme ceive means "to send," and mit means "to seize." However, these Latinate morphemes have no independent meaning in English. Their meaning depends on the word in which they occur. • There are words in which the root morphemes never occur alone, but always with a specific prefix, for example: inept, ungainly, discern, nonplussed. These roots are not words: *ept, *gainly, *cern, *plussed. Similarly, *holster, *hearted, *landish are not free morphemes; they cannot stand alone, but they are found in the words upholster, downhearted, and outlandish. • Identical morphemes may not be related. For example, the morpheme straw in strawberry is not the same morpheme as that found in “straw hat”, and the morpheme goose in gooseberry is not related to goose (the bird). Another example is blackberry, which may be blue or red. • The meaning of a morpheme must be constant. Morphemes which are pronounced identically but have different meanings represent different morphemes. For example, the agentive morpheme -er in words like singer and worker is different from the comparative morpheme -er in nicer and prettier. The same sounds may occur in another word and not represent a separate morpheme. The final er in father is not a morpheme. Morphology يوجد تتمة لقسم:ملحظة Semantics Semantics is the study of the linguistic meaning of morphemes, words, phrases, and sentences. Lexical semantics is concerned with the meanings of words and the meaning relations between words. Phrasal and sentential semantics are concerned with the meanings of syntactic units larger than the word. Lexical Semantics Semantic Properties (Semantic Features) The meaning of the content words and some of the function words can partially be specified by semantic properties. The same semantic property may be part of the meaning of many words: "female" is a semantic property that helps to define tigress, hen, mare, aunt, widow, and woman. The words father, uncle, and bachelor have the properties "male" and "adult," but father also has the property "parent". Evidence for semantic properties (semantic features) Semantic properties are not directly observable, and they must be inferred from linguistic evidence. One source of evidence is the speech errors, or slips of the tongue. For example, the intended utterance “Mary was young” might be produced as “Mary was early.” The incorrectly substituted word is not random; it shares a semantic property with the intended word: young and early are related to "time". Semantic properties (semantic features) vs Nonlinguistic properties The semantic properties that describe the linguistic meaning of a word should not be confused with other nonlinguistic properties, such as physical properties. Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen, but such knowledge is not part of a word's meaning. Semantic properties and the lexicon (Semantic classes) The lexicon (mental dictionary) is the part of the grammar that contains the unconscious knowledge that speakers have about individual words and morphemes, including semantic properties. Words that share a semantic property are in a semantic class, for example, the semantic class of "female" words includes woman, mother, bride, maiden. Semantic classes may intersect, such as the class of words 6 with the properties "female" and "young," for example girl, filly. In some cases, the presence of one semantic property can be inferred from the presence or absence of another. For example, words with the property "human" also have the property "animate," and lack the property "equine." Semantic features • Semantic features are a formal or notational device that indicates the presence or absence of semantic properties by pluses and minuses, for example: woman has the features [+female] [+human] [-young] girl has the features [+female] [+human] [+young] father has the features [+male] [+human] [+parent] ewe, cow, mare has the features [+female] [-human] [-young] ram, bull, and stallion share the features [+male] [-female] [+adult] [-human] lamb, calf, foal share the features [+young] [-adult] [+animal] [-human] • Intersecting classes share some features; members of the class of words referring to human females are marked [+human] and [+female]. • The difference between nouns may be represented by the use of the feature [+count] or [-count]. Countable nouns such as dog and potato are [+count] Mass nouns such as rice, water, and milk are [-count]. • The same semantic property may occur in words of different categories. The semantic property "female" (the semantic feature [+female]) is part of the meaning of the noun mother, the verb breast-feed, and the adjective pregnant. • In some languages, semantic features are reflected in morphology. In English, the suffix -let, as in booklet, appears in words that have the feature [+small]. Semantic features may be inferred from context The words swim, pour, drink, and droplet are all used with items relating to the property "liquid." These words have the semantic feature [+liquid]. So in the sentence “He saw a bug swimming in goop," it is obvious that goop has the semantic feature [+liquid]. Advantages (attractions) of semantic properties • Semantic properties show the similarities between words like ram and bull, and the differences between ram and ewe. • Semantic properties provide the basis for synonyms, antonyms, and other word relations. For example, the antonyms old and young are related to “age”. Disadvantages (problems) of semantic properties • Sometimes a great number of features is required to differentiate between two words. For example, mug and cup can both be described using the features [+inanimate], [+object], and [+container]. Another example is couch and sofa. • Sometimes there are no common features between some terms. For example, there is no semantic feature common to all sorts of games, such as card-games, ball-games, and Olympic games. • Some words have fuzzy boundaries such as color terms. • Classes have internal structure, with some members being better examples than others. For example, penguins and ostriches are less typical examples of birds than sparrows. facebook.com/e.tutor.101 WhatsApp 0946762744 – 0982555965 7 Relations between words Relations between words vary according to meaning, spelling, and pronunciation. Homonyms (homophones) are words that are pronounced the same but may or may not be spelled the same and have different meanings, for example: to, too, and two; tale and tail; bat (the animal) and bat (for hitting baseballs). Other examples include: ad, add; aid, aide; air, heir; aisle, isle; bald, bawled; die, dye; elicit, illicit; fair, fare; mail, male. Homonyms can create ambiguity. A word or a sentence is ambiguous if it can be interpreted in more than one way, for example “I'll meet you by the bank”. Homographs are words that are spelled the same, but have different meanings, for example: dove (past tense of dive or the bird), bear (verb or the animal), object (verb/noun). When homonyms are spelled the same, they are also homographs, for example: the noun bear and the verb bear. Not all homonyms are homographs, for example: bear and bare. Heteronyms are words that are spelled the same, but pronounced differently, and have different meanings, for example: dove (the bird) and dove (the past tense of dive). Other examples include bass, bow, lead, minute, wind, object, record, and desert. All heteronyms are also homographs. Polysemy occurs when a word has multiple meanings that are related conceptually or historically. For example, the verb bear has the meanings "to tolerate," "to carry," and "to support." Other examples include the words arm (“upper limb” or “weapon”), once (“one time” or “as soon as”), pupil (“schoolchild” or “the opening in the eye”), face (“face of a person”, "face of a building”), and solution ("the answer to a problem" or "liquid") Synonyms are words that have the same or nearly the same meaning, for example: sofa and couch, horse and steed, careful and assiduous, pail and bucket. There are no perfect synonyms; no two words ever have exactly the same meaning. The degree of semantic similarity between words depends largely on the number of semantic properties they share. Sofa and couch refer to the same type of object and share most of their semantic properties. • Partial synonymy occurs when a polysemous word shares one of its meanings with another word. For example, mature and ripe are synonyms when describing fruit, but only mature can describe animals. Deep and profound mean the same when applied to thought, but only deep can describe water. • Words that are ordinarily opposites can mean the same thing in certain contexts; a good scare is the same as a bad scare and a fat chance is the same as a slim chance. • A word with a positive meaning in one form, such as the adjective perfect, when used adverbially, undergoes a weakening effect, so "perfectly good" means "adequate." Similarly, “quite good” means “acceptable.” • When synonyms occur in identical sentences, the sentences are paraphrases; that is, they have the same meaning, such as "She forgot her handbag" and "She forgot her purse." Antonyms are words that are opposite in meaning. Words that are antonyms share all semantic properties except one. There are several kinds of antonymy: • A complementary pair is two antonyms related in such a way that the negation of one is the meaning of the other, such as alive/dead, present/absent, awake/asleep, open/closed. • A gradable pair is two antonyms related in such a way that more of one is less of the other, such as big/small hot/cold fast/slow happy/sad. 8 ▪ The meaning of adjectives in gradable pairs is related to the object they modify. They do not provide an absolute scale. A "small house" is much bigger than a "large mouse." ▪ With gradable pairs, the negative of one word is not synonymous with the other. For example, someone who is not happy is not necessarily sad. ▪ With certain pairs of gradable antonyms, one is marked and the other is unmarked. The unmarked member is the one used in questions of degree like "How high is the mountain?" High is the unmarked member of high / low. Similarly tall is the unmarked member of tall / short, and fast is the unmarked member of fast / slow. • Relational opposites are a pair of antonyms in which one describes a relationship between two objects and the other describes the same relationship when the two objects are reversed, for example: parent/child, teacher/pupil, give/receive buy/sell. Pairs of words ending in -er and, -ee are usually relational opposites. Relational opposites display symmetry in their meaning. If Mary is Bill's employer, then Bill is Mary's employee. • Autoantonyms are words that have two opposite meanings. They are their own antonyms, such as cleave "to split apart" or "to cling together" and dust "to remove something" or "to spread something," as in “dusting furniture” or “dusting crops”. • Antonymic pairs are pronounced the same but spelled differently and have opposite meanings, for example: raise and raze. • Formation of Antonyms In English there are a number of ways to form antonyms. Prefixes may be used to form negative words morphologically: mis- as in misbehave, dis- as in displease, non- as in nonentity, and in- as in intolerant. Antiautonyms are an exceptional case, they have the same or nearly the same meaning with or without adding prefixes, for example loosen and unloosen; flammable and inflammable; valuable and invaluable. Hyponyms are words whose meanings are specific instances of a more general word. The words red, white, and blue are "color" words. They have the feature [+color] indicating a class to which they all belong. Red is a hyponym of color, and color is a superordinate of red (or color is a hypernym of red). Similarly tiger, leopard, and lynx are hyponyms because they have the feature [+feline]; their superordinate is feline. Sometimes no single word in the language encompasses a set of hyponyms. For example, clarinet, guitar, piano, and violin are hyponyms because they are musical instruments, but there isn't a single word meaning "musical instrument." Metonyms: A metonym is a word substituted for another word or expression with which it is closely associated, such as the use of crown for king, brass to refer to military leaders, Kremlin for the Russian government, and Washington for the American government. In sports, ice is used for hockey, turf for horse-racing, gridiron for football, and diamond for baseball. In England, Scotland Yard refers to the police department. Retronyms: A retronym is an expression that was redundant, but which societal or technological changes have made nonredundant, for example: Day baseball, silent movie, surface mail, and whole milk. Semantics يوجد تتمة لقسم:ملحظة facebook.com/e.tutor.101 WhatsApp 0946762744 – 0982555965 9