THE MINISTRY OF HIGHER AND SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

NAMANGAN STATE UNIVERSITY

ENGLISH FACULTY

ENGLISH LEXICOLOGY DEPARTMENT

COURSE PAPER

The description of truth and issue in

Shakespeare’s histories

Written by the student of the 2nd course, 312 group

Juraboyeva Diyora

Scientific superviser:

Dadaboyeva lazokat

NAMANGAN 2021

CONTENTS

Introduction……………………………………………………………….....…....3

Chapter I. The lifestyle and works of William Shakespeare

1.1.William Shakespeare biography.............................................................5

1.2.William Shakespeare as an English dramatist, poet and actor .................7

Chapter II. William Shakespeare’s histories as the greatest literature of all

time

2.1.Characteristics of Shakespeare’s history plays……………………………….18

2.2. The description of truth and issue in Shakespeare's histories……………….21

Conclusion………………………………………………......................................31

The list of used literature…………………………………………………….....34

Introduction

Our President Shavkat Mirziyoyev said : ,, Every time I communicate with

young people, you inspire me, fill my heart with joy. I know very well that each of

2

you is eager to serve our Motherland and people. I value you immensely as the

greatest wealth, priceless treasure of Uzbekistan”.

“Whatever reforms we carry out in our country, first of all, we rely on young people

like you, on your energy and determination. As you all know, today we set ourselves

big goals. We began to lay the foundations for the Third Renaissance in Uzbekistan.

We consider the support of the family, preschool, school and higher education,

institutions of science and culture as the most important basis for the future

Renaissance. Therefore, we are carrying out fundamental reforms in these spheres. I

am sure that our selfless and patriotic youth, whom you represent, will take an

active part and make a worthy contribution to the historical process of creating a

new foundation for the development of our country”.

Undoubtedly, as the best examples for our Prezident’s speech mentioned above

nowadays there are many opportunities for the youth of Uzbekistan to show their

full capacity in any field. Using these opportunities wisely, I am also trying to learn

more languages, especially English and to do research on my course paper in my

speciality.

The given course paper is dedicated to the study of one of the best representatives

of English literature William Shakespeare’s works , particularly his history plays.

The course paper mostly focuses on and discusses how much Shakespeare’s

histories are historically accurate and what kind of issues were described in them.

The aim of this course paper analyzes what makes Shakespeare history plays

according to this general aim there put forward the following particular tasks:

1. to define sources of Shakespeare’s history plays;

2. to describe common features of Shakespeare histories;

3. to analyze whether Shakespeare histories were accurate;

4. to study the significance of histories in English literature.

The theoretical significance of this course paper is that, in recent years the

role of literature as a basic component and source of authentic texts of the language

curriculum rather than an ultimate aim of English instruction has been gaining

3

momentum. Many teachers consider the use of literature in language teaching as an

interesting and worthy concern(Sage 1987:1). Therefore the theoretical position

can be used in scientific works besides, that they may be used delivering lectures

on English literature. The practical value of the course paper is that, the practical

results and conclusion can be used in seminars on English literature.

The structure of this course paper is as follows: Introduction, main part,

conclusion and bibliography.

Introduction deals with the description of the structure of a course paper.

The first paragraph deals with William Shakespeare short biography.

The second paragraph deals with Shakespeare’s works.

In the third paragraph we discuss about characteristics of Shakespeare history

plays.

In the forth paragraph we analyze the description of truth and issue in Shakespeare

histories.

Introduction establishes the purpose, the tasks, novelty, the methods used in

the investigation, practical and theoretical significance of the work and explains

the reasons of choosing the theme for studying.

4

Chapter I. The lifestyle and works of William Shakespeare

1.1.William Shakespeare biography

Studying English literature opens up a world of inspiration and

creativity, while also developing skills that are essential for today's global

environment. It is a chance to discover how literature makes sense of the

world through stories, poems, novels and plays. It is also a chance to

sharpen your own ability to write, read, analyze and persuade.

As we know, English literature and its representatives are always focus of the

world literature. There is no one who knows any English writer or poet and at least

their works. Some of the name of English representatives have already become

well-known as our national Uzbek literature representatives. One of them is

undoubtedly , William Shakespeare.

William Shakespeare was an English poet, playwright, and actor. He

was born on 26 April 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. His father was a

successful local businessman and his mother was the daughter of a

landowner. He is often called England's national poet and nicknamed the

Bard of Avo.

Records survive relating to William Shakespeare’s family that offer an

understanding of the context of Shakespeare's early life and the lives of his family

members. John Shakespeare married Mary Arden, and together they had eight

children. John and Mary lost two daughters as infants, so William became their

eldest child. John Shakespeare worked as a glove-maker, but he also became an

important figure in the town of Stratford by fulfilling civic positions. His elevated

status meant that he was even more likely to have sent his children, including

William, to the local grammar school.

William Shakespeare would have lived with his family in their house on

Henley Street until he turned eighteen. When he was eighteen, Shakespeare

married Anne Hathaway, who was twenty-six. She was eight years older than

him.It was a rushed marriage because Anne was already pregnant at the time of the

5

ceremony. Together they had three children. Their first daughter, Susanna, was

born

six

months

after

the

wedding

and

was

later

followed

by

twins Hamnet and Judith. Hamnet died when he was just 11 years old.

Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway at the age of 18. She was eight years

older. After his marriage information about his life became very rare. But he is

thought to have spent most of his time in London writing and performing in his

plays. Between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor,

writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain's Men,

later known as the King's Men.

Shakespeare’s success in the London theatres made him considerably

wealthy, and by 1597 he was able to purchase New Place, the largest house in the

borough of Stratford-upon-Avon. Although his professional career was spent in

London, he maintained close links with his native town.

Recent archaeological evidence discovered on the site of Shakespeare’s New

Place shows that Shakespeare was only ever an intermittent lodger in London. This

suggests he divided his time between Stratford and London (a two or three-day

commute). In his later years, he may have spent more time in Stratford-upon-Avon

than scholars previously thought.

Whatever the answer, by 1592 Shakespeare had begun working as an actor,

penned several plays and spent enough time in London to write about To the

dismay of his biographers, Shakespeare disappears from the historical record

between 1585, when his twins’ baptism was recorded, and 1592, when the

playwright Robert Greene denounced him in a pamphlet as an “upstart crow”

(evidence that he had already made a name for himself on the London stage). What

did the newly married father and future literary icon do during those seven “lost”

years? Historians have speculated that he worked as a schoolteacher, studied law,

traveled across continental Europe or joined an acting troupe that was passing

6

through Stratford. According to one 17th-century account, he fled his hometown

after poaching deer from a local politician’s estate.1

its geography, culture and diverse personalities with great authority. Even his

earliest works evince knowledge of European affairs and foreign countries,

familiarity with the royal court and general erudition that might seem unattainable

to a young man raised in the provinces by parents who were probably illiterate. For

this reason, some theorists have suggested that one or several authors wishing to

conceal their true identity used the person of William Shakespeare as a front.

(Most scholars and literary historians dismiss this hypothesis, although many

suspect Shakespeare sometimes collaborated with other playwrights.)

On his father's death in 1601, William Shakespeare inherited the old family home

in Henley Street part of which was then leased to tenants. Further property

investments in Stratford followed, including the purchase of 107 acres of land in

1602.

Shakespeare died in Stratford-upon-Avon on 23 April 1616 at the age of 52. He is

buried in the sanctuary of the parish church, Holy Trinity. Shakespeare left the

bulk of his great estate in his will to his elder daughter, Susanna.

1.2.William Shakespeare as an English dramatist, poet and actor.

As we know, William Shakespeare was not only famous for as a playwright,

but also as a poet and skillful actor. During his lifetime 39 plays, 154 sonnets, three

long narrative poems and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship.

No original manuscripts of Shakespeare's plays are known to exist today. It is

actually thanks to a group of actors from Shakespeare's company that we have

about half of the plays at all. They collected them for publication after Shakespeare

died, preserving the plays. These writings were brought together in what is known

as the First Folio ('Folio' refers to the size of the paper used). It contained 36 of his

plays, but none of his poetry.

1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakespearean_history

7

Shakespeare’s legacy is as rich and diverse as his work; his plays have

spawned countless adaptations across multiple genres and cultures. His plays have

had an enduring presence on stage and film. His writings have been compiled in

various iterations of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, which include

all of his plays, sonnets, and other poems. William Shakespeare continues to be

one of the most important literary figures of the English language.

Shakespeare’s plays are divided into three genres: comedies, tragedies and

histories. We will discuss them one by one.

We don't know exactly when Shakespeare started writing plays, but they were

probably being performed in London by 1592, and he's likely to have written his

final plays just a couple of years before his death in 1616.

Shakespeare's plays portray recognisable people in situations that we can all relate

to - including love, marriage, death, mourning, guilt, the need to make difficult

choices, separation, reunion and reconciliation. They do so with great humanity,

tolerance, and wisdom. They help us to understand what it is to be human, and to

cope with the problems of being so.

The list of Comedies included Measure for Measure and The Merchant of

Venice, plays that modern audiences and readers have not found particularly

‘comic’. Also included were two late plays, The Tempest and The Winter’s Tale,

that critics often now classify as ‘Romances’. If we ask ourselves what these four

plays have in common with those such as As You Like It or Twelfth Night, which

we are used to calling ‘comedies’, the answer gives us a clue to the meaning of

‘comedy’ for many of Shakespeare’s educated contemporaries. All of them end in

marriage (or at least betrothal)

In Shakespearean comedies much that is funny arises from the

misconceptions of lovers. In Much Ado about Nothing the friends of Benedick,

whom we have seen mocking Beatrice and scorning love, arrange for him to

overhear them talking about how desperately Beatrice in fact loves him. The trick

is enjoyably justified when he next meets Beatrice and determinedly interprets her

8

rudeness as concealed affection. Yet the trick takes us further. Once Beatrice has

been deceived by her friends in similar fashion, these two characters, who both

once disdained the follies of courtship, are on the path to love and marriage. All

this deception would not be amusing if we could not feel confident that it will

produce a happy resolution In the play’s sub-plot, the deception of Claudio by Don

John indicates how a deceived lover might, in another kind of play, be on his way

to creating a tragedy. Interwoven with the plot of Benedick and Beatrice’s love

story is the drama of so-called ‘love’ (Claudio for Hero) turned into murderous

hate. However satisfying the former courtship, it is shadowed by the vengefulness

of the untrusting Claudio.

For the most part, Shakespeare’s comedies rely on benign misunderstanding

and deception. They therefore put a premium on dramatic irony, where we know

better than the perplexed lovers. An outstanding example is A Midsummer Night’s

Dream, where we understand the magic of the love potion, mistakenly applied by

Puck to Lysander’s eyes, and can relish not only the love talk he spouts to Helena,

but her befuddlement. When Puck, in an effort to remedy his mistake, squeezes the

juice onto Demetrius’s eyes and he, waking to see Helena, also pours forth

professions of love for her, we hear how easily and eloquently men can think they

love one woman or another. Hermia, who thought that Lysander loved her, is

furiously jealous while Helena is convinced that there is a conspiracy to deceive

her. We laugh at their perplexity because we know that the magic that produced it

will eventually resolve it and ensure a happy ending. The lovers will return from

the forest, that place of confusion and transgression, to the institution of marriage.

Comedy was traditionally a ‘lower’ genre than tragedy or history, and so these

comedies by Shakespeare’s contemporaries justified themselves by their satirical

ambitions. Satire was a higher genre than other kinds of comedy, commended by

classical authors as morally improving. City comedies had a moral purpose: they

mocked current follies and vices. Shakespeare was little interested in topical satire.

Yet there is some evidence that the rules and conventions governing comedy were

9

loose in Shakespeare’s day. The title pages of the various quarto editions of

Shakespeare’s plays indicate that generic categories were not hard and fast. The

quarto edition of Love’s Labour’s Lost (1598) announces it as ‘A Pleasant

Conceited Comedy’ and the quarto Taming of the Shrew declares it to be a ‘wittie

and pleasant comedie’. Yet the title page of The Merchant of Venice (1600) calls it

‘The most excellent Historie of the Merchant of Venice’.

These title pages – almost certainly composed by booksellers rather than the

playwright – tell us about the appeal of word play and contests of wit to

Shakespeare’s first audiences. To us The Taming of the Shrew might seem a play

about sexual politics, but it was probably initially admired for being ‘wittie’: that

is, for featuring two leading characters who were skilled in verbal antagonism.

Verbal humour, often dependent on puns and allusions, is sometimes difficult to

translate on the modern stage, but it was essential to Elizabethan and Jacobean

expectations of comedy. One of Shakespeare’s most popular comic characters, Sir

John Falstaff, arrived on the stage in history plays but was celebrated for his verbal

dexterity. As he announces, ‘I am not only witty in myself, but the cause that wit is

in other men’ (Henry IV, Part 2, 1.2.9–10). The quarto edition of Henry IV, Part

1 (1598) was advertised as including ‘the humorous conceits of Sir John Falstaffe’.

Subsequently, the title page of the quarto edition of The Merry Wives of

Windsor (1602) described it as ‘A most pleasant and excellent Conceited comedie,

of Sir John Falstaffe, and the merrie Wives of Windsor’.2

Shakespeare comedies (or rather the plays of Shakespeare that are usually

categorised as comedies) are generally identifiable as plays full of fun, irony and

dazzling wordplay. They also abound in disguises and mistaken identities, with

very convoluted plots that are difficult to follow with very contrived endings.

Any attempt at describing Shakespeare’s comedy plays as a cohesive group can’t

go beyond that superficial outline. The highly contrived endings of most

2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakespearean_history

10

Shakespeare comedies are the clue to what these plays – all very different – are

about.

Take The Merchant of Venice for example – it has the love and relationship

element. As is often the case, there are two couples. One of the women is disguised

as a man through most of the text – typical of Shakespearean comedy – but the

other is in a very unpleasant situation – a young Jewess seduced away from her

father by a shallow, rather dull young Christian. The play ends with the lovers all

together, as usual, celebrating their love and the way things have turned out well

for their group. That resolution has come about by completely destroying a man’s

life.

The Jew, Shylock is a man who has made a mistake and been forced to pay

dearly for it by losing everything he values, including his religious freedom. It is

almost like two plays – a comic structure with a personal tragedy embedded in it.

The ‘comedy’ is a frame to heighten the effect of the tragic elements, which creates

something very deep and dark.

Twelfth Night is similar – the humiliation of a man the in-group doesn’t like.

As in The Merchant of Venice, his suffering is simply shrugged off in the highly

contrived comic ending.

Not one of Shakespearean comedy, no matter how full of life and love and

laughter and joy, it may be, is without a darkness at its heart. Much Ado About

Nothing , like Antony and Cleopatra (a ‘tragedy’ with a comic structure), is a

miracle of creative writing. Shakespeare seamlessly joins an ancient mythological

love story and a modern invented one, weaving them together into a very funny

drama in which light and dark chase each other around like clouds and sunshine on

a windy day, and the play threatens to fall into an abyss at any moment and

emerges from that danger in a highly contrived ending once again.

Like the ‘tragedies’ Shakespeare comedies defy categorisation. They all

draw our attention to a range of human experience with all its sadness, joy,

11

poignancy, tragedy, comedy, darkness and lightness. Below are all of the plays

generally regarded as Shakespeare comedy plays.

COMEDIES

o

All’s Well That Ends Well

o

As You Like It

o

The Comedy of Errors

o

Love's Labour's Lost

o

Measure for Measure

o

The Merchant of Venice

o

The Merry Wives of Windsor

o

A Midsummer Night's Dream

o

Much Ado About Nothing

o

The Taming of the Shrew

o

The Tempest

o

Twelfth Night

o

The Two Gentlemen of Verona

o

The Winter's Tale

The main reason why Shakespeare enjoyed setting his comedies in almost

paradise-like locations is because, more often than not, things tend to go wrong in

these plays. Mistakes are made, complications are rife, misunderstandings always

arise, so when audiences see how characters living in paradise engage in mishaps

too, it only underscores the comedy. After all, if things can go awry in seemingly

perfect worlds, it becomes strangely comforting to those of us who live in the real

world. This is why many find Shakespeare’s comedies so resonant today, as it

proves that if things seem too good to be true, they probably are.

Common Features of Shakespeare's Tragedies

Shakespeare is perhaps most famous for his tragedies—indeed, many

consider "Hamlet" to be the best play ever written. Other tragedies include "Romeo

12

and Juliet," "Macbeth" and "King Lear," all of which are immediately

recognizable, regularly studied, and frequently performed.

In all, Shakespeare wrote 10 tragedies. However, Shakespeare's plays often

overlap in style and there is debate over which plays should be classified as

tragedy, comedy, and history. For example, "Much Ado About Nothing" is

normally classified as a comedy but follows many of the tragic conventions.

The fatal flaw: Shakespeare’s tragic heroes are all fundamentally flawed. It

is this weakness that ultimately results in their downfall.

The bigger they are, the harder they fall: The Shakespeare tragedies often

focus on the fall of a nobleman. By presenting the audience with a man with

excessive wealth or power, his eventual downfall fall is all the more tragic.

External pressure: Shakespeare’s tragic heroes often fall victim to external

pressures. Fate, evil spirits, and manipulative characters all play a hand in the

hero’s downfall.

In Shakespeare's tragedies, the main protagonist generally has a flaw that leads to

his downfall. There are both internal and external struggles and often a bit of the

supernatural thrown in for good measure (and tension). Often there are passages or

characters that have the job of lightening the mood (comic relief), but the overall

tone of the piece is quite serious.

All of Shakespeare's tragedies contain at least one more of these elements:

A tragic hero

A dichotomy of good and evil

A tragic waste

Hamartia (the hero’s tragic flaw)

Issues of fate or fortune

Greed

Foul revenge

Supernatural elements

Internal and external pressures

13

The paradox of life

The Tragedies

A brief look shows that these 10 classic plays all have common themes.

1) “Antony and Cleopatra”: Antony and Cleopatra’s affair brings about the

downfall of the Egyptian pharaohs and results in Octavius Caesar becoming the

first Roman emperor. Like Romeo and Juliet, miscommunication leads to Anthony

killing himself and Cleopatra later doing the same.

2) “Coriolanus”: A successful Roman general is disliked by the “play Bienz“ of

Rome, and after losing and gaining their trust throughout the play, he is betrayed

and assassinated by Aufidius, a former foe using Coriolanus to try to take over

Rome. Aufidius felt like Coriolanus betrayed him in the end; thus he has

Coriolanus killed.

3) “Hamlet”: Prince Hamlet devotes himself to avenging his father’s murder,

committed by his uncle, Claudius. Hamlet's quest for revenge causes the deaths of

many friends and loved ones, including his own mother. In the end, Hamlet is

lured into a fight to the death with Laertes, brother of Ophelia, and is stabbed by a

poisoned blade. Hamlet is able to kill his attacker, as well as his uncle Claudius,

before dying himself.

4) “Julius Caesar”: Julius Caesar is assassinated by his most trusted friends and

advisers. They claim they fear he is becoming a tyrant, but many believe Cassius

wants to take over. Cassius is able to convince Caesar‘s best friend, Brutus, to be

one of the conspirators in the death of Cesar. Later, Brutus and Cassius lead

opposing armies into battle against each other. Seeing the futility of all they have

done, Cassius and Brutus each order their own men to kill them. Octavius then

orders Brutus be buried honorably, for he was the noblest of all Romans.

5) “King Lear”: King Lear has divided his kingdom and given Goneril and Regan,

two of his three daughters, each a part of the kingdom because the youngest

daughter (Cordelia), previously his favorite, would not sing his praises at the

dividing of the kingdom. Cordelia vanishes and goes to France with her husband,

14

the prince. Lear attempts to get his two oldest daughters to take care of him, but

neither wants anything to do with him. They treat him poorly, leading him to go

mad and wander the moors. Meanwhile, Goneril and Regan plot to overthrow each

other leading to many deaths. In the end, Cordelia returns with an army to save her

father. Goneril poisons and kills Regan and later commits suicide. Cordelia’s army

is defeated and she is put to death. Her father dies of a broken heart after seeing her

dead.

6) “Macbeth”: Due to an ill-timed prophecy from the three witches, Macbeth,

under the guidance of his ambitious wife, kills the king to take the crown for

himself. In his increasing guilt and paranoia, he kills many people he perceives are

against him. He is finally beheaded by Macduff after Macbeth had Macduff’s

entire family assassinated. The “evilness” of Macbeth and the Lady Macbeth‘s

reign comes to a bloody end.

7) “Othello”: Angry that he was overlooked for a promotion, Iago plots to

overthrow Othello by telling lies and getting Othello to cause his own downfall.

Through rumors and paranoia, Othello murders his wife, Desdemona, believing

she has cheated on him. Later, the truth comes out and Othello kills himself in his

grief. Iago is arrested and is ordered to be executed.

8) “Romeo and Juliet”: Two star-crossed lovers, who are destined to be enemies

because of the feud between their two families, fall in love. Many people try to

keep them apart, and several lose their lives. The teens decide to run away together

so that they can wed. To fool her family, Juliet sends a messenger with news of her

“death“ so they will not pursue her and Romeo. Romeo hears the rumor, believing

it to be true, and when he sees Juliet’s “corpse,“ he kills himself. Juliet wakes up

and discovers her lover dead and kills herself to be with him.

9) “Timon of Athens”: Timon is a kind, friendly Athenian nobleman who has

many friends because of his generosity. Unfortunately, that generosity eventually

causes him to go into debt. He asks his friends to help him financially, but they all

refuse. Timons invites his friends over for a banquet where he serves them only

15

water and denounces them; Timons then goes to live in a cave outside of Athens,

where he finds a stash of gold. An Athenian army general, Alcibiades, who has

been banished from Athens for other reasons, finds Timons. Timons offers

Alcibiades gold, which the general uses to bribe the army to march on Athens. A

band of pirates also visits Timons, who offers them gold to attack Athens, which

they do. Timons even sends his faithful servant away and ends up alone.

10) “Titus Andronicus”: After a successful 10-year war campaign, Titus

Andronicus is betrayed by the new emperor, Saturninus, who marries Tamora,

Queen of the Goths, and despises Titus for killing her sons and capturing her.

Titus’s remaining children are framed, murdered, or raped, and Titus is sent into

hiding. He later cooks up a revenge plot in which he kills Tamora’s remaining two

sons and causes the deaths of his daughter, Tamora, Saturninus, and himself. By

the end of the play, only four people remain alive: Lucius (Titus’s only surviving

child), young Lucius (Lucius’s son), Marcus (Titus’s brother), and Aaron the Moor

(Tamora’s former lover). Erin is put to death and Lucius becomes the new emperor

of Rome.

William Shakespeare's name is synonymous with many of the famous lines

he wrote in his plays and prose. Yet his poems are not nearly as recognizable to

many as the characters and famous monologues from his many plays.

In Shakespeare's era (1564-1616), it was not profitable but very fashionable to

write poetry. It also provided credibility to his talent as a writer and helped to

enhance his social standing. It seems writing poetry was something he greatly

enjoyed and did mainly for himself at times when he was not consumed with

writing a play. Because of their more private nature, few poems, particularly long

form poems, have been published. The two longest works that scholars agree were

written by Shakespeare are entitled Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

Both dedicated to the Honorable Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, who

seems to have acted as a sponsor and encouraging benefactor of Shakespeare's

work

for

a

16

brief

time.

Both of these poems contain dozens of stanzas and comment on the

depravity of unwanted sexual advances, showing themes throughout of guilt, lust,

and moral confusion. In Venus and Adonis, an innocent Adonis must reject the

sexual advances of Venus. Conversely in The Rape of Lucrece, the honorable and

virtuous wife Lucrece is raped a character overcome with lust, Tarquin. The

dedication to Wriothesley is much warmer in the second poem, suggesting a

deepening of their relationship and Shakespeare's appreciation of his support.

A third and shorter narrative poem, A Lover's Complaint, was printed in the first

collection of Shakespeare's sonnets. Most scholars agree now that it was also

written by Shakespeare, though that was contested for some time. The poem tells

the story of a young woman who is driven to misery by a persuasive suitor's

attempts to seduce her. It is not regarded by critics to be his finest work.

Another short poem, The Phoenix and the Turtle, despairs the death of a legendary

phoenix and his faithful turtle dove lover. It speaks to the frailty of love and

commitment

in

a

world

where

only

death

is

certain.

There are 152 short sonnets attributed to Shakespeare. Among them, the most

famous ones are Sonnet 29, Sonnet 71, and Sonnet 55. As a collection, narrative

sequence of his Sonnets speaks to Shakespeare's deep insecurity and jealousy as a

lover, his grief at separation, and his delight in sharing beautiful experiences with

his romantic counterparts. However, few scholars believe that the sequence of the

sonnets accurately depicts the order in which they were written. Because

Shakespeare seemed to write primarily for his own private audience, dating these

short jewels of literature has been next to impossible. Within the sonnets

Shakespeare seems to have two deliberate series: one describing his all consuming

lust for a married woman with a dark complexion (the Dark Lady), and one about

his confused love feelings for a handsome young man (the Fair Youth). This

dichotomy has been widely studied and debated and it remains unclear as to if the

subjects represented real people or two opposing sides to Shakespeare's own

personality.

17

Though some of Shakespeare's poetry was published without his

permission in his lifetime, in texts such as The Passionate Pilgrim, the majority of

the sonnets were published in 1609 by Thomas Thorpe. Before that time, it appears

that Shakespeare would only have shared his poetry with a very close inner-circle

of friends and loved ones. Thorpe's collection was the last of Shakespeare's nondramatic work to be printed before his death. Critics have praised the sonnets as

being profoundly intimate and meditating on the values of love, lust, procreation,

and death. Nowaday, Shakespeare is ranked as all-time most popular English poets

on history, along with Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and Walt Whitman.

Chapter II. William Shakespeare’s histories as the greatest literature

of all time

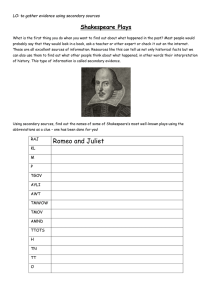

2.1.Characteristics of Shakespeare’s history plays

Just as Shakespeare’s

‘comedies’ have some dark themes and tragic

situations while the ‘tragedies’ have some high comic moments, the Shakespeare

‘history’ plays contain comedy, tragedy and everything in between. All

Shakespeare’s plays are dramas written for the entertainment of the public and

Shakeseare’s intention in writing them was just that – to entertain.

It wasn’t Shakespeare, but Shakespearian scholars, who categorised his plays into

the areas of tragedy, comedy and history Unfortunately, our appreciation of the

plays is often affected by our tendency to look at them in that limited way.

The plays normally referred to as Shakespeare history plays are the ten plays that

cover English history from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, and the 13991485 period in particular. Each historical play is named after, and focuses on, the

reigning monarch of the period. In chronological order of setting, Shakespeare’s

historical plays are:

1. King John

18

2. Richard II

3. Henry IV Part 1

4. Henry IV Part 2

5. Henry V

6. Henry VI Part 1

7. Henry VI Part 2

8. Henry VI Part III

9. Richard III

10. Henry VIII

The plays dramatise five generations of’ Medieval power struggles. For the most

part, they depict the Hundred Years War with France, from Henry V to Joan of

Arc, and the Wars of the Roses, between York and Lancaster.

We should never forget that they are works of imagination, based very loosely

on historical figures. Shakespeare was a keen reader of history and was always

looking for the dramatic impact of historical characters and events as he read.

Today we tend to think of those historical figures in the way Shakespeare

presented them.

For example, we think of Richard III as an evil man, a kind of psychopath with a

deformed body and a grudge against humanity. Historians can do whatever they

like to set the record straight but Shakespeare’s Richard seems stuck in our culture

as the real Richard III.

Henry V, nee Prince Hal, is, in our minds, the perfect model of kingship

after an education gained by indulgence in a misspent youth, and a perfect human

being, but that is only because that’s the way Shakespeare chose to present him in

the furtherance of the themes he wanted to develop and the dramatic story he

wanted to tell.

In fact, the popular perception of medieval history as seen through the rulers

of the period is pure Shakespeare. We have given ourselves entirely to

Shakespeare’s vision. What would Bolingbroke (Henry IV) mean to us today? We

19

would know nothing of him but because of Shakespeare’s plays, he is an

important, memorable and significant historical figure.

Shakespeare’s history plays are enormously appealing. Not only do they

give insight into the political processes of medieval and renaissance politics but

they also offer a glimpse of life from the top to the very bottom of society – the

royal court, the nobility, tavern life, brothels, beggars, everything. The greatest

English actual and fictional hero, Henry V, and the most notorious fictional

bounder, Falstaff, are seen in several scenes together. Not only that, but those

scenes are among the most entertaining, profound, and memorable in the whole

of English literature. That’s some achievement.

Many of Shakespeare’s plays have historical elements, but only certain plays

are categorized as true Shakespeare histories. Works like "Macbeth" and "Hamlet,"

for example, are historical in setting but are more correctly classified as

Shakespearean tragedies. The same is true for the Roman plays ("Julius Caesar,"

"Antony and Cleopatra," and "Coriolanus"), which all recall historical sources but

are not technically history plays.

Shakespeare pulled inspiration for his plays from a number of sources, but most of

the English history plays are based on Raphael Holinshed's "Chronicles."

Shakespeare was known for borrowing heavily from earlier writers, and he was not

alone in this. Holinshed's works, published in 1577 and 1587, were key references

for Shakespeare and his contemporaries, including Christopher Marlowe.

Common Features of the Shakespeare Histories

The Shakespeare histories share a number of things in common. First, most are set

in times of medieval English history. The Shakespeare histories dramatize

the Hundred Years War with France, giving us the Henry Tetralogy, "Richard II,"

"Richard III," and "King John"—many of which feature the same characters at

different ages.

20

Second, in all his histories, Shakespeare provides social commentary through his

characters and plots. Really, the history plays say more about Shakespeare’s own

time than the medieval society in which they are set.

For example, Shakespeare cast King Henry V as an everyman hero to exploit the

growing sense of patriotism in England. Yet, his depiction of this character is not

necessarily historically accurate. There's not much evidence that Henry V had the

rebellious youth that Shakespeare depicts, but the Bard wrote him that way to

make his desired commentary.3

Despite seeming to focus on the nobility, Shakespeare's history plays often offer a

view of society that cuts right across the class system. They present us with all

kinds of characters, from lowly beggars to members of the monarchy, and it is not

uncommon for characters from both ends of the social strata to play scenes

together. Most memorable is Henry V and Falstaff, who turns up in a number of

the history plays.

Shakespeare wrote 10 histories. While these plays are distinct in subject matter,

they are not in style. Unlike other plays than can be categorized into genres, the

histories all provide an equal measure of tragedy and comedy.

2.2.

THE

DESCRIPTION

OF

TRUTH

AND

ISSUE

IN

SHAKESPEARE'S HISTORIES

While we are analyzing Shakespeare history plays differen question will appear

such as were Shakespeare's Histories accurate? Shakespeare’s history plays are for

many people the defining versions of England’s medieval monarchs, but can

Shakespeare really be trusted? Is Richard III the greatest villain in history or Henry

V the embodiment of the perfect, virtuous king? To find out, we are taking a closer

look at Shakespeare’s sources, why he was writing history plays in the first place

3

Ogburn, Dorothy, and Ogburn, Charlton, This Star of England: William Shakespeare, Man of the Renaissance (New

York, 1952), pp. 709–710

21

and check three of his most famous plays to see if they are more historical fact or

historical fiction.

Not exactly. Even though they were a great inspiration for Shakespeare,

Holinshed's works were not particularly historically accurate; instead, they are

considered mostly fictional works of entertainment. However, this is only part of

the reason why you shouldn't use "Henry VIII" to study for your history test. In

writing the history plays, Shakespeare was not attempting to render an accurate

picture of the past. Rather, he was writing for the entertainment of his theater

audience and therefore molded historical events to suit their interests.

If produced in the modern-day, Shakespeare's (and Holinshed's) writings would

probably be described as "based on historical events" with a disclaimer that they

were edited for dramatic purposes.

Shakespeare was not the only playwright to look to history for inspiration and in

fact history plays were extremely popular across Elizabethan theatre. However,

the Elizabethans had a different view of how to “use” history – rather than learning

about facts and dates in a purely academic sense, history was used as a mirror to

the present as a means of amending behaviour and anticipating future events. As

such, the historical characters in Shakespeare’s plays often have a very strong

sense of their place in history. The history plays, therefore, are not intended as a

realistic representation of the medieval age but a combination of a nostalgic view

of times past intermingled with contemporary concerns.

However, a long-lasting career could not be built purely on simplistic,

throw-away yarns with some last nods to contemporary issues. This was possibly

the best informed theatrical audience in history, with around 15,000 people from a

population in London of around 200,000 going to the theatre each week and about

a third of the city’s population going each month. A company would not, like

today, perform the same play for months on end, but would instead change

performance on a daily basis, introducing some new works and reviving old

favourites. There was an almost constant pressure for new and more challenging

22

material. Shakespeare was part of a generation of playwrights pushing each other

on to write bigger and better things, with the more sophisticated and complex

tragedy Tamburlaine by Christopher Marlowe an early historical blockbuster of the

time.

Shakespeare, then, was by no means writing in isolation with his history

plays but what marks him out as a great playwright is not the choice of stories but

the way that he tells them. His lead characters are not simply two-dimensional

stereotypes used as props for exciting battles and swooning romances; they are

conflicted, they ask themselves questions, they grapple with questions of morality

and philosophy. There is something of the biographer in Shakespeare’s treatment

of the kings that goes beyond a soulless chronicle of events. It would be hard for

any historian to better encapsulate the difficulties of Henry IV than the lamentation

granted him by Shakespeare that “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”.

The first test for Shakespeare and the quality of his history is whether or not he

has done his research, and on this front Shakespeare does surprisingly well. On one

level, Shakespeare is actually rather unoriginal when it comes to his stories as they

are almost always based (in some way) on earlier texts. He did not invent the

witches in Macbeth (these first appeared as “weird sisters” in a history by Andrew

of Wyntoun) nor did he originate the story of Romeo and Juliet (originally a

narrative poem by Arthur Brooke in 1562). Indeed, he was not even the first to

write a popular play about Henry V.

The good news for Shakespeare when it comes to his history plays is that he

drew extensively from chronicles and histories. Primary among his sources was

Raphael Holinshead’s The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (the

second edition, published in 1587), which told the complete story of the three

kingdoms from their origins to the present day. This was actually the work of

multiple authors but it was an important and extremely popular work because such

a comprehensive history had not been published before for the British Isles. As

well as Holinshead, Shakespeare also made use of other histories available at the

23

time such as Polydore Vergil (author of an English history commissioned by Henry

VII) and Edward Hall’s The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of

Lancastre and Yorke, covering from 1399 and the death of Henry VIII in 1547.

These histories were far from perfect in terms of accuracy, but they were the best

sources available and Shakespeare did as much as was possible in the 1590s to

research the real history.

Perhaps the more serious charge against the reliability of Shakespeare’s

history is that his work reflects a great deal of Tudor bias. He was not just writing

for the crowds but also for those at court, including Elizabeth I and, after 1603,

James I (VI of Scotland). The history plays are full of references to people and

events at court as well as reflecting a very particular interpretation of recent history

that would not pass muster with modern historians.

One example is the celebrated comic character of Sir John Falstaff, a portly

buffoon who enjoys drinking with Prince Hal (later Henry V) in the Henry

IV plays. Originally, he was called Sir John Oldcastle, a real-life and rather more

serious man who had been friendly with a young Henry V but was a religious

radical ultimately executed for treason. He was also the ancestor of William

Brooke, the current Lord Chamberlain, who objected to his celebrated ancestor

being portrayed as a comic buffoon. Shakespeare clearly wanted a familiar name

and the link to the young Henry but had no interest in accurately depicting the real

man. Indeed, although Shakespeare did change the name from Oldcastle to

Falstaff, he also wrote another play for Falstaff called The Merry Wives of

Windsor in which there is a jealous husband who calls himself Brooke, so it seems

likely that Shakespeare was very deliberately poking fun at the Lord Chamberlain!

More serious is the accusation that he is effectively producing Tudor

propaganda. The Tudors were keen to promote the idea that from the deposition of

Richard II to the defeat of Richard III, England was a country mostly in chaos and

civil war (known as the Wars of the Roses) due to the evils of rebellion and

usurpation against a rightfully anointed king. It was, according to the Tudor view,

24

only with Henry VII’s victory at Bosworth that peace was restored. As an example

of how Shakespeare helped create a false national remembrance of this period, the

phrase “Wars of the Roses” is actually a nineteenth century term based on a scene

in Shakespeare’s Henry VI (Part 1) where the opposing sides pick which rose to

wear as emblems. In reality, the Lancastrians did not wear a red rose during the

conflict but rather Henry VII used it for symbolic purposes to create the Tudor rose

(both white and red) to symbolise national unity. However, is this actually what

Shakespeare was doing? If we are to read each play as being part of a whole then

the message becomes somewhat inconsistent. Henry VI is at times portrayed as a

rather saintly character (which some would contend is due to his status as a

Lancastrian monarch and Tudor ally) and yet in Henry VI Part 2 he is seen as unfit

to rule and the Yorkists come out rather more favourably. H. A. Kelly has argued

that Shakespeare is consistent within the context of each individual play but not

necessarily between different plays (evidenced by the fact that he wrote them out

of chronological order). The history plays are not intended as a serial drama in the

modern sense and Shakespeare is more interested in the troubles and motivations

of the characters in each drama than he is in painting a one-sided narrative of the

whole period.

On a broader level, then, the accuracy of Shakespeare’s history plays is

something of a mixed bag: well-researched and providing a deep, almost

biographical insight into his characters; yet full of contemporary references and

biases that are fundamentally ahistorical. To get a better and more detailed

assessment, it is best to look at specific plays to see how well Shakespeare’s works

stand up against real history.

Richard III – Tudor Propaganda?

For modern audiences, Richard III (1592) is the most controversial of

Shakespeare’s history plays when it comes to historical accuracy. Indeed, its

perceived bias inspired the formation of the Richard III Society, who seek to

rehabilitate Richard’s reputation which they feel has been unfairly maligned by

25

Shakespeare. So are they right? Is Shakespeare guilty of a terrible historical

injustice for the reputation of Richard III, or should the society leave him alone?

In the play (the second longest in Shakespeare’s canon), Richard is described as

a “rudely stamped…deformed, unfinished” hunchback and declares that he

is “determined to prove a villain”. In the earlier play Henry VI (Part 3) Richard

killed the saintly Henry VI and his son. In his own play, he schemes to engineer

the execution of his brother (Clarence), usurps and murders his nephews (the

Princes in the Tower) and poisons his own wife before justice is finally done when

he is defeated and killed by Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth.

While the broad sweep of events is largely accurate, there is a lot about

Shakespeare’s depiction of Richard III that is at best dubious. Prior to his

accession, Richard was seen as a loyal and well-respected noble and in his short

time as king he did enact laws to the benefit of the common people. His oldest

brother, Edward IV, is considered responsible for ordering the execution of Henry

VI and Clarence (who was, in fairness, not above a spot of treason). Richard had

known his wife since childhood and genuinely grieved her death, which was due to

tuberculosis rather than poison. Perhaps the most galling inaccuracy concerns

Richard’s death. In the play, Richard is thrown from his horse and wails “A horse,

a horse, my kingdom for a horse!” before being killed. In reality, Richard lost his

horse whilst charging bravely at Henry Tudor himself, but he refused the offer of a

horse that would have let him ride to safety. Even some of his most ardent critics

among the Tudor historians admitted that he fought bravely, so this one is all on

Shakespeare.

In Shakespeare’s defence, however, many of these inaccuracies are not

specifically Shakespearean inventions. There were contemporary rumours about

Richard poisoning his wife and the jury is still out on the fate of the Princes in the

Tower. Shakespeare did not invent the idea of Richard as a murderous, conniving

hunchback but was following earlier Tudor writers such as Sir Thomas More. The

discovery of Richard’s skeleton in 2012 revealed that, although he definitely was

26

not a hunchback, he did suffer from scoliosis which is a curvature of the spine, so

it is easy to see how when Richard’s body was stripped of its clothes his enemies

could make the leap to calling him a hunchback. Indeed, Tudor accounts of

Richard III should not be completely dismissed. Holinshead stated that after his

death, Richard’s naked body was paraded around Leicester before being interred at

Greyfriars Church. For centuries, his body was considered lost until it was

discovered under a Leicester car park where once had stood the church!

Henry V – At War with France and Ireland

If Richard III is the ultimate villain of Shakespeare’s history plays, then

Henry V is the ultimate hero, and surely too perfect to be a realistic portrayal? This

was the last (published) of his main history plays, written in 1599. Again,

Shakespeare leaned heavily on Holinshead and other Tudor chroniclers but also

other plays about Henry V (particularly one called The Famous Victories of Henry

the Fifth, concerning the transformation from dissolute youth to warrior king).

Henry V is often seen as a tubthumping, nationalistic play, with Henry inspiring his

men with great oratory at the siege of Harfleur (“Once more unto the breach, dear

friends, once more, or close the wall up with our English dead”) and the Battle of

Agincourt (“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; for he today that sheds

his blood with me shall be my brother”). However, the events of the play are

actually surprisingly accurate. The implication that Henry went to war because the

French teased him with tennis balls is, of course, a fanciful invention and he omits

the presence of a French cavalry charge at Agincourt (due the limitations of

portraying this on stage), but the events in the play did occur largely as described

by Shakespeare (albeit over a longer period of time in reality). Although Henry’s

speeches are invented by Shakespeare, Henry is thought to have had a certain

strength in his speeches that his captains lacked.

Indeed, it is unfair to characterise the play as pro-war. Shakespeare’s

presentation of war is much more ambiguous than some of the film adaptations

have implied (most famously Laurence Olivier’s wartime version in 1944). This is

27

in large part because of the context in which the play was written, with England

preparing for a war against Ireland led by the Earl of Essex for which there was

limited enthusiasm. The night before Agincourt, a disguised Henry is forced to

confront the sufferings of his ordinary soldiers and their fears, with the soldier

Michael Williams telling him, “I am afeard there are few die well that die in a

battle”. Shakespeare also includes the real-life murder of French prisoners at

Agincourt by Henry when it appeared the French were regrouping. This

juxtaposition of heroism and the bleak realities of war reveals a more nuanced play

than is sometimes perceived and one which reflected the uncertain sentiments of

the audience in 1599 – as James Shapiro has stated, it was neither a pro-war nor

anti-war play, but rather a “going-to-war play”.

Richard II – The Dangerous Subversive?

If Richard III was an obvious villain and Henry V and obvious hero, Richard

II’s character is a much more complex proposition. The play (written in 1595)

would prove troublesome because of its contemporary resonance and, although

Shakespeare would put much less of Elizabethan England into the play than

with Henry V, Richard II would prove to be Shakespeare’s most controversial play.

The 1590s was a period of dynastic uncertainty, with Elizabeth I childless (like

Richard II) and facing war in Ireland (like Richard II) and plots from unruly nobles

(like Richard II). In 1601, allies of the Earl of Essex paid for Shakespeare’s

company to perform Richard II two days before his attempted coup – the actors

protested it was “so old and so long out of use” that it would not be worth doing

until they were offered a goodly sum to change their minds. Although Shakespeare

does not seem to have suffered from this association, it is notable that the

deposition scene was never printed during Elizabeth’s lifetime. Indeed, when going

through documents relating to Richard Elizabeth allegedly observed, “I am

Richard the Second, know ye not that?” in reference to Shakespeare’s play.

Ironically, Richard II is perhaps the most accurate of these plays. Although (like

the others) the events are somewhat quickened, they are essentially correct. The

28

early scene where Richard interrupts a trial by combat between Bolingbroke and

Mowbray makes for great drama but it was also true – the combat was about to

take place when, at the last moment, Richard intervened and exiled the pair. Even

Richard’s moving soliloquy on the “death of kings” is close to an eyewitness

account of a rather maudlin speech he made during his imprisonment (Shakespeare

moves it before his imprisonment). Less accurately, Richard’s wife (the “Queen”)

is presented as an adult whereas in reality Isabella of Valois (his second wife) was

just a child, his first wife having died. Shakespeare often merged historical figures

occupying the same position (e.g. a father and son in the nobility) into one

character to simplify the narrative. The most significant change, however, was the

invention of the character Exton for the murder of Richard II – it is generally

thought that Richard was left to starve to death, almost certainly on the orders of

Bolingbroke (who became Henry IV).

Although the events are mostly accurate, Shakespeare has been criticised for being

too kind to Richard II. This is his only play written entirely in verse, making it a

much more lyrical affair than some of his other works, thus imbuing Richard with

a certain dignity that many feel he does not deserve. However, Richard is by no

means given a glowing portrayal – Shakespeare (correctly) emphasises Richard’s

belief in the Divine Right of Kings, which makes him out of touch and tyrannical

as king. Further, Gaunt’s famous, patriotic speech lauding “this sceptred isle…this

blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England” is actually a tirade against

Richard, who has made England “bound in with shame” due to his misgovernance

of the kingdom.

Throughout, Richard is afforded great eloquence as he struggles to come to

terms with what it means for him to lose the crown and he is forced to come to

terms with the harsh realities of not being a divinely ordained king but a usurped

man. He mocks his previous sense of divine regality, deriding “the hollow crown

that rounds the mortal temples of a king” and observing, “I live with bread like

you, feel want, taste grief, need friends: subjected thus, how can you say to me, I

29

am a king?” The tragedy of Richard is that he realises his flaws all too late.

Whether or not he really asked himself such soul-searching questions, of course, is

a matter for speculation, but such speculation is par for the course for any writer

and Shakespeare’s interpretation has a ring of truth to it.

30

Conclusion

Shakespeare’s legacy is as rich and diverse as his work; his plays have

spawned countless adaptations across multiple genres and cultures. His plays have

had an enduring presence on stage and film. His writings have been compiled in

various iterations of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, which include

all of his plays, sonnets, and other poems. William Shakespeare continues to be

one of the most important literary figures of the English language. Especially, ,

elements of Shakespearean comedy are myriad and even today there are still many

aspects to his plays which we could analyse and dissect. What’s most obvious,

however, is that Shakespeare’s understanding of the complicated interactions

between people have laid the foundations for most comedic storytelling.

Shakespeare’s comedies explore how experiences may not necessarily be as we

perceive it to be; they found humour in pondering how suffering may be due to

reasons beyond our control; and they expose the irony in how thinking rationally

stands in stark contrast to our heart’s desires. For those reasons, it’s easy to

appreciate why his plays have retained a timeless appeal, and for writers there is

still much to be learned.

Also, Shakespeare tragedies stand out from other tragedies of dramatists. A

Shakespearean tragedy is a specific type of tragedy (a written work with a sad

ending where the hero either dies or ends up mentally, emotionally, or spiritually

devastated beyond recovery) that also includes all of the additional elements

discussed in this article

Shakespeare’s history plays are enormously appealing. Not only do they

give insight into the political processes of medieval and renaissance politics but

they also offer a glimpse of life from the top to the very bottom of society – the

royal court, the nobility, tavern life, brothels, beggars, everything. The greatest

English actual and fictional hero, Henry V, and the most notorious fictional

bounder, Falstaff, are seen in several scenes together. Not only that, but those

scenes are among the most entertaining, profound, and memorable in the whole

of English literature. That’s some achievement.

Finally, although adding this at the end of the course paper and leaving it in

the air, several questions are begged: what we see in the Shakespeare histories is

not medieval society at all, but Elizabethan and Jacobean society. This is because

although Shakespeare was writing ‘history’, using historical figures and events,

what he was really doing was writing about the politics, entertainments and social

situations of his own time. A major feature of Shakespeare’s appeal to his own

generation was recognition, something Shakespeare exploited relentlessly.

In conclusion , we can summarize that like anyone dramatising historical

events, Shakespeare was not shy in changing things to suit dramatic purpose. The

dialogue was elevated far above what would have been spoken at the time, events

were quickened to tell a better story and characters were sometimes merged to

make things simpler. Shakespeare was also guilty at times of putting the

Elizabethan world (or at least it’s constructed perception of the medieval world)

into the history plays, as well as an interpretation of history that at times can come

across as Tudor propaganda. However, the broad sweep of the events in

Shakespeare’s history plays are usually pretty accurate and he had at least done his

research with the best works of English history available at the time.

Shakespeare’s Richard III is the worst offender when it comes to accuracy, with an

almost pantomime villain who is twisted into caricature rather than a real insight

into the real king. Yet, both Henry V and Richard II show a surprising amount of

accuracy and nuance, showing a depth of analysis into the realities of those

characters going through those events. It is not Shakespeare’s fault that his works

became so definitive that for many people his plays are the real history, nor that it

is difficult to replace his version of Richard III or Henry V with one informed by

more thoroughly researched modern biographies. Shakespeare read the chronicles

and captured the history as best he could but he was no historian – rather, he used

history to find the human stories that made for great drama.

The list of used literature

1. Dowden, Edward, ed., Histories and Poems, Oxford Shakespeare, vol. 3

(Oxford, 1912), p. 82

2. Greg, W. W., The Editorial Problem in Shakespeare (Oxford, 1942), p.

3. Tillyard, E. M. W., The Elizabethan World Picture (London 1943); Shakespeare's

History Plays (London 1944)

4. Campbell, L. B., Shakespeare's Histories (San Marino 1947)

5. Briggs, W. D., Marlowe's 'Edward II' (London 1914), p. cxxv

6. Ogburn, Dorothy, and Ogburn, Charlton, This Star of England: William

Shakespeare, Man of the Renaissance (New York, 1952), pp. 709–710

7. Pitcher, Seymour M., The Case for Shakespeare's Authorship of 'The Famous

Victories' (New York, 1961), p. 186

8. Ward, B. M., The Seventeenth Earl of Oxford (1550–1604), from Contemporary

Documents (London, 1928), pp. 257, 282

9. Ward, B. M., ' The Famous Victories of Henry V : Its Place in Elizabethan

Dramatic Literature', Review of English Studies, IV, July 1928; p. 284

10.

Charlton, H. B., Waller, R. D., eds., Marlowe: Edward II (London 1955, 1st

edn.), p. 54

11. Lucas, F. L., The Complete Works of John Webster (London, 1927), vol. 3, pp.

125–126

12. Danby, John F., Shakespeare's Doctrine of Nature (London, 1949)

13. Leggatt, Alexander, Shakespeare's Political Drama: The History Plays and

the Roman Plays (London 1988)

14.Spencer, T. J. B., Shakespeare: The Roman Plays (London 1963)

15. Butler, Martin, ed., Re-Presenting Ben Jonson: Text, History,

16.Park Honan, Shakespeare: A Life, Oxford University Press, New York,

1999, p. 342.

17.Duncan-Jones, K., Ungentle Shakespeare (London 2001)