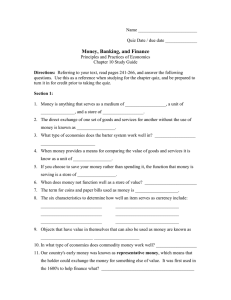

(/) Home (/en) / articles (/en/articles) / basic banking law Basic Banking Law Few people like banks and all of us use them constantly. Whether it's a simple checking account or a home loan, a college tuition loan or purchasing a Certi cate of Deport, banks are an inherent part of the life of almost every citizen and certainly every business in the United State. The shock and anger of most citizens when they confronted the fact that Banks had enlarged their business practices to include high risk investments came to a head in 2008 when even the largest banks were on the verge of bankruptcy and the United States tax payer was required to “bail them out.” We were advised of the unpalatable truth that the collapse of our banking system would have been economic disaster for the entire economy. Yet today, half a decade since the crisis, almost all of the reforms, even if passed, were not fully funded by Congress so that enforcement is problematical. Powerful banking lobbyists continue to work to hamstring many of the proposed reforms. Whether one is determined on greater regulation or not, the sad fact is that the regulations that were enacted are seldom enforced and the banking industry is largely unchanged from the time before the instant recession. If there is any change it is that banks are more nervous about loaning monies and are more determined in their own due diligence. Further, at least on the books, there is nascent reform and better oversight enacted though whether this will become reality is another matter. There are good and honest bankers who are as upset at the result of the actions of a minority of bankers and hope to see an industry more responsible and better operated. It will take time to see if such people achieve e ective operational control of these institutions. This article shall brie y outline the basic law concerning interaction with banks and the duties imposed upon them by both State and Federal regulation. As was once said about people of the opposite sex, “one can’t live with them and can’t live without them.” Any business that seeks to prosper is likely to need a good relationship with a bank and to achieve that requires some familiarity with the relevant laws that apply. The Statutory Scheme Applying to Banks: The law governing banks, bank accounts, and lending in the United States is a hybrid of federal and state statutory law. Consumers and businesses usually establish bank accounts in banks and savings associations chartered under state or federal law. The law under which a bank is chartered regulates that particular bank. A mix of state and federal law regulates the majority of banking operations and transactions by bank customers. Article 3 of the Uniform Commercial Code, as adopted by the various states, governs transactions involving negotiable instruments, including checks. Article 4 of the Uniform Commercial Code governs bank deposits and collections, including the rights and responsibilities of depository banks, collecting banks, and banks responsible for the payment of a check. Other provisions of the Uniform Commercial Code are also relevant to banking and lending law, including Article 4A (related to funds transfers), Article 5 (related to letters of credit), Article 8 (related to securities), and Article 9 (related to secured transactions). The Federal Reserve System regulates chartered banks as a whole. A number of regulations govern a check when it passes through the Federal Reserve System. These regulations govern the availability of funds available to a depositor in his or her bank account, the delay between the time a bank receives a deposit and the time the funds should be made available, and the process to follow when a check is dishonored for non-payment. Federal law provides some protection to bank customers. Prompted by banking crises in the 1930s, the federal government established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which insures bank accounts of individuals and institutions in amounts up to $100,000. A large number of statutes exist a ecting banks, banking, and lending. A brief summary of these is as follows: National Bank Act of 1864 established a national banking systems and chartering of national banks. Federal Reserve Act of 1913 established the Federal Reserve System. Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall Act) established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), originally intended to be temporary. Banking Act of 1935 established the FDIC as a permanent agency. Federal Deposit Insurance Act of 1950 revised and consolidated previous laws governing the FDIC. Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 set forth requirements for the establishment of bank holding companies. International Banking Act of 1978 required foreign banks to t within the federal regulatory framework. Financial Institutions Regulatory and Interest Rate Control Act of 1978 created the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council; it also established limits and reporting requirements for insider transactions involving banks and modi ed provisions governing transfers of electronic funds. Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 began to eliminate ceilings on interest rates of savings and other accounts and raised the insurance ceiling of insured account holders to $100,000. Depository Institutions Act of 1982 (Gar-St. Germain Act) expanded the powers of the FDIC and further eliminated ceilings on interest rates. Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987 established new standards for the availability of expedited funds and further expanded FDIC authority. Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 set forth a number of reforms and revisions, designed to ensure trust in the savings and loan industry. Crime Control Act of 1990 expanded the ability of federal regulators to combat fraud in nancial institutions. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Act of 1991 expanded the power and authority of the FDIC considerably. Housing and Community Development Act of 1992 set forth provisions to combat money laundering and provided some regulatory relief to certain nancial institutions. Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 established the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund to provide assistance to community development nancial institutions. Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching E ciency Act of 1994 permitted bank holding companies that were adequately capitalized and managed to acquire banks in any state. Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork Reduction Act of 1996 brought forth a number of changes, many of which related to the modi cation of regulation of nancial institutions. Gramm-Leach Bliley Act of 1999 brought forth numerous changes, including the restriction of disclosure of nonpublic customer information by nancial institutions. The Act provided penalties for anyone who obtains nonpublic customer information from a nancial institution under false pretenses. The economic collapse of 2007-10 involving banks on an international scale led to various regulations concerning the activities, reserve requirements and due diligence required of banks. These latest laws are often not funded with sums su cient to provide e ective enforcement and are currently at risk of repeal based on a angrily divided Congress and executive. Numerous federal agencies promulgate regulations relevant to banks and banking, including the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Reserve Board, General Accounting O ce, National Credit Union Administration, and Treasury Department. The ability for bank customers to engage in electronic banking has had a signi cant e ect on the laws of banking in the United States. Some laws that govern paper checks and other traditional instruments are di cult to apply to corresponding electronic transfers. As technology develops and a ects the banking industry, banking law will likely change even more. Types of Transactions: Checks and Negotiable Instruments: Article 3 of the Uniform Commercial Code, drafted by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws and adopted in every state except Louisiana, governs the creation and transfer of negotiable instruments. Since checks are negotiable instruments, the provisions in Article 3 apply. Because banks are lending institutions that create notes and other instruments, Article 3 will also apply in other circumstances that do not involve checks. A person who establishes an account at a bank may make a written order on that account in the form of a check. The account holder is called the drawer, while the person named on the check is called the payee. When the drawer orders the bank to pay the person named in the check, the bank is obligated to do so and reduce the drawer’s account by the amount on the check. A bank ordinarily has no obligation to honor a check from a person other than a depositor. However, both the drawer’s and payee’s banks generally must honor these checks if there are su cient funds to cover the amount of the check. The payee’s bank must generally honor a check written to the order of the payee if the payee has su cient funds to cover the amount of the check, in case the drawer of the check does not have su cient funds. A drawer may request from the bank a certi ed check, which means the check is guaranteed. Certi ed checks must be honored by any bank, and, as such, are considered the same as cash. A customer’s bank has a duty to know each customer’s signature. If another party forges the signature of the customer, the customer is generally not liable for the amount of the check. However, If a business is in California and the employee of the business forges a signature, the bank is usually not liable since the employee is an agent of the drawer. If the forger is not an agent, however, banks may recover from the forger but may not generally recover from the innocent customer or a third person who in good faith and without notice of the forgery gave cash or other items of value in exchange for the check. Drawers have the right to inspect all checks charged against their accounts to ensure that no forgeries have occurred. Drawers also have rights to stop payment on checks that have been neither paid nor certi ed by their banks. This is done through a stop payment order issued by the customer to the bank. If a bank pays a check notwithstanding the stop payment order, the bank is liable to the customer for the value of the check. Many of the rules applying the checks apply to all negotiable instruments. Banks that serve as lending institutions routinely exchange loans for promissory notes, which are most likely negotiable instruments. These instruments are considered property and may be bought and sold by other entities. Article 4 of the Uniform Commercial Code governs the operation of checking accounts, though several federal laws supplement the provisions of Article 4. The provisions of this uniform law de ne rights regarding bank deposits and collections. It governs such relationships as those between a depository bank and a collecting bank and those between a Payor bank and its customers. Article 4A of the Uniform Commercial Code governs methods of payment whereby a person making a payment (called the “originator”) transmits directly an instruction to a bank to make a payment to a third person (called the “bene ciary”). Article 4A covers the issuance and acceptance of a payment order from a customer to a bank, the execution of a payment order by a receiving bank and the actual payment of the payment order. Letters of Credit: Article 5 of the Uniform Commercial Code governs transactions involving the issuance of letters of credit. Such letters of credit are generally issued when a party (the “applicant”) applies for credit in a transaction of some sort with a third party (the “bene ciary”). The bank will issue a letter of credit to the bene ciary prior to the transaction. This letter is a de nite undertaking by the bank to honor the letter of credit at the time the bene ciary presents this letter. Article 5 governs issuance, amendments, cancellation, duration, transfer, and assignment of letters of credit. It also de nes the rights and obligations of the parties involved in the issuance of a letter of credit. The Role of the Federal Reserve System: The Federal Reserve Board, appointed by the President, has been delegated signi cant responsibility related to the implementation of laws governing banks and banking. The Board has issued more than thirty major regulations on a variety of issues a ecting the banking industry. When a check passes through the Federal Reserve System, Regulation J applies. This regulation governs the collection of checks and other items by Federal Reserve Banks, as well as many funds transfers. This regulation also establishes procedures, responsibilities, and duties among Federal Reserve banks, the Payors, and other senders of checks through the Federal Reserve System, and the senders of wire transmissions. Regulation J is contained in Title 12 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 210. A second signi cant regulation promulgated by the Federal Reserve Board is Regulation CC, which governs the availability of funds in a bank customer’s account. This regulation also governs the collection of checks. Under this regulation, cash deposits made by a customer into a bank account must be available to the customer no later than the end of the business day after the day the funds were deposited. The next-day rule also applies to several check deposits, as de ned by the regulation, although banks are not required to make funds available for as long as ve days after deposit for many other types of checks. Regulation CC also governs the payment of interest, the responsibilities of various banks regarding the return of checks. Liabilities of the bank for failure to adhere to these rules are de ned by the regulation. Regulation CC is contained in Title 12 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 229. Other Federal Reserve Board regulations cover a variety of transactions under a myriad of statutes. These include such provisions as those requiring equal credit opportunity; transfer of electronic funds; consumer leasing; privacy of consumer nancial information; and truth in lending. Deposit Insurance. Congress in 1933 established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which is funded by premiums paid by member institutions. If a customer holds an account at a bank that is a member institution of the FDIC, the customer’s accounts are insured for an aggregate total of $100,000. Banks that are member institutions are required to display prominently signs indicating that the bank is a member of the FDIC or a sign that states “Deposits Federally Insured to $100,000—Backed by the Full Faith and Credit of the United States Government.” This applies to many banks that are chartered either federally or by way of state statute. Truth in Lending. The Truth in Lending Act, which was part of the Consumer Credit Protection Act, provides protection to consumers by requiring lenders to disclose costs and terms related to a loan. Most of these disclosures are contained in a loan application. Lenders must include several of the following items: Terms and costs of loan plans, including annual percentage rates, fees, and points The total amount of principal being nanced Payment due dates, including provisions for late payment fees Details of variable-interest loans Total amount of nance charges Details about whether a loan is assumable Application fees Pre-payment penalties The Truth in Lending Act also requires lenders to make certain disclosures regarding advertisements for loan rates and terms. Speci c terms of the credit must be disclosed, and if the advertisement indicates a rate, it must be stated in terms of an annual percentage rate, which takes into account additional costs incurred relating to the loan. Other restrictions on advertising loan rates also apply. If a bank or other lending institution fails to adhere to the provision of the Truth in Lending Act, severe penalties apply. The Federal Reserve Board has been delegated authority to prescribe regulations to enforce the provisions of the Trust in Lending Act. These regulations are contained in Regulation Z of the Board. Interest Rates Charged. The federal government until the early 1980s regulated interest rates charged on bank accounts. Interest rates on savings accounts were generally limited, while interest rates on other types of accounts were generally prohibited. The Depository Institutions Deregulation Act of 1980 and Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act eliminated restrictions and prohibitions on interest rates on savings, checking, money market and other types of accounts. This necessarily means that the institutions which are in business to loan money are the very institutions not limited on the interest that can be charged, though in most states individuals and businesses are held to restrictions on interest. See our article on Usury. Crimes Against Banks. Congress has passed numerous criminal statutes relating to crimes against banks and banking institutions. Some crimes are related to violent acts, such as robbery, while others focus on nonviolent crimes, such as money laundering. Each of the crimes listed below is contained in Title 18 of the United States Code. Bank bribery is prohibited under Title 18, sections 212 through 215. Theft by a bank o cer or employee (“embezzlement”) is prohibited under Title 18, section 656. False bank entry is prohibited under Title 18, section 1005. False statements to the FDIC are prohibited under Title 18, section 1007. Bank fraud is prohibited under Title 18, section 1344. Obstruction of an examination of a nancial institution is prohibited under Title 18, section 1517. Money laundering is prohibited under Title 18, sections 1956 through 1960. Bank robbery is prohibited under Title 18, section 2113. Crimes involving coins and currency are prohibited under provisions in Title 18, Chapter 17. Banks versus Other Institutions: Banks are only one of several kinds of nancial institutions that o er nancial services to their customers. The term “bank” is often used as a collective term to describe any one of the numerous forms of nancial institutions. Banks, like most other bank-like nancial institutions, are established by charters. A charter is o cial permission from a regulating authority (like a state) to accept deposits and/or to provide nancial services. Charters provide the speci cs of a bank’s powers and obligations. State and federal governments closely regulate banks and bank accounts. Accounts for customers may be established by national and state nancial institutions, all of which are regulated by the law under which they are established. Savings and Loans The function of savings and loan associations is the nancing of long-term residential mortgages. Savings and loan associations accept deposits in savings accounts, pay interest on these accounts, and make loans to residential home buyers. They do not make business loans of any kind, nor do they provide many of the other business services one nds in commercial banks. A privately managed home nancing institution, a savings and loan accepts savings accounts from individuals and other sources. This money is then principally invested in loans for the construction, purchase, or improvement of homes. This is not to say that businesses do not utilize the resources of a Savings and Loan. Note that Savings and loan associations are primarily involved in making residential loans. Consequently, they may be good sources of indirect business nancing for homeowners who own substantial equity in their homes. For example, if homeowners need money for their businesses, they can re nance their homes or take out a second mortgage on the equity through a savings and loan association. The home equity loan application process at a savings and loan association is generally simpler than it is for a commercial bank because it is made on the equity of the home up to a maximum percentage of the equity, usually between 75 percent to 80 percent. The savings and loan association bears little risk if the home is located in a stable or appreciating market value area. If the borrower defaults on the loan, the savings and loan association can foreclose the mortgage and, sell the property to retire the loan, doing so often for a pro t. The collapse of real estate in 2007 and 2008 has altered the security of many of these loans but few do not expect a recovery eventually. Credit Unions The rst credit union in the United States was formed in 1909. As of 2002, there were over 10,000 credit unions in the United States. They control assets of nearly one-half a trillion dollars and serve about one-quarter of the population. Credit unions are members-only institutions. Individuals must join a credit union to take advantage of its services. Note they cannot join just any credit union—they must rst be eligible for membership. Most credit unions are organized to serve members of a particular community, group or groups of employees, or members of an organization or association. Large corporations, unions, or educational institutions are some of the groups who commonly form credit unions for their members or employees. Federal credit unions are nonpro t, cooperative nancial institutions owned and operated by their members. Credit unions are democratically controlled with members given the opportunity to vote on important issues that a ect the running of the credit union. For example, the board that runs a credit union is elected by its members. Credit unions provide an alternative to banks and savings and loan associations as “safe places” in which to place savings and borrow at reasonable rates. Credit unions pool their members’ funds to make loans to one another. In addition to typical credit unions that serve members and provide banking and lending services, there are a few special types of credit unions: Community development credit unions: The NCUA established the O ce of Community Development Credit Unions in early 1994. These credit unions serve mostly low-income members in economically distressed and/or nancially deprived areas. Part of their function is to educate their members in fundamental money management concepts. At the same time, they provide an economic base in order to stimulate economic development and renewal to their communities. Corporate credit unions: These institutions do not provide services to individuals, but they serve as a sort of credit union for credit unions. Nationwide, there are over thirty federally insured corporate credit unions; they provide investment, liquidity, and payment services for their member credit unions. Automated Teller Machines: Not all banks or nancial institutions have automated teller machines (“ATMs”.) Before ATMs, banks employed tellers to help their customers conduct all their banking business. Because ATMs can inexpensively perform many of the functions formerly done by tellers, ATMs have replaced many tellers in the banking institution. There are no laws requiring banks or other nancial institutions to have ATMs. Instead, having one is a business decision for each bank. ATMs o er distinct advantages over traditional teller operations in terms of their locations and hours of operation. ATMs are relatively small and can be placed where banks would not ordinarily open a branch (gas stations, hotel lobbies, airports). Furthermore, ATMs are open when banks are closed; ATMs can function for twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. There has been a process of homogenization in the banking and nancial industries. Services appear to be similar in many types of institutions. Nevertheless, some important di erences among institutions remain. These di erences may exist among banking institutions within a single state, and among the same type of institution from state to state. For example, a Missouri state chartered bank may have authority to conduct certain forms of business that are very di erent from those of a Missouri savings bank. Likewise, a Missouri savings and loan may have di erent powers from a Missouri national bank. These various rules and powers result in a di erence in services among the spectrum of nancial institutions. These di erences can a ect factors like interest rates, issuance of credit cards, ATM services, and so forth. ATMs can be cost e ective to operate when compared to the cost of hiring and training bank tellers. Even so, there are costs associated with owning and operating ATMs, including the costs for the following: buying the machine renting space for the ATM maintaining the ATM’s mechanical parts paying personnel to load it with money and remove deposits (if any) Banks or other nancial institutions may charge patrons for using their bank’s ATM as long as the bank or nancial institution informs patrons of the terms and conditions of their accounts, and all applicable charges. This information is often contained in the monthly statements. On the other hand, if individuals use an ATM that does not belong to their own bank, the ATM’s owner can charge them for using it. This is true even though they are gaining access to their own money kept in their own bank. Likewise, a bank can also charge its patrons for using someone else’s ATM machine. In this way, individuals may incur two charges for using an ATM that does not belong to the bank or nancial institution at which they are customers. Conclusion: One aspect of the recent collapse in the banking industry that was remarkable was the lack of understanding demonstrated as to their actual relatively new role in our economy and their recent tendency to engage in the type of risky loans and hedge fund investments that one does not associate with the staid world of banking. One other aspect soon revealed as the public learned more about the banks was their intricate and complex methodology of charging for various services that used to be gratis. Few read the small print on the monthly statement from the credit card company or the loan documents, but the simple fact is that the various banks make massive pro ts by use of the tendency of businesses and the public at large to ignore the powerful and expensive methods that banks have used to become powerful and e ective forces in the economy. Jimmy Stewart at the local bank has been replaced by behemoths that engage in risky business internationally, charge for services that are often incomprehensible to the business world, and demand support from the tax payer if things go wrong. While it is likely the industry, sooner or later, will be forced to limit their risky activities, their relationship to their clients will remain one that will require each customer to spend the time to understand the workings of the banks in order to achieve maximum cost bene t from the relationship…and avoid the many pitfalls found in the small print. Article Categories Business Law (/en/articles/category/business-law) Business Law/Litigation (/en/articles/category/business-law/business-lawlitigation) Consumer Rights and Remedies (/en/articles/category/consumer-rights-and-remedies) Business, Purchase and Credit Problems (/en/articles/category/consumer-rights-and-remedies/business-purchase-and-credit-problems) Share this article! (/#email) (/#google_gmail) (/#yahoo_mail) (/#copy_link) (https://www.addtoany.com/share#url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.stimmellaw.com%2Fen%2Farticles%2Fbasic-bankinglaw&title=Basic%20Banking%20Law) (/articles) Find Articles in our Online Library (/articles) Find helpful legal articles & summaries on key areas of the law! Start resolving your legal matters - contact us today! (/contact) Stimmel, Stimmel & Roeser Home (/en) Cookie Policy (/en/cookies) Our Firm (/en/about-us) Privacy Policy (/en/privacy) Firm Overview (/en/about-us) Terms of Use (/en/terms-use) Attorneys (/en/attorneys) Sta Login (/en/user/login) Typical Cases (/en/typical-cases) Contact (/en/contact) Videos (/en/videos) Community (/en/our-community) Articles (/en/articles) Founded in 1939, our law rm combines the ability to represent clients in domestic or international matters with the personal interaction with clients that is traditional to a long established law rm. Read more about our rm (/about-us) © 2021, Stimmel, Stimmel & Roeser, All rights reserved | Terms of Use (/terms-use) | Site by Bay Design (http://www.baydesignassociates.com)