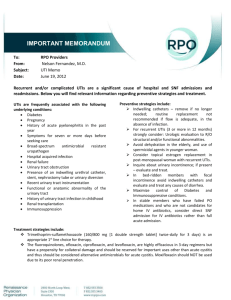

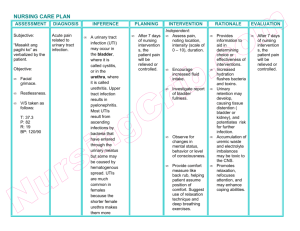

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies more than 50% of overall antibiotic prescriptions written for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs) in the outpatient setting are inappropriate. Contributing to this problem includes prescribing a broad-spectrum antibiotic when a narrow-spectrum option is available, incorrect duration of therapy, and prescribing antibiotics when the condition does not warrant antimicrobial treatment (Heppner et al., 2020). Therefore, it is vital for healthcare providers to understand how to properly diagnose and treat this common condition. Risk factors for UTI include female gender, pregnancy, history of UTIs or recurrent infections, diabetes mellitus or other immunocompromising conditions, failure to void after intercourse or increased sexual intercourse, spermicide use, infected renal calculi, low fluid intake, poor hygiene and urinary catheterization (Codina Leik, 2018). The bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), are the main bacterial strains that lead to in the outpatient setting. Other causative organisms include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis (Salh, 2021). Diagnostic symptoms of urinary tract infections include change in frequency, dysuria, urgency, and presence or absence of vaginal discharge, but urinary tract infections may present differently in older women (Salh, 2021). A more acute presentation, including high fever, chills, flank pain, costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, nausea, and vomiting is suggestive of complicated UTI. Patients should be queried about their sexual and medical history, specifically immunocompromising disease or drugs, and any recent procedures they may have had performed (Buttaro et al., 2021). A thorough review of symptoms and physical exam should be done. In cases in which the probability of urinary tract infection is moderate or unclear, urine culture should be performed. Urine culture is the gold standard for detection of urinary tract infection. However, asymptomatic bacteriuria is common, particularly in older women, and should not be treated with antibiotics (Chu & Lowder, 2018). Cultures should always be obtained in young men because these infections are unusual and suggestive of an underlying problem (Buttaro et al., 2021). Urinary tract infections can be classified as uncomplicated, complicated, recurrent, or asymptomatic. Uncomplicated UTIs are characterized by a recent onset of mild to moderate symptoms and occur in healthy female patients who are not immunocompromised or pregnant, and without a history of frequent UTIs or structural abnormalities. UTIs are considered complicated in any male patient, or if the infection is associated with a structural or functional abnormality of the urinary tract, as these can lead to serious consequences if treated improperly. Recurrent UTIs , commonly found in young females, are symptomatic UTIs that occur after treatment and resolution of symptoms (Buttaro et al., 2021). Asymptomatic bacteriuria is the presence of bacteria in the properly collected urine of a patient that has no signs or symptoms of a urinary tract infection. It is very common in clinical practice and its incidence increases with age. Most patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria will never develop symptomatic UTIs and will have no adverse consequences. The patients that should be treated for asymptomatic bacteriuria include pregnant patients, patients undergoing urologic procedures in which mucosal bleeding is expected, and patients who are in the first three months following renal transplantation (Givler & Givler, 2021). When reviewing UA results the provider should be looking at the color, clarity and if there is any hematuria. Positive nitrites, leucocytes (white blood cells), and alkaline urine may be present in patients with UTI (Yates, 2016). The most important thing for providers to consider is that UA results should be interpreted in conjunction with an individual’s clinical presentation. The presence of nitrites can be suggestive of a UTI but clinical presentation of symptoms should also be taken into account. The absence of nitrites, however, does not always rule out the presence of a UTI; Nitrites are not usually found in urine and are associated with the presence of bacteria that can convert nitrate into nitrite (Yates, 2016). Leukocytes are usually associated with a urinary infection but sometimes may indicate a more severe renal problem. Alkaline urine may indicate a UTI with certain types of bacteria, such as Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella or Pseudomonas. However, pH is also affected by other factors such as diet. Blood in the urine can be indicative of kidney disease; inflammatory lesions of the urinary tract (infection or cancer); renal damage; or kidney/renal stones. It can also indicate a blood-clotting disorder or be a side-effect of anticoagulant drugs (Yates, 2016). Hematuria could also be a normal finding in a patient menstruating. When reviewing the urinalaysis, a large number of epithelial cells indicates sample contamination. A leukocyte level of > 10 WBCs/ml could indicate UTI. For culture and sensitivity, greater than or equal to 105 colony forming units (CFU)/ml of bacteria of one dominant kind is indicative of UTI. Nitrites could mean the patient has an infection with gram negative bacteria, usually E. Coli. Hyaline casts are normal and may be seen in concentrated urine, however WBC casts may be seen with infections and RBC casts and proteinuria are diagnostic of glomerulonephritis (Codina Leik, 2018). Studies have shown that provider education and use of evidence-based treatment algorithms are effective to improve prescribing concordance with clinical guidelines and antimicrobial stewardship (Heppner et al., 2020). Antiobiotic choice is empiric, covering enteric organisms. First-line options include nitrofurantoin and trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX). Other options include References Buttaro, T. M., Polgar-Bailey, P., Sandberg-Cook, J., & Trybulski, J. (2021). Primary care: Interprofessional collaborative practice (6th ed.). Elsevier. Chu, C. M., & Lowder, J. L. (2018). Diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections across age groups. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 219(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.231 Codina Leik, M. T. (2018). Adult-gerontology nurse practitioner certification intensive review: Fast facts and practice questions (pp. 280–281). Springer Publishing Company, LLC. Givler, D. N., & Givler, A. (2021, October 11). Asymptomatic bacteriuria. StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441848/ Heppner, P. E., Schnepper, L., Langer, K., Fritzlar, S., & Deppa, B. (2020). Evidence of antimicrobial stewardship in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.06.003 Salh, K. K. (2021, June 24). Evolution of the antimicrobial resistance of bacteria causing urinary tract infections. Physician's Weekly. Retrieved January 18, 2022, from https://www.physiciansweekly.com/evolution-of-the-antimicrobial-resistance-ofbacteria-causing-urinary-tract-infections?pagetype=general-urology Yates, A. (2016). Urinalysis: how to interpret results. Nursing Times; Online issue 2, 1-3.