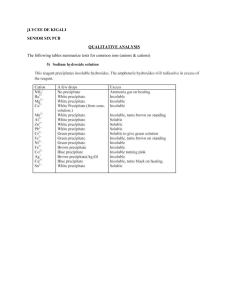

Symposium on Gastroenterology Contrast Radiography of the Digestive Tract Indications, Techniques, and Complications William R. Brawner, Jr., D.V.M., Ph.D.,* and jan E. Bartels, D.V.M., M.S.t Radiography is an important diagnostic aid in the evaluation of small animals with signs of esophageal or gastrointestinal disease. Thoracic or abdominal radiography may provide useful information about digestive disorders, but that information is often limited by the inherently poor visibility of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines on survey (plain film) radiographs. Radiographic visualization of anatomic structures depends on the variable absorption of X-rays by organs and tissues of varying thickness and chemical composition. Based on tissue composition, there are four distinct radiographic densities of biologic materials: gas, fat, fluid, and bone, in increasing order of radiodensity. Differences in density among body structures provide natural subject contrast and allow radiographic visualization of these structures. Perception of borders or margins is the key feature in recognition of anatomic structures on radiographs. Margins are perceived where there is a distinct density gradient. When two structures of the same density are in contact, the confluent borders cannot be distinguished. Radiographs of extremities yield excellent skeletal contrast because bone is much more radiodense than the surrounding soft tissue. The thorax also has excellent natural subject contrast created by the presence of air (gas) in the lungs. The heart, pulmonary vasculature, and interstitium of the lungs are clearly contrasted against the alveolar spaces. Conversely, radiographs of the abdomen have poor natural subject contra£t because all intra-abdominal organs are composed of fluid-density tissues. The outlines of these organs are visible only because fat separates the serosal borders. Abundant intra-abdominal fat improves contrast and visualization of abdom*Diplomate, American College of Veterinary Radiology; Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Auburn University School of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn, Alabama tDiplomate, American College of Veterinary Radiology; Professor and Head, Department of Radiology, Auburn University School of Veterinary Medicine, Al'lburn, Alabama Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice-Yo!. 13, No. 3, August 1983 599 600 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER. jR. AND jAN E. BARTELS Figure l. Survey (plain film) abdominal radiographs of an emaciated dog (A), a healthy, well-conditioned dog (B), and a fat cat (C). Visualization of abdominal organs on survey radiographs is possible only when fat separates the serosal borders of the organs. Increased fat accumulation separates organs, provides more contrast, and thus enhances visualization. Cats typically have more intraabdominal fat than do dogs. inal viscera. Absence of intra-abdominal fat in emaciated or very young animals, or fluid accumulation in the peritoneal cavity, obscures serosal margins and causes poor radiographic visualization (Fig. 1). Gas within the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract may aid in identification of segments of the tract, but the presence of naturally occurring gas is inconsistent. Because of poor natural subject contrast in the abdomen, it is often useful to enhance radiographic visualization of organs or organ systems by administration of contrast materials at the time of examination. All contrast procedures should, however, be immediately preceded by survey radiographs so that the "current status" is known before the radiographic appearance is purposely altered. Contrast radiography of the gastrointestinal system is often essential to the thorough radiographic evaluation of a dog or cat with esophageal or gastrointestinal disease. INDICATIONS Gastrointestinal contrast radiography is indicated when diagnosis or an appropriate treatment cannot be determined from survey radiographs and other clinical information. For the purpose of radiographic contrast administration, the digestive tract can be divided into three segments: esophagus, stomach and small bowel, and large bowel. The contrast procedures most commonly employed to examine these three segments are the es~phago­ gram, the upper gastrointestinal series, and the barium enema\ It is CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 601 important to decide which segment of the patient's gastrointestinal tract is affected so that the most appropriate contrast proce.dure can be chosen. The affected segment usually can be Jetermined by careful evaluation of the history, clinical signs, and physical examination. Specific radiographic contrast procedures are therefore indicated by presenting signs of disease (Table 1). Many instances of gastrointestinal disease in pet animals are transient illness such as dietary indiscretion and other self-limiting conditions. Animals that are not severely ill and that have recent onset of clinical signs may best be treated symptomatically after the initial clinical examination. Abdominal radiography and especially gastrointestinal contrast procedures are generally reserved for chronic or persistent disorders. Radiography is indicated in the patient with recent onset of signs when those signs suggest serious or life-threatening disease. In the critical patient, it is often necessary to choose between contrast radiographic procedures and exploratory surgery. If survey radiographs of the abdomen show evidence of obstruction or perforation of the gastrointestinal tract or if there are other signs of imminent life-threatening disease, then immediate surgical exploration is indicated. If surgery is not justified, contrast radiographic procedures may be considered after medical stabilization of the patient. Table 1. CONTRAST PROCEDURE Indications for Gastrointestinal Contrast Radiography* INDICATIONS Esophagogram Dysphagia Regurgitation Presence of mediastinal mass on survey radiographs Unexplained presence of intraluminal esophageal gas on survey radiographs "Barium Burger" Persistent regurgitation with normal survey radiographs and esophagram Upper GI Series (Barium Series) Vomiting Small bowel diarrhea Melena Abdominal mass not completely defined by palpation or survey radiographs Suspected abdominal organ displacement Pneumogastrogram Demonstration of position of stomach Suspected gastric foreign body Double-Contrast Gastrogram Evaluatrion of gastric mucosa for ulceration, mass lesions Suspected radiolucent gastric foreign body Barium Enema Large bowel diarrhea Tenesmus Fresh blood in feces or on bowel movement Suspected intussusception Pneumocolon Demonstration of position of colon Screen for large bowel obstruction *When diagnosis or appropriate treatment cannot be deter~~;~ined by survey radiographs and other clinical information. 602 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS SELECTION OF CONTRAST AGENT Radiographic contrast procedures may be performed using positive (radiodense) or negative (radiolucent) contrast media. Negative contrast agents may be introduced into the gastrointestinal system by feeding effervescent materials (carbon dioxide) or introducing air by stomach tube or rectally. In veterinary radiology, the introduction of air by tube or catheter is most commonly used because it is inexpensive and does not require special materials or the voluntary cooperation of the patient. It should be remembered that naturally occurring gas produced by the digestive process affords a negative contrast and often facilitates visualization of the gastrointestinal tract on survey radiographs. Double-contrast radiographic procedures of the gastrointestinal tract are performed by instilling a small amount of positive contrast material into the stomach or colon and then distending the organ with a gas. Barium sulfate suspensions are used in these procedures because of their ability to adhere to mucosal surfaces. Double-contrast examinations allow excellent visualization of the barium-coated mucosa, making them ideal for detection of ulcers and other mucosal abnormalities. The most common gastrointestinal contrast procedures used in veterinary practice employ positive contrast media. These radiopaque media are administered orally, by stomach tube, or rectally to enhance radiographic visualization of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Positive contrast media can be divided into two major groups: barium sulfate preparations and oral organic iodine solutions. Barium is available as USP barium powder that is mixed with water to the desired consistency or as commercially prepared pastes or suspensions of microfine barium particles. Organic iodine media are available as liquid solutions (Gastrografin) or as powders (oral Hypaque) that require mixing with water. Commercially prepared barium suspensions are the best media for routine use in gastrointestinal contrast radiography. Barium sulfate is radiographically and physiologically superior to oral iodine solutions for use in the digestive tract (Table 2). The commercially prepared barium suspensions are better than USP barium because they stay in suspension and because they have coating agents that improve radiographic visualization of mucosal detail. 15 Media prepared from USP barium and water often flocculate or "clump" in the bowel as they come in contact with mucoproteins and as water is resorbed. The improved quality of the contrast study is well worth the small additional cost of commercially prepared suspensions. . Both barium and organic iodine preparations have disadvantages that must be considered under specific conditions. Barium preparations are highly irritating when released into the mediastinum or peritoneal cavity and cause a rapid and fulminating granulomatous inflammatory response. In cases in which perforation, laceration, or rupture of the digestive tract is suspected, oral organic iodine becomes the medium of choice for contrast radiography. Organic iodine is innocuous in body. cavities; it is absorbed and excreted through normal pathways, predominantly the urinary system. \. 603 CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT Table 2. Comparison of Barium Sulfate Suspensions and Oral Organic Iodines as Gastrointestinal Contrast Agents ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES LIQUID BARIUM SUSPENSIONS (Commercial Preparations) Very radiodense , provides excellent contrast Excellent mucosal coating Stays in suspension, not absorbed or diluted Relatively inexpensive Severe inflammation if released into body cavity Interferes at surgery Not removed from alveoli if inhaled ORAL ORGANIC IODINE SOLUTIONS Innocuous in peritoneal cavity or mediastinum Rapid transit through stomach and intestines Not as radiodense as barium Does not coat mucosa Hypertonic solution draws body fluid into gut lumen, dilutes the contrast further Expensive If no leakage of contrast is detected after administration of iodine but perforation is still suspected, then administration of barium may be considered. Studies in human patients have shown that small perforations or lacerations of the esophagus may go undetected on contrast radiographs using organic iodine solution but can be demonstrated with barium preparations that coat the mucosa to define small defects. 1• 4 • 14 The extremely irritating nature of barium in the peritoneal cavity is also a consideration when surgery must be performed immediately after contrast radiography. When barium is present in the gut, special precaution must be taken at surgery (enterotomy or resection) to avoid barium contamination of the serosal and peritoneal surfaces. The thick, viscous nature of barium suspension makes this a difficult and sometimes frustrating task. In most cases, contrast radiography is used for chronic conditions that do not require immediate surgery, but if a barium study does provide indication for surgery, the operation can be accomplished safely. Oral organic iodine contrast media are hypertonic solutions that cause water to move from other fluid compartments into the gut lumen. This fluid shift not only causes dilution of the iodine medium and loss of radiographic contrast but also may compound fluid and electrolyte imbalances in animals with vomiting or diarrhea. Healthy adult animals tolerate oral organic iodines well, but very young or marginally dehydrated animals may become severely dehydrated or experience hypovolemic shock after administration of these contrast media. These agents may also induce vomiting in some animals. The use of oral organic iodine solutions is contraindicated in dehydrated animals. Therefore, liquid barium suspension should be used for contrast radiography in dogs and cats with chronic or severe vomiting if a diagnosis cannot be made on survey radiographs. Barium has been shown to be the safest contrast agent in cases of intestinal obstruction. Controlled studies have shown that barium does not cause impaction in obstructed dogs. 11 \. 604 WILLIAM Table 3. R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS Contraindications for Administration of Gastrointestinal Contrast Media CONTRAST AGENT CONTRAINDICATION Barium Sulfate Preparations Suspected perforation, laceration, or rupture of esophagus, stomach, or intestine Oral Organic Iodine Solutions Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, or shock Barium or Iodine Clinical examination and/or survey radiographic findings adequate for diagnosis or indicative of need for immediate surgery In summary, the selection of gastrointestinal contrast medium is a matter of clinical judgment. The superior properties of commercially prepared barium sulfate suspensions make them the choice in most instances. It is important to remember that there are specific contraindications to the use of barium and oral iodine media (Table 3). TECHNIQUES AND COMPLICATIONS The information gained from contrast radiography depends on the quality of radiographs produced. Even an experienced radiologist cannot make an accurate interpretation from inadequate films . The technical quality of the examination is too frequently the limiting factor in contrast radiographic study of the digesitive tract. Careful attention must be paid not only to radiographic technique (MAS, KVP, use of grid, and so forth) and darkroom technique, but also to patient preparation, administration of contrast medium, patient positioning, and timing of the sequence of radiographs. Because many gastrointestinal contrast procedures require a significant investment of time and materials, care must be taken to ensure an examination of diagnostic quality. The opportunity to perform gastrointestinal contrast radiography is clearly a situation where one should follow the adage, "If it's worth doing, it's worth doing right." CONTRAST EXAMINATION OF THE ESOPHAGUS Esophagogram The esophagus is not visible on survey radiographs of normal dogs and cats because it is contained within the mediastinum, where it is in contact with other fluid-dense structures, and because there is no accumulation of gas in the normal esophagus. Contrast examination is indicated in cases of regurgitation or dysphagia when survey films show no esophageal abnormalities or inadequately define the extent or nature of an abnormality. Because it allows ready differentiation of e,c;ophageal and extra-esophageal masses, an esophagogram is also useful when a mediastinal mass is identified on thoracic radiographs. CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 605 The esophagogram is one gastrointestinal contrast procedure that is quick and easy to perform and does not require patient preparation. The most important technical aspect of an esophagogram is the selection of the proper contrast medium. When the contrast agent is swallowed, it moves rapidly as a bolus to the stomach before radiographs are made. The medium must coat the esophageal mucosa so that radiographs made 1 to 2 minutes after the swallow will allow visualization of the esophageal lumen. The best coating agent for routine studies is a thick barium paste. Barium pastes are commercially available as "esophageal paste" or "esophageal cream" and are usually provided in tubes that allow easy administration (Esophotrast). A small amount (1 tsp to 1 tbsp) of barium paste is placed in the mouth and patient is allowed to swallow. (If a fluoroscope is available, the barium should be administered with the patient in l!J.teral recumbency so that the progression of the bolus can be observed directly to evaluate the dynamics of the swallowing reflex.) Lateral and ventrodorsal radiographs of the cervical region and thorax are made 1 to 2 minutes after administration of the barium . Slight oblique positioning of the ventrodorsal projection may avoid direct superimposition of the thoracic spine and the esophagus. Radiographs should be made promptly because swallowed saliva will soon wash away the barium coating. The normal canine esophagogram appears as linear streaks extending the length of the esophagus as barium coats the crypts formed by longitudinal mucosal folds. (Fig. 2) In cats, esophageal contrast shows the linearstreaked pattern in the cranial two thirds of the esophagus but shows transverse-oblique striations in the caudal esophagus (Fig. 3). There are two normal variants that should be recognized as such to avoid misinterpretation: (1) an irregularity of the linear pattern at the thoracic inlet of dogs caused by redundant mucosal folds, which should not be mistaken for a pathologic dilatation (Fig. 4A); and (2) a barium bolus radiographed in Figure 2. Normal canine esophagogram in lateral (A) and ventrodorsal (B) projections. Linear !treaks of barium paste extend the length of the esophagus. 606 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER. JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS Figure 3. Normal feline esophagogram in lateral (A) and ventrodorsal (B) projections. The transverseoblique striations in the caudal third of the esophagus are a normal feature in cats but are not always seen as prominently as in this example. mid-swallow (Fig. 4B). Residual barium paste in the mouth may occasionally be formed into a bolus and swallowed after the initial swallow. This second bolus may, by chance, be swallowed just as a radiographic exposure is made. The resultant "stop-action" picture of the barium bolus should not be mistaken for dilatation. The differentiation can be made by repeat radiography; a bolus will no longer be present but a true dilatation will persist. Figure 4. Common variants in the appearance of normal canine esophagograms which may be mistaken for pathologic lesions. A, Redundant mucosal folds at the thoracic inlet caused by ~xion of the neck during radiography. B, A bolus of barium radiographed in mid-swallow; the hoi s was not present on repeat radiographs. CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 607 If the esophagus is dilated, contrast material will accumulate within the lumen and a single swallow of barium may not fill the lumen adequately for assessment of the extent of dilatation. In such cases, liquid barium suspension may be administered orally to fill the dilated esophagus. As noted earlier, oral iodine solution should be used in lieu of barium if perforation of the esophagus is suspected. If the iodine study shows no evidence of contrast leaking into the mediastinum, then a repeat study with barium paste may be performed in an attempt to identify small mucosal perforations or lacerations. 1• 4 The esophagogram is a safe procedure. The only complication of consequence occurs when barium enters the mediastinal space through an unsuspected perforation. Dysphagic dogs and cats may aspirate orally administered media but because the paste is thick and volume is small, the aspirated barium usually coats only the trachea and is removed by ciliary action and coughing. "Barium Burger" "Barium burger" is a term used to describe an esophagogram using barium mixed with solid food as the contrast agent. This procedure is indicated when both survey radiography and a conventional esophagogram fail to demonstrate an abnormality in a patient with dysphagia or regurgitation. A dysfunctional esophagus may allow passage of liquid but not solid foods. In these cases an esophagogram using barium paste may show a normal pattern, but the barium burger technique will demonstrate the accumulation of food in the esophagus. The procedure is simple. A small amount of barium paste or liquid barium suspension is mixed with canned dog food; the food should maintain its solid consistency. As animals with chronic swallowing disorders are undernourished and often have a ravenous appetite, most animals will eat the food voluntarily, but the mixture can be forced-fed if necessary. Lateral and ventrodorsal radiographs of the cervical and thoracic regions are made immediately after the patient consumes the barium-food mixture (Fig. 5). Figure 5. Esophagograms made using barium cream (A) and liquid barium mixed with canned dog food (B) in a dog that presented with persistent regurgitation. The barium-food mixture ("barium burger") demonstrated dilatation not seen on a conventional esophagogram. 608 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS CONTRAST EXAMINATION OF THE STOMACH AND SMALL BOWEL Upper GI Series The upper GI series is also commonly known as the barium series and is the standard contrast procedure for evaluation of the stomach and small bowel. The stomach is filled with positive contrast material and sequential radiographs are made to observe gastric emptying and the small bowel follow-through. The upper GI series allows evaluation of the size, shape, mucosal pattern, and position of the stomach and intestines and, by employing sequential radiographs, allows assessment of progression of material through the gastrointestinal tract. The upper GI series is indicated when there are signs of gastric or small bowel disease (most often persistent or recurrent vomiting or diarrhea) that cannot be diagnosed by survey radiography and other clinical information. The procedure may also be used to establish the position of the gastrointestinal tract in animals without digestive disorders but with the possibility of abdominal masses or hernias. A good quality upper GI series requires careful planning and preparation. Fortunately, the procedure is usually indicated for chronic conditions and can be scheduled in advance. The patient should be fasted for 12 to 24 hours to allow emptying of the stomach and small intestine. Water should be withheld for l to 2 hours before radiography to avoid the collection of a large volume of fluid in the stomach at the time of administration of the contrast material. Laxatives may be administered but are not essential if a 24-hour fast is enforced. Enemas should be administered prior to the examination to ensure removal of all residual ingesta from the colon. This is best accomplished by a series of large-volume warm water enemas. Hypertonic enema solutions in disposable applicators usually do not provide the thorough evacuation necessary. Cleansing of the large bowel should be performed at least l to 2 hours before radiographic examination to allow expulsion of the gas and fluid that are typically present just after administration of enemas . To ensure proper preparation it is often prudent to hospitalize the patient the day before the upper GI series is scheduled. The fast is best enforced under hospital supervision, and enemas can be administered on the evening before and the morning of the contrast examination. Survey radiograp9s should always be made immediately before administration of the contrast medium, even if the abdomen has been recently radiographed. These films allow verification of patient preparation and provide a record of the "natural state" for comparison ~ith films made after administration of the contrast agent. If ingesta are present in the gastrointestinal tract, the contrast procedure should be delayed for further preparation. Giving barium to an animal that has recently eaten rarely results in a study of diagnostic quality and further delays the opportunity to begin an adequate study. Occasionally the preliminary radiographs may yield diagnostic information that obviates the need for the contrast study. Commercially prepared liquid barium suspension (Novopaque, Redipaque) is the best contrast medium for an upper GI series unless a CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 609 perforation of the stomach or intestine is suspected. Barium suspension can be administered orally or by stomach tube. Most dogs and cats will accept barium orally from a dose syringe. The patient's head is held in an elevated position and barium is placed in the cheek pouch. The proper dose rate for liquid barium suspension is 13 ml per kg (6 cc per lb or 1 oz per 5 lb). Administration of the full dose is essential to the overall quality of the procedure. The initial dose of barium should distend the stomach to allow visualization of its size and shape and to stimulate gastric emptying. The goal of a good-quality barium series is to have a broad, continuous ribbon of barium emptied into the duodenum and jejunum. If a gastric foreign body is suspected but not seen on survey radiographs, an initial dose of only 10 to 20 cc of barium should be administered in an attempt to coat the foreign body and to avoid obscuring it in a dense pool of barium. Dorsoventral, ventrodorsal, and left and right lateral radiographs ar~ taken immediately. If no foreign body is seen then a full dose of barium is given and the procedure is continued. . The timing of sequential radiographs is another important feature of the upper GI series. Exposures should be made frequently during the first hour to observe the stomach, gastric emptying, and the proximal small bowel. After the first hour, the intervals may be increased but the study should be followed until the barium column reaches the descending colon. A typical film sequence is listed below, but clinical judgment should determine the exact sequence of radiographs for each patient. Typical Film Sequence for Upper GI Series Immediate 1 hour 15 minutes 2 hours 30 minutes 4 hours (2 radiographic projections at each time) If gastric emptying is obviously delayed, then the interval between early films can be increased; if transit through the bowel is more rapid than expected, the intervals can be shortened. An upper GI series should ideally be started in the morning to allow time to follow the procedure to conclusion. Several factors may affect gastrointestinal motility, gastric emptying, and small bowel transit time. Antiemetic and antidiarrheal drugs exert a potent effect on gastrointestinal motility and, when possible, should be discontinued 48 to 72 hours before an upper GI series is attempted. Remember also that sympathetic stimulation (the "fight or flight" response) dramatically decreases gastrointestinal motility. Gastric emptying and small bowel transit are very slow in a frightened or enraged animal. For this reason, it is especially important to be patient, gentle, and quiet when administering barium or positioning a dog or cat for gastrointestinal contrast radiography. General anesthetics and many sedatives and narcotics decrease gastrointestinal motility. An upper GI series is best performed with no chemical 610 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS restraint, but mild sedation cannot be avoided in some fractious animals. An unmanageable patient not only is difficult to position for radiography but is almost certain to experience intense sympathetic stimulation. When chemical restraint is required, we consider acepromazine maleate to be the sedative of choice. Of the commonly available tranquilizers, it has been shown to have the least effect on gastrointestinal motility. 14 Positioning of the patient is an important factor in performing an upper GI series. The barium suspension used for contrast is a liquid and seeks the lowest level in the stomach. Barium fills and distends the gastric fundus when the patient is placed in left lateral recumbency. The pylorus is filled in the right lateral recumbent radiograph. Similarly, the fundus is best outlined in the dorsoventral projection (Fig. 6). If gastric disease is suspected, radiographs should be made in dorsoventral, ventrodorsal, left lateral and right lateral projections immediately after contrast administration for optimal evaluation of the barium-filled stomach. Dorsoventral and right lateral projections should be made at each interval during the upper GI series. These projections favor visualization of the pyloric antrum and proximal duodenum and allow best assessment of gastric emptying. A common error in gastrointestinal contrast radiography is failure to take an adequate number of films. Figure 7 is a typical normal upper GI series in a dog. When the stomach is well distended with barium, gastric emptying is stimulated. The Text continued on page 614 Figure 6. Radiographic appearance of a barium-filled stomach with the patient positioned for right lateral recumbent (A), left lateral recumbent (B), dorsoventral (C)~ · and ventrodorsal (D) projections. Barium flows to the dependent portion of the stomach. Ro tine use of right lateral and dorsoventral projections allows best assessment of the pyloric an rum and gastric empyting. AIHour projections should be obtained for thorough evaluation of the stomach. CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 611 Figure 7. Upper GI series (barium series) in a healthy adult dog shows a typical film sequence and progression of barium through the gastrointestinal tract. A and B, Survey abdominal radiographs are always made immediately before contrast examination. C and D, The stomach is distended with liquid barium immediately after administration. Illustration continued on following page 612 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER. JR. AND jAN E. BARTELS Figure 7 (Continued) . E and F, After 15 minutes the stomach and duodenum are well visualized. G and H, After 30 minutes a continuous barium column fills the duodenum and jejunum as the stomach empties. · Illustration continued on opposite page CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 613 Figure 7 (Continued). I and J, After 1 hour the leading edge of the barium column has reached the colon. Most of the barium has been emptied from the stomach. K and L, After 2 hours much of the barium has entered the colon as barium passes through the small bowel. A small amount of residual barium coating the gastric mucosa is a common occurrence. Illustration continued on following page 614 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER. JR. AND jAN E. BARTELS Figure 7 (Continued). M and N, After 4 hours barium has cleared the small bowel. exact time of gastric emptying varies but can be considered normal if there is steady and uninterrupted progression of barium into the small bowel. The intestine should appear as a continuous radiodense ribbon. The duodenum is filled at 15 to 30 minutes. Much of the jejunum is filled at 1 hour, at which time there are many superimposed loops of bowel. The leading end of the barium column usually reaches the cecum in 1Vz to 2 hours and much of the barium has entered the colon within 3 to 4 hours. As noted above, a number of factors may affect the gastric emptying and small bowel transit time. The uniform progression of barium through the tract is a more important criterion of normal gastrointestinal motility than is the exact transit time. In cats gastric emptying and transit time are more rapid, with barium reaching the colon within 30 to 60 minutes (Fig. 8). 9 The stomach and intestines are in constant motion in the resting animal. Gastric and intestinal movement can be observed fluoroscopically but when a fluoroscope is not available, sequential radiographs allow assessment of gastrointestinal dynamics. It is important to remember that the films of an upper GI series represent a series of "stop-action" views of a dynamic system. Figure 9 shows the varying shape of a dog's stomach in three sequential radiographs. Annular contractions constantly progress from the body of the stomach to the pylorus. The different shapes of the stomach on sequential films occur because the "stop-action" views catch the contractions in different regions of the stomach. True anatomic abnormalities cause either changes in the shape of the gastric or intestinal wall or loss of contractility which will persist on sequential radiographs (Fig. 10). If the progression of barium to the large bowel is delayed or if no diagnostic radiographic signs are observed in the first 4 hours, the examination should be continued until all barium has cleared the small bowel. In such cases it is useful to make a final radiographthe next morning (18 to 24 hours after administration of barium). The delay~d radiograph may Text continued on page 618 CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE Tl\ACT 615 Figure 8. Liquid barium suspension progresses more rapidly through the gastrointestinal tract in cats than in dogs. A, Radiograph made 30 minutes after barium was given to a cat. Notice that barium has already filled the ascending colon. This radiograph also demonstrates two other characteristic features of the upper GI series in cats: the J-shaped stomach with acute angulation of lesser curvature and position of pylorus near the midline; and the "string of pearls" appearance of the duodenum created by multiple segmental contractions. B, After 90 minutes most of the barium has reached the colon. Notice that the cecum in the cat is nonsacculated and appears as the tapered blind end of the ascending colon. 616 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS Figure 9. A to C, Sequential radiographs of an upper gastrointestinal series in a dog. The stomach is constantly contracting during gastric empyting. The shape of the stomach depends on the stage of contraction at the instant of radiographic exposure. These normal annular contractions should not be mistaken for mass lesions of the gastric wall. ONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 617 Figure 10. Sequential radiographs of an upper gastrointestinal series at 10 minutes (A), 5 minutes (B), 30 minutes (C), and 45 minutes (D). Notice the asymmetric indentation at the 1teral aspect of the pyloric sphincter. True anatomic abnormalities are distinguished from ormal contractions by asymmetry and by persistence on sequential films. The lesion in this xample was a benign neoplasm. Notice.that there was pyloric outflow obstruction and that ~e dog vomited tbe barium between the 30- and 45-minute films. 618 • WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND JAN E. BARTELS Figure 11. Radiographs from an upper gastrointestinal series of a dog with signs of gastrointestinal obstruction. A, Thirty minutes after administration of barium, contrast medium is seen emptying into the small bowel. B, At 6 hours distended bariumfilled gut loops characteristic of obstructive disease are seen but the site of obstruction cannot be identified. C, On delayed radiograph at 20 hours (the next morning) the barium clearly outlines an ileocolic intussusception in the cranial ventral abdomen. show residual accumulation of barium in an absorbent foreign body (such as a cloth or sponge) or may define a lesion in the distal small bowel or colon not seen on earlier films (Fig. 11). One should realize that upper GI studies frequently show no abnormalities. Many cases of chronic vomiting or diarrhea are caused by metabolic disorders that do not cause anatomic abnormalities or dynamic changes detectable by contrast radiography. Even when lesions are detected by radiography, specific etiologic diagnosis may not be possible. Observation and biopsy by endoscopy or laparotomy are often required for definitive diagnosis. Although an upper GI series does not often provide a final diagnosis, it does answer many significant questions: Is an anatomic lesion present? Is the lesion mucosal, infiltrative, or extraluminal? Is the condition obstructive or nonobstructive? Complications resulting from an upper GI series are rare. Barium leaking into the peritoneal cavity through an unsuspected perforation of the stomach or small bowel is a potentially serious sequela. Aspiration of barium can occur when it is being administered orally or when vomiting occurs after administration. Barium in the trachea and bronchi is of little consequence, as it is removed by the natural action of cilia and the cough reflex (Fig. 12A). In fact, barium is sometimes used purposely in performing bronchograms. If barium reaches the alveoli, however, it cannot be removed or absorbed and forms a local granulomatous reaction (Fig. 12B). If only a small portion of lung is involved, the residual barium may cause no harm (Fig. l2C). If a large volume of lung is flooded by!njstaken placement of a stomach tube or aspiration of a large volume of barium, respiration may be compromised sufficiently to cause permanent disability or death. CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 619 Figure 12. A , Barium aspirated into the trachea and mainstem bronchi does not cause adverse sequelae. It is removed by ciliary action and coughing. B, Barium aspirated into the alveoli is trapped and causes a granulomatous reaction but ·is usually not fatal if only a small portion of lung is affected. C, Residual barium granulomas caused by aspiration during an upper GI series 5 years earlier; this is an incidental finding not associated with clinical signs. In summary, the upper GI series is a safe and effective diagnostic procedure but one that requires careful planning and attention to proper technique. The most important (and most often overlooked) technical factors of a good barium series are as follows: Prepare the patient well; cleanse the gastrointestional tract. Use commercially-prepared liquid barium suspension. Administer enough barium to distend the stomach. Take an adequate number of radiographs. Follow the study until a diagnosis is made or until barium clears the small bowel. Pneumogastrogram A pneumogastrogram is performed simply by distending the stomach with air. No sedation or anesthesia is required. A stomach tube is passed and air is administered by dose syringe or with a bulb inflator until there is slight abdominal tympany. Radiographs are made with the patient in ventrodorsal, dorsoventral, and left and right lateral positions. A pneumogastrogram can be quickly and inexpensively performed as a screening procedure for gastric foreign bodies or simply to identify the size, shape, and position of the stomach (Fig. 13). Negative contrast techniques do not allow good visualization of mucosal detail. 620 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, }RAND }AN E. BARTELS A Figure 13. Lateral survey abdominal radiograph (A) of a dog showing an ill-defined mineral density in the cranial ventral abdomen. A subsequent pneumogastrogram (B) shows that the density is a gastric foreign body (bone) in the pyloric antrum. The stomach was inflated with air by orogastric intubation. Double-Contrast Gastrogram The double-contrast gastrogram is indicated for careful evaluation of the gastric mucosa. It should be considered when mucosal ulcerations or mass lesions (neoplastic or inflammatory) of the gastric wall are suspected, or when an upper GI series is indeterminate in animals with chronic vomiting or hematemesis. The patient must be prepared for radiography in the same manner described for an upper GI series. Because the double-contrast study is not used to evaluate motility, the animal may be sedated for the examination. A stomach tube is passed and 1.1 to 3.3 ml per kg (0.5 to 1.5 cc per lb) of barium suspension is administered and followed by a sufficient quantity of air to distend the stomach. Just prior to administration of the contrast material, glucagon may be given intravenously to induce hypotonicity and hypomotility of the stomach and intestines. 2• 3 The distended stomach should be radiographed in multiple positions to complete the study. Radiographic projections should include at least the four standard gastric views and a left dorsal oblique view. CONTRAST EXAMINATION OF THE LARGE BOWEL Barium Enema The dog and cat both have a simple large bowel which may be divided into the cecum; the ascending, transverse, and descending colon; and the rectum. Large bowel disease is not common in small animals, but when it occurs a barium enema is the radiologic examination of choice. Diseases of the colon can rarely be identified on survey radiographs, and an upper GI series does not usually allow adequate evaluation of the colon. Barium that has progressed from the stomach is often desiccated to a semisolid state when it reaches the descending colon and do~ot provide good mucosal detail. The barium enema examination is indica d in cases of large bowel diarrhea, suspected intussusception, and tenesm s or rectal bleeding when CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 621 a diagnosis cannot be made from survey radiographs and other clinical information. Endoscopy is also an important technique in the evaluation of large bowel disease. The cecum and the ascending and transverse portions of the colon are often inaccessible to examination with rigid endoscopes, but flexible fiberoptic endoscopes allow visualization of the entire large bowel. Barium enema examination and endoscopy may be used as complementary procedures for thorough evaluation of the colon. Stringent preparation of the colon is essential for both endoscopic examination and barium enema. More thorough cleansing is necesssary for this examination than for the upper GI series; all residual food material should be removed from the large bowel, so the animal should not be fed for at least 24 hours. Laxatives may be administered the day before and an enema performed the evening before the examination. One to two hours before the barium enema examination, repeated enemas should be given until no additional food material is expelled. General anesthesia is required for performing an adequate barium enema examination. Awake or midly sedated animal patients cannot be expected to cooperate when distention of the colon by barium initiates the defecation reflex. Even if the patient can be physically restrained and barium contained within the large bowel, there will be reflex contractions of the colon which make interpretation of the contrast study difficult. Survey radiographs should be obtained immediately before induction of anesthesia to verify adequate preparation of the colon and to provide baseline films for the contrast examination. If residual ingesta are present in the colon, then further preparation is required. The contrast medium of choice for retrograde large bowel examination is the liquid barium suspension used for the upper GI series diluted 1:1 with warm water in an enema bag. Disposable plastic enema bags are ideal for use in the barium enema procedure and are available as a prepackaged unit with bag, plastic tube, tube clamp, and rectal catheter. When the barium mixture is prepared, the enema bag is suspended from an intravenous stand. Barium is allowed to fill the tube so that air is displaced from the system. A rectal catheter with inflatable cuff is placed in the patient's rectum, and the cuff is gently inflated to lock the catheter into the pelvic canal. Barium is administered by gravity flow at a dose of 11 to 13 ml per kg (5 to 15 cc per lb). The exact dose is difficult to ascertain because the diseased colon is often less distensible than normal and will accept a lower volume of fluid . Ideally, the barium is administered under fluoroscopic control so that the inflow of contrast medium can be observed and discontinued when barium reaches the cecum. It is importaqt that barium not be forced into the small bowel because contrast-filled small bowel loops overlying the colon create an objectionable artifact on subsequent radiographs. In most veterinary practices a fluoroscope is not available. Under such conditions, it is wise to administer barium at 11 ml per kg (5 cc per lb) and then make a single ventrodorsal scout radiograph to evaluate the degree of filling. If the colon is not completely filled then additional barium can be administered. • Once the colon is filled with barium, radiographs should be exposed in the left lateral, ventrodorsal, and left and right ventrodorsal-oblique 622 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND JAN E. BARTELS Figure 14. Lateral (A), ventrodorsal (B), right ventrodorsal oblique (C), and left ventrodorsal oblique (D) radiographic projections of a barium enema in a healthy adult dog. The cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, and descending colon can be identified. A small amount of barium has refluxed into the terminal ileum. The redundant fold in the descending colon is a normal variant. The right ventrodorsal oblique projection allows full visualization of this fold, which is not well seen in the other projections. Note the smooth mucosal margins of the colon. CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 623 projections (Fig. 14). The multiple projections show various profiles of the colon and aid in locating. filling defects and irregularities of the colon wall. The colon of the dog and cat is simple and nonsacculated, and exhibits a smooth mucosal lining. Typically the overall shape is that of a shepherd's crook, but additional flexures or folds may be present in many normal animals. It is common for a reflex segmental contraction to be present just cranial to the tip of the catheter and inflatable cuff. Once the radiographs are developed and it is determined that no retakes are necessary, barium may be emptied from the colon by removing the enema bag from the intravenous stand and placing it below the level of the radiographic table to allow barium to flow from the colon back into the bag. A double-contrast procedure may then be performed. If doublecontrast examination is desired, care should be taken to remove as much of the barium from the colon as possible by elevation of the dog's forequarters and gentle palpation of the colon. Air is then insufflated into the colon through the rectal catheter to provide moderate distention of the colon. Left lateral, ventrodorsal, and left and right ventrodorsal oblique radiographs are made. Radiographs made with double contrast show excellent mucosal detail with barium coating the mucosa of the air-filled colon (Fig. 15). Figure detail. The in a profile coating (B), 15. The double-contrast barium enema procedure enhances visualization of mucosal normal canine colon mucosa is smooth and regular. The barium coating appears as a fine straight line (A). Mucosal irregularities cause spiculation of the barium as seen in this double-contrast study of a dog with severe ulcerative colitis. 624 WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS In the procedures described above, the terminal (intrapelvic) colon and rectum cannot be evaluated because of the presence of the rectal catheter and inflatable cuff. If intrapelvic disease is suspected, the catheter and cuff should be removed before the positive contrast radiographs are made. If the colon has not been overfilled and the catheter is removed gently, barium will not be expelled. In puppies, kittens, and debilitated animals, which cannot be generally anesthetized, some information can be gained by instilling barium directly into the rectum and colon with a dose syringe. Careful planning and attention to technique are necessary to achieve a barium enema examination of optimal quality, but when indicated the study can provide excellent diagnostic information. It has proved most useful in differentiation of mucosal and transmural disease of the colon and in evaluation of intussusception, cecal inversion, large bowel neoplasia, and strictures. Serious complications from the barium enema procedure occur when there is perforation of the large bowel. If the clinical examination suggests rupture, tear, or perforation of the rectum or colon, then barium sulfate preparations should not be administered. Since the colon is distended with barium in the barium enema, it is almost certain that barium will be forced into the peritoneal cavity if a perforation is present. Water-soluble organic iodine contrast medium may be administered rectally to evaluate the integrity of the large bowel. Care must also be taken to avoid iatrogenic perforation of the colon or rectum during the procedure. The rectal catheter should be lubricated and inserted gently. It is also important that the inflatable catheter cuff be distended only enough to lock the catheter snugly into the pelvic canal. Overinflation of the cuff may cause a colon or rectal tear, especially if the tissue is diseased or devitalized. The barium enema examination is often used in conjunction with endoscopy, during which biopsy samples of the colonic mucosa and of intraluminal lesions may be taken. The biopsy procedure is often essential to definitive etiologic diagnosis, as radiographic examination and gross visualization of the colon allow only description of the extent and nature of the lesions. Many sources warn that a barium enema should not be performed for 3 to 4 days after colonic biopsy to avoid the possibility of extraluminal extravasation of barium at the site of biopsy. This creates practical problems in veterinary medicine since the patient must be anesthetized for both the endoscopic examination and barium enema. The endoscopic examination cannot be performed immediately after a barium enema because the barium obscures visualization of the colon mucosa. If 4 days are allowed to elapse between endoscopic examination and barium enema then the animal must be generally anesthetized twice, causing increased risk for the patient, a greater investment of time in diagnostic procedures, longer hospitalization time, and increased client expense. We have found that the barium enema can be safely performed immediately after endoscopic examination and biopsy when such biopsies are superficial and made with small biopsy forceps under fiberoptic visualization. No CONTRAST RADIOGRAPHY OF THE DIGESTIVE TRACT 625 A Figure 16. Normal pneumocolon. Lateral (A) and ventrodorsal (B) radiographs of the abdomen made after rectal instillation of air. The cecum and all segments of the colon can be identified. extravasation of barium has been observed under these conditions and no adverse sequelae have occurred. Pneumocolon The pneumocolon is a safe and easy procedure that can be used to ascertain the position of the colon when its location cannot be determined from the presence of gas or ingesta on survey radiographs, and as a screening procedure for large bowel obstructive disease. The procedure does not require anesthesia or sedation. A 30- or 60-cc syringe is used to instill air directly into the rectum and colon. The tip of the syringe is placed in the anus and the front of the syringe barrel is pressed against the anus to form a seal. Approximately 11 ml of air per kg body weight (5 cc per lb) is usually adequate to yield moderate distention of the colon. Ventrodorsal and left lateral radiographs are made immediately, before the air is expelled (Fig. 16). This technique does not allow visualization of mucosal irregularities, but intraluminal masses or strictures of the large bowel can often be located. Assessment of the nature and etiology of the lesion requires further diagnostic procedures such as barium enema, endoscopy, or laparotomy. REFERENCES 1. Dodds, W. J., Stewart, E. T., and Vlymen, W. J.: Appropriate contrast media for evaluation of esophageal disruption [Opinion]. Radiology, 144:439, 1982. 2. Evans, S. M., and Biery, D. B.: Double contrast gastrography in the cat: Technique and normal radiographic appearance. Vet. Radiol., 24:3, 1983. 3. Evans, S. M., and Laufer, I. : Double contrast gastrography in the normal dog. Vet. Radiol., 22:2, 1981. 4. Foley, M. J., Ghahremani, G. G., and Rogers, L. F.: R~appraisal of contrast media used 626 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. WILLIAM R. BRAWNER, JR. AND }AN E. BARTELS to detect upper gastrointestinal perforations: Comparison of ionic water-soluble media with barium sulfate. Radiology, 144:231, 1982. Gomez, J. A.: The gastrointestinal contrast study. VET. CLIN. NORT!l AM.: SMALL ANIM. PRACT., 4:805, 1974. Guffy, M. M.: Radiography of the gastrointestinal tract. VET. CLIN. NORTH AM.: SMALL ANIM. PRACT., 2:105, 1972. Kleine, L. J. : Radiologic examination of the esophagus in dogs and cats. VET. CLIN. NORTH AM.: SMALL ANIM. PRACT., 4:663, 1974. Morgan, J. P.: The upper gastrointestinal tract in the cat: A protocol for contrast radiography. Vet. Radiol., 18:134, 1977. Morgan, J. P.: The upper gastrointestinal examination in the cat: Normal radiographic appearance using positive contrast medium. Vet. Radiol., 22:159, 1981. Morgan, J. P., and Silverman, S.: Techniques of Veterinary Radiography. Davis, California, Veterinary Radiology Associates, 1982, part F II. Nelson, S. W., Christoforidis, A. J. , and Roenigk, W. J. : Barium suspensions vs. watersoluble iodine compounds in the study of obstruction of the small bowel. Radiology, 80:252, 1963. Nyland, T. E., and Ackerman, N. : Pneumocolon: A diagnostic aid in abdominal radiography. Vet. Radiol., 19:203, 1978. O'Brien, T. R.: Radiographic Diagnosis of Abdominal Disorders in the Dog and Cat. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders Company, 1978, chapters 6 to 9. Root, C. R. : Contrast radiography of the alimentary tract. In Ticer, J. W. (ed.): Radiographic Technique in Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders Company, 1975. Root, C. R., and Morgan, J. P.: Contrast radiography of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the dog: A comparison ofmicropulverized barium sulfate and U.S.P. barium sulfate sulfate suspensions in clinically normal dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. , 10:279, 1969. Vessal, K., Montali, R. J., Larson, S. M., et al.: Evaluation of barium and Gastrografin as contrast media for the diagnosis of esophageal ruptures or perforations. Am. J. Roentgenol., 123:307, 1975. Zontine, W. J.: Effect of chemical restraint drugs on the passage of barium sulfate through the stomach and duodenum of dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc., 162:878, 1973. Department of Radiology School of Veterinary Medicine Auburn University Auburn, Alabama 36849