Resilience & Academic Achievement in Minority Students

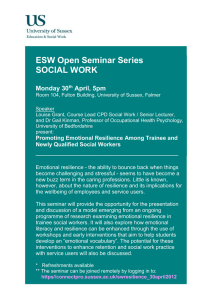

advertisement