On the reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society

advertisement

Source:

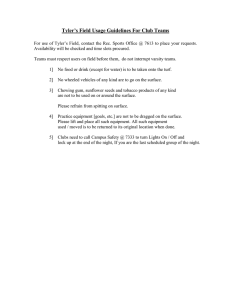

Journals Collection, Juta's/Acta Juridica (2000 to date)/Acta Juridica/2015 A transformative justice: Essays in honour of Pius Langa/Part III Reflections on themes in

Justice Langa's judgments/Articles/On the reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society

URL:

http://jutastat.juta.co.za/nxt/gateway.dll/jelj/acta/3/150/168/169/176?f=templates$fn=default.htm

On the reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society

2015 Acta Juridica 374

Stu Woolman*

And I'm driving a stolen car, down on Eldridge Avenue.

Each night I wait to get caught, but I never do.

She asked if I remembered the letters I wrote, when our love was young and bold.

She said last night she read those letters: and they made her feel one hundred years old.

I'm driving a stolen car, on a pitch black night, and I'm telling myself – I'm gonna be alright.

But I ride by night, and I travel in fear, that in this darkness, I will disappear.

Bruce Springsteen 'Stolen Car' The River

The reciprocal relationship between a robust rule of law culture and a truly civil, civil society is much like the relationship between the characters in

this song. Neither can subsist, meaningfully, without the other. When it works, the bond is bold. When the connection falters, no easy

rapprochement exists. How to create both – and the union between them – ab initio? That's a big ask. But it's a complex endeavour worth

undertaking. The success of South Africa's democratic project rests upon its realisation. Fail: and into that darkness, we shall disappear.

Section 1(c) of the Constitution refers to the '[s]upremacy of the constitution and the rule of law' as some of the values that are

foundational to our constitutional order. The first aspect that flows from the rule of law is the obligation of the state to provide the

necessary mechanisms for citizens to resolve disputes that arise between them. This obligation has its corollary in the right or entitlement of

every person to have access to courts or other independent forums provided by the state for the settlement of such disputes. The obligation

on the state goes further than the mere provision of the mechanisms and institutions referred to above. It is also obliged to take reasonable steps,

where possible, to ensure that large­scale disruptions in the social fabric do not occur in the wake of the execution of court orders, thus

undermining the rule of law.

Chief Justice Pius Langa,

President of the Republic of South Africa and Others v Modderklip Boerdery

2015 Acta Juridica 375

I Catch and release

I stopped at a red traffic light the other night.

Remarkable? Well, yes, given the sketchy part of Johannesburg that I was driving through that evening. Under normal circumstances, with no

cars crossing my path from any direction, I would have rolled that light. To be sure, I will do so again in the future. Life here is a moveable

feast. And one either moves or is moved.

But not that night, and not at that light.

'Why?' I asked myself, as I stopped and waited for the green robot to grant permission to proceed. What had broken my pattern of non­

compliance with the law in circumstances where I knew that the law would likely be of little or no assistance?

Three recent experiences.

Three times during a two week period in late October 2013, Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Department Officers (JMPD) directed me to

stop and to pull over. I had not trespassed. On the first occasion two officers walked up to my car. They asked for my licence, and they

checked the validity of my disc. After noting my driver's licence was about to expire, and giving me a friendly exhortation to get it sorted out,

they sent me on my way.

The following evening, at the exact same spot, another officer pointed at me and asked me to pull over. She approached from behind the left

side of my car, looked at the licence disc, said hello to my partner's two schnauzers and asked their names ('Ernie' and 'Ernestina'). She wished

me, and the dogs, a good evening.

A week and change later, after being waved through four different catchment zones, a JMPD patrol car pulled me over on the M1 just before

the Corlett Drive off ramp. They noted the manner in which my licence plate was affixed to the rear of my car. Duct tape: it had been knocked

loose by an overzealous taxi driver a day earlier. They checked my disc. Fine. They asked for my licence. This document I had absent­mindedly

left in my wallet at my partner's home in Melville. The officers were not impressed. A call to my partner likewise failed to convince. Then an

inspired moment! My publisher had just sent me additional copies of my recent monograph – The Selfless Constitution. The box lay in the trunk. I

exited the car, opened the boot and tore open the parcel. I turned to the inside back cover. It contains a photograph of me and a short bio –

including my current station in the world. The officer took it all in. He said: 'You're a big man – a university professor.' I said: 'No! You are a big

man – you enforce the law! I just write about it.' With that proof of my identity established, and our mutual admiration confirmed, he and his

partner bid me 'adieu'. Or more likely, since the emotions didn't quite rise to Casablanca heights, I received a handshake and a 'Shap, shap'.

2015 Acta Juridica 376

When I rehearsed the entire set of experiences to my partner – a sociologist who has had the opportunity to engage and to study the police

first hand – she noted that recent studies have found that when individuals have two or more positive experiences with law enforcement

officials, they tend to have a more favourable view of the police (as well as courts and other agents of the state.) It therefore occurred to me

that my recent civil engagement with local constables had, in all likelihood, led me to obey the law – at a red robot on a pitch black night in Alex

– when others might not have done so when similarly situated.

The remainder of this article provides a theoretical framework for what occurred over that month and draws its power from a number of

related disciplines (ie, sociology, social psychology, political theory, ethics and political science). Part II engages the four master narratives that

inform our understanding of the rule of law in South Africa today. It suggests how they remain incomplete and require supplementation. Part III

develops the primary thesis of this article: that a reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society must be developed if the

manifold aspirations of our constitution are ever to be realised. Given the difficulties of moving from an authoritarian apartheid regime to a polity

grounded in a substantive notion of the rule of law, the remedies on offer are invariably incomplete. Part IV introduces Tom Tyler's procedural

fairness account of the rule of law: namely, that citizens consider the state 'legitimate' if the institutions which govern society treat citizens

equally, irrespective of the outcome in a given matter or most matters. Tyler has vetted this thesis, after beginning in Chicago, around the

world. Not surprisingly, while procedural fairness is undoubtedly nice to have, it does not account for what citizens in other nations deem to be

critical for the realisation of a rule of law culture in a legitimate state. Some societies emphasise common mores. Others societies stress the

efficacy of bureaucratic administration. No two countries and no two domains are alike – and none cleave to the rather arid conception Tyler

developed 25 years ago. Part V brings us back to South Africa – and the sociological studies carried out in that last few years on what South

African citizens believe the rule of law to require. It first demonstrates how the rule of law, when inextricably connected to civil society, to our

constitutive attachments and to what social capital we possess, is a necessary requirement for the pursuit of a life worth valuing in a modern,

radically heterogeneous polity such as our own. Procedure alone is insufficient. Part V goes a step further. It then demonstrates that it is the

internalisation of norms such as dignity and equal concern and respect – by governors and governed alike – that enable the rule of law to

function both vertically and horizontally. That is, we must learn to treat one another as equals without the imposition of coercion. In short,

when

a and

reciprocal

internalised

civil society,

© 2018

Juta

Company

(Pty) Ltd. relationship exists between the rule of law and

Downloaded

: Mon Apr 18 2022 11:37:29 GMT+0200 (South Africa Standard Time)

2015 Acta Juridica 377

constitutive attachments and to what social capital we possess, is a necessary requirement for the pursuit of a life worth valuing in a modern,

radically heterogeneous polity such as our own. Procedure alone is insufficient. Part V goes a step further. It then demonstrates that it is the

internalisation of norms such as dignity and equal concern and respect – by governors and governed alike – that enable the rule of law to

function both vertically and horizontally. That is, we must learn to treat one another as equals without the imposition of coercion. In short,

when a reciprocal internalised relationship exists between the rule of law and civil society,

2015 Acta Juridica 377

the need for procedural fairness diminishes. Only once we have internalised the rules that govern one another, are we able to cooperate,

economically, socially and politically, in a manner that enables all denizens of a society to pursue lives worth valuing. Part V shows that the

convergence of views across a range of scholarly domains (and public fora) over the past several years provides cautious optimism about

building a rule of law culture, once we recognise the inextricable link that must exist between a rule of law culture and a civil society. Trust,

mutual respect, dignity, affinity, loyalty and mutual care and concern are slowly coming to be understood as central and essential features of

both. Put it this way: law enforcement officials are us, and we are them. When we realise that, and act accordingly, we create a virtuous circle

that enhances the rule of law and the flourishing of all South Africa's citizens.

II The rule of law and four South African master narratives

My adherence to the law at the red robot cannot easily be squared with the four current master narratives regarding the rule of law in South

Africa.

We are all well acquainted with the first master narrative: the Constitutional Court's foundational (and steadfast) commitment to the rule of

law. Although the capaciousness of this term of art is captured in Chief Justice Langa's ruminations above, its humdrum characterisation in Bato

Star continues to reflect the legal community's general understanding: 'Under our new constitutional order the control of public power is always

a constitutional matter.' 2 As Frank Michelman and others have noted, given the structure of our Constitution, that humdrum understanding of

the rule of law applies with equal force to both public relations and to private relations. Formally, no law and no conduct (public or private) fall

beyond the reach of the basic law. That tentacular reach is now (structurally) beyond dispute: the Constitutional Court, elevated to the

position of South Africa's highest court, possesses specific jurisdiction over a relatively small cohort of matters and effective general jurisdiction

over all disputes. 3 (As we shall see, and Michelman would surely agree, when we

2015 Acta Juridica 378

talk about the rule of law, we are concerned with far more than rationality review and jurisdiction.)

The second master narrative is the stuff of daily headlines. No less an SACP stalwart and Tripartite Alliance member than then Deputy

Minister of Public Works Jeremy Cronin railed against 'rogue' civil servants acting in 'cahoots' with 'dodgy service providers' that had swindled the

government out of billions of rand. 4 However, this master narrative extends beyond the fourth estate's regular reports of government

malfeasance. The Public Protector, the Auditor General and the Special Investigations Unit have all produced reports on widespread corruption. 5

No one banging the drum of this master narrative thinks our state (or our society) meets the threshold standards of a rule of law culture:

At a bare minimum, the point of the rule of law – and its great contribution to social and political life – is relatively simple: all actors should be

constrained by, and people should be able to rely on, the law when they act. Ideally, that requires that there be no privileged groups or

institutions exempt from the scope of the law; that in general the law be of a particular character, such that 'people will be able to be guided by it';

that institutions apply the law according to plausible legally grounded interpretations of its public terms; and that rule of law expectations and

values pervade social expectations, to a considerable extent. . . . There is more to it than this, but there is at least this much: you have a good

measure of the rule of law when the law in general does not take you by surprise or keep you guessing, when it is accessible to you as is the thought

that you might use it, when legal institutions are relatively independent of other significant social actors but not of legal doctrine, and when the

powerful forces in society, including the government, are required to act, and come in significant measure to think, within the law; when the limits

of what we imagine our options to be are set in significant part by the law and where these

2015 Acta Juridica 379

limits are widely taken seriously – when the law has integrity and it matters what the law allows and what it forbids. 6

From top­slicing on major deals, to more mundane skewing of public tender processes, to the more frightening feature of daily life in which large

portions of the population must negotiate interactions with law enforcement officials with sexual favours, daily life in South Africa is rife with

surprises.

The third master narrative is the 'WE' discourse to which we have been subject since the advent of constitutional democracy in 1994. Jeremy

Cronin's recent work has taken dead aim at this fictional 'we' and produced the corpse. 8 For example, in 1999, Nelson Mandela wrote:

For a country that not many years ago was the polecat of the world, South Africa has truly undergone a revolution in its relations with the

international community. The doors of the world have opened to SA, precisely because of our success in achieving things that humanity as a whole

holds dear. 9

The grammar of Mandela's language leads, and is meant to lead, its readers to accept two propositions: (1) we were all polecats under

apartheid; and (2) because we have implemented universally adhered to values, most especially the rule of law, we now live in a relatively

normal world. If one views Mandela's words as 'exceptional', then one might be inclined to read them as the words of the most creative

respondent to the depredations of apartheid. That is, he needed to co­opt every South African, irrespective of hue or class, in order to ensure

that they would – at the very moment of transition/revolution – understand South Africa as one nation faced with a legion of problems for which

we all are now responsible.

Others have not earned Mandela's pass. The language of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) speaks to a more pernicious form of

amnesia, and an equally dangerous fantasy. The TRC, in attempting to build a rule of law regime that constitutes 'a bridge from the past to the

future', (or a bridge of authority to a bridge of justification), writes:

2015 Acta Juridica 380

Ordinary South Africans do not see themselves as represented by those the Commission defines as perpetrators, failing to recognise the 'little

perpetrator' in each one of us. . . . It is only by recognizing the potential for evil in each one of us that we can take full responsibility for ensuring

that such evil will never be repeated. 1 0

Are 'we' to conclude that we were all 'perpetrators'? Issues of 'relative' moral equivalence don't even begin to feature in this skewed

asymmetrical version of history, or the rule of law culture to which the Constitution – in its opening stanza – commits us.

The TRC's Final Report ought to be understood as nothing more than the very beginning of a reckoning with our shared past, in which the

actual victims of apartheid would be seen as victims (and, where possible, clearly distinguished from perpetrators and collaborators). An open

and ongoing conversation between former adversaries might ultimately result in a legal regime where all are treated with equal concern and

respect. South Africa is nowhere close to reaching its first staging post: a robust rule of law culture (along with, political accountability and an

effective bureaucracy).

We seem stuck. In an address to Parliament in 2013, Trevor Manuel stated that: '[t]he first task of the National Development Plan (NDP) is to

unite all South Africans around a common programme, of all our people around the common goal of fighting poverty and inequality.' 1 1 But do we

have a common goal of fighting poverty and inequality? To be sure, no one would declare openly that they were in favour of living in a country

with the world's highest Gini­coefficient and the worst levels of sexual and interpersonal violence in a country not wracked by a civil war. 1 2

However, the economic structures that served apartheid and colonial rule remain virtually untouched. We cannot truly expect that these

structures alone (or as they stand) would somehow reorient themselves – via the rule of law – to serving 'all of us'. Despite the cogency of

Manuel's address, the text of the NDP itself is wholly out of touch with just how far away we remain from the very first staging post. It opens

with a bizarre invocation in the first person plural:

2015 ACTA 381

Now in 2030, we live in a country which we have remade . . . We feel understood . . . We feel needed . . . We feel trusted . . . We feel

accommodative . . . We feel accommodated . . . We are traders. . . . We are inventors. . . . We are workers. We create companies. . . . We set up

13

© 2018 Juta

and Company

(Pty)

Ltd.

Downloaded

: Mon Apr 18 2022 11:37:29 GMT+0200 (South Africa Standard Time)

stalls.

. . . We are

studious.

. . . We are gardeners. . . . We feel a call to serve.

The authors of the NDP are surely right to think that we are at least 17 years away from our first staging post. The first stanza becomes

with a bizarre invocation in the first person plural:

2015 ACTA 381

Now in 2030, we live in a country which we have remade . . . We feel understood . . . We feel needed . . . We feel trusted . . . We feel

accommodative . . . We feel accommodated . . . We are traders. . . . We are inventors. . . . We are workers. We create companies. . . . We set up

stalls. . . . We are studious. . . . We are gardeners. . . . We feel a call to serve. 1 3

The authors of the NDP are surely right to think that we are at least 17 years away from our first staging post. The first stanza becomes

substantially more suspect when it presumes that regular successful action will create the kind of social capital necessary to produce a virtuous

cycle of improvement upon improvement. It takes little notice of the fragmentation that besets us (and the disorder and disintegration in the

world around us), and how difficult such fragmentation is to overcome in radically heterogeneous societies. 1 4 On the truly odd stanza, what

can one say: that the South Africa of 2030 will look like an optimised version of the highly stratified society in which we currently reside? That

traders, venture capitalists, mine workers, multinationals, street vendors, college graduates and gardeners – as they exist in the present – will

all earn a living wage and be content with their lot seventeen years on? Cronin is right to skewer this last rule of law fairy tale. It's no more

than the rhetoric of the ruling party and business elites in our one party dominant democracy. Such a conception of 'we' is dysfunctional now.

Why would 'we' expect it to work in a score of years, or for the distribution of jobs to look roughly identical to our current economic

arrangements? We shouldn't. Nobody actually does.

Where Cronin's crisp critique runs off the rails is his buy­in to a different kind of political fantasy: agonistic democracy. 1 5 To be fair, it's also

the dominant discourse in the academy because we like to talk and believe, incorrectly, that talking is the source of the solution to most

problems. Egg­heads tend to over­valorise conversation – and, consequently, the ideals of democratic deliberation and direct political

participation.

2015 ACTA 381

Call them 'we­whimsies'. 1 6 These 'we­whimsies' frustrate our efforts to first put in place the scaffolding that constitutes the primary purpose of

our Constitution: a genuine, robust rule of law culture. 1 7 The fourth master narrative possesses the coolest, most incisive eye in so far as it is

keyed to local conditions. It views states such as South Africa through the prism of recent political science literature on the fate of post­

authoritarian constitutional democracies that came into being after the fall of the Berlin Wall. 1 8 For these comparative constitutional law

scholars, the pathologies of rent­seeking behaviour and clientelism flow, largely, from extended one­party dominance. This one party dominance

not only constrains any given constitutional court from vouchsafing the barest commitments to the rule of law, it places the very project of

democratic constitutionalism at risk. From Hungary to South Africa to Venezuela to Tunisia to Moldova, the song remains largely the same. Sam

Issacharoff has recently written incisively about the 'to be expected arc' of South Africa's constitutional democracy when refracted through the

lens of comparative constitutionalism:

After a period of relative quiescence as to democratic governance, the Constitutional Court appears to be entering a third period, one whose

progress is far from set, but meriting of notice. The defining feature of this latest phase is that the ANC is now the established and dominant

political force in the country and, thus far, faces no significant political opposition. As is often the case when electoral competition recedes, the

dominant party becomes the centre for all political and economic dealings with the government, and an incestuous breed of self­serving politics

starts to take hold. In this third period, the Court is confronting some of the efforts of the ANC government to place itself beyond customary forms

of legal and democratic accountability. The

2015 Acta Juridica 383

political transcendence of the ANC limits the ability of the political system to correct course or, at the very least, has frustrated many efforts to

date. . . . Gauged from afar, the question is now whether the Court will be, and perhaps whether it can be, a restraining influence on excessive

consolidation of political power. 1 9

Although he writes quite self­consciously in the patois of comparative constitutionalism, Theunis Roux's path diverges somewhat when it comes

to possibilities and prescriptions:

Is a . . . conversion to a more populist strategy, one focused on building the Constitutional Court's institutional legitimacy, now both desirable and

possible? . . . Fortunately for the Court, the prospects for pursuing this sort of strategy have improved. As much as the ANC's descent into

factionalism threatens the Court, it also provides an opportunity to distinguish itself from the governing party. 2 0

To be stuck is not to remain stuck. Roux's conclusions are extremely modest: '[L]aw is . . . capable of shaping and constituting judicial

preferences, and in this way acting both as a significant constraint on judicial decision­making and also as a source of legitimacy.' 2 1 However,

that truth is contingent on the particularities of a given constitutional order and the unique circumstances of the polity in which it is situated,

at any given moment in time. Roux's question above – 'Is a . . . conversion to a more populist strategy . . . both desirable and possible?' – must

be taken seriously. His question anticipates concerns raised here. How much can we reasonably expect an apex constitutional court, on its own,

to contribute to the creation of a reciprocal relationship between a rule of law culture and a thicker civil society? One possible interpretation of

his question is that our expectations ought to be quite modest. 2 2 My purpose in setting out these four master narratives regarding the rule of

law in South Africa has not been to tear them down. Quite the opposite. A substantial degree of truth obtains in all four. The overall effect

should be cumulative. In acknowledging my substantial agreement, along with my occasional doubts, I hope to have set the stage for

introducing two

2015 Acta Juridica 384

additional narratives into our discussion of the rule of law in South Africa. In a moment, we'll see how Tom Tyler has, over the last 25 years,

connected the strength or the weakness of a rule of culture with a citizenry's views on the 'procedural fairness' of a state's law enforcement

institutions (from the police to the courts to administrative agencies.) Before I introduce Tyler's ideas, I wish to present some of my own views

on the reciprocal relationship between a robust rule of law culture and the internalisation of norms that govern the interactions between

members of a genuinely civil, civil society. This introduction regarding that reciprocal relationship is then used to test what I believe to be some

of the limitations of Tyler's profoundly important body of work.

III On the reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society

This article offers a rather modest (and incomplete) remedy to the difficulties of moving from an authoritarian apartheid regime to a polity

grounded in a substantive notion of the rule of law. It starts with six basic axioms.

First, interactions that build mutual trust, concern, care and loyalty in individual relationships and within more formal networks and

institutions can, cumulatively, create a set of subpublics and a state identified with a deep commitment to the rule of law.

Second, a stable and procedurally fair rule of law culture and a 'civil' civil society – neither of which yet obtain in South Africa – each benefit

from this bottom­up account. If constantly tweaked, then we might eventually see state structures that enjoy greater legitimacy and a

strengthening of the various associations, networks and subpublics that constitute civil society and that provide us with (a) the better part of

life's meaning and (b) our own everyday run­of­the­mill sense of justice.

Third, it is no accident that in post­authoritarian constitutional democracies we often witness a cycling downwards both in respect for

ostensibly now legitimate makers and enforcers of law, and in the vibrancy of a civil society that had, under conditions of repression, found the

strength to reach across political divisions to bring about the demise of an illegitimate regime. Why? The historically dispossessed (or their

putative representatives) find the state, through governance and control of the public till, to be the most the immediate form of redistribution

(to a relatively limited clan). The result is rent­seeking behaviour and extractive arrangements which places the governors above the rule of law

and the governed below as supplicants. Civil society, on the other hand, finds itself fractured, post­liberation, because its driving force –

liberation – no longer obtains. The cohesion between groups joined in revolt against an authoritarian state dissipates. Various networks,

associations and communities within

2015 Acta Juridica 385

civil society that had collaborated so well together often find themselves thrown back into those narrow subpublics: to their surprise, they are

not yet members of the egalitarian pluralist social order promised by the new constitutional dispensation. What then is to be done about this

rather depressing, if common, post­authoritarian, new constitutional democracy states of affairs? Some answers can be culled from recent

© 2018

Juta and

Company

Ltd.

Downloaded

: Monand

Apr (b)

18 2022

11:37:29

GMT+0200

(South

Standard

literature

around

(a) (Pty)

procedural

fairness mechanisms as rule­of­law development

processes

the still

nascent

body of

workAfrica

on how

trust,Time)

loyalty and mutual care and concern generate the large stores of social capital that animate pulsating civil societies.

2015 Acta Juridica 385

civil society that had collaborated so well together often find themselves thrown back into those narrow subpublics: to their surprise, they are

not yet members of the egalitarian pluralist social order promised by the new constitutional dispensation. What then is to be done about this

rather depressing, if common, post­authoritarian, new constitutional democracy states of affairs? Some answers can be culled from recent

literature around (a) procedural fairness mechanisms as rule­of­law development processes and (b) the still nascent body of work on how trust,

loyalty and mutual care and concern generate the large stores of social capital that animate pulsating civil societies.

Out of these two bodies of literature comes this article's fourth axiom. From a bottom up perspective, the new 'obeying the law' theories and

more mature notions of 'social capital' suggest that two or more 'positive' interactions that individuals have with law enforcement, or

bureaucratic officials, or the gatekeepers of communities and subpublics, will reinforce the commitment to the rule of law and respect for other

constituencies in a civil society. But an order of priority exists that cannot be lightly dismissed. It is true that the rule of law is essential as a

background condition for the 'civil' civil society that we, who live in radically heterogeneous cosmopolitan countries, so rightly desire.

It's false to say that the rule of law comes first (save perhaps in its coarsest Hobbesian form.) The relationship, as Krygier makes

transparently clear, is one of reciprocal effect:

At a bare minimum, the point of the rule of law – and its great contribution to social and political life – is relatively simple: all actors should be

constrained by, and people should be able to rely on, the law when they act. Ideally, that requires that there be no privileged groups or

institutions exempt from the scope of the law; that in general the law be of a particular character, such that 'people will be able to be guided by it';

. . . and that rule of law expectations and values pervade social expectations, to a considerable extent. . . . There is more to it than this, but there is

at least this much: you have a good measure of the rule of law when the law in general does not take you by surprise or keep you guessing. . . .

In doing so, the rule of law makes possible something else which is impossible without it: civil society itself, as a durable, routine state of affairs. Legal

institutions and legal rights are central to an established civil society: for it to be able to moderate – stably, routinely, and effectively – the powers

of government and the powers of each other and to mediate between government and citizens and between citizens themselves. The rule of law

is not only important for securing the infrastructural strength of states. It is also crucial for social strength. 2 3

In short, a robust rule of law relies upon and provides support for a healthy civil society. A robust civil society invests the rule of law with a

democratic

2015 Acta Juridica 386

solidarity which no more than a handful of polities have made real. Now why should that be so? The obvious answer is that democracy in its

most basic form is really no more than half a century old (and not even that in the 93 of 200 odd nations on the planet that claim that mantle).

Even if Krygier and I remain reluctant to offer a blueprint, a sketch is at hand:

Where power is routinely and reliably constrained by law, and where law counts as an integral frame and constituent of what is doable and what

is thinkable in the society, then, important conditions of civility – in particular, a lessening of fear of arbitrary power – have been attained. . . . [A]t

the horizontal level of relations among citizens, the rule of law enables and facilitates confident interaction and co­ordination among non­

intimates, which are central conditions of a modern civil society in good shape . . . It establishes fixed and knowable points in the landscape, on

the basis of which the strangers who routinely interact in modern societies can do so with some security, autonomy, and ability to choose. And so

it provides a foundation and scaffolding for the building of 'civil' relations between state and citizens and among citizens themselves. They can

begin to rely upon, rather than merely fear, the state and law. Apart from causal relationships, there is, I would suggest, a real affinity between

rule of law and civil society. Causal links are sometimes hard to trace, but a polity in which the rule of law has a deep hold is one in which restraint

is, to that extent, a cultural norm. So too respect. . . . [R]estraint and respect are norms of civility as well. So civil society and the rule of law go

well together . . . with pylons firmly planted on both sides of the divide and input moving in both directions. Or so it is when the rule of law is a living

presence in society, part of the cultural understandings of everyday life, part of the frame which bounds what is doable and even thinkable. I am

conscious that this is an idealization of virtually any legal order, but it is one approached more closely by some than others. 2 4

There then is our relationship of reciprocal effect. No one, to my knowledge, has put it better. But Krygier has seen too much, and knows better,

than to offer pat theories regarding how we might go about erecting the scaffolding for the rule of law or more detailed plans regarding the

architecture of a truly civil society. Indeed, he completes his analysis with a warning:

[T]here are two mistakes commonly made about thresholds [regarding the rule of law and civil society], or what Selznick calls 'minimum conditions

of survival'. . . . One is to ignore them. . . . But the other mistake is to overgeneralize the bearing of these conditions. Once they are satisfied, they

typically don't tell us how the phenomenon, whose basic conditions of survival have been secured, might thrive, or even what it is for it to thrive.

25

2015 Acta Juridica 387

This explication of the reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society is critical for this paper for two reasons. As we shall see,

behavioural and legal sociologists such as Tyler have tended to approach the rule of law by asking a simple question – 'Why do people obey the

law?' The answer, oversimplified for now, is that short of pure coercion, individuals and groups obey the law when they believe that the law is

being enforced in a 'procedurally fair' fashion. That's interesting, and borne out by extensive surveys in some jurisdictions.

Krygier's analysis, as well as my own, suggest that something is missing from Tyler's important set of insights. Krygier, above, and I

elsewhere, 2 6 describe what might be called a substantive view of the rule of law, as opposed to its more desiccated, mere rationality­based

cousin. Krygier and I connect the rule of law, as we roll it out, to a thick set of ethical relationships between individuals, groups and subpublics

(in civil society), and bureaucrats, law enforcement officials and politicians (in the rest of the state apparatus.) Krygier and I do not demand

more for us than we can imagine. Nor does he demand more of the rule of law and civil society than can already be seen here and there, in

pockets, around the world. If we stop short of sketching a blueprint for the creation of a political community committed to a substantive vision

of the rule of law married to a vibrant civil society, then it is entirely understandable. No such blueprint exists – nor can it. Like pornography, 2 7

only better, we know it when we live it.

Sixth. The three catch and release interactions that I had over a two­week period – and the reflections to which they led – strongly suggest

that the internalisation of norms is not a process that occurs during our earliest, formative years and simply ends there. Unfortunately many

legal theorists writing in this space suggest that the normative world that we inhabit is predominantly static, rather than fluid. This

presupposition

2015 Acta Juridica 388

is simply not so. Throughout our lives, we invariably move back and forth between psychological positions – and moral vantage points – as the

world continually disrupts our existence in innumerable ways. 2 8

The ongoing internalisation of the norms derived from one's political community can be seen to be both fluid and palpable in my three catch

and release experiences. In all three instances, the police officers and I hoped to be treated with a certain degree of dignity, as well as mutual

care and respect. When this reciprocity – a view of the other as a genuine end­in­himself – occurred, the ambivalence we shared about our

respective place in the world dissipated. More importantly, our insecurity about the normative shape of the environment that we each inhabited

shifted. My subsequent stop at a red robot in a sketchy part of town (a shift in my behaviour) suggests that I had internalised norms about

respect for both the law and others. After all, robots are not just means of coordination (a traffic circle can accomplish the same end). They

reflect a communal desire to safeguard the well­being of others.

Similarly, as part of the internalisation of norms, I experienced a degree of 'pleasure' in the kind, professional manner in which the police

officers treated me. 2 9 In Kleinian terms, I overcame my anxiety about the degree of security that I required, found my concerns regarding law

enforcement in South Africa to diminish, and experienced satisfaction from the possibility of similar treatment in the future. I have little doubt

that the officers in question felt similarly. They saw themselves as equals in conversation after a transaction often experienced as fraught by

both parties. Only in a relationship between respectful equals – and not fawning subordinates, or manipulators of state power – would both

parties walk away feeling as if they had further internalised the norms of dignity and equality upon which our political community is predicated.

In my last encounter with the police, the internalisation of norms of mutual respect was quite palpable and deepened over the course of the

exchange. From the beginning we shared a basic commitment to the rule of law. My licence plate was affixed by duct tape after being knocked

loose by a taxi. I deserved to be pulled over. I possessed no appropriate form of identification. The phone call to my partner was, rightly,

deemed insufficient. All parties appeared willing to accept the appropriate outcome: a ticket for failure to carry proper identification. However,

when I

© 2018 Juta and Company (Pty) Ltd.

Downloaded : Mon Apr 18 2022 11:37:29 GMT+0200 (South Africa Standard Time)

2015 Acta Juridica 389

exchange. From the beginning we shared a basic commitment to the rule of law. My licence plate was affixed by duct tape after being knocked

loose by a taxi. I deserved to be pulled over. I possessed no appropriate form of identification. The phone call to my partner was, rightly,

deemed insufficient. All parties appeared willing to accept the appropriate outcome: a ticket for failure to carry proper identification. However,

when I

2015 Acta Juridica 389

produced my monograph confirming my identification – my name next to my photograph – the officer read the back cover in its entirety and

acknowledged that I was in fact who I claimed to be. No negotiations of an instrumental nature took place – no hints, no whiffs, not a scintilla

of line­crossing often experienced by others. Instead, we each sensed a mutual acknowledgement for who we are as individuals and the

respective roles that we play in our community. The fact that he takes care of me (occasionally) and others (regularly) and that I take care of

educating members of our community deepened our respect and care for one another. Again: The deepening of such mutual care and concern

reflects (a) the internalisation of the legal norms of the community of which we are both apart and (b) the modest beginnings of building a

robust rule of law and the ushering in of a truly 'civil society'. As Krygier and Klein both note, the two are inextricably linked. The police officers

and I share the same society. The more we recognise (and fully internalise) our shared constitutive attachments the closer we come to

reaching our first staging post.

Does anyone reading this article really deny that the primary source of our ethical orientation toward the world flows from our early family

environs, the social endowments provided by the communities into which we are born, and the political environment that we inhabit (and that

largely dictate our life outcomes)? Only diehard members of the chattering classes might think so. But as the poor, the devoutly religious, the

clannish, the decidedly domestic and the rich will readily concede, their lives are cabined and their views determined by their immediate

networks, long­standing belief sets whose content and contours have been shaped by others, and the opportunities that affluence affords and

destitution denies. So? Despite how radically determined our lives may be, we simultaneously possess the critical resources for change. 3 0

Moreover, such change and internalisation do not occur through deliberation but, as Wittgenstein writes, through 'regular, successful action'. 3 1

Do we need to know our Freud and Klein, our Putnam and Marx, our Tyler and Krygier to understand why we blow through red lights (posing a

danger to ourselves and others), pay bribes to police officers (undermining the very system of law that we hope will provide us with a degree of

security) or shoot dead our neighbours with a bullet through the head for no more than a flat screen television? No. We know that others have

not had their basic needs met. We know insufficient state or social structures exist to enforce the law. We know that we often care little for

others because they have failed to show us the minimum level of concern and

2015 Acta Juridica 390

respect. Under such circumstances, we fail to internalise the norms associated with the rule of law and the associations and communities that

exist in a 'civil' civil society. Without rough equality, a nascent sense of procedural justice associated with the rule of law, and the trust, loyalty,

friendship and shared ways of being in the world associated with the communities that form civil society, it's simply impossible to expect

individuals to place a value on the lives of others. 3 2

IV Tyler on why people obey the law

(1) Early Tyler

For over two decades, Tom Tyler has continually posed a question whose answer seems so obvious at first glance, but clearly isn't. Why do

people obey the law?

Put police on the streets, keep the robots in order, and people will generally comply with the law because they prefer compliance to jail or to

hefty fines. There's certainly something to the notion that most people obey the law because they don't want to spend a night in lock­up or

years in a state penitentiary as a fellow inmate's consort. A large number of contemporary authors still, and with some merit, believe that 'fear',

'terror' and 'state violence' drive compliance and give the law its authority. Peter d'Errico contends that the very framework of our system of

laws is designed to perpetuate its own power: 'The concept of civil rights . . . has meaning only in the context of an over­arching system of

legal power against which the civil rights are supposed to protect.' 3 3 Writing in a similar vein, Peter Kropotkin rather sardonically observes:

'Whatever this law might be,' since 'The Terror' of the guillotine­happy French Revolution 'it [has] promised to affect lord and peasant alike; it

proclaimed the equality of rich and poor before the judge.' 3 4

As should be clear from the four master narratives delineated at the outset, and my own contribution above, the rule of law is far from a

fraud. The rule of law, properly understood, is both a necessary requirement and a constitutive condition for the pursuit of a life worth valuing in

a modern, radically heterogeneous society. I have, at the same time, noted that the four master narratives, and my own gloss on the subject

are incomplete. If so, is there something else at work?

2015 Acta Juridica 391

That 'something else' could be one way of understanding one of Tyler's original findings that 82 per cent of his rather large sample believe the

following statement to be true: 'People should obey the law even if it goes against what they think is right.' 3 5 However, as Tyler notes early on,

coercion and fear only get the state so far in a reasonably free (but not perfect) society. Fear and force are resource intensive and require the

state to be present in every nook and cranny. Most 'functional' contemporary states (even with ever accelerating electronic surveillance, and

diminishing privacy) do not function in this manner. The United States, with all its Wiki­leak associated problems and police­initiated homicides,

still does not possess law enforcement machinery that operates like the military­mercantilist junta that runs China.

Given the absence of state machinery to punish every breach of the law or to prevent its very occurrence, what then explains the '82 per

cent'? Tyler begins his explanation (circa 1990) as follows:

The Chicago study's examination of legitimacy and compliance suggests several reasons why people obey the law. One is their instrumental

concern with being caught and punished: people typically think it quite likely that this will happen if they commit serious crimes. . . . Obedience to

the law is also strongly linked to people's personal morality. The data suggest a general feeling among respondents that law breaking is morally

wrong. A similarly strong feeling emerges in the case of the perceived obligation to obey the law. Most of the respondents interviewed felt obliged

to obey the law and the directives of legal authorities. In contrast to the strong normative commitment found in studying personal morality and

perceived obligation to obey the law, support for the police and courts was not particularly high, and neither were evaluations of their

performance. This does not mean, however, that dissatisfaction with the police or the courts is widespread. 3 6

Given that non­instrumental reasons or deeply substantive moral explanations do not appear to explain the high levels of obedience to and

compliance with the law, Tyler suspects that 'something else' is going on. Moreover, this 'something else' must be able to account for subtle

distinctions that the participants in this study – conducted in largely urban Chicago – drew between systemic unfairness and unfairness as

experienced by the subject. Tyler writes:

A similar distinction between general judgments and feelings about the self can be found in responses to questions about discrimination. When

respondents were asked whether the police treated citizens equally or favored some citizens over others, 74 percent said there was favoritism;

72 percent made the same statement about the courts. When asked whether people like themselves were

2015 Acta Juridica 392

discriminated against, however, most respondents said no (75 percent for the police, 77 percent for the courts). People see widespread

unfairness, yet do not see themselves as being discriminated against. 3 7

These numbers are enlightening.

In a city such as Chicago, the number of African­Americans in a representative study will invariably be quite high. Moreover, everyone in the

United States knows that a staggering one out of three African­American males passes through the criminal justice system. One out of three.

Yet the vast majority of individuals in this study neither felt personally discriminated against nor did they believe that the existence of some

systemic discrimination is grounds for disobedience. Tyler now has a bead on our $64,000 question. Why, when the police are not everywhere,

and the system is seen to favour whites over blacks, rich over poor, do people still continue to obey the law? Why, for example, did the author

of this article sit at a red robot in a sketchy part of town where no law enforcement officials or surveillance cameras were likely to be found?

© 2018Tyler's

Juta and

Company

Ltd.

: Mon

18individuals

2022 11:37:29

GMT+0200

(South Africa Standard

answer,

in (Pty)

short,

is the procedural fairness (or procedural justice)Downloaded

as experienced

byApr

the

in the

study themselves.

Tyler Time)

describes procedural fairness (or procedural justice) as follows:

Yet the vast majority of individuals in this study neither felt personally discriminated against nor did they believe that the existence of some

systemic discrimination is grounds for disobedience. Tyler now has a bead on our $64,000 question. Why, when the police are not everywhere,

and the system is seen to favour whites over blacks, rich over poor, do people still continue to obey the law? Why, for example, did the author

of this article sit at a red robot in a sketchy part of town where no law enforcement officials or surveillance cameras were likely to be found?

Tyler's answer, in short, is the procedural fairness (or procedural justice) as experienced by the individuals in the study themselves. Tyler

describes procedural fairness (or procedural justice) as follows:

Theories of procedural justice or [procedural fairness] suggest that people focus on court procedures, not on the outcomes of their experiences. If

the judge treats them fairly by listening to their arguments and considering them, by being neutral, and by stating good reasons for his or her

decision, people will react positively to their experience, whether or not they receive a favorable outcome. 3 8

This explanation possesses more than a patina of plausibility. Individuals who arbitrate cases, and who mainly serve to provide recommendations

as opposed to decisions, will recognise how 'listening' to others often changes the entire temperature of an informal proceeding. When people

are gently asked their account of what happened and why, and are treated with dignity, they tend tell their story as best as they possibly can

and express appreciation for being given the opportunity to be heard.

2015 Acta Juridica 393

These two notions of 'fairness as listening' share much in common – at least on the surface. Deep listening – whether it occurs in the

classroom, in the courtroom, on a psychoanalyst's couch or in a police station – can have a profound effect on how the person responds to

judgements by law enforcement officials or observations offered in counselling or in the classroom.

(2) What Tyler's (early) account misses: Constitutive attachments, social capital and the internalisation of norms

The profound effect described above emanates from the seriousness – the dignity, the care, the respect, the concern, the tolerance, the trust,

the loyalty and the recognition of the other individual as an end in herself – with which the police officer or the analyst or the professor or any

deep listening interlocutor acknowledges the subject. In the course of an exchange, a relationship is formed. If properly structured, that

relationship deepens over time. The ongoing reciprocal effect of the relationship between the analyst and analysand, the teacher and the

student, or the more mundane and perhaps fundamentally more important day to day listening relationships between colleagues, friends, or

neighbours, generates ever increasing amounts of social capital. This social capital – made up as it of loyalty, concern, trust, friendship, dignity

and mutual respect – enables us to sustain the communities, associations, institutions, networks and relationships where virtually all meaningful

action takes place. How constitutive attachments and social capital relate to the rule of law and procedural fairness are taken up in the next

two subsections.

(a) Constitutive attachments

It is trite to note that outside society, individual flourishing is a meaningless notion. Only within the various practices, forms of life, or language

games that social groups provide do we become anything that remotely approximates what we understand to be human.

Here is a somewhat more expansive account. We often speak of the social practices, endowments and associations that make up our lives as

if we were largely free to choose them or make them up as we go along. It just ain't so. Michael Walzer writes that there is a 'radical givenness'

to our social world and the practices that make it up. 3 9 What he means, in short, is that virtually all of the practices that constitute the

setting for individual lives are involuntary. We don't choose our family. We generally don't choose our race or religion or ethnicity or nationality or

class or citizenship. Moreover, even when we appear to have the space to exercise

2015 Acta Juridica 394

choice, we rarely create the practices available to us. The vast majority of our practices and forms of life are already there, culturally

determined entities that pre­date our existence or, at the very least, our recognition of the need for them. Finally, even when we overcome

inertia and do create some new practice (and let me not be understood to underestimate the value of such overcoming and creativity), the

very structure and style of the practice is almost invariably based upon an existing rubric. Corporations, marriages (irrespective of sexual

orientation), co­edited and co­authored publications are modelled upon existing associational forms. Even in times of radical transformation,

mimicry of existing social practices is the norm.

Perhaps Walzer's most interesting challenge flows from his invitation to think of what it might mean for individuals to lack involuntary

associational ties, to be 'unbound, utterly free?' 4 0 One image might be that of wild horses. But this very image is the antithesis of what makes

us human. We are human, and not feral, because of the involuntary practices into which we are born and which have been sustained and

developed over time. Even schools designed to enable us to make the most of our 'freedom' do not let us do whatever we so wish. We have to

learn to be free. It is more accurate to say that we must learn how to flourish. Even assuming that we could learn all that which might make us

fully human, we would never cross over into the domain of the undetermined and unconditioned. Flourishing would remain predicated upon

practices that were and continue to be involuntary in important respects. 4 1

This account of the involuntariness of social life is not meant to undermine the importance of the rule of law and procedural fairness for

individual and group flourishing in any truly complex, radically heterogeneous, democratic society. How the rule of law and procedural fairness

plays out in our law enforcement system must be constantly negotiated and renegotiated. Moreover, it is the strength of a rule of law culture

that enables us to continue enjoying the benefits of the communities, associations and subpublics of which we are members.

There can be no end when it comes to the effort necessary to sustain the relationships that bind us in associational life and to maintain the

rule of law that creates a system of governance that makes those relationships possible. Moreover, we've seen that the relationships within rule

of law institutions and practices take a similar form to those relationships found

2015 Acta Juridica 395

in other forms of life: they require trust, equal concern, care, dignity and loyalty that flow in both directions.

The emphasis on involuntariness in social life is, therefore, only meant to partially bracket Tyler's early account of the 'why people obey the

law' and what gives a rule of law culture its legitimacy. A reasonably equal and democratic society must mediate the givenness of our social life,

and the aspirations all of us have to gravitate towards those social forms of life which still fit and away from those which do not. It is often the

case, however, that not choosing to leave an association, but to stay, is what we truly cherish as freedom. The rule of law – and procedural

fairness – must protect such decisions. Indeed, as Walzer suggests, we ought to call such decisions to reaffirm our conditioned commitments

'freedom simply, without qualification.' 4 2 It is, for the most part, he concludes, 'the only "freedom" that free men and women can ever have.' 4 3

The reason, then, that we so highly value procedural fairness is that law enforcement officials and citizens committed to the rule of law protect

those aspects of freedom and civil society that we value most.

(b) The relationship of social capital to the rule of law and procedural fairness

Social capital is – and is a function of – our collective effort to build and to fortify the things that matter. It is our collective grit and elbow

grease, our relationships and their constantly re­affirmed vows. Social capital emphasises the extent to which our capacity to do anything is

contingent upon the creation and maintenance of forms of association which provide both the tools and the setting for meaningful action. Social

capital is often treated as ephemera. That makes sense. It is so hard to see. In fact, it is this elusive quality that makes social capital so

fragile. It is made up, after all, not of bricks and mortar, but of relationships and commitments, and the trust, respect and loyalty upon which

they are dependent. In Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam provides a helpful distinction: 'Whereas physical capital refers to physical objects and

human capital to the properties of individuals, social capital refers to social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise

from them.' 4 4 Social capital can be understood to buttress my insistence on an inextricable link between a rule of law culture and a vibrant civil

society.

2015 Acta Juridica 396

Social capital is what keeps our intimate, economic, political, cultural, traditional, reformist and religious associations – as well as our legal

order – going. Without it, nothing works. Social capital recognises that we store the better part of our meaning in fundamentally involuntary

© 2018

Juta and Company

(Pty)that

Ltd. social capital, and nothing that matters can continue

Downloaded

: Mon

Apr 18

2022 11:37:29

GMT+0200

(South

Africa

Standard Time)

associations.

Squander

to exist.

Social

capital

takes seriously

the

threat

of various

kinds of compelled association. Trust, respect and loyalty have no meaning where the association is coerced. These several virtues can be

society.

2015 Acta Juridica 396

Social capital is what keeps our intimate, economic, political, cultural, traditional, reformist and religious associations – as well as our legal

order – going. Without it, nothing works. Social capital recognises that we store the better part of our meaning in fundamentally involuntary

associations. Squander that social capital, and nothing that matters can continue to exist. Social capital takes seriously the threat of various

kinds of compelled association. Trust, respect and loyalty have no meaning where the association is coerced. These several virtues can be

earned, but never commanded. No trust, respect or loyalty: no social capital. 4 5 No social capital: none but the most debased forms of (social)

life, and no room for building the kind of robust rule of law culture that our aspirant constitutional democracy envisages.

However, not all social capital formations possess the same structure: some take the form of bonding networks, others take the form of

bridging networks. Putnam puts the difference between these two distinct forms of social capital networks as follows:

Some forms of capital are, by choice or necessity, inward looking and tend to reinforce exclusive identities and homogeneous groups. Examples of

bonding social capital include ethnic fraternal organizations, church­based women's reading groups, and fashionable country clubs. Other

networks are outward looking and encompass people across diverse social cleavages. Examples of bridging social capital include the civil rights

movement, many youth service groups, and ecumenical religious organizations. . . . Bonding social capital provides a kind of sociological superglue

whereas bridging social capital provides a sociological WD­40. 4 6

2015 Acta Juridica 397

One way to distinguish the two networks would be, as Halpern notes, to 'contrast the strong bonds of reciprocity and care that are found inside

families and small communities (what we might call normative bonding networks) with the [at least initially] self­interested norms that tend to

predominate between relative strangers . . . and through which relative strangers can co­operate successfully (what we might call normative

bridging networks.)' 4 7 But that's just a start.

High bonding communities tend to feature well­established, historically entrenched belief sets, shared assets and rather rigid rules regarding

membership, voice and exit (as well as mechanisms for the use of those rules). Bridging networks are often extra­communal and bring together

rather diverse groups of individuals in the pursuit of singular, generally self­interested ends. Membership, voice and exit tend to be both more

flexible and more formal in bridging networks. On this account, rule of law institutions play an essential role in maintaining bonding networks,

mediating disputes between bonding networking and facilitating the growth of strictly formal relationships in bridging networks into something

deeper and more meaningful.

(c) The antecedence of the internalisation of norms

To understand the reciprocal relationship between rule of law and civil society, it's worth fleshing out that last sentence. First, the rule of law

plays a critical role in ensuring that citizens have relatively equal access to bridging networks – especially those networks that create access to

basic goods. Once the rule of law enables us to meet as relative equals in

2015 Acta Juridica 398

bridging networks, we can form new bonding networks that create an even more vibrant civil society.

We can now link Tyler's concern with procedural fairness to something deeper: 'civility'. What ties citizens to the law – and to respect the

judgment of the others – is parasitic on the respect that they accord one another, in both the public sphere and the private sphere. In a robust

rule of law culture and a vibrant civil society we place our trust in the hands of others because we expect them to treat us as ends, and

never solely as means. The expectation that we shall be seen as ends­in­ourselves – and never solely as means – explains why Krygier links the

development of a robust rule of law culture to the emergence of a vibrant civil society.

(3) Why Tyler's initial insistence on neutrality as the psychological basis for procedural fairness appears incomplete

The priority of dignity, of mutual concern and respect, of loyalty, of care, of friendship, of reciprocity in the civil sphere throws something of a

large question mark over Tyler's initial insistence that neutrality is the primary driving factor or psychological basis for procedural fairness.

Consider your average beat cop. She walks a neighbourhood and gets to know the people in the community. Such a relationship is reciprocal

in nature. The beat cop – all things being equal – wants the community that she guards to be safe and free of anxiety so that they can go

about their normal daily activities. The members want much the same from this custodian of their lives. Over time, the beat cop and the

members of the community come to understand that their interests are largely co­extensive. They assist one another in both preventing crime

and responding to problems before they become crimes or even mere nuisances.

My three experiences with three different sets of Johannesburg Metropolitan Police Officers suggest the same kind of reciprocal relationship. I

need them to keep the streets safe – and regular license and disk checks suggest that they are trying to do so. Our interactions reflected

mutual respect and dignity. I never contested the manner in which they discharged their responsibility: when I was able to establish that I was

in fact who I claimed to be, I was accorded the respect and the dignity that I expected as a member of the community whose rules they

enforce. The regular experience of mutual respect, friendliness, trust, dignity and even loyalty over a short span of time led me to reconceive

the legal environment about me as both fair and legitimate. I stopped at the red robot.

Let's not over­egg the pudding. South Africa experiences extraordinarily high levels of violence and the world's highest level of sexual

violence in a country not at war or riven by civil war. The police services have been unable to put a significant dent in those figures. Moreover,

as reports from

2015 Acta Juridica 399

oversight agencies such as the Public Protector and Auditor General have shown, our security services remain plagued by corruption.

48

All that being said, my response to proper police conduct seemed, upon reflection, to be consistent with their treatment of me as end­in­

myself entitled to equal concern and respect, dignity, friendliness and care – call it civility. From this vantage point, Krygier's explanation for the

relationship between the rule of law and civil society seems somewhat more compelling. Neutrality seems too weak to capture the reciprocal

nature of these interactions.

Moreover, even the participants in Tyler's survey would appear to diverge, somewhat, with his characterisation of the police and court

systems that serve them. On his own account, they don't trust the system to be even­handed or neutral. They believe that the system is in

fact going to favour some individuals and groups over others – be it in terms of class, race, gender, ethnicity or public power.

What Tyler's initial survey does reveal is that the 82 per cent of people who said one should obey the law have not themselves been the

object of discrimination, nor do they expect to be. It's not so much the system that they trust to be neutral, but the lived experience of having

been treated as an object of mutual concern, care and consideration.

I don't mean to deny that Tyler shows that the participants in the Chicago survey do not have some reasonable expectation (a) that 'all

citizens, and the governors and the governed alike are going to be subject to the same set of rules' and (b) that this expectation of procedural

fairness leads them to obey the laws and consider the legal order to be largely legitimate. What my analysis and Tyler's own subjects reflect is

that there is an antecedent psychological relationship between (a) members of the community who are only members of civil society and (b)

members of the community who are also members of the law enforcement mechanisms of the state. Let's call that shared psychological

relationship 'civility'. Once we describe this relationship in terms of civility (and not neutrality) it becomes possible to see the reciprocal effect

between building a rule of law culture and the creation of a vibrant civil society more clearly.

V General developments in Tyler's work and its application to South Africa

(1) Recent studies and some apparent changes in the psychological underpinnings of Tyler's analysis in England and Wales

In a 2012 study conducted in England and Wales called 'Why Do People Comply with the Law?', Tyler (along with four fellow authors) sought to

© 2018 Juta and Company (Pty) Ltd.

Juridica

400

Downloaded : Mon Apr 18 2022 11:37:29 GMT+02002015

(SouthActa

Africa

Standard

Time)

determine whether his findings and his conclusions in the United States had purchase in another country. Although the United States, England

V General developments in Tyler's work and its application to South Africa

(1) Recent studies and some apparent changes in the psychological underpinnings of Tyler's analysis in England and Wales

In a 2012 study conducted in England and Wales called 'Why Do People Comply with the Law?', Tyler (along with four fellow authors) sought to

2015 Acta Juridica 400

determine whether his findings and his conclusions in the United States had purchase in another country. Although the United States, England

and Wales have similar legal traditions, they employ different political institutions, and, more importantly, possess dramatically different historical

narratives as peoples and nations. 4 9 The study's conclusions are not that surprising – given my analysis of Tyler's work on its own terms.

However, as I note below, the real surprise does not flow from different responses to the same study protocols.

Unlike the US­based studies, the England/Wales study showed that procedural fairness was not the dominant consideration for the citizens'

compliance with the law. The England/Wales study revealed that (a) procedural fairness and (b) the moral/normative alignment of the

community and the behaviour of various law enforcement officials played an equally strong role with respect to an overall sense of the legal

system's legitimacy by the English and the Welsh.

That should come as little surprise given the manner in which society, polity and history more readily map on to one another in England and in

Wales. One member should reasonably expect another member of those same communities to behave in the same manner – ethically, legally, and

socially. 5 0 All members of the various communities that make up England and Wales share a similar sensibility. It means something to be 'English'

or 'Welsh' in a way it does not for someone to be 'American'.

Here then is the critical difference between Tyler's original US­based studies and the study conducted in England and Wales: the general

population expected that the police and other law enforcement officials would operate within the same ethical framework as those they

governed. Failure to do so would result in the refusal to comply with the law and its consequent diminishment in legitimacy. For the English and

the Welsh, the law is embedded in a complex matrix of social relations and expectations that provide ties understood to bind the governed and

the governors alike.

A careful reader might now be inclined to say that these findings probably suggest that Tyler hasn't genuinely appreciated (or foreseen) my

argument nor accounted for them in his data in two distinct jurisdictions. Had Tyler and others done so, the US and England and might not look

so different. No. Tyler did appreciate some of the significant differences in the two jurisdictions. However, had he and his acolytes read this

piece

2015 Acta Juridica 401

earlier, then they might have asked different questions that revealed underlying commonalities and ongoing differences.

(2) Recent studies and some apparent changes in the psychological underpinnings of Tyler's analysis in sub­Saharan

Africa

Given the relative fragility and apparent fragmentation of many sub­Saharan countries over the last two decades, one might expect that their

short histories would not ground or legitimate the legal system in the same manner as such established jurisdictions as the United States and

the United Kingdom. That would be right.

But it would not mean that prima facie grounds for legitimacy and for compliance with the law might not otherwise exist. Post­colonial and

post­authoritarian rule has given way to generally popular democratic sovereignty. Of course, self­rule is not a free pass, however much the

new political elite might want it to be. Trust must still be earned.

Those two poles, the legitimacy of self­rule and the legitimacy that flows from trust, became, by and large, the basis for Tyler and company's

first venture into Africa. What Margaret Levi, Audrey Sacks and Tom Tyler found in 2009 might come as some surprise. By and large, citizens in

Sub­Saharan Africa count their governments as trustworthy. Here are the numbers: 'The average respondent has a predicted probability of 74%

of accepting the tax department's authority, a probability of 82% of accepting the police's authority, and a probability of 78% of accepting the

court's authority.' 5 1 (South Africa happens to fall in the middle of the Afrobarometer numbers (used in the Levi­Sachs­Tyler study) for 2013.)

The acceptance turns on the broad notion of a 'trustworthy government'. Trustworthiness is, in turn, a function of several factors: (a)

administrative competence, (b) enforcement and monitoring of regulations and laws, (c) procedural fairness, and (d) honesty and tolerable

levels of corruption, cronyism and clientalism (to use Issacharoff's alliterative troika.)

The authors' shift to 'trustworthiness' rather than neutrality is consistent with my emphasis on the reciprocal relationship between building

the rule of law and the creation of a civil society. Read carefully what the authors had to say:

A trust evaluation depends on assessments of the intentions of the governors, the quality of government performance, and its administrative

competence. Government leaders who credibly commit to serve the welfare of the whole population improve their capacity to elicit confidence in

the government they manage. Governments that provide services and protections that bolster citizen welfare

2015 Acta Juridica 402

or are demonstrably developing the capacity to do so should be more likely to elicit the willing deference of citizens. 5 2

Exploitation under colonial or authoritarian rule is no longer a dominant driver of citizens' concerns in sub­Saharan Africa. What they want, quite

clearly, is a government that allows them to get on with their lives by providing those public goods that facilitate their own conceptions of lives

worth valuing. The better able the government demonstrates itself to be in delivering the basic framework of a well­ordered society – one that

allows people to pursue their desired ends – the more likely the government is to secure the trust of the people – and thus its legitimacy.

There, in short, is your reciprocal relationship between the rule of law and civil society. So long as individuals and groups perceive the state

as enabling them to flourish, they are more likely to view the government as doing more than discharging the requirements of a minimalist

conception of the rule of law. Instead, they will perceive the state as committed to a set of reciprocal responsibilities that bear substantially