Preeclampsia Case Study: Nursing Assessment & Interventions

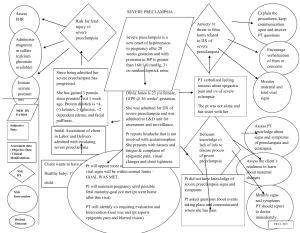

advertisement

A 38-year-old female is 36 weeks pregnant and arrives at labor and delivery for a headache that won’t go away with acetaminophen. The nurse gets the patient’s vitals. What should the RN be asking the client? - The nurse should be asking the patient if she has any blurred vision, if she has had any floaters, nausea, or vomiting. The nurse should also be asking if she has had any sudden weight gain or and swelling in the hands and face and or her feet. Also I would also ask the patient if she has had any abdominal pain. What other assessments should the nurse do at this point? - The nurse can assess the body as she is talking to see if she can see any visual edema. You also should ask the patient if she has this issue before. You can also get some past and present medical history. Possibly even family history. I think you could even hook her up to a fetal monitor to make sure the baby is ok. The nurse notes that the patient’s blood pressure is 156/98 mm hg and asks the patient “have you had any blurred vision, floaters or changes to that? Any sudden swelling, sudden weight gain? -The patient responds, “yes, I keep seeing floaters and have even thrown up from it. I do have some swelling and my upper abdomen has really been hurting. My head is really hurting. - The nurse goes to call the doctor. Nurse to Dr. “Hey Dr. Smith your patient, Maria Evans is here with some symptoms of preeclampsia. She has a BP of 156/98 mm hg, epigastric pain, bad headache, and some vision changes. What do you expect the doctor to order? - I would expect the doctor to order a urine to see if there is any protein in the urine. Blood work to test for full blood count, platelets, any kidney issues. Maybe also you can do a Non stress test or biophysical profile. You could also do a fetal ultrasound. The nurse calls for help and nurses enter the room. They call the patient’s name, get fetal heart tones, apply oxygen, protect the patient. A nurse calls the doctor again and explains the patient is having a seizure. What nursing actions have you already implemented? And why? - The nurse has lowered the head of the bed to keep the patient safe. There is also padding on the bed rails again for the patient’s safety and to try to prevent any injury. There is a nasal cannula and or mask to give the patient 02. Also suction equipment is ready to promote airway clearance. What is pathologically happening to the patient? - Pathologically the patient is becoming eclamptic. Eclampsia usually follows preeclampsia. Which is usually due to high blood pressure and protein in the urine. When your preeclampsia gets worse it affects your brain function which causes seizure which then leads to eclampsia. What do you want the Health Care Provider to order? - You would want the healthcare provider to order something to prevent the seizures (an Anticonvulsant) like magnesium sulfate. As well as something to treat the high blood pressure such as Lebetolol. Signs and Symptoms of Preeclampsia and Why It's Important to Monitor Pregnancy can be a challenging time. Unless you’re one of the lucky few, it brings swelling, aches and pains, nausea, and other unpleasant symptoms. While most soon-to-be mothers would agree that the changes in their bodies are worth it, some pregnancy symptoms can indicate problems like preeclampsia, which involves high blood pressure, swelling of the hands and feet, and protein in the urine. It’s dangerous because when it’s untreated, it can lead to HELLP syndrome and eclampsia, which are life-threatening. Preeclampsia affects between 5-8% of pregnancies and usually develops between 20 weeks gestation and six weeks after delivery. Signs of Preeclampsia Preeclampsia can be scary because its symptoms often aren’t noticed. In fact, if you have preeclampsia, the first time you may have any indicator something’s wrong will be at your regular prenatal appointments when your doctor screens your blood pressure and urine. Because preeclampsia can mimic regular pregnancy symptoms, regular prenatal visits with your doctor are critical. Signs (changes in measured blood pressure or physical findings) and symptoms of preeclampsia can include: High blood pressure (hypertension). High blood pressure is one of the first signs you’re developing preeclampsia. If your blood pressure is 140/90 or higher, it may be time to become concerned. Even if you’re not developing preeclampsia, high blood pressure can indicate another problem may be happening. If you have high blood pressure, your doctor may recommend medications and ask you to monitor your blood pressure at home between visits. Lower back pain related to impaired liver function. Changes in vision, usually in the form of flashing lights or inability to tolerate bright light. Sudden weight gain of more than 4 pounds in a week. Protein in the urine (proteinuria). Preeclampsia can change the way your kidneys function, which causes proteins to spill into your urine. Your doctor may test your urine at your prenatal visits. If you’re showing signs of preeclampsia, you may also be asked to collect your urine for 12 or 24 hours. This will give your doctor more accurate results for how much protein is in your urine and can help him or her diagnose preeclampsia. Shortness of breath. Increased reflexes, which your doctor may evaluate. Swelling (edema). While some swelling is normal during pregnancy, large amounts of swelling in your face, around your eyes, or in your hands can be a sign of preeclampsia. Nausea or vomiting. Some women experience nausea and vomiting throughout their pregnancy. However, for most women, morning sickness will go away after the first trimester. If nausea and vomiting come back after mid-pregnancy, it can be a sign you’re developing preeclampsia. Severe headaches that don’t go away with over-the-counter pain medication. Abdominal pain, especially in the upper right part of your abdomen or in your stomach. Who’s at risk? While it’s impossible to tell which expecting mothers will develop preeclampsia, you may be at risk if the following factors are present: A multiple pregnancy (twins or more) History of preeclampsia A mother or sister who had preeclampsia History of obesity High blood pressure before pregnancy History of lupus, diabetes, kidney disease, or rheumatoid arthritis Having in vitro fertilization Being younger than 20 or older than 35 Complications of preeclampsia Preeclampsia can affect both mother and baby. These complications might include: Preterm birth. The only way to cure preeclampsia is to deliver your baby, but sometimes delivery can be postponed to give your baby more time to mature. Your doctor will monitor your pregnancy and preeclampsia symptoms to determine the best time for your baby to be delivered in order to preserve your health and the health of your baby. Organ damage to your kidneys, liver, lungs, heart, or eyes. Fetal growth restriction. Because preeclampsia affects the amount of blood carried to your placenta, your baby may have a low birth weight. HELLP syndrome. HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome is a severe form of preeclampsia that can be life-threatening for you and your baby. HELLP syndrome damages several organ systems at once. Eclampsia. Uncontrolled preeclampsia can turn into eclampsia. It includes all of the same symptoms of preeclampsia, but you’ll also experience seizures. Eclampsia can be dangerous for both mother and baby. If you’re experiencing eclampsia, your doctor will deliver your baby no matter how far along you are. Cardiovascular disease in the future. Your risk of cardiovascular disease increases if you have preeclampsia more than once or if you’ve had a preterm delivery. Placental abruption happens when the placenta separates from the wall of your uterus before your baby is delivered. It causes bleeding and can be life-threatening for you and your baby. Treatment options for preeclampsia Your doctor will treat your preeclampsia based on how severe your symptoms are, how far along you are, and how well your baby is doing. When monitoring your preeclampsia, your doctor may recommend regular blood pressure and urine testing, blood tests, ultrasounds, and non-stress tests. He may also recommend: Treatment with betamethasone, a steroid that will help mature your baby prior to delivery if you’re still early (< 37 weeks) in your pregnancy Delivery of your baby if your symptoms are severe or if you’re at 37 weeks or more. Modified bed rest at home or in the hospital if you’re not yet at 37 weeks, and if your and your baby’s conditions are stable. Preeclampsia generally worsens as pregnancy goes on, so your doctor’s recommendations may change, depending on your health and the health of your baby. Seek care right away To catch the signs of preeclampsia, you should see your doctor for regular prenatal visits. Call your doctor and go straight to the emergency room if you experience severe pain in your abdomen, shortness of breath, severe headaches, or changes in your vision. If you’re concerned about your symptoms, be sure to ask your doctor if what you’re experiencing is normal. Preeclampsia is a pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to another organ system, most often the liver and kidneys. Preeclampsia usually begins after 20 weeks of pregnancy in women whose blood pressure had been normal. Left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious — even fatal — complications for both you and your baby. If you have preeclampsia, the most effective treatment is delivery of your baby. Even after delivering the baby, it can still take a while for you to get better. If you're diagnosed with preeclampsia too early in your pregnancy to deliver your baby, you and your doctor face a challenging task. Your baby needs more time to mature, but you need to avoid putting yourself or your baby at risk of serious complications. Rarely, preeclampsia develops after delivery of a baby, a condition known as postpartum preeclampsia. Symptoms Preeclampsia sometimes develops without any symptoms. High blood pressure may develop slowly, or it may have a sudden onset. Monitoring your blood pressure is an important part of prenatal care because the first sign of preeclampsia is commonly a rise in blood pressure. Blood pressure that exceeds 140/90 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) or greater — documented on two occasions, at least four hours apart — is abnormal. Other signs and symptoms of preeclampsia may include: Excess protein in your urine (proteinuria) or additional signs of kidney problems Severe headaches Changes in vision, including temporary loss of vision, blurred vision or light sensitivity Upper abdominal pain, usually under your ribs on the right side Nausea or vomiting Decreased urine output Decreased levels of platelets in your blood (thrombocytopenia) Impaired liver function Shortness of breath, caused by fluid in your lungs Sudden weight gain and swelling (edema) — particularly in your face and hands — may occur with preeclampsia. But these also occur in many normal pregnancies, so they're not considered reliable signs of preeclampsia. When to see a doctor Make sure you attend your prenatal visits so that your care provider can monitor your blood pressure. Contact your doctor immediately or go to an emergency room if you have severe headaches, blurred vision or other visual disturbance, severe pain in your abdomen, or severe shortness of breath. Because headaches, nausea, and aches and pains are common pregnancy complaints, it's difficult to know when new symptoms are simply part of being pregnant and when they may indicate a serious problem — especially if it's your first pregnancy. If you're concerned about your symptoms, contact your doctor. Causes The exact cause of preeclampsia involves several factors. Experts believe it begins in the placenta — the organ that nourishes the fetus throughout pregnancy. Early in pregnancy, new blood vessels develop and evolve to efficiently send blood to the placenta. In women with preeclampsia, these blood vessels don't seem to develop or function properly. They're narrower than normal blood vessels and react differently to hormonal signaling, which limits the amount of blood that can flow through them. Causes of this abnormal development may include: Insufficient blood flow to the uterus Damage to the blood vessels A problem with the immune system Certain genes Other high blood pressure disorders during pregnancy Preeclampsia is classified as one of four high blood pressure disorders that can occur during pregnancy. The other three are: Gestational hypertension. Women with gestational hypertension have high blood pressure but no excess protein in their urine or other signs of organ damage. Some women with gestational hypertension eventually develop preeclampsia. Chronic hypertension. Chronic hypertension is high blood pressure that was present before pregnancy or that occurs before 20 weeks of pregnancy. But because high blood pressure usually doesn't have symptoms, it may be hard to determine when it began. Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia. This condition occurs in women who have been diagnosed with chronic high blood pressure before pregnancy, but then develop worsening high blood pressure and protein in the urine or other health complications during pregnancy. Risk factors Preeclampsia develops only as a complication of pregnancy. Risk factors include: History of preeclampsia. A personal or family history of preeclampsia significantly raises your risk of preeclampsia. Chronic hypertension. If you already have chronic hypertension, you have a higher risk of developing preeclampsia. First pregnancy. The risk of developing preeclampsia is highest during your first pregnancy. New paternity. Each pregnancy with a new partner increases the risk of preeclampsia more than does a second or third pregnancy with the same partner. Age. The risk of preeclampsia is higher for very young pregnant women as well as pregnant women older than 35. Race. Black women have a higher risk of developing preeclampsia than women of other races. Obesity. The risk of preeclampsia is higher if you're obese. Multiple pregnancy. Preeclampsia is more common in women who are carrying twins, triplets or other multiples. Interval between pregnancies. Having babies less than two years or more than 10 years apart leads to a higher risk of preeclampsia. History of certain conditions. Having certain conditions before you become pregnant — such as chronic high blood pressure, migraines, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, a tendency to develop blood clots, or lupus — increases your risk of preeclampsia. In vitro fertilization. Your risk of preeclampsia is increased if your baby was conceived with in vitro fertilization. Complications The more severe your preeclampsia and the earlier it occurs in your pregnancy, the greater the risks for you and your baby. Preeclampsia may require induced labor and delivery. Delivery by cesarean delivery (C-section) may be necessary if there are clinical or obstetric conditions that require a speedy delivery. Otherwise, your doctor may recommend a scheduled vaginal delivery. Your obstetric provider will talk with you about what type of delivery is right for your condition. Complications of preeclampsia may include: Fetal growth restriction. Preeclampsia affects the arteries carrying blood to the placenta. If the placenta doesn't get enough blood, your baby may receive inadequate blood and oxygen and fewer nutrients. This can lead to slow growth known as fetal growth restriction, low birth weight or preterm birth. Preterm birth. If you have preeclampsia with severe features, you may need to be delivered early, to save the life of you and your baby. Prematurity can lead to breathing and other problems for your baby. Your health care provider will help you understand when is the ideal time for your delivery. Placental abruption. Preeclampsia increases your risk of placental abruption, a condition in which the placenta separates from the inner wall of your uterus before delivery. Severe abruption can cause heavy bleeding, which can be life-threatening for both you and your baby. HELLP syndrome. HELLP — which stands for hemolysis (the destruction of red blood cells), elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count — syndrome is a more severe form of preeclampsia, and can rapidly become life-threatening for both you and your baby. Symptoms of HELLP syndrome include nausea and vomiting, headache, and upper right abdominal pain. HELLP syndrome is particularly dangerous because it represents damage to several organ systems. On occasion, it may develop suddenly, even before high blood pressure is detected or it may develop without any symptoms at all. Eclampsia. When preeclampsia isn't controlled, eclampsia — which is essentially preeclampsia plus seizures — can develop. It is very difficult to predict which patients will have preeclampsia that is severe enough to result in eclampsia. Often, there are no symptoms or warning signs to predict eclampsia. Because eclampsia can have serious consequences for both mom and baby, delivery becomes necessary, regardless of how far along the pregnancy is. Other organ damage. Preeclampsia may result in damage to the kidneys, liver, lung, heart, or eyes, and may cause a stroke or other brain injury. The amount of injury to other organs depends on the severity of preeclampsia. Cardiovascular disease. Having preeclampsia may increase your risk of future heart and blood vessel (cardiovascular) disease. The risk is even greater if you've had preeclampsia more than once or you've had a preterm delivery. To minimize this risk, after delivery try to maintain your ideal weight, eat a variety of fruits and vegetables, exercise regularly, and don't smoke. Prevention Researchers continue to study ways to prevent preeclampsia, but so far, no clear strategies have emerged. Eating less salt, changing your activities, restricting calories, or consuming garlic or fish oil doesn't reduce your risk. Increasing your intake of vitamins C and E hasn't been shown to have a benefit. Some studies have reported an association between vitamin D deficiency and an increased risk of preeclampsia. But while some studies have shown an association between taking vitamin D supplements and a lower risk of preeclampsia, others have failed to make the connection. In certain cases, however, you may be able to reduce your risk of preeclampsia with: Low-dose aspirin. If you meet certain risk factors — including a history of preeclampsia, a multiple pregnancy, chronic high blood pressure, kidney disease, diabetes or autoimmune disease — your doctor may recommend a daily low-dose aspirin (81 milligrams) beginning after 12 weeks of pregnancy. Calcium supplements. In some populations, women who have calcium deficiency before pregnancy — and who don't get enough calcium during pregnancy through their diets — might benefit from calcium supplements to prevent preeclampsia. However, it's unlikely that women from the United States or other developed countries would have calcium deficiency to the degree that calcium supplements would benefit them. It's important that you don't take any medications, vitamins or supplements without first talking to your doctor. Before you become pregnant, especially if you've had preeclampsia before, it's a good idea to be as healthy as you can be. Lose weight if you need to, and make sure other conditions, such as diabetes, are well-managed. Once you're pregnant, take care of yourself — and your baby — through early and regular prenatal care. If preeclampsia is detected early, you and your doctor can work together to prevent complications and make the best choices for you and your baby. Diagnosis To diagnose preeclampsia, you have to have high blood pressure and one or more of the following complications after the 20th week of pregnancy: Protein in your urine (proteinuria) A low platelet count Impaired liver function Signs of kidney problems other than protein in the urine Fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) New-onset headaches or visual disturbances Previously, preeclampsia was only diagnosed if high blood pressure and protein in the urine were present. However, experts now know that it's possible to have preeclampsia, yet never have protein in the urine. A blood pressure reading in excess of 140/90 mm Hg is abnormal in pregnancy. However, a single high blood pressure reading doesn't mean you have preeclampsia. If you have one reading in the abnormal range — or a reading that's substantially higher than your usual blood pressure — your doctor will closely observe your numbers. Having a second abnormal blood pressure reading four hours after the first may confirm your doctor's suspicion of preeclampsia. Your doctor may have you come in for additional blood pressure readings and blood and urine tests. Tests that may be needed If your doctor suspects preeclampsia, you may need certain tests, including: Blood tests. Your doctor will order liver function tests, kidney function tests and also measure your platelets — the cells that help blood clot. Urine analysis. Your doctor will ask you to collect your urine for 24 hours, for measurement of the amount of protein in your urine. A single urine sample that measures the ratio of protein to creatinine — a chemical that's always present in the urine — also may be used to make the diagnosis. Fetal ultrasound. Your doctor may also recommend close monitoring of your baby's growth, typically through ultrasound. The images of your baby created during the ultrasound exam allow your doctor to estimate fetal weight and the amount of fluid in the uterus (amniotic fluid). Nonstress test or biophysical profile. A nonstress test is a simple procedure that checks how your baby's heart rate reacts when your baby moves. A biophysical profile uses an ultrasound to measure your baby's breathing, muscle tone, movement and the volume of amniotic fluid in your uterus. Treatment The most effective treatment for preeclampsia is delivery. You're at increased risk of seizures, placental abruption, stroke and possibly severe bleeding until your blood pressure decreases. Of course, if it's too early in your pregnancy, delivery may not be the best thing for your baby. If you're diagnosed with preeclampsia, your doctor will let you know how often you'll need to come in for prenatal visits — likely more frequently than what's typically recommended for pregnancy. You'll also need more frequent blood tests, ultrasounds and nonstress tests than would be expected in an uncomplicated pregnancy. Medications Possible treatment for preeclampsia may include: Medications to lower blood pressure. These medications, called antihypertensives, are used to lower your blood pressure if it's dangerously high. Blood pressure in the 140/90 millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) range generally isn't treated. Although there are many different types of antihypertensive medications, a number of them aren't safe to use during pregnancy. Discuss with your doctor whether you need to use an antihypertensive medicine in your situation to control your blood pressure. Corticosteroids. If you have severe preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome, corticosteroid medications can temporarily improve liver and platelet function to help prolong your pregnancy. Corticosteroids can also help your baby's lungs become more mature in as little as 48 hours — an important step in preparing a premature baby for life outside the womb. Anticonvulsant medications. If your preeclampsia is severe, your doctor may prescribe an anticonvulsant medication, such as magnesium sulfate, to prevent a first seizure. Bed rest Bed rest used to be routinely recommended for women with preeclampsia. But research hasn't shown a benefit from this practice, and it can increase your risk of blood clots, as well as impact your economic and social lives. For most women, bed rest is no longer recommended. Hospitalization Severe preeclampsia may require that you be hospitalized. In the hospital, your doctor may perform regular nonstress tests or biophysical profiles to monitor your baby's well-being and measure the volume of amniotic fluid. A lack of amniotic fluid is a sign of poor blood supply to the baby. Delivery If you're diagnosed with preeclampsia near the end of your pregnancy, your doctor may recommend inducing labor right away. The readiness of your cervix — whether it's beginning to open (dilate), thin (efface) and soften (ripen) — also may be a factor in determining whether or when labor will be induced. In severe cases, it may not be possible to consider your baby's gestational age or the readiness of your cervix. If it's not possible to wait, your doctor may induce labor or schedule a C-section right away. During delivery, you may be given magnesium sulfate intravenously to prevent seizures. If you need pain-relieving medication after your delivery, ask your doctor what you should take. NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), can increase your blood pressure. After delivery, it can take some time before high blood pressure and other preeclampsia symptoms resolve. What is preeclampsia? Preeclampsia is a serious blood pressure condition that develops during pregnancy. People with preeclampsia often have high blood pressure (hypertension) and high levels of protein in their urine (proteinuria). Preeclampsia typically develops after the 20th week of pregnancy. It can also affect other organs in the body and be dangerous for both the mom and her developing fetus (unborn baby). Because of these risks, preeclampsia needs to be treated by a healthcare provider. What happens when you have preeclampsia? When you have preeclampsia, your blood pressure is elevated (higher than 140/90 mmHg), and you may have high levels of protein in your urine. Preeclampsia puts stress on your heart and other organs and can cause serious complications. It can also affect the blood supply to your placenta, impair liver and kidney function or cause fluid to build up in your lungs. The protein in your urine is a sign of kidney dysfunction. How common is preeclampsia? Preeclampsia is a condition unique to pregnancy that complicates up to 8% of all deliveries worldwide. In the United States, it's the cause of about 15% of premature deliveries (delivery before 37 weeks of pregnancy). Who gets preeclampsia? Preeclampsia may be more common in first-time mothers. Healthcare providers are not entirely sure why some people develop preeclampsia. Some factors that may put you at a higher risk are: History of high blood pressure, kidney disease or diabetes. Expecting multiples. Family history of preeclampsia. Autoimmune conditions like lupus. Obesity. SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES What are the symptoms? Many people with preeclampsia do not have any symptoms. For those that do, some of the first signs of preeclampsia are high blood pressure, protein in the urine and retaining water (this can cause weight gain and swelling). Other signs of preeclampsia include: Headaches. Blurry vision or light sensitivity. Dark spots appearing in your vision. Right side abdominal pain. Swelling in your hands and face (edema). Shortness of breath. It's essential to share all of your pregnancy symptoms with your healthcare provider. Many people are unaware they have preeclampsia until their blood pressure and urine are checked at a prenatal appointment. Severe preeclampsia may include symptoms like: Hypertensive emergency (blood pressure is 160/110 mmHg or higher). Decreased kidney or liver function. Fluid in the lungs. Low blood platelet levels (thrombocytopenia). Decreased urine production If your preeclampsia is severe, you may be admitted to the hospital for closer observation or need to deliver your baby as soon as possible. Your healthcare provider may give you medications for high blood pressure or to help your baby's lungs develop before delivery. What causes preeclampsia? No one is entirely sure. Preeclampsia is believed to come from a problem with the health of the placenta (the organ that develops in the uterus during pregnancy and is responsible for providing oxygen and nutrients to the fetus). The blood supply to the placenta might be decreased in preeclampsia, and this can lead to problems with both you and the fetus. Does stress cause preeclampsia? While stress may impact blood pressure, stress is not one of the direct causes of preeclampsia. While some stress is unavoidable during pregnancy, avoiding high-stress situations or learning to manage your stress is a good idea. What week of pregnancy does preeclampsia start? Preeclampsia typically occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy, but it can come earlier. Most preeclampsia occurs at or near term (37 weeks gestation). Preeclampsia can also come after delivery (postpartum preeclampsia), which usually occurs between the first few days to one week after delivery. In rare cases, it begins weeks after delivery. Will preeclampsia affect my baby? Preeclampsia can cause preterm delivery (your baby needing delivered early). Premature babies are at increased risk for health complications like low birth weight and respiratory issues. DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS How is it diagnosed? Preeclampsia is often diagnosed during routine prenatal appointments when your healthcare provider checks your weight gain, blood pressure and urine. If preeclampsia is suspected, your healthcare provider may: Order additional blood tests to check kidney and liver functions. Suggest a 24-hour urine collection to watch for proteinuria. Perform an ultrasound and other fetal monitoring to look at the size of your baby and assess the amniotic fluid volume. Preeclampsia can be categorized as mild or severe. You may be diagnosed with mild preeclampsia if you have high blood pressure plus high levels of protein in your urine. You are diagnosed with severe preeclampsia if you have symptoms of mild preeclampsia plus: Signs of kidney or liver damage (seen in blood work). Low platelet count Fluid in your lungs. Headaches and dizziness. Visual impairment or seeing spots. MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT How is preeclampsia treated? Your healthcare provider will advise you on the best way to treat preeclampsia. Treatment generally depends on how severe your preeclampsia is and how far along you are in pregnancy. If you're close to full term (37 weeks pregnant or greater), your baby will probably be delivered early. You can still have a vaginal delivery, but sometimes a Cesarean delivery (C-section) is recommended. Your healthcare provider may give you medication to help your baby's lungs develop and manage your blood pressure until the baby can be delivered. Sometimes it is safer to deliver the baby early than to risk prolonging the pregnancy. When preeclampsia develops earlier in pregnancy, you'll be monitored closely in an effort to prolong the pregnancy and allow for the fetus to grow and develop. You'll have more prenatal appointments, including ultrasounds, urine tests and blood draws. You may be asked to check your blood pressure at home. If you are diagnosed with severe preeclampsia, you could remain in the hospital until you deliver your baby. If the preeclampsia worsens or becomes more severe, your baby will need to be delivered. During labor and following delivery, people with preeclampsia are often given magnesium intravenously (directly into the vein) to prevent the development of eclampsia (seizures from preeclampsia). Is there a cure for preeclampsia? No, there isn't a cure for preeclampsia. Preeclampsia can only be cured with delivery. Your healthcare provider will still want to monitor you for several weeks after delivery to make sure your symptoms go away. PREVENTION How can I reduce my risk of getting preeclampsia? For people with risk factors, there are some steps that can be taken prior to and during pregnancy to lower the chance of developing preeclampsia. These steps can include: Losing weight if you have overweight/obesity (prior to pregnancy-related weight gain). Controlling your blood pressure and blood sugar (if you had high blood pressure or diabetes prior to pregnancy). Maintaining a regular exercise routine. Getting enough sleep. Eating healthy foods that are low in salt and avoiding caffeine. Can you prevent preeclampsia? Taking a baby aspirin daily has been demonstrated to decrease your risk of developing preeclampsia by approximately 15%. If you have risk factors for preeclampsia, your healthcare provider may recommend starting aspirin in early pregnancy (by 12 weeks gestation). OUTLOOK / PROGNOSIS What are the most common complications of preeclampsia? If left untreated, preeclampsia can be potentially fatal to both you and your baby. Before delivery, the most common complications are preterm birth, low birth weight or placental abruption. Preeclampsia can cause HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count). This happens when preeclampsia damages your liver and red blood cells and interferes with blood clotting. Other signs of HELLP syndrome are blurry vision, chest pain, headaches and nosebleeds. After you've delivered your baby, you may be at an increased risk for: Kidney disease. Heart attack. Stroke. Developing preeclampsia in future pregnancies. Does preeclampsia go away after delivery? Preeclampsia typically goes away within days to weeks following delivery. Sometimes, your blood pressure can remain high for a few weeks after delivery, requiring treatment with medication. Your healthcare provider will work with you after your pregnancy to manage your blood pressure. People with preeclampsia — particularly those who develop the condition early in pregnancy — are at greater risk for high blood pressure (hypertension) and heart disease later in life. Knowing this information, those women can work with their primary care provider to take steps to reduce these risks. LIVING WITH When should I see my healthcare provider? Preeclampsia can be a fatal condition during pregnancy. If you're being treated for this condition, make sure to see your healthcare provider for all of your appointments and blood or urine tests. Contact your obstetrician if you have any concerns or questions about your symptoms. Go to the nearest hospital if you're pregnant and experience the following: Symptoms of a seizure-like twitching or convulsing. Shortness of breath. Sharp pain in your abdomen (specifically the right side). Blurry vision. Severe headache that won't go away. Dark spots in your vision that don't go away. What questions should I ask my doctor? If your healthcare provider has diagnosed you with preeclampsia, it's normal to have concerns. Some common questions to ask your healthcare provider are: Do I need to take medication? Do I need to restrict my activities? What changes should I make to my diet? How are you planning to monitor me and my baby now that I have preeclampsia? Will I need to deliver my baby early? How can I best manage preeclampsia? FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS What's the difference between preeclampsia and eclampsia? Eclampsia is severe preeclampsia that causes seizures. It's considered a complication of preeclampsia, but it can happen without signs of preeclampsia. In rare cases, it can lead to coma, stroke or death. What is postpartum preeclampsia? Postpartum preeclampsia is when you develop preeclampsia after your baby is born. It typically happens within two days of giving birth but can also develop several weeks later. The signs of postpartum preeclampsia are similar to preeclampsia and include swelling in your limbs and extremities, headaches, seeing spots, stomach pains and nausea. It's a serious condition that can cause seizures, stroke and organ damage.